Submitted:

27 November 2024

Posted:

28 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Genomes and Prophage Identification

2.2. Annotation of Prophage Genes

2.3. Functional Categorization of CDSs

2.4. Identification of Virulence Factors and Antibiotic Resistance Genes

2.5. Comparative Genomic Analyses and Defense System Detection

3. Results

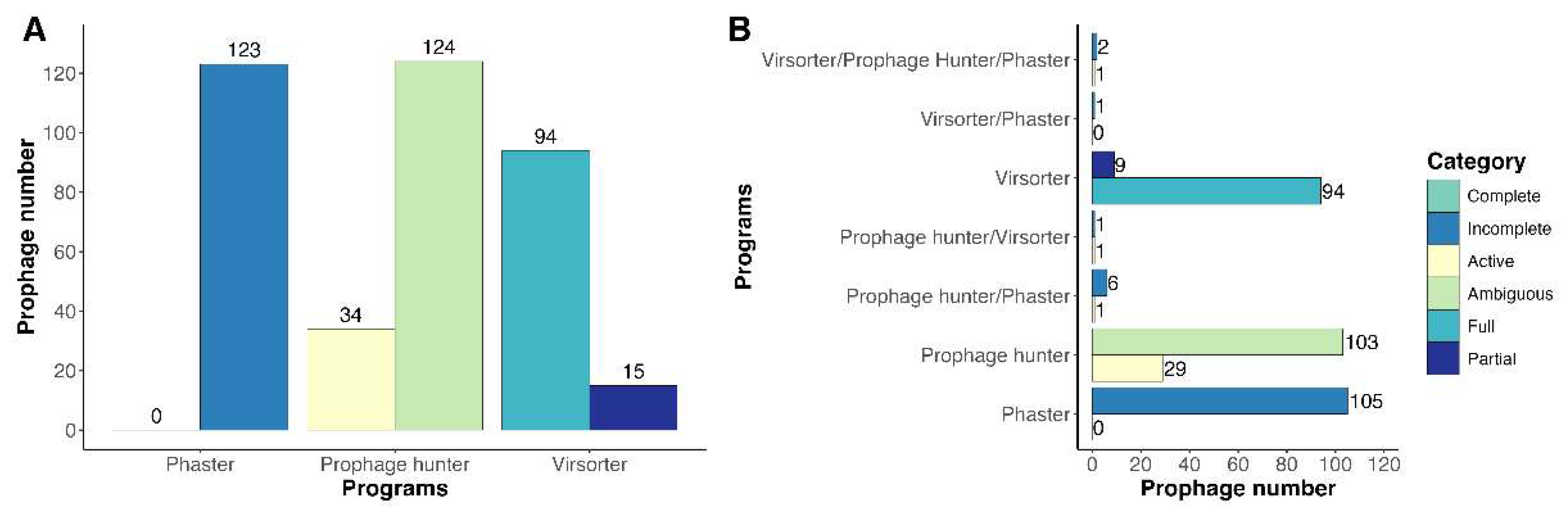

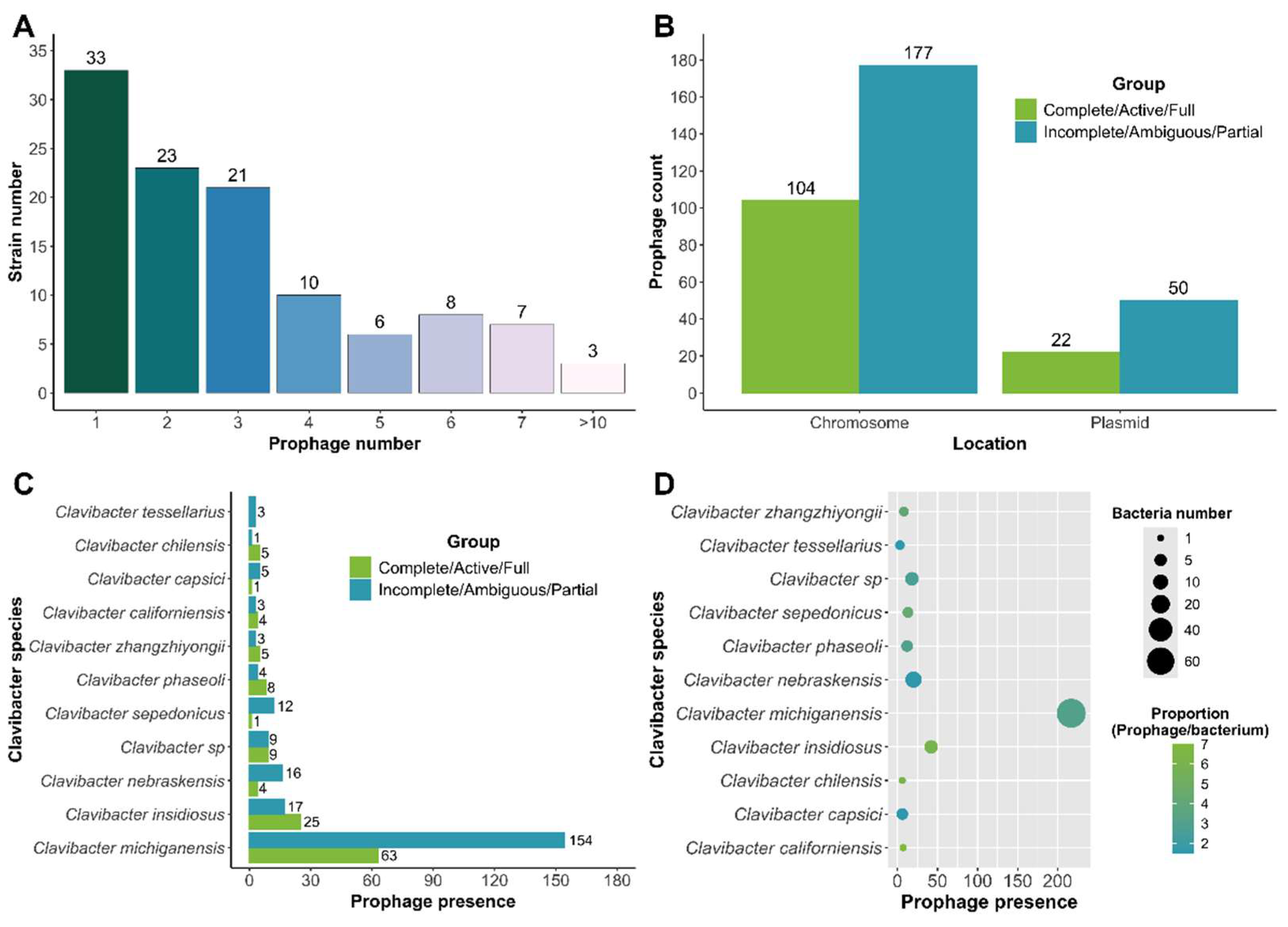

3.1. Identification and Prevalence of Prophages in Clavibacter Strains

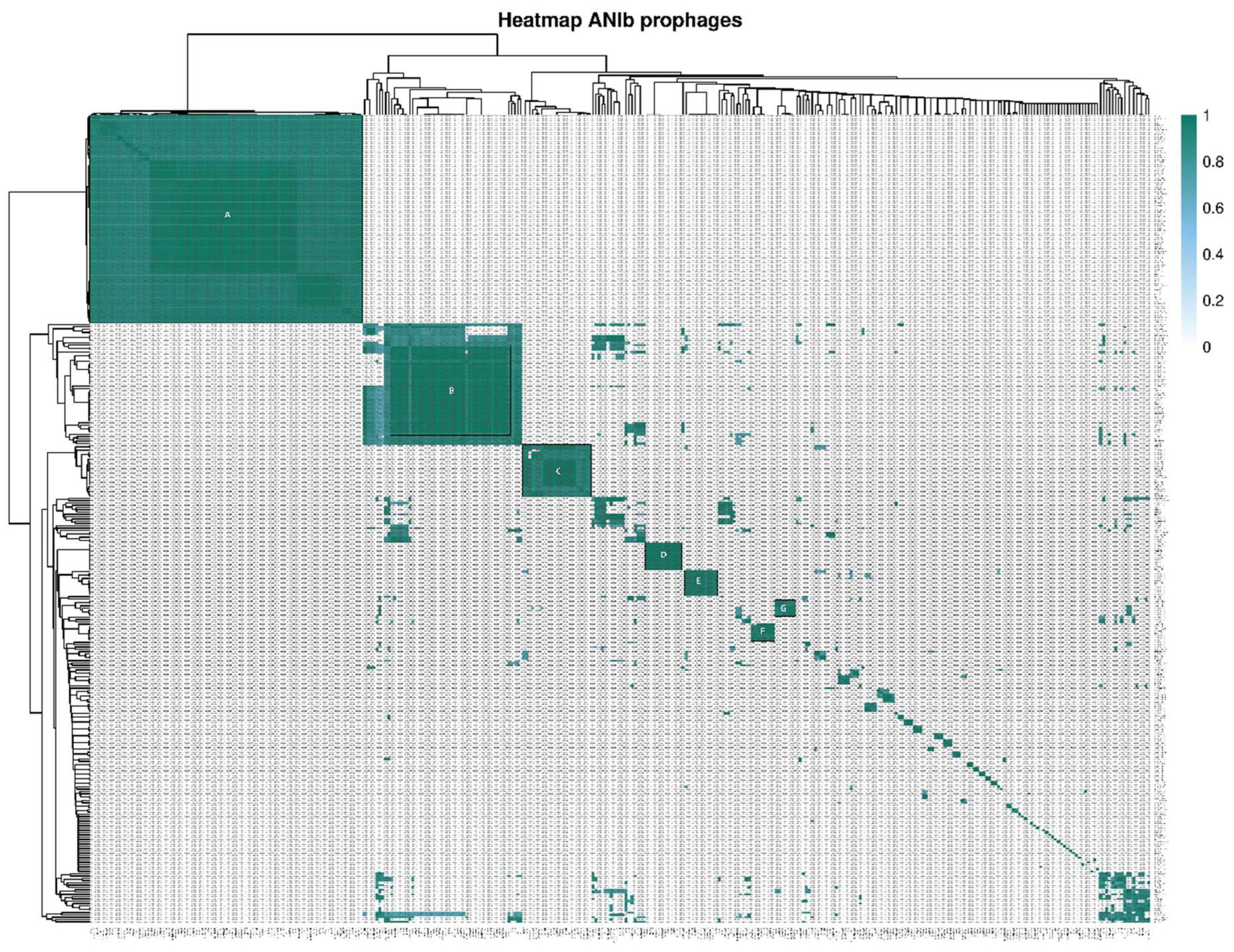

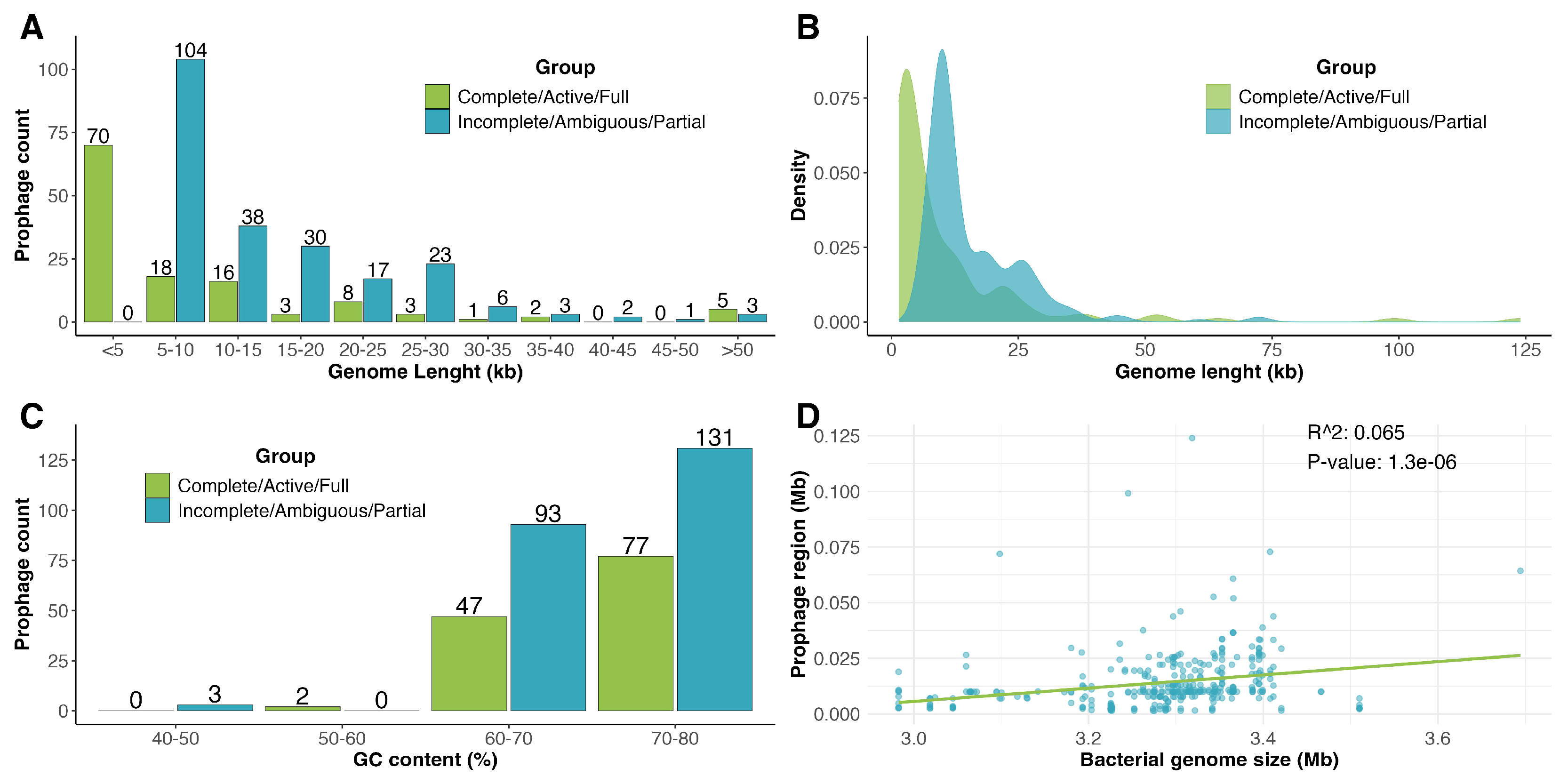

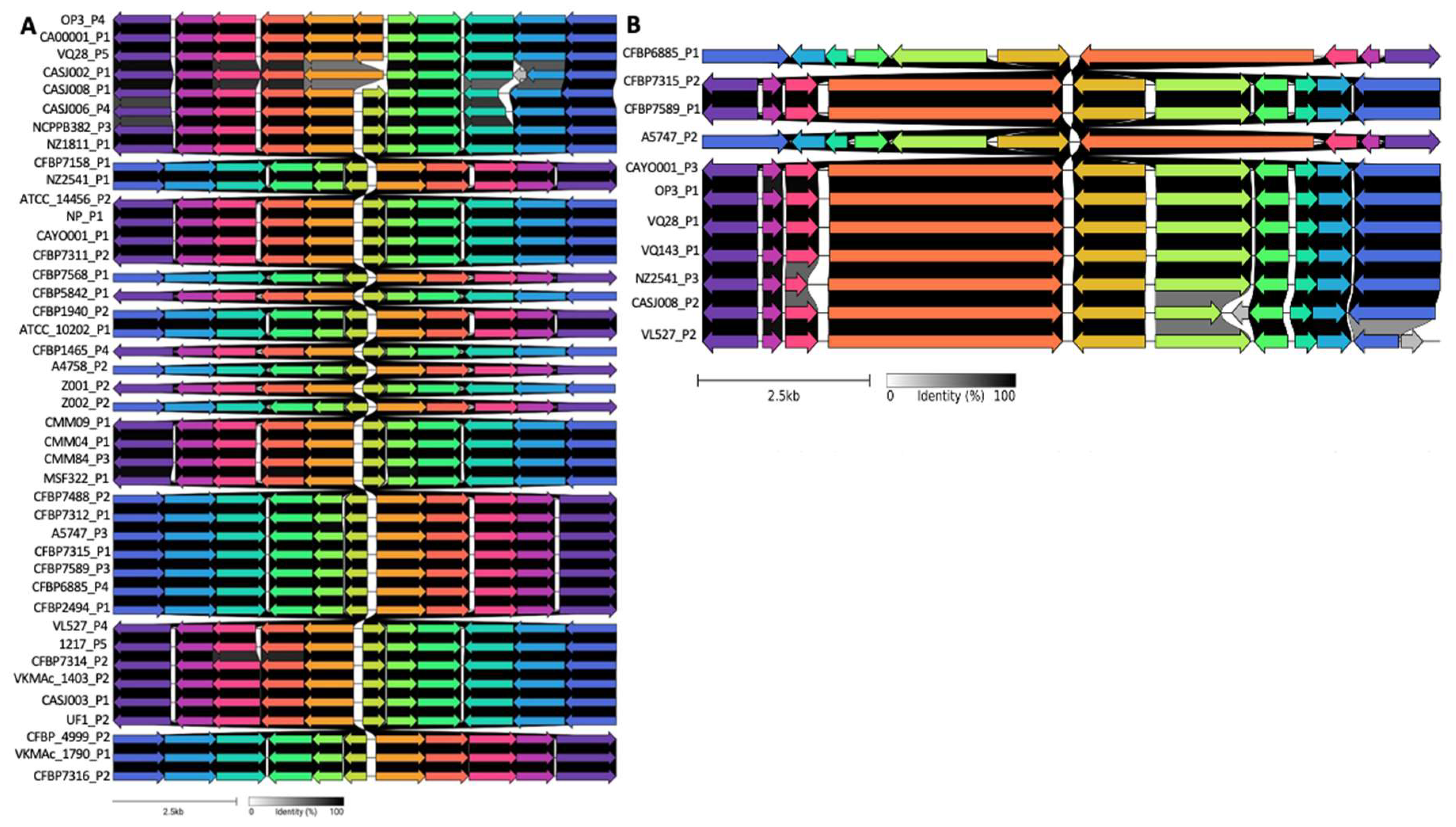

3.2. Comparative Genomic Analyses of Clavibacter Prophages

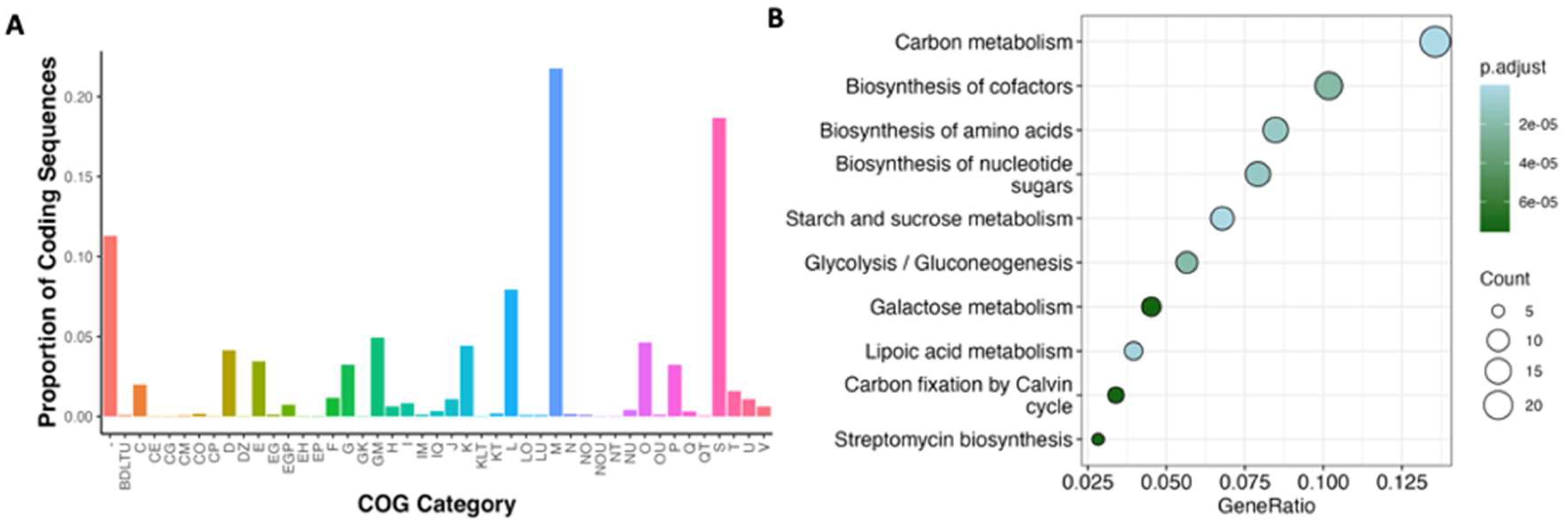

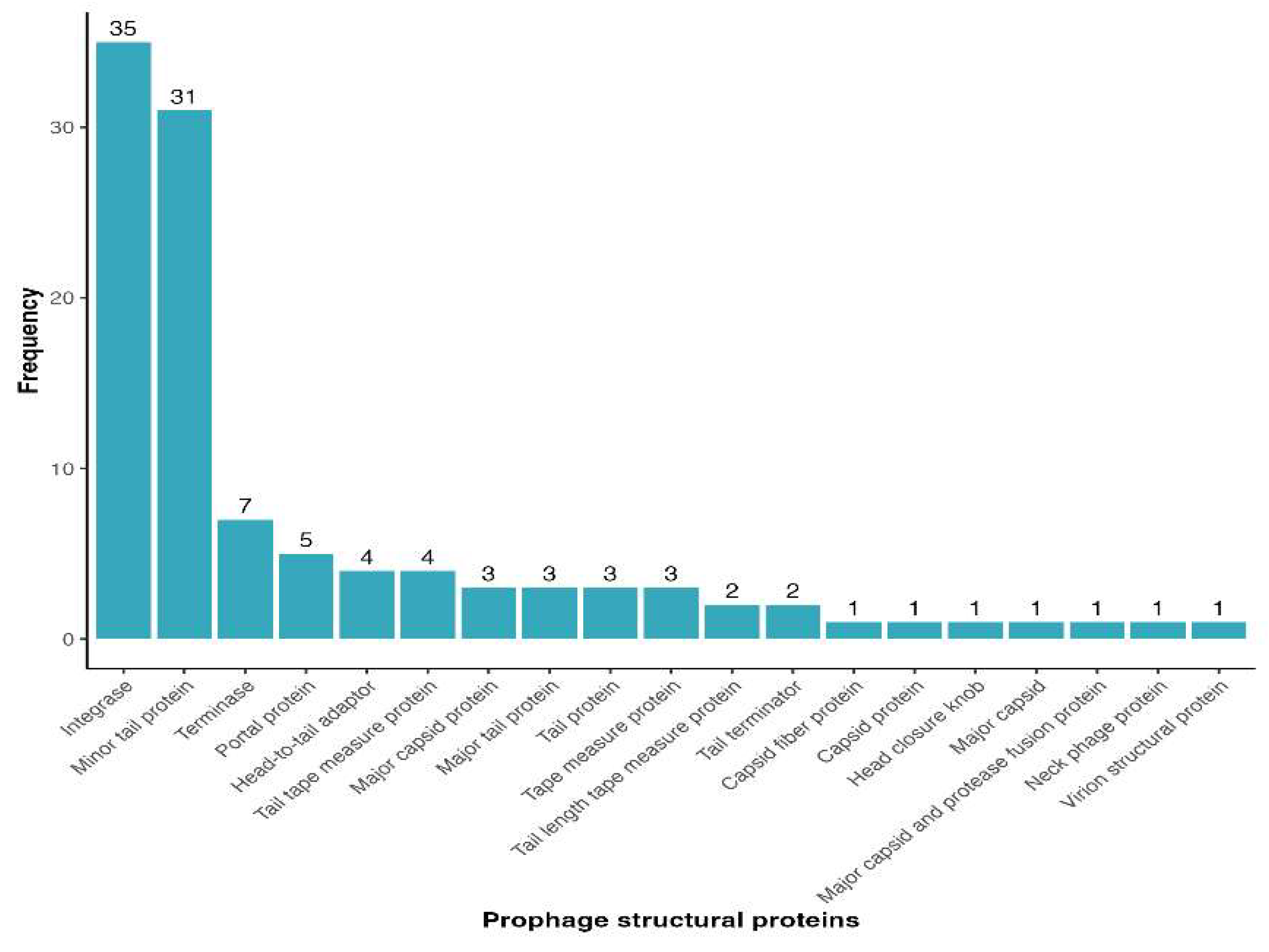

3.3. Functional Annotation of Clavibacter Prophages

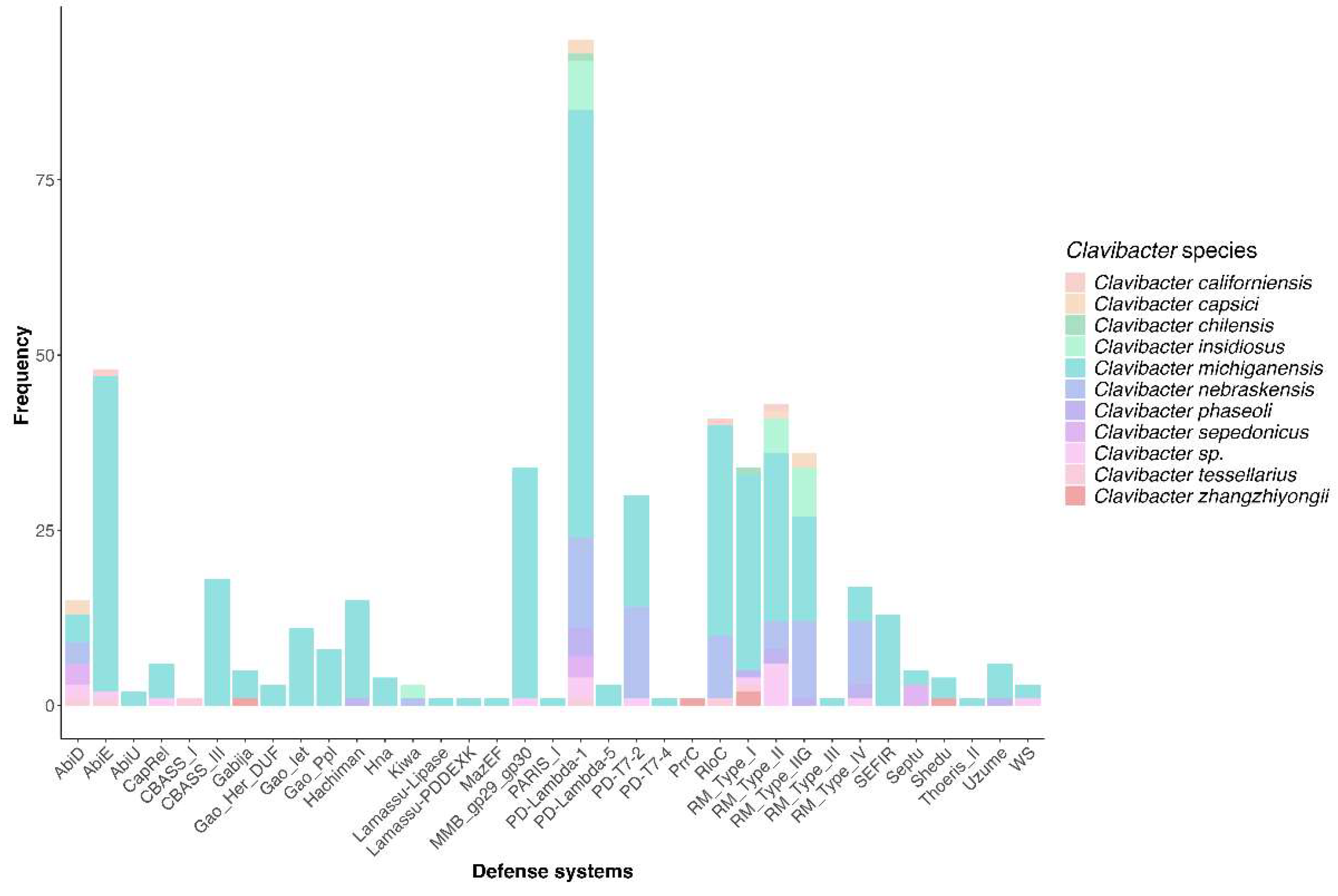

3.5. Diversity of Defense Systems

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martins, P.M.M.; Merfa, M. V.; Takita, M.A.; De Souza, A.A. Persistence in Phytopathogenic Bacteria: Do We Know Enough? Front Microbiol 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tambong, J.; Yuan, K. (Xiaoli); Chen, W.; Xu, H.; Lévesque, C.A.; De Boer, S.H. Re-Classification of Clavibacter Michiganensis Subspecies on the Basis of Whole-Genome and Multi-Locus Sequence Analyses. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2018, 68, 234–240. [CrossRef]

- EPPO <scp>PM</Scp> 7/42 (3) Clavibacter Michiganensis Subsp. Michiganensis. EPPO Bulletin 2016, 46, 202–225. [CrossRef]

- Bragard, C.; Dehnen-Schmutz, K.; Di Serio, F.; Gonthier, P.; Jaques Miret, J.A.; Justesen, A.F.; MacLeod, A.; Magnusson, C.S.; Milonas, P.; Navas-Cortes, J.A.; et al. Pest Categorisation of Clavibacter Sepedonicus. EFSA Journal 2019, 17. [CrossRef]

- Metzler, M.C.; Laine, M.J.; De Boer, S.H. The Status of Molecular Biological Research on the Plant Pathogenic Genus Clavibacter. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1997, 150.

- Jahr, H.; Bahro, R.; Burger, A.; Ahlemeyer, J.; Eichenlaub, R. Interactions between Clavibacter Michiganensis and Its Host Plants. Environ Microbiol 1999, 1, 113–118. [CrossRef]

- Nandi, M.; Macdonald, J.; Liu, P.; Weselowski, B.; Yuan, Z.C. Clavibacter Michiganensis Ssp. Michiganensis: Bacterial Canker of Tomato, Molecular Interactions and Disease Management. Mol Plant Pathol 2018, 19, 2036–2050.

- Bruneaux, M.; Ashrafi, R.; Kronholm, I.; Laanto, E.; Örmälä-Tiznado, A.; Galarza, J.A.; Zihan, C.; Kubendran Sumathi, M.; Ketola, T. The Effect of a Temperature-sensitive Prophage on the Evolution of Virulence in an Opportunistic Bacterial Pathogen. Mol Ecol 2022, 31, 5402–5418. [CrossRef]

- Tesson, F.; Hervé, A.; Mordret, E.; Touchon, M.; d’Humières, C.; Cury, J.; Bernheim, A. Systematic and Quantitative View of the Antiviral Arsenal of Prokaryotes. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 2561. [CrossRef]

- Fillol-Salom, A.; Alsaadi, A.; de Sousa, J.A.M.; Zhong, L.; Foster, K.R.; Rocha, E.P.C.; Penadés, J.R.; Ingmer, H.; Haaber, J. Bacteriophages Benefit from Generalized Transduction. PLoS Pathog 2019, 15. [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Stanton, E.; Ciezki, K.; Parrell, D.; Bozile, M.; Pike, D.; Forst, S.A.; Jeong, K.C.; Ivanek, R.; Döpfer, D.; et al. Evolution of the Stx2-Encoding Prophage in Persistent Bovine Escherichia Coli O157:H7 Strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013, 79, 1563–1572. [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.R.; Monteiro, R.; Azeredo, J. Genomic Analysis of Acinetobacter Baumannii Prophages Reveals Remarkable Diversity and Suggests Profound Impact on Bacterial Virulence and Fitness. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Ingmer, H.; Gerlach, D.; Wolz, C. Temperate Phages of Staphylococcus Aureus. Microbiol Spectr 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, M.; Lee, J.H.; Canchaya, C.; Zink, R.; Leahy, S.; Moreno-Munoz, J.A.; O’Connell-Motherway, M.; Higgins, D.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; O’Sullivan, D.J.; et al. Prophage-like Elements in Bifidobacteria: Insights from Genomics, Transcription, Integration, Distribution, and Phylogenetic Analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005, 71. [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Sadiq, F.A.; Han, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Ross, R.P.; Lu, W.; Chen, W. Identification, Characterization, and Phylogenetic Analysis of Eight New Inducible Prophages in Lactobacillus. Virus Res 2020, 286, 198003. [CrossRef]

- Remmington, A.; Haywood, S.; Edgar, J.; Green, L.R.; de Silva, T.; Turner, C.E. Cryptic Prophages within a Streptococcus Pyogenes Genotype Emm4 Lineage. Microb Genom 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.C.; Goldman, B.S.; Goodner, B.; Setubal, J.C.; Farrand, S.K.; Nester, E.W.; Burr, T.J.; Banta, L.; Dickerman, A.W.; Paulsen, I.; et al. Genome Sequences of Three Agrobacterium Biovars Help Elucidate the Evolution of Multichromosome Genomes in Bacteria. J Bacteriol 2009, 191, 2501–2511. [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.J.; Coulthurst, S.J.; Komitopoulou, E.; Salmond, G.P.C. Two Mobile Pectobacterium Atrosepticum Prophages Modulate Virulence. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2010, 304, 195–202. [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, R. May the Phage Be With You? Prophage-Like Elements in the Genomes of Soft Rot Pectobacteriaceae: Pectobacterium Spp. and Dickeya Spp. Front Microbiol 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Lelis, T.; Peng, J.; Barphagha, I.; Chen, R.; Ham, J.H. The Virulence Function and Regulation of the Metalloprotease Gene PrtA in the Plant-Pathogenic Bacterium Burkholderia Glumae. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2019, 31, 841–852. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.A.; Stulberg, M.J.; Huang, Q. Prophage Rs551 and Its Repressor Gene Orf14 Reduce Virulence and Increase Competitive Fitness of Its Ralstonia Solanacearum Carrier Strain UW551. Front Microbiol 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Roszniowski, B.; McClean, S.; Drulis-Kawa, Z. Burkholderia Cenocepacia Prophages—Prevalence, Chromosome Location and Major Genes Involved. Viruses 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Swain, D.M.; Yadav, S.K.; Tyagi, I.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, R.; Ghosh, S.; Das, J.; Jha, G. A Prophage Tail-like Protein Is Deployed by Burkholderia Bacteria to Feed on Fungi. Nat Commun 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.P.; Barber, M.F. Unearthing the Ancient Origins of Antiviral Immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 629–631. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Ryu, S. Spontaneous and Transient Defence against Bacteriophage by Phase-variable Glucosylation of <scp>O</Scp> -antigen in <scp>S</Scp> Almonella Enterica Serovar <scp>T</Scp> Yphimurium. Mol Microbiol 2012, 86, 411–425. [CrossRef]

- Leavitt, J.C.; Woodbury, B.M.; Gilcrease, E.B.; Bridges, C.M.; Teschke, C.M.; Casjens, S.R. Bacteriophage P22 SieA-Mediated Superinfection Exclusion. mBio 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Tock, M.R.; Dryden, D.T. The Biology of Restriction and Anti-Restriction. Curr Opin Microbiol 2005, 8, 466–472. [CrossRef]

- Dy, R.L.; Przybilski, R.; Semeijn, K.; Salmond, G.P.C.; Fineran, P.C. A Widespread Bacteriophage Abortive Infection System Functions through a Type IV Toxin–Antitoxin Mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42, 4590–4605. [CrossRef]

- Swarts, D.C.; Jore, M.M.; Westra, E.R.; Zhu, Y.; Janssen, J.H.; Snijders, A.P.; Wang, Y.; Patel, D.J.; Berenguer, J.; Brouns, S.J.J.; et al. DNA-Guided DNA Interference by a Prokaryotic Argonaute. Nature 2014, 507, 258–261. [CrossRef]

- Kuzmenko, A.; Oguienko, A.; Esyunina, D.; Yudin, D.; Petrova, M.; Kudinova, A.; Maslova, O.; Ninova, M.; Ryazansky, S.; Leach, D.; et al. DNA Targeting and Interference by a Bacterial Argonaute Nuclease. Nature 2020, 587, 632–637. [CrossRef]

- Marraffini, L.A. CRISPR-Cas Immunity in Prokaryotes. Nature 2015, 526, 55–61. [CrossRef]

- Millman, A.; Melamed, S.; Leavitt, A.; Doron, S.; Bernheim, A.; Hör, J.; Garb, J.; Bechon, N.; Brandis, A.; Lopatina, A.; et al. An Expanded Arsenal of Immune Systems That Protect Bacteria from Phages. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 1556-1569.e5. [CrossRef]

- Doron, S.; Melamed, S.; Ofir, G.; Leavitt, A.; Lopatina, A.; Keren, M.; Amitai, G.; Sorek, R. Systematic Discovery of Antiphage Defense Systems in the Microbial Pangenome. Science (1979) 2018, 359. [CrossRef]

- Tsao, Y.F.; Taylor, V.L.; Kala, S.; Bondy-Denomy, J.; Khan, A.N.; Bona, D.; Cattoir, V.; Lory, S.; Davidson, A.R.; Maxwell, K.L. Phage Morons Play an Important Role in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Phenotypes. J Bacteriol 2018, 200. [CrossRef]

- Gentile, G.M.; Wetzel, K.S.; Dedrick, R.M.; Montgomery, M.T.; Garlena, R.A.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Hatfull, G.F. More Evidence of Collusion: A New Prophage-Mediated Viral Defense System Encoded by Mycobacteriophage Sbash. mBio 2019, 10, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Mageeney, C.M.; Mohammed, H.T.; Dies, M.; Anbari, S.; Cudkevich, N.; Chen, Y.; Buceta, J.; Ware, V.C. Mycobacterium Phage Butters-Encoded Proteins Contribute to Host Defense against Viral Attack. mSystems 2020, 5. [CrossRef]

- Mahony, J.; McGrath, S.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; van Sinderen, D. Identification and Characterization of Lactococcal-Prophage-Carried Superinfection Exclusion Genes. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008, 74, 6206–6215. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Bao, M.; Wu, F.; Van Horn, C.; Chen, J.; Deng, X. A Type 3 Prophage of ‘ Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus’ Carrying a Restriction-Modification System. Phytopathology 2018, 108, 454–461. [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, J.; Brancato, C.; Berendzen, K.W.; Dreiseikelmann, B. Development of a Tomato Plant Resistant to Clavibacter Michiganensis Using the Endolysin Gene of Bacteriophage CMP1 as a Transgene. Plant Pathol 2016, 65, 496–502. [CrossRef]

- Kongari, R.R.; Yao, G.W.; Chamakura, K.R.; Kuty Everett, G.F. Complete Genome of Clavibacter Michiganensis Subsp. Sepedonicusis Siphophage CN1A. Genome Announc 2013, 1. [CrossRef]

- Bekircan Eski, D.; Gencer, D.; Darcan, C. Whole-Genome Sequence of a Novel Lytic Bacteriophage Infecting Clavibacter Michiganensis Subsp. Michiganensis from Turkey. Journal of General Virology 2024, 105. [CrossRef]

- Arndt, D.; Grant, J.R.; Marcu, A.; Sajed, T.; Pon, A.; Liang, Y.; Wishart, D.S. PHASTER: A Better, Faster Version of the PHAST Phage Search Tool. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, W16–W21. [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Sun, H.X.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, L.; Peng, Y.; Deng, Z.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Liu, W.; et al. Prophage Hunter: An Integrative Hunting Tool for Active Prophages. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, W74–W80. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Bolduc, B.; Zayed, A.A.; Varsani, A.; Dominguez-Huerta, G.; Delmont, T.O.; Pratama, A.A.; Gazitúa, M.C.; Vik, D.; Sullivan, M.B.; et al. VirSorter2: A Multi-Classifier, Expert-Guided Approach to Detect Diverse DNA and RNA Viruses. Microbiome 2021, 9, 37. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.K.; Bartels, D.; Best, A.A.; DeJongh, M.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Formsma, K.; Gerdes, S.; Glass, E.M.; Kubal, M.; et al. The RAST Server: Rapid Annotations Using Subsystems Technology. BMC Genomics 2008, 9, 75. [CrossRef]

- Besemer, J. GeneMarkS: A Self-Training Method for Prediction of Gene Starts in Microbial Genomes. Implications for Finding Sequence Motifs in Regulatory Regions. Nucleic Acids Res 2001, 29, 2607–2618. [CrossRef]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. EggNOG-Mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zheng, D.; Zhou, S.; Chen, L.; Yang, J. VFDB 2022: A General Classification Scheme for Bacterial Virulence Factors. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, D912–D917. [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Huynh, W.; Chalil, R.; Smith, K.W.; Raphenya, A.R.; Wlodarski, M.A.; Edalatmand, A.; Petkau, A.; Syed, S.A.; Tsang, K.K.; et al. CARD 2023: Expanded Curation, Support for Machine Learning, and Resistome Prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D690–D699. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.H.K.; Bortolaia, V.; Tansirichaiya, S.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Roberts, A.P.; Petersen, T.N. Detection of Mobile Genetic Elements Associated with Antibiotic Resistance in Salmonella Enterica Using a Newly Developed Web Tool: MobileElementFinder. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2021, 76, 101–109. [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, L.; Glover, R.H.; Humphris, S.; Elphinstone, J.G.; Toth, I.K. Genomics and Taxonomy in Diagnostics for Food Security: Soft-Rotting Enterobacterial Plant Pathogens. Analytical Methods 2016, 8, 12–24. [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, C.L.M.; Chooi, Y.-H. Clinker & Clustermap.Js: Automatic Generation of Gene Cluster Comparison Figures. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 2473–2475. [CrossRef]

- Tesson, F.; Hervé, A.; Mordret, E.; Touchon, M.; d’Humières, C.; Cury, J.; Bernheim, A. Systematic and Quantitative View of the Antiviral Arsenal of Prokaryotes. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 2561. [CrossRef]

- López-Leal, G.; Camelo-Valera, L.C.; Hurtado-Ramírez, J.M.; Verleyen, J.; Castillo-Ramírez, S.; Reyes-Muñoz, A. Mining of Thousands of Prokaryotic Genomes Reveals High Abundance of Prophages with a Strictly Narrow Host Range. mSystems 2022, 7. [CrossRef]

- Bobay, L.M.; Touchon, M.; Rocha, E.P.C. Pervasive Domestication of Defective Prophages by Bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 12127–12132. [CrossRef]

- Touchon, M.; Moura de Sousa, J.A.; Rocha, E.P. Embracing the Enemy: The Diversification of Microbial Gene Repertoires by Phage-Mediated Horizontal Gene Transfer. Curr Opin Microbiol 2017, 38, 66–73.

- Gonçalves, O.S.; Souza, F.D.O.; Bruckner, F.P.; Santana, M.F.; Alfenas-Zerbini, P. Widespread Distribution of Prophages Signaling the Potential for Adaptability and Pathogenicity Evolution of Ralstonia Solanacearum Species Complex. Genomics 2021, 113, 992–1000. [CrossRef]

- Christendat, D.; Saridakis, V.; Dharamsi, A.; Bochkarev, A.; Pai, E.F.; Arrowsmith, C.H.; Edwards, A.M. Crystal Structure of DTDP-4-Keto-6-Deoxy-d-Hexulose 3,5-Epimerase FromMethanobacterium Thermoautotrophicum Complexed with DTDP. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275, 24608–24612. [CrossRef]

- Frey, P.A.; Hegeman, A.D. Chemical and Stereochemical Actions of UDP–Galactose 4-Epimerase. Acc Chem Res 2013, 46, 1417–1426. [CrossRef]

- Sivaraman, J.; Sauvé, V.; Matte, A.; Cygler, M. Crystal Structure of Escherichia Coli Glucose-1-Phosphate Thymidylyltransferase (RffH) Complexed with DTTP and Mg2+. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 44214–44219. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rubio, L.; Martínez, B.; Donovan, D.M.; Rodríguez, A.; García, P. Bacteriophage Virion-Associated Peptidoglycan Hydrolases: Potential New Enzybiotics. Crit Rev Microbiol 2013, 39, 427–434. [CrossRef]

- Distler, J.; Mansouri, K.; Mayer, G.; Stockmann, M.; Piepersberg, W. Streptomycin Biosynthesis and Its Regulation in Streptomycetes. Gene 1992, 115, 105–111. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, S.; Kehrenberg, C.; Doublet, B.; Cloeckaert, A. Molecular Basis of Bacterial Resistance to Chloramphenicol and Florfenicol. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2004, 28, 519–542. [CrossRef]

- Beggs, G.A.; Brennan, R.G.; Arshad, M. MarR Family Proteins Are Important Regulators of Clinically Relevant Antibiotic Resistance. Protein Science 2020, 29, 647–653. [CrossRef]

- Zivanovic, Y.; Confalonieri, F.; Ponchon, L.; Lurz, R.; Chami, M.; Flayhan, A.; Renouard, M.; Huet, A.; Decottignies, P.; Davidson, A.R.; et al. Insights into Bacteriophage T5 Structure from Analysis of Its Morphogenesis Genes and Protein Components. J Virol 2014, 88, 1162–1174. [CrossRef]

- Driedonks, R.A.; Caldentey, J.; Klug, A. Gene 20 Product of Bacteriophage T4. J Mol Biol 1983, 166, 341–360. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.C.M. Phage-Encoded Serine Integrases and Other Large Serine Recombinases. Microbiol Spectr 2015, 3. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Wahl, L.M. Quantifying the Forces That Maintain Prophages in Bacterial Genomes. Theor Popul Biol 2020, 133, 168–179. [CrossRef]

- Bacciu, D.; Falchi, G.; Spazziani, A.; Bossi, L.; Marogna, G.; Leori, G.S.; Rubino, S.; Uzzau, S. Transposition of the Heat-Stable Toxin AstA Gene into a Gifsy-2-Related Prophage of Salmonella Enterica Serovar Abortusovis. J Bacteriol 2004, 186, 4568–4574. [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.; Baltimore, D.; Boyer, H.W.; Cohen, S.N.; Davis, R.W.; Hogness, D.S.; Nathans, D.; Roblin, R.; Watson, J.D.; Weissman, S.; et al. Potential Biohazards of Recombinant DNA Molecules. Science (1979) 1974, 185, 303–303. [CrossRef]

- Dedrick, R.M.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Bustamante, C.A.G.; Garlena, R.A.; Mavrich, T.N.; Pope, W.H.; Reyes, J.C.C.; Russell, D.A.; Adair, T.; Alvey, R.; et al. Prophage-Mediated Defence against Viral Attack and Viral Counter-Defence. Nat Microbiol 2017, 2, 16251. [CrossRef]

- Kamruzzaman, M.; Iredell, J. A ParDE-Family Toxin Antitoxin System in Major Resistance Plasmids of Enterobacteriaceae Confers Antibiotic and Heat Tolerance. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 9872. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Tang, K.; Wang, W.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X. Prophage Encoding Toxin/Antitoxin System PfiT/PfiA Inhibits Pf4 Production in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Microb Biotechnol 2020, 13, 1132–1144. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T.; Rezende, R.R. de; Lima, T.T.M.; Souza, F. de O.; Alfenas-Zerbini, P. Genomic Analysis Unveils the Pervasiveness and Diversity of Prophages Infecting Erwinia Species. Pathogens 2022, 12, 44. [CrossRef]

- Greenrod, S.T.E.; Stoycheva, M.; Elphinstone, J.; Friman, V.-P. Global Diversity and Distribution of Prophages Are Lineage-Specific within the Ralstonia Solanacearum Species Complex. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 689. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C.W.; Gloag, E.S.; Lim, C.; Wozniak, D.J.; Cooper, V.S. Rampant Prophage Movement among Transient Competitors Drives Rapid Adaptation during Infection. Sci Adv 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Fong, K.; Lu, Y.T.; Brenner, T.; Falardeau, J.; Wang, S. Prophage Diversity Across Salmonella and Verotoxin-Producing Escherichia Coli in Agricultural Niches of British Columbia, Canada. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, E.; Rocha, E.P.C. Phage-Plasmids Promote Recombination and Emergence of Phages and Plasmids. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 1545. [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, M.; Besoain, X.; Durand, K.; Cesbron, S.; Fuentes, S.; Claverías, F.; Jacques, M.A.; Seeger, M. Clavibacter Michiganensis Subsp. Michiganensis Strains from Central Chile Exhibit Low Genetic Diversity and Sequence Types Match Strains in Other Parts of the World. Plant Pathol 2018, 67, 1944–1954. [CrossRef]

- Canchaya, C.; Fournous, G.; Brüssow, H. The Impact of Prophages on Bacterial Chromosomes. Mol Microbiol 2004, 53, 9–18.

- Grissa, I.; Vergnaud, G.; Pourcel, C. CRISPRcompar: A Website to Compare Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats. Nucleic Acids Res 2008, 36, W145–W148. [CrossRef]

- Georjon, H.; Bernheim, A. The Highly Diverse Antiphage Defence Systems of Bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 686–700. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).