The SIR (susceptible-infected-recovered) model for epidemic propagation is among the most fundamental mathematical representations of the spreading of a contagious disease in a population of interacting agents. It belongs to a wide class of models where contact processes are used to describe the elementary events intervening in disease dissemination [

20,

21,

22]. In the SIR model, the contact of an infected agent and a susceptible agent may lead the latter to become infected. In contrast with the Maki-Thompson model studied above, however, the transition from the infected state to the recovered state occurs spontaneously, without intervention of other agents. Recovered agents, in turn, cannot change their state.

Although the SIR model is frequently formulated in terms of mean field equations [

22], it also admits several versions in the form of a stochastic contact process. By analogy with the Maki-Thompson process, at each time step, we here choose an infected agent at random. With probability

u, the agent becomes recovered. With the complementary probability,

, another agent is chosen at random from the whole population and, if this second agent is susceptible, it becomes infected.

Table 4 shows the elementary events of the model, their probabilities, and the corresponding constants of motion.

Proceeding as for the Maki-Thompson model to find joint conserved quantities for the stochastic process, we note that –since, now, the process is defined by three individual events– the coefficients in a linear combination of the individual constants of motion must satisfy two conditions,

instead of the only condition of Eq. (

2). Consequently, there is only one independent solution,

, corresponding to the trivial constant of motion

. Thus, the SIR stochastic process has no other conserved quantity.

This suggests that a combination of

and

, weighted with the total probabilities of the corresponding events,

may play a role similar to that of a constant of motion, although not being an exactly conserved quantity itself. To assess this conjecture, we explicitly calculate the stochastic evolution of

, finding

This stochastic process represents a one-dimensional symmetric random walk: its mean value and variance evolve as

respectively. In other words,

is an

approximate constant of motion, in the sense that its mean value is a conserved quantity. Its standard deviation, in turn, grows as

, like in any ordinary diffusion process. Note that, in combination with the trivial constant of motion

N,

straightforwardly yields the mean number of recovered agents over realizations with initial condition

:

The approximate constant of motion

acquires relevance when considering the mean-field version of the SIR model. To show this, first, we use the master equation of the process,

to find evolution equations for the mean numbers

and

:

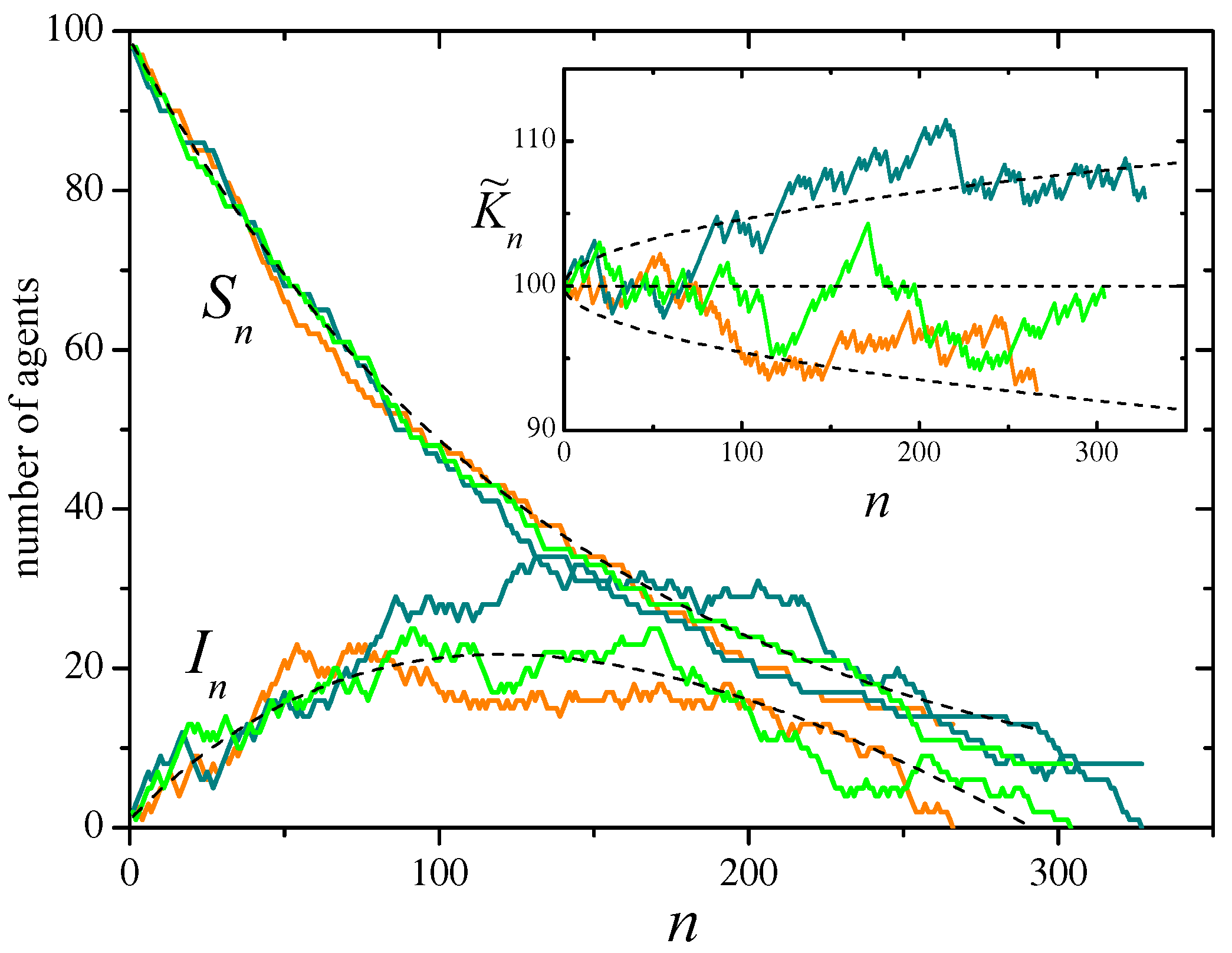

The main panel of

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the number of susceptible and infected agents along three realizations of the stochastic process, for a system with

agents and recovery probability

, from an initial condition with one infected agent and no refractory agents. A comparison with the mean evolution given by Eqs. (

32) is provided. The inset shows the evolution of the approximate constant of motion

, together with its expected mean value and standard deviation.

3.1. SIR Epidemics on Random Networks

An important extension of epidemiological models based on contact processes, aimed at approaching a more realistic representation of social structure, consists in considering populations distributed on a network [

23,

24,

25]. In this variant, agents are situated at the network nodes, and network links represent their mutual contacts, so that infection can only occur between neighbor agents. The heterogeneity induced by the network of contacts on the population structure implies that susceptible and infected agents have more chances of, respectively, becoming infected and transmitting the infection when their number of neighbors –namely, their degree– is larger. The mathematical description of the process thus requires discerning between agents with different degrees. For each possible degree

k, we denote by

,

, and

, the corresponding number of agents in each state of the SIR epidemics.

The SIR stochastic contact process on networks is here implemented as follows. At each evolution step, we choose at random a network link connected to (at least) one infected agent. With probability

u, this infected agent becomes recovered. With the complementary probability,

, if the second agent connected to the chosen link is susceptible, it becomes infected. Clearly, since one link is chosen at each step, the probability that any given infected or susceptible agent becomes involved in an event now depends on the respective degree

k. The second column of

Table 5 quotes the probabilities for each event in the case of a network with links distributed at random and with no statistical correlation between the degrees of neighbor agents.

Linear combinations of the constants of motion in the third column of

Table 5 show that the only independent conserved quantities common to all the events are, trivially, the total number of agents with each degree

k,

, for

. Meanwhile, a combination analogous to

in Eq. (

27), namely,

where

and

are the total numbers of susceptible and infected agents at step

n, satisfies the same stochastic evolution equation as

in Eq. (

28), and is thus an approximate constant of motion.

It turns out, however, that

is just but one among infinitely many combinations that act as approximate constants of motion for the SIR model on networks. To see this, consider for example the quantities

, for any value of the exponent

, where

z is the mean number of neighbors per network site. In an event as in the first line of

Table 5, where an infected agent becomes recovered at step

n, we have

, where

is the degree of the infected agent involved in that event. On the other hand, for the events in the second and third rows, we have

. Averaging over the possible values of

with their corresponding probabilities (second column of

Table 5), it turns out that the quantity

with

is driven by the stochastic process

cf. Eq. (

28). For this process,

give the evolution of the mean value and the standard deviation of

; cf. Eq. (

29). In other words,

is an approximate constant of motion for any value of

. Linear combinations of

for different values of

would produce infinitely many other approximate conserved quantities.

Mean-field equations for the stochastic SIR model on networks are obtained by assigning to each event a duration which appropriately takes into account the probability that an infected agent of degree

k becomes involved in that event. Equation (

11) now becomes

with

defined as in the caption of

Table 5. Here,

is the degree of the infected agent involved at step

n and, as in Eq. (

11),

fixes time units. The resulting equations for the fractions

,

, and

are

for each degree

k. Operating on these equations, it can be straightforwardly shown that the quantity

is a constant of motion, with

the initial density of susceptible agents with

k neighbors. We stress that, in spite of its functional form, the last term in the right-hand side of Eq. (

44) is independent of

k, as it becomes clear if the first of Eqs. (

43) is rewritten as

Comparing Eqs. (

44) and (

38), we realize that the approximate constant of motion of the stochastic process to be related to

is

. Up to a factor

N, the summations in both constants are the same, so that the comparison must be carried out between the last term in the right-hand side of each equation. In the stochastic process, the mean evolution of susceptible agents is

Replacing in the last term of Eq. (

44), we get

in the large-

N limit. As for the last term of Eq. (

38) with

,

, Eq. (

39) implies that, if infected agents are evenly distributed over the network, we can approximate

for all

m. Within this approximation, which should improve as the system size grows, we have

Taking into account Eq. (

46), it is clear that the expected proportionality

only holds if

, i. e. for a

regular random network [

26], where all agents have the same number of neighbors. Note that this condition is verified, in particular, for a fully connected network, where

for all agents. In this case, all agents can interact with each other, and we recover the SIR epidemic model without network.

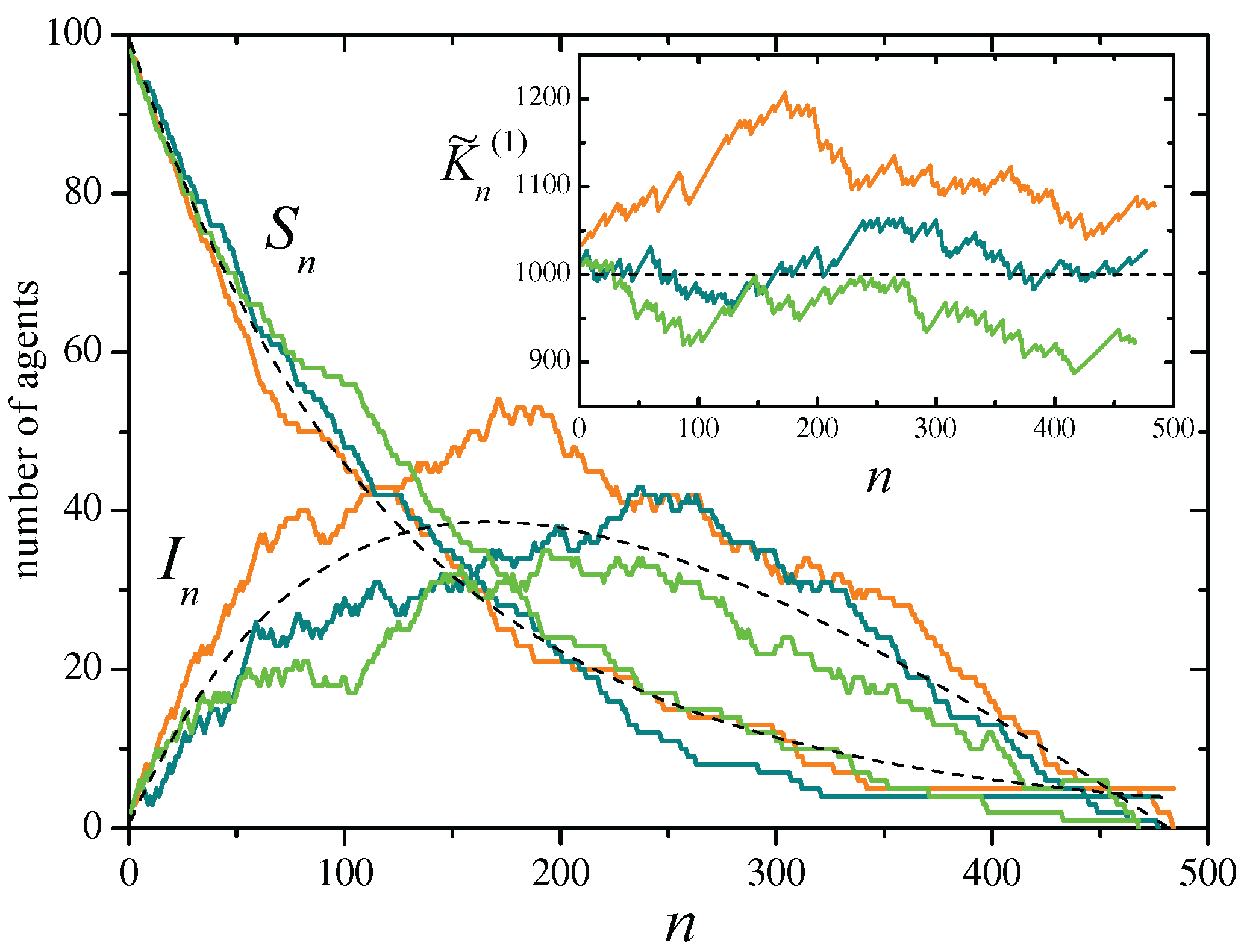

Figure 2 shows, in the main panel, results for three realizations of the SIR stochastic process on Erdos-Rényi random networks [

26] with

agents, and recovery probability

, from an initial condition with one infected agent and no refractory agents. On the average, each agent has

neighbors. Full curves stand for the evolution of the total number of susceptible and infected agents, respectively,

and

. Dashed curves correspond to their expected values, averaged over realizations of both the evolution and the underlying network. The inset shows the evolution of the approximate constant of motion

, given by Eq. (

38) for

. The horizontal dashed line indicates its expected mean value,

.