Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

15 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

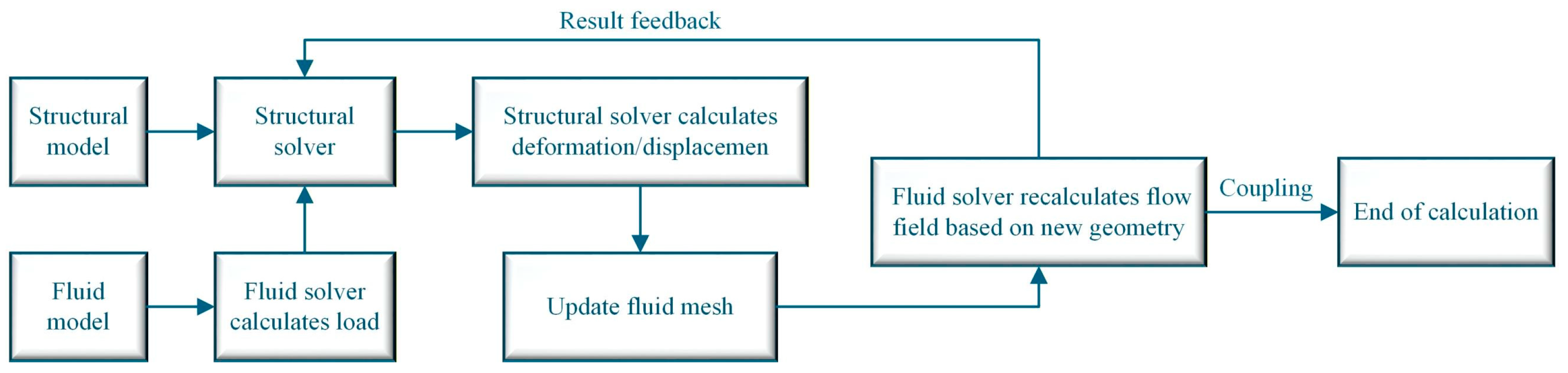

2. Model and Method

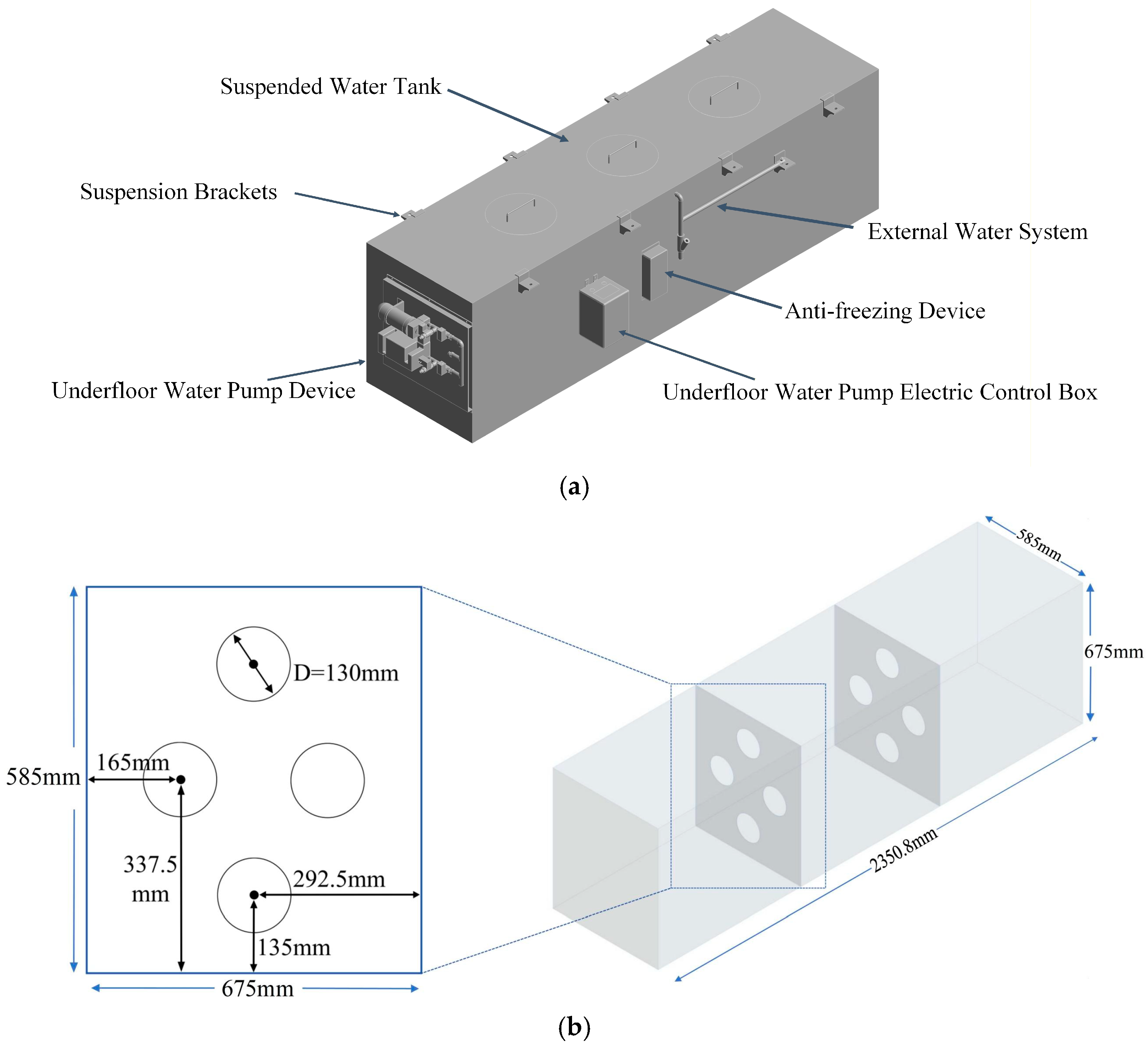

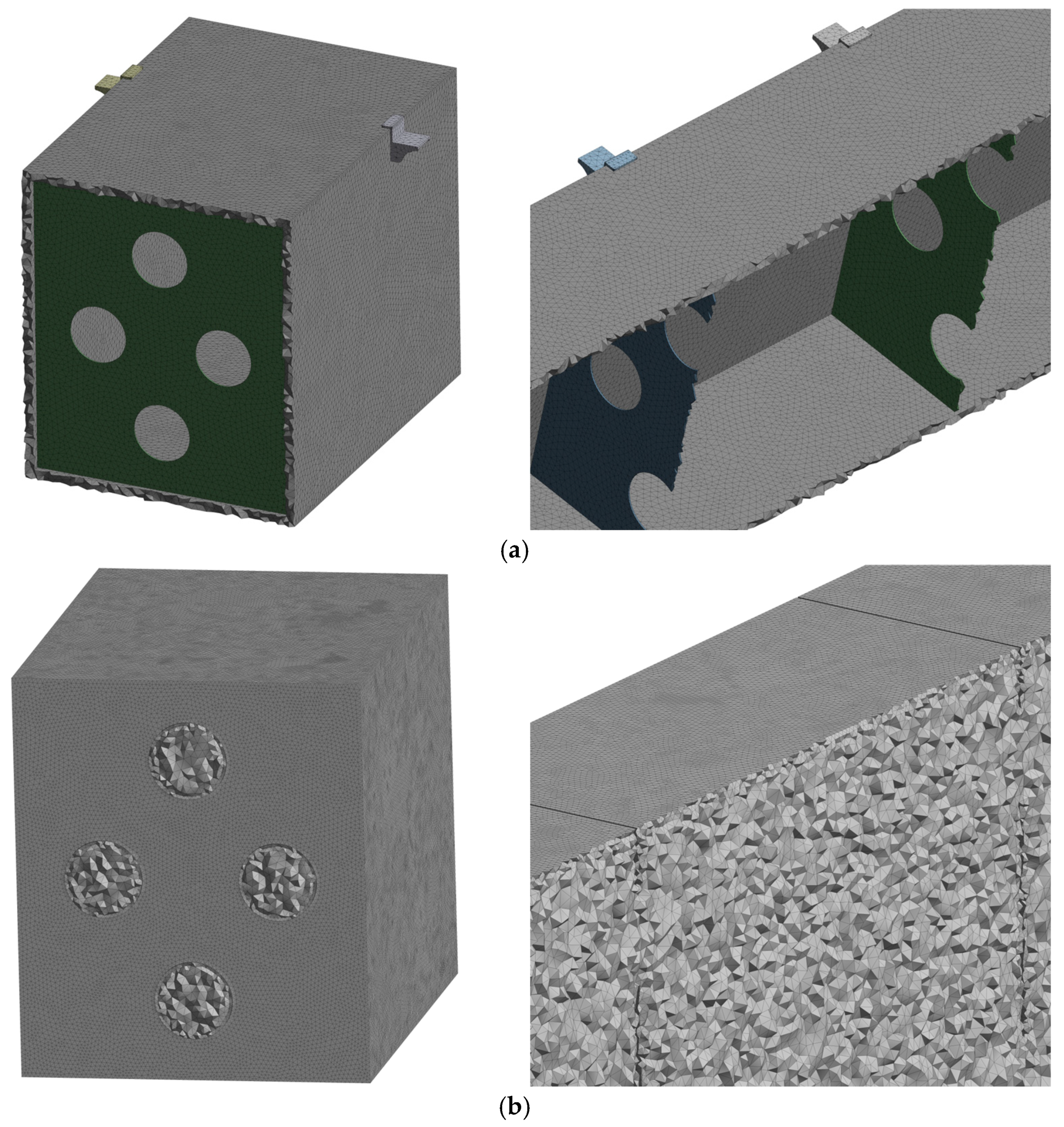

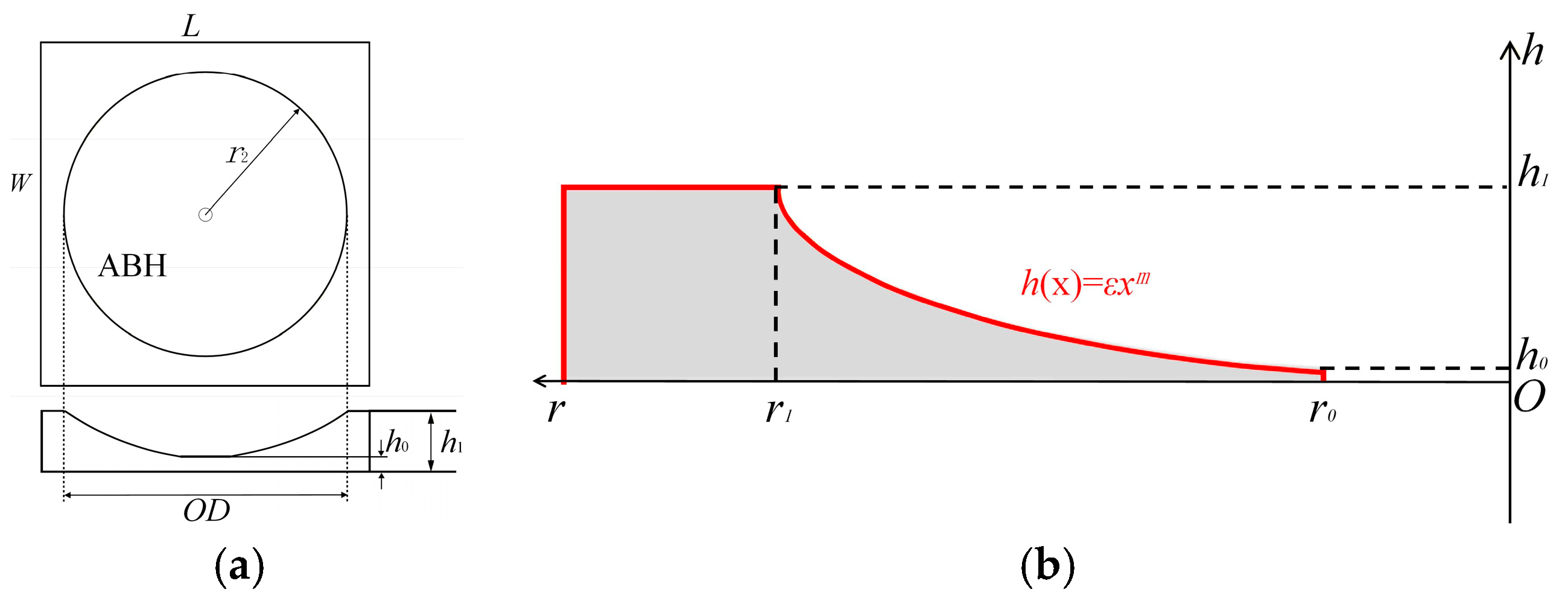

2.1. Model and Mesh Generation

- 1)

- Minor components such as tank water filling holes, overflow holes, cleaning holes, as well as external water pumps, pipes, switches, etc., unrelated to the internal fluid domain, have minimal impact on internal liquid flow and are therefore omitted;

- 2)

- Minor details such as small fillets and rounds that have little impact on structural strength and stiffness are ignored to improve mesh quality and avoid affecting simulation accuracy.

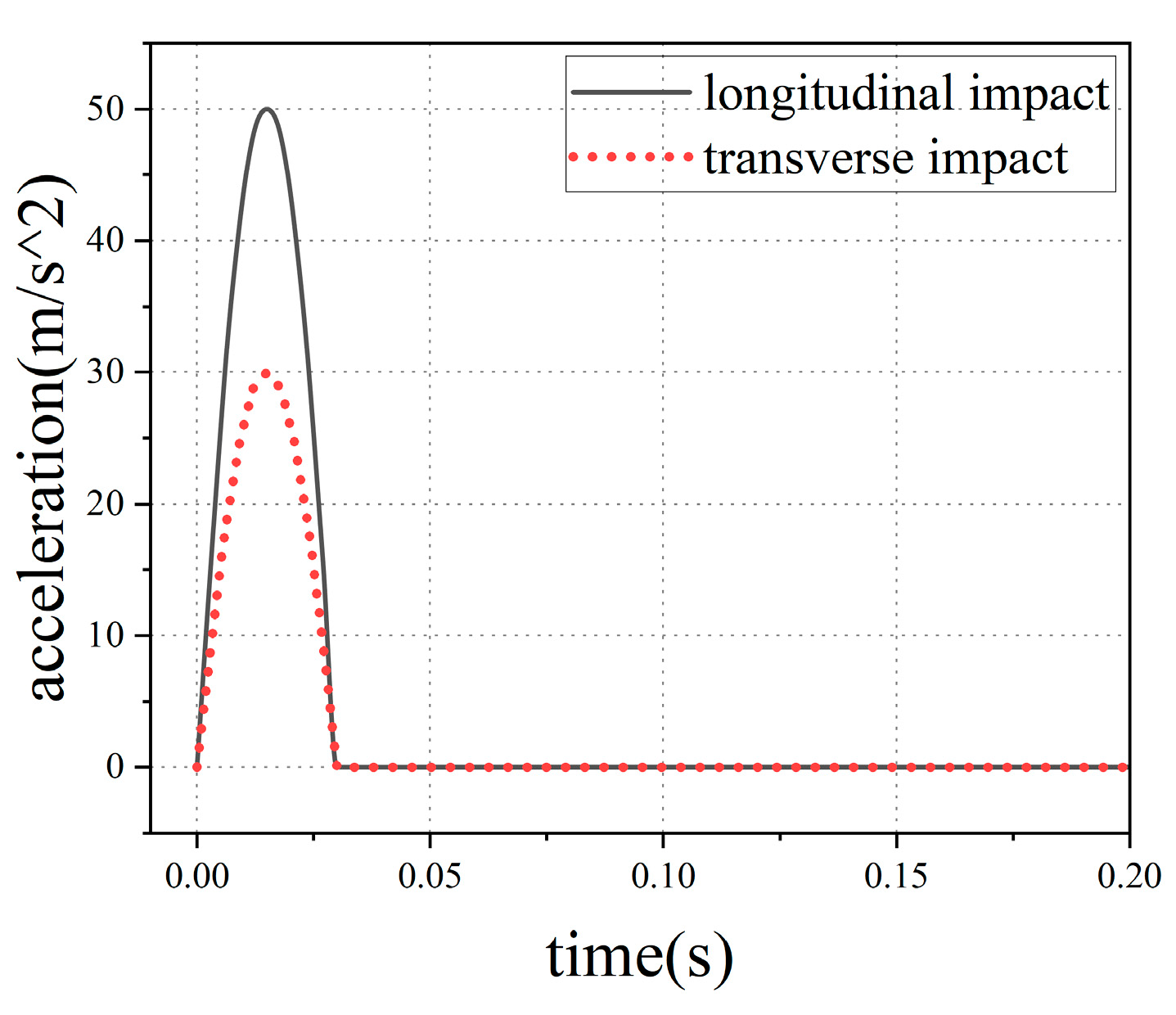

2.2. Boundary Conditions and Method

2.3. Numerical Methods

2.3.1. Flexural Waves in Acoustic Black Hole Structures

2.3.2. Tank Fluid Domain Governing Equations and VOF Model

3. Analysis Process and Results

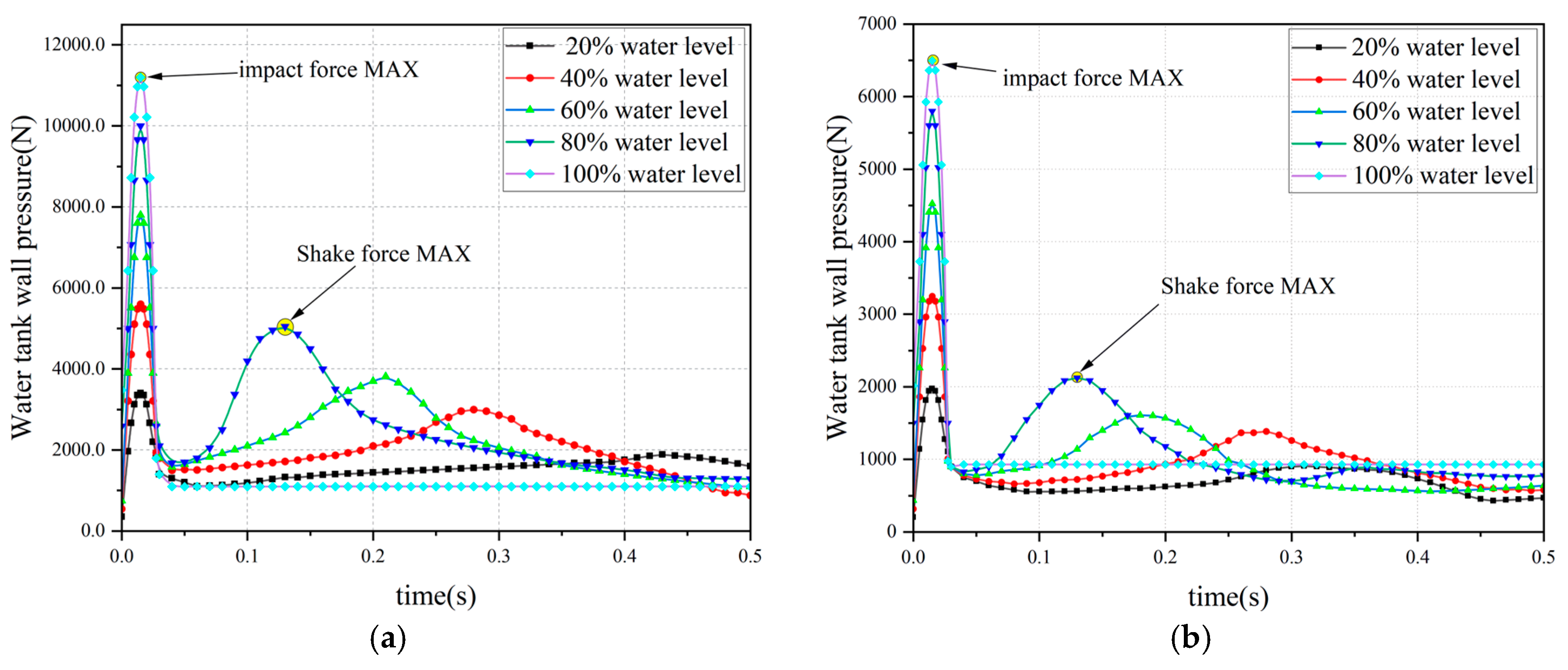

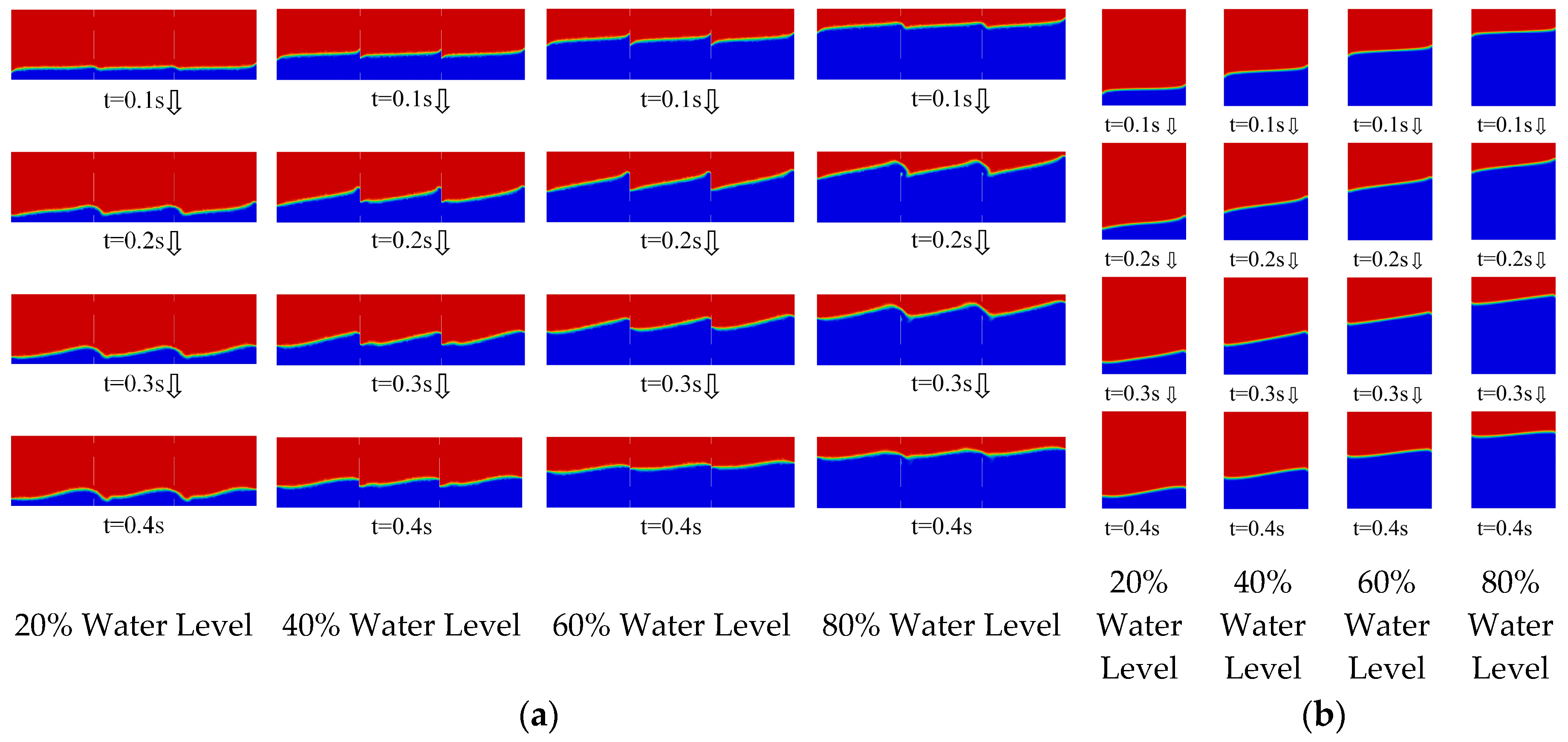

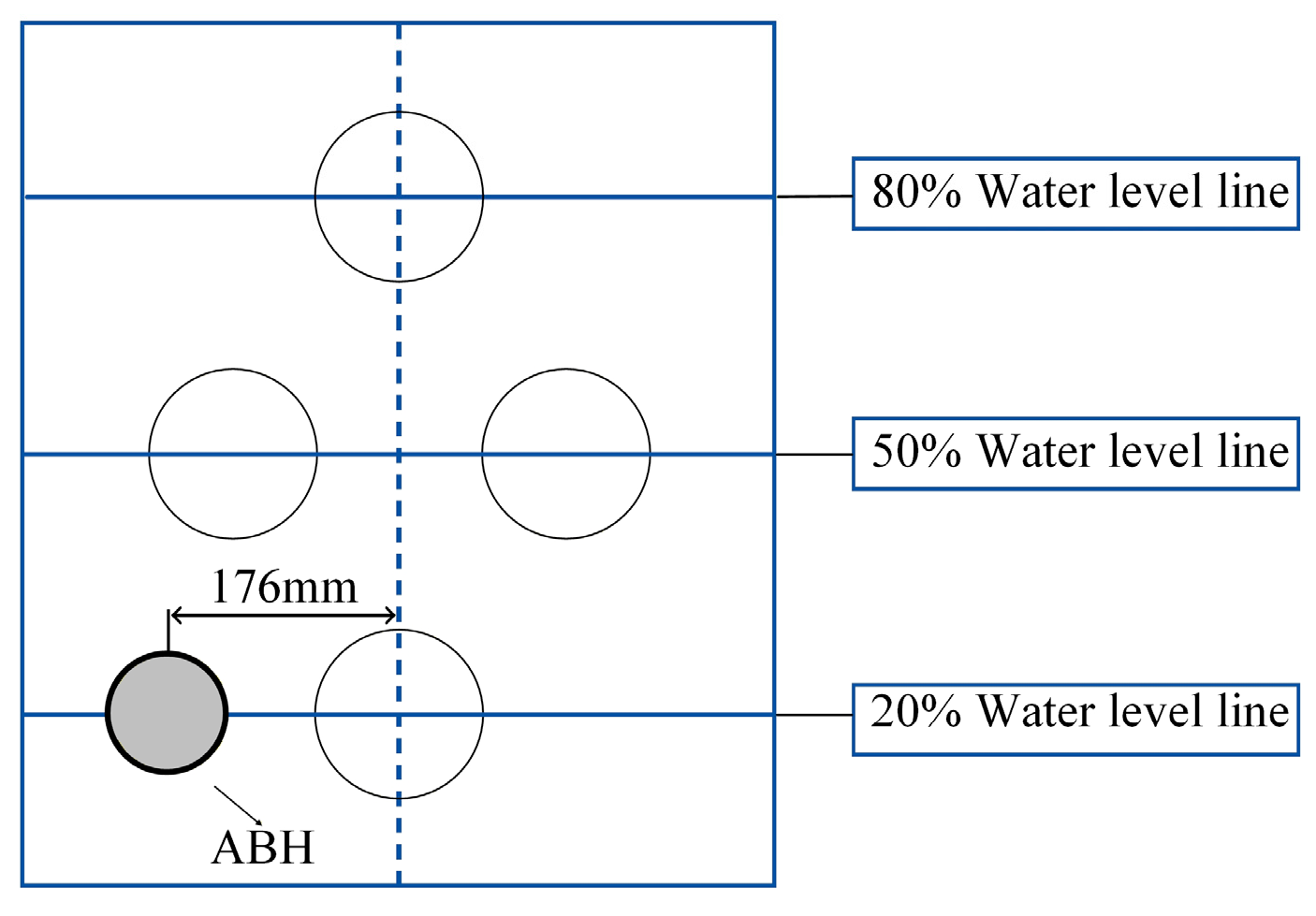

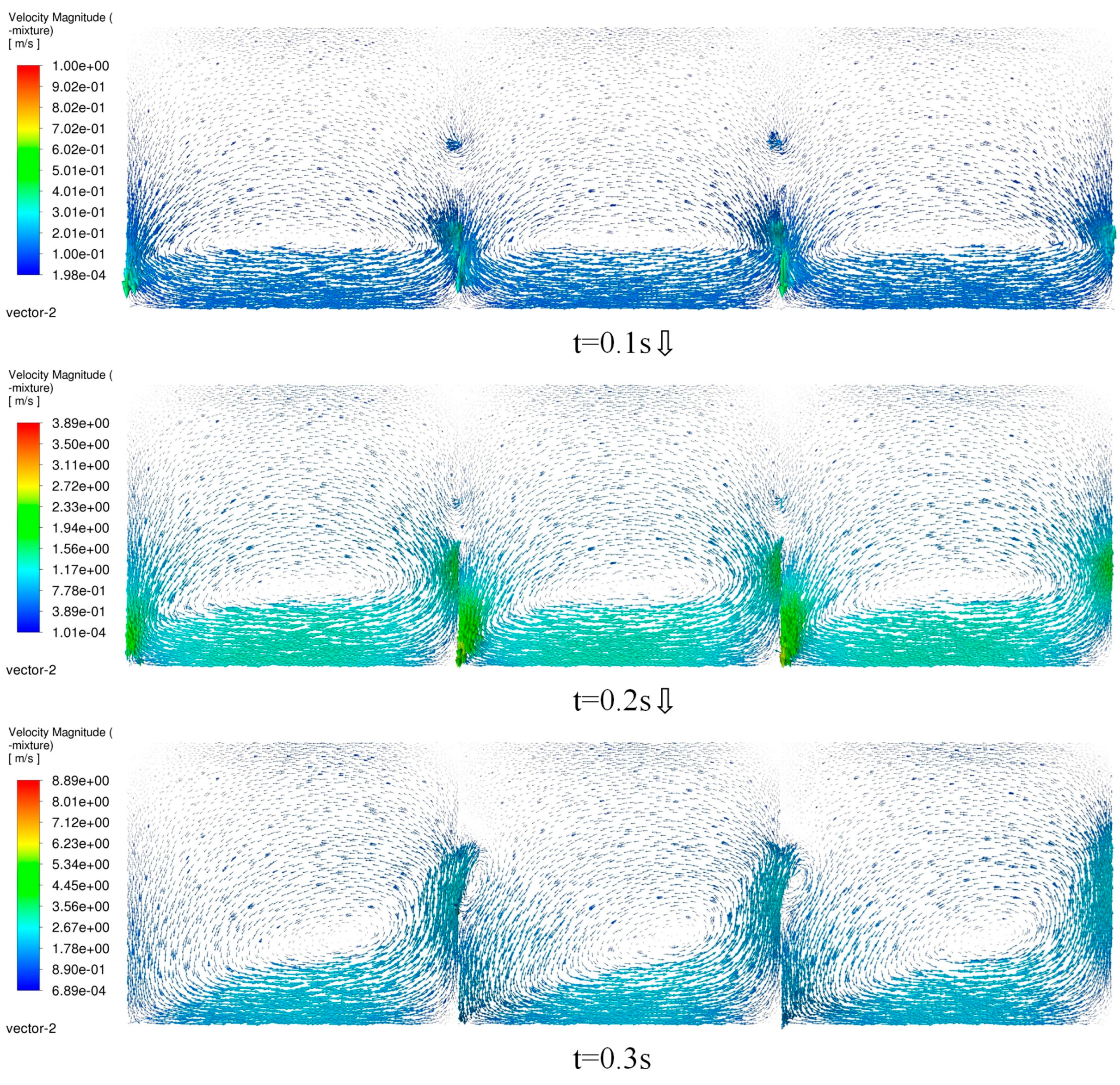

3.1. Analysis of Liquid Surface Evolution Mechanism at Different Water Levels

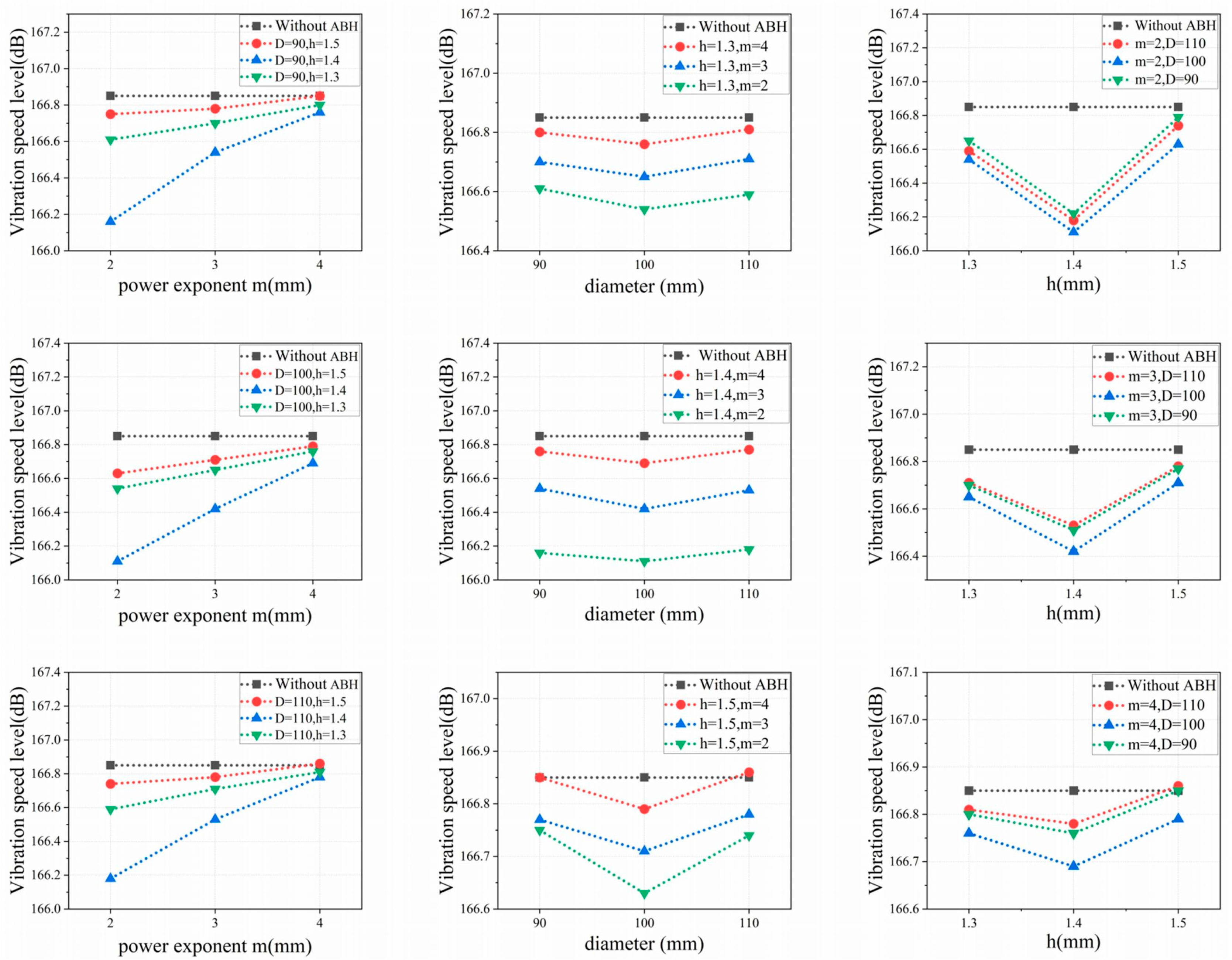

3.2. Determination of Optimal Acoustic Black Hole Parameters

| Level | Considerations | ||

| Truncated thickness h0 (mm) | power exponentm | Diameter D (m) | |

| 1 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.09 |

| 2 | 1.4 | 3 | 0.10 |

| 3 | 1.5 | 4 | 0.11 |

| Considerations | Power law expression | Average vibration speed level(dB) | |||

|

Truncated thickness h0 (mm) |

power exponent m | Diameter D (m) | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | h(x)=0.84x2 | 166.65 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | h(x)=0.68x2 | 166.54 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | h(x)=0.56x2 | 166.59 |

| ...... | |||||

| 25 | 3 | 3 | 1 | h(x)=365.80x4 | 166.85 |

| 26 | 3 | 3 | 2 | h(x)=240.00x4 | 166.79 |

| 27 | 3 | 3 | 3 | h(x)=163.92x4 | 166.86 |

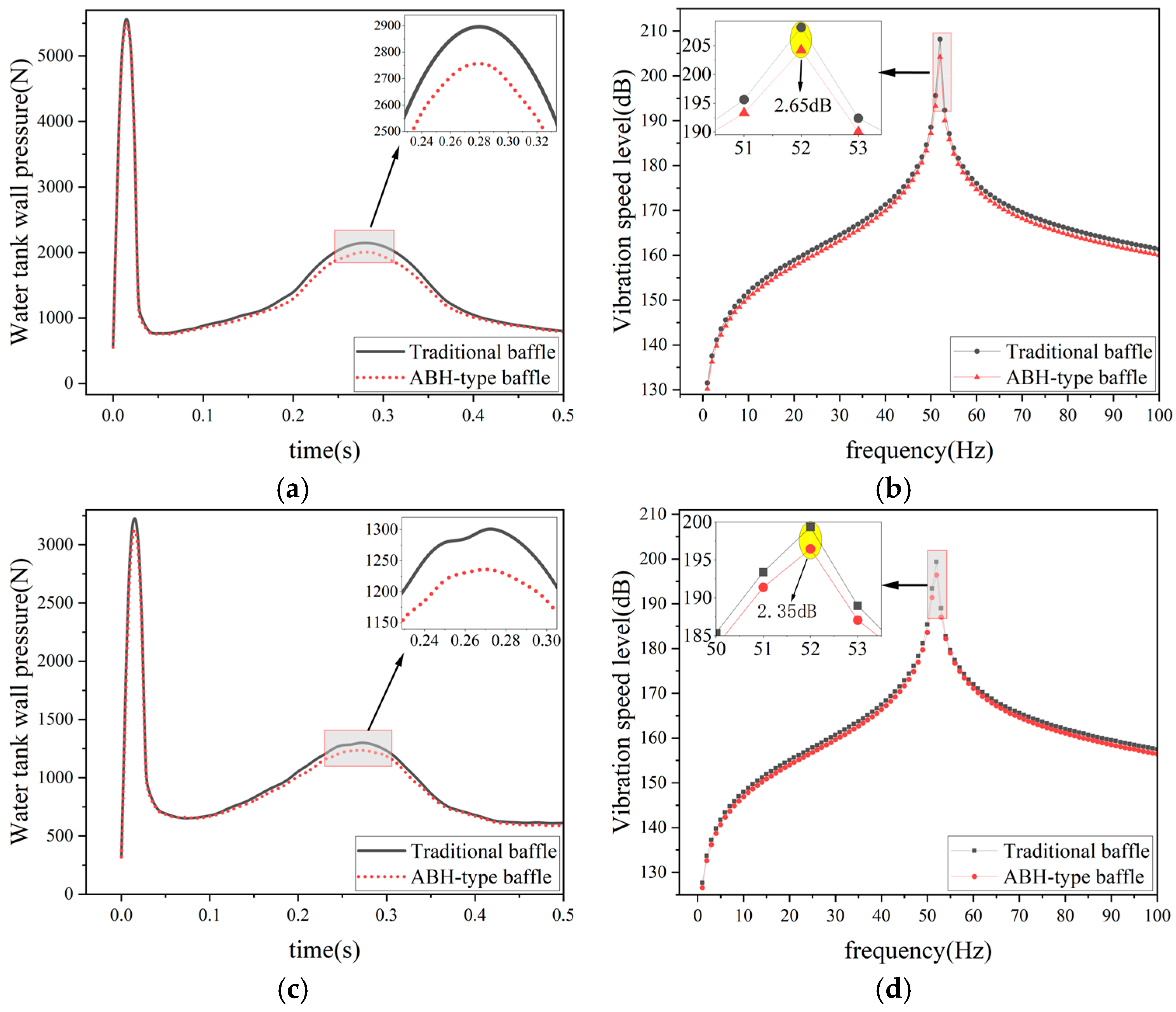

3.3. Study on Sloshing and Vibration Suppression Characteristics of Acoustic Black Hole-Type Baffle

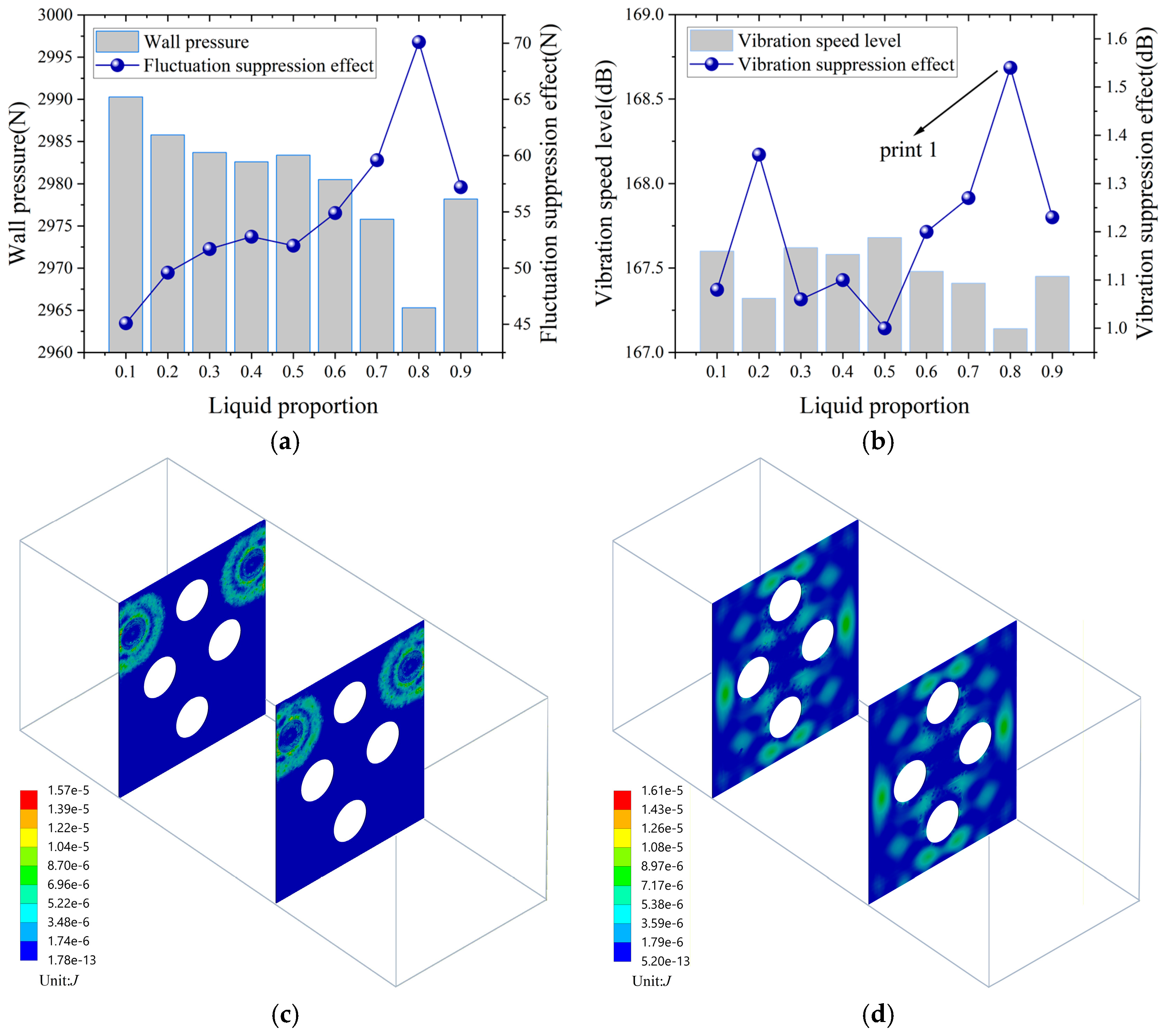

3.4. Single-Factor Analysis Results and Discussion

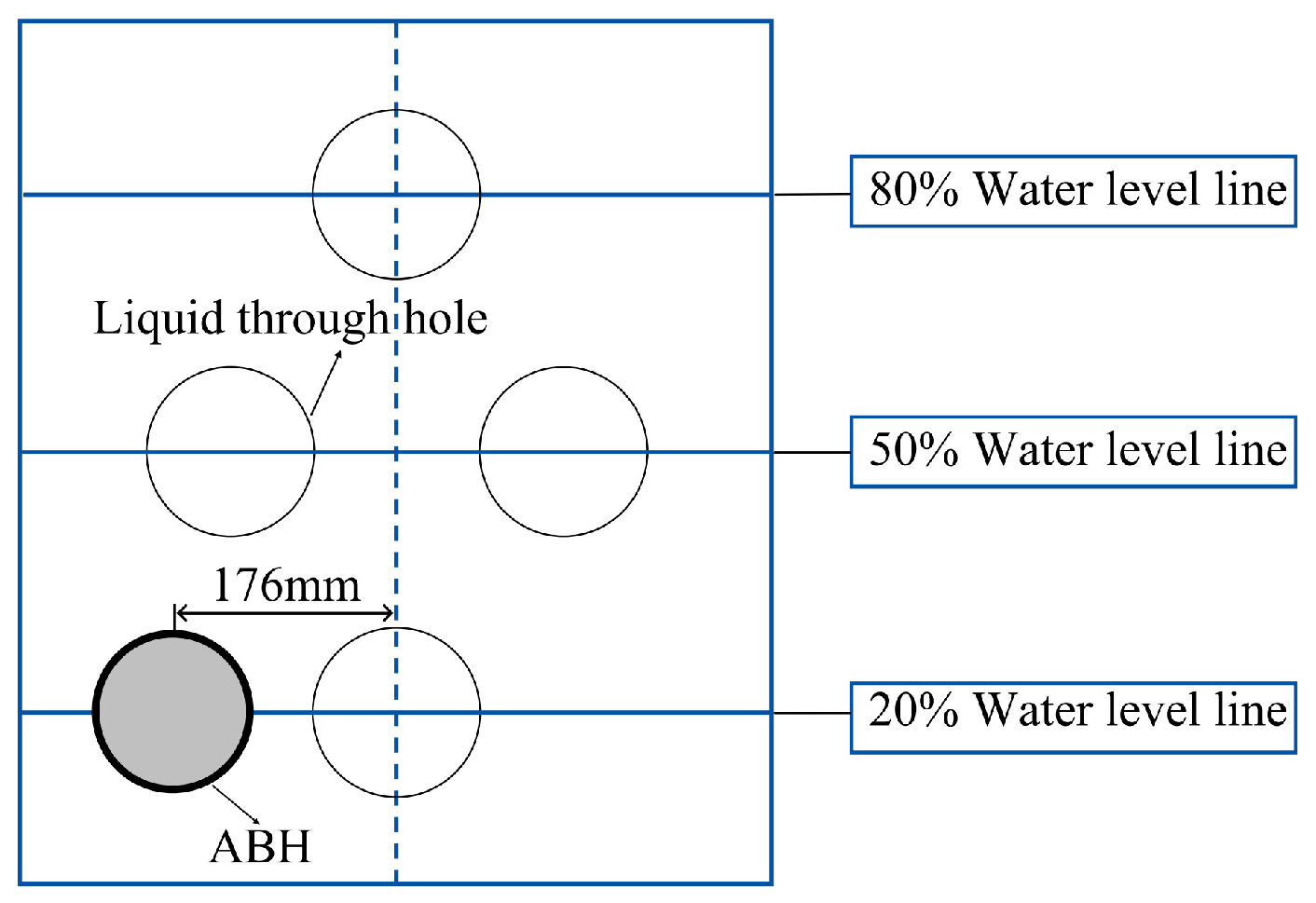

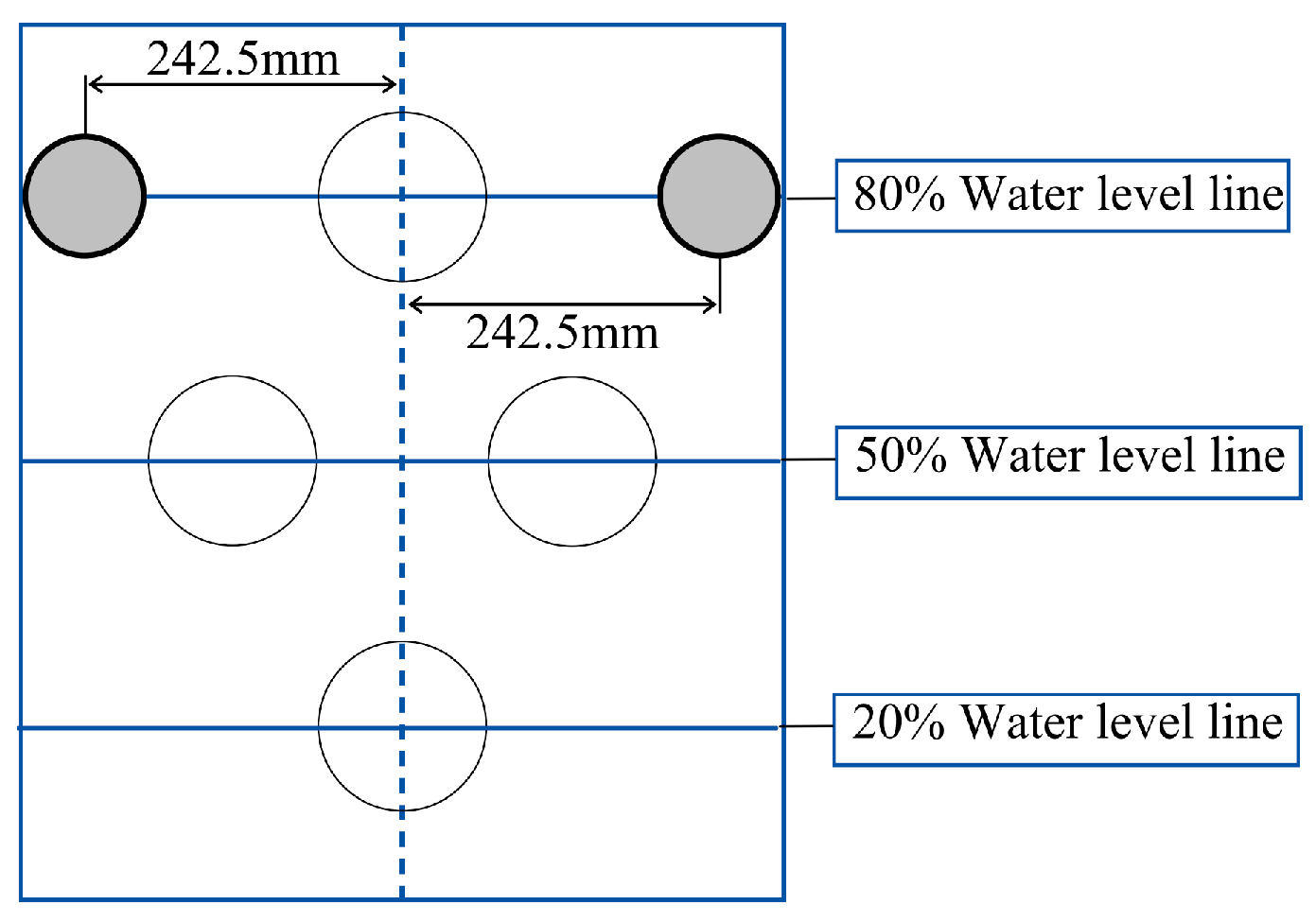

3.4.1. Analysis of the Influence of Acoustic Black Hole Position on Baffle Vibration and Sloshing Suppression Performance

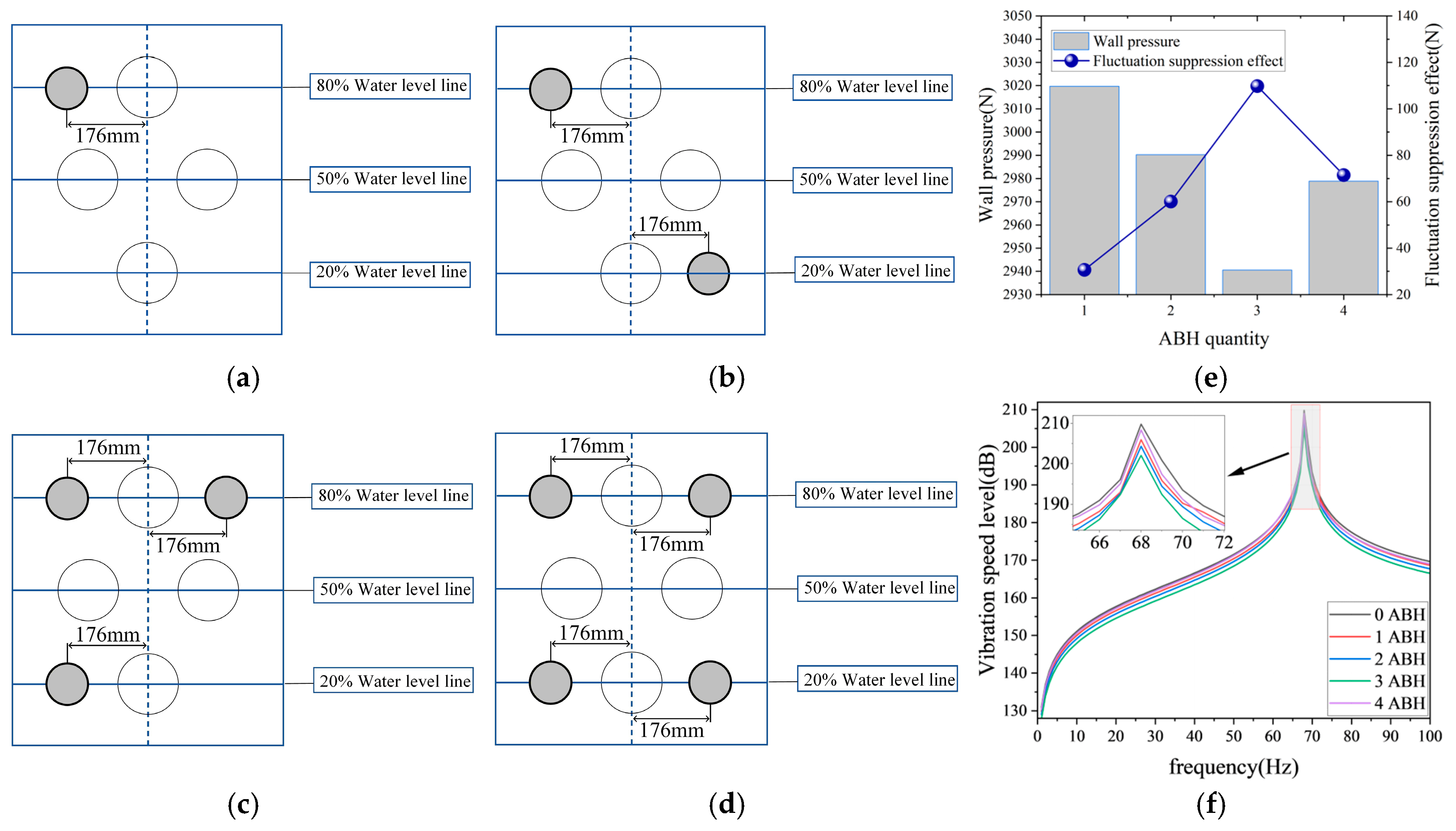

3.4.2. Analysis of the Influence of Acoustic Black Hole Quantity on Baffle Vibration and Sloshing Suppression Performance

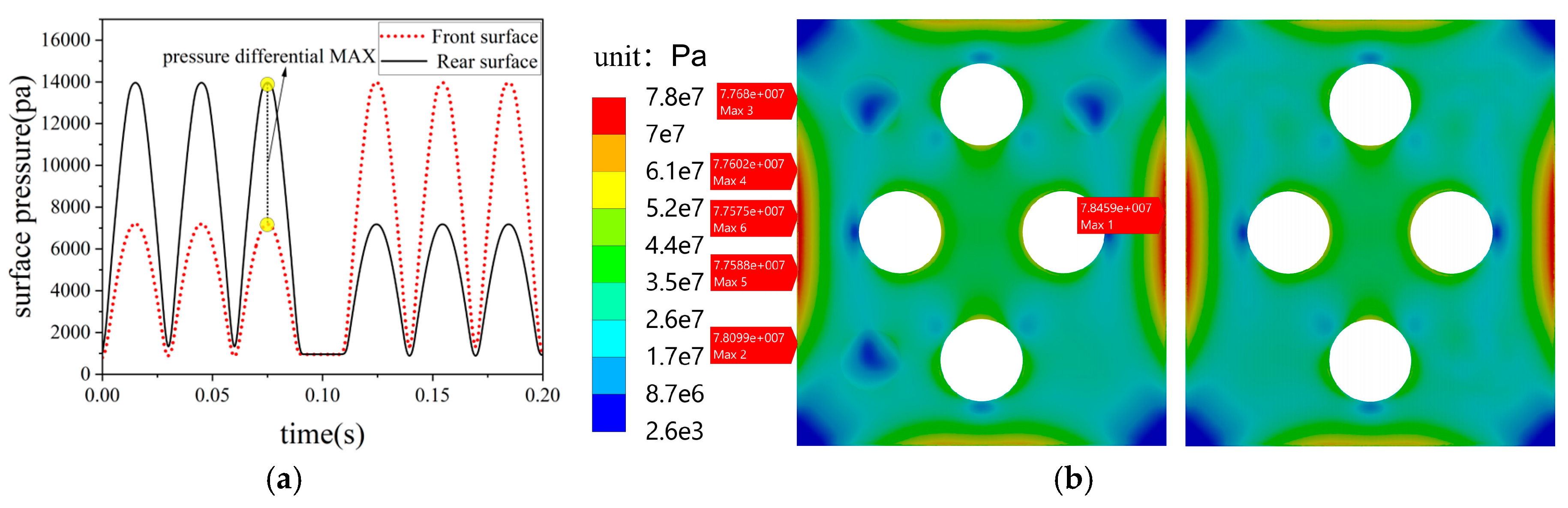

3.5. Strength Verification of the Acoustic Black Hole-Type Baffle

3.6. Performance Verification of the Acoustic Black Hole-Type Baffle

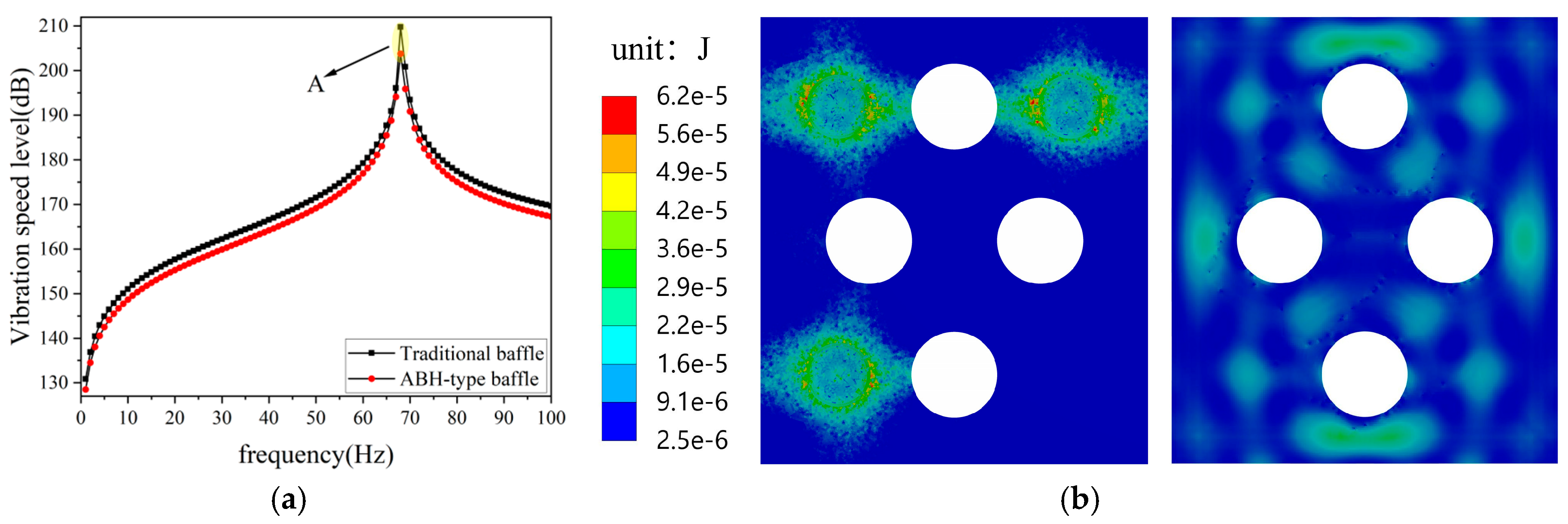

3.6.1. Vibration Suppression Effect

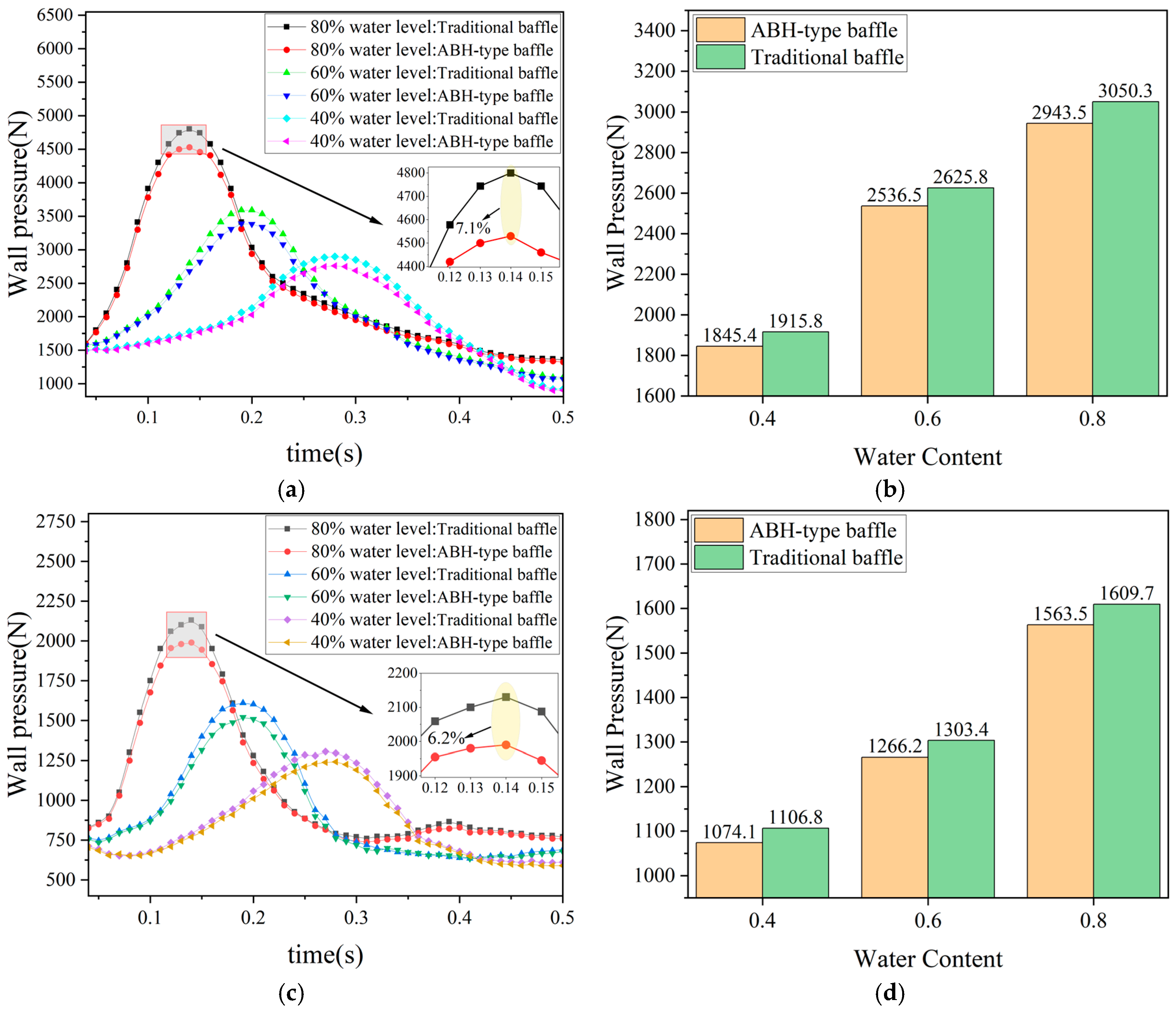

3.6.2. Sloshing Suppression Effect

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei Gu, Guoyuan Yang, Hongyan Xing, Yajing Shi & Tongyuan Liu. (2025). Temporal Convolutional Network with Attention Mechanisms for Strong Wind Early Warning in High-Speed Railway Systems. Sustainability, 17(14), 6339-6339. [CrossRef]

- Yan Zhigang, Wang Xueli, Qin Wei & Zhao Yucheng. (2020). Evaluation and Evolution Law of Sustainable Development Capacity in the Railway Transportation Industry. Journal of Railway Science and Engineering, 17(12), 3028-3035. [CrossRef]

- Ma Fujian, Li Yuan, Niu Yaohui, Wang Ziguang, Qi Jialiang & Zhang Shengfang. (2025). Fatigue Life Analysis of the Hoisted Water Tank Structure of High-Speed Trains. Journal of Lanzhou Jiaotong University, 44(02), 8-18.

- Zhao Sicong, Che Quanwei, Li Xinkang, Yang Jun & Niu Jiqiang. (2025). Fluid-Structure Interaction Characteristics and Baffle Opening Optimization Design of Water Tanks Under Braking Conditions of High-Speed Trains. Railway Vehicles, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Li Hongying. (2020). Vibration Cracking Analysis and Structural Optimization of the Auxiliary Water Tank Bracket of a Light Truck. Machine Design and Research, 36(05), 193-197. [CrossRef]

- Li Pengxin. (2020). Structural Optimization for Durability Cracking of the Upper Crossbeam of a Passenger Car Water Tank. Mechanical and Electrical Technology, (01), 85-89. [CrossRef]

- Fu Lei, Lu Changyu & Fang Hongyuan. (2021). Analysis of arc transition in welding structures of breakwaters based on numerical simulation. Welding & Joining, (02), 20-28, 62-63.

- Zhang Zhanbo & Li Shengqiang. (2018). Numerical Simulation Study on the Effect of Horizontal Perforated Baffles on Liquid Surface Sloshing in Cylindrical Water Tanks. Journal of Tsinghua University (Natural Science Edition), 58(10), 934-940. [CrossRef]

- Wang Hai, Zhang Feng, Qin Hongbin, Wang Xinfeng & He Wenqiang. (2025). Design and Optimization of T-Shaped Baffles for Tank Trucks Based on Improved NSGA-Ⅲ. Machine Design and Research, 41(05), 204-212. [CrossRef]

- Duan Linlin, Yang Zhirong, Zhang Yiming, Liu Cenfan & Liu Feng. (2023). Experimental Study on the Effect of Baffles on Liquid Sloshing in Tank Truck Models. Mechanics in Engineering, 45(05), 1109-1116.

- Tianze Lu & Deping Cao. (2025). SPH study of sloshing dynamics and energy dissipation characteristics in baffled tanks with varying baffle quantities. Ocean Engineering, 340(P2), 122378-122378. [CrossRef]

- Sina Amirsardari, Alireza Rouzbahani, Shayan Khosravi & Mohammad Ali Goudarzi. (2024). The effect of baffles on the re-distribution of dynamic forces in rectangular water tanks. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, 52(5): 994-1009.

- Tianze Lu & Deping Cao. (2025). Comparative study on wave response to vertical baffle orientation for resonant sloshing suppression in an upright cylindrical tank. Ocean Engineering, 341(P2), 122526-122526. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Ussama Hu, Changhong Dief, Tarek N & Kamra Mohamed M. (2025). Enhanced sloshing control using novel shaped baffle. PHYSICS OF FLUIDS, 37(8): 082123. [CrossRef]

- Feng Baofeng, Hu Mingyang, Zhou Shiyi, Yang Xiaoyan & Li Xiaochen. (2025). Experimental study on liquid sloshing in a rectangular tank with curved baffles. Ocean Engineering, 341: 122634. [CrossRef]

- Duan Zhongdi, Zhu Yifeng, Wang Chenbiao, Yuan Yuchao, Xue Hongxiang & Tang Wenyong. (2023). Numerical and theoretical prediction of the thermodynamic response in marine LNG fuel tanks under sloshing conditions. Energy, 270. [CrossRef]

- Fei Dong, Wenyu Zhang, Wei Hu & Xiaohui Cao. (2025). Numerical investigation on the effects of wave suppression baffles in vehicle-integrated water tanks. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering, 239(2-3), 760-774. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., & Wu, P. (2025). High-speed Railway, Green Innovation, and Industrial Structure Upgrading. Journal of Hunan University of Finance and Economics, 41(06), 73–84. [CrossRef]

- Hou Ning. (2021). Structural Analysis and Optimization Design of Under-Vehicle Hoisted Water Tanks Based on Fluid-Structure Interaction (Master’s Thesis, Dalian Jiaotong University). Master. [CrossRef]

- Adrien Pelat,François Gautier,Stephen C. Conlon & Fabio Semperlotti.(2020).The acoustic black hole: A review of theory and applications.Journal of Sound and Vibration,476(prepublish),115316-115316. [CrossRef]

- Wei Huang, Hongli Ji, Jinhao Qiu & Li Cheng. (2018). Analysis of ray trajectories of flexural waves propagating over generalized acoustic black hole indentations. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 417, 216-226. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Hongfei & Semperlotti Fabio. (2017). Two-dimensional structure-embedded acoustic lenses based on periodic acoustic black holes. Journal of Applied Physics, 122(6), 065104-065104. [CrossRef]

- Gao Nansha, Zhang Zhicheng, Wang Qian, Guo Xinyu, Chen Ke’an & Hou Hong. (2022). Research Progress and Applications of Acoustic Black Holes. Chinese Science Bulletin, 67(12), 1203-1213.

- Li Xi. (2018). Research on the Mechanical Properties of One-Dimensional Acoustic Black Hole Structures (Doctoral Thesis, Tianjin University). Doctor. [CrossRef]

- Bowyer Elizabeth P., Krylov Victor V. (2015). A review of experimental investigations into the acoustic black hole effect and its applications for reduction of flexural vibrations and structure-borne sound. INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress and Conference Proceedings, 250(4), 2594-2605.

- Cheer J, Hook K & Daley S. (2021). Active feedforward control of flexural waves in an Acoustic Black Hole terminated beam. Smart Materials and Structures, 30(3), 035003-. [CrossRef]

- Wen Huabing, Huang Huiwen, Shi Ziqiang & Guo Junhua. (2024). Acoustic-Vibration Characteristics Analysis of Stiffened Plates with Acoustic Black Holes. Journal of Ship Mechanics, 28(03), 442-449.

- Wu Jieyuan, Ma Botao, Yang Huafeng & Zhou Feng. (2024). Research on the Development Model and Influencing Factors of 400km/h High-Speed Railway. Railway Economics Research, (06), 42-46+64. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Shuai. (2024). Structural Optimization Design and Analysis of Integral Equipment Flanges for Pressure Vessels. Petroleum and Chemical Equipment, 27(02), 90-93.

- Li Yuan. (2025). Strength and Fatigue Life Analysis of the Hoisted Water Tank Structure of High-Speed Trains (Master’s Thesis, Dalian Jiaotong University). Master. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Xinlu. (2021). Structural Optimization Design of Train Water Tanks Based on Fluid-Structure Interaction Analysis (Master’s Thesis, Shijiazhuang Tiedao University). Master. [CrossRef]

- Deng Jie, Ma Jiafu, Chen Xu, Yang Yi, Gao Nansha & Liu Jing. (2024). Vibration damping by periodic additive acoustic black holes. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 574, 118235-. [CrossRef]

| Material Name | Density | Elastic Modulus MPa | Poisson’s Ratio | Yield Strength MPa |

| Q 345 | 7.85×10-6 | 2.1×105 | 0.3 | 345 |

| Element Size (mm) | Water Tank | Fluid domain | Pressure(N) | Error | ||

| Element | Node | Element | Node | |||

| 10 | 1220145 | 1955487 | 1684239 | 2422150 | 3372.4 | 1.25% |

| 9 | 1712347 | 2689935 | 2321451 | 3312861 | 3330.3 | 0.31% |

| 8 | 2218330 | 3471522 | 3194665 | 4536107 | 3320.1 | 0.11% |

| 7 | 3219432 | 4963539 | 4502818 | 6362990 | 3316.5 | - |

| Operating Condition | Baffle Type | Average Vibration Velocity Level(dB) | Vibration Suppression Effect(dB) | Average Wall Pressure(N) | Wave Suppression Effect(N) |

| Longitudinal Impact | ABH | 165.47 | 1.18 | 1877.4 | 38.4 |

| Without ABH | 166.65 | -- | 1915.8 | -- | |

| Transverse Impact | ABH | 161.20 | 1.01 | 1085.4 | 21.4 |

| Without ABH | 162.21 | -- | 1106.8 | -- |

| Baffle Type | Average Vibration Velocity Level(dB) | Vibration Suppression Effect(dB) |

| ABH | 165.51 | 3.17 |

| Without ABH | 168.68 | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.