1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In Mexico, coronary artery disease (CAD) is the primary cause of death among the general population [

1]. The occlusion of coronary arteries results in irreversible myocardial injury, and timely recognition of this event is fundamental to initiate reperfusion therapies for myocardial infarction (MI). These interventions aim to salvage viable myocardium, preserve systolic cardiac function, and limit infarct size. However, ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury commonly occurs during these procedures, and the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms remain incompletely understood [

2]. Despite the use of reperfusion strategies, no effective therapy currently exists to prevent myocardial I/R injury. Without further medical innovation, it is estimated that by 2030, more than 23.6 million people will die annually from CVD [

3]. In Mexico, only 5 out of 10 patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) have access to reperfusion therapy [

4].

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), defined as RNA transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides, play crucial regulatory roles at the epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional levels. This class of non-coding RNAs has been increasingly associated with the pathophysiology of CVD, including MI. The distinct expression profiles of lncRNAs in various cardiovascular conditions offer significant promise as both biomarkers and therapeutic targets [

5]. Among these, the lncRNA maternally expressed gene 3 (

MEG3), an imprinted gene within the DLK-MEG3 locus located on chromosome 14q32.3, is highly conserved and enriched in human cardiac tissue [

6]. MEG3 regulates multiple biological processes and is particularly relevant in cardiac fibroblasts, where it promotes fibrosis, making it the most specific lncRNA marker for this cell type [

7]. Furthermore, MEG3 expression induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis and is significantly upregulated in the left ventricle after MI compared with healthy cardiac tissue [

8].

MEG3 also functions as a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA), sequestering microRNAs to regulate downstream mRNA expression. One of its key target is microRNA-214 (miR-214), which it directly binds and inhibits. miR-214, in turn, targets activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), a key effector component of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathway. ATF4 controls the expression of genes involved in oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis [

9]. Importantly, ATF4 has been shown to mitigate myocardial ER stress and reduce apoptosis during I/R injury [

10].

This study aims to investigate the relationship between STEMI and the expression levels of MEG3 and ATF4 in STEMI patients using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR).

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients at Hospital Admission

During the study period, 42 patients with STEMI were hospitalized, the median age of STEMI patients was 54 years (49–58), and the majority were male (86%). The median length of hospital stay was 5 days (3–7). Additionally, blood samples were obtained from 24 healthy controls (83% male; median age 55 years, 51–60).

The most relevant clinical and demographic characteristics of STEMI patients included a high prevalence of active smoking (72%) and comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus (39%) and hypertension (37%). Laboratory findings at admission revealed leukocytosis and elevated levels of N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), cardiac troponin T (cTnT), creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) (

Table 1).

2.2. Laboratory Data

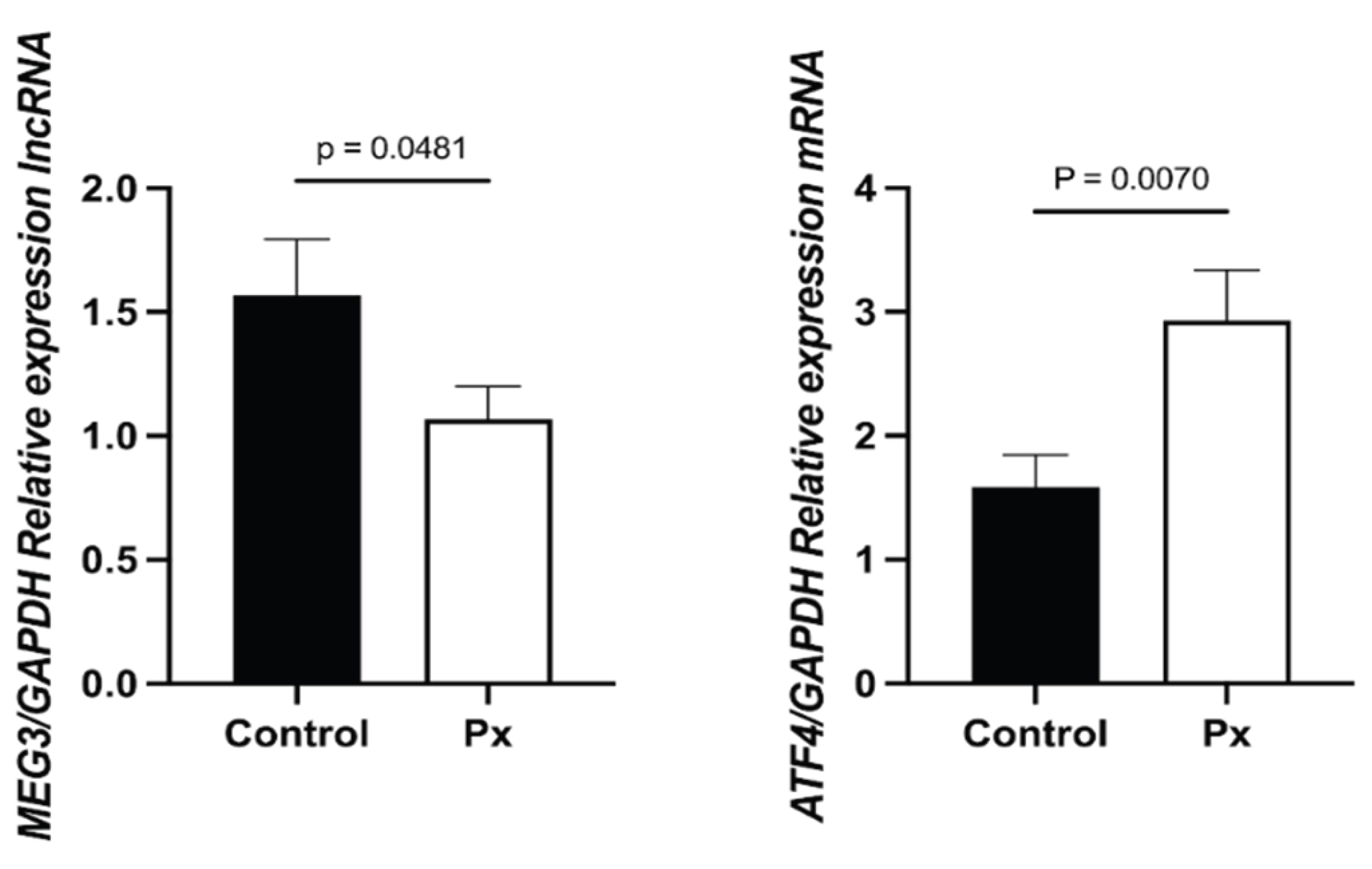

The expression of MEG3 was significantly lower in STEMI patients compared to healthy controls (1.0489, 0.0489–2.0054 vs. 2.3849, 1.9950–2.5652; p = 0.048). In contrast, ATF4 expression was significantly higher in STEMI patients (2.4032, 1.0000–4.3019 vs. 2.2407, 1.6362–3.1327; p = 0.0070) (

Figure 1).

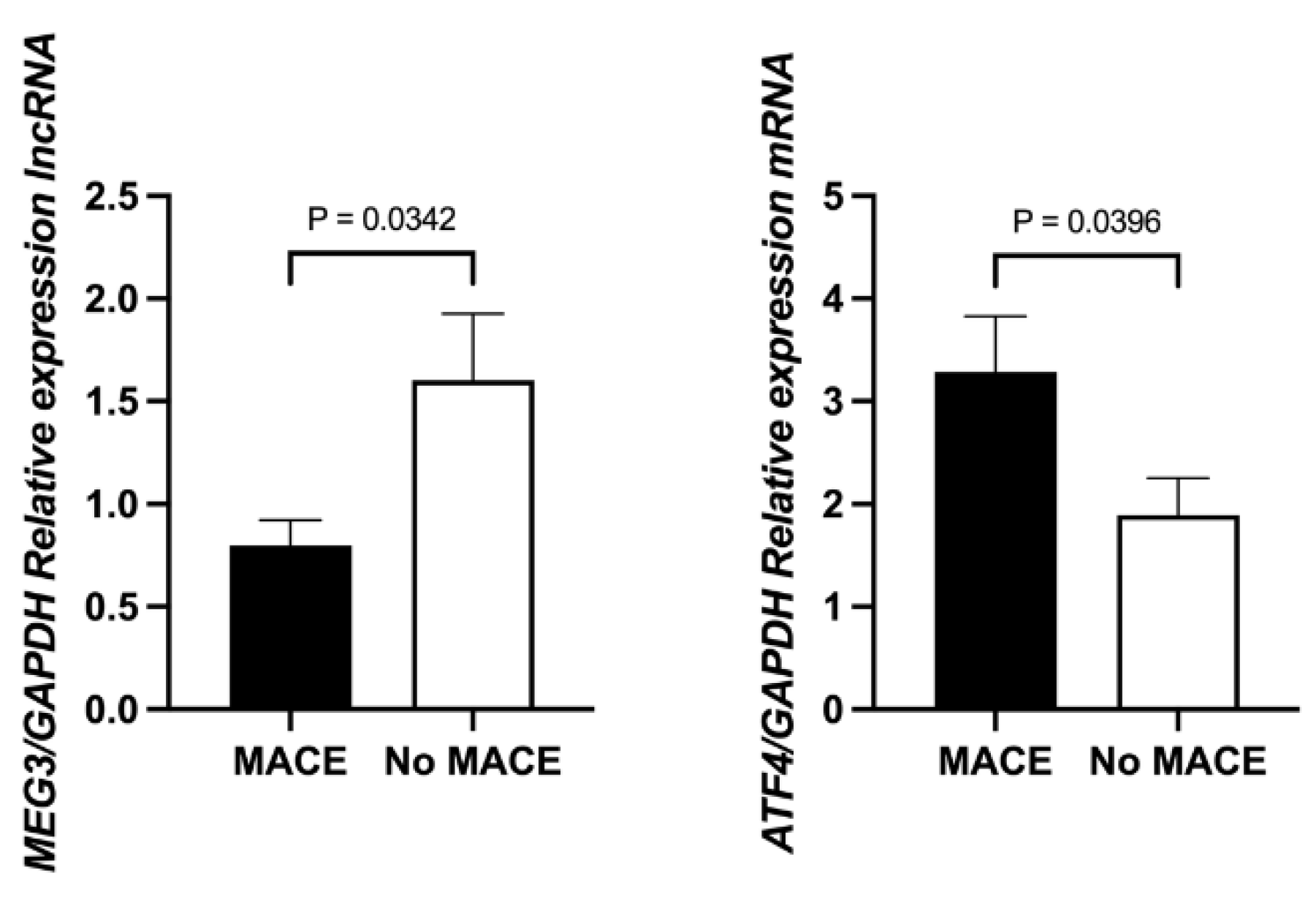

Further subgroup analysis revealed that MEG3 expression was significantly lower in STEMI patients who experienced MACE compared to those who did not (0.8974, 0.4186–1.4131 vs. 1.2259, 0.5516–2.3964; p = 0.0342). Conversely, ATF4 expression was significantly higher in the MACE group (2.8950, 0.7559–4.3287 vs. 2.3498, 1.0821–3.6903; p = 0.0396) (

Figure 2).

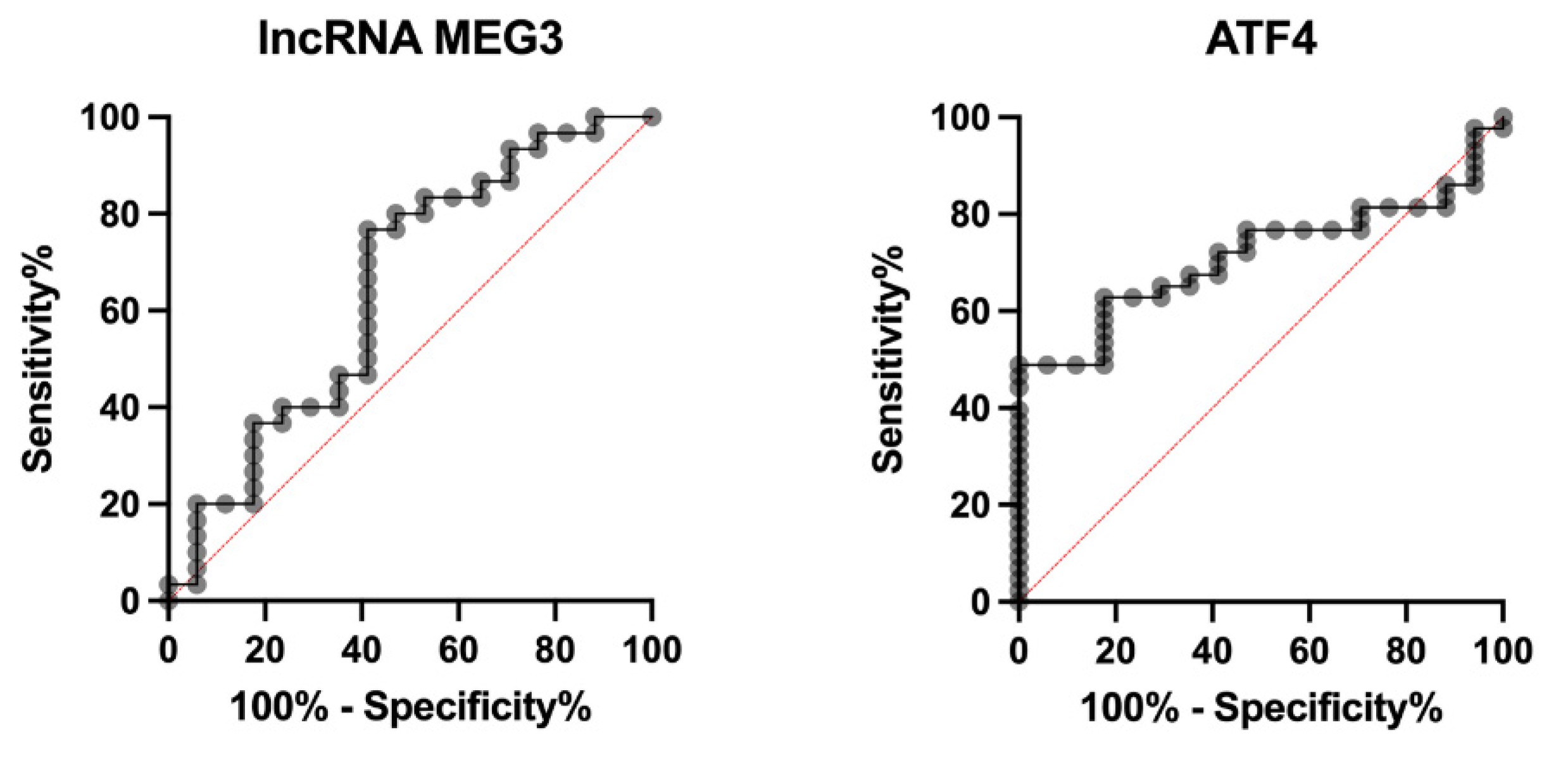

ROC curve analysis was performed to assess the predictive potential of MEG3 and ATF4 for MACE. MEG3 showed a modest discriminative ability, with an AUC of 0.6490 (0.4760 to 0.8221; p = 0.0924). The optimal cut-off value was < 0.3201 based on the Youden index. ATF4 demonstrated slightly better discriminative performance, with an AUC of 0.7127 (0.5862 to 0.8393; p = 0.0107) and an optimal cut-off value of > 0.003391 (

Figure 3).

Finally, correlation analyses revealed that MEG3 expression was positively associated with CK-MB levels (r = 0.3978, 0.0630 to 0.6520; p = 0.0219). ATF4 expression was positively correlated with cTnT (r = 0.3328, 0.0284 to 0.5810; p = 0.0335) and inversely correlated with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF; r = –0.4283, –0.6503 to –0.1390; p = 0.0052). Moreover, a significant positive correlation was observed between MEG3 and ATF4 expression levels (r = 0.4048, 0.1425 to 0.6140; p = 0.0035) (

Table 2).

3. Discussion

Our results demonstrate a significant reduction in MEG3 expression in patients with STEMI compared to healthy controls. Moreover, within the MI cohort, MEG3 expression was markedly lower in patients who experienced MACE than in those without such events.

These findings contrast with a recent study reporting increased

MEG3 expression in patients with acute MI compared to with non-acute presentations [

11]. Similarly, Liu et al. found that

MEG3 expression was positively correlated with serum levels of CK-MB and cardiac troponin I [

12]. Mechanistically,

MEG3 silencing has been shown to exert cardioprotective effects by attenuating apoptosis and autophagy, primarily through the regulation of GRP78, ATF4, and CHOP expression [

13]. In addition, the downregulation of

MEG3 has been reported to alleviate hypoxia-induced cardiomyocyte injury via modulation of miR-325-3p [

13]. In light of this evidence, the decreased

MEG3 expression observed in our STEMI patients may represent a compensatory response aimed at limiting myocardial damage via suppression of pro-apoptotic and pro-autophagic signaling pathways [

14].

We also observed a significant increase in

ATF4 expression in STEMI patients relative to healthy controls. Notably,

ATF4 levels were elevated in patients who developed MACE, and correlated positively with cTnT and inversely with LVEF, suggesting a potential role in the severity of myocardial injury. Experimental models have consistently shown that ATF4 plays a critical role in I/R injury. For example, suppression of ATF4—via WTAP knockdown [

15], melatonin administration [

16], or treatment with empagliflozin [

17]—has been shown to mitigate myocardial apoptosis, autophagy, and cardiac tissue damage. However, contrasting evidence exists. Cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of

Atf4 in mice has been shown to exacerbate cardiac dysfunction, fibrosis, and apoptosis, suggesting that ATF4 may serve a dual function, both balancing cellular stress responses and maintaining cardiac homeostasis [

18].

Interestingly, our study also identified a positive correlation between

MEG3 and

ATF4 expression, despite the overall downregulation of

MEG3 in STEMI patients. This finding is consistent with prior studies indicating that

MEG3 may positively regulate ATF4 by repressing miR-214, a microRNA known to negatively regulate ATF4 [

19]. This interaction supports the existence of a complex

MEG3–ATF4 regulatory axis, which may influence the balance between injury and repair processes during myocardial infarction.

A key strength of this study is its focus on human subjects, thereby extending prior findings derived primarily from animal models. In addition, the study reached sufficient statistical power for most comparisons. Nonetheless, some limitations should be acknowledged. The relatively small sample size may reduce the robustness of subgroup analyses and limit generalizability. Moreover, incomplete processing of the entire MEG3–ATF4 regulatory pathway (AXIS) may have impacted the interpretation of our results.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted between July 2023 to August 2024 at the Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez in Mexico City, a tertiary academic center specializing in the study and management of cardiovascular diseases.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) first-time diagnosis of STEMI, (2) hemodynamic stability at the time of hospital admission, and (3) infarction localized primarily to the anterior wall. Exclusion criteria comprised the presence of clinical infection, active malignancy, or autoimmune disease. In addition, a group of healthy blood donors was included as reference controls.

4.2. Diagnosis of ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction

STEMI was defined according to international guidelines as an ST-segment elevation of >1 mm in at least two contiguous leads on electrocardiography, in the presence of ischemic symptoms and elevated high-sensitivity cardiac troponin levels [

20].

4.3. Diagnosis of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events

Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) were defined in our study as a composite outcome including reinfarction, angina, heart failure, stroke, or death.

4.4. Laboratory Procedures

Blood samples were collected at Coronary Care Unit admission. Total RNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples using TRIzol LS Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 400 µL of whole blood was mixed with 700 µL of TRIzol reagent. After adding 140 µL of chloroform, the mixture was shaken vigorously for 15 seconds, incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes, and centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 15 minutes. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube, and an equal volume of isopropanol was added. After a 30-minute incubation, the mixture was centrifuged again under the same conditions. The resulting RNA pellet was washed twice with 1,000 µL of 75% ethanol and centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 10 minutes. The pellet was then air-dried and resuspended in DEPC-treated water. RNA quality was assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer, NanoDrop 2000 Thermo-Scientific (USA), and purity was confirmed by a 260/280 absorbance ratio between 1.8 and 2.0.

cDNA synthesis was performed using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Cat. No. 205313, QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), and qPCR was carried out using the QuantiNova SYBR Green PCR Kit (Cat. No. 216915, QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocols using CFX Opus 96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, California, USA),. Primer sequences were pre-designed by QIAGEN for the following targets: MEG3 (RT² lncRNA qPCR Assay, Cat. No. SBH0448235) and ATF4 (Cat. No. QT00074466). Gene expression levels were quantified using the 2ΔΔCT method, with Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the reference gene.

4.5. Ethical Approval

All participants provided written informed consent authorizing the use of their clinical data and biological samples for research purposes. The study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez (Protocol No. 23-1377). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and its subsequent amendments.

4.6. Statistical Analyses

Categorical variables were described as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were expressed as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Differences between medians were evaluated using the unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. Correlations were assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

The predictive value of MEG3 and ATF4 expression levels for STEMI was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The area under the curve (AUC) was reported with 95% CI, and the optimal cut-off point was determined using the Youden index.

All analyses were two-tailed, and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our results suggest that dysregulation of the lncRNA MEG3 and the transcription factor ATF4 is a characteristic feature of STEMI and is associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Specifically, MEG3 expression is reduced while ATF4 is increased in STEMI patients, and both molecules show significant correlations with biomarkers of myocardial injury and functional impairment.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, A.H.-D.; methodology, FJR-U, Y.J.-V, LMA-G, AH-D.; software, AH-D, LMA-G, FJR-U; validation, FJR-U, DS-L, Y.J.-V, MB-P, AA-M, HG-P, M-C, LMA-G., and AH,D.; formal analysis, AH-D, LMA-G, FJR-U.; investigation, FJR-U, AH-D.; resources, AH-D.; data curation, FJR-U, AH-D ; writing—original draft preparation, FJR-U; writing—review and editing, FJR-U, AH-D, LMA-G .visualization, AH-D.; supervision, LMA-G, AH-D.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of the Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez (protocol code: 23-1377 and date of approval: May 25, 2023).” for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ATF4 |

Activating transcription factor 4 |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CAD |

Coronary artery disease |

| ceRNA |

Competitive endogenous RNA |

| CHOP |

C/EBP homologous protein |

| CK-MB |

Creatine kinase–MB |

| cTnT |

Cardiac troponin T |

| CRP |

C-reactive protein |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular disease |

| DBP |

Diastolic blood pressure |

| DEPC |

Diethyl pyrocarbonate |

| ER |

Endoplasmic reticulum |

| GAPDH |

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GRACE |

Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events |

| GRP78 |

Glucose-regulated protein 78 |

| hsCRP |

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| I/R |

Ischemia/reperfusion |

| lncRNA |

Long non-coding RNA |

| LVEF |

Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| MACE |

Major adverse cardiovascular events |

| MEG3 |

Maternally expressed gene 3 |

| MI |

Myocardial infarction |

| miR-214 |

MicroRNA-214 |

| NT-proBNP |

N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide |

| RPLP0 |

Ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0 |

| SBP |

Systolic blood pressure |

| STEMI |

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| TIMI |

Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction |

| WTAP |

Wilms tumor 1–associating protein |

References

- INEGI ESTADÍSTICAS DE DEFUNCIONES REGISTRADAS. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/boletines/2024/EDR/EDR2023_En-Jn.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Collins, L.; Binder, P.; Chen, H.; Wang, X. Regulation of Long Non-Coding RNAs and MicroRNAs in Heart Disease: Insight Into Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 543573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Benjamin, E.J.; Go, A.S.; Arnett, D.K.; Blaha, M.J.; Cushman, M.; De Ferranti, S.; Després, J.P.; Fullerton, H.J.; Howard, V.J.; et al. Executive Summary: Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2015 Update. Circulation 2015, 131, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Herrera, L.A.; Araiza-Garaygordobil, D.; Gopar-Nieto, R.; Raymundo-Martínez, G.I.; Loáisiga-Sáenz, A.; Villalobos-Flores, A.; Martínez-Ramos, M.; Torres-Araujo, L. V.; Pohls-Vázquez, R.; Luna-Herbert, A.; et al. Evaluation of Pharmacoinvasive Strategy versus Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction with ST Segment Elevation at the National Institute of Cardiology (PHASE-MX). Arch Cardiol Mex 2020, 90, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, L.T.T.; Nhu, C.X.T. The Role of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Cardiovascular Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Klibanski, A. MEG3 Noncoding RNA: A Tumor Suppressor. J Mol Endocrinol 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boon, R.A.; Hofmann, P.; Michalik, K.M.; Lozano-Vidal, N.; Berghäuser, D.; Fischer, A.; Knau, A.; Jaé, N.; Schürmann, C.; Dimmeler, S. Long Noncoding RNA Meg3 Controls Endothelial Cell Aging and Function: Implications for Regenerative Angiogenesis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 68, 2589–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Zhao, Z.A.; Liu, J.; Hao, K.; Yu, Y.; Han, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Lei, W.; Dong, N.; et al. Long Noncoding RNA Meg3 Regulates Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis in Myocardial Infarction. Gene Ther 2018, 25, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Wu, X.; Dai, Q.; Li, Z.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Yi, B.; Wang, J.; Liao, Q.; Zhang, W.; et al. Vitamin D Receptor Attenuate Ischemia-Reperfusion Kidney Injury via Inhibiting ATF4. Cell Death Discov 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, M.; Jin, Z.; Duan, W.; Zhao, G.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, W.; Wang, S.; et al. Melatonin Reduces PERK-EIF2α-ATF4-Mediated Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress during Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury: Role of RISK and SAFE Pathways Interaction. Apoptosis 2016, 21, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, B. The Expression Levels of Plasma Dimethylglycine (DMG), Human Maternally Expressed Gene 3 (MEG3), and Apelin-12 in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction and Their Clinical Significance. Ann Palliat Med 2021, 10, 2175–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LIU, C.-T.; WENG, Z.-Y.; ZHENG, Z.-H. Plasma Expression Levels of MEG3 and UCA1 in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction and Their Clinical Significance. Chinese Journal of cardiovascular Rehabilitation Medicine 2019, 285–289. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Geng, J.; Chen, F.; Wei, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Gao, L.; et al. Long Non-Coding RNA MEG3 Knockdown Attenuates Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Apoptosis by Targeting P53 Following Myocardial Infarction. J Cell Mol Med 2019, 23, 8369–8380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, S.; Huang, F.; Jiao, M.; Qian, Z.; Han, M.; Miao, Z.; Zhan, H. Inhibition of MEG3 Ameliorates Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis and Autophagy by Regulating the Expression of MiRNA-129-5p in a Mouse Model of Heart Failure. Redox Rep 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, C.; Yang, F.; Jiang, N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; et al. WTAP Promotes Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Increasing Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress via Regulating M6A Modification of ATF4 MRNA. Aging 2021, 13, 11135–11149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, M.; Jin, Z.; Duan, W.; Zhao, G.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, W.; Wang, S.; et al. Melatonin Reduces PERK-EIF2α-ATF4-Mediated Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress during Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury: Role of RISK and SAFE Pathways Interaction. Apoptosis 2016, 21, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.C.; Li, Y.; Qian, X.Q.; Zhao, H.; Wang, D.; Zuo, G.X.; Wang, K. Empagliflozin Alleviates Myocardial I/R Injury and Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis via Inhibiting ER Stress-Induced Autophagy and the PERK/ATF4/Beclin1 Pathway. J Drug Target 2022, 30, 858–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, G.; Dasgupta, S.; Niewold, E.L.; Li, C.; Li, Q.; Luo, X.; Tan, L.; Ferdous, A.; Lorenzi, P.L.; et al. ATF4 Protects the Heart From Failure by Antagonizing Oxidative Stress. Circ Res 2022, 131, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yang, G.; Wang, W. LncRNA MEG3 Promotes Hepatic Insulin Resistance by Serving as a Competing Endogenous RNA of MiR-214 to Regulate ATF4 Expression. Int J Mol Med 2019, 43, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; Jaffe, A.S.; Chaitman, B.R.; Bax, J.J.; Morrow, D.A.; White, H.D.; Corbett, S.; Chettibi, M.; Hayrapetyan, H. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018) doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000617/ASSET/BF0CD03E-E6C8-406C-A29D-E9C464CB6A0A/ASSETS/GRAPHIC/E618FIG09.JPG. Circulation 2018, 138, e618–e651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).