1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Significance

Suicidal ideation and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) are widely recognized as major public health concerns among adolescents worldwide. Epidemiological studies suggest that approximately 12–20% of adolescents report a lifetime history of NSSI [

1,

2], and suicidal ideation has been reported in a substantial proportion of adolescents across countries and cultural contexts [

3,

4]. These suicide-related phenomena are associated with elevated psychiatric comorbidity and increased risk of subsequent suicidal outcomes, as well as longer-term mental health difficulties that may persist into adulthood [

5,

6].

Adolescence is characterized by heightened emotional reactivity, ongoing neurobiological maturation—particularly involving prefrontal systems—and rapid changes in peer relationships and identity exploration [

7,

8]. These developmental features may be accompanied by challenges in emotion regulation and increased impulsivity, which can contribute to vulnerability to suicidal ideation and NSSI.

Despite the prevalence and clinical significance of suicidal ideation and NSSI, developmentally informed, evidence-based interventions that are feasible in real-world school contexts remain limited [

9,

10]. Many existing approaches are adapted from adult models or were originally developed for clinical populations with different developmental profiles, raising questions about developmental fit and implementation in school-based services.

Moreover, many adolescents report difficulties identifying and verbally articulating intense emotional distress. Such difficulties are often discussed in relation to reduced emotion awareness and labeling (e.g., alexithymia) and may limit engagement with interventions that rely primarily on verbal elaboration [

11,

12].

1.2. Theoretical Foundations of Sandplay Therapy

Sandplay therapy is grounded in Jungian analytical psychology and systematized by Dora Kalff, aiming to facilitate externalization of internal psychological material and promote integration through nonverbal, symbolic expression [

13]. In sandplay, clients construct scenes in a sandtray using miniature figures and objects, enabling symbolic representation of internal experiences without requiring explicit verbal explanation [

14].

Sandplay has been considered potentially suitable for children and adolescents who experience difficulty recognizing and verbalizing emotions or who show resistance to exclusively verbally focused psychotherapy [

15,

16]. Proposed mechanisms include activation of symbolic functioning, provision of a “free and protected space,” engagement of sensory–motor processes, and meaning-making through symbolic narrative construction [

17,

18]. Consistent with these mechanisms, neurobiological and trauma-informed perspectives suggest that sensory-based and creative modalities may support emotion regulation and trauma processing via pathways that are not limited to verbal-cognitive processing [

19,

20].

1.3. Sandplay Therapy and Suicide Prevention: Rationale for Integration

Sandplay therapy has been applied across a range of child and adolescent clinical contexts, including trauma-related symptoms, anxiety, and behavioral difficulties; however, research that explicitly targets suicidal ideation and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) as primary intervention outcomes remains limited, with only a small number of studies reported to date [

21,

22]. Nevertheless, several theoretical and clinical considerations support integration of sandplay-based work within suicide prevention.

First, suicidal ideation and NSSI often serve emotion regulation functions and may be maintained through negative reinforcement via short-term relief from overwhelming distress [

23,

24]. By providing a symbolic, experiential channel for expression and regulation, sandplay may offer alternative pathways for affect modulation and communication of distress [

25].

Second, adolescents at risk commonly report isolation, disconnection, and difficulty conveying distress to others [

26,

27]. The nonverbal and symbolic nature of sandplay may reduce barriers to engagement and support relational connection through shared witnessing of symbolic material with the therapist [

28].

Third, contemporary theories of suicide highlight the clinical relevance of psychological pain, hopelessness, and interpersonal factors such as perceived burdensomeness [

29,

30]. Sandplay’s emphasis on accessing internal resources and facilitating symbolic transformation toward integration and hope is conceptually aligned with these targets [

31].

1.4. Common Features of Suicide-Focused Evidence-Based Interventions

Over the past two decades, suicide-focused psychotherapies have been developed and empirically evaluated, and many share core components despite differences in theoretical orientation.

First, these interventions treat suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors as primary treatment targets rather than secondary manifestations of broader psychopathology, maintaining an explicit suicide focus throughout care [

32]. Second, they emphasize structured, collaborative risk assessment, engaging adolescents in clarifying individualized risk and protective factors; tools such as the Suicide Status Form within Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) support shared understanding and alliance [

32], while standardized measures such as the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) facilitate systematic assessment and monitoring over time [

33]. Third, individualized safety planning is central, including warning signs, coping strategies, social supports, emergency contacts, and means restriction to mitigate acute risk [

34]. Fourth, these approaches are typically brief and protocol-driven (commonly ~8–16 sessions), supporting feasibility in school and routine-care contexts [

32,

35]. Finally, many incorporate skills-focused elements (e.g., emotion regulation and crisis coping) to strengthen capacity to manage high-risk affective states [

35,

36].

Taken together, these shared elements highlight the clinical value of combining developmentally appropriate engagement with structured risk management in real-world settings—an integration that informed the development of SPT-SAFE.

1.5. Development of SPT-SAFE

SPT-SAFE is a manualized intervention for children and adolescents presenting with suicidal ideation and/or NSSI. It preserves the nondirective, symbolic principles of Kalffian sandplay therapy while integrating evidence-based, suicide-focused prevention strategies.

Within SPT-SAFE, suicidal ideation and NSSI are treated as primary clinical targets. Core components include collaborative risk assessment, individualized safety planning, session-by-session monitoring of risk-related behaviors, development of adaptive coping strategies, and predefined crisis-response protocols for periods of acute risk. This integration is intended to address both symbolic–emotional processes emphasized in sandplay therapy and structured risk-management elements central to contemporary suicide-focused care.

1.6. Study Objectives and Hypotheses

The primary objective of this randomized controlled trial was to evaluate the effectiveness of SPT-SAFE compared with Treatment as Usual–Risk Management Counseling (TAU-RMC) in reducing NSSI frequency and suicidal ideation severity among school-based adolescents. A secondary objective was to descriptively examine broader emotional and behavioral functioning using selected MMPI-A clinical scales.

Based on these objectives, we hypothesized that adolescents receiving SPT-SAFE would show greater reductions in (1) NSSI frequency and (2) suicidal ideation severity compared with those receiving TAU-RMC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study is an ongoing randomized controlled trial (RCT) designed to evaluate the effectiveness of Sandplay Therapy with Suicidal Ideation and Self-Injury–Focused Engagement (SPT-SAFE) in a school-based high-risk intervention setting. The present manuscript reports an exploratory analysis of an early enrolled cohort, for whom outcome data collection was completed prior to completion of overall recruitment. The trial was designed to closely reflect real-world school-based mental health services delivered through a specialized counseling center operated under the Chungcheongnam-do Office of Education, thereby enhancing ecological validity. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Dankook University (initial approval: DKU 2025-01-005-004; amendment approval: DKU 2025-01-005-008) and registered with the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS; KCT0011385). The statistical analysis plan (SAP) was finalized on 15 January 2025, prior to the initial IRB submission and before enrollment of the first participant. Although trial registration (CRIS; KCT0011385) occurred after enrollment had begun, this exploratory analysis was conducted using prespecified outcomes, assessment time points, and analytic methods, with key study milestones summarized in

Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Setting and Participant Recruitment

Participants were adolescents referred to a specialized commissioned counseling center operated under the Chungcheongnam-do Office of Education following school-based identification of suicide-related concerns (suicidal ideation and/or NSSI). Referrals were initiated by participating middle and high schools based on routine clinical judgment and were independent of study participation.

An official recruitment notice for the ongoing RCT was distributed to eligible schools on 1 June 2025, and enrollment for the cohort reported in this manuscript occurred between June and July 2025. Importantly, referral to the counseling center occurred prior to and independently of research recruitment, ensuring that access to clinical services was not contingent upon study participation. Following referral, eligible adolescents and their legal guardians received detailed study information, and written informed consent/assent was obtained prior to enrollment.

Within a school mental health framework, participants can be conceptualized as a Tier 2 risk group within a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) for suicide prevention, characterized by suicidal ideation and/or NSSI in the absence of acute intent or life-threatening behavior [

37]. Adolescents presenting with acute crisis requiring immediate psychiatric hospitalization (Tier 3) were excluded in accordance with established safety guidelines [

38].

2.3. Participants

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

Participants were eligible if they met all of the following criteria: (1) aged 12–19 years; (2) enrolled in a participating middle or high school and receiving school-based mental health services; (3) exhibiting current suicidal ideation (with or without a specific plan) and/or having engaged in at least one episode of NSSI within the past six months; (4) possessing sufficient cognitive and language abilities to complete study assessments; and (5) providing written informed consent from a legal guardian and written assent from the adolescent.

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

Participants were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) acute suicidal crisis requiring immediate psychiatric hospitalization; (2) active psychotic symptoms or severe cognitive impairment precluding participation in therapy or completion of assessments; (3) concurrent receipt of other intensive psychotherapeutic interventions specifically targeting suicidal ideation or NSSI; or (4) insufficient school attendance to complete the intervention protocol.

2.3.3. Eligibility and Sample Flow

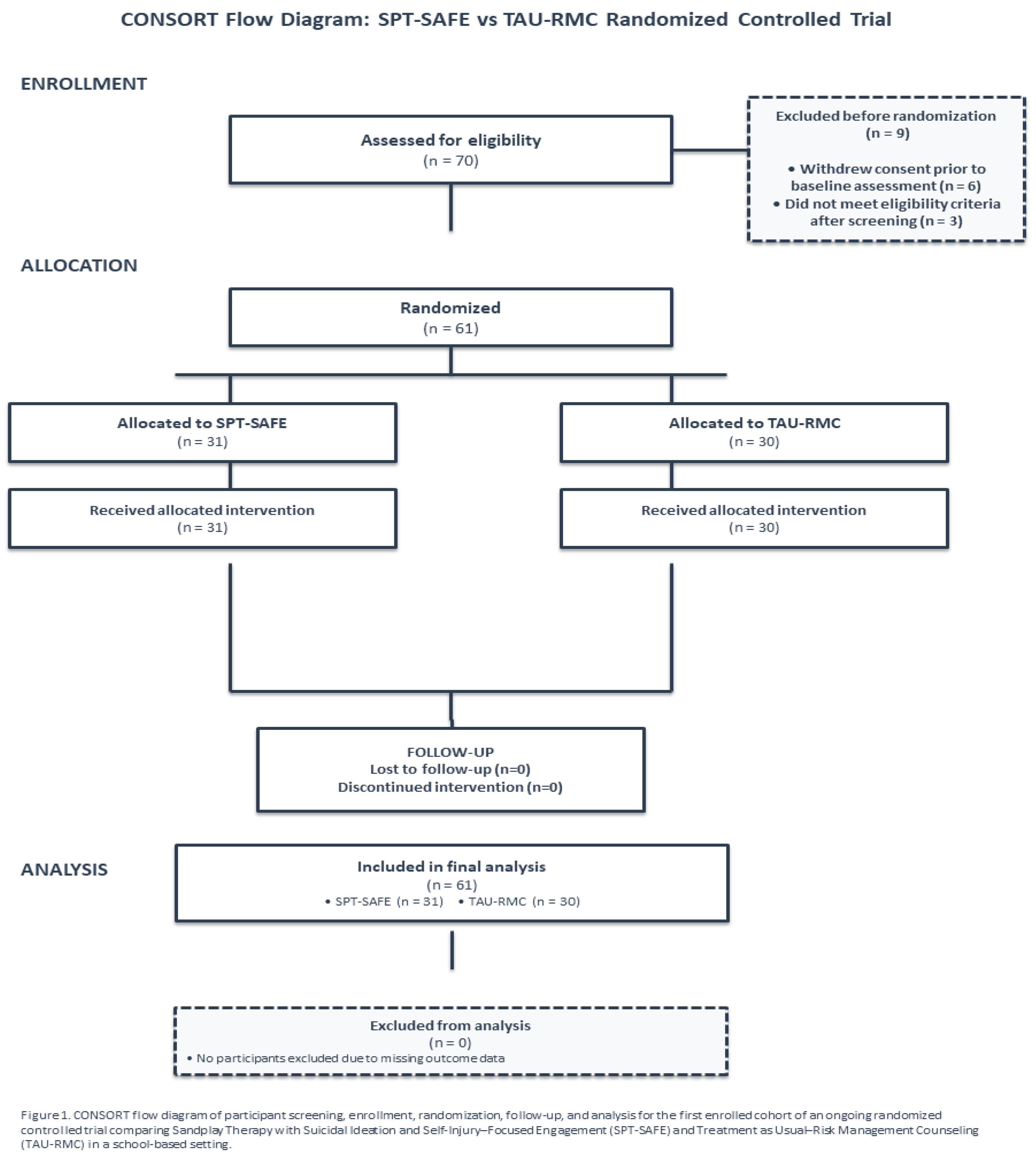

A total of 89 adolescents were screened at baseline. Individuals with imminent suicide risk (e.g., active suicidal plan or recent suicide attempt) were excluded at screening to ensure participant safety in the school-based setting, resulting in 19 exclusions due to ineligibility. Of the remaining 70 adolescents who provided informed consent/assent, 9 were excluded prior to randomization (6 withdrew consent before baseline assessment and 3 did not meet eligibility criteria after screening). The present exploratory analysis includes 61 participants were randomized and allocated to SPT-SAFE (n = 31) or TAU-RMC (n = 30). All randomized participants completed baseline and post-intervention assessments and were included in the primary analysis. Participant flow is summarized in

Figure 1.

2.4. Randomization and Blinding

2.4.1. Baseline Assessment and Informed Consent

After obtaining written informed consent (parents/legal guardians) and assent (adolescents), baseline assessments were completed prior to randomization. Baseline measures included suicidal ideation (SIQ-JR), NSSI (FASM), selected MMPI-A clinical scales, and sociodemographic information (e.g., sex, age, grade, socioeconomic status, and family vulnerability indicators). Baseline data were also used to define stratification variables for randomization.

2.4.2. Stratified Randomization, Rolling Enrollment and Blinding

Participants were randomized on a rolling basis immediately after completion of baseline assessment. Stratification variables were prespecified as sex (male vs. female), age group (12–14, 15–16, 17–19 years), baseline suicidal ideation severity (SIQ-JR high vs. low based on the sample median), and presence of NSSI (FASM yes vs. no). Within strata, participants were assigned to SPT-SAFE or TAU-RMC using a pre-generated block randomization schedule.

The allocation sequence was computer-generated by an administrative staff member independent of recruitment, assessment, intervention delivery, and study supervision. Group assignment was implemented by the research coordinator after baseline assessment. The allocation schedule was not accessible to recruiting clinicians, assessors, intervention providers, or the principal investigator.

Because of the nature of the intervention, blinding of participants and therapists was not feasible. Outcomes were collected via self-administered standardized questionnaires, and assessors were not involved in intervention delivery. Analyses for the present exploratory study were conducted by an independent external data analyst blinded to group assignment; group labels were anonymized prior to analysis.

2.5. Interventions

2.5.1. Common Initial Risk Management and Safety Care Procedures

All referred adolescents received a standardized set of initial risk management and safety procedures prior to initiating study-specific interventions. These procedures were implemented uniformly across conditions as core ethical components of suicide risk management in the ongoing randomized controlled trial, and were applied consistently in the context of the present exploratory analysis.

First, structured suicide risk assessment was conducted primarily using the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). When clinically indicated, a developmentally appropriate collaborative assessment was additionally conducted using selected items from the Suicide Status Form (SSF; CAMS-4Teens) to characterize subjective risk intensity and individualized risk factors [

32,

33].

Second, based on assessment findings, all participants collaboratively developed an individualized safety plan following the Safety Planning Intervention (SPI). Plans included warning signs, internal coping strategies, social supports, professional and emergency contacts, and means restriction strategies [

34].

Third, a crisis response and safety network was established with caregivers and relevant school personnel to support ongoing monitoring, timely information sharing, and rapid activation of intervention procedures when clinically indicated. Collectively, these procedures reflect shared core components of evidence-based, suicide-focused interventions and served as a standardized safety management framework for school-based suicide prevention.

Safety Monitoring and Adverse Events. Safety was monitored throughout the study using the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), administered by trained clinicians at baseline and at each treatment session, along with predefined crisis response protocols within the school-based support network. Escalation procedures were initiated only when participants met predefined criteria for acute risk, such as the emergence of suicidal intent or a specific plan.

Adverse events (AEs) were defined as clinically significant worsening requiring additional intervention beyond routine Tier 2 care, including emergency referral or hospitalization. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were defined as suicide attempts or psychiatric hospitalization. Reviews of safety plans were conducted as part of routine care; however, only formal, documented revisions were coded as safety plan updates for adverse event reporting.

2.5.2. SPT-SAFE Intervention

SPT-SAFE is a school-based intervention model grounded in Kalff’s nondirective sandplay therapy, integrating suicidal ideation and NSSI risk as core clinical contexts throughout treatment. The intervention was delivered once weekly for eight sessions (45–50 min each).

Key components included: (1) nondirective sandplay to facilitate symbolic expression and emotional integration within a free and protected space; (2) session-by-session monitoring of suicide-related risk (suicidal ideation, NSSI urges/behaviors) using a brief risk monitoring log incorporating selected Suicide Status Form (SSF) items; (3) bottom-up stabilization strategies to reduce physiological arousal and distress (e.g., sensory-based regulation embedded in sandplay, reflective viewing to support present-moment awareness, and brief breathing/grounding techniques); and (4) reassessment and documentation of safety status at the end of each session, with safety plans revised and crisis protocols activated when clinically indicated.

Throughout treatment, therapists maintained an attitude of empathic witnessing and provided nonjudgmental responses to symbolic material, supporting adolescents’ autonomous meaning-making.

2.5.3. TAU-RMC Intervention

TAU-RMC was grounded in supportive counseling (SC) and served as an active comparison condition controlling for nonspecific factors (e.g., alliance, attention, expectancy, and session structure). To meet ethical standards for research with high-risk adolescents, TAU-RMC incorporated structured suicide risk assessment and safety planning procedures [

34,

36,

39].

TAU-RMC was delivered once weekly for eight sessions (45–50 min each). At each session, therapists conducted a brief check-in and assessed suicidal ideation/behavior using C-SSRS–based screening questions [

33]. When indicated, existing Safety Planning Intervention (SPI) plans were reviewed and updated, and predefined crisis response procedures were activated if imminent risk was identified [

34].

Supportive counseling emphasized active listening, empathic reflection/validation, and exploration and normalization of emotions and experiences. TAU-RMC did not include structured skills training, cognitive restructuring, behavioral assignments, or expressive/nonverbal modalities such as sandplay therapy [

36].

2.5.4. Therapist Teams, Supervision, and Fidelity

To minimize cross-condition contamination, SPT-SAFE and TAU-RMC were delivered by separate therapist teams with no provider overlap. All therapists held at least a master’s degree in psychology and had ≥3 years of clinical experience providing counseling for adolescents at suicide risk. Across both conditions, therapists received regular clinical supervision provided by a doctoral-level psychologist.

Treatment fidelity for SPT-SAFE was monitored using an a priori standardized checklist based on the intervention manual, independent review of selected session records. Fidelity ratings were completed by sandplay therapy specialists with ≥5 years of clinical experience. Details of the checklist are provided in

Supplementary Materials (

Table S2).

Treatment fidelity was assessed using a standardized fidelity checklist developed a priori based on the core components of the SPT-SAFE intervention manual. Fidelity monitoring was conducted through weekly supervision meetings and independent review of randomly selected session records, comprising approximately 20% of all intervention sessions.

The fidelity checklist included key items such as maintenance of a nondirective therapeutic stance and integration of suicide- and NSSI–focused risk monitoring and safety planning procedures (see

Supplementary Materials,

Table S2 for details of the checklist).

Overall, adherence to the SPT-SAFE intervention protocol was high, with a mean fidelity score of 92.3% (SD = 5.1%), indicating adequate intervention integrity across sessions for the purposes of this exploratory analysis.

2.6. Outcome Measures

2.6.1. Outcomes of Interest

NSSI was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation (FASM; Lloyd, Kelley, & Hope, 1997). Participants reported the frequency of common NSSI behaviors (e.g., cutting, burning, hitting) over the past month, and the total frequency score was used as the primary indicator of NSSI severity in this exploratory analysis. The FASM has demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity in adolescent samples [

40].

Suicidal ideation was assessed using the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire–Junior (SIQ-JR; Reynolds, 1988), a 15-item self-report measure of suicidal thought frequency and severity over the past month. Items are rated from 0 (“I never had this thought”) to 6 (“Almost every day”), yielding a total score range of 0–90, with higher scores indicating greater suicidal ideation severity. The SIQ-JR has shown excellent internal consistency (α = 0.94) and strong validity in adolescents [

41].

2.6.2. Secondary Outcomes

General Psychopathology. General psychopathology was assessed using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–Adolescent (MMPI-A; Butcher et al., 1992), a validated instrument for evaluating broad psychopathology and personality-related functioning in adolescents. Given the exploratory nature of secondary outcomes, the interim sample size, and multiplicity concerns, MMPI-A analyses were restricted a priori to selected clinical scales most relevant to emotional distress and behavioral dysregulation commonly associated with suicidal ideation and NSSI. Results are reported descriptively in the

Supplementary Materials.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were prespecified for the parent trial and are reported here for an exploratory analysis of the first enrolled cohort of an ongoing randomized controlled trial. Given that this cohort represents an early subset of participants, analyses emphasized estimation (effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals) and consistency across complementary approaches rather than confirmatory hypothesis testing. All analyses were conducted in SPSS (version 25; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

For the outcomes of interest—NSSI frequency (FASM) and suicidal ideation (SIQ-JR)—baseline-adjusted analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were used as the primary analytic approach in this exploratory analysis, with post-intervention scores entered as dependent variables, treatment group as the independent variable, and corresponding baseline scores as covariates.

Suicidal ideation (SIQ-JR) was analyzed on the raw total score scale using ANCOVA.

NSSI frequency, measured by the Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation (FASM), was analyzed using ANCOVA applied to a log-transformed outcome, log(FASM + 1), due to the count nature of the variable, its pronounced positive skew, and the high proportion of zero values. Adjusted mean differences with 95% confidence intervals are reported (

Table 2); for interpretability, results may additionally be presented as back-transformed estimates on the original scale.

As sensitivity analyses, linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) with fixed effects for time (baseline vs. post-intervention), group, and the time × group interaction were used to evaluate whether pre–post change differed by group; subject-specific random intercepts were included to account for within-subject correlation. LMM results are summarized in

Table 3.

Between-group comparisons of change scores (Δ = pre − post) using independent-samples t tests were not conducted, as baseline-adjusted analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) and LMMs were considered complementary and statistically efficient approaches for estimating between-group differences in this exploratory context.

Within-group pre–post changes are described descriptively for context; however, statistical inference focused on between-group comparisons to reduce overinterpretation of non-specific change. Tests were two-tailed with α = 0.05 for outcomes of interest, and no multiplicity adjustments were applied given the exploratory nature of this early cohort analysis. Findings are therefore interpreted as provisional pending completion of recruitment.

Secondary analyses (MMPI-A). Selected MMPI-A clinical scales were summarized descriptively using within-group pre–post comparisons only. No between-group hypothesis testing or multiplicity adjustments were applied. Results are reported in the

Supplementary Materials to contextualize broader emotional and behavioral change.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Flow and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 61 adolescents from the early enrolled cohort of an ongoing randomized controlled trial were included in the present exploratory analyses (SPT-SAFE, n = 31; TAU-RMC, n = 30). All participants included in the analytic sample completed both baseline and post-intervention assessments for the outcomes of interest, and no missing outcome data were observed within this cohort.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants, including baseline levels of suicidal ideation and NSSI, are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Outcomes of Interest

3.2.1. Primary Analysis: Baseline-Adjusted ANCOVA

Between-group differences in outcomes of interest—suicidal ideation (SIQ-JR) and NSSI (FASM)—were evaluated using baseline-adjusted analyses of covariance (ANCOVA), with post-intervention scores entered as dependent variables, treatment group as the independent variable, and corresponding baseline scores included as covariates.

As shown in

Table 2, the ANCOVA conducted on log-transformed NSSI frequency scores indicated a directionally greater reduction in the SPT-SAFE group compared with the TAU-RMC group; however, the adjusted between-group effect was negligible, with confidence intervals spanning zero, and did not reach statistical significance (F(1,58) = 0.15, p = 0.696, partial η² = 0.003).

In contrast, suicidal ideation showed a baseline-adjusted between-group difference favoring the SPT-SAFE group, with a small-to-moderate effect size and a confidence interval that excluded zero (F(1,58) = 4.43, p = 0.040, partial η² = 0.071).

Taken together, the prespecified baseline-adjusted ANCOVA analyses in this exploratory early cohort suggest a preliminary treatment-associated difference on suicidal ideation, whereas the estimated effect on NSSI frequency was small and imprecise and could not be reliably distinguished from no between-group difference.

Table 2.

Baseline-Adjusted Between-Group Effects on Primary Outcomes (ANCOVA).

Table 2.

Baseline-Adjusted Between-Group Effects on Primary Outcomes (ANCOVA).

| Outcome |

Scale / Transformation |

Adjusted Between-Group Effect

(SPT-SAFE − TAU-RMC) |

95% Confidence Interval |

Effect Size |

F(df) |

p Value |

|

|

| NSSI frequency (FASM) |

log(FASM + 1) |

−0.08 |

[−0.46, 0.30] |

partial η² = 0.003 |

0.15 (1,58) |

0.696 |

|

|

| Suicidal ideation (SIQ-JR) |

Raw score |

−6.12 |

[−12.03, −0.21] |

partial η² = 0.071 (≈ d = 0.56) |

4.43 (1,58) |

0.04 |

|

|

Note.

Adjusted effects were estimated using baseline-adjusted analyses of covariance (ANCOVA), with post-intervention scores as dependent variables, treatment group as the independent variable, and corresponding baseline values as covariates. Primary interpretation emphasizes effect sizes and confidence intervals rather than null-hypothesis significance testing. F statistics and p values are reported for completeness. |

|

|

3.2.2. Secondary Sensitivity Analyses: Linear Mixed-Effects Models

To further characterize patterns of change over time and to complement the prespecified baseline-adjusted ANCOVA analyses in this exploratory early cohort, secondary sensitivity analyses were conducted using LMMs.

For NSSI frequency, the LMMs suggested a directionally greater reduction over time in the SPT-SAFE group relative to the TAU-RMC group, as reflected in the time × group interaction term. For suicidal ideation, the LMMs showed a pattern of change consistent with the baseline-adjusted ANCOVA findings, with steeper reductions over time observed in the SPT-SAFE group.

Because these analyses were prespecified as sensitivity analyses and were conducted in a modest early cohort, the LMM findings should be interpreted cautiously. Differences between the ANCOVA and LMM results likely reflect differences in model structure, distributional assumptions, and sensitivity to baseline variability in a small sample. Accordingly, the LMM results are presented to illustrate general patterns and directional consistency across analytic approaches, whereas primary statistical inference for this exploratory analysis is based on the prespecified baseline-adjusted ANCOVA analyses. The LMM results are summarized in

Table 3.

Table 3.

Sensitivity Analyses Using Linear Mixed-Effects Models.

Table 3.

Sensitivity Analyses Using Linear Mixed-Effects Models.

| Outcome |

Fixed Effect |

Estimate (SE) |

Direction |

p value |

| NSSI (FASM) |

Time × Group |

−0.42(0.20) |

Greater reduction in SPT-SAFE |

0.036 |

| Suicidal Ideation (SIQ-JR) |

Time × Group |

−0.58(0.26) |

Greater reduction in SPT-SAFE |

0.045 |

3.2.3. Safety and Adverse Events

Safety outcomes were monitored throughout the study period using predefined procedures in this exploratory early cohort. No serious adverse events occurred in either group, including suicide attempts or psychiatric hospitalizations.

No adverse events, emergency referrals, or crisis protocol activations meeting the predefined criteria for reportable events were recorded during the intervention period. Although ongoing risk monitoring and safety planning were conducted as part of routine clinical care, no formal revisions to documented safety plans were required based on the predefined criteria for safety plan updates within this cohort.

All participants included in the analytic sample completed the intervention. A summary of safety outcomes by treatment group is presented in

Supplementary Table S3.

3.3. Exploratory Outcomes: MMPI-A Clinical Scales

3.3.1. Within-Group Changes

Descriptive analyses of MMPI-A clinical scales were conducted to examine within-group changes from pre- to post-intervention. In the SPT-SAFE group, reductions were observed across several MMPI-A clinical scales, including Depression (D), Psychasthenia (Pt), Schizophrenia (Sc), Paranoia (Pa), and Psychopathic Deviate (Pd).

In the TAU-RMC group, MMPI-A clinical scale scores showed little change from pre- to post-intervention across the study period. No between-group statistical comparisons were conducted for MMPI-A outcomes.

Given the secondary nature of these outcomes and the limited sample size, MMPI-A findings are reported descriptively to provide contextual information alongside the outcomes of interest. Detailed results are presented in

Supplementary Table S4

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

This study reports findings from an exploratory analysis of an early enrolled cohort of an ongoing randomized controlled trial evaluating SPT-SAFE in a school-based setting. In the prespecified baseline-adjusted ANCOVA, the between-group difference in post-intervention NSSI frequency favored SPT-SAFE but was small and did not reach conventional statistical significance. In contrast, suicidal ideation showed a baseline-adjusted between-group difference favoring SPT-SAFE, with a small-to-moderate effect observed in this exploratory early cohort.

Across prespecified sensitivity analyses, patterns of change were directionally consistent, indicating greater pre-to-post reductions in the SPT-SAFE group relative to TAU-RMC. Taken together, these findings suggest a preliminary and hypothesis-generating signal associated with SPT-SAFE; however, these exploratory effect estimates should be interpreted cautiously in light of the modest cohort size and the ongoing nature of trial enrollment.

The present findings are of clinical interest given the high prevalence of NSSI among adolescents [

1,

2] and the well-documented association between self-injurious thoughts and behaviors and subsequent suicidal outcomes [

5,

26]. Rather than providing definitive evidence of efficacy, the observed pattern highlights the importance of continued evaluation of developmentally appropriate interventions that can be feasibly integrated within school-based suicide risk management systems.

4.2. Interpretation of Findings

4.2.1. Suicidal Ideation

Reductions in suicidal ideation observed across both intervention arms may reflect shared components of care, including regular clinical contact, structured monitoring, and safety-focused interventions, all of which have been associated with enhanced connectedness and short-term reductions in suicide risk [

32]. In addition, the school-based context may itself provide protective effects through improved accessibility to care, consistent adult oversight, and facilitated linkage to support systems [

42,

43].

Against this background, the present exploratory analyses indicated a baseline-adjusted between-group difference in suicidal ideation favoring the SPT-SAFE condition, with a small-to-moderate effect size observed in the primary ANCOVA and a directionally consistent pattern in sensitivity analyses; however, these findings should be interpreted cautiously given the modest sample size and early cohort design.

One possible explanation for this pattern is that the symbolic and nonverbal features of SPT-SAFE may facilitate earlier shifts in affective distress and internal states closely linked to suicidal ideation, particularly among adolescents who experience difficulty verbalizing emotions or who exhibit heightened shame and interpersonal avoidance [

11,

12]. This interpretation is broadly consistent with sandplay-based approaches emphasizing symbolic expression within a structured and protected therapeutic space, as well as with trauma-informed and psychobiological perspectives highlighting the role of sensory–motor engagement and image-based processing in the regulation of heightened arousal and distress [

13,

14,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Given the short-term assessment window and the exploratory nature of this early cohort, the stability and clinical significance of the observed between-group differences remain to be determined.

4.2.2. NSSI

In this exploratory early cohort, SPT-SAFE was associated with a statistically reliable between-group effect on suicidal ideation, whereas no statistically reliable between-group effect was observed for NSSI frequency. Although a directionally greater reduction in NSSI was observed in the SPT-SAFE group, the estimated effect size was small and accompanied by considerable uncertainty, likely influenced by the modest sample size and the distributional characteristics of NSSI frequency data.

While statistical and methodological factors—such as low base rates, zero inflation, and limited power—may have contributed to these findings, the observed pattern also invites reflection on the therapeutic orientation and hypothesized mechanisms of SPT-SAFE. The intervention was designed to preserve the core principles of sandplay therapy, including non-directiveness, symbolic expression, and the autonomous integration of affective experience [

13,

14,

17,

18], while integrating core components common to suicide-focused evidence-based interventions, such as structured risk assessment and safety planning [

32,

33,

34]. Within this framework, suicidal ideation was specified as the primary clinical target, whereas behaviorally explicit intervention elements were intentionally minimized.

From a mechanistic perspective, sandplay-based symbolic–expressive engagement may be more likely to facilitate early changes in internal processes, such as affective processing, distress tolerance, and relational safety. In contrast, NSSI is commonly conceptualized as a functionally reinforced behavior serving emotion-regulation and distress-modulation functions [

23,

24], and reductions in its frequency may require longer intervention duration or the inclusion of more explicit behavior-focused strategies. Accordingly, changes in suicidal ideation may emerge earlier in treatment, whereas observable reductions in NSSI may lag behind or depend on additional therapeutic components.

In this context, the directionally favorable pattern observed for NSSI in the SPT-SAFE group is best interpreted not as confirmatory evidence of behavioral efficacy, but as an exploratory and hypothesis-generating signal within this early cohort analysis. Future studies with larger samples, longer follow-up periods, and designs that examine staged or combined symbolic–expressive and behavioral approaches will be essential to clarify whether early shifts in affective and relational processes translate into sustained reductions in NSSI.

4.3. Secondary Findings (MMPI-A)

MMPI-A clinical scales were included as secondary indicators of broader emotional and behavioral functioning [

44,

45]. Given the number of available scales and the limited sample size of the exploratory early cohort, MMPI-A findings were examined descriptively and are presented to provide contextual information alongside the outcomes of interest. These results should not be interpreted as evidence of broad treatment effects on general psychopathology and are therefore reported in the

Supplementary Materials.

4.4. Developmental Appropriateness of Sandplay Therapy for Adolescents

Adolescence involves ongoing cognitive–affective maturation and heightened sensitivity to emotional and social contexts [

7,

8]. Under conditions of elevated distress, sensory–motor and symbolic engagement may provide an accessible means of affect processing without reliance on fully elaborated verbal insight [

19,

20,

46]. In this context, early changes observed in this exploratory cohort in internal distress or suicidal ideation may plausibly precede more gradual or durable changes in NSSI.

Sandplay therapy may be developmentally congruent with adolescents’ needs for autonomy and identity exploration by allowing self-directed symbolic expression within a protected therapeutic space [

47,

48]. By supporting affect expression, psychological distancing, and meaning-making, sandplay-based interventions may contribute to short-term reductions in suicidal ideation, even when observable behavioral change requires longer time frames or additional therapeutic components.

From a broader perspective, the present findings from this exploratory early cohort analysis invite further consideration of sandplay-based approaches for suicidal children and adolescents. While prior applications in this population have largely been limited to case reports or small-scale studies [

49], the current results suggest the value of continued empirical and conceptual examination of sandplay-based therapeutic mechanisms, particularly within school-based settings where structured risk management and coordination with support systems are feasible and supported by prior research [

42,

43].

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. These include its randomized controlled design conducted in a real-world school-based setting, the use of standardized and well-validated measures targeting suicidal ideation and NSSI, and the implementation of a structured suicide safety management framework across both treatment conditions. Although not an outcome of interest for the present exploratory analysis, participant and caregiver satisfaction with services, assessed descriptively using the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire–8 (CSQ-8), was generally positive (

Supplementary Table S5).

Several limitations should also be noted. First, the present findings are based on an exploratory early cohort from an ongoing trial, and the modest sample size limited statistical power and the precision of effect size estimates for between-group differences, particularly for outcomes characterized by substantial variability and skewed distributions, such as NSSI frequency. Second, outcomes were assessed only at post-intervention, precluding evaluation of the durability of observed effects—an important consideration given the recurrent nature of adolescent NSSI and suicide-related difficulties [

50]. Third, reliance on self-report measures may have introduced reporting biases, especially for stigmatized behaviors [

51].

Fourth, although prespecified sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine the robustness of findings across analytic approaches, differences in model structure yielded some variation in observed patterns, underscoring the need for adequately powered samples and longer follow-up periods to obtain stable estimates of treatment-associated differences, particularly for behavioral outcomes with high inter-individual variability. Finally, while trial registration occurred after the initiation of participant recruitment due to administrative requirements, the study protocol—including eligibility criteria, outcome definitions, and analytic plans—was finalized and approved prior to recruitment and the present analyses were conducted within this prespecified framework as part of an exploratory early cohort analysis.

Future analyses conducted after completion of recruitment, incorporating additional psychological outcomes and longitudinal follow-up assessments, will be essential to clarify the robustness, durability, and generalizability of these preliminary and hypothesis-generating findings.

5. Conclusions

In summary, findings from this exploratory early cohort analysis of an ongoing randomized controlled trial suggest a preliminary and hypothesis-generating signal of benefit associated with SPT-SAFE in a school-based setting, rather than definitive evidence of efficacy. In the prespecified baseline-adjusted ANCOVA, suicidal ideation showed a between-group difference favoring SPT-SAFE, whereas the between-group effect for NSSI frequency was small and did not reach conventional statistical significance. Prespecified sensitivity analyses yielded directionally consistent patterns, indicating greater improvement over time in the SPT-SAFE group relative to TAU-RMC.

Importantly, both study arms incorporated systematic suicide risk assessment and structured safety planning, ensuring ethical rigor in work with a high-risk population and likely contributing to improvements observed across groups. Within this context, the present findings suggest that the integration of a symbolic–expressive, sandplay-based intervention into a structured suicide risk management framework may merit further empirical examination in school-based mental health services.

Definitive conclusions regarding comparative effectiveness, durability of treatment effects, and mechanisms of change will require analyses following completion of recruitment in this ongoing trial, inclusion of longer-term follow-up assessments, and evaluation of additional psychological outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J.K.; Methodology, H.J.K.; Formal analysis, H.J.K.; Investigation, H.J.K.; Writing—original draft, H.J.K.; Theoretical framework, U.K.A.; Interpretation of results, U.K.A.; Writing—review & editing, U.K.A.; Supervision, U.K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Both authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. Correspondence: U.K. Ahn; E-mail: ahnunkyoung@dankook.ac.kr.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dankook University (IRB No. DKU 2025-01-005-004; initial approval on 21 May 2025; amended approval on 11 December 2025), in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians of all participants, and written assent was obtained from all adolescent participants prior to study participation.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the sensitive nature of the data involving children and suicide-related clinical information, access to the dataset is strictly controlled. De-identified data may be made available to qualified researchers upon reasonable request, following approval by the Institutional Review Board. Data will be provided solely for academic research purposes, and any secondary use requires explicit ethical approval. No identifiable information is included, and data sharing complies with all applicable privacy and data protection regulations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Chungcheongnam-do Office of Education for their support in conducting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SPT-SAFE |

Sandplay Therapy with Suicidal Ideation and Self-Injury–Focused Engagement |

| TAU-RMC |

Treatment as Usual–Risk Management Counseling |

| NSSI |

Non-Suicidal Self-Injury |

| SIQ-JR |

Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire–Junior |

| FASM |

Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation |

References

- Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Claes, L.; Havertape, L.; Plener, P.L. International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2012, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swannell, S.V.; Martin, G.E.; Page, A.; Hasking, P.; St John, N.J. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 2014, 44, 273–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkevi, A.; Rotsika, V.; Arapaki, A.; Richardson, C. Adolescents’ self-reported suicide attempts, self-harm thoughts and their correlates across 17 European countries. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2012, 53, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Green, J.G.; Hwang, I.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Kessler, R.C. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.D.; Franklin, J.C.; Fox, K.R.; Bentley, K.H.; Kleiman, E.M.; Chang, B.P.; Nock, M.K. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine 2016, 46, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, P.; Kelvin, R.; Roberts, C.; Dubicka, B.; Goodyer, I. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT). American Journal of Psychiatry 2011, 168, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.J.; Jones, R.M.; Hare, T.A. The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2008, 1124, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2005, 9, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, C.R.; Franklin, J.C.; Nock, M.K. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 2015, 44, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ougrin, D.; Tranah, T.; Stahl, D.; Moran, P.; Asarnow, J.R. Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2015, 54, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerutti, R.; Zuffianò, A.; Spensieri, V. The Role of Difficulty in Identifying and Describing Feelings in Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Behavior (NSSI): Associations With Perceived Attachment Quality, Stressful Life Events, and Suicidal Ideation. Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, A. Developing Emotional Skills and the Therapeutic Alliance in Clients with Alexithymia: Intervention Guidelines. Psychopathology 2021, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalff, D.M. Sandplay: A psychotherapeutic approach to the psyche; Sigo Press: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Homeyer, L.E.; Sweeney, D.S. Sandtray therapy: A practical manual, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, H.; Ahn, U.; Lim, M. The clinical effects of school sandplay group therapy on general children with a focus on Korea Child & Youth Personality Test. BMC Psychology 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herce, N.; De Alda, I.; Marrodán, J. Sandtray and Sandplay in the Treatment of Trauma with Children and Adolescents: A Systemic Review. World Journal for Sand Therapy Practice® 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinrib, E.L. Images of the self: The sandplay therapy process; Temenos Press: Cloverdale, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.R.; Friedman, H.S. Sandplay: Past, present and future; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk, B.A. The body keeps the score: Memory and the evolving psychobiology of posttraumatic stress. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 1994, 1, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malchiodi, C.A. Creative interventions with traumatized children, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bratton, S.C.; Ray, D.; Rhine, T.; Jones, L. The efficacy of play therapy with children: A meta-analytic review of treatment outcomes. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 2005, 36, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, U.K.; Kwak, H.J. Clinical Effect of SPT in Adolescents Experiencing Suicidal Events. School Counselling and Sandplay 2022, 4, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E.D. The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review 2007, 27, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Prinstein, M.J. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2004, 72, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boik, B.L.; Goodwin, E.A. Sandplay therapy: A step-by-step manual for psychotherapists of diverse orientations; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky, E.D.; May, A.M.; Glenn, C.R. The relationship between nonsuicidal self-injury and attempted suicide: Converging evidence from four samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2013, 122, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, T.E. Why people die by suicide; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Amatruda, K. Sandplay therapy in vulnerable communities: A Jungian approach to posttraumatic stress; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky, E.D.; May, A.M. The Three-Step Theory (3ST): A new theory of suicide rooted in the ideation-to-action framework. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy 2015, 8, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Orden, K.A.; Witte, T.K.; Cukrowicz, K.C.; Braithwaite, S.R.; Selby, E.A.; Joiner, T.E. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review 2010, 117, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, L. Sandplay therapy and suicide: A Jungian perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jobes, D.A. Managing suicidal risk: A collaborative approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Posner, K.; Brown, G.K.; Stanley, B.; Brent, D.A.; Yershova, K.V.; Oquendo, M.A.; Currier, G.W.; Melvin, G.A.; Greenhill, L.; Shen, S.; Mann, J.J. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, B.; Brown, G.K. Safety planning intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 2012, 19, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, M.D.; Bryan, C.J.; Wertenberger, E.G. Brief cognitive-behavioral therapy effects on post-treatment suicide attempts: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, E.A.; Berk, M.S.; Asarnow, J.R.; Adrian, M. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with recurrent self-harm: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.N. Child and adolescent suicidal behavior: School-based prevention, assessment, and intervention, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Self-harm: Assessment, management and preventing recurrence (NICE Guideline NG225). NICE. Available at. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng225.

- Pettit, J.; Buitron, V.; Green, K. Assessment and Management of Suicide Risk in Children and Adolescents. Cognitive and behavioral practice 2018, 25, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Holmberg, E.B.; Photos, V.I.; Michel, B.D. Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview: Development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment 2007, 19, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, W.M. Psychometric characteristics of the Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire in college students. Journal of Personality Assessment 1991, 56, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel, M.; Hoagwood, K.; Stephan, S.; Ford, T. Mental health interventions in schools in high-income countries. The Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, C.; Bolton, S.L.; Katz, L.Y.; Isaak, C.; Tilston-Jones, T.; Sareen, J. A systematic review of school-based suicide prevention programs. Depression and Anxiety 2013, 30, 1030–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butcher, J.N.; Williams, C.L.; Graham, J.R.; Archer, R.P.; Tellegen, A.; Ben-Porath, Y.S.; Kaemmer, B. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–Adolescent (MMPI-A): Manual for administration, scoring, and interpretation; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, R.P.; Krishnamurthy, R. Essentials of MMPI-A assessment; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenfeld, M. The world technique; Allen & Unwin: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and crisis; W. W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, H.; Nurius, P. Possible selves. American Psychologist 1986, 41, 954–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, U.K.; Yasunobu, O.; Kwak, H.J. Overview: The beginning and Development of SP group therapy. (A Study on International Research Trends in SP Group Therapy). Psychological Counselling and Sandplay Therapy 2024, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, K.; Saunders, K.E.; O’Connor, R.C. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet 2012, 379, 2373–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latkin, C.A.; Edwards, C.; Davey-Rothwell, M.A.; Tobin, K.E. The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addictive Behaviors 2017, 73, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).