Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

15 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

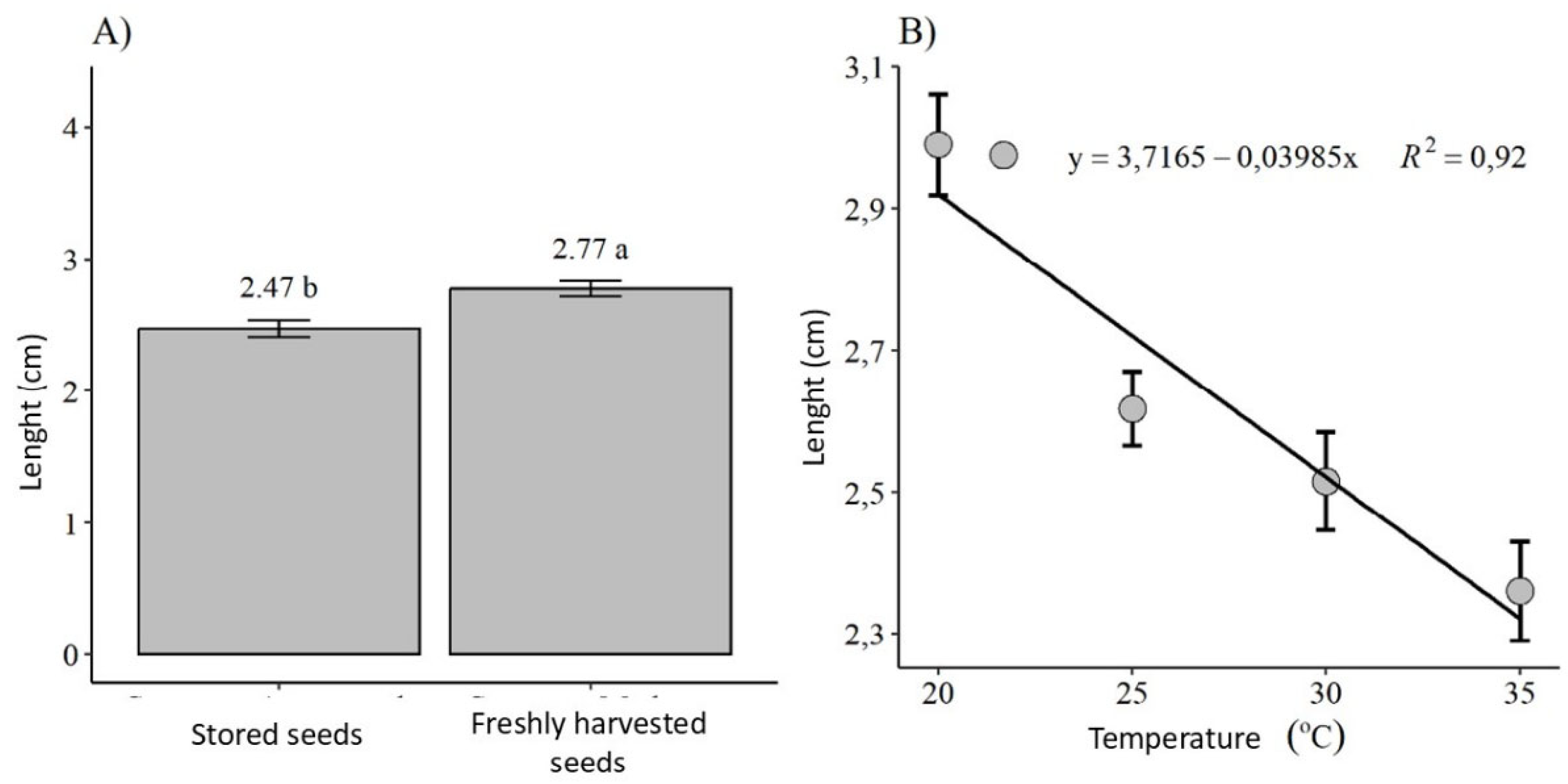

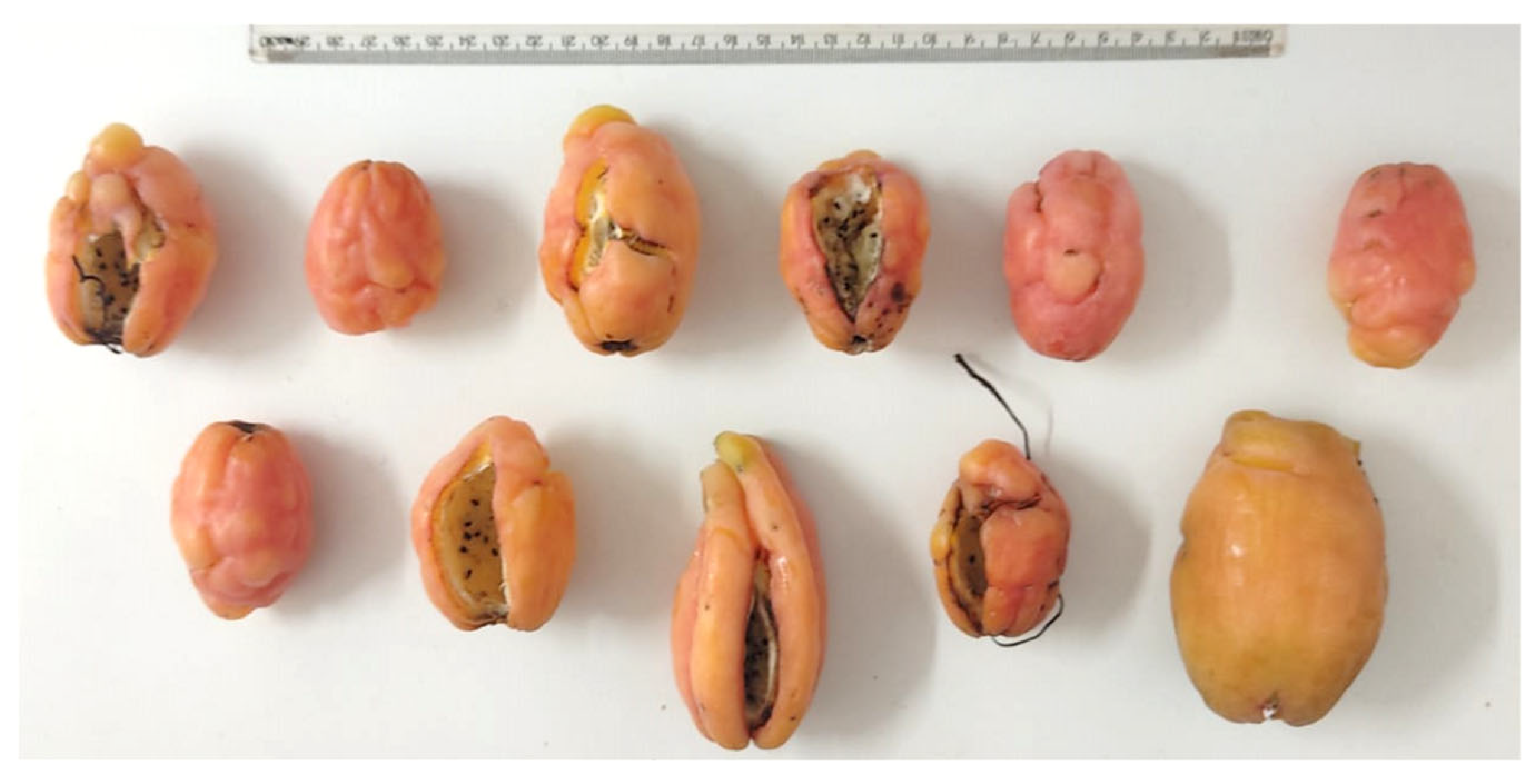

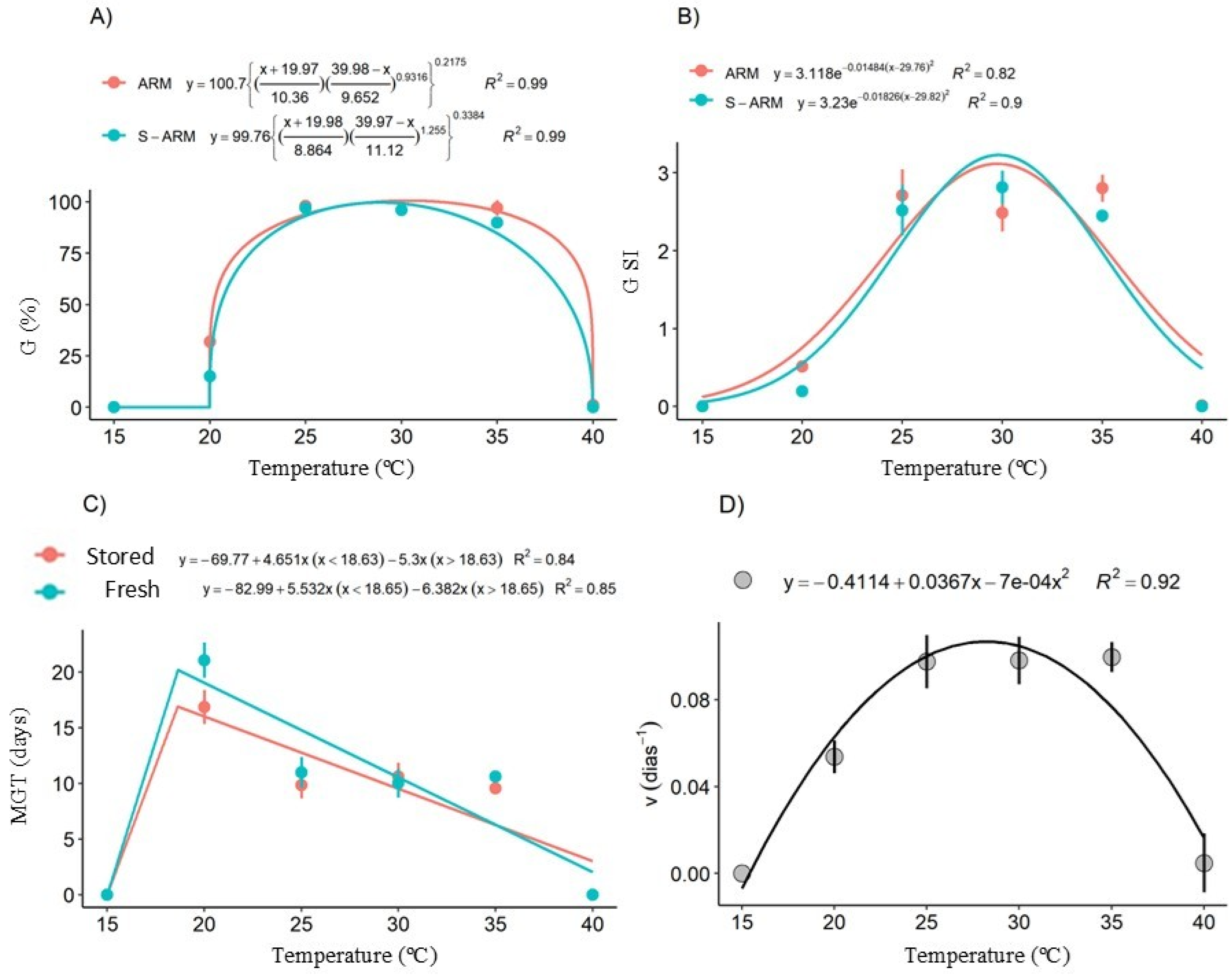

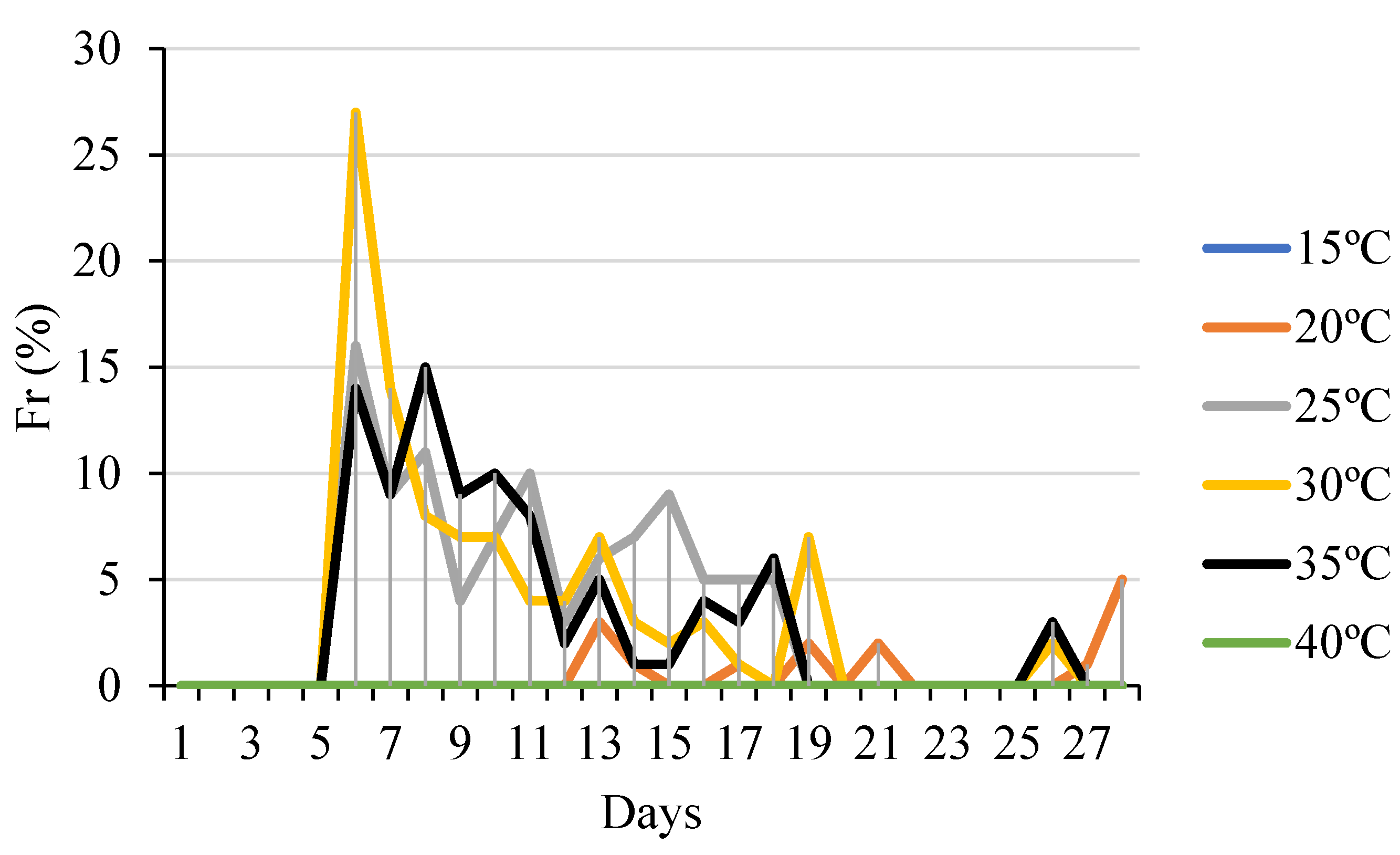

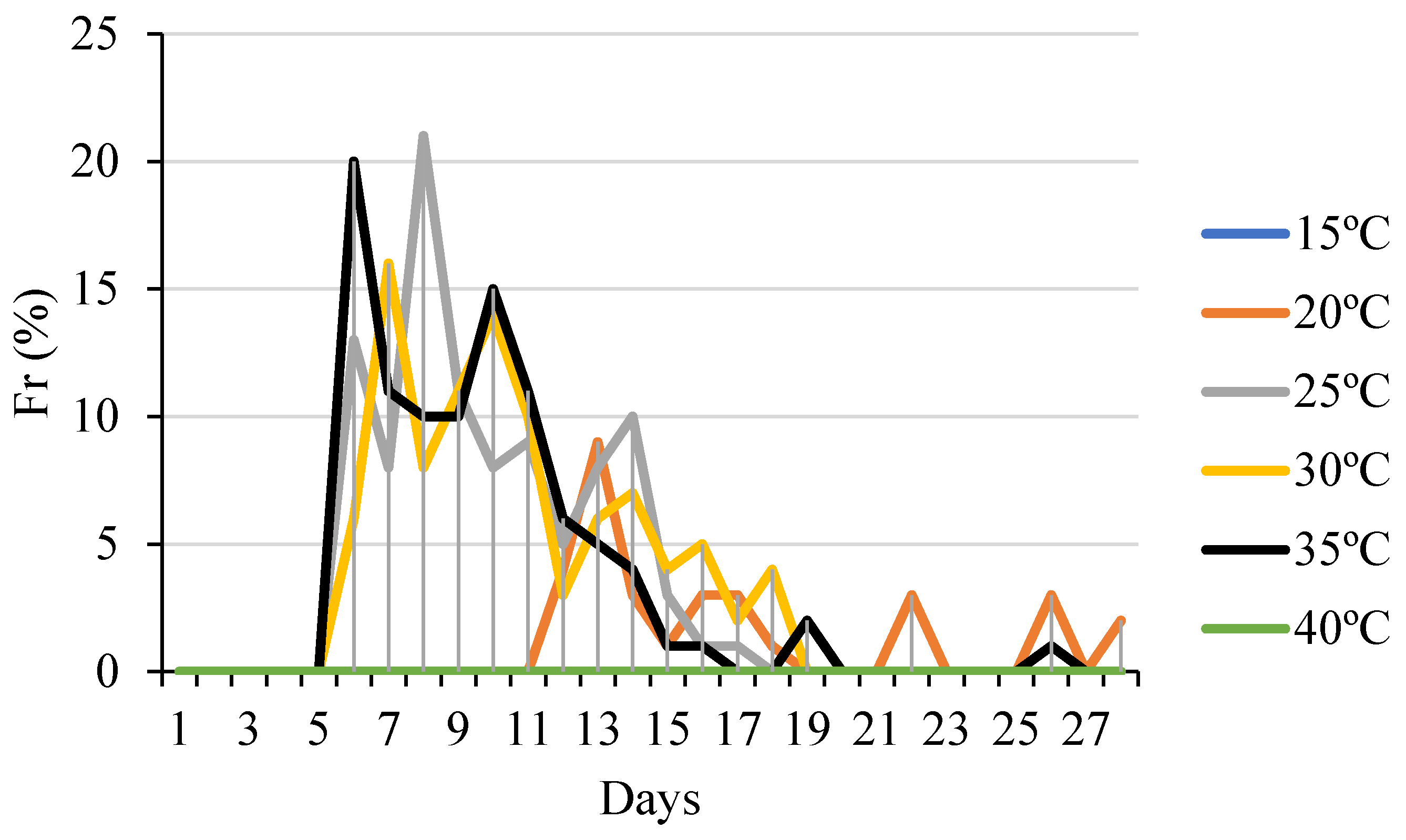

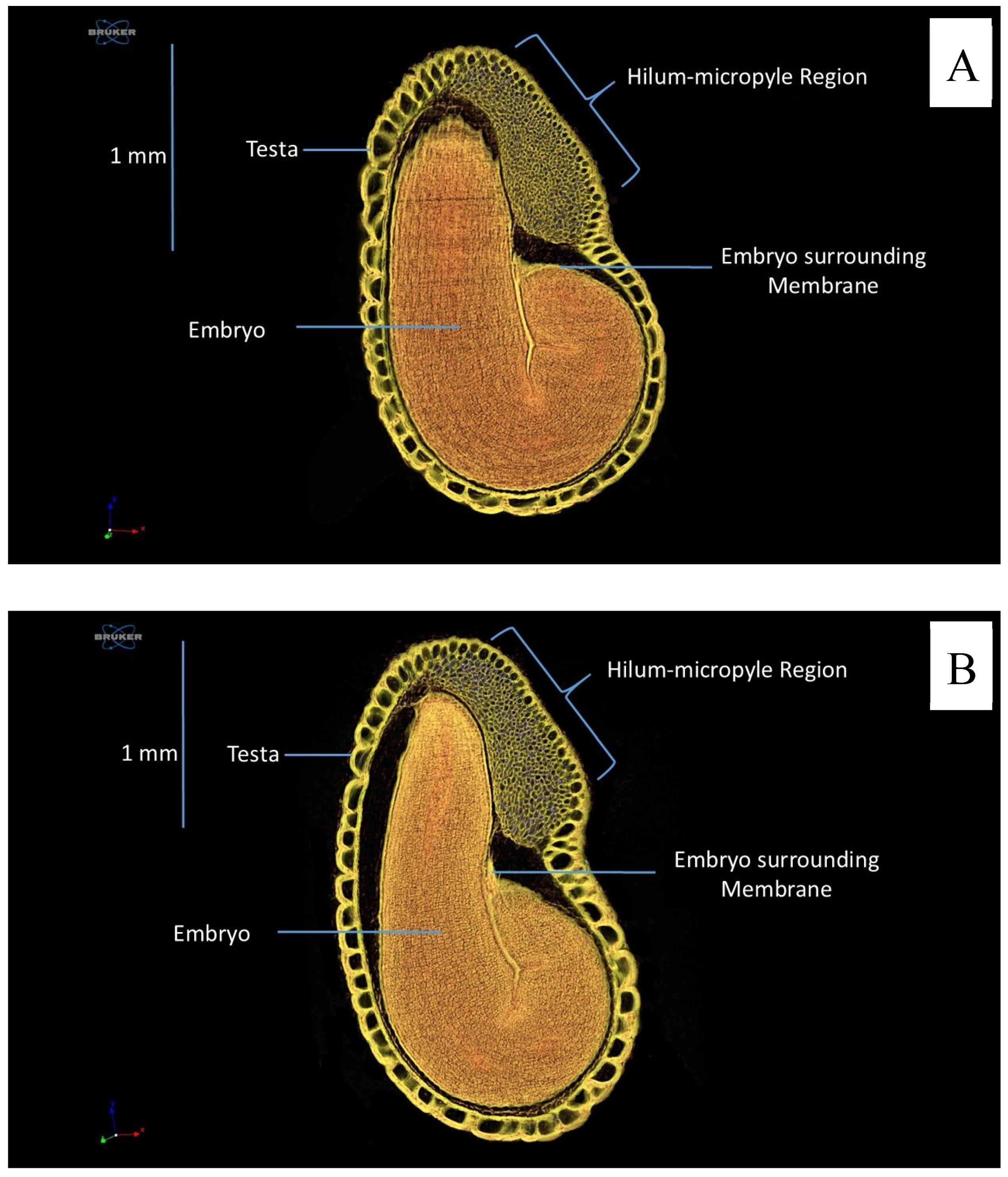

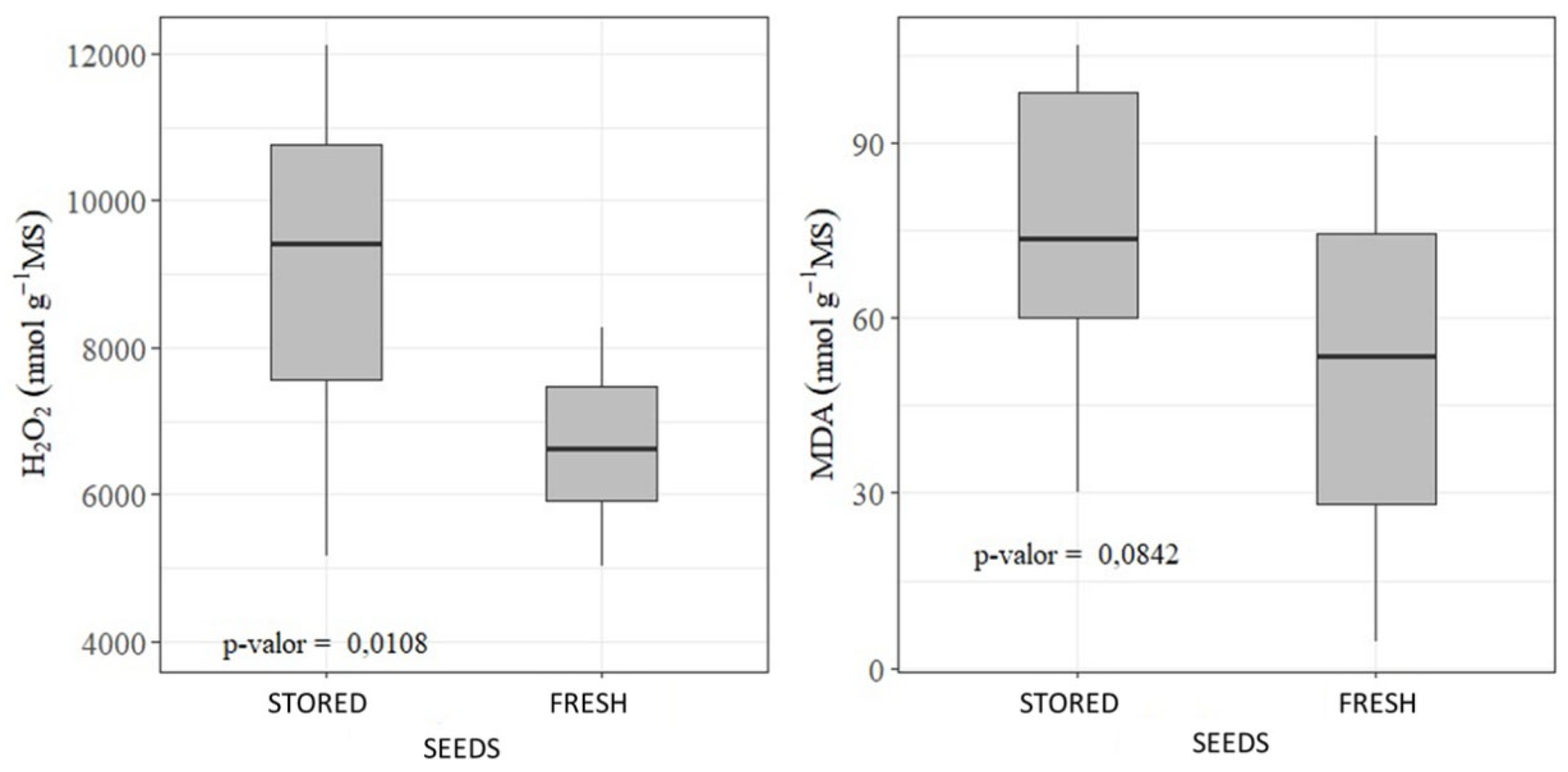

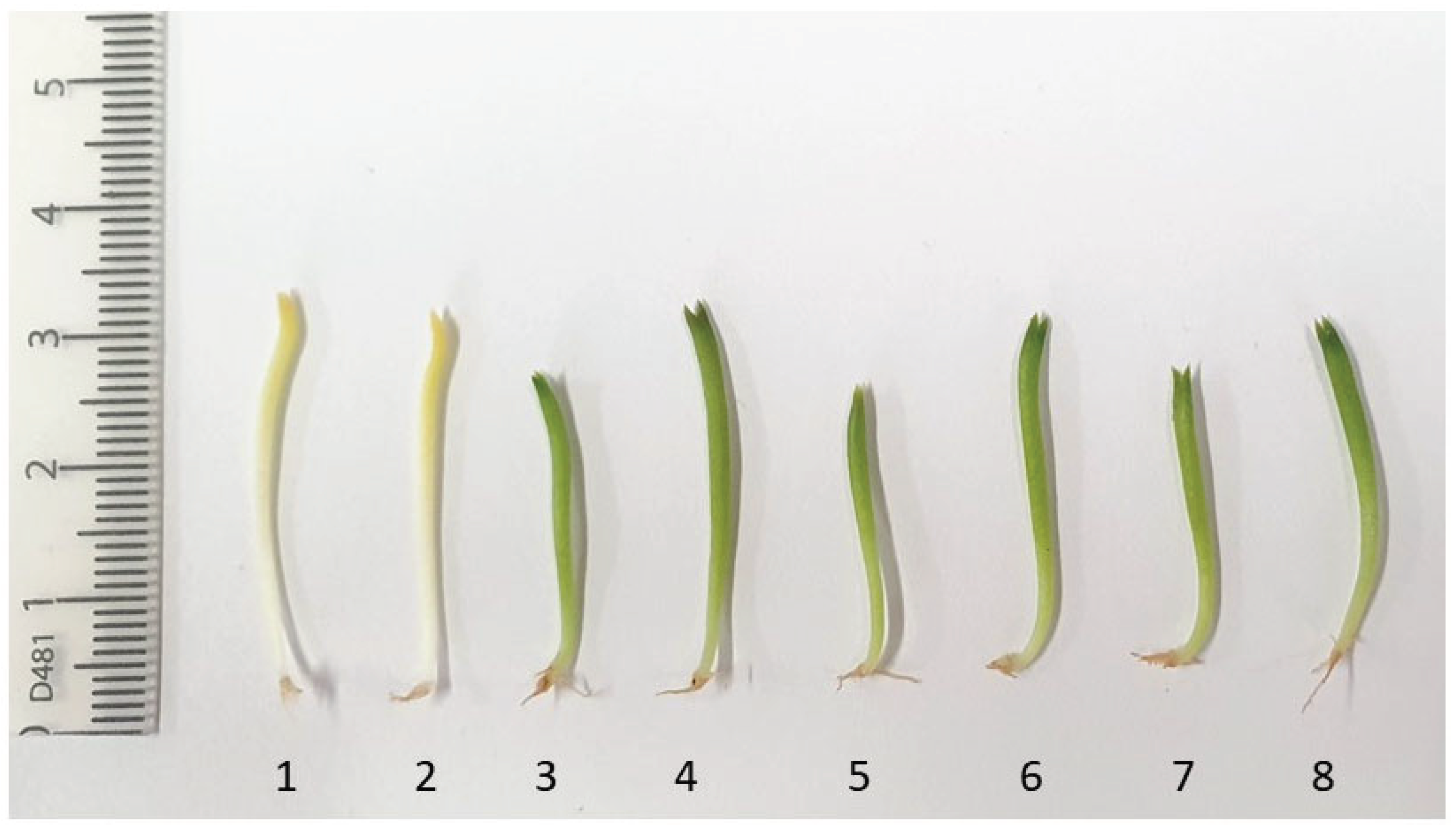

Knowledge about the germination potential of Mandacaru seeds is fundamental for maintaining breeding programs and germplasm banks. Thus, we aimed to study the germination of stored and freshly harvested mandacaru seeds in order to investigate seed viability as a function of storage imposition, in addition to characterizing seed anatomy and conducting biochemical evaluation. Germination tests were conducted in a completely randomized design in a 2×6 factorial scheme, with two storage conditions and six temperatures (15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40°C), with 4 replications of 25 seeds each. Anatomical evaluation tests and biochemical tests had 5 and 10 replications for each storage condition, respectively. It is concluded that the range of 25-35°C is ideal for germination of C. jamacaru seeds, and temperatures below 20°C and above 35°C are detrimental to germination. X-ray computed microtomography was efficient for characterizing seed anatomy and differentiating their tissues, allowing accurate and clear evaluation of their internal structures, and proper storage was efficient in minimizing the deleterious effects of H₂O₂ and MDA accumulation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Seed Collection

2.2. Germination Tests and Experimental Design

2.3. Germination Variables

2.4. Anatomical Analysis

2.5. Seedling Length Measurement

2.6. Biochemical Analysis (Oxidative Stress)

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The range of 25-35°C is ideal for the germination of C. jamacaru seeds. Temperatures below 20°C and above 35°C are detrimental to germination;

- Seed lots of C. jamacaru stored for six years maintain viability and germinability at high percentages;

- X-ray computed microtomography is efficient for characterizing seed anatomy, allowing accurate and clear evaluation of their internal structures;

- Proper storage was efficient in minimizing the deleterious effects of H₂O₂ and MDA accumulation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goettsch, B; Taylor, CH; Piñón, GC; Duffy, JP; Frances, A; Hernández, HM; Inger, R; Pollock, C; Schipper, J; Superina, M; Taylor, NP; Tognelli, M; Abba, AM; Arias, S; Nava, HJA; Baker, MA; Bárcenas, RT; Barrios, D; Braun, P; Butterworth, CA; Búrquez, A; Caceres, F; Basañez, MC; Díaz, RC; Perea, MV; Demaio, PH; Barros, WAD; Durán, R; Yancas, LF; Felger, RS; Maurice, BF; Maurice, WAF; Gann, G; Hinostrosa, CG; Torres, LRG; Griffith, MP; Guerrero, PC; Hammel, B; Heil, KD; Oria, JGH; Hoffmann, M; Ishihara, MI; Kiesling, R; Larocca, J; Luz, JLL; Loaiza, CR; Lowry, M; Machado, MC; Majure, LC; Ávalos, JGM; Martorell, C; Maschinski, J; Méndez, E; Mittermeier, RA; Nassar, JM; Ortiz, VN; Oakley, LJ; Baes, P; O Ferreira, ABP; Pinkava, DJ; Porter, JM; Martinez, RP; Gamarra, JR; Pérez, PS; Martínez, ES; Smith, M; J Manuel Sotomayor M del, C; Stuart, SM; Muñoz, JLT; Terrazas, T; Terry, M; Trevisson, M; Valverde, T; Devender, TRV; Pérez, MEV; Walter, HE; Wyatt, SE; Zappi, DC; Hurtado, JAZ; Gaston, KJ. High proportion of cactus species threatened with extinction. Nature plants 2015, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, SRS; Zappi, D; Taylor, N; Machado, M. Plano de ação nacional para a conservação das Cactáceas – Série espécies ameaçadas. In Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade, 1st ed.; ICMBIO: Brasília, Brasil, 2011; pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cactaceae in Flora e Funga do Brasil 2020. Available online: https://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/FB70 (accessed on 04 april 2025).

- Simões, SS; Zappi, DC; Aona, LYS. A família Cactaceae no Parque Nacional de Boa Nova, Estado da Bahia, Brasil. Hoehnea 2020, 47, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, UP; Araújo, EL; El-Deir, ACA; Lima, ALA; Souto, A; Bezerra, BM; Ferraz, EMN; Freire, EMX; Sampaio, EVDSB; Las-Casas, FMG; Moura, GJB; Pereira, GA; Melo, JG; Ramos, MA; Rodal, MJN; Schiel, N; Neves, RML; Alves, RRN; Azevedo Junior, SM; Telino Junior, WR; Severi, W. Caatinga Revisited: Ecology and Conservation of an Important Seasonal Dry Forest. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, WJSF; Vasconcelos, RN; Costa, DP; Duverger, SG; Lobão, JSB; Souza, DTM; Herrmann, SM; Santos, NA; Rocha, ROF; Ferreira, JF; Oliveira, M; Barbosa, LS; Cordeiro, CL; Aguiar, WM. Towards Uncovering Three Decades of LULC in the Brazilian Drylands: Caatinga Biome Dynamics (1985–2019). Land 2024, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, A; Teles, M; Machado, M. Cactos do semiárido do Brasil: guia ilustrado; INSA: Campina Grande, Brasil, 2013; pp. 7–103. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, FA; Castro, NHA; Souza, VC; Barbosa, AS; Fonseca, WB; Silva, JHCS. Análise da estrutura e distribuição espacial de Pilosocereus pachycladus subsp. pernambucoensis em vegetação da Caatinga e de brejo de altitude. Ciência Florestal 2023, 33, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegloch, A; Carvalho, LR; Prado, SO; Lima, RA. Potencial de espécies da família Cactaceae no brasil: uma revisão sistemática. Biodiversidade 2020, 19, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, CE; Menezes, MOT; Araújo, FS; Sfair, JC. High endemism of cacti remains unprotected in the Caatinga. Biodiversity and Conservation 2022, 31, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, IAP; Lopes, AS; Abreu, KG; Sousa, RR; Lacerda, AV; Roque, IA; Paiva, IAM. Enrichment strategy with Cereus jamacaru DC. in a clearing area introduced by vegetative propagation. Research, Society and Development 2021, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, JHCS; Azeredo, GA; Targino, VA. Resposta germinativa de sementes de cactáceas colunares sob diferentes regimes de temperatura e de potencial hídrico. Scientia Plena 2021, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Neto, JP; Silva, VDN; Silva, PA; Santos, YMP; Monteiro, PHS; Silva, LASG. Características físico-químicas do fruto do mandacaru (Cereus jamacaru P. DC.) cultivado no sertão alagoano. Revista Craibeiras de Agroecologia 2019, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Camara, NM; Oliveira, TLS. Uso medicinal do Cereus jamacaru DC. (mandacaru): uma revisão. RECIMA21-Revista Científica Multidisciplinar 2021, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante, MZB; Dultra, DFS; Silva, HLC; Cotting, JC; Silva, SDP; Siqueira Filho, JA. Potencial ornamental de espécies do Bioma Caatinga. Comunicata Scientiae 2017, 8, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cereus jamacaru, The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017. Available online. (accessed on 04 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Resende, AS; Chaer, GM. Recuperação ambiental em áreas de produção de petróleo e gás em terra na Caatinga, 1st ed.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brasil, 2021; pp. pp 1–149. [Google Scholar]

- Embrapa; Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária. Regras para análise de sementes; Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento: Brasília, Brasil, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, TC; Oliveira, MRG; Perez-Marin, AM. Aportes metodológicos para a implantação e avaliação de experimentos com sementes em relação a germinação e ao vigor. BIOFIX Scientific Journal 2022, 7, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guariz, HR; Shimizu, GD; Paula, JCB; Sperandio, HV; Ribeiro Junior, WA; Oliveira, HC; Jussiani, EI; Andrello, AC; Marubayashi, RYP; Picoli, MHS; Ruediger, J; Couto, APS; Moraes, KAM. Anatomy and Germination of Erythrina velutina Seeds under a Different Imbibition Period in Gibberellin. Seeds 2022, 1, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexieva, V; Sergiev, I; Mapelli, S; Karanov, E. The effect of drought and ultraviolet radiation on growth and stress markers in pea and wheat. Plant Cell Environ. 2001, 24, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camejo, G; Wallin, B; Enojärvi, M. Analyses of oxidation and antioxidants using microtiter plates. In Free Radical and Antioxidants Protocols; Amstrong, D., Ed.; Humana Press: Mölndal, Sweden, 1998; Volume 108, pp. 377–387. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, GD; Marubayashi, RYP; Gonçalves, LSA. AgroR: An R package and a Shiny interface for agricultural experiment analysis. Acta Scientiarum. Agronomy 2025, 47, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, GD; Gonçalves, LSA. AgroReg: Main regression models in agricultural sciences implemented as an R Package. Scientia Agricola 2023, 80, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rito, KF; Rocha, EA; Leal, IR; Meiado, MV. As sementes de mandacaru têm memória hídrica. Boletín de la Sociedad Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Cactáceas y otras Suculentas 2009, 6, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Targino, VA; Azerêdo, GA; Silva, JHCS; Souza, VC. Influence of the conservation condition on the germination of mandacaru seeds from the Caatinga and Atlantic Forest areas. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Agrárias 2021, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerônimo, REO; Nero, JDP; Martins, VA; Cabral, EFS; Azêredo, GA; Souza, VC. Germinação de sementes de Cereus jamacaru DC subsp. jamacaru oriundas do curimataú oriental paraíbano submetidas a diferentes temperaturas. Revista JRG de Estudos Acadêmicos 2024, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, JHCS; Azeredo, GAD. Germinação de sementes de cactos sob estresse salino. Revista Caatinga 2022, 35, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y; Hu, J; Wang, X; Shao, C. Seed priming with chitosan improves maize germination and seedling growth in relation to physiological changes under low temperature stress. SeedScience Center 2009, 10, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilgert, MA; Sá, LC; Medeiros Junior, JJ; Lazarotto, M; Souza, PVD. Luminosidade e temperatura na germinação de sementes de nogueira-pecã. Pesquisa Agropecuária Gaúcha 2021, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, RAN; David, AMSS; Figueiredo, JC; Pereira, KKG; Fogaça, CA; Alves, FRP; Soares, LM. Germinação e vigor de sementes de mogno africano sob diferentes temperaturas. Ciência Florestal 2020, 30, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A. Effect of Low-Temperature Stress on Germination, Growth, and Phenology of Plants: A Review. In Physiological Processes in Plants Under Low Temperature Stress, 1st ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 1–106. [Google Scholar]

- Szczerba, A; Plazek, A; Pastuszak, J; Kopeć, P; Hornyák, M; Dubert, F. Effect of Low Temperature on Germination, Growth, and Seed Yield of Four Soybean (Glycine max L.) Cultivars. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbrussi, CAG; Zucareli, C. Germinação sob altas temperaturas para avaliação do potencial fisiológico de sementes de milho. Ciência Rural 2015, 45, 1736–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos Filho, J. Fisiologia de sementes de plantas cultivadas, 2nd ed.; FEALQ: Piracicaba, Brasil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sghaier, AH; Tarnawa, Á; Khaeim, H; Kovács, GP; Gyuricza, C; Kende, Z. The Effects of Temperature and Water on the Seed Germination and Seedling Development of Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Plants 2022, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guariz, HR; Shimizu, GD; Castilho, IM; Paula, JCB; Ribeiro Junior, WA; Sperandio, HV. Germination of Aristolochia elegans Mast. seeds at different temperatures and concentrations of gibberellin. Comunicata Scientiae 2022, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiado, Marcos Vinicius. Germinação de sementes de cactos do Brasil: fotoblastismo e temperaturas cardeais. Informativo Abrates 2012, 22, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra, JWA; Silva, VB; Leandro, CS; Campos, NB; Muniz, JI; Costa, MHN; Ribeiro, TG; Linhares, KV; Tavares, SGS; Lima, EE; Feitosa, TKM; Silva Junior, JP; Pereira, MESS; Tavares, AB; Santos, MAF; Silva, MAP. Evaluation of pre-germinative treatments in seeds of Cereus jamacaru DC ssp. jamacaru (Cactaceae). Research, Society and Development 2020, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, CFG; Daibes, LF; Barbosa, FS; Moura, FBP; Silva, JV. Alterações fisiológicas e bioquímicas impulsionadas pela qualidade da luz durante a germinação e crescimento inicial do cacto mandacaru (Cereus jamacaru DC.). Braz. J. Bot. 2024, 47, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyzanowski, FC; Dias, DCFS; França Neto, JB. Deterioração e vigor da semente, 1st ed.; Embrapa: Londrina, Brasil, 2022; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Guedes, RS; Alves, EU; Gonçalves, EP; Bruno, RDLA; Braga Júnior, JM; Medeiros, MS. Germinação de sementes de Cereus jamacaru DC. em diferentes substratos e temperaturas. Acta Scientiarum Biological Sciences 2009, 31, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C; Shen, Y; Shi, F. Effect of Temperature, Light, and Storage Time on the Seed Germination of Pinus bungeana Zucc. ex Endl.: The Role of Seed-Covering Layers and Abscisic Acid Changes. Forests 2020, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abud, FH; Pereira, MS; Gonçalves, NR; Pereira, DS; Bezerra, ME. Germination and morphology of fruits, seeds and plants of Cereus jamacaru DC. Journal of Seed Science 2013, 35, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, NLM; Innecco, R; Gomes Filho, E.; Gallão, MI; Pizarro, JCA; Prisco, JT; Oliveira, ABD. Seed reserve composition and mobilization during germination and early seedling establishment of Cereus jamacaru D.C. ssp. jamacaru (Cactaceae). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 2012, 84, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, OJG; Souza, LA; Moscheta, IS. Morfo-anatomia da plântula de indivíduos somaclones de Cereus hildmannianus Schumann (Cactaceae). Boletín de la Sociedad Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Cactáceas y otras Suculentas 2009, 6, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, R; Ri, LD; Singer, RF; Singer, RB. Unveiling the germination requirements for Cereus hildmannianus (Cactaceae), a potential new crop from southern and southeastern Brazil. Acta Botanica Brasilica 2020, 2020(34), 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Meng, J.; Tao, J. Deterioration of orthodox seeds during ageing: Influencing factors, physiological alterations and the role of reactive oxygen species. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2021, 158, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIAS, DCFS Handouts: Curso de Fisiologia de Sementes; Abrates: Londrina, Brasil, 2017.

- Farooq, MA; Zhang, X; Zafar, MM; Ma, W; Zhao, J. Roles of reactive oxygen species and mitochondria in seed germination. Frontiers in plant science 2021, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebone, LA; Caverzan, A; Chavarria, G. Physiologic alterations in orthodox seeds due to deterioration processes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 145, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FV | G (%) | GSI | MGT | v |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storage (A) | p<0,001 | 0,077 | 0,037 | 0,023 |

| Temperature (B) | p<0,001 | p<0,001 | p<0,001 | p<0,001 |

| A x B | p<0,001 | 0,004 | p<0,001 | 0,273 |

| CV (%) | 3,86 | 12,66 | 11,84 | 15,26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).