Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

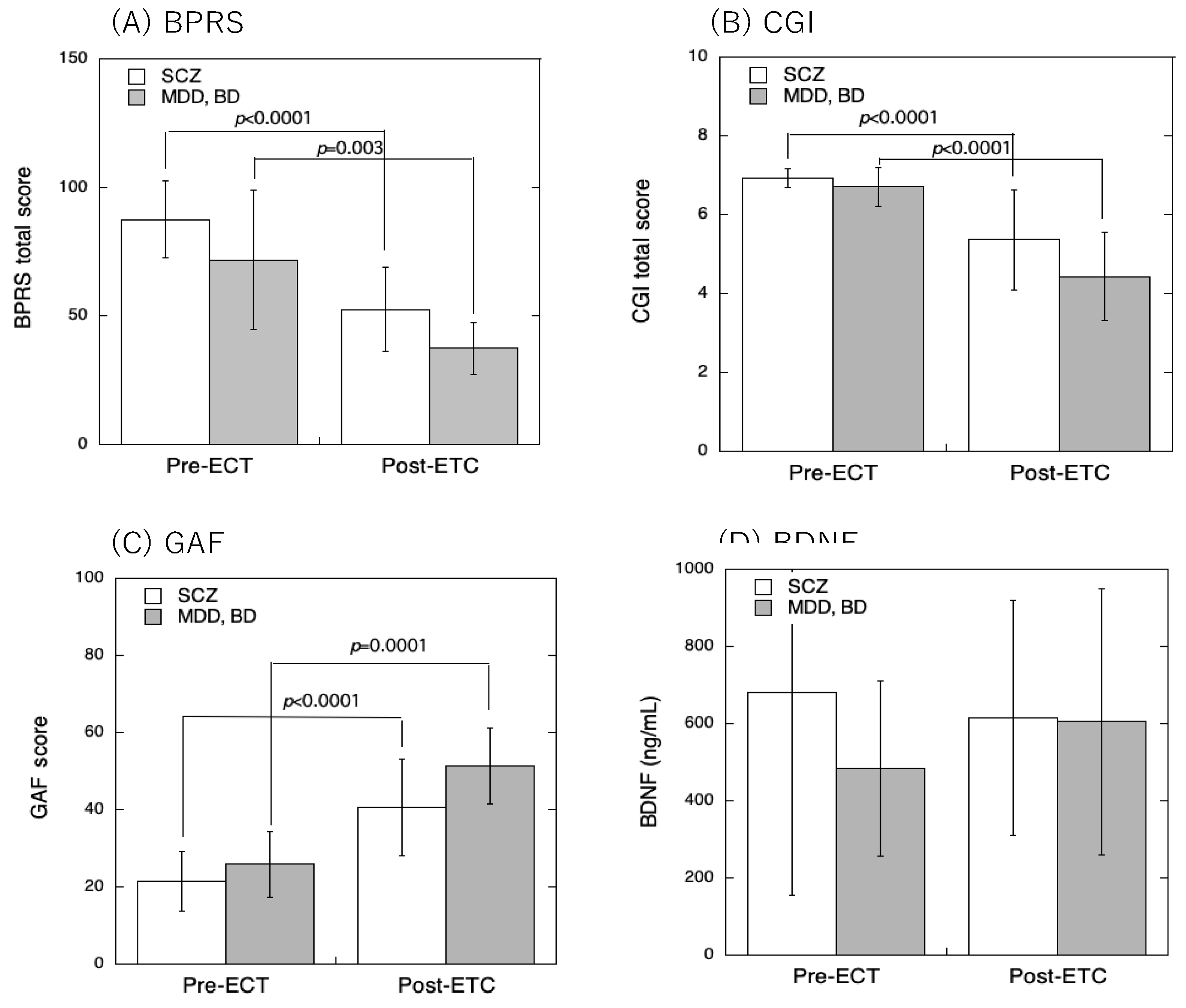

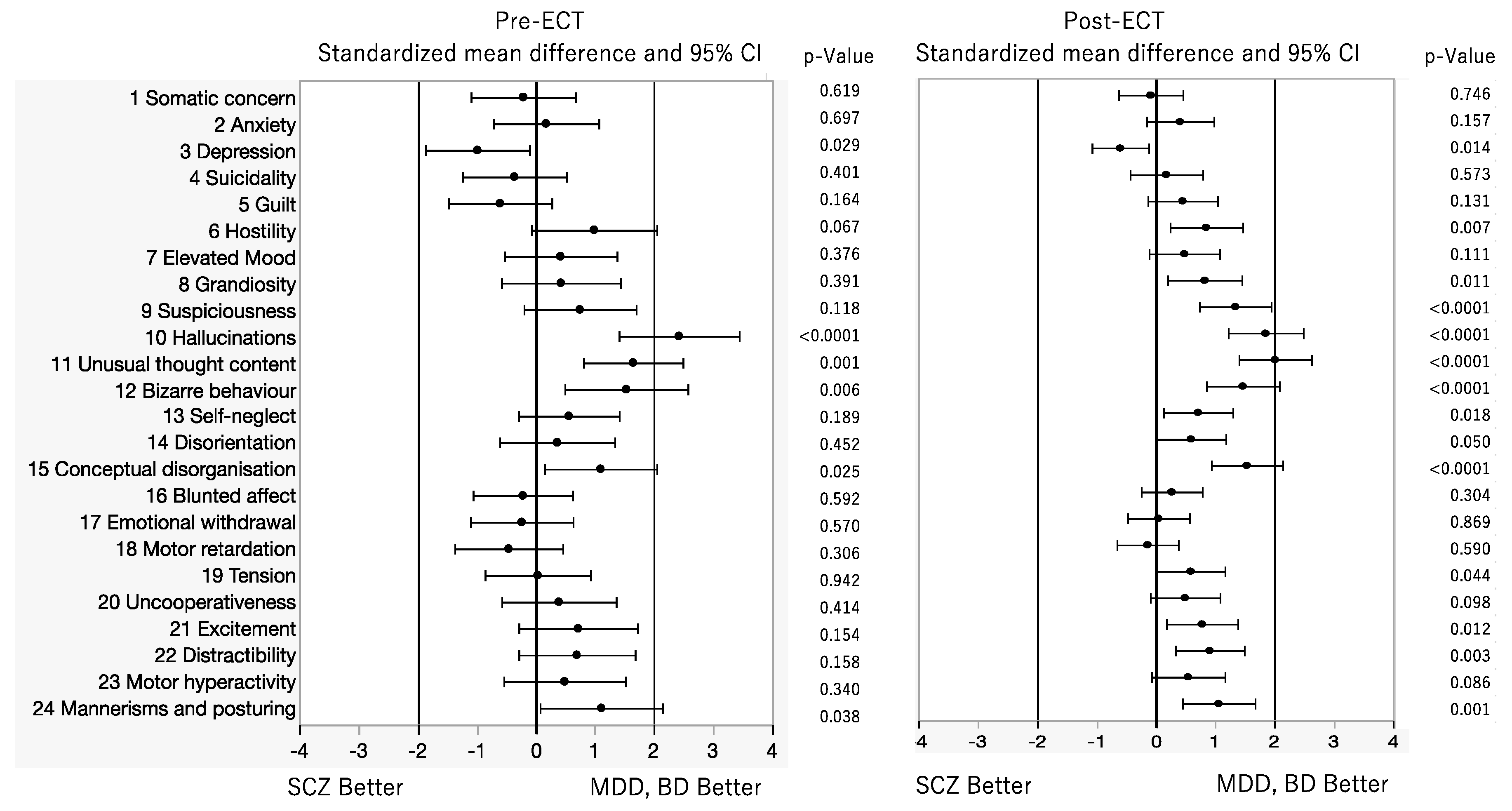

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trifu S, Sevcenco A, Stănescu M, Drăgoi AM, Cristea MB. Efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy as a potential first-choice treatment in treatment-resistant depression (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2021, 22, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermida AP, Glass OM, Shafi H, McDonald WM. Electroconvulsive Therapy in Depression: Current Practice and Future Direction. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2018, 41, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li M, Yao X, Sun L, Zhao L, Xu W, Zhao H, Zhao F, Zou X, Cheng Z, Li B, Yang W, Cui R. Effects of Electroconvulsive Therapy on Depression and Its Potential Mechanism. Front Psychol. 2020, 11, 80.

- Stippl A, Kirkgöze FN, Bajbouj M, Grimm S. Differential Effects of Electroconvulsive Therapy in the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. Neuropsychobiology. 2020, 79, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutz, J. Brain stimulation treatment for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2023, 25, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljubic N, Ueberberg B, Grunze H, Assion HJ. Treatment of bipolar disorders in older adults: a review. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2021, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair DJ, Zhao S, Qi F, Nyakyoma K, Kwong JS, Adams CE. Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019, 3, CD011847. [PubMed]

- Grover S, Sahoo S, Rabha A, Koirala R. ECT in schizophrenia: a review of the evidence. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2019, 31, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali SA, Mathur N, Malhotra AK, Braga RJ. Electroconvulsive Therapy and Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. Mol Neuropsychiatry 2019, 5, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ousdal OT, Argyelan M, Narr KL, Abbott C, Wade B, Vandenbulcke M, Urretavizcaya M, Tendolkar I, Takamiya A, Stek ML, Soriano-Mas C, Redlich R, Paulson OB, Oudega ML, Opel N, Nordanskog P, Kishimoto T, Kampe R, Jorgensen A, Hanson LG, Hamilton JP, Espinoza R, Emsell L, van Eijndhoven P, Dols A, Dannlowski U, Cardoner N, Bouckaert F, Anand A, Bartsch H, Kessler U, Oedegaard KJ, Dale AM, Oltedal L; GEMRIC. Brain Changes Induced by Electroconvulsive Therapy Are Broadly Distributed. Biol Psychiatry. 2020, 87, 451–461. [PubMed]

- Joshi SH, Espinoza RT, Pirnia T, Shi J, Wang Y, Ayers B, Leaver A, Woods RP, Narr KL. Structural Plasticity of the Hippocampus and Amygdala Induced by Electroconvulsive Therapy in Major Depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016, 79, 282–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takamiya A, Plitman E, Chung JK, Chakravarty M, Graff-Guerrero A, Mimura M, Kishimoto T. Acute and long-term effects of electroconvulsive therapy on human dentate gyrus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019, 44, 1805–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomann PA, Wolf RC, Nolte HM, Hirjak D, Hofer S, Seidl U, Depping MS, Stieltjes B, Maier-Hein K, Sambataro F, Wüstenberg T. Neuromodulation in response to electroconvulsive therapy in schizophrenia and major depression. Brain Stimul. 2017, 10, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang Y, Xia M, Li X, Tang Y, Li C, Huang H, Dong D, Jiang S, Wang J, Xu J, Luo C, Yao D. Insular changes induced by electroconvulsive therapy response to symptom improvements in schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019, 89, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan X, Zhang H, Dong Z, Chen J, Liu F, Zhao J, Zhang H, Guo W. Increased subcortical region volume induced by electroconvulsive therapy in patients with schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021, 271, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawashima H, Yamasaki S, Kubota M, Hazama M, Fushimi Y, Miyata J, Murai T, Suwa T. Commonalities and differences in ECT-induced gray matter volume change between depression and schizophrenia. Neuroimage Clin. 2023, 38, 103429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida T, Nakamura Y, Tanaka SC, Mitsuyama Y, Yokoyama S, Shinzato H, Itai E, Okada G, Kobayashi Y, Kawashima T, Miyata J, Yoshihara Y, Takahashi H, Morita S, Kawakami S, Abe O, Okada N, Kunimatsu A, Yamashita A, Yamashita O, Imamizu H, Morimoto J, Okamoto Y, Murai T, Kasai K, Kawato M, Koike S. Aberrant Large-Scale Network Interactions Across Psychiatric Disorders Revealed by Large-Sample Multi-Site Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Datasets. Schizophr Bull. Online ahead of print. 2023, 9, sbad022. [PubMed]

- Park SC, Jang EY, Kim D, Jun TY, Lee MS, Kim JM, Kim JB, Jo SJ, Park YC. Dimensional approach to symptom factors of major depressive disorder in Koreans, using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: the Clinical Research Center for Depression of South Korea study. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2015, 31, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanello A, Berthoud L, Ventura J, Merlo MC. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (version 4.0) factorial structure and its sensitivity in the treatment of outpatients with unipolar depression. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 210, 626–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dazzi F, Shafer A, Lauriola M. Meta-analysis of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale - Expanded (BPRS-E) structure and arguments for a new version. J. Psychiatr Res. 2016, 81, 140–151. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li H, Cui L, Li J, Liu Y, Chen Y. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of neuromodulation procedures in the treatment of treatment-resistant depression: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2021, 287, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffioletti E, Carvalho Silva R, Bortolomasi M, Baune BT, Gennarelli M, Minelli A. Molecular Biomarkers of Electroconvulsive Therapy Effects and Clinical Response: Understanding the Present to Shape the Future. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiknes KA, Jarosh-von Schweder L, Høie B. Contemporary use and practice of electroconvulsive therapy worldwide. Brain Behav. 2012, 2, 283–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizoguchi Y, Monji A, Nabekura J. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces long-lasting Ca2+-activated K+ currents in rat visual cortex neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2002, 16, 1417–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizoguchi Y, Monji A, Kato T, Seki Y, Gotoh L, Horikawa H, Suzuki SO, Iwaki T, Yonaha M, Hashioka S, Kanba S. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces sustained elevation of intracellular Ca2+ in rodent microglia. J Immunol. 2009, 183, 7778–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizoguchi Y, Kato TA, Seki Y, Ohgidani M, Sagata N, Horikawa H, Yamauchi Y, Sato-Kasai M, Hayakawa K, Inoue R, Kanba S, Monji A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) induces sustained intracellular Ca2+ elevation through the up-regulation of surface transient receptor potential 3 (TRPC3) channels in rodent microglia. J Biol Chem. 2014, 289, 18549–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha RB, Dondossola ER, Grande AJ, Colonetti T, Ceretta LB, Passos IC, Quevedo J, da Rosa MI. Increased BDNF levels after electroconvulsive therapy in patients with major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis study. J Psychiatr Res. 2016, 83, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meshkat S, Alnefeesi Y, Jawad MY, D Di Vincenzo J, B Rodrigues N, Ceban F, Mw Lui L, McIntyre RS, Rosenblat JD. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) as a biomarker of treatment response in patients with Treatment Resistant Depression (TRD): A systematic review & meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 317, 114857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li J, Zhang X, Tang X, Xiao W, Ye F, Sha W, Jia Q. Neurotrophic factor changes are essential for predict electroconvulsive therapy outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2020, 218, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbas I, Balaban OD. Changes in serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor with electroconvulsive therapy and pharmacotherapy and its clinical correlates in male schizophrenia patients. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2022, 34, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizoguchi Y, Ishibashi H, Nabekura J. The action of BDNF on GABA(A) currents changes from potentiating to suppressing during maturation of rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2003, 548, 703–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessels JM, Agarwal RK, Somani A, Verschoor CP, Agarwal SK, Foster WG. Factors affecting stability of plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 20232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghit A, Assal D, Al-Shami AS, Hussein DEE. GABAA receptors: structure, function, pharmacology, and related disorders. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mizoguchi Y, Kato TA, Horikawa H, Monji A. Microglial intracellular Ca (2+) signaling as a target of antipsychotic actions for the treatment of schizophrenia. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014, 8, 370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ohto A, Mizoguchi Y, Imamura Y, Kojima N, Yamada S, Monji A. No association of both serum pro-brain-derived neurotrophic factor (pro BDNF) and BDNF concentrations with depressive state in community-dwelling elderly people. Psychogeriatrics. 2021, 21, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa S, Cuthill IC. Effect size, confidence interval, and statistical significance: a practical guide for biologists. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2007, 82, 591–605. [PubMed]

| Patients | No | Age | Sex | Diagnosis | Diagnosis (F-code) |

On set age(y) | Illness Period until ECT(y) | Number of hospitalizations | Number of acute ECT treatments | Number of continua-tion of ECT | Number of maintenance ECT | Concomitant psychotropics | Disorganization responses to ECT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC group | before | after | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 27 | M | SC | SC(F200) | 20 | 7 | 2 | 12 | - | - | HPD9mg, Que400mg | HPD3mg, Ola20mg | - |

| 2 | 3 | 26 | M | SC | SC(F209) | 18 | 8 | 2 | 15 | 18 | 10 | Ola20mg, HPD9mg | Ola20mg, Lam200mg, LPZ50mg | - |

| 3 | 4 | 64 | M | SC | SC(F202) | 28 | 36 | 5 | 11 | 8 | - | Zot75mg | Zot75mg | - |

| 4 | 5 | 32 | M | SC | SC(F209) | 25 | 7 | 2 | 12 | 25 | 2 | Ris12mg, Que200mg | Ris10mg, HPD4.5mg | - |

| 5 | 7 | 19 | M | SC | SC(F209) | 15 | 7 | 4 | 12 | - | - | Clo600mg | Clo550mg | |

| 6 | 8 | 30 | M | SC | SC(F209) | 24 | 6 | 6 | 27 | 10 | - | Zot150㎎,HPDinj5mg | Ola20mg, Zot150㎎、HPDinj5mg | Frequent epiletic wave, cognitive function decline. |

| 7 | 11 | 44 | M | SC | SC(F209) | 16 | 28 | 17 | 12 | - | - | Ris12mg, Ase20mg | Ris12mg, Ase20mg | First ECT started in 2011 |

| 8 | 12 | 45 | F | SC | SC(F209) | 22 | 23 | 45 | 19 | 17 | - | Ola5mg, Ris1mg | Ola20mg, | |

| 9 | 23 | 45 | M | SC | SC(F209) | 18 | 17 | 18 | 28 | - | - | Clo400mg, Lam300mg | Clo400mg, Lam300mg | Memory impairment present. |

| 10 | 26 | 64 | M | SC | SC(F202) | 30 | 34 | 2 | 12 | 5 | 4 | Ase15mg, CPZ100mg | Ase15mg, CPZ100mg | |

| 11 | 28 | 69 | F | SC | SC(F209) | 31 | 38 | 11 | 12 | - | - | Olz20mg | Olz15mg | Slowing of brain waves on EEG |

| 12 | 29 | 47 | F | SC | SC(F239) | 47 | 0 | 1 | 15 | - | - | Que300mg | Que750mg, Pal3mg | |

| 13 | 31 | 50 | M | SC | SC(F209) | 19 | 31 | 13 | 15 | - | - | Clo500mg | Clo500mg | Slowing of brain waves on EEG |

| 14 | 9 | 20 | F | SC | SC(F209) | 19 | 1 | 11 | 13 | 13 | - | Ola5mg | Ola5mg, HPDinj20mg | Elevated BDNF levels due to hemolysis |

| 15 | 16 | 38 | F | SC | SC(F209) | 23 | 15 | 8 | 16 | - | - | CPZ50mg, Zot50mg | CPZ150mg | Slowing of brain waves on EEG Elevated BDNF levels due to hemolysis |

| 16 | 20 | 52 | F | SC | SC(F209) | 19 | 33 | 5 | 23 | - | - | Ola6.25mg, Ris2mg | Ola20mg | Elevated BDNF levels due to hemolysis |

| MDD+BD group | ||||||||||||||

| 17 | 6 | 61 | M | MDD+BD | BD(F314) | 44 | 47 | 6 | 15 | 8 | 6 | Mir30mg | Lam100mg | |

| 18 | 10 | 70 | F | MDD+BD | MDD(F329) | 52 | 18 | 7 | 7 | - | - | Ola5mg, Mir45mg | Ola5mg, Mir30mg | |

| 19 | 13 | 57 | M | MDD+BD | BD(F319) | 39 | 18 | 2 | 26 | 8 | - | Mil50mg | ||

| 20 | 15 | 68 | F | MDD+BD | MDD(F329) | 67 | 1 | 3 | 12 | 5 | 5 | Esc20mg, Ris8mg,Ven225mg | Esc20mg, Que12.5mg | |

| 21 | 17 | 61 | F | MDD+BD | MDD(F329) | 60 | 1 | 3 | 13 | 8 | - | Mir30mg, Ola20mg | Mir30mg, Ola20mg | Memory impairment present. |

| 22 | 21 | 70 | M | MDD+BD | BD(F315) | 69 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 8 | - | Esc20mg, Mir45mg, Ari3mg | - | |

| 23 | 24 | 63 | F | MDD+BD | BD(F319) | 50 | 13 | 3 | 10 | 12 | - | VPA 800mg, Que112.5mg |

VPA 600mg, Que112.5mg |

|

| 24 | 30 | 67 | F | SC | MDD(F323) | 66 | 1 | 1 | 9 | - | - | Ris1mg, Esc20mg | Esc20mg | |

| Excluded group | ||||||||||||||

| 25 | 2 | 68 | F | BD(F319) | 7 | Ari3mg | Discontinued due to liver dysfunction and fever |

|||||||

| 26 | 14 | 57 | F | SSD(F459) | 2 | Que125mg, Mir15mg | Discontinued due to eye pain and discomfort in the mouth |

|||||||

| 27 | 19 | 75 | F | SC(F209) | 2 | Ris2mg, LPZ25mg | Interrupted due to bradycardia and cardiac arrest |

|||||||

| Diagnosis | SC | MDD+BD | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 43.4±16.2 | 64.2±5.1 | 0.0035* |

| Sex (M%) | 58.8 | 42.8 | |

| On set age (y) | 25.8±12.8 | 54.4±11.3 | <0.0001* |

| Illness period until ECT (y) | 17.1±13.7 | 14.1±16.4 | 0.6462 |

| Number of hospitalizations | 9.0±10.7 | 3.5±2.1 | 0.0249* |

| Number of acute ECT treatments | 15.4±5.6 | 14.0±6.0 | 0.5719 |

| Number of continuation of ECT treatments | 12.0±7.9 | 8.1±2.2 | 0.2783 |

| Number of maintenance ECT treatments | 5.3±4.1 | 5.5±0.7 | 0.9608 |

| Pre-ECT | Post-ECT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPRS | SCZ | MDD+BD | SCZ | MDD+BD | ||||

| Subitem | r | p | R | p | r | p | r | p |

| 1 Somatic concern | 0.1671 | 0.5681 | -0.2155 | 0.6816 | -0.0500 | 0.7714 | -0.0254 | 0.9200 |

| 2 Anxiety | -0.1109 | 0.7056 | -0.3383 | 0.5178 | 0.1040 | 0.5462 | 0.1392 | 0.5818 |

| 3 Depression | 0.1017 | 0.7294 | -0.4929 | 0.3205 | 0.0585 | 0.7345 | 0.1130 | 0.6553 |

| 4 Suicidality | 0.1245 | 0.6716 | -0.2386 | 0.6489 | 0.2286 | 0.1798 | 0.3256 | 0.1873 |

| 5 Guilt | 0.0373 | 0.8990 | -0.3973 | 0.4354 | 0.0501 | 0.7713 | 0.0946 | 0.7087 |

| 6 Hostility | -0.4240 | 0.1308 | 0.6171 | 0.1918 | 0.1231 | 0.5235 | 0.7283 | 0.0006* |

| 7 Elevated Mood | -0.4662 | 0.0928 | 0.7732 | 0.0713 | -0.0844 | 0.6243 | -0.1240 | 0.6236 |

| 8 Grandiosity | -0.0822 | 0.7799 | 0.6223 | 0.1870 | 0.0118 | 0.9443 | -0.1240 | 0.4593 |

| 9 Suspiciousness | -0.0101 | 0.9728 | 0.1038 | 0.8448 | 0.4007 | 0.0154* | 0.5229 | 0.0260* |

| 10 Hallucinations | 0.1377 | 0.2320 | 0.2671 | 0.6088 | 0.2286 | 0.1800 | 0.3256 | 0.1873 |

| 11 Unusual thought content | -0.2588 | 0.8618 | -0.1111 | 0.8839 | 0.1473 | 0.3911 | 0.2277 | 0.3635 |

| 12 Bizarre behaviour | -0.3672 | 0.1963 | -0.0266 | 0.9599 | 0.1970 | 0.2494 | 0.0737 | 0.7714 |

| 13 Self-neglect | 0.2665 | 0.3571 | -0.4150 | 0.4132 | 0.0493 | 0.7752 | 0.0538 | 0.8320 |

| 14 Disorientation | -0.1670 | 0.5680 | -0.2585 | 0.6208 | 0.2666 | 0.1159 | 0.4477 | 0.0624 |

| 15 Conceptual disorganisation | -0.0634 | 0.8293 | -0.4044 | 0.4264 | 0.0839 | 0.6265 | 0.4859 | 0.0409* |

| 16 Blunted affect | -0.1171 | 0.6899 | -0.4383 | 0.3846 | -0.1109 | 0.5192 | 0.4145 | 0.0872 |

| 17 Emotional withdrawal | 0.1111 | 0.7054 | -0.7229 | 0.1045 | -0.0510 | 0.7671 | 0.3649 | 0.1365 |

| 18 Motor retardation | -0.0316 | 0.9144 | -0.2155 | 0.6816 | 0.1787 | 0.297 | 0.3470 | 0.1583 |

| 19 Tension | 0.3357 | 0.2406 | -0.3310 | 0.5215 | -0.1649 | 0.3364 | 0.5327 | 0.0228* |

| 20 Uncooperativeness | 0.1258 | 0.6682 | 0.5852 | 0.2224 | 0.1522 | 0.8062 | 0.7282 | 0.0006* |

| 21 Excitement | -0.3584 | 0.2082 | 0.4334 | 0.3906 | 0.0292 | 0.8658 | 0.8775 | <0.0001* |

| 22 Distractibility | 0.0985 | 0.7374 | -0.5905 | 0.2172 | -0.1809 | 0.2907 | 0.3066 | 0.2159 |

| 23 Motor hyperactivity | -0.0779 | 0.7912 | 0.5700 | 0.2376 | -0.0833 | 0.6289 | 0.3256 | 0.1873 |

| 24 Mannerisms and posturing | 0.0207 | 0.9944 | 0.1541 | 0.7707 | -0.1301 | 0.4492 | 0.5680 | 0.0139* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).