Submitted:

13 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

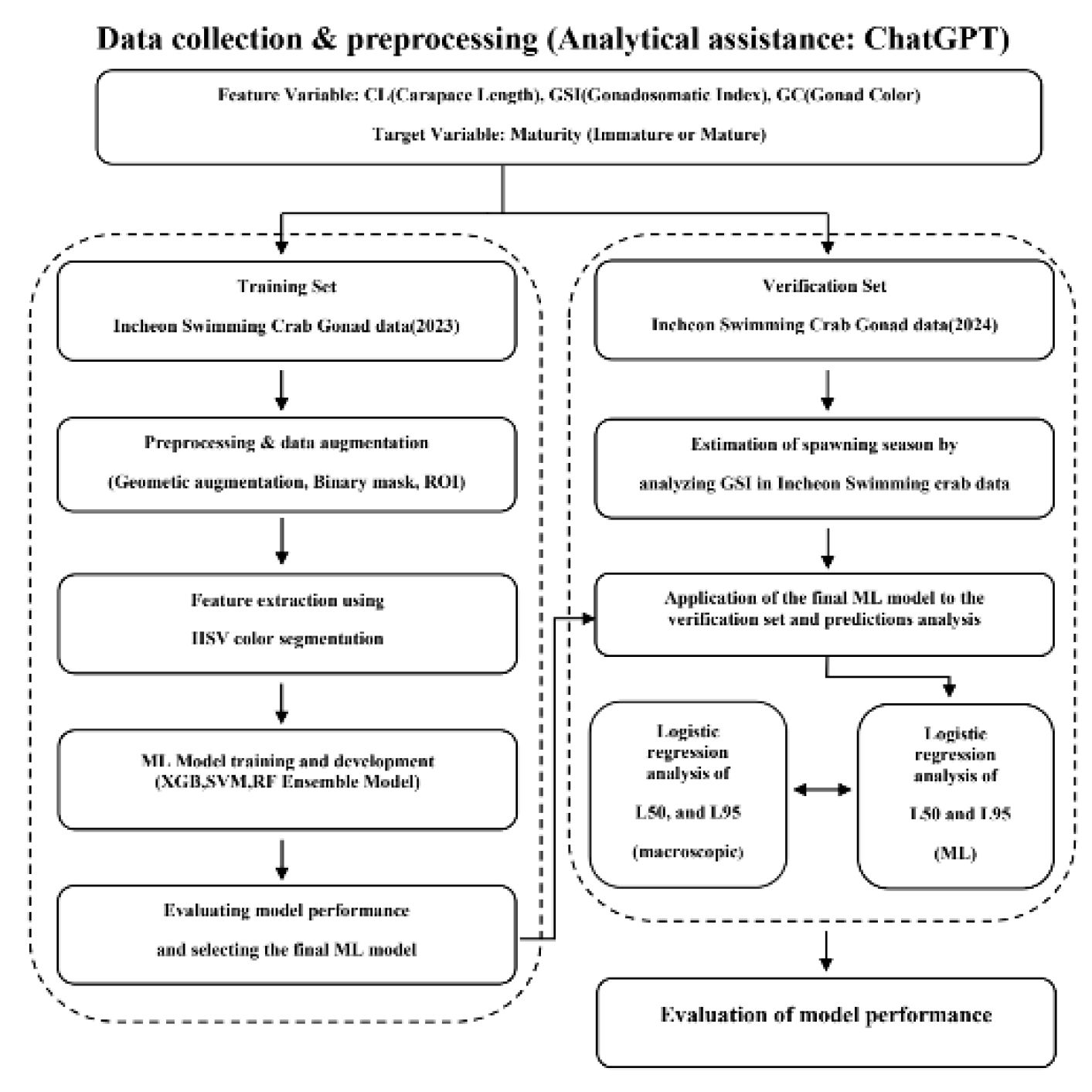

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Configuration

2.2. Data Analysis Tools

2.3. Data Pretreatment and Feature Extraction

2.4. Machine Learning Model Training and Evaluation

2.5. GSI (Gonadosomatic Index)

2.6. Logistic Regression for L₅₀ Estimating

3. Results

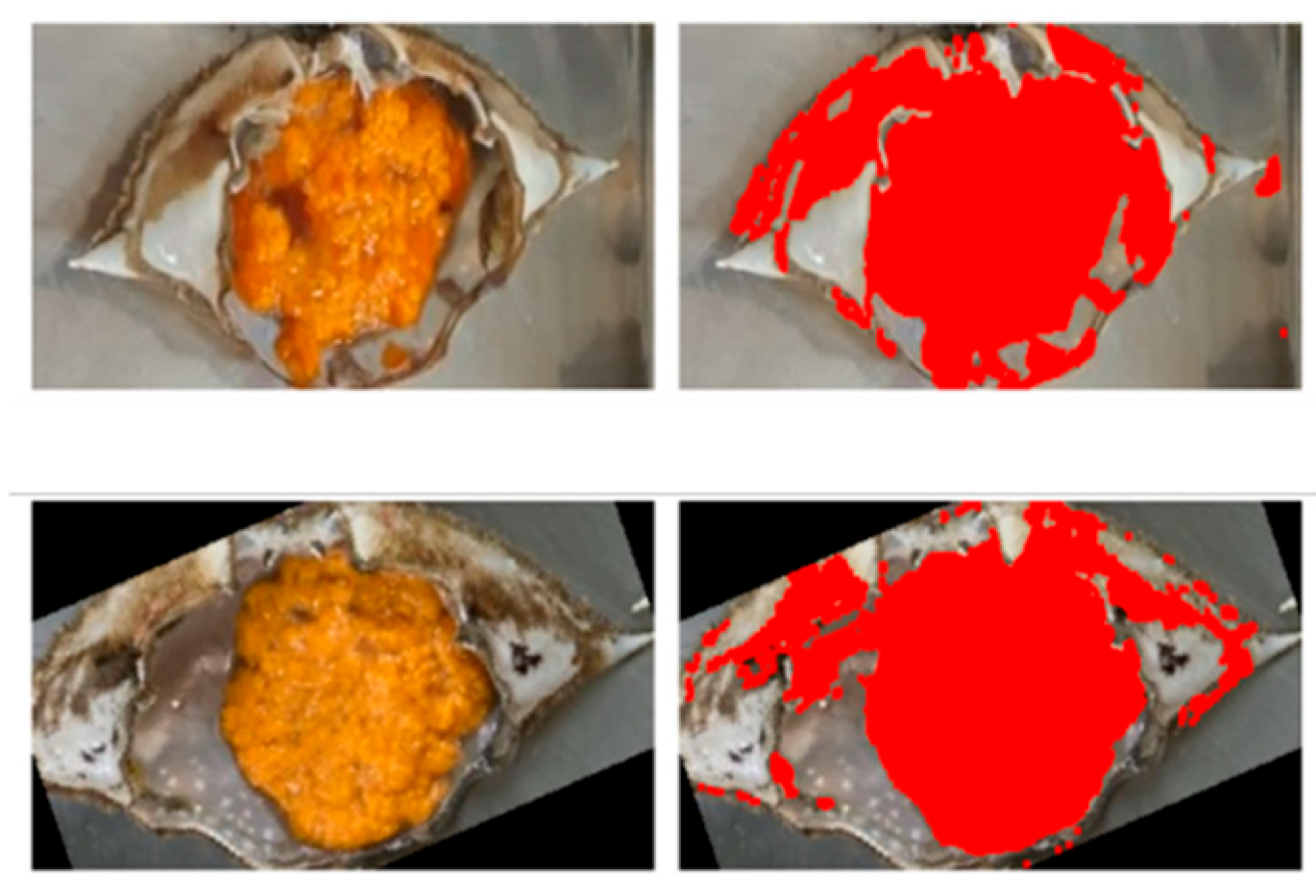

3.1. Data Pretreatment and Feature Extraction Results

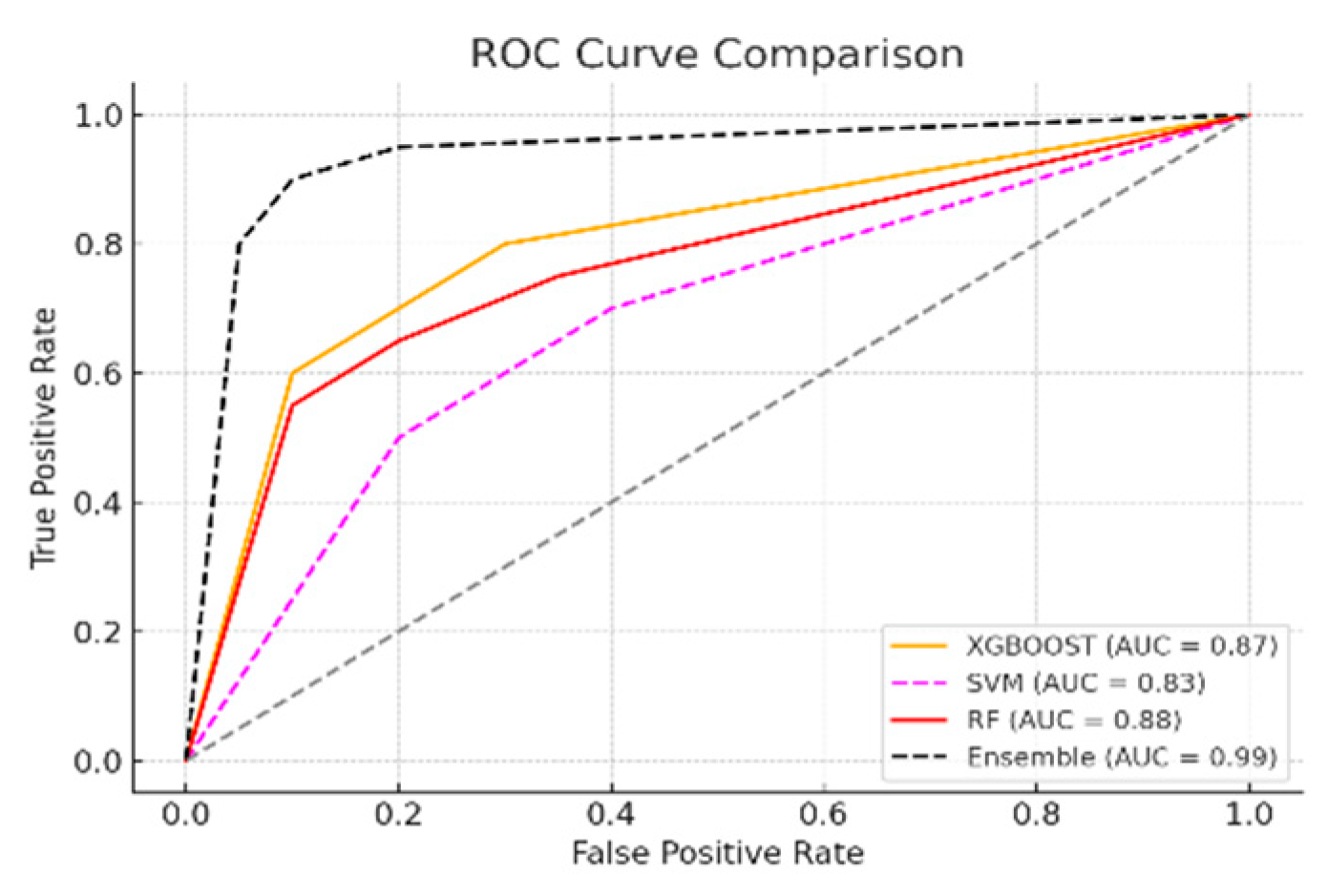

3.2. Machine Learning Model Training and Evaluation Results

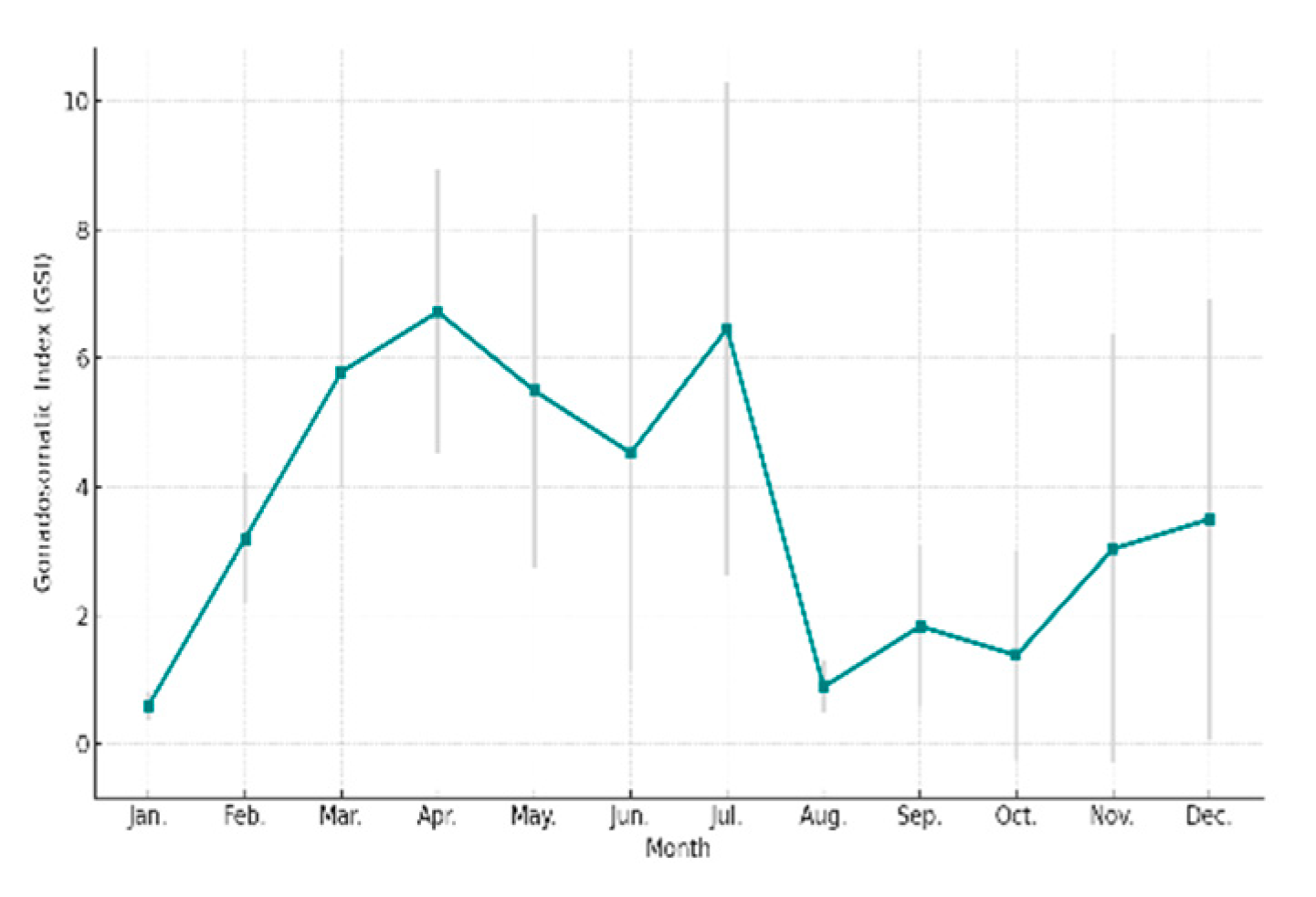

3.3. GSI Estimation Results

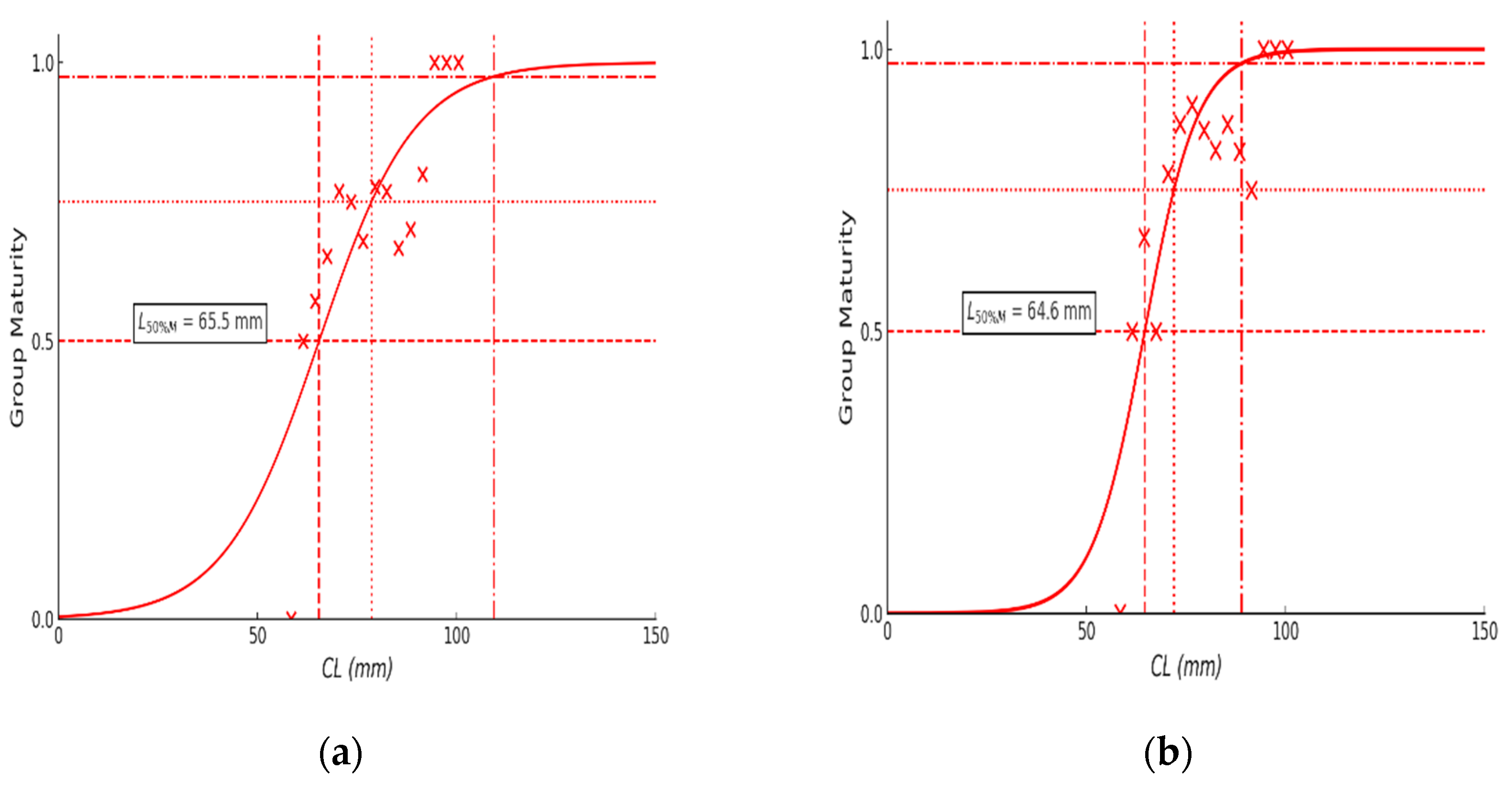

3.4. Estimating Length at First Maturity Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kwon, H. K.; Kwon, N.; Cho, Y. K.; Hwang, J.; Choi, Y.; Lim, W. A.; Kim, G. Difference in nutritional status and food sources for hard-and soft-shell crabs (Portunus trituberculatus) using amino acids and isotopic tracers. Scientific Reports 2025, 15(1), 15694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, T. Studies on the crabs of Japan. IV. Brachygnatha, Brachyrhyncha; Tokyo, 1939; p. 741 pp. + plates. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, HS. Illustrated Encyclopedia of Fauna and of Korea; 1973; Volume 14, p. 1~289. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, A; Yang, S. Crabs of the China Seas; China Ocean Press Bijing, 1991; p. 682. [Google Scholar]

- Pyen, CK. Propagation of the blue crab, Portunus trituberculatus(Miers). Bull. Korean Fish. Soc. 1970, 3(3), 187~198. [Google Scholar]

- KOSIS(Korean Statistical Information Service). Fishery Production Survey. 2025. Available online: http://kosis.kr.

- Kang, JC; Song, JC; Chin, P. Combined Effects of hypoxia and hydrogen sulfide on survival, feeding activity and metabolic rate of blue crab, Portunus trituberculatus. Journal of the Korean Fisheries Society 1995, 28(5), 549~556. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y. K.; Choi, S. M.; Choi, S. D.; Yoon, H. S. A Characteristics of Biological Resources of Portunus trituberculatus (Miers, 1876) around the Chilsan Inland Younggwang, Korea. Journal of the Korean Society of Marine Environment & Safety 2012, 18(2), 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KOH, Su-Jin; YOUN, Byeong-Il; LEE, Seung-Hwan; KOO, Ja-Geun; KIM, Maeng-Jin. Distribution and Occurrence of Swimming Crab, Portunus trituberculatus Larvae in the Western water Coast of Korea. THE JOURNAL OF FISHERIES AND MARINE SCIENCES EDUCATION 2022, 34(5), 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, SB; Yoo, BS; Lee, KS. Studies on the CNBr - peptide of Portunus trituberculatus hemocyanin. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Reports 1989, 22(2), 113~117. [Google Scholar]

- Yeon, IJ; Song, MY; Shon, MH; Hwang, HJ.; Im, YJ. Possible new management measures for stock rebuilding of blue crab, Portunus trituberculatus (Miers), in western korean waters. proceedings of Korean Applied Industrial Sciences 2010, 5(2), 35. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, JM. Genetic differences and variations in freshwater crab (Eriocheir sinensis) and swimming crab (Portunus trituberculatus). development and Reproduction 2006, 10(1), 19~32. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, H. C.; Jang, I. K.; Cho, Y. R.; Kim, J. S.; Kim, B. R. Gonad maturation and spawning of the bluecrab, Portunus trituberculatus (Miers, 1876) from the West Sea of Korea. Korean journal of Fisheries and aquatic sciences 2009, 42(1), 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trippel, E. A.; Harvey, H. H. Comparison of methods used to estimate age and length of fishes at sexual maturity using populations of white sucker (Catostomus commersoni). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 1991, 48(8), 1446–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trippel, E. A. Age at maturity as a stress indicator in fisheries. Bioscience 1995, 45(11), 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowerre-Barbieri, S. K.; Ganias, K.; Saborido-Rey, F.; Murua, H.; Hunter, J. R. Reproductive timing in marine fishes: Variability, temporal scales, and methods. Mar. Coast. Fish. 2011b, 3, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, G. Methods of assessing ovarian development in fishes: a review. Marine and freshwater research 1990, 41(2), 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkiewicz, J.; Tybjerg, L.; Jespersen, Å. Micro-and macroscopic characteristics to stage gonadal maturation of female Baltic cod. Journal of fish biology 2003, 62(2), 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saborido-Rey, F.; Junquera, S. Histological assessment of variations in sexual maturity of cod (Gadus morhua L.) at the Flemish Cap (north-west Atlantic). ICES Journal of Marine Science 1998, 55(3), 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, P. H.; Head, M. A.; Keller, A. A. Maturity and growth of darkblotched rockfish, Sebastes crameri, along the US west coast. Environmental Biology of Fishes 2015, 98, 2353–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, M. A.; Cope, J. M.; Wulfing, S. H. Applying a flexible spline model to estimate functional maturity and spatio-temporal variability in aurora rockfish (Sebastes aurora). Environmental Biology of Fishes 2020, 103, 1199–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladju, J.; Kamalam, B. S.; Kanagaraj, A. Applications of data mining and machine learning framework in aquaculture and fisheries: A review. Smart Agricultural Technology 2022, 2, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubbens, P.; Brodie, S.; Cordier, T.; Destro Barcellos, D.; Devos, P.; Fernandes-Salvador, J. A.; Irisson, J. O. Machine learning in marine ecology: an overview of techniques and applications. ICES Journal of Marine Science 2023, 80(7), 1829–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Yoon, S. C. Enhancing Length at First Maturity Estimation Using Machine Learning for Fisheries Resource Management: A Case Study on Small Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) in South Korea. Fishes (MDPI AG) 2024, 9(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellez, D.; Litjens, G.; Bándi, P.; Bulten, W.; Bokhorst, J. M.; Ciompi, F.; Van Der Laak, J. Quantifying the effects of data augmentation and stain color normalization in convolutional neural networks for computational pathology. Medical image analysis 2019, 58, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, F.; Avila, S.; Valle, E. Solo or ensemble? choosing a cnn architecture for melanoma classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 2019; pp. 0–0. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, A.; Wiff, R.; Donovan, C. R.; Gálvez, P. Applying machine learning to predict reproductive condition in fish. Ecological Informatics 2024, 80, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, J. A.; McNeil, B. J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982, 143(1), 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allouche, O.; Tsoar, A.; Kadmon, R. Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: prevalence, kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). Journal of applied ecology 2006, 43(6), 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. T.; Tibshirani, R. J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap; Chapman & HallHall. CRC Monographs on Statistics & Applied Probability: New York, NY, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T. M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. Journal of big data 2019, 6(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoh, W. H.; Pang, Y. H.; Teoh, A. B. J.; Ooi, S. Y. In-air hand gesture signature using transfer learning and its forgery attack. Applied Soft Computing 2021, 113, 108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaluddin, B. A.; Chao, C. T.; Chiou, J. S. Investigating Effective Geometric Transformation for Image Augmentation to Improve Static Hand Gestures with a Pre-Trained Convolutional Neural Network. Mathematics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C. J.; Sun, D. W. Comparison of three methods for classification of pizza topping using different colour space transformations. Journal of food engineering 2005, 68(3), 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves-González, J. M.; Vega-Rodríguez, M. A.; Gómez-Pulido, J. A.; Sánchez-Pérez, J. M. Detecting skin in face recognition systems: A colour spaces study. Digital signal processing 2010, 20(3), 806–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ruiz, G.; Gómez-Gil, J.; Navas-Gracia, L. M. Testing different color spaces based on hue for the environmentally adaptive segmentation algorithm (EASA). Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2009, 68(1), 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudana, O.; Witarsyah, D.; Putra, A.; Raharja, S. Mobile application for identification of coffee fruit maturity using digital image processing. International Journal on Advanced Science, Engineering and Information Technology 2020, 10(3), 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, K. K.; Rahman, A.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Syduzzaman, M.; Uddin, M. Z.; Rahman, M. M.; Oliver, M. M. H. Classification of starfruit maturity using smartphone-image and multivariate analysis. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, N.; Kaushik, N.; Kumar, D.; Raj, C.; Ali, A. Mortality prediction of COVID-19 patients using soft voting classifier. International Journal of Cognitive Computing in Engineering 2022, 3, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, R.; Shanto, M. S. I.; Kabir, M. M.; Rahman, M. S.; Mridha, M. F. Heart disease prediction and analysis using ensemble architecture. 2022 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications (DASA), 2022, March; IEEE; pp. 1386–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, N.; Ara, F.; Neloy, M. A. I.; Barua, V.; Hossain, M. S.; Andersson, K. A comparative analysis of the ensemble method for liver disease prediction. 2019 2nd international conference on innovation in engineering and technology (ICIET), 2019, December; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqlain, M.; Jargalsaikhan, B.; Lee, J. Y. A voting ensemble classifier for wafer map defect patterns identification in semiconductor manufacturing. IEEE Transactions on Semiconductor Manufacturing 2019, 32(2), 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, P.; Uddin, S.; Hajati, F.; Moni, M. A. Ensemble learning for disease prediction: A review. In Healthcare; MDPI, June 2023; Vol. 11, No. 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhillar, I.; Singh, A. An improved soft voting-based machine learning technique to detect breast cancer utilizing effective feature selection and SMOTE-ENN class balancing. Discover Artificial Intelligence 2025, 5(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. H. Ensemble methods: foundations and algorithms; CRC press, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yeon, I. J. Fishery biology of the blue crab, Portunus trituberculatus (Miers), in the West Sea of Korea and the East China Sea. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Pukyong National University. Korea, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, C. W. Population biology of the swimming crab Portunus trituberculatus (Miers, 1876)(Decapoda, Brachyura) on the western coast of Korea, Yellow Sea. Crustaceana 2011, 84(10). [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, D. E.; Waddy, S. L. Interaction of temperature and photoperiod in the regulation of spawning by American lobsters (Homarus americanus). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 1989, 46(1), 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddy, S. L.; Aiken, D. E. Seasonal variation in spawning by preovigerous American lobster (Homarus americanus) in response to temperature and photoperiod manipulation. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 1992, 49(6), 1114–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, H.; Ahl, J. S.; Sagi, A. The role of juvenile hormones in crustacean reproduction. American Zoologist 1993, 33(3), 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, S.; Zhang, W. Experimental evidence on the productivity effects of generative artificial intelligence. Science 2023, 381(6654), 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. ChatGPT utility in healthcare education, research, and practice: systematic review on the promising perspectives and valid concerns. In Healthcare; MDPI, March 2023; Vol. 11, No. 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dis, E. A.; Bollen, J.; Zuidema, W.; van Rooij, R.; Bocking, C. L. ChatGPT: five priorities for research. Nature. 2023. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-00288-7.

| Classification | Hue | Sat |

| Immature | 15-18 | 120-145 |

| Mature | 14-17 | 170-187 |

| Moder | Accuracy | AUC | TSS | Final score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| SVM | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.82 |

| RF | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.87 |

| Esemble | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.97 |

| Metric | Macroscopic | ML(Esemble) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate(mm) | 65.47 | 64.63 | ||

| Standard Error (SE, mm) | 2.89 | 1.73 | ||

| 95% Confidence Interval | 59.81 – 71.13 | 61.25 – 68.02 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).