Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

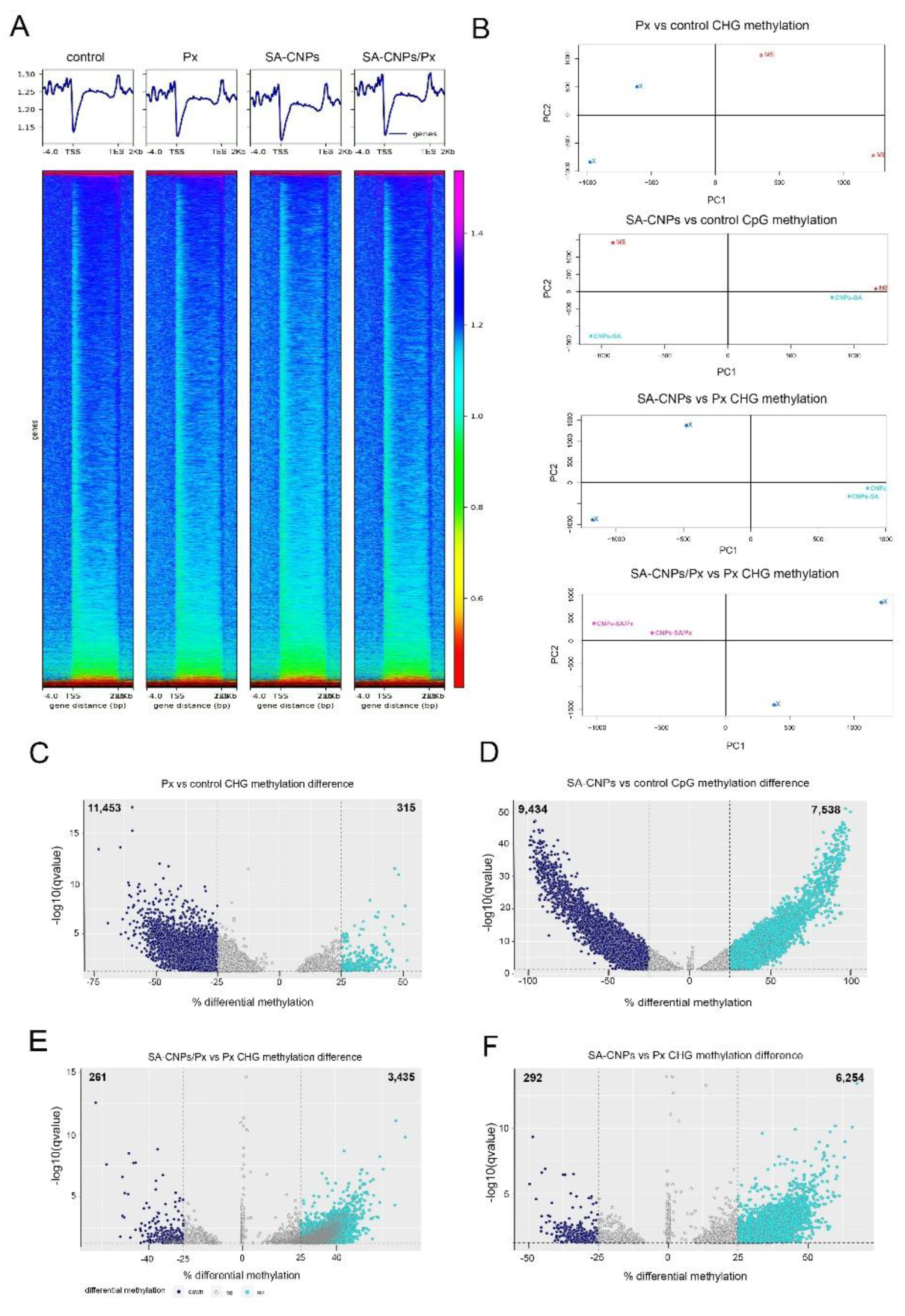

2.1. SA-CNPs Formulation Alters Specific Methylation Contexts in Arabidopsis with and Without Pathogen Inoculation

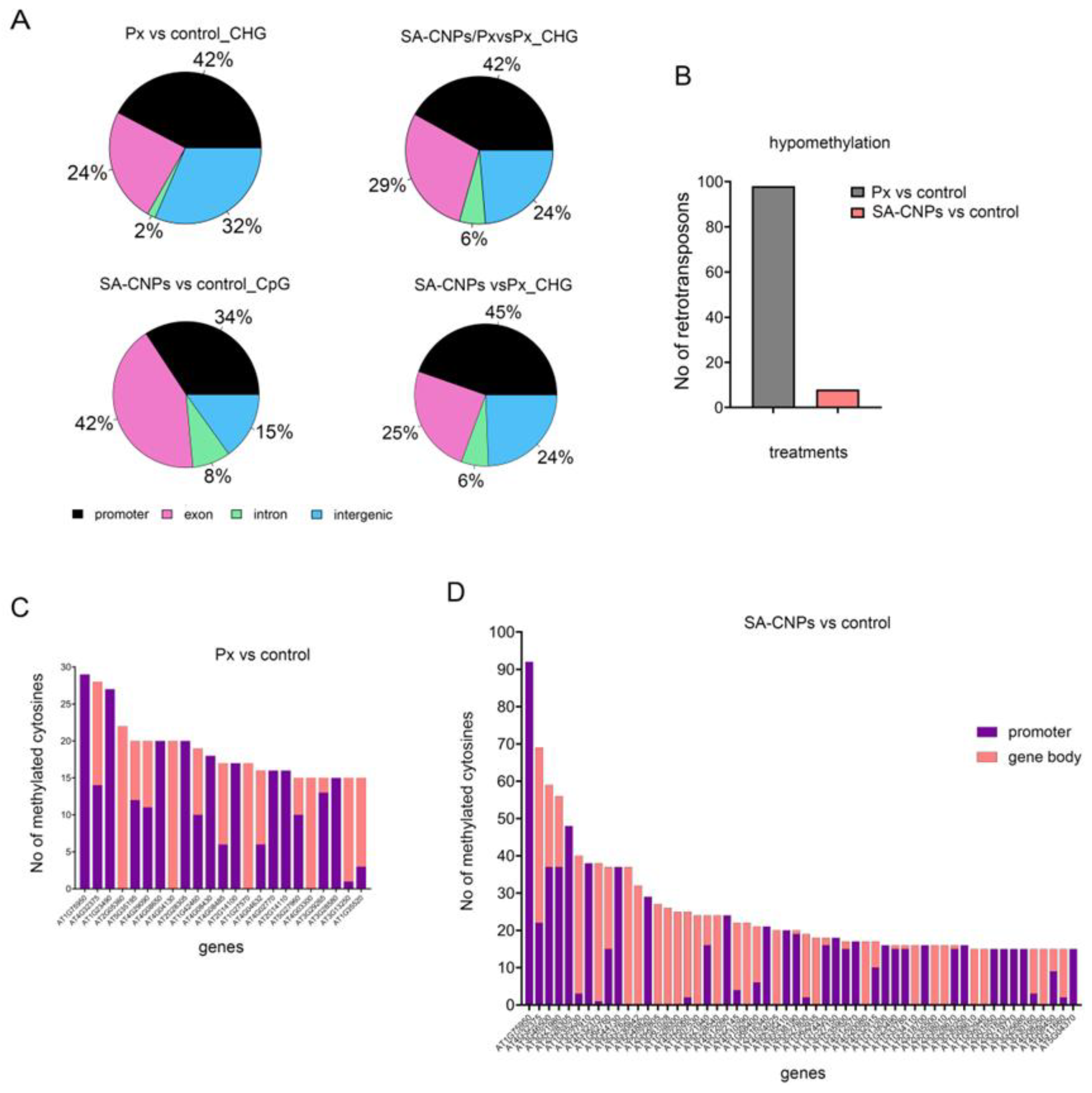

2.2. Distinct Genomic Regions Have Altered Methylation Imprint After SA-CNPs or P. xanthii

2.3. SA-CNPs Increase Hypomethylation of Defense-Related Genes Compared to P. xanthii

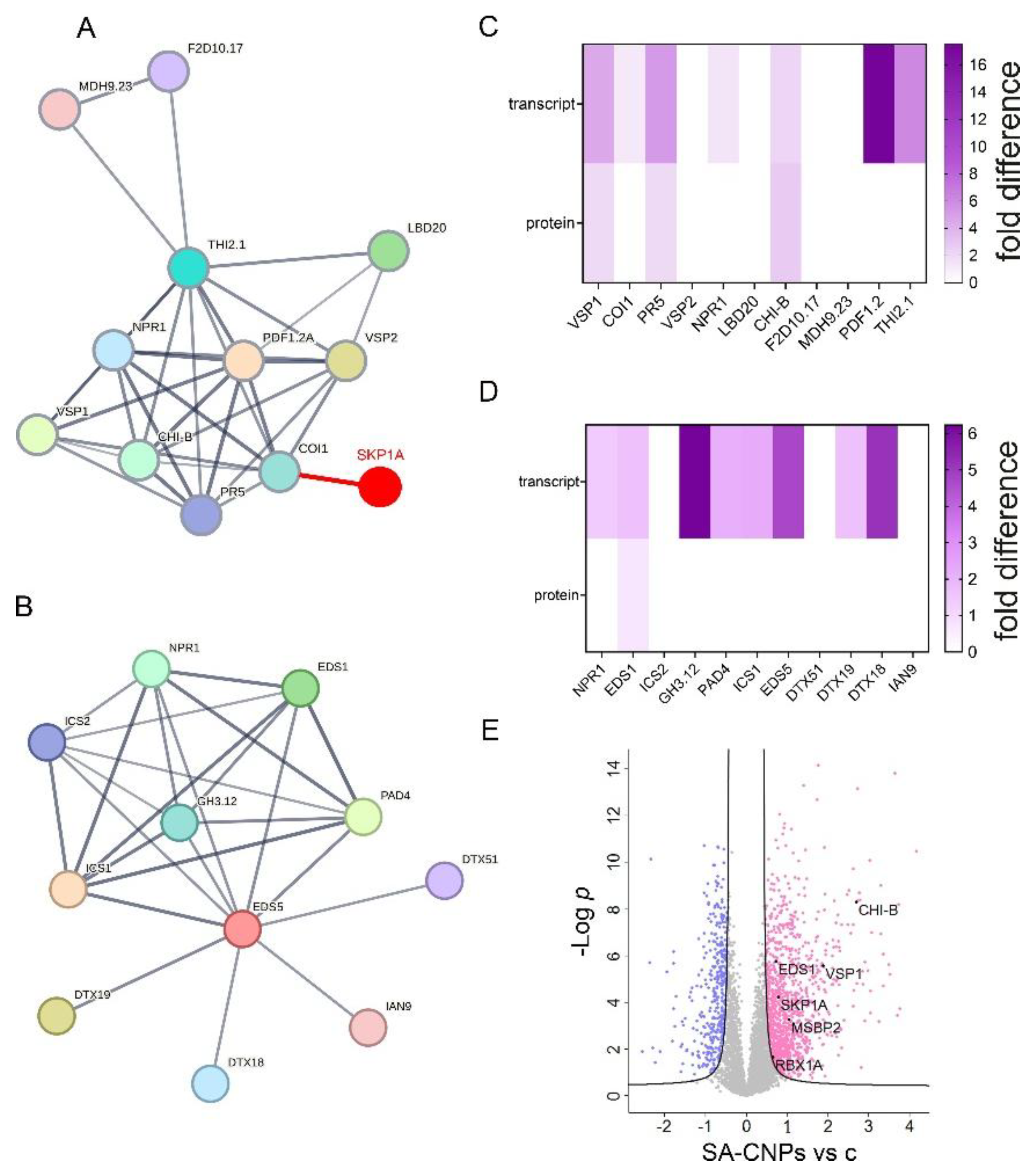

2.4. Hypomethylated DMR that is Associated with SKP1A Contains Defense-Related Cis-Elements

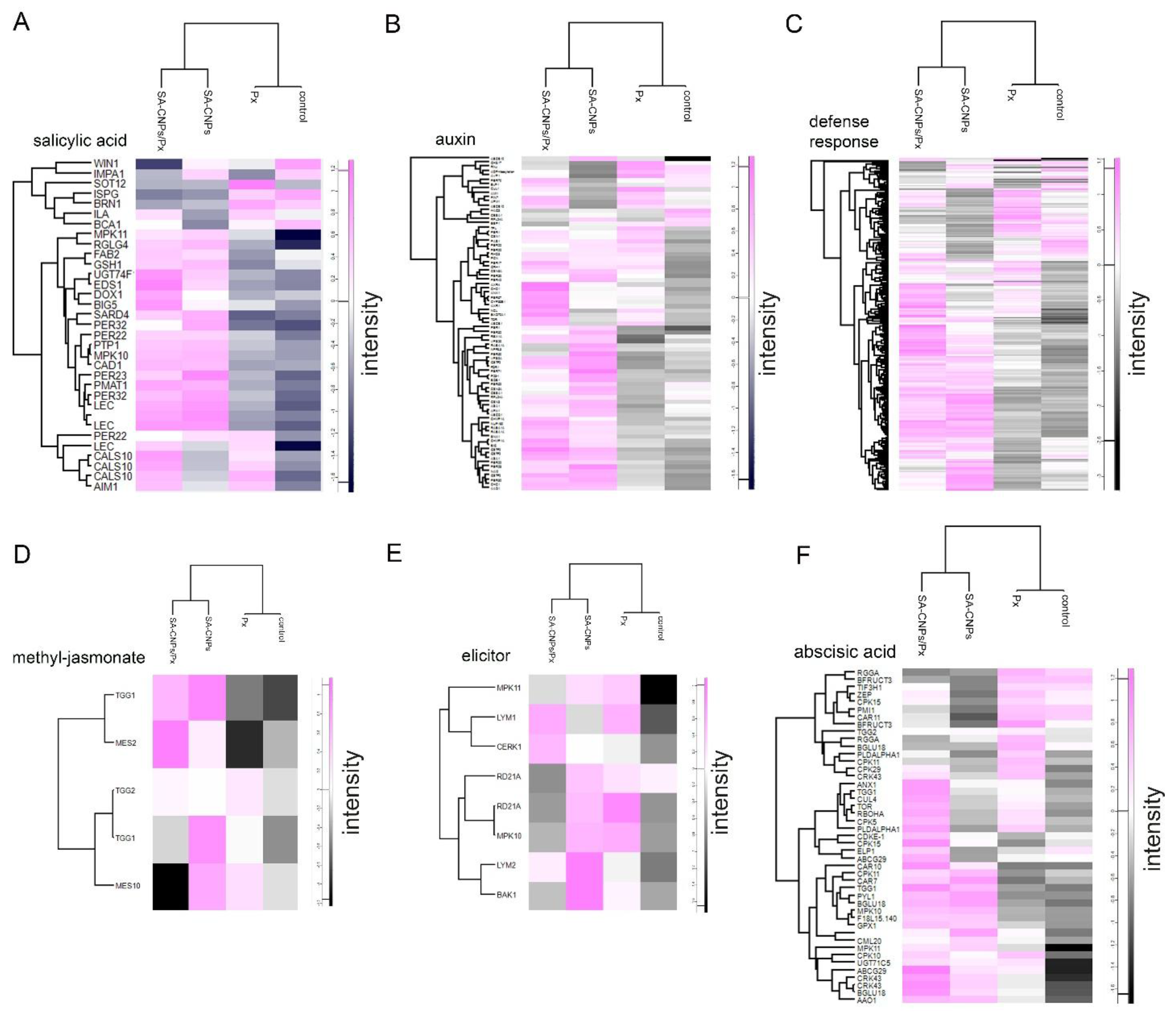

2.5. Up-Regulation of Proteins Involved with Defense-Related Cis-Elements

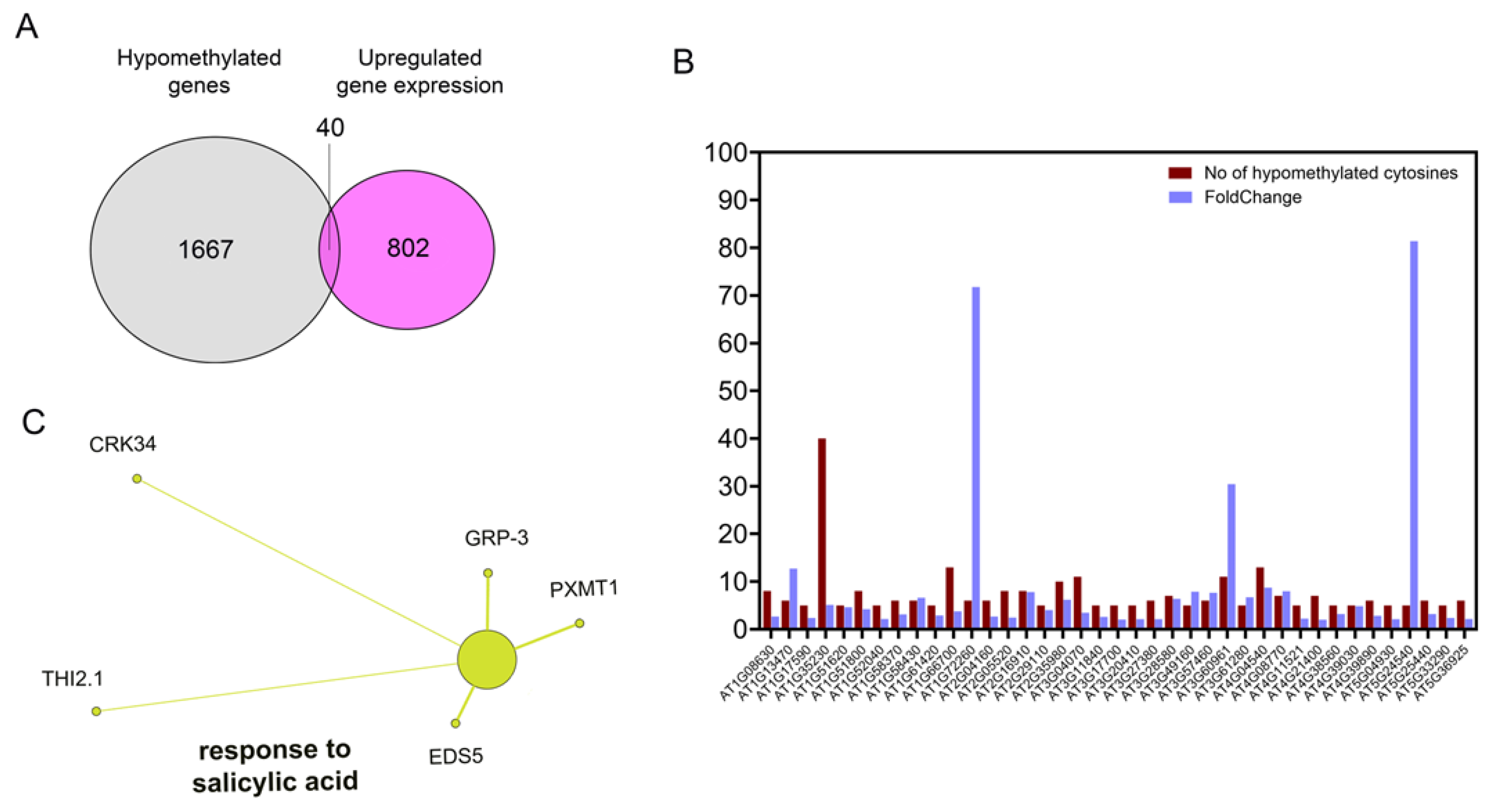

2.6. Hypomethylation After SA-CNPs Application Is Associated with SA-Related Up-Regulated Gene Expression

3. Discussion

3.1. The Arabidopsis Methylome Marks Respond to Treatments

3.2. Treatments Generate Specific Modifications of Methylation Marks on Arabidopsis Genomic Regions

3.3. SA-CNPs Application Enhances Hypomethylation in Defense-Related Cis Elements Associated with Ubiquitination and Cell Wall Modification Genes

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

4.2. Chitosan Nanoparticles Application

4.3. Pathogen Challenge Accompanied by Hormone Treatment

4.4. BS-Seq Library Construction and Genome Bisulfite Sequencing

4.5. Processing of Bisulfite-Treated Reads and Methylation Calling

4.6. Differential Methylation Analysis

4.7. Protein Differential Expression

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiao, S.; Song, W.; Hu, W.; Wang, F.; Liao, A.; Tan, W.; Yang, S. The role of plant DNA methylation in development, stress response, and crop breeding. Agronomy 2024, 15((1)), 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.-J.; Chen, T.; Zhu, J.-K. Regulation and function of DNA methylation in plants and animals. Cell research 2011, 21((3)), 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, R.; Pelizzola, M.; Dowen, R. H.; Hawkins, R. D.; Hon, G.; Tonti-Filippini, J.; Nery, J. R.; Lee, L.; Ye, Z.; Ngo, Q.-M. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. nature 2009, 462((7271)), 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yazaki, J.; Sundaresan, A.; Cokus, S.; Chan, S. W.-L.; Chen, H.; Henderson, I. R.; Shinn, P.; Pellegrini, M.; Jacobsen, S. E. Genome-wide high-resolution mapping and functional analysis of DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Cell 2006, 126((6)), 1189–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucibelli, F.; Valoroso, M. C.; Aceto, S. Plant DNA methylation: an epigenetic mark in development, environmental interactions, and evolution. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23((15)), 8299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnusamy, V.; Zhu, J.-K. RNA-directed DNA methylation and demethylation in plants. Science in China Series C: Life Sciences 2009, 52((4)), 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kumar, S.; Qian, W. Active DNA demethylation: mechanism and role in plant development. Plant cell reports 2018, 37((1)), 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, T.-F.; Ibarra, C. A.; Silva, P.; Zemach, A.; Eshed-Williams, L.; Fischer, R. L.; Zilberman, D. Genome-wide demethylation of Arabidopsis endosperm. Science 2009, 324((5933)), 1451–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedeva, Y. A.; Khamis, A. M.; Kulakovskiy, I. V.; Ba-Alawi, W.; Bhuyan, M. S. I.; Kawaji, H.; Lassmann, T.; Harbers, M.; Forrest, A. R.; Bajic, V. B. Effects of cytosine methylation on transcription factor binding sites. BMC genomics 2014, 15((1)), 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ren, B. Role of H3K4 monomethylation in gene regulation. Current opinion in genetics & development 2024, 84, 102153. [Google Scholar]

- Saijo, Y.; Loo, E. P. i.; Yasuda, S. Pattern recognition receptors and signaling in plant–microbe interactions. The Plant Journal 2018, 93((4)), 592–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiade, S. R. G.; Zand-Silakhoor, A.; Fathi, A.; Rahimi, R.; Minkina, T.; Rajput, V. D.; Zulfiqar, U.; Chaudhary, T. Plant metabolites and signaling pathways in response to biotic and abiotic stresses: Exploring bio stimulant applications. Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Ngou, B. P. M.; Ding, P.; Xin, X.-F. PTI-ETI crosstalk: an integrative view of plant immunity. Current opinion in plant biology 2021, 62, 102030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Medina, A.; Flors, V.; Heil, M.; Mauch-Mani, B.; Pieterse, C. M.; Pozo, M. J.; Ton, J.; van Dam, N. M.; Conrath, U. Recognizing plant defense priming. Trends in plant science 2016, 21((10)), 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauch-Mani, B.; Baccelli, I.; Luna, E.; Flors, V. Defense priming: an adaptive part of induced resistance. Annual review of plant biology 2017, 68, 485–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrath, U.; Beckers, G. J.; Flors, V.; García-Agustín, P.; Jakab, G.; Mauch, F.; Newman, M.-A.; Pieterse, C. M.; Poinssot, B.; Pozo, M. J. Priming: getting ready for battle. Molecular plant-microbe interactions 2006, 19((10)), 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrath, U.; Beckers, G. J.; Langenbach, C. J.; Jaskiewicz, M. R. Priming for enhanced defense. Annual review of phytopathology 2015, 53((1)), 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannan Parker, A.; Wilkinson, S. W.; Ton, J. Epigenetics: a catalyst of plant immunity against pathogens. New Phytologist 2022, 233((1)), 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hönig, M.; Roeber, V. M.; Schmülling, T.; Cortleven, A. Chemical priming of plant defense responses to pathogen attacks. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1146577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Sánchez, A.; Stassen, J. H.; Furci, L.; Smith, L. M.; Ton, J. The role of DNA (de) methylation in immune responsiveness of Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 2016, 88((3)), 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Lepère, G.; Jay, F.; Wang, J.; Bapaume, L.; Wang, Y.; Abraham, A.-L.; Penterman, J.; Fischer, R. L.; Voinnet, O. Dynamics and biological relevance of DNA demethylation in Arabidopsis antibacterial defense. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110((6)), 2389–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A.; Ramírez, V.; García-Andrade, J.; Flors, V.; Vera, P. The RNA silencing enzyme RNA polymerase V is required for plant immunity. PLoS genetics 2011, 7((12)), e1002434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiselev, K.; Tyunin, A.; Karetin, Y. Salicylic acid induces alterations in the methylation pattern of the VaSTS1, VaSTS2, and VaSTS10 genes in Vitis amurensis Rupr. cell cultures. Plant cell reports 2015, 34((2)), 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Wang, X.; Wei, T.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Hua, L.; Ren, X.; Guo, J.; Li, J. Exogenous salicylic acid regulates cell wall polysaccharides synthesis and pectin methylation to reduce Cd accumulation of tomato. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety 2021, 207, 111550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaritopoulou, T.; Kotsaridis, K.; Samiotaki, M.; Nastos, S.; Maratos, M.; Zoidakis, I.; Tsiriva, D.; Pispas, S.; Markellou, E. Antagonistic manipulation of ER-protein quality control between biotrophic pathogenic fungi and host induced defense. Plant Stress 2024, 14, 100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, F.; Ryan, D. P.; Grüning, B.; Bhardwaj, V.; Kilpert, F.; Richter, A. S.; Heyne, S.; Dündar, F.; Manke, T. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic acids research Web Server issue. 2016, 44, W160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, J.; Park, J.; Hong, C. P.; Choi, D.; Han, S.; Choi, K.; Roh, T.-Y.; Hwang, D.; Hwang, I. DDM1-mediated gene body DNA methylation is associated with inducible activation of defense-related genes in Arabidopsis. Genome biology 2023, 24((1)), 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowen, R. H.; Pelizzola, M.; Schmitz, R. J.; Lister, R.; Dowen, J. M.; Nery, J. R.; Dixon, J. E.; Ecker, J. R. Widespread dynamic DNA methylation in response to biotic stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109((32)), E2183–E2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Lang, Z.; Zhu, J.-K. Dynamics and function of DNA methylation in plants. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2018, 19((8)), 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavet, V.; Quintero, C.; Cecchini, N. M.; Rosa, A. L.; Alvarez, M. E. Arabidopsis displays centromeric DNA hypomethylation and cytological alterations of heterochromatin upon attack by Pseudomonas syringae. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2006, 19((6)), 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.-N.; Schumann, U.; Smith, N. A.; Tiwari, S.; Au, P. C. K.; Zhu, Q.-H.; Taylor, J. M.; Kazan, K.; Llewellyn, D. J.; Zhang, R. DNA demethylases target promoter transposable elements to positively regulate stress responsive genes in Arabidopsis. Genome biology 2014, 15((9)), 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, A. R.; da Costa Silva, D.; dos Santos Pinto, K. N.; Santos Filho, H. P.; Coelho Filho, M. A.; dos Santos Soares Filho, W.; Ferreira, C. F.; da Silva Gesteira, A. Epigenetic responses to Phytophthora citrophthora gummosis in citrus. Plant Science 2021, 313, 111082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Kong, X.; Song, G.; Jia, M.; Guan, J.; Wang, F.; Qin, Z.; Wu, L.; Lan, X.; Li, A. DNA methylation dynamics during the interaction of wheat progenitor Aegilops tauschii with the obligate biotrophic fungus Blumeria graminis f. sp. tritici. New Phytologist 2019, 221((2)), 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, K.; Katakami, H.; Kim, H.-J.; Ogawa, E.; Sano, C. M.; Wada, Y.; Sano, H. Epigenetic inheritance in rice plants. Annals of botany 2007, 100((2)), 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Aguilar, K.; Ramírez-Carrasco, G.; Hernández-Chávez, J. L.; Barraza, A.; Alvarez-Venegas, R. Use of BABA and INA as activators of a primed state in the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 7, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerli, L.; Métraux, J.-P.; Mauch-Mani, B. β-Aminobutyric acid-induced protection of Arabidopsis against the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiology 2001, 126((2)), 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerli, L.; Jakab, G.; Métraux, J.-P.; Mauch-Mani, B. Potentiation of pathogen-specific defense mechanisms in Arabidopsis by β-aminobutyric acid. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 2000, 97((23)), 12920–12925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Chi, Y.; Li, R.; Mo, L.; Shi, L.; Liang, S.; Yu, W. Recent progress of molecular mechanisms of DNA methylation in plant response to abiotic stress. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2024, 218, 105599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Ding, A. B.; Liu, F.; Zhong, X. Linking signaling pathways to histone acetylation dynamics in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 2020, 71((17)), 5179–5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mohapatra, T. Dynamics of DNA methylation and its functions in plant growth and development. Frontiers in plant science 2021, 12, 596236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Xu, Z. Y. Dynamic regulation of DNA methylation and histone modifications in response to abiotic stresses in plants. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2022, 64((12)), 2252–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Yoshida, H. Refunctionalization of the ancient rice blast disease resistance gene Pit by the recruitment of a retrotransposon as a promoter. The Plant Journal 2009, 57((3)), 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atighi, M. R.; Verstraeten, B.; De Meyer, T.; Kyndt, T. Genome-wide DNA hypomethylation shapes nematode pattern-triggered immunity in plants. New Phytologist 2020, 227((2)), 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonnessen, B. W.; Bossa-Castro, A. M.; Martin, F.; Leach, J. E. Intergenic spaces: a new frontier to improving plant health. New Phytologist 2021, 232((4)), 1540–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, M.; Feng, F.; Gallavotti, A. Mapping regulatory determinants in plants. Frontiers in Genetics 2020, 11, 591194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishina, T. E.; Zeier, J. Pathogen-associated molecular pattern recognition rather than development of tissue necrosis contributes to bacterial induction of systemic acquired resistance in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 2007, 50((3)), 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplan, V.; Rivas, S. E3 ubiquitin-ligases and their target proteins during the regulation of plant innate immunity. Frontiers in plant science 2014, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, D.; Peeters, N.; Rivas, S. Ubiquitination during plant immune signaling. Plant physiology 2012, 160((1)), 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Schiff, M.; Serino, G.; Deng, X.-W.; Dinesh-Kumar, S. Role of SCF ubiquitin-ligase and the COP9 signalosome in the N gene–mediated resistance response to Tobacco mosaic virus. The Plant Cell 2002, 14((7)), 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathoti, N. K.; Saengchan, C.; Daddam, J. R.; Thongprom, N.; Tonpho, K.; Thanh, T. L.; Buensanteai, N. Plant systemic acquired resistance compound salicylic acid as a potent inhibitor against SCF (SKP1-CUL1-F-box protein) mediated complex in Fusarium oxysporum by homology modeling and molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 2022, 40((4)), 1472–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomma, B. P.; Eggermont, K.; Penninckx, I. A.; Mauch-Mani, B.; Vogelsang, R.; Cammue, B. P.; Broekaert, W. F. Separate jasmonate-dependent and salicylate-dependent defense-response pathways in Arabidopsis are essential for resistance to distinct microbial pathogens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95((25)), 15107–15111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorente, F.; Muskett, P.; Sanchez-Vallet, A.; López, G.; Ramos, B.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, C.; Jorda, L.; Parker, J.; Molina, A. Repression of the auxin response pathway increases Arabidopsis susceptibility to necrotrophic fungi. Molecular plant 2008, 1((3)), 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.-M.; Zhu, S.; Kachroo, P.; Kachroo, A. Signal regulators of systemic acquired resistance. Frontiers in plant science 2015, 6, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehra, A.; Meena, M.; Dubey, M. K.; Aamir, M.; Upadhyay, R. Synergistic effects of plant defense elicitors and Trichoderma harzianum on enhanced induction of antioxidant defense system in tomato against Fusarium wilt disease. Botanical Studies 2017, 58((1)), 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngom, B.; Sarr, I.; Kimatu, J.; Mamati, E.; Kane, N. A. Genome-wide analysis of cytosine DNA methylation revealed salicylic acid promotes defense pathways over seedling development in pearl millet. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2017, 12((9)), e1356967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngom, B.; Mamati, E.; Goudiaby, M. F.; Kimatu, J.; Sarr, I.; Diouf, D.; Kane, N. A. Methylation analysis revealed salicylic acid affects pearl millet defense through external cytosine DNA demethylation. Journal of Plant Interactions 2018, 13((1)), 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosher, R. A.; Durrant, W. E.; Wang, D.; Song, J.; Dong, X. A comprehensive structure–function analysis of Arabidopsis SNI1 defines essential regions and transcriptional repressor activity. The Plant Cell 2006, 18((7)), 1750–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Burg, H. A.; Takken, F. L. Does chromatin remodeling mark systemic acquired resistance? Trends in Plant Science 2009, 14((5)), 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Yao, R.; Deng, H.; Xie, Q.; Xie, D. The Arabidopsis F-box protein CORONATINE INSENSITIVE1 is stabilized by SCFCOI1 and degraded via the 26S proteasome pathway. The Plant Cell 2013, 25((2)), 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Does, D.; Leon-Reyes, A.; Koornneef, A.; Van Verk, M. C.; Rodenburg, N.; Pauwels, L.; Goossens, A.; Körbes, A. P.; Memelink, J.; Ritsema, T. Salicylic acid suppresses jasmonic acid signaling downstream of SCFCOI1-JAZ by targeting GCC promoter motifs via transcription factor ORA59. The Plant Cell 2013, 25((2)), 744–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziller, M. J.; Hansen, K. D.; Meissner, A.; Aryee, M. J. Coverage recommendations for methylation analysis by whole-genome bisulfite sequencing. Nature methods 2015, 12((3)), 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A. M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30((15)), 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature methods 2012, 9((4)), 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, F.; Andrews, S. R. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. bioinformatics 2011, 27((11)), 1571–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinlan, A. R.; Hall, I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010, 26((6)), 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akalin, A.; Kormaksson, M.; Li, S.; Garrett-Bakelman, F. E.; Figueroa, M. E.; Melnick, A.; Mason, C. E. methylKit: a comprehensive R package for the analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles. Genome biology 2012, 13((10)), R87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Sinitcyn, P.; Carlson, A.; Hein, M. Y.; Geiger, T.; Mann, M.; Cox, J. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote) omics data. Nature methods 2016, 13((9)), 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).