Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

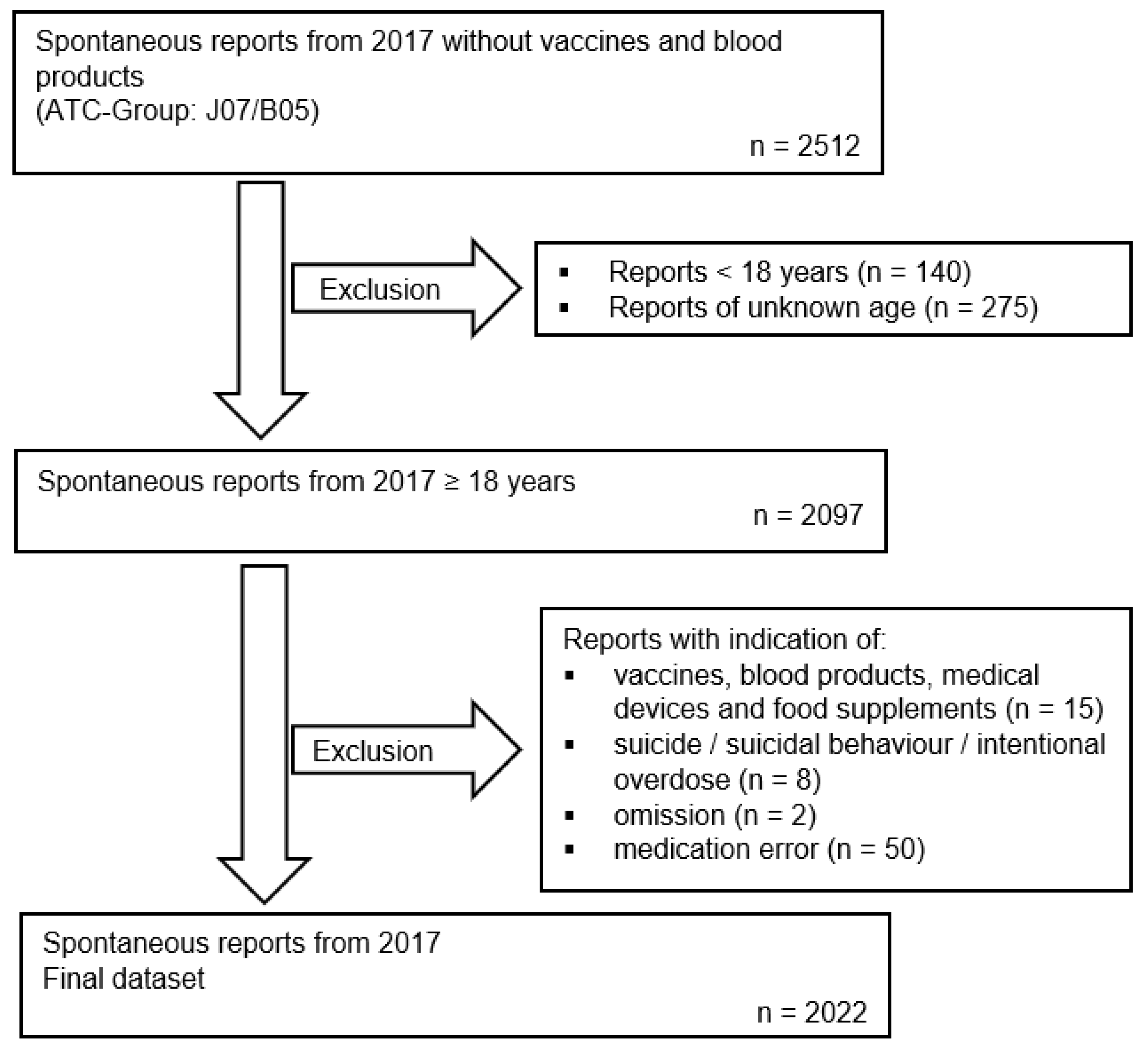

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Comparison Groups

2.2. Data Adjustment

2.3. Data Classification

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouvy, J.C.; Bruin, M.L.; Koopmanschap, M.A. Epidemiology of adverse drug reactions in Europe: a review of recent observational studies. Drug Saf. 2015, 38, 437–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durrieu, G.; Jacquot, J.; Mège, M.; Bondon-Guitton, E.; Rousseau, V.; Montastruc, F.; Montastruc, J.-L. Completeness of Spontaneous Adverse Drug Reaction Reports Sent by General Practitioners to a Regional Pharmacovigilance Centre: A Descriptive Study. Drug Saf. 2016, 39, 1189–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, P.C. Making the most of spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006, 98, 320–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laatikainen, O.; Sneck, S.; Turpeinen, M. Medication-related adverse events in health care-what have we learned? A narrative overview of the current knowledge. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2022, 78, 159–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazell, L.; Shakir, S.A.W. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2006, 29, 385–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundesärztekammer. (Muster-)Berufsordnung für die in Deutschland tätigen Ärztinnen und Ärzte. Available online: https://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/BAEK/Themen/Recht/_Bek_BAEK_Musterberufsordnung-AE.pdf. (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Bundes-Apothekerordnung: BApO, vom 05.06.1968 (Ausfertigungsdatum). In der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 19.07.1989 (BGBl. I S. 1478, 1842), die zuletzt durch Artikel 8 Absatz 3a des Gesetzes vom 27.09.2021 (BGBl. I S. 4530) geändert worden ist. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bapo/BJNR006010968.html (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft (AkdÄ). Bericht über unerwünschte Arzneimittelwirkungen. Available online: https://www.akdae.de/Arzneimittelsicherheit/UAW-Meldung/UAW-Berichtsbogen.pdf. (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Apotheker (AMK). Berichtsbogen-Formulare. Available online: https://www.abda.de/fuer-apotheker/arzneimittelkommission/berichtsbogen-formulare/. (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Schurig, A.M.; Böhme, M.; Just, K.S.; Scholl, C.; Dormann, H.; Plank-Kiegele, B.; Seufferlein, T.; Gräff, I.; Schwab, M.; Stingl, J.C. Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR) and Emergencies. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018, 115, 251–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Just, K.S.; Dormann, H.; Böhme, M.; Schurig, M.; Schneider, K.L.; Steffens, M.; Dunow, S.; Plank-Kiegele, B.; Ettrich, K.; Seufferlein, T.; et al. Personalising drug safety-results from the multi-centre prospective observational study on Adverse Drug Reactions in Emergency Departments (ADRED). Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020, 76, 439–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Just, K.S.; Dormann, H.; Schurig, M.; Böhme, M.; Steffens, M.; Plank-Kiegele, B.; Ettrich, K.; Seufferlein, T.; Gräff, I.; Igel, S.; et al. The phenotype of adverse drug effects: Do emergency visits due to adverse drug reactions look different in older people? Results from the ADRED study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 2144–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM). ATC-Klassifikation: ATC-Klassifikation mit definierten Tagesdosen DDD. Available online: https://www.bfarm.de/DE/Kodiersysteme/Klassifikationen/ATC/_node.html. (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Adel, N. Overview of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and evidence-based therapies. Am J Manag Care. 2017, 23, 259–65. [Google Scholar]

- Blijham, G.H. Prevention and treatment of organ toxicity during high-dose chemotherapy: an overview. Anticancer Drugs. 1993, 4, 527–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauppila, M.; Backman, J.T.; Niemi, M.; Lapatto-Reiniluoto, O. Incidence, preventability, and causality of adverse drug reactions at a university hospital emergency department. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021, 77, 643–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ujeyl, M.; Köster, I.; Wille, H.; Stammschulte, T.; Hein, R.; Harder, S.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Bleek, J.; Ihle, P.; Schröder, H.; et al. Comparative risks of bleeding, ischemic stroke and mortality with direct oral anticoagulants versus phenprocoumon in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018, 74, 1317–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss (G-BA). Nutzenbewertungsverfahren zum Wirkstoff Alirocumab. Available online: https://www.g-ba.de/bewertungsverfahren/nutzenbewertung/199/. (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss (G-BA). Nutzenbewertungsverfahren zum Wirkstoff Evolocumab. Available online: https://www.g-ba.de/bewertungsverfahren/nutzenbewertung/189/. (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- change.org. Beipackzettel der Hormonspirale vervollständigen. Available online: https://www.change.org/p/arzneimittelkommission-der-dt-ärzteschaft-und-bundesinstitut-f-arzneimittel-u-medizinprodukte-beipackzettel-der-hormonspirale-vervollständigen. (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Skovlund, C.W.; Mørch, L.S.; Kessing, L.V.; Lange, T.; Lidegaard, Ø. Association of Hormonal Contraception With Suicide Attempts and Suicides. Am J Psychiatry. 2018, 175, 336–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM). Rote-Hand-Brief zu hormonellen Kontrazeptiva: Neuer Warnhinweis zu Suizidalität als mögliche Folge einer Depression unter der Anwendung hormoneller Kontrazeptiva. 2019. Available online: https://www.bfarm.de/SharedDocs/Risikoinformationen/Pharmakovigilanz/DE/RHB/2019/rhb-hormonelle-kontrazeptiva.pdf. (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Postma, L.G.M.; Donyai, P. The cooccurrence of heightened media attention and adverse drug reaction reports for hormonal contraception in the United Kingdom between 2014 and 2017. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 1768–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langlade, C.; Gouverneur, A.; Bosco-Lévy, P.; Gouraud, A.; Pérault-Pochat, M-C.; Béné, J.; Miremont-Salamé, G.; Pariente, A. Adverse events reported for Mirena levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device in France and impact of media coverage. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019, 85, 2126–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hefner, G.; Hahn, M.; Toto, S.; Hiemke, C.; Roll, S.C.; Wolff, J.; Klimke, A. Potentially inappropriate medication in older psychiatric patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021, 77, 331–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, S.; Schmiedl, S.; Thürmann, P.A. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: the PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010, 107, 543–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchetti, G.; Lucchetti, A.L.G. Inappropriate prescribing in older persons: A systematic review of medications available in different criteria. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017, 68, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halli-Tierney, A.D.; Scarbrough, C.; Carroll, D. Polypharmacy: Evaluating Risks and Deprescribing. Am Fam Physician. 2019, 100, 32–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Earl, T.R.; Katapodis, N.D.; Schneiderman, S.R.; Shoemaker-Hunt, S.J. Using Deprescribing Practices and the Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions Criteria to Reduce Harm and Preventable Adverse Drug Events in Older Adults. J Patient Saf. 2020, 16, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahrni, M.L.; Azmy, M.T.; Usir, E.; Aziz, N.A.; Hassan, Y. Inappropriate prescribing defined by STOPP and START criteria and its association with adverse drug events among hospitalized older patients: A multicentre, prospective study. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0219898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andres, T.M.; McGrane, T.; McEvoy, M.D.; Allen, B.F.S. Geriatric Pharmacology: An Update. Anesthesiol Clin. 2019, 37, 475–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, S.; Ramani, R. Geriatric Pharmacology. Anesthesiol Clin. 2015, 33, 457–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavan, A.H.; Gallagher, P.F.; O’Mahony, D. Methods to reduce prescribing errors in elderly patients with multimorbidity. Clin Interv Aging. 2016, 11, 857–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, R.A. The epidemiology of polypharmacy. Clin Med (Lond). 2016, 16, 465–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, J.K.; Fouts, M.M.; Kotabe, S.E.; Lo, E. Polypharmacy as a risk factor for adverse drug reactions in geriatric nursing home residents. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006, 4, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Parish, A.L. Polypharmacy and Medication Management in Older Adults. Nurs Clin North Am. 2017, 52, 457–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohontsch, N.J.; Heser, K.; Löffler, A.; Haenisch, B.; Parker, D.; Luck, T.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Maier, W.; Jessen, F.; Scherer, M. General practitioners’ views on (long-term) prescription and use of problematic and potentially inappropriate medication for oldest-old patients-A qualitative interview study with GPs (CIM-TRIAD study). BMC Fam Practice. 2017, 18, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dormann, H.; Maas, R.; Eickhoff, C.; Müller, U.; Schulz, M.; Brell, D.; Thürmann, P.A. Der bundeseinheitliche Medikationsplan in der Praxis : Die Pilotprojekte MetropolMediplan 2016, Modellregion Erfurt und PRIMA. [Standardized national medication plan : The pilot projects MetropolMediplan 2016, model region Erfurt, and PRIMA]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz. 2018, 61, 1093–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, M.A.; Opitz, R.; Grandt, D.; Lehr, T. The federal standard medication plan in practice: An observational cross-sectional study on prevalence and quality. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020, 16, 1370–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amelung, S.; Bender, B.; Meid, A.; Walk-Fritz, S.; Hoppe-Tichy, T.; Haefeli, W.E.; Seidling, H.M. Wie vollständig ist der Bundeseinheitliche Medikationsplan? Eine Analyse bei Krankenhausaufnahme. [How complete is the Germany-wide standardised medication list ("Bundeseinheitlicher Medikationsplan")? An analysis at hospital admission]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2020, 145, e116–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Spontaneous reports n = 2022 | Adult n = 1156 (57.2%) |

Young-old n = 647 (32.0%) |

Old-old n = 219 (10.8%) |

ADRED n = 2215 |

Adult n = 731 (33.0%) |

Young-old n = 880 (39.7%) |

Old-old n = 604 (27.3%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61 [48;73] | 50 [38;57] | 72 [68;76] | 84 [81;87] | 73 [58;80] | 51 [38;58] | 74[70;77] | 84 [82;87] |

| Sex, male | 895 (44.3%) | 476 (41.2%) | 335 (51.8%) | 84 (38.4%) | 1115 (50.3%) | 360 (49.2%) | 495 (56.3%) | 260 (43.0%) |

| Sex, not known | 10 (0.5%) | 6 (0.5%) | 3 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | - | - | - | - |

| Number of suspected drugs | 1 [1;1] | 1 [1;1] | 1 [1;1] | 1 [1;1] | 1 [1;2] | 1 [1;2] | 2 [1;2] | 1 [1;2] |

| Number of taken drugs | 2 [1;5] | 1 [1;3] | 3 [1;6] | 4 [1;7] | 7 [3;10] | 3 [2;8] | 8 [5;11] | 8 [6;10] |

| Number of ADR per report/ case | 2 [1;3] | 2 [1;3] | 2 [1;3] | 2 [1;3] | 2 [1;4] | 2 [2;4] | 2 [1;4] | 2 [1;3] |

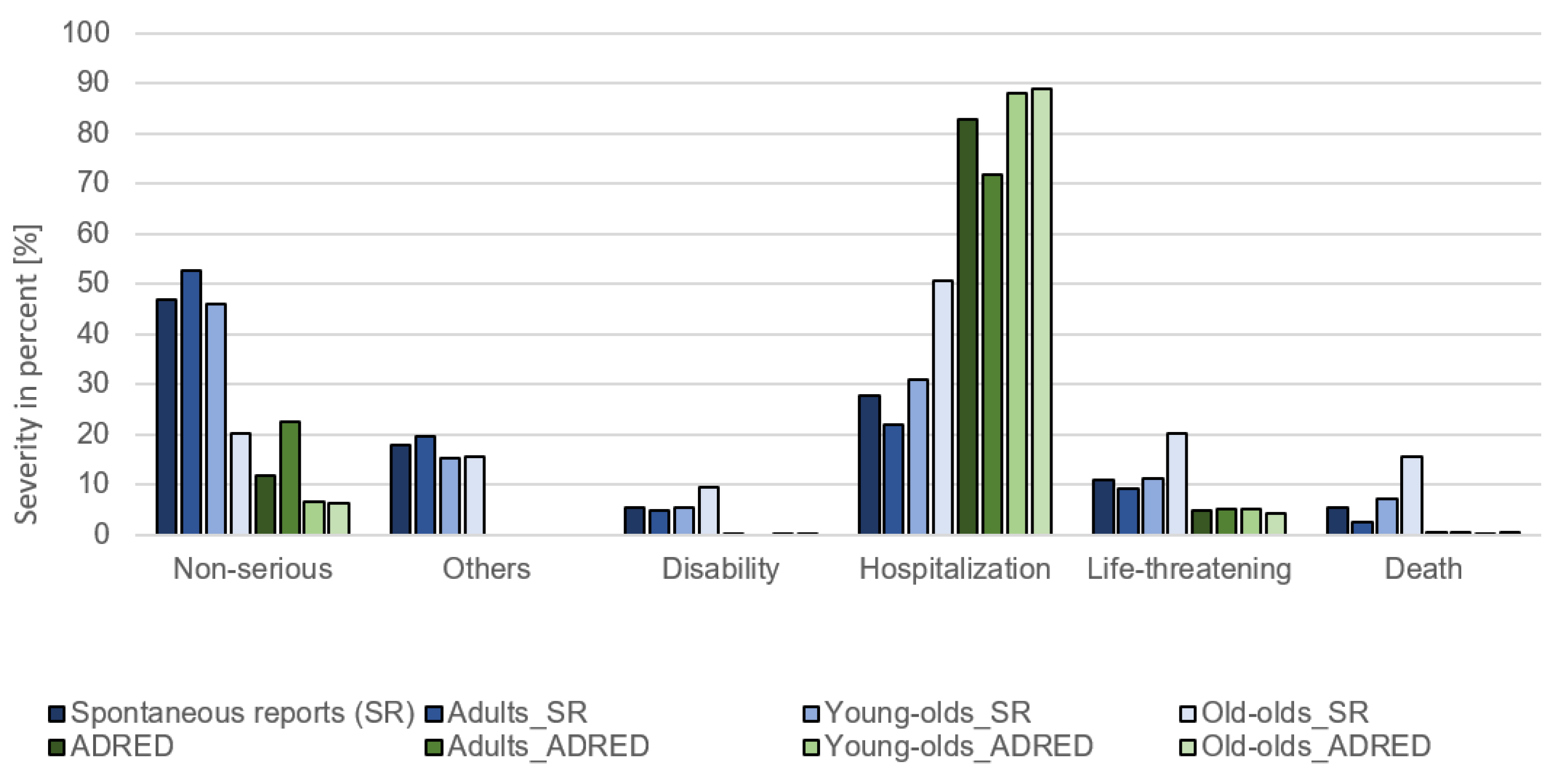

| Severity | Multiple choice possible2 | |||||||

| Non-serious | 950 (47.0%) | 609 (52.7%) | 297 (45.9%) | 44 (20.1%) | 261 (11.8%) | 165 (22.6%) | 58 (6.6%) | 38 (6.3%) |

| Others1 | 359 (17.8%) | 226 (19.6%) | 99 (15.3%) | 34 (15.5%) | - | - | - | - |

| Disability | 111 (5.5%) | 55 (4.8%) |

35 (5.4%) |

21 (9.6%) |

2 (0.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (0.1%) |

1 (0.2%) |

| Hospitalization | 562 (27.8%) | 252 (21.8%) | 199 (30.8%) | 111 (50.7%) | 1837 (82.9%) | 525 (71.8%) | 775 (88.1%) | 537 (88.9%) |

| Life-threatening | 223 (11.0%) | 106 (9.2%) | 73 (11.3%) | 44 (20.1%) | 107 (4.8%) |

37 (5.1%) |

45 (5.1%) | 25 (4.1%) |

| Death | 109 (5.4%) | 29 (2.5%) |

46 (7.1%) |

34 (15.5%) | 8 (0.4%) |

4 (0.5%) |

1 (0.1%) |

3 (0.5%) |

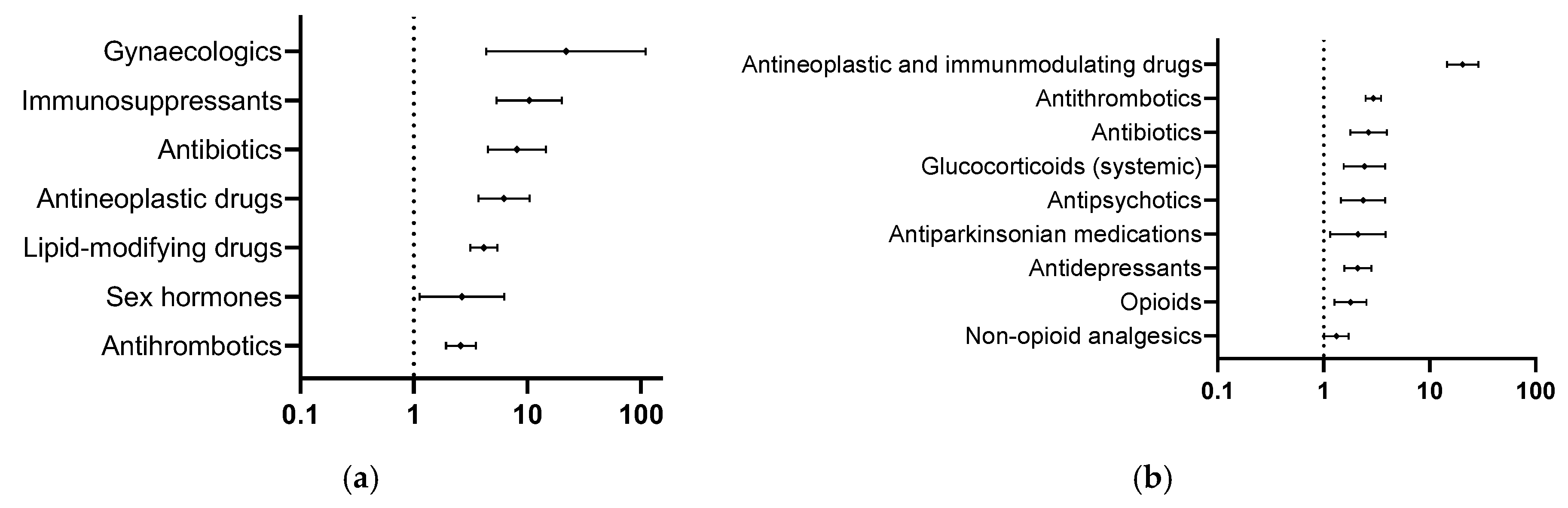

| Spontaneous reports (n = 2022) ∑suspected = 2278; ∑total = 5755; m = 29, z = 3.12 |

Suspected drugs (n) |

Proportion of all suspected drugs (%) |

Total drugs (n) |

Proportion of all total drugs (%) |

OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gynaecologics | 56 | 2.5 | 60 | 1.0 | 21.88 (4.34 – 110.24) |

| Immunosuppressants | 165 | 7.2 | 191 | 3.3 | 10.36 (5.34 – 20.13) |

| Antibiotics | 168 | 7.4 | 202 | 3.5 | 8.06 (4.46 – 14.59) |

| Antineoplastic drugs | 179 | 7.9 | 226 | 3.9 | 6.22 (3.71 – 10.45) |

| Lipid-modifying drugs | 483 | 21.2 | 696 | 12.1 | 4.12 (3.14 – 5.42) |

| Sex hormones | 36 | 1.6 | 57 | 1.0 | 2.64 (1.12 – 6.25) |

| Antithrombotics | 296 | 13.0 | 486 | 8.4 | 2.58 (1.91 – 3.50) |

|

ADRED study (n = 2215) ∑suspected = 3985; ∑total = 15948; m = 28, z = 3.12 |

|||||

| Antineoplastic and immunomodulating drugs | 591 | 14.8 | 692 | 4.3 | 20.45 (14.54 – 28.77) |

| Antithrombotics | 763 | 19.1 | 1656 | 10.4 | 2.94 (2.49 – 3.47) |

| Antibiotics | 118 | 3.0 | 254 | 1.6 | 2.65 (1.78 – 3.95) |

| Glucocorticoids (systemic) | 87 | 2.2 | 196 | 1.2 | 2.43 (1.54 – 3.82) |

| Antipsychotics | 77 | 1.9 | 176 | 1.1 | 2.36 (1.46 – 3.81) |

| Antiparkinsonian medications | 46 | 1.2 | 112 | 0.7 | 2.11 (1.15 – 3.84) |

| Antidepressants | 196 | 4.9 | 483 | 3.0 | 2.10 (1.57 – 2.83) |

| Opioids | 129 | 3.2 | 349 | 2.2 | 1.79 (1.26 – 2.54) |

| Non-opioid analgesics | 208 | 5.2 | 687 | 4.3 | 1.32 (1.01 – 1.72) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).