Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain Sources, DNA Isolation, and Genome Sequencing

2.2. Examination of Previously Reported Phytoplasma Genomes

| Phytoplasma | strain | 16SrIII- subgroup | Genome level | Host | location | accession | genome size, kb | Reference |

| Cicuta Witches broom | CicWB | 16SrIII-J | contig (16) | Conium maculatum | Argentina | GCA_035853675.1 | 758 | [38] |

| Phytoplasma Vc33 | Vc33 | 16SrIII-J | contig (36) | Catharanthus roseus | Chile | GCA_001623385.2 | 687 | [40] |

| China tree decline | ChTDIII | 16SrIII-B | contig (67) | Melia azedarach | Argentina | GCA_013391955.1 | 791 | [41] |

| Italian clover phyllody | MA | 16SrIII-B | contig (197) | Catharanthus roseus | Italy | GCA_000300695.1 | 597 | [21] |

| Poinsettia branch-inducing | JR | 16SrIII-A | contig (185) | Euphorbia pulcherrima | USA |

GCA_000309465.1 |

631 | [21] |

| Milkweed Yellows Phytoplasma | MW | 16SrIII-F | contig (158) | Catharanthus roseus | Canada | GCA_000309485 | 584 | [21] |

| Vaccinium Witches’ Broom | VAC | 16SrIII-F | contig (272) | Vaccinium myrtillus | Italy |

GCA_000309405.1 |

648 | [21] |

| ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma pruni’ | PR2021 | 16SrIII-A | chromosome (1) | Euphorbia pulcherrima | Taiwan |

GCA_029746895.1 |

710 | [42] |

| ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma pruni’ | CX | 16SrIII-A | contig (46) | Catharanthus roseus | USA | GCA_001277135.1 | 599 | [43] |

| Milkweed Yellows Phytoplasma | MYp- CanS4 | 16SrIII-F | contig (7) | Asclepias syriaca | Canada | GCA_050286905.1 | 694 | this work |

| ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma pruni’ | 2A1 | 16SrIII-A | contig (2) | lilac | Canada | GCA_033391615.1 | 625 | this work |

2.3. Examination of 16SrIII Genomes for Sequences Related to groEL and groES

2.4. Examination of the Gene Neighborhood of groEL in Group 16SrII and 16SrIII Phytoplasmas

3. Results and Discussion

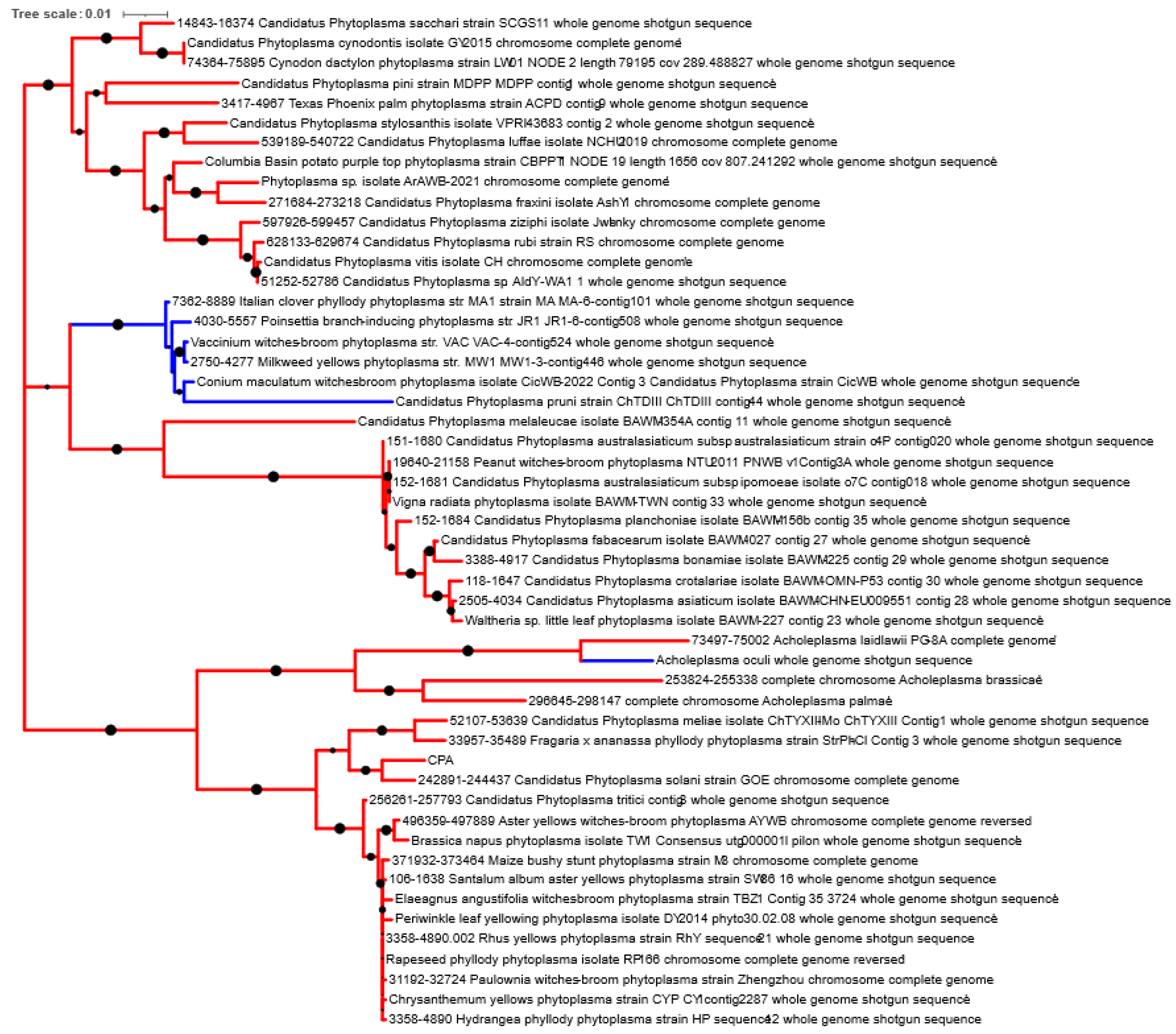

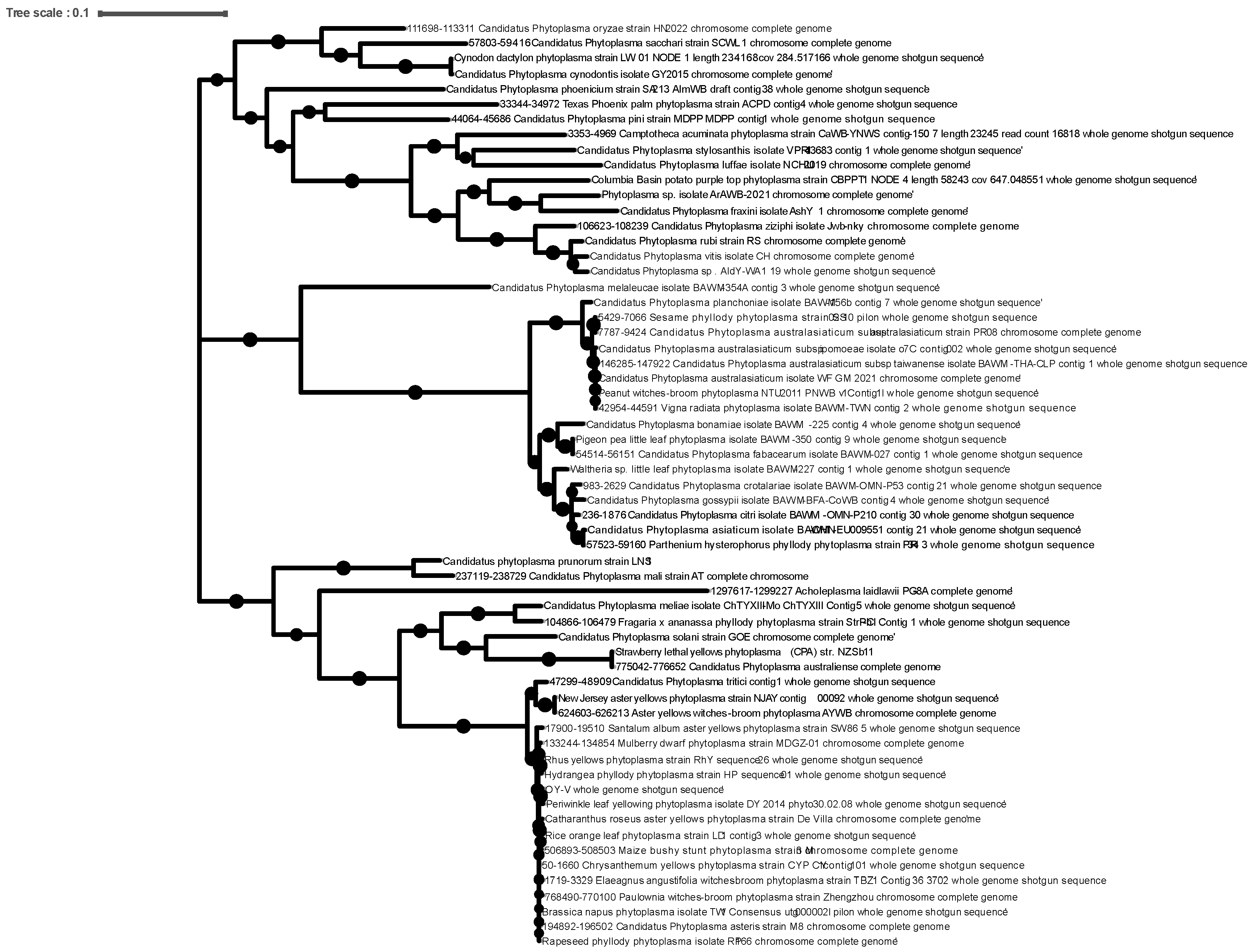

3.1. Genome Sequencing of ‘Ca. P. pruni’ Strains 2A1 and MYp-CanS4

3.2. Examination of Phytoplasma Genomes for GroE Chaperonin System

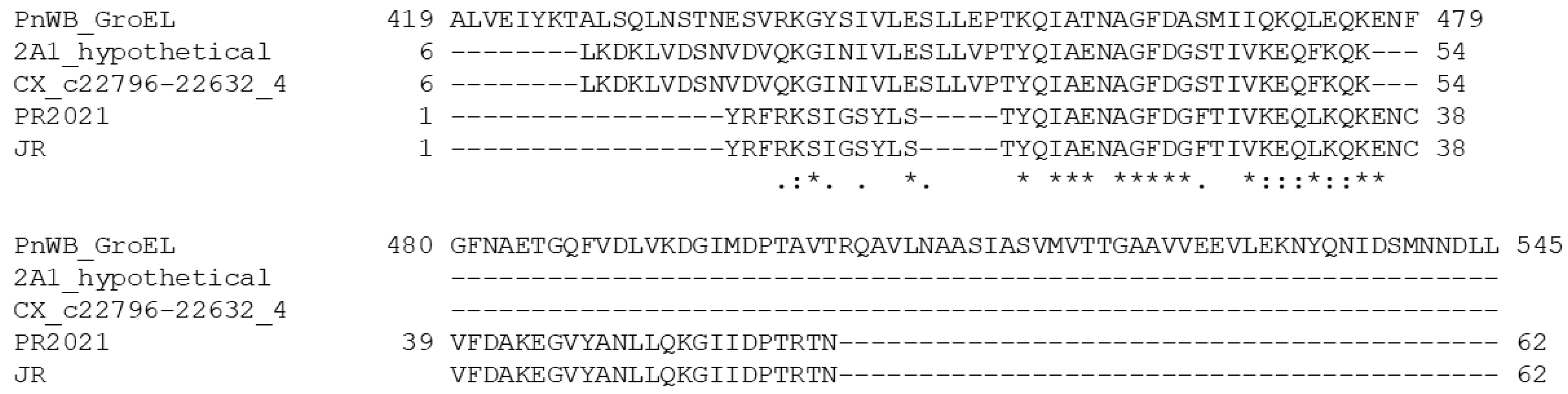

3.3. Pseudogenization of groEL in 16SrIII Phytoplasmas

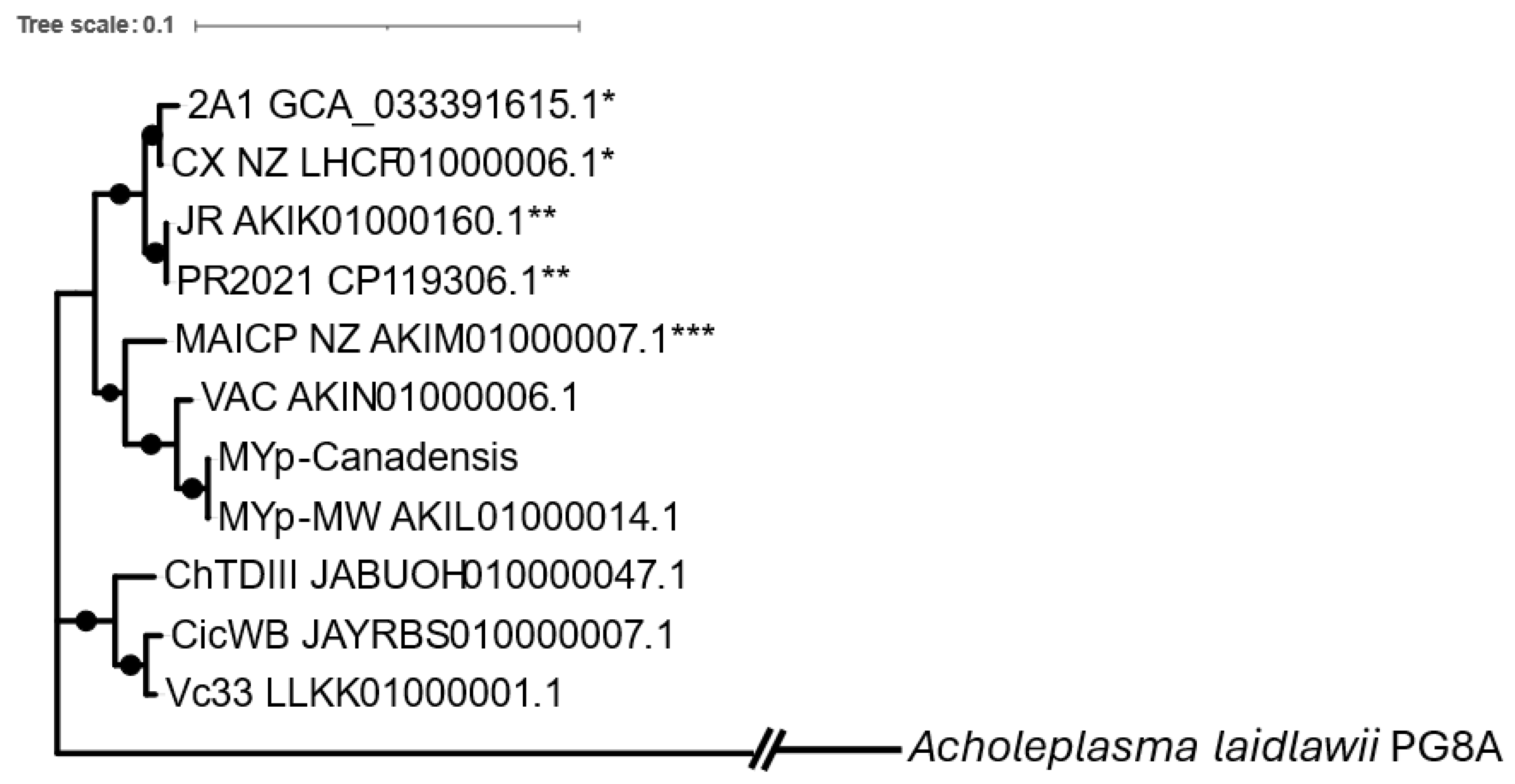

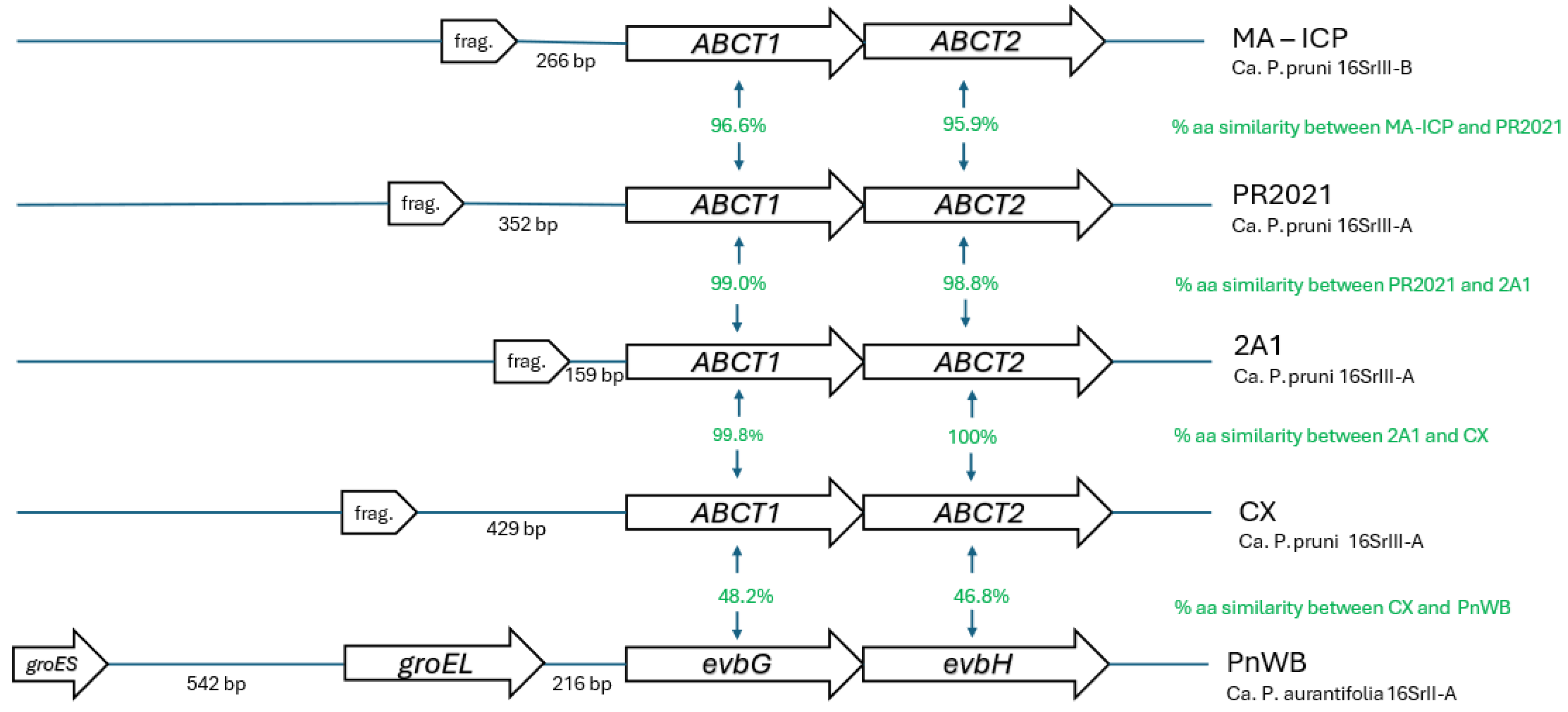

3.4. Conserved Synteny of GroE System in 16SrII and Pseudogenes of 16SrIII

| Phytoplasma | strain | 16SrIII-subgroup | groEL (pseudo)gene length, bp | Amino acids | Coordinates (contig:bases) | evbG ortholog length, bp | Amino acids | Coordinates (contig:bases) | groEL-evbG distance, bp | evbH ortholog length, bp | Amino acids | Coordinates (contig:bases) |

| Cicuta Witches broom | CicWB | 16SrIII-J | none | |||||||||

| Phytoplasma Vc33 | Vc33 | 16SrIII-J | none | |||||||||

| China tree decline | ChTDIII | 16SrIII-B | none | |||||||||

| Italian clover phyllody | MA | 16SrIII-B | 153 | 50 | 33:3851-4003 | 1728 | 576 | 33:1856-3586 | 266 | 1782 | 593 | 33:78-1859 |

| Poinsettia branch-inducing | JR | 16SrIII-A | 186 | 62 | 171:1963-2148 | 17031 | 5661 | 5:13448-15150 | ND1 | 1782 | 593 | 5:11670-13451 |

| Milkweed Yellows | MYp-CanS4 | 16SrIII-F | none | |||||||||

| Vaccinium Witches’ Broom | VAC | 16SrIII-F | none | |||||||||

| ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma pruni’ | PR2021 | 16SrIII-A | 186 | 62 | 686562-686747 | 1728 | 576 | 684481-686211 | 352 | 1782 | 593 | 682703-684484 |

| ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma pruni’ | CX | 16SrIII-A | 165 | 55 | 8:22632-22796 | 1728 | 576 | 8:20474-22204 | 429 | 1782 | 593 | 8:18696-20477 |

| ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma pruni’ | 2A1 | 16SrIII-A | 165 | 55 | 1:56157-56321 | 1728 | 576 | 1:56749-58479 | 159 | 1782 | 593 | 1:58476-60257 |

| Peanut witches' broom phytoplasma | PnWB | 16SrII-A | 1638 | 546 | 9:28499-30136 | 1731 | 577 | 9:26551-28284 | 216 | 1842 | 613 | 9:24713-26554 |

| 1minus strand - contig 5 length is 15150 bp. Therefore, the junction of evbG and groEL pseudogene is disrupted and intergenic distance cannot be calculated | ||||||||||||

3.5. No Evidence of HGT in Non-Fragmented 16SrIII Genomes

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stülke, J.; Eilers, H.; Schmidl, S.R. Mycoplasma and Spiroplasma. In Encyclopedia of Microbiology (Third Edition), Schaechter, M., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2009; pp. 208–219.

- Gasparich, G.E. Spiroplasmas and phytoplasmas: microbes associated with plant hosts. Biologicals 2010, 38, 193–203.

- Kirdat, K.; Tiwarekar, B.; Sathe, S.; Yadav, A. From sequences to species: Charting the phytoplasma classification and taxonomy in the era of taxogenomics. Frontiers in microbiology 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Xiao, J.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, P. Integrated Information for Pathogenicity and Treatment of Spiroplasma. Current Microbiology 2024, 81. [CrossRef]

- Fenta, M.D.; Bazezew, M.; Molla, W.; Kinde, M.Z.; Mengistu, B.A.; Dejene, H. A systematic review and meta-analysis of contagious bovine pleuropneumonia in Ethiopian cattle. Veterinary and Animal Science 2024, 26. [CrossRef]

- Fookes, M.C.; Hadfield, J.; Harris, S.; Parmar, S.; Unemo, M.; Jensen, J.S.; Thomson, N.R. Mycoplasma genitalium: whole genome sequence analysis, recombination and population structure. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 993. [CrossRef]

- Citti, C.; Baranowski, E.; Dordet-Frisoni, E.; Faucher, M.; Nouvel, L.X. Genomic islands in mycoplasmas. Genes 2020, 11, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Bove, J.M. Molecular features of mollicutes. Clin Infect Dis 1993, 17 Suppl 1, S10-31.

- Lund, P.A. Multiple chaperonins in bacteria--why so many? FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 785–800.

- Hemmingsen, S.M.; Woolford, C.; van der Vies, S.M.; Tilly, K.; Dennis, D.T.; Georgopoulos, C.P.; Hendrix, R.W.; Ellis, R.J. Homologous plant and bacterial proteins chaperone oligomeric protein assembly. Nature 1988, 333, 330–334.

- Schwarz, D.; Adato, O.; Horovitz, A.; Unger, R. Comparative genomic analysis of mollicutes with and without a chaperonin system. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0192619. [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.W.; Tillier, E.R.M. Loss and gain of GroEL in the Mollicutes. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 88, 185–194, doi:doi:10.1139/O09-157.

- Henderson, B.; Fares, M.A.; Lund, P.A. Chaperonin 60: a paradoxical, evolutionarily conserved protein family with multiple moonlighting functions. Biological Reviews 2013, 88, 955–987. [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, R.; Yokota, K.; Ayada, K.; Mizuno, M.; Zhao, Y.; Fujinami, Y.; Lin, S.N.; Toyokawa, T.; Okada, H.; Shiratori, Y.; et al. Helicobacter pylori heat-shock protein 60 induces inflammatory responses through the Toll-like receptor-triggered pathway in cultured human gastric epithelial cells. Microbiology 2004, 150, 3913–3922. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, P.S.; Garduno, R.A. Surface-associated heat shock proteins of Legionella pneumophila and Helicobacter pylori: roles in pathogenesis and immunity. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 1999, 7, 58–63.

- Garduno, R.A.; Garduno, E.; Hoffman, P.S. Surface-associated hsp60 chaperonin of Legionella pneumophila mediates invasion in a HeLa cell model. Infect Immun 1998, 66, 4602–4610.

- Watarai, M.; Kim, S.; Erdenebaatar, J.; Makino, S.; Horiuchi, M.; Shirahata, T.; Sakaguchi, S.; Katamine, S. Cellular prion protein promotes Brucella infection into macrophages. J Exp Med 2003, 198, 5–17. [CrossRef]

- Wuppermann, F.N.; Mölleken, K.; Julien, M.; Jantos, C.A.; Hegemann, J.H. Chlamydia pneumoniae GroEL1 protein is cell surface associated and required for infection of HEp-2 cells. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 3757–3767. [CrossRef]

- Hickey, T.B.M.; Thorson, L.M.; Speert, D.P.; Daffé, M.; Stokes, R.W. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Cpn60.2 and DnaK are located on the bacterial surface, where Cpn60.2 facilitates efficient bacterial association with macrophages. Infect Immun 2009, 77, 3389–3401. [CrossRef]

- Bertaccini, A. Plants and Phytoplasmas: When Bacteria Modify Plants. 2022, 11, 1425.

- Saccardo, F.; Martini, M.; Palmano, S.; Ermacora, P.; Scortichini, M.; Loi, N.; Firrao, G. Genome drafts of four phytoplasma strains of the ribosomal group 16SrIII. Microbiology 2012, 158, 2805–2814. [CrossRef]

- Nijo, T.; Iwabuchi, N.; Tokuda, R.; Suzuki, T.; Matsumoto, O.; Miyazaki, A.; Maejima, K.; Oshima, K.; Namba, S.; Yamaji, Y. Enrichment of phytoplasma genome DNA through a methyl-CpG binding domain-mediated method for efficient genome sequencing. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2021, 87, 154–163. [CrossRef]

- Bennypaul, H.; Sanderson, D.; Donaghy, P.; Abdullahi, I. Development of a Real-Time PCR Assay for the Detection and Identification of Rubus Stunt Phytoplasma in Rubus spp. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 2296–2306. [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, D.E.; Lee, I.M. Ultrasensitive detection of phytoplasmas by nested-PCR assays using two universal primer pairs. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 1996, 35, 144–151.

- Smart, C.D.; Schneider, B.; Blomquist, C.L.; Guerra, L.J.; Harrison, N.A.; Ahrens, U.; Lorenz, K.H.; Seemuller, E.; Kirkpatrick, B.C. Phytoplasma-specific PCR primers based on sequences of the 16S-23S rRNA spacer region. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 2988–2993.

- Zhao, Y.; Wei, W.; Lee, I.M.; Shao, J.; Suo, X.; Davis, R.E. The iPhyClassifier, an interactive online tool for phytoplasma classification and taxonomic assignment. Methods Mol Biol 2013, 938, 329–338. [CrossRef]

- Town, J.R.; Wist, T.; Perez-Lopez, E.; Olivier, C.Y.; Dumonceaux, T.J. Genome sequence of a plant-pathogenic bacterium, “Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris” strain TW1. Microbiology Resource Announcements 2018, 7. [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Meth. 2012, 9, 357–359.

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 589–595. [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLOS Computational Biology 2017, 13, e1005595. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Gao, S.; Xiao, B.; He, Z.; Hu, S. Plasmer: an Accurate and Sensitive Bacterial Plasmid Prediction Tool Based on Machine Learning of Shared k-mers and Genomic Features. Microbiology spectrum 2023, 11, e04645-04622, doi:doi:10.1128/spectrum.04645-22.

- Manni, M.; Berkeley, M.R.; Seppey, M.; Simão, F.A.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO Update: Novel and Streamlined Workflows along with Broader and Deeper Phylogenetic Coverage for Scoring of Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral Genomes. Molec. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 4647–4654. [CrossRef]

- Schwengers, O.; Jelonek, L.; Dieckmann, M.A.; Beyvers, S.; Blom, J.; Goesmann, A. Bakta: rapid and standardized annotation of bacterial genomes via alignment-free sequence identification. Microb Genom 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Tatusova, T.; DiCuccio, M.; Badretdin, A.; Chetvernin, V.; Nawrocki, E.P.; Zaslavsky, L.; Lomsadze, A.; Pruitt, K.D.; Borodovsky, M.; Ostell, J. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, 6614–6624. [CrossRef]

- Rotmistrovsky, K.; Agarwala, R. BMTagger: Best Match Tagger for Removing Human Reads from Metagenomics Datasets 2011.

- Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, F.D.; Guzmán, F.A.; Conci, L.R. Draft genome sequence of Cicuta witches' broom phytoplasma, subgroup 16SrIII-J: a subgroup with phytopathological relevance in South America. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2024, 49, 558–565. [CrossRef]

- Pusz-Bochenska, K.; Perez-Lopez, E.; Wist, T.J.; Bennypaul, H.; Sanderson, D.; Green, M.; Dumonceaux, T.J. Multilocus sequence typing of diverse phytoplasmas using hybridization probe-based sequence capture provides high resolution strain differentiation. Frontiers in microbiology 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Zamorano, A.; Fiore, N. Draft Genome Sequence of 16SrIII-J Phytoplasma, a Plant Pathogenic Bacterium with a Broad Spectrum of Hosts. Genome Announc 2016, 4. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, F.D.; Zübert, C.; Huettel, B.; Kube, M.; Conci, L.R. Draft Genome Sequence of Candidatus Phytoplasma pruni (X-Disease Group, Subgroup 16SrIII-B) Strain ChTDIII from Argentina. Microbiology Resource Announcements 2020, 9, 10.1128/mra.00792-00720, doi:doi:10.1128/mra.00792-20.

- Pei, S.-C.; Chen, A.-P.; Chou, S.-J.; Hung, T.-H.; Kuo, C.-H. Complete genome sequence of Candidatus Phytoplasma pruni PR2021, an uncultivated bacterium associated with poinsettia (Euphorbia pulcherrima). Microbiology Resource Announcements 2023, 12, e00443-00423, doi:doi:10.1128/MRA.00443-23.

- Lee, I.M.; Shao, J.; Bottner-Parker, K.D.; Gundersen-Rindal, D.E.; Zhao, Y.; Davis, R.E. Draft Genome Sequence of "Candidatus Phytoplasma pruni" Strain CX, a Plant-Pathogenic Bacterium. Genome Announc 2015, 3. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhao, Y. Phytoplasma taxonomy: nomenclature, classification, and identification. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Jomantiene, R.; Davis, R.E.; Valiunas, D.; Alminaite, A. New group 16SrIII phytoplasma lineages in Lithuania exhibit rRNA interoperon sequence heterogeneity. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2002, 108, 507–517. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, H.M.; Gundersen, D.E.; Sinclair, W.A.; Lee, I.M.; Davis, R.E. Mycoplasmalike organisms from milkweed, goldenrod, and spirea represent two new 16S rRNA subgroups and three new strain subclusters related to peach X-disease MLOs. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 1994, 16, 255–260. [CrossRef]

- Valiunas, D.; Samuitiene, M.; Rasomavicius, V.; Navalinskiene, M.; Staniulis, J.; Davis, R.E. Subgroup 16SrIII-F phytoplasma strains in an invasive plant, Heracleum sosnowskyi, and an ornamental, Dictamnus albus. J. Plant Pathol. 2007, 89, 137–140.

- Chung, W.-C.; Chen, L.-L.; Lo, W.-S.; Lin, C.-P.; Kuo, C.-H. Comparative Analysis of the Peanut Witches'-Broom Phytoplasma Genome Reveals Horizontal Transfer of Potential Mobile Units and Effectors. PLoS One 2013, 8, e62770. [CrossRef]

- Mitrović, J.; Smiljković, M.; Seemüller, E.; Reinhardt, R.; Hüttel, B.; Büttner, C.; Bertaccini, A.; Kube, M.; Duduk, B. Differentiation of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma cynodontis’ Based on 16S rRNA and groEL Genes and Identification of a New Subgroup, 16SrXIV-C. Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 1578–1583. [CrossRef]

- Contaldo, N.; Mejia, J.F.; Paltrinieri, S.; Calari, A.; Bertaccini, A. Identification and GroEL gene characterization of green petal phytoplasma infecting strawberry in Italy. Phytopathogenic Mollicutes 2012, 2, 59–62. [CrossRef]

- Mitrović, J.; Kakizawa, S.; Duduk, B.; Oshima, K.; Namba, S.; Bertaccini, A. The groEL gene as an additional marker for finer differentiation of 'Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris'-related strains. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2011, 159, 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Muirhead, K.; Pérez-López, E.; Bahder, B.W.; Hill, J.E.; Dumonceaux, T. The CpnClassiPhyR is a resource for cpn60 universal target-based classification of phytoplasmas. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 2494–2497. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molec. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 2021, 49, W293-W296. [CrossRef]

- Dainat, J.; Pontarotti, P. Methods to Identify and Study the Evolution of Pseudogenes Using a Phylogenetic Approach. Methods Mol Biol 2021, 2324, 21–34. [CrossRef]

- Cehovin, A.; Coates, A.R.M.; Hu, Y.; Riffo-Vasquez, Y.; Tormay, P.; Botanch, C.; Altare, F.; Henderson, B. Comparison of the moonlighting actions of the two highly homologous chaperonin 60 proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun 2010, 78, 3196–3206. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xia, Y.; Cui, J.; Gu, Z.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y.Q.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. The Roles of Moonlighting Proteins in Bacteria. Current issues in molecular biology 2014, 16, 15–22.

- Oshima, K.; Maejima, K.; Namba, S. Genomic and evolutionary aspects of phytoplasmas. Frontiers in microbiology 2013, 4, 230. [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Zhang, J.; Ewing, A.; Miller, S.A.; Jancso Radek, A.; Shevchenko, D.V.; Tsukerman, K.; Walunas, T.; Lapidus, A.; Campbell, J.W.; et al. Living with genome instability: the adaptation of phytoplasmas to diverse environments of their insect and plant hosts. J Bacteriol 2006, 188, 3682–3696. [CrossRef]

- Zuckerkandl, E.; Pauling, L. Evolutionary Divergence and Convergence in Proteins. In Evolving Genes and Proteins, Bryson, V., Vogel, H.J., Eds.; Academic Press: 1965; pp. 97–166.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).