Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

15 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- To validate the prototype in outdoor classrooms, assessing its ability to ensure continuous and safe charging under different environmental conditions.

- To optimize its operation through connectivity and IoT, incorporating sensors and real-time monitoring to record and analyze consumption and performance variables, enabling remote management and data-driven learning.

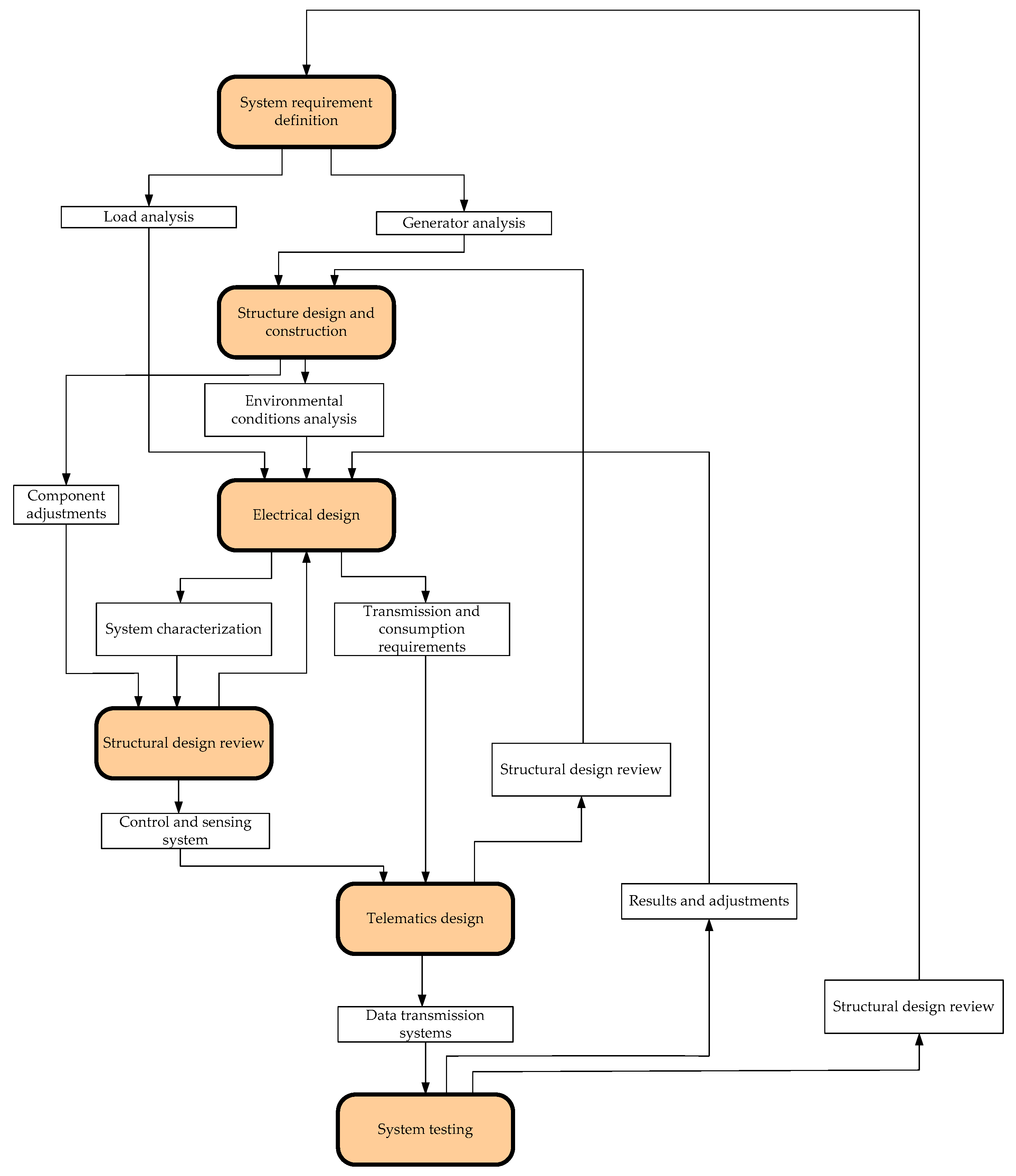

2. Materials and Methodology for Prototype Design and Testing

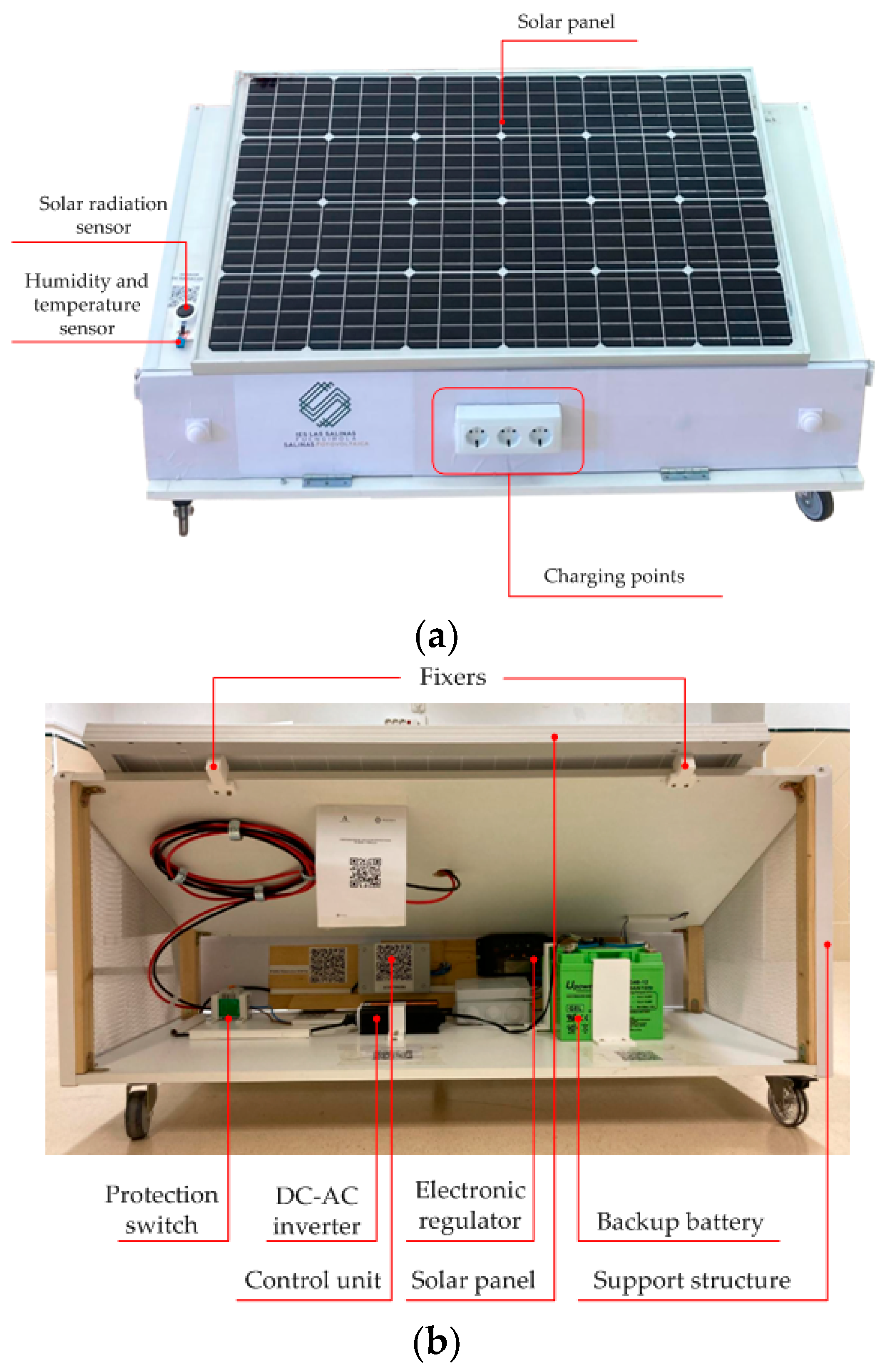

2.1. Structural Design and Assembling

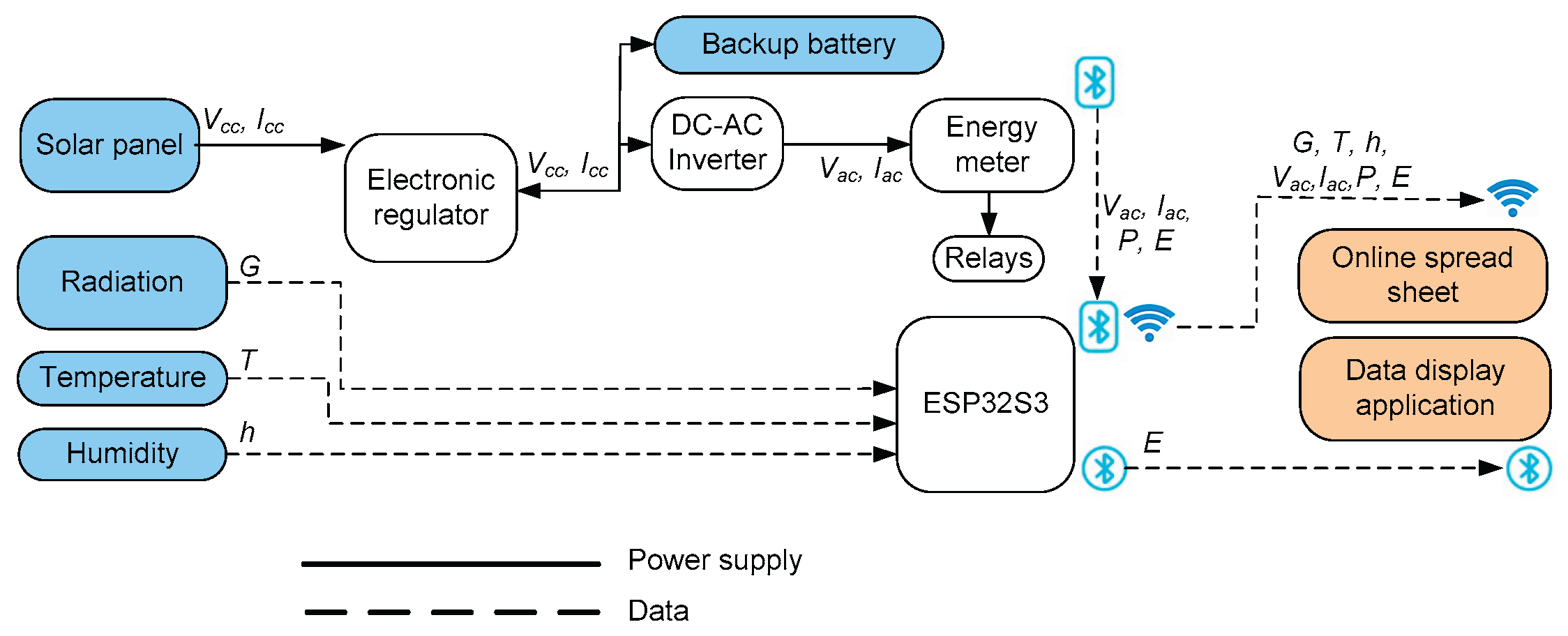

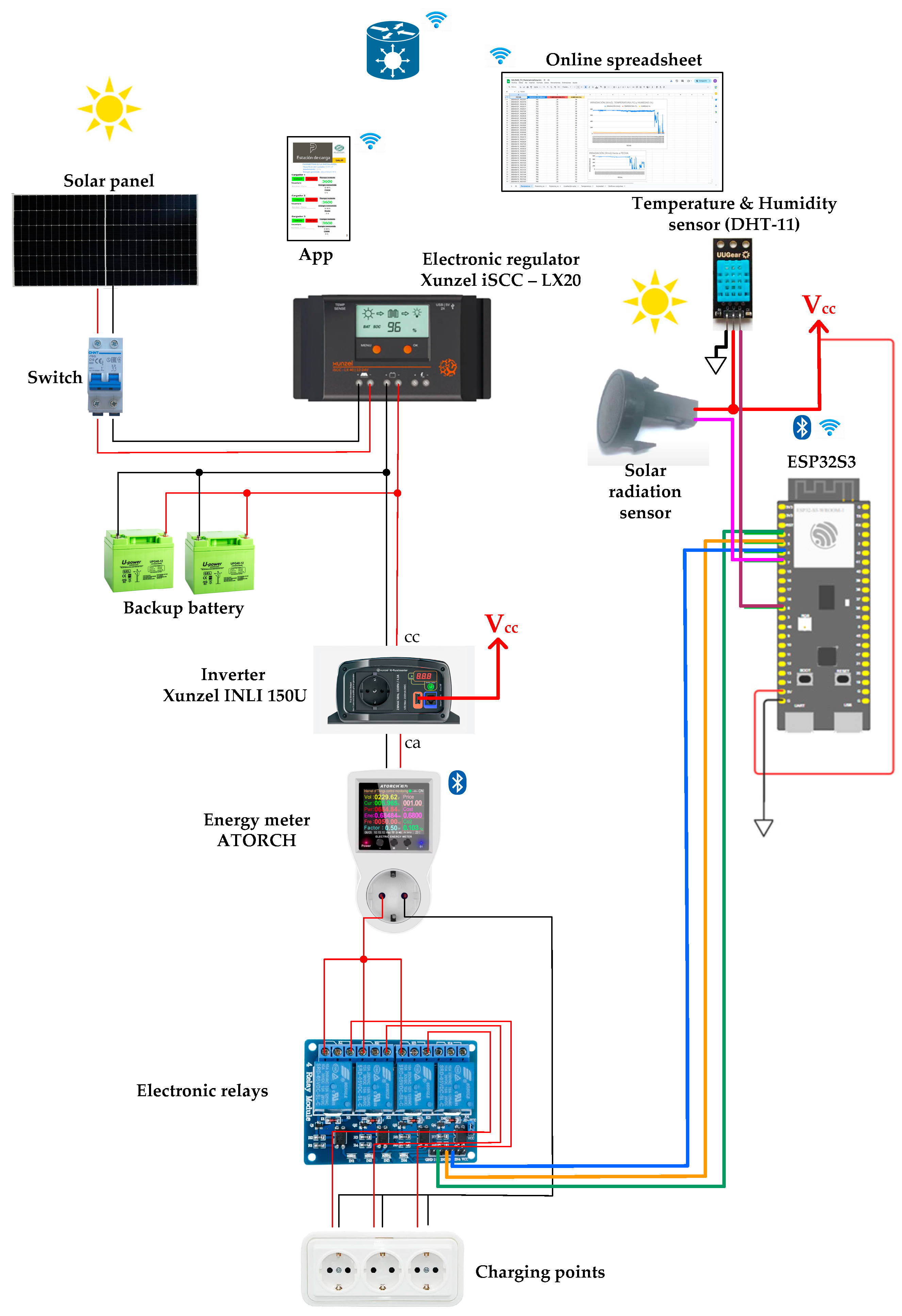

2.2. General Description

- Data Input Stage: The photovoltaic module supplies energy, and sensors (radiation, temperature, humidity) collect environmental data.

- Processing Stage: The processing subsystem (ESP32) regulates energy flow, controls electrical variables (voltage, current, power, energy), and monitors the battery state of charge, centralizing data management.

- Data Output Stage: The processed information is transmitted for visualization, storage, and analysis (cloud spreadsheets and mobile application), enabling real-time system status monitoring and efficient management.

- Data Input Block: Photovoltaic energy generation (panel and Xunzel iSCC–LX 20 charge controller), energy storage (backup battery and regulator), and energy conversion (modified sine wave inverter with PWM techniques).

- Processing Block: Distribution and control (relay block managed by the ESP32), and monitoring and measurement (ATORCH energy meter and other sensors, data sent to the ESP32).

- Data Output Block: The ESP32 transmits real-time data (mobile application, cloud database, spreadsheet) for monitoring and optimization.

2.3. Electrical System

- Photovoltaic generator. It is the primary energy source of the system, supplying power directly to the devices or charging the batteries (Table 1)

- Backup Batteries. The two batteries, connected in parallel, store energy to ensure continuous power supply when the photovoltaic generator is insufficient. Their specifications are shown in Table 2:

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Nominal Voltage (VN) | 12 V |

| Capacity (C) | 24 Ah |

| Maximum Stored Energy (Emáx) | 480 Wh |

- Xunzel iSCC-LX Regulator. Solar charge controller for low-power photovoltaic systems. It intelligently manages the charging and discharging of the batteries, protecting them from overcharge and deep discharge. Its specifications are shown in Table 3:

- MJ-Xunzel 500 Power Inverter. Modified sine wave inverter that converts 12 V direct current (DC) into 230 V alternating current (AC). Its specifications are shown in Table 4.

2.3. Data Acquisition System

-

Processing Subsystem. This subsystem is coordinated by an ESP32-S3-DevKitC-1 XTVTX WROOM-1-N16R8 controller board [17]. It enables remote communication (WiFi) with a control application and Google Sheets, and activates control relays for the power outlets.

- a.

- It utilizes the ESP32-S3 microcontroller [17], suitable for IoT applications.

- b.

- It is provided with a 32-bit dual-core LX7 processor running up to 240 MHz, 512 KB of SRAM, and 8 MB of external PSRAM.

- c.

- It features 2.4 GHz WiFi and Bluetooth 5.0 (LE) connectivity. Bluetooth 5.0 (LE) is suitable for local communication with other devices, such as the AC energy meter.

- d.

- It includes a low-power mode, which is suitable for solar projects.

- Sensing Subsystem. This subsystem provides data on environmental and electrical conditions to analyze their relationship with the system’s performance.

- Solar Radiation Sensor SUF268J001: Measures the incident solar energy to evaluate the generative capacity (Table 5):

-

Electric sensors. They optimize performance, manage the system, detect faults, and assess efficiency:

- a.

- b.

- Renogy Wanderer PG Smart Charge Controller [21]: This device manages the energy flow between the photovoltaic modules and the batteries, providing real-time data such as battery voltage, module voltage, charging current, and state of charge (SOC).

- WiFi (IEEE 802.11): Used by the ESP32S3 for the primary link to the internet gateway (mobile phone). Its high bandwidth supports the functionality of near real-time monitoring and data transmission to the cloud.

- Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE): Chosen for low-power, short-range communication between the ESP32S3 and local electrical sensors (BT-1 for DC, Atorch for AC). Its minimal energy consumption is vital for the efficiency of the solar-powered system.

- MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport): Adopted as the lightweight, publish-subscribe protocol for cloud data transmission. Its low overhead minimizes bandwidth use, facilitating scalability by efficiently handling data from many devices.

- NTP (Network Time Protocol): Integrated to synchronize the ESP32S3 clock. Accurate timestamping ensures data integrity and is fundamental for reliable functionality and time-series analysis.

- Google Cloud Platform (GCP)—Google Sheets: Used for centralized, accessible data storage via MQTT. It provides a cost-effective repository, supporting scalability and easy archiving of large datasets.

- Firebase: Selected as the real-time backend for dynamic data visualization and mobile app synchronization. Its low-latency synchronization ensures instantaneous access to operational status, which is key for efficiency through proactive fault detection and enhanced operator functionality.

2.4. Prototype Development

3. Results

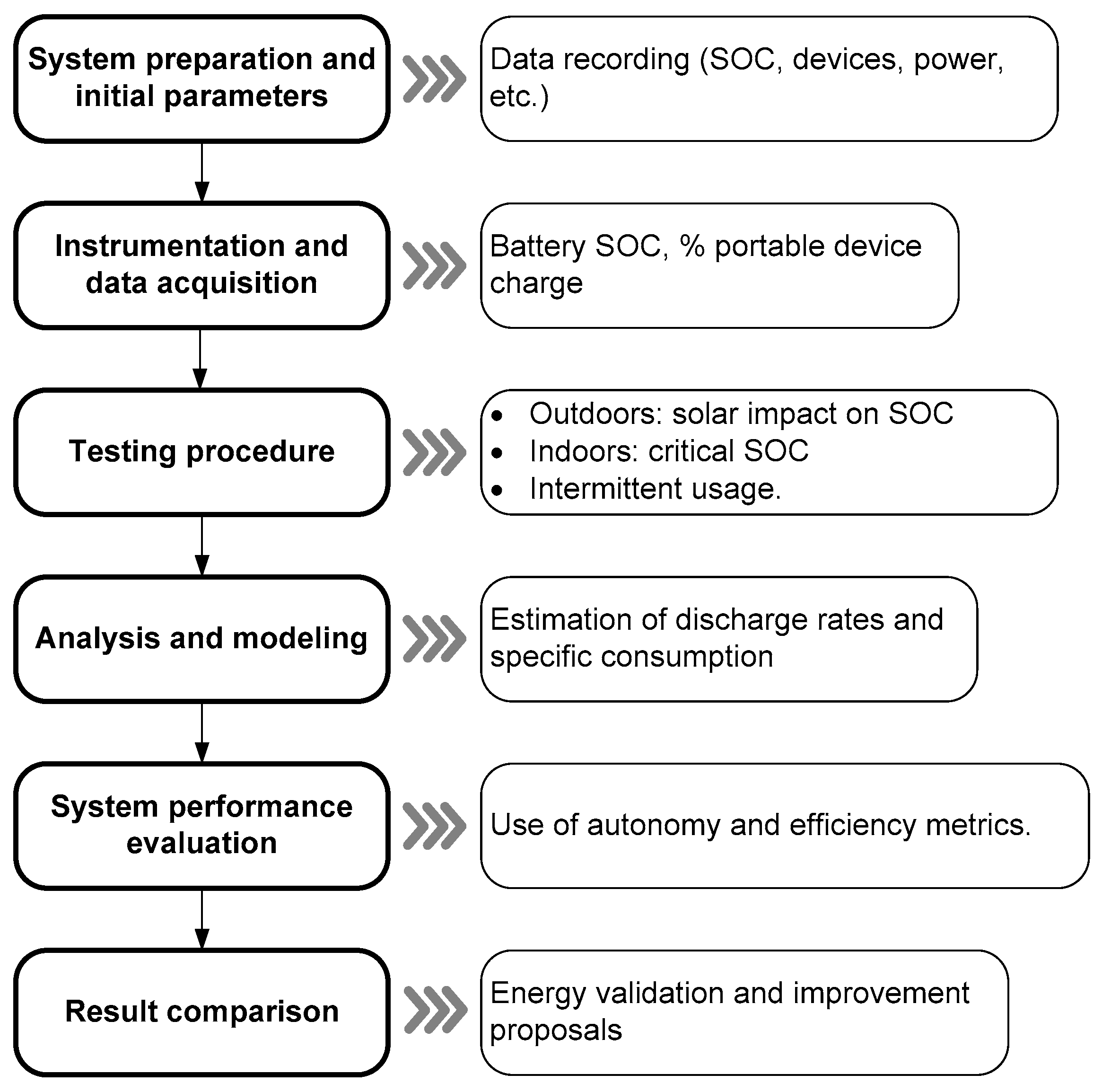

3.1. Charging Station Testing Method

- Outdoor application: designed for use in direct sunlight, mimicking the conditions of an outdoor classroom setting, such as a school garden.

- Indoor application: no solar exposure, simulating usage in a typical classroom setting.

- Interleaved load-use: simulation of routines with alternating consumption and photovoltaic generation.

- 1.

- System preparation and initial parameters. In the preparation of the tests, the minimum recommended battery state of charge (SOC) was established as the initial condition, based on the values estimated in Table 2. This decision was derived from prior energy calculations required to power the three laptops during the target hours of each month. The following criterion was applied: since months with lower solar irradiance—such as December—represent the most unfavorable conditions, the battery was ensured to start at a SOC sufficient to cover the expected energy demand of the laptops. This approach provided a uniform and comparable starting point for all tests, avoiding the influence of variations in the initial battery charge on the results. Table 2 shows the estimated SOC percentages required at 08:30 h to maintain operation of the three laptops until the target hours. For instance, in December, at least 36% SOC is required at 08:30 h to operate until 09:30 h, and 72% SOC to reach 10:30 h, reflecting the lower solar availability during this month. In months with higher irradiance, such as June or July, the required initial SOC is lower, highlighting that the energy reserve directly depends on the expected solar radiation. This approach ensures that the tests faithfully represent the system’s ability to power the laptops under the most critical conditions, allowing for a reliable assessment of the battery and solar system performance throughout the year.

| Month | 08:30h | 09:30h | 10:30h | 12:00h | 13:00h | 14:00h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 0.0% | 35% | 70% | 123% | — | — |

| Feb | 0.0% | 33% | 66% | 108% | — | — |

| Mar | 0.0% | 28% | 56% | 86% | 110% | — |

| Apr | 0.0% | 25% | 49% | 75% | 99% | — |

| May | 0.0% | 22% | 44% | 65% | 87% | 110% |

| June | 0.0% | 20% | 40% | 59% | 76% | 94% |

| July | 0.0% | 20% | 39% | 58% | 75% | 92% |

| Aug | 0.0% | 22% | 43% | 64% | 84% | 100% |

| Sept | 0.0% | 26% | 52% | 80% | 104% | — |

| Oct | 0.0% | 31% | 62% | 95% | 122% | — |

| Nov | 0.0% | 34% | 69% | 100%+ | — | — |

| Dec | 0.0% | 36% | 72% | 100%+ | — | — |

- 2.

-

Instrumentation and Data Logging. The system was continuously monitored, minute by minute, using the charge controller and IoT system sensors. The key parameters recorded were

- Station battery SOC.

- Charge percentage of each laptop

- Current and voltage on the charging bus (panels and consumption).

- Power delivered by and consumed by the station

- 3.

-

Testing Procedure. The prototype evaluation protocol was designed to replicate the main usage conditions expected in educational environments, both outdoors with sunlight and indoors without direct irradiance. To this end, three complementary test modalities were established, allowing the system’s performance to be analyzed from different perspectives:

- a.

- Outdoors: full workdays were conducted with two work periods (8:30–11:30 and 12:00–15:00) and a 30-minute break for charging. The three laptops started at 100% charge (≈210 Wh), and the charging station at 288 Wh plus the usable portion of the additional 960 Wh battery (recommended SOC ≥60%). In the first period (630 Wh), 94.6 Wh was supplied by the solar panel, 210 Wh by the internal batteries, and 325.4 Wh by the charging station. During the break, the solar panel supplied 15.3 Wh and the charging station 14.7 Wh. In the second period (630 Wh), the solar panel supplied another 94.6 Wh, the internal batteries 30 Wh, and the charging station 505.4 Wh. Total consumption is 1290 Wh over 6.5 hours: 16% from the panel, 18.6% from the internal batteries, and 65.5% from the station, confirming the need to start with a high charge in the auxiliary battery on days with low irradiance. The analysis compared with theoretical estimates (Table 2 and Table 3) evaluates the monthly autonomy with solar input, the possibility of reaching energy class changes (“Yes/No/Partial”), and the minimum State of Charge (SOC) required at 8:30 a.m. to guarantee one-hour sessions. These tables allow for planning usage and adjusting the number of devices or storage capacity.

- b.

- Interiores: the students carried out continuous download sessions until reaching critical SOC (0–20%), determining the actual autonomy by number of laptops connected (1, 2 or 3) and validating the expected inverse proportionality.

- c.

- Interleaved load-use: routines were simulated with alternating periods of consumption and photovoltaic charging, modeling the evolution of the SOC and verifying if the system could maintain sustained operation throughout a school day.

- 4.

- Linear SOC-time models were used to estimate average discharge rates and the specific power consumption of each laptop, in order to predict how the state of charge would evolve throughout the day. In scenarios with solar generation, the hourly Production-Consumption balance was integrated to detect when energy surpluses or deficits would occur and to anticipate possible power outages. Furthermore, the actual system efficiency (85–90%) was considered to adjust the autonomy forecasts, and the initial SOC required to meet the duration targets was calculated in the worst-case scenario.

- 5.

-

The charging station’s performance was evaluated using the following metrics:

- a.

- Effective autonomy (h) per scenario and number of devices

- b.

- Relative charging efficiency (Wh usable / %SOC consumed).

- c.

- Minimum SOC required to cover the day without interruptions.

- 6.

- Finally, a comparison was made between actual results and simulations to validate the energy model.

3.2. Expected Results

3.2.1. Trial Conditions

3.2.2. Energy Modeling and Autonomy Assessment

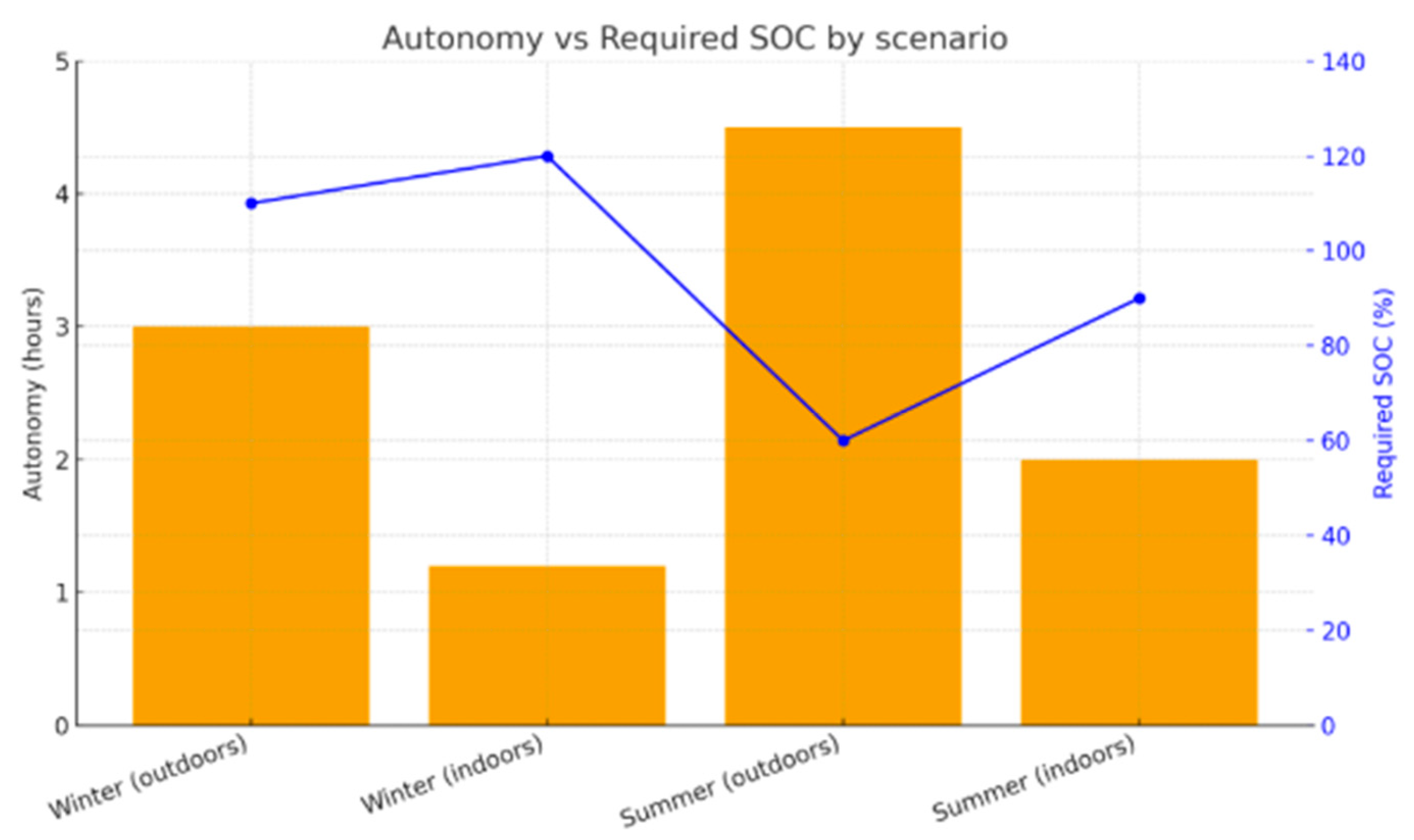

- Viability in summer: It was projected that in months with high radiation (e.g., June and July, 7.6 kWh/m2 day), the station could sustain the continuous operation of three portable units for more than 4 hours, reaching the morning usage period (08:30–12:30) with an initial SOC of 60%.

-

Critical limitation indoors or in winter outdoors: Simulations anticipated insufficient performance under unfavorable conditions:

- ○

- In winter (e.g., December, 2.4 kWh/m²/day), the maximum autonomy would be reduced to 2.8–3 hours, limiting service to the first half of the day. To meet demand, an initial State of Customer (SOC) greater than 100% of current capacity would be required.

- ○

- In indoor scenarios, the current battery bank (24 Ah, approximately 288 Wh nominal) was considered barely sufficient for one hour of continuous use with three laptops, confirming that the current capacity is insufficient for academic sessions without external support.

3.3. Obtained Results

3.3.1. Experimental Evaluation of Energy Parameters

- Supplied energy: he station provided between 180 Wh and 220 Wh during a typical class session of approximately 4 hours, values that closely match the demand estimated in the simulations (~200 Wh).

- Outdoor autonomy (summer): The station sustained the operation of three laptops for more than 4 continuous hours, confirming the system’s viability under average summer irradiance conditions of approximately 7.6 kWh/m²·day.

- Outdoor autonomy (winter): Maximum runtime decreased to approximately 2.5–3 hours, which is insufficient to support a full school day without additional energy sources, consistent with the projections from the simulations.

- Indoor conditions: With an initial SOC of 70%, the battery supported operation for slightly more than 1 hour with three laptops connected, confirming the limited capacity of the current battery bank (24 Ah).

- Measured SOC: On favorable days, an initial SOC of around 60% was sufficient to support operation during the morning period, whereas in December, an SOC close to the full usable capacity (~100%) was required, reinforcing the need for increased storage capacity.

- Conversion losses: Losses between 15% and 25% were observed, values consistent with the theoretical assumptions used in the simulations.

| Scenario | Initial SOC | Provided energy (Wh) | System autonomy | Required SOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outdoor—summer | 60% | 200–220 | 4–4,2 h w/ 3 portable computers | ≥ 60% |

| Outdoor—winter | 100% | 180–190 | 2,5–3 h w/ 3 portable computers | ≥ 95–100% |

| Indoor | 70% | 70–90 | 1–1,2 h w/ 3 portable computers | ≥ 70% |

| W/Backup battery LiFePO₄ 100 Ah | 70% + FV | 1450 | Full time (≈ 6,5 h) |

≥ 70% |

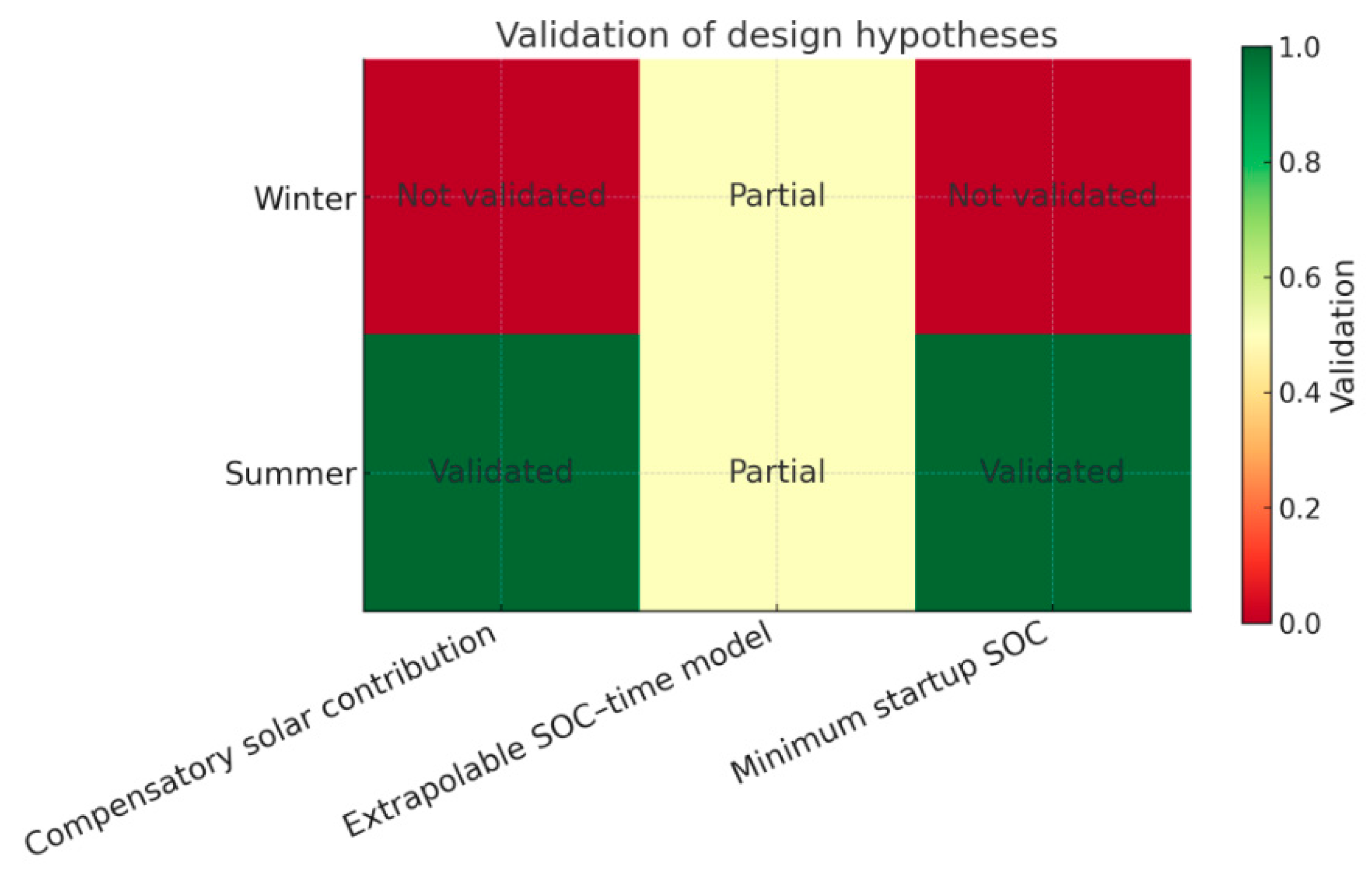

3.3.2. Verification of the System Design Assumptions

- The battery would start each day with a sufficient minimum State of Charge (SOC) to support the simultaneous operation of three laptops for at least one hour..

- Direct solar energy input would partially compensate the load demand, thereby reducing the net discharge rate of the battery bank.

- The theoretical energy balance model (SOC–time relationship) would remain valid when extrapolated to different seasonal irradiance conditions (e.g., summer vs. winter).

- Viability confirmed: The theoretical minimum SOC of 18% proved sufficient. With an initial SOC of 53%, the system maintained a remaining 36% after the first hour of continuous operation with three laptops..

- Session limit: The combined contribution of the battery (750 Wh total capacity) and solar input (~66 Wh/h) was sufficient to meet the peak demand of 171 Wh. However, for extended operation beyond 10:00 h, a marked decline in SOC was observed, indicating the need for active energy management when aiming for longer sessions

- Substantial reduction in battery life: with the current battery bank (28 Ah, 336 Wh nominal), the measured autonomy dropped to 2.3 hours with one laptop, 1.2 hours with two laptops, and barely 47 minutes with three laptops connected..

- Hypothesis not fulfilled: In winter conditions, the reduced solar input combined with the limitations of the PWM charge controller was insufficient to meet the load demand. The SOC fell to critical levels in under one hour, invalidating the assumption that the system could continuously power three laptops throughout a full school day.

3.3.3. Comparison with Previous Studies

4. Discussion

- 1.

-

Viability under high irradiance conditions (summer):

- ○

- ○

- ○

- 2.

-

Critical limitation under low irradiance (winter or indoor conditions):

- ○

- Autonomy was insufficient in winter and indoor scenarios. Maximum operation times dropped to 2.5–3 hours, well below the required 6.5 hours, and fell to around 1 hour under indoor conditions. This aligns with AEMET solar irradiance data showing a strong seasonal reduction in available solar energy in northern and central Spain [3].

- ○

- ○

- Low solar contribution combined with the relatively low efficiency of the PWM regulator (15–25% losses) under these conditions did not compensate for the demand, highlighting a key limitation in design that mirrors findings from prior research on solar charging stations and zero-energy buildings [5,6].

- ○

- ○

- ○

5. Conclusions

- Need for expansion: The simulation confirms that an additional battery (12 V–100 Ah–LiFePO4) is required to achieve daily operational robustness.

- Efficiency optimization: The low efficiency of the PWM regulator underscores the recommendation to incorporate MPPT controllers to maximize solar energy harvesting.

- Added value of IoT. Real-time IoT monitoring was essential to validate the energy model and served as a pedagogical tool for load management.

Appendix A. Glossary

Appendix B. Acknowledgments

References

- International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2023, pp. 17, 20, 48, 90, 2023.

- Observatorio de la Movilidad Eléctrica, “Informe OBS Movilidad Eléctrica 2024,” pp. 4-7, 18, 63-77, 2024.

- Agencia Estatal de Meteorología (AEMET), Atlas de radiación solar en España usando datos del SAF de Clima de EUMETSAT, Madrid, España: AEMET, 2012. Disponible en: https://www.aemet.es/documentos/es/serviciosclimaticos/datosclimatologicos/atlas_radiacion_solar/atlas_de_radiacion_24042012.pdf.

- Hernández Arauzo, A., Puente Peinador, J., González, M. A., Varela Arias, J. R., & Sedano Franco, J. (2013). Dynamic scheduling of electric vehicle charging under limited power and phase balance constraints. In Proceedings of SPARK 2013-Scheduling and Planning Applications woRKshop. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence.

- Iqbal, M.T., “A feasibility study of a zero energy home in Newfoundland” Renewable Energy, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 277–289, 2004.

- M. R. Hajidavalloo, F. A. Shirazi, y M. J. Mahjoob, “Performance of different optimal charging schemes in a solar charging station using dynamic programming,” Optimal Control Applications and Methods, vol. 41, no. 6, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Chen, T. Q. S. Quek and C. W. Tan, “Optimal charging of electric vehicles in smart grid: Characterization and valley-filling algorithms,” 2012 IEEE Third International Conference on Smart Grid Communications (SmartGridComm), Tainan, Taiwan, 2012, pp. 13-18. [CrossRef]

- Sedano, J., Portal, M., Hernández-Arauzo, A., Villar, J. R., Puente, J., & Varela, R. (2013). Sistema inteligente de recarga de vehículos eléctricos: diseño y operación. Dyna, 88(6), 644-651.

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Innovation Outlook: Electric Vehicles and Smart Charging, 2019.

- Timpner, J., & Wolf, L. (2012, March). A back-end system for an autonomous parking and charging system for electric vehicles. In 2012 IEEE International Electric Vehicle Conference (pp. 1-8). IEEE.

- Nouali, O., Moussaoui, S., & Derder, A. (2015, November). A BLE-based data collection system for IoT. In 2015 First International Conference on New Technologies of Information and Communication (NTIC) (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- DeBell, T., Goertzen, L., Larson, L., Selbie, W., Selker, J., & Udell, C. (2019). Opens hub: Real-time data logging, connecting field sensors to google sheets. Frontiers in Earth Science, 7, 137.

- Cao, H., Gonzales, J., Dimetry, N., Cate, J., Huynh, R., & Le, H. T. (2019). A solar-based versatile charging station for consumer ac-dc portable devices. International Journal of Education and Learning Systems, 4.

- Akankpo, A. O., Adeniran, A. O., Ayedun, F., Anyanor, O. O., & Ebong, G. (2023). Development and Construction of Portable Solar Power Packs for Laptops and Small Devices. Journal of Research in Environmental and Earth Sciences, 9(1), 5-63.

- Oliveira, S., Pessoa, M. S. P., & de Alencar, D. B. A Solar Powered Electronic Device Charging Station. 2019.

- Espressif Systems. (n.d.). ESP32-S3-DevKitC-1. Espressif Systems Documentation. https://docs.espressif.com/projects/esp-dev-kits/en/latest/esp32s3/esp32-s3-devkitc-1/index.html.

- Vishay Intertechnology. (n.d.). SUF268J001 datasheet [Hoja de datos]. Digi-Key. https://www.digikey.com/es/htmldatasheets/production/1812215/0/0/1/suf268j001-datasheet.

- Aosong Electronics Co., Ltd. (n.d.). DHT11 Technical Data Sheet [Hoja de datos]. Mouser Electronics. https://www.mouser.com/datasheet/2/758/DHT11-Technical-Data-Sheet-Translated-Version-1143054.pdf.

- Atorch. (n.d.). Atorch S1 manual [Manual]. Manualslib. https://www.manualslib.com/manual/3065332/Atorch-S1.html.

- Renogy. (n.d.). WND10 datasheet [Hoja de datos]. Renogy. https://www.renogy.com/content/RNG-CTRL-WND10/WND10-Datasheet.pdf.

- Renogy. (n.d.). WND10 datasheet [Hoja de datos]. Renogy. https://www.renogy.com/content/RNG-CTRL-WND10/WND10-Datasheet.pdf.

- Tran, B., Ovalle, J., Molina, K., Molina, R., & Le, H. T. (2021). Solar-powered convenient charging station for mobile devices with wireless charging capability. WSEAS Transactions on Systems, 20, 260-271.

- Ravichandran, S., Kaliaperumal, G., & Nesaian, M. L. (2024, August). Green energy powered portable charging station. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 3044, No. 1, p. 030003). AIP Publishing LLC.

- Chowdhury, O. R., Rahman, M. M., & Hossain, M. F. (2021). Establishment of solar powered green canopy smart device charging station. International Journal of Progressive Sciences and Technologies, 29(2), 323–330. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., Avhad, J., Thakur, R., Dham, A. S., & Parve, K. (2024). Solar powered mobile charging unit. International Journal of Innovative Research in Electrical, Electronics, Instrumentation and Control Engineering, 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Rus-Casas, C., Hontoria, L., Jiménez-Torres, M., Muñoz-Rodríguez, F. J., & Almonacid, F. (2014). Virtual laboratory for the training and learning of the subject solar resource: OrientSol 2.0. In 2014 XI Tecnologías Aplicadas a la Enseñanza de la Electrónica (TAEE) (pp. 1–6). Bilbao, Spain. [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, C. P., Prabu, P., & Niruba, K. (2013, December). Solar potential assessment using PVSYST software. In 2013 International Conference on Green Computing, Communication and Conservation of Energy (ICGCE). [CrossRef]

- PVSYST, Design and simulation software for your photovoltaic systems. https://www.pvsyst.com/.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Maximum Power (Pmax) | 120 W |

| Open-Circuit Voltage (Voc) | 23,80 V |

| Voltage at Maximum Power Point (Vpmáx) | 20,10 V |

| Shotcircuit current (Isc) | 6,36 A |

| Current at Maximum Power Point (Ipmáx) | 5,98 A |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Nominal Voltage (VN) | 12 / 24V |

| Maximum Power (Pmax) | 360 Wp (12V) 720 Wp (24V) |

| Maximum Charging Current (ILmáx) | 20A |

| Pulse Shaping Technology | PWM |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Nominal Power (PN) | 500 W |

| Maximum power (Pmax) | 1000 W |

| Waveform Type | Modified Sine Wave |

| Parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| Lighting Source | Tª = 2856 K, 767.4 W/m² or 17,359 LUX. |

| Measurement Range | 0–2000 W/m². |

| Response Time | < 10 secs. |

| Electrical Output | Analog signal (tipically 0-2.5 V or 4-20 mA, depending on the model). |

| Parameter | Range | Accuracy | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative humidity | 20%–90% | ±5% | 1% |

| Temperature | 0 °C–50 °C | ±2 °C | 1 °C |

| Parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| Input voltage | 85Vac– 265Vac. |

| Maximum current | 16A |

| Maximum power | 3680W |

| Standards | GB/T12116-2012 and GB/T6587-2012 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.