Submitted:

23 May 2023

Posted:

26 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

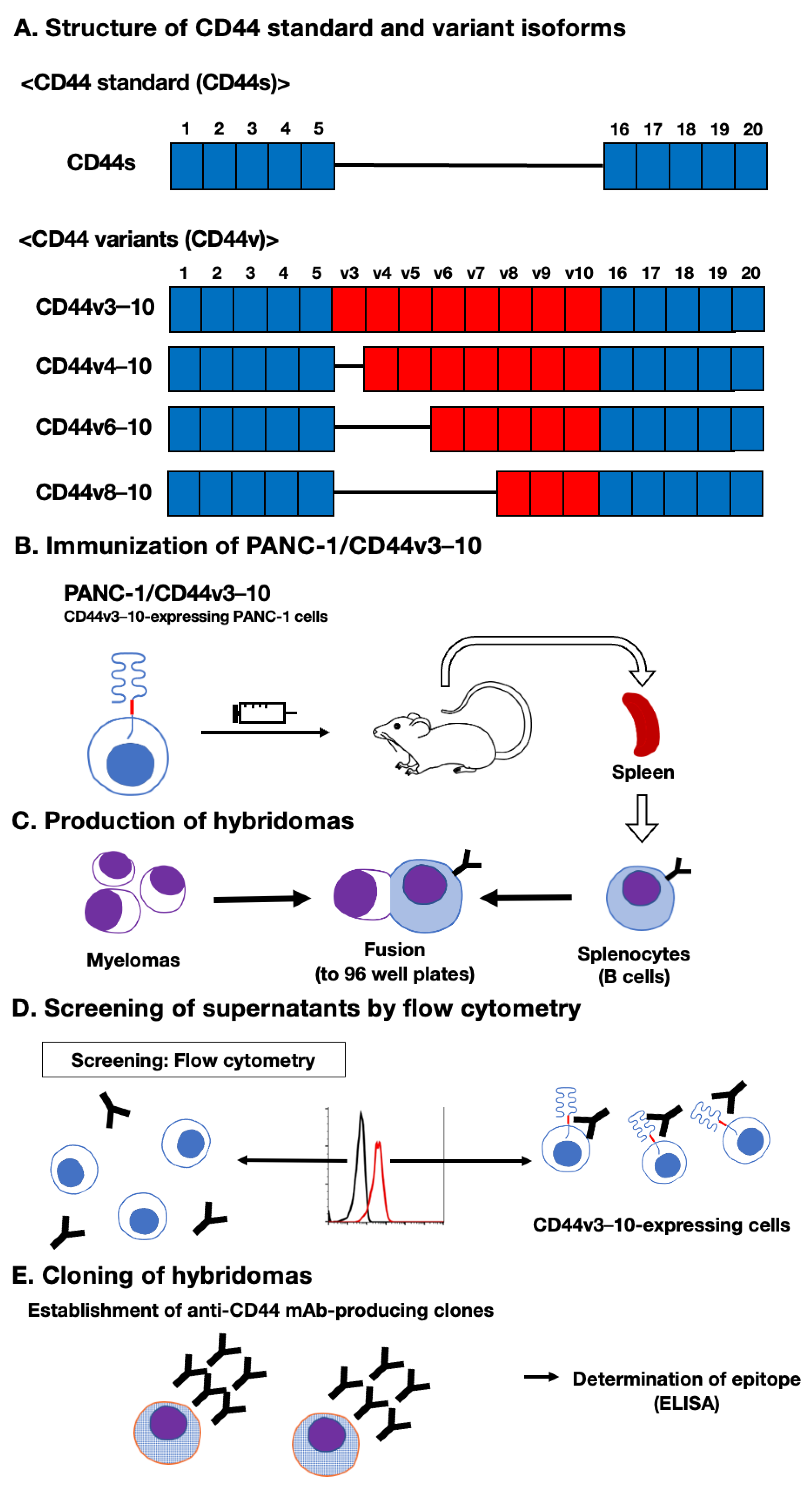

2.2. Production of hybridoma cells

2.3. Enzyme−linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

2.4. Flow Cytometric Analysis

2.5. Determination of Apparent Dissociation Constant (KD) by Flow Cytometry

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

2.7. Immunohistochemical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of an Anti-CD44 mAbs by immunization of PANC-1/CD44v3–10 cells

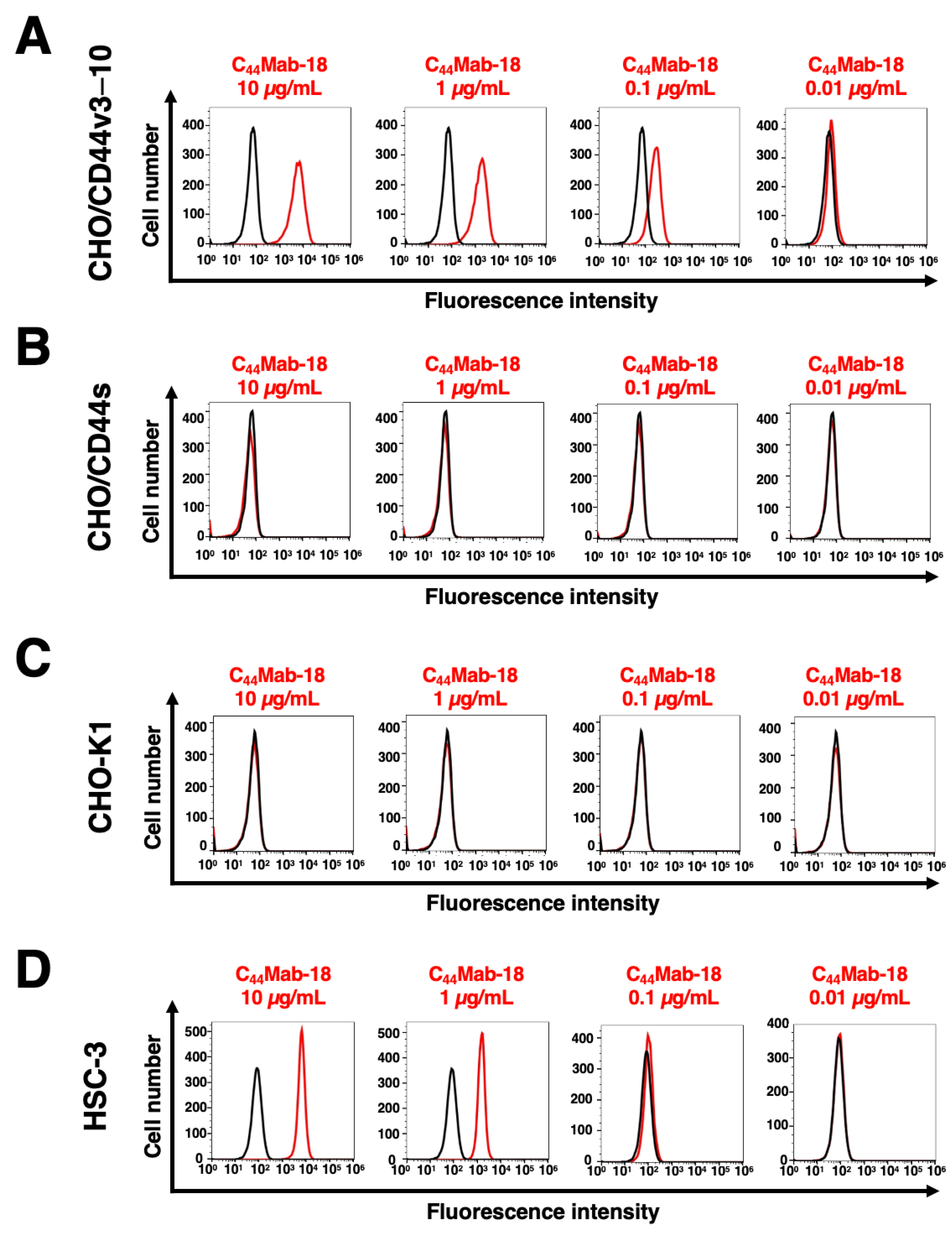

3.2. Flow Cytometric Analysis of C44Mab-18 to CD44-Expressing Cells

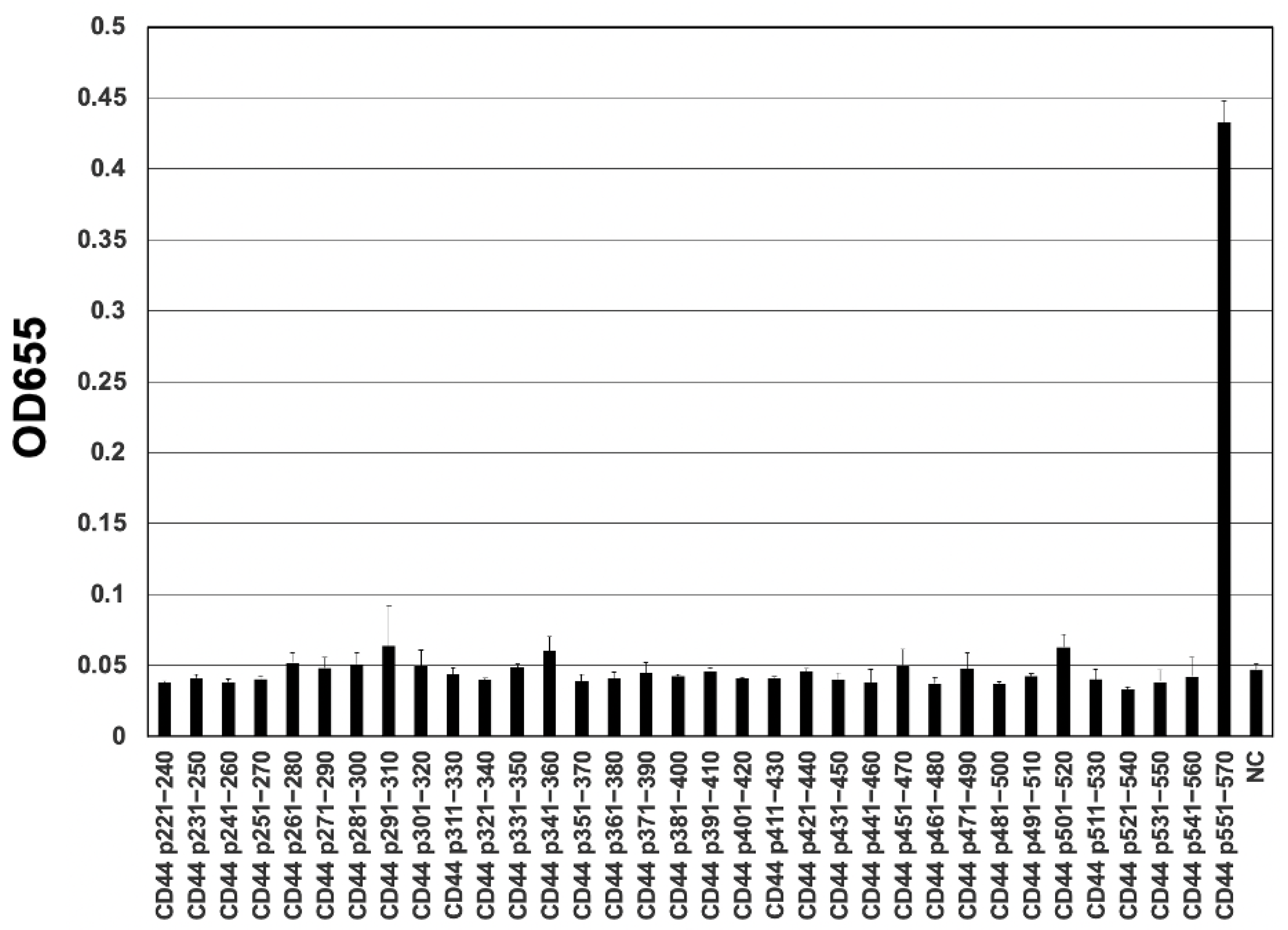

3.3. Epitope Mapping of C44Mab-18 by ELISA

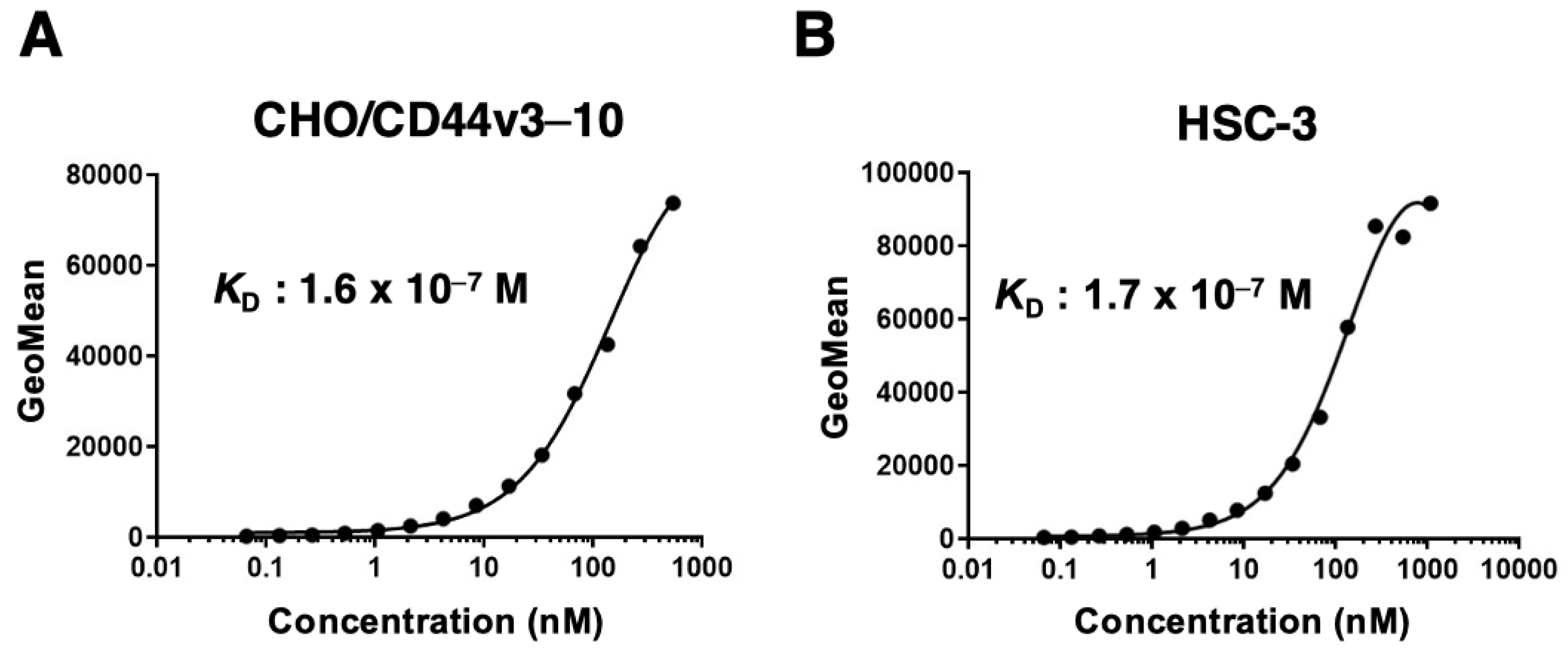

3.3. Determination of the apparent Binding Affinity of C44Mab-18 by Flow Cytometry

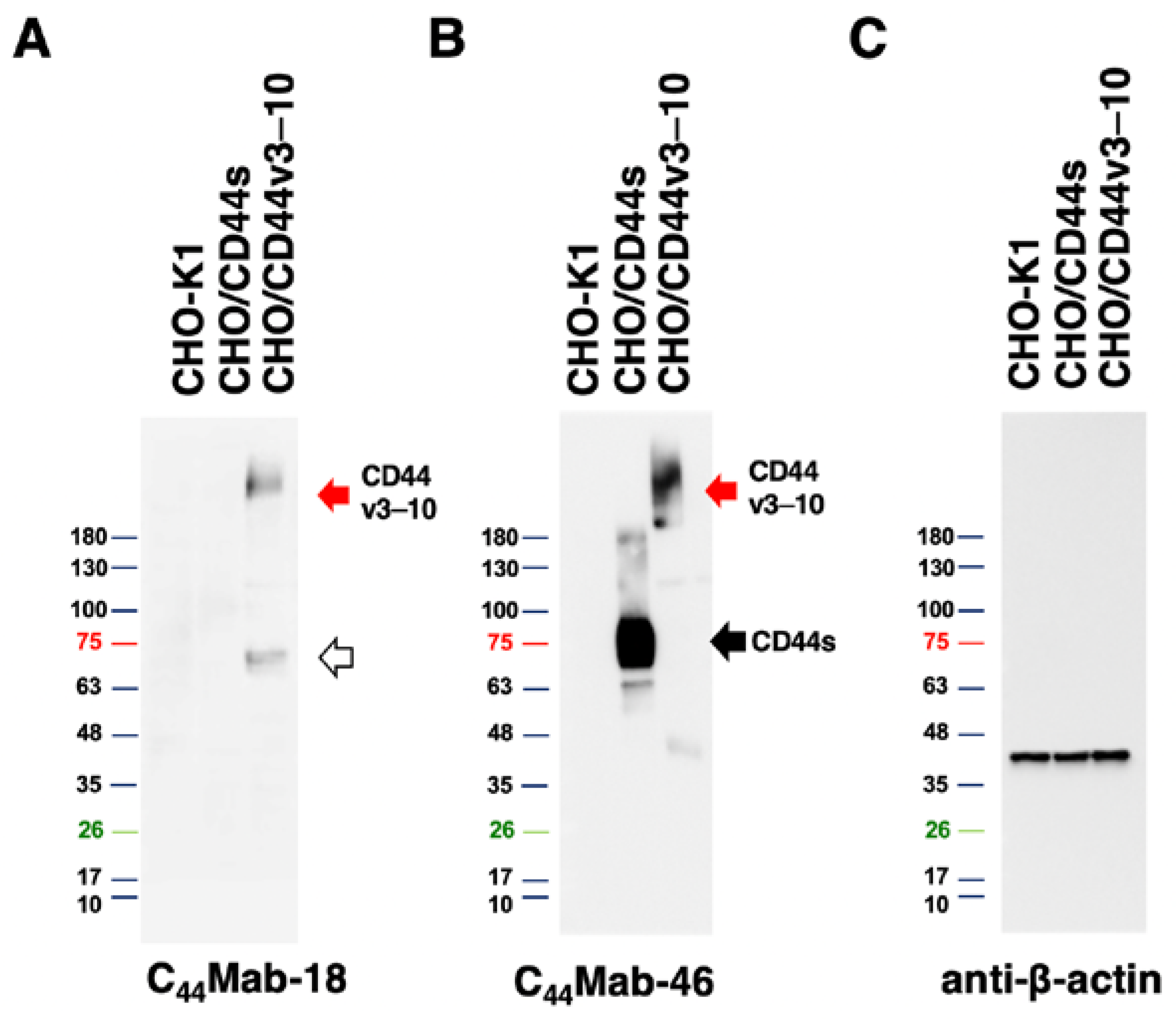

3.4. Western Blot Analysis

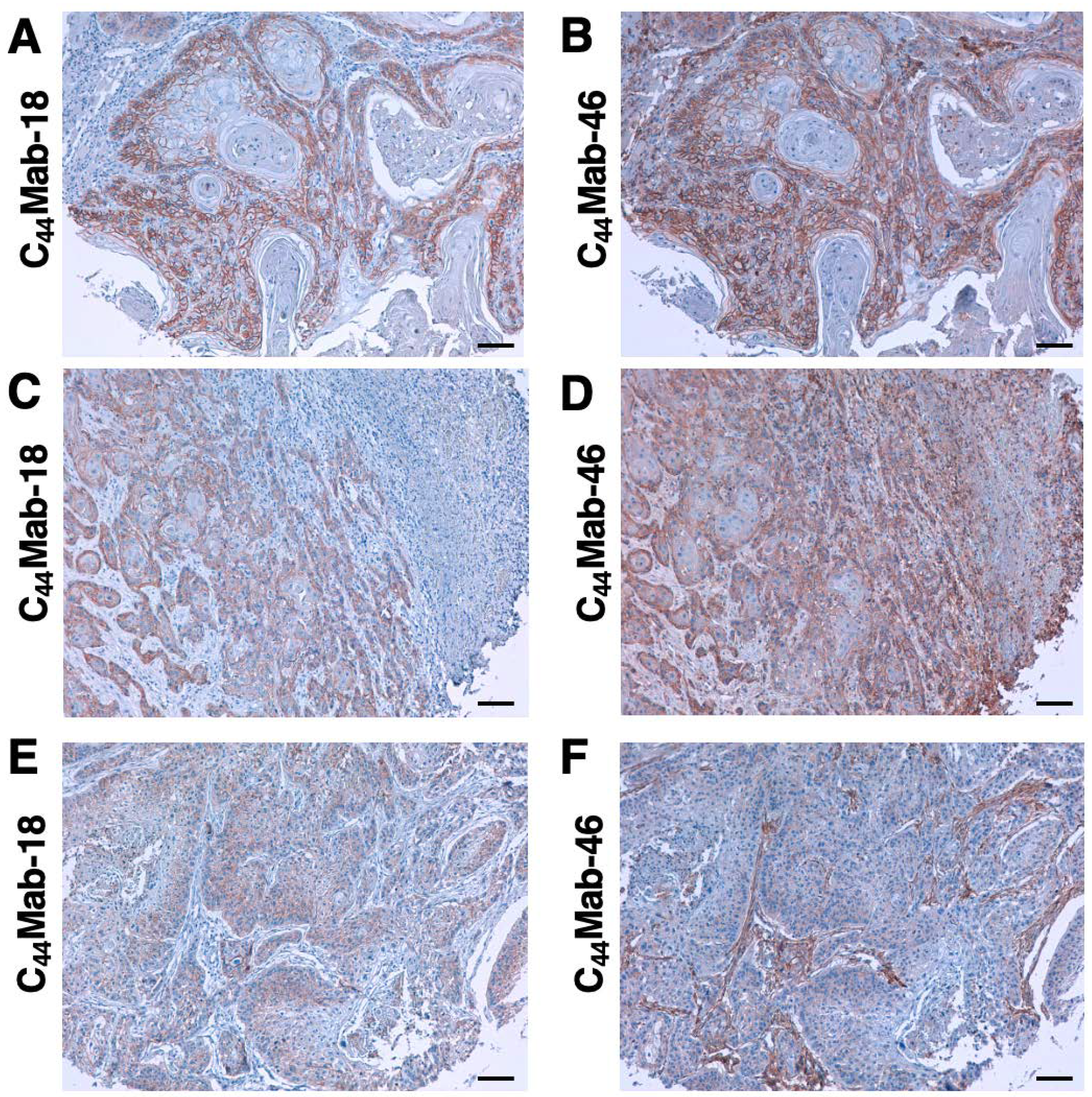

3.5. Immunohistochemical Analysis using C44Mab-18 against Tumor Tissues

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

References

- Mody, M.D.; Rocco, J.W.; Yom, S.S.; Haddad, R.I.; Saba, N.F. Head and neck cancer. Lancet 2021, 398, 2289–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, D.T.; Khor, R.; Gan, H.; Wada, M.; Ermongkonchai, T.; Ng, S.P. Recent Research on Combination of Radiotherapy with Targeted Therapy or Immunotherapy in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Review for Radiation Oncologists. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaffar, J.; Bari, S.; Kirtane, K.; Chung, C.H. Recent Advances and Future Directions in Clinical Management of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.E.; Burtness, B.; Leemans, C.R.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Bauman, J.E.; Grandis, J.R. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, N.; Szczepanski, M.J.; Gluszko, A.; Szafarowski, T.; Azambuja, J.H.; Dolg, L.; Gellrich, N.C.; Kampmann, A.; Whiteside, T.L.; Zimmerer, R.M. CD44(+) tumor cells promote early angiogenesis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett 2019, 467, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponta, H.; Sherman, L.; Herrlich, P.A. CD44: from adhesion molecules to signalling regulators. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2003, 4, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, S.; Karnad, A.; Freeman, J.W. The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: therapeutic implications. J Hematol Oncol 2018, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slevin, M.; Krupinski, J.; Gaffney, J.; Matou, S.; West, D.; Delisser, H.; Savani, R.C.; Kumar, S. Hyaluronan-mediated angiogenesis in vascular disease: uncovering RHAMM and CD44 receptor signaling pathways. Matrix Biol 2007, 26, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valastyan, S.; Weinberg, R.A. Tumor metastasis: molecular insights and evolving paradigms. Cell 2011, 147, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Visser, K.E.; Joyce, J.A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zöller, M. CD44, Hyaluronan, the Hematopoietic Stem Cell, and Leukemia-Initiating Cells. Front Immunol 2015, 6, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassn Mesrati, M.; Syafruddin, S.E.; Mohtar, M.A.; Syahir, A. CD44: A Multifunctional Mediator of Cancer Progression. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zöller, M. CD44: can a cancer-initiating cell profit from an abundantly expressed molecule? Nat Rev Cancer 2011, 11, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, M.E.; Sivanandan, R.; Kaczorowski, A.; Wolf, G.T.; Kaplan, M.J.; Dalerba, P.; Weissman, I.L.; Clarke, M.F.; Ailles, L.E. Identification of a subpopulation of cells with cancer stem cell properties in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Antin, P.; Berx, G.; Blanpain, C.; Brabletz, T.; Bronner, M.; Campbell, K.; Cano, A.; Casanova, J.; Christofori, G.; et al. Guidelines and definitions for research on epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.J.; Divi, V.; Owen, J.H.; Bradford, C.R.; Carey, T.E.; Papagerakis, S.; Prince, M.E. Metastatic potential of cancer stem cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010, 136, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimoto, T.; Nagano, O.; Yae, T.; Tamada, M.; Motohara, T.; Oshima, H.; Oshima, M.; Ikeda, T.; Asaba, R.; Yagi, H.; et al. CD44 variant regulates redox status in cancer cells by stabilizing the xCT subunit of system xc(-) and thereby promotes tumor growth. Cancer Cell 2011, 19, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagami, T.; Yamade, M.; Suzuki, T.; Uotani, T.; Tani, S.; Hamaya, Y.; Iwaizumi, M.; Osawa, S.; Sugimoto, K.; Baba, S.; et al. High expression level of CD44v8-10 in cancer stem-like cells is associated with poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients treated with chemoradiotherapy. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 34876–34888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiwara, M.; Kikuchi, E.; Tanaka, N.; Kosaka, T.; Mikami, S.; Saya, H.; Oya, M. Variant isoforms of CD44 involves acquisition of chemoresistance to cisplatin and has potential as a novel indicator for identifying a cisplatin-resistant population in urothelial cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S.; Itai, S.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Detection of high CD44 expression in oral cancers using the novel monoclonal antibody, C(44)Mab-5. Biochem Biophys Rep 2018, 14, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, N.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Asano, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Anti-CD44 Monoclonal Antibody for Multiple Applications against Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, J.; Asano, T.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Epitope Mapping of the Anti-CD44 Monoclonal Antibody (C44Mab-46) Using Alanine-Scanning Mutagenesis and Surface Plasmon Resonance. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2021, 40, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Takei, J.; Tateyama, N.; Kato, Y. Epitope Mapping of the Anti-CD44 Monoclonal Antibody (C44Mab-46) Using the REMAP Method. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2021, 40, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Epitope Mapping System: RIEDL Insertion for Epitope Mapping Method. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2021, 40, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, J.; Kaneko, M.K.; Ohishi, T.; Hosono, H.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Sano, M.; Asano, T.; Sayama, Y.; Kawada, M.; et al. A defucosylated antiCD44 monoclonal antibody 5mG2af exerts antitumor effects in mouse xenograft models of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep 2020, 44, 1949–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Kitamura, K.; Goto, N.; Ishikawa, K.; Ouchida, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. A Novel Anti-CD44 Variant 3 Monoclonal Antibody C(44)Mab-6 Was Established for Multiple Applications. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Goto, N.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Anti-CD44 Variant 4 Monoclonal Antibody C44Mab-108 for Immunohistochemistry. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2023, 45, 1875–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Anti-CD44 variant 5 Monoclonal Antibody C44Mab-3 for Multiple Applications against Pancreatic Carcinomas. Antibodies 2023, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejima, R.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Asano, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Anti-CD44 Variant 6 Monoclonal Antibody C(44)Mab-9 for Multiple Applications against Colorectal Carcinomas. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Ozawa, K.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Anti-CD44 Variant 7/8 Monoclonal Antibody, C44Mab-34, for Multiple Applications against Oral Carcinomas. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawara, M.; Suzuki, H.; Goto, N.; Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. A Novel Anti-CD44 Variant 9 Monoclonal Antibody C44Mab-1 was Developed for Immunohistochemical Analyses Against Colorectal Cancers Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 3658–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Yamada, S.; Furusawa, Y.; Itai, S.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Sano, M.; Harada, H.; Fukui, M.; Kaneko, M.K. PMab-213: A Monoclonal Antibody for Immunohistochemical Analysis Against Pig Podoplanin. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2019, 38, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, Y.; Yamada, S.; Itai, S.; Sano, M.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Fukui, M.; Harada, H.; Mizuno, T.; Sakai, Y.; et al. PMab-210: A Monoclonal Antibody Against Pig Podoplanin. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2019, 38, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, Y.; Yamada, S.; Itai, S.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Sano, M.; Harada, H.; Fukui, M.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. PMab-219: A monoclonal antibody for the immunohistochemical analysis of horse podoplanin. Biochem Biophys Rep 2019, 18, 100616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furusawa, Y.; Yamada, S.; Itai, S.; Nakamura, T.; Takei, J.; Sano, M.; Harada, H.; Fukui, M.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Establishment of a monoclonal antibody PMab-233 for immunohistochemical analysis against Tasmanian devil podoplanin. Biochem Biophys Rep 2019, 18, 100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kuno, A.; Uchiyama, N.; Amano, K.; Chiba, Y.; Hasegawa, Y.; Hirabayashi, J.; Narimatsu, H.; Mishima, K.; et al. Inhibition of tumor cell-induced platelet aggregation using a novel anti-podoplanin antibody reacting with its platelet-aggregation-stimulating domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006, 349, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura-Sakaguchi, R.; Aruga, R.; Hirose, M.; Ekimoto, T.; Miyake, T.; Hizukuri, Y.; Oi, R.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Akiyama, Y.; et al. Moving toward generalizable NZ-1 labeling for 3D structure determination with optimized epitope-tag insertion. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 2021, 77, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Ohishi, T.; Nakamura, T.; Inoue, H.; Takei, J.; Sano, M.; Asano, T.; Sayama, Y.; Hosono, H.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Development of Core-Fucose-Deficient Humanized and Chimeric Anti-Human Podoplanin Antibodies. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2020, 39, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, Y.; Matsunaga, Y.; Arimori, T.; Kitago, Y.; Ogasawara, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Takagi, J. Tailored placement of a turn-forming PA tag into the structured domain of a protein to probe its conformational state. J Cell Sci 2016, 129, 1512–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; Tsuchihashi, Y.; Izumi, T.; Ogasawara, S.; Okada, N.; Sato, C.; Tobiume, M.; Otsuka, K.; Miyamoto, L.; et al. Antitumor effect of novel anti-podoplanin antibody NZ-12 against malignant pleural mesothelioma in an orthotopic xenograft model. Cancer Sci 2016, 107, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Abe, S.; Ogasawara, S.; Fujii, Y.; Yamada, S.; Murata, T.; Uchida, H.; Tahara, H.; Nishioka, Y.; Kato, Y. Chimeric Anti-Human Podoplanin Antibody NZ-12 of Lambda Light Chain Exerts Higher Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity and Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity Compared with NZ-8 of Kappa Light Chain. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2017, 36, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, A.; Ohta, M.; Kato, Y.; Inada, S.; Kato, T.; Nakata, S.; Yatabe, Y.; Goto, M.; Kaneda, N.; Kurita, K.; et al. A Real-Time Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging Method for the Detection of Oral Cancers in Mice Using an Indocyanine Green-Labeled Podoplanin Antibody. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2018, 17, 1533033818767936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, R.; Oi, R.; Akashi, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Nogi, T. Application of the NZ-1 Fab as a crystallization chaperone for PA tag-inserted target proteins. Protein Sci 2019, 28, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwata, T.; Yoneda, K.; Mori, M.; Kanayama, M.; Kuroda, K.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Tanaka, F. Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (MPM) with the "Universal" CTC-Chip and An Anti-Podoplanin Antibody NZ-1.2. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishinaga, Y.; Sato, K.; Yasui, H.; Taki, S.; Takahashi, K.; Shimizu, M.; Endo, R.; Koike, C.; Kuramoto, N.; Nakamura, S.; et al. Targeted Phototherapy for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Near-Infrared Photoimmunotherapy Targeting Podoplanin. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Neyazaki, M.; Nogi, T.; Kato, Y.; Takagi, J. PA tag: a versatile protein tagging system using a super high affinity antibody against a dodecapeptide derived from human podoplanin. Protein Expr Purif 2014, 95, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kunita, A.; Ito, H.; Kameyama, A.; Ogasawara, S.; Matsuura, N.; Hasegawa, Y.; Suzuki-Inoue, K.; Inoue, O.; et al. Molecular analysis of the pathophysiological binding of the platelet aggregation-inducing factor podoplanin to the C-type lectin-like receptor CLEC-2. Cancer Sci 2008, 99, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Vaidyanathan, G.; Kaneko, M.K.; Mishima, K.; Srivastava, N.; Chandramohan, V.; Pegram, C.; Keir, S.T.; Kuan, C.T.; Bigner, D.D.; et al. Evaluation of anti-podoplanin rat monoclonal antibody NZ-1 for targeting malignant gliomas. Nucl Med Biol 2010, 37, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, K.H.; Sproll, M.; Susani, S.; Patzelt, E.; Beaumier, P.; Ostermann, E.; Ahorn, H.; Adolf, G.R. Characterization of a high-affinity monoclonal antibody specific for CD44v6 as candidate for immunotherapy of squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Immunol Immunother 1996, 43, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, K.H.; Mulder, J.W.; Ostermann, E.; Susani, S.; Patzelt, E.; Pals, S.T.; Adolf, G.R. Splice variants of the cell surface glycoprotein CD44 associated with metastatic tumour cells are expressed in normal tissues of humans and cynomolgus monkeys. Eur J Cancer 1995, 31a, 2385–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gansauge, F.; Gansauge, S.; Zobywalski, A.; Scharnweber, C.; Link, K.H.; Nussler, A.K.; Beger, H.G. Differential expression of CD44 splice variants in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma and in normal pancreas. Cancer Res 1995, 55, 5499–5503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beham-Schmid, C.; Heider, K.H.; Hoefler, G.; Zatloukal, K. Expression of CD44 splice variant v10 in Hodgkin's disease is associated with aggressive behaviour and high risk of relapse. J Pathol 1998, 186, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.N.; Chandavarkar, V.; Sharma, R.; Bhargava, D. Structure, function and role of CD44 in neoplasia. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2019, 23, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Imaeda, H.; Matsuzaki, J.; Tsugawa, H.; Nagano, O.; Asakura, K.; Saya, H.; Hibi, T. CD44 variant 9 expression in primary early gastric cancer as a predictive marker for recurrence. Br J Cancer 2013, 109, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitara, K.; Doi, T.; Nagano, O.; Imamura, C.K.; Ozeki, T.; Ishii, Y.; Tsuchihashi, K.; Takahashi, S.; Nakajima, T.E.; Hironaka, S.; et al. Dose-escalation study for the targeting of CD44v(+) cancer stem cells by sulfasalazine in patients with advanced gastric cancer (EPOC1205). Gastric Cancer 2017, 20, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erb, U.; Megaptche, A.P.; Gu, X.; Büchler, M.W.; Zöller, M. CD44 standard and CD44v10 isoform expression on leukemia cells distinctly influences niche embedding of hematopoietic stem cells. J Hematol Oncol 2014, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, F.; Hellqvist, E.; Mason, C.N.; Ali, S.A.; Delos-Santos, N.; Barrett, C.L.; Chun, H.J.; Minden, M.D.; Moore, R.A.; Marra, M.A.; et al. Reversion to an embryonic alternative splicing program enhances leukemia stem cell self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 15444–15449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Huang, H.; Tang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, D.; Zhong, Z.; Zou, P.; You, Y.; Cao, Y.; et al. CD44v6 chimeric antigen receptor T cell specificity towards AML with FLT3 or DNMT3A mutations. Clin Transl Med 2022, 12, e1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verel, I.; Heider, K.H.; Siegmund, M.; Ostermann, E.; Patzelt, E.; Sproll, M.; Snow, G.B.; Adolf, G.R.; van Dongen, G.A. Tumor targeting properties of monoclonal antibodies with different affinity for target antigen CD44V6 in nude mice bearing head-and-neck cancer xenografts. Int J Cancer 2002, 99, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Asano, T.; Tanaka, T.; Yanaka, M.; Nakamura, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Kawada, M.; Kaneko, M.K.; et al. Antitumor activities of a defucosylated anti-EpCAM monoclonal antibody in colorectal carcinoma xenograft models. Int J Mol Med 2023, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanamiya, R.; Takei, J.; Ohishi, T.; Asano, T.; Tanaka, T.; Sano, M.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Handa, S.; Tateyama, N.; et al. Defucosylated Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody (134-mG(2a)-f) Exerts Antitumor Activities in Mouse Xenograft Models of Canine Osteosarcoma. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2022, 41, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawabata, H.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Kawada, M.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. A Defucosylated Mouse Anti-CD10 Monoclonal Antibody (31-mG(2a)-f) Exerts Antitumor Activity in a Mouse Xenograft Model of CD10-Overexpressed Tumors. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2022, 41, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawabata, H.; Ohishi, T.; Suzuki, H.; Asano, T.; Kawada, M.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. A Defucosylated Mouse Anti-CD10 Monoclonal Antibody (31-mG(2a)-f) Exerts Antitumor Activity in a Mouse Xenograft Model of Renal Cell Cancers. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2022, 41, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, T.; Tanaka, T.; Suzuki, H.; Li, G.; Ohishi, T.; Kawada, M.; Yoshikawa, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. A Defucosylated Anti-EpCAM Monoclonal Antibody (EpMab-37-mG(2a)-f) Exerts Antitumor Activity in Xenograft Model. Antibodies (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateyama, N.; Nanamiya, R.; Ohishi, T.; Takei, J.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Hosono, H.; Saito, M.; Asano, T.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Defucosylated Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody 134-mG(2a)-f Exerts Antitumor Activities in Mouse Xenograft Models of Dog Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Overexpressed Cells. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2021, 40, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takei, J.; Ohishi, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Harada, H.; Kawada, M.; Kato, Y. A defucosylated anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody 13-mG(2a)-f exerts antitumor effects in mouse xenograft models of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Rep 2020, 24, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Ohishi, T.; Kawada, M.; Kato, Y. A cancer-specific anti-podocalyxin monoclonal antibody (60-mG(2a)-f) exerts antitumor effects in mouse xenograft models of pancreatic carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Rep 2020, 24, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Kaneko, M.K. A cancer-specific monoclonal antibody recognizes the aberrantly glycosylated podoplanin. Sci Rep 2014, 4, 5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Nakamura, T.; Kunita, A.; Fukayama, M.; Abe, S.; Nishioka, Y.; Yamada, S.; Yanaka, M.; Saidoh, N.; Yoshida, K.; et al. ChLpMab-23: Cancer-Specific Human-Mouse Chimeric Anti-Podoplanin Antibody Exhibits Antitumor Activity via Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2017, 36, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Yamada, S.; Nakamura, T.; Abe, S.; Nishioka, Y.; Kunita, A.; Fukayama, M.; Fujii, Y.; Ogasawara, S.; Kato, Y. Antitumor activity of chLpMab-2, a human-mouse chimeric cancer-specific antihuman podoplanin antibody, via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Cancer Med 2017, 6, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Roles of Podoplanin in Malignant Progression of Tumor. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, A.; Waseda, M.; Ishii, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Kaneko, S. Improved anti-solid tumor response by humanized anti-podoplanin chimeric antigen receptor transduced human cytotoxic T cells in an animal model. Genes Cells 2022, 27, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalise, L.; Kato, A.; Ohno, M.; Maeda, S.; Yamamichi, A.; Kuramitsu, S.; Shiina, S.; Takahashi, H.; Ozone, S.; Yamaguchi, J.; et al. Efficacy of cancer-specific anti-podoplanin CAR-T cells and oncolytic herpes virus G47Δ combination therapy against glioblastoma. Molecular Therapy - Oncolytics 2022, 26, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiina, S.; Ohno, M.; Ohka, F.; Kuramitsu, S.; Yamamichi, A.; Kato, A.; Motomura, K.; Tanahashi, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Watanabe, R.; et al. CAR T Cells Targeting Podoplanin Reduce Orthotopic Glioblastomas in Mouse Brains. Cancer Immunol Res 2016, 4, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).