Submitted:

15 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

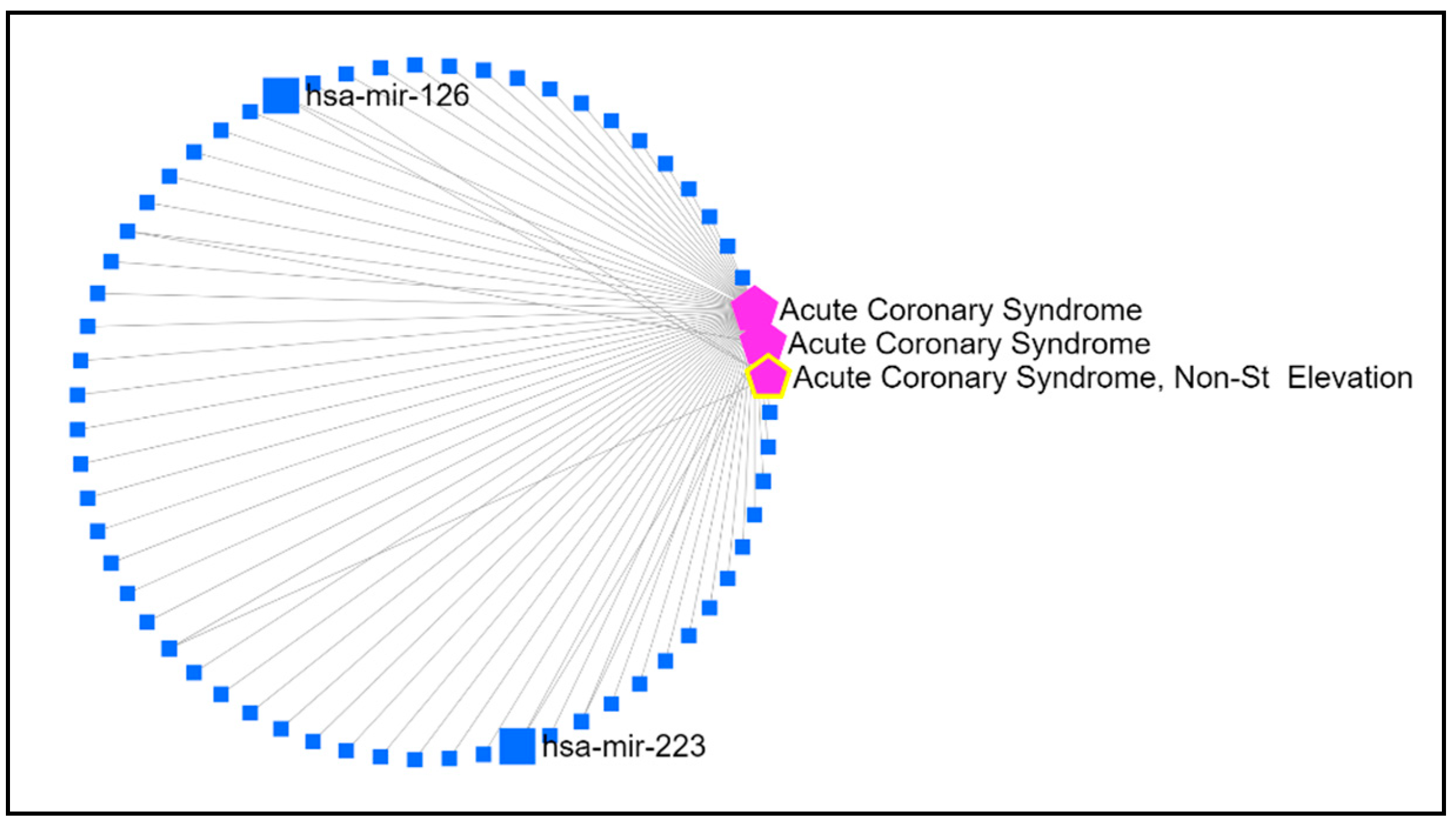

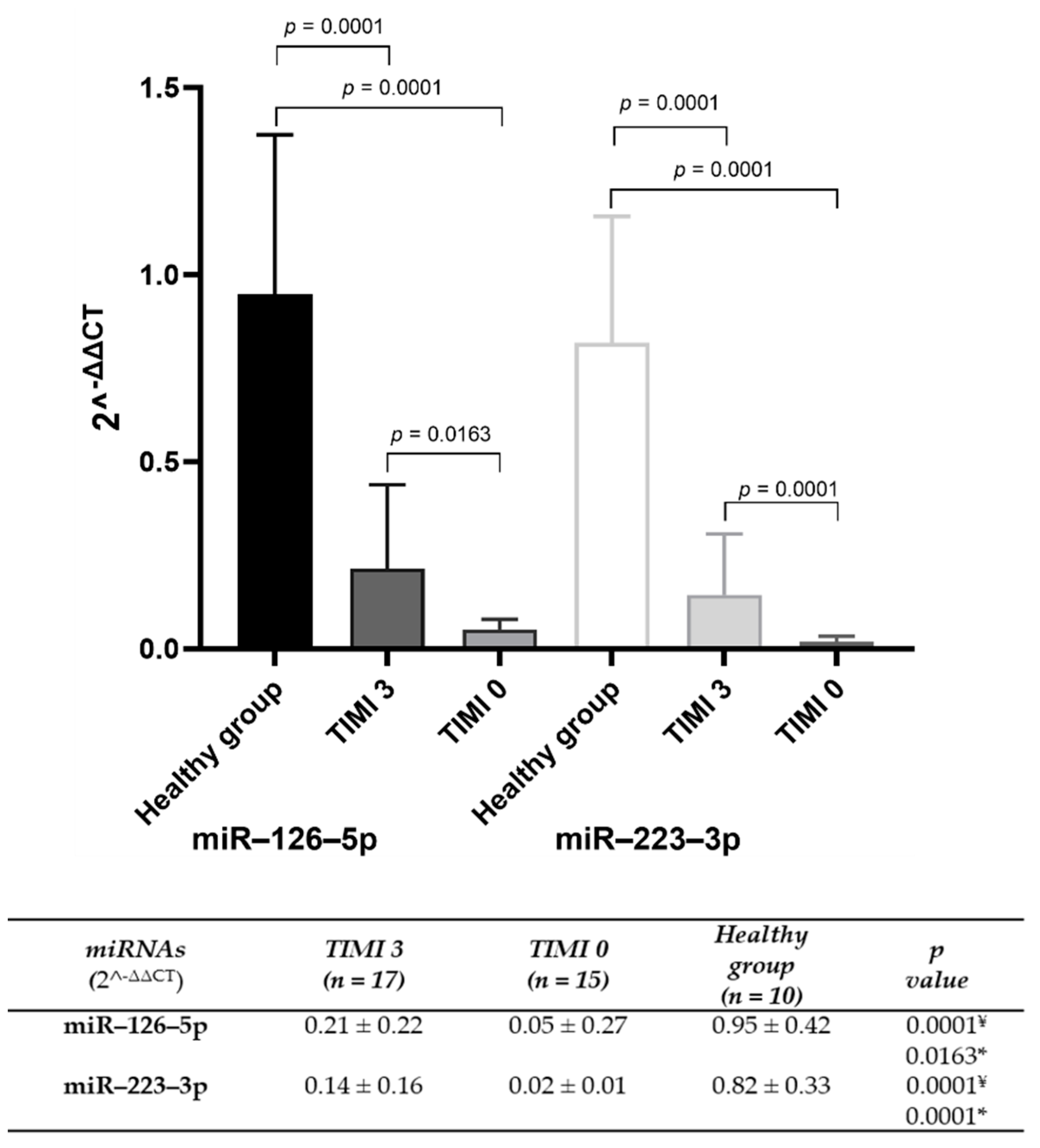

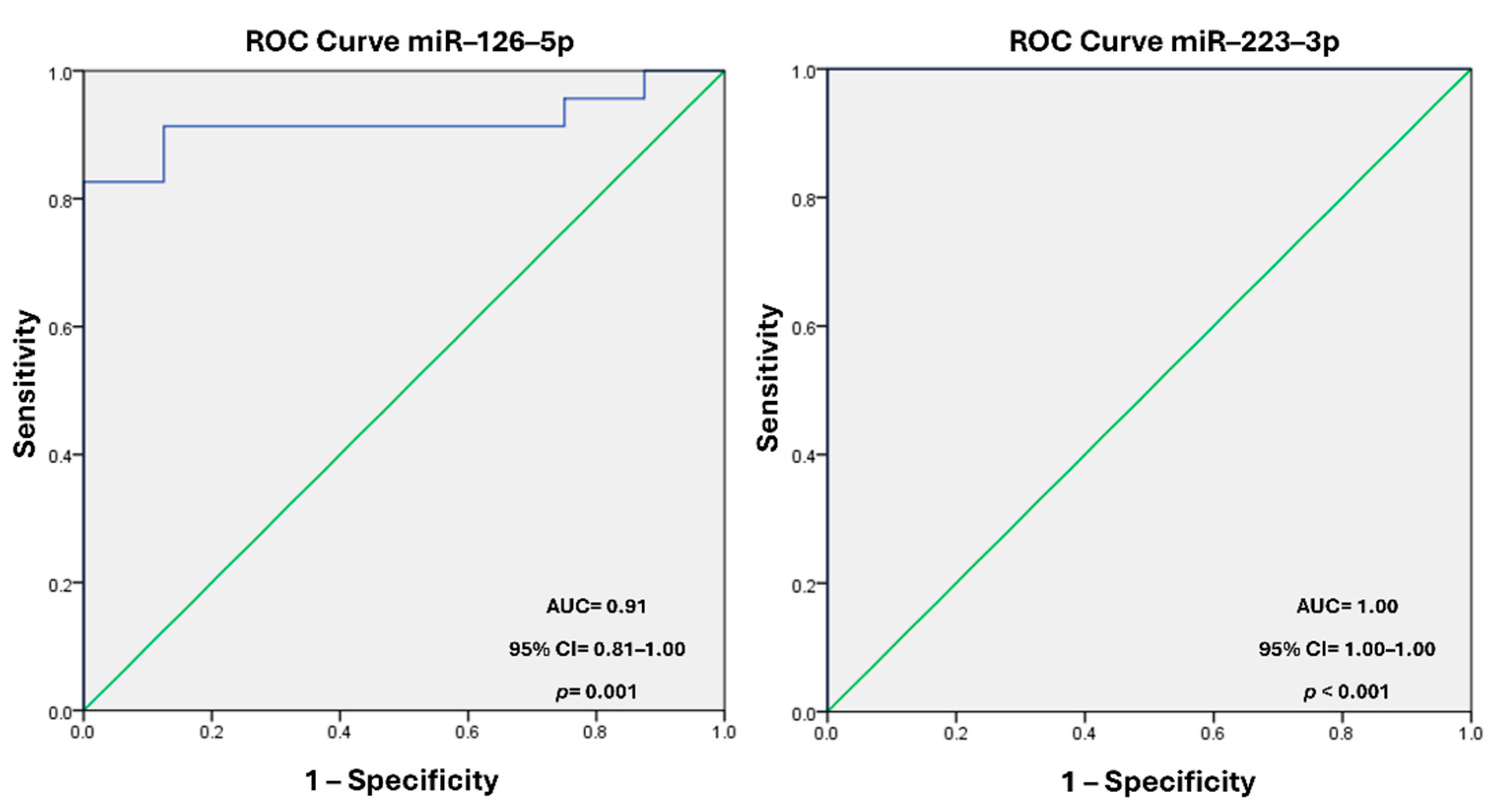

Background: The molecular mechanisms underlying acute coronary syndrome (ACS) have been extensively investigated, with a particular focus on the role of circulating microvesicles (MVs) as carriers of regulatory elements that influence hemodynamic changes and coronary flow. Endo-thelial and platelet dysfunction during ACS alters MVs composition, impacting clinical outcomes. This study explores the levels of miR–126–5p and miR–223–3p in circulating MVs and their asso-ciation with the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) coronary flow classification scale, proposing their potential as biomarkers. Methods. Bioinformatic tools identified miRNAs linked to ACS. Plasma MVs were isolated from ACS patients and healthy controls through high-speed centrifugation. miRNA levels were quantified using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and compared across TIMI 0 and TIMI 3 groups. Diagnostic efficacy was assessed via receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Results. The bioinformatic analysis identified miR–126 and miR–223 present in ACS. miR–126–5p and miR–223–3p were sig-nificantly reduced in MVs from TIMI 0 patients compared to TIMI 3. ROC analysis showed high diagnostic accuracy for miR–126–5p (AUC = 0.918; 95% CI: 0.818–1.00; p = 0.001) and miR–223–3p (AUC = 1.00; 95% CI: 1.00–1.00; p < 0.001). Conclusion. Reduced levels of miR–126–5p and miR–223–3p in circulating MVs are strongly associated with impaired coronary flow, positioning these miRNAs as potential biomarkers for ACS risk stratification and therapeutic targeting.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Microvesicles Extraction

2.3. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

2.4. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. MVs miRNAs Associated with ACS

3.2. Sociodemographic Data and Clinical Variables of Study Population

3.4. Diagnostic Value of miR–126–5p and miR–223–3p Levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2024, 13, 55-161. Erratum in: Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2024, 13, 455. [CrossRef]

- World health statistics 2023: monitoring health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Abd, M.E.; Bahgat, A.M.H.; Khaled, H.R; Ibrahim, S.F. Prediction of angiographic (TIMI GRADE) blood flow using the novel CHA2DS2-VASC-HSF score in patients with STEMI. Int. J. Cardiol. Sci. 2024, 6, 114-123. [CrossRef]

- Kievit, P.C; Brouwer, M.A.; Veen, G.; Karreman, A.J.; Verheugt, F.W.A. High-grade infarct-related stenosis after successful thrombolysis: strong predictor of reocclusion, but not of clinical reinfarction. Am Heart J 2004, 148, 826-833. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.M.; Cannon, C.P.; Murphy, S.A.; Ryan, K.A.; Mesley, R.; Marble, S.J.; McCabe, C.H.; van de Werf, F.; Braunwald, E. Relationship of TIMI myocardial perfusion grade to mortality after administration of thrombolytic drugs. Circulation 2000, 101, 125-30. [CrossRef]

- Stringer, K.A. TIMI grade flow, mortality, and the GUSTO-III trial. Pharmacotherapy 1998, 18, 699-705.

- Suzuki, M.; Enomoto, D.; Seike, F.; Fujita, S.; Honda, K. Clinical features of early myocardial rupture of acute myocardial infarction. Angiology 2012, 63, 453-456. [CrossRef]

- Tikiz, H.; Atak, R.; Balbay, Y.; Genç, Y.; Kütük, E. Left ventricular aneurysm formation after anterior myocardial infarction: clinical and angiographic determinants in 809 patients. Int J Cardiol 2002, 82, 7-14. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.M.; Pride, Y.B.; Buros, J.L.; Lord, E.; Shui, A.; Murphy, S.A.; Pinto, D.S.; Zimetbaum, P.J.; Sabatine, M.S.; Cannon, C.P.; et al; TIMI Study Group. Association of impaired thrombolysis in myocardial infarction myocardial perfusion grade with ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation following fibrinolytic therapy for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008, 51, 546-551. [CrossRef]

- Bates, E.R. Reperfusion therapy reduces the risk of myocardial rupture complicating ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e001368. [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.P. Importance of TIMI 3 flow. Circulation 2001, 104, 624-626. [CrossRef]

- Gersh, B.J. Current issues in reperfusion therapy. Am J Cardiol 1998, 82, 3-11. [CrossRef]

- Caffè, A.; Animati, F.M.; Iannaccone, G.; Rinaldi, R.; Montone, R.A. Precision Medicine in Acute Coronary Syndromes. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 4569. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, R.; Subbarayan, R.; Shrestha, R.; Chauhan, A.; Krishnamoorthy, L. Exploring platelet-derived microvesicles in vascular regeneration: unraveling the intricate mechanisms and molecular mediators. Mol Biol Rep 2024, 51, 393. [CrossRef]

- Taus, F.; Meneguzzi, A.; Castelli, M.; Minuz, P. Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Target of Antiplatelet Agents. What Is the Evidence? Front Pharmacol 2019, 10, 1256. [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 2009, 136, 215-233. [CrossRef]

- Katsioupa, M.; Kourampi, I.; Oikonomou, E.; Tsigkou, V.; Theofilis, P.; Charalambous, G.; Marinos, G.; Gialamas, I.; Zisimos, K.; Anastasiou, A.; et al. Novel Biomarkers and Their Role in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Acute Coronary Syndrome. Life (Basel) 2023, 13, 1992. [CrossRef]

- Tanase, D.M.; Gosav, E.M.; Ouatu, A.; Badescu, M.C.; Dima, N.; Ganceanu-Rusu, A.R.; Popescu, D.; Floria, M.; Rezus, E.; Rezus, C. Current Knowledge of MicroRNAs (miRNAs) in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS): ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI). Life (Basel) 2021, 11, 1057. [CrossRef]

- Federici, C.; Shahaj, E.; Cecchetti, S.; Camerini, S.; Casella, M.; Iessi, E.; Camisaschi, C.; Paolino, G.; Calvieri, S.; Ferro, S.; et al. Natural-Killer-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Immune Sensors and Interactors. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 262. [CrossRef]

- Melki, I.; Tessandier, N.; Zufferey, A.; Boilard, E. Platelet microvesicles in health and disease. Platelets 2017, 28, 214-221. [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Tan, J.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, Q. The role of microvesicles and its active molecules in regulating cellular biology. J Cell Mol Med 2019, 23, 7894-7904. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Han, W.Q.; Wu, H.Y.; Wang, Q.R.; Liu, X.H.; Xing, K.; Cheng, G.; Chang, F.J. Vascular damage effect of circulating microparticles in patients with ACS is aggravated by type 2 diabetes. Mol Med Rep 2021, 23, 474. [CrossRef]

- Zaldivia, M.T.K.; McFadyen, J.D.; Lim, B.; Wang, X.; Peter, K. Platelet-Derived Microvesicles in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front Cardiovasc Med 2017, 4, 74. [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, L.C. The role of platelet microvesicles in intercellular communication. Platelets 2017, 28, 222-227. [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.P.; Brindis, R.G.; Chaitman, B.R.; Cohen, D.J.; Cross, J.T.; Drozda, J.P.; Fesmire, F.M.; Fintel, D.J.; Fonarow, G.C.; Fox, K.A.; et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards; American College of Emergency Physicians; Emergency Nurses Association; National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians; National Association of EMS Physicians; Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2013 ACCF/AHA key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes and coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Acute Coronary Syndromes and Coronary Artery Disease Clinical Data Standards). Circulation 2013, 127, 1052-1089. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, F.; Yang, X.; Proebsting, S.; Hoelscher, M.; Przybilla, D.; Baumann, K.; Schmitz, T.; Dolf, A.; Endl, E.; Franklin, B.S.; et al. MicroRNA expression in circulating microvesicles predicts cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc 2014, 3: e001249. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.P.; Ismail, N.; Zhang, X.; Aguda, B.D.; Lee, E.J.; Yu, L.; Xiao, T.; Schafer, J.; Lee, M.L.; Schmittgen, T.D.; et al. Detection of microRNA expression in human peripheral blood microvesicles. PLoS One 2008, 3: e3694. [CrossRef]

- Colpaert, R.M.W.; Calore, M. Epigenetics and microRNAs in cardiovascular diseases. Genomics 2021; 113: 540-551. [CrossRef]

- Kong, A.S.; Lai, K.S.; Lim, S.E.; Sivalingam, S.; Loh, J.Y.; Maran, S. miRNA in Ischemic Heart Disease and Its Potential as Biomarkers: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23: 9001. [CrossRef]

- Plawinski, L.; Cras, A.; Hernández, L.J.R.; de la Peña, A.; van der Heyden, A.; Belle, C.; Toti, F.; Anglés-Cano, E. Plasmin-Generating Microvesicles: Tiny Messengers Involved in Fibrinolysis and Proteolysis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 1571. [CrossRef]

- Luna, B.D.; Lovering, R.C.; Caporali, A. Insights into Online microRNA Bioinformatics Tools. Noncoding RNA 2023, 9, 18. [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, R. Transforming Clinical Research: The Power of High-Throughput Omics Integration. Proteomes 2024, 12, 25. [CrossRef]

- Shaker, F.; Nikravesh, A.; Arezumand, R.; Aghaee-Bakhtiari, S.H. Web-based tools for miRNA studies analysis. Comput Biol Med 2020, 127, 104060. [CrossRef]

- Gatsiou, A.; Boeckel, J.N.; Randriamboavonjy, V.; Stellos, K. MicroRNAs in platelet biogenesis and function: implications in vascular homeostasis and inflammation. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2012, 10, 524-531. [CrossRef]

- Elgheznawy, A.; Fleming, I. Platelet-Enriched MicroRNAs and Cardiovascular Homeostasis. Antioxid Redox Signal 2018, 29, 902-921. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.W.; Shen, Y.J.; Shi, J.; Yu, J.G. MiR-223-3p in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Biomarker and Potential Therapeutic Target. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 7, 610561. [CrossRef]

- Provost, P. Existence of a microRNA pathway in anucleate platelets. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2009, 16, 961-966. [CrossRef]

- Pordzik, J.; Pisarz, K.; de Rosa, S.; Jones, A.D.; Eyileten, C.; Indolfi, C.; Malek, L.; Postula, M. The Potential Role of Platelet-Related microRNAs in the Development of Cardiovascular Events in High-Risk Populations, Including Diabetic Patients: A Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 74. [CrossRef]

- Czajka, P.; Fitas, A.; Jakubik, D.; Eyileten, C.; Gasecka, A.; Wicik, Z.; Siller-Matula, J.M.; Filipiak, K.J.; Postula, M. MicroRNA as Potential Biomarkers of Platelet Function on Antiplatelet Therapy: A Review. Front. Physiol 2021, 12, 652579. [CrossRef]

- Leng, Q.; Ding, J.; Dai, M.; Liu, L.; Fang, Q.; Wang, D.W.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y. Insights Into Platelet-Derived MicroRNAs in Cardiovascular and Oncologic Diseases: Potential Predictor and Therapeutic Target. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 879351. [CrossRef]

- Masoodi, K.P.; Ghydari, M.E.; Vazifeh, S.N.; Shirazy, M.; Hamidpour, M. Platelet MicroRNA-484 as a Novel Diagnostic Biomarker for Acute Coronary Syndrome. Lab Med 2023, 54, 256-261. [CrossRef]

- Gager, G.M.; Eyileten, C.; Postula, M.; Gasecka, A.; Jarosz-Popek, J.; Gelbenegger, G.; Jilma, B.; Lang, I.; Siller-Matula, J. Association Between the Expression of MicroRNA-125b and Survival in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome and Coronary Multivessel Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 948006. [CrossRef]

- Ewelina, K.; Eljaszewicz, A.; Kazimierczyk, R.; Tynecka, M.; Zembko, P.; Tarasiuk, E.; Kaminski, K.; Sobkowicz, B.; Moniuszko, M.; Tycinska, A. Altered microRNA dynamics in acute coronary syndrome. Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej 2020, 16, 287-293. [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.C.; Kwee, L.C.; Neely, M.L.; Grass, E.; Jakubowski, J.A.; Fox, A.A.; White, H.D.; Gregory, S.G.; Gurbel, P.A.; Carvalho, L.P.; et al. Circulating MicroRNA Profiling in Non-ST Elevated Coronary Artery Syndrome Highlights Genomic Associations with Serial Platelet Reactivity Measurements. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 6169. [CrossRef]

- Stojkovic, S.; Wadowski, P.P.; Haider, P.; Weikert, C.; Pultar, J.; Lee, S.; Eichelberger, B.; Hengstenberg, C.; Wojta, J.; Panzer, S.; et al. Circulating MicroRNAs and Monocyte-Platelet Aggregate Formation in Acute Coronary Syndrome. Thromb Haemost 2021, 121, 913-922. [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Guo, Z.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Song, C. Serum Exosomal MicroRNA-21, MicroRNA-126, and PTEN Are Novel Biomarkers for Diagnosis of Acute Coronary Syndrome. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 654. [CrossRef]

- Szelenberger, R.; Karbownik, M.S.; Kacprzak, M.; Synowiec, E.; Michlewska, S.; Bijak, M.; Zielińska, M.; Olender, A.; Saluk-Bijak, J. Dysregulation in the Expression of Platelet Surface Receptors in Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients-Emphasis on P2Y12. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11(5):644. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, L. Circulating miR-660-5p is associated with no-reflow phenomenon in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Anatol J Cardiol 2021, 25(5): 323-329. [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, I.; Frossard, M.; Spiel, A.; Riedmüller, E.; Laggner, A.N.; Jilma, B. Platelet function in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) predicts recurrent ACS. J Thromb Haemost 2006, 4, 2547–2552. [CrossRef]

- van der Meijden, P.E.J.; Heemskerk, J.W.M. Platelet biology and functions: new concepts and clinical perspectives. Nat Rev Cardiol 2019, 16: 166-179. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Lv, H.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Chang, Y.; Lv, W.; Sheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, P.; et al. HGPGD: the human gene population genetic difference database. PLoS One 2013, 8, e64150. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.D.; Zhang, Y.P. Different level of population differentiation among human genes. BMC Evol Biol 2011, 11, 16. [CrossRef]

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium; Auton, A.; Brooks, L.D.; Durbin, R.M.; Garrison, E.P.; Kang, H.M.; Korbel, J.O.; Marchini, J.L.; McCarthy, S.; McVean, G.A; Abecasis, G.R. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68-74. [CrossRef]

| Clinical variable | TIMI 3 (n = 17) |

TIMI 0 (n = 15) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | 62.0 [57.0–66.0] | 62.5 [55.0–65.7] | 0.85 |

| Male n (%) | 9 (52.9) | 9 (60.0) | 0.24 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 24.9 [22.2–30.1] | 25.8 [23.7–31.0] | 0.48 |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Glucose [mg/dL] | 136.0 ± 47.0 | 112.9 ± 26.6 | 0.78 |

| Triglyceride [mg/dL] | 125.0 [96.1–183.1] | 162.2 [130.0–257.2] | 0.17 |

| Total cholesterol [mg/dL] | 150.5 ± 47.3 | 156.4 ± 43.3 | 1.00 |

| LDL [mg/dL] | 84.3 ± 44.9 | 90.5 ± 32.5 | 0.72 |

| HDL [mg/dL] | 41.0 ± 12.5 | 34.1 ± 9.5 | 0.18 |

| Platelets [x103/µL] | 214.1 ± 69.9 | 210.5 ± 86.3 | 0.91 |

| MPV [fL] | 9.2 ± 1.3 | 9.4 ± 1.4 | 0.74 |

| Hemoglobin [g/dL] | 14.9 [13.3–17.0] | 15.0 [13.9–16.4] | 0.87 |

| Hematocrit [%] | 41.9 ± 8.6 | 45.2 ± 6.3 | 0.31 |

| McV [fL] | 91.5 ± 7.1 | 91.3 ± 3.9 | 0.91 |

| McH [pg] | 32.1 ± 1.3 | 30.2 ± 1.7 | 0.08 |

| CPK-MB [U/mL] | 5.9 [3.2–54.1] | 3.1 [2.6–103.3] | 0.77 |

| Troponin [ng/mL] | 1.1 [0.3–37.4] | 5.1 [0.6–16.3] | 1.00 |

| C-reactive protein [mg/dL] | 8.3 [1.4–63.9] | 4.0 [0.6–21.5] | 0.39 |

| Diabetes n (%) | 6 (35.3) | 2 (13.3) | 0.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).