1. Introduction

Leishmania spp. are intracellular protozoan parasites responsible for leishmaniases, a group of neglected tropical diseases with substantial global impact [

1,

2]. Their ability to persist within macrophages reflects a long evolutionary history of adaptation, shaped by selective pressures that refined mechanisms of immune modulation, metabolic flexibility, and vesicle-mediated communication. Extracellular vesicles released by

Leishmania (

LEVs) have emerged as central mediators of parasite–host interaction, transporting proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids capable of reprogramming macrophage signalling and inflammatory responses [

1,

3,

7].

Although the protein and RNA cargo of

LEVs has been extensively characterized, their lipid composition remains comparatively underexplored [

4,

8,

10]. Lipids are key regulators of membrane curvature, vesicle budding, cargo selection, and receptor engagement at the host–parasite interface [

3,

9]. Species-specific lipidomic signatures among

Leishmania spp. suggest that lipid diversity contributes to differences in virulence, tissue tropism, drug resistance, and immune evasion [

4,

9,

10,

11]. These molecular features reflect deeper evolutionary processes that shaped parasite survival strategies across ecological contexts.

Leishmania (L.) amazonensis, associated with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis, exhibits remarkable adaptations, including the formation of large parasitophorous vacuoles and the attenuation of macrophage microbicidal responses [

5,

12]. Understanding the lipid-based mechanisms underlying

LEV biogenesis and function in this species is therefore essential for elucidating how molecular evolution contributes to pathogenicity.

In this study, we analysed promastigotes and intracellular amastigotes of

L. (L.) amazonensis using TEM, SEM, and fluorescence microscopy. By integrating ultrastructural observations with lipid-focused literature, we propose a lipid-centered model of

LEV biogenesis and host-cell modulation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

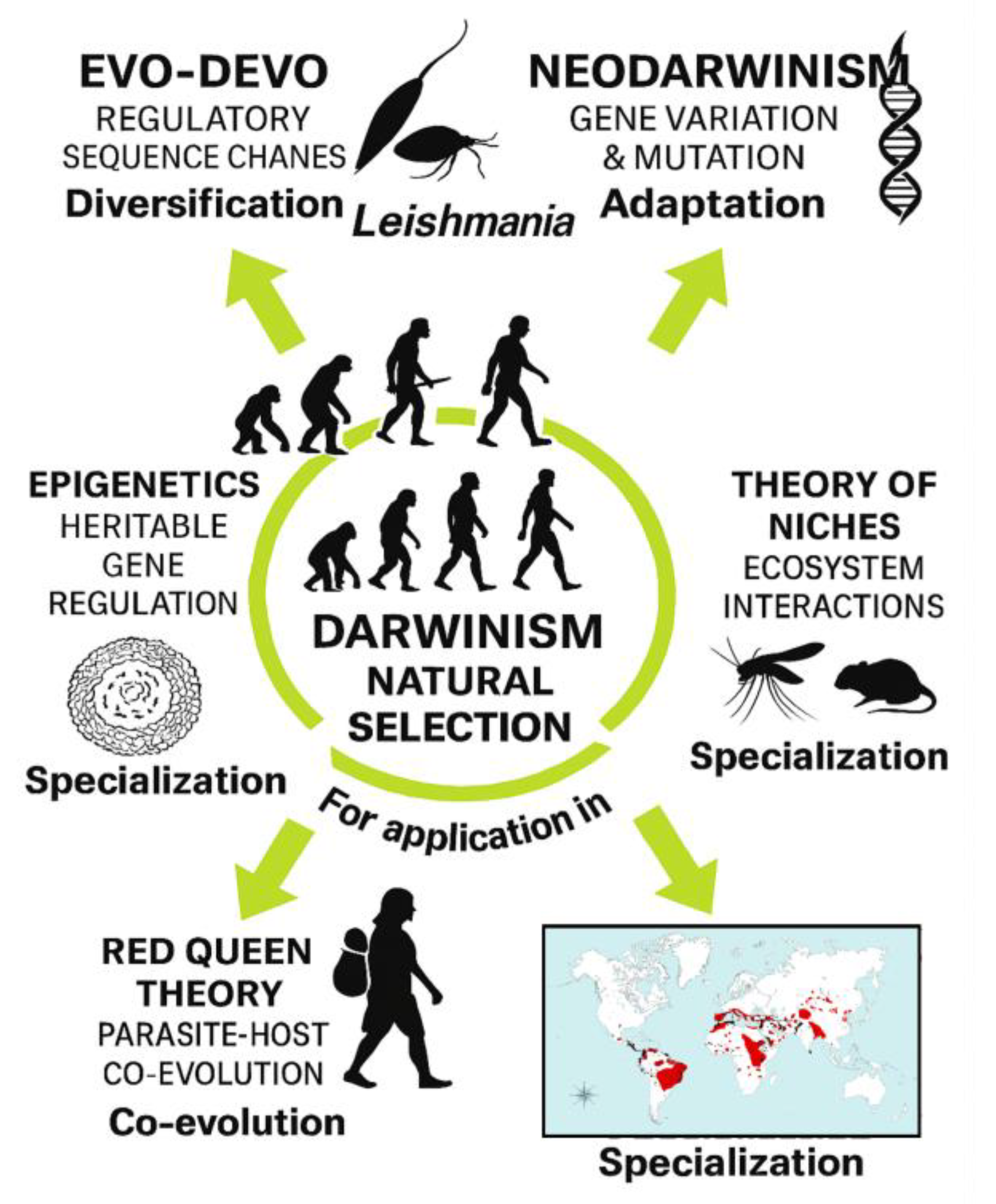

The evolutionary dynamics of lipid-mediated parasite–host communication can also be contextualized within a One Health framework, which recognizes that parasitic diseases emerge and persist through interconnected human, animal, and environmental systems [

5]. This conceptual relationship is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Parasite Culture

Promastigotes of Leishmania (L.) amazonensis (MHOM/BR/1973/M2269) were cultured in Schneider’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 µg/mL) at 26 °C, according to the protocol adopted by the laboratory. Stationary-phase promastigotes were harvested on day 7.

Promastigotes of L. (L.) amazonensis (MHOM/BR/26361) obtained from NNN medium cultures provided by the Leishmaniasis Program of the Instituto Evandro Chagas (Belém, Pará, Brazil) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and incubated at 27 °C in a Biological Oxygen Demand (B.O.D.) chamber, following the standard protocol routinely used in our laboratory. Exponential-phase (day 4) and stationary-phase (day 7) promastigotes were collected according to the experimental design. Cultures were centrifuged at 2,500 rpm for 10 min at 27 °C, and the resulting pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of RPMI. Parasite density was determined using a Neubauer counting chamber and adjusted for each experimental condition.

2.2. Animals and Peritoneal Macrophage Isolation and Culture

Peritoneal macrophages were obtained from the abdominal cavity of male BALB/c mice (Mus musculus), 6–8 weeks of age. Animals were anesthetized and euthanized in a CO₂ chamber (Insight®) in accordance with the guidelines of the National Council for the Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA). After removal of the abdominal skin and exposure of the peritoneal cavity, 5 mL of sterile DMEM was injected, and the peritoneal lavage fluid was aspirated and centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of DMEM without fetal bovine serum (FBS), according to the protocol adopted by the laboratory. Cell counts were performed using a Neubauer chamber, and the concentration was adjusted according to the experimental design.

Macrophages were seeded onto sterile glass coverslips and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere for 2 h to allow cell adhesion. After this period, the culture medium was removed, and non-adherent cells were washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2. Fresh DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS was then added, and the cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere for 24 h, following the standard protocol routinely used in our laboratory, after which the experimental assays were initiated.

2.3. Infection of Macrophages

Macrophages were infected with stationary-phase promastigotes at a 10:1 parasite-to-cell ratio for 4 h. Non-internalized parasites were removed by washing, and cultures were incubated for 24–48 h.

2.4. Light Microscopy and Giemsa Staining

2.4.1. Giemsa Staining – Promastigotes

Promastigotes of Leishmania (L.) amazonensis in the exponential growth phase were used at a concentration of 1 × 10⁶ cells/mL. After the cultivation period, cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde and allowed to adhere to poly-L-lysine–coated coverslips for 30 min. Samples were then stained with 10% Giemsa solution (diluted in phosphate buffer, pH 8.0) for 30 min. Slides were examined under an Olympus BX41 bright-field optical microscope, and images were acquired using an Axio Scope.A1 (Zeiss) microscope equipped with a Zeiss digital camera.

2.4.2. Giemsa Staining – Intracellular Amastigotes

Host-cell infection was performed using stationary-phase promastigotes of Leishmania (L.) amazonensis (day 6 of culture) at a ratio of 1:10 (one macrophage to ten parasites). After 72 h of incubation, cells were washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove non-internalized parasites and fixed either with 3% paraformaldehyde diluted in 0.1 M PHEM buffer for 30 min or with cold methanol for 10 min, according to the protocol adopted by the laboratory. Samples were subsequently stained with Giemsa® (Sigma) for 30 min at room temperature. After staining, slides were gently rinsed with distilled water, air-dried, and mounted for analysis. Intracellular amastigotes were visualized under brightfield microscopy using an Olympus BX41 microscope, and representative images were acquired with an Axio Scope.A1 (Zeiss) microscope equipped with a digital camera.

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Mouse peritoneal macrophages (10⁶ cells/mL) were cultured and subsequently infected with Leishmania (L.) amazonensis promastigotes as previously described. After 72 h of infection, cells were washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Samples were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, critical-point dried, and fractured by gently applying a small piece of adhesive tape to the dried surface to remove the upper portion of the macrophages, thereby exposing the amastigotes within the parasitophorous vacuole. The samples were then sputter-coated with gold and examined using a MIRA 3 TESCAN scanning electron microscope.

2.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Promastigotes of Leishmania (L.) amazonensis (2 × 10⁶ cells/mL) were cultured in tissue-culture flasks. After 72 h of growth, cells were fixed for 1 h in a solution containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde type II (70%), 4% paraformaldehyde, and 2.5% sucrose in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2). Following primary fixation, samples were post-fixed for 1% osmium tetroxide and 0.8% potassium ferrocyanide for 1 h. Cells were then dehydrated in a graded acetone series (50%, 70%, 90%, and three changes of 100%, 10 min each), gradually infiltrated with Epon® resin at increasing ratios (2:1, 1:1, and 1:2 acetone:Epon®), and finally placed in pure Epon® for 6 h before polymerization at 60 °C for 48 h. Resin blocks were sectioned using an ultramicrotome (Leica EM UC6), and ultrathin sections were stained with 5% uranyl acetate followed by lead citrate. Promastigotes and infected macrophages were examined using a LEO 906 E transmission electron microscope.

2.7. Bodipy Lipid Staining

Promastigotes of Leishmania (L.) amazonensis were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and allowed to adhere to poly-L-lysine–coated coverslips for 30 min. As a preparatory step for staining, cells were permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 and subsequently incubated with 50 mM ammonium chloride (NH₄Cl) for blocking. Nuclear staining was performed using ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (ThermoFisher). For lipid staining, promastigotes were incubated with BODIPY® 493/503 (1 µg/mL) for 15 min in the absence of light, washed with PBS, and mounted using a DAPI-containing antifade medium. Fluorescence images were acquired using FITC and DAPI filter sets on an Axio Scope.A1 (Zeiss) fluorescence microscope.

4. Discussion

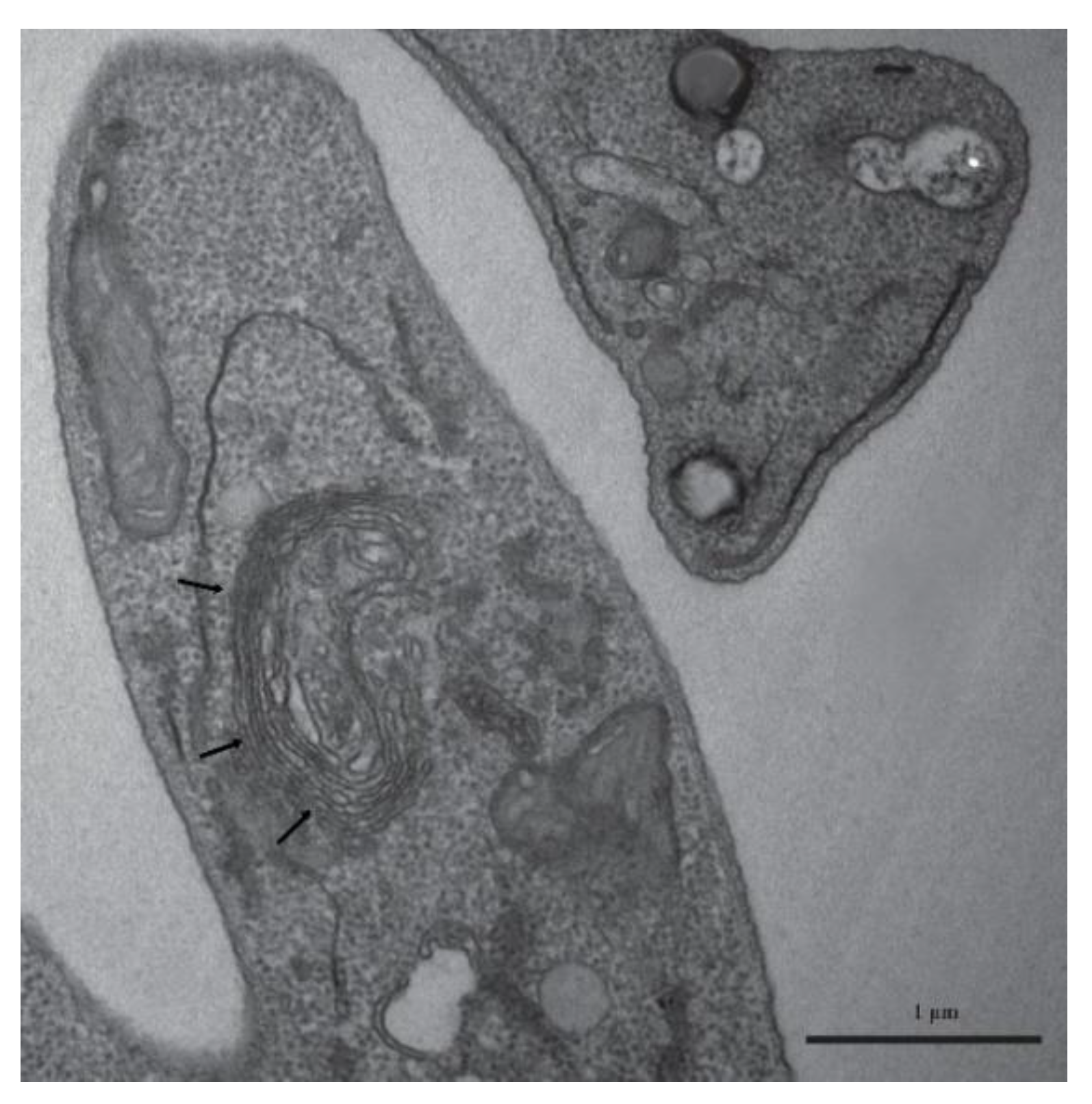

Our findings provide compelling experimental evidence that

Leishmania (

L.)

amazonensis produces lipid-rich structures intimately associated with

LEV biogenesis, reinforcing the growing recognition of lipids as central regulators of EV formation, cargo selection, and host–parasite communication in trypanosomatids [

1,

3,

7,

10,

11]. The pronounced vesicle accumulation observed in the flagellar pocket is consistent with its established role as the primary exocytic and endocytic hub in

Leishmania spp. and other trypanosomatids [

1,

2,

6,

25], supporting the notion that this compartment orchestrates membrane turnover, secretion dynamics, and the release of extracellular vesicles enriched in bioactive lipids.

The identification of lipid body–like inclusions in both promastigotes and intracellular amastigotes indicates active lipid metabolism and storage, processes increasingly linked to membrane remodelling, stress adaptation, and the packaging of lipid-derived effectors into LEVs [

3,

4,

6,

9,

11,

13,

25]. These structures resemble the neutral lipid bodies previously described in

Leishmania spp., which function as reservoirs for triacylglycerols, sterol esters, and phospholipid precursors essential for vesicle formation and parasite survival under nutrient-limited or oxidative stress conditions [

6,

9,

11,

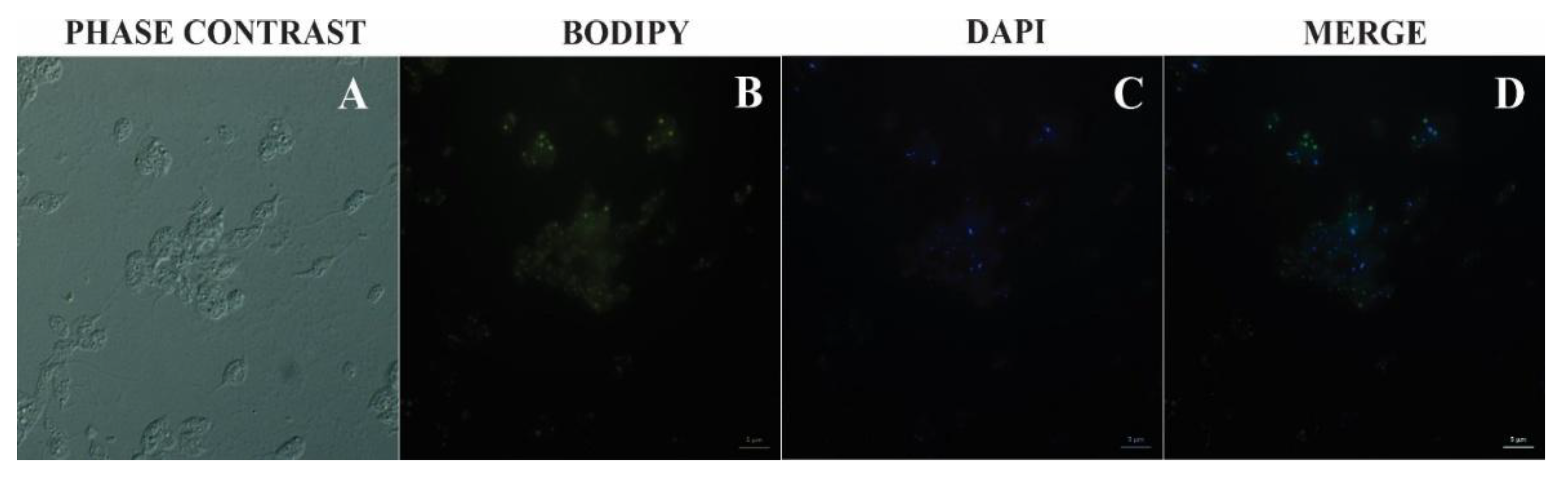

25]. Bodipy staining further corroborates the presence of neutral lipid pools, strengthening the hypothesis that lipid bodies contribute directly to LEV biogenesis and cargo loading, in line with current lipidomic and metabolomic approaches [

4,

10,

21].

The presence of Golgi-associated autophagic structures in stationary-phase promastigotes adds an additional layer of mechanistic insight. Autophagy has been implicated in vesicular trafficking and organelle recycling in trypanosomatids, and our observations support the idea that autophagy-related pathways may facilitate the generation of lipid-rich vesicles or regulate the turnover of membranes destined for secretion [

8,

12,

25]. This aligns with recent models proposing that autophagy intersects with EV biogenesis to modulate parasite adaptation, virulence, and metabolic plasticity, and is conceptually compatible with updated EV guidelines such as MISEV2023, which emphasize the importance of defining vesicle origin, cargo, and biogenesis pathways [

2,

22,

23].

Within infected macrophages, the detection of lipid-rich compartments surrounding intracellular amastigotes suggests that parasite-derived lipids and

LEVs may contribute to parasitophorous vacuole expansion, nutrient acquisition, and immune modulation. Previous studies have demonstrated that

Leishmania lipids can suppress inflammatory signalling, inhibit macrophage activation, and promote intracellular survival [

5,

8,

9,

14]. Lipid-enriched

LEVs are particularly well positioned to deliver such immunomodulatory molecules, including phosphatidylserine, sphingolipids, and eicosanoid-like mediators, which can alter host cell signalling, dampen pro-inflammatory responses, and reprogram macrophage metabolism [

1,

3,

7,

8,

9,

10,

14]. This view is further supported by translational and veterinary studies in canine leishmaniasis, where lipid-bound vesicles have been proposed as diagnostic and pathogenic markers [

24], and by methodological frameworks such as

Leishmania 360°, which advocate standardized approaches for exosomal and EV research in this genus [

23].

Importantly, the conceptual framework illustrated in

Figure 7 situates these cellular and molecular findings within broader evolutionary and ecological principles. Evo-Devo perspectives highlight how conserved developmental modules and membrane-based communication systems may have been co-opted by trypanosomatids to enhance adaptability and host exploitation [

16]. Comparative analyses with related parasites such as

Trypanosoma cruzi, which also relies on lipid remodeling and vesicle-mediated metabolic plasticity [

25], reinforce the idea that lipid-centered strategies represent an ancestral and evolutionarily conserved toolkit within the Trypanosomatidae. Niche theory provides a lens through which to interpret lipid-mediated interactions as mechanisms enabling parasites to occupy, modify, and stabilize intracellular environments [

17]. Epigenetic regulation, including lipid-dependent chromatin remodeling and metabolic signaling, may further influence parasite differentiation and stress responses [

18]. Finally, Red Queen co-evolutionary dynamics underscore how continuous host–parasite arms races drive innovation in communication strategies, including the evolution of lipid-rich EVs as tools for immune evasion and ecological specialization [

19,

20].

This evolutionary perspective is particularly relevant for zoonotic

Leishmania species, whose ecological distribution, vector associations, and host range diversification remain major global health challenges [

15,

20,

24]. By integrating ultrastructural, biochemical, methodological, and evolutionary insights, our results support a comprehensive lipid-centered model of LEV function in

Leishmania, influencing vesicle biogenesis, host modulation, intracellular survival, and long-term adaptive trajectories [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Together, these findings highlight lipid-rich LEVs as key mediators of parasite fitness and pathogenicity, and as promising targets for therapeutic intervention, biomarker discovery, and standardized EV-based research pipelines [

21,

22,

23,

24].

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally to the work. Roles: resources, conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, writing, review and editing, Á.M.G.; investigation, writing, review and editing, A.G.-P.; resources, investigation, formal analysis, writing, review and editing, W.L.A.P.; investigation, formal analysis, writing, review and editing, K.W.P.; resources, formal analysis, supervision, writing, review and editing E.O.d.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.