1. Introduction

Climate change represents one of the greatest economic and environmental challenges facing humanity today. The growing accumulation of greenhouse gases since the Industrial Revolution has led to a global warming of approximately 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, with multiple consequences for natural and economic systems (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2019; IPCC, 2021). These impacts manifest through disruptions in agricultural productivity, infrastructure, public health, and ecosystems, thereby generating significant economic costs (Stern, 2007; Diep et al., 2025). This situation has prompted the international community to adopt instruments such as the Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2015) and the Paris Agreement (UNFCCC, 2015), which aim to limit the rise in global temperatures to below 2 °C by the end of the century. However, developing countries, particularly in Africa, remain especially vulnerable due to their high dependence on agriculture, limited adaptive capacities, and scarce financial resources (Hallegatte & Rozenberg, 2017).

In this context, Africa emerges as a continent at high climatic risk, where variations in temperature and precipitation directly affect economic growth and social well-being. Evidence from recent studies shows that even modest increases in temperature result in substantial growth losses in Sub-Saharan Africa (Burke et al., 2015; Omotoso et al., 2023), while poorer countries are the most vulnerable to climate shocks (Dell et al., 2012; Barbier & Hochard, 2018). In particular, the costs associated with droughts, floods, and rainfall variability have significant repercussions on agricultural yields, food prices, and macroeconomic stability (Alagidede et al., 2016; Ayele & Fisseha, 2024). Moreover, several studies highlight that Central Africa, including Cameroon, constitutes a climatic “hotspot,” where the intensification of extreme events is already evident and producing severe consequences (Tsalefac et al., 2015; Serdeczny et al., 2017; Atwoli et al., 2023).

Cameroon, due to its ecological diversity and its economic significance in Central Africa, represents a particularly relevant case study. The country exhibits a strong dependence on agriculture, which contributes more than 20% of GDP and employs over 60% of the labor force, alongside an emerging industrial sector that remains highly vulnerable to energy and water disruptions (Molua, 2007; Tingem et al., 2008; Mbuli et al., 2021). Furthermore, climate shocks directly affect key sectors such as housing, health, and infrastructure, thereby exacerbating inequality and poverty (Bele et al., 2013; Chabejong, 2016; Safougne Djomekui et al., 2025). Projections indicate that, without adequate adaptation measures, Cameroon could experience a substantial decline in agricultural and forestry productivity, with cascading effects on food security and public revenues (Tamoffo et al., 2023; Molua et al., 2025). Consequently, understanding the magnitude of the economic costs of climate change in Cameroon is of strategic importance, both for guiding national policy and for mobilizing international financing within the framework of the Green Climate Fund.

The academic literature has extensively documented the economic impacts of climate change in Africa, yet it remains largely dominated by regional-level analyses. Pioneering studies such as those by Abidoye and Odusola (2015) and Alagidede et al. (2016) have shown that climatic variations significantly reduce economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. However, these studies often focus on agriculture or rely on multi-country samples, thus limiting the ability to assess country-specific costs. Regarding Cameroon, existing research has primarily examined the microeconomic impacts of climate change, particularly on food and cash crops (Molua, 2007; Tingem et al., 2008; Bele et al., 2013; Gérardeaux et al., 2013). These studies have demonstrated the vulnerability of rural households but provide limited insights into the broader macroeconomic and sectoral effects. Moreover, very few studies in Cameroon have attempted to translate climate impacts into monetary or economic cost terms—an essential dimension for informing policymakers and justifying financing needs. Most analyses are confined to estimating coefficients linking climate variables to agricultural yields, without providing quantified assessments of GDP or sectoral value-added losses (Chamma, 2024). Another major limitation concerns the lack of detailed projections incorporating IPCC climate scenarios (SSP and RCP), which could otherwise enable simulations of future cost trajectories. This gap contrasts with experiences from countries such as Senegal (Sultan et al., 2014) and South Africa (Ngepah et al., 2022), where forward-looking assessments are already being integrated into national adaptation strategies.

The originality of this study lies in its ambition to fill these gaps through a contribution built around four key dimensions. First, it uses macroeconomic data to position itself among the first studies to provide empirical evidence on the relationship between climate change and economic growth in Cameroon, while estimating the associated monetary costs. Second, this paper distinguishes itself from existing research by evaluating the economic losses linked to the impact of climate change on sectoral productivity, encompassing the industrial and manufacturing sector, the services sector, and the agricultural sector. Third, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to project the future impact of climate change on growth deviations in Cameroon. Fourth, we conduct a basic comparative analysis of the nonlinear impact of temperature and precipitation variations on economic growth between Cameroon and other African countries.

The remainder of the paper is organized into four sections.

Section 2 provides a brief review of the relevant literature and highlights the existing research gaps.

Section 3 outlines the methodological framework of the study, while

Section 4 presents and discusses the empirical results. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the study and discusses key policy implications.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundations

The relationship between climate change and economic growth is grounded in a theoretical framework that integrates environmental economics, welfare theory, and development economics. Since the pioneering works of Nordhaus (1991) with the DICE model and Stern (2007) in his seminal report, the literature has emphasized that climate change represents a global negative externality capable of eroding natural capital and directly affecting agricultural, industrial, and service production. These analyses are rooted in the theory of externalities (Pigou, 1920), which posits that the negative effects of production on the environment must be internalized into economic costs to guide policy and market decisions. The underlying theoretical idea is that climate, as an implicit productive factor, influences macroeconomic production functions, and that a climate shock can be interpreted as a loss of productive capital or a decline in productivity (Dell et al., 2012; Burke et al., 2015).

In this regard, endogenous growth theory (Romer, 1986) provides a framework for understanding how climate change affects the fundamental drivers of growth, particularly the accumulation of physical, human, and technological capital. Recurrent climate shocks reduce incentives to invest in infrastructure and constrain human capital accumulation through impacts on health and education. Hallegatte and Rozenberg (2017) show that poverty and inequality increase vulnerability to climate impacts, aligning with Tol’s (2009) analyses, which demonstrate that the costs of climate change are distributed asymmetrically, with particularly severe effects on developing countries. This underscores the need for macroeconomic assessments of climate impacts to go beyond mere sectoral effects and consider the economy as a whole.

However, several theoretical frameworks explain that the impacts of climate shocks are not uniform but operate through specific transmission mechanisms. For instance, the natural disaster approach conceptualizes extreme climatic events as “exogenous shocks” to production (Barro, 2009), affecting total factor productivity. Similarly, economic resilience theory (Rose, 2007) suggests that economies can partially offset losses through adaptation mechanisms, though impacts remain substantial over the long term. Dependence on climate-sensitive sectors, particularly agriculture and forestry, further amplifies economic vulnerability (Collier et al., 2008). This theoretical framework thus justifies the sectoral disaggregation of the analysis, highlighting the differentiated contributions of the agricultural, industrial, and service sectors to overall economic losses.

Moreover, climate stability constitutes a global public good that is non-excludable and non-rivalrous (Kaul et al., 1999), and national climate policies operate within a framework of international cooperation, where the Paris Agreement (UNFCCC, 2015) and successive COPs (notably COP21, COP26, and COP28) have reaffirmed the need for coordinated actions and financial mechanisms to support adaptation in vulnerable countries. The economic costs of climate change thus serve as a central policy tool, enabling the quantification of financing needs and negotiations on compensation. Studies by Fankhauser (2013) and more recently Stern (2015) highlight that quantitative assessments of climate-related economic losses strengthen the credibility of developing countries’ advocacy in mobilizing climate funds, particularly through the Green Climate Fund. In this regard, the political economy of climate change (Keohane & Victor, 2016) emphasizes the role of quantified estimates in structuring international debates on adaptation financing.

From a dynamic perspective, Arrow et al. (2012) incorporate an intergenerational dimension, stressing “inclusive sustainability” to underscore that today’s climate losses compromise future development trajectories, especially in middle-income countries such as Cameroon. Within this framework, forward-looking models using IPCC scenarios (SSP and RCP) link long-term growth theory with climate projections (IPCC, 2021). Theoretical analyses by Burke et al. (2018) reinforce this approach by showing that even modest temperature deviations can lead to substantial cumulative growth declines, thereby amplifying income disparities between countries.

2.2. Is Cameroon More Vulnerable to Climate Change?

Cameroon is the main economic hub of Central Africa, with an economy dominated by the tertiary sector and agro-industrial activities, where agriculture, livestock, and fishing employ over 70% of the total labor force. Geographically, the country comprises 10 regions with diverse climatic characteristics grouped into five agroecological zones

1.

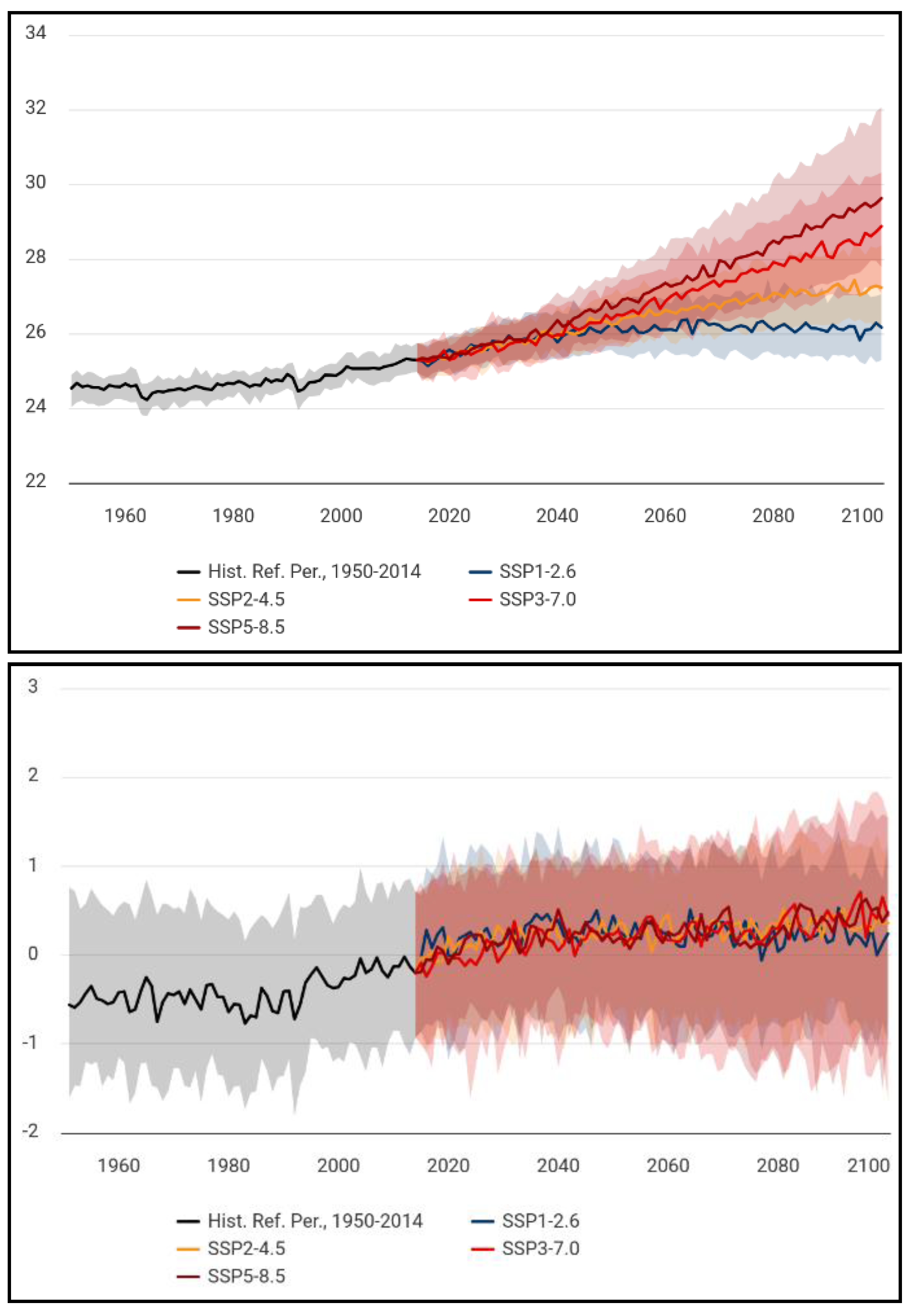

Figure 1 presents the historical evolution and projections of mean surface air temperatures in Cameroon, along with precipitation levels measured by the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), up to the end of the century based on the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP) from the CMIP6 project. The left-hand panel shows that, over the historical period, the average temperature in Cameroon increased modestly, from 24.53 °C in 1950 to 25.29 °C in 2014. According to the scenarios, the mean temperature is projected to reach 26.23 °C by 2050 and 27.23 °C by 2100 under the intermediate scenario (SSP2-4.5), whereas it would rise dramatically under the pessimistic scenario (SSP5-8.5), reaching 26.67 °C in 2050 and 29.62 °C in 2100.

Notes: The uncertainty bands represent the 10th–90th percentiles.

Source: Authors, based on data from the World Bank (Climate Change Knowledge Portal).

Regarding precipitation, the left-hand graph depicts the historical evolution and projections of the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI). The historical period shows relatively moderate variability, with fluctuations between rainfall surpluses and deficits but no clear trend toward prolonged droughts. However, from 2015 onward, projections from the various SSP scenarios reveal greater uncertainty in future precipitation patterns. Under the SSP1-2.6 scenario, which assumes ambitious climate policies, the SPI remains generally close to the historical mean, with moderate variations. In contrast, under the SSP2-4.5 and SSP3-7.0 scenarios, precipitation variability increases. The SPI becomes more unstable, reflecting a more pronounced alternation between droughts and rainfall surpluses, indicating for Cameroon an elevated risk of agricultural losses, disruptions to water and energy infrastructure, and increased volatility in rural incomes (Amougou, 2018; Bomdzele Jr & Molua, 2023). Under the most pessimistic scenario, SSP5-8.5, the spread of projections is the highest, suggesting more frequent and intense extreme climatic events.

Figure 2.

Comparative levels of vulnerability and adaptive capacity between Cameroon and selected African countries (average for 2000–2020).

Figure 2.

Comparative levels of vulnerability and adaptive capacity between Cameroon and selected African countries (average for 2000–2020).

Source: Authors, based on data from the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN)

2.

In

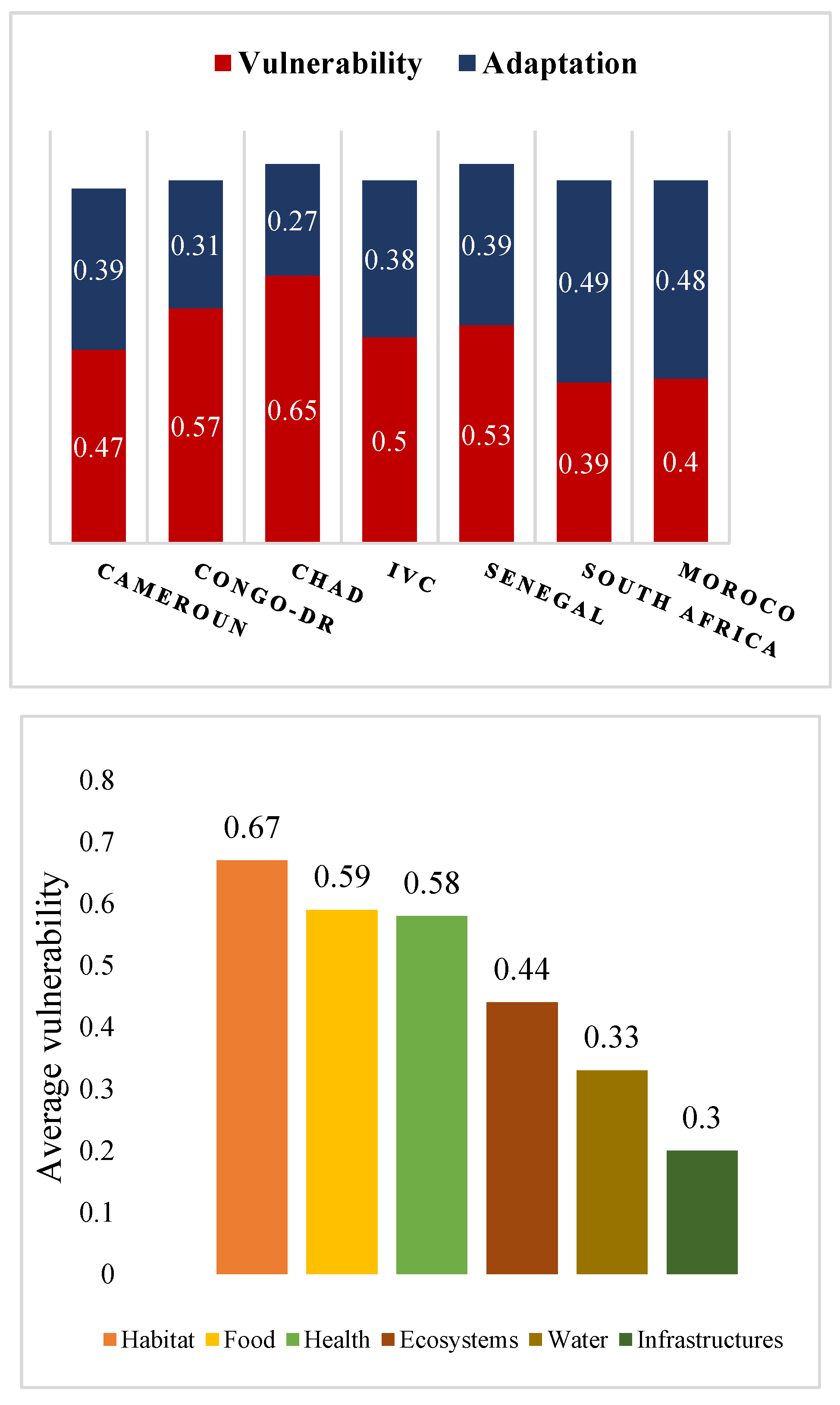

Figure 2, the left panel presents a comparative analysis of vulnerability and adaptive capacity to climate change between Cameroon and several African countries. We find that, compared to other Central African countries such as the Republic of Congo and Chad, Cameroon exhibits relatively acceptable climate performance, characterized by a vulnerability index below the average (0.47/1), but with still low adaptive capacity (0.39). Similarly, Cameroon remains less vulnerable than some West African countries, such as Senegal, which has a relatively high vulnerability level of 0.53, although both countries have comparable adaptive capacities. However, Cameroon is still considerably more vulnerable than countries like South Africa (vulnerability = 0.39) and Morocco in North Africa (vulnerability = 0.4), which demonstrate better performance, likely due to the multiple strategies implemented to mitigate the effects of climate change, such as the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (NCCAS) in South Africa. Cameroon has also adopted several initiatives, including the National Climate Change Adaptation Plan (PNACC), but these efforts remain insufficient in light of the scale of the challenges (Chikowore et al., 2025).

The sectoral analysis presented in the right panel of

Figure 2 shows that the housing and food/agriculture sectors are the most vulnerable in Cameroon, compared to the water and infrastructure sectors, which are more resilient. The vulnerability of the housing sector is linked to precarious urbanization, characterized by settlements in marshy and geographically risky areas, as well as poor-quality construction materials (Safougne Djomekui et al., 2025). Furthermore, the intensification of localized droughts, floods, and irregular rainfall directly affects agricultural yields, explaining the high vulnerability of this sector to climate change (Molua, 2007). Added to these factors are weak irrigation and storage systems, which prevent effective water management and agricultural product preservation, exposing farmers to crop losses (Awazi, 2022).

2.3. Selective Review of Empirical Studies and Literature Gaps

There is broad consensus in the literature that climate change exerts negative effects on overall economic output. In Africa, Baarsh et al. (2020) recently showed that rising temperatures and precipitation variability led to a 10–15% loss in GDP between 1980 and 2014. Similarly, Abidoye and Odusola (2015) found, using a sample of 34 African countries, that a 1 °C increase reduces GDP growth by 0.67 percentage points. These results highlight the particularly pronounced vulnerability of low-income countries, as noted by Stern (2013), who observes that the effects of climate change on growth are disproportionately distributed according to the level of development.

To better understand the causal chain between climatic phenomena and economic performance, studies such as Hsiang (2016) and Auffhammer (2022) have revealed that climatic factors—including temperature, wind speed, and precipitation—have direct impacts on a wide range of economic outcomes, including agricultural yields, industrial output, and labor productivity. In comparison with developed countries, Hsiang et al. (2017) provided robust empirical estimates of the economic damages of climate change in the United States, combining econometric analyses with sectoral process models (agriculture, mortality, energy, labor, crime, coastal zones). They found that a 1 °C increase in global temperature generates a loss of approximately 1.2% of U.S. GDP.

Regarding long-term effects and projection analyses, Liu and Raftery (2021) estimate that average temperatures could increase by 2.1 °C to 3.9 °C by 2100, potentially leading to income losses of up to 23% of global GDP. More targeted studies, such as Burke et al. (2018), show that limiting warming to 1.5 °C rather than 2 °C significantly reduces economic damages. Furthermore, Kompas et al. (2018) emphasize that beyond 2 °C, the impacts on growth become markedly more severe in the long term, particularly in developing economies. These global projections are complemented by more localized analyses. For example, Feliciano et al. (2022) examined the cotton trade and found that a 0.3 °C increase could reduce trade flows by 25% over the next decade in Ethiopia. Regional models confirm that developing African countries will bear the heaviest burden of climate change. Defrance et al. (2020), using a set of simulation models applied to the Sahel, show that projected agricultural productivity losses could reduce regional GDP by 2% to 4% by 2050 under the pessimistic scenario. Their approach relies on climate data projected by the IPCC and agronomic models coupled with economic growth equations, confirming that future rainfall variability is a central determinant of expected losses.

Similarly, Seo and Mendelsohn (2008), through microeconomic modeling across 11 African countries, estimate that climate-related agricultural income losses could account for up to 25% of total agricultural income by 2080, with significant heterogeneity across regions, West and Southern Africa being the most vulnerable. Arndt et al. (2011), simulating the effects of climate change in Mozambique using a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model, find that the country’s GDP could be 4% to 12% lower in 2050 compared to a no-climate-change scenario.

Although the literature on the economic impacts of climate change in Africa is relatively extensive and expanding (Abidoye & Odusola, 2015; Alagidede et al., 2016; Zhao & Liu, 2023; Chamma, 2024), significant gaps remain, particularly regarding the case of Cameroon. Even within Cameroon, while numerous studies have focused on microeconomic analyses assessing the influence of temperature and precipitation variations on agricultural production, well-being, and ecosystems (Molua, 2007; Tingem et al., 2008; Bele et al., 2013; Bomdzele & Molua, 2023), to the best of our knowledge, no study has provided empirical evidence on overall economic growth, either in the short or long term. Knowledge of this relationship would, for example, help better assess the economic costs generated by climate shocks on the overall economy, thereby informing not only targeted and quantified policies but also a more accurate evaluation of the country’s vulnerability relative to the international context and in relation to support organizations and adaptation funding.

Furthermore, there is an inherent lack of knowledge regarding the magnitude of climate change impacts on sectoral productivity across the economy, including the industrial and manufacturing sector, the agriculture and forestry sector, and the services and trade sector. The only study approaching this issue is Chamma (2024). However, this study is limited, not only because it focuses on a set of Sub-Saharan African countries, but also because it provides only estimated coefficients of climatic variables on different sectoral growth rates without translating them into monetary economic costs. Such an approach would allow for the identification of the most vulnerable sectors requiring priority action.

Moreover, the literature is largely silent on projected alerts and impacts of climate change on Cameroon’s economy. Yet, this issue is being addressed in some African countries, such as Senegal (Sultan et al., 2014) and South Africa (Ngepah et al., 2022). This study therefore aims to fill these gaps using a twofold approach: first, by assessing the economic costs associated with the impact of climate change on overall and sectoral production based on data from 1980 to 2022; and second, by conducting simulations of potential future costs of climate change using projections under different emission scenarios.

3. Methodological Framework

To achieve the objectives of this study, we employ a twofold methodology. The first focuses on assessing the historical impact of climate change on both overall and sectoral output, as well as the resulting economic costs. The second involves projecting potential future losses that climate change may impose on Cameroon’s economic growth.

3.1. Assessment of Historical Losses

We use annual macroeconomic data for Cameroon over a 43-year period (1980–2022) to analyze the economic costs resulting from the impact of climate change on overall output, measured by annual GDP, as well as on different productive sectors, namely: (i) agricultural value added (AVA), (ii) manufacturing value added (MVA), and (iii) services value added (SVA). Output data and its subcomponents are sourced from the World Bank. Climate change data (temperature and precipitation) are extracted from the Climate Change Knowledge Portal (CCKP). These data primarily include annual mean temperature variations, precipitation changes, and the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), following methodologies from Abidoye and Odusola (2015); Kumar et al. (2021); Gloy et al. (2023); Zehraoui et al. (2024); and Su et al. (2024).

Table A1 in the appendix presents the variables and their sources.

The study first adopts a non-parametric approach based on a mean comparison test to analyze the economic losses induced by the impact of climate change. Specifically, temperature and precipitation shock indicators are constructed as dichotomous variables, considering a climate shock to occur when the temperature or precipitation level in a given year deviates by more than one standard deviation from the mean over the observed period. Thus, the climate shock variable (temperature or precipitation) takes the value of 1 for years in which a significant deviation from the mean is observed, and 0 otherwise.

This methodology aligns with studies that assess climate change effects based on the standard deviation of annual observed temperature and precipitation levels (Warnatzsch & Reay, 2019; Raubenheimer & Phiri, 2023; Chamma, 2024; Ateba Boyomo, 2025). The economic costs induced by temperature and precipitation changes are then obtained using a mean comparison test, which evaluates the statistical difference in output associated with the presence or absence of climate shocks. The general model for the independent-samples Student’s t-test is expressed as follows:

where

is the mean output for years in which a climate shock is present (

) ;

is the mean output for years in which no climate shock occurs (

) ;

and

are the output variances within each group, and

and

are the sample sizes for each group. By virtue of the central limit theorem, this test is particularly efficient with small sample sizes, with unequal group variances, and even when the data are not perfectly normally distributed (Gujarati & Porter, 2009).

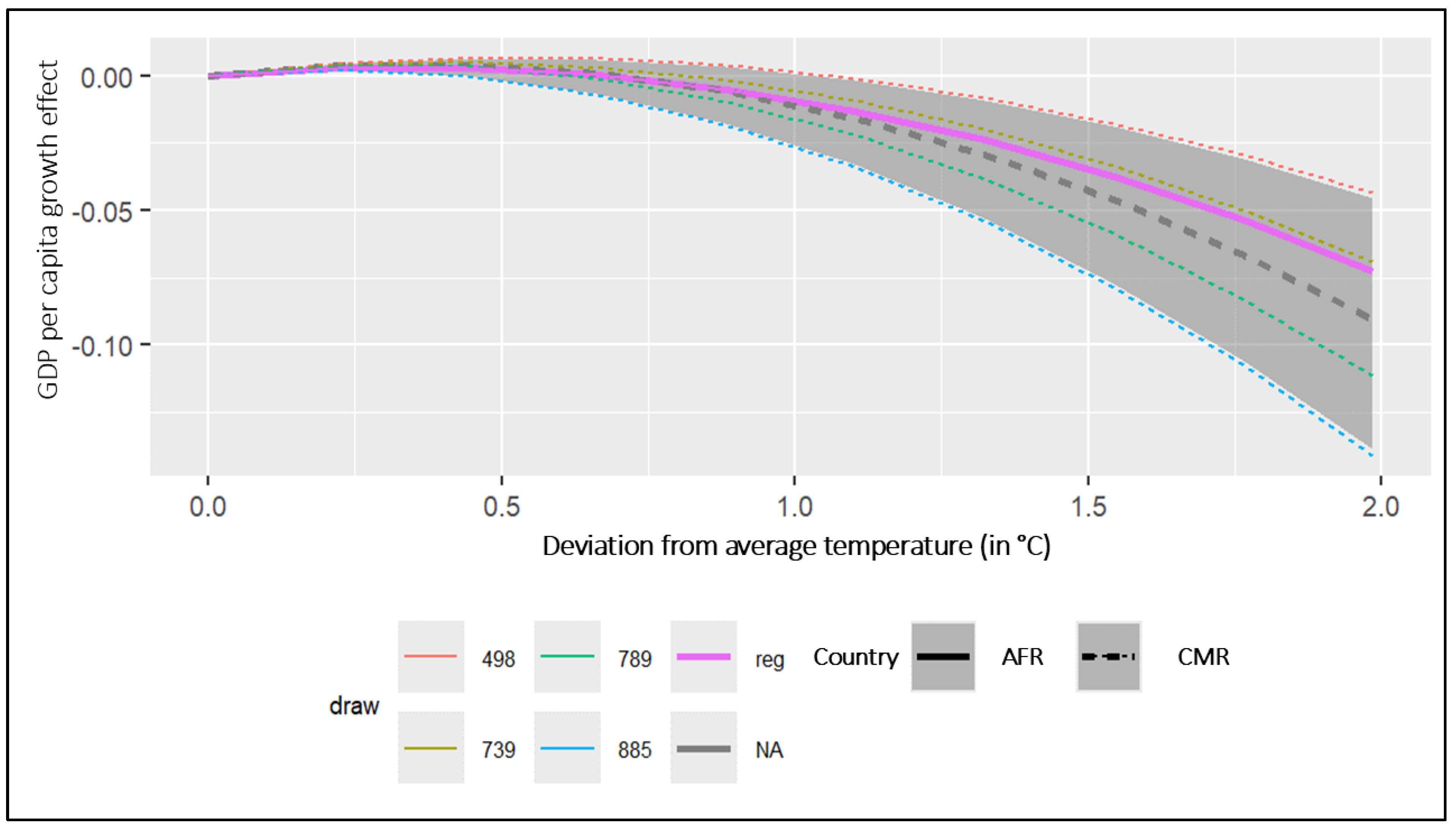

However, this approach may have some limitations, including the risk of omitted variable bias due to the exclusion of control variables, the neglect of temporal dynamics that are common in time-series studies on GDP, and the lack of assurance regarding causal relationships. To address these limitations, we employ a Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model, introduced by Sims (1980), to derive impulse response functions. The control variables considered include arable land area, government size, foreign direct investment, natural resource rents, and secondary school enrollment rates. Moreover, for robustness analyses, we assess the impact of temperature and precipitation deviations on annual GDP growth using, on the one hand, the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), which is particularly useful for detecting both extreme droughts and extreme precipitation or flooding events (Wu et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2017). On the other hand, we use the annual mean temperature deviation, following Burke et al. (2015), to identify growth deviations induced by temperature variations ranging from 0 to over 2 °C. The results of these investigations are presented in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7.

3.2. Estimation of Future Losses

Future loss projections are conducted through 2100. Projected climate data—precipitation intensity and temperature deviations from historical averages—are derived from a grid of five general circulation models (GCMs), as described in Hempel et al. (2013). Future per capita GDP levels are obtained from simulations of the OECD-ENV-Growth model, which incorporates projections of key drivers of economic growth, including physical capital, employment, energy demand, human capital, natural resource extraction and rents, and total factor productivity (Dellink et al., 2017). Following Riahi et al. (2017), we use per capita GDP projections under the SSP2 emissions scenario as a reference to compare two extreme warming scenarios (SSP1 and SSP5). This Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) represents intermediate challenges and a moderate trajectory relative to other SSPs (Dellink et al., 2017). According to Baarsch et al. (2020), using a consistent SSP across low and high warming scenarios allows for a more accurate comparison of the isolated impacts of climate change on economic development.

4. Interpretation and Analysis of Results

4.1. Economic Costs Induced by Climate Shocks

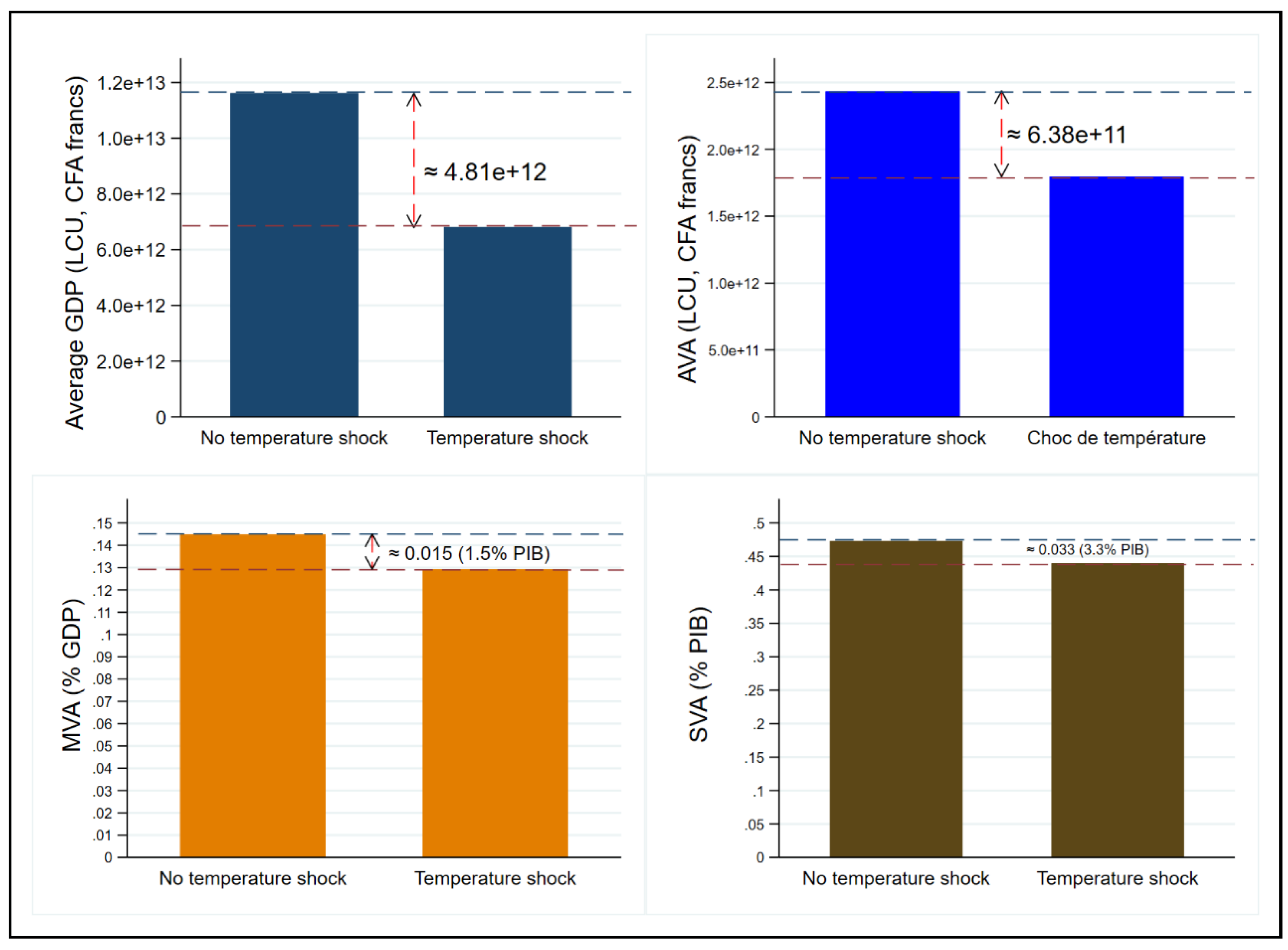

The monetary losses induced by climate change on GDP and sectoral productivities are summarized in

Table 1.

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrate the differences in impacts caused by temperature and precipitation shocks, respectively.

Figure 3, for instance, shows significant gaps between average output levels during temperature shocks and those in the absence of shocks. Since the mean outputs under temperature shocks are consistently lower than those without shocks, we can conclude that temperature shocks generate substantial losses in the outputs considered. These losses amount to 4,810 billion FCFA for GDP, representing approximately 17.36% of the average GDP over the period 1980–2022.

Figure 3.

Observed productivity losses due to temperature shocks.

Figure 3.

Observed productivity losses due to temperature shocks.

Notes: The differences shown are based on a mean comparison test between periods experiencing precipitation shocks and periods with stable average precipitation levels.

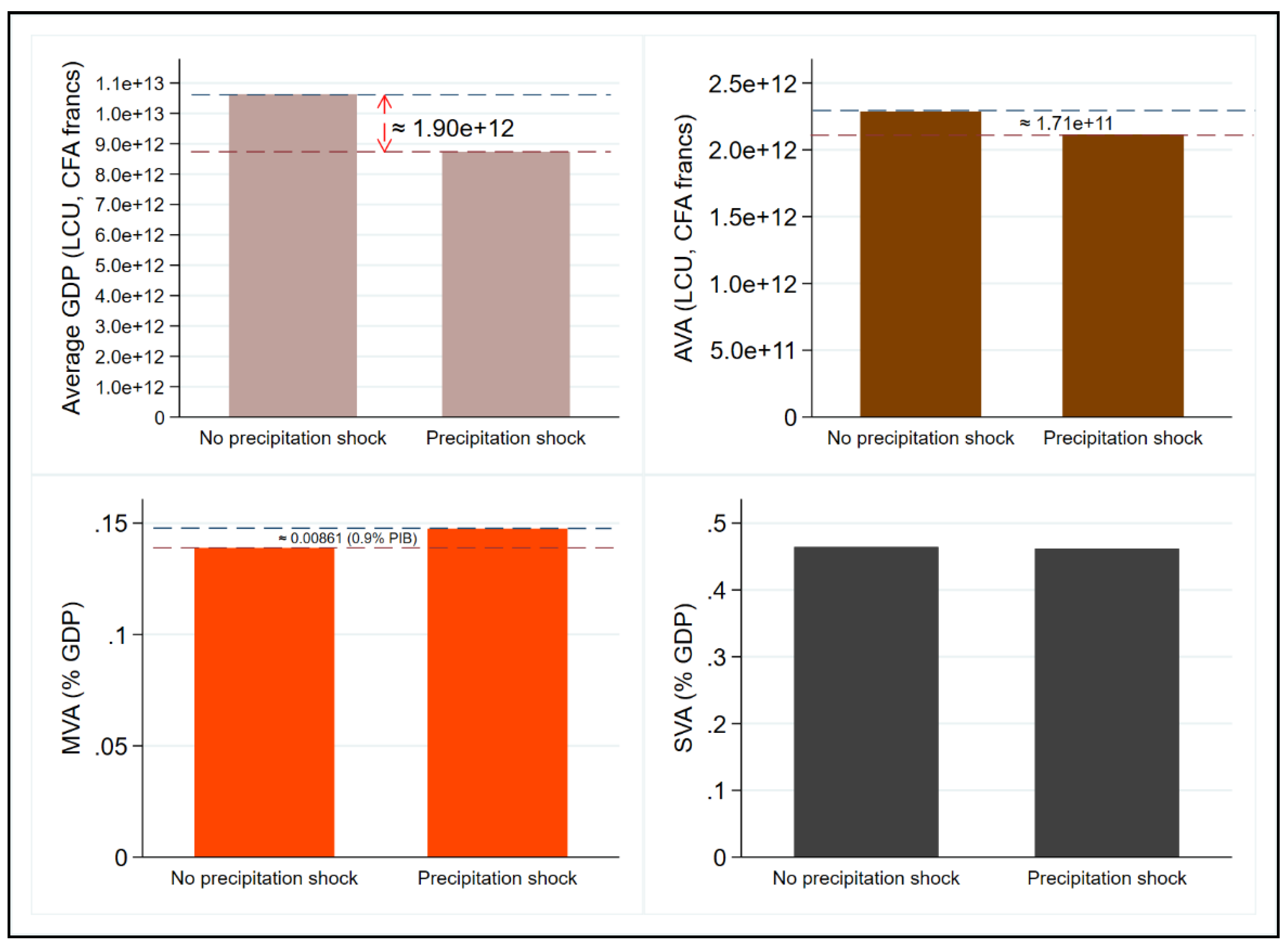

Regarding precipitation shocks, these have caused losses of approximately 1,900 billion FCFA (6.86% of the average GDP over the period), resulting in a cumulative loss of 6,710 billion FCFA (over 24.22% of GDP). The sector most affected by climate shocks is agriculture, which records losses of around 638 billion FCFA (2.3% of GDP) due to temperature shocks, and 171 billion FCFA (0.62% of GDP) due to precipitation shocks. The manufacturing (industrial) sector ranks second, with losses of about 154.5 billion FCFA from temperature shocks, but a slight gain of 88 billion FCFA from precipitation shocks (see

Figure 4). The services sector is impacted solely by temperature shocks, with losses of 340 billion FCFA, while precipitation shocks have no significant effect. These results support the findings of Baarsh et al. (2020), who, using a simple regression model for the period 1980–2014, concluded that climate change, manifested through increases in temperature and precipitation, resulted in losses of approximately 10–15% of GDP in Africa.

Figure 4.

Observed productivity losses due to precipitation shocks.

Figure 4.

Observed productivity losses due to precipitation shocks.

Notes: The differences shown are based on a mean comparison test between periods experiencing precipitation shocks and periods with stable average precipitation levels.

4.2. Observed Impact of Climate Change on Outputs

The application of the VAR model, as described in

Section 3.1, is often contingent on verifying several conditions for the time series, including stationarity and causality checks. To this end, we first employ two different tests to assess whether our series contain a unit root: (i) the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test, which accounts for complex autocorrelations by adding lagged difference terms to the time series (Dickey & Fuller, 1979); and (ii) the non-parametric Phillips-Perron (PP) test, which addresses heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation in the errors without adding lagged terms (Phillips & Perron, 1988). The test results presented in

Table 2 indicate that the variables are integrated at different orders, but when considering the variables in first differences, all z-statistics are significant. Therefore, first-differenced variables are preferred for analyzing the impact of climate change on outputs.

Furthermore, according to Engle and Granger (1987), when the variables are stationary or primarily I(1) and cointegrated, the classical Granger causality test is not strictly necessary. However, if the series are I(1) and not cointegrated, the standard Granger causality test based on the VAR (Vector Autoregressive) model should be applied, as it is the most appropriate in this case (Johansen & Juselius, 1990). Considering the isolated case of temperature variations,

Table 3 shows a bidirectional causality between temperature changes and GDP, as well as with the value added of the services sector. In contrast, there is a unidirectional causality for the agriculture and manufacturing sectors, indicating that temperature variations significantly impact these sectors, but not vice versa.

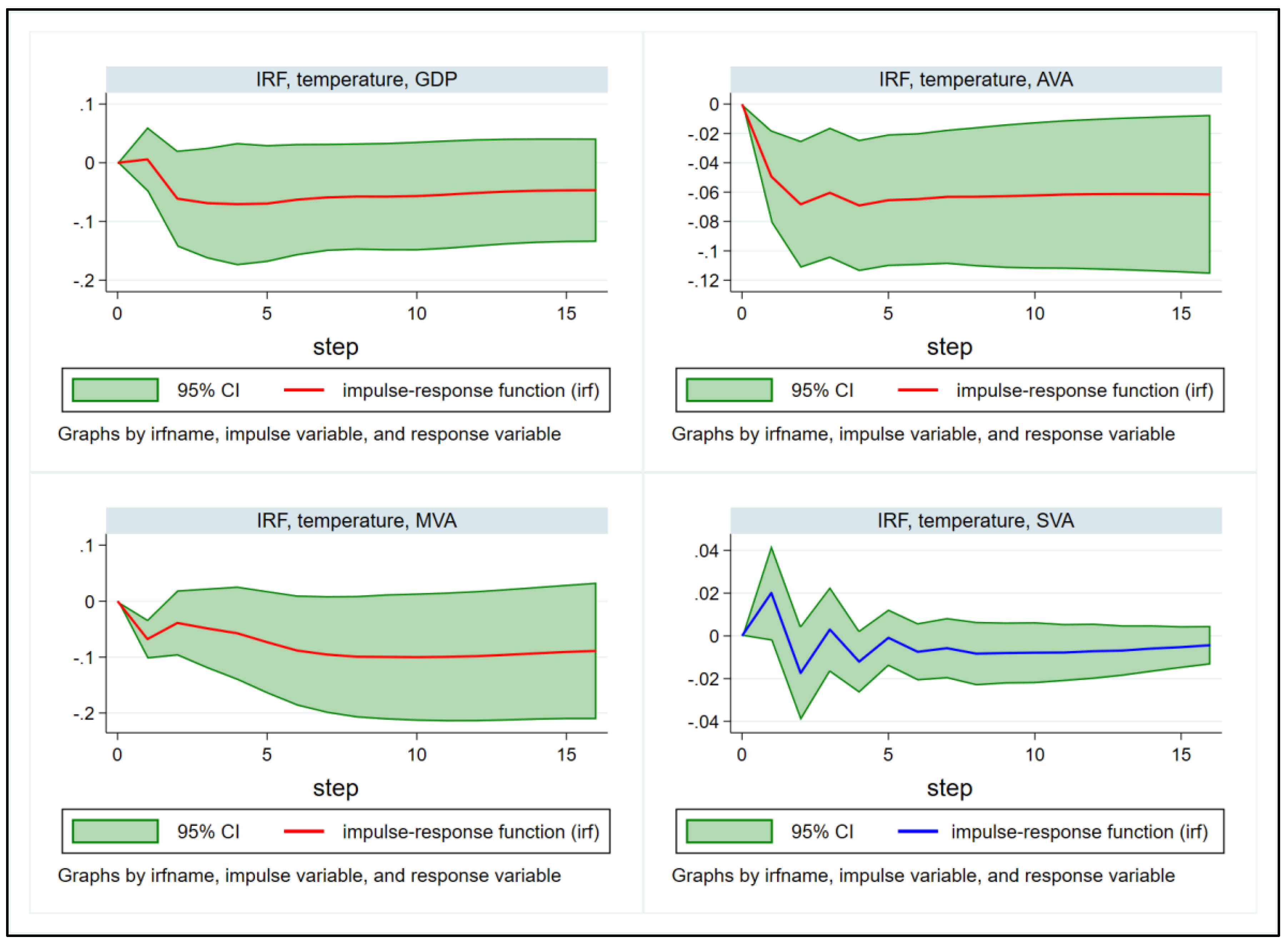

The impulse response functions obtained from the VAR model estimation are presented in

Figure 5. They highlight both the short- and long-term behaviors of the different outputs in response to temperature changes. For overall economic growth, a sudden increase in temperature leads to a contraction of GDP in the short term, reflecting the vulnerability of the national economy to climate disturbances. This negative effect, however, tends to diminish over the long term, suggesting that certain adaptation mechanisms (technological, institutional, or sectoral reallocation) gradually mitigate the shock. Nevertheless, the persistence of a generally adverse impact confirms Cameroon’s structural dependence on climate-sensitive sectors.

Figure 5.

Impulse response functions of the VAR estimation of the impact of temperature variations on outputs.

Figure 5.

Impulse response functions of the VAR estimation of the impact of temperature variations on outputs.

Notes: The IRFs presented are obtained from the application of VAR models with a 95% confidence interval.

Source: authors’ computation.

This finding aligns with Dell et al. (2012), who show that temperature increases reduce growth in hot countries, with persistent but attenuated effects over the long term. Agricultural value added (AVA) reacts very negatively and persistently to temperature shocks. This vulnerability reflects Cameroon’s high exposure to climatic variations, as agricultural production still heavily depends on rainfall and extensive farming methods (Molua, 2007; Mbuli et al., 2021). Agricultural losses affect both food security and rural incomes. Similar results were reported by Alagidede et al. (2016), emphasizing that agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa is the sector most impacted by climatic anomalies, thereby slowing overall economic growth.

Regarding manufacturing value added (MVA), the impact of temperature shocks is negative but less pronounced and tends to dissipate more quickly. This can be attributed to the relative resilience of the industrial sector, which can rely on imported inputs or adjust production processes to mitigate disruptions caused by climatic hazards. Nevertheless, the sector’s dependence on agricultural raw materials and infrastructure vulnerable to extreme weather events remains a source of instability. These findings align with Chamma (2024), who shows that climate shocks affect industrial production in some African countries, though indirectly and less persistently than in agriculture. Finally, the services sector (SVA) is relatively less sensitive to temperature shocks, with observed impacts being moderate and short-lived. Services related to finance, telecommunications, or trade are less directly dependent on weather conditions. However, certain segments such as tourism, transport, and distribution remain exposed. These conclusions are consistent with Dube et al. (2024), who find that while climate impacts on the tourism sector in Africa are significant, they remain marginal compared to the effects on agriculture.

A key observation emerging from these results is the interdependence between sectors. Climatic events such as floods or droughts primarily affect agricultural productivity and resource exploitation, which indirectly influences the growth of other sectors since a large portion of industrial and manufacturing inputs originates from agricultural activities (Osuagwu, 2020). Conversely, underperformance in other sectors can also affect agricultural productivity (Nwani et al., 2020).

Consistent with the work of Dell et al. (2012) and more recently Baarsch et al. (2020), we adopt a theoretical Cobb-Douglas production function to estimate a piecewise multivariate regression model, using per capita GDP growth as the dependent variable to assess the non-linear effect of temperature variations on economic growth. Temperature is included by considering its deviation from the mean, ranging from 0 to 2 °C. The results, shown in

Figure 6, indicate that temperature deviations can lead to a loss of up to approximately 15% of per capita GDP growth in the worst-case scenario for a 2 °C deviation. Conversely, under more favorable conditions with moderate temperature deviations, the impact of temperature variations results in a loss of about 8.5% for Cameroon (short-dashed dark line), compared to 7.5% for the African average (dark pink line). These findings are consistent with recent studies in Nigeria, another African country with diverse climatic conditions, where an increase of more than 1 °C in average temperatures could reduce agricultural GDP by 4% to 6% under the most pessimistic scenarios (Opeyemi et al., 2022).

Figure 6.

Growth effect of increasing temperature deviation above the mean (1980-2022).

Figure 6.

Growth effect of increasing temperature deviation above the mean (1980-2022).

Notes: The different dashed trajectories are based on simulations from the various draws, while the results for the median are shown as a short-dashed line. The dark pink line represents the whole of Africa, and the short-dashed line represents Cameroon.

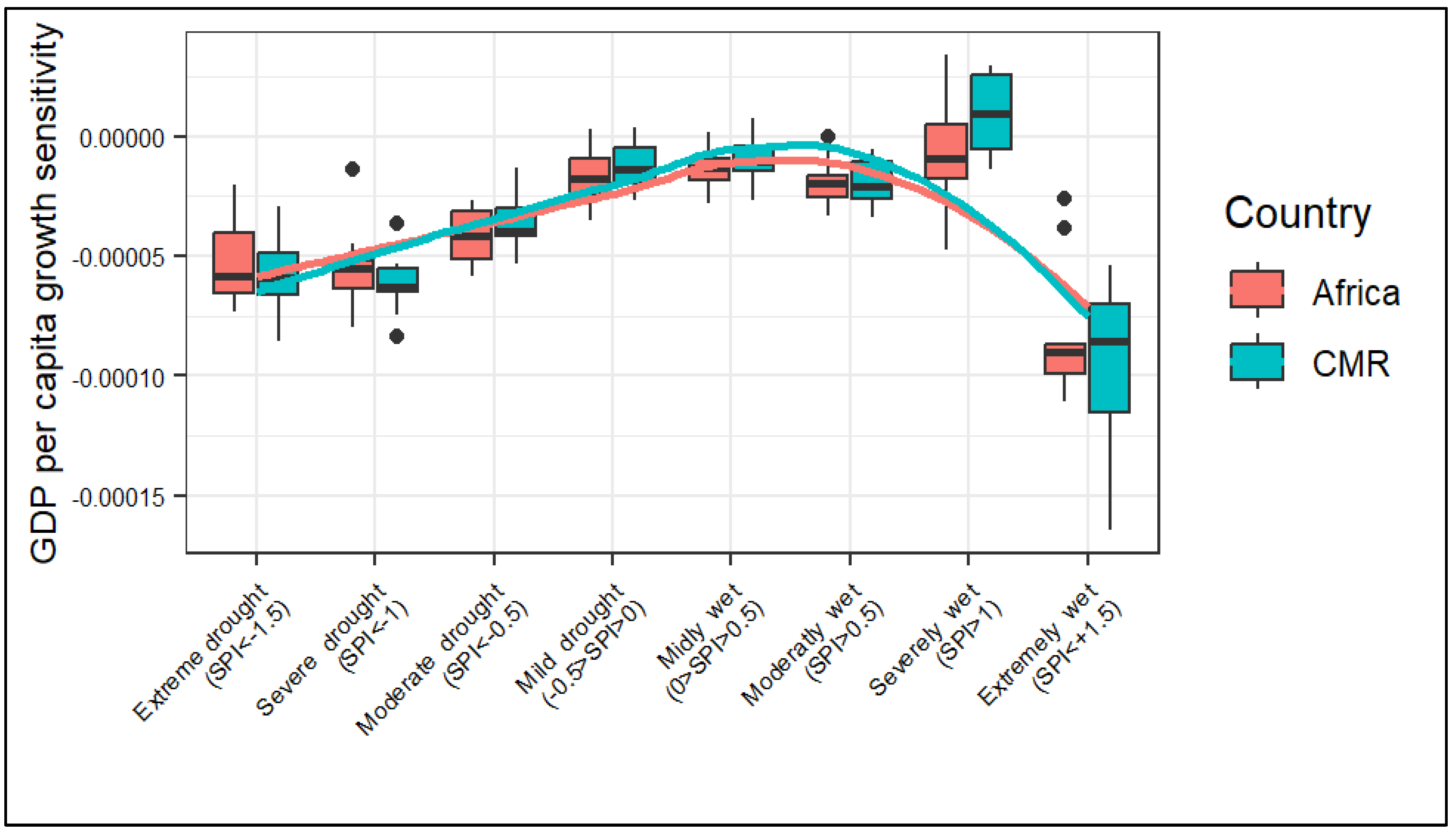

Regarding precipitation (measured by the SPI), we assess the non-linear effect according to different precipitation intensities, ranging from extremely dry (SPI < -1.5) to extremely wet (SPI > 1.5).

Figure 7 shows that the sensitivity of GDP per capita to the effects of varying precipitation levels exhibits a concave, inverted U-shaped relationship. More specifically, GDP sensitivity is negative and pronounced at extreme SPI values compared to sensitivity at values between -1 and 1. This non-linearity indicates the existence of a favorable precipitation range for good economic performance, particularly when SPI values are close to 0. Recent studies have also documented that some countries, such as Senegal, have recorded strong economic performance when precipitation levels were moderately above the average (Jerven, 2014).

Figure 7.

Sensitivity of GDP per capita growth (in log) to levels of precipitation intensity.

Figure 7.

Sensitivity of GDP per capita growth (in log) to levels of precipitation intensity.

Notes: The x-axis represents precipitation intensity, measured using the SPI, varying from extremely dry (left-hand side) to extremely wet (right-hand side). The orange boxplots represent the average variation among African countries, while the blue ones represent the sensitivity of GDP per capita in Cameroon. The lines connecting the boxes are the result of the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (loess) and are only illustrative.

Furthermore, we observe that the sensitivity of GDP per capita to extreme drought events is lower than that associated with extreme precipitation events. This indicates that Cameroon, roughly like the rest of Africa, is more vulnerable to wet events such as floods (Baarsh et al., 2020). Compared to the rest of Africa, we find that Cameroon’s GDP growth is more negatively affected in the presence of extreme drought, whereas the African average is relatively more impacted under severe and extreme wet conditions.

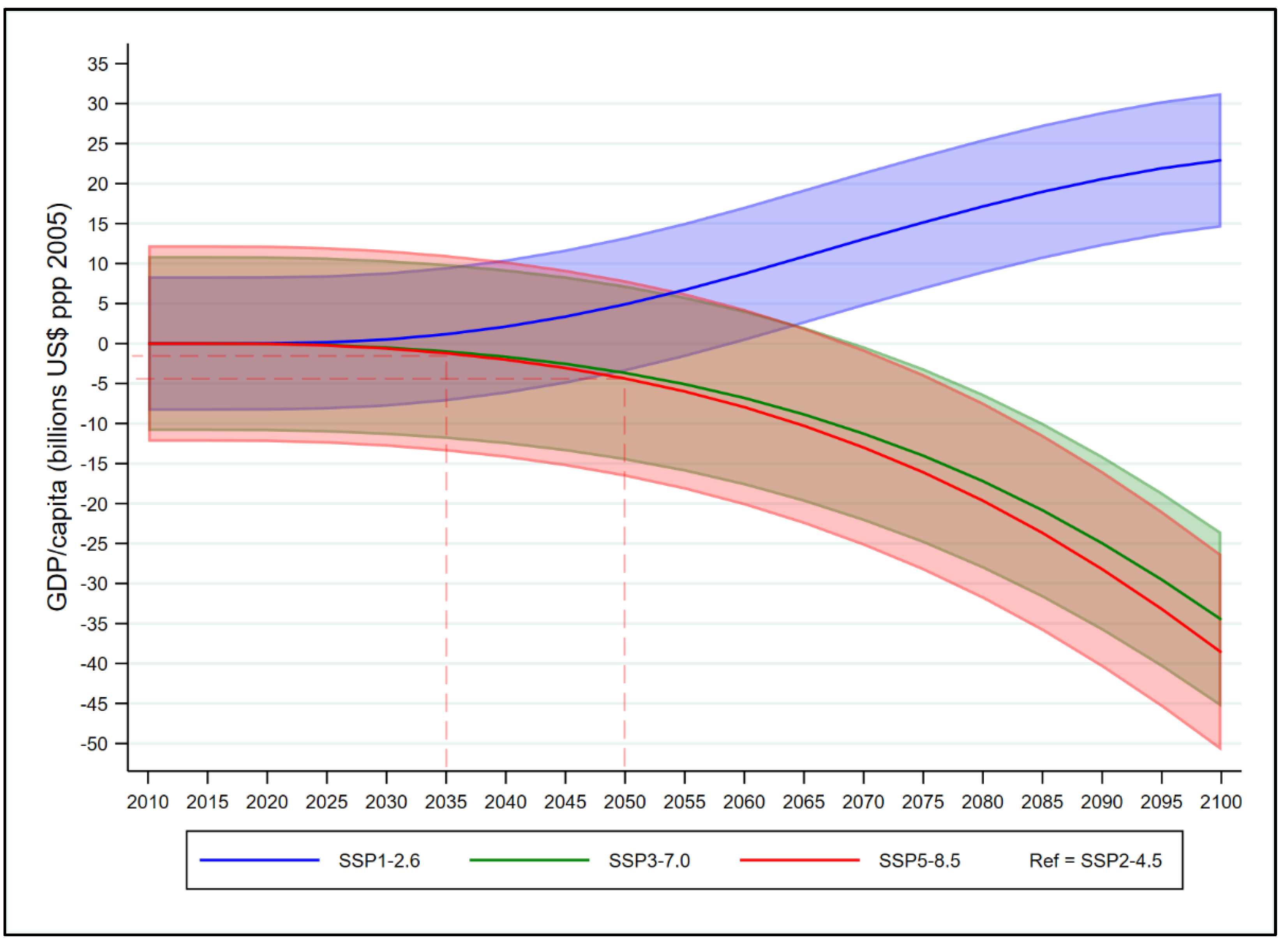

4.3. Projected Impact of Climate Change on Economic Growth in Cameroon

Figure 8 presents the projected impact of climate change on Cameroon’s annual per capita GDP, expressed as deviations from the moderate scenario (SSP2) taken as the reference. The output deviation projections are interpreted based on two main scenarios: SSP1, or low warming (in blue), which assumes limited warming with strong reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and SSP5, or high warming (in red), which assumes continued GHG emissions until 2100. Additionally, we consider SSP3, an intermediate-high scenario (in green), which assumes the absence of ambitious mitigation measures and severe climate impacts. Converting the observed loss coefficients shows that projected losses for Cameroon under the pessimistic SSP5 scenario are particularly alarming, reaching approximately USD 5 billion (FCFA 3,000 billion) in 2035, equivalent to 11% of the 2024 GDP, USD 15 billion (FCFA 9,000 billion) in 2050, or 31% of the 2024 GDP, and a massive drop to USD 45 billion (FCFA 27,000 billion) in 2100, i.e., over 97% of the 2024 GDP. These projections reflect a drastic decline in per capita GDP, which could plunge the country into a prolonged recession. One of the main drivers of these losses is the vulnerability of the agricultural sector, which still represents a significant share of Cameroon’s GDP (World Bank Group, 2022). With projected temperature increases and reduced rainfall, agricultural output could decline substantially, negatively affecting both economic growth and the country’s food security.

Figure 8.

Climate change–induced deviations in per capita GDP in Cameroon under emission scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5) relative to the reference scenario (SSP2-4.5).

Figure 8.

Climate change–induced deviations in per capita GDP in Cameroon under emission scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5) relative to the reference scenario (SSP2-4.5).

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Notes: Simulations are based on three warming scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5). Shaded areas represent the respective uncertainty ranges for each scenario.

However, under a scenario of reduced emissions and the implementation of effective adaptation policies (SSP1), Figure 10 indicates that Cameroon could achieve a production gain estimated at around 5 billion USD by 2050. Comparatively, similar studies conducted in Senegal suggest that, under an extreme warming scenario, GDP per capita could decrease by -10% to -15% by 2050 due to agricultural losses and reduced labor productivity (Sultan & Gaetani, 2016). In Chad, a landlocked country heavily dependent on rainfed agriculture, Barrios et al. (2010) estimate that climate change could lead to a GDP contraction of -20% to -30% by the end of the century, due to the extreme semi-arid conditions of the Sahel.

5. Conclusion

The objective of this study was to analyze and quantify the economic losses caused by climate change in Cameroon and to forecast potential future impacts. Using annual data from 1980 to 2022 and projections up to 2100, we adopted a diversified methodology to obtain results summarized in four main points. First, we found that temperature shocks caused economic losses of approximately 4,810 billion CFA francs over the 1980–2022 period, while precipitation shocks resulted in slightly lower losses of around 1,900 billion CFA francs during the same period. Second, sectoral analyses revealed that the agricultural sector is the most affected by climate change in Cameroon, followed by the industrial and manufacturing sectors. The services sector, on the other hand, is impacted only by temperature shocks, with precipitation shocks showing no significant effect. Long-term analyses indicate that climate shocks have significant short-term negative impacts on overall GDP and sectoral outputs, which stabilize in the long run, reflecting the influence of adopted adaptation measures, though the effects remain negative. Third, the study shows that a temperature deviation exceeding 2 °C leads to a loss of about 8.5% of GDP growth, which can reach as much as 15% in the worst-case scenario. Additionally, we find a non-linear relationship between precipitation variations, as measured by the SPI, and GDP sensitivity, with extreme droughts causing greater output losses for Cameroon compared to the rest of Africa, while extreme rainfall or wet conditions have relatively less negative effects for Cameroon than the African average. Fourth, projection analyses indicate that under the pessimistic scenario, Cameroon could lose up to 11% of its 2024 GDP and up to 35% by 2050, whereas under the optimistic scenario, a slight increase of around 5% could be observed by 2050. Furthermore, the study identifies the most vulnerable sectors requiring priority interventions as housing, food security, and health.

These results indeed provide an important basis for a better understanding of the damage caused by climate change to the Cameroonian economy and offer elements that can support research initiatives or the mobilization of adaptation funding. Several recommendations can also be formulated. These include: increasing investments in education and technology, which could partially offset climate-related losses by improving overall productivity; integrating climate-specific parameters into regional agricultural policies to better guide planting schedules and potential irrigation needs; developing a national climate insurance program targeting both farmers and economic operators to enhance resilience to climate shocks; promoting green innovations and adapting fiscal instruments to stimulate investment in climate-smart agriculture; and strengthening climate early-warning systems. From a long-term perspective, these results underscore the need to reinforce climate adaptation policies and sectoral diversification strategies to reduce the structural vulnerability of the Cameroonian economy.

Moreover, some limitations of this study should be acknowledged, particularly its macroeconomic focus, which considers only aggregated indicators and does not account for microeconomic factors or sector-specific determinants. Future research could, for instance, focus specifically on the agricultural sector to evaluate the monetary costs of climate change on perennial crop production and conduct a comparative analysis across the five agroecological zones of Cameroon, which differ in climatic conditions and soil characteristics. Additionally, future studies could assess the projected costs of climate change impacts on the various productive sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study will be made available on request.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Variables and their descriptions.

Table A1.

Variables and their descriptions.

| Variable |

Description |

Source |

| GDP |

Gross domestic product (current) |

WDI |

| GDP/capita |

GDP per capita (constant prices, LCU) |

WDI |

| GDP growth |

Annual GDP Growth Rate |

WDI |

| AVA |

Agricultural, forestry and fishing value added (constant prices, FCFA) |

WDI |

| MVA |

Manufacturing value added (% GDP) |

WDI |

| SVA |

Value added of services (% GDP) |

WDI |

| Temperature |

Average annual temperature level ((TempMax + TempMin )/ 2), in °C |

Authors’ calculations, based on CCKP data (CCKP) |

| Precipitation |

Average annual precipitation volume (mm) |

CCKP (2025) |

| Temperature deviation |

Deviation of temperature level from the historical average of 1980-2014 |

Authors’ calculations |

| Precipitation |

Deviation of precipitation level from the historical average of 1980-2014 |

Authors’ calculations |

| SPI |

Standardized precipitation index |

CCKP (2025) |

| Temperature shocks |

Binary variable, which considers that there is a temperature shock in the event of a deviation of plus or minus 1 standard deviation from the mean, and 0 otherwise |

Authors’ calculations |

| Precipitation shock |

Binary variable, which considers that there is a precipitation shock in the event of a deviation of plus or minus 1 standard deviation from the mean, and 0 otherwise |

ONACC calculations |

| Arab land |

Arab land area as a percentage of total land area |

WDI |

| Government size |

Size of Government: Spending, Taxes, and Business |

QOG |

| FDI |

Foreign direct investment, inflow |

WDI |

| Natural resources |

Total natural resource rent, as a % of GDP |

WDI |

| Education |

Secondary school enrollment rate |

WDI |

References

- Abidoye, B. O.; Odusola, A. F. Climate change and economic growth in Africa: an econometric analysis. Journal of African Economies 2015, 24(2), 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagidede, P.; Adu, G.; Frimpong, P. B. The effect of climate change on economic growth: evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Environmental Economics and Policy Studies 2016, 18(3), 417–436. [Google Scholar]

- Amougou, J. A. Situation des changements climatiques au Cameroun-Les éléments scientifiques, incidences, adaptation et vulnérabilité. Environmental Law and Policy in Cameroon-Towards Making Africa the Tree of Life| Droit et Politique de L’environnement au Cameroun-Afin de Faire de L’Afrique L’arbre de Vie. 1st ed. Baden-Baden, Germany: Nomos Publishing House, 687-712.

- Arndt, C.; Strzepeck, K.; Tarp, F.; Thurlow, J.; Fant, C., IV; Wright, L. Adapting to climate change: an integrated biophysical and economic assessment for Mozambique. Sustainability Science 2011, 6(1), 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrow, K. J.; Dasgupta, P.; Goulder, L. H.; Mumford, K. J.; Oleson, K. Sustainability and the measurement of wealth. Environment and development economics 2012, 17(3), 317–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwoli, L.; Erhabor, G. E.; Gbakima, A. A.; Haileamlak, A.; Ntumba, J. M. K.; Kigera, J.; Zielinski, C. COP27 climate change conference: urgent action needed for Africa and the world. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2023, 23(1), 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffhammer, M. Climate Adaptive Response Estimation: Short and long run impacts of climate change on residential electricity and natural gas consumption. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 2022, 114, 102669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awazi, N. P. Agroforestry for climate change adaptation, resilience enhancement and vulnerability attenuation in smallholder farming systems in Cameroon. J Atmos Sci Res 2022, 5(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, G. M.; Fisseha, F. L. Does climate change affect the financial stability of Sub-Saharan African countries? Climatic Change 2024, 177(10), 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baarsch, F.; Granadillos, J. R.; Hare, W.; Knaus, M.; Krapp, M.; Schaeffer, M.; Lotze-Campen, H. The impact of climate change on incomes and convergence in Africa. World Development 2020, 126, 104699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E. B.; Hochard, J. P. The impacts of climate change on the poor in disadvantaged regions. In Review of Environmental Economics and Policy; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios, S.; Bertinelli, L.; Strobl, E. Trends in rainfall and economic growth in Africa: A neglected cause of the African growth tragedy. The Review of Economics and Statistics 2010, 92(2), 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R. J. Rare disasters, asset prices, and welfare costs. American Economic Review 2009, 99(1), 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bele, M. Y.; Tiani, A. M.; Somorin, O. A.; Sonwa, D. J. Exploring vulnerability and adaptation to climate change of communities in the forest zone of Cameroon. Climatic Change 2013, 119(3), 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomdzele, E., Jr.; Molua, E. L. Assessment of the impact of climate and non-climatic parameters on cocoa production: a contextual analysis for Cameroon. Frontiers in Climate 2023, 5, 1069514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Meeks, R.; Ghile, Y.; Hunu, K. Is water security necessary? An empirical analysis of the effects of climate hazards on national-level economic growth. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2013, 371, 20120416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, M.; Alampay Davis, W. M.; Diffenbaugh, N. S. Large potential reduction in economic damages under UN mitigation targets. Nature 2018, 557(7706), 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, M.; Hsiang, S. M.; Miguel, E. Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 2015, 527(7577), 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabejong, N. E. A review on the impact of climate change on food security and malnutrition in the Sahel region of Cameroon. In Climate Change and Health: Improving Resilience and Reducing Risks; 2016; pp. 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Chamma, D. D. Climate change and economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa: an empirical analysis of aggregate-and sector-level growth. Journal of Social and Economic Development 2024, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikowore, N. R.; Barber, I.; Chanza, N.; Ngan, C.; Yam, S. A. Climate change vulnerabilities and adaptation strategies in rural communities: an intersectional approach in the Baham sub-division of Cameroon. African Geographical Review 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, P.; Conway, G.; Venables, T. Climate change and Africa. Oxford review of economic policy 2008, 24(2), 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defrance, D.; Sultan, B.; Castets, M.; Famien, A. M.; Baron, C. Impact of climate change in West Africa on cereal production per capita in 2050. Sustainability 2020, 12(18), 7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, M.; Jones, B. F.; Olken, B. A. Temperature shocks and economic growth: Evidence from the last half century. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2012, 4(3), 66–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, M.; Jones, B. F.; Olken, B. A. What do we learn from the weather? The new climate-economy literature. Journal of Economic literature 2014, 52(3), 740–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellink, R.; Chateau, J.; Lanzi, E.; Magné, B. Long-term economic growth projections in the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Global Environmental Change 2017, 42, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, D. A.; Fuller, W. A. Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American statistical association 1979, 74(366a), 427–431. [Google Scholar]

- Diep, L.; Godfrey, S.; Tunhuma, F.; Campos, L. C.; Lakhanpaul, M.; Parikh, P. Cascading impacts of climate change on child survival and health in Africa. Nature Climate Change 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, K.; Nhamo, G.; Kilungu, H.; Hambira, W. L.; El-Masry, E. A.; Chikodzi, D.; Molua, E. L. Tourism and climate change in Africa: Informing sector responses. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2024, 32(9), 1811–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R. F.; Granger, C. W. Co-integration and error correction: representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica: journal of the Econometric Society 1987, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fankhauser, S. Valuing climate change: the economics of the greenhouse; Routledge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano, D.; Recha, J.; Ambaw, G.; MacSween, K.; Solomon, D.; Wollenberg, E. Assessment of agricultural emissions, climate change mitigation and adaptation practices in Ethiopia. Climate policy 2022, 22(4), 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérardeaux, E.; Sultan, B.; Palaï, O.; Guiziou, C.; Oettli, P.; Naudin, K. Positive effect of climate change on cotton in 2050 by CO2 enrichment and conservation agriculture in Cameroon. Agronomy for sustainable development 2013, 33(3), 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, D. N.; Porter, D. C. Basic Econometrics, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hallegatte, S.; Rozenberg, J. Climate change through a poverty lens. Nature Climate Change 2017, 7(4), 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, S.; Frieler, K.; Warszawski, L.; Schewe, J.; Piontek, F. A trend-preserving bias correction–the ISI-MIP approach. Earth System Dynamics 2013, 4(2), 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, S. Climate econometrics. Annual Review of Resource Economics 2016, 8(1), 43–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, S.; Kopp, R.; Jina, A.; Rising, J.; Delgado, M.; Mohan, S.; Houser, T. Estimating economic damage from climate change in the United States. Science 2017, 356(6345), 1362–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Cambridge University Press, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jerven, M. African Growth Miracle or Statistical Tragedy? Interpreting trends in the data over the past two decades. WIDER Working Paper 2014, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, S.; Juselius, K. Maximum likelihood estimation and inference on cointegration—with appucations to the demand for money. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and statistics 1990, 52(2), 169–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, I.; Grunberg, I.; Stern, M. A. Defining global public goods. In Global public goods: International cooperation in the 21st century; 1999; pp. 2–19. [Google Scholar]

- Keohane, R. O.; Victor, D. G. Cooperation and discord in global climate policy. Nature Climate Change 2016, 6(6), 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavhagali, V.; Reckien, D.; Biesbroek, R.; Mantlana, B.; Pfeffer, K. Understanding the climate change adaptation policy landscape in South Africa. Climate Policy 2024, 24(4), 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompas, T.; Pham, V. H.; Che, T. N. The effects of climate change on GDP by country and the global economic gains from complying with the Paris climate accord. Earth’s Future 2018, 6(8), 1153–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. R.; Raftery, A. E. Country-based rate of emissions reductions should increase by 80% beyond nationally determined contributions to meet the 2 C target. Communications earth & environment 2021, 2(1), 29. [Google Scholar]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pörtner, H. O.; Roberts, D.; Skea, J.; Shukla, P. R.; Waterfield, T. Global warming of 1.5 C. 9 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2019.

- Mbuli, C. S.; Fonjong, L. N.; Fletcher, A. J. Climate change and small farmers’ vulnerability to food insecurity in Cameroon. Sustainability 2021, 13(3), 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molua, E. L. The economic impact of climate change on agriculture in Cameroon. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2007, 4364. [Google Scholar]

- Molua, E. L.; Mbah, M. F.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Ndip, F. E.; Etomes, S. E.; Kambiet, P. L. K.; Nanfouet, M. A. Indigenizing climate change adaptation education in a developing country context: what are the key drivers? Experimental Agriculture 2025, 61, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngepah, N.; Tchuinkam Djemo, C. R.; Saba, C. S. Forecasting the economic growth impacts of climate change in South Africa in the 2030 and 2050 horizons. Sustainability 2022, 14(14), 8299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhaus, W. D. To slow or not to slow: the economics of the greenhouse effect. The economic journal 1991, 101(407), 920–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwani, S. E.; Kelikume, I.; Osuji, E. Does service sector growth cause agricultural and industrial development? A dynamic econometric approach. International Journal of Management, Economics and Social Sciences (IJMESS) 2020, 9(2), 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotoso, A. B.; Letsoalo, S.; Olagunju, K. O.; Tshwene, C. S.; Omotayo, A. O. Climate change and variability in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of trends and impacts on agriculture. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 414, 137487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opeyemi, G.; Husseini, S.; Ikumapayi, H. A. Climate change and agriculture: Modelling the impact of carbon dioxide emission on cereal yield in Nigeria (1961-2018). Journal of Research in Forestry, Wildlife and Environment 2022, 14(2), 128–134. [Google Scholar]

- Osuagwu, E. S. Empirical evidence of a long-run relationship between agriculture and manufacturing industry output in Nigeria. Sage Open 2020, 10(1), 2158244019899045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P. C.; Perron, P. Testing for a Unit Root in Time Series Regression. Biometrika 1988, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigou, A. C. The Economics of Welfare; Macmillan, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, P. M. Increasing returns and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy 1986, 94(5), 1002–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A. Economic resilience to natural and man-made disasters: Multidisciplinary origins and contextual dimensions. Environmental hazards 2007, 7(4), 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safougne Djomekui, B. L.; Ngouanet, C.; Smit, W. Urbanization and Health Inequity in Sub-Saharan Africa: Examining Public Health and Environmental Crises in Douala, Cameroon. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2025, 22(8), 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S. N.; Mendelsohn, R. Measuring impacts and adaptations to climate change: a structural Ricardian model of African livestock management 1. Agricultural economics 2008, 38(2), 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdeczny, O.; Adams, S.; Baarsch, F.; Coumou, D.; Robinson, A.; Hare, W.; Reinhardt, J. Climate change impacts in Sub-Saharan Africa: from physical changes to their social repercussions. Regional Environmental Change 2017, 17(6), 1585–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C. A. Macroeconomics and reality. In Econometrica: journal of the Econometric Society; 1980; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, N. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review; Cambridge University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, N. The structure of economic modeling of the potential impacts of climate change: grafting gross underestimation of risk onto already narrow science models. Journal of Economic Literature 2013, 51(3), 838–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, N. Why are we waiting?: The logic, urgency, and promise of tackling climate change; MIT press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan, B.; Gaetani, M. Agriculture in West Africa in the twenty-first century: climate change and impacts scenarios, and potential for adaptation. Frontiers in plant science 2016, 7, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, B.; Guan, K.; Kouressy, M.; Biasutti, M.; Piani, C.; Hammer, G. L.; Lobell, D. B. Robust features of future climate change impacts on sorghum yields in West Africa. Environmental Research Letters 2014, 9(10), 104006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamoffo, A. T.; Weber, T.; Akinsanola, A. A.; Vondou, D. A. Projected changes in extreme rainfall and temperature events and possible implications for Cameroon’s socio-economic sectors. Meteorological Applications 2023, 30(2), e2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingem, M.; Rivington, M.; Bellocchi, G.; Azam-Ali, S.; Colls, J. Effects of climate change on crop production in Cameroon. Climate Research 2008, 36(1), 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tol, R. S. The economic effects of climate change. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2009, 23(2), 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalefac, M.; Hiol Hiol, F.; Mahé, G.; Laraque, A.; Sonwa, D. J.; Scholte, P.; Doumenge, C. Climate of Central Africa: past, present and future; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNFCCC. Paris Agreement; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M.; Gao, L. Flood/drought event identification using an effective indicator based on the correlations between multiple time scales of the Standardized Precipitation Index and river discharge. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 2017, 128(1), 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Cameroun—Rapport National sur le Climat et le Développement. CCDR Series. World Bank. 2022. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10986/38242.

- Wu, H.; Svoboda, M. D.; Hayes, M. J.; Wilhite, D. A.; Wen, F. Appropriate application of the standardized precipitation index in arid locations and dry seasons. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, S. Effects of climate change on economic growth: A perspective of the heterogeneous climate regions in Africa. Sustainability 2023, 15(9), 7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

| 1 |

These agroecological zones are: (i) the Sudanian-Sahelian zone (covering the Far North and North regions); (ii) the High Savanna zone (Adamawa); (iii) the High Plateau zone (West and Northwest); (iv) the single-rainfall forest zone (Littoral and Southwest); and (v) the bimodal rainfall forest zone (Center, South, and East). |

| 2 |

The University of Notre Dame frequently publishes data and reports with the mission of helping countries, cities, and businesses better understand their vulnerability to climate change, and to assess their social, economic, and governance capacity and preparedness for adaptation. See: https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/

|

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).