Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

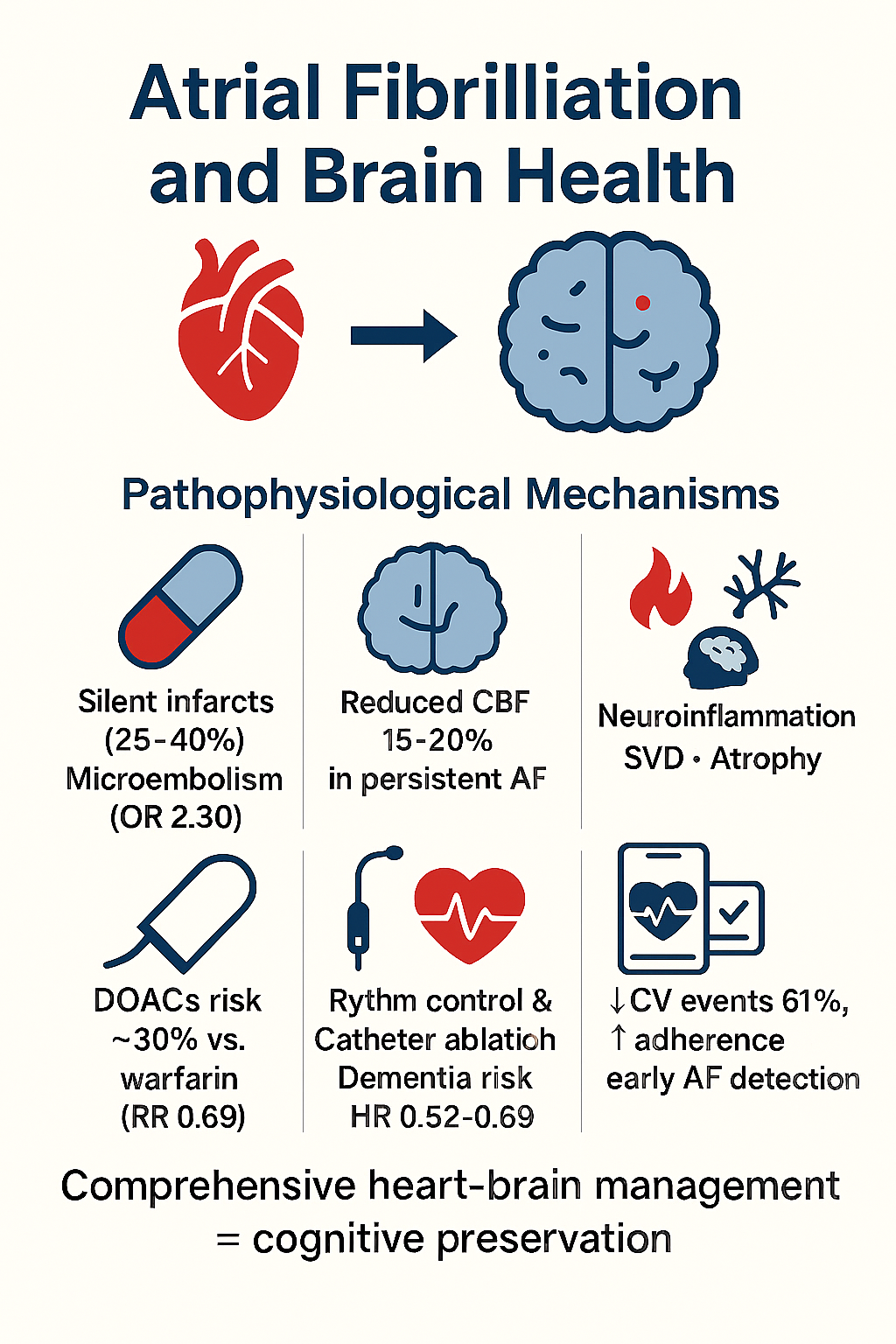

Background: Atrial fibrillation (AF) is independently associated with cognitive impairment and dementia through mechanisms extending far beyond traditional cardioembolic stroke risk. However, the relative contribution of distinct pathophysiological pathways and the efficacy of emerging therapeutic interventions for cognitive protection remain incompletely characterized. Objectives: This comprehensive review synthesizes current evidence on the epidemiology, pathophysiological mechanisms, therapeutic interventions (pharmacological, rhythm-control, and digital health), and research priorities addressing the AF–dementia relationship. Methods: A narrative review integrating evidence from observational studies, mechanistic research, randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses published through January 2026. Literature sources included MEDLINE/PubMed, major cardiology and neurology journals, and expert consensus statements. Searches used combinations of keywords: "atrial fibrillation," "cognitive decline," "dementia," "silent cerebral infarction," "cerebral hypoperfusion," "direct oral anticoagulants," "catheter ablation," and "digital health." Inclusion criteria encompassed studies examining the AF–cognition association, mechanistic pathways, therapeutic interventions with cognitive outcomes, and digital health technologies in AF management. Heterogeneous study designs prevented quantitative meta-analysis; qualitative synthesis focused on effect sizes, strength of evidence, and clinical implications. Results: Strong epidemiological evidence demonstrates that AF increases relative risk of dementia by 1.4–2.2 fold independently of clinical stroke, with silent cerebral infarction present in 25–40% of AF patients. Multiple interacting pathophysiological mechanisms account for AF-associated cognitive decline: cerebral microembolism (meta-analysis: OR 2.30 for silent infarction on MRI), chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (15–20% reduction in total cerebral blood flow in persistent AF), neuroinflammation, cerebral small vessel disease, and structural brain atrophy. Emerging therapeutic strategies offer complementary neuroprotective mechanisms: direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs)—particularly apixaban and rivaroxaban—reduce dementia risk by approximately 30% compared to warfarin (RR 0.69); rhythm control strategies and catheter ablation demonstrate dementia risk reduction (HR 0.52–0.69); and comprehensive digital health platforms implementing the ABC pathway reduce adverse cardiovascular events by 61% while optimizing adherence and enabling early AF detection. However, evidence-specific to cognitive endpoints remains limited, with the landmark BRAIN-AF trial showing no benefit of low-dose rivaroxaban in low-stroke-risk AF patients—suggesting that non-embolic mechanisms predominate in this population. Conclusions: AF represents a multifaceted threat to brain health requiring a paradigm shift from isolated stroke prevention toward comprehensive heart–brain health optimization. Integration of pharmacological neuroprotection (preferring DOACs), hemodynamic optimization (rhythm control in selected patients), cardiovascular risk factor management, and digital health technologies provides unprecedented opportunity for cognitive preservation. However, critical knowledge gaps persist regarding AF burden thresholds, the relative contribution of competing pathophysiological mechanisms, optimal anticoagulation strategies in low-risk populations, and the long-term cognitive benefits of emerging digital technologies. Prospective randomized clinical trials with cognitive impairment as a primary endpoint, serial neuroimaging, and diverse population representation are urgently needed to validate preventive strategies and refine therapeutic decision-making.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiological Burden and Clinical Significance

1.2. Limitations of Traditional Paradigm

1.3. Rationale for Comprehensive Review Approach

2. Epidemiology of Atrial Fibrillation and Cognitive Impairment

2.1. Prevalence and Incidence of Af-Associated Cognitive Decline

2.2. Independent Association with Dementia Risk

3. Pathophysiological Mechanisms Linking Atrial Fibrillation to Cognitive Decline

3.1. Cerebral Microembolism and Silent Brain Infarcts

- 2.30-fold increased odds of silent cerebral infarction on MRI (95% CI 1.44–3.68)

- 3.45-fold increased odds of silent cerebral infarction on CT (95% CI 2.03–5.87)

- 40% on MRI

- 22% on CT

3.2. Chronic Cerebral Hypoperfusion

3.3. Neuroinflammation and Systemic Inflammation

- Interleukin-1 (IL-1)

- Interleukin-8 (IL-8)

- Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)

- High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP)

- Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15)

3.4. Brain Structural Changes and Atrophy

- Reduced cortical thickness in multiple brain regions

- Decreased gray matter volume in cortical and subcortical structures

- Elevated extracellular free-water content indicating neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration

- Widespread white matter abnormalities consistent with small vessel pathology [8]

4. Therapeutic Strategies for Cognitive Protection in Atrial Fibrillation

4.1. Anticoagulation and Neuroprotection

4.1.1. Doacs Versus Warfarin: Evidence for Cognitive Benefit

4.1.2. The Brain-Af Trial: Limitations of Anticoagulation in Low-Risk Af

- Participants: 1,235 of intended 1,424 individuals with AF but without prior stroke/TIA and low thromboembolic risk (CHADS₂-VASc score 0–1, excluding female sex)

- Intervention: Rivaroxaban 15 mg daily versus placebo

- Follow-up: Median 3.7 years (trial halted early for futility)

-

Primary outcome: Composite of cognitive decline (≥2-point drop in Montreal Cognitive Assessment), stroke, or transient ischemic attack

- o Rivaroxaban: 7.0% annual event rate

- o Placebo: 6.4% annual event rate

- o Hazard ratio: 1.10 (95% CI 0.86–1.40, P = 0.46)[10]

4.2. Rhythm Control and Hemodynamic Optimization

- Improved cardiac output and cerebral perfusion: Restoration of atrial contribution to ventricular filling and elimination of the irregular ventricular response improves cardiac output and cerebral blood flow

- Reduced microemboli: Elimination or suppression of AF episodes reduces formation of atrial thrombi and microemboli

- Reduced neuroinflammation: Restoration of sinus rhythm and resolution of atrial remodeling reduce systemic and brain inflammatory markers [11]

4.3. Comprehensive Cardiovascular Risk Factor Management

5. Digital Health Technologies in Atrial Fibrillation Management

5.1. Remote Monitoring and Early Af Detection

5.1.1. Wearable Technologies and Smartwatch Algorithms

- Continuous or frequent rhythm monitoring

- Detection of asymptomatic (silent) AF episodes

- Early intervention before symptom development or extensive silent infarct accumulation

- Enrolled 419,297 participants

- Detected 2,161 (0.52%) participants with irregular pulse notification

- Among those who provided recordings, AF confirmed in 34%

- Demonstrated feasibility of population-scale AF screening via consumer wearables[13]

5.2. Mobile Health Platforms and the Abc Pathway

5.2.1. Abc Pathway Implementation

- Medication reminders and adherence tracking

- INR monitoring in warfarin users

- Bleeding risk assessment and monitoring

- Symptom tracking and severity assessment

- Rhythm monitoring data integration

- Blood pressure tracking with smart home devices

- Weight and physical activity monitoring

- Medication reminders[14]

5.2.2. Evidence for Effectiveness: Mafa-Ii Trial

- Participants: Approximately 2,000 AF patients

- Intervention: Mobile app with ABC pathway components vs. standard care

- Primary outcome: Composite adverse events

- 61% reduction in composite adverse cardiovascular events

- Hazard ratio: 0.37 (95% CI approximately 0.27–0.50)

- Benefits driven by improved anticoagulation adherence, blood pressure control, and symptom management [15]

5.3. Medication Adherence Optimization

5.3.1. Adherence Challenges and Digital Interventions

- Proportion of days covered (PDC) ≥80% ("good adherence"): Only 60–70% of AF patients on DOACs in routine practice

- Mean adherence: Approximately 77% across multiple real-world cohorts

- Non-adherence consequences: Associated with 39% increased hazard of ischemic stroke (HR 1.39, 95% CI 1.06–1.81) [16]

-

Prescription fill optimization:

- o 90-day prescription fills vs. 30-day fills: 75% increased odds of good adherence at 12 months (OR 1.75, 95% CI 1.54–1.97)

-

Smartphone app-based medication reminders:

- o Structured reminders at medication times improve adherence

- o Integration with wearables enhances engagement

-

Combined digital + human interventions:

- o Blended electronic app reminders + phone-based counseling for nonadherence

- o Face-to-face digital literacy education superior to app-based approaches [17]

5.4. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Af

5.4.1. Ai-Enhanced Ecg Analysis

- AF detection from sinus rhythm ECG: AI algorithms can identify patients likely to develop future AF before any arrhythmia is manifest [18]

- Interpretability challenges: "Black box" nature of deep neural networks limits clinical understanding of decision factors

5.4.2. Virtual Assistants and Chatbot Technology

- 24/7 patient support and education

- Medication reminders and adherence tracking

- Symptom assessment and triage

- Escalation to human healthcare provider when necessary

- High adherence rates to follow-up recommendations

- Reduced clinical workload (decreased phone calls and routine emails)

- Feasible for implementation in resource-limited settings [19]

6. Clinical Practice Recommendations

6.1. Anticoagulation Strategy

- DOAC preferability: In AF patients meeting anticoagulation criteria (CHA₂₂-VASc ≥2 men, ≥3 women), prefer DOACs (particularly apixaban, rivaroxaban) over warfarin when no contraindications exist, considering both stroke reduction and potential neuroprotection benefits.

-

Low-risk population management: In patients with very low stroke risk (CHA₂₂-VASc 0–1, excluding female sex), anticoagulation decision should incorporate:

- o Individual cognitive decline risk factors

- o Baseline cognitive status assessment

- o AF burden (if quantifiable via monitoring)

- o Bleeding risk

- o Patient preferences

-

Adherence optimization: Implement adherence-enhancing strategies:

- o 90-day prescription fills vs. 30-day

- o Smartphone app reminders

- o Face-to-face digital literacy education (most effective in elderly)

6.2. Arrhythmia Management Strategy

- Rate control as minimum standard: All AF patients should achieve adequate rate control at rest (60–80 bpm) and with exertion, as poor rate control impairs cardiac output and cerebral perfusion.

-

Rhythm control consideration: In selected patients, rhythm control via antiarrhythmic drugs or catheter ablation should be considered not solely for symptom relief but for hemodynamic benefit and cognitive preservation:

- o Candidates: AF patients ≥65 years with significant cognitive impairment risk

- o Early rhythm control (within 3 months of AF diagnosis) preferred

- Shared decision-making: Discuss with informed patients the potential cognitive benefits of rhythm control alongside symptomatic and hemodynamic benefits.

6.3. Comprehensive Cardiovascular Risk Factor Management

6.4. Digital Health Technology Integration

-

Wearable devices for AF detection:

- o Offer wearable-based AF screening to at-risk populations

- o Never use wearable detection as sole diagnostic modality; positive findings require ECG/rhythm confirmation

- o Educate patients on algorithm limitations and need for clinical follow-up

-

Mobile health ABC pathway implementation:

- o Implement mHealth platforms incorporating anticoagulation, symptom management, and cardiovascular risk factor control

- o Choose user-friendly platforms with demonstrated adherence benefits

- o Provide technical support and digital literacy education, especially for elderly users

-

Telemedicine for chronic AF follow-up:

- o Implement remote anticoagulation management for suitable patients (especially DOAC users)

- o Video-based follow-up annually or biannually appropriate for stable AF patients

6.5. Cognitive Assessment and Monitoring

-

Baseline cognitive screening:

- o Consider brief cognitive screening (Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Mini-Cog, or equivalent) in AF patients, particularly those ≥75 years

-

Serial cognitive evaluation:

- o Integrate cognitive assessment into routine AF follow-up, with repeat evaluation annually or biannually in high-risk patients

-

Neuroimaging consideration:

- o Consider baseline brain MRI in AF patients with cognitive decline to identify silent infarction burden and small vessel disease markers

7. Critical Research Gaps and Priorities

7.1. Cognitive Endpoints in Af Trials

- Objective cognitive testing (neuropsychological battery)

- Serial testing to measure cognitive trajectory

- Neuroimaging biomarkers (MRI for silent infarction, white matter disease, atrophy)

- Long follow-up (5+ years) for dementia diagnosis

- Diverse population representation

7.2. Af Burden and Cognitive Outcome Relationship

- Enrollment of AF patients with device-based AF burden quantification

- Baseline neuropsychological assessment and neuroimaging

- Prospective follow-up assessing whether AF burden predicts cognitive change

- Determination of potential threshold of AF burden at which cognitive decline risk increases substantially

7.3. Mechanistic Clarification Studies

- Microembolism vs. hypoperfusion: Design prospective studies measuring microembolic signal on transcranial Doppler during AF episodes and cerebral blood flow via advanced MRI sequences

- Inflammatory pathway specificity: Mechanistic studies clarifying which inflammatory mediators drive brain injury in AF and development of selective inhibitors

- Blood–brain barrier dysfunction: Imaging studies quantifying BBB integrity in AF patients (advanced MRI, PET) and correlation with cognitive impairment

7.4. Biomarker-Driven Risk Stratification

- Development and validation of cognitive decline risk prediction models

- Incorporation of clinical features, biomarkers (hsCRP, GDF-15, NfL, GFAP, phosphorylated tau), neuroimaging markers, and genetic factors

- Prospective validation in independent cohorts

- Development of stratified treatment strategies

7.5. Digital Health Long-Term Effectiveness

- Long-term follow-up (≥5 years) studies assessing whether sustained digital health engagement prevents cognitive decline

- Health equity substudies ensuring technology benefits reach underrepresented populations

- Cost-effectiveness analyses

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

8.1. Paradigm Shift: From Stroke Prevention to Heart–Brain Health

- AF independently affects cognitive health through multiple mechanisms beyond traditional cardioembolic stroke

- Therapeutic interventions (anticoagulation, rhythm control, risk factor management) address distinct cognitive neuroprotection pathways

- Digital technologies enable integrated monitoring of cardiac and cognitive health simultaneously

- Prevention strategies must begin early, before extensive irreversible brain injury accumulates

8.2. Clinical Synthesis and Therapeutic Integration

8.3. Future Integrated Heart–brain Health Platforms

- Continuous AF monitoring via wearable devices or implanted sensors

- Automated anticoagulation management with adherence tracking and INR/renal function monitoring

- Cardiovascular risk factor optimization (blood pressure, glucose, lipids, weight) via home monitoring devices

- Regular cognitive screening (validated brief instruments, voice-based AI analysis)

- Serial neuroimaging when appropriate (baseline and interval MRI assessing silent infarction burden, small vessel disease, brain atrophy)

- Coordinated care between cardiology and neurology specialists

- Early intervention protocols for detected cognitive decline

8.4. Conclusion

- Rigorous prospective research to validate preventive strategies and establish causality

- Mechanistic elucidation of pathways linking AF to brain injury, enabling targeted therapies

- Development of predictive biomarkers to identify highest-risk patients

- Intentional equity-focused strategies ensuring benefits reach all populations

- Clinician education emphasizing cognitive health as core therapeutic goal alongside stroke prevention

- Patient engagement in shared decision-making regarding comprehensive heart–brain health strategies

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diener, HC; Hart, RG; Koudstaal, PJ; Lane, DA; Lip, GYH. Atrial fibrillation and cognitive function. JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019, 73(5), 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivard, L; Friberg, L; Conen, D; et al. Atrial fibrillation and dementia: A report from the AF-SCREEN International Collaboration. Circulation 2022, 145(5), 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testai, FD; Gorelick, PB; Chuang, PY; et al. Cardiac contributions to brain health: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke 2024, 55(12), e425–e438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, N; Han, JK; Passman, R; et al. Promises and perils of consumer mobile technologies in cardiovascular care: JACC scientific statement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024, 83(5), 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, PC; Wen, MS; Chou, CC; Wang, CC; Hung, KC. Atrial fibrillation detection using ambulatory smartwatch photoplethysmography and validation with simultaneous Holter recording. Am Heart J. 2022, 247, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doehner, W; Boriani, G; Potpara, T; et al. Atrial fibrillation burden in clinical practice, research, and technology development: A clinical consensus statement of the European Society of Cardiology Council on Stroke and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace 2025, 27(3), euaf019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, LY; Chung, MK; Allen, LA; et al. Atrial fibrillation burden: Moving beyond atrial fibrillation as a binary entity: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 137(20), e623–e644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwennesen, HT; Andrade, JG; Wood, KA; Piccini, JP. Ablation to reduce atrial fibrillation burden and improve outcomes: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023, 82(10), 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, AM; Hashmi, AZ; Okoloumeweni, AO; et al. American Geriatrics Society position statement: Telehealth policy for older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2024, 73(12), 3646–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson Creber, R; Dodson, JA; Bidwell, J; et al. Telehealth and health equity in older adults with heart failure: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2023, 16(1), e000123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athreya, DS; Saczynski, JS; Gurwitz, JH; et al. Cognitive impairment and treatment strategy for atrial fibrillation in older adults: The SAGE-AF Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2024, 72(7), 2082–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamil, Y; Krishnaswami, A; Orkaby, AR; et al. The impact of cognitive impairment on cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2025, 85(25), 2472–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanastasiou, CA; Theochari, CA; Zareifopoulos, N; et al. Atrial fibrillation is associated with cognitive impairment, all-cause dementia, vascular dementia, and Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2021, 36(10), 3122–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, JY; Sunwoo, L; Kim, SW; Kim, KI; Kim, CH. CHADS-VASc score, cerebral small vessel disease, and frailty in older patients with atrial fibrillation. Sci Rep. 2020, 10(1), 18765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardarsdottir, M; Sigurdsson, S; Aspelund, T; et al. Atrial fibrillation is associated with decreased total cerebral blood flow and brain perfusion. Europace 2018, 20(8), 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marion, D; Li, Z; Roseborough, A; et al. Inflammation and cognitive decline: A population-based cohort study among aging adults with atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2025, 16, e039636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegmann, T; Joundi, RA; Srivastava, A; et al. Atrial fibrillation and atherosclerosis cause different vascular brain lesions on magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J. 2025, 17, ehaf550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, M; Chevalier, C; Naegele, FL; et al. Mapping the interplay of atrial fibrillation, brain structure, and cognitive dysfunction. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20(7), 4512–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y; Lane, DA; Wang, L; et al. Mobile health technology to improve care for patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020, 75(13), 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measurement | Persistent AF | Paroxysmal AF | No AF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cerebral blood flow (mL/min) | 472.1 | 512.3 | 541.0 |

| Brain tissue perfusion (mL/100 g/min) | 46.4 | 50.9 | 52.8 |

| Risk Factor | Target | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure | <130/80 mmHg | Reduces stroke and cognitive decline risk |

| LDL cholesterol | <70 mg/dL (high-risk) | Neuroprotective effects |

| HbA1c | 7–8% (individualized) | Intensive control associated with cognitive benefit |

| Smoking | Complete cessation | Critical for preventing vascular injury |

| Physical activity | ≥150 min/week moderate aerobic | Promotes cerebral blood flow |

| Sleep apnea | Screen and treat (CPAP) | Bidirectionally associated with AF and cognitive decline |

| Detection Method | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPG-based irregular rhythm | 97–100% | — | 84–98% |

| ECG-based smartwatch | 90–95% | 96–98% | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).