1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and coronary artery disease (CAD) are two of the most prevalent chronic non-communicable diseases worldwide, representing leading causes of morbidity and mortality [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Recent studies have confirmed a strong association between these conditions, showing that greater COPD severity and the occurrence of exacerbations are associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality [

7,

8,

9,

10]. This association is not merely due to shared risk factors, such as advanced age and, most importantly, cigarette smoking, but also involves common underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, particularly systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction [

11,

12,

13,

14].

The clinical overlap between COPD and CAD is significant. Both conditions can present with symptoms like dyspnea and chest pain, which can lead to diagnostic challenges and potentially delay the recognition and management of CAD in patients with COPD [

15]. Furthermore, the coexistence of these diseases has important prognostic implications. CAD represents the most frequent and significant comorbidity in patients with COPD, accounting for a substantial proportion of hospitalizations and mortality [

16]. Conversely, COPD is a well-established independent risk factor for cardiovascular events and mortality, even after adjustment for smoking history and other traditional risk factors [

17,

18].

Coronary angiography is the gold standard for the definitive diagnosis of CAD, as it allows direct visualization of coronary artery stenosis and an accurate assessment of disease severity and extent. However, studies specifically investigating the angiographic findings in patients with COPD are limited, and the available evidence is conflicting [

19]. Some investigations have reported a higher prevalence of significant coronary artery stenosis, including multi-vessel disease, and more severe atherosclerosis in patients with concomitant COPD and CAD compared to those with CAD alone [

20,

21]. In contrast, other studies have found a negative association between COPD and angiographically confirmed CAD [

22,

23,

24,

25]. These discrepancies highlight a critical knowledge gap and the need for further research aimed at clarifying the angiographic characteristics of CAD in patients with COPD. Given the significant prognostic implications and the potential for under-diagnosis and delayed treatment, a better understanding of the association between COPD and angiographically proven CAD has direct and meaningful clinical implications.

This study aims to evaluate the association between COPD and the presence, severity and extent of CAD, as assessed by coronary angiography, in a cohort of patients undergoing the procedure for suspected or known CAD. Our findings provide a detailed characterization of coronary artery involvement in this high-risk population, which may lead to improve diagnostic accuracy and more informed therapeutic strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

This retrospective observational single-center study enrolled 94 consecutive patients between January 2023 and December 2024 who underwent coronary angiography at San Salvatore Hospital, Pesaro, Italy. Patients were referred for invasive coronary evaluation because of suspected or known CAD, either in the setting of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or chronic coronary syndrome (CCS).

The diagnosis of COPD was established according to Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria, based on post-bronchodilator spirometry [

26]. Patients with GOLD stage 1- 2 COPD were included, defined by a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV₁) > 80% or between 50% and 80% of the predicted value.

Exclusion criteria included a life expectancy < 6 months due to non-cardiovascular conditions and evidence of acute non-ischemic myocardial injury.

Obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) > 29 kg/m². Hyperuricemia was defined as a serum uric acid concentration > 7 mg/dL. Chronic kidney disease was considered present in patients with stage 3b or higher (estimated glomerular filtration rate < 45 mL/min/1.73 m²).

All participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection and analysis. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (CE 67/20) and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Clinical Assessment and Diagnostic Workup

All patients underwent comprehensive clinical evaluation, including collection of demographic data, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities, and ongoing pharmacological therapy. Recorded treatments included dual antiplatelet therapy, prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin (4000 IU subcutaneously once daily), high-intensity statin therapy (rosuvastatin or atorvastatin), beta-blockers (metoprolol or bisoprolol), and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers.

All patients underwent complete laboratory testing, including lipid profile, inflammatory markers, and renal function parameters. Pulmonary function testing was performed to assess inspiratory capacity and FEV₁. Standard 12-lead electrocardiography was obtained using a Mortara ELI 280 system, and transthoracic echocardiography was performed using a Philips Epiq 7 ultrasound system.

2.3. Clinical Presentation and Indication for Coronary Angiography

Patients presented either with ACS, including ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), or with CCS. In ACS without persistent ST-segment elevation, risk stratification was performed using the GRACE score, in accordance with European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines [

27].

Patients with unstable angina or NSTEMI were classified as very high risk or high risk based on ESC criteria. Very high-risk patients underwent immediate invasive evaluation (within 2 h), while high-risk patients underwent early invasive evaluation (preferably within 24 h). STEMI patients were referred directly to the catheterization laboratory for immediate reperfusion.

Patients with CCS underwent coronary angiography based on evidence of inducible ischemia documented by functional or imaging tests. Revascularization criteria were consistent with the ISCHEMIA trial and included left main coronary artery involvement, proximal left anterior descending artery disease, ischemic burden > 9%, or evidence of myocardial viability (≥ 11 segments on SPECT, ≥ 5 segments on stress echocardiography, or ≥ 3 segments on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging).

Some patients were referred for coronary angiography in the setting of decompensated congestive heart failure when ischemic etiology was suspected.

2.4. Coronary Angiography Assessment

Coronary angiography was performed according to standard institutional practice using selective catheterization of the coronary arteries [

28]. Angiograms were analyzed to determine the presence, extent, and anatomical distribution of CAD. The number of significantly diseased vessels was recorded, and coronary arteries were further classified according to anatomical location (right

vs. left coronary circulation) and vessel diameter. The left main coronary artery was analyzed separately as a large-caliber vessel (> 4 mm), intermediate-caliber vessels (3–4 mm) included the left anterior descending, left circumflex, and right coronary arteries, while smaller-caliber branches (< 3 mm) were analyzed as a separate category.

2.5. Endpoints and Statistical Analysis

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the association between COPD and CAD, with specific focus on the number, anatomical distribution, and caliber of coronary vessels involved.

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as absolute number and percentage. Differences between COPD and non-COPD groups were assessed using the Student’s t-test for continuous variables (age and BMI) and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The distribution of the number and type of coronary vessels involved was analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. A p-value of < 0.05 considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population

A total of 94 patients were included in the study, of whom 47 had a confirmed diagnosis of COPD and 47 served as the non-COPD comparison group. The mean age of the overall cohort was 76.0 ± 8.6 years, with no statistically significant difference between COPD and non-COPD patients (77.3 ± 8.2 vs. 74.8 ± 8.8 years, p = 0.1566). Most participants were male (71/94, 75.5%), and sex distribution was comparable between groups (74.5% vs. 76.6%, p > 0.9999).

Mean body mass index (BMI) was 25.1 ± 5.7 kg/m², with no significant differences between COPD and non-COPD patients (25.4 ± 5.1 vs. 24.9 ± 6.3 kg/m², p = 0.6369). A history of current or former smoking was reported in 47 patients (50%), with similar prevalence in the COPD and non-COPD groups (53% vs. 47%).

Pulmonary function data were available for all patients, and showed a mean FEV₁/FVC ratio of 64.9 ± 6.4% and a mean FEV₁ of 80.5 ± 13.8% of predicted for COPD patients, consistent with GOLD stage 1-2 disease. The mean BODE index in the COPD group was 3.7 ± 1.7.

Laboratory parameters, including fibrinogen, lipid profile, C-reactive protein (CRP), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), were comparable between groups. Cardiac functional assessment showed a mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 48.8 ± 11.1% in the overall cohort, with no significant difference between COPD and non-COPD patients. Estimated systolic pulmonary arterial pressure was also similar between groups (29.3 ± 10.5 vs. 27.2 ± 8.2 mmHg).

The clinical presentation leading to coronary angiography included STEMI, NSTEMI, and congestive heart failure (CHF), with distributions summarized in

Table 1. Overall, baseline demographic, clinical, pulmonary, laboratory, and echocardiographic characteristics were well balanced between COPD and non-COPD patients.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

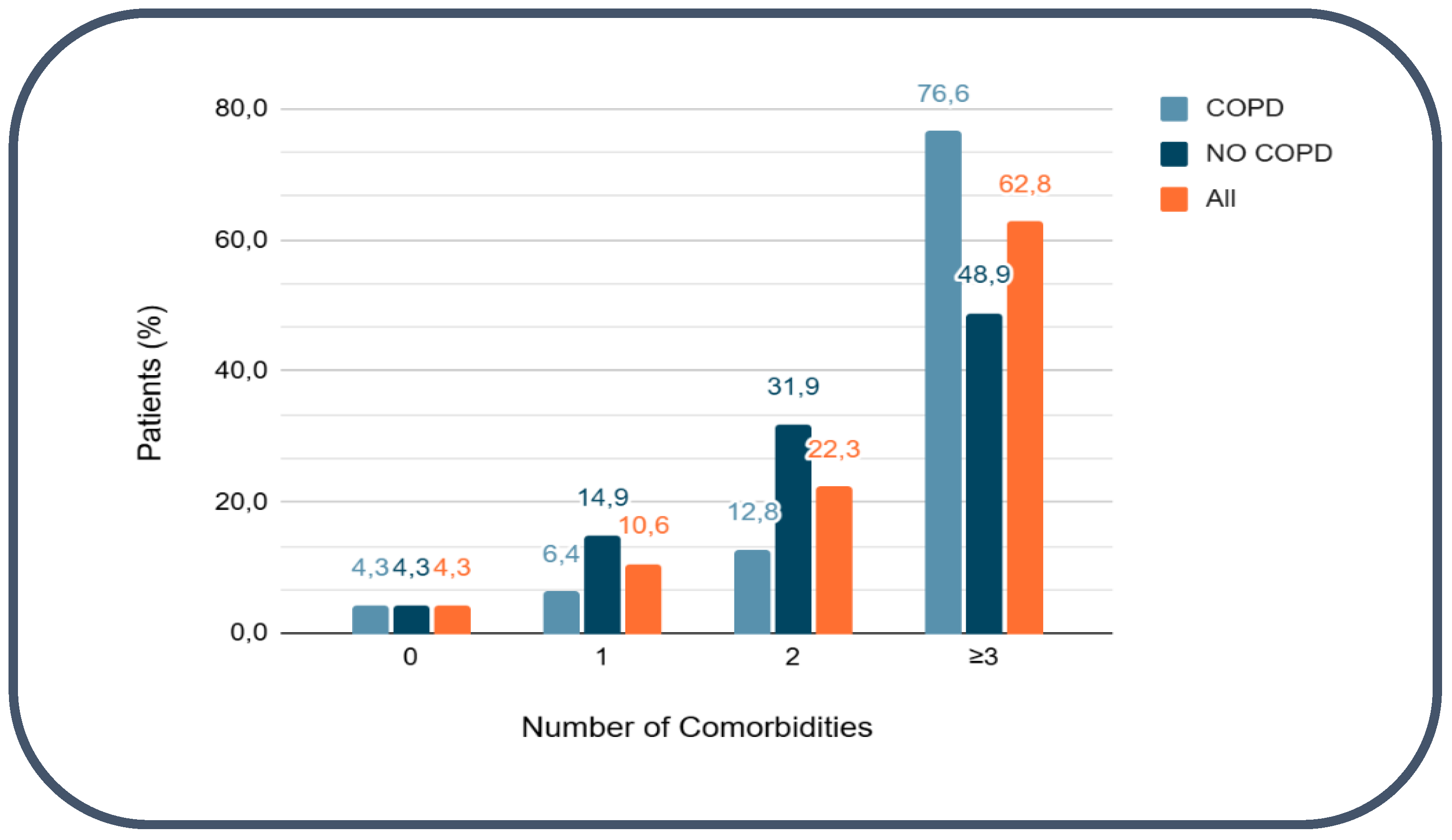

3.2. Cardiovascular comorbidities Counts and Multimorbidity

Cardiovascular comorbidities were highly prevalent in the study population. Only 4 patients (4.3%) had no documented cardiovascular comorbidities, whereas the vast majority (90/94, 95.7%) presented with at least one cardiovascular condition. Multimorbidity was common: 59 patients (62.8%) had three or more cardiovascular comorbidities. The most frequently observed conditions were arterial hypertension (79/94, 84%) and dyslipidemia (78/94, 83%). Diabetes mellitus was present in 31 patients (33%), obesity in 19 (20.2%), hyperuricemia in 24 (25.5%), and chronic kidney disease in 26 (28%). Other cardiovascular comorbidities included peripheral arterial disease (12.8%), cerebrovascular disease (13.8%), and atrial fibrillation (29.8%), with similar distribution between COPD and non-COPD groups (

Figure 1). Detailed distributions according to COPD status are shown in

Table 2.

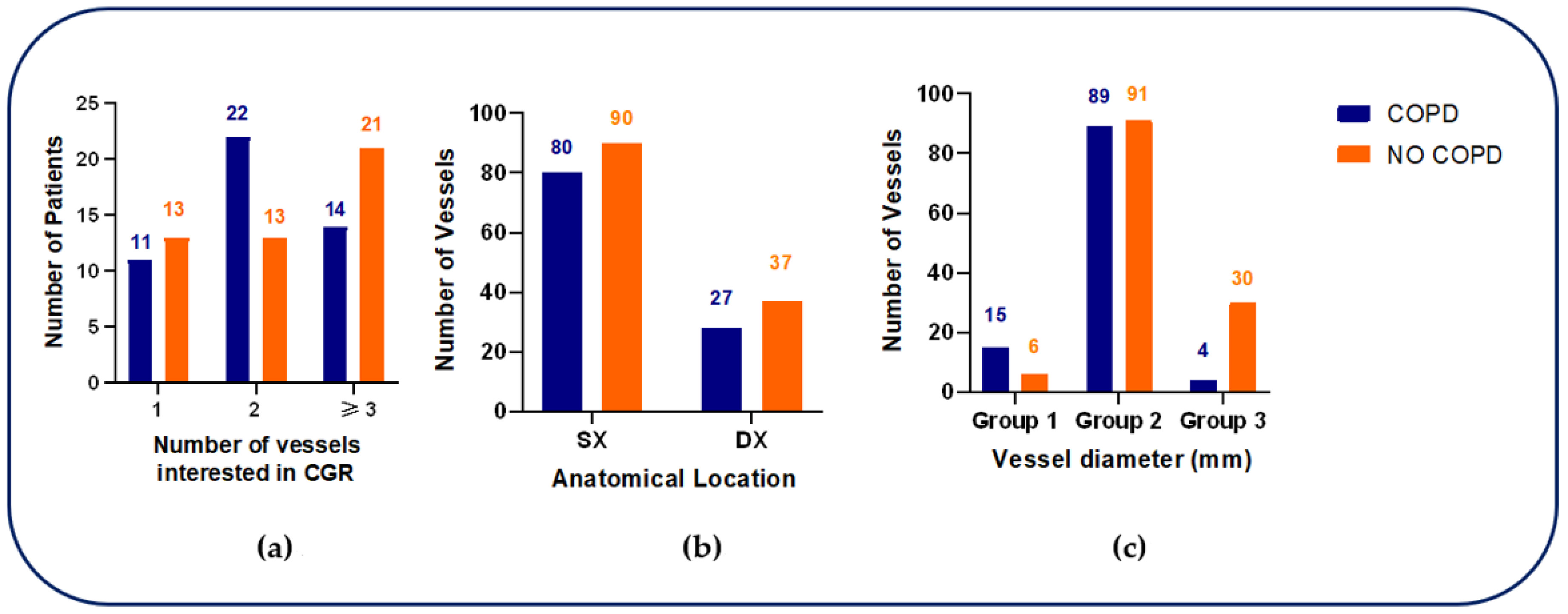

3.3. Coronary Vessel involvement

Coronary angiography revealed differences in the distribution of vessel involvement between groups. Among COPD patients, two-vessel disease was most frequent (22/47, 47%), followed by three-vessel disease (14/47, 30%) and single-vessel disease (11/47, 23%). Conversely, non-COPD patients more commonly displayed three-vessel disease predominated (21/47, 44.6%), with lower frequencies of two-vessel (13/47, 27.7%) and single-vessel disease (13/47, 27.7%). Overall, the distribution of the number of diseased vessels did not differ significantly between groups (p = 0.1436).

When coronary lesions were classified according to anatomical circulation, most lesions involved the left coronary circulation in both groups (74% in COPD

vs. 71% in non-COPD), with no significant difference (

p = 0.6612). In contrast, stratification by vessel diameter revealed a distinct pattern. In COPD patients, disease affecting the left main coronary artery (Group 1: LMCA; diameter > 4 mm) was significantly more frequent than in non-COPD patients (15/108 vessels, 14%

vs. 6/127 vessels, 4.7%;

p < 0.001). Intermediate-caliber vessels (Group 2: 3-4 mm), including the left anterior descending (LAD), left circumflex (LCX), and right coronary arteries (RCA), accounted for the majority of lesions in both groups (82%

vs. 71.7%). Conversely, small-caliber branches (Group 3: < 3 mm) were less frequently involved in COPD patients compared with non-COPD patients (4%

vs. 23.6%) (

Figure 2).

Taken together, these findings indicate a disproportionate burden of left main CAD in patients with COPD, despite a similar overall extent of CAD as judged by the number of affected vessels. Detailed angiographic findings are reported in

Table 3.

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the association between COPD and the severity of ischemic heart disease, assessed through coronary angiography. Although no significant differences were observed in the overall number of affected coronary vessels between patients with and without COPD, the presence of COPD was associated with a higher frequency of LMCA disease. This finding suggests that COPD may be linked not to a greater extent of coronary atherosclerosis per se, but rather to a distinct and prognostically unfavorable pattern of coronary involvement.

The association between COPD and ischemic heart disease is well established, with COPD recognized as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events and cardiovascular mortality [

8,

23,

24,

29,

30]. However, evidence derived from coronary angiographic studies has remained inconsistent [

12]. While some studies have reported a higher prevalence of multivessel stenosis in COPD patients, others have failed to demonstrate meaningful differences in angiographic burden compared with non-COPD populations [

19,

23,

24,

25]. In this context, the present observation of a disproportionate involvement of LMCA in COPD patients adds a novel and clinically relevant element, given the well-known association between LMCA disease, adverse cardiovascular outcomes, and the need for timely and aggressive revascularization strategies.

Several pathophysiological mechanisms may underlie the preferential involvement of LMCA observed in COPD patients. Chronic systemic inflammation represents a central contributor. COPD is characterized by a persistent low-grade inflammatory state that extends beyond the pulmonary compartment and remains detectable even during clinical stability. This sustained inflammatory burden accelerates atherosclerotic progression and plaque vulnerability. Recent population-based studies have unveiled a strong association between systemic inflammatory markers in COPD and increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [

8,

31], supporting the hypothesis that inflammation-related vascular injury may preferentially affect large-caliber coronary vessels such as LMCA [

32].

Endothelial dysfunction and platelet activation represent additional mechanistic pathways linking COPD to coronary atherosclerosis. Chronic hypoxemia, oxidative stress, and systemic inflammation promote impaired nitric oxide bioavailability, endothelial injury, and enhanced platelet activation, amplifying vascular damage and atherothrombotic risk [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Furthermore, recent evidence indicates that endothelial dysfunction is particularly pronounced in COPD patients, especially in those with more severe airflow limitation or frequent exacerbations, further linking COPD pathophysiology to accelerated coronary atherosclerosis [

38].

Hemodynamic alterations may also contribute to the preferential involvement of proximal coronary segments observed in patients with COPD. Lung hyperinflation and increased intrathoracic pressure, common in advanced disease, can impair diastolic coronary perfusion and modify cardiac geometry, thereby affecting coronary flow reserve [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. These mechanical effects may disproportionately impact large-caliber proximal vessels such as the LMCA, which are particularly sensitive to changes in shear stress and transmural pressure. Although this mechanism has been less extensively investigated, analyses of cardiopulmonary and hemodynamic interactions support the hypothesis that COPD-related mechanical stress increases the vulnerability of proximal coronary segments [

44,

45].

In addition to mechanical factors, shared cardiovascular risk factors likely amplify the burden of proximal coronary disease in COPD patients. In the present cohort, smoking exposure, metabolic abnormalities, and cardiovascular multimorbidity were highly prevalent, all of which are well-established contributors to coronary atherosclerosis. Emerging biomarkers further reinforce this link. In particular, the monocyte-to-HDL ratio (MHR), recently proposed as a predictor of CAD specifically in COPD patients, reflects a pro-inflammatory and pro-atherogenic milieu that may predispose to more severe or proximally located coronary lesions [

46]. Taken together, these observations support the hypothesis that COPD is associated with a distinct inflammatory–atherosclerotic phenotype, which may explain the higher prevalence of LMCA disease observed in our study.

The finding of more frequent LMCA involvement in COPD patients carries important clinical implications, First, it underscores the need for earlier and more accurate cardiological evaluation in COPD patients, in whom symptoms of CAD may be masked by or misattributed to COPD, potentially leading to delayed diagnosis. Awareness of the increased likelihood of high-risk coronary lesions is therefore essential. Second, these data highlight the value of a multidisciplinary approach integrating pulmonologists and cardiologists to optimize diagnostic processes and therapeutic decision-making. Enhanced cardiovascular risk stratification may be particularly warranted in patients with more severe disease or frequent exacerbations, as LMCA involvement often requires revascularization, and COPD status may influence the choice between percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass grafting due to increased perioperative risk. Finally, previous evidence indicating that COPD worsening is associated with a marked increase in cardiovascular risk [

47] further reinforces the importance of close cardiac surveillance following exacerbation events.

This study has several strengths, including a detailed angiographic evaluation with vessel-specific and diameter-based classification, which allowed us to identify disease patterns not captured by conventional analyses. In addition, the careful matching of COPD and non-COPD groups reduces the impact of potential confounding factors. Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. The retrospective, single-center design inherently restricts the generalizability of our findings, and the relatively small sample size may have limited statistical power for selected comparisons. Moreover, the lack of stratification according to COPD severity or exacerbation history precludes the evaluation of potential dose–response relationships. Finally, the absence of longitudinal follow-ups prevented us from determining the prognostic implications of the observed angiographic differences.

Future prospective, multicenter studies with larger cohorts, comprehensive clinical phenotyping, and long-term outcome data are thus needed to validate these results and to further elucidate the mechanisms linking COPD to specific patterns of CAD.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, although the overall angiographic burden of CAD did not differ between patients with and without COPD, our findings demonstrate that COPD is associated with a distinct pattern of coronary involvement characterized by a higher prevalence of LMCA disease. This observation suggests that COPD may influence not only the risk of developing coronary atherosclerosis but also its anatomical distribution, favoring the involvement of proximal, prognostically critical segments.

Besides shared traditional cardiovascular risk factors, the available evidence supports the concept that COPD is linked to systemic inflammatory, endothelial, and hemodynamic alterations that may accelerate atherosclerotic remodeling in large-caliber coronary vessels. Within this framework, LMCA disease may represent a marker of a broader, high-risk cardiovascular phenotype rather than an isolated angiographic finding. Recognizing this phenotype has important clinical implications, as proximal coronary involvement is strongly associated with adverse outcomes and often requires timely and complex revascularization strategies.

From a clinical perspective, these results reinforce the need for heightened cardiovascular awareness and proactive assessment in patients with COPD, particularly in those with advanced disease or frequent exacerbations. An integrated approach combining angiographic findings with clinical presentation, inflammatory biomarkers, and functional assessments may enhance risk stratification, facilitate earlier detection of high-risk coronary disease, and support more individualized therapeutic decision-making.

Future studies incorporating longitudinal follow-up and comprehensive phenotyping will be essential to determine whether this distinct coronary pattern translates into differential outcomes and to define optimal preventive and interventional strategies for this vulnerable population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.R. and M.M.; methodology, B.R.; software, C.B. and F.C.; validation, L.B., and G.T.; formal analysis, C.B. and F.C.; resources, L.B., and G.T.; data curation, C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, B.R.; writing—review and editing, M.M.; supervision, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Alessandria (protocol code CE 67/20 on date 24 april 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CAD |

Coronary Artery Disease |

| GOLD |

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| LMCA |

Left Main Coronary Artery |

| ACS |

Acute Coronary Syndrome |

| CCS |

Chronic Coronary Syndrome |

| FEV1 |

Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second |

| IU |

International Unit |

| STEMI |

ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

| NSTEMI |

non-ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

| GRACE |

Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events |

| ESC |

European Society of Cardiology |

| SPECT |

Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| FVC |

Forced Vital Capacity |

| FEV1/FVC |

Tiffeneau Index |

| BODE |

Body-mass index, Obstruction, Dyspnea, Exercise |

| CRP |

C-Reactive Protein |

| ESR |

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate |

| LVEF |

Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction |

| LAD |

Left Anterior Descending |

| LCX |

Left Circumflex |

| RCA |

Right Coronary Arteries |

| MHR |

Monocyte-to-HDL Ratio |

References

- Wang Y, Han R, Ding X, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease across three decades: trends, inequalities, and projections from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Front Med. 2025;12:1564878. [CrossRef]

- de Oca MM, Perez-Padilla R et al. The global burden of COPD: epidemiology and effect of prevention strategies. Lancet Respir Med. 2024;12(3):339–352.

- Mensah GA, Fuster V, et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks Collaboration, 1990–2022. J Am Coll Cardiol (JACC). 2023;82:2350–2473.

- Pant S. Cardiovascular conditions lead global disease burden over the past 30 years. JAMA. 2025;334(19):1698. [CrossRef]

- Boers E, Allen A et al. Forecasting the Global Economic and Health Burden of COPD From 2025 Through 2050. CHEST. 2025;168(4):743–755.

- Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2023. JACC. 2025; [CrossRef]

- Nowbar AN, Gitto M et al. Mortality from Ischemic Heart Disease Analysis of Data from the World Health Organization and Coronary Artery Disease Risk Factors from NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2019;12(6). [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Li F et al. Additive impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) on all-cause and disease-Specific mortality: a longitudinal nationwide population-based study. BMC Pulm Med.2025; May 31;25(1):275. [CrossRef]

- Yang H, Ryu MH et al. Differential Association of COPD Subtypes With Cardiovascular Events and COPD Exacerbations. Chest. 2024 Dec;166(6):1360-1370. Epub 2024 Jul 31. [CrossRef]

- Morgan C, Challen R et al. Acute coronary syndrome after an infective exacerbation of COPD: a prospective cohort study of acute lower respiratory tract disease in hospitalised adults. ERJ Open Res. 2025 Dec 15;11(6):00403-2025. eCollection 2025 Nov. [CrossRef]

- Ragnoli B, Chiazza F, et al. Biological pathways and mechanisms linking COPD and cardiovascular disease. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 2025(16): 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Papaporfyriou A, Bartziokas K et al. Cardiovascular diseases in COPD: From Diagnosis and Prevalence to Therapy. Life. 2023;13(6):1299.

- Gan W Q, Man S F P et al. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2004 Jul;59(7):574-80. [CrossRef]

- Marcuccio G, Candia C, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an update on mechanisms, assessment tools and treatment strategies. Front Med. 2025;12:1550716.

- Beyer C, Pizzini A et al. Underappreciation of coronary artery disease in patients with COPD. European Respiratory Journal 2020 56(suppl 64): 5116. [CrossRef]

- Cao Z He L et al. Burden of chronic respiratory diseases and their attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2021: Results from the global burden of disease study Chin Med J Pulm Crit Care Med 2025 Jun 14;3(2):100-110. [CrossRef]

- Lin W, Chen C et al. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a 13-year nationwide cohort study. European Respiratory Journal 2017 50(suppl 61): PA1570; [CrossRef]

- Zheng Y, Hu Z et al. Global Insights into Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Coronary Artery Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 6,400,000 Patients. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2024 Jan 15;25(1):25. eCollection 2024 Jan. [CrossRef]

- Hong Y, Graham MM et al. The Association between Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Coronary Artery Disease in Patients Undergoing Coronary Angiography. COPD. 2019 Feb;16(1):66-71. Epub 2019 Mar 22. [CrossRef]

- Pereira Ferreira EJ, de Carvalho Cardoso LV et al. Cardiovascular Prognosis of Subclinical Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Patients with Suspected or Confirmed Coronary Artery Disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2023 Aug 29:18:1899-1908. eCollection 2023. [CrossRef]

- Williams MC, Murchison JT et al. Coronary artery calcification is increased in patients with COPD and associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Thorax. 2014 Aug;69(8):718-23. Epub 2014 Jan 28. [CrossRef]

- Pavasini R, Campo G. Complex coexistence of COPD and cardiovascular disease. Thorax. 2025;80(5):267–269.

- Polmana R, Hurst JR, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk in COPD: a state of the art review. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2024;22(4–5):177–191.

- Sá-Sousa A et al. Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with COPD: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024;13(17):5173.

- Bellou V. Quantitative Imaging to Illuminate Cardiovascular Risk in COPD—Progress, Context, and the Path Ahead. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2025;20:4079–4082.

- Diagnosis and Management of COPD: 2025 Report. GOLD; 2025. https://goldcopd.org/2025-gold-report/.

- Byrne R.A.; Rossello X; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. European Heart Journal (2023) 44, 3720–3826. [CrossRef]

- Levine GN, Rao SV, et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2025; [CrossRef]

- Nordon C, et al. The sustained increase of cardiovascular risk following COPD exacerbations: meta-analyses of the EXACOS-CV studies. ERJ Open Res. 2025 Jun 16;11(3):01091-2024. [CrossRef]

- Gale CP, Hurst JR, et al. Identification and management of cardiopulmonary risk in COPD: a multidisciplinary consensus. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2025 Oct 28;32(15):1445-1460. [CrossRef]

- Li T, et al. The association between cardiovascular diseases and their subcategories with the severity of COPD: a large cross-sectional study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2025 Feb 13:12:1502205. [CrossRef]

- Soehnlein O, Lutgens E, et al. Distinct inflammatory pathways shape atherosclerosis in different vascular beds. European Heart Journal. 2025;46(33):3261–3272. [CrossRef]

- Malerba M, Nardin M, et al. The potential role of endothelial dysfunction and platelet activation in the development of thrombotic risk in COPD patients. Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 2017;11(11):885–895. [CrossRef]

- Siragusa S, Natali G, et al. The role of pulmonary vascular endothelium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): does endothelium play a role in the onset and progression of COPD? Exploration of Medicine. 2023;4:1116–1134. [CrossRef]

- Marques P, Bocigas I, et al. Key role of activated platelets in the enhanced adhesion of circulating leucocyte–platelet aggregates to the dysfunctional endothelium in early-stage COPD. Frontiers in Immunology. 2024;15:1441637. [CrossRef]

- Kazemi N, Bordbar A, et al. Molecular insights into the relationship between platelet activation and endothelial dysfunction: molecular approaches and clinical practice. Molecular Biotechnology. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pistenma C.L, Hoffman E.A. et al. Platelet activation and COPD-related clinical and imaging characteristics: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) COPD Study. Respiratory Medicine. 2025;241:108058. [CrossRef]

- Yang H.M, Ryu M.H. et al. COPD Subtypes Are Differentially Associated with Cardiovascular Events and COPD Exacerbations. Chest. 2024;166(6):1360–1370. [CrossRef]

- Wells JM, Washko GR, Han MK, et al. Pulmonary arterial enlargement and acute exacerbations of COPD. NEJM. 2012;367:913–921.

- Smith BM, Prince MR, et al. Implications of lung hyperinflation for cardiac structure and function in COPD. Radiology. 2017;283(3):684-692. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Yamashiro T, et al. Hyperinflated lungs compress the heart during expiration in COPD patients: a dynamic-ventilation CT study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:3511-3519. [CrossRef]

- Watz H, Waschki B, Meyer T, et al. Decreased cardiac chamber sizes and associated clinical outcomes in COPD. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11(9):1340–1350. [CrossRef]

- Kohli P, et al. Cardiopulmonary interactions in COPD: mechanisms and clinical implications. Heart Fail Rev. 2016;21(2):221–228. [CrossRef]

- García-García HM, Gonzalo N, et al. Hemodynamic forces and coronary atherosclerosis: insights from computational modeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(6):654-665. [CrossRef]

- Targeting inflammation in atherosclerosis — from experimental insights to the clinic. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20:589–610. [CrossRef]

- Sun F, Ye M, Jumahan A, et al. MHR as a promising predictor for coronary artery disease in COPD patients: Insights from a retrospective nomogram study. Respir Med. 2025;239:107993. [CrossRef]

- Pirera E, Di Raimondo D, et al. Risk trajectory of cardiovascular events after an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2025;135:74-82. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).