Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nemeroff, C.B. Prevalence and management of treatment-resistant depression. . 2007, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, H.E. Therapy-Resistant Depressions – A Clinical Classification. Pharmacopsychiatry 1974, 7, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachowicz, K.; Sowa-Kućma, M. The treatment of depression — searching for new ideas. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 988648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souery, D.; Amsterdam, J.; de Montigny, C.; Lecrubier, Y.; Montgomery, S.; Lipp, O.; Racagni, G.; Zohar, J.; Mendlewicz, J. Treatment resistant depression: methodological overview and operational criteria. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999, 9, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Alsuwaidan, M.; Baune, B.T.; Berk, M.; Demyttenaere, K.; Goldberg, J.F.; Gorwood, P.; Ho, R.; Kasper, S.; Kennedy, S.H.; et al. Treatment-resistant depression: definition, prevalence, detection, management, and investigational interventions. World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 394–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, B.; Olivier, J.D.A. Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of Psychedelics in Treatment-Resistant Depres-sion (TRD). Adv Exp Med Biol. 2024, 1456, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarate, C.A.; Singh, J.B.; Carlson, P.J.; Brutsche, N.E.; Ameli, R.; Luckenbaugh, D.A.; Charney, D.S.; Manji, H.K. A Randomized Trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate Antagonist in Treatment-Resistant Major Depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, E.J.; Singh, J.B.; Fedgchin, M.; Cooper, K.; Lim, P.; Shelton, R.C.; Thase, M.E.; Winokur, A.; Van Nueten, L.; Manji, H.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Intranasal Esketamine Adjunctive to Oral Antidepressant Therapy in Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trullas, R.; Skolnick, P. Functional antagonists at the NMDA receptor complex exhibit antidepressant actions. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990, 185, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skolnick, P.; Layer, R.T.; Popik, P.; Nowak, G.; Paul, I.A.; Trullas, R. Adaptation of N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) Receptors following Antidepressant Treatment: Implications for the Pharmacotherapy of Depression. Pharmacopsychiatry 1996, 29, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domino, E.F.; Warner, D.S. Taming the Ketamine Tiger. Anesthesiology 2010, 113, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudoh, A.; Takahira, Y.; Katagai, H.; Takazawa, T. Small-Dose Ketamine Improves the Postoperative State of Depressed Patients. Anesthesia Analg. 2002, 95, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Lee, B.; Liu, R.-J.; Banasr, M.; Dwyer, J.M.; Iwata, M.; Li, X.-Y.; Aghajanian, G.; Duman, R.S. mTOR-Dependent Synapse Formation Underlies the Rapid Antidepressant Effects of NMDA Antagonists. Science 2010, 329, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanos, P.; Gould, T.D. Mechanisms of ketamine action as an antidepressant. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Jelen, L.; Young, A.H.; Stone, J.M. Ketamine: A tale of two enantiomers. J. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 35, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Kawano, Y.; Fukuyama, K.; Motomura, E.; Shiroyama, T. Candidate Strategies for Development of a Rapid-Acting Antidepressant Class That Does Not Result in Neuropsychiatric Adverse Effects: Prevention of Ketamine-Induced Neuropsychiatric Adverse Reactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, E.M.; Riggs, L.M.; Michaelides, M.; Gould, T.D. Mechanisms of ketamine and its metabolites as antidepressants. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 197, 114892–114892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Halaris, A. Adjunctive dopaminergic enhancement of esketamine in treatment-resistant depression. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 119, 110603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summary of product characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/spravato-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Chepke, C.; Shelton, R.; Sanacora, G.; Doherty, T.; Tsytsik, P.; Parker, N. Real-World Safety of Esketamine Nasal Spray: A Comprehensive Analysis of Esketamine and Respiratory Depression. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, D. Comparing the adverse effects of ketamine and esketamine between genders using FAERS data. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1329436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wang, B.; Yuan, S.; Wu, S.; Liu, J.; He, M.; Wang, J. Neurological Adverse Events Associated With Esketamine: A Disproportionality Analysis for Signal Detection Leveraging the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 849758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Qin, G. The efficacy and safety of fluoxetine versus placebo for stroke recovery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharm. Weekbl. 2023, 45, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lense, X.; Hiemke, C.; Funk, C.; Havemann-Reinecke, U.; Hefner, G.; Menke, A.; Mössner, R.; Riemer, T.; Scherf-Clavel, M.; Schoretsanitis, G.; et al. Venlafaxine’s therapeutic reference range in the treatment of depression revised: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology 2023, 241, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrough, J.W.; Abdallah, C.G.; Anticevic, A.; Collins, K.A.; Geha, P.; Averill, L.A.; Schwartz, J.; DeWilde, K.E.; Averill, C.; Yang, G.J.; et al. Reduced global functional connectivity of the medial prefrontal cortex in major depressive disorder. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2016, 37, 3214–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanacora, G.; Yan, Z.; Popoli, M. The stressed synapse 2.0: pathophysiological mechanisms in stress-related neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 23, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardingham, G.E.; Bading, H. Synaptic versus extrasynaptic NMDA receptor signalling: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.M.L.; Defaix, C.; Mendez-David, I.; Tritschler, L.; Etting, I.; Alvarez, J.-C.; Choucha, W.; Colle, R.; Corruble, E.; David, D.J.; et al. Intranasal (R, S)-ketamine delivery induces sustained antidepressant effects associated with changes in cortical balance of excitatory/inhibitory synaptic activity. Neuropharmacology 2022, 225, 109357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.M.L.; Defaix, C.; Mendez-David, I.; Tritschler, L.; Etting, I.; Alvarez, J.-C.; Choucha, W.; Colle, R.; Corruble, E.; David, D.J.; et al. Intranasal (R, S)-ketamine delivery induces sustained antidepressant effects associated with changes in cortical balance of excitatory/inhibitory synaptic activity. Neuropharmacology 2022, 225, 109357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, J.F.; Nasrallah, H.A. Major depression is a serious and potentially fatal brain syndrome requiring pharmacotherapy or neuromodulation, and psychotherapy. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 1423–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlik, J.L.; Wahid, S.; Teopiz, K.M.; McIntyre, R.S.; Krystal, J.H.; Rhee, T.G. Recent Advances in the Treatment of Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Narrative Review of Literature Published from 2018 to 2023. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2024, 26, 176–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.; Wilkinson, S.T.; Al Jurdi, R.K.; Petrillo, M.P.; Zaki, N.; Borentain, S.; Fu, D.J.; Turkoz, I.; Sun, L.; Brown, B.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Esketamine Nasal Spray in Patients with Treatment-Resistant Depression Who Completed a Second Induction Period: Analysis of the Ongoing SUSTAIN-3 Study. CNS Drugs 2023, 37, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Ma, W.; Li, X.; Gao, Q.; Lian, S.; Yu, W. Esketamine Nasal Spray in Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, Y.; Li, J. Efficacy of esketamine nasal spray for treatment-resistant depression: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Medicine 2025, 104, e41495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, S.; Brennan, E.; Patel, A.; Moran, M.; Wallier, J.; Liebowitz, M.R. Managing dissociative symptoms following the use of esketamine nasal spray: a case report. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 36, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gu, H.; Li, W.; Chen, Y. A real-world pharmacovigilance study of esketamine nasal spray. Medicine 2024, 103, e39484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.; Wajs, E.; Melkote, R.; Miller, J.; Singh, J.B.; Weber, M.A. Cardiac Safety of Esketamine Nasal Spray in Treatment-Resistant Depression: Results from the Clinical Development Program. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs-Ross, R.; Daly, E.J.; Zhang, Y.; Lane, R.; Lim, P.; Morrison, R.L.; Hough, D.; Manji, H.; Drevets, W.C.; Sanacora, G.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Esketamine Nasal Spray Plus an Oral Antidepressant in Elderly Patients With Treatment-Resistant Depression—TRANSFORM-3. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, A.T.; Lakhani, M.; Teopiz, K.M.; Wong, S.; Le, G.H.; Ho, R.C.; Rhee, T.G.; Cao, B.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Mansur, R.; et al. Hepatic adverse events associated with ketamine and esketamine: A population-based disproportionality analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 374, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, G.H.; Wong, S.; Kwan, A.T.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Mansur, R.B.; Teopiz, K.M.; Ho, R.; Rhee, T.G.; Vinberg, M.; Cao, B.; et al. Association of antidepressants with cataracts and glaucoma: a disproportionality analysis using the reports to the United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) pharmacovigilance database. CNS Spectrums 2024, 29, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, C. Treatment-resistant depression: role of genetic factors in the perspective of clinical stratification and treatment personalisation. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.J.; Michel, C.A.; Auerbach, R.P. Improving Suicide Prevention Through Evidence-Based Strategies: A Systematic Review. FOCUS 2023, 21, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swainson, J.; Thomas, R.K.; Archer, S.; Chrenek, C.; MacKay, M.-A.; Baker, G.; Dursun, S.; Klassen, L.J.; Chokka, P.; Demas, M.L. Esketamine for treatment resistant depression. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2019, 19, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Mansur, R.B.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Teopiz, K.M.; Kwan, A.T.H. The association between ketamine and esketamine and suicidality: reports to the Food And Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastaldon, C.; Raschi, E.; Kane, J.M.; Barbui, C.; Schoretsanitis, G. Post-Marketing Safety Concerns with Esketamine: A Disproportionality Analysis of Spontaneous Reports Submitted to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Psychother. Psychosom. 2020, 90, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Barquera, J.A.O.-S.; García, L.A.D.L.G.; García, S.V.E.; Torres, G.S.; Jalomo, G.A.P. Paradoxical Depressive Response to Intranasal Esketamine in Treatment-Resistant Depression: A Case Series. Am. J. Case Rep. 2024, 26, e945475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.B.; Li, M.; Li, X.B.; Dai, H.B.; Peng, M. The effect of a subclinical dose of esketamine on depression and pain after cesarean section: A prospective, randomized, double-blinded controlled trial. Medicine 2024, 103, e40295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, K.N.; Saitis, A.; Schatzberg, A.F. Esketamine Treatment for Depression in Adults: A PRISMA Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2025, 182, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spravato | European Medicines Agency (EMA). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/spravato-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Wei, Y.; Chang, L.; Hashimoto, K. Molecular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant actions of arketamine: beyond the NMDA receptor. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 27, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudot, J.; Soeiro, T.; Tambon, M.; Navarro, N.; Veyrac, G.; Mezaache, S.; Micallef, J. Safety concerns on the abuse potential of esketamine: Multidimensional analysis of a new anti-depressive drug on the market. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 36, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, C.R.; Aaronson, S.T.; Sackeim, H.A.; Duffy, W.; Stedman, M.; Quevedo, J.; Allen, R.M.; Riva-Posse, P.; Berger, M.A.; Alva, G.; et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment exposure of patients with marked treatment-resistant unipolar major depressive disorder: A RECOVER trial report. Brain Stimul. 2024, 17, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, M.; Daly, E.J.; Popova, V.; Heerlein, K.; Canuso, C.; Drevets, W.C. Comment to Drs Gastaldon, Papola, Ostuzzi and Barbui. Epidemiology Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calapai, F.; Ammendolia, I.; Cardia, L.; Currò, M.; Calapai, G.; Esposito, E.; Mannucci, C. Pharmacovigilance of Risankizumab in the Treatment of Psoriasis and Arthritic Psoriasis: Real-World Data from EudraVigilance Database. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MedDRA and Pharmacovigilance: A Complex and Little Evaluated Tool. Prescrire. Int. 2016, 25, 247–250.

- Bate, A.; Evans, S.J.W. Quantitative signal detection using spontaneous ADR reporting. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2009, 18, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faillie, J.-L. Case–non-case studies: Principle, methods, bias and interpretation. Therapies 2019, 74, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.M.; Thabane, L.; Holbrook, A. Application of data mining techniques in pharmacovigilance. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003, 57, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adverse reaction | Male cases Number and % |

Female cases Number and % |

Male and female cases | % of all adverse reactions | Significance level (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure increased | 23 (53.5%) |

20 (46.5%) |

43 | 16.2% | 0.016410* |

| Dissociation/Dissociative disorder | 14 (33.3%) |

28 (66.6%) |

42 | 15.8% | 0.802393 |

| Suicidal ideation | 9 (34.6%) |

17 (65.4%) |

26 | 9.8% | 0.972193 |

| Anxiety | 5 (21.7%) |

18 (78.3%) |

23 | 8.7% | 0.198565 |

| Dizziness | 2 (11.1%) |

16 (88.9%) |

18 | 6.8% | 0.041125* |

| Completed suicide | 12 (70.6%) |

5 (29.4%) |

17 | 6.4% | 0.005334* |

| Drug ineffective | 5 (29.4%) |

12 (70.6%) |

17 | 6.4% | 0.685521 |

| Suicide attempt | 3 (21.4%) |

11 (78.6%) |

14 | 5.0% | 0.369206 |

| Loss of consciousness | 6 (46.1%) |

7 (53.8%) |

13 | 4.9% | 0.639931 |

| Hallucination | 4 (33.3%) |

8 (66.7%) |

12 | 4.5% | 0.925157 |

| Generalised tonic clonic seizure | 4 (50.0%) |

4 (50.0%) |

8 | 3.0% | 0.653024 |

| Diplopia | 2 (28.6%) |

5 (71.4%) |

7 | 2.6% | 0.977208 |

| Aggression | 0 (0%) |

5 (100%) |

5 | 1.9% | N.A. |

| Bradycardia | 4 (80.0%) |

1 (20%) |

5 | 1.9% | 0.112688 |

| Adverse reaction | Number and % of serious ICSRs in the Age Group of 18–64 Years (N = 210) |

Number and % of Serious ICSRs in the Age Group of 65–85 Years (N = 50) |

Significance level (P) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure increased | 26 (12.4%) |

17 (34.0%) |

0.000490* |

| Dissociation/ Dissociative disorder |

37 (17.6%) |

5 (10.0%) |

0.270536 |

| Suicidal ideation | 23 (10.9%) |

3 (6.0%) |

0.431401 |

| Anxiety | 20 (9.5%) |

3 (6.0%) |

0.608985 |

| Dizziness | 12 (5.7%) |

6 (12.0%) |

0.206359 |

| Completed suicide | 16 (7.6%) |

1 (2.0%) |

0.260073 |

| Drug ineffective | 11 (5.2%) |

6 (12.0%) |

0.155604 |

| Suicide attempt | 12 (5.7%) |

2 (4.0%) |

0.893348 |

| Loss of consciousness | 10 (4.8%) |

3 (6.0%) |

1.0 |

| Hallucination | 11 (5.2%) |

0 (0.0%) |

N.A. |

| Generalised tonic clonic seizure | 5 (2.4%) |

2 (4.0%) |

0.881104 |

| Diplopia | 6 (2.8%) |

1 (2.0%) |

0.881104 |

| Aggression | 4 (1.9%) |

1 (2.0%) |

0.596922 |

| Bradycardia | 4 (1.9%) |

1 (2.0%) |

0.596922 |

| Cases and % of ICSRs (0-85 years) (N = 265) |

Cases and % of ICSRs (18–64 years) (N = 210) |

Cases and % of ICSRs (65–85 Years) (N = 50) |

Male cases and % of total ICSRs (N = 265) |

Female cases and % of total ICSRs (N = 265) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases of death | 10 (3.8%) |

8 (3.8%) |

1 (2.0%) |

6 (2.3%) |

4 (1.5%) |

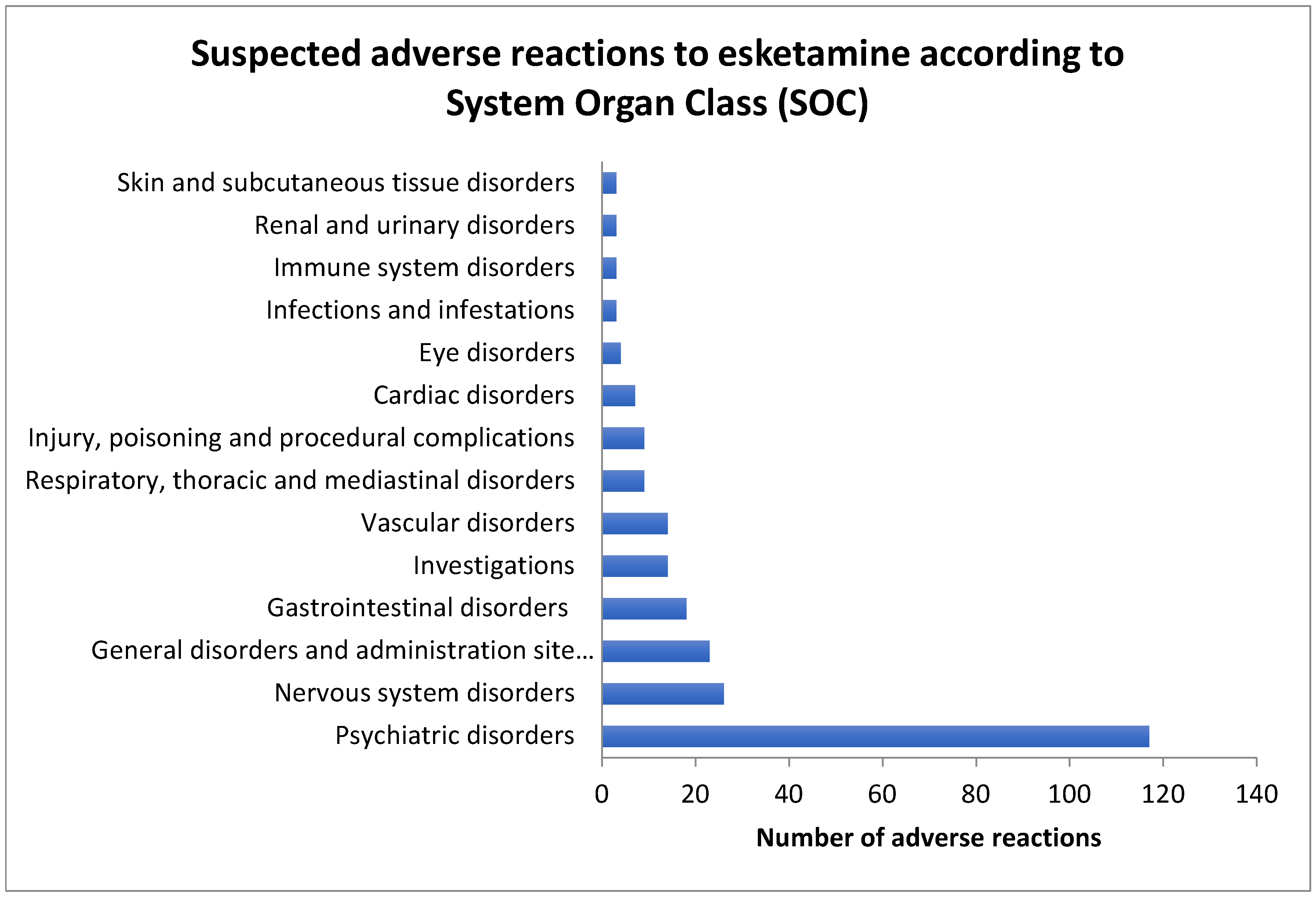

| SOC | SARs to esketamine |

All other SARs to esketamine |

SARs to fluoxetine | All other SARs to fluoxetine |

ROR and PRR esketamine vs fluoxetine (95% C.I.) |

SARs to venlafaxine | All other SARs to venlafaxine |

ROR and PRR esketamine vs venlafaxine (95% C.I.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric disorders | 117 | 148 | 318 | 919 | ROR: 2.28 PRR: 1.72 (1.74-3.00) |

573 | 1758 | ROR: 2.42 PRR: 1.80 (1.87-3.15) |

| Nervous system disorders | 26 | 239 | 371 | 695 | ROR: 0.20 PRR: 0.28 (0.13-0.31) |

793 | 1226 | ROR: 0.17 PRR: 0.25 (0.11-0.25) |

| Vascular disorders | 23 | 242 | 66 | 1000 | ROR: 1.44 PRR: 1.40 (0.88-2.36) |

156 | 1863 | ROR: 1.13 PRR: 1.12 (0.72-1.79) |

| Investigations | 18 | 247 | 119 | 947 | ROR: 0.58 PRR: 0.61 (0.35-0.97) |

246 | 1773 | ROR: 0.52 PRR: 0.56 (0.32-0.86) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 14 | 251 | 76 | 990 | ROR: 0.73 PRR: 0.74 (0.40-1.31) |

197 | 1822 | ROR: 0.51 PRR: 0.54 (0.30-0.90) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 14 | 251 | 240 | 826 | ROR: 0.19 PRR: 0.23 (0.11-0.33) |

492 | 1527 | ROR: 0.17 PRR: 0.22 (0.10-0.30) |

| Cardiac disorders | 9 | 256 | 96 | 970 | ROR: 0.35 PRR: 0.38 (0.18-0.71) |

258 | 1761 | ROR: 0.24 PRR: 0.26 (0.12-0.47) |

| Immune system disorders | 9 | 256 | 15 | 1051 | ROR: 2.46 PRR: 2.41 (1.06-5.69) |

11 | 2008 | ROR: 6.42 PRR: 6.23 (2.63-15.63) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 7 | 258 | 147 | 919 | ROR: 0.18 PRR: 0.20 (0.08-0.37) |

261 | 1758 | ROR: 0.18 PRR: 0.21 (0.08-0.39) |

| Adverse reaction | Esketamine Cases/not cases Total number of cases = 265 |

Fluoxetine Cases/not cases Total number of cases = 1066 |

Venlafaxine Cases/not cases Total number of cases = 2019 |

ROR and PRR of esketamine vs fluoxetine (95% C.I.) |

ROR and PRR of esketamine vs venlafaxine (95% C.I.) |

ROR and PRR of fluoxetine vs venlafaxine (95% C.I.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal ideation | 26/239 | 38/1028 | 41/1978 | ROR: 2.94 PRR: 2.75 (1.75-4.94) |

ROR: 5.25 PRR: 4.83 (3.15-8.73) |

ROR: 1.78 PRR: 1.75 (1.14-2.79) |

| Suicide attempt | 14/251 | 70/996 | 102/1917 | ROR: 0.79 PRR: 0.80 (0.44-1.43) |

ROR: 1.05 PRR: 1.04 (0.59-1.86) |

ROR: 1.32 PRR: 1.30 (0.96-1.81) |

| Completed suicide | 17/248 | 9/1057 | 13/2006 | ROR: 8.05 PRR: 7.60 (3.55-18.3) |

ROR: 10.58 PRR: 9.96 (5.08-22.04) |

ROR: 1.31 PRR: 1.31 (0.56-3.08) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).