1. Introduction

The digital age has produced a large repository of scientific knowledge, creating a larger collection of information than ever before. Decades of research across many disciplines now exist in digital libraries, forming a complex and massive corpus. This opens the door not only to finding specific results, but also to study how science itself is structured and evolves [

1]. Traditionally, the study of science and the relationships between its different fields have been based on citation and authorship data. These methods are useful to show which articles are influential, how researchers collaborate, and how research trends rise and fall [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. However, they mainly focus on the metadata around scientific texts, not on the texts themselves. They reveal connections between sources of knowledge, but they say little about the knowledge inside them. Advances in computational linguistics, from rule-based methods to statistical and machine learning models, have created powerful tools that are now widely used in language technology [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Although these methods are well established for the general language, their use in the specialized language of science is still developing. Science is not a single system; it is a collection of communities, each with its own core ideas, methods, and vocabulary.

In the last century, the field of physics experienced rapid growth and an increasing multidisciplinary environment, as well as developing internal subdisciplines [

19]. Each scientific community develops its own dialect within the shared language of science. For example, the vocabulary of a high-energy physicist, focused on quarks and gauge fields, is measurably different from that of a condensed matter physicist discussing magnetism and phase transitions. This paper faces the problem of how to capture and compare these scientific dialects in a quantitative way. We argue that by applying statistical linguistics directly to the full text of scientific articles, we can better understand the language researchers use to communicate ideas. This allows us to go beyond citation counts and explore the language that defines, distinguishes, and connects scientific fields, creating a unique “linguistic fingerprint” for each discipline.

This effort builds on a tradition of quantitative language analysis, which began in the 1930s with the work of George Kingsley Zipf, who discovered that the frequency of words is inversely proportional to its rank [

20]. This relationship, now known as Zipf’s law, revealed that language has a predictable statistical structure and established that it follows quantitative principles. Similar rank-based analyzes have been applied to many other complex systems [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Modern full text analysis has built on this foundation with methods such as coword analysis to identify thematic content [

31,

32] or map the relationships between keywords [

33]. In addition, in areas such as topic modeling, algorithms such as Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) are used to automatically discover the main research “topics” within a corpus of text [

34]. More advanced methods like Word2Vec or BERT, trained in massive scientific corpora, create mathematical representations of words based on their context [

35]. All of these methods have been used to explore large datasets, including the Google Books

N-gram corpus [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41] and the American Physical Society (APS) literature. In the APS literature, for example, such analysis has shown how research trends emerge due to the Matthew effect [

42]. However, vast territory remains to be explored with new statistical methods.

This work starts from the idea that each subfield of physics has developed its own unique and measurable way of using language. Our study applies statistical linguistic methods to a large set of physics articles from the American Physical Society (APS). We move beyond simple word counts to build linguistic profiles of different subfields. We study both static distributions, as described by Zipf’s law, and temporal dynamics using rank diversity, a recent introduction metric to measure the stability of vocabulary over time [

43,

44,

45,

46].

Our analysis reveals that, while the APS journals share a common scientific language, distinct clusters appear that correspond to closely related subfields. We find that specialized journals tend to reuse the same set of terms, showing a more stable core vocabulary. Although general journals show more diversity, reflecting their wider scope, their core vocabulary is less stable than that of the specialized journals with a more thematic focus. When we compare vocabularies directly, the differences between fields become clearer.

We also extend our analysis from the physics language to the physicists themselves. The language of the field is built on the work of historical figures such as Coulomb, Fermi, and Boltzmann. We study how often these scientists are mentioned in the literature and compare their presence in specialized journals to their broader cultural fame, using the Pantheon dataset based on Wikipedia. The results highlight the gap between cultural fame and ongoing scientific relevance, showing that each subfield maintains its own intellectual history and hierarchy of figures.

More broadly, this study demonstrates that analyzing scientific language can reveal the structure and dynamics of science. By treating the physics literature as a linguistic dataset, we uncover the unique fingerprints of its subfields, marked by stable vocabularies, different rates of linguistic change, and specific sets of historical references. The strength of these patterns allowed us to build a classifier that can predict the home journal of an article based only on word frequencies. This result confirms our central idea: the language of a field is a powerful indicator of its identity. This work provides a new map of physics drawn not from citations but from words and concepts, offering a framework to study how disciplines evolve and how scientific communities preserve their culture through shared language.

The article is structured as follows. We first describe the datasets used for our comparative analysis in

Section 2. The results,

Section 3, are then presented in five parts. We begin by examining word frequency distributions and their temporal variations using rank diversity. Next, we measure the similarity between journals and other text corpora, such as books and social media. Following this, we identify content words that are unique to a specific journal or common across several publications. We then detail the development and performance of an article classifier designed to assign publications to their respective journals based on specialized vocabulary. The results section concludes with an analysis of how frequently prominent physicists are mentioned, comparing their academic visibility with their broader cultural recognition. Finally, we summarize our key findings and discuss their implications in

Section 4.

2. Data

This section outlines the data sources, the collection process, and the preprocessing steps taken prior to the analysis. The dataset used in this study consists of words extracted from articles in the APS historical archive. The specific journals included in our analysis, along with their abbreviations and scopes, are listed in

Table 1. A statistical summary of the dataset, detailing the number of articles, total words, and unique content words obtained for each journal, is presented in

Table 2.

Data was obtained using the APS Harvesting API, with access granted by the APS Publisher’s Office in collaboration with the Chief Information Officer. The original articles were retrieved in PDF format, from which plain text was extracted. Since text in PDFs is stored as a sequence of drawing instructions in the content stream, text extraction required careful handling to ensure correct character encoding and ordering. However, the extracted text was not always perfectly accurate and required further cleaning and processing.

To refine the dataset, punctuation marks and non-existent words, such as

ergies,

DePaxtnzent, and

vrvrvv, were removed. Additionally, function words were filtered out to retain only content words.

1 The function words were removed using Google’s

Stop-Words project [

47]. In addition, operators, numbers, and words that contain numerical values were excluded. In

Table 2 we present the number of articles, unique content words, and total words obtained from the dataset.

For comparison purposes, two additional datasets from previous studies were incorporated. The first dataset comprises words from English books recorded in the Google Ngrams dataset between 1800 and 2008 [

36], specifically considering the words highest ranked in the latest available year (2008). The second dataset consists of words from geolocated tweets in New York City collected between January and October 2014 [

46,

48].

To further analyze word patterns, we constructed N-gram blocks (). A 1-gram (monogram) represents a single word, a 2-gram (bigram) consists of two consecutive words, and so on. These N-grams were constructed without function words. For example, the sentence "quantum phase transition" yields two 2-grams: ("quantum phase", and "phase transition").

The entire project was implemented using the Python programming language. Executable files, datasets, visualizations, and all relevant materials necessary to reproduce the results are available upon request from the authors.

3. Results

3.1. Frequency and Rank Diversity

Our statistical analysis begins with an examination of word frequency and temporal variations in word usage. To analyze the first, we compare the dataset with Zipf’s law. This step is not just for verification; we will later use the properties of Zipf’s law to develop and test the formulas for our methods. For the latter, we quantify the changes over time using diversity.

To ensure comparability in the calculation of word frequency and rank diversity between journals, the dataset was standardized to contain the same number of words within a fixed year range while preserving the original word distribution for each journal. A new dataset was constructed covering the years 2012–2017 (to ensure a sensible comparison with PRX, which started publishing in 2012). Word selection followed the roulette wheel selection method, which maintains the same word distribution across journals. This method assigns a fitness value

to each word

i within the journal dataset. The probability of selecting the word

i is given by:

where

n represents the total number of words in the dataset. Since the probability of selection is proportional to fitness, the word distribution in the selected subset mirrors the original distribution of the dataset.

Zipf observed a universal tendency in large corpora where words ranked by frequency follow a power-law of the form

, where

k represents the rank of the word and

f denotes its relative frequency [

23,

49]. Higher-ranked words appear more frequently, while lower-ranked words are rarer. This pattern, now known as Zipf’s law, extends beyond linguistics to various social and physical phenomena. However, Zipf’s law provides only a rough approximation of precise statistics in rank-frequency distributions in languages.

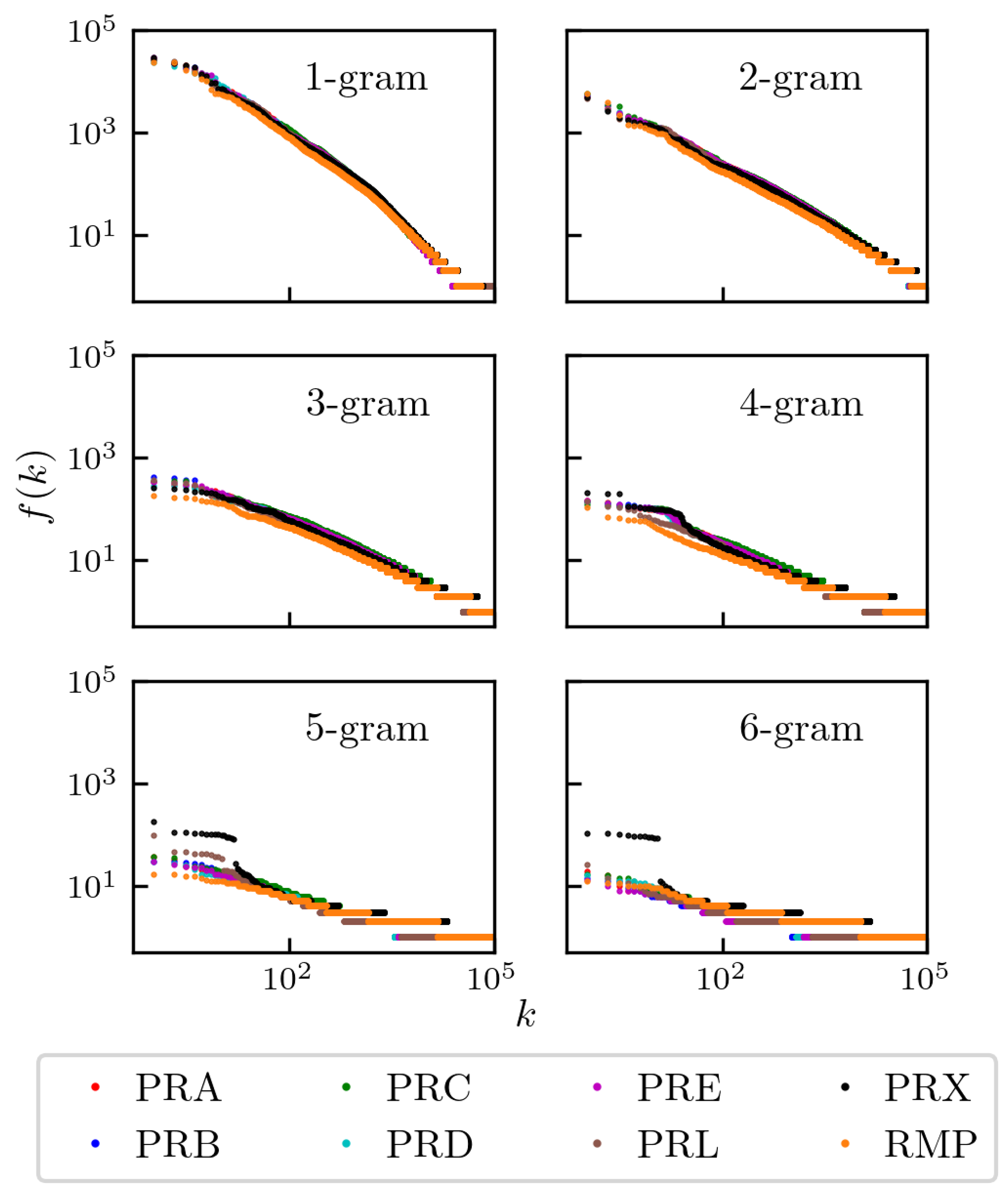

Figure 1 shows the frequency distribution of

N-grams in journal articles from

to 6. As expected, single words (1-grams) occur more frequently, with their distribution exhibiting a near-linear decline on a log-log scale, consistent with a slope of approximately

, in agreement with Zipf’s law. As

N increases, the absolute frequency of

N-grams naturally decreases as longer sequences of words are less likely to occur. In particular, a plateau emerges for

, 5, and 6, reflecting the prevalence of standardized phrases commonly used in publications, such as those published by the APS. Interestingly, deviations from the expected power-law behavior are more pronounced for

, although the overall trend remains consistent with Zipf’s law.

Another interesting detail is the large relative number of common 6-grams observed for PRX. This is due to new phrases added to publications, such as published by the American Physical Society. This phrase was added around 2014, but since PRX was published since 2011, the relative frequency of the phrase has changed.

We aim to quantify how the usage of words—or more generally,

N-grams—evolves over time.

Rank diversity, denoted as

, measures the variability of words occupying a specific rank

k over a series of time intervals [

41,

43]. It is defined as the ratio between the number of distinct words observed in rank

k in all time steps and the total number of time intervals. A maximum rank diversity of

occurs when a completely different word appears at rank

k in each time step, indicating maximal variability. In contrast, lower values of

suggest that the same word or a limited set of words consistently occupies that rank. Thus, rank diversity serves as a measure of the temporal dynamism of

N-grams, providing insight into the stability or fluidity of word rankings within a dataset. Remarkably, universal behavior has been observed in a wide range of systems: in open systems, rank diversity tends to follow a displaced and rescaled error function - hereafter referred to as a sigmoid - that provides an excellent fit to empirical data in various domains [

43,

50,

51]. This characteristic has even emerged from extremely simple models [

51].

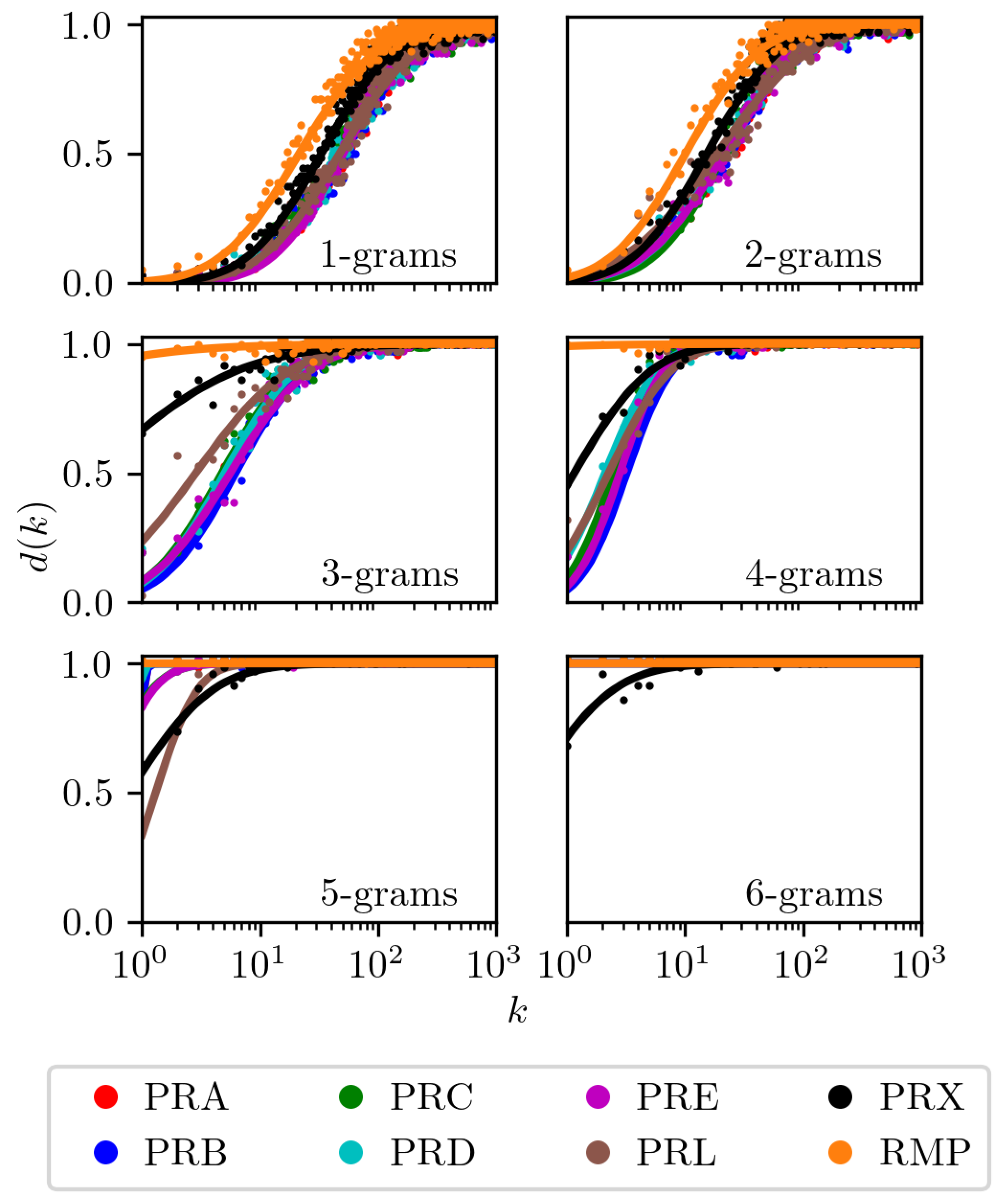

The results for a one month time step are presented in fig.

Figure 2; similar patterns hold for other time steps. We show rank diversity for all journals and all

N-grams considered in this study. We also include fits to the error function, where both the center and width of the corresponding Gaussian serve as fitting parameters (see [

43] for methodological details). To ensure a fair comparison, we restricted the analysis to data collected between 2011, when PRX was first published, and 2017.

Analysis of the rank diversity curves in

Figure 2, reveals several key findings. First, the empirical data are closely aligned with the sigmoid functions fitted across all datasets, confirming the robustness of the ansatz proposed in [

43]. As anticipated, we observed low diversity at the top ranks, indicating the consistent dominance of a small set of high-frequency words. For 1-grams, higher ranks show increased diversity, reflecting greater lexical variation. Specialized corpora, exemplified by domain-specific journals, consistently exhibit lower 1-gram diversity, suggesting a more stable and restricted vocabulary. In contrast, corpora from general journals display higher 1-gram diversity, consistent with their broader topical scope and greater linguistic variability. For higher order

N-grams (2- to 6-grams), rank diversity captures changes in phrase usage. Higher

values at these levels suggest significant changes in multi-word expressions over time. In particular, journals with similar thematic content often show similar diversity patterns for both 1-grams and higher-order

N-grams, implying shared discourse structures or terminology.

3.2. Similarity

We analyze and compare the frequency-based ranking of words in different journals to identify linguistic affinities and divergences. Furthermore, we include a comparative analysis with

N-gram corpora derived from published books [

41] and Twitter [

46] to distinguish the lexical characteristics of scientific literature from those of other language domains.

We consider the

rank-biased overlap (RBO) distance [

52], which quantifies the similarity between the ranked lists. This measure was preferred over others as it maximized the differences between journals. RBO is defined as:

where

A and

B are the lists being compared,

represents the ranking depth, and

is the number of common elements

A and

B up to depth

k The term

denotes the proportion of agreement between

A and

B. The parameter

p (ranging from 0 to 1) controls the emphasis on the top-ranked elements; for values closer to 1, the weights

last longer and

vice versa. An RBO value of 0 indicates that both rankings in fact have no elements in common (up to

). We set

, for which equation

solves to

, and it is expected that the measure converges on the same range scale. A further refinement proved useful: distinguishing content words from function words.

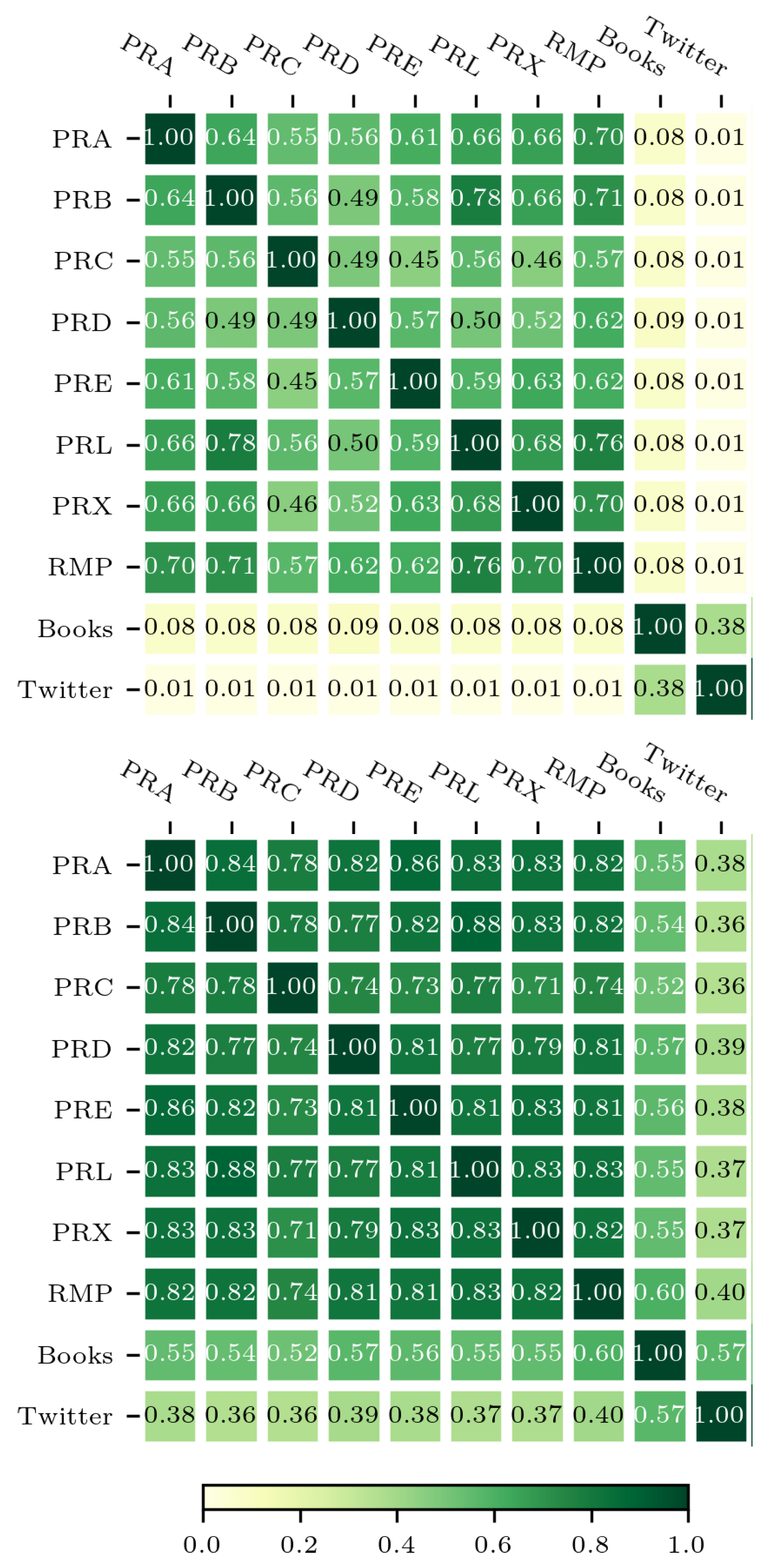

When we consider only content words, which communicate the primary meaning of a text, the similarity results are notably different from those based on the complete vocabulary. The function words are highly frequent and often dominate lower ranks, thereby significantly influencing overall similarity measures. As shown in

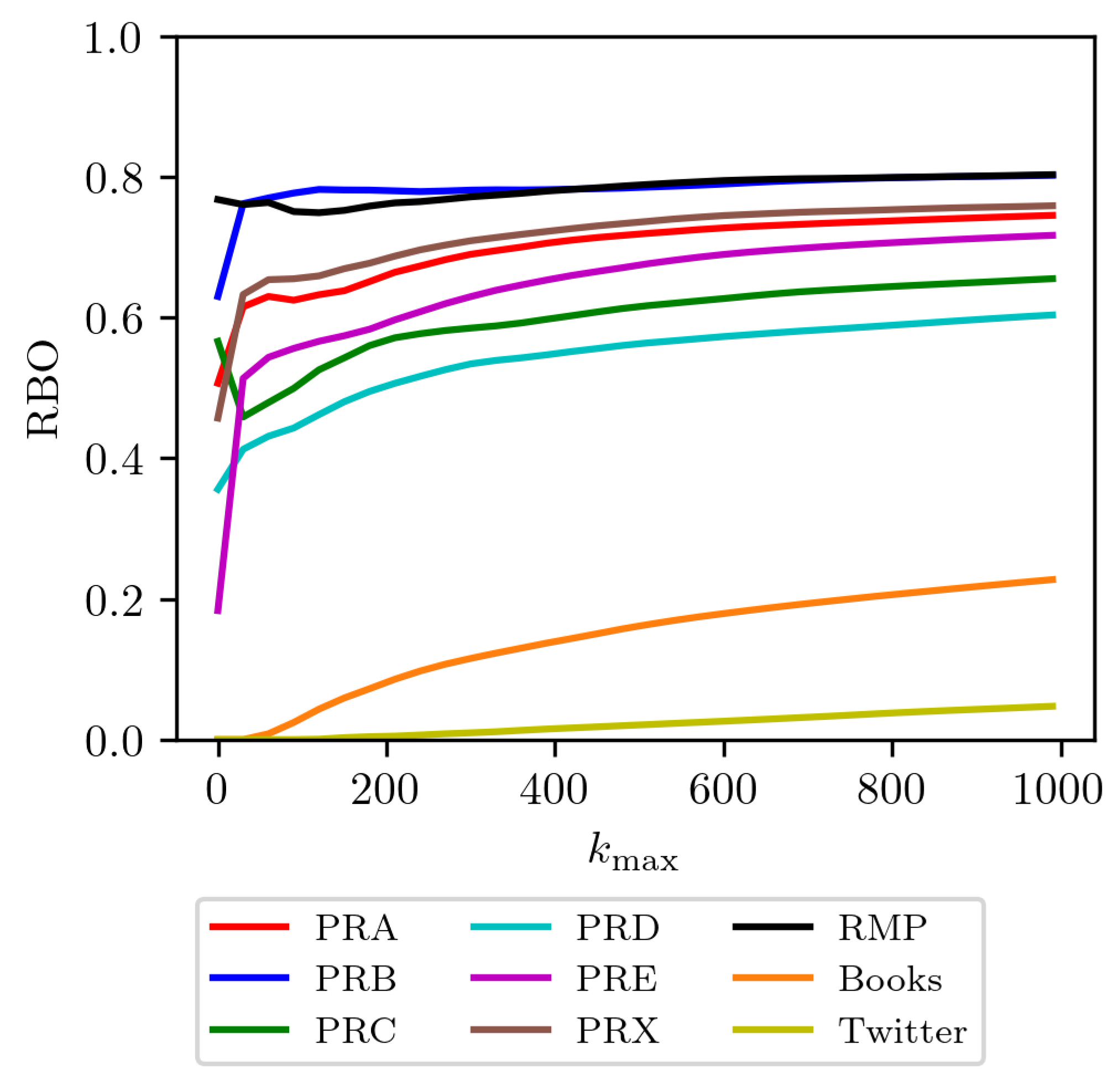

Figure 3, a restricted analysis to content words is crucial because function words can obscure more meaningful comparisons between datasets. In this context, PRL shows the highest similarity with PRB and RMP. In contrast, PRC exhibits the least similarity with PRE and PRX. This suggests that in academic publishing, the degree of shared core vocabulary depends on the specific thematic focus. We also tried similarity comparisons using PRX and RMP journals, finding the same trend of results.

Our findings indicate an important difference between different types of text. The Twitter dataset is the most different, showing a large dissimilarity to academic journals and an even greater dissimilarity to books. In contrast, books and academic journals share a moderate amount of vocabulary. By far, the highest similarity is found among the different APS journals themselves, regardless of their specialized subfields. This suggests a basic consistency in scientific language that goes beyond specific disciplines. However, once function words are included in the analysis, the overall similarity across all datasets, including journals, books, and Twitter, increases considerably. This is expected as function words form a universal grammatical backbone across diverse forms of written communication. Despite this increasing similarity with the inclusion of function words, the distinct patterns of lexical usage remain evident, especially the strong dissimilarity of Twitter due to its informal language, slang, and the use of emojis, hashtags, and user name mentions.

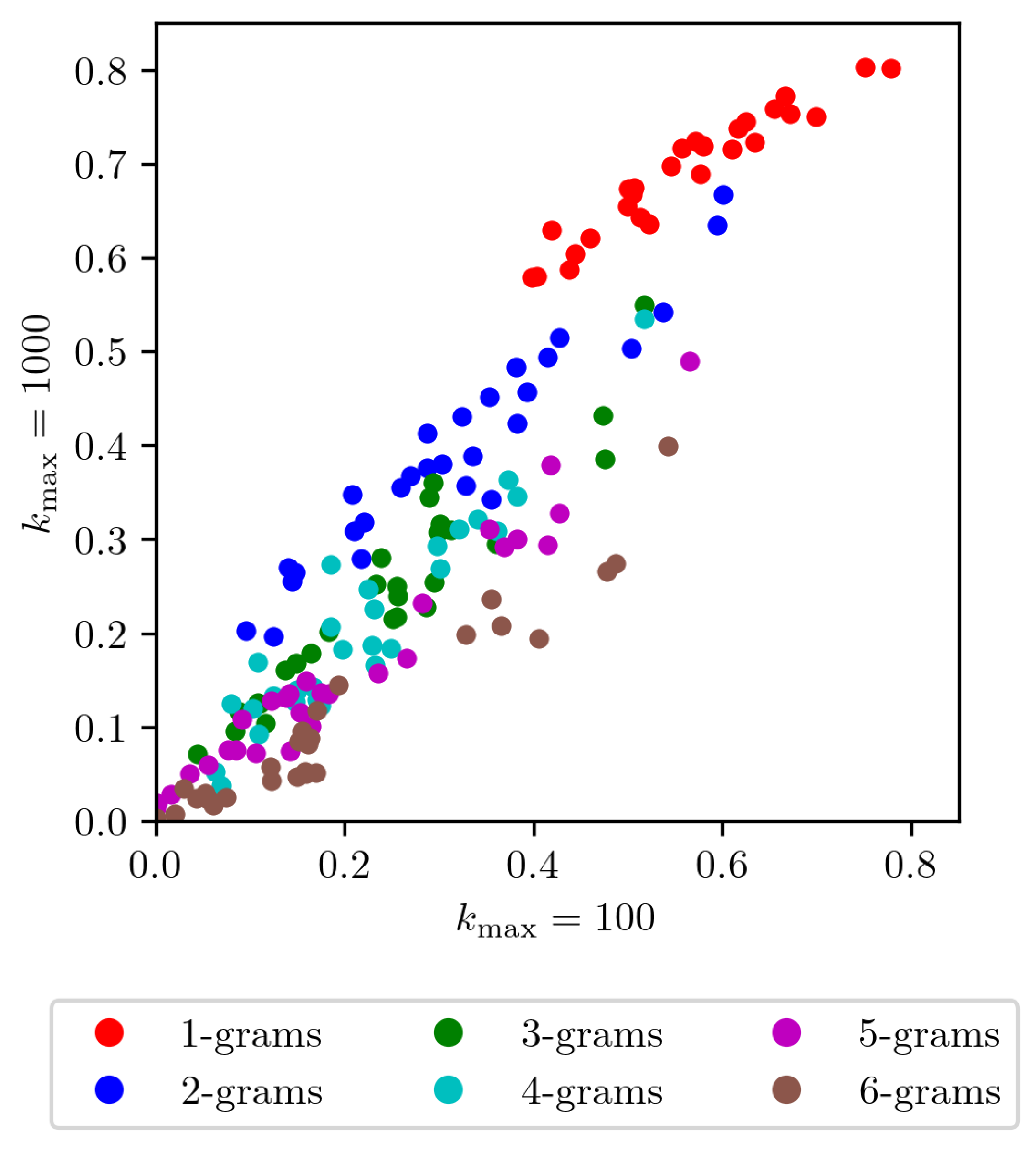

Figure 4 presents a scatter plot that compares similarities at different ranking depths (

vs.

). Each point represents the similarity between pairs of journals, with colors indicating different

N-gram groups. Our analysis reveals that the number of words used does not significantly alter the findings related to ranking depth. For 1-gram, all similarity values consistently exceed

, indicating stability and reliability in the ranking data. This high similarity suggests a consistent core vocabulary and robust ranking across different depths, implying that the relative order of individual words remains largely preserved. Conversely, a low similarity would have suggested unstable or random word rankings. This would imply that the journals share no meaningful core vocabulary and that their top-ranked words are noise rather than reflection of a stable, shared thematic focus. This observed consistency in 1-gram rankings provides a strong foundation for further analysis. As the value of

N increases, we observe a corresponding decrease in the similarity of ranks, suggesting that while individual word usage is relatively stable, the usage of multi-word expressions becomes more dynamic and less consistent across different contexts.

Figure 5 shows the change in similarity as the word count increases for PRL compared to other APS journals, Twitter, and English-language books. We observe that similarity values stabilize at distinct levels: the values for other APS journals are relatively high, stabilizing between approximately 0.5 and 0.8, while the similarity with books is much lower, stabilizing around 0.25, and the similarity with Twitter is near zero. This stabilization is consistent with the fundamental differences in language use between these distinct corpus. Academic journals, such as those published by the APS, are intended for specialized audiences and employ precise field-specific terminology. Books, while often descriptive, maintain a more formal linguistic style. In contrast, Twitter prioritizes brevity and expressiveness, leading to the use of informal language and unique structural conventions. The point at which similarity stabilizes, alongside the maximum value of

k (

) considered in the ranking depth, is important to understand the extent of lexical overlap. Our findings suggest that similar stabilization patterns and the influence of

might be observed in other comparative analyzes involving diverse text corpora.

These findings highlight the distinct linguistic characteristics of different textual sources, such as books, academic articles, or social media, tend to use different vocabulary, grammar patterns, or word frequencies. Each type of text reflects its own linguistic fingerprint; for example, academic texts can favor formal structures and specialized vocabulary, while social media posts might use more casual language [

53].

3.3. Unique and Common Content Words

In this section, we identify both common words shared among different journals and distinctive words to each one. This analysis provides insight into key concepts used to communicate physics while also highlighting specialized terminology characteristic of individual journals.

Table 3 displays the 20 most common words in the five specialized journals. Within this top-20 list, words that are unique to a single journal are in italics, while words common to all five journals are in bold. Notably,

energy, a fundamental concept in physics, appears as a common term. Other frequently occurring words in journals include

functions,

results, and

values, all of which play a crucial role in conveying scientific findings. In contrast, words unique to each journal reflect their specific research focus. For instance, in PRA, distinctive terms include

quantum,

wave,

laser,

electron, and

atoms, all of which align with topics commonly discussed in that journal.

The uniqueness of a word is measured by its lifetime ranking. That is, the range of ranks that starts from its highest position in one journal down to the rank at which it first appears in a second journal. For example, the term

system first appears in PRE at rank 2, and its lifetime (the range where it remains unique) extends to rank 8, when it also appears in PRA. The list of unique words, along with their corresponding lifetime ranking, is compiled in

Table 4. The duration of this range serves as an indicator of its characteristic relevance to a journal. For example,

laser (PRA),

magnetic (PRB),

nuclear (PRC),

gauge (PRD), and

dynamics (PRE) all exhibit long rank ranges, reinforcing their strong association with each respective journal. In contrast, words with a short range, such as

transition in PRB or

model in PRE, may represent statistical fluctuations rather than distinctive terminology.

Examining common words across journals also provides valuable information. In

Table 3, energy becomes common in rank 6, highlighting its fundamental role in the physics discourse.

Table 5 presents a list of common words, the rank at which they become common, and their corresponding rank in English-language books [

36]. This comparison reveals that many essential physics concepts (e.g.,

energy) and mathematical terms used in physics (e.g.,

function) are distinctive across journals. Furthermore, words such as

same, while not necessarily central to physics, exhibit similar ranking patterns to those found in general English usage.

3.4. Article Classifier

We developed a classifier that relies solely on word rankings within each journal and each article. This section describes the algorithm and its performance.

To identify distinctive words for each journal, we introduce a measure called the

specialization factor, denoted by

, with

w a given word and

i a given journal. It is defined as the ratio between the second-highest rank

of the word

w in the other journals and its highest ranking

in the journal:

notice that

. Assuming Zipf’s law, this ratio reflects the relative frequency of word usage in different journals. For the purpose of this calculation, the word is assigned to the journal where it is the most frequent (i.e., has the highest rank). For example, as shown in

Table 3, the word

states appear with a rank of 2 in PRA and a rank of 5 in PRC. Therefore, its specialization factor for PRA is

. The specialization factor also depends on the number of words considered. For example, the word magnetic has a rank of 4 in PRB and 121 in PRA. If only the top 100 words are considered, then the word magnetic is unique within this range and the final rank is set to 101, resulting in

. If the first 1,000 words are considered, its final rank remains 121, resulting in

. As more words are included, different terms emerge as distinctive for each journal.

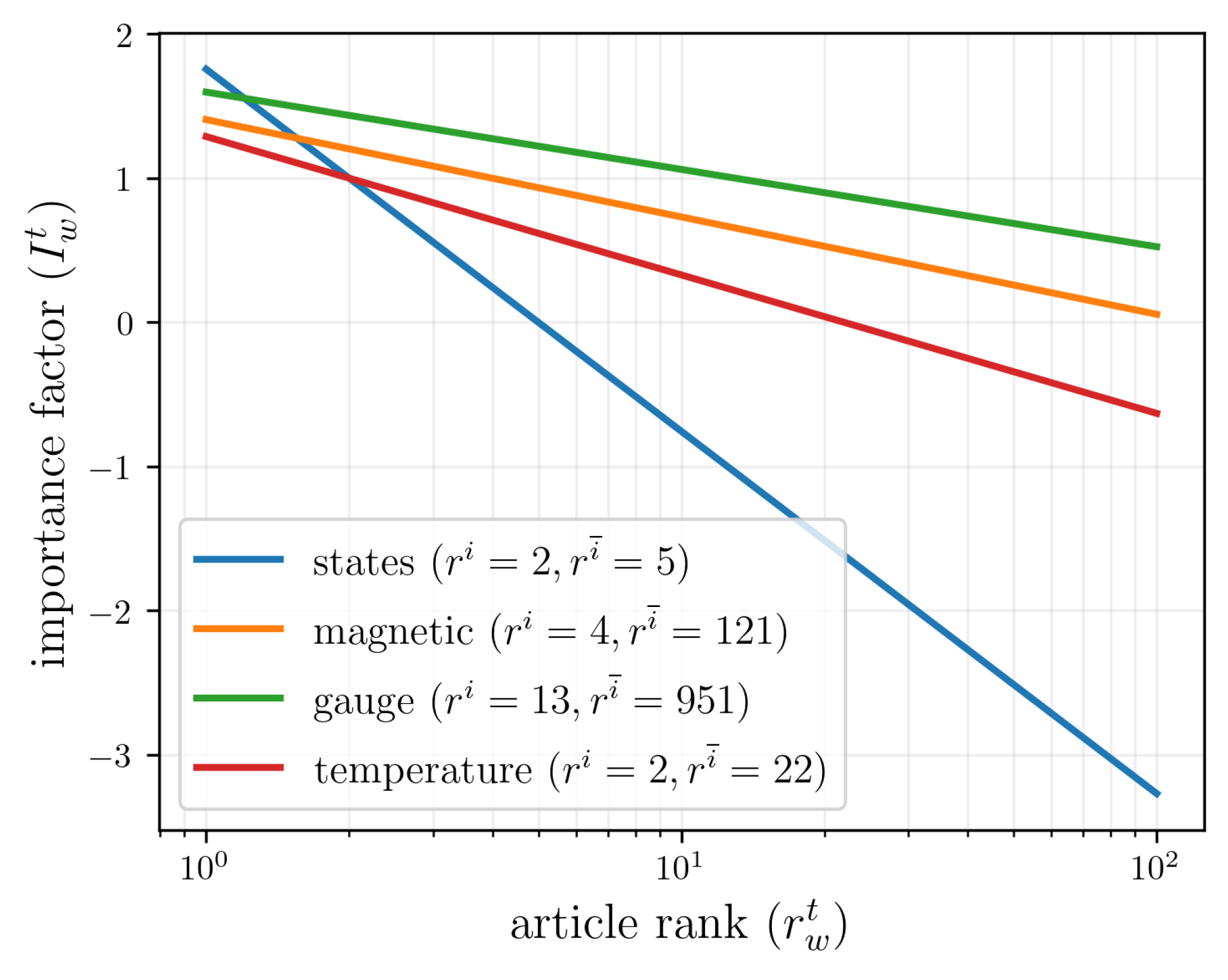

To classify an article, we assess the significance of each word within it relative to the journal where the word holds the highest rank. This is measured using the importance factor, defined as:

The importance factor

is designed to measure the relevance of a word relative to its established journal-specific importance. The factor is defined by two key benchmarks. It equals 1 when the rank of a word in the article is identical to its rank in its primary journal (

), as the numerator and denominator of eq. (

2) become equal. It equals 0 when the rank of an article matches the rank of a word in the next-closest journal (

), as the numerator becomes zero. Consequently, the factor can exceed 1 if the word is ranked even higher in the article (

), as seen in fig.

Figure 6. In contrast, the factor becomes negative if the rank of a word in the article is even lower than its rank in the next-closest journal (

). Again, using Zipf’s law, the importance factor can also be interpreted in terms of word frequency instead of rank.

For example, the word

temperature appears in PRB at rank 2 and next at rank 22. If an article contains temperature at rank 1, the importance factor is approximately

. However, if the same word appears in rank 400, its importance factor is considerably lower and negative (

,

), as

Table 6 illustrates for different word ranks.

Figure 6 shows the behavior of the importance factor

as a function of the rank of a word in an article

. We plot four words in

Table 4 with different degrees of specialization:

states (a weak classifier with a small specialization gap,

),

quantum (a medium classifier,

),

magnetic (a strong classifier,

) and

gauge (the strongest classifier with a long lifetime rank,

) . The plot visually confirms that the specialization of a word is the key to its classification power.

We are now ready to describe the algorithm to classify articles, which is based on the importance factor of the words contained in the text, compared to the words with a high specialization factor of each journal. In particular, for each article and each journal, we identify the specialized words of the journal present in the article, its associated importance factor (with respect to the article), and its specialization factor (with respect to the journal). We then add the importance factors of all words that have a specialization factor greater than the threshold value . This threshold acts as a filter, ensuring that only words highly indicative of a specific field contribute to the classification, and plays an important role to increase the accuracy of the algorithm. After calculating this score for all possible journals, the article is classified in the journal that maximizes such score. This approach allows us to classify articles based on the unique and important vocabulary that best defines the scope of different journals.

The algorithm was evaluated using random samples of 500 articles per journal.

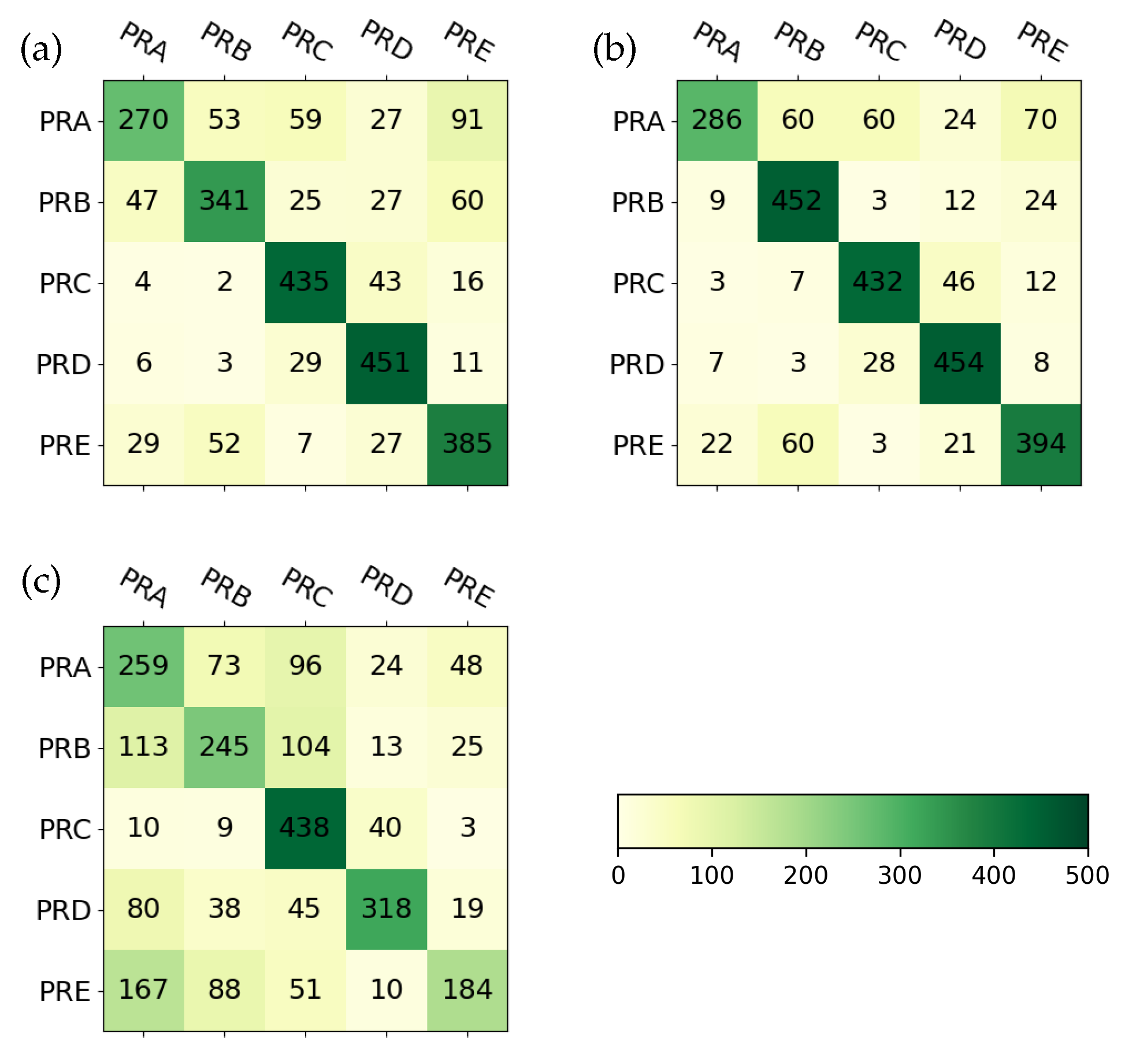

Figure 7 presents the classification results, where the rows indicate the correct journal and the columns show the predicted classification. The number of words used to calculate the specialization factor was varied during the analysis.

The confusion matrices for a threshold specialization factor of on different word counts (100, 1,000, 10,000), demonstrate how increasing the number of words significantly improves classification accuracy. While 100 words lead to notable misclassifications, 1000 words substantially reduce errors, suggesting that this range captures enough field specialized vocabulary to differentiate between specialized journals effectively. Further increasing to 10000 words shows diminishing returns (typical articles have a few thousand unique words, for example, this one has approximately 7000 unique words), indicating an optimal vocabulary size for effective classification. For example, when 100 words were used, 73 articles from PRA were misclassified as belonging to PRB. Increasing the number of words from 1000 to 10,000 led to slight improvements in classification accuracy. In particular, PRA articles showed lower classification performance, likely due to the overlap of vocabulary with multiple journals. Articles from PRE were frequently misclassified as belonging to PRA or PRB.

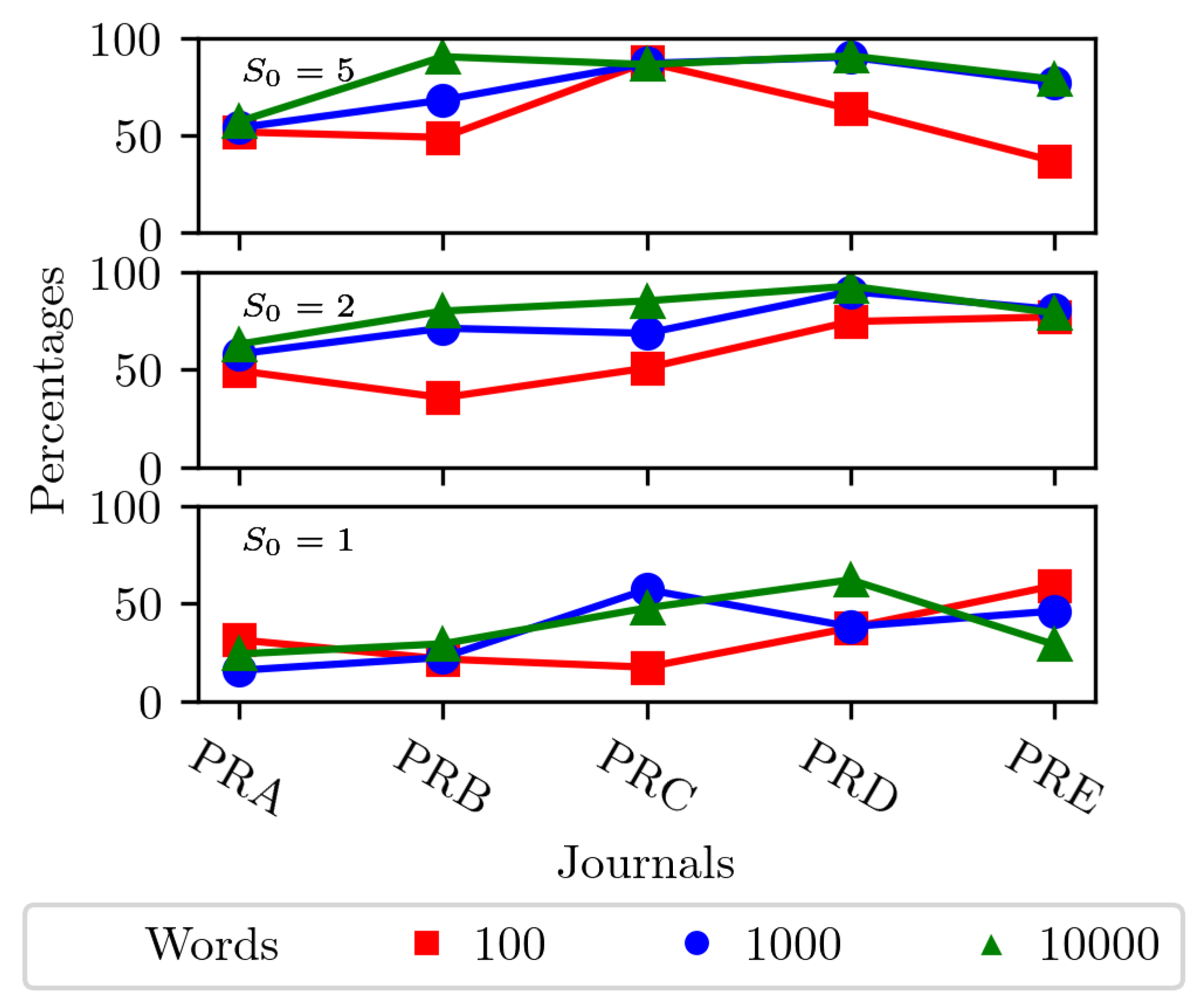

Figure 8 presents the number of articles correctly classified for each journal as a function of the specialization factor. Increasing the number of words beyond 1000 provided only marginal improvements. A specialization factor threshold of 5 yielded the best results, balancing the number of words used with the classification accuracy. These findings suggest that specialized terminology plays a crucial role in distinguishing between journals, more so than simply increasing the number of words considered.

This implies a natural limit to the performance of the classifier; it can be conjectured that it is impossible to obtain a perfect classification with this dataset, as there are relevant overlaps among the journals.

3.5. Physicists Mentions

To examine the distinction of scientists in the academic literature, we analyzed the most frequently mentioned physicists in the scientific journals included in this study, comparing their presence across specialized and general physics publications. We aim to understand how the visibility of these figures varies across different fields and how this relates to their broader recognition.

To investigate the presence and influence of important physicists in academic communication, our study used a list of 200 influential physicists. This list was compiled from the Pantheon project [

54,

55], a resource that uses Wikipedia data to quantify the attention historical figures receive in different language editions. We chose the Pantheon list because it provides a robust measure of a physicist’s general cultural impact and recognition beyond purely academic citations, offering a broader perspective on their public visibility. Using this list, we analyzed the frequency of physicist surnames within the Physical Review journals. It is important to note that our analysis is based solely on surname mentions. This approach introduces some ambiguity, as a surname can refer to the physicist themselves, their associated concepts (e.g., “Faraday’s law” rather than Michael Faraday, or the Coulomb unit of electric charge, rather than Charles-Augustin de Coulomb), or appear as a bibliographic reference (e.g., “Anderson”). Furthermore, some names, such as “Curie,” are ambiguous and could refer to Marie or Pierre Curie, which our method does not differentiate.

Table 7 and

Table 8 show the ranks of physicists based on the frequency of mentions within the APS journals.

Table 7 tracks the ten most recognized physicists according to Pantheon) and lists their rank within each of the eight journals.

Table 8, on the other hand, identifies the top 10 physicists most frequently mentioned for each of the eight journals individually, showing which historical figures are the most prominent within each specific area. These rankings reflect the frequency with which a physicist’s name appears in the content of a given journal, rather than their overall scientific importance or impact. These tables show that the importance of a physicist, as indicated by mention frequency, varies significantly across different subfields. For example, Röntgen, a Nobel laureate famous for his work on X-rays, does not have a high frequency in PRA, which focuses on atomic, molecular, and optical physics. This discrepancy shows that even highly celebrated figures might not be frequently cited by name in every domain, especially if their foundational work has become so fundamental that their direct attribution is less common than the use of concepts or units derived from their work. Comparing the rankings across these tables reveals which physicists are most frequently mentioned by name within specific areas of physics. This comparison highlights the specialized lexical relevance of historical figures for current research in different areas. For instance, a physicist who ranks highly in PRC (nuclear physics) but low in other journals demonstrates a concentrated influence, indicating that they are a subject of ongoing discussion primarily within the nuclear physics community.

We observed a significant divergence, confirmed by a low correlation, between the rankings derived from journal mentions and those from the Pantheon project, which measures broader cultural recognition. This disparity highlights the difference between broad cultural impact and specific scientific citation practices. Pantheon captures the social and historical impact of a physicist, while journal mentions reflect direct contributions within specialized research domains. For example, Isaac Newton, ranked first in Pantheon for his widespread cultural impact, is rarely mentioned by name in the journals, as his contributions are embedded in laws or units (like “N”). Similarly, the legacy of a physicist is often invoked through derived units, such as MegaElectronVolts (MeV) in PRC (

Table 3). This pattern suggests that the scientific legacy of a physicist, encapsulated in concepts, laws, or units, is more deeply integrated into the discourse than their direct personal mention, demonstrating that the criteria for "prominence" vary significantly between general cultural and specialized scientific contexts.

To further refine our analysis, we specifically looked at the context in which certain surnames appeared in the articles. This allowed us to distinguish between mentions of a physicist’s contributions or their direct person, and instances where their name simply appeared in a bibliographic reference.

Table 8 illustrates this challenge, as the high frequency of common surnames listed there, such as ’Chen’ and ’Lee’, makes it difficult to determine if they are being mentioned for their contributions or are simply appearing in bibliographic references. Surnames such as Chen, Lee, and Anderson frequently appear in reference lists. Without analyzing the surrounding text, it is difficult to determine if these are citations to a specific individual’s work, or common surnames of different authors in the bibliography. This contextual analysis is important for accurately assessing the distinction of physicists based on direct discussion rather than incidental referencing.

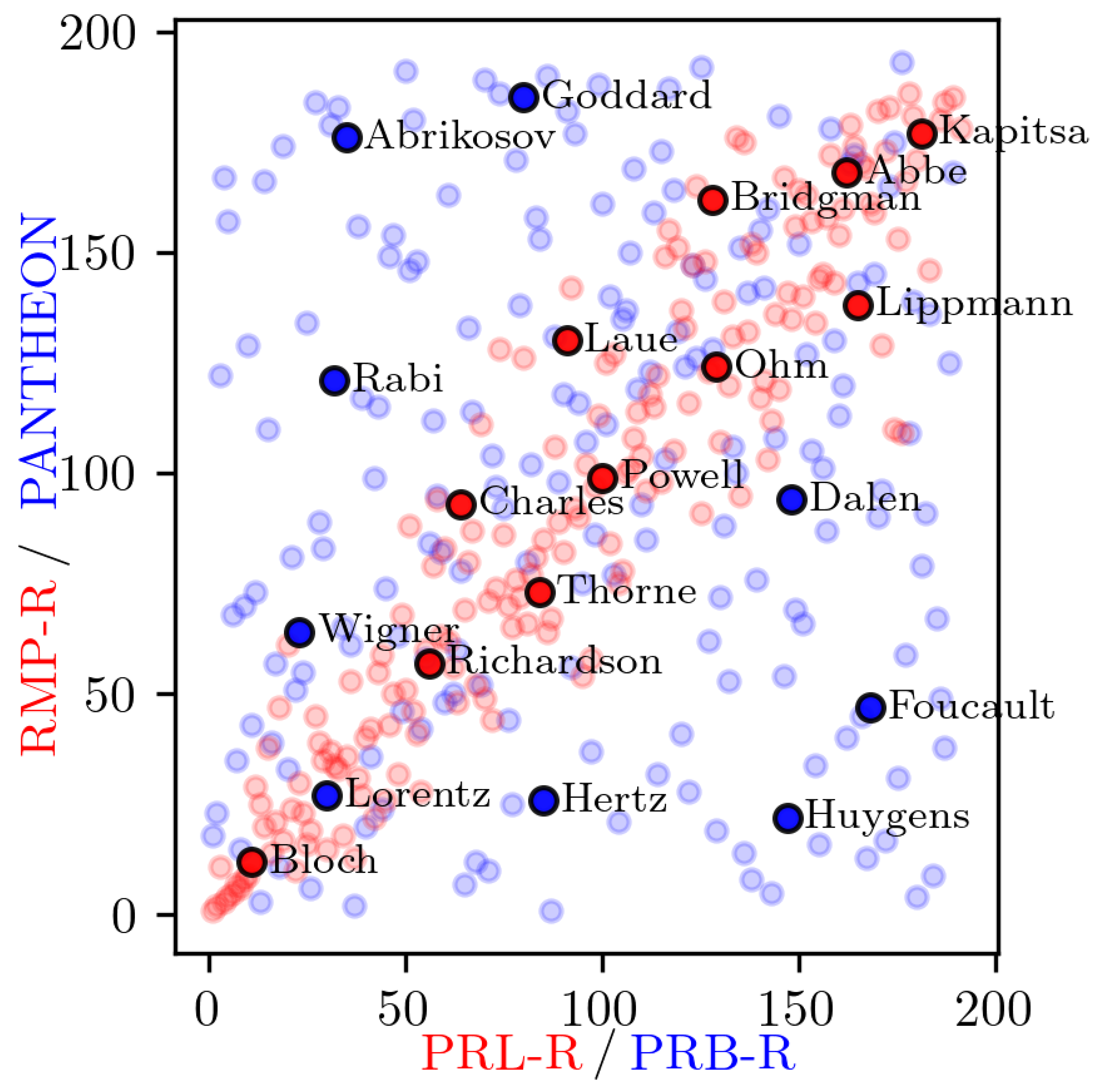

To examine the consistency of the physicist ranking in different contexts, we compared the Pantheon ranking with those derived from the Physical Review journals (

Figure 9). This analysis revealed a divergence: the rankings within specialized journals showed a low correlation with Pantheon’s broad cultural rankings. In contrast, the two general physics journals, PRL and RMP, exhibited a strong positive correlation in their physicist rankings. This strong alignment indicates that these broader journals tend to prioritize a similar set of physicists, likely reflecting a shared purpose of covering foundational or widely impact research across the discipline.

These observations are quantitatively supported by the Pearson correlation coefficients presented in

Figure 10. These coefficients measure the linear similarity between the Pantheon rankings and the relative rankings within APS journals. This relative ranking was necessary because the journals vary massively in size and total word count. Using raw mention counts would be misleading. Therefore, physicist surnames were ranked according to their frequency within each specific journal, creating a normalized list. In the figure, the "-R" suffix (e.g., "PRA-R") denotes this normalized relative ranking, which can then be fairly compared to the Pantheon rankings. The consistently low correlation values between Pantheon and the specialized journals, in addition to the high values between PRL and RMP, confirm the distinction between cultural impact and specialized academic citation patterns. These results indicate that general journals tend to have a more unified perspective on impactful physicists, while specialized journals reflect the specific interests of their respective subfields.

We also found that specialized journals like PRB and PRD were less similar in the number of physicists they mentioned compared to the more general journals. This is a logical result of their specialization; because they focus on different areas within physics. Each journal tends to highlight the physicists most relevant to its own specific topics. In contrast, general journals, by their very nature, provide a broader spectrum of physics topics. An interesting case in point is PRX. Although classified as a general physics journal, its relative novelty and different publication history compared to established journals such as PRL and RMP may contribute to its somewhat distinct correlation profile. First, the relative novelty of PRX is shown in

Table 2, since its publication history is 2012–2017, shorter than PRL (1959–2017) or RMP (1930–2017). Second, it has a different correlation profile as shown in

Figure 9, where the Pearson correlation between PRL and RMP is very high (0.93), but the correlation of PRX with both is lower (0.84 with PRL and 0.78 with RMP).

Our analysis shows variations in how frequently notable physicists are mentioned in different academic journals. These differences highlight the specific thematic focus of specialized journals, where certain physicists are highly relevant, versus the broader cultural recognition these physicists achieve, as captured by the Pantheon project.

4. Conclusions

Taking advantage of the large amounts of data accumulated by the American Physical Society over decades, complemented by corpora from Google Books, Twitter, and the Pantheon project, this study performed a quantitative comparison of eight physics journals (five specialized and three general). Our analysis reveals a duality in scientific communication; while all physics subfields are built upon a shared linguistic foundation, each possesses a unique and quantifiable "fingerprint" that distinguishes it.

This study demonstrates that the specialized corpus of physics journals follows the universal laws of statistical linguistics. This quantitative baseline, established by analyzing word frequencies and temporal rank diversity, provides the necessary foundation from which to measure the distinct linguistic fingerprints of each subfield, which we explored using the RBO distance and a classifier. The first part of this baseline is that word rank distributions for all journals are similar, following a scale-free, Zipf-like structure. This finding shows that the highly specialized and technical language of physics is not a purely artificial construct but is governed by the same fundamental principles of efficiency and organization that shape natural human language. Secondly, the temporal rank diversity for small N-grams is approximated by a sigmoid curve across all journals. This universal shape reveals a common dynamic in scientific communication: a highly stable core vocabulary of fundamental concepts (low diversity at top ranks) coexists with a rapidly evolving "research front" of new terms and specialized vocabulary (high diversity at lower ranks). Together, these shared statistical properties establish common linguistic foundations for all physics.

Moving beyond this shared baseline, the unique identities of the journal emerge in longer N-grams. We quantified these differences using the RBO distance, finding this method most revealing when restricted to content words. This approach filters out function words, isolating the specialized vocabularies that define the thematic focus of each journal and allowing the identification of unique and common terms.

Using distinctive content word rankings, we developed an article classifier that is capable of determining the journal in which an article was published based on the unique distribution of its content words. A proposed importance factor proved crucial in assigning the relevance of each word to the classification process. Finally, we compared the frequency of physicists’ surnames in the journals against their general popularity ranking in the Pantheon. The results show a high correlation in mentions among interdisciplinary journals, medium correlations among disciplinary journals, and a very low correlation with Pantheon rankings, suggesting that "fame" is highly contextual.

These results represent a modest step toward a deeper understanding of the evolution and communication of science. We believe that this work demonstrates significant potential for applying statistical linguistics to large-scale datasets. A natural next step would be to extend this analysis to journals in other specific fields, such as chemistry, biology, or engineering, as well as to other interdisciplinary journals. Such research would enable comparisons within and among different scientific disciplines, helping to map their similarities and differences on a broader scale.

Acknowledgements

Jorge Flores and Sergio Sánchez collaborated in the initial stages of this investigation. Alfredo Morales provided the Twitter data. CP acknowledges support by UNAM-PAPIIT IG101324, SECIHTI CBF-2025-I-1548 and UNAM PASPA–DGAPA. CP acknowledges financial support from the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research via the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG) through the project FO999921415 (Vanessa-QC) funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU.

References

- Wang, D.; Barabási, A.L. The Science of Science; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingers, J.; Leydesdorff, L. A review of theory and practice in scientometrics. European Journal of Operational Research 2015, 246, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.; Tupikina, L.; Santolini, M. Mapping the physics literature with a network of 27,770 papers: A study of publication and citation patterns. PLOS One 2022, 17, e0270131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Solla Price, D.J. Networks of Scientific Papers. Science 1965, 149, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, H. Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 1973, 24, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, S.; Bergstrom, C.T.; Börner, K.; Evans, J.A.; Helbing, D.; Milojević, S.; Petersen, A.M.; Radicchi, F.; Sinatra, R.; Uzzi, B.; et al. Science of science. Science 2018, 359, eaao0185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuchty, S.; Jones, B.F.; Uzzi, B. The Increasing Dominance of Teams in Production of Knowledge. Science 2007, 316, 1036–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redner, S. Citation Statistics from 110 Years of Physical Review. Physics Today 2005, 58, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzi, B.; Mukherjee, S.; Stringer, M.; Jones, B. Atypical Combinations and Scientific Impact. Science 2013, 342, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, K.; Liberman, M. The Future of Computational Linguistics: On Beyond Alchemy. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2021, 4, 625341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, P.F.; Cocke, J.; Pietra, S.A.D.; Pietra, V.J.D.; Jelinek, F.; Lafferty, J.D.; Mercer, R.L.; Roossin, P.S. A statistical approach to machine translation. Computational Linguistics 1990, 16, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, A.L.; Pietra, V.J.D.; Pietra, S.A.D. A maximum entropy approach to natural language processing. Computational Linguistics 1996, 22, 39–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O.; Le, Q.V. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems - Volume 2, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; NIPS’14, pp. 3104–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; Dean, J. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. 2013, 1301.3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; NIPS’17, pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; NIPS ’20, pp. 1877–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinatra, R.; Deville, P.; Szell, M.; Wang, D.; Barabási, A.L. A century of physics. Nature Physics 2015, 11, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipf, G.K. Selected Studies of the Principle of Relative Frequency in Language; Harvard University Press, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancho, R.F.i.; Solé, R.V. The small world of human language. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 2001, 268, 2261–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemurro, M.A. Beyond the Zipf–Mandelbrot law in quantitative linguistics. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2001, 300, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E. Power laws, Pareto distributions and Zipf’s law. Contemporary Physics 2005, 46, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M. Rank clocks. Nature 2006, 444, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, S.K.; Bernhardsson, S.; Minnhagen, P. Zipf’s law unzipped. New Journal of Physics 2011, 13, 043004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Li, W.; Cai, X.; Bulou, A.; Wang, Q.A. Universal scaling in sports ranking. New Journal of Physics 2012, 14, 093038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumm, N.; Ghoshal, G.; Forró, Z.; Schich, M.; Bianconi, G.; Bouchaud, J.P.; Barabási, A.L. Dynamics of ranking processes in complex systems. Physical Review Letters 2012, 109, 128701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font-Clos, F.; Boleda, G.; Corral, A. A scaling law beyond Zipf’s law and its relation to Heaps’ law. New Journal of Physics 2013, 15, 093033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.M.A. The Origins of Scaling in Cities. Science 2013, 340, 1438–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, G. Scale: The Universal Laws of Life, Growth, and Death in Organisms, Cities, and Companies; Penguin Books: USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Callon, M.; Courtial, J.P.; Turner, W.A.; Bauin, S. From translations to problematic networks: An introduction to co-word analysis. Social Science Information 1983, 22, 191–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.C.; Tang, K.Y.; Lin, S.S.; Changlai, M.L.; Hsu, Y.S. A Co-word Analysis of Selected Science Education Literature: Identifying Research Trends of Scaffolding in Two Decades (2000–2019). Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 844425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arseniev-Koehler, A. Theoretical foundations and limits of word embeddings: What types of meaning can they capture? Sociological Methods & Research 2024, 53, 1753–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.B.; Shen, Y.K.; Aiden, A.P.; Veres, A.; Gray, M.K.; Team, T.G.B.; Pickett, J.P.; Hoiberg, D.; Clancy, D.; Norvig, P.; et al. Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books. Science 2011, 331, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perc, M. Evolution of the most common English words and phrases over the centuries. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2012, 9, 3323–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.M.; Tenenbaum, J.; Havlin, S.; Stanley, H.E. Statistical laws governing fluctuations in word use from word birth to word death. Scientific Reports 2012, 2, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerbi, A.; Lampos, V.; Garnett, P.; Bentley, R.A. The Expression of Emotions in 20th Century Books. PLOS One 2013, 8, e59030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochkarev, V.; Solovyev, V.; Wichmann, S. Universals versus historical contingencies in lexical evolution. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2014, 11, 20140841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.A.; Colman, E.; Sánchez, S.; Sánchez-Puig, F.; Pineda, C.; Iñiguez, G.; Cocho, G.; Flores, J.; Gershenson, C. Rank Dynamics of Word Usage at Multiple Scales. Frontiers in Physics 2018, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perc, M. Self-organization of progress across the century of physics. Scientific Reports 2013, 3, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocho, G.; Flores, J.; Gershenson, C.; Pineda, C.; Sánchez, S. Rank Diversity of Languages: Generic Behavior in Computational Linguistics. PLOS One 2015, 10, e0121898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.A.; Sánchez, S.; Flores, J.; Pineda, C.; Gershenson, C.; Cocho, G.; Zizumbo, J.; Rodríguez, R.F.; Iñiguez, G. Generic temporal features of performance rankings in sports and games. EPJ Data Science 2016, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, S.; Cocho, G.; Flores, J.; Gershenson, C.; Iñiguez, G.; Pineda, C. Trajectory Stability in the Traveling Salesman Problem. Complexity 2018, 2018, 2826082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Puig, F.; Lozano-Aranda, R.; Pérez-Méndez, D.; Colman, E.; Morales-Guzmán, A.J.; Rivera Torres, P.J.; Pineda, C.; Gershenson, C. Language Statistics at Different Spatial, Temporal, and Grammatical Scales. Entropy 2024, 26, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balucha, A. Stop-Words. 2011. Available online: https://code.google.com/archive/p/stop-words.

- França, U.; Sayama, H.; McSwiggen, C.; Daneshvar, R.; Bar-Yam, Y. Visualizing the “heartbeat” of a city with tweets. Complexity 2015, 21, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauset, A.; Shalizi, C.R.; Newman, M.E. Power-law distributions in empirical data. SIAM Review 2009, 51, 661–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.A.; Flores, J.; Gershenson, C.; Pineda, C. Statistical Properties of Rankings in Sports and Games. Advances in Complex Systems 2021, 24, 2150007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iñiguez, G.; Pineda, C.; Gershenson, C.; Barabási, A.L. Dynamics of ranking. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, W.; Moffat, A.; Zobel, J. A similarity measure for indefinite rankings. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2010, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, F.; Dewaele, J.M. Variation in the contextuality of language: An empirical measure. Foundations of science 2002, 7, 293–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIT. Pantheon World. 2013. Available online: https://pantheon.world.

- Yu, A.Z.; Ronen, S.; Hu, K.; Lu, T.; Hidalgo, C.A. Pantheon 1.0, a manually verified dataset of globally famous biographies. Scientific Data 2016, 3, 150075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 |

Function words, commonly known as stop words, carry little lexical meaning and primarily serve grammatical functions (e.g., prepositions, pronouns, auxiliary verbs, conjunctions, and articles). In contrast, content words such as nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs convey substantive meaning. |

Figure 1.

Word frequency per journal for N-grams with to . The observed frequency distributions follow the Zipf’s law for all considered cases. Deviations for 5-grams and 6-grams sequences in the PRX dataset are discussed in the main text. The data is normalized to ensure a similar number of data points per journal.

Figure 1.

Word frequency per journal for N-grams with to . The observed frequency distributions follow the Zipf’s law for all considered cases. Deviations for 5-grams and 6-grams sequences in the PRX dataset are discussed in the main text. The data is normalized to ensure a similar number of data points per journal.

Figure 2.

Rank diversity for N-grams with to in a time interval of 1 month. The curves exhibit the characteristic sigmoid shape. As the number of grams increased, the curves degenerate due to the rapid growth in rank diversity. Data is normalized to maintain a comparable number of data points per journal.

Figure 2.

Rank diversity for N-grams with to in a time interval of 1 month. The curves exhibit the characteristic sigmoid shape. As the number of grams increased, the curves degenerate due to the rapid growth in rank diversity. Data is normalized to maintain a comparable number of data points per journal.

Figure 3.

(a) RBO distance between the top 200 content words. (b) RBO distance between the top 200 words from the complete dataset. The RBO similarity values are visibly higher in (b) because the complete dataset includes common function words that are shared by all journals. Plot (a), which filters these function words out, reveals the lower similarity based only on specialized terminology. Since these function words are common to all journals, their inclusion increases the total percentage of shared words, which in turn results in higher RBO similarity scores.

Figure 3.

(a) RBO distance between the top 200 content words. (b) RBO distance between the top 200 words from the complete dataset. The RBO similarity values are visibly higher in (b) because the complete dataset includes common function words that are shared by all journals. Plot (a), which filters these function words out, reveals the lower similarity based only on specialized terminology. Since these function words are common to all journals, their inclusion increases the total percentage of shared words, which in turn results in higher RBO similarity scores.

Figure 4.

This scatter plot evaluates the stability of the similarity measure by comparing the RBO similarity for journal pairs calculated using their top 100 content words (x-axis) versus their top 1000 content words (y-axis). A single point represents one journal pair. A linear trend emerges, indicating that journals with given similarity in their most frequent 100 content words also exhibit a similar similarity when considering their top 1000 content words. Notably, all similarity values for 1-grams (single words) exceed . This high baseline similarity for individual words suggests a consistent core vocabulary across these academic publications, even as the depth of analysis increases.

Figure 4.

This scatter plot evaluates the stability of the similarity measure by comparing the RBO similarity for journal pairs calculated using their top 100 content words (x-axis) versus their top 1000 content words (y-axis). A single point represents one journal pair. A linear trend emerges, indicating that journals with given similarity in their most frequent 100 content words also exhibit a similar similarity when considering their top 1000 content words. Notably, all similarity values for 1-grams (single words) exceed . This high baseline similarity for individual words suggests a consistent core vocabulary across these academic publications, even as the depth of analysis increases.

Figure 5.

The figure shows how RBO similarity for PRL changes as we consider an increasing number of top-ranked words (). As increases, the RBO similarity stabilizes, indicating that the initial highly-ranked items mainly define the core similarity between the journals. The words at the top 100 of the ranked lists are what mostly define their similarity. The items further down the list have less influence on the overall similarity score.

Figure 5.

The figure shows how RBO similarity for PRL changes as we consider an increasing number of top-ranked words (). As increases, the RBO similarity stabilizes, indicating that the initial highly-ranked items mainly define the core similarity between the journals. The words at the top 100 of the ranked lists are what mostly define their similarity. The items further down the list have less influence on the overall similarity score.

Figure 6.

The importance factor, eq. (

2). as a function of a word’s rank in an article, plotted for different words with different specialization levels. The words, with data taken from

Table 4, are

states,

temperature,

magnetic, and

gauge. The plot demonstrates that the classification power of a word is determined by this specialization lifetime.

Figure 6.

The importance factor, eq. (

2). as a function of a word’s rank in an article, plotted for different words with different specialization levels. The words, with data taken from

Table 4, are

states,

temperature,

magnetic, and

gauge. The plot demonstrates that the classification power of a word is determined by this specialization lifetime.

Figure 7.

Distribution of correctly classified and misclassified articles for a sample of 500 articles per journal, using a specialization factor of 5. Numbers on the diagonal show the articles correctly classified. The analysis is shown for classifications using (a) 100 words, (b) 1,000 words, and (c) 10,000 words.

Figure 7.

Distribution of correctly classified and misclassified articles for a sample of 500 articles per journal, using a specialization factor of 5. Numbers on the diagonal show the articles correctly classified. The analysis is shown for classifications using (a) 100 words, (b) 1,000 words, and (c) 10,000 words.

Figure 8.

Classification accuracy of APS articles based on the percentage of correctly classified texts. Results are shown for different numbers of content words (100, 1,000, and 10,000) and specialization factor thresholds (5, 2, and 1) for the top-ranked words.

Figure 8.

Classification accuracy of APS articles based on the percentage of correctly classified texts. Results are shown for different numbers of content words (100, 1,000, and 10,000) and specialization factor thresholds (5, 2, and 1) for the top-ranked words.

Figure 9.

Relation between rankings of top 200 physicists. Pearson Correlation near 0, showing low relation between PRB journal and Pantheon (in blue). Pearson Correlation near 1, showing high relation between PRL and RMP journals (in red).

Figure 9.

Relation between rankings of top 200 physicists. Pearson Correlation near 0, showing low relation between PRB journal and Pantheon (in blue). Pearson Correlation near 1, showing high relation between PRL and RMP journals (in red).

Figure 10.

Pearson correlation between Patheon and APS journals according to their top 200 physicists.

Figure 10.

Pearson correlation between Patheon and APS journals according to their top 200 physicists.

Table 1.

Summary of the eight journal selected for this study from the American Physical Society (APS).

Table 1.

Summary of the eight journal selected for this study from the American Physical Society (APS).

| Journal |

Abbreviation |

Scope |

| Phys. Rev. A. |

PRA |

Atomic, molecular, |

| |

|

optical physics and |

| |

|

quantum information |

| Phys. Rev. B. |

PRB |

Condensed matter and |

| |

|

material physics |

| Phys. Rev. C. |

PRC |

Nuclear physics |

| Phys. Rev. D. |

PRD |

Particles, fields, |

| |

|

gravitation and cosmology |

| Phys. Rev. E. |

PRE |

Statistical, non-linear, |

| |

|

biological and soft |

| |

|

matter physics |

| Phys. Rev. X. |

PRX |

Broad subject |

| |

|

coverage encouraging |

| |

|

communication across |

| |

|

related fields |

| Phys. Rev. Lett. |

PRL |

Fundamental research |

| |

|

on all topics |

| |

|

related to all |

| |

|

fields of physics |

| Rev. Mod. Phys. |

RMP |

The full range |

| |

|

of applied, fundamental, |

| |

|

and interdisciplinary |

| |

|

physics research topics |

Table 2.

Information of the dataset collected for this research. Columns show the time period, the total number of articles used per journal and the total number of content words.

Table 2.

Information of the dataset collected for this research. Columns show the time period, the total number of articles used per journal and the total number of content words.

| Journal |

Years |

Articles |

Content Words |

Total Words |

| PRA |

1970 - 2017 |

105,383 |

1,267,089 |

24,103,820 |

| PRB |

1970 - 2017 |

241,135 |

2,785,162 |

14,774,108 |

| PRC |

1970 - 2017 |

57,609 |

1,456,679 |

26,638,407 |

| PRD |

1970 - 2017 |

110,288 |

837,719 |

37,122,795 |

| PRE |

1993 - 2017 |

86,743 |

2,025,377 |

29,616,401 |

| PRL |

1959 - 2017 |

123,217 |

1,841,870 |

18,548,599 |

| PRX |

2012 - 2017 |

1,153 |

1,848,094 |

29,704,075 |

| RMP |

1930 - 2017 |

4,593 |

266,052 |

1,256,168 |

Table 3.

top 20 content words from the specialized journals. Words in bold are common across all five journals, while italicized words are unique to a single journal within this list.

Table 3.

top 20 content words from the specialized journals. Words in bold are common across all five journals, while italicized words are unique to a single journal within this list.

| Rank |

PRA |

PRB |

PRC |

PRD |

PRE |

| 1 |

state |

energy |

energy |

mass |

model |

| 2 |

states |

temperature |

mev |

energy |

system |

| 3 |

energy |

state |

data |

model |

function |

| 4 |

quantum |

magnetic |

state |

field |

case |

| 5 |

field |

field |

states |

case |

results |

| 6 |

function |

states |

model |

order |

energy |

| 7 |

case |

results |

cross |

function |

phase |

| 8 |

system |

function |

results |

theory |

number |

| 9 |

results |

model |

nuclear |

terms |

different |

| 10 |

number |

phase |

values |

results |

values |

| 11 |

phase |

surface |

energies |

data |

equation |

| 12 |

wave |

structure |

function |

form |

order |

| 13 |

values |

spin |

calculations |

gauge |

value |

| 14 |

laser |

shown |

experimental |

gev |

density |

| 15 |

electron |

case |

nuclei |

value |

shown |

| 16 |

potential |

different |

potential |

values |

distribution |

| 17 |

shown |

order |

obtained |

equation |

field |

| 18 |

different |

system |

reaction |

large |

state |

| 19 |

atoms |

values |

scattering |

same |

same |

| 20 |

density |

density |

neutron |

term |

dynamics |

Table 4.

Compilation of unique words identified within each journal’s corpus, detailing their lifetime ranking. For each unique word, it shows the rank at which it first appears and the number of rank positions where it states unique. These metrics reflect the thematic scope and lexical distinctiveness of each journal.

Table 4.

Compilation of unique words identified within each journal’s corpus, detailing their lifetime ranking. For each unique word, it shows the rank at which it first appears and the number of rank positions where it states unique. These metrics reflect the thematic scope and lexical distinctiveness of each journal.

| PRA |

PRB |

PRC |

PRD |

PRE |

| state |

1-2 |

temperature |

2-22 |

mev |

2-130 |

mass |

1-23 |

model |

1-2 |

| states |

2-4 |

magnetic |

4-121 |

data |

3-10 |

order |

6-11 |

system |

2-7 |

| quantum |

4-44 |

surface |

11-31 |

cross |

7-26 |

theory |

8-32 |

function |

3-5 |

| wave |

12-42 |

structure |

12-51 |

nuclear |

9-409 |

terms |

9-31 |

results |

5-6 |

| laser |

14-295 |

spin |

13-55 |

energies |

11-71 |

form |

12-33 |

phase |

7-9 |

| electron |

15-22 |

transition |

22-29 |

calculations |

13-45 |

gauge |

13-951 |

number |

8-9 |

| atoms |

19-39 |

band |

26-81 |

experimental |

14-30 |

gev |

14-102 |

different |

9-15 |

| atomic |

29-151 |

due |

27-38 |

nuclei |

15-1525 |

large |

18-26 |

equation |

11-16 |

| frequency |

30-80 |

observed |

28-39 |

obtained |

17-21 |

term |

20-69 |

value |

13-14 |

| matrix |

35-53 |

lattice |

30-75 |

reaction |

18-576 |

limit |

21-49 |

density |

14-19 |

| pulse |

45-384 |

dependence |

32-69 |

scattering |

19-34 |

decay |

22-27 |

distribution |

16-41 |

| corresponding |

46-55 |

sample |

34-311 |

neutron |

20-638 |

quark |

23-200 |

dynamics |

20-105 |

| beam |

47-72 |

effect |

42-64 |

kev |

21-678 |

scalar |

26-648 |

small |

21-32 |

| atom |

49-160 |

found |

44-58 |

interaction |

25-27 |

equations |

27-36 |

particles |

24-80 |

| approximation |

51-99 |

shows |

51-60 |

momentum |

26-43 |

parameters |

28-38 |

systems |

25-62 |

| optical |

55-135 |

show |

53-56 |

calculated |

27-38 |

scale |

29-120 |

behavior |

26-48 |

| set |

56-78 |

along |

54-117 |

present |

28-37 |

fields |

32-139 |

point |

28-51 |

| method |

57-62 |

spectra |

55-71 |

angular |

35-152 |

space |

36-92 |

velocity |

29-157 |

| hamiltonian |

59-115 |

properties |

56-95 |

level |

36-101 |

functions |

37-39 |

parameter |

33-37 |

| ionization |

62-1423 |

electrons |

58-119 |

excitation |

37-89 |

models |

40-96 |

particle |

35-65 |

Table 5.

Table of common words. The range when they became common in the scientific journals, and their range in general English. It shows both key physics concepts such as "energy" and less significant words such as "same", reflecting the journals’ thematic scope and linguistic characteristics.

Table 5.

Table of common words. The range when they became common in the scientific journals, and their range in general English. It shows both key physics concepts such as "energy" and less significant words such as "same", reflecting the journals’ thematic scope and linguistic characteristics.

| Word |

Common Rank |

English Rank |

| energy |

6 |

457 |

| results |

10 |

361 |

| function |

12 |

519 |

| values |

19 |

579 |

| model |

24 |

317 |

| value |

24 |

221 |

| state |

31 |

62 |

| same |

32 |

45 |

| different |

34 |

84 |

| obtained |

34 |

|

| shown |

35 |

430 |

| number |

36 |

95 |

| case |

38 |

83 |

| potential |

38 |

729 |

| density |

41 |

|

| data |

43 |

184 |

| large |

48 |

142 |

| parameters |

52 |

|

| order |

55 |

108 |

| terms |

64 |

369 |

Table 6.

Variation in the importance factor based on the rank of the term temperature within a given hypothetical article t, where the rank is .

Table 6.

Variation in the importance factor based on the rank of the term temperature within a given hypothetical article t, where the rank is .

|

|

| 1 |

1.2890 |

| 2 |

1.000 |

| 10 |

0.3288 |

| 20 |

0.0397 |

| 400 |

-1.2096 |

| 500 |

-1.3026 |

Table 7.

The 10 most famous physicist and their relative ranking within each APS journal. Cells marked with the symbol “-” means that there are no occurrences in the journal.

Table 7.

The 10 most famous physicist and their relative ranking within each APS journal. Cells marked with the symbol “-” means that there are no occurrences in the journal.

| Physicist |

Pantheon |

PRA |

PRB |

PRC |

PRD |

PRE |

PRL |

PRX |

RMP |

| Curie |

3 |

72 |

11 |

84 |

53 |

51 |

27 |

29 |

38 |

| Einstein |

2 |

12 |

26 |

41 |

2 |

13 |

11 |

12 |

8 |

| Faraday |

6 |

35 |

31 |

38 |

60 |

26 |

33 |

31 |

41 |

| Hawking |

5 |

92 |

150 |

148 |

11 |

130 |

60 |

76 |

59 |

| Newton |

1 |

48 |

75 |

37 |

25 |

31 |

59 |

53 |

47 |

| Orsted |

9 |

182 |

186 |

- |

180 |

- |

187 |

- |

- |

| Planck |

7 |

25 |

35 |

50 |

7 |

5 |

15 |

23 |

25 |

| Röntgen |

4 |

153 |

184 |

- |

179 |

- |

183 |

- |

181 |

| Rutherford |

10 |

70 |

77 |

29 |

57 |

94 |

56 |

123 |

77 |

| Volta |

8 |

140 |

134 |

160 |

158 |

146 |

160 |

148 |

173 |

Table 8.

Famous top 10 physicist within each APS journal. This is a relative ranking, determined by the frequency of surnames mentioned within each specific journal’s corpus. While researchers can recognize, to a greater or lesser extent, the influential figures across all of physics, this table highlights the specific set of foundational figures who are most prominent and frequently mention within each distinct community.

Table 8.

Famous top 10 physicist within each APS journal. This is a relative ranking, determined by the frequency of surnames mentioned within each specific journal’s corpus. While researchers can recognize, to a greater or lesser extent, the influential figures across all of physics, this table highlights the specific set of foundational figures who are most prominent and frequently mention within each distinct community.

| Rank |

PRA |

PRB |

PRC |

PRD |

PRE |

PRL |

PRX |

RMP |

| 1 |

Coulomb |

Fermi |

Coulomb |

Higgs |

Boltzmann |

Fermi |

Fermi |

Fermi |

| 2 |

Bose |

Coulomb |

Fermi |

Einstein |

Chen |

Coulomb |

Dirac |

Coulomb |

| 3 |

Fermi |

Raman |

Pauli |

Dirac |

Landau |

Lee |

Chen |

Lee |

| 4 |

Rabi |

Landau |

Dirac |

Lorentz |

Langevin |

Raman |

Landau |

Landau |

| 5 |

Bloch |

Lee |

Lee |

Yukawa |

Plank |

Landau |

Coulomb |

Chen |

| 6 |

Raman |

Chen |

Born |

Wilson |

Lee |

Chen |

Bose |

Dirac |

| 7 |

Stark |

Dirac |

Wigner |

Planck |

Rayleigh |

Dirac |

Lee |

Anderson |

| 8 |

Born |

Anderson |

Chen |

Feynman |

Coulomb |

Anderson |

Raman |

Einstein |

| 9 |

Wigner |

Heisenberg |

Landau |

Schwarzschild |

Maxwell |

Bose |

Bloch |

Higgs |

| 10 |

Dirac |

Bloch |

Gamow |

Fermi |

Debye |

Higgs |

Pauli |

Smith |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).