1. Introduction

The osseous tissue and the bone marrow in particular, is a frequent site of cancer metastasis. Bone colonization is a negative prognostic factor that indicates the disease progression. Tumor cells that reside in the bone marrow are protected from chemo- and radiotherapies due to numerous epigenetic mechanisms [

1]. Cell-matrix interactions via integrin receptors as well as soluble compounds excreted by the stroma and infiltrating blood cells, all contribute to the formation of the survival niche for tumor cells ([

2] and refs. therein). This microenvironment promotes the reprogramming of transcriptional and metabolic profiles of tumor cells, thereby altering their responses to otherwise cytotoxic stimuli. Tissue damage by tumor-derived proteolytic enzymes leads to pathological fractures and the pain syndrome, further burdening the patient’s state.

Several aspects of tumor biology are relevant to the therapy of bone metastases. First, the resident tumor cells represent a population survived after the repetitive rounds of treatment. Therefore, the blocked apoptotic pathways provide survival advantage. Consequently, involvement of non-apoptotic modes of cell death emerges as a mechanistically substantiated approach. Next, selective elimination of tumor cells for the sake of sparing non-malignant counterparts is unlikely to be straightforward. In contrary, the therapeutic strategies should presume the eradication of the pro-oncogenic microenvironment, that is, the bone marrow purge. These considerations argue against single target therapies to combat resident tumor cells in the bone. Indeed, clinical efficacy of Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) against chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) cells in the bloodstream is higher than in the bone marrow [

3,

4,

5].

Instead, the necrosis-like cues deserve to be regarded as an alternative. The primary loss of the plasma membrane integrity is a major factor of induction of cell death. Among a variety of stimuli, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are the established metabolites capable of triggering the irreparable damage of the plasma membrane and the membrane organelles followed by cell death. Most importantly, the ROS-sensitive death pathways remain functional in cells that acquired drug resistance [

6,

7]. Apparently, ROS generation in antitumor therapy is a double-edge sword since the protection of normal tissue elements is problematic. Therefore, oxygen burst should be localized to the disease site. In this scenario the potency of ROS against tumor cells and their microenvironment is expected to be significant whereas the systemic toxicity is minimized.

Recently we reported a remarkable cytocidal activity of ROS generated upon the electrochemical reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(I). This effect was achievable by combining CuO nanoparticles or copper-organic complexes with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) or physiological reducing agents (i.e., cysteine or ascorbate) [

8]. Importantly, the Cu

2+-containing agent and the reducing amino acids were at virtually non-toxic concentrations whereas potentiation of the cytotoxic efficacy of the combination reached 2-3 orders of magnitude. One may hypothesize that the delivery of Cu

2+ to the bone and subsequent administration of the reducing agent would locally trigger lethal ROS burst.

In the present study we approached this assumption by the design and synthesis of Cu(II) complexes with zoledronic acid (ZA), an FDA-approved bisphosphonate [

9,

10,

11]. This drug demonstrated a good clinical efficacy in preventing metastatic bone resorption in patients with breast, renal and prostate cancer, as well as myeloma [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Most importantly, the new water-soluble formulations of

CuZA complexes in combinations with cysteine readily killed cultured CML cells otherwise protected from the Bcr-Abl inhibitor in the medium conditioned by bone marrow-derived fibroblasts.

2. Results

2.1. Chemistry

2.1.1. Synthesis of CuZA Complexes

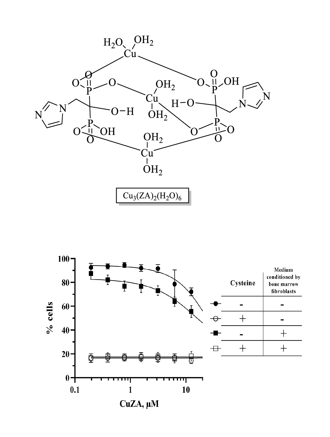

The initial

CuZA complex was prepared using a previously described method starting from copper (II) sulfate [

16] although the structures differed. This was confirmed by electrochemical data (see below), according to which the new complex contained three identical copper atoms, in contrast to the X-ray diffraction data [

16]. The use of other copper salts such as chloride or perchlorate, resulted in the formation of precipitates similar in composition to the complex obtained from copper sulfate. Thus, the composition of new

CuZA complexes was independent of the metal cation (counter-ion) in the salt. In fact, we obtained the same

CuZA complex using three different copper salts (

Figure 1). For the rest of the study, the resulting compound is referred to as

CuZA.

Note that the perchlorate, sulfate or chloride salts yielded the same CuZA complex.

2.1.2. Reducing Agents

Previously we have demonstrated that NAC was capable of reducing copper(II) in the context of oxide or metal-organic compounds as determined by electrochemical methods and cytotoxicity tests [

8,

17]. In the present study, we turned to cysteine as a physiological reducing agent in cell culture experiments, whereas its derivative NAC was used in electrochemistry measurements for compatibility with organic solvents.

2.1.3. Electrochemistry

We aimed to use cyclic voltammetry (CV) and rotating disk electrode (RDE) voltammetry techniques in DMSO with 0.1 M Bu

4NClO

4 as a supporting electrolyte. CV determines the reduction potentials while RDE allows for estimation of the oxidation state of copper [

18] and E

1/2 of redox transition. Both free ZA and

CuZA complex were extremely poorly soluble in DMSO, as well as in other tested solvents suitable for electrochemical studies such as CH

3CN or dimethyl formamide. Therefore, CV measurements for these compounds were impossible.

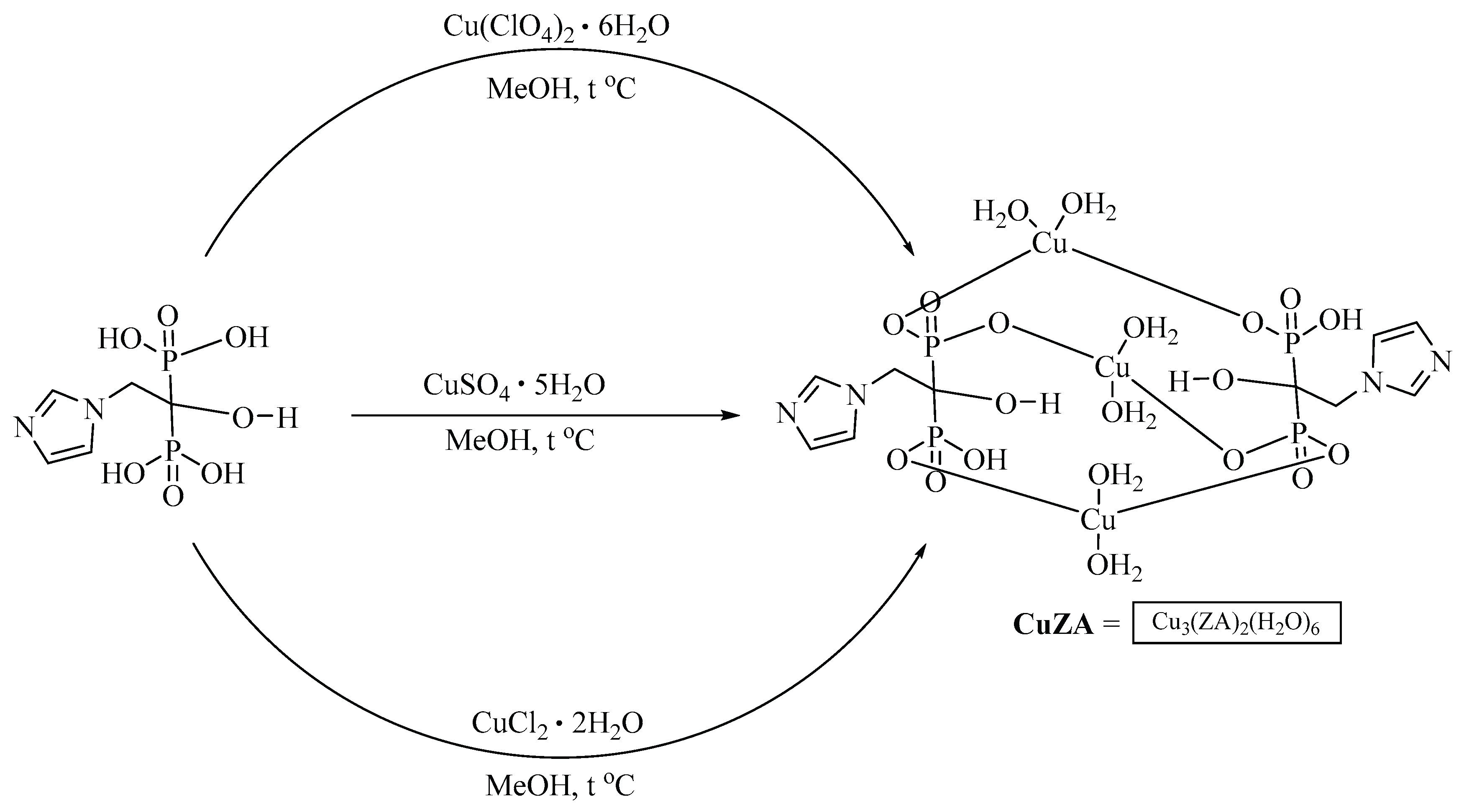

However, a more sensitive RDE voltammetry allowed to determine the potential of Cu

2+ → Cu

1+ redox transition in the complex. NAC was added to

CuZA solution in an amount sufficient to reduce all copper cations in the complex (3 equiv., one per each Cu cation). Although the initial complex was poorly soluble in DMSO, its solubility increased significantly upon the addition of NAC: note an increased current on the RDE curve (

Figure 2A; compare black and colored lines). According to RDE data, Cu

2+ rapidly disappeared, transforming the complex into a Cu

1+-containing form. This is demonstrated by gradual change of the current from cathodic (corresponds to reduction) to anodic (corresponds to oxidation) during Cu

1+ ←→ Cu

2+ redox transition. Eight min after the addition of NAC, the reduction was complete and the system stabilized; only Cu

1+ cations were present in the solution. Single Cu

2+ → Cu

1+ transition in RDE confirmed the identical coordination environment of all three metal cations in the complex (no interaction between metal cations); therefore, their reduction occurred at the same potential.

For the resulting Cu

1+ZA complex, due to its higher solubility compared to the starting

CuZA, a CV curve can be recorded (

Figure 2B). The redox potential of Cu

+1 ←→ Cu

2+ transition was ~+0.38 V. If a 10-fold excess of NAC was added to

CuZA solution instead of 3 equiv., the Cu

2+ → Cu

1+ reduction occurred instantly. Within 1 min after admixing, only Cu

1+ remained in the solution according to RDE. Thus, the electrochemical data confirmed rapid Cu

2+ → Cu

1+ transition in

CuZA complex in the presence of the reducing agent.

2.1.4. Water-Soluble Formulations

The

CuZA complex was practically insoluble in water, soluble in chloroform, very slightly soluble in 95% ethanol, acetone and benzene, and readily soluble in DMSO and dimethyl formamide. We applied an approach [

19,

20] based on varying pH to obtain a water-soluble salt and its subsequent stabilization with the co-solvent, polyvinylpyrrolidone (Kollidon 17PF). The water-soluble, biocompatible and storage-stable compositions were characterized by mass ratio of

CuZA complex /0.1 N NaOH/95% ethanol/Kollidon 17PF: 1.2/1/44/22. The sequence of steps and conditions of dissolution were important for the formation of stable solutions of the required concentration. Of note,

CuZA and Kollidon 17PF must first be co-dissolved in 95% ethanol with stirring at 400 rpm, 60 °C. Then the resulting concentrate was diluted with 0.1N NaOH. For cell culture studies, we prepared 10 mM stock solution of

CuZA (aqueous formulation).

2.2. Biological Testing

2.2.1. Reductive Cytotoxicity of CuZA Complexes

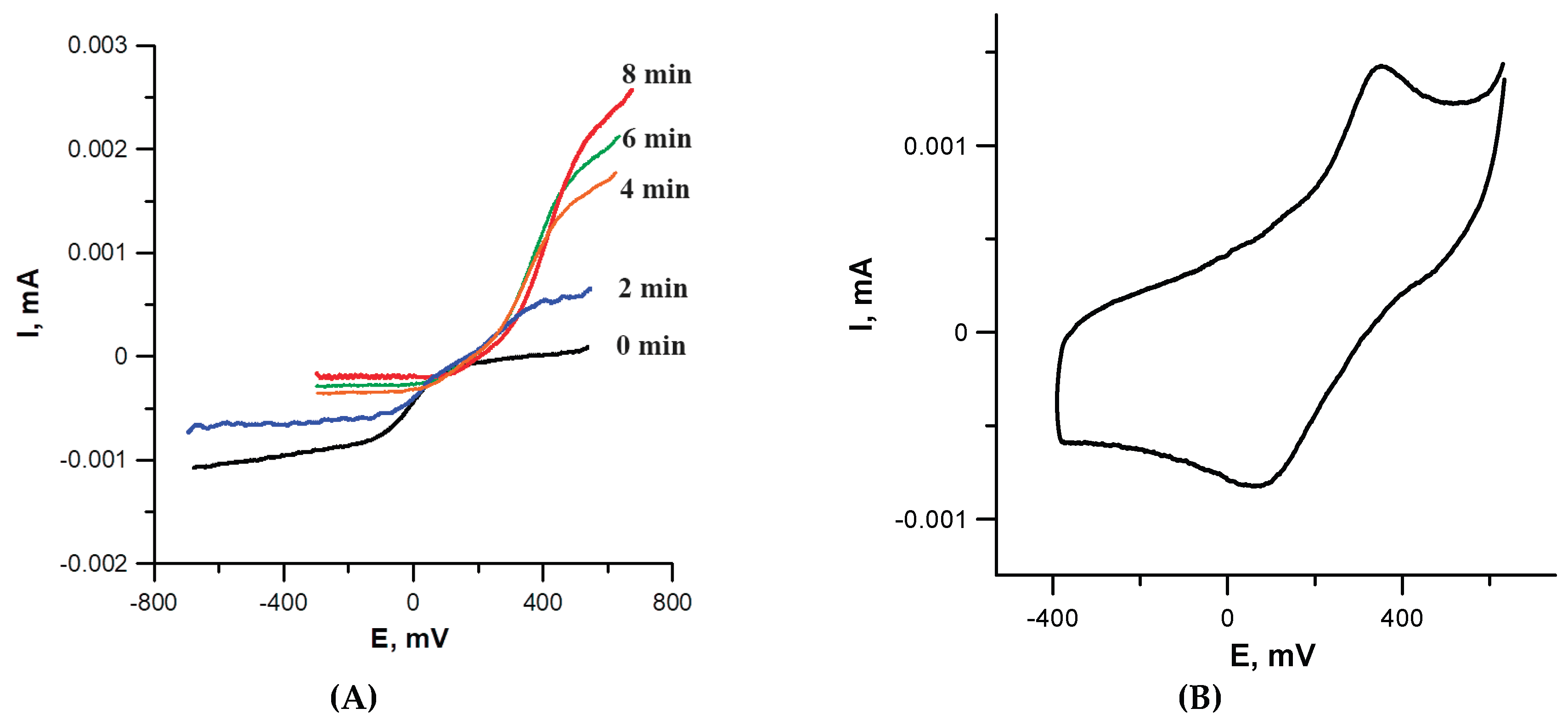

We tested a broad range of

CuZA concentrations to determine the doses (0.1-10 µM) that evoked little-to-no cytotoxicity in HS5 bone marrow-derived fibroblasts for at least 48 h of exposure. Cysteine alone was non-toxic at 0.5-1 mM. These results were similar to those determined by us with Cu(II)-organic compounds and NAC for other cell lines [

8,

17]. In striking contrast, the combinations of as low as 0.2 µM

CuZA and 0.5 mM cysteine caused a significant cytotoxicity in HS5 fibroblasts: the percentages of MTT conversion, a measure of cell viability, were at the assay’s background (

Figure 3A). In contrast, the metal-free ZA alone (up 10 µM) was inert; the addition of 0.5 mM cysteine was without the effect (

Figure 3B), indicating that cell death is mechanistically linked to Cu

2+ reduction. The initial signs of cell death were detectable within 6 h of exposure to the combinations, similarly to CuO or Cu(II) organic compounds in combination with NAC [

8]. Most importantly, cell death by the combination of

CuZA and cysteine was achieved with concentrations that evoked no discernible cytotoxicity if each component was administered alone.

2.2.2. Intracellular vs. Extracellular Distribution of CuZA

We were interested whether

CuZA complexes accumulate in cultured cells. This parameter was determined based on measurements of inorganic copper in cell lysates (intracellular content) and in culture medium (extracellular content) after incubation with the non-toxic concentration of

CuZA.

Table 1 shows time dependent uptake of

CuZA by cells of different tissue origin. Intracellular copper content increased over time, with maximum registered by 24 h. Interestingly, cells incorporated only a minor portion of

CuZA: the metal was detected predominantly in the extracellular medium. These ratios were consistent for adherent (HS5) as well as for suspension (K562) cells (

Table 1) indicating a limited accumulation of

CuZA complexes inside the cells.

Cells were treated with 5 µM CuZA for indicated time intervals. Media were collected, cell monolayers were washed with saline and lysed in dH2O. Samples were processed for measurements of copper content (see Materials and Methods). Values are mean+confidence interval (n=3 replicates, each sample measured in triplicate). *P<0.05 compared with the respective Medium group.

2.2.3. Cytotoxic Potency of CuZA-Cysteine Combination

Keeping in mind relatively low intracellular accumulation of CuZA, one may argue that reduction of extracellular, not as much intracellular, copper confers ROS-mediated cytotoxicity. To test this hypothesis, we treated HS5 cells with 5 µM CuZA for 24 h followed by drug withdrawal and the addition of fresh medium supplemented with 0.5 mM cysteine. In this setting, the cells were pre-loaded with CuZA whereas the external copper content was negligible. Nevertheless, the addition of cysteine for 24 h yielded similarly high percentage of PI-positive cells (78+11%) as if extracellular CuZA was present (82+10%; mean+standard errors, n=3 measurements). Therefore, even limited amounts of intracellular CuZA were sufficient for triggering the reductive cytotoxicity. These observations strongly suggested that ROS generation upon electrochemical Cu2+-to-Cu1+ transition is a powerful mechanism of cell elimination.

We took advantage of this mechanism for induction of death in cells with altered response to specific chemotherapeutics. Indeed, CML cells that were initially sensitive to Bcr-Abl-targeting TKI can survive in the course of continuous treatment leading to a relapse [

21,

22]. In particular, the viability of CML cells that colonized the bone marrow can be promoted by stromal elements that form a survival niche for tumor cells. Therefore, the pro-apoptotic stimuli initiated by targeting Bcr-Abl with TKI are countered by signaling engaged by integrin-mediated adhesion of CML cells to extracellular matrix as well as by soluble factors such as cytokines [

23,

24,

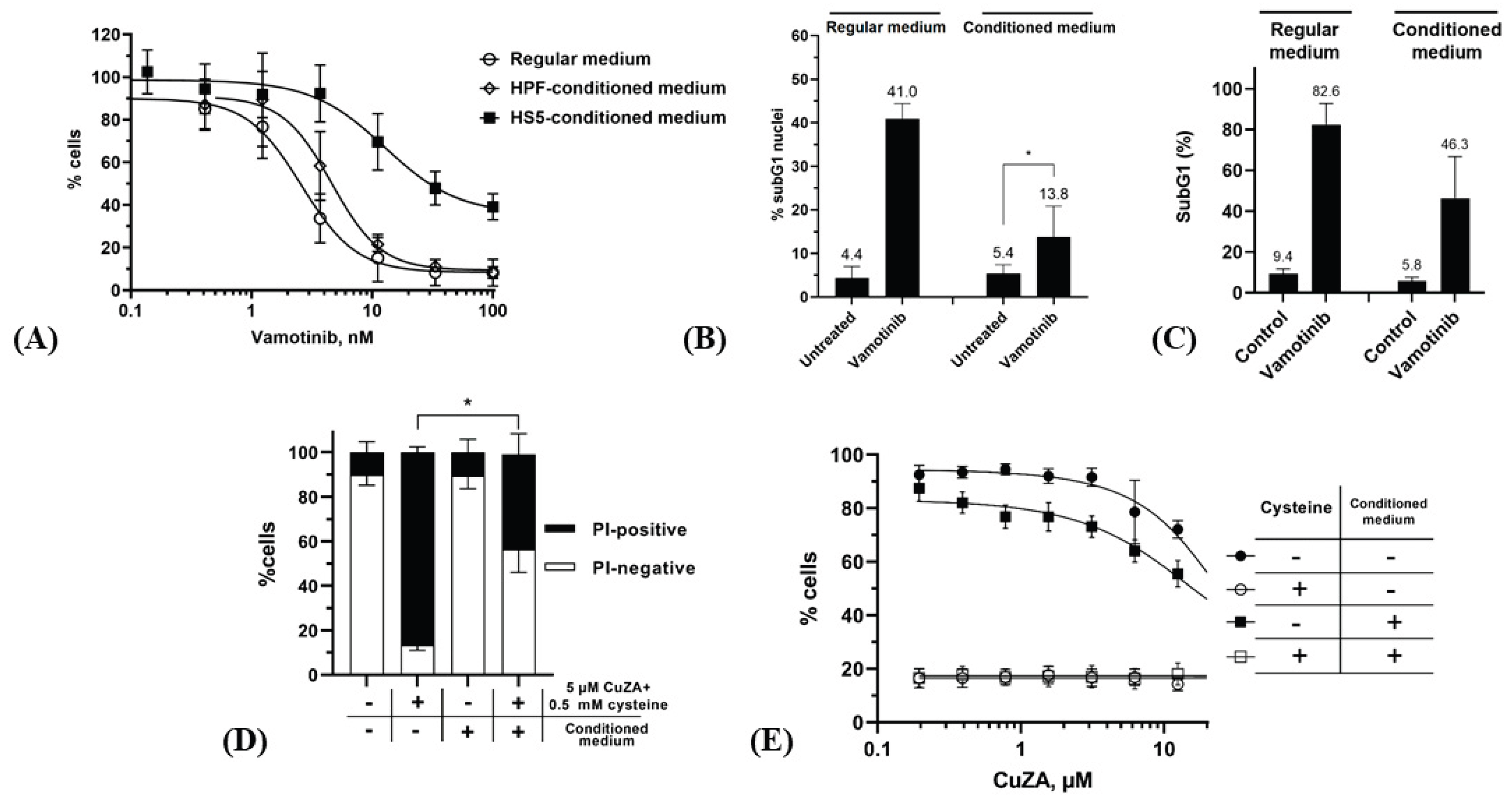

25]. We tested whether microenvironmental factors produced by HS5 bone marrow-derived fibroblasts can attenuate CML cell death in response to Bcr-Abl inhibition. The K562 CML cells cultured in the presence of HS5 fibroblasts or bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells were partially protected from the prototypic Bcr-Abl antagonist, imatinib mesylate [

26,

27,

28]. Likewise, we observed a pro-survival effect of the bone marrow microenvironment on K562 cells treated with vamotinib (PF-114), a 3d generation TKI [

29,

30,

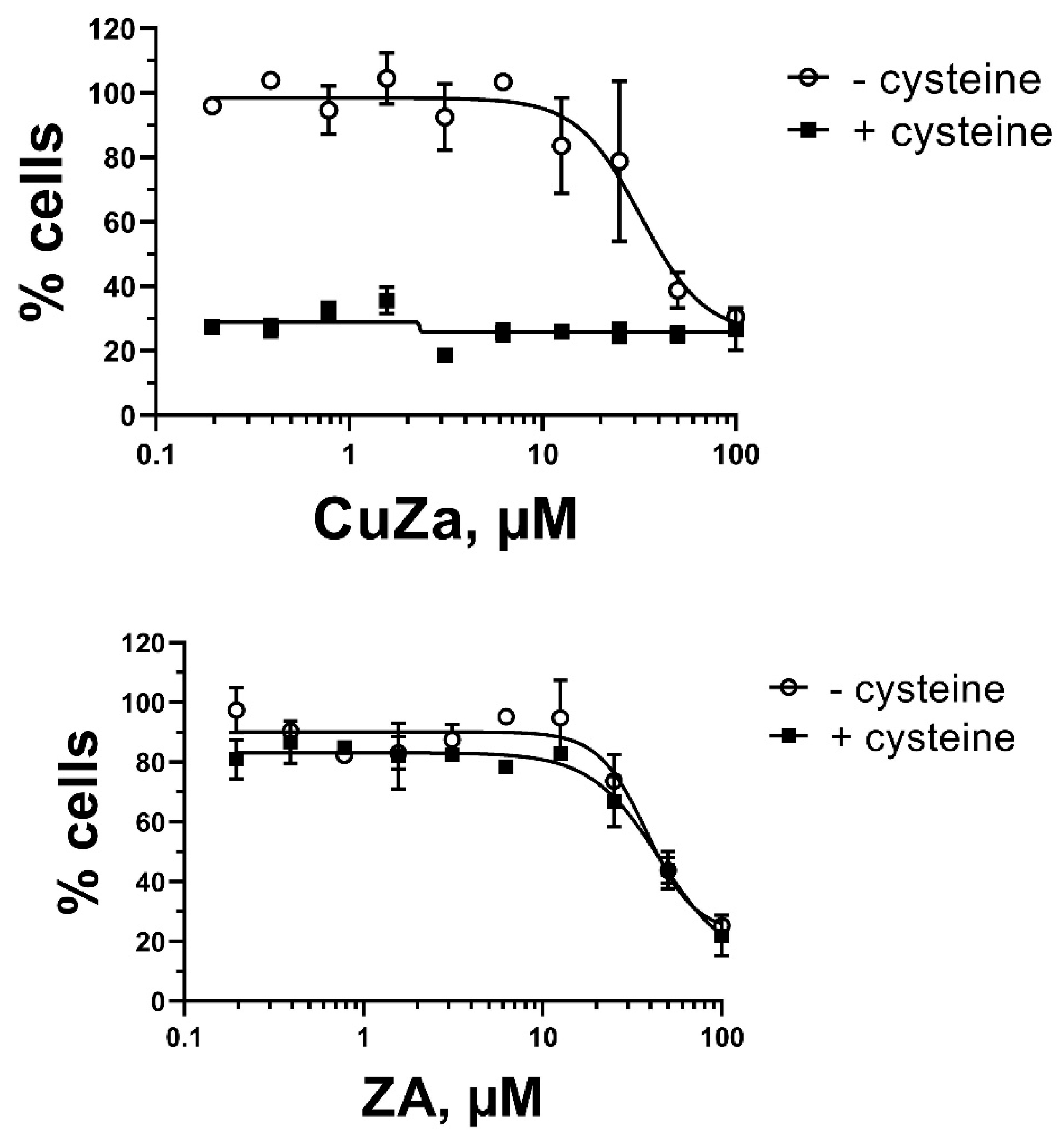

31]. In the regular medium, IC

50 of this compound was 2.4±1.0 nM after 72 h. However, this parameter could not be accurately calculated from the survival curve if cells were treated in HS5-conditioned medium: ~40% of cell population remained viable even at 100 nM vamotinib (

Figure 4A). However, the medium conditioned by bone marrow-unrelated fibroblasts (HPF cell line) had no protective effect on the response of K562 cells to vamotinib, supporting the role of the organ-specific microenvironment. Lower percentages of subG1 events in K562 cells treated with vamotinib for 72 h confirmed the attenuated cytotoxicity in the conditioned medium (

Figure 4B). Importantly, the protective effect of the conditioned medium was prolonged: by 12 days in the regular medium >80% cells displayed the fraction of fragmented DNA (

Figure 4C) whereas this parameter was smaller in the conditioned medium. These data indicated that conditioning by HS5 fibroblasts conferred a long-term survival to vamotinib-treated K562 CML cells, substantiating a serious limitation of the efficacy of targeted therapy in the bone marrow microenvironment.

In striking contrast, no protection by the conditioned medium was detectable for combinations of submicromolar concentrations of

CuZA and 0.5 mM cysteine. By 48 h ~40% cells were PI-positive (

Figure 4D); however, the resazurin tests showed a dramatically decreased viability of total population of K562 cells (signals dropped down to the background levels of the assays both in the regular and conditioned media;

Figure 4E) (see [

32] for the approaches to determine the statistical differences between ‘cysteine’ vs. ‘no cysteine’ groups). Thus, the combination of

CuZA and the physiological reducing agent (both at non-toxic concentrations) potently killed CML cells in the situation where the response to Bcr-Abl inactivation was altered.

3. Discussion

Electrochemical reduction of Cu

2+ to Cu

+ in different chemical contexts is an efficient approach to kill cells. The multiplicity of death pathways triggered by ROS generated in this reaction allows to circumvent chemotherapeutic drug resistance. Most importantly, the early loss of the plasma membrane integrity, a key mechanism of cell vulnerability, remains operational in pleiotropically resistant cells. However, development of practical applications of Cu

2+→Cu

+ redox transition mechanism in cancer treatment presumes a number of conditions. First, the organic milieu should be ‘permissive’ for the copper (II) cation to be available for electrochemical reduction. In other words, the reduction potential in the Cu-organic complex must be lower than the oxidation potential of the reducing agent [

17]. Second, to minimize general toxicity, ROS generation should be localized to the site(s) of tumor cell accumulation. This prerequisite highlights the importance of organ delivery of Cu(II) cations using specific chemical scaffolds as vectors. However, biocompatibility of metal-organic complexes can be hampered by limited solubility in aqueous media. Furthermore, intracellular accumulation of copper-organic complexes should ensure an amount of copper sufficent for ROS burst upon metal reduction. Moreover, on their route to the target organ, Cu(II) cations can be redistributed from the initial complex to other carriers such as blood plasma proteins. Or else a portion of exogenous Cu(II) cations can undergo redox transition in vivo by physiological reducing compounds, e.g., glutathione. Together, these factors can interfere with the delivery of copper to the target organ.

In the present study we report the initial evaluation of CuZA complexes designed as a tentative tool for metal delivery to the bone. Bisphosphonates (ZA in particular) have demonstrated a good clinical efficacy in prevention of bone resorption in metastatic lesions as well in non-malignant osteopathy. Thus, it is plausible to hypothesize that ZA could serve for copper transport to the bone tissue. In this scenario, CuZA emerges as a dual activity agent expected to act as a bone protector (due to the bisphosphonate moiety) and a depot of copper; the latter would be reduced not before the sufficient quantities of cysteine or ascorbate are added.

The one-step synthesis of

CuZA from three salts of divalent copper (i.e., perchlorate, sulfate and choride) yielded identical complexes in which three Cu

2+ cations coordinated two ZA molecules. In electrochemical experiments, we replicated the effect of Cu

2+→Cu

+ redox transition in

CuZA in the presence of NAC previoulsy demonstrated for CuO and many (but not any) Cu(II)-containing compounds contingent on the organic scaffold [

17]. Therefore, the bisphosphonate milieu did not limit the reductive potential of Cu

2+ cations, making

CuZA promising for biological investigation. However,

CuZA was virtually insoluble in polar and non-polar media. Nevertheless, we obtained water-soluble formulations by varying the ratios of aqueous solutions of ethanol and NaOH followed by stabilization with Kollidon 17PF. These preparations were tested for the ability to trigger oxidative damage in cultured cells.

Along with these findings, we observed that intracellular accumulation of water-soluble CuZA was relatively low as determined by atomic force spectrometry-assisted measurements of copper content. The majority of copper remained in the extracellular medium. Still, the quantities of intracellular copper after removal of the medium were enough for reductive cytotoxicity. These results further proved the anticancer potential of this approach even if limited amouts of copper are delivered to the tumor site.

The bone marrow microenvironment represents a protective niche for resident tumor cells [

33,

34,

35]. A complex network of pro-survival signaling includes interactions of tumor cells with extracellular matrix and non-malignant stromal elements. These direct contacts, along with distant regulatory mechanisms mediated by soluble factors (chemokines), provide an opportunity for tumor cells to escape the cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutics. Bcr-Abl inhibitors have been shown to be less efficacious against CML cells in the bone marrow than in the peripheral blood [

3,

4,

5]. The protective effect is not limited to CML: the acute myeloid leukemia cells are rescued from chemotherapeutic drugs in the hematopoietic niche [

36]. Whatever the mechanism of survival in the bone microenvironment, the resident leukemia cells exhibit a pleiotropic drug resistance acquired in the course of repetitive rounds of treatment. Targeted therapy is no longer efficient; new approaches are needed to cope with the disease progression. One critical prerequisite is the induction of non-apoptotic death pathways.

Our model of altered response of CML cells to the Bcr-Abl antagonist presumed the use of the culture medium conditioned by bone marrow-derived fibroblasts. This medium partially rescued K562 cells from vamotinib, a 3d generation Bcr-Abl inhibitor that recently entered clinical trials [

31]. Molecular mechanisms that confer an epigenetic resistance of K562 cells to Bcr-Abl inhibition in the conditioned medium are under investigation by our group. Importantly, in the HS5-conditioned medium, as well as in the regular medium, the combinations of

CuZA and cysteine (each component alone at non-toxic concentrations) were cytocidal. These results were in line with the reported exceptional potency of individual copper-containing compounds upon electrochemical metal reduction [

8].

This study provides evidence in favor of Cu(II) reductive cytotoxicity as an alternative to kill cells that survived certain therapeutic stimuli. A major prerequisite for an approach aimed at circumventing pleiotropic resistance is the ability to trigger multiple death mechanisms [

37]. Most importantly, cell death upon Cu

2+-to-Cu

+ redox transition involves the damage of the plasma membrane and membrane organells [8, this study]. The necrotic pathway remains functional in cells otherwise irresponsive to a variety of apoptotic stimuli. Therefore, necrosis can emerge as a method of choice in advanced disease. Moreover, the selective targeting of CML cells in the organ can be insufficient due to pro-oncogenic influence of the microenvironment. Strategies of sparing non-malignant counterparts within the tumor site are likely to be palliative; we argue in favor of an indiscriminate elimination of tumor cells and the surrounding milieu as a salvation therapy in late stages of the disease. Definitely, the oxidative ablation of the bone marrow demands an exceptionally thorough patient care to prevent unfavorable systemic complications, primarily infection.

4. Study Limitation

Advantages of the reported approach are the readiness of the thrifty synthesis, the stability of water-soluble CuZA formulations, and their cytocidal potency in combinations with cysteine in electrochemical assays and in cell culture. Although the principle is proved, the efficacy of CuZA-cysteine combinations in vivo remains to be investigated in detail. Among the critical issues is the ability of CuZA complexes to keep the metal protected from the attack by reducing agents in the serum and tissues, aiming at the delivery of maximal amounts of Cu2+ to the organ. Next, the development of the drug candidate presumes the formation of the bone depot via maximum ZA-assisted Cu2+ delivery. ZA is expected to ensure the prolonged retainment of the metal in the bone; however, there is a possibility for Cu2+ exchange between CuZA and small molecular weight compounds and/or proteins in the site. Still, one may anticipate that such a re-complexation, if it takes place, should not attenuate the cytocidal potency of the local ROS burst generated upon Cu2+-to-Cu1+ transition inside the cells as well as in the extracellular milieu.

5. Conclusions

Exploring the efficacy of the oxygen burst upon reduction of copper (II) in the context of organic compounds, we performed a one-step synthesis of complexes containing two molecules of the bone-affine drug ZA coordinated by three Cu2+ cations (CuZA). Electrochemical techniques confirmed Cu2+→Cu1+ transition in the presence of the reducing agent. Poor water solubility of the initial CuZA preparations was overcome by obtaining stable aqueous formulations suitable for cell culture. These formulations together with cysteine (each component at non-toxic concentrations) triggered death in K562 CML cells in regular medium. Importantly, these combinations were similarly cytocidal against K562 cells in the medium conditioned by HS5 bone marrow-derived fibroblasts where the efficacy of the 3d generation Bcr-Abl inhibitor vamotinib was limited. Thus, the new CuZA complexes serve as a tool for preclinical investigation of dual potency, bone-directed antitumor drug candidates.

6. Materials and Methods

6.1. General

All chemicals purchased from Merck, Lancaster and ABCR were reagent grade and used without purification. Melting points were determined using an OptiMelt MPA100 – Automated melting point system, 1 °C/min, 0.1 °C resolution. Infrared spectra were recorded on a Thermo Nicolet iS5 FTIR, number of scans 32, resolution 4 cm−1, sampling ATR. Elemental analysis of CHNS/O was performed using a Perkin Elmer Model 2400 Series II (Perkin Elmer, USA). Electronic spectra in the UV and visible regions were recorded on a Hitachi U-2900 instrument with an operating wavelength range of 190-1100 nm in a quartz cuvette manufactured by Agilent Technologies with an optical path of 10 mm.

6.2. Synthesis

Coordination compounds [Cu3(ZL)2(H2O)6]*xH2O were prepared by sedimentation using ZA and copper salts (CuCl2*2H2O, CuSO4*5H2O, Cu(ClO4)2*6H2O).

1) ZA (82 mg; 0.3 mmol) was dissolved in 10 ml methanol and heated up to 64°С with constant stirring, then a solution of CuCl2*2H2O (102 mg; 0.6 mmol) in 5 ml methanol was added and the mixture was stirred fo 24 h at 64°С. The resulting blue-green precipitate was filtered off, washed with ethanol, water and air-dried. Yield 67%. The composition of the complex was determined by elemental analysis: Cu3(ZL)2(H2O)6. Elemental analysis: calcd for C10H26Cu3N4O20P4 * 5H2O: C% 14.03; H% 4.17; N% 5.95. Found: С% 13.70, Н% 4.09, N% 5.88. IR spectra (KBr, cm-1): 3444, 3167, 1627, 1400, 1279, 1151, 1077, 1031, 990, 965, 842, 638, 603.

2) ZA (82 mg; 0.3 mmol) was dissolved in 10 ml methanol and heated up to 64°С with constant stirring, then a solution of CuSO4*5H2O (154 mg; 0.6 mmol) in 5 ml methanol was added and the mixture was stirred fo 24 h at 64°С. The resulting blue-green precipitate was filtered off, washed with ethanol, water and air-dried. Yield 73%. The composition of the complex was determined by elemental analysis: Cu3(ZL)2(H2O)6. Elemental analysis: calcd for C10H26Cu3N4O20P4 * 2H2O: C% 13.76; H% 3.46; N% 6.42. Found: С% 13.62, Н% 3.19, N% 6.28. IR spectra (KBr, cm-1): 3444, 3167, 1627, 1400, 1279, 1151, 1077, 1031, 990, 965, 842, 638, 603.

3) ZA (82 mg; 0.3 mmol) was dissolved in 10 ml methanol and heated up to 64°С with constant stirring, then a solution of Cu(ClO4)2*6H2O (222 mg, 0.6 mmol) in 5 ml methanol was added and the mixture was stirred fo 24 h at 64°С. The resulting blue-green precipitate was filtered off, washed with ethanol, water and air-dried. Yield 58%. The composition of the complex was determined by elemental analysis: Cu3(ZL)2(H2O)6. Elemental analysis: calcd for C10H26Cu3N4O20P4 * H2O: C% 14.05; H% 3.30; N% 6.55. Found: С% 13.99, Н% 3.02, N% 6.41. IR spectra (KBr, cm-1): 3444, 3167, 1627, 1400, 1279, 1151, 1077, 1031, 990, 965, 842, 638, 603.

6.3. Electrochemistry

An IPC Pro M potentiostat was used for electrochemical studies. The working electrode was a glassy carbon disk (d = 2 mm), the reference electrode was Ag/AgCl/KCl (sat.). The auxiliary electrode was a platinum plate, and the supporting electrolyte was 0.1 M Bu4NClO4 solution in DMSO. Potential scan rates were 100 mV/s and 20 mV/s-1 in CV and RDE methods, respectively. Measurements were carried out in a dry argon atmosphere; samples were dissolved in a de-aerated solvent.

6.4. Preparation of Water-Soluble Formulations

The required amounts of powdered CuZA complex and Kollidon 17PF (BASF, Germany) were placed in a glass beaker and dissolved in the respective volume of 95% ethanol with stirring (400 rpm) and heating (60 °C) on a magnetic device for 20 min. To a clear blue solution, 0.1N NaOH was added dropwise with stirring at 200 rpm to produce a light blue solution. The latter was filtered through 0.45 µM filter and stored at 4 °C for at least 6 mo. without opacity. Preparations were used as 10 mM stock solutions in the experiments.

6.5. Measurements of Copper in Cell Lysates and Extracellular Medium

The copper content was a measure of intracellular and extracellular CuZA accumulation. Cells were treated with 5 µM CuZA in the culture medium for 3-24 h. The medium containing extracellular CuZA was collected. Monolayers were washed with saline and lysed in dH20. Lysates were centrifuged (10,000 x g 3 min) to pellet the water-insoluble material. Supernatants containing cell-associated CuZA were processed for quantitative measurement of copper in the extracellular medium and in lysate supernatants on a quadrupole inductively coupled mass-spectrometer (ICP-MS) PlasmaQuant MS Elit (Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany) after 125-145-fold dilution in 3% (v/v) HNO3. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. Data were acquired and processed with the ASpect MS software package (version 4.3, Analytik Jena). Indium (1 µg/L) was an internal standard. 115In, 63Cu and 65Cu isotopes were determined using a collision cell (gaseous He, 40 ml/min) and without collision cell. For calibration, the multi-element Standard E solution (ICP-MS-E-100, High-Purity Standards) was diluted to reach final concentrations 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10 and 20 µg/L.

6.6. Cell Culture and Cytotoxicity Assays

Human HS5 bone marrow fibroblasts, K562 CML cells (American Type Culture Collection; Manassas, VA) and HPF foreskin fibroblasts (gift of Dr. S.M.; Dashinimaev, Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology, Moscow, Russia) were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone; Logan, UT) and 50 μg/ml gentamicin at 37 °C, 5% CO

2 in a humidified atmosphere. Water-soluble formulations of

CuZA were serially diluted in the culture medium from 10 mM stock solution immediately before the experiments. Metal-free ZA was dissolved in DMSO (10 mM).

L-cysteine was dissolved in culture medium as 50 mM stock solution, then pH was adjusted to 7.2-7.4 with 1 M NaOH. Viability of HS5 cells treated with

CuZA alone or in combination with cysteine was determined in MTT tests [

8]. Vamotinib (gift of Dr. G. Chilov; Valenta Pharm, Russia) was dissolved in DMSO as 10 mM stock solution. The K562 cells were exposed to the increasing concentrations of vamotinib (freshly reconstituted from the stock solution in the culture medium) for 72 h. In parallel, cells were treated with vamotinib for 72 h in the medium pre-conditioned by HS5 or HPF (bone marrow-unrelated cell type control) fibroblasts for 48 h. To assess the prolonged survival, K562 cells were treated with vamotinib in the regular or HS5-conditioned medium for 72 h, then resuspended in respective drug-free media and further incubated for another 9 days, changing the media every 3 days (total 12 days). For drug combination experiments, K562 cells were treated with 5 µM

CuZA and 0.5 mM cysteine in the regular or HS5-conditioned medium for 48 h. Cell viability was assessed in resazurin tests [

38] as well as by flow cytometry. Sample processing and evaluation of subG1 events (in lysed cells) and PI-positive whole cells (no lysis) have been described by us [

8]. Measurements were performed on a CytoFlex flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA). Twenty thousand fluorescent events were collected per sample (n=3 biological replicates, each measured in duplicate). Data was analyzed using CytExpert software (Beckman Coulter).

6.7. Statistics

One-way or two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) followed by Sidak’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons were used (GraphPad Prism 9; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The P value < 0.05 was taken as evidence of statistical significance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K.B. and A.S.; methodology, E.S.B., AM.S., K.C.; validation, E.S.B., A.M.S., K.C., E.K.B., A.S.; investigation, E.S.B., A.M.S., K.C., A.P., M.A., A.M., Y.M., A.L., A.D., S.T.; data curation, E.K.B. and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, E.K.B. and A.S.; visualization, E.S.B., A.M.S., K.C.; supervision, E.K.B. and A.S.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Non-Commercial Foundation for Support of Oncology Research (RakFond, agreement 1/2024 as of July 30, 2024) and the Russian Science Foundation (grant No. 25-75-10075).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The work was carried out within the framework of the State assignment of the Department of Organic Chemistry, Faculty of Chemistry, Moscow State University “Synthesis and study of physical, chemical and biological properties of organic and organoelement compounds” (CITIS No. AAAA-A21-121012290046-4). The authors are grateful to G. Chilov for providing vamotinib.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Sun, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, H.; Huo, L.; Zhang, S.; Huang, S.; Gao, B.; Wu, J.; Chen, Z. Liver cancer bone metastasis: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic insights. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2026, 26, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelding, K.A.; Barry, D.L.; Lincz, L.F. Modeling the bone marrow microenvironment to better understand the pathogenesis, progression, and treatment of hematological cancers. Cancers 2025, 17, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Rutella, S.; Almeida, A.M.; De Las Rivas, J.; Trougakos, I.P.; Ribeiro, A.B.S. Resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia—from molecular mechanisms to clinical relevance. Cancers 2021, 13, 4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Zhu, X.; Jia, H.; Zhou, L.; Liu, H. Combination therapies in chronic myeloid leukemia for potential treatment-free remission: focus on leukemia stem cells and immune modulation. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 643382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semedo, C.; Caroço, R.; Almeida, A.; Cardoso, B.A. Targeting the bone marrow niche, moving towards leukemia eradication. Front. Hematol. 2024, 3, 1429916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, L.; Li, L.; Lin, X.; Wang, F.; Li, Q.; Huang, Y. Overcoming chemotherapy resistance via simultaneous drug-efflux circumvention and mitochondrial targeting. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2019, 9, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Rezvani, H.R.; Aroua, N.; Bosc, C.; Farge, T.; Saland, E.; Guyonnet-Dupérat, V.; Zaghdoudi, S.; Jarrou, L.; Larrue, C.; Sabatier, M.; Mouchel, P.L.; Gotanègre, M.; Piechaczyk, M.; Bossis, G.; Récher, C.; Sarry, J.E. Targeting myeloperoxidase disrupts mitochondrial redox balance and overcomes cytarabine resistance in human acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 5191–5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsymbal, S.A.; Moiseeva, A.A.; Agadzhanian, N.A.; Efimova, S.S.; Markova, A.A.; Guk, D.A.; Krasnovskaya, O.O.; Alpatova, V.M.; Zaitsev, A.V.; Shibaeva, A.V.; Tatarskiy, V.V.; Dukhinova, M.S.; Ol’shevskaya, V.A.; Ostroumova, O.S.; Beloglazkina, E.K.; Shtil, A.A. Copper-containing nanoparticles and organic complexes: metal reduction triggers rapid cell death via oxidative burst. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polho, G.B.; Melo, A.A.R.; Ornelas-Filho, L.C.; Amaral, P.S.; Neto, F.L.; Soares, G.F.; Franco, A.S.; Bastos, D.A. Impact of bisphosphonates in hormone-sensitive metastatic prostate cancer a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2025, 23, 102438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, A.; Vandyke, K.; Augustson, B.; McCaughan, G.; Talaulikar, D.; Szabo, F.; Prince, H.M.; Ho, P.J.; Quach, H.; Harrison, S.J.; Lee, C.H. Medical Scientific Advisory Group to Myeloma Australia. Updated guidelines in the treatment of myeloma bone disease in 2025: consensus statement by the Medical and Scientific Advisory Group of Australia (MSAG) to Myeloma Australia. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Cai, J.; Sun, H.; Wei, X. Clinical and economic research of bone modifiers as adjuvant therapy for early breast cancer: A systematic literature review. Breast 2025, 83, 104551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massat, B.; Stiff, P.; Esmail, F.; Gauto-Mariotti, E.; Hagen, P. Preventing skeletal-related events in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Cells 2025, 14, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundesen, M.T.; Schjesvold, F.; Lund, T. Treatment of myeloma bone disease: When, how often, and for how long? J. Bone Oncol. 2025, 52, 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.W.; McKay, R.R. Mitigating the risk of skeletal events in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur. Urol. Focus 2025, 11, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damaj, N.; Najdi, T.; Seif, S.; Nakouzi, N.; Kattan, J. Zoledronic acid in metastatic castrate-sensitive prostate cancer: A state-of-the-art review. J. Bone Oncol. 2025, 51, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banti, C.N.; Kyros, L.; Geromichalos, G.D.; Kourkoumelis, N.; Kubicki, M.; Hadjikakou, S.K. A novel silver iodide metalo-drug: experimental and computational modelling assessment of its interaction with intracellular DNA, lipoxygenase and glutathione. Eur.J.Med.Chem. 2014, 77, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloglazkina, E.K.; Moiseeva, A.A.; Tsymbal, S.A.; Guk, D.A.; Kuzmin, M.A.; Krasnovskaya, O.O.; Borisov, R.S.; Barskaya, E.S.; Tafeenko, V.A.; Alpatova, V.M.; Zaitsev, A.V.; Finko, A.V.; Ol’shevskaya, V.A.; Shtil, A.A. The copper reduction potential determines the reductive cytotoxicity: relevance to the design of metal-organic antitumor drugs. Molecules 2024, 29, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, M.; Barrozo, A.; Straistari, T.; Queyriaux, N.; Putri, A.; Fize, J.; Giorgi, M.; Réglier, M.; Massin, J.; Hardréa, R.; Orio, M. Ligand-based electronic effects on the electrocatalytic hydrogen production by thiosemicarbazone nickel complexes†. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 5064–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaeva, L.L.; Lantsova, A.V.; Sanarova, E.V.; Orlova, O.L.; Oborotov, A.V.; Ignatieva, E.V.; Shprakh, Z S.; Kulbachevskaya, N.Yu.; Konyaeva, O.I. Development of the composition and technology for obtaining a model of an injection form of an indolocarbazole derivative. Pharm. Chem. J. 2023, 57, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantsova, A.V.; Sanarova, E.V.; Dmitrieva, M.V.; Orlova, O. L.; Shprakh, Z.S.; Bunyatyan, N. D.; Lantsova, D.A.; Kolpaksidi, A.P.; Eremina, V.A.; Ignatieva, E.V.; Gusev, D.V.; Nikolaeva, L.L. Application of technological and physical-chemical approaches to the development of injection forms of an indolocarbazole derivative. Pharm. Chem. J. 2024, 58, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Rodriguez, N.; Deininger, M.W. Novel treatment strategies for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 2025, 145, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarante-Mendes, G.P.; Rana, A.; Datoguia, T.S.; Hamerschlak, N.; Brumatti, G. BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase complex signaling transduction: challenges to overcome resistance in chronic myeloid leukemia. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holyoake, T.L.; Vetrie, D. The chronic myeloid leukemia stem cell: stemming the tide of persistence. Blood 2017, 129, 1595–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, T.; Pinho, S. leukemic stem cells: from leukemic niche biology to treatment opportunities. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 775128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.N.; Ruan, Y.; Ogana, H.; Kim, Y.-M. Cadherins, selectins, and integrins in CAM-DR in leukemia. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 592733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vianello, F.; Villanova, F.; Tisato, V.; Lymperi, S.; Ho, K.; Gomes, A.R.; Marin, D.; Bonnet, D.; Apperley, J.; Lam, E.W.-F.; Dazzi, F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells non-selectively protect chronic myeloid leukemia cells from imatinib-induced apoptosis via the CXCR4/CXCL12 Axis. Haematologica 2010, 95, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewry, N.N.; Nair, R.R.; Emmons, M.F.; Boulware, D.; Pinilla-Ibarz, J.; Hazlehurst, L.A. Stat3 contributes to resistance toward BCR-ABL inhibitors in a bone marrow microenvironment model of drug resistance. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 3169–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loscocco, F.; Visani, G.; Galimberti, S.; Curti, A.; Isidori, A. BCR-ABL independent mechanisms of resistance in chronic myeloid leukemia. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mian, A.A.; Rafiei, A.; Haberbosch, I.; Zeifman, A.; Titov, I.; Stroylov, V.; Metodieva, A.; Stroganov, O.; Novikov, F.; Brill, B.; Chilov, G.; Hoelzer, D.; Ottmann, O.G.; Ruthardt, M. PF-114, a potent and selective inhibitor of native and mutated BCR/ABL is active against Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) leukemias harboring the T315I mutation. Leukemia 2015, 29, 1104–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, E.S.; Tatarskiy, V.V.; Yastrebova, M.A.; Khamidullina, A.I.; Shunaev, A.V.; Kalinina, A.A.; Zeifman, A.A.; Novikov, F.N.; Dutikova, Y.V.; Chilov, G.G.; Shtil, A.A. PF-114, a new selective inhibitor of BCR-Abl tyrosine kinase, is a potent inducer of apoptosis in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 55, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkina, A.; Vinogradova, O.; Lomaia, E.; Shatokhina, E.; Shukhov, O.; Chelysheva, E.; Shikhbabaeva, D.; Nemchenko, I.; Petrova, A.; Bykova, A.; Siordiya, N.; Shuvaev, V.; Mikhailov, I.; Novikov, F.; Shulgina, V.; Hochhaus, A.; Ottmann, O.; Cortes, J.; Gale, R.P.; Chilov, G. Phase-1 study of vamotinib (PF-114), a 3rd generation BCR:ABL1 tyrosine kinase-inhibitor, in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Ann. Hematol. 2025, 104, 2707–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimov, A.G.; Tsymbal, S.A.; Finko, A.V.; Beloglazkina, E.K.; Shtil, A.A. Recalculating the cytotoxicity: a mathematical tool for characterization of non-linear effects of drug combinations. J. Theor. Comp. Sci. 2024, 10, 1000218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, M.; Kurata, M.; Onishi, I.; Yamamoto, R. Bone marrow niches in myeloid neoplasms. Pathol. Int. 2020, 70, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullaksen, S.-E.; Omsland, M.; Brevik, M.; Letzner, J.; Haugstvedt, S.; Gjertsen, B.T. CML stem cells and their interactions and adaptations to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Leuk. Lymphoma 2025, 66, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barachini, S.; Montali, M.; Burzi, I.S.; Pardini, E.; Sardo Infirri, G.; Cassano, R.; Petrini, I. The role of the bone marrow microenvironment in leukemic stem cell resistance: pathways of persistence and selection. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 105, 105090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allert, C.; Müller-Tidow, C.; Blank, M.F. The relevance of the hematopoietic niche for therapy resistance in acute myeloid leukemia. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 154, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigelin, B.; Friedel, P. T cell-mediated additive cytotoxicity – death by multiple bullets. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petiti, J.; Caria, S.; Revel, L.; Pegoraro, M.; Divieto, C. Standardized protocol for resazurin-based viability assays on a549 cell line for improving cytotoxicity data reliability. Cells 2024, 13, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).