1. Introduction

The cadherin superfamily includes over 100 cell-surface glycoproteins, which are characterized by conserved extracellular cadherin repeats [

1,

2]. The first identified cadherins (E-Cadherin/CDH1, N-Cadherin/CDH2, P-Cadherin/CDH3) and their closest relatives are classified as classical cadherins. These are divided into type I (CDH1–CDH4 and CDH15) and type II (CDH5–CDH12, CDH18–CDH20, CDH22, and CDH24) cadherins [

3]. Classical cadherins are crucial for tissue development and maintenance in vertebrates [

4]. In the nervous system, they participate in a wide range of developmental processes, including neurulation, neuronal migration, neurite outgrowth, axonal fasciculation, synaptic differentiation, and synaptic plasticity [

5].

Each cadherin in the brain is expressed in specific groups of functionally connected nuclei and laminae [

6]. A type II classical cadherin, cadherin-8 (CDH8), plays a crucial role in cold sensation, with its neural circuitry formed by sensory neurons projecting into the spinal cord [

7]. The CDH8-expressing sensory neurons were found to connect to CDH8-expressing dorsal horn neurons in the spinal cord, and CDH8 was located near the synaptic junctions formed between these neuronal groups [

7].

The neuron-specific transcription factor T-box brain 1 (TBR1) is crucial for brain development [

8]. TBR1 haploinsufficiency changed the expression of CDH8, resulting in decreased inter- and intra-amygdalar connectivity and cognitive problems in a mouse model [

9]. These developmental abnormalities are likely to impair neuronal activation in response to behavioral stimuli, as evidenced by a reduced number of c-FOS–positive neurons in the TBR1 (+/−) amygdalae [

9].

Autism spectrum disorder is characterized by impairments in social communication and learning disability and is implicated to arise from aberrant synaptic connectivity [

10]. For instance, rare variants in the neuroligin and neurexin genes, which encode synaptic adhesion molecules that interact across the synaptic cleft, have been linked to increased susceptibility to autism [

11,

12]. Furthermore, rare familial microdeletions on chromosome 16q21 that disrupt CDH8 were identified in families with autism spectrum disorder and learning disabilities [

13]. In a family, three of the four boys with autism and learning disabilities inherited the deletion, but it was not present in their four unaffected siblings or their unaffected mother [

13]. Therefore, CDH8 is proposed as a susceptibility factor for autism and learning disabilities.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that detect CDH8 by Western blotting or immunohistochemistry (IHC) have been developed for various applications; however, suitable mAbs for flow cytometry are not currently available. Using the Cell-Based Immunization and Screening (CBIS) method, our laboratory has previously developed anti-CDH1 [

14] and anti-CDH15 [

15] mAbs for use in flow cytometry, Western blotting, and IHC. The CBIS method involves high-throughput flow cytometry–based screening, and mAbs produced using this approach usually recognize conformational epitopes, which allows their use in flow cytometry. Notably, some of these mAbs are also compatible with Western blotting and IHC. In this study, we used the CBIS method to develop highly versatile anti-CDH8 mAbs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

Mouse myeloma P3X63Ag8U.1 (P3U1), human glioblastoma (GBM) LN229, and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) TE5 was obtained from the Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer at Tohoku University (Miyagi, Japan).

2.2. Stable Transfectants

Genes encoding human

CDH8 (NM_001796.5) were obtained from the RIKEN BioResource Research Center (Ibaraki, Japan). The

CDH8 cDNA was subcloned into the pCAG-Ble vector with an N-terminal MAP16 tag [

16]. Additionally, the

CDH8 cDNA with an N-terminal PA16 tag [

17] was constructed. These plasmids were transfected into LN229 or CHO-K1cells, and stable transfectants were sorted using an anti-MAP16 tag mAb (clone PMab-1) [

16] or an anti-PA16 tag mAb (clone NZ-1) [

17] using the Neon transfection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Finally, MAP16-CDH8-overexpressed LN229 (LN229/CDH8) and PA16-CDH8-overexpressed CHO-K1 (CHO/CDH8) were established.

Type I cadherin-overexpressed CHO-K1 cell lines were previously established in [

14]. Type II cadherin-overexpressed CHO-K1 cell lines were established previously [

18]. Truncated, seven-domain (7D), and atypical cadherin overexpressed CHO-K1 cell lines were previously established in [

18]. Each cadherin expression was confirmed using an anti-CDH1 mAb (clone Ca

1Mab-3 [

14],), an anti-CDH3 mAb (clone MM0508-9V11, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), an anti-CDH6 mAb (clone 427909, R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), an anti-CDH15 mAb (clone Ca

15Mab-1 [

15]), an anti-CDH17 mAb (clone 2618, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and another anti-PA16-tag mAb (clone NZ-33 [

19]) to detect other cadherins.

2.3. Production of Hybridomas

Female BALB/cAJcl mice (CLEA Japan, Tokyo, Japan) were intraperitoneally immunized with LN229/CDH8 cells (1 × 10

8 cells/injection) mixed with 2% Alhydrogel adjuvant (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA). Following three additional weekly immunizations (1.0 × 10

8 cells/injection), a booster dose (1 × 10

8 cells/injection) was administered two days before spleen excision. Hybridomas were produced as previously described [

15].

2.4. Flow Cytometry Analysis and Determination of Dissociation Constant Values

CHO/CDH8 and TE5 cells were harvested with 1 mM EDTA were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; blocking buffer). The cells and incubated with Ca

8Mab-4 and flow cytometric data were acquired and the dissociation constant (

KD) values were calculated as described previously [

15].

2.5. Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed using 1 μg/mL Ca

8Mab-4, 1 μg/mL of NZ-1, or 1 μg/mL of an anti-isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mAb (clone RcMab-1) as described previously [

15].

2.6. IHC Using Cell Blocks

The formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) cell sections were stained with Ca

8Mab-4 (0.1 or 10 μg/mL), MpMab-2 (10 μg/mL, IgG

1 isotype control,

http://www.med-tohoku-antibody.com/topics/001_paper_antibody_PDIS.htm), or NZ-33 (0.01 μg/mL) using the

BenchMark ULTRA

PLUS with OptiView DAB IHC Detection Kit

or ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics

, Indianapolis, IN, USA

).

3. Results

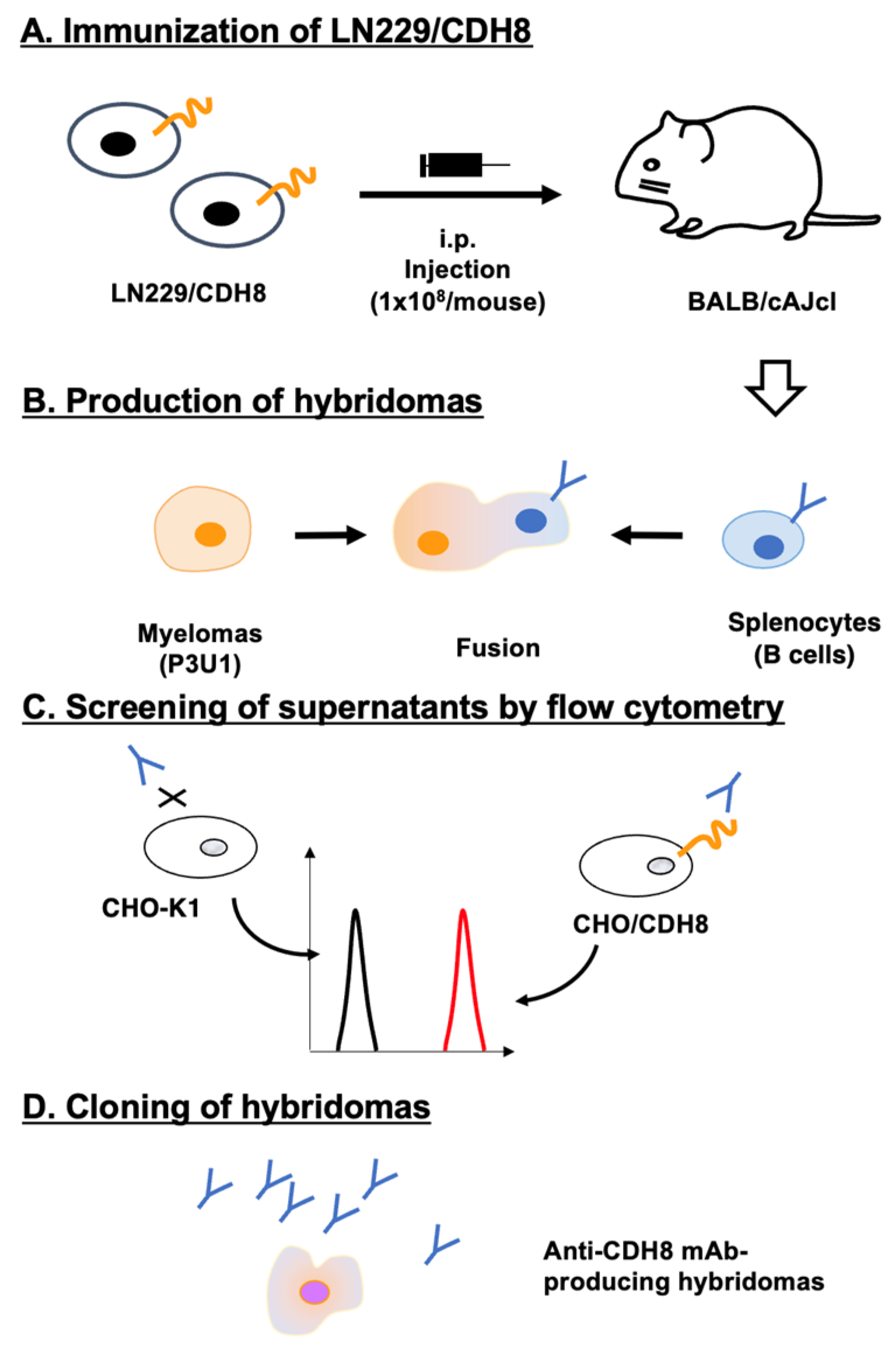

3.1. Development of Anti-CDH8 mAbs by the CBIS Method

An immunogen, LN229/CDH8, was prepared as described in the Materials and Methods. LN229/CDH8 (1 × 10

8 cells/mouse) was intraperitoneally injected five times into two BALB/cAJcl mice (

Figure 1A). Hybridomas were produced by fusing splenocytes with myeloma P3U1 (

Figure 1B). The supernatants of the hybridoma were screened to identify those positive for CHO/CDH8 and negative for CHO-K1 (

Figure 1C). As a result, 54 positive wells out of 956 (5.6%) were found. Limiting dilution was then performed to clone hybridomas producing anti-CDH8 mAb (

Figure 1D). Finally, 4 clones were established, and the purified mAbs were prepared.

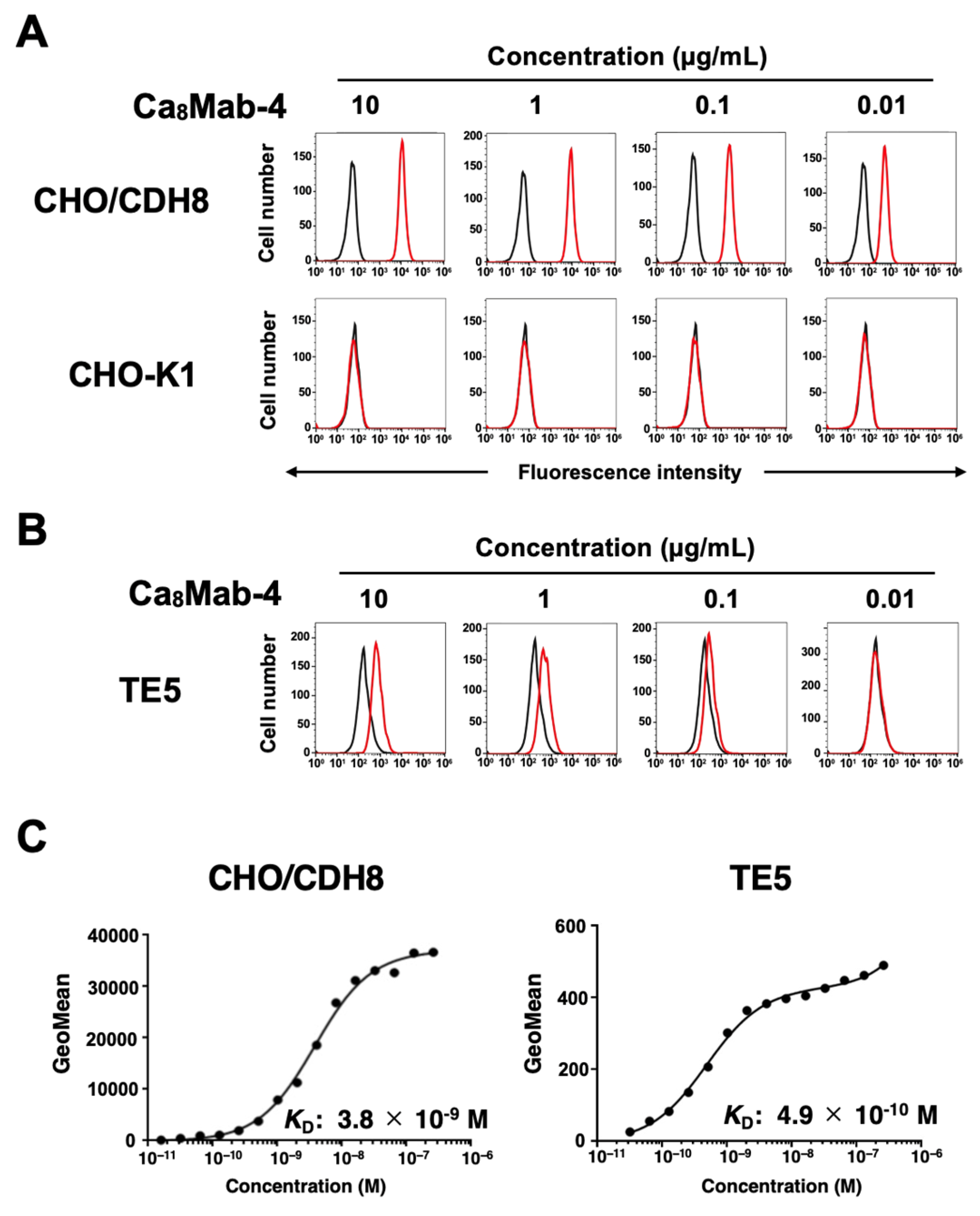

3.2. Flow Cytometry Analyses of Ca8Mab-4 Against CHO-K1, CHO/CDH8, and TE5

Among four clones, we selected Ca

8Mab-4 (IgG

1, κ) based on its reactivity in flow cytometry and suitability for Western blotting (

http://www.med-tohoku-antibody.com/topics/001_paper_antibody_PDIS.htm).

Figure 2 shows the flow cytometry analysis using Ca

8Mab-4 against CHO/CDH8 and CHO-K1. Ca

8Mab-4 reacted in a dose-dependent manner with CHO/CDH8 from 10 to 0.01 μg/mL (

Figure 2A). In contrast, Ca

8Mab-4 did not recognize CHO-K1 even at 10 μg/mL (

Figure 2A). Additionally, Ca

8Mab-4 reacted with human esophageal SCC TE5 in a dose-dependent way (

Figure 2B), indicating that TE5 expresses endogenous CDH8. The binding affinity of Ca

8Mab-4 was assessed through flow cytometry. The fitted binding isotherms of Ca

8Mab-4 binding to CHO/CDH8 and TE5 are shown in

Figure 2C. The

KD values were 3.8 × 10⁻⁹ M for CHO/CDH8 and 4.9 × 10⁻¹⁰ M for TE5. These findings demonstrate that Ca

8Mab-4 has a high binding affinity for CDH8-positive cell lines.

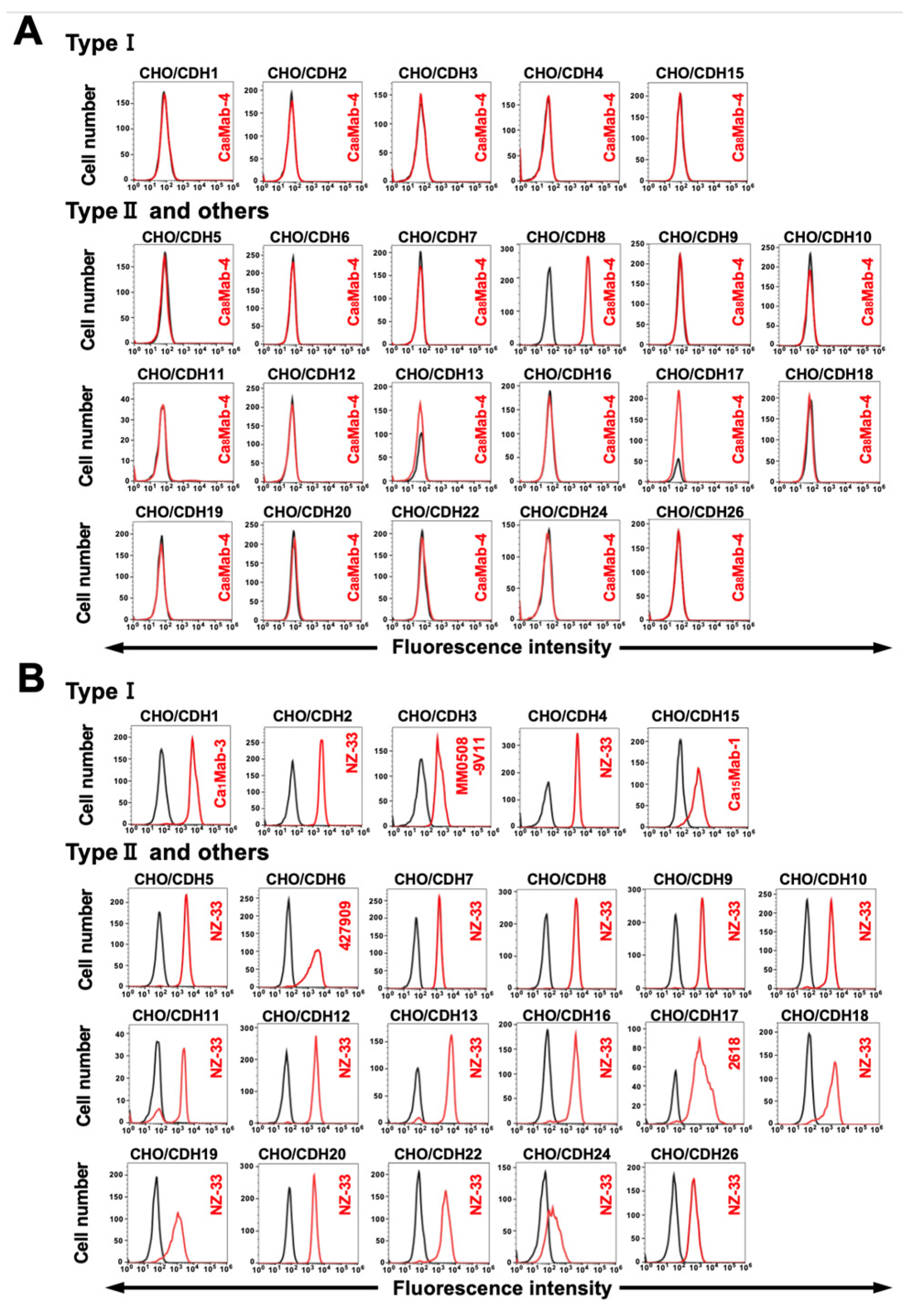

3.3. Determination of the Specificity of Ca8Mab-4 Using CDHs-Overexpressed CHO-K1

We previously established CHO-K1 cells, which overexpressed type I cadherins (CDH1–CDH4 and CDH15) [

14,

15], type II cadherins (CDH5–CDH12, CDH18–CDH20, CDH22, and CDH24), a truncated cadherin (CDH13), 7D cadherins (CDH16 and CDH17), and an atypical cadherin (CDH26) [

18]. Therefore, the specificity of Ca

8Mab-4 to those cadherins was determined. As shown in

Figure 3A, Ca

8Mab-4 recognized CHO/CDH8 but did not react with other cadherins-overexpressed CHO-K1 cells. The cell surface expression of each cadherin was confirmed in

Figure 3B. These results indicate that Ca

8Mab-4 is a specific mAb to CDH8 among those CDHs.

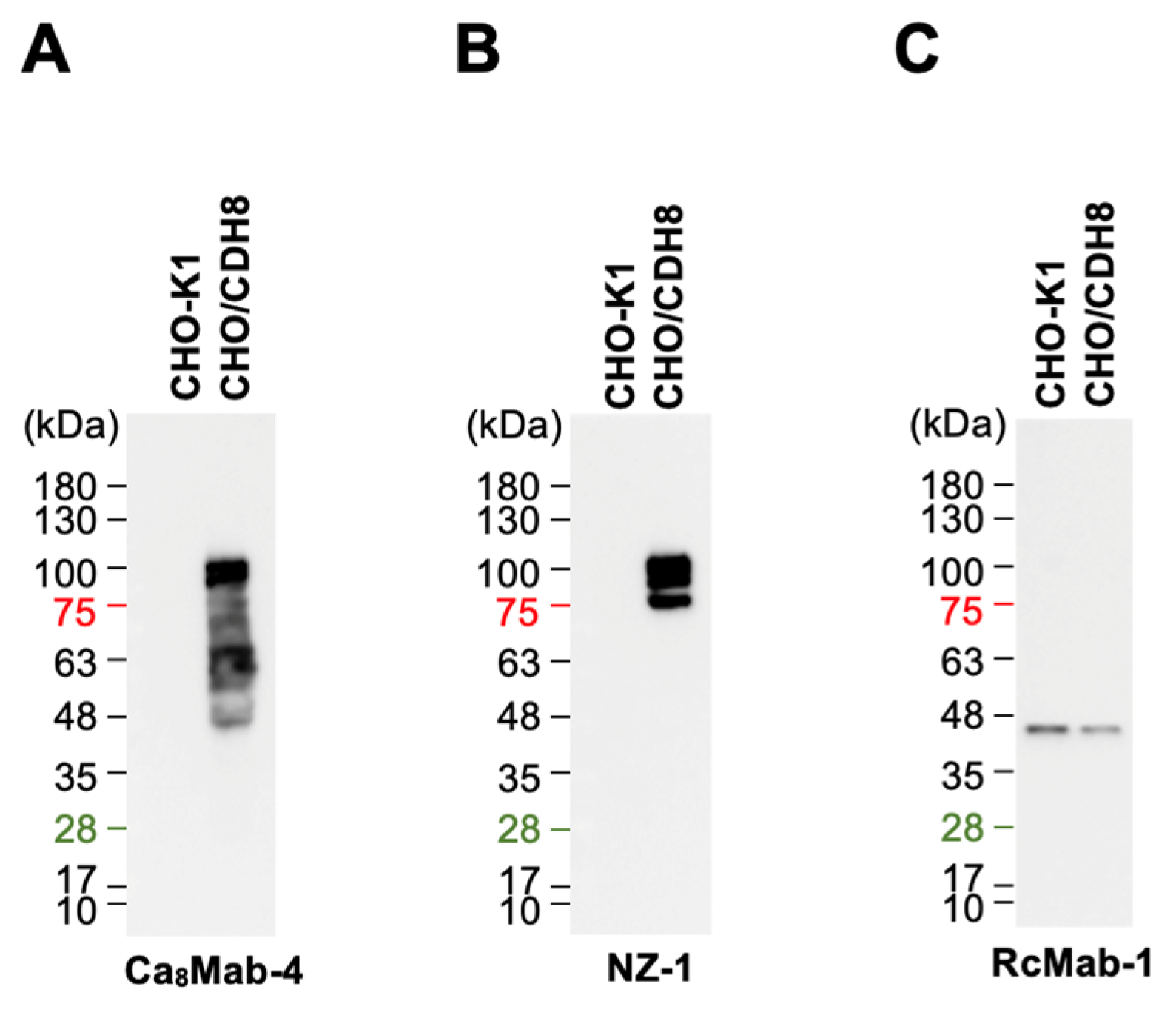

3.4. Western Blotting Using Ca8Mab-4

We next tested whether Ca

8Mab-4 is suitable for Western blotting. Whole-cell lysates from CHO-K1 and CHO/CDH8 were analyzed. Ca

8Mab-4 detected bands around 63–100 kDa in CHO/CDH8, but not in CHO-K1 (

Figure 4A). An anti-PA16 mAb (NZ-1) primarily detected 100 kDa in CHO/CDH8 (

Figure 4B). An internal control, IDH1, was detected by RcMab-1 (

Figure 4C). These results demonstrate that Ca

8Mab-4 can detect CDH8 in Western blotting.

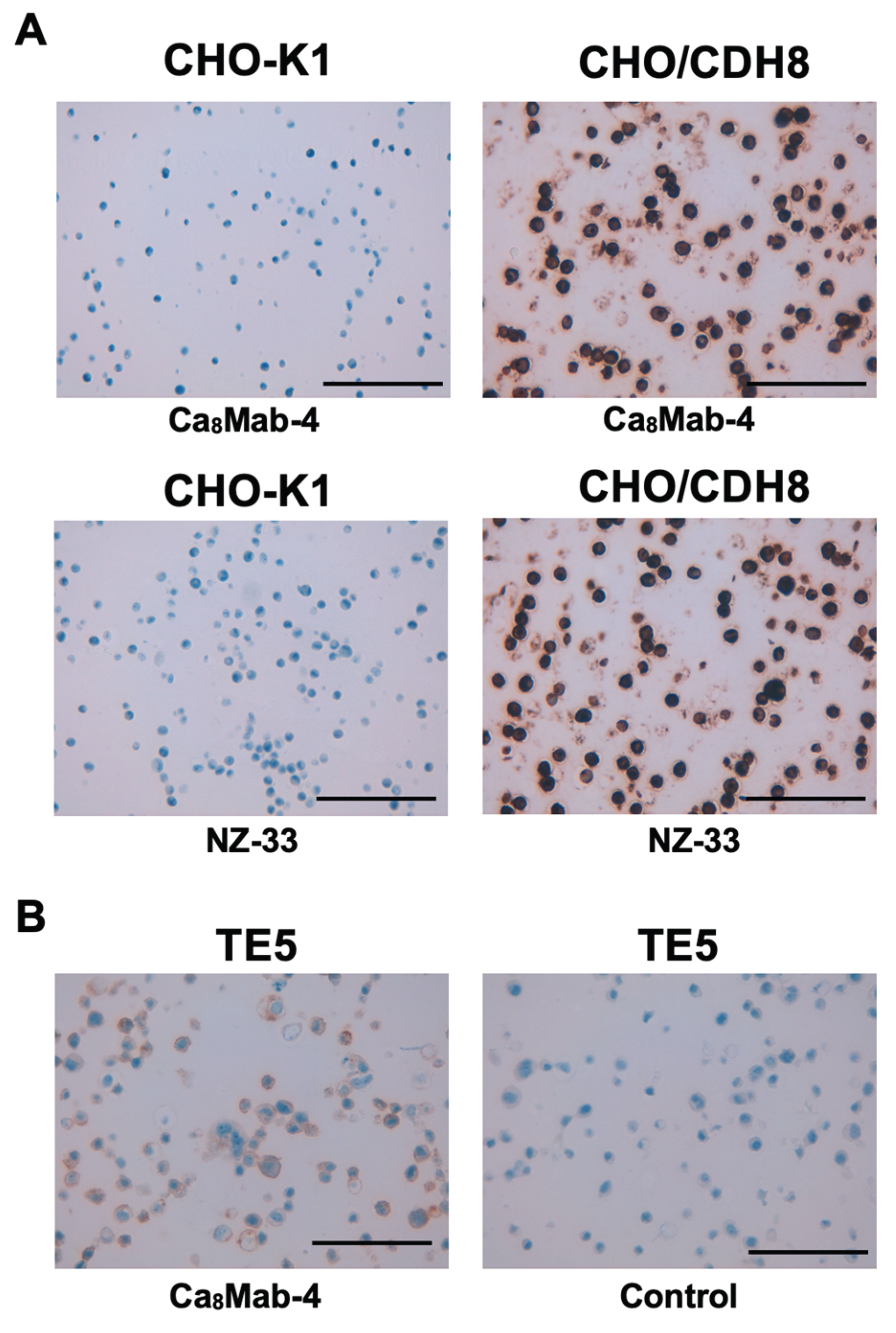

3.5. IHC Using Ca8Mab-4 in FFPE Cell Blocks

We next tested whether Ca

8Mab-4 is suitable for IHC in FFPE sections from CHO-K1 and CHO/CDH8. Ca

8Mab-4 showed intense membranous and cytoplasmic staining in CHO/CDH8 but not in CHO-K1 (

Figure 5A). Additionally, an anti-PA16 tag mAb (NZ-33) exhibited a similar staining (

Figure 5B). Ca

8Mab-4 also showed a membranous staining in TE5, but the isotype control mAb (MpMab-2) did not. These results indicate that Ca

8Mab-4 can detect exogenous and endogenous CDH8 in IHC of FFPE sections of cultured cells.

4. Discussion

CDH8 has five extracellular cadherin repeats, one of which mediates calcium-dependent homophilic and heterophilic interactions [

20]. In this study, we developed a novel anti-CDH8 mAb using the CBIS method (

Figure 1). A clone Ca

8Mab-4 showed strong recognition of both exogenous and endogenous CDH8 in flow cytometry and IHC (

Figure 3 and

Figure 5). Importantly, Ca

8Mab-4 exhibited high affinity (

Figure 2C) and specificity for CDH8 without detectable cross-reactivity to other 21 cadherins, including type II, type I, 7D, truncated, and atypical CDH (

Figure 3). Therefore, Ca

8Mab-4 could be helpful for isolating CDH8-positive cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Since cross-reactivity data are unavailable for commercially supplied mAbs, careful validation is necessary, and caution should be exercised when using these mAbs. Additionally, identifying the epitope recognized by Ca

8Mab-4 will be crucial for developing highly specific anti-CDH8 mAbs. Furthermore, Ca

8Mab-4 is suitable for IHC of cell block specimens (

Figure 5). Notably, IHC was performed on an automated slide-staining system, ensuring standardized and reproducible staining conditions. Overall, Ca

8Mab-4 is a versatile antibody with broad applications in basic research and potential clinical use.

We found that Ca

8Mab-4 recognized the human esophageal SCC TE5 cell line in flow cytometry and IHC (

Figure 3 and

Figure 5). Although we examined the reactivity of Ca

8Mab-4 in other esophageal SCC and glioblastoma cell lines, TE5 is the only cell line recognized by Ca

8Mab-4. No studies have examined the role of CDH8 in tumors. Further studies will be essential to clarify the roles of CDH8 in tumor proliferation and metastasis, as well as its expression in various human tumors. Although the extracellular domain of cadherins mediates calcium-dependent homophilic binding [

2], CDH8 was reported to make not only homophilic binding, but also heterophilic one with another type II cadherin, CDH11 [

21]. Since CDH11/OB-cadherin is predominantly expressed in mesenchymal cells and involved in fibrosis [

22], the interaction between CDH8-positive tumor cells and CDH11-positive mesenchymal cells in the tumor microenvironment should be investigated in future studies [

23].

We previously cloned cDNAs from hybridomas and produced recombinant mouse IgG

2a-type mAbs to enhance antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). Using human tumor xenograft models, antitumor activities have been evaluated [

24,

25]. We have cloned the cDNA of Ca

8Mab-4, and the IgG

2a-type Ca

8Mab-4 will be produced and evaluated for

in vitro ADCC and antitumor efficacies in mouse tumor xenograft models.

Using

in situ hybridization,

CDH8 was detected in the developing cortex of a 9-week-old human embryo [

13]. As shown in

Figure 5, Ca

8Mab-4 is suitable for IHC. Therefore, Ca

8Mab-4 will contribute to the analysis of the distribution and subcellular localization of CDH8 in the human central nervous system. CDH8 is a TBR1 target in the cortex [

26], and these have been implicated as risk factors in behavioral disorders such as autism [

27,

28]. This pathway is consistent with the hypothesis that dendritic defects contribute to the pathogenesis of disorders arising from aberrant neuronal wiring. Ca

8Mab-4 will also help clarify the hypothesis.

The CDH8-mediated adhesive code that determines neuronal connectivity has been clarified in mouse models [

7,

29,

30]. In the mouse retina, the dendrites of over 40 different retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) arborize within the inner plexiform layer [

31]. The dendrites are limited to one or several distinct sublaminae. Within these sublaminae, RGC dendrites receive synaptic inputs from at least 70 types of interneurons, including amacrine and bipolar cells [

32,

33]. In TBR1-expressing RGCs, the TBR1-CDH8 axis is required for their laminar specification [

34]. Therefore, Ca

8Mab-4 would be an essential tool to distinguish or isolate CDH8-positive RGCs in human retina or

in vitro differentiated RGCs from induced pluripotent stem cells [

35].

Credit authorship contribution statement

Takuya Nakamura: Investigation; Keisuke Shinoda: Investigation; Hiroyuki Suzuki: Investigation, Writing – original draft; Mika K. Kaneko: Conceptualization; Yukinari Kato: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research was supported in part by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Numbers: JP25am0521010 (to Y.K.), JP25ama121008 (to Y.K.), JP25ama221153 (to Y.K.), JP25ama221339 (to Y.K.), and JP25bm1123027 (to Y.K.), and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) grant no. 25K10553 (to Y.K.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tohoku University (Permit number: 2022MdA-001) for studies involving animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All related data and methods are presented in this paper. Additional inquiries should be addressed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest involving this article.

References

- van Roy, F. Beyond E-cadherin: roles of other cadherin superfamily members in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2014, 14, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratheesh, A.; Yap, A.S. A bigger picture: classical cadherins and the dynamic actin cytoskeleton. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012, 13, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulpiau, P.; Gul, I.S.; van Roy, F. New insights into the evolution of metazoan cadherins and catenins. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2013, 116, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, H.; Takeichi, M. Evolution: structural and functional diversity of cadherin at the adherens junction. J Cell Biol 2011, 193, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, S.; Takeichi, M. Cadherins in brain morphogenesis and wiring. Physiol Rev 2012, 92, 597–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanes, J.R.; Zipursky, S.L. Synaptic Specificity, Recognition Molecules, and Assembly of Neural Circuits. Cell 2020, 181, 536–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.C.; Furue, H.; Koga, K.; Jiang, N.; Nohmi, M.; Shimazaki, Y.; Katoh-Fukui, Y.; Yokoyama, M.; Yoshimura, M.; Takeichi, M. Cadherin-8 is required for the first relay synapses to receive functional inputs from primary sensory afferents for cold sensation. J Neurosci 2007, 27, 3466–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalas, A.B.; Hevner, R.F. Control of Neuronal Development by T-Box Genes in the Brain. Curr Top Dev Biol 2017, 122, 279–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.N.; Chuang, H.C.; Chou, W.H.; Chen, C.Y.; Wang, H.F.; Chou, S.J.; Hsueh, Y.P. Tbr1 haploinsufficiency impairs amygdalar axonal projections and results in cognitive abnormality. Nat Neurosci 2014, 17, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyall, K.; Croen, L.; Daniels, J.; Fallin, M.D.; Ladd-Acosta, C.; Lee, B.K.; Park, B.Y.; Snyder, N.W.; Schendel, D.; Volk, H.; et al. The Changing Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Annu Rev Public Health 2017, 38, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szatmari, P.; Paterson, A.D.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Roberts, W.; Brian, J.; Liu, X.Q.; Vincent, J.B.; Skaug, J.L.; Thompson, A.P.; Senman, L.; et al. Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nat Genet 2007, 39, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamain, S.; Quach, H.; Betancur, C.; Råstam, M.; Colineaux, C.; Gillberg, I.C.; Soderstrom, H.; Giros, B.; Leboyer, M.; Gillberg, C.; et al. Mutations of the X-linked genes encoding neuroligins NLGN3 and NLGN4 are associated with autism. Nat Genet 2003, 34, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnamenta, A.T.; Khan, H.; Walker, S.; Gerrelli, D.; Wing, K.; Bonaglia, M.C.; Giorda, R.; Berney, T.; Mani, E.; Molteni, M.; et al. Rare familial 16q21 microdeletions under a linkage peak implicate cadherin 8 (CDH8) in susceptibility to autism and learning disability. J Med Genet 2011, 48, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubukata, R.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of novel anti-CDH1/E-cadherin monoclonal antibodies for versatile applications. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2026, 45, 102401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubukata, R.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of an anti-CDH15/M-cadherin monoclonal antibody Ca(15)Mab-1 for flow cytometry, immunoblotting, and immunohistochemistry. Biochem Biophys Rep 2025, 43, 102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. MAP Tag: A Novel Tagging System for Protein Purification and Detection. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2016, 35, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Neyazaki, M.; Nogi, T.; Kato, Y.; Takagi, J. PA tag: a versatile protein tagging system using a super high affinity antibody against a dodecapeptide derived from human podoplanin. Protein Expr Purif 2014, 95, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satofuka, H.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of Anti-Human Cadherin-26 Monoclonal Antibody, Ca26Mab-6, for Flow Cytometry. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. Development and characterization of Ea7Mab-10: A novel monoclonal antibody targeting ephrin type-A receptor 7. MI 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.D.; Ciatto, C.; Chen, C.P.; Bahna, F.; Rajebhosale, M.; Arkus, N.; Schieren, I.; Jessell, T.M.; Honig, B.; Price, S.R.; et al. Type II cadherin ectodomain structures: implications for classical cadherin specificity. Cell 2006, 124, 1255–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoyama, Y.; Tsujimoto, G.; Kitajima, M.; Natori, M. Identification of three human type-II classic cadherins and frequent heterophilic interactions between different subclasses of type-II classic cadherins. Biochem J 2000, 349, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavula, T.; To, S.; Agarwal, S.K. Cadherin-11 and Its Role in Tissue Fibrosis. Cells Tissues Organs 2023, 212, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Xiang, H.; Yu, S.; Lu, Y.; Wu, T. Research progress in the role and mechanism of Cadherin-11 in different diseases. J Cancer 2021, 12, 1190–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubukata, R.; Ohishi, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, Y. EphB2-Targeting Monoclonal Antibodies Exerted Antitumor Activities in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Lung Mesothelioma Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Nakamura, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kato, Y. A Cancer-Specific Monoclonal Antibody against HER2 Exerts Antitumor Activities in Human Breast Cancer Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notwell, J.H.; Heavner, W.E.; Darbandi, S.F.; Katzman, S.; McKenna, W.L.; Ortiz-Londono, C.F.; Tastad, D.; Eckler, M.J.; Rubenstein, J.L.; McConnell, S.K.; et al. TBR1 regulates autism risk genes in the developing neocortex. Genome Res 2016, 26, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.N.; Hsueh, Y.P. Brain-specific transcriptional regulator T-brain-1 controls brain wiring and neuronal activity in autism spectrum disorders. Front Neurosci 2015, 9, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rubeis, S.; He, X.; Goldberg, A.P.; Poultney, C.S.; Samocha, K.; Cicek, A.E.; Kou, Y.; Liu, L.; Fromer, M.; Walker, S.; et al. Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature 2014, 515, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeichi, M. Cell sorting in vitro and in vivo: How are cadherins involved? Semin Cell Dev Biol 2023, 147, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Krishnaswamy, A.; De la Huerta, I.; Sanes, J.R. Type II cadherins guide assembly of a direction-selective retinal circuit. Cell 2014, 158, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanes, J.R.; Masland, R.H. The types of retinal ganglion cells: current status and implications for neuronal classification. Annu Rev Neurosci 2015, 38, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baier, H. Synaptic laminae in the visual system: molecular mechanisms forming layers of perception. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2013, 29, 385–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roska, B.; Werblin, F. Vertical interactions across ten parallel, stacked representations in the mammalian retina. Nature 2001, 410, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Reggiani, J.D.S.; Laboulaye, M.A.; Pandey, S.; Chen, B.; Rubenstein, J.L.R.; Krishnaswamy, A.; Sanes, J.R. Tbr1 instructs laminar patterning of retinal ganglion cell dendrites. Nat Neurosci 2018, 21, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandai, M. Pluripotent stem cell-derived retinal organoid/cells for retinal regeneration therapies: A review. Regen Ther 2023, 22, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of anti-CDH8 mAbs production. (A) BALB/cAJcl mice were intraperitoneally injected with LN229/CDH8. (B) After five immunizations, splenocytes were fused with P3U1. (C) The supernatants from hybridomas were screened using CHO-K1 and CHO/CDH8 by flow cytometry. (D) Ca8Mabs, anti-CDH8 mAb-producing hybridoma clones, were established through limiting dilution.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of anti-CDH8 mAbs production. (A) BALB/cAJcl mice were intraperitoneally injected with LN229/CDH8. (B) After five immunizations, splenocytes were fused with P3U1. (C) The supernatants from hybridomas were screened using CHO-K1 and CHO/CDH8 by flow cytometry. (D) Ca8Mabs, anti-CDH8 mAb-producing hybridoma clones, were established through limiting dilution.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of Ca8Mab-4. (A) CHO-K1 and CHO/CDH8 were treated with Ca8Mab-4 at the indicated concentrations (red) or with blocking buffer (black, negative control). (B) Human esophageal SCC TE5 was treated with Ca8Mab-4 at the indicated concentrations (red) or with blocking buffer (black, negative control). The mAbs-treated cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Fluorescence data were collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer. (C) The determination of the dissociation constant of Ca8Mab-4. CHO/CDH8 and TE5 were suspended in serially diluted Ca8Mab-4. Then, cells were treated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Fluorescence data were subsequently collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer. The KD values were calculated by GraphPad PRISM 6.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of Ca8Mab-4. (A) CHO-K1 and CHO/CDH8 were treated with Ca8Mab-4 at the indicated concentrations (red) or with blocking buffer (black, negative control). (B) Human esophageal SCC TE5 was treated with Ca8Mab-4 at the indicated concentrations (red) or with blocking buffer (black, negative control). The mAbs-treated cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Fluorescence data were collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer. (C) The determination of the dissociation constant of Ca8Mab-4. CHO/CDH8 and TE5 were suspended in serially diluted Ca8Mab-4. Then, cells were treated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Fluorescence data were subsequently collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer. The KD values were calculated by GraphPad PRISM 6.

Figure 3.

Specificity of Ca8Mab-4. (A) The type I cadherins (CDH1, CDH2, CDH3, CDH4, and CDH15), type II cadherins (CDH5, CDH6, CDH7, CDH8, CDH9, CDH10, CDH11, CDH12, CDH18, CDH8, CDH20, CDH22, and CDH24), a truncated cadherin (CDH13), 7D cadherins (CDH16 and CDH17), and an atypical cadherin (CDH26)-overexpressed CHO-K1 were treated with 10 µg/mL of Ca8Mab-4 (red) or with control blocking buffer (black, negative control), followed by treatment with anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488. (B) Each cadherin expression was confirmed by 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH1 mAb (clone Ca1Mab-3), 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH3 mAb (clone MM0508-9V11), 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH6 mAb (clone 427909), 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH15 mAb (clone Ca15Mab-1), 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH17 mAb (clone 2618), and 1 µg/mL of an anti-PA16-tag mAb (clone NZ-33) to detect other CDHs, followed by the treatment with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary mAbs. The fluorescence data were collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

Figure 3.

Specificity of Ca8Mab-4. (A) The type I cadherins (CDH1, CDH2, CDH3, CDH4, and CDH15), type II cadherins (CDH5, CDH6, CDH7, CDH8, CDH9, CDH10, CDH11, CDH12, CDH18, CDH8, CDH20, CDH22, and CDH24), a truncated cadherin (CDH13), 7D cadherins (CDH16 and CDH17), and an atypical cadherin (CDH26)-overexpressed CHO-K1 were treated with 10 µg/mL of Ca8Mab-4 (red) or with control blocking buffer (black, negative control), followed by treatment with anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488. (B) Each cadherin expression was confirmed by 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH1 mAb (clone Ca1Mab-3), 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH3 mAb (clone MM0508-9V11), 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH6 mAb (clone 427909), 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH15 mAb (clone Ca15Mab-1), 1 µg/mL of an anti-CDH17 mAb (clone 2618), and 1 µg/mL of an anti-PA16-tag mAb (clone NZ-33) to detect other CDHs, followed by the treatment with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary mAbs. The fluorescence data were collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

Figure 4.

Western blotting using Ca8Mab-4. Cell lysates (10 μg/lane) from CHO-K1 and CHO/CDH8 were electrophoresed and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated with 1 μg/mL of Ca8Mab-4 (A), 1 μg/mL of NZ-1 (B), or 1 μg/mL of RcMab-1 (an anti-IDH1 mAb) (C), followed by the treatment with anti-mouse (Ca8Mab-4) or anti-rat IgG (NZ-1 and RcMab-1)-conjugated with horseradish peroxidase.

Figure 4.

Western blotting using Ca8Mab-4. Cell lysates (10 μg/lane) from CHO-K1 and CHO/CDH8 were electrophoresed and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated with 1 μg/mL of Ca8Mab-4 (A), 1 μg/mL of NZ-1 (B), or 1 μg/mL of RcMab-1 (an anti-IDH1 mAb) (C), followed by the treatment with anti-mouse (Ca8Mab-4) or anti-rat IgG (NZ-1 and RcMab-1)-conjugated with horseradish peroxidase.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry using Ca8Mab-4 in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded cell blocks. (A) CHO-K1 and CHO/CDH8 sections were treated with 0.1 μg/mL of Ca8Mab-4 or 0.01 µg/mL of NZ-33. The staining was performed using BenchMark ULTRA PLUS with the ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit. (B) TE5 sections were treated with 10 μg/mL of Ca8Mab-4 or 10 μg/mL of MpMab-2 (IgG1 isotype control). The staining was performed using BenchMark ULTRA PLUS with the OptiView DAB IHC Detection Kit. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry using Ca8Mab-4 in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded cell blocks. (A) CHO-K1 and CHO/CDH8 sections were treated with 0.1 μg/mL of Ca8Mab-4 or 0.01 µg/mL of NZ-33. The staining was performed using BenchMark ULTRA PLUS with the ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit. (B) TE5 sections were treated with 10 μg/mL of Ca8Mab-4 or 10 μg/mL of MpMab-2 (IgG1 isotype control). The staining was performed using BenchMark ULTRA PLUS with the OptiView DAB IHC Detection Kit. Scale bar = 100 μm.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).