Submitted:

14 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

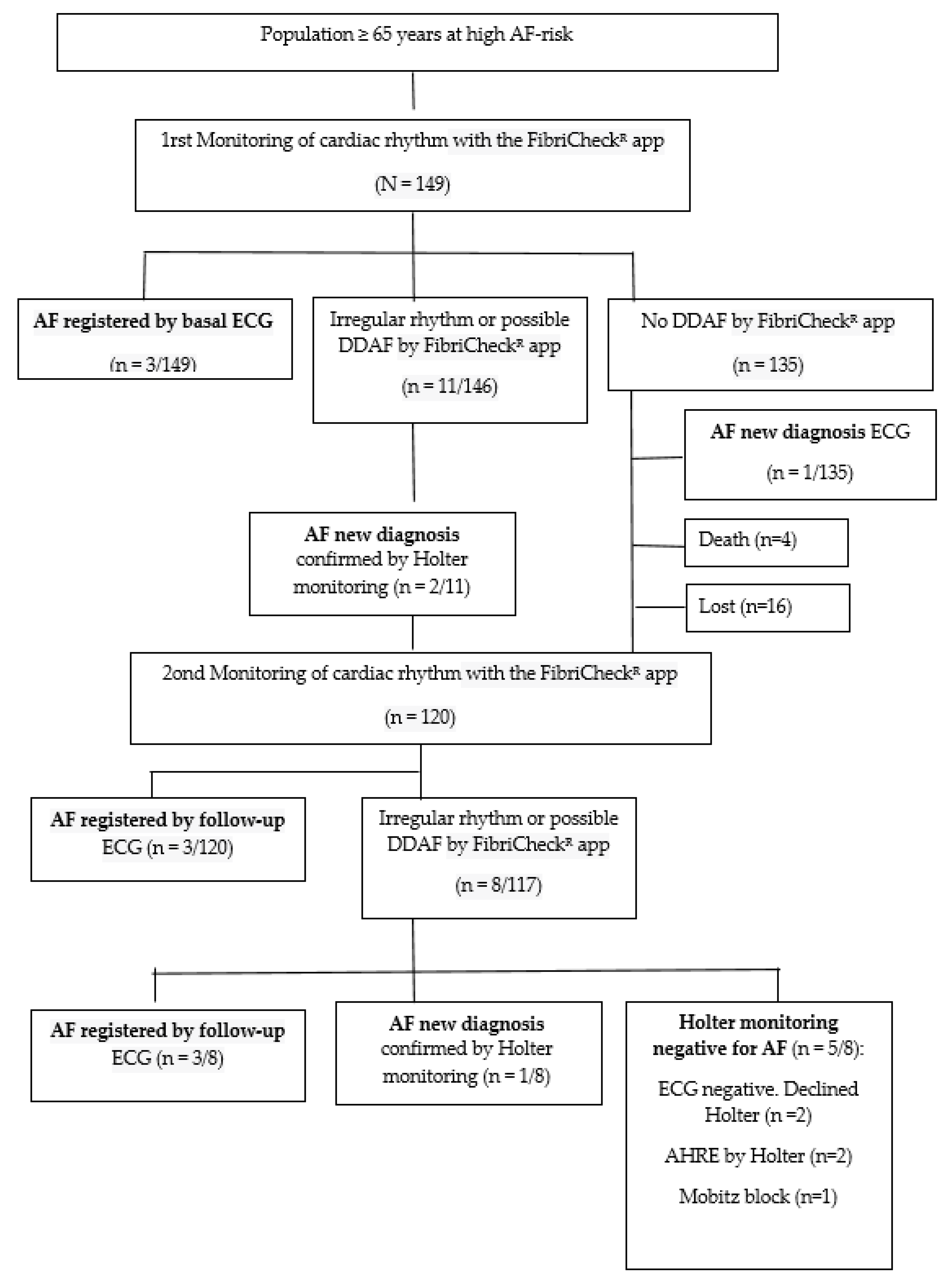

Background/Objectives: In Europe, the prevalence of AF is expected to increase 2.5-fold over the next 50 years with a lifetime risk of 1 in 3-5 individuals after the age of 55 years and a 34% rise in AF-related strokes. The PREFATE project investigates evidence gaps in the early detection of atrial fibrillation in high-risk populations within primary care. This study aims to estimate the prevalence of device-detected atrial fibrillation (DDAF) and assess the feasibility and impact of systematic screening in routine primary care. Methods: prospective cohort study (NCT 05772806) included 149 patients aged 65–85 years, identified as high-risk for AF. Participants underwent 14 days of cardiac rhythm monitoring using the Fibricheck® app, alongside evaluations with standard ECG and transthoracic echocardiography. The primary endpoint was a new AF diagnosis confirmed by ECG or Holter monitoring. Statistical analyses examined relationships between AF and clinical, echocardiographic, and biomarker variables. Results: A total of 18 cases (12.08%) were identified as positive for possible DDAF using FibriCheck® and 13 new cases of AF were diagnosed during follow-up, with a 71.4-fold higher probability of confirming AF in FibriCheck®-positive individuals than in FibriCheck®-negative individuals, resulting in a post-test odds of 87.7%. Significant echocardiographic markers of AF included reduced left atrial strain (<26%) and left atrial ejection fraction (<50%). MVP ECG risk scores ≥4 strongly predicted new AF diagnoses. However, inconsistencies in monitoring outcomes and limitations in current guidelines, particularly regarding AF burden, were observed. Conclusions: The study underscores the feasibility and utility of AF screening in primary care but identifies critical gaps in diagnostic criteria, anticoagulation thresholds, and guideline recommendations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection and Procedures

2.2.1. Electrocardiogram Study

2.2.2. Echocardiogram Study

2.2.3. External Monitoring FibricheckR

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Diagnosis of Atrial Fibrillation

3.2. ECG Variables: MVP ECG Risk Score ≥ 4

3.3. Echocardiography Study

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

Practical Implications and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- The World Health Organization. Global Burden of Stroke. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovasculardiseases#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- King’s College London for the Stroke Alliance for Europe. The Burden of Stroke in Europe; [(accessed on 1 January 2024)]. Atrial Fibrillation. Available online: https://strokeeurope.eu/ .

- Vinter N, Cordsen P, Johnsen S P, Staerk L, Benjamin E J, Frost L et al. Temporal trends in lifetime risks of atrial fibrillation and its complications between 2000 and 2022: Danish, nationwide, population based cohort study BMJ 2024; 385 :e077209. [CrossRef]

- Dominik Linz, Monika Gawalko, Konstanze Betz, Jeroen M. Hendriks, Gregory Y. H. Lip, Nicklas Vinter,l Yutao Guo, and Søren Johnsenh Atrial fibrillation: epidemiology, screening and digital health. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe 2024;37: 100786 https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.lanepe.2023. 100786.

- Luengo-Fernandez R, Violato M, Candio P, et al. Economic burden of stroke across Europe: A population-based cost analysis. European Stroke Journal. 2020;5(1):17–25. [CrossRef]

- Kalantarian S, Ay H, Gollub RL, et al. Association between atrial fibrillation and silent cerebral infarctions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:650–8. 10.7326/M14-0538.

- Sanders P, Pürerfellner H, Pokushalov E, Sarkar S, Di Bacco M, Maus B, Dekker LR; Reveal LINQ Usability Investigators. Performance of a new atrial fibrillation detection algorithm in a miniaturized insertable cardiac monitor: Results from the Reveal LINQ Usability Study. Heart Rhythm. 2016 Jul;13(7):1425-30. [CrossRef]

- an Gelder IC, Rienstra M, Bunting KV, Casado-Arroyo R, Caso V, Crijns HJGM, De Potter TJR, Dwight J, Guasti L, Hanke T, Jaarsma T, Lettino M, Løchen ML, Lumbers RT, Maesen B, Mølgaard I, Rosano GMC, Sanders P, Schnabel RB, Suwalski P, Svennberg E, Tamargo J, Tica O, Traykov V, Tzeis S, Kotecha D; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2024 Sep 29;45(36):3314-3414. [CrossRef]

- Proietti M, Romiti GF, Vitolo M, Borgi M, Rocco AD, Farcomeni A, et al. Epidemiology of subclinical atrial fibrillation in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices: a systematic review and meta-regression. Eur J Intern Med 2022;103:84–94. [CrossRef]

- Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, Benjamin EJ, Chyou JY, Cronin EM, Deswal A, Eckhardt LL, Goldberger ZD, Gopinathannair R, Gorenek B, Hess PL, Hlatky M, Hogan G, Ibeh C, Indik JH, Kido K, Kusumoto F, Link MS, Linta KT, Marcus GM, McCarthy PM, Patel N, Patton KK, Perez MV, Piccini JP, Russo AM, Sanders P, Streur MM, Thomas KL, Times S, Tisdale JE, Valente AM, Van Wagoner DR. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2023 Nov 30. [CrossRef]

- Boriani G, Glotzer TV, Santini M, WestTM, De Melis M, Sepsi M, et al. Device-detected atrial fibrillation and risk for stroke: an analysis of >10,000 patients from the SOS AF project (Stroke preventiOn Strategies based on Atrial Fibrillation information from implanted devices). Eur Heart J 2014;35:508–16. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre WF, Diederichsen SZ, Freedman B, Schnabel RB, Svennberg E, Healey JS. Screening for atrial fibrillation to prevent stroke: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Open. 2022 Jul 14;2(4):oeac044. [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.C., Nguyen, T.N. & Chow, C.K. Global implementation and evaluation of atrial fibrillation screening in the past two decades – a narrative review. npj Cardiovasc Health 1, 17 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Svennberg E, Friberg L, Frykman V, Al-Khalili F, Engdahl J, Rosenqvist M. Clinical outcomes in systematic screening for atrial fibrillation (STROKESTOP): a multicentre, parallel group, unmasked, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2021 Oct 23;398(10310):1498-1506. [CrossRef]

- Corica B, Bonini N, Imberti JF, et al. Yield of diagnosis and risk of stroke with screening strategies for atrial fibrillation: a comprehensive review of current evidence. Eur Hear J open. 2023;3(2). [CrossRef]

- Lopes RD, Atlas SJ, Go AS, et al. Effect of Screening for Undiagnosed Atrial Fibrillation on Stroke Prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. Published online September 2024. [CrossRef]

- Himmelreich JCL, Veelers L, Lucassen WAM, et al. Prediction models for atrial fibrillation applicable in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 2020;22:684–94. 10.1093/europace/euaa005.

- Engler D., Hanson C.L., Desteghe L., Boriani G., Diederichsen S.Z., Freedman B., et al. AFFECT-EU investigators Feasible approaches and implementation challenges to atrial fibrillation screening: a qualitative study of stakeholder views in 11 European countries. BMJ Open. 2022;12: e059156. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pinilla A, Clua-Espuny JL, Satué-Gracia EM, Pallejà-Millán M, Martín-Luján FM; PREFA-TE Study-Group. Protocol for a multicentre and prospective follow-up cohort study of early detection of atrial fibrillation, silent stroke and cognitive impairment in high-risk primary care patients: the PREFA-TE study. BMJ Open. 2024 Feb 19;14(2):e080736. [CrossRef]

- Bayés de Luna A, Escobar-Robledo LA, Aristizabal D, Weir Restrepo D, Mendieta G, Massó van Roessel A, Elosua R, Bayés-Genís A, Martínez-Sellés M, Baranchuk A. Atypical advanced interatrial blocks: Definition and electrocardiographic recognition. J Electrocardiol. 2018 Nov-Dec;51(6):1091-1093. [CrossRef]

- Gentille-Lorente D, Hernández-Pinilla A, Satue-Gracia E, Muria-Subirats E, Forcadell-Peris MJ, Gentille-Lorente J, Ballesta-Ors J, Martín-Lujan FM, Clua-Espuny JL. Echocardiography and Electrocardiography in Detecting Atrial Cardiomyopathy: A Promising Path to Predicting Cardioembolic Strokes and Atrial Fibrillation. J Clin Med. 2023 Nov 26;12(23):7315. [CrossRef]

- Clua-Espuny JL, Molto-Balado P, Lucas-Noll J, Panisello-Tafalla A, Muria-Subirats E, Clua-Queralt J, Queralt-Tomas L, Reverté-Villarroya S, Investigators Ebrictus Research. Early Diagnosis of Atrial Fibrillation and Stroke Incidence in Primary Care: Translating Measurements into Actions-A Retrospective Cohort Study. Biomedicines. 2023 Apr 7;11(4):1116. [CrossRef]

- Fibricheck App (https://www.fibricheck.com/clinical-studies/), last accessed Nov/01/2024].

- Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Castella M, Dan GA, Dilaveris PE, Fauchier L, Filippatos G, Kalman JM, La Meir M, Lane DA, Lebeau JP, Lettino M, Lip GYH, Pinto FJ, Thomas GN, Valgimigli M, Van Gelder IC, Van Putte BP, Watkins CL; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021 Feb 1;42(5):373-498. [CrossRef]

- Alexander B., Milden J., Hazim B., Haseeb S., Bayes-Genis A., Elosua R., Martínez-Sellés M., Yeung C., Hopman W., de Luna A.B., et al. New electrocardiographic score for the prediction of atrial fibrillation: The MVP ECG risk score (morphology-voltage-P-wave duration) Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2019;24:e12669. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell C., Rahko P.S., Blauwet L.A., Canaday B., Finstuen J.A., Foster M.C., Horton K., Ogunyankin K.O., Palma R.A., Velazquez E.J. Guidelines for Performing a Comprehensive Transthoracic Echocardiographic Examination in Adults: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2018;32:1–64. [CrossRef]

- Badano L.P., Kolias T.J., Muraru D., Abraham T.P., Aurigemma G., Edvardsen T., D’Hooge J., Donal E., Fraser A.G., Marwick T., et al. Standardization of left atrial, right ventricular, and right atrial deformation imaging using two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography: A consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2018;19:591–600. [CrossRef]

- Alhakak A.S., Biering-Sørensen S.R., Møgelvang R., Modin D., Jensen G.B., Schnohr P., Iversen A.Z., Svendsen J.H., Jespersen T., Gislason G., et al. Usefulness of left atrial strain for predicting incident atrial fibrillation and ischaemic stroke in the general population. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2022;23:363–371. [CrossRef]

- Pathan F., D’Elia N., Nolan M.T., Marwick T.H., Negishi K. Normal Ranges of Left Atrial Strain by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017;30:59–70. [CrossRef]

- Svennberg E, Tjong F, Goette A, Akoum N, Di Biase L, Bordachar P, Boriani G, Burri H, Conte G, Deharo JC, Deneke T, Drossart I, Duncker D, Han JK, Heidbuchel H, Jais P, de Oliviera Figueiredo MJ, Linz D, Lip GYH, Malaczynska-Rajpold K, Márquez M, Ploem C, Soejima K, Stiles MK, Wierda E, Vernooy K, Leclercq C, Meyer C, Pisani C, Pak HN, Gupta D, Pürerfellner H, Crijns HJGM, Chavez EA, Willems S, Waldmann V, Dekker L, Wan E, Kavoor P, Turagam MK, Sinner M. How to use digital devices to detect and manage arrhythmias: an EHRA practical guide. Europace. 2022 Jul 15;24(6):979-1005. doi: 10.1093/europace/euac038. Erratum in: Europace. 2022 Jul 15;24(6):1005. [CrossRef]

- Lowres N, Neubeck L, Redfern J, Ben Freedman S. Screening to identify unknown atrial fibrillation: A systematic review. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110: 213–222. [CrossRef]

- Ballesta-Ors J, Clua-Espuny JL, Gentille-Lorente DI, Lechuga-Duran I, Fernández-Saez J, Muria-Subirats E, Blasco-Mulet M, Lorman-Carbo B, Alegret JM. Results, barriers and enablers in atrial fibrillation case finding: barriers in opportunistic atrial fibrillation case finding-a cross-sectional study. Fam Pract. 2020 Sep 5;37(4):486-492. [CrossRef]

- Goudis C, Daios S, Dimitriadis F, Liu T. CHARGE-AF: A Useful Score For Atrial Fibrillation Prediction? Curr Cardiol Rev. 2023;19(2):e010922208402. [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain AM, Agarwal SK, Folsom AR, Soliman EZ, Chambless LE, Crow R, Ambrose M, Alonso A. A clinical risk score for atrial fibrillation in a biracial prospective cohort (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities [ARIC] study). Am J Cardiol. 2011 Jan;107(1):85-91. [CrossRef]

- Palà E, Bustamante A, Clúa-Espuny JL, Acosta J, González-Loyola F, Santos SD, Ribas-Segui D, Ballesta-Ors J, Penalba A, Giralt M, Lechuga-Duran I, Gentille-Lorente D, Pedrote A, Muñoz MÁ, Montaner J. Blood-biomarkers and devices for atrial fibrillation screening: Lessons learned from the AFRICAT (Atrial Fibrillation Research In CATalonia) study. PLoS One. 2022 Aug 23;17(8):e0273571. [CrossRef]

- Nadarajah R, Alsaeed E, Hurdus B, Aktaa S, Hogg D, Bates MGD, Cowan C, Wu J, Gale CP. Prediction of incident atrial fibrillation in community-based electronic health records: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Heart. 2022 Jun 10;108(13):1020-1029. [CrossRef]

- Himmelreich JCL, Veelers L, Lucassen WAM, Schnabel RB, Rienstra M, van Weert HCPM, Harskamp RE. Prediction models for atrial fibrillation applicable in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2020 May 1;22(5):684.

- Ahmed H, Ismayl M, Palicherla A, Kashou A, Dufani J, Goldsweig A, Anavekar N, Aboeata A. Outcomes of Device-detected Atrial High-rate Episodes in Patients with No Prior History of Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2024 Jun 18;13:e09. [CrossRef]

- Shaan Khurshid, Jeffrey S. Healey, William F. McIntyre,, and Steven A. Lubitz. Population-Based Screening for Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation Research (2020) Volume 127, Number 1 https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.316341.

- Schnabel RB, Marinelli EA, Arbelo E, Boriani G, Boveda S, Buckley CM, Camm AJ, Casadei B, Chua W, Dagres N, de Melis M, Desteghe L, Diederichsen SZ, Duncker D, Eckardt L, Eisert C, Engler D, Fabritz L, Freedman B, Gillet L, Goette A, Guasch E, Svendsen JH, Hatem SN, Haeusler KG, Healey JS, Heidbuchel H, Hindricks G, Hobbs FDR, Hübner T, Kotecha D, Krekler M, Leclercq C, Lewalter T, Lin H, Linz D, Lip GYH, Løchen ML, Lucassen W, Malaczynska-Rajpold K, Massberg S, Merino JL, Meyer R, Mont L, Myers MC, Neubeck L, Niiranen T, Oeff M, Oldgren J, Potpara TS, Psaroudakis G, Pürerfellner H, Ravens U, Rienstra M, Rivard L, Scherr D, Schotten U, Shah D, Sinner MF, Smolnik R, Steinbeck G, Steven D, Svennberg E, Thomas D, True Hills M, van Gelder IC, Vardar B, Palà E, Wakili R, Wegscheider K, Wieloch M, Willems S, Witt H, Ziegler A, Daniel Zink M, Kirchhof P. Early diagnosis and better rhythm management to improve outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: the 8th AFNET/EHRA consensus conference. Europace. 2023 Feb 8;25(1):6-27. [CrossRef]

- Andrade JG, Deyell MW, Macle L, Wells GA, Bennett M, Essebag V, Champagne J, Roux JF, Yung D, Skanes A, Khaykin Y, Morillo C, Jolly U, Novak P, Lockwood E, Amit G, Angaran P, Sapp J, Wardell S, Lauck S, Cadrin-Tourigny J, Kochhäuser S, Verma A; EARLY-AF Investigators. Progression of Atrial Fibrillation after Cryoablation or Drug Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2023 Jan 12;388(2):105-116. [CrossRef]

- Gruwez H, Ezzat D, Van Puyvelde T, Dhont S, Meekers E, Bruckers L, Wouters F, Kellens M, Van Herendael H, Rivero-Ayerza M, Nuyens D, Haemers P, Pison L. Real-world validation of smartphone-based photoplethysmography for rate and rhythm monitoring in atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2024 Mar 30;26(4):euae065. [CrossRef]

- Katrin Kemp Gudmundsdottir, Emma Svennberg, Leif Friberg , Tove Hygrell, Viveka Frykman, Faris Al-Khalili, Ziad Hijazi, Marten Rosenqvist, and Johan Engdahl. Randomized Invitation to Systematic NT-proBNP and ECG Screening in 75-Year Olds to Detect Atrial Fibrillation -STROKESTOP II. [CrossRef]

- Petzl AM, Jabbour G, Cadrin-Tourigny J, Pürerfellner H, Macle L, Khairy P, Avram R, Tadros R. Innovative approaches to atrial fibrillation prediction: should polygenic scores and machine learning be implemented in clinical practice? Europace. 2024 Aug 3;26(8):euae201. [CrossRef]

- Sivanandarajah P, Wu H, Bajaj N, Khan S, Ng FS. Is machine learning the future for atrial fibrillation screening? Cardiovasc Digit Health J. 2022 May 16;3(3):136-145. [CrossRef]

- Nadarajah R, Wahab A, Reynolds C, Raveendra K, Askham D, Dawson R, Keene J, Shanghavi S, Lip GYH, Hogg D, Cowan C, Wu J, Gale CP. Future Innovations in Novel Detection for Atrial Fibrillation (FIND-AF): pilot study of an electronic health record machine learning algorithm-guided intervention to identify undiagnosed atrial fibrillation. Open Heart. 2023 Sep;10(2):e002447. [CrossRef]

- R. Subash, T. Kongnakorn, R. Jhanjee. R. Mokgokong. EE454 Cost-Effectiveness of Screening for Atrial Fibrillation Utilizing the Unafied-7 Algorithm Versus Usual Care in Individuals Aged 65 from a US Payer Perspective. Value in Health, 2024 Volume 26, Issue 6, S142. [CrossRef]

- Elosua R., Escobar-Robledo L.A., Massó-van Roessel A., Martínez-Sellés M., Baranchuk A., Bayés-de-Luna A. ECG patterns of typical and atypical advanced interatrial block: prevalence and clinical relevance. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2021;74:807–810. [CrossRef]

- Noseworthy P.A., Attia Z.I., Behnken E.M., Giblon R.E., Bews K.A., Liu S., et al. Artificial intelligence-guided screening for atrial fibrillation using electrocardiogram during sinus rhythm: a prospective non-randomised interventional trial. Lancet. 2022;400:1206–1212. [CrossRef]

- Donal E, Lip GY, Galderisi M, Goette A, Shah D, Marwan M, Lederlin M, Mondillo S, Edvardsen T, Sitges M, Grapsa J, Garbi M, Senior R, Gimelli A, Potpara TS, Van Gelder IC, Gorenek B, Mabo P, Lancellotti P, Kuck KH, Popescu BA, Hindricks G, Habib G, Cardim NM, Cosyns B, Delgado V, Haugaa KH, Muraru D, Nieman K, Boriani G, Cohen A. EACVI/EHRA Expert Consensus Document on the role of multi-modality imaging for the evaluation of patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016 Apr;17(4):355-83. [CrossRef]

- Palà E, Bustamante A, Clúa-Espuny JL, Acosta J, González-Loyola F, Santos SD, Ribas-Segui D, Ballesta-Ors J, Penalba A, Giralt M, Lechuga-Duran I, Gentille-Lorente D, Pedrote A, Muñoz MÁ, Montaner J. Blood-biomarkers and devices for atrial fibrillation screening: Lessons learned from the AFRICAT (Atrial Fibrillation Research In CATalonia) study. PLoS One. 2022 Aug 23;17(8):e0273571. [CrossRef]

- Palà E, Bustamante A, Pagola J, Juega J, Francisco-Pascual J, Penalba A, Rodriguez M, De Lera Alfonso M, Arenillas JF, Cabezas JA, Pérez-Sánchez S, Moniche F, de Torres R, González-Alujas T, Clúa-Espuny JL, Ballesta-Ors J, Ribas D, Acosta J, Pedrote A, Gonzalez-Loyola F, Gentile Lorente D, Ángel Muñoz M, Molina CA, Montaner J. Blood-Based Biomarkers to Search for Atrial Fibrillation in High-Risk Asymptomatic Individuals and Cryptogenic Stroke Patients. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Jul 4;9:908053. [CrossRef]

- Schmalstieg-Bahr K, Gladstone DJ, Hummers E, Suerbaum J, Healey JS, Zapf A, Köster D, Werhahn SM, Wachter R. Biomarkers for predicting atrial fibrillation: An explorative sub-analysis of the randomised SCREEN-AF trial. Eur J Gen Pract. 2024 Dec;30(1):2327367. [CrossRef]

- Hisashi Ogawa,Yoshimori An,Syuhei Ikeda,Yuya Aono,Kosuke Doi, Mitsuru Ishii,Moritake Iguchi, Nobutoyo Masunaga, Masahiro Esato,Hikari Tsuji, Hiromichi Wada, Koji Hasegawa, Mitsuru Abe, Gregory Y.H. Lip, and Masaharu Akao,on behalf of the Fushimi AF Registry Investigators. Progression From Paroxysmal to Sustained Atrial Fibrillation Is Associated With Increased Adverse Events. Stroke 2018 Sept 18 Volume 49, Number 10 https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021396.

- Paulus Kirchhof, M.D., Tobias Toennis, M.D., Andreas Goette, M.D., A. John Camm, M.D., Hans Christoph Diener, M.D., Nina Becher, M.D., Emanuele Bertaglia, M.D., Carina Blomstrom Lundqvist, M.D., Martin Borlich, M.D., Axel Brandes, M.D., Nuno Cabanelas, M.D., Melanie Calvert, Ph.D., et al., for the NOAH-AFNET 6 Investigators* Anticoagulation with Edoxaban in Patients with Atrial High-Rate Episodes. N Engl J Med 2023; 389:1167-1179. [CrossRef]

- Healey JS, Lopes RD, Granger CB, Alings M, Rivard L, McIntyre WF, Atar D, Birnie DH, Boriani G, Camm AJ, Conen D, Erath JW, Gold MR, Hohnloser SH, Ip J, Kautzner J, Kutyifa V, Linde C, Mabo P, Mairesse G, Benezet Mazuecos J, Cosedis Nielsen J, Philippon F, Proietti M, Sticherling C, Wong JA, Wright DJ, Zarraga IG, Coutts SB, Kaplan A, Pombo M, Ayala-Paredes F, Xu L, Simek K, Nevills S, Mian R, Connolly SJ; ARTESIA Investigators. Apixaban for Stroke Prevention in Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2024 Jan 11;390(2):107-117. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre WF, Benz AP, Becher N, Healey JS, Granger CB, Rivard L, Camm AJ, Goette A, Zapf A, Alings M, Connolly SJ, Kirchhof P, Lopes RD. Direct Oral Anticoagulants for Stroke Prevention in Patients With Device-Detected Atrial Fibrillation: A Study-Level Meta-Analysis of the NOAH-AFNET 6 and ARTESiA Trials. Circulation. 2024 Mar 26;149(13):981-988. [CrossRef]

- Svendsen JH, Diederichsen SZ, Højberg S, Krieger DW, Graff C, Kronborg C, Olesen MS, Nielsen JB, Holst AG, Brandes A, Haugan KJ, Køber L. Implantable loop recorder detection of atrial fibrillation to prevent stroke (The LOOP Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2021 Oct 23;398(10310):1507-1516. [CrossRef]

- Prashanthan Sanders, Emma Svennberg, Søren Z Diederichsen, Harry J G M Crijns, Pier D Lambiase, Giuseppe Boriani, Isabelle C Van Gelder, Great debate: device-detected subclinical atrial fibrillation should be treated like clinical atrial fibrillation, European Heart Journal, Volume 45, Issue 29, 1 August 2024, Pages 2594–2603, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae365.

- Imberti, J.F.; Bonini, N.; Tosetti, A.; Mei, D.A.; Gerra, L.; Malavasi, V.L.; Mazza, A.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Boriani, G. Atrial High-Rate Episodes Detected by Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices: Dynamic Changes in Episodes and Predictors of Incident Atrial Fibrillation. Biology 2022, 11, 443. [CrossRef]

- Jeff S. Healey, M.D., Stuart J. Connolly, M.D., Michael R. Gold, M.D., Carsten W. Israel, M.D., Isabelle C. Van Gelder, M.D., Alessandro Capucci, M.D., C.P. Lau, M.D., +8, for the ASSERT Investigators*. Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation and the Risk of Stroke. January 12, 2012. N Engl J Med 2012; 366(2):120-129. [CrossRef]

- Isabelle C. Van Gelder, Jeff S. Healey, Harry J.G.M. Crijns, Jia Wang, Stefan H. 79.Hohnloser, Michael R. Gold, Alessandro Capucci, Chu-Pak Lau, Carlos A. Morillo, Anne H. Hobbelt, Michiel Rienstra, Stuart J. Connolly, Duration of device-detected subclinical atrial fibrillation and occurrence of stroke in ASSERT, European Heart Journal, Volume 38, Issue 17, 1 May 2017, Pages 1339–1344. [CrossRef]

- Becher N, Toennis T, Bertaglia E, et al. Anticoagulation with edoxaban in patients with long atrial high-rate episodes ≥24 h. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(10):837-849. [CrossRef]

- Nina Becher, Andreas Metzner, Tobias Toennis, Paulus Kirchhof, Renate B Schnabel, Atrial fibrillation burden: a new outcome predictor and therapeutic target, Eur Heart J. 14 August 2024;45(31):2824–2838, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae373.

- Tiver KD, Quah J, Lahiri A, Ganesan AN, McGavigan AD. Atrial fibrillation burden: an update-the need for a CHA2DS2-VASc-AFBurden score. Europace. 2021 May 21;23(5):665-673. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan RM, Koehler J, Ziegler PD, Sarkar S, Zweibel S, Passman RS. Stroke Risk as a Function of Atrial Fibrillation Duration and CHA2DS2-VASc Score. Circulation. 2019 Nov 12;140(20):1639-1646. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.B., Brøndum, R.F., Nøhr, A.K. et al. Risk of stroke in male and female patients with atrial fibrillation in a nationwide cohort. Nat Commun 15, 6728 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Verma A, Ha ACT, Kirchhof P, et al. The Optimal Anti-Coagulation for Enhanced-Risk Patients Post-Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation (OCEAN) trial. Am Heart J. 2018;197:124-132. [CrossRef]

- Lorman-Carbó B, Clua-Espuny JL, Muria-Subirats E, Ballesta-Ors J, González-Henares MA, Fernández-Sáez J, Martín-Luján FM; on behalf Ebrictus Research Group. Complex chronic patients as an emergent group with high risk of intracerebral haemorrhage: an observational cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2021 Feb 5;21(1):106. [CrossRef]

- Mette Søgaard, Martin Jensen, Anette Arbjerg Højen, Torben Bjerregaard Larsen, Gregory Y.H. Lip, Anne Gulbech Ording, and Peter Brønnum Nielsen. Net Clinical Benefit of Oral Anticoagulation Among Frail Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Nationwide Cohort Study. Stroke (2024) Volume 55, Issue 2, February 2024; Pages 413-422. [CrossRef]

- Gauthier A, Lagarde C, Mourey F, Manckoundia P. Use of Digital Tools, Social Isolation, and Lockdown in People 80 Years and Older Living at Home. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Mar 2;19(5):2908. [CrossRef]

- Moltó-Balado, P.; Reverté-Villarroya, S.; Alonso-Barberán, V.; Monclús-Arasa, C.; Balado-Albiol, M.T.; Clua-Queralt, J.; Clua-Espuny, J.-L. Machine Learning Approaches to Predict Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Atrial Fibrillation. Technologies 2024, 12, 13. [CrossRef]

| Variables | All (%) | AF* | No-AF | p-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 149 | 13 (8.7) | 136 (91.2) | |

| General information | ||||

| Age (years) | 74.7(5.11) | 73.46(6.21) | 74.9±5.0 | 0.319 |

| Women | 96 (64.4) | 6(6.2) | 90(93.7) | 0.224 |

| Men | 53 (35.3) | 7(13.2) | 46(86.8) | |

| BMI2 (Kg/m2) | 31.94(5.50) | 33.5(7.61) | 31.8(4.9) | 0.290 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Active smoking | 13 (8.8) | 1(0.7) | 12(8.1) | 0.999 |

| Hypertension | 133 (89.9) | 13(100) | 120(80.5) | 0.363 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 113 (76.4) | 9(69.2) | 104(69.7) | 0.507 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 76 (51.4) | 8(61.5) | 68(50.0) | 0.556 |

| Chronic Renal Failure | 36 (24.3) | 2(25.0) | 34(22.3) | 0.735 |

| Myocardial ischemia | 23 (15.5) | 1(7.7) | 22(14.9) | 0.695 |

| Peripheral Vascular disease | 13 (6.70) | 3(23.0) | 10(7.3) | 0.090 |

| Heart Failure | 16 (10.73) | 1(7.7) | 15(11.0) | 0.999 |

| Diagnosis of valvular heart disease | 9 (6.1) | - | 9(6.1) | 0.999 |

| Pharmacological treatment | ||||

| HTA treatment | 126 (84.5) | 11(84.6) | 115(84.5) | 0.943 |

| Statins treatment | 82 (55.03) | 7(53.8) | 75(55.1) | 0.999 |

| Diabetes treatment | 67 (44.96) | 8(61.5) | 59(43.3) | 0.375 |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 41 (27.51) | 5(38.4) | 36(26.4) | 0.350 |

| Cardiological exploratory parameters | ||||

| CHA2DS2VA score | 3.9(1.04) | 3.9(0.8) | 3.97±1.0 | 0.876 |

| MVP ECG risk score | 3.3(1.4) | 4.4(1.1) | 3.2(1.4) | 0.003 |

| Interatrial block (IAB) | 33 (22.1) | 7(53.8) | 26(19.1) | 0.006 |

| LA-reservoir Strain (%) | 28.5(9.92) | 20.4(13.7) | 29.5(9.1) | 0.003 |

| 2D-LA-FE (%) | 51.6(12.68) | 39.4(13.4) | 52.8(11.8) | <0.001 |

| LA indexed Vol (mL/m2) | 30.3(9.03) | 39.0(9.3) | 29.4(8.7) | < 0.001 |

| NT-Pro-BNP | 226.2 (300.6) | 250.6(256.5) | 217.6(304.5) | 0.77 |

| Clinical scores | ||||

| Pfeiffer score | 0.90(1.2) | 1.5(1.4) | 1.0(1.2) | 0.166 |

| Fazecas score | 0.84(0.82) | 0.83(0.8) | 0.84(0.8) | 0.965 |

| Fibricheck-measures | 32.8(19.5) | 29.5(16.8) | 33.2(19.8) | 0.523 |

| Case identifier |

CHA2Ds2VA score |

Basal MVP ECG risk score2 | LA-reservoir Strain (%) | 2D-LA-Ejection fraction (%) | LA-index Volume (mL/m2) | Fibricheck_AF (%) (Number of measures)-(rhythm interpretation)* |

Diagnosis confirmed (ECG or Holter) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1rst Monitoring 2023 |

2ond Monitoring 2024 |

|||||||

| FATE003 | 4 | 2/AF | 3.7 | 33.4 | 53.8 | 100% [AF] | AF (basal ECG) | |

| FATE019 | 3 | 5 | 34.2 | 59.5 | 29.3 | 0% (11)- [APC] | 9,4% (32)- [AF] | AF (Holter) |

| FATE021 | 5 | 5/AF | 2.2 | 10.0 | 54.1 | 100% [AF] | AF (basal ECG) | |

| FATE031 | 5 | 4 | 16.4 | 45.0 | 28.0 | 2% (51)- [AF] | 0.0% (68) -[APC] | 2* (Holter) |

| FATE033 | 5 | 5 | 5.0 | 30.0 | 32.7 | 100% [AF] | AF (basal ECG) | |

| FATE050 | 3 | 4 | - | - | 38.0 | 14.7% (34)- [AF] | AF (Holter) | |

| FATE051 | 4 | 3 | - | - | - | 0% (30)- [APC] | 14.3% (7)- [AF] | No confirmed by ECG declined Holter |

| FATE054 | 3 | 3 | 36.2 | 54.2 | 16.8 | 0% (29)- [SR] | 5.0% (20)- [AF] | 3* (Holter) |

| FATE064 | 4 | 5 | - | - | - | 3.3% (30)- [AF] | 0.0% (17)- [SR] | |

| FATE067 | 6 | 6 | 12.3 | 32.0 | 54.9 | 0% (31)- [SR] | 4.3 (23)- [AF] | Flutter (follow-up ECG) |

| FATE068 | 4 | 5 | 16.6 | 35.0 | 30.7 | 14.3% (35)- [AF] | AF (Holter LA Mixoma) | |

| FATE074 | 4 | 5 | 16.8 | 56.0 | 32.0 | 37.8% (37)- [AF] | 23.1% (39)- [AF] | No confirmed by ECG declined Holter |

| FATE075 | 3 | 5 | - | - | - | 33.2% (205)- [AF] | 36.1% (36)- [AF] | 3*(Holter) |

| FATE076 | 3 | 6 | 24.4 | 45 | 32.4 | 0% (27) [IEB] | 1,4% (29) [AF] | AF (Holter) |

| FATE092 | 5 | 5 | 19.4 | 50.0 | 36.0 | 1.4% (38) [IEB] | 52.6% (10) [AF] | AF (foll0w-up ECG) |

| FATE094 | 4 | 4 | 34.4 | 56.0 | 33.2 | 0% (22)[IEB] | 63.6% (11) [AF] | AF (follow-up ECG) |

| FATE116 | 3 | 4 | 47.0 | 46.0 | 29.4 | 0% (26) [IEB] | Flutter (basal ECG) | |

| FATE132 | 3 | 5/AF | 18.4 | 29.0 | 43.8 | 64% (25) [AF] | AF (follow-up ECG ) | |

| FATE133 | 3 | 5 | - | - | - | 3.1% (32)- [AF] | BAV (Holter) | |

| FATE136 | 4 | 1 | 46.8 | 59.0 | 35.1 | 4.3% (23)- [AF] | 0.0% (12)- [SR] | |

| FATE143 | 5 | 1 | - | 26.0 | 33.5 | 3.3% (30)- [AF] | 0.0% (17)- [APC] | |

| FATE146 | 4 | 4 | 27.2 | 47.0 | 39.7 | 15.6% (32)- [AF] | AF (follow-up ECG) | |

| All average | 3.9±1.04 | 3.3±1.4 | 28.5±9.0 | 51.6±12.6 | 30.3±9.0 | |||

| AF average | 3.±0.8 | 4.2±1.1 | 17.2±8.7 | 38.6±15.3 | 38.6±9.3 | 31.7±11.5 | ||

| no-AF average | 3.9±1.0 | 3.2±1.4 | 28.4±9.1 | 52.6±11.9 | 29.6±8.7 | 43.7±44.2 | ||

| P-value | 0.666 | 0.017 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.022 | ||

| 1: Risk stratification for atrial fibrillation should be performed using validated risk scores. Efficient identification of high-risk individuals relies on the routine application of these scores. Additionally, incorporating alerts into clinical records can enhance awareness and facilitate timely intervention. |

| 2: The systematic measurement of the MVP score should be included in the risk assessment and documented alongside the CHA2DS2-VA score. Incomplete recording of risk factors and clinical findings in primary care health records can impede the continuity and quality of care. |

| 3: Data integration records should be assessed to determine the need for external monitoring, particularly in conjunction with echocardiography findings, such as left atrial ejection fraction (LA-EF) and left atrial strain (LA-Sr). However, limited resources in primary care, including restricted access to echocardiography and external monitoring, pose significant challenges for effective AF screening and follow-up monitoring. |

| 4: In cases of a positive result from external monitoring, an atrial fibrillation diagnosis should be confirmed through Holter monitoring, which should be accessible within primary care services. This approach leads to benefits such as empowering users and providers through advanced monitoring, less referral burden, decrease in wait lists, and lower healthcare costs. |

| 5: If atrial fibrillation is confirmed, oral anticoagulation and rhythm control should be initiated in accordance with ESC guidelines. For negative results, a follow-up protocol for external monitoring should be established to ensure ongoing evaluation. |

| 6: The availability of quality indicators and cost-effectiveness assessments is essential for evaluating and optimizing the healthcare process. These metrics provide valuable insights into the efficiency, effectiveness, and overall impact of interventions, enabling data-driven improvements in patient care. |

| For future research, it is important to emphasize that when atrial fibrillation (AF) (including DDAF and SCAF) is detected via an external device, two additional variables should be assessed to determine whether to initiate oral anticoagulation (OAC): 1/ AF burden, in conjunction with other relevant variables, and 2/ Thrombotic risk and bleeding risk assessment using artificial intelligence tools that incorporate all of the aforementioned variables independently of the AF diagnosis. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).