Introduction

Prevalence of Major Depression in Borderline Personality Disorder

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is a serious mental illness affecting 1.35% of the population with an estimated annual healthcare-related and lost-productivity cost of €40 441 per patient [

1]. Nearly 84.5% of individuals with BPD suffer from one or more comorbid psychiatric disorders, with major depressive disorder (MDD) occurring with an estimated 71-83% prevalence [

2]. Symptoms of BPD include frequent alteration of self-image between devaluation and idealization, anxiety, irritability, depressed mood, and impulsive behavior that could potentially be self-destructive, such as excessive spending, sexual activity, or substance misuse [

3].

Patients with comorbid BPD and MDD have worse depressive symptoms, more functional impairment, delayed time to remission, and shorter time to relapse [

4]. The comorbidity of both diagnoses adds to the challenge of treating either condition; the current standard of care for the treatment of BPD is less effective when individuals have a comorbid MDD diagnosis [

4], and major depressive episodes tend to be resistant to treatment in individuals with BPD [

5]. Furthermore, the lifetime risk of suicide in BPD with comorbid MDD is increased by sixteen times more than in patients with MDD alone [

6]. Hence, there is a growing need for new treatment modalities to address both conditions simultaneously.

Current Standard of Care in BPD Treatment

The current standard of care for treating BPD includes psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, with psychotherapy being the first line of treatment [

7]. Psychotherapeutic interventions aim to mitigate the parasuicidal risk and enhance problem-solving behaviors. The main psychotherapeutic approaches used are dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) [

7,

8], mentalization-based treatment (MBT) [

9], transference-focused therapy (TFP) [

10], and schema therapy [

11].

On the other hand, there has been a shift from using pharmacological measures to treat BPD in recent years. In 2001, The American Psychiatric Association guidelines recommended the use of medications

“to treat state symptoms during periods of acute decompensation as well as trait vulnerabilities.” [

7] For example, the guidelines recommended using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or related antidepressants for treating affective dysregulation associated with BPD [

7]. However, the accumulation of recent evidence has not shown benefit from using these pharmacological interventions in treating BPD core symptoms, a possible reason behind the lack of any medication approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat the core symptoms of BPD [

8,

9]. This is also supported by the recent guidelines from the UK National Institute for Care and Excellence (NICE), which recommended the use of pharmacological interventions in BPD only in discrete severe comorbid disorders, such as major depression [

3,

10]. Hence, there is an imminent need for new pharmacological modalities that could address the core symptoms of BPD in addition to comorbid psychiatric illnesses [

4].

Treatment-Resistant Depression

Treatment-Resistant Depression (TRD) is a frequent comorbidity to BPD [

2]. Treatment-resistant depressive episodes can occur within the context of a major depressive illness or bipolar illness [

11,

12]. A common theme in the operational definition of TRD involves non-response to conventional medications, yet a consensus on the operational definition of TRD is still lacking. This lack of a consensus around the definition has limited the interpretability and generalizability of many clinical trials [

13,

14]. According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), TRD is defined as failure to respond to two or more antidepressant regimens despite adequate dose and duration and adherence to treatment [

13]. Several modalities have been proposed for the treatment of TRD, including extending the antidepressant trial, switching/combining antidepressant medications, augmentation with second-generation antipsychotics [

15], using ketamine or esketamine [

16,

17], using repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) [

18], electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) [

19], and vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) [

20]. A recent study found ketamine to be non-inferior to ECT in the treatment of non-psychotic TRD [

21].

Ketamine and Esketamine (Figure 1 [22])

Biochemical Profile

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic used in clinical practice since 1970 [

23]. It exists in nature as two enantiomers, esketamine (S-ketamine) and arketamine (R-ketamine). Racemic ketamine, the form most widely used in the treatment of TRD and pain [

24,

25], contains an equimolar mixture of both [

26].

Esketamine has more potency, a stronger antidepressant effect, and fewer neurocognitive effects than Arketamine [

27]. Esketamine has been approved for intravenous (IV) use in multiple European countries and China. The intranasal form is approved for clinical use in the United States and Canada [

28]. For the purpose of this study, we use “ketamine” in reference to racemic ketamine and “esketamine” in reference to the clinical preparation of pure S-ketamine.

Figure 1.

Ketamine Enantiomers. Racemic Ketamine is the combination of S-ketamine (Esketamine) and R-ketamine (Arketamine). Created in BioRender. ElSayed, M. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/c56l537.

Figure 1.

Ketamine Enantiomers. Racemic Ketamine is the combination of S-ketamine (Esketamine) and R-ketamine (Arketamine). Created in BioRender. ElSayed, M. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/c56l537.

Biological Effects

Ketamine’s biological effects are hypothesized to be the result of its N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonism on medial prefrontal cortical (mPFC) gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) interneurons [

29,

30]. In addition, ketamine increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels, which initiates a cascade of intermediates, resulting in enhanced neurogenesis in the hippocampus [

29,

30].

Antidepressant Effects

Esketamine [

31], but not racemic ketamine [

32], has been FDA-approved for the treatment of TRD in 2019 after multiple randomized trials showed its efficacy [

33,

34]. Limited evidence is available on whether esketamine has a better antidepressant effect than racemic ketamine. A systematic review and a meta-analysis by Bahji

et al. found ketamine to outperform esketamine in response and remission in the treatment of depression. Of note, the studies included in the meta-analysis did not have head-to-head trials [

35]. In addition, one randomized head-to-head non-inferiority trial concluded that esketamine is non-inferior to ketamine in regard to its antidepressant effects, confirming its comparative efficacy in treating TRD [

36].

Ketamine and Esketamine as a Potential Treatment for BPD with Comorbid TRD

Current research into the use of ketamine for borderline personality disorder (BPD) with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) remains in its early stages, with limited evidence available to guide clinical practice [

4,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Three studies have systematically examined the use of IV ketamine in treating BPD with TRD and yielded mixed results [

37,

38,

40]. Danayan and Chen reported improvement in depression and anxiety. Fineberg’s study, on the other hand, found no significant improvement. They, however, noted improvement in subjects’ socio-occupational functioning.

In addition to the previous studies, several case reports found a potential benefit from other forms of ketamine, including sublingual [

39], intranasal [

34,

42], and IV esketamine [

37,

40,

41], in treating BPD with comorbid TRD. Several cases had improvement in depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, impulsivity, and affective instability. One case had an opposite response, and the patient experienced an increase in impulsive and suicidal behavior [

41].

In this study, we conducted a retrospective chart review, and we present a series of cases with BPD with comorbid TRD treated with esketamine in a state psychiatric hospital in rural New Hampshire state.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

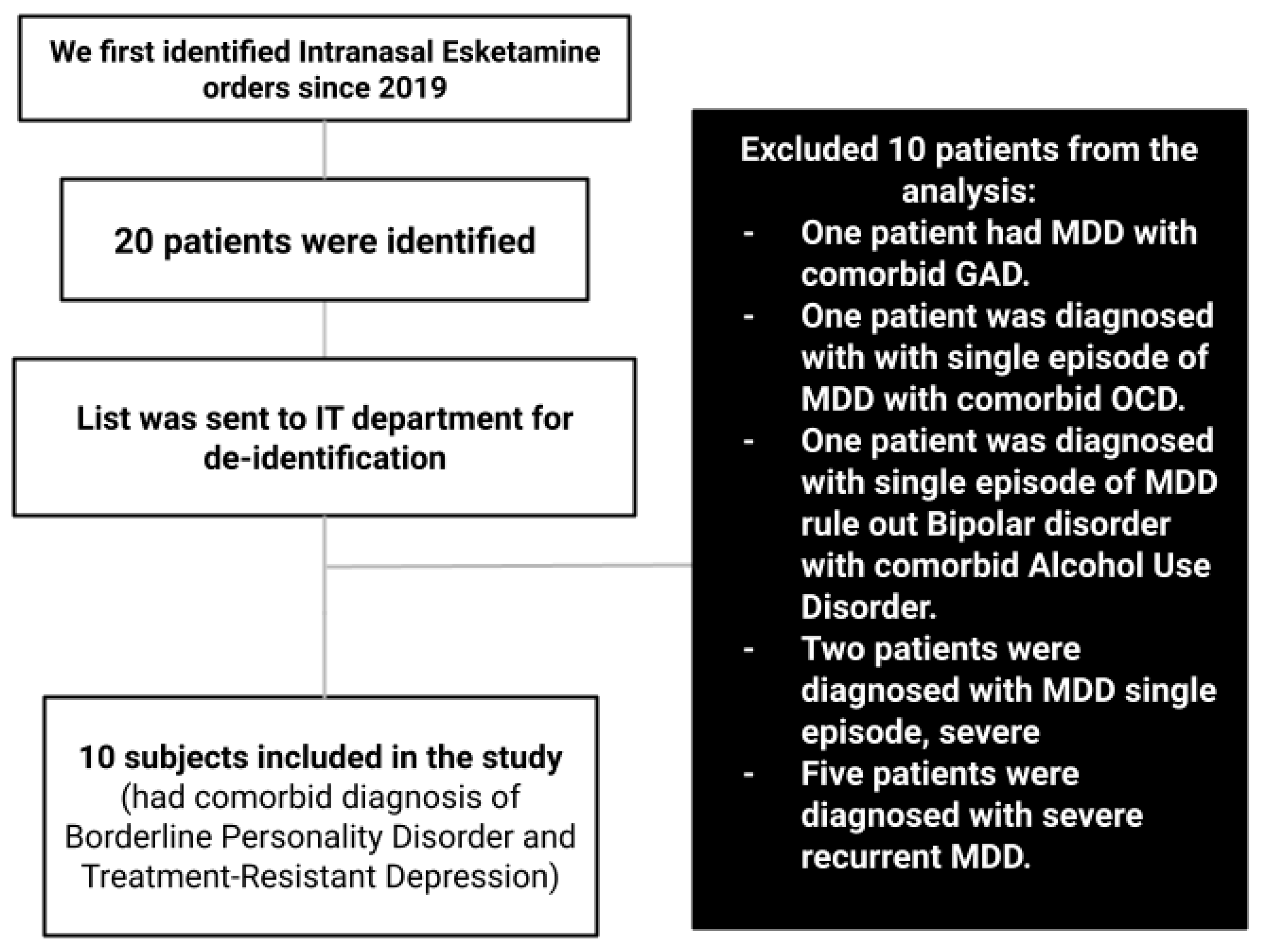

Our study is a retrospective chart review study conducted at the only involuntary state psychiatric hospital, New Hampshire Hospital (NHH), in the rural state of New Hampshire. At NHH, intranasal esketamine is the only available ketamine form for treating TRD. We aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes of patients with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) with comorbid treatment-resistant depression (TRD) who received intranasal esketamine treatment during their inpatient stay. We focused on changes in suicidality, homicidal ideations/behaviors, mood, and depression.

The chart review process included inpatients admitted to NHH, diagnosed with BPD and comorbid TRD, and received intranasal esketamine during their inpatient stay for treatment of their symptoms.

We first identified the potential candidate electronic health records (EHR) to be included in the study by examining all inpatient intranasal esketamine orders since the medication was approved for clinical use in 2019. The list of subjects who received the medication was then shared with NHH’s information technology (IT) department so that the data could be de-identified before analyzing it. The list of potential charts was further narrowed by excluding subjects who did not have the diagnoses of BPD and TRD. The de-identified data were reviewed by author HT and validated by co-author ME.

We collected data relevant to the following variables during the record review process: demographics, socioeconomic statuses, trauma histories, substance use histories, clinical record diagnoses, mood, suicidal ideations/behaviors, homicidal ideation, mood, length of hospitalization, and treatment-specific parameters, such as the number of sessions, the esketamine doses, and the in-hospital medication administration history. The demographics, trauma, substance use, and socioeconomic status variables were recorded in the psychiatric admission note.

While reviewing depression assessments, we were unable to find consistent, systematic depression score recordings before and after esketamine treatment. Hence, we used the patient provider's daily interval history and mental status examination (MSE). We reviewed providers’ daily MSE for mood, suicidal ideations/behaviors, and homicidal behavior. Most providers used the patient’s wording when they recorded the mood section in their notes.

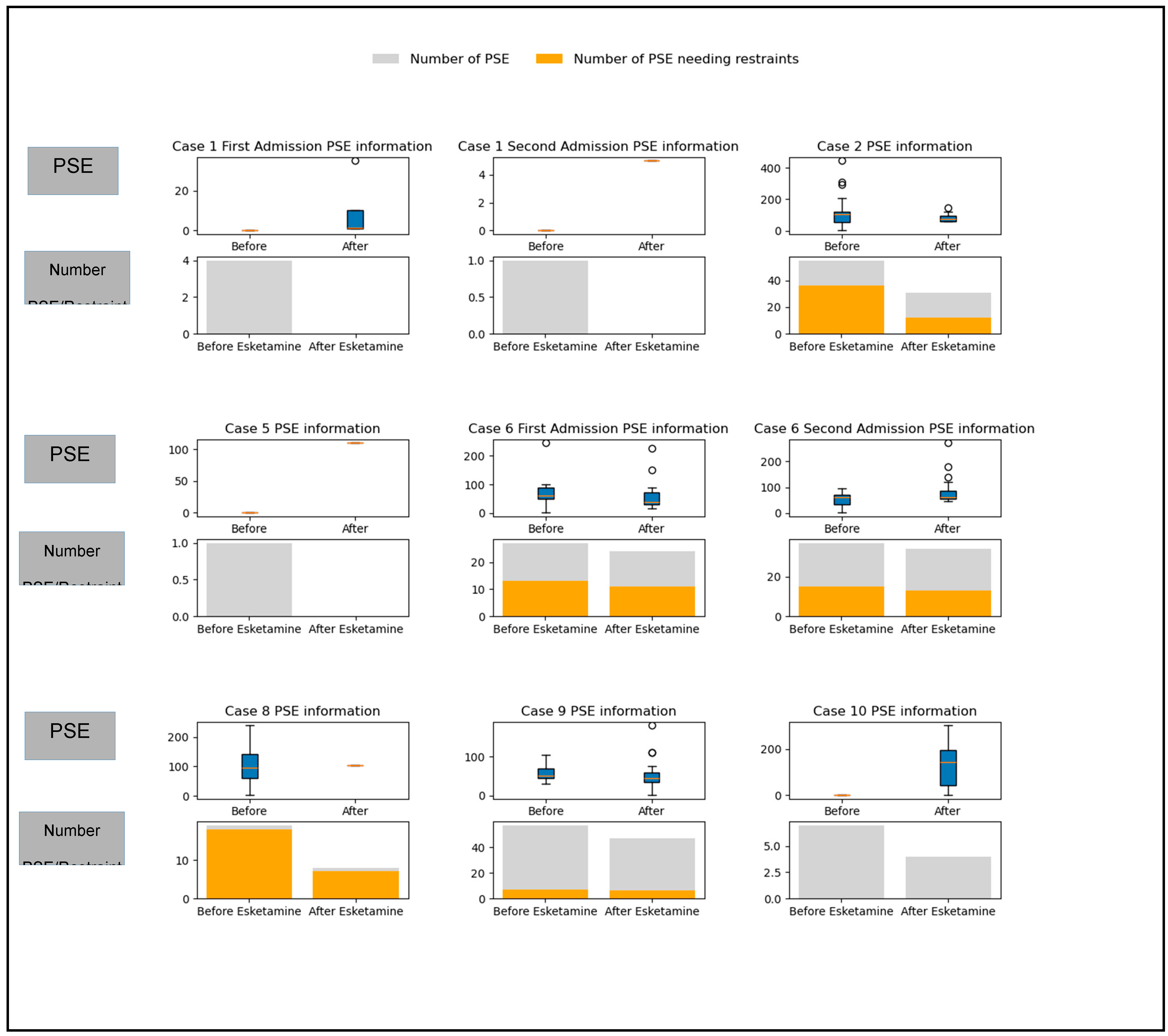

We also focused on measures of safety in an inpatient hospital setting. To assess the patient’s safety, the recurrence of self-harm behavior, and impulsivity, we used the personal safety emergency (PSE) parameters. PSE is defined by NHH policy as “a physical status or mental status and an act or pattern of behavior of a patient which, if not treated immediately, will result in serious harm to the patient or others.” In such conditions, the aim is to preserve the patient and surrounding safety, and measures such as mechanical restraint could be used to ensure that principle. The hospital policy defines mechanical restraint as “Any manual method, physical or mechanical device, material or equipment that immobilizes a patient or reduces the ability of a patient to move his or her arms, legs, head, or other body parts freely. Restraint does not include devices, such as orthopedically prescribed devices, surgical dressings or bandages, protective helmets, or other methods that involve the physical holding of a patient, if necessary, for the purpose of: i. Conducting routine physical examinations or tests; ii. Protecting the patient from falling out of bed; or iii. Permitting the patient to participate in activities without the risk of physical harm.” With each PSE, The hospital staff must record the following parameters: the duration of the incident and the use of any restrictive interventions, including mechanical restraints. We used the number of PSEs, the duration of PSEs, and the use of mechanical restraint as parameters reflecting the patient’s potential for self-harm and impulsivity before and after starting esketamine treatment.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes of interest were changes in suicidal ideations/behavior, homicidal ideations, and negative and positive mood states before and after treatment.

Statistical Analysis

In this study, descriptive statistics were used to describe the data obtained from the chart review. Data were anonymized prior to analysis to ensure confidentiality. Statistical analyses were conducted to summarize and present the key findings in an organized and interpretable manner.

Descriptive Statistics:

Continuous variables were summarized using measures of central tendency (mean, median) and variability (standard deviation, interquartile range). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Two patients were re-admitted and received esketamine in two of the admissions. To ensure consistency, we only included the first admission when each patient received esketamine for the first time. We included the second admission for subjects in the graph in

Figure 2.

Software:

All analyses were performed using Python (version 3.12.4) using the numpy, pandas, scipy, and matplotlib libraries.

Ethical Considerations

Our study was exempt from a full Institutional Review Board after the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, the NH State-appointed IRB, reviewed the protocol.

Flowchart 1.

The process of data collection and exclusion. MDD: Major Depressive Disorder. GAD: Generalized Anxiety Disorder. OCD: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.

Flowchart 1.

The process of data collection and exclusion. MDD: Major Depressive Disorder. GAD: Generalized Anxiety Disorder. OCD: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.

Results

Demographics

Ten patients were identified to have combined BPD and TRD since the approval of esketamine in 2019. The demographics of these patients can be found in

Table 1.

Esketamine Course and Doses

Inpatients with BPD and TRD received intranasal esketamine during their stay. Per the hospital protocol, all subjects self-administered the doses and were observed by a registered nurse (RN) for about two hours after the session.

Table 2 illustrates the course and doses of treatment for each case.

Changes in Mood, Suicidal, and Homicidal Ideations Before and After Treatment (Table 3)

Four patients reported improvement in their negative mood after receiving esketamine treatment. In addition, seven patients denied suicidal ideation after starting esketamine. One subject reported newly acquired vague homicidal ideations that were not present before esketamine treatment. However, changes in mood, suicidal, and homicidal ideations were not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Changes related to mood, suicidal, and homicidal symptoms. The negative mood had a range of feelings: “sad,” “depressed,” “anxious,” “angry,” “scared,” and/or “having a bad mood.” The positive mood had a range of feelings: “fair,” “good,” and “euthymic” mood states. The negative and positive values were analyzed independently. Hence, subjects reported negative and positive affects before and after the esketamine treatment (*). N is the number of cases, % is the percentage, and SD is the standard deviation. The affect, suicidal ideations, and homicidal ideations were reported in the daily provider mental health examination.

Table 3.

Changes related to mood, suicidal, and homicidal symptoms. The negative mood had a range of feelings: “sad,” “depressed,” “anxious,” “angry,” “scared,” and/or “having a bad mood.” The positive mood had a range of feelings: “fair,” “good,” and “euthymic” mood states. The negative and positive values were analyzed independently. Hence, subjects reported negative and positive affects before and after the esketamine treatment (*). N is the number of cases, % is the percentage, and SD is the standard deviation. The affect, suicidal ideations, and homicidal ideations were reported in the daily provider mental health examination.

| |

N (%) |

Percentage |

McNemar Test |

P-Value |

Degrees of Freedom |

| Before Esketamine Treatment |

After Esketamine Treatment |

| Negative Mood |

5 (50) |

4 (40) |

1 |

1 |

|

| Positive Mood |

3 (30) |

7 (70)* |

1 |

0.22 |

|

| |

|

|

|

Stuart_Maxwell Test Statistic |

|

|

| Suicidal Ideations |

denies SI |

0 |

7 (70) |

-4.79 |

1 |

6 |

| suicidal ideation only |

1 (10) |

0 |

|

|

|

| suicidal ideation with intent |

1 (10) |

0 |

|

|

|

| suicidal ideation with a plan |

1 (10) |

1 (10) |

|

|

|

| suicidal ideation with plan and intent |

5 (50) |

2 (20) |

|

|

|

| presented after a suicide attempt |

2 (20) |

0 |

|

|

|

| Homicidal Ideations |

no homicidal ideation |

10 (100) |

9 (90) |

-1.043 |

1 |

3 |

| Vague homicidal ideation |

|

1 (10) |

|

|

|

Table 4.

Changes in safety. This encompasses the frequency and duration of personal safety emergency (PSE) incidents the patient had during their admission, as well as the number of PSE incidents where mechanical restraint was warranted. Safety also encompasses the number of admissions the patient had at New Hampshire Hospital (NHH) after they received esketamine and until the data was analyzed for this manuscript (December 2024). SD is the standard deviation.

Table 4.

Changes in safety. This encompasses the frequency and duration of personal safety emergency (PSE) incidents the patient had during their admission, as well as the number of PSE incidents where mechanical restraint was warranted. Safety also encompasses the number of admissions the patient had at New Hampshire Hospital (NHH) after they received esketamine and until the data was analyzed for this manuscript (December 2024). SD is the standard deviation.

| |

Before Esketamine Treatment |

After Esketamine Treatment |

Wilcoxon signed-rank test statistic |

P-Value |

| Mean (SD) |

Median (25th Quartile/75th Quartile) |

Mean (SD) |

Median (25th Quartile/75th Quartile) |

| Number of inpatient admissions to NHH after receiving Esketamine treatment |

|

|

4.1 (6.54) |

0.5 |

|

|

| Number of PSE incidents |

7.4 (11.97) |

0 |

9.6 (15.6) |

2.5 |

11 |

0.611 |

| Number of PSE incidents requiring mechanical restraint |

3.6 (4.9) |

0 |

7.8 (13.4) |

0.5 |

3 |

0.22 |

| Duration of PSE incidents (minutes) |

81.45 (73.13) |

60 (44/107.25) |

65.04 (51.95) |

60 (35/75) |

11 |

0.612 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Changes in Safety (Table 4)

Safety could be interpreted by short-term (in-patient PSE incidents) and longer-term (recurrence of involuntary admission to state facility). Starting inpatient esketamine treatment was associated with an increase in the number of PSE incidents (the mean incident number increased from 3.6 to 7.8). However, the duration of PSE incidents decreased from a mean of 81.45 minutes to a mean of 65.04 minutes. This finding, however, did not reach statistical significance.

Table 5.

Additional medications trialed or used for augmentation per each subject. The medication regimen indicates medications used in conjunction with esketamine during admission.

Table 5.

Additional medications trialed or used for augmentation per each subject. The medication regimen indicates medications used in conjunction with esketamine during admission.

| Case 1 |

Case 6 |

| Medications in First Admission |

Changes in Second admission |

Medications in First Admission |

Changes in Second admission |

Bupropion Duloxetine Haloperidol Oxcarbazepine Pregabalin Quetiapine Vortioxetine Zolpidem |

|

Clozapine Diazepam Prazosin Topiramate Venlafaxine Baclofen |

|

| Case 2 |

Case 7 |

| Discontinued Medications |

Medication Regimen |

Medication Regimen |

|

Aripiprazole Clonidine Oxcarbazepine Buspirone Quetiapine Guanfacine |

Bupropion Duloxetine Lurasidone Prazosin Trazodone |

| Case 3 |

Case 8 |

| Medication Regimen |

Medication Regimen |

|

|

|

|

| Case 4 |

Case 9 |

| Medication Regimen |

Medication Regimen |

Duloxetine Gabapentin Mirtazapine Prazosin Quetiapine |

Clonazepam Clozapine Lithium Topiramate |

Venlafaxine Olanzapine Trazodone Sodium Valproate |

| Case 5 |

Case 10 |

| Medication Regimen |

Medication Regimen |

Quetiapine Vortioxetine Mirtazapine |

|

Figure 2.

The Personal Safety Emergency (PSE) information for each subject individually. For each subject, the upper half of the graph represents the box plot and outliers for the PSE duration before and after starting esketamine treatment. The lower half of the graph is a stacked bar chart that includes the number of PSE incidents (grey) and the number of PSE incidents that required mechanical restraints (orange) before and after starting esketamine sessions. The second admissions for cases 1 and 6 are included in the graphs below. Cases 3, 4, and 7 had no PSE events during their inpatient stay and were not included.

Figure 2.

The Personal Safety Emergency (PSE) information for each subject individually. For each subject, the upper half of the graph represents the box plot and outliers for the PSE duration before and after starting esketamine treatment. The lower half of the graph is a stacked bar chart that includes the number of PSE incidents (grey) and the number of PSE incidents that required mechanical restraints (orange) before and after starting esketamine sessions. The second admissions for cases 1 and 6 are included in the graphs below. Cases 3, 4, and 7 had no PSE events during their inpatient stay and were not included.

Medication Regimen During the Inpatient Stay

Table 5 lists the medications trialed or used for augmentation during inpatient treatment for each patient.

Discussion

Our study aimed to understand the potential role of esketamine in treating patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) with comorbid treatment-resistant depression (TRD) by reviewing inpatient records at a state hospital in rural NH state. This is the first systematic study to assess the potential role of intranasal esketamine in treating this patient population.

Our study showed an increase in positive mood states, a slight decrease in negative mood states, and a reduction in suicidal ideation/behavior in inpatients with BPD and comorbid TRD. While these findings were not statistically significant, they align with other IV ketamine trials.

In Danayan’s study [

38]

, repeated IV ketamine infusions significantly reduced depressive symptoms in patients with TRD and comorbid BPD, similar to patients without BPD. Both groups showed improved depression severity. In addition, ketamine reduced BPD symptoms to a degree the authors considered to be comparable to those seen in patients receiving Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT), the golden standard for treating borderline personality disorder [

42]

. Moreover, ketamine showed a positive effect on suicidal ideation for patients with comorbid BPD and MDD. In a second study [

40]

, IV ketamine had comparable efficacy in treating depressive symptoms in patients with MDD alone compared to MDD and BPD.

In this study, we used personal safety emergency (PSE) data, i.e., number, duration, and the use of mechanical restraint, to measure immediate and short-term safety. Although not statistically significant, we noticed an increase in the number of PSE incidents following esketamine treatment. However, we also noticed that the mean and median duration for these PSEs were shorter, which was also not statistically significant. This could be interpreted as a general increase in impulsivity (higher number of PSE incidents) associated with esketamine treatment. At the same time, this impulsivity is associated with less safety risk (shorter duration of PSE incidents). Vanicek

et al. [

41] reported a similar increase in impulsivity in a patient with BPD and recurrent MDD after receiving IV esketamine. We, nevertheless, did not notice an associated increase in suicidal ideations/behavior.

While our results in this retrospective record review study did not achieve statistical significance, it is crucial to highlight that the sample size may have limited the study's power. Furthermore, this study reviewed charts of patients who have severe symptoms with frequent and prolonged inpatient involuntary psychiatric admissions because of their illness. Such factors could have reduced the likelihood of detecting more subtle or nuanced effects. Therefore, further research with larger sample sizes and more robust designs is essential to understand the potential impact of the investigated variables. Such studies would enhance statistical power and may reveal effects that were not detectable in the current analysis.

Conclusion

This study is a retrospective case series reviewing the effects of intranasal esketamine on patients with BPD and TRD in a state psychiatric hospital setting. We found a greater increase in positive mood than we did a decrease in negative mood. We also found a decrease in suicidal ideations/behavior. If replicated in larger samples, this finding could suggest that psychotherapeutic interventions that rely on generating positive reinforcing experiences, such as Behavioral Activation and Problem Solving Therapy, may be more efficacious after esketamine treatment in this population.

Limitations

This study is subject to limitations inherent in its retrospective design. The reliance on chart data may introduce bias due to incomplete or inconsistent documentation. The lack of a control group or randomization limits the ability to draw definitive conclusions about the specific effects of esketamine in patients with BPD. Additionally, the small sample size and variability in treatment regimens may affect the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the unstandardized nature of clinical work, such as variations in the timing or providers conducting mental status examinations, reduces the replicability of these findings.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this retrospective chart review study was financed under contract with the State of New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, with funds provided in part by the state and/or such other funding sources as were available or required, e.g., the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors would also like to thank New Hampshire Hospital’s administration, Ms. Mary Galatis from the NHH pharmacy, and Ms. Melissa Cresta from the NHH IT department for their help with data extraction and de-identification.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

No financial conflicts of interest related to this study. The preparation of this retrospective chart review study was financed under contract with the State of New Hampshire, Department of Health and Human Services, with funds provided in part by the State of New Hampshire and/or such other funding sources as were available or required e.g. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. However, the institution did not appropriate any specific funding for this research.

Author Contributions

Dr. Tramontano helped with data collection, preparation of the IRB proposal, and manuscript writing. Dr. ElSayed helped validate the collected data, mentored the IRB proposal, analyzed the data, and assisted with manuscript writing. Dr. Fetter worked with the hospital pharmacy and administration to access data and assisted with manuscript writing.

References

- Hastrup LH, Jennum P, Ibsen R, Kjellberg J, Simonsen E. Societal costs of Borderline Personality Disorders: a matched-controlled nationwide study of patients and spouses. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019 Nov;140(5):458–67. [CrossRef]

- Biskin RS, Paris J. Comorbidities in Borderline Personality Disorder. Psychiatr Times. 2013 Jan;30(1):20–5.

- Leichsenring F, Heim N, Leweke F, Spitzer C, Steinert C, Kernberg OF. Borderline Personality Disorder: A Review. JAMA. 2023 Feb 28;329(8):670–9. [CrossRef]

- Frontiers | Depression with comorbid borderline personality disorder - could ketamine be a treatment catalyst? [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 24]. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1398859/full. [CrossRef]

- Ceresa A, Esposito CM, Buoli M. How does borderline personality disorder affect management and treatment response of patients with major depressive disorder? A comprehensive review. J Affect Disord. 2021 Feb 15;281:581–9. [CrossRef]

- Kelly TM, Soloff PH, Lynch KG, Haas GL, Mann JJ. Recent Life Events, Social Adjustment, and Suicide Attempts in Patients with Major Depression and Borderline Personality Disorder. J Personal Disord. 2000 Dec;14(4):316–26. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2001 Oct;158(10 Suppl):1–52.

- Gartlehner G, Crotty K, Kennedy S, Edlund MJ, Ali R, Siddiqui M, et al. Pharmacological Treatments for Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. CNS Drugs. 2021 Oct 1;35(10):1053–67. [CrossRef]

- Stoffers-Winterling JM, Storebøa OJ, Ribeiro JP, Kongerslev MT, Völlm BA, Mattivi JT, et al. Pharmacological interventions for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Dec 24];2022(11). Available from: https://www.readcube.com/articles/10.1002%2F14651858.cd012956.pub2. [CrossRef]

- Overview | Borderline personality disorder: recognition and management | Guidance | NICE [Internet]. NICE; 2009 [cited 2024 Dec 24]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg78.

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Jan;163(1):28–40. [CrossRef]

- Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, Marangell LB, Zhang H, Wisniewski SR, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Feb;163(2):217–24. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre RS, Alsuwaidan M, Baune BT, Berk M, Demyttenaere K, Goldberg JF, et al. Treatment-resistant depression: definition, prevalence, detection, management, and investigational interventions. World Psychiatry. 2023 Oct;22(3):394–412. [CrossRef]

- Gaynes BN, Lux L, Gartlehner G, Asher G, Forman-Hoffman V, Green J, et al. Defining treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety. 2020 Feb;37(2):134–45. [CrossRef]

- Gobbi G, Ghabrash MF, Nuñez N, Tabaka J, Di Sante J, Saint-Laurent M, et al. Antidepressant combination versus antidepressants plus second-generation antipsychotic augmentation in treatment-resistant unipolar depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018 Jan;33(1):34–43. [CrossRef]

- Alnefeesi Y, Chen-Li D, Krane E, Jawad MY, Rodrigues NB, Ceban F, et al. Real-world effectiveness of ketamine in treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review & meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2022 Jul;151:693–709. [CrossRef]

- Sapkota A, Khurshid H, Qureshi IA, Jahan N, Went TR, Sultan W, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Intranasal Esketamine in Treatment-Resistant Depression in Adults: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2021 Aug;13(8):e17352. [CrossRef]

- Vida RG, Sághy E, Bella R, Kovács S, Erdősi D, Józwiak-Hagymásy J, et al. Efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) adjunctive therapy for major depressive disorder (MDD) after two antidepressant treatment failures: meta-analysis of randomized sham-controlled trials. BMC Psychiatry. 2023 Jul 27;23(1):545. [CrossRef]

- Nygren A, Reutfors J, Brandt L, Bodén R, Nordenskjöld A, Tiger M. Response to electroconvulsive therapy in treatment-resistant depression: nationwide observational follow-up study. BJPsych Open. 2023 Feb 14;9(2):e35. [CrossRef]

- Müller HHO, Moeller S, Lücke C, Lam AP, Braun N, Philipsen A. Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) and Other Augmentation Strategies for Therapy-Resistant Depression (TRD): Review of the Evidence and Clinical Advice for Use. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:239. [CrossRef]

- Anand A, Mathew SJ, Sanacora G, Murrough JW, Goes FS, Altinay M, et al. Ketamine versus ECT for Nonpsychotic Treatment-Resistant Major Depression. N Engl J Med. 2023 Jun 22;388(25):2315–25. [CrossRef]

- BioRender [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 25]. Available from: https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/671002b2f6f3b71f3a59a9d4.

- Tyler MW, Yourish HB, Ionescu DF, Haggarty SJ. Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Ketamine. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017 Jun 21;8(6):1122–34. [CrossRef]

- Swainson J, McGirr A, Blier P, Brietzke E, Richard-Devantoy S, Ravindran N, et al. The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Task Force Recommendations for the Use of Racemic Ketamine in Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: Recommandations Du Groupe De Travail Du Réseau Canadien Pour Les Traitements De L’humeur Et De L’anxiété (Canmat) Concernant L’utilisation De La Kétamine Racémique Chez Les Adultes Souffrant De Trouble Dépressif Majeur. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. 2021 Feb;66(2):113–25. [CrossRef]

- Brinck EC, Tiippana E, Heesen M, Bell RF, Straube S, Moore RA, et al. Perioperative intravenous ketamine for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Dec 20;12(12):CD012033. [CrossRef]

- Muller J, Pentyala S, Dilger J, Pentyala S. Ketamine enantiomers in the rapid and sustained antidepressant effects. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016 Jun;6(3):185–92. [CrossRef]

- Kawczak P, Feszak I, Bączek T. Ketamine, Esketamine, and Arketamine: Their Mechanisms of Action and Applications in the Treatment of Depression and Alleviation of Depressive Symptoms. Biomedicines. 2024 Oct 9;12(10):2283. [CrossRef]

- Mion G, Himmelseher S. Esketamine: Less Drowsiness, More Analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2024 Jul 1;139(1):78–91. [CrossRef]

- Zanos P, Gould TD. Mechanisms of Ketamine Action as an Antidepressant. Mol Psychiatry. 2018 Apr;23(4):801–11. [CrossRef]

- Kim JW, Suzuki K, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. Ketamine: Mechanisms and Relevance to Treatment of Depression. Annu Rev Med. 2024 Jan 29;75:129–43. [CrossRef]

- Commissioner O of the. FDA. FDA; 2020 [cited 2024 Dec 25]. FDA approves new nasal spray medication for treatment-resistant depression; available only at a certified doctor’s office or clinic. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-nasal-spray-medication-treatment-resistant-depression-available-only-certified.

- Research C for DE and. FDA warns patients and health care providers about potential risks associated with compounded ketamine products, including oral formulations, for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. FDA [Internet]. 2023 Oct 10 [cited 2024 Dec 25]; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/fda-warns-patients-and-health-care-providers-about-potential-risks-associated-compounded-ketamine.

- Popova V, Daly EJ, Trivedi M, Cooper K, Lane R, Lim P, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Flexibly Dosed Esketamine Nasal Spray Combined With a Newly Initiated Oral Antidepressant in Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Randomized Double-Blind Active-Controlled Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Jun 1;176(6):428–38. [CrossRef]

- Daly EJ, Trivedi MH, Janik A, Li H, Zhang Y, Li X, et al. Efficacy of Esketamine Nasal Spray Plus Oral Antidepressant Treatment for Relapse Prevention in Patients With Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Sep 1;76(9):893–903. [CrossRef]

- Bahji A, Vazquez GH, Zarate CA. Comparative efficacy of racemic ketamine and esketamine for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021 Jan 1;278:542–55. [CrossRef]

- Correia-Melo FS, Leal GC, Vieira F, Jesus-Nunes AP, Mello RP, Magnavita G, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive therapy using esketamine or racemic ketamine for adult treatment-resistant depression: A randomized, double-blind, non-inferiority study. J Affect Disord. 2020 Mar 1;264:527–34. [CrossRef]

- Fineberg SK, Choi EY, Shapiro-Thompson R, Dhaliwal K, Neustadter E, Sakheim M, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of ketamine in Borderline Personality Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023 Jun;48(7):991–9. [CrossRef]

- Danayan K, Chisamore N, Rodrigues NB, Vincenzo JDD, Meshkat S, Doyle Z, et al. Real world effectiveness of repeated ketamine infusions for treatment-resistant depression with comorbid borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2023 May;323:115133. [CrossRef]

- Liester M, Wilkenson R, Patterson B, Liang B. Very Low-Dose Sublingual Ketamine for Borderline Personality Disorder and Treatment-Resistant Depression. Cureus. 2024 Apr;16(4):e57654. [CrossRef]

- Chen KS, Dwivedi Y, Shelton RC. The effect of IV ketamine in patients with major depressive disorder and elevated features of borderline personality disorder. J Affect Disord. 2022 Oct 15;315:13–6. [CrossRef]

- Vanicek T, Unterholzner J, Lanzenberger R, Naderi-Heiden A, Kasper S, Praschak-Rieder N. Intravenous esketamine leads to an increase in impulsive and suicidal behaviour in a patient with recurrent major depression and borderline personality disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry Off J World Fed Soc Biol Psychiatry. 2022 Nov;23(9):715–8. [CrossRef]

- Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: a randomized clinical trial and component analysis - PubMed [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 30]. Available from: https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.dartmouth.idm.oclc.org/25806661/.

- Neethu K, Puneet K Soni, Ajay Parsaik, and Aqeel Hashmi. “‘Esketamine’ in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Look Beyond Suicidality.” Cureus 14, no. 4 (2022): e24632. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).