1. Introduction

Bacterial panicle blight (BPB) of rice has become a critical global threat, severely impacting rice production in many major rice-growing regions [

1]. The incidence and economic losses due to BPB are expected to rise with climate change and increasing temperatures [

2]. The disease can be caused by two bacteria,

Burkholderia gladioli and

Burkholderia glumae [

3]. The version of the disease caused by

B. glumae is one of the most devastating seed-borne bacterial diseases affecting rice production worldwide [

4]. In contrast,

B. gladioli are typically less virulent and not as commonly found as

B. glumae [

3].

B. glumae was first identified in Japan in 1956 as the causal agent of rice grain rot and seedling blight [

5]. BPB has been subsequently recorded worldwide in all areas that cultivate rice, including Asia, Africa, and Central and South America [

2,

4,

6]. Recent studies in Bangladesh confirmed that

B. gladioli and

B. glumae are responsible for significant BPB outbreaks, with

B. gladioli being the dominant species [

1,

7]. The disease produces several forms of damage, with grain spotting, rot, and panicle blight being the most significant, and can cause yield losses of up to 75% [

3,

6]. BPB is characterized by upright, straw-colored panicles with florets displaying a darker base and a distinctive reddish-brown marginal line separating necrotic and healthy tissue. Se verely affected panicles undergo grain abortion before kernel filling, resulting in complete loss of grain development. The upright posture of affected panicles, caused by the absence of grain fill, is a key diagnostic feature distinguishing BPB from other rice diseases [

3].

Several biochemical, physiological, and pathological techniques have historically been used to identify and characterize plant-pathogenic

Burkholderia species [

8]. Molecular methods, ranging from conventional Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for the detection of

Burkholderia species in seed lots and infected tissues to real-time quantitative PCR for sensitive pathogen identification and DNA quantification both in culture and

in planta, represent the most accurate and sensitive approaches for diagnosing BPB pathogens [

9,

10,

11]. Real-time reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) is a highly sensitive and effective technique for quantifying bacterial gene expression, and it has been extensively used to investigate the regulation of virulence genes [

12].

A variety of virulence factors influence the pathogenicity of

B. glumae and

B. gladioli. Toxoflavin, lipase (which is encoded by genes

lipA and

lipB), polygalacturonase (encoded by genes

pehA and

pehB), flagellar motility, and the Hrp-type III secretion system (T3SS) are essential for virulence [

13,

14].

B. glumae generates the phytotoxin toxoflavin [1,6-dimethylpyrimido[5,4-

e]-1,2,4-triazine-5,7(1

H,6

H)-dione], a yellow pigment that plays a vital role in pathogenicity [

15,

16]. Toxoflavin biosynthesis in

B. glumae initiates at temperatures above 30 °C and peaks at 37 °C [

17]. The tox operons,

toxABCDE and

toxFGHI, are implicated in toxoflavin biosynthesis and transport, respectively [

15]. Toxoflavin biosynthesis is controlled by quorum sensing and N-octanoyl homoserine lactone C8-HSL, which is produced by TofI and detected by the receiver TofR, which facilitates the recruitment of the transcriptional activators ToxJ and ToxR to the relevant promoters of toxoflavin biosynthesis genes [

18]. In

B. glumae, lipase also contributes to pathogenicity.

LipA is the primary extracellular lipase and a key virulence factor [

19]. LipA stability is supported by the activity of a second gene,

lipB, which is involved in

lipA expression and is necessary for LipA stability because it protects it from proteolytic degradation [

19,

20]. Flagella-mediated motility is a key virulence trait in pathogenic bacteria, as it allows them to move toward their target within the host, giving them an advantage during the initial colonization stages [

21]. Furthermore, global regulators like H-NS and the cAMP–CAP complex, as well as environmental cues including temperature, osmotic pressure, pH, and quorum-sensing signals, precisely regulate flagellar activity [

22,

23]. The pathogenicity of soft-rot bacteria is mainly attributed to pectinolytic enzymes such as PehA, which break down plant cell wall components [

24,

25]. PehA strongly promotes the breakdown of onion tissue by

Burkholderia species, resulting in maceration [

26]. Despite the identification and characterization of the type III-secreted effectors PehA and PehB in

B. glumae, it is still unknown how precisely they contribute to disease, possibly because of their comparable activities [

13]. Finally, the Hrp (hypersensitive response and pathogenicity) type III secretion system is essential for the pathogenicity of numerous plant pathogenic bacteria [

27]. In specific plant pathogenic bacteria, hrp genes play a crucial role in inducing disease in susceptible plants while triggering a hypersensitive response in resistant plants [

28].

We still lack a comprehensive understanding of toxoflavin biosynthesis, lipase and polygalacturonase enzymatic activities, and flagellar virulence gene regulation in B. glumae and B. gladioli. Comparative analysis of homologous gene clusters across both species can enhance our understanding of their pathogenic strategies. In addition, our current understanding of the prevalence of the BPB disease caused by B. glumae and B. gladioli in rice in Bangladesh is scanty, and ongoing environmental changes are facilitating the spread of the disease throughout the country, highlighting the need for focused research. In this study, we characterized 19 B. gladioli and a single B. glumae isolates across 20 districts, including 4 major rice-growing districts of Bangladesh, by integrating phenotypic assays and genomic comparisons. Phenotypic characterization included quantification of toxoflavin, lipase and polygalacturonase activities, and motility, while genomic analyses encompassed BLASTp comparisons and phylogenetic analyses of orthologous regions for toxin biosynthesis (toxA–R), lipase (lipA/lipB), polygalacturonase (pehA/pehB), motility-related gene clusters (cheA, cheB, cheD, cheR, cheW, cheY, cheY1, cheZ, flhA, flhB, flhC, flhD, flhG, fliA, fliC, fliD, tsr, motA, motB). Moreover, we quantified the expression levels of 17 key virulence-linked genes, including toxA–R, lipA/lipB, pehA/pehB, and flhC/flhF, by real-time RT-qPCR in two representative highly virulent isolates: B. glumae BD_21g and B. gladioli BDBgla132A. By correlating phenotypic variation with genomic diversity, we provide novel insights into BPB pathogenicity and lay the groundwork for targeted management strategies in Bangladesh.

4. Discussion

A comprehensive investigation of

Burkholderia species in association with bacterial panicle blight (BPB) of rice in Bangladesh is presented. A total of 51 bacterial strains were isolated from eight rice varieties collected across 20 districts during the 2022–2023 cropping season. S-PG and KBA media were suitable for preliminary screening, based on colony morphology and pigment formation, as described in ref. [

8]. Two distinct colony types were observed: Type A, which formed reddish-brown colonies, and Type B, which showed a purple hue (

Figure 2A,B). These characteristics were consistent with those previously described in ref. [

46], reinforcing the importance of these visual traits in the early stages of identification. Further molecular identification using the PCR designed to amplify the

gyrB gene [

9] enabled accurate species determination, producing amplicons of 479 and 529 bp for

B. gladioli and

B. glumae, respectively (

Figure 2C). PCR-based methods are standard procedures to distinguish between closely related phytopathogens [

9], and newer techniques, including real-time PCR and real-time RT-qPCR, provide greater diagnostic sensitivity [

9,

10,

11,

12]. PCR-based detection of species revealed a marked predominance of

B. gladioli (46/51) isolates with only 5 representing

B. glumae. This dominance of

B. gladioli is in accord with recent patterns found across South and Southeast Asia, where

B. gladioli is becoming the most common BPB-causing pathogen, in contrast with previous reports in Japan and the Americas, where

B. glumae was the primary causative agent [

2,

3].

B. gladioli has also been found in asymptomatic rice seeds in China [

47] and is associated with diseases in other crops, such as tomato, eggplant, pepper, and sunflower in Korea. The relatively low occurrence of

B. glumae detected in our survey may be due to agroecological differences or variation in host cultivars in Bangladesh. Overall, the evidence presented here supports the emerging importance of

B. gladioli as a significant component of the BPB disease complex and highlights the need for reassessing the prevalence of the pathogen in other rice-growing endemic areas.

Pathogenicity tests confirmed that all studied

Burkholderia strains produced BPB symptoms in both rice seedlings and panicles (

Figure 3A,B), and that

the B. glumae isolate was more virulent than the

B. gladioli isolates on both rice tissues, as shown in

Table 1. These findings are consistent with previous studies from Japan and Taiwan, which have found that rice plants grown in kernels at the boot or heading stages are more susceptible than seedlings at the four-leaf stage [

48,

49]. Our onion assay tests demonstrated that all virulent isolates caused substantial tissue maceration (

Figure 4A,B), with their ability to cause onion maceration being highly correlated with rice panicle disease severity (

R² = 0.69;

Figure 4C), suggesting the surrogate value of the assay for rice pathogenicity. This result is in agreement with those of previous studies on

Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) members, such as

Burkholderia cepacia and

Burkholderia cenocepacia, which cause soft rot symptoms in onion bulbs [

50,

51]. Similarly, Karki et al. [

52] found a strong correlation between the virulence of

B. glumae on onion bulbs and its virulence on rice panicles, supporting the importance of this assay for strain pathotyping. Given its simplicity, ease of replication, and potential expandability, the onion bulb scale assay has emerged as a novel method for

Burkholderia pathogenicity testing.

B. glumae synthesizes two main isomeric toxins, namely toxoflavin and fervenulin [

15]. As a phytopathogen

, B. glumae secretes toxoflavin, which impedes the development of rice seedlings and affects the growth of both roots and shoots. Moreover, in the grain-rot phase, it contributes to the emergence of chlorosis primarily on the panicles [

53,

54]. The production of toxoflavin is significantly temperature-dependent, beginning at 30 °C and reaching its maximum at 37 °C [

17]. The inability of certain

B. glumae strains to produce toxoflavin prevents them from causing chlorosis, demonstrating the toxin’s critical role in symptom development [

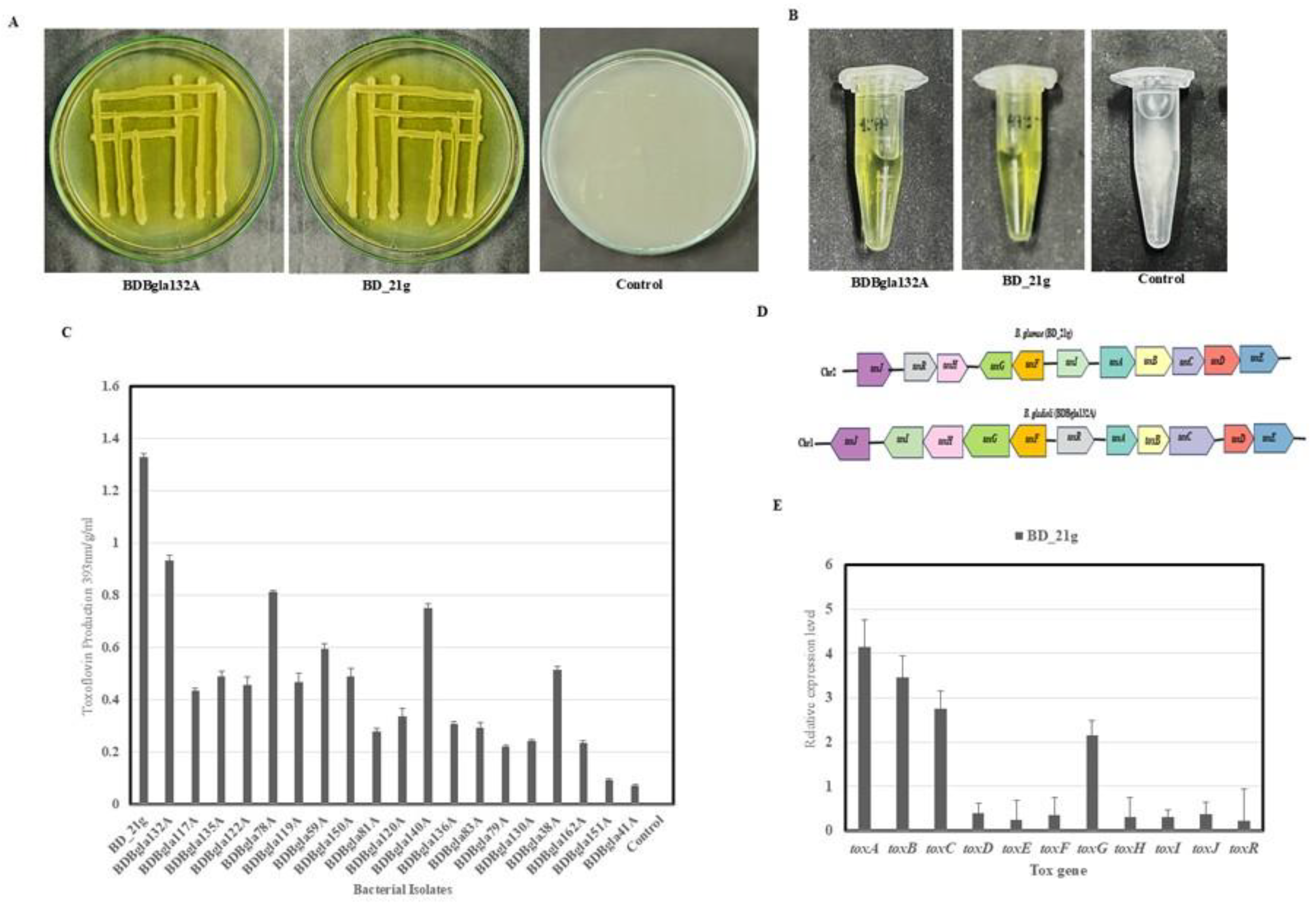

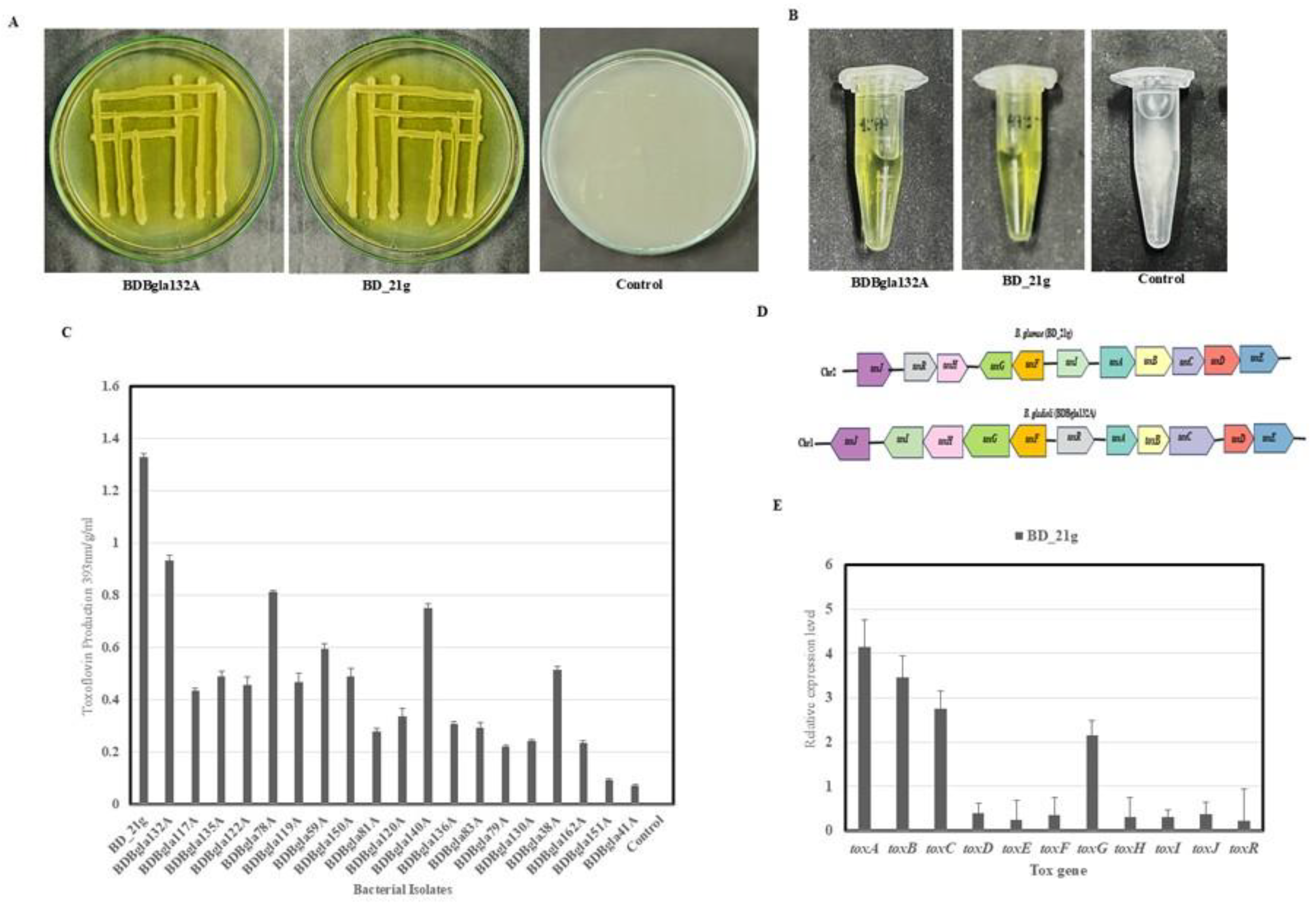

16]. Our phenotypic investigation of 20 isolates showed significant inter-strain variation in toxoflavin production, pigment patterns, and toxin quantification for the virulent isolates that we tested (

Figure 5A–C). This discrepancy could stem from differences in susceptibility to environmental signals among biosynthetic complexes, or from substantial differential regulation of quorum-sensing circuits such as TofR and TofI [

22]. The distinction in virulence strategies between the

B. glumae BD_21g and

B. gladioli BDBgla132A strains is further highlighted by comparative gene expression. In BD_21g, toxoflavin biosynthesis genes exhibit higher levels of expression than in BDBgla132A (

Figure 5E). Among these,

toxA exhibited the highest overall overexpression (4.15-fold), suggesting that a ToxA-type virulence strategy is present in that strain (

Figure 5E). In

B. glumae, the

toxABCDE operon encodes the enzymatic machinery for toxoflavin biosynthesis, while the

toxFGHI operon encodes transporters that facilitate toxoflavin secretion [

15,

53,

54]. Quorum sensing regulates the biosynthesis of toxoflavin in

B. glumae through N-octanoyl homoserine lactone, which is synthesized by the TofI enzyme and recognized by the TofR receptor. Quorum sensing regulates toxoflavin production in B. glumae through N-octanoyl homoserine lactone, which is synthesized by the TofI enzyme and recognized by the TofR receptor C8-HSL TofR activation leads to the expression of the toxoflavin production-associated transcriptional regulators ToxJ and ToxR [

23]. Notably, minimal differences in the expression of toxJ and toxR among strains, despite high toxA expression in BD_21g, suggest that this strain may employ non-canonical regulatory mechanisms beyond the classical TofI/TofR quorum-sensing pathway. A recent study has revealed that B. glumae possesses multiple alternative regulatory circuits for toxoflavin biosynthesis, including the regulatory gene tofM and quorum sensing-independent modulation pathways controlled by QsmR as well as pH-dependent regulation mediated by the membrane protein DbcA [

55,

56]. These results suggest that BD_21g may employ multiple regulatory mechanisms (such as temperature-dependent, QsmR-mediated, and pH-dependent regulation) to produce toxoflavin in a manner that is distinct from other virulent

B. glumae strains, which are mainly mediated by the canonical quorum sensing system for pathogenesis. To further investigate the diversity of toxin biosynthetic gene expression in

Burkholderia species, we evaluated the presence and sequence identity of the tox operons between the genomes of

B. glumae BD_21g and

B. gladioli BDBgla132A (

Table 2). The biosynthetic genes (

toxABCDE) showed particularly high identity:

toxB exhibited the highest identity at 98.11%, followed by

toxC at 97.51%. The transport genes (

toxFGHI) maintained high sequence identity, with

toxH reaching 97.48%. This elevated sequence identity indicates that the core toxoflavin biosynthetic and transport machinery remains functionally equivalent between

B. gladioli and

B. glumae, supporting the critical role of this toxin in plant pathogenesis [

15,

52].

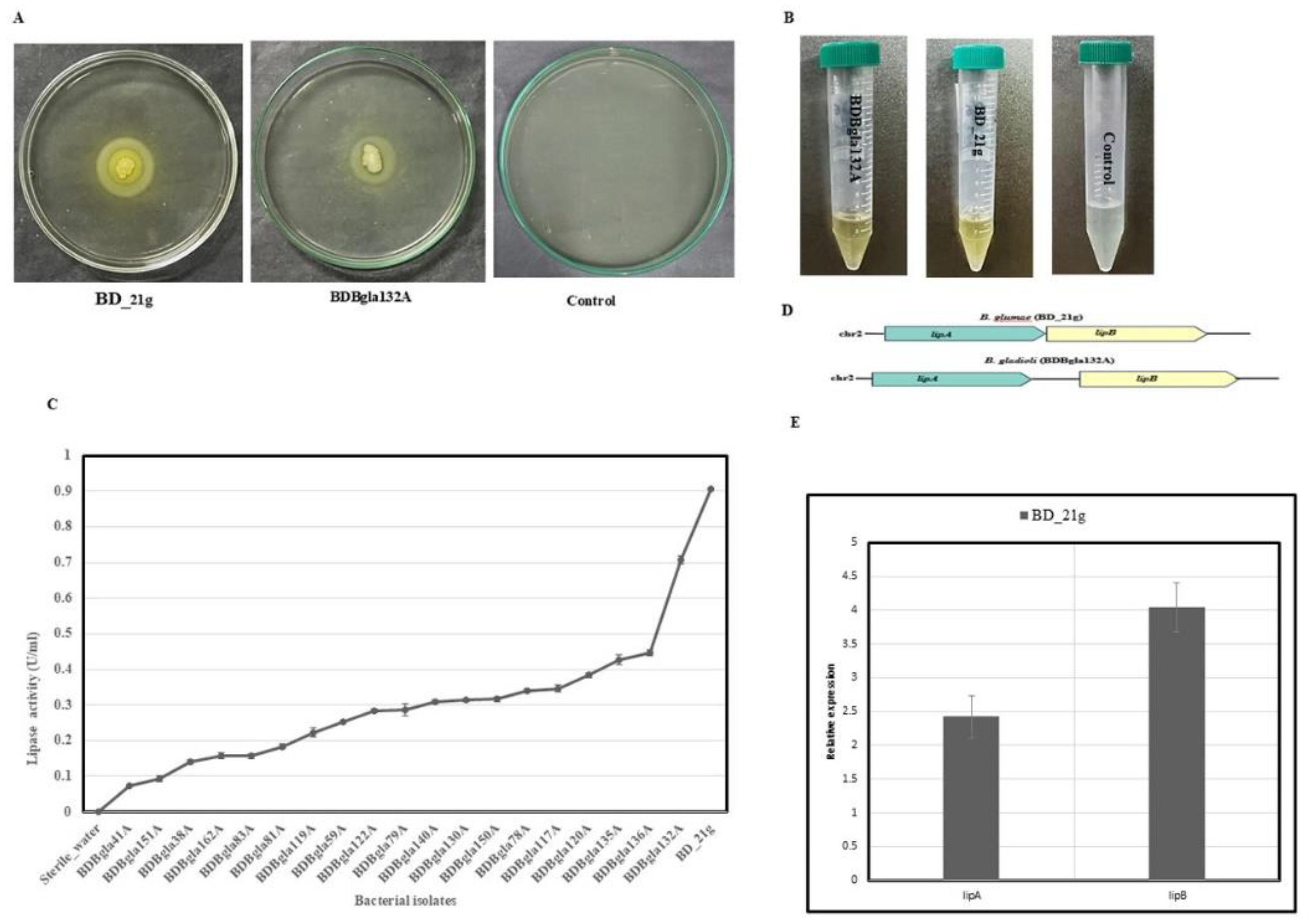

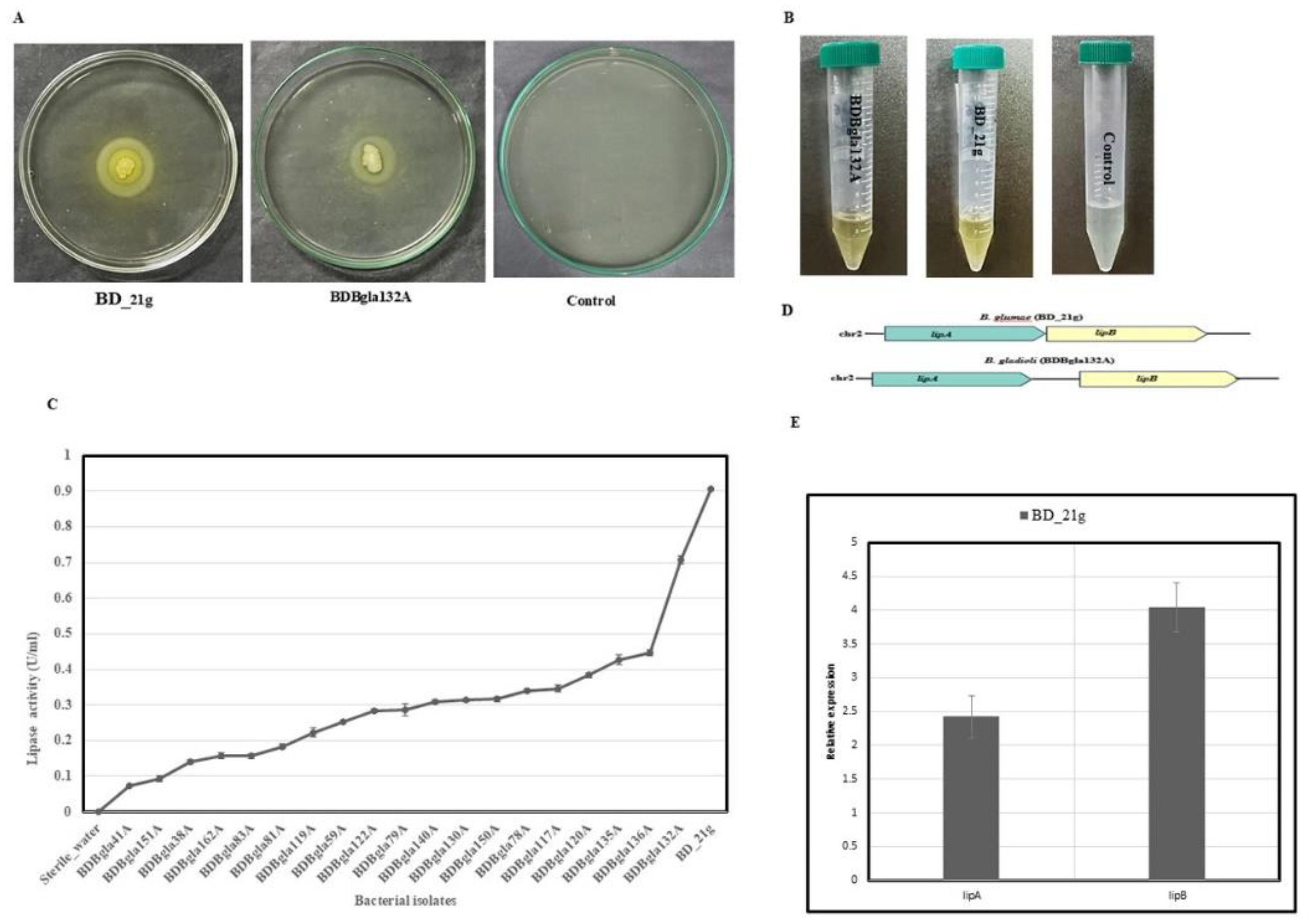

According to our lipase activity assays, all studied

Burkholderia strains produced lipase, with

B. glumae BD_21g and

B. gladioli BDBgla132A exhibiting significantly higher activity (

Figure 6A–C). Real time RT-qPCR analyses revealed that BD_21g exhibits increased expression of lipase-encoding genes over

B. gladioli BDBgla132A. The expression of

lipA and

lipB genes was elevated by 2.4- and 4-fold, respectively, indicating an active lipid-hydrolysis process that breaks down host membranes to release nutrients [

55]. These findings are consistent with prior studies that implicated mutations in the

lipAB operon promoter region in elevated lipase expression and secretion [

57].

Sequence comparison of the lipase-encoding genes (lipA/lipB) between B. gladioli BDBgla132A and B. glumae BD_21g uncovered variable levels of conservation (Table 2):

lipA maintained substantial identity at 88.55% while

lipB exhibited lower sequence identity at 80.71%. Functional extracellular activity was confirmed by in vitro lipase assays with model substrates, indicating that

lipA and

lipB encode secreted enzymes capable of hydrolyzing lipid esters and supporting their nutrient acquisition role [

58]. Overall, these data support the importance of lipase as a multifaceted virulence factor, with conserved gene sequences and confirmed extracellular enzyme activity, making it a potent therapeutic target for disease control strategies.

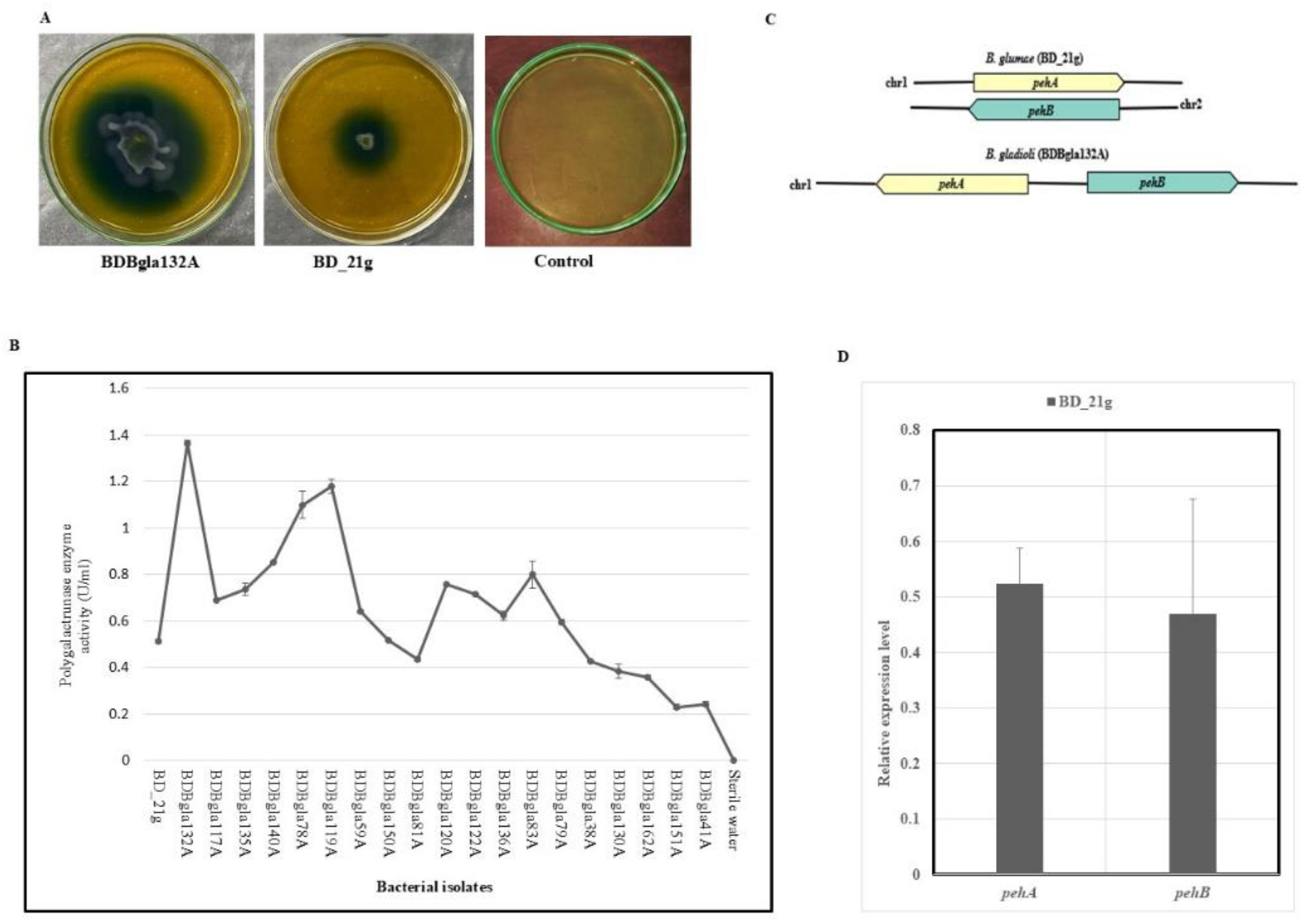

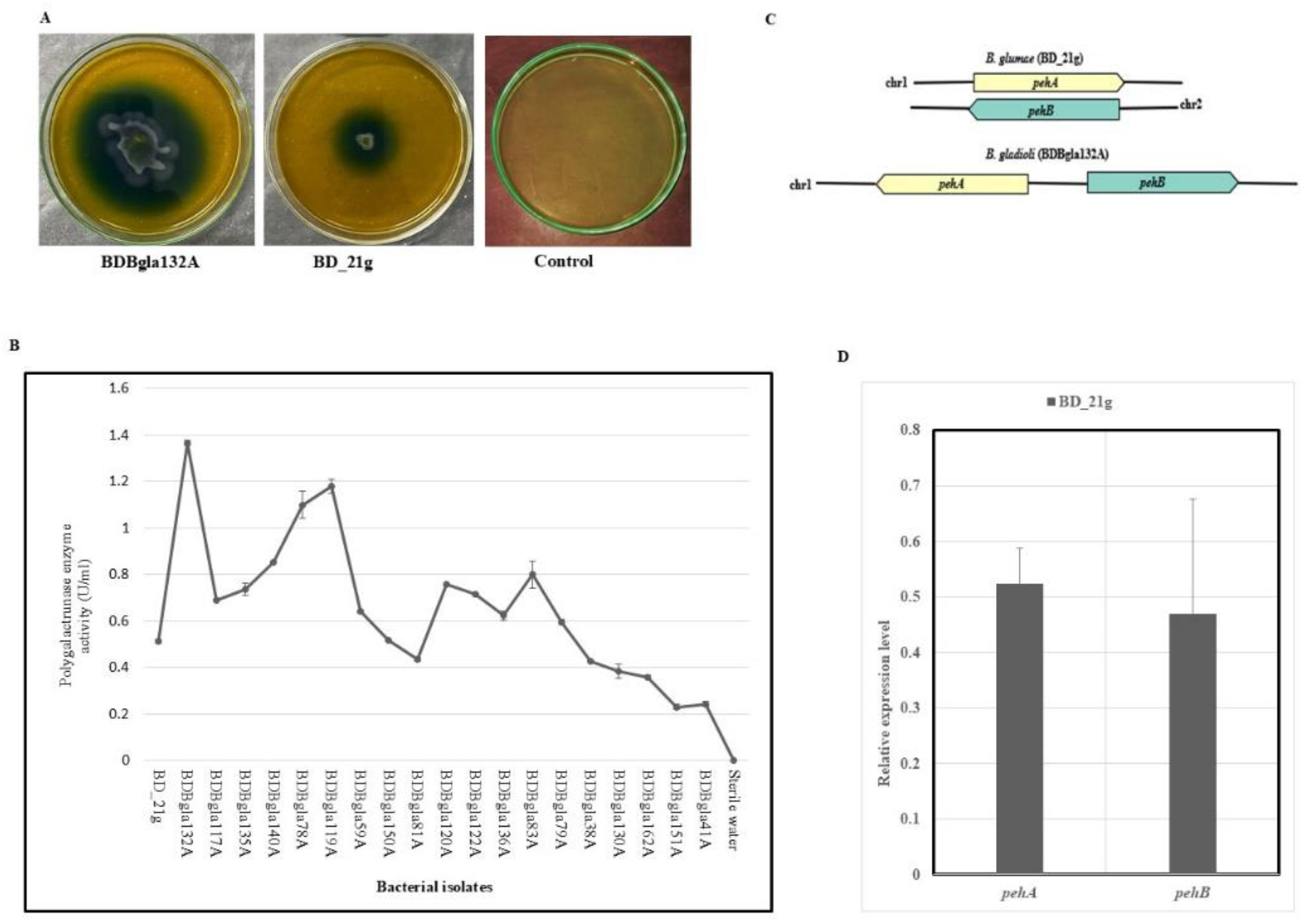

All the

Burkholderia strains analyzed with a qualitative pectate gel assay were confirmed to secrete polygalacturonase, while quantification using the Bernfeld method showed that polygalacturonic acid induced polygalacturonase activity (

Figure 7A–B), consistent with the enzyme’s function of degrading this major structural component of plant cell walls [

39,

41]. The chromosomal localization of

peh genes differed among the individual species. The

pehA gene of

B. gladioli was found to be plasmid-borne [

59], while in

B. glumae polygalacturonase-encoding genes localize to the chromosomes [

13]. This distinction might reflect different strategies for maintaining virulence factors. RT-qPCR analysis showed that

pehA and

pehB transcript levels in BD_21g were 1.9-fold and 2.0fold lower than in BDBgla132A (

Figure 7D), suggesting differential regulation of polygalacturonase production in response to plant cell wall degradation requirements [

26,

59]. Comparative sequence analysis of

B. glumae BD_21g and

B. gladioli BDBgla132A revealed that polygalacturonase-encoding genes (

pehA/pehB) shared moderate to high sequence identity between both strains (

Table 2):

pehA displayed 84.53%, whereas

pehB exhibited greater identity (87.35%). Polygalacturonases encoded by

pehA/pehB degrade plant cell wall pectin and represent established virulence factors in

Burkholderia-mediated host tissue maceration [

13]. The similarity of these genes across both species with substantial sequence identity underscores their pivotal role in plant tissue maceration and disease progression. These findings have implications for their virulence system and host specificity. It would be interesting to explore further how environmental conditions, particularly temperature, pH, and pectin concentration, influence

pehA and

pehB expression in both species. In addition, determining the exact contribution of polygalacturonase activity to virulence across multi-host plants would be key.

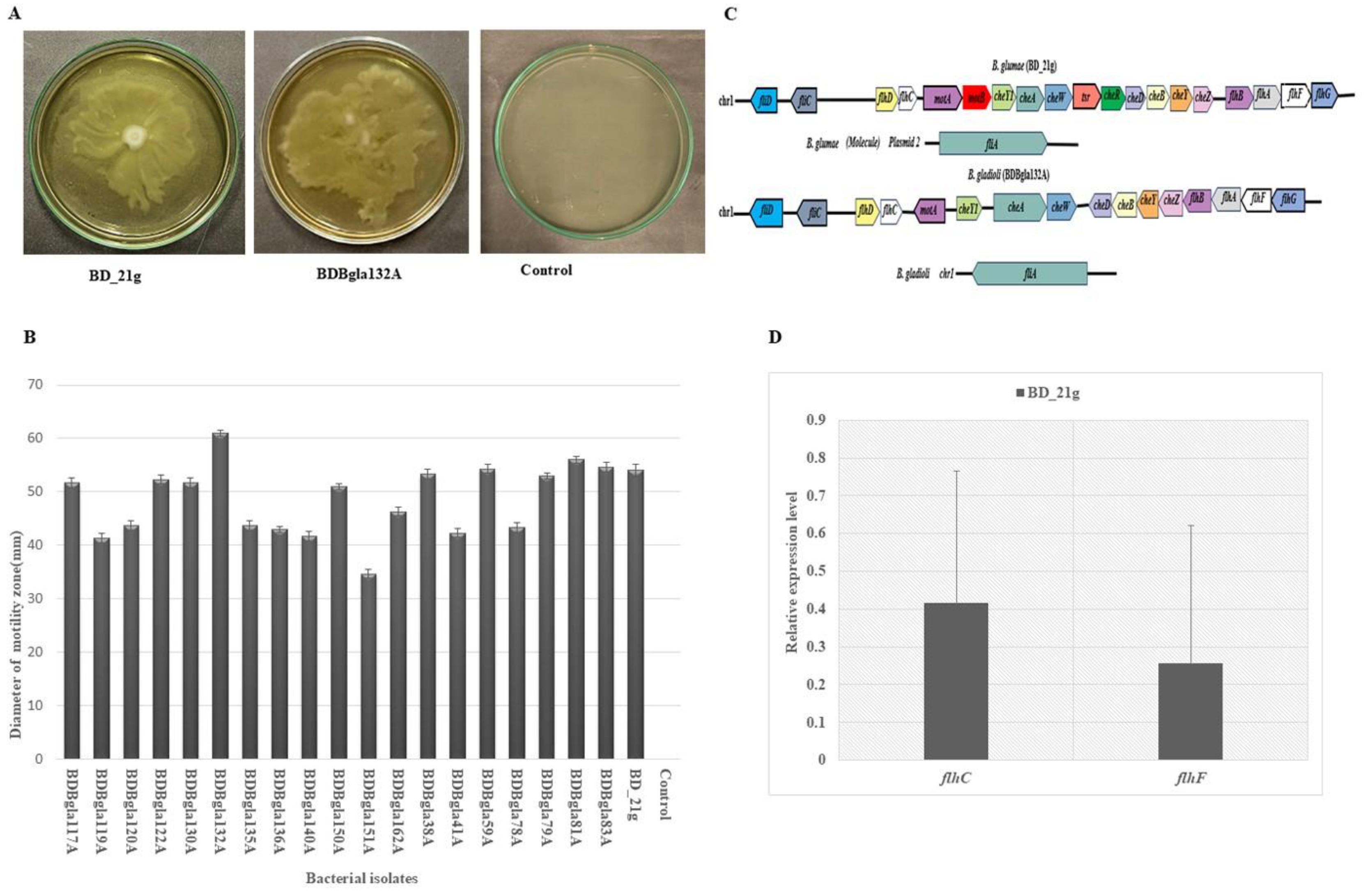

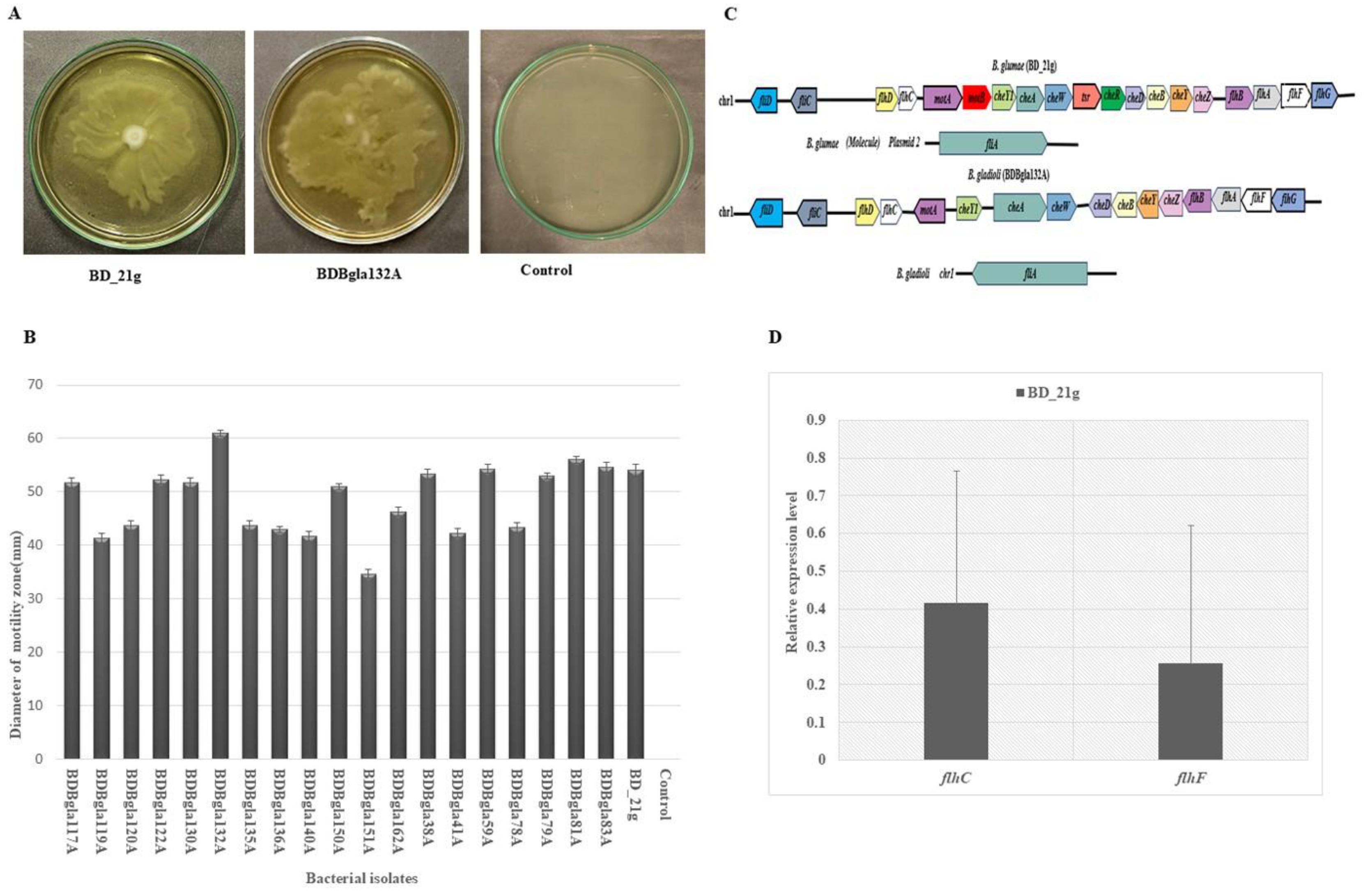

All studied

Burkholderia strains exhibited swarming motility on 0.5% semi-solid LB medium. However, the motility capacity was strain-dependent, with BDBgla132A displaying the highest motility, followed by BDBgla136A, BDBgla136A, BDBgla138A, and BD_21g (

Figure 8A–

B). In plant-pathogen interactions, swarming motility is vital for surface colonization and, potentially, systemic dissemination during infection [

15,

23]. In

B. glumae, swarming motility (a flagella-driven social movement of differentiated cells) is regulated by quorum sensing and acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) signaling molecules and requires the use of rhamnolipid to spread the cells on an agar surface [

60]. Quantitative PCR revealed that flagellar regulatory genes

flhC and

flhF were expressed at 2.4- and 3.8-fold lower levels in BD_21g relative to BDBgla132A, aligning with the enhanced motility phenotype observed in the latter strain. We hypothesize that different regulators affect this phenotype. Chemotaxis and flagellar genes displayed complex sequence identity patterns with functional implications for motility and virulence (

Table 2). Core chemotaxis genes (

cheA, cheB, cheD, cheW, cheY, cheY1 and

cheZ) showed high identity (80.80–97.22%), while the

cheR deletion in

B. gladioli BDBgla132A suggests divergent regulatory mechanisms. Flagellar biosynthesis genes (

flhA–flhG) exhibited high identity (84.39–96.72%), although

fliD displayed the lowest identity (66.92%). The absence of

motB and the chemotactic receptor (

tsr) in BDBgla132A, coupled with the retention of

motA (96.5%), indicates species-specific adaptations in flagellar function that may influence tissue colonization strategies. Our results align with a pan-genomic analysis of

B. gladioli, which reported considerable functional diversity in motility-associated genes [

58]. Motility systems may have evolved to occupy different ecological niches, but the precise role of swarming in BPB-related pathogenesis remains poorly understood. Mutant analyses and

in planta colonization studies will be required to determine whether differential flagellar gene organization directly influences virulence during rice infection.

To assess the functionality of the type III secretion system (T3SS), we performed hypersensitivity assays on tobacco leaves (

Nicotiana tabacum L.). All

Burkholderia isolates induced rapid necrotic lesions within 48 hours (

Figure 2A–C). The rapid development of necrotic lesions triggered by strains BDBgla132A (

Figure 2A) and BD_21g (

Figure 2B) within 48 hours indicates the functionality of an active type III secretion system (T3SS), confirming earlier reports on the critical requirement of hrp-encoded T3SS components for the delivery of effector proteins into host cells [

27]. The isolates’ ability to elicit a hypersensitive response (HR) aligns with their dual role in promoting disease in susceptible hosts and in activating plant resistance in resistant hosts, both of which are hallmark functions of intact hrp gene clusters [

28].

Figure 1.

Typical symptoms of bacterial panicle blight (BPB) of rice. (A) Lesion on the sheath, displaying a vertical grayish area with a dark reddish-brown border (arrow). (B, C) Panicle symptoms include straw-colored spikes with florets showing darker basal and reddish-brown marginal lines. (D) Field infections on a susceptible cultivar (Oryza sativa L. cv. Horidhan) showing heavily infected panicles that remain erect due to grain abortion.

Figure 1.

Typical symptoms of bacterial panicle blight (BPB) of rice. (A) Lesion on the sheath, displaying a vertical grayish area with a dark reddish-brown border (arrow). (B, C) Panicle symptoms include straw-colored spikes with florets showing darker basal and reddish-brown marginal lines. (D) Field infections on a susceptible cultivar (Oryza sativa L. cv. Horidhan) showing heavily infected panicles that remain erect due to grain abortion.

Figure 2.

Morphological and molecular identification of target bacterial isolates. (A) Colonies on S-PG medium showing distinct morphology. (B) Enlarged views of selected colonies indicated by arrows: Type A colonies are round with smooth edges and reddish-brown discoloration, and Type B colonies are round with a central purple reflection on a magenta background. (C) Detection of B. glumae and B. gladioli in infected rice panicles by PCR, with amplification of gyrB gene fragments of 479 bp and 529 bp, respectively.

Figure 2.

Morphological and molecular identification of target bacterial isolates. (A) Colonies on S-PG medium showing distinct morphology. (B) Enlarged views of selected colonies indicated by arrows: Type A colonies are round with smooth edges and reddish-brown discoloration, and Type B colonies are round with a central purple reflection on a magenta background. (C) Detection of B. glumae and B. gladioli in infected rice panicles by PCR, with amplification of gyrB gene fragments of 479 bp and 529 bp, respectively.

Figure 3.

Assessment of pathogenicity and hypersensitive response assays. (A) Virulence evaluation of leaf sheath in rice seedlings (Oryza sativa L. cv. Horidhan) scored as + (weak), ++ (moderate), +++ (severe), or 0 (non-pathogenic) (B) Disease severity (DS) on rice panicles using a 0–9 scale. (C) Hypersensitive response in Nicotiana tabacum leaves 48 h after infiltration with ~10⁸ CFU/mL of toxoflavin-producing strains; sterile water-infiltrated leaves showed no reaction. Arrows mark necrotic spots. .

Figure 3.

Assessment of pathogenicity and hypersensitive response assays. (A) Virulence evaluation of leaf sheath in rice seedlings (Oryza sativa L. cv. Horidhan) scored as + (weak), ++ (moderate), +++ (severe), or 0 (non-pathogenic) (B) Disease severity (DS) on rice panicles using a 0–9 scale. (C) Hypersensitive response in Nicotiana tabacum leaves 48 h after infiltration with ~10⁸ CFU/mL of toxoflavin-producing strains; sterile water-infiltrated leaves showed no reaction. Arrows mark necrotic spots. .

Figure 4.

Virulence of B. glumae and B. gladioli strains on onion bulb scales and their correlation to rice panicle disease severity. (A) Onion bulb scales were inoculated with bacterial suspensions (~5 × 10⁵ CFU/mL) and incubated at 30 °C for 48 h post-inoculation; different isolates exhibited varying degrees of tissue maceration compared to sterile water (which was used as control). (B) The area of tissue maceration for each strain was measured. (C) Correlation between onion scale tissue maceration and rice panicle disease severity with a linear regression line. All regression coefficients were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors from three biological replicates. Statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.4.1.

Figure 4.

Virulence of B. glumae and B. gladioli strains on onion bulb scales and their correlation to rice panicle disease severity. (A) Onion bulb scales were inoculated with bacterial suspensions (~5 × 10⁵ CFU/mL) and incubated at 30 °C for 48 h post-inoculation; different isolates exhibited varying degrees of tissue maceration compared to sterile water (which was used as control). (B) The area of tissue maceration for each strain was measured. (C) Correlation between onion scale tissue maceration and rice panicle disease severity with a linear regression line. All regression coefficients were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors from three biological replicates. Statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.4.1.

Figure 5.

Toxoflavin production and molecular features of B. glumae and B. gladioli strains. (A) Toxoflavin phenotypes on King’s B agar after incubation for 48 h at 37 °C; all Burkholderia strains produced pigment while the negative control did not (B) Toxoflavin pigment extraction via chloroform following bacterial cell removal. (C) Spectrophotometric measurement of toxoflavin at 393 nm. (D) Schematic representation of the toxin-producing gene clusters in two bacterial strains, B. glumae (strain BD_21g) and B. gladioli (strain BDBgla132A). In B. glumae (chromosome 2) the tox operon comprises the following genes in sequential order: toxJ, toxR, toxH, toxG, toxF, toxI, toxA, toxB, toxC, toxD, and toxE. In contrast, in B. gladioli (chromosome 1), the same genes are similarly arranged but with toxR relocated downstream of toxF. (E) Relative expression of the toxA–toxR genes was quantified by qPCR, normalizing to 16S rRNA and setting B. gladioli (BDBgla132A) expression to 1 for the control strain, whereas B. glumae (BD_21g) served as the test strain. Error bars represent standard errors from three independent biological replicates. All differences between groups were statistically significant at P < 0.05, as determined by the Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) and Student’s t-tests, which we conducted using the R software (version 4.4.1).

Figure 5.

Toxoflavin production and molecular features of B. glumae and B. gladioli strains. (A) Toxoflavin phenotypes on King’s B agar after incubation for 48 h at 37 °C; all Burkholderia strains produced pigment while the negative control did not (B) Toxoflavin pigment extraction via chloroform following bacterial cell removal. (C) Spectrophotometric measurement of toxoflavin at 393 nm. (D) Schematic representation of the toxin-producing gene clusters in two bacterial strains, B. glumae (strain BD_21g) and B. gladioli (strain BDBgla132A). In B. glumae (chromosome 2) the tox operon comprises the following genes in sequential order: toxJ, toxR, toxH, toxG, toxF, toxI, toxA, toxB, toxC, toxD, and toxE. In contrast, in B. gladioli (chromosome 1), the same genes are similarly arranged but with toxR relocated downstream of toxF. (E) Relative expression of the toxA–toxR genes was quantified by qPCR, normalizing to 16S rRNA and setting B. gladioli (BDBgla132A) expression to 1 for the control strain, whereas B. glumae (BD_21g) served as the test strain. Error bars represent standard errors from three independent biological replicates. All differences between groups were statistically significant at P < 0.05, as determined by the Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) and Student’s t-tests, which we conducted using the R software (version 4.4.1).

Figure 6.

Phenotypic traits of lipase production in B. glumae and B. gladioli. (A) Extracellular lipase activity on LB agar supplemented with 5% Tween 20, indicated by opaque halos surrounding BD_21g and BDBgla132A colonies; the negative control showed no activity. (B) Chromogenic assay with p-nitrophenyl palmitate, indicating lipase activity by yellow coloration in the test strains but not in the control. (C) Spectrophotometric measurement of lipase activity across multiple bacterial isolates at 410 nm. (D) Comparative genomic organization of the lipase-encoding genes lipA (teal) and lipB (yellow) in B. glumae (strain BD_21g) and B. gladioli (strain BDBgla132A). Both species exhibit tandem co-localization of lipA and lipB on chromosome 2 in the same orientation (lipA upstream of lipB), differing only in intergenic spacing. (E) Relative expression of lipA and lipB transcripts in B. glumae BD_21g compared to B. gladioli BDBgla132A (set to 1). Error bars denote standard errors calculated from three independent biological replicates. All observed differences between groups were statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level, as determined by the Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) and Student’s t-tests, which were conducted using the R statistical software (version 4.4.1).

Figure 6.

Phenotypic traits of lipase production in B. glumae and B. gladioli. (A) Extracellular lipase activity on LB agar supplemented with 5% Tween 20, indicated by opaque halos surrounding BD_21g and BDBgla132A colonies; the negative control showed no activity. (B) Chromogenic assay with p-nitrophenyl palmitate, indicating lipase activity by yellow coloration in the test strains but not in the control. (C) Spectrophotometric measurement of lipase activity across multiple bacterial isolates at 410 nm. (D) Comparative genomic organization of the lipase-encoding genes lipA (teal) and lipB (yellow) in B. glumae (strain BD_21g) and B. gladioli (strain BDBgla132A). Both species exhibit tandem co-localization of lipA and lipB on chromosome 2 in the same orientation (lipA upstream of lipB), differing only in intergenic spacing. (E) Relative expression of lipA and lipB transcripts in B. glumae BD_21g compared to B. gladioli BDBgla132A (set to 1). Error bars denote standard errors calculated from three independent biological replicates. All observed differences between groups were statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level, as determined by the Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) and Student’s t-tests, which were conducted using the R statistical software (version 4.4.1).

Figure 7.

Phenotypic and molecular characterization of polygalacturonase activity in B. glumae and B. gladioli. (A) Pectinolytic activity on semi-solid pectate-yeast agar (PEC-YA) showing halo formation around BDBgla132A and BD_21g colonies, unlike the negative control (B) Quantitative spectrophotometric measurement of polygalacturonase activity at 530 nm. (C) Comparative genomic organization of polygalacturonase-encoding genes pehA (yellow) and pehB (teal) in B. glumae (strain BD_21g) and B. gladioli (strain BDBgla132A). In B. glumae, pehA and pehB are located on separate replicons (chromosomes 1 and 2, respectively), whereas in B. gladioli both genes are arranged in tandem on chromosome 1. (D) Relative expression levels of pehA and pehB in BD_21g compared to BDBgla132A (expression normalized to 1). Error bars represent standard errors from three independent biological replicates. All differences were statistically significant at P < 0.05 (DMRT and Student’s t-tests, conducted in R v4.4.1).

Figure 7.

Phenotypic and molecular characterization of polygalacturonase activity in B. glumae and B. gladioli. (A) Pectinolytic activity on semi-solid pectate-yeast agar (PEC-YA) showing halo formation around BDBgla132A and BD_21g colonies, unlike the negative control (B) Quantitative spectrophotometric measurement of polygalacturonase activity at 530 nm. (C) Comparative genomic organization of polygalacturonase-encoding genes pehA (yellow) and pehB (teal) in B. glumae (strain BD_21g) and B. gladioli (strain BDBgla132A). In B. glumae, pehA and pehB are located on separate replicons (chromosomes 1 and 2, respectively), whereas in B. gladioli both genes are arranged in tandem on chromosome 1. (D) Relative expression levels of pehA and pehB in BD_21g compared to BDBgla132A (expression normalized to 1). Error bars represent standard errors from three independent biological replicates. All differences were statistically significant at P < 0.05 (DMRT and Student’s t-tests, conducted in R v4.4.1).

Figure 8.

Phenotypic and molecular features of motility in B. glumae and B. gladioli. (A) Swarming motility assays on 0.5% LB agar, showing the characteristic dendritic spreading for the positive isolates but not for the negative control (B) Quantitative measurement of swarming motility across Burkholderia strains, expressed as the diameter of motility zone on agar plates incubated at 34 °C. (C) Genomic organization of motility and chemotaxis gene clusters in B. glumae and B. gladioli. Chromosomal loci (chromosome 1) from B. glumae BD_21g and B. gladioli BDBgla132A (top and middle) show adjacent genes including fliD, fliC, flhD, flhC, motA, cheY, cheA, cheW, cheD, cheB, cheZ, flhB, flhA, flhF, and flhG. The B. glumae plasmid 2 and B. gladioli chromosome 1 fragments (second and bottom) each contain the fliA gene. Color coding highlights conserved homologous genes between strains. (D) Relative expression of flagellar regulatory genes flhF and flhC in B. glumae strain BD_21g normalized to expression in B. gladioli strain BDBgla132A (set to 1). Error bars represent standard errors from three biological replicates. Statistical analyses were performed using R v4.4.1. All comparisons were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05 using the Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) and Student’s t-tests.

Figure 8.

Phenotypic and molecular features of motility in B. glumae and B. gladioli. (A) Swarming motility assays on 0.5% LB agar, showing the characteristic dendritic spreading for the positive isolates but not for the negative control (B) Quantitative measurement of swarming motility across Burkholderia strains, expressed as the diameter of motility zone on agar plates incubated at 34 °C. (C) Genomic organization of motility and chemotaxis gene clusters in B. glumae and B. gladioli. Chromosomal loci (chromosome 1) from B. glumae BD_21g and B. gladioli BDBgla132A (top and middle) show adjacent genes including fliD, fliC, flhD, flhC, motA, cheY, cheA, cheW, cheD, cheB, cheZ, flhB, flhA, flhF, and flhG. The B. glumae plasmid 2 and B. gladioli chromosome 1 fragments (second and bottom) each contain the fliA gene. Color coding highlights conserved homologous genes between strains. (D) Relative expression of flagellar regulatory genes flhF and flhC in B. glumae strain BD_21g normalized to expression in B. gladioli strain BDBgla132A (set to 1). Error bars represent standard errors from three biological replicates. Statistical analyses were performed using R v4.4.1. All comparisons were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05 using the Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) and Student’s t-tests.

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic tree of concatenated toxoflavin synthesis genes (

toxA, toxB, toxC, toxD, toxE, toxF, toxG, toxH, toxI, toxJ, and t

oxR) from

B. gladioli and B. glumae. The tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method with the Tamura–Nei [

45] substitution model in MEGA 12 software [

44], based on concatenated alignment of 28 nucleotide sequences (21,891 bp total). Bootstrap support values (1,000 replicates, ≥80% threshold) are shown at branch nodes. Branch lengths represent nucleotide substitutions per site.

Figure 9.

Phylogenetic tree of concatenated toxoflavin synthesis genes (

toxA, toxB, toxC, toxD, toxE, toxF, toxG, toxH, toxI, toxJ, and t

oxR) from

B. gladioli and B. glumae. The tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method with the Tamura–Nei [

45] substitution model in MEGA 12 software [

44], based on concatenated alignment of 28 nucleotide sequences (21,891 bp total). Bootstrap support values (1,000 replicates, ≥80% threshold) are shown at branch nodes. Branch lengths represent nucleotide substitutions per site.

Figure 10.

Phylogenomic analysis of concatenated lipase-encoding genes (lipA/

lipB) from

B. gladioli and B. glumae. The tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method with the Tamura–Nei [

45] substitution model in the MEGA 12 software [

44], based on concatenated alignment of 28 nucleotide sequences (2,136 bp). Bootstrap support values (based on 1,000 replicates) are shown at branch nodes. Branch lengths represent nucleotide substitutions per site.

Figure 10.

Phylogenomic analysis of concatenated lipase-encoding genes (lipA/

lipB) from

B. gladioli and B. glumae. The tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method with the Tamura–Nei [

45] substitution model in the MEGA 12 software [

44], based on concatenated alignment of 28 nucleotide sequences (2,136 bp). Bootstrap support values (based on 1,000 replicates) are shown at branch nodes. Branch lengths represent nucleotide substitutions per site.

Figure 11.

Molecular phylogeny of pectinase-encoding genes of concatenated pectinase-encoding genes (

pehA/pehB) from

B. gladioli and B. glumae. Maximum Likelihood phylogeny (Tamura–Nei model [

45]) was inferred in MEGA 12 [

44] from 28 concatenated nucleotide sequences (4,488 bp). Bootstrap support values (1,000 replicates) are indicated at nodes; branch lengths represent nucleotide substitutions per site.

Figure 11.

Molecular phylogeny of pectinase-encoding genes of concatenated pectinase-encoding genes (

pehA/pehB) from

B. gladioli and B. glumae. Maximum Likelihood phylogeny (Tamura–Nei model [

45]) was inferred in MEGA 12 [

44] from 28 concatenated nucleotide sequences (4,488 bp). Bootstrap support values (1,000 replicates) are indicated at nodes; branch lengths represent nucleotide substitutions per site.

Figure 12.

Maximum Likelihood phylogeny of concatenated flagellum-encoding genes (

cheA, cheB, cheD, cheR, cheW, cheY, cheY1, cheZ, flhA, flhB, flhC, flhD, flhF, flhG, fliA, fliC, fliD, tsr, motA, and

motB) from

B. gladioli and

B. glumae. The tree was constructed using the Tamura–Nei [

45] substitution model in MEGA 12 software [

44] based on 19 concatenated genes from 28 nucleotide sequences (24,645 bp). Bootstrap support values (1,000 replicates) are shown at branch nodes. Branch lengths represent nucleotide substitutions per site. Branches with <80% bootstrap support were collapsed.

Figure 12.

Maximum Likelihood phylogeny of concatenated flagellum-encoding genes (

cheA, cheB, cheD, cheR, cheW, cheY, cheY1, cheZ, flhA, flhB, flhC, flhD, flhF, flhG, fliA, fliC, fliD, tsr, motA, and

motB) from

B. gladioli and

B. glumae. The tree was constructed using the Tamura–Nei [

45] substitution model in MEGA 12 software [

44] based on 19 concatenated genes from 28 nucleotide sequences (24,645 bp). Bootstrap support values (1,000 replicates) are shown at branch nodes. Branch lengths represent nucleotide substitutions per site. Branches with <80% bootstrap support were collapsed.

Table 1.

Pathogenicity test results of bacterial strains isolated from rice exhibiting bacterial panicle blight symptoms, and categorization based on isolate identity.

Table 1.

Pathogenicity test results of bacterial strains isolated from rice exhibiting bacterial panicle blight symptoms, and categorization based on isolate identity.

| Isolate IDa

|

Species |

Pathogenicity testb

|

Disease severityc

(0-9 scale) |

| Seedling |

Panicle |

| BD_21g |

B. glumae |

+++ |

+++ |

9.0 ± 0a*** |

| BDBgla132A |

B. gladioli |

+++ |

+++ |

8.2 ± 0.23ab*** |

| BDBgla117A |

B. gladioli |

+++ |

+++ |

7.8 ± 0.23ab*** |

| BDBgla135A |

B. gladioli |

+++ |

+++ |

8.0 ± 0.31ab*** |

| BDBgla122A |

B. gladioli |

+++ |

+++ |

7.9 ± 0.27ab*** |

| BDBgla78A |

B. gladioli |

++ |

+++ |

7.2 ± 0.12ab*** |

| BDBgla119A |

B. gladioli |

++ |

+++ |

7.3 ± 0.18b*** |

| BDBgla136A |

B. gladioli |

++ |

+++ |

7.5 ± 0.58de*** |

| BDBgla59A |

B. gladioli |

++ |

+++ |

7.0 ± 0.12bc*** |

| BDBgla150A |

B. gladioli |

+ |

++ |

7.6 ± 0.31bc*** |

| BDBgla81A |

B. gladioli |

+ |

++ |

5.7 ± 0.24bcd*** |

| BDBgla120A |

B. gladioli |

+ |

++ |

5.9 ± 0.58cde*** |

| BDBgla140A |

B. gladioli |

+ |

++ |

5.7 ± 0.29de*** |

| BDBgla83A |

B. gladioli |

+ |

++ |

5.6 ± 0.31de*** |

| BDBgla79A |

B. gladioli |

+ |

++ |

5.2 ± 0.12e*** |

| BDBgla130A |

B. gladioli |

+ |

++ |

5.1 ± 1.16e*** |

| BDBgla38A |

B. gladioli |

+ |

++ |

5.5 ± 0.35e*** |

| BDBgla162A |

B. gladioli |

0 |

+ |

3.7 ± 0.29f*** |

| BDBgla151A |

B. gladioli |

0 |

+ |

2.5 ± 0.73f*** |

| BDBgla41A |

B. gladioli |

0 |

+ |

2.7 ± 0.87f*** |

| Control |

Sterile water |

0 |

0 |

0.0 ± 0g |

Table 2.

Homology of virulence-associated genes between the B. gladioli BDBgla132A and B. glumae BD_21g genomes.

Table 2.

Homology of virulence-associated genes between the B. gladioli BDBgla132A and B. glumae BD_21g genomes.

| Virulence factor |

Gene |

Gene accession

(BDBgla132A) |

Gene accession

(BD_21g) |

Protein identity (%) |

| Toxoflavin |

toxA |

WP_047837656.1 |

WP_230674340.1 |

96.23 |

| toxB |

WP_013696509.1 |

WP_042967738.1 |

98.11 |

| toxC |

WP_186032113.1 |

WP_012733473.1 |

97.51 |

| toxD |

WP_186146217.1 |

WP_012733474.1 |

96.63 |

| toxE |

WP_186044336.1 |

WP_017922993.1 |

71.07 |

| toxF |

WP_186146218.1 |

WP_012733469.1 |

92.67 |

| toxG |

WP_186012765.1 |

WP_012733468.1 |

92.08 |

| toxH |

WP_439968039.1 |

WP_251107611.1 |

97.48 |

| toxI |

WP_439967532.1 |

WP_230674341.1 |

44.35 |

| toxJ |

WP_047838500.1 |

WP_012733464.1 |

77.50 |

| toxR |

WP_047837657.1 |

WP_012733470.1 |

96.01 |

| Lipase |

lipA |

WP_047838330.1 |

WP_012733585.1 |

88.55 |

| lipB |

WP_440015440.1 |

WP_251107590.1 |

80.71 |

| Polygalacturonase |

pehA |

WP_186012903.1 |

WP_017922174.1 |

84.53 |

| pehB |

WP_439967530.1 |

WP_017423921.1 |

87.35 |

| Chemotaxis and flagella |

cheA |

WP_440017944.1 |

WP_251107216.1 |

97.22 |

| cheB |

WP_047836241.1 |

WP_012734288.1 |

96.06 |

| cheD |

WP_036029515.1 |

WP_012734287.1 |

93.07 |

| cheR |

Absent |

- |

- |

| cheW |

WP_043219446.1 |

WP_012734284.1 |

92.57 |

| cheY |

WP_013696282.1 |

WP_012734289.1 |

96.18 |

| cheY1 |

WP_013696275.1 |

WP_302074279.1 |

80.80 |

| cheZ |

WP_047836242.1 |

WP_012734290.1 |

84.52 |

| flhA |

WP_036038249.1 |

WP_012734295.1 |

95.86 |

| flhB |

WP_013696287.1 |

WP_100556214.1 |

89.72 |

| flhC |

WP_013696272.1 |

WP_012734279.1 |

96.72 |

| flhD |

WP_025099997.1 |

WP_043226645.1 |

96.23 |

| flhF |

WP_440017650.1 |

WP_251107218.1 |

93.19 |

| flhG |

WP_013696290.1 |

WP_012734297.1 |

84.39 |

| fliA |

WP_013696291.1 |

WP_017433111.1 |

95.67 |

| fliC |

WP_186011140.1 |

WP_100556208.1 |

90.10 |

| fliD |

WP_047836234.1 |

WP_012734272.1 |

66.92 |

| motA |

WP_013696273.1 |

WP_012734280.1 |

96.50 |

| motB |

Absent |

- |

- |

| tsr |

Absent |

- |

- |