Submitted:

13 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. In Vitro nsPEF and CAP Treatment

2.3. Viability Determined by Metabolic Activity Assay

2.4. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm) Analysis

2.5. Caspase 3/7 Activity

2.6. Western Blot Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

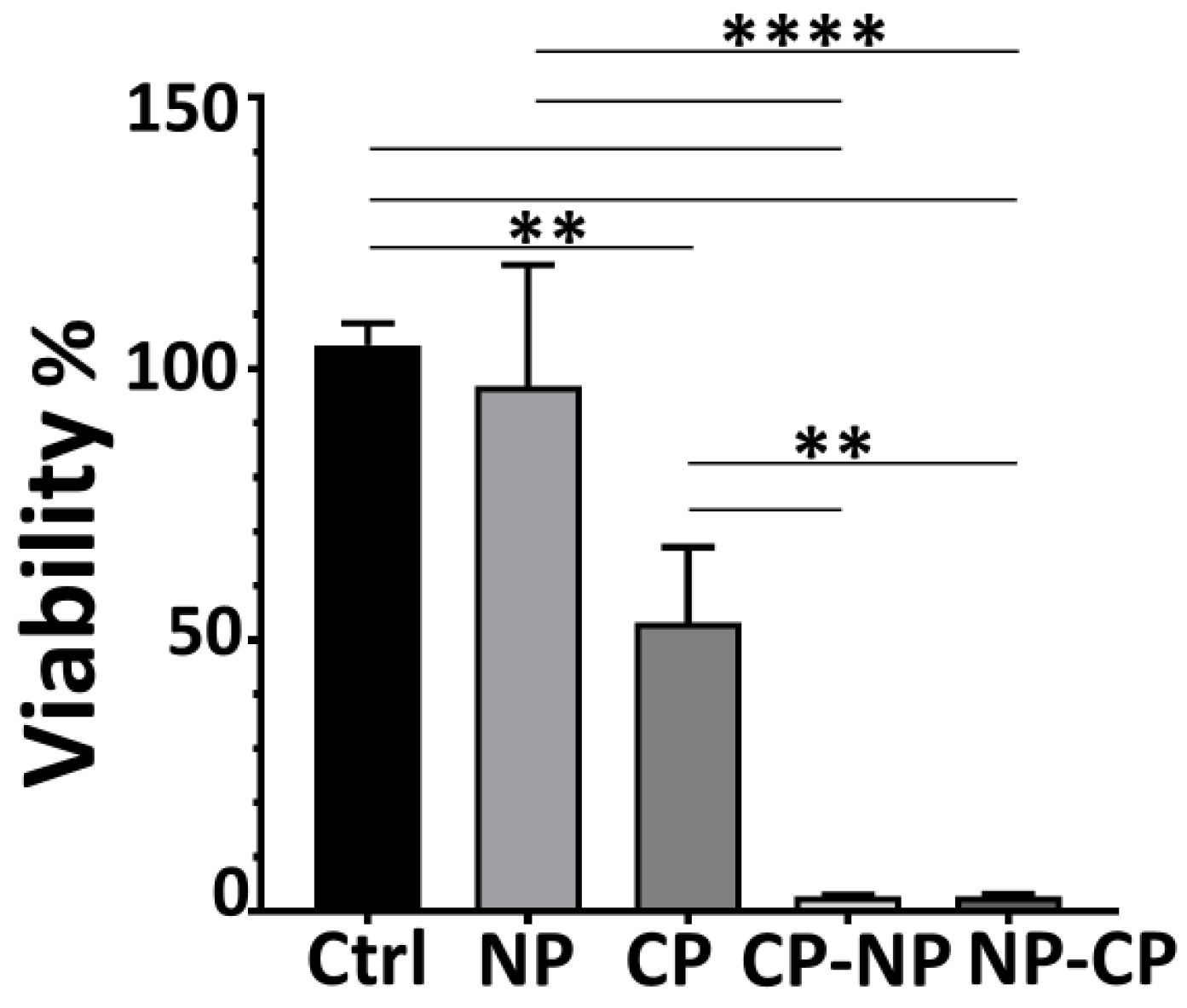

3.1. Combined nsPEF–CAP Treatment Markedly Reduces Pancreatic Cancer Cell Viability

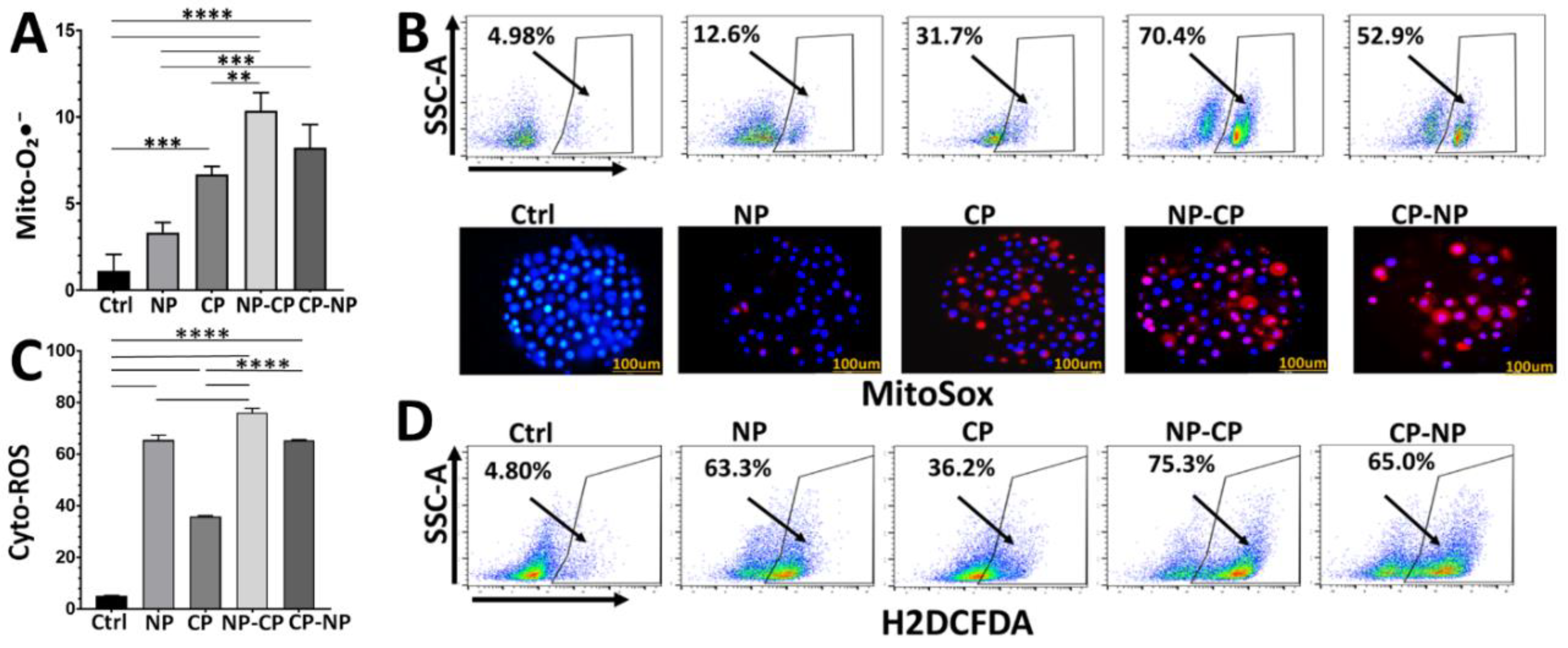

3.2. 2-nsPEF–CAP Treatments Elevate Mitochondrial Superoxide and Cytoplasmic ROS Production

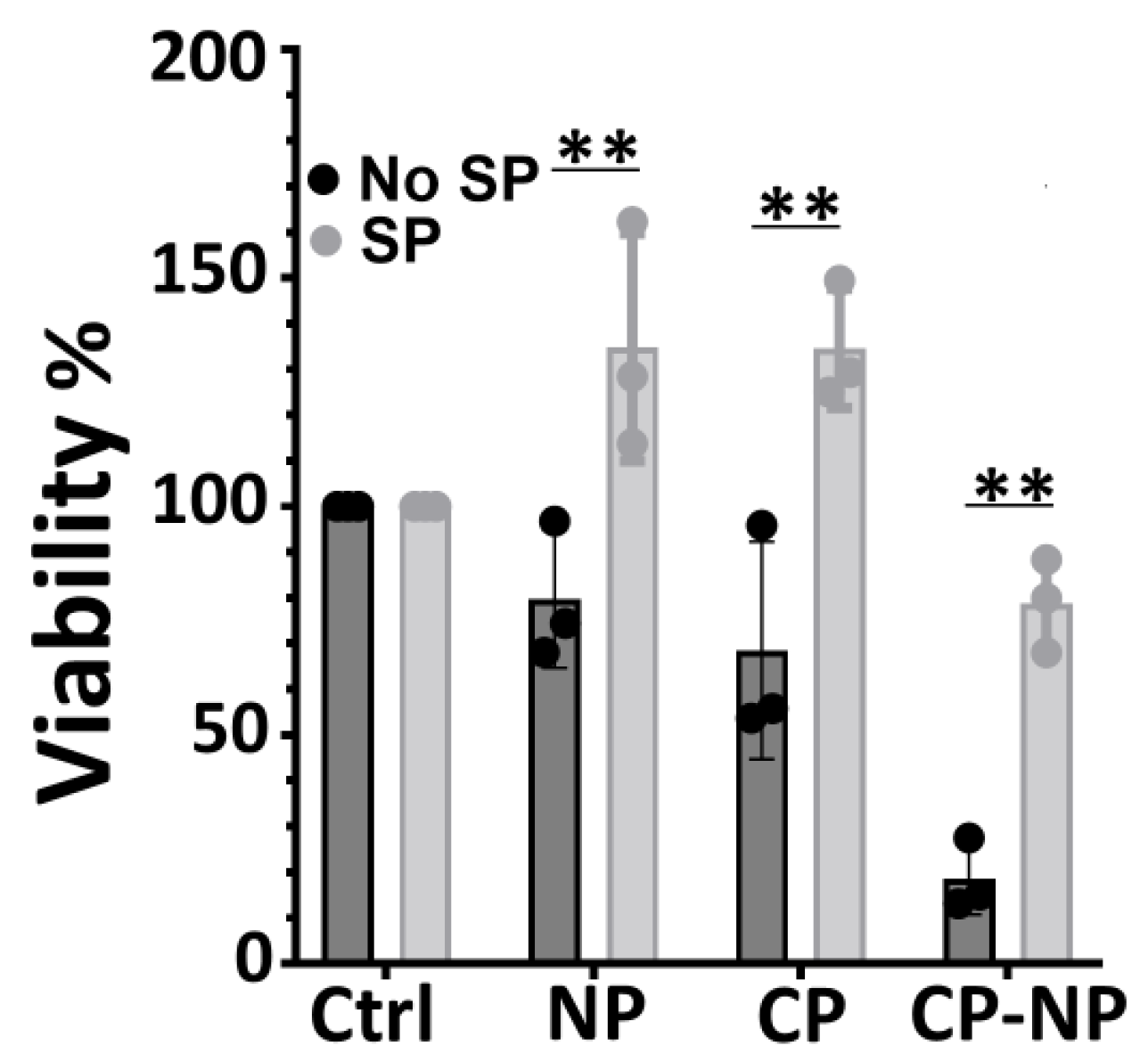

3.3. ROS Scavenging Rescues Cells from Dual Treatment-Induced Death

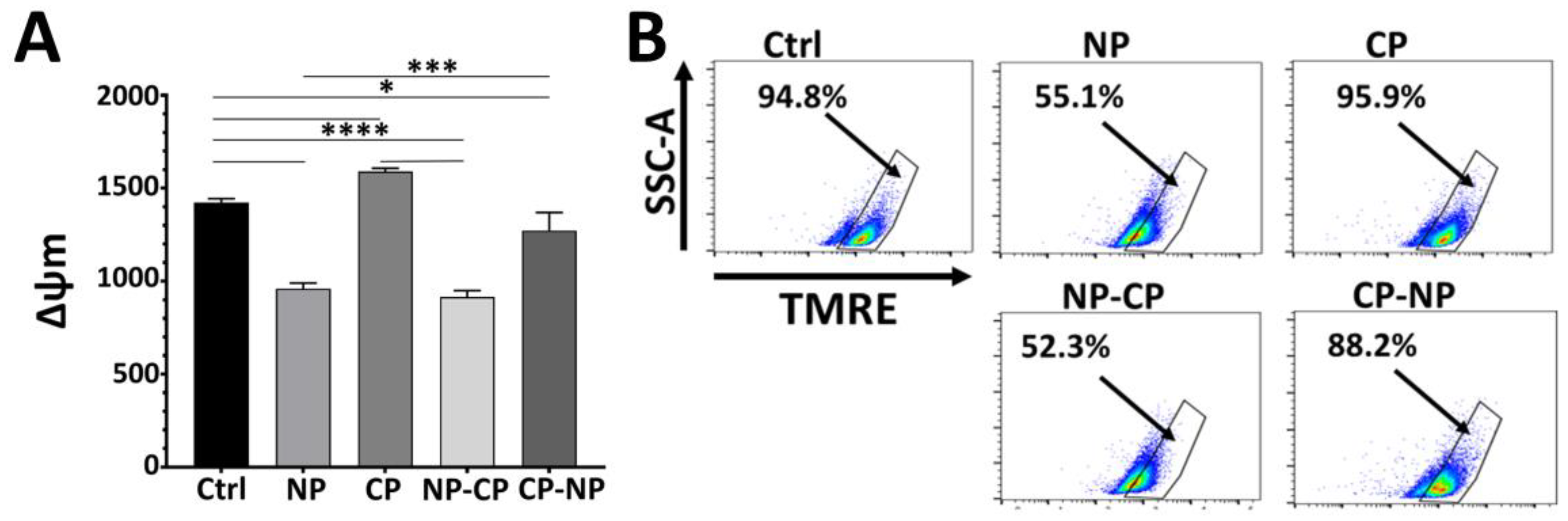

3.4. nsPEF Induces Mitochondrial Depolarization Whereas CAP Hyperpolarizes Mitochondria

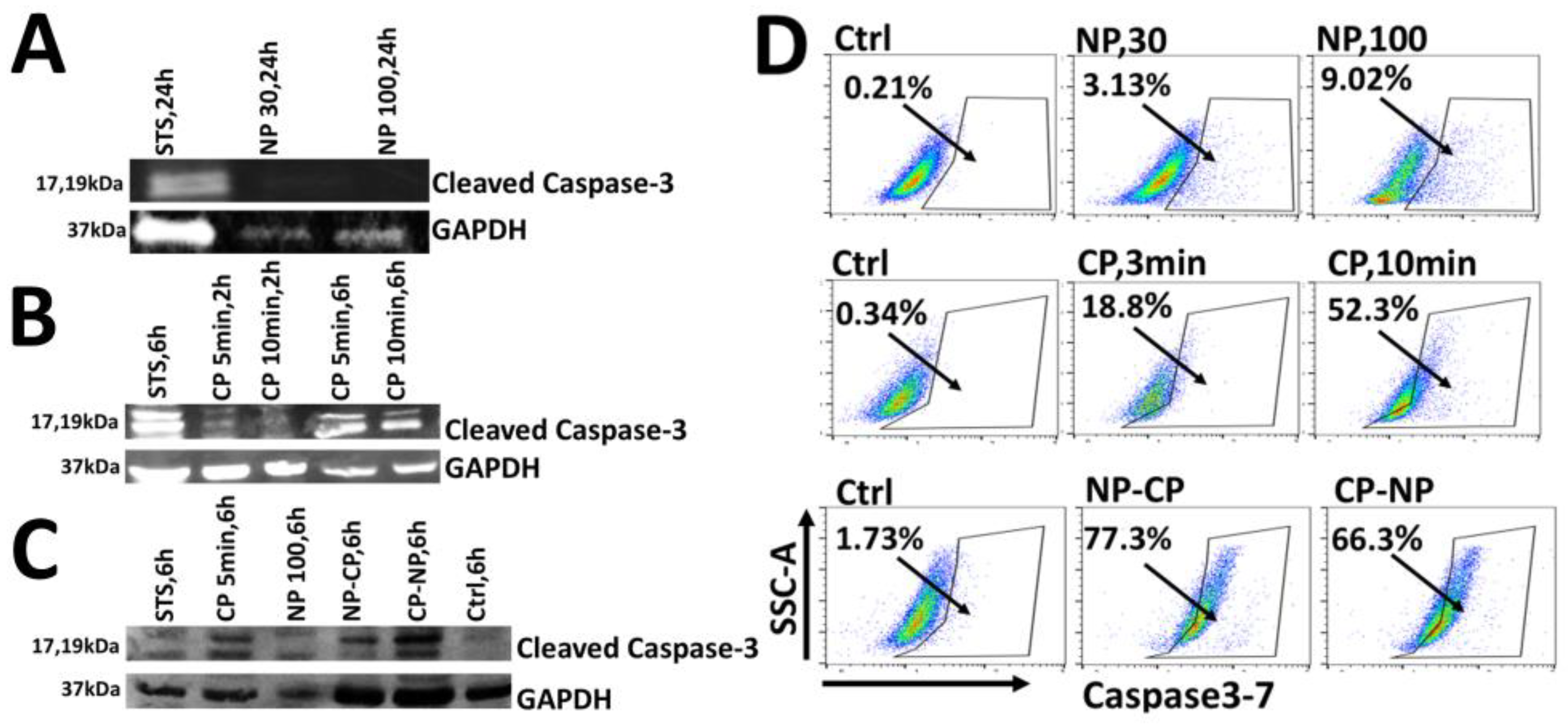

3.5. Enhanced Apoptosis Likely Contributes to Synergistic Cytotoxicity of nsPEF-CAP Combination Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silva, H.M. and R.C.A. Rosa, Pancreatic cancer in the era of precision medicine: challenges, advances, and the future of therapeutic strategies. Journal of the Egyptian National Cancer Institute, 2025. 37(1): p. 64. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H., et al., Pancreatic cancer: challenges and opportunities. BMC medicine, 2018. 16(1): p. 214. [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, A.A., et al., The evolution into personalized therapies in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: challenges and opportunities. Expert review of anticancer therapy, 2018. 18(2): p. 131–148. [CrossRef]

- Long, J., et al., Overcoming drug resistance in pancreatic cancer. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets, 2011. 15(7): p. 817–828. [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.S., et al., Feasibility and safety of endoscopic ultrasound-guided diffusing alpha emitter radiation therapy for advanced pancreatic cancer: Preliminary data. Endoscopy International Open, 2024. 12(10): p. E1085–E1091. [CrossRef]

- Rahib, L., T. Coffin, and B. Kenner, Factors Driving Pancreatic Cancer Survival Rates. Pancreas, 2024: p. 10.1097. [CrossRef]

- Sohal, D.P., et al., Metastatic pancreatic cancer: ASCO guideline update. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2020. 38(27): p. 3217–3230. [CrossRef]

- Nuccitelli, R. and A. McDaniel, Nano-Pulse Stimulation Therapy in Oncology. Bioelectricity, 2024. 6(2): p. 72–79. [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, A., et al., Nano-pulse stimulation™ therapy (NPS™) is superior to cryoablation in clearing murine melanoma tumors. Frontiers in Oncology, 2023. 12: p. 948472. [CrossRef]

- Pastori, C., et al., Neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy is improved with a novel pulsed electric field technology in an immune-cold murine model. Plos one, 2024. 19(3): p. e0299499. [CrossRef]

- Beebe, S.J., Mechanisms of Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Field (NsPEF)-induced cell death in cells and tumors. Journal of Nanomedicine Research, 2015. 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Nuccitelli, R., et al., Nanosecond pulsed electric fields cause melanomas to self-destruct. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 2006. 343(2): p. 351–360. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S., et al., The role of reactive oxygen species in the immunity induced by nano-pulse stimulation. Scientific reports, 2021. 11(1): p. 23745. [CrossRef]

- Yao, C., et al., Simulation and experimental study on the responses of subcellular structures in tumor cells induced by 5 ns pulsed electric fields. Applied Sciences, 2023. 13(14): p. 8142. [CrossRef]

- Beebe, S.J., et al., Transient features in nanosecond pulsed electric fields differentially modulate mitochondria and viability. PLoS One, 2012. 7(12): p. e51349. [CrossRef]

- Beebe, S.J., N.M. Sain, and W. Ren, Induction of cell death mechanisms and apoptosis by nanosecond pulsed electric fields (nsPEFs). Cells, 2013. 2(1): p. 136–162. [CrossRef]

- Schoenbach, K.H., S.J. Beebe, and E.S. Buescher, Intracellular effect of ultrashort electrical pulses. Bioelectromagnetics: Journal of the Bioelectromagnetics Society, The Society for Physical Regulation in Biology and Medicine, The European Bioelectromagnetics Association, 2001. 22(6): p. 440–448.

- Zaklit, J., et al., 2-ns Electrostimulation of Ca2+ influx into chromaffin cells: Rapid modulation by field reversal. Biophysical journal, 2021. 120(3): p. 556–567. [CrossRef]

- Semenov, I., S. Xiao, and A.G. Pakhomov, Primary pathways of intracellular Ca2+ mobilization by nanosecond pulsed electric field. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes, 2013. 1828(3): p. 981–989. [CrossRef]

- Craviso, G.L., et al., Nanosecond electric pulses: a novel stimulus for triggering Ca2+ influx into chromaffin cells via voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Cellular and molecular neurobiology, 2010. 30(8): p. 1259–1265. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S., et al., Nano-pulse stimulation for the treatment of pancreatic cancer and the changes in immune profile. Cancers, 2018. 10(7): p. 217. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., et al., Corrigendum: Antitumor effect and immune response of nanosecond pulsed electric fields in pancreatic cancer. Frontiers in Oncology, 2022. 12: p. 1052763. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A., et al., Mechanisms and immunogenicity of nsPEF-induced cell death in B16F10 melanoma tumors. Scientific Reports, 2019. 9(1): p. 431. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z., et al., Nanosecond pulsed electric field induces an antitumor effect in triple-negative breast cancer via CXCL9 axis dependence in mice. Cancers, 2023. 15(7): p. 2076. [CrossRef]

- Nuccitelli, R., et al., Nanoelectroablation of murine tumors triggers a CD8-dependent inhibition of secondary tumor growth. PLoS one, 2015. 10(7): p. e0134364. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.-y., et al., Anti-tumor effects of nanosecond pulsed electric fields in a murine model of pancreatic cancer. Bioelectrochemistry, 2025. 161: p. 108803. [CrossRef]

- Szlasa, W., et al., Nanosecond pulsed electric field suppresses growth and reduces multi-drug resistance effect in pancreatic cancer. Scientific Reports, 2023. 13(1): p. 351. [CrossRef]

- Yan, D., et al., Multi-modal biological destruction by cold atmospheric plasma: capability and mechanism. Biomedicines, 2021. 9(9): p. 1259. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C., et al., Modulation of ROS in nanosecond-pulsed plasma-activated media for dosage-dependent cancer cell inactivation in vitro. Physics of Plasmas, 2020. 27(11). [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C., et al., Synergistic effects of an atmospheric-pressure plasma jet and pulsed electric field on cells and skin. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science, 2021. 49(11): p. 3317–3324. [CrossRef]

- Oshin, E.A., et al., Synergistic effects of nanosecond pulsed plasma and electric field on inactivation of pancreatic cancer cells in vitro. Scientific reports, 2024. 14(1): p. 885. [CrossRef]

- Hamza, I.A., et al., Cold atmospheric plasma: a sustainable approach to inactivating viruses, bacteria, and protozoa with remediation of organic pollutants in river water and wastewater. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2023. 30(54): p. 116214–116226. [CrossRef]

- Fridman, G., et al., Applied plasma medicine. Plasma processes and polymers, 2008. 5(6): p. 503–533. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.-y., M.G. Kong, and Y.-m. Xia, Cold atmospheric plasma ameliorates skin diseases involving reactive oxygen/nitrogen species-mediated functions. Frontiers in Immunology, 2022. 13: p. 868386. [CrossRef]

- Jo, A., et al., Plasma-activated medium induces ferroptosis by depleting FSP1 in human lung cancer cells. Cell death & disease, 2022. 13(3): p. 212.

- Yang, X., et al., Cold atmospheric plasma induces GSDME-dependent pyroptotic signaling pathway via ROS generation in tumor cells. Cell death & disease, 2020. 11(4): p. 295.

- Kniazeva, V., et al., Adjuvant composite cold atmospheric plasma therapy increases antitumoral effect of doxorubicin hydrochloride. Frontiers in Oncology, 2023. 13: p. 1171042. [CrossRef]

- Semmler, M.L., et al., Molecular mechanisms of the efficacy of cold atmospheric pressure plasma (CAP) in cancer treatment. Cancers, 2020. 12(2): p. 269. [CrossRef]

- Min, T., et al., Therapeutic effects of cold atmospheric plasma on solid tumor. Frontiers in Medicine, 2022. 9: p. 884887. [CrossRef]

- Canady, J., et al., The first cold atmospheric plasma phase I clinical trial for the treatment of advanced solid tumors: a novel treatment arm for cancer. Cancers, 2023. 15(14): p. 3688. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., et al., Cold atmospheric plasma discharged in water and its potential use in cancer therapy. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 2016. 50(1): p. 015208. [CrossRef]

- Partecke, L.I., et al., Tissue tolerable plasma (TTP) induces apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. BMC cancer, 2012. 12(1): p. 473. [CrossRef]

- Honnorat, B., Application of cold plasma in oncology, multidisciplinary experiments, physical, chemical and biological modeling. 2018, Sorbonne Université.

- Yan, D., J. Sherman, and M. Keidar, Cold atmospheric plasma, a novel promising anti-cancer treatment modality. Oncotarget 8: 15977–15995. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Pouvesle, J.-M., et al. Plasma/target interactions in biomedical applications of cold atmospheric pressure plasmas. in PSE 2018. 2018.

- Metelmann, P., et al., Clinical studies applying physical plasma in head and neck cancer-key points and study design. Int. J. Clin. Res. Trials, 2016. 1: p. 103. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, C.M., J.F. Kolb, and S. Bekeschus, Combined in vitro toxicity and immunogenicity of cold plasma and pulsed electric fields. Biomedicines, 2022. 10(12): p. 3084. [CrossRef]

- Pakhomova, O.N., et al., Oxidative effects of nanosecond pulsed electric field exposure in cells and cell-free media. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics, 2012. 527(1): p. 55–64. [CrossRef]

- Nuccitelli, R., et al., Nanosecond pulsed electric field stimulation of reactive oxygen species in human pancreatic cancer cells is Ca2+-dependent. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 2013. 435(4): p. 580–585. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., J. Kim, and J.-S. Bae, ROS homeostasis and metabolism: a critical liaison for cancer therapy. Experimental & molecular medicine, 2016. 48(11): p. e269–e269.

- Noh, J., et al., Amplification of oxidative stress by a dual stimuli-responsive hybrid drug enhances cancer cell death. Nature communications, 2015. 6(1): p. 6907. [CrossRef]

- Pourahmad, J., A. Salimi, and E. Seydi, Role of oxygen free radicals in cancer development and treatment, in Free radicals and diseases. 2016, IntechOpen.

- Policastro, L.L., et al., The tumor microenvironment: characterization, redox considerations, and novel approaches for reactive oxygen species-targeted gene therapy. Antioxidants & redox signaling, 2013. 19(8): p. 854–895.

- Xu, D., et al., In situ OH generation from O2− and H2O2 plays a critical role in plasma-induced cell death. PloS one, 2015. 10(6): p. e0128205. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J. and T. Chung, Cold atmospheric plasma jet-generated RONS and their selective effects on normal and carcinoma cells. Scientific reports, 2016. 6(1): p. 20332. [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.H., et al., Non-thermal atmospheric pressure plasma induces selective cancer cell apoptosis by modulating redox homeostasis. Cell Communication and Signaling, 2024. 22(1): p. 452. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C., et al., Cold atmospheric plasma causes a calcium influx in melanoma cells triggering CAP-induced senescence. Scientific reports, 2018. 8(1): p. 10048. [CrossRef]

- Iuchi, K., et al., Cold atmospheric nitrogen plasma induces metal-initiated cell death by cell membrane rupture and mitochondrial perturbation. Cell Biochemistry and Function, 2023. 41(6): p. 687–695. [CrossRef]

- Yan, D., J.H. Sherman, and M. Keidar, Cold atmospheric plasma, a novel promising anti-cancer treatment modality. Oncotarget, 2016. 8(9): p. 15977. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G., et al., Dynamics of singlet oxygen-triggered, RONS-based apoptosis induction after treatment of tumor cells with cold atmospheric plasma or plasma-activated medium. Scientific reports, 2019. 9(1): p. 13931. [CrossRef]

- Gianulis, E.C., et al., Electroporation of mammalian cells by nanosecond electric field oscillations and its inhibition by the electric field reversal. Scientific reports, 2015. 5(1): p. 13818. [CrossRef]

- Dezest, M., et al., Mechanistic insights into the impact of Cold Atmospheric Pressure Plasma on human epithelial cell lines. Scientific reports, 2017. 7(1): p. 41163. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T., Numerical modelling of the effects of cold atmospheric plasma on mitochondrial redox homeostasis and energy metabolism. Scientific reports, 2019. 9(1): p. 17138. [CrossRef]

- Ricci, J.-E., et al., Disruption of mitochondrial function during apoptosis is mediated by caspase cleavage of the p75 subunit of complex I of the electron transport chain. Cell, 2004. 117(6): p. 773–786. [CrossRef]

- Asadipour, K., et al., Data Supporting Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Fields Modulate Electron Transport in in the Plasma Membrane and Mitochondria. Available at SSRN 4489182.

- Vernier, P.T., et al., Nanopore formation and phosphatidylserine externalization in a phospholipid bilayer at high transmembrane potential. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2006. 128(19): p. 6288–6289. [CrossRef]

- Vernier, P.T., Y. Sun, and M.A. Gundersen, Nanoelectropulse-driven membrane perturbation and small molecule permeabilization. BMC cell biology, 2006. 7(1): p. 37. [CrossRef]

- Asadipour, K., et al., Nanosecond pulsed electric fields (nsPEFs) modulate electron transport in the plasma membrane and the mitochondria. Bioelectrochemistry, 2024. 155: p. 108568. [CrossRef]

- Semenov, I., S. Xiao, and A. Pakhomov, Non-Ligand Mobilization of Intracellular Free Calcium by Nanosecond Pulsed Electric Field (NsPEF). Biophysical Journal, 2013. 104(2): p. 617a. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).