Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

15 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Outcomes

- -

- Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS): a 10-item questionnaire used to monitor depressive symptoms and define the severity of MDD during follow-up.

- -

- Psychache Scale (PS): a 13-item scale used to assess the profile of psychological pain. Some questions demand a frequency rating (from “never” to “always”), while other ones demand an agreement rating (from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”).

- -

- Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS): a structured test to evaluate suicidal ideation and/or behaviour. It is composed by 10 categories of which the majority calls for a binary response yes/no (e.g., suicidal attempts yes/no). When suicidal thoughts and/or behaviour were present, the sub-scale which measures the intensity of ideation (1-5) was reported and considered as a follow-up tool.

- -

- Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q): a subjective investigation about quality of life, which includes different domains (school, work, housework, social relationships, physical state, leisure time, general activities). Every sub-score can be associated with a percentage of satisfaction: the mean of these eight percentages defines the global quality of life perceived by patients.

- -

- Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET): a specific test which measures the Theory of Mind and the ability to recognize mental states in other people. It consists of 36 different photographs: for each, patient should indicate what person in the picture is feeling/thinking. It has been noticed that autistic people under-perform on this test as compared to neurotypical population[17].

- -

- Reflective Functioning Questionnaire – 8 items (RFQ-8): a brief, easy to administer screening to evaluate mentalization, coming from a 54-item test[18]. It is focused on reflective functioning intended as the ability to recognize our feelings and our mental states before acting. This test is organized as a Likert-type scale, with responses from “completely agree” (7) to “completely disagree” (1). Higher scores in the RFQ-8 show a lower ability in mentalization.

2.5. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

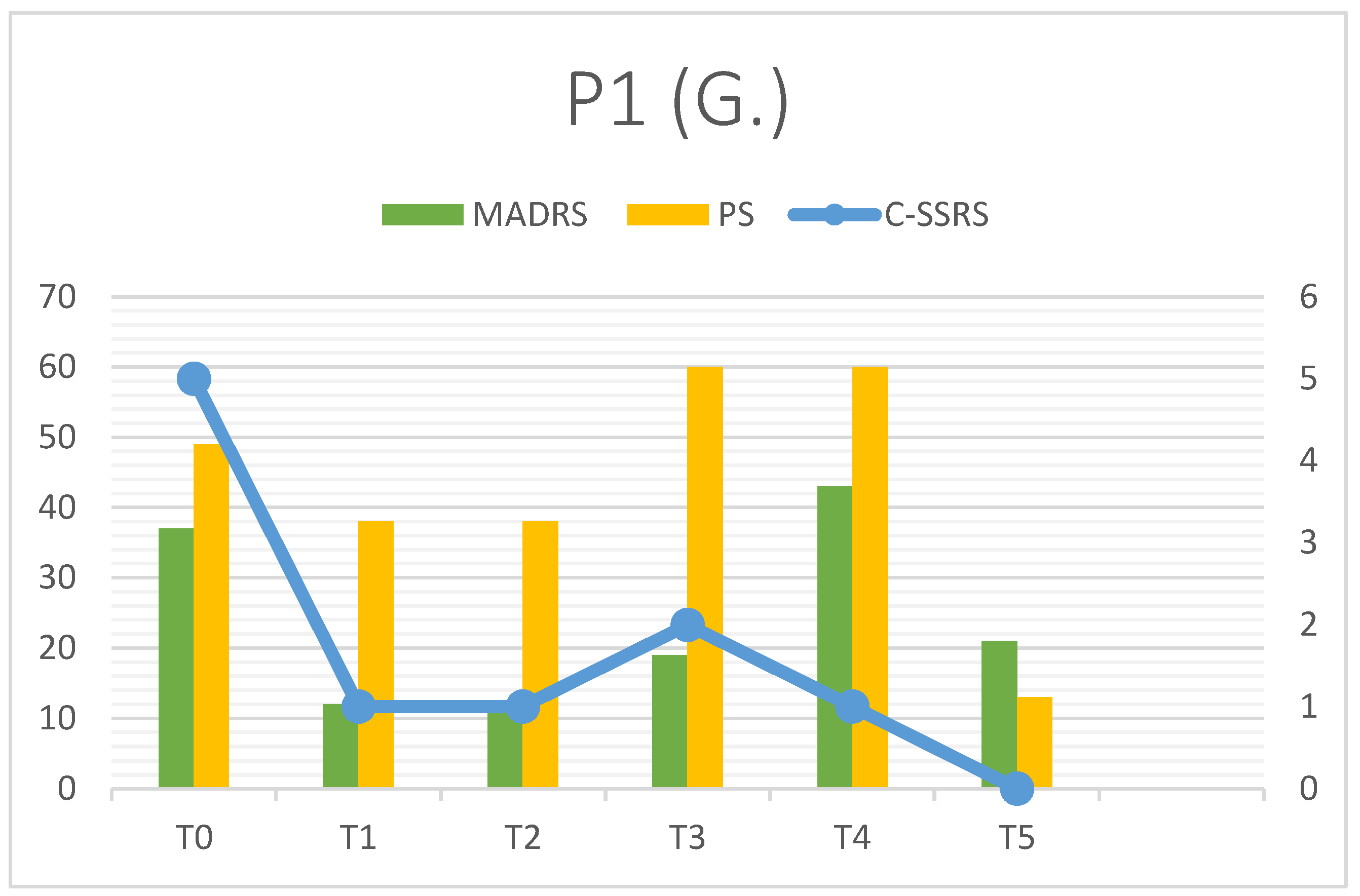

3.1. Patient 1

| P1 | MADRS | C-SSRS | PS | RFQ-8 | RMET | Q-LES-Q(%) |

| T0 | 37 | 5 | 49 | 4.125 | 27 | 28 |

| T1 | 12 | 1 | 38 | 4.25 | 31 | - |

| T2 | 12 | 1 | 38 | 4.25 | 30 | - |

| T3 | 19 | 2 | 60 | 4.5 | 32 | - |

| T4 | 43 | 1 | 60 | 3.125 | 34 | - |

| T5 | 21 | 0 | 13 | 2.75 | 34 | 73 |

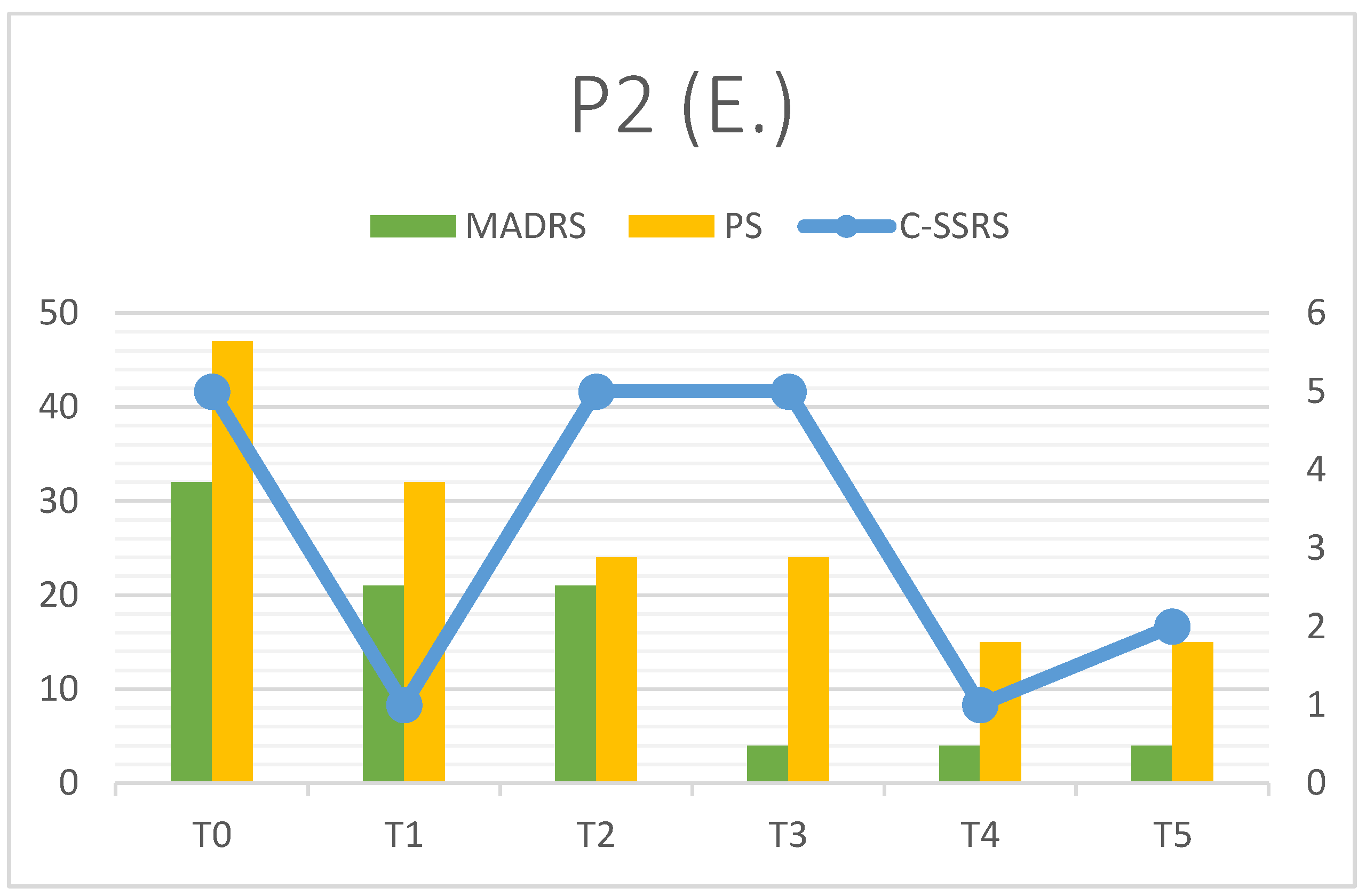

3.2. Patient 2

| P2 | MADRS | C-SSRS | PS | RFQ-8 | RMET | Q-LES-Q(%) |

| T0 | 32 | 5 | 47 | 2.5 | 26 | 25 |

| T1 | 21 | 1 | 32 | 2.25 | 22 | - |

| T2 | 21 | 5 | 24 | 2 | 23 | - |

| T3 | 4 | 5 | 24 | 2 | 23 | - |

| T4 | 4 | 1 | 15 | 2 | 23 | - |

| T5 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 23 | 71 |

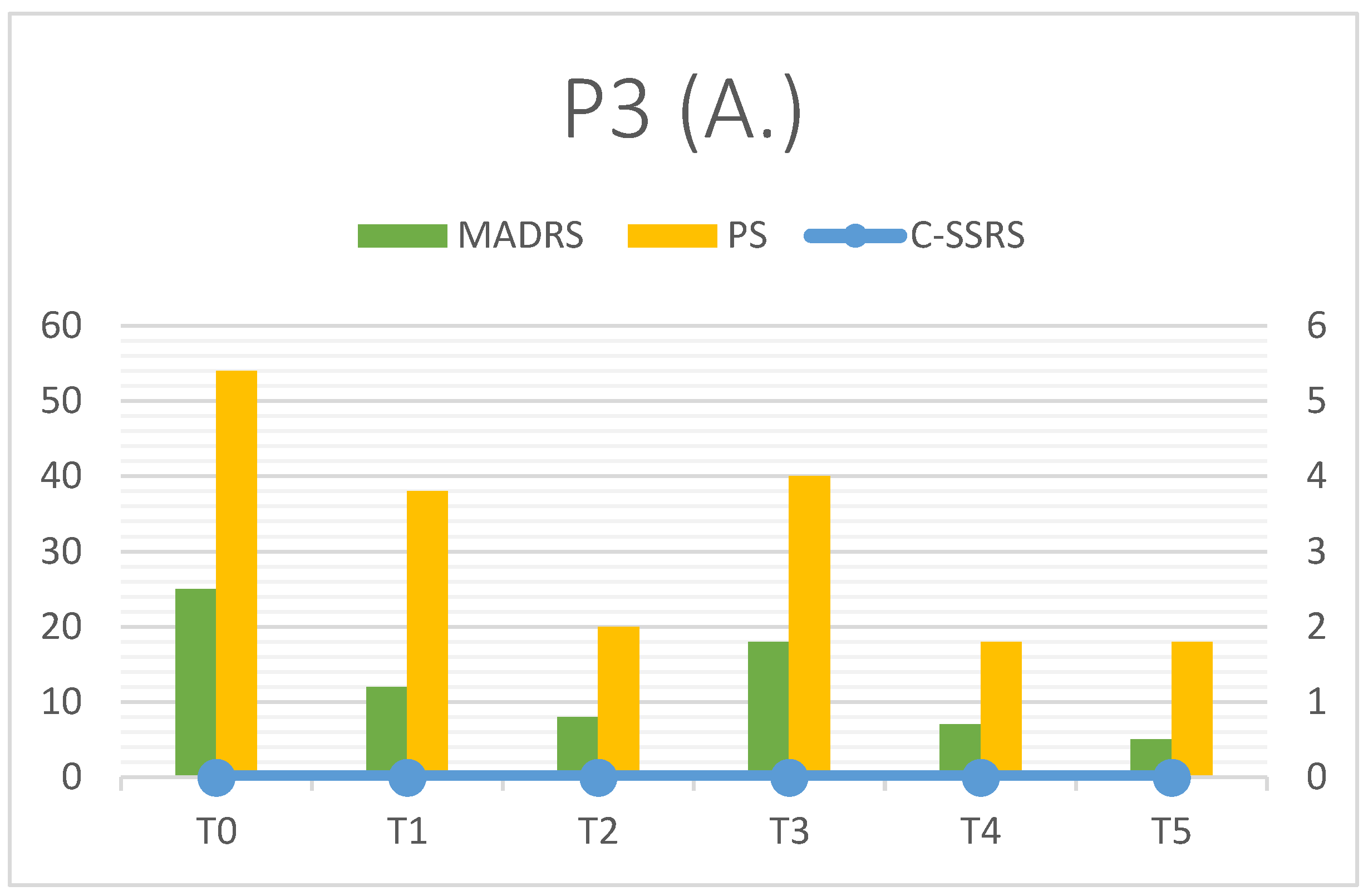

3.3. Patient 3

| P3 | MADRS | C-SSRS | PS | RFQ-8 | RMET | Q-LES-Q(%) |

| T0 | 25 | 0 | 54 | 2 | 26 | 35 |

| T1 | 12 | 0 | 38 | 3 | 27 | - |

| T2 | 8 | 0 | 20 | 4 | 25 | - |

| T3 | 18 | 0 | 40 | 3 | 26 | - |

| T4 | 7 | 0 | 18 | 4 | 28 | - |

| T5 | 5 | 0 | 18 | 4 | 29 | 80 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings and Interpretation

4.2. Comparison to Literature

4.3. Strength and Limitations

4.4. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

References

- Malhi, GS; Mann, JJ. Depression. Lancet 2018, 392(10161), 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Depressive disorders (depression). 29 August 2025. Available online: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

- McIntyre, RS; Filteau, MJ; Martin, L; Patry, S; Carvalho, A; Cha, DS; Barakat, M; Miguelez, M. Treatment-resistant depression: definitions, review of the evidence, and algorithmic approach. J Affect Disord 2014, 156, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, SM; Köhler-Forsberg, O; Moss-Morris, R; Mehnert, A; Miranda, JJ; Bullinger, M; Steptoe, A; Whooley, MA; Otte, C. Comorbid depression in medical diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020, 6(1), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, MC; Kassee, C; Besney, R; Bonato, S; Hull, L; Mandy, W; Szatmari, P; Ameis, SH. Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6(10), 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richa, S; Fahed, M; Khoury, E; Mishara, B. Suicide in autism spectrum disorders. Arch Suicide Res. 2014, 18(4), 327–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, R. G.; Cargill, M. I.; Khawar, S.; Kang, E. Emotion dysregulation in autism: A meta-analysis. Autism 2024, 28(12), 2986–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Massoni, L.; Battaglini, S.; De Felice, C.; Nardi, B.; Amatori, G.; Cremone, I. M.; Carpita, B. Emotional dysregulation as a part of the autism spectrum continuum: a literature review from late childhood to adulthood. Frontiers in psychiatry 2023, 14, 1234518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazefsky, CA; Herrington, J; Siegel, M; Scarpa, A; Maddox, BB; Scahill, L; White, SW. The role of emotion regulation in autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013, 52(7), 679–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de la Torre-Luque, A; Essau, CA; Lara, E; Leal-Leturia, I; Borges, G. Childhood emotional dysregulation paths for suicide-related behaviour engagement in adolescence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2023, 32(12), 2581–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Wu, C.; Wang, J.; Sun, M. Autism Spectrum Disorder: Neurodevelopmental Risk Factors, Biological Mechanism, and Precision Therapy. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24(3), 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggieri, V. Autismo. Tratamiento farmacológico [Autism. Pharmacological treatment]; Medicina (B Aires): Spanish, Sep 2023; Volume 83, Suppl 4, pp. 46–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siafis, S.; Çıray, O.; Wu, H.; et al. Pharmacological and dietary-supplement treatments for autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Molecular Autism 2022, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedgchin, M; Trivedi, M; Daly, EJ; Melkote, R; Lane, R; Lim, P; Vitagliano, D; Blier, P; Fava, M; Liebowitz, M; Ravindran, A; Gaillard, R; Ameele, HVD; Preskorn, S; Manji, H; Hough, D; Drevets, WC; Singh, JB. Efficacy and Safety of Fixed-Dose Esketamine Nasal Spray Combined With a New Oral Antidepressant in Treatment-Resistant Depression: Results of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Active-Controlled Study (TRANSFORM-1). Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2019, 22(10), 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vasiliu, O. Esketamine for treatment-resistant depression: A review of clinical evidence (Review). Exp Ther Med 2023, 25(3), 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Anashkina, AA; Erlykina, EI. Molecular Mechanisms of Aberrant Neuroplasticity in Autism Spectrum Disorders (Review). Sovrem Tekhnologii Med.;Epub 2021, 13(1), 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sato, W; Uono, S; Kochiyama, T; Yoshimura, S; Sawada, R; Kubota, Y; Sakihama, M; Toichi, M. Structural Correlates of Reading the Mind in the Eyes in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Hum Neurosci 2017, 11, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fonagy, P; Luyten, P; Moulton-Perkins, A; Lee, YW; Warren, F; et al. Development and Validation of a Self-Report Measure of Mentalizing: The Reflective Functioning Questionnaire. PLOS ONE 2016, 11(7), e0158678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wajs, E; Aluisio, L; Holder, R; Daly, EJ; Lane, R; Lim, P; George, JE; Morrison, RL; Sanacora, G; Young, AH; Kasper, S; Sulaiman, AH; Li, CT; Paik, JW; Manji, H; Hough, D; Grunfeld, J; Jeon, HJ; Wilkinson, ST; Drevets, WC; Singh, JB. Esketamine Nasal Spray Plus Oral Antidepressant in Patients With Treatment-Resistant Depression: Assessment of Long-Term Safety in a Phase 3, Open-Label Study (SUSTAIN-2). J Clin Psychiatry 2020, 81(3), 19m12891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova, V; Daly, EJ; Trivedi, M; Cooper, K; Lane, R; Lim, P; Mazzucco, C; Hough, D; Thase, ME; Shelton, RC; Molero, P; Vieta, E; Bajbouj, M; Manji, H; Drevets, WC; Singh, JB. Efficacy and Safety of Flexibly Dosed Esketamine Nasal Spray Combined With a Newly Initiated Oral Antidepressant in Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Randomized Double-Blind Active-Controlled Study doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19020172. Epub 2019 May 21. Am J Psychiatry Erratum in: Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Aug 1;176(8):669. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.1768correction1. PMID: 31109201. 2019, 176(6), 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PATIENT 1 (G.) | PATIENT 2 (E.) | PATIENT 3 (A.) | |

| GENDER AND AGE | Female, 25y | Male, 20y | Female, 25y |

| JOB | Student Writer assistant |

Farm worker | Student |

| AUTISM SEVERITY | Level 2 | Level 2 | Level 1 |

| INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY | No (IQ 107) | No (IQ 137) | No (IQ 130) |

| FAMILIAR ANAMNESIS | Major depressive disorder (mother) Panic disorder (father) |

Bipolar Disorder (mother) | Negative |

| MEDICAL COMORBIDITIES | No | Sever obesity, hypertension | No |

| HOSPITALIZATIONS | Suicidal ideation (2021) | Suicidal attempt (2023) Suicidal ideation (2024) |

No |

| SUICIDAL ATTEMPTS | No | 1 (setting fire) | No |

| SELF-HARMING | Yes (cutting, cigarette burns) | No | No |

| DRUG USE | No | Alcohol (occasional) | No |

| ORAL PHARMACOTHERAPY | Sertraline 200 mg/day Aripiprazole 15 mg/day |

Venlafaxine 300 mg/day Lurasidone 74 mg/day |

Escitalopram 20 mg/day Methylphenidate 50 mg/day |

| ESKETAMINE POSOLOGY | 84 mg | 84 mg | 84 mg |

| ESKETAMINE DURATION | 6 months | 15 months (ongoing) | 9 months (ongoing) |

| HOSPITALIZATIONS DURING ESKETAMINE | No | No | No |

| SUICIDAL ATTEMPTS DURING ESKETAMINE | No | No | No |

| SELF-HARMING DURING ESKETAMINE | Yes (1 episode) | No | No |

| DOMAIN | SCALE | ABBREVIATION | SCORE |

| Depression | Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale | MADRS | 0-60 |

| Psychological pain | Psychache Scale | PS | 13-65 |

| Suicidality | Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale | C-SSRS | If present, assess “Ideation” subscale 1-5 |

| Social Cognition | Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test | RMET | 0-36 |

| Mentalization | Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (8th version) | RFQ8 | 1-7 |

| Quality of Life | Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire | Q-LES-Q | 0-100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).