1. Introduction

Depressive episodes represent the primary clinical manifestation of bipolar disorder (BD), accounting for the majority of symptomatic periods and playing a central role in the condition’s overall morbidity and mortality [

1,

2]. These episodes are closely linked to marked impairments in psychosocial functioning, reduced quality of life, and a significantly heightened risk of suicide [

3,

4], thereby presenting considerable challenges in clinical management.

The clinical heterogeneity of bipolar depressive episodes—often marked by mixed features, psychomotor agitation, and anxiety symptoms—further complicates both accurate diagnosis and effective treatment planning [

5,

6]. Misdiagnosis is common, particularly in the early stages of the illness, with bipolar depression often erroneously identified as unipolar major depressive disorder. Evidence suggests that nearly 50% of individuals initially diagnosed with treatment-resistant unipolar depression are reclassified as having bipolar disorder within one year [

7]. Such diagnostic delays are clinically consequential, frequently resulting in inappropriate pharmacological interventions —most notably, antidepressant monotherapy— which may exacerbate mood instability and negatively impact long-term outcomes [

8,

9].

Despite the considerable clinical burden associated with bipolar depression, there is still little attention to developing personalized pharmacological strategies tailored to the different clinical subtypes of the disorder. Treatment options remain limited, and to date only a small number of agents have received formal regulatory approval for this indication [

10,

11]. Among the currently recommended first-line treatments—namely quetiapine, lithium, lamotrigine, and the olanzapine–fluoxetine combination—therapeutic response rates are frequently suboptimal. Approximately 40% of patients treated with quetiapine over an eight-week period fail to demonstrate clinically meaningful improvement [

12,

13]. Response rates for other agents, including lithium, lamotrigine, and the olanzapine–fluoxetine combination, are often even lower [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Thus, many real-world bipolar patients are actually treatment-resistant, but no standardized diagnostic criteria have yet been established for treatment-resistant bipolar depression (TRBD). Various definitions have been suggested, typically grounded in a history of inadequate response to conventional pharmacotherapies [

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, the applicability of these criteria is constrained by the exclusion of certain authorized or by the absence of regulatory approval for several listed medications in various countries.

Lurasidone is an atypical antipsychotic with strong antagonistic activity at 5-HT₂A, 5-HT₇, and D₂ receptors, moderate partial agonism at 5-HT₁A receptors, and low affinity for H₁ and M₁ receptors [

23]. Its antagonism at D₂ receptors contributes to both antipsychotic and mood-stabilizing effects, while partial agonism at 5-HT₁A receptors may enhance mood and alleviate anxiety. Additionally, antagonism at 5-HT₂A and 5-HT₇ receptors is thought to enhance antidepressant efficacy and cognitive function. Minimal binding to H₁ and M₁ receptors reduces sedative and anticholinergic side effects, improving tolerability compared to other agents. Despite its well-characterized receptor profile, clinical evidence supporting the efficacy of lurasidone in bipolar depression remains limited and is restricted to patients with bipolar disorder type I [

24,

25,

26]. In Europe, lurasidone is approved exclusively for the treatment of schizophrenia. Data specifically addressing its use in treatment-resistant bipolar depression (TRBD) remain scarce. The present study aimed to evaluate the real-world effectiveness and tolerability of lurasidone in patients with TRBD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

A retrospective, multicentre, observational study was conducted to evaluate the short-term effectiveness and tolerability of lurasidone when used as an adjunctive therapy in patients diagnosed with treatment-resistant bipolar depression (TRBD).

Medical records were reviewed for both inpatients and outpatients diagnosed with bipolar disorder, according to

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision [

27] criteria, who were consecutively admitted or referred to one of the participating psychiatric centres between January and May 2025. These centres included: the Psychiatric Unit of San Luigi Gonzaga University Hospital of Orbassano (University of Turin, Italy); the Mental Health Departments of Alba and Bra (Cuneo, Italy); the Department of Mental Health of Biella (Biella, Italy); and the Department of Mental Health of Napoli 1 (Naples, Italy).

Patients included met the follow criteria: (a) age ≥18 years; (b) a confirmed primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder based on DSM-5-TR criteria; (c) presence of a current major depressive episode; (d) presence of treatment resistance, defined operationally in accordance with Murphy and colleagues [

28] as an insufficient response to at least two mood stabilizer classes (including atypical antipsychotics) and two antidepressant classes, with each pharmacological trial deemed adequate in terms of both dosage and duration, consistent with prior TRBD research [

29,

30]; (e) ongoing treatment with at least one mood stabiliser—lithium, valproate, or lamotrigine—maintained within therapeutic plasma levels; and (f) initiation of lurasidone as an adjunctive agent to the existing pharmacotherapy. The starting dose of lurasidone, along with any subsequent titration, was determined at the discretion of the treating psychiatrist, based on individual clinical presentation and judgement.

The study protocol received approval from the local Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent permitting the anonymous use of their clinical data for research purposes.

2.2. Assessment and Procedures

Socio-demographic, clinical, and safety-related information was obtained from patients’ medical records. Follow-up assessments were conducted in line with routine clinical practice. The severity of psychiatric symptoms was evaluated using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).

All psychiatric diagnoses and clinical assessments were performed by consultant psychiatrists with substantial clinical expertise.

The primary measure of treatment efficacy was the mean change in HAM-D scores from baseline to the end of the four-week observation period. In addition, a qualitative analysis was conducted, defining rates of treatment response as a reduction of ≥50% in HAM-D scores, and remission as achieving a HAM-D score below 7.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic and clinical variables were described using means and standard deviations for continuous measures, and percentages for categorical variables. A post hoc power analysis, based on a sample size of 60 participants and a significance level of 0.05, indicated a statistical power exceeding 95% for detecting changes in mean HAM-D and HAM-A scores (Cohen’s d = 1.92 for HAM-D reduction; d = 1.14 for HAM-A reduction).

Since baseline data followed a normal distribution (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test: D = 0.094; p = 0.20; Shapiro-Wilk test: D = 0.975; p = 0.25), parametric statistical methods were applied. Changes in clinical rating scale scores across the four-week observation period were examined using repeated measures analysis of variance (rm-ANOVA). Four distinct rm-ANOVA models were constructed, with the HAM-D, HAM-A, YMRS, and BPRS scores as dependent variables, to assess potential interaction effects over time. The assumption of sphericity for the covariance matrix was evaluated using Mauchly’s test; where this assumption was violated, the Greenhouse–Geisser epsilon (ε) correction was applied to adjust the degrees of freedom accordingly. Missing data were addressed using the Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) method.

Participants were subsequently categorised as responders or non-responders, based on a ≥50% reduction in HAM-D scores. Comparisons between the two groups were performed using the t-test for continuous variables and the χ² test for categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at a p-value of <0.05. All analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28.0.1.

3. Results

A total of sixty individuals met the inclusion criteria and were subsequently enrolled in the study cohort. Of these, 29 individuals (48.3%) were female. The cohort had a mean age of 44.9 ± 15.0 years. Regarding diagnostic classification, 29 participants (48.3%) met criteria for bipolar disorder type I, while the remaining 31 (51.7%) were diagnosed with bipolar disorder type II. The mean age at illness onset of was 26.5 ± 8.7 years. Comorbid psychiatric conditions were identified in 27 patients, accounting for 45% of the cohort.

Nearly all participants (n: 57; 95.0%) were receiving pharmacological treatment with mood stabilizing agents at baseline. Of these, approximately 10% were prescribed a combination regimen involving two mood stabilizers. Additionally, 17 individuals (28.3%) were concurrently treated with at least one antidepressant, and 40 patients (66.7%) were receiving antipsychotic medications. Baseline clinical assessment revealed a mean score of 25.9 ± 4.3 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), indicative of severe depressive symptoms, and a mean score of 24.5 ± 7.1 on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), consistent with moderate anxiety severity. A comprehensive overview of the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample at baseline is provided in

Table 1.

The mean daily dose of lurasidone prescribed at baseline was 32.9 mg/day, which increased to an average of 46.7 mg/day over the study period.

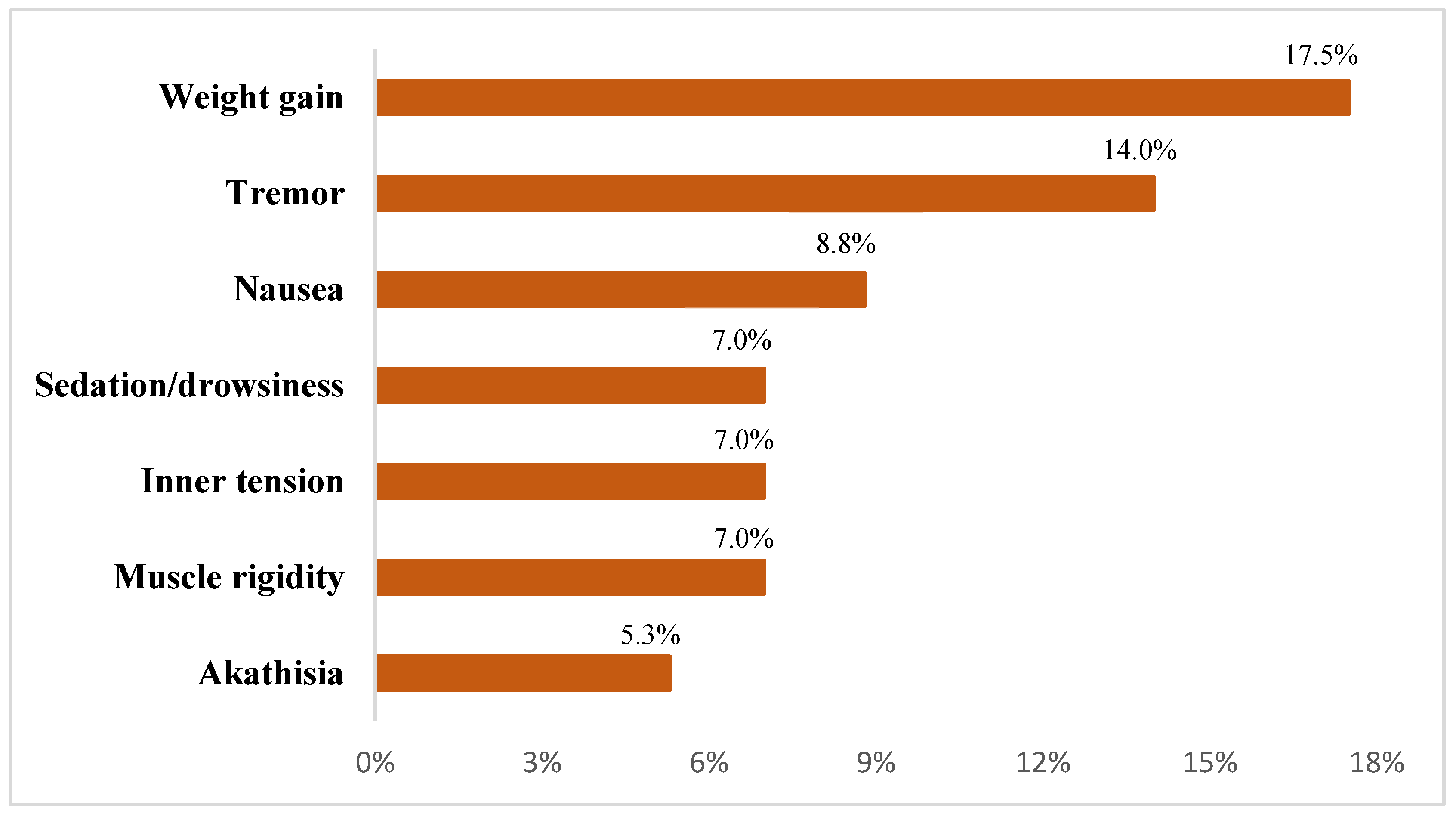

Overall, 57 participants (95.0%) completed the entire observational phase, while two patients withdrew by the second week due to symptom exacerbation that required inpatient psychiatric care and one additional discontinuation occurred in the third week, attributed to the emergence of severe agitation. Among those who completed the protocol, 41 participants (68.3%) experienced at least one treatment-emergent adverse event, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

Adverse events <5%: acute dystonia, urinary difficulties, emotional blunting, leg oedema, and nocturnal hyperhidrosis.

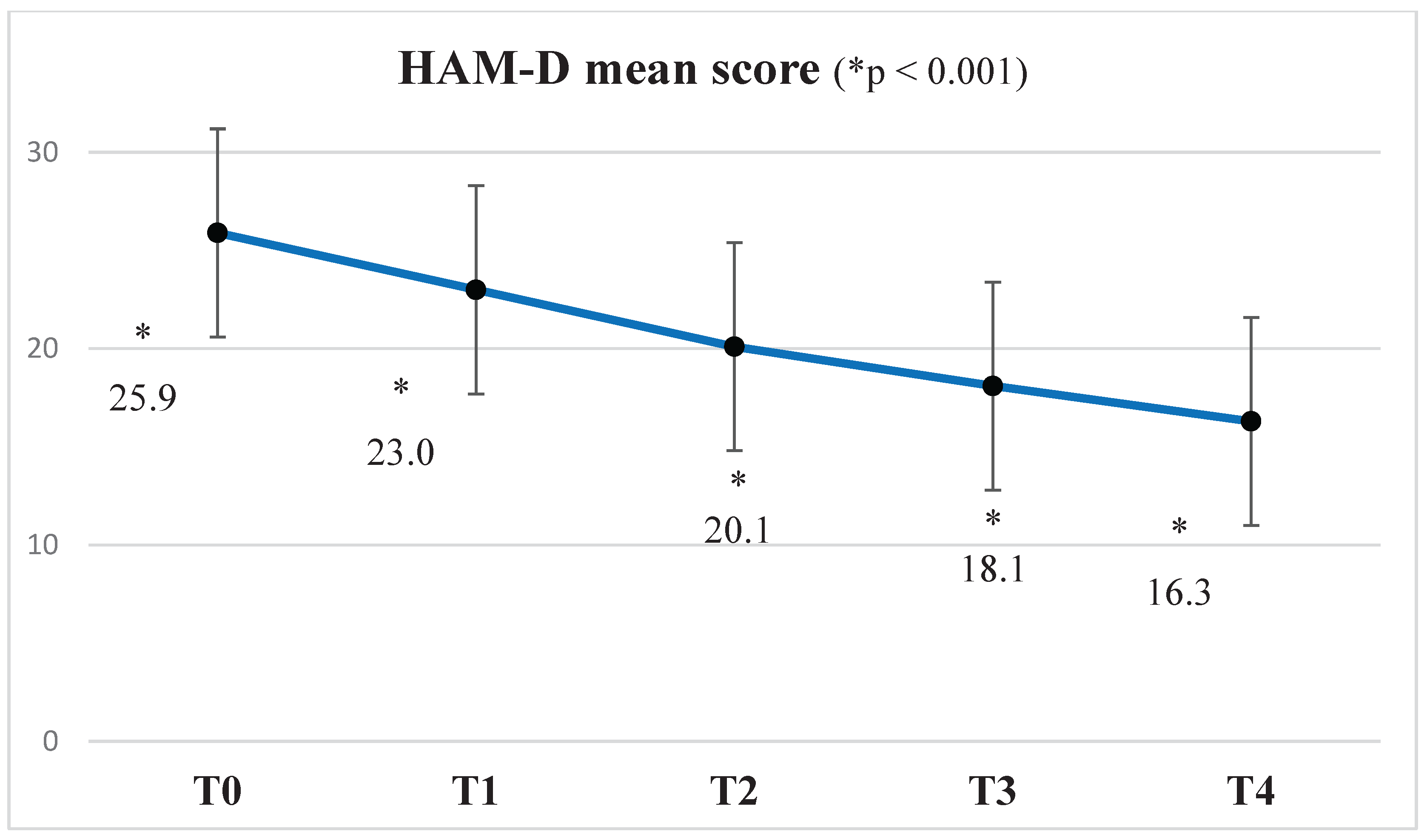

A statistically significant reduction in the mean HAM-D score was observed from baseline (T0) to week 4 (T4), with progressive improvement noted at each subsequent assessment. Specifically, mean scores decreased from 25.9 ± 4.3 at T0 to 23.0 ± 5.4 at T1 (ΔM = 2.847, S = 0.401,

p <0.001), 20.01 ± 5.7 at T2 (ΔM = 5.915, SE = 0.586,

p <0.001), 18.1 ± 6.2 at T3 (ΔM = 7.932, SE = 0.587,

p <0.001), and finally 16.3 ± 6.9 at T4 (ΔM = 9.576, SE = 0.656,

p <0.001) (see

Figure 2).

Statistically significant reductions from baseline were observed at all subsequent time points for the HAM-A score. Mean values decreased from 24.5 ± 7.1 at baseline (T0) to 22.4 ± 7.7 at T1 (ΔM = 2.136, SE = 0.352, p < 0.001), 20.6 ± 8.7 at T2 (ΔM = 4.068, SE = 0.536, p < 0.001), 19.3 ± 9.2 at T3 (ΔM = 5.441, SE = 0.668, p < 0.001), and 18.0 ± 10.0 at T4 (ΔM = 6.492, SE = 0.752, p < 0.001).

A comparable trend was found for the BPRS scores, which significantly declined from 30.3 ± 4.1 at baseline to 27.9 ± 4.9 at T1 (ΔM = 2.328, SE = 0.339, p < 0.001), 25.4 ± 6.5 at T2 (ΔM = 4.931, SE = 0.570, p < 0.001), 23.2 ± 7.4 at T3 (ΔM = 7.259, SE = 0.754, p < 0.001), and 20.4 ± 8.3 at T4 (ΔM = 9.845, SE = 0.917, p < 0.001).

Similarly, the YMRS scores demonstrated a decrease over time, from a baseline mean of 4.7 ± 3.3 to 3.6 ± 3.2 at T1 (ΔM = 1.088, SE = 0.226, p < 0.001), 3.0 ± 3.2 at T2 (ΔM = 1.737, SE = 0.393, p < 0.001), 2.1 ± 2.6 at T3 (ΔM = 2.702, SE = 0.391, p < 0.001), and 1.9 ± 2.7 at T4 (ΔM = 2.860, SE = 0.437, p < 0.001).

All findings were confirmed by the Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) analysis, which resulted in consistent findings across all time points.

By the end of the observation period, 20 out of 60 patients (33.3%) met criteria for clinical response, defined as a ≥50% reduction in HAM-D scores. Remission, defined as a HAM-D score <7, was achieved by 2 patients (3.3%).

When comparing responders (n: 30; 33.3%) and non-responders (n: 40; 66.7%), no statistically significant differences were found in key sociodemographic variables, including age and years of education, nor in core clinical characteristics such as bipolar disorder subtype and age at illness onset. Baseline scores on the HAM-D, HAM-A, YMRS, and BPRS did not significantly differ between groups (p: 0.418, p: 0.253, p: 0.109, and p: 0.306, respectively), indicating comparable levels of depressive, anxious, manic, and psychotic symptoms at study entry.

Regarding lurasidone augmentation, responders received a significantly higher initial dose compared to non-responders (39.5 ± 19.5 mg vs 29.6 ± 15.6 mg; p: 0.037). However, no significant between-group difference was found in the lurasidone dose at the end of the observational period (p: 0.219).

Regarding treatment-related characteristics, a significant association was found between the use of dual mood stabilizers and clinical response (p: 0.007). Patients receiving more than one mood-stabilizing agent were more likely to achieve a ≥50% reduction in HAM-D scores (70%) compared to those treated with a single mood stabilizer (26%). Similarly, antipsychotic use was significantly associated with clinical response (p: 0.008), with a higher proportion of patients receiving antipsychotics showing a clinical response (58.8%) relative to those who did not (23.2%). A significant association also emerged between antidepressant use and clinical response (p: 0.012); unexpectedly, patients who did not receive antidepressants were more likely to respond to treatment (55%) than those who did (22.5%).

4. Discussion

Treatment-resistant bipolar depression (TRBD) represents a significant and often under-recognised public health issue. While bipolar disorder (BD) is a leading cause of global disability, a subset of patients who do not adequately respond to standard treatments frequently experience a particularly chronic and debilitating course, with significant impacts on quality of life, psychosocial functioning, and long-term outcomes [

31,

32,

33]. Individuals with TRBD often suffer from prolonged depressive episodes, elevated suicide risk, diminished occupational and social engagement, and poor treatment adherence—factors that contribute to increased hospitalization, unemployment, and a range of psychiatric and physical comorbidities [

34].

Despite the urgent demand for effective therapeutic strategies, the clinical management of TRBD remains challenging and inconsistently standardized. This is largely due to the absence of universally accepted diagnostic criteria and clearly established treatment guidelines [

35]. Such lack of consensus not only complicates clinical decision-making but also hinders research efforts, limiting accurate assessment of the condition’s prevalence and obstructing the advancement of targeted interventions. Although estimates vary widely depending on the criteria applied, existing data indicate that approximately one-quarter of individuals with BD may experience treatment-resistant depressive episodes [

17,

31].

In this context, lurasidone has emerged as a noteworthy pharmacological option. Classified as a second-generation antipsychotic, it has demonstrated efficacy and safety in the treatment of bipolar depression [

25,

26,

36] and is included as a first-line option in international clinical guidelines [

10,

37]. However, despite this evidence, its use for bipolar depression remains off-label in European countries due to regulatory limitations.

Based on the outcomes of our study, lurasidone demonstrated clear efficacy in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms over a four-week treatment period. The progressive reduction in mean scores across all assessment scales—HAM-D, HAM-A, BPRS, and YMRS— reflects a consistent pattern of clinical improvement from baseline (T0) to week four (T4). Notably, each scale showed a significant and sustained decrease at every assessment point, indicating a rapid onset of antidepressant action, with therapeutic effects that continued to build over time.

By the end of the observation period, one-third of patients in our sample (33.3%) achieved a clinical response, while remission was observed in only 3.3% of cases. These rates differ from those reported in some previous studies [

25,

38], which may be attributable to differences in baseline clinical characteristics, such as the severity of depressive symptoms at study entry. As indicated by the initial HAM-D scores, patients in our cohort were experiencing moderate to severe depressive episodes, and their complexity—reflective of real-world clinical populations—likely reduced the probability of achieving full symptomatic remission within a four-week period. Our findings might indicate that lurasidone may have a greater effect on certain symptom domains of bipolar depression, while its impact on other aspects could be more limited, with efficacy possibly linked to specific clinical features beyond symptom severity. This is also observed in the study by McIntyre and colleagues [

38], which included individuals with bipolar depression characterized by mixed features that may have influenced both the therapeutic response and the overall outcomes observed.

The mean lurasidone dose observed in our sample (39.8 mg/day) aligns with dosing patterns commonly reported in non–treatment-resistant bipolar depression [

39], suggesting that higher doses are not routinely utilized in clinical practice, even in cases of TRBD. Supporting this observation, responders received significantly higher initial doses of lurasidone compared to non-responders; however, no significant difference was observed in dosing at week four. A higher baseline dose may have promoted more rapid activation of dopaminergic and serotonergic pathways, thereby enhancing the early antidepressant effects of lurasidone. It is also conceivable that clinicians, guided by clinical judgement, prescribed higher starting doses to patients perceived as more severely affected or better able to tolerate dose escalation, which may have indirectly influenced our outcomes. Nevertheless, the lack of a statistically significant difference in lurasidone dose at the end of the observation between groups suggests that therapeutic response within the administered dose range may not be strictly dose-dependent [

39]. Instead, individual variability in pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic parameters, alongside dose adjustments made during treatment in response to adverse effects or clinical improvement, may have mitigated any initial differences in dosing between groups.

In our sample, bipolar disorder subtype and baseline clinical scores did not significantly influence treatment response. However, clinical improvement was significantly associated with lurasidone augmentation in combination with dual mood stabilizers and antipsychotics, suggesting a potentiated effect via complementary mechanisms [

40]. Conversely, patients receiving antidepressants showed lower response rates, likely due to more complex clinical presentations due to refractory depressive episodes or in the presence of comorbidities [

41,

42] Additionally, antidepressant use in BD may contribute to mood destabilization [

43,

44], potentially reducing the efficacy of adjunctive lurasidone.

In terms of tolerability, adverse events (AEs) were reported in 68.3% of the sample, with weight gain, tremor, and nausea emerging as the most frequently observed symptoms. This pattern aligns with previously documented AE profiles in clinical trials evaluating lurasidone for bipolar depression [

39]. Although most AEs were of mild to moderate intensity, treatment was discontinued in one case due to severe agitation. The relatively high incidence of AEs in this naturalistic cohort may reflect the greater clinical heterogeneity and comorbidity burden typical of real-world populations, which are often under-represented in randomized controlled trials due to restrictive eligibility criteria.

These findings should be considered within the context of several methodological limitations. The retrospective observational design of the study and the relatively short duration of the study (four weeks) may limit the ability to infer causality or assess the durability of treatment effects. The absence of a control group further affects the internal validity and interpretability of the results. Additionally, the small sample size restricted the possibility of conducting stratified analyses based on specific clinical subgroups. The inclusion of participants with a substantial burden of psychiatric comorbidities may have influenced both effectiveness and tolerability outcomes. Nonetheless, such comorbidities are highly prevalent among individuals with BD, thereby enhancing the ecological validity and applicability of the findings to real-world clinical populations. Furthermore, potential pharmacokinetic interactions—particularly those affecting lurasidone metabolism—were not systematically evaluated and may have contributed to interindividual variability in treatment response. Lastly, adverse events were recorded based exclusively on clinical documentation, without the implementation of standardized assessment tools, which may have limited the accuracy and consistency of tolerability reporting.

5. Conclusions

Despite the acknowledged limitations, this study provides novel evidence on the use of lurasidone in treatment-resistant bipolar depression (TRBD). Our findings already highlight some clinical profiles within this heterogeneous population for which lurasidone may represent an appropriate adjunctive treatment option. Nevertheless, its current off-label status in Europe and the modest remission rates observed reinforce the need for further research in larger and more diverse samples. Future investigations should aim to confirm these preliminary indications and to better define how lurasidone can be integrated into personalized treatment strategies, ultimately contributing to the development of precision approaches for patients who remain difficult to treat.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M. and G.R.; methodology, G.P., G.M. and G.R.; validation, G.P., E.P., C.I.C., V.M., C.B., G.M. and G.R.; formal analysis, G.P.; investigation, G.P., E.P., C.I.C.,V.M. and C.B.; resources, G.P.; data curation, G.P., E.P., C.I.C., V.M. and C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P.; writing—review and editing, G.P., G.M., and G.R.; visualization, E.P., C.I.C., V.M., C.B., G.M. and G.R.; supervision, G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. However, the data are not publicly accessible due to confidentiality restrictions related to hospital clinical records.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript: Bipolar Disorder (BD); Treatment-resistant Bipolar Depression (TRBD); Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D); Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS); Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A); Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS); repeated measures analysis of variance (rm-ANOVA); Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF); Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR); SD: standard deviation.

References

- Kupka RW, Altshuler LL, Nolen WA, Suppes T, Luckenbaugh DA, Leverich GS, Frye MA, Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Grunze H, Post RM. Three times more days depressed than manic or hypomanic in both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007 Aug;9(5):531-5. [CrossRef]

- Baldessarini RJ, Vázquez GH, Tondo L. Bipolar depression: a major unsolved challenge. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2020 Jan 6;8(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Malhi GS, Ivanovski B, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Mitchell PB, Vieta E, Sachdev P. Neuropsychological deficits and functional impairment in bipolar depression, hypomania and euthymia. Bipolar Disord. 2007 Feb-Mar;9(1-2):114-25. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Rojas L, Gurpegui M, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Gutiérrez-Ariza JA, Ruiz-Veguilla M, Jurado D. Quality of life in bipolar disorder patients: a comparison with a general population sample. Bipolar Disord. 2008 Jul;10(5):625-34. [CrossRef]

- Fagiolini A, Coluccia A, Maina G, Forgione RN, Goracci A, Cuomo A, Young AH. Diagnosis, Epidemiology and Management of Mixed States in Bipolar Disorder. CNS Drugs. 2015 Sep;29(9):725-40. [CrossRef]

- Persons JE, Lodder P, Coryell WH, Nurnberger JI, Fiedorowicz JG. Symptoms of mania and anxiety do not contribute to suicidal ideation or behavior in the presence of bipolar depression. Psychiatry Res. 2022 Jan;307:114296. [CrossRef]

- Sharma V, Khan M, Smith A. A closer look at treatment resistant depression: is it due to a bipolar diathesis? J Affect Disord. 2005 Feb;84(2-3):251-7. [CrossRef]

- Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, Marangell LB, Wisniewski SR, Gyulai L, Friedman ES, Bowden CL, Fossey MD, Ostacher MJ, Ketter TA, Patel J, Hauser P, Rapport D, Martinez JM, Allen MH, Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Dennehy EB, Thase ME. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007 Apr 26;356(17):1711-22. [CrossRef]

- Levenberg K, Cordner ZA. Bipolar depression: a review of treatment options. Gen Psychiatr. 2022 Aug 4;35(4):e100760. [CrossRef]

- Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Bond DJ, Frey BN, Sharma V, Goldstein BI, Rej S, Beaulieu S, Alda M, MacQueen G, Milev RV, Ravindran A, O'Donovan C, McIntosh D, Lam RW, Vazquez G, Kapczinski F, McIntyre RS, Kozicky J, Kanba S, Lafer B, Suppes T, Calabrese JR, Vieta E, Malhi G, Post RM, Berk M. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018 Mar;20(2):97-170. [CrossRef]

- Malhi GS, Bell E, Boyce P, Bassett D, Berk M, Bryant R, Gitlin M, Hamilton A, Hazell P, Hopwood M, Lyndon B, McIntyre RS, Morris G, Mulder R, Porter R, Singh AB, Yatham LN, Young A, Murray G. The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders: Bipolar disorder summary. Bipolar Disord. 2020 Dec;22(8):805-821. [CrossRef]

- De Fruyt J, Deschepper E, Audenaert K, Constant E, Floris M, Pitchot W, Sienaert P, Souery D, Claes S. Second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2012 May;26(5):603-17. [CrossRef]

- Sienaert P, Lambrichts L, Dols A, De Fruyt J. Evidence-based treatment strategies for treatment-resistant bipolar depression: a systematic review. Bipolar Disord. 2013 Feb;15(1):61-9. [CrossRef]

- Geddes JR, Calabrese JR, Goodwin GM. Lamotrigine for treatment of bipolar depression: independent meta-analysis and meta-regression of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2009 Jan;194(1):4-9. [CrossRef]

- Sidor MM, Macqueen GM. Antidepressants for the acute treatment of bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011 Feb;72(2):156-67. [CrossRef]

- Bahji A, Ermacora D, Stephenson C, Hawken ER, Vazquez G. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological treatments for the treatment of acute bipolar depression: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020 May 15;269:154-184. [CrossRef]

- Fornaro M, Fusco A, Novello S, Mosca P, Anastasia A, De Blasio A, et al. Predictors of treatment resistance across different clinical subtypes of depression: comparison of unipolar vs. bipolar cases. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:438. [CrossRef]

- Rakofsky JJ, Lucido MJ, Dunlop BW. Lithium in the treatment of acute bipolar depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022 Jul 1;308:268-280. [CrossRef]

- Sachs, GS. Treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996 Jun;19(2):215-36. [CrossRef]

- Pacchiarotti I, Mazzarini L, Colom F, Sanchez-Moreno J, Girardi P, Kotzalidis GD, Vieta E. Treatment-resistant bipolar depression: towards a new definition. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009 Dec;120(6):429-40. [CrossRef]

- Poon Hui S, Sim K, Baldessarini RJ. Pharmacological Approaches for Treatment-resistant Bipolar Disorder. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(5):592-604. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Mazzei, D.; Berk, M.; Cipriani, A.; Cleare, A.J.; Florio, A.D.; Dietch, D.; Geddes, J.R.; Goodwin, G.M.; Grunze, H.; Hayes, J.F.; Jones, I.; Kasper, S.; Macritchie, K.; McAllister- Williams, R.H.; Morriss, R.; Nayrouz, S.; Pappa, S.; Soares, J.C.; Smith, D.J.; Suppes, T.; Talbot, P.; Vieta, E.; Watson, S.; Yatham, L.N.; Young, A.H.; Stokes, P.R.A. Treatment-resistant and multi- therapy-resistant criteria for bipolar depression: Consensus definition. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 214(1), 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl MS, Essential Psychopharmacology – Prescriber’s Guide seventh edition, 2021, pp. 457-464.

- Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, Kroger H, Hsu J, Sarma K, Sachs G. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014 Feb;171(2):160-8. [CrossRef]

- Suppes T, Kroger H, Pikalov A, Loebel A. Lurasidone adjunctive with lithium or valproate for bipolar depression: A placebo-controlled trial utilizing prospective and retrospective enrolment cohorts. J Psychiatr Res. 2016 Jul;78:86-93. [CrossRef]

- Kato T, Ishigooka J, Miyajima M, Watabe K, Fujimori T, Masuda T, Higuchi T, Vieta E. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of lurasidone monotherapy for the treatment of bipolar I depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020 Dec;74(12):635-644. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision: DSM-5-TR. APA; 2022.

- Murphy BL, Babb SM, Ravichandran C, Cohen BM. Oral SAMe in persistent treatment-refractory bipolar depression: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014 Jun;34(3):413-6. [CrossRef]

- Martinotti G, Dell'Osso B, Di Lorenzo G, Maina G, Bertolino A, Clerici M, Barlati S, Rosso G, Di Nicola M, Marcatili M, d'Andrea G, Cavallotto C, Chiappini S, De Filippis S, Nicolò G, De Fazio P, Andriola I, Zanardi R, Nucifora D, Di Mauro S, Bassetti R, Pettorruso M, McIntyre RS, Sensi SL, di Giannantonio M, Vita A; REAL-ESK Study Group. Treating bipolar depression with esketamine: Safety and effectiveness data from a naturalistic multicentric study on esketamine in bipolar versus unipolar treatment-resistant depression. Bipolar Disord. 2023 May;25(3):233-244. [CrossRef]

- Teobaldi E, Pessina E, Martini A, Cattaneo CI, De Berardis D, Martiadis V, Maina G, Rosso G. Cariprazine Augmentation in Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Depression: Data from a Retrospective Observational Study. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2024;22(10):1742-1748. [CrossRef]

- Mendlewicz J, Massat I, Linotte S, Kasper S, Konstantinidis A, Lecrubier Y, et al. Identification of clinical factors associated with resistance to antidepressants in bipolar depression: results from an European Multicentre Study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25:297–301. [CrossRef]

- Heerlein K, Young AH, Otte C, Frodl T, Degraeve G, Hagedoorn W, Oliveira-Maia AJ, Perez Sola V, Rathod S, Rosso G, Sierra P, Morrens J, Van Dooren G, Gali Y, Perugi G. Real-world evidence from a European cohort study of patients with treatment resistant depression: Baseline patient characteristics. J Affect Disord. 2021 Mar 15;283:115-122. [CrossRef]

- Heerlein K, De Giorgi S, Degraeve G, Frodl T, Hagedoorn W, Oliveira-Maia AJ, Otte C, Perez Sola V, Rathod S, Rosso G, Sierra P, Vita A, Morrens J, Rive B, Mulhern Haughey S, Kambarov Y, Young AH. Real-world evidence from a European cohort study of patients with treatment resistant depression: Healthcare resource utilization. J Affect Disord. 2022 Feb 1;298(Pt A):442-450. [CrossRef]

- Crown, W.H.; Finkelstein, S.; Berndt, E.R.; Ling, D.; Poret, A.W.; Rush, A.J.; Russell, J.M. The impact of treatment-resistant depression on health care utilization and costs. J. Clin. Psychiatry, 2002, 63(11), 963-971. [CrossRef]

- Demyttenaere K, Van Duppen Z. The Impact of (the Concept of) Treatment-Resistant Depression: An Opinion Review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019 Feb 1;22(2):85-92. [CrossRef]

- Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, Kroger H, Sarma K, Xu J, et al. Lurasidone as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate for the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:169–77. [CrossRef]

- Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, Aronson JK, Barnes T, Cipriani A, Coghill DR, Fazel S, Geddes JR, Grunze H, Holmes EA, Howes O, Hudson S, Hunt N, Jones I, Macmillan IC, McAllister-Williams H, Miklowitz DR, Morriss R, Munafò M, Paton C, Saharkian BJ, Saunders K, Sinclair J, Taylor D, Vieta E, Young AH. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: Revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016 Jun;30(6):495-553. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre RS, Cucchiaro J, Pikalov A, Kroger H, Loebel A. Lurasidone in the treatment of bipolar depression with mixed (subsyndromal hypomanic) features: post hoc analysis of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015 Apr;76(4):398-405. [CrossRef]

- Lin YW, Chen YB, Hung KC, Liang CS, Tseng PT, Carvalho AF, Vieta E, Solmi M, Lai EC, Lin PY, Hsu CW, Tu YK. Efficacy and acceptability of lurasidone for bipolar depression: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. BMJ Ment Health. 2024 Nov 18;27(1):e301165. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese F, Luoni A, Guidotti G, Racagni G, Fumagalli F, Riva MA. Modulation of neuronal plasticity following chronic concomitant administration of the novel antipsychotic lurasidone with the mood stabilizer valproic acid. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013 Mar;226(1):101-12. [CrossRef]

- Albert U, Rosso G, Maina G, Bogetto F. Impact of anxiety disorder comorbidity on quality of life in euthymic bipolar disorder patients: differences between bipolar I and II subtypes. J Affect Disord. 2008 Jan;105(1-3):297-303. [CrossRef]

- Sesso G, Brancati GE, Masi G. Comorbidities in Youth with Bipolar Disorder: Clinical Features and Pharmacological Management. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2023;21(4):911-934. [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, MJ. Antidepressants in Bipolar Depression: An Enduring Controversy. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2019 Jul;17(3):278-283. [CrossRef]

- Aydin IH, El-Mallakh RS. Concept article: Antidepressant-induced destabilization in bipolar illness mediated by serotonin 3 receptor (5HT3). Bipolar Disord. 2024 Dec;26(8):772-778. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).