Submitted:

13 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. Challenges of Disease Surveillance in Horticulture

3.2. Potential of High-Throughput Sequencing and Environmental DNA for Plant Pathogen Surveillance

3.3. Optimizing Sampling Matrices for Contrasting Phytopathogenic Groups

3.3.1. Phytopathogen Life Cycle and eDNA Detection

Oomycetes

Phytophthora

Pythium

Downy Mildews

Viruses

Fungi

Bacteria

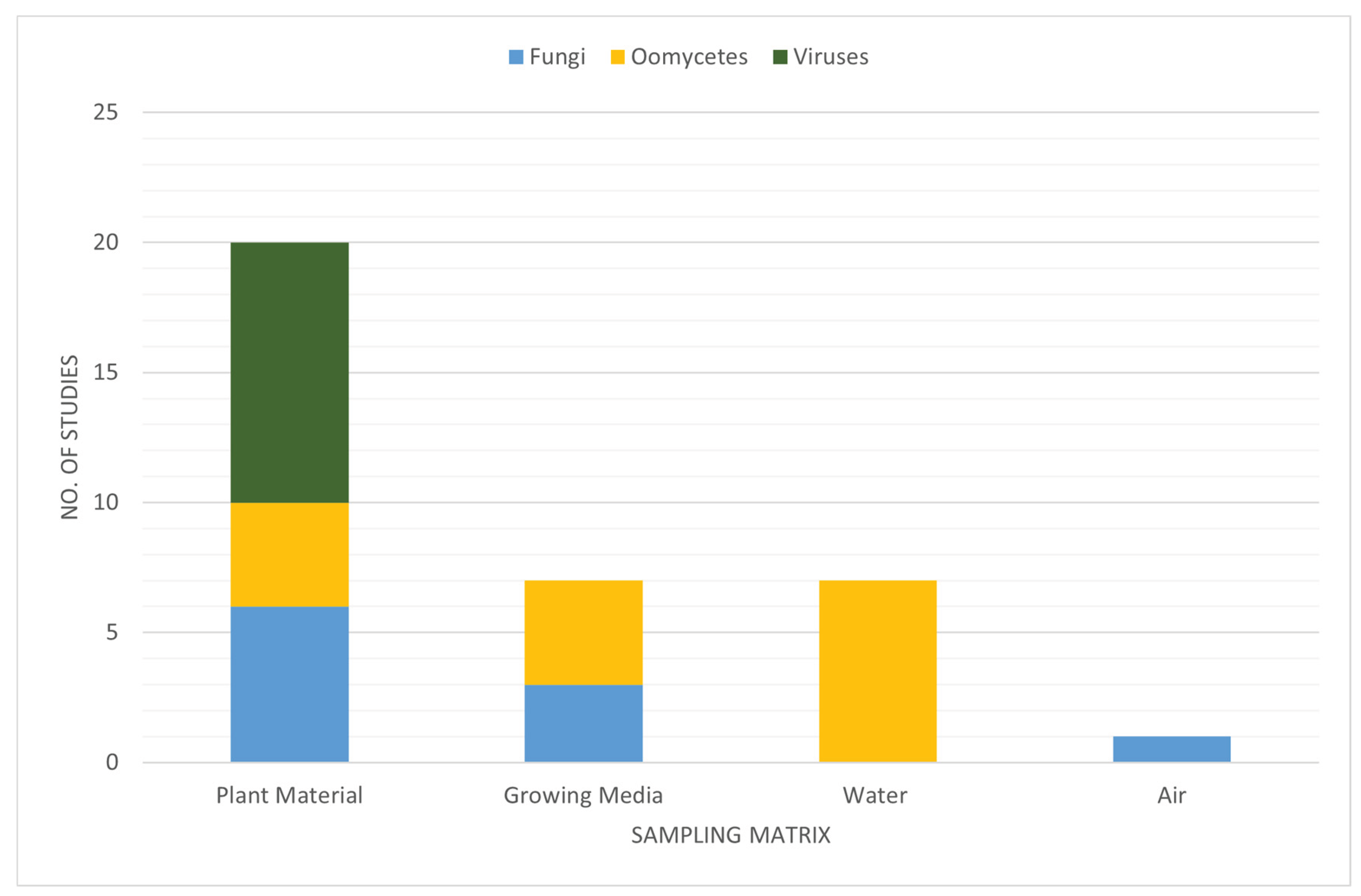

3.3.2. eDNA Sample Matrices and Methods

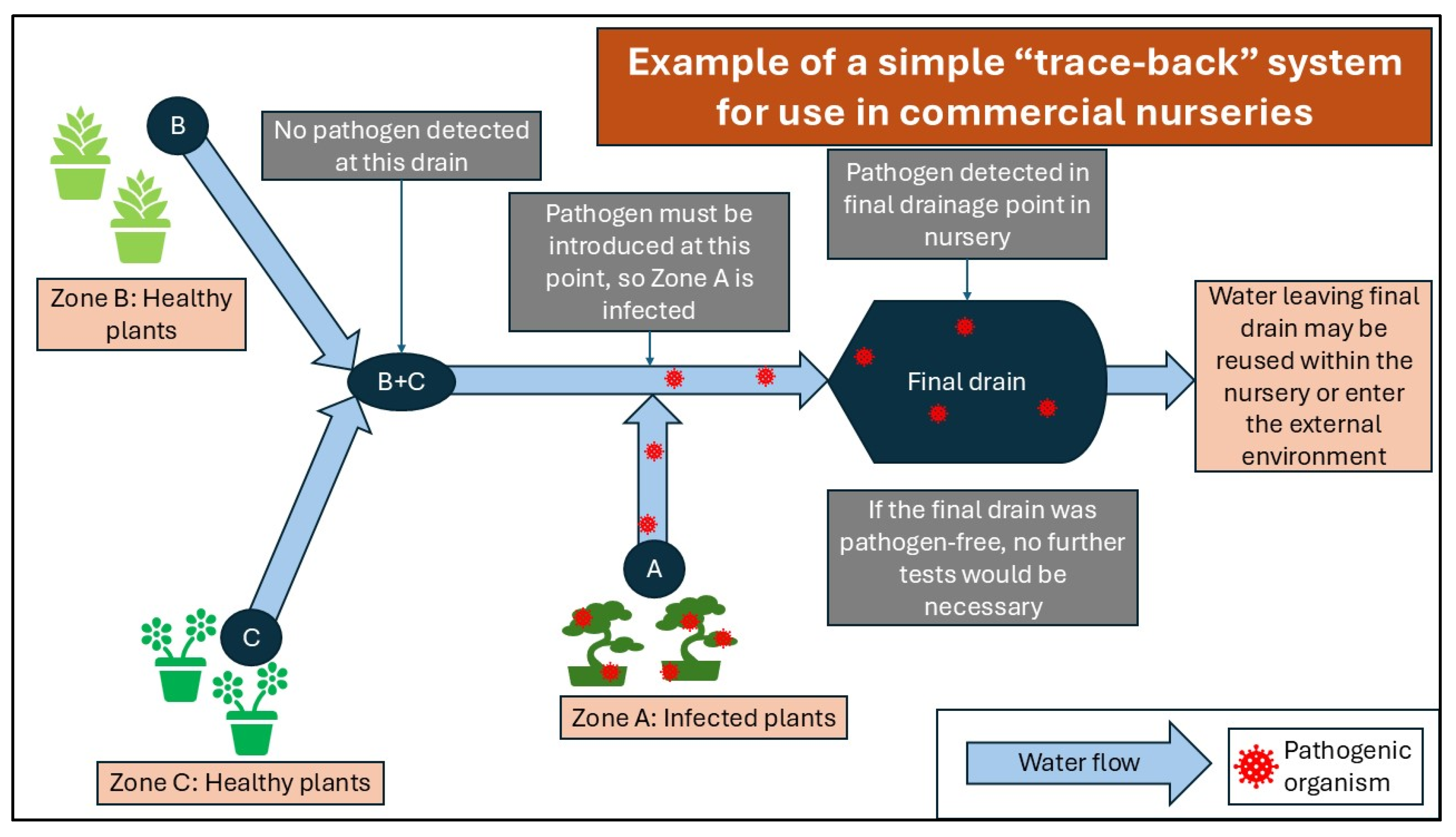

Water Sampling

Growing Media Sampling

Air Sampling

Plant Material Sampling

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| HTS | High-throughput sequencing |

| eDNA | Environmental DNA |

| EPPO | European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

References

- United Nations; Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results; Stylus Publishing, LLC, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, L.; Green, S.; MacKay, J. Pathogen impacts and implications for species diversification in UK forestry. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research 2025, cpaf019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Egidi, E.; Guirado, E.; Leach, J.E.; Liu, H.; Trivedi, P. Climate change impacts on plant pathogens, food security and paths forward. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023, 21, 640–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Market Estimates. Horticulture Market Report. Available online: https://www.globalmarketestimates.com/market-report/horticulture-market-3414 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- The Business Research Company, Nursery and Floriculture Global Market Report. Available online: https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/report/nursery-and-floriculture-production-global-market-report (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Hinsley, A.; Hughes, A.C.; van Valkenburg, J.; Stark, T.; van Delft, J.; Sutherland, W.; Petrovan, S.O. Understanding the environmental and social risks from the international trade in ornamental plants. BioScience 2025, 75, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.; Cooke, D.E.; Dunn, M.; Barwell, L.; Purse, B.; Chapman, D.S.; Valatin, G.; Schlenzig, A.; Barbrook, J.; Pettitt, T. PHYTO-THREATS: Addressing threats to UK forests and woodlands from Phytophthora; identifying risks of spread in trade and methods for mitigation. Forests 2021, 12, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasier, C. The biosecurity threat to the UK and global environment from international trade in plants. Plant Pathology 2008, 57, 792–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodoni, B. The role of plant biosecurity in preventing and controlling emerging plant virus disease epidemics. Virus research 2009, 141, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colunga-Garcia, M.; Haack, R.; Magarey, R.; Borchert, D. Understanding trade pathways to target biosecurity surveillance. NeoBiota 2013, 18, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, C.R.; Marzano, M. On a handshake: business-to-business trust in the biosecurity behaviours of the UK live plant trade. Biological Invasions 2023, 25, 2531–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, A.; Donovan, N.; Mantri, N. The future of plant pathogen diagnostics in a nursery production system. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2019, 145, 111631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullino, M.; Bertetti, D.; Garibaldi, A. Fungal and bacterial diseases on ornamental trees, shrubs, hedges and climbing plants detected in the last 20 years in northern Italy. In Proceedings of the IV International Symposium on Woody Ornamentals of the Temperate Zone 1331, 2021; pp. 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Smoktunowicz, M.; Jonca, J.; Stachowska, A.; May, M.; Waleron, M.M.; Waleron, M.; Waleron, K. The international trade of ware vegetables and ornamental plants—An underestimated risk of accelerated spreading of phytopathogenic bacteria in the era of globalisation and ongoing climatic changes. Pathogens 2022, 11, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valatin, G.; Price, C.; Green, S. Reducing disease risks to British forests: An exploration of costs and benefits of nursery best practices. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research 2022, 95, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, L.; Jones, G.; Atkinson, N.; Hector, A.; Hemery, G.; Brown, N. The £15 billion cost of ash dieback in Britain. Current Biology 2019, 29, R315–R316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, J.L.; Grünwald, N.J. A systems approach for management of pests and pathogens of nursery crops. Plant Disease 2012, 96, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart-Wade, S.M. Plant pathogens in recycled irrigation water in commercial plant nurseries and greenhouses: their detection and management. Irrigation Science 2011, 29, 267–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavent-Celma, C.; McLaggan, D.; van West, P.; Woodward, S. Evidence of a Natural Hybrid Oomycete Isolated from Ornamental Nursery Stock. Journal of Fungi 2023, 9, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPPO Standard on Diagnostics. PM 7/151 (1) Considerations for the use of high throughput sequencing in plant health diagnostics. EPPO Bulletin 2022, 52, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPPO Standard on Diagnostics. PM 7/98 (5). Specific requirements for laboratories preparing accreditation for a plant pest diagnostic activity; EPPO Bull. 2021; 51, pp. 468–498.

- Green, S.; Cooke, D.E.; Barwell, L.; Purse, B.V.; Cock, P.; Frederickson-Matika, D.; Randall, E.; Keillor, B.; Pritchard, L.; Thorpe, P. The prevalence of Phytophthora in British plant nurseries; high-risk hosts and substrates and opportunities to implement best practice. Plant Pathology 2025, 74, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, C.; Biscontri, M.; Tabet, D.; Vettraino, A.M. The never-ending presence of Phytophthora species in Italian nurseries. Pathogens 2022, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bačová, A.; Cooke, D.E.; Milenković, I.; Májek, T.; Nagy, Z.Á.; Corcobado, T.; Randall, E.; Keillor, B.; Cock, P.J.; Jung, M.H. Hidden Phytophthora diversity unveiled in tree nurseries of the Czech Republic with traditional and metabarcoding techniques. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2024, 170, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braley, L.E.; Jewell, J.B.; Figueroa, J.; Humann, J.L.; Main, D.; Mora-Romero, G.A.; Moroz, N.; Woodhall, J.W.; White, R.A., III; Tanaka, K. Nanopore sequencing with GraphMap for comprehensive pathogen detection in potato field soil. Plant Disease 2023, 107, 2288–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, C.; Blouin, A.G.; Tindale, S.; Steyer, S.; Marechal, K.; Massart, S. High Throughput Sequencing technologies complemented by grower’s perception highlight the impact of tomato virome in diversified vegetable farms 2023.2001. 2012.523758. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Villamor, D.; Keller, K.; Martin, R.; Tzanetakis, I. Comparison of high throughput sequencing to standard protocols for virus detection in berry crops. Plant Disease 2022, 106, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, J.E.; Frey, B.; Frei, D.; Blaser, S.; Gueuning, M.; Bühlmann, A. Next generation biosecurity: Towards genome based identification to prevent spread of agronomic pests and pathogens using nanopore sequencing. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0270897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguayo, J.; Husson, C.; Chancerel, E.; Fabreguettes, O.; Chandelier, A.; Fourrier-Jeandel, C.; Dupuy, N.; Dutech, C.; Ioos, R.; Robin, C.; et al. Combining permanent aerobiological networks and molecular analyses for large-scale surveillance of forest fungal pathogens: A proof-of-concept. Plant Pathology 2021, 70, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kaeath, N.; Zagier, S.; Alisawi, O.; Fadhal, F.A.; Mahfoudhi, N. High-Throughput Sequencing Identified Multiple Fig Viruses and Viroids Associated with Fig Mosaic Disease in Iraq. Plant Pathol J 2024, 40, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Lara, A.; Stevens, K.; Aguilar-Molina, V.H.; Fernández-Cortés, J.M.; Chabacano León, V.M.; De Donato, M.; Sharma, A.; Erickson, T.M.; Al Rwahnih, M. High-Throughput Sequencing of Grapevine in Mexico Reveals a High Incidence of Viruses including a New Member of the Genus Enamovirus. Viruses 2023, 15, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishan, G.; Sharma, S.; Holkar, S.; Gupta, N.; Khan, Z.; Singh, S.; Baranwal, V. Diverse spectra of virus infection identified through high throughput sequencing in nursery plants of two Indian grapevine cultivars. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Issues Brief: Environmental DNA. Available online: https://iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/environmental-dna (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Kageyama, S.A.; Hoogland, M.R.; Tajjioui, T.; Schreier, T.M.; Erickson, R.A.; Merkes, C.M. Validation of a Portable eDNA Detection Kit for Invasive Carps. Fishes 2022, 7, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeter, B.; Veríssimo, J.; Lopes-Lima, M.; Chaves, C.; Pinto, J.; Riccardi, N.; Beja, P.; Fonseca, N.A. Speeding up the detection of invasive bivalve species using environmental DNA: A Nanopore and Illumina sequencing comparison. Mol Ecol Resour 2022, 22, 2232–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaggio, A.J.; Gierus, L.; Taylor, D.R.; Holmes, N.D.; Will, D.J.; Gemmell, N.J.; Thomas, P.Q. Building an eDNA surveillance toolkit for invasive rodents on islands: can we detect wild-type and gene drive Mus musculus? BMC Biol 2024, 22, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batovska, J.; Brohier, N.D.; Mee, P.T.; Constable, F.E.; Rodoni, B.C.; Lynch, S.E. The Australian Biosecurity Genomic Database: a new resource for high-throughput sequencing analysis based on the National Notifiable Disease List of Terrestrial Animals. Database (Oxford) 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, L.J.; Shaw, J.D.; Suter, L.; Atalah, J.; Bergstrom, D.M.; Biersma, E.; Convey, P.; Greve, M.; Holland, O.; Houghton, M.J. An expert-driven framework for applying eDNA tools to improve biosecurity in the Antarctic. Management of Biological Invasions 2023, 14, 379–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Richardson, P.A.; Kong, P. Comparison of membrane filters as a tool for isolating pythiaceous species from irrigation water. Phytopathology 2002, 92, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, M.A.; Lelwala, R.V.; Elliott, C.E.; Windell, C.; Fiorito, S.; Dinsdale, A.; Whattam, M.; Pattemore, J.; Barrero, R.A. Side-by-Side Comparison of Post-Entry Quarantine and High Throughput Sequencing Methods for Virus and Viroid Diagnosis. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, E.M.; Hooten, M.B.; Baker, F.A. Reconciling multiple data sources to improve accuracy of large-scale prediction of forest disease incidence. Ecol Appl 2011, 21, 1173–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickie, I.A.; Boyer, S.; Buckley, H.L.; Duncan, R.P.; Gardner, P.P.; Hogg, I.D.; Holdaway, R.J.; Lear, G.; Makiola, A.; Morales, S.E.; et al. Towards robust and repeatable sampling methods in eDNA-based studies. Mol Ecol Resour 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granke, L.; Windstam, S.; Hoch, H.; Smart, C.; Hausbeck, M. Dispersal and movement mechanisms of Phytophthora capsici sporangia. Phytopathology 2009, 99, 1258–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.E.; Sands, D.C.; Vinatzer, B.A.; Glaux, C.; Guilbaud, C.; Buffière, A.; Yan, S.; Dominguez, H.; Thompson, B.M. The life history of the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae is linked to the water cycle. Isme j 2008, 2, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, R.; Menkis, A.; Olson, Å. Temporal dynamics of airborne fungi in Swedish forest nurseries. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2025, 91, e01306-01324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redekar, N.R.; Eberhart, J.L.; Parke, J.L. Diversity of Phytophthora, Pythium, and Phytopythium species in recycled irrigation water in a container nursery. Phytobiomes Journal 2019, 3, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marčiulynas, A.; Marčiulynienė, D.; Lynikienė, J.; Gedminas, A.; Vaičiukynė, M.; Menkis, A. Fungi and oomycetes in the irrigation water of forest nurseries. Forests 2020, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoun, S.; Furzer, O.; Jones, J.D.; Judelson, H.S.; Ali, G.S.; Dalio, R.J.; Roy, S.G.; Schena, L.; Zambounis, A.; Panabières, F.; et al. The Top 10 oomycete pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol Plant Pathol 2015, 16, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettitt, T.; Wakeham, A.; Wainwright, M.; White, J. Comparison of serological, culture, and bait methods for detection of Pythium and Phytophthora zoospores in water. Plant Pathology 2002, 51, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossmann, S.; Lysøe, E.; Skogen, M.; Talgø, V.; Brurberg, M.B. DNA metabarcoding reveals broad presence of plant pathogenic oomycetes in soil from internationally traded plants. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 637068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judelson, H.S.; Blanco, F.A. The spores of Phytophthora: weapons of the plant destroyer. Nat Rev Microbiol 2005, 3, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presser, J.W.; Goss, E.M. Environmental sampling reveals that Pythium insidiosum is ubiquitous and genetically diverse in North Central Florida. Med Mycol 2015, 53, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchi, E.; Ametrano, C.G.; Stanković, D.; Verardo, P.; Moretti, O.; Gabrielli, F.; Lazzarin, S.; Borney, M.F.; Tassan, F.; Tretiach, M. DNA metabarcoding uncovers fungal diversity of mixed airborne samples in Italy. PloS one 2018, 13, e0194489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, Z.G.; Burgess, T.I.; Bourret, T.; Bensch, K.; Cacciola, S.O.; Scanu, B.; Mathew, R.; Kasiborski, B.; Srivastava, S.; Kageyama, K.; et al. Phytophthora: taxonomic and phylogenetic revision of the genus. Stud Mycol 2023, 106, 259–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, D.; Ghelardini, L.; Luchi, N.; Capretti, P.; Onorari, M.; Santini, A. Temporal patterns of airborne Phytophthora spp. in a woody plant nursery area detected using real-time PCR. Aerobiologia 2019, 35, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Pérez-Sierra, A.; Durán, A.; Horta Jung, M.; Balci, Y.; Scanu, B. Canker and decline diseases caused by soil- and airborne Phytophthora species in forests and woodlands. Persoonia 2018, 40, 182–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigigallo, M.I.; Abdelfattah, A.; Cacciola, S.O.; Faedda, R.; Sanzani, S.M.; Cooke, D.E.; Schena, L. Metabarcoding analysis of Phytophthora diversity using genus-specific primers and 454 pyrosequencing. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meno, L.; Abuley, I.K.; Escuredo, O.; Seijo, M.C. Factors influencing the airborne sporangia concentration of Phytophthora infestans and its relationship with potato disease severity. Scientia Horticulturae 2023, 307, 111520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunadiya, M.B.; Burgess, T.I.; A Dunstan, W.; White, D.; StJ. Hardy, G.E. Persistence and degradation of Phytophthora cinnamomi DNA and RNA in different soil types. Environmental DNA 2021, 3, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertolas, A.; Bonants, P.J.; Boa, E.; Woodward, S. Application of real-time PCR for the detection and quantification of oomycetes in ornamental nursery stock. Journal of Fungi 2021, 7, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggertson, Q.A.; Rintoul, T.L.; Lévesque, C.A. Resolving the Globisporangium ultimum (Pythium ultimum) species complex. Mycologia 2023, 115, 768–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canna Research. Pythium—Pests and Diseases. Available online: https://www.canna.ca/articles/pythium-pests-diseases (accessed on 29 December 2025).

- Salcedo, A.F.; Purayannur, S.; Standish, J.R.; Miles, T.; Thiessen, L.; Quesada-Ocampo, L.M. Fantastic Downy Mildew Pathogens and How to Find Them: Advances in Detection and Diagnostics. Plants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, P.; Pellan, L.; Jaswa, A.; Cambon, M.C.; Chataigner, A.; Bonnard, O.; Raynal, M.; Debord, C.; Poeydebat, C.; Labarthe, S.; et al. Revealing microbial consortia that interfere with grapevine downy mildew through microbiome epidemiology. Environmental Microbiome 2025, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büttner, C.; von Bargen, S.; Bandte, M. Phytopathogenic viruses. In Principles of Plant-Microbe Interactions: Microbes for Sustainable Agriculture; Springer, 2014; pp. 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Clinic, Cleveland. Virus. Available online: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24861-virus (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Krauss, S.; Griebler, C.; Technikwissenschaften, D.A.d. Pathogenic microorganisms and viruses in groundwater; acatech, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Roblero, A.; Martínez Cano, D.J.; Diego-García, E.; Guillén-Navarro, G.K.; Iša, P.; Zarza, E. Metagenomic analysis of plant viruses in tropical fresh and wastewater. Environmental DNA 2024, 6, e416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrofanova, I.V.; Zakubanskiy, A.V.; Mitrofanova, O.V. Viruses infecting main ornamental plants: an overview. Ornamental Horticulture 2018, 24, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamelin, F.M.; Allen, L.J.S.; Prendeville, H.R.; Hajimorad, M.R.; Jeger, M.J. The evolution of plant virus transmission pathways. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2016, 396, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo-Franco, J.F.; Medina-Salguero, A.; Flores, F.; Chica, E.; Grinstead, S.; Mollov, D.; Quito-Avila, D.F. Exploring the virome of Vasconcellea x heilbornii: the first step towards a sustainable production program for babaco in Ecuador. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2020, 157, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A.; Fowkes, A.; Skelton, A.; Harju, V.; Buxton-Kirk, A.; Kelly, M.; Forde, S.; Pufal, H.; Conyers, C.; Ward, R. Using high-throughput sequencing in support of a plant health outbreak reveals novel viruses in Ullucus tuberosus (Basellaceae). Plant Pathology 2019, 68, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, M.; Cardona, D.; García, Y.G.; Higuita, M.; Gutiérrez, P.A.; Marín, M. Virome analysis for identification of viruses associated with asymptomatic infection of purple passion fruit (Passiflora edulis f. edulis) in Colombia. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2022, 97, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baráth, D.; Jaksa-Czotter, N.; Molnár, J.; Varga, T.; Balássy, J.; Szabó, L.K.; Kirilla, Z.; Tusnády, G.E.; Preininger, É.; Várallyay, É. Small RNA NGS revealed the presence of Cherry virus A and Little cherry virus 1 on apricots in Hungary. Viruses 2018, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pais da Cunha, A.T.; Chiumenti, M.; Ladeira, L.C.; Abou Kubaa, R.; Loconsole, G.; Pantaleo, V.; Minafra, A. High throughput sequencing from Angolan citrus accessions discloses the presence of emerging CTV strains. Virology Journal 2021, 18, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zikeli, K.; Berwarth, C.; Born, U.; Leible, T.; Jelkmann, W.; Hagemann, M.H. Prevalence, genetic diversity, and molecular detection of the apple hammerhead viroid in Germany. Front Microbiol 2025, 16, 1592572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, P.; Diksha, D.; Sharma, S.K.; Khan, Z.A.; Gupta, N.; Shimray, M.Y.; Prajapati, M.R.; Holkar, S.K.; Naik, S.; Saha, S.; et al. Understanding the dissemination of viruses and viroids identified through virome analysis of major grapevine rootstocks and RPA-based detection of prevalent grapevine virus B. Scientia Horticulturae 2024, 337, 113538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Osatuke, A.C.; Erich, G.; Stevens, K.; Hwang, M.S.; Al Rwahnih, M.; Fuchs, M. High-Throughput Sequencing Reveals Tobacco and Tomato Ringspot Viruses in Pawpaw. Plants 2022, 11, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Meier, S.K.; Park, H.; Baek, S.; Choi, M.S.; Ingle, R.A.; Hahn, Y. Identification of a novel potyvirus from the nickel-hyperaccumulating plant Senecio coronatus in South Africa. South African Journal of Botany 2025, 181, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-Y.; Kim, H.; Yi, S.-I.; Lim, S.; Park, J.M.; Cho, H.S.; Kim, H.; Kwon, S.-Y.; Moon, J.S. First report of Impatiens flower break virus infecting Impatiens walleriana in South Korea. Plant Disease 2017, 101, 394–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xia, F.; Wang, Y.; Yan, C.; Jia, A.; Zhang, Y. Characterization of a highly divergent Sugarcane mosaic virus from Canna indica L. by deep sequencing. BMC Microbiol 2019, 19, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amoia, S.S.; Minafra, A.; Nicoloso, V.; Loconsole, G.; Chiumenti, M. A New Jasmine Virus C Isolate Identified by Nanopore Sequencing Is Associated to Yellow Mosaic Symptoms of Jasminum officinale in Italy. Plants 2022, 11, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrigian, F.; LeBlanc, N.; Eriksen, R.L.; Bush, E.; Salamanca, L.R.; Salgado-Salazar, C. Uncovering the Fungus Responsible for Stem and Root Rot of False Indigo: Pathogen Identification, New Disease Description, and Genome Analyses. Plant Dis 2025, 109, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholthof, K.B.; Adkins, S.; Czosnek, H.; Palukaitis, P.; Jacquot, E.; Hohn, T.; Hohn, B.; Saunders, K.; Candresse, T.; Ahlquist, P.; et al. Top 10 plant viruses in molecular plant pathology. Mol Plant Pathol 2011, 12, 938–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, R.E.; Fonseca, D.M.; Nielsen, A.L.; Leskey, T.C.; Lockwood, J.L. Early detection of invasive exotic insect infestations using eDNA from crop surfaces. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2018, 16, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Rodriguez, J.; Ranger, Christopher M.; Leach, A.; Michel, A.; Reding, Michael E.; Canas, L. Using Environmental DNA to Detect and Identify Sweetpotato Whitefly Bemisia argentifolii and Twospotted Spider Mite Tetranychus urticae in Greenhouse-Grown Tomato Plants. Environmental DNA 2024, 6, e70026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver-Kanuya, E.; Harper, S.J. Detection and quantification of four viruses in Prunus pollen: Implications for biosecurity. J Virol Methods 2019, 271, 113673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smadi, M.; Lee, E.; Phelan, J.; Wang, A.; Bilodeau, G.J.; Pernal, S.F.; Guarna, M.M.; Rott, M.; Griffiths, J.S. Plant virus diversity in bee and pollen samples from apple (Malus domestica) and sweet cherry (Prunus avium) agroecosystems. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santala, J.; Samuilova, O.; Hannukkala, A.; Latvala, S.; Kortemaa, H.; Beuch, U.; Kvarnheden, A.; Persson, P.; Topp, K.; Ørstad, K.; et al. Detection, distribution and control of Potato mop-top virus, a soil-borne virus, in northern Europe. Annals of Applied Biology 2010, 157, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, M.; Anderson, J.M. Development of a multiplexed PCR detection method for Barley and Cereal yellow dwarf viruses, Wheat spindle streak virus, Wheat streak mosaic virus and Soil-borne wheat mosaic virus. J Virol Methods 2008, 148, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Han, Y.; Yu, Z.; Tian, S.; Sun, P.; Shi, Y.; Peng, C.; Gu, T.; Li, Z. Fungi in Horticultural Crops: Promotion, Pathogenicity and Monitoring. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.; Van Kan, J.A.; Pretorius, Z.A.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Di Pietro, A.; Spanu, P.D.; Rudd, J.J.; Dickman, M.; Kahmann, R.; Ellis, J.; et al. The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol Plant Pathol 2012, 13, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnaccia, V.; Aiello, D.; Polizzi, G.; Crous, P.W.; Sandoval-Denis, M. Soilborne diseases caused by Fusarium and Neocosmospora spp. on ornamental plants in Italy. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 2019, 58, 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Gullino, M.L.; Daughtrey, M.L.; Garibaldi, A.; Elmer, W.H. Fusarium wilts of ornamental crops and their management. Crop Protection 2015, 73, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, F.F.; Iacomi, B.M. Pathogenic mycobiota of ornamental plants from green area in the city of Bucharest, Romania. Scientific Papers. Series A. Agronomy 2024, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaccia, V.; Gilardi, G.; Martino, I.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L. Species diversity in Colletotrichum causing anthracnose of aromatic and ornamental Lamiaceae in Italy. Agronomy 2019, 9, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Manawasinghe, I.; Lin, Y.; Jayawardena, R.; McKenzie, E.; Hyde, K.; Xiang, M. Identification and characterization of Colletotrichum species associated with ornamental plants in Southern China. Mycosphere 2023, 14, 262–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, R.; Menkis, A.; Skogström, O.; Espes, C.; Brogren-Mohlin, E.-K.; Larsson, M.; Olson, Å. The development of foliar fungal communities of nursery-grown Pinus sylvestris seedlings. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 2023, 38, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérubé, J.A.; Gagné, P.N.; Ponchart, J.P.; Phelan, J.; Varga, A.; James, D. Heterobasidion species detected using High Throughput Sequencing (HTS) methods on British Columbia nursery plants. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 2019, 41, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.F.; Todd, C.; Rolshausen, P.E.; Cantu, D. Nursery origin and propagation stage influence the endophytic fungal communities inhabiting grapevine planting stocks. Phytobiomes Journal 2025, 9, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lade, S.B.; Štraus, D.; Oliva, J. Variation in fungal community in grapevine (Vitis vinifera) nursery stock depends on nursery, variety and rootstock. Journal of Fungi 2022, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.K.; Hovmøller, M.S. Aerial dispersal of pathogens on the global and continental scales and its impact on plant disease. Science 2002, 297, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, K.; Mueller, D.; Buck, J.; Fowler, J. Quarantines and ornamental rusts; American Pathological Society: St. Paul, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann, V.; Børja, I.; Hietala, A.M.; Kirisits, T.; Solheim, H. Ash dieback: pathogen spread and diurnal patterns of ascospore dispersal, with special emphasis on Norway. EPPO Bulletin 2011, 41, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldi, E.; Tiley, A.; O’Hanlon, R.; Murphy, B.R.; Hodkinson, T.R. Ash dieback and other pests and pathogens of Fraxinus on the island of Ireland. In Proceedings of the Biology and Environment: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 2022; pp. 85–122. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Braun, U. Powdery mildews on crops and ornamentals in Canada: a summary of the phylogeny and taxonomy from 2000–2019. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 2022, 44, 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, S.; Sugiyama, Y.; Nagano, M.; Doi, H. Influence of DNA extraction kits on freshwater fungal DNA metabarcoding. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congram, M.; Torres Vilaça, S.; Wilson, C.C.; Kyle, C.J.; Lesbarrères, D.; Wikston, M.J.H.; Beaty, L.; Murray, D.L. Tracking the prevalence of a fungal pathogen, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (chytrid fungus), using environmental DNA. Environmental DNA 2022, 4, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, L.C.; Jusino, M.A.; Chambers, R.M.; Skelton, J. Community structure and functional diversity of aquatic fungi are correlated with water quality: Insights from multi-marker analysis of environmental DNA in a coastal watershed. Environmental DNA 2024, 6, e576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.E.; Belaouni, H.A.; McClure, A.; McCullough, K.; Craig, D.; McKeown, J.; Stevenson, M.A.; Carmichael, E.; Dalzell, J.; O’Hanlon, R.; et al. Using Environmental DNA as a Plant Health Surveillance Tool in Forests. Forests 2025, 16, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandelier, A.; Massot, M.; Fabreguettes, O.; Gischer, F.; Teng, F.; Robin, C. Early detection of Cryphonectria parasitica by real-time PCR. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2019, 153, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke-Borowczyk, J.; Kowalkowski, W.; Kartawik, N.; Baranowska, M.; Barzdajn, W. The soil fungal communities in nurseries producing Abies alba. Baltic Forestry 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowska, M.; Behnke-Borowczyk, J.; Barzdajn, W.; Szmyt, J.; Korzeniewicz, R.; Łukowski, A.; Memišević-Hodžić, M.; Kartawik, N.; Kowalkowski, W. Effects of nursery production methods on fungal community diversity within soil and roots of Abies alba Mill. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 21284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, D.; Mills, J.G.; Gellie, N.J.C.; Bissett, A.; Lowe, A.J.; Breed, M.F. High-throughput eDNA monitoring of fungi to track functional recovery in ecological restoration. Biological Conservation 2018, 217, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frøslev, T.G.; Kjøller, R.; Bruun, H.H.; Ejrnæs, R.; Hansen, A.J.; Læssøe, T.; Heilmann-Clausen, J. Man against machine: Do fungal fruitbodies and eDNA give similar biodiversity assessments across broad environmental gradients? Biological Conservation 2019, 233, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, J.; Genin, S.; Magori, S.; Citovsky, V.; Sriariyanum, M.; Ronald, P.; Dow, M.; Verdier, V.; Beer, S.V.; Machado, M.A.; et al. Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Mol Plant Pathol 2012, 13, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, J.R.; Bartoli, C. Plant pathogenic bacteria in open irrigation systems: what risk for crop health? Plant Pathology 2015, 64, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlovskis, Z.; Canale, M.C.; Thole, V.; Pecher, P.; Lopes, J.R.; Hogenhout, S.A. Insect-borne plant pathogenic bacteria: getting a ride goes beyond physical contact. Curr Opin Insect Sci 2015, 9, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.M.M.; Merfa, M.V.; Takita, M.A.; De Souza, A.A. Persistence in Phytopathogenic Bacteria: Do We Know Enough? Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, A.; O’Regan, F.; Fleming, C.C.; Moreland, B.P.; Pollock, J.A.; McGuinness, B.W.; Hodkinson, T.R. Bleeding canker of horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum) in Ireland: incidence, severity and characterization using DNA sequences and real-time PCR. Plant Pathology 2016, 65, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Johnson, M.A.; Hansen, M.A.; Bush, E.; Li, S.; Vinatzer, B.A. Metagenomic sequencing for detection and identification of the boxwood blight pathogen Calonectria pseudonaviculata. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keremane, M.; Singh, K.; Ramadugu, C.; Krueger, R.R.; Skaggs, T.H. Next Generation Sequencing, and Development of a Pipeline as a Tool for the Detection and Discovery of Citrus Pathogens to Facilitate Safer Germplasm Exchange. Plants 2024, 13, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, L.-P.; Li, J.-D.; Yan, M.; Gao, Y.-H.; Zhang, J.-J.; Moural, T.W.; Zhu, F.; Wang, X.-M. Illumina Sequencing of 18S/16S rRNA Reveals Microbial Community Composition, Diversity, and Potential Pathogens in 17 Turfgrass Seeds. Plant Disease 2021, 105, 1328–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; van Elsas, J.D. Mechanisms and ecological implications of the movement of bacteria in soil. Applied Soil Ecology 2018, 129, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashan, Y. Migration of the rhizosphere bacteria Azospirillum brusilense and Pseudomonas fluorescens towards wheat roots in the soil. Microbiology 1986, 132, 3407–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covelli, J.M.; Althabegoiti, M.J.; López, M.F.; Lodeiro, A.R. Swarming motility in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Research in Microbiology 2013, 164, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bové, J.M.; Garnier, M. Phloem-and xylem-restricted plant pathogenic bacteria. Plant Science 2003, 164, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picot, A.; Cobo-Díaz, J.F.; Pawtowski, A.; Donot, C.; Legrand, F.; Le Floch, G.; Déniel, F. Water Microbiota in Greenhouses With Soilless Cultures of Tomato by Metabarcoding and Culture-Dependent Approaches. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozdrój, J.; Ropek, D.R.; Frączek, K.; Bulski, K.; Breza-Boruta, B. Microbial Indoor Air Quality Within Greenhouses and Polytunnels Is Crucial for Sustainable Horticulture (Malopolska Province, Poland Conditions). Sustainability 2024, 16, 10058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffaud, C.-H.; Morris, C.E. Detection of Pseudomonas syringae pv. aptata in irrigation water retention basins by immunofluorescence colony-staining. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2002, 108, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.E.; Sands, D.; Vanneste, J.; Montarry, J.; Oakley, B.; Guilbaud, C.; Glaux, C. Inferring the evolutionary history of the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae from its biogeography in headwaters of rivers in North America, Europe, and New Zealand. MBio 2010, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elphinstone, J.; Stanford, H.; Stead, D. Detection of Ralstonia solanacearum in potato tubers, Solanum dulcamara and associated irrigation water. In Bacterial wilt disease: Molecular and ecological aspects; Springer, 1998; pp. 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.; Sinha, S.; Yadav, D.; Chaudhary, G. Detection of Ralstonia solanacearum from asymptomatic tomato plants, irrigation water, and soil through non-selective enrichment medium with hrp gene-based bio-PCR. Current microbiology 2014, 69, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.; Franc, G.; Maddox, D.; Michaud, J.; McCarter-Zorner, N. Presence of Erwinia carotovora in surface water in North America. Journal of Applied Microbiology 1987, 62, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurila, J.; Ahola, V.; Lehtinen, A.; Joutsjoki, T.; Hannukkala, A.; Rahkonen, A.; Pirhonen, M. Characterization of Dickeya strains isolated from potato and river water samples in Finland. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2008, 122, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmatjidou, V.; Fynn, R.; Hoitink, H. Dissemination and transmission of. Xanthomonas campestris pv. begoniae in an ebb and flow irrigation system 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gent, D.H.; Lang, J.M.; Bartolo, M.E.; Schwartz, H.F. Inoculum sources and survival of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. allii in Colorado. Plant disease 2005, 89, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Wagner, L. Control of bacterial canker and root knot of hydroponic tomatoes. 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Qiagen. FAQ-114 How should I store plant material for DNA isolation using the DNeasy Plant Kit? Available online: https://www.qiagen.com/us/resources/faq/114 (accessed on 08 December 2025).

- Sylphium Molecular Ecology. Complete eDNA sampling sets (20x). Available online: https://sylphium.com/webshop/product/syl009/ (accessed on 10 December 202).

- Merck, KGaA. Reinforced Membrane Filter. Millipore, filter diam. 47mm, hydrophilic. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/IE/en/product/mm/rw1904700 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Cooper Pegler, NAD. Cooper Pegler CP15 Sprayer 15 LTR. Available online: https://www.nad.ie/product/cooper-pegler-cp15-sprayer-15-ltr/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Sartorius, AG. Re-usable Syringe Filter Holder 25mm. Available online: https://shop.sartorius.com/ie/p/re-usable-syringe-filter-holder-25-mm/16517----------E (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Sartorius, AG. MD8 Airport Portable Air Sampler. Available online: https://shop.sartorius.com/ie/p/md8-airport-portable-air-sampler/16757 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Chemical, Cayman. Coriolis Compact Air Sampler Item No. 38284. Available online: https://www.caymanchem.com/product/38284/coriolis-registered-compact-air-sampler?srsltid=AfmBOoo0GnVPEZEWh0SEMThxeTBDhAXn7IHyhECmLvLHrJPKBfEMicFH (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Sartorius, AG. Disposable Gelatine Membrane Filters, Diameter 80mm, triple packed, Pack Size 10. Available online: https://shop.sartorius.com/ie/p/disposable-gelatine-membrane-filters-diameter-80mm-triple-packed-pack-size-10/Gelatine-Filter-Method (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Tremblay, É.D.; Duceppe, M.O.; Thurston, G.B.; Gagnon, M.C.; Côté, M.J.; Bilodeau, G.J. High-resolution biomonitoring of plant pathogens and plant species using metabarcoding of pollen pellet contents collected from a honey bee hive. Environmental DNA 2019, 1, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redekar, N.R.; Bourret, T.B.; Eberhart, J.L.; Johnson, G.E.; Pitton, B.J.; Haver, D.L.; Oki, L.R.; Parke, J.L. The population of oomycetes in a recycled irrigation water system at a horticultural nursery in southern California. Water Research 2020, 183, 116050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, K.P.; Pandit, M.; Hinson, R. Irrigation water sources and irrigation application methods used by US plant nursery producers. Water Resources Research 2016, 52, 698–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittwer, C.; Nowak, C.; Strand, D.A.; Vrålstad, T.; Thines, M.; Stoll, S. Comparison of two water sampling approaches for eDNA-based crayfish plague detection. Limnologica 2018, 70, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettitt, T.R. Monitoring oomycetes in water: combinations of methodologies used to answer key monitoring questions. Frontiers in Horticulture 2023, 2, 1210535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scibetta, S.; Schena, L.; Chimento, A.; Cacciola, S.O.; Cooke, D.E. A molecular method to assess Phytophthora diversity in environmental samples. J Microbiol Methods 2012, 88, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, M.E.; Ferrante, J.A.; Meigs-Friend, G.; Ulmer, A. Improving eDNA yield and inhibitor reduction through increased water volumes and multi-filter isolation techniques. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, J.; Valentini, A.; Dejean, T.; Montarsi, F.; Taberlet, P.; Glaizot, O.; Fumagalli, L. Detection of Invasive Mosquito Vectors Using Environmental DNA (eDNA) from Water Samples. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0162493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ficetola, G.F.; Miaud, C.; Pompanon, F.; Taberlet, P. Species detection using environmental DNA from water samples. Biol Lett 2008, 4, 423–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schabacker, J.C.; Amish, S.J.; Ellis, B.K.; Gardner, B.; Miller, D.L.; Rutledge, E.A.; Sepulveda, A.J.; Luikart, G. Increased eDNA detection sensitivity using a novel high-volume water sampling method. Environmental DNA 2020, 2, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinlo, R.; Gleeson, D.; Lintermans, M.; Furlan, E. Methods to maximise recovery of environmental DNA from water samples. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0179251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hammes, F.; Boon, N.; Egli, T. Quantification of the filterability of freshwater bacteria through 0.45, 0.22, and 0.1 microm pore size filters and shape-dependent enrichment of filterable bacterial communities. Environ Sci Technol 2007, 41, 7080–7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.E.; Huyvaert, K.P.; Piaggio, A.J. No filters, no fridges: a method for preservation of water samples for eDNA analysis. BMC Research Notes 2016, 9, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Català, S.; Pérez-Sierra, A.; Abad-Campos, P. The use of genus-specific amplicon pyrosequencing to assess Phytophthora species diversity using eDNA from soil and water in Northern Spain. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0119311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, N.J.; Nouri, M.T.; Browne, G.T. Full-Length ITS Amplicon Sequencing Resolves Phytophthora Species in Surface Waters Used for Orchard Irrigation in California’s San Joaquin Valley. Plant Dis 2024, 108, 3562–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anteljević, M.; Rosić, I.; Medić, O.; Ranković, T.; Sunjog, K.; Kračun-Kolarević, M.; Kolarević, S.; Dreo, T.; Benčič, A.; Berić, T.; et al. Irrigation systems as reservoirs of diverse and pathogenic Pseudomonas syringae strains endangering crop health. Water Research X 2025, 28, 100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, M.; McComb, J.A.; O’Brien, P.A.; Hardy, G.E.S.J. Survival of Phytophthora cinnamomi as oospores, stromata, and thick-walled chlamydospores in roots of symptomatic and asymptomatic annual and herbaceous perennial plant species. Fungal biology 2013, 117, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; Andrade, D.; Xue, L.; McKinney, N. Prediction of plant diseases through modelling and monitoring airborne pathogen dispersal. CABI Reviews 2010, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnpicharnchai, P.; Pumkaeo, P.; Siriarchawatana, P.; Likhitrattanapisal, S.; Mayteeworakoon, S.; Ingsrisawang, L.; Boonsin, W.; Eurwilaichitr, L.; Ingsriswang, S. AirDNA sampler: An efficient and simple device enabling high-yield, high-quality airborne environment DNA for metagenomic applications. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0287567. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, M.; Timm, M.; Hansen, E.W.; Madsen, A.M. Comparison of sampling methods for the assessment of indoor microbial exposure. Indoor Air 2012, 22, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, E.L.; Economou, C.K.; Bennett, F.J.; Dyer, C.E.; Adams, K.; McRobie, B.; Drinkwater, R.; Littlefair, J.E. Measuring biodiversity from DNA in the air. Current Biology 2022, 32, 693–700.e695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Radford, D.; Hambleton, S. Towards Improved Detection and identification of rust fungal pathogens in environmental samples using a metabarcoding approach. Phytopathology 2022, 112, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.H.; Ward, E.; McCartney, H.A. Methods for integrated air sampling and DNA analysis for detection of airborne fungal spores. Applied and environmental microbiology 2001, 67, 2453–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, S.R.; Bennett, A.M.; Speight, S.E.; Benbough, J.E. An assessment of the Sartorius MD8 microbiological air sampler. J Appl Bacteriol 1996, 80, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, E.; Sindt, C.; Verdier, A.; Galan, C.; O’Donoghue, L.; Parks, S.; Thibaudon, M. Performance of the Coriolis air sampler, a high-volume aerosol-collection system for quantification of airborne spores and pollen grains. Aerobiologia 2008, 24, 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Banchi, E.; Ametrano, C.G.; Tordoni, E.; Stanković, D.; Ongaro, S.; Tretiach, M.; Pallavicini, A.; Muggia, L.; Verardo, P.; Tassan, F.; et al. Environmental DNA assessment of airborne plant and fungal seasonal diversity. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 738, 140249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordoni, E.; Ametrano, C.G.; Banchi, E.; Ongaro, S.; Pallavicini, A.; Bacaro, G.; Muggia, L. Integrated eDNA metabarcoding and morphological analyses assess spatio-temporal patterns of airborne fungal spores. Ecological Indicators 2021, 121, 107032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, J.-M.; Paillisson, J.-M.; Treguier, A.; Petit, E. The downside of eDNA as a survey tool in water bodies. Journal of Applied Ecology 2015, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pochon, X.; Zaiko, A.; Fletcher, L.M.; Laroche, O.; Wood, S.A. Wanted dead or alive? Using metabarcoding of environmental DNA and RNA to distinguish living assemblages for biosecurity applications. PloS one 2017, 12, e0187636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Oomycete group | Recommended sample type | References |

|---|---|---|

| Pythium spp. | Growing media; water | [24,46,48,49,50,52] |

| Phytophthora spp. | Growing media; water; air | [22,24,46,48,50] |

| Downy mildew spp. | Air | [48,53] |

| Sample type | Organisms detectable | Cost of single set up | Consumables cost per sample (not incl. extraction or sequencing) | Requirements (sampling) | Requirements (storage) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant material | All | Negligible | Negligible | Sterile blade for taking portion of plant | Liquid nitrogen and -70 °C freezer OR silica gel in airtight container | [139] |

| Water | All | Varies depending on set up required, e.g., Knapsack Sprayer 15L* costs ca. 250-300EUR and re-usable syringe filter holders cost ca. 200EUR | From 1EUR per sample for consumables (i.e., filters and storage vials) OR ca. 15EUR for complete single-use kit | Appropriate filters, filter units, and pumps OR commercially available kit | Buffer solution & sterile container | [140,141,142,143] |

| Air | Fungi, viruses, oomycetes | e.g., Air samplers** cost 5,000-15,000EUR | Filters cost from ca. 20EUR per sample | Air sampler AND appropriate filters, filter units, and pumps | Buffer solution & sterile container | [144,145,146] |

| Growing media | Fungi, bacteria, oomycetes | Negligible | Negligible | Sterile shovel/spoon, bag for homogenizing | Buffer solution & sterile container | [25,50] |

| Pathogen group | Organism | Water volume | Filter used | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oomycetes | Phytophthora | 10L | 5µm cellulose acetate and cellulose nitrate mixture | [160] |

| Phytophthora, Pythium, Phytopythium | 1L | 5µm mixed cellulose ester filters | [46] | |

| Phytophthora | 3 x 5L | 1.2µm mixed cellulose ester filters | [22] | |

| Phytophthora | ~15L | Combined a 100µm nylon mesh filter, a 20µm nylon mesh filter, and a 5µm nitrocellulose filter | [161] | |

| Bacteria | Pseudomonas syringae | 1L | 0.45µm mixed cellulose ester filters | [162] |

| Fungi | Aquatic fungi | 1L | 0.7µm GF/F glass filters | [107] |

| Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (fungal amphibian pathogen) | <500mL (average 270mL) | 0.22µm capsule filters | [108] | |

| Aquatic fungi | 3 x 2L | 5µm polyethersulfone (PES) membrane filters | [109] | |

| Viruses | Phytopathogenic viruses from the Virgaviridae family | 15mL | n/a | [68] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).