1. Introduction

Over the past decades, considerable interest has been devoted to the role of fundamental scalar fields in cosmology, particularly in connection with phase transitions in the early Universe and as potential candidates for dark matter [

1,

2]. This interest has naturally led to questions concerning the possible existence in nature of stable, soliton-like configurations of complex scalar fields. Such configurations are gravitationally bound by their self-generated gravitational field and are commonly referred to in the literature as boson stars (see, for example, comprehensive reviews in [

3,

4]).

In a seminal paper, Kaup [

5] obtained the first solutions of the Einstein-Klein-Gordon equations for a free, massive complex scalar field in spherical symmetry. One of the key results of this work is the existence of a maximum mass for boson stars composed of non-self-interacting bosons, above which the configurations become unstable. This maximum mass,

, is known as the Kaup limit, where

denotes the Planck mass and

m the mass of the scalar particle. Boson stars may be interpreted as macroscopic quantum states in which gravitational collapse is prevented by effective pressure gradients arising from the uncertainty principle. The Kaup limit implies that only configurations with masses below this bound are dynamically stable. The existence of such a limiting mass was later confirmed by subsequent studies, including both relativistic and non-relativistic analyses [

6].

The inclusion of self-interactions in the scalar field can significantly modify the properties of boson stars. In particular, Colpi, Shapiro, and Wasserman [

7] showed that for a repulsive quartic self-interaction described by the potential

, the maximum mass increases to

. A variety of other self-interaction potentials have been studied in the literature, leading to qualitatively similar enhancements of the maximum mass [

3].

Most early studies focused on nodeless wave functions corresponding to ground-state solutions. However, excited states characterized by one or more radial nodes have also been investigated. In general, the critical mass of the configuration increases with the number of nodes, both for non-self-interacting fields [

8] and in models including non-minimal coupling to gravity [

9]. In the latter, the authors found that the critical mass resulting from higher radial nodes grows approximately linearly for large node number n. These results suggest that when a nodeless configuration contains too many particles to remain in equilibrium, the possibility of an excited-state configuration achieving equilibrium cannot be ruled out. In fact, in the simplest case of a multi-state boson star consisting of a mix of the ground state and the first excited state, Ref.[

10] found that such a configuration is stable only if the number of particles in the ground state is larger than the number of particles in the excited state. Similar conclusions were obtained by the authors in Ref. [

11] in the non-relativistic regime, but with more severe conditions.

In the non-relativistic regime, it has been shown in Ref. [

12] that, in the specific case of a dilute charged Bose gas, the lowest-energy solution of the Gross-Pitaevskii (GP) equation does not correspond to a pure ground state. This contrasts with expectations from linear quantum theory, where all bosons would occupy the same single-particle state. Owing to the nonlinearity of the GP equation, the corresponding eigenstates are generally non-orthogonal, and the ground state may be more appropriately described as a mixed state, allowing a fraction of the bosons to populate higher excited energy levels. This eigenstate non-orthogonality leads to quantum correlations, manifested as off-diagonal terms in the associated density matrix. When the standard exponential time dependence of the eigenstates is introduced, this population of higher nonlinear excited states persists under time-dependent Hilbert-space projection methods [

13]. This property is fundamental when describing the lowest-energy state of interacting N-boson systems. As we shall see, such a mechanism may provide a natural explanation for the transitions between ground (nodeless) and excited (node-containing) states observed in the present investigation as the number of particles in the system increases.

Although excited state solutions either from the Einstein-Klein-Gordon or the Gross-Pitaevskii-Poisson (GPP) equations exist, the stability of these configurations still remains a matter of debate. In his original investigation of boson stars Ref. [

5] concluded that eigenstates with zero node are stable against radial perturbations. Adopting a formalism developed by Chandrasekhar, Ref.[

14] revisited the stability of boson stars and concluded that there is an upper bound for the central density above which the configuration becomes dynamically unstable against radial perturbations. This occurs both for free or repulsive self-interacting potentials. Surprisingly, the results by [

14] indicate that the instability occurs for masses

than the critical value, contrary to usual beliefs. A similar result was obtained in Ref. [

15]. On the one hand, Ref. [

8] suggests that boson stars described by multi-node solutions are unstable against fission that is, the mass of the configuration cannot grow indefinitely. On the other hand, Ref. citejetzer1989b concluded that excited bosonic stars are stable against radial perturbations if their central density remains below a certain critical value.

More recently, bosonic configurations including excited states were studied in the Newtonian limit in references [

17,

18]. In the former, using the GPP equations, the authors studied bosonic configurations including the first three radially excited states besides the ground level, and adopting the Thomas-Fermi approximation to derive solutions including a large number of particles. In the latter, the authors construct ground state solutions of the GPP equations using genetic algorithms together with empirical solutions.

In the present investigation, we revisit the stability of self-gravitating bosonic configurations in the non-relativistic regime, and employ the virial relation as a diagnostic criterion for dynamical equilibrium. We present numerical solutions of the nonlinear GPP system of equations, confirming the existence of excited equilibrium states above a critical number of particles. By adopting an appropriate coordinate transformation together with a specific gauge choice for the gravitational potential, the GPP system can be recast into a dimensionless form that is independent of the physical parameters characterizing the model. Within this formulation, each equilibrium configuration is uniquely specified by the central value of the dimensionless wave function, which determines the central density once physical units are restored. We find excited-state solutions that satisfy the virial relation provided that their central densities remain below the critical value,

, where the boson mass

m is expressed in eV, in agreement with previous studies. At this critical density, beyond which no equilibrium configurations are found, the total mass of the system is comparable to the limiting mass obtained in Ref. [

7] from solutions of the Einstein-Klein-Gordon equations. This paper is organized as follows: in

Section 2 we present the GPP equations and the associated coordinate transformation; in

Section 3 we discuss the numerical results; and in

Section 4 we summarize the main conclusions.

2. Basic Equations

A boson star can be considered as a macroscopic quantum state of degenerate bosons confined by their self-gravitational field. In the Hartree approximation, the structure of the system is dictated by uncorrelated single-particle stationary states of the average potential created by the assembly of particles. In other words, the Hartree approach can be imagined as a one-body self-consistent Schrödinger equation, where the potential energy depends on the wave-function itself. This dependence introduces the nonlinearity of the quantum system.

Let

be the normalized single-particle wave-function and

be the macroscopic system wave-function in the Hartree sense. In this case, if

is the particle density and

N is the total number of particles of the system, one has:

Clearly, the relation above implies the normalization condition

Considering spherical symmetry, the radial component of the single-particle wave function satisfies the equation (only

l = 0 states are considered)

In the equation above,

is the binding energy (or the chemical potential) of the system,

is the gravitational energy and the last term on the left side corresponds to the ground state of a hard-sphere potential [

13], where the coupling parameter

g is given by

with

being the scattering length parameter. Notice that in the non-relativistic regime, the hard-sphere potential leads to an equation of state

, similar to that derived from a self-interacting potential of the form

(see, for instance, [

7,

20,

21]). In this case, the scattering length parameter

is related to the coupling constant

by

The gravitational potential obeys the well known Poisson equation, that is

In order to solve numerically the system of non-linear Equations (

3) and (

6), it is convenient first to define adequate dimensionless variables. We introduce the gravitational Bohr radius

and a distance scale

equal to the geometric mean of the scattering length and the Bohr radius, i.e.,

, which permits to define the dimensionless coordinate

. We define also the energy scale

to which both the gravitational and the binding energies will be referred, e.g.,

and

. Finally, define the dimensionless wave function

by

and introduce the gauge transformation

With these definitions, the Gross-Pitaevskii-Poisson equations become respectively

and

Under these transformations, the normalization condition expressed by Equation (

2) yields a ”reduced” number of particles

, that is

It is worth mentioning that the differential system of Equations (

9) and (

10) does not depend explicitly on any parameter like the scattering length or the boson mass. The solution depends only on the boundary conditions, which are the following: the central values of the potential

and of the reduced wave function

. The latter is related to the central density of the configuration as we shall see below. The other remaining conditions at the center require

(zero gravitational acceleration) and

(maximum probability to find a particle). The eigenfunction must satisfy also the limit

.

Once a solution for the wave function

is found, the eingenvalue or the binding energy

can be computed from Equation (

8) using the central values, that is

, and where the gravitational energy at the center of the configuration is

3. Numerical Solutions of the GPP Equations

The system of differential Equations (

9) and (

10) was solved numerically under the conditions specified above. Since our interest lies in configurations containing a large number of particles (

), the behavior of the numerical solutions was monitored by comparison with the analytical solution obtained in the Thomas-Fermi (

) approximation, which, in our variables, is given by

It should be noted that this result is obtained by introducing a cutoff in the normalization condition given by Equation (

11), since the corresponding integral does not converge when the upper limit is extended to infinity. The cutoff is therefore imposed at the first zero of the solution, namely at

, where the density vanishes. This prescription also allows one to define an effective radius

R for the configuration, given by the well-known relation

. Excited-state solutions likewise exhibit one or more radial nodes. In this case, however, the integral in Equation (

11) converges without the need for an explicit cutoff. Nevertheless, it is not obvious whether the radial density profile should be extended in practice beyond the first zero of the wave function. In such regions, positive density gradients opposing gravity arise, potentially favoring the development of Rayleigh-Taylor-type instabilities in the outer layers of the configuration.

Numerical solutions of the GPP system were obtained by progressively increasing the central amplitude of the wave function, which is equivalent to increasing the central density of the configuration.

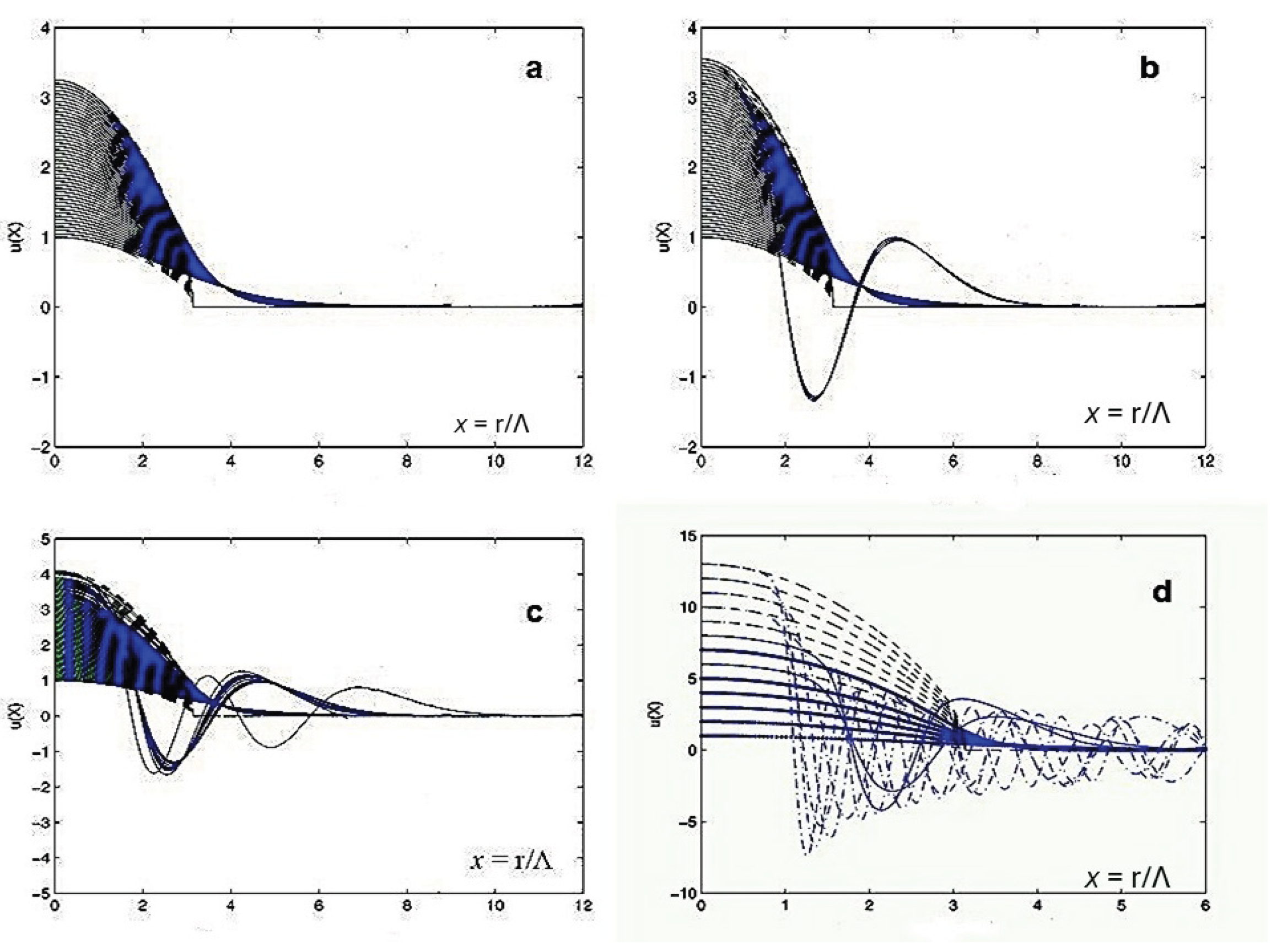

Figure 1 , comprising panels

, illustrates the behavior of the solutions as the central value of the wave function (or, equivalently, the relative central density) is varied. Panel

shows solutions of the GPP system for central amplitudes in the range

, corresponding to a reduced particle number in the interval

. In this regime, only ground-state (nodeless) solutions are found, and they agree well with the Thomas-Fermi approximation, as illustrated in

Figure 1(a).

As the central amplitude

is increased further, the first excited state, characterized by a two-node wave function, appears once the critical value

is exceeded, as shown in

Figure 1(b). However, for amplitudes larger than

, the ground state reappears. A further increase in

leads to the emergence of a four-node excited state with a reduced particle number

(see

Figure 1(c)).

Although the present computations correspond to a sequence of stationary configurations, they suggest that when the system occupies an excited state, small variations in the number of particles may trigger transitions toward ground-state configurations with fewer particles. To determine whether the apparent discreteness observed in the plane could be a numerical artifact, we inverted the calculations by decreasing the central amplitude using slightly different step sizes. The same qualitative behavior was recovered, indicating that this feature is intrinsic to the nonlinear nature of the system. This strongly suggests the presence of bifurcation points that modify the topological structure of the solution space.

This behavior is qualitatively similar to that reported in Ref. [

8], where solutions of the Newtonian limit of the Einstein-Klein-Gordon equations were studied. In the plane defined by the total mass and the number of particles, configurations corresponding to a fixed excitation level exhibit a mass that increases with particle number until a critical point (a cusp) is reached. Beyond this point, a new branch emerges in which configurations possess higher masses but fewer particles, until a second cusp is encountered. In this new branch, which is always shorter than the preceding one, the mass again increases with particle number, and the process repeats at successive critical points.

Dynamical studies of boson star collapse without self-interactions reported in Ref. [

22] showed that collapsing configurations can eject particles through a process known as gravitational cooling (see also Ref. [

23]). These simulations indicate that an initial configuration with a mass exceeding the critical limit by approximately 1.7% loses about 13% of its mass during the collapse. More recently, Ref. [

10] investigated the dynamical evolution of boson stars composed of a mixture of two states. Stable configurations were found when the number of particles in the ground state exceeds that in the excited state. In the opposite case, the system becomes unstable and evolves toward a stable configuration through particle emission.

Finally, as the central amplitude is increased beyond

, a two-node excited state reappears around

, while the ground state is recovered near

. At

, the two-node state appears once more, and a further increase in

leads to increasingly irregular behavior, as illustrated in

Figure 1(d).

For these solutions, the ground state binding energy (chemical potential) varies approximately linearly with the number of particles, while the width of the eigenstate wave function decreases as

. The eigenvalues can be approximated by

This relation will be used later when the maximum mass of a stable configuration will be estimated.

3.1. The Virial Relation

The stability of the configurations can be studied by estimating the virial relation for models characterized by different parameters. This relation is especially significant in the study of self-gravitating systems, such as bosonic stars or condensates, which can form due to the gravitational collapse. In quantum mechanics, the virial relation provides a powerful relationship between the average value of kinetic and potential energy of a quantum system, particularly in bound systems. Formally, it states that for a stable equilibrium, the average kinetic energy and the effective potential energy are related by the equation (see, for instance, [

24] for a derivation)

where

T is the kinetic energy operator and

is the effective potential operator including the gravitational and the self-interaction contributions.

In our variables, the virial relation is expressed as

For central amplitudes

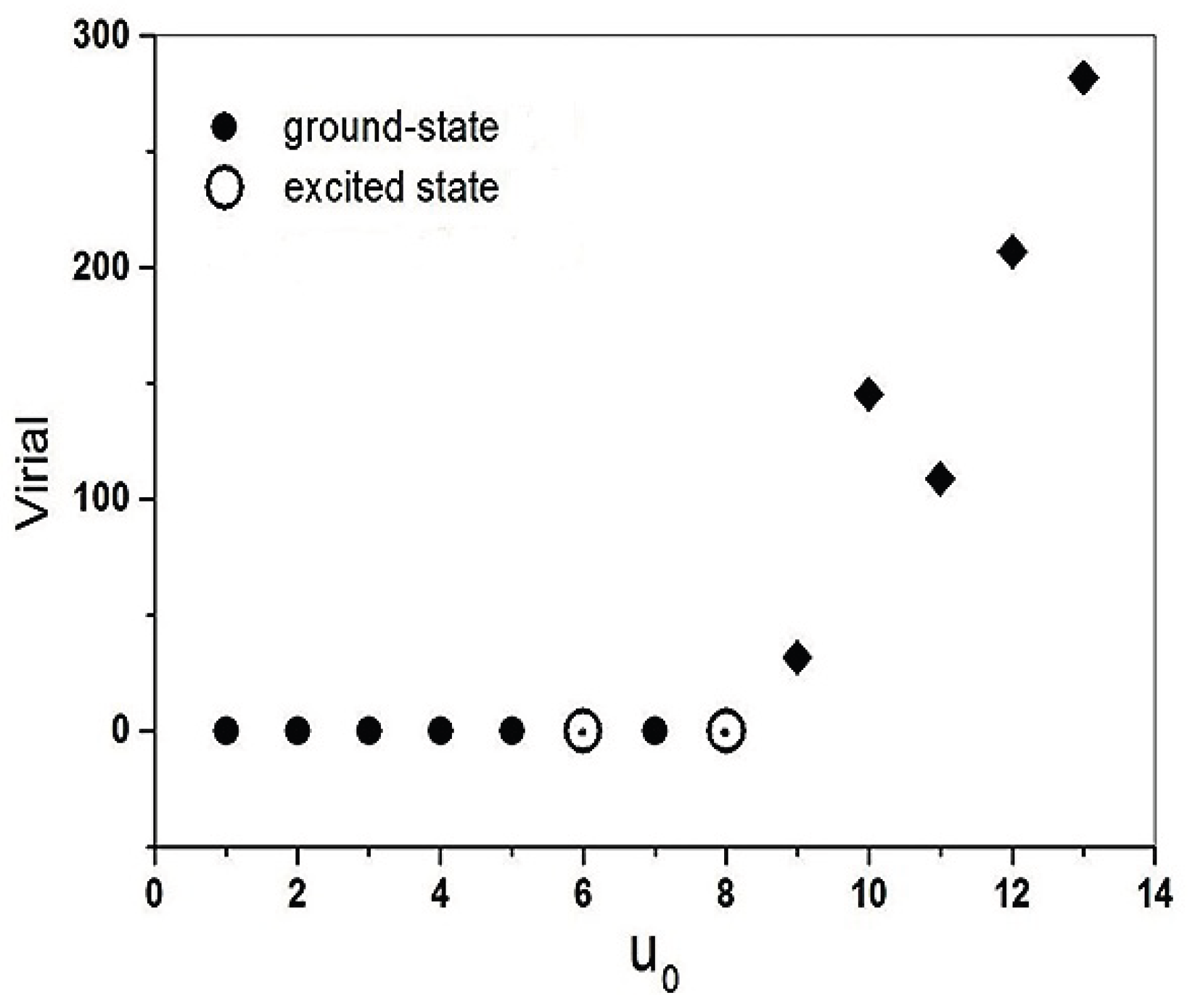

, our numerical computations indicate that the virial relation is satisfied by equilibrium configurations corresponding to both ground and excited states, as illustrated in

Figure 2. Above the critical density, corresponding to

or to a maximum reduced particle number

, the virial relation is no longer satisfied. In this regime, the virial becomes positive, indicating that the system departs from equilibrium and is therefore expected to be unstable. This behavior suggests that, beyond the critical point, the balance between gravitational attraction and repulsive self-interactions is no longer sufficient to support stationary configurations.

While some excited-state configurations still satisfy the virial relation, one might be tempted to interpret them as dynamically stable. However, the corresponding particle numbers of these excited configurations exceed those of the ground-state solutions predicted by the Thomas-Fermi approximation. This indicates that such configurations do not represent the true equilibrium state of the system, in the sense discussed in Ref. [

10], and should instead be regarded as metastable. It is therefore expected that these excited configurations decay toward the ground state through the emission of particles, known as the gravitational cooling mechanism.

The central critical density depends on the wave function central amplitude and on the coupling constant

, e.g.,

In order to evaluate the equation above, an estimate for the coupling constant

is required. This can be obtained from the present results combining the relation between the chemical potential and the reduced number of particles

(Equation (

14)) with Equation (

5) that is,

where

is the value derived from the present computations at the virial break-up, e.g.,

. Performing the numerical evaluation of the equation above one obtains

, where the boson mass is in grams. This value agrees quite well with the result derived by [

15] based on a different approach. Replacing the value of

in Equation (

17) and using the maximum allowed value of the central amplitude, e.g.,

it results

where now the boson mass is in eV. For axion-like bosons particles with masses around

, the estimated central density is about 10 orders of magnitude higher than that prevailing in the core of neutron stars. This is a consequence of the fact that neutrons are subjected to the Pauli exclusion principle, which avoids the development of stellar cores having larger densities.

3.2. The Critical Mass

A fundamental property of self-gravitating bosonic configurations is the existence of a critical (maximum) mass above which equilibrium solutions cease to exist or become dynamically unstable. This feature is common to both relativistic and nonrelativistic descriptions of boson stars and reflects the competition between gravity, quantum pressure, and possible self-interactions of the scalar field. In the relativistic framework, solutions of the Einstein-Klein-Gordon equations show that boson stars possess a maximum mass along the branch of stable equilibrium configurations, commonly identified with the Kaup limit in the absence of self-interactions, or with its generalizations when repulsive self-interactions are included. Beyond this maximum mass, no stable stationary solutions are found.

In the nonrelativistic regime described by the GPP system, a similar notion of critical mass emerges. Although the GPP equations do not incorporate relativistic effects explicitly, they nevertheless exhibit a limiting mass associated with the breakdown of equilibrium configurations. As the number of particles (or, equivalently, the central density) is increased, solutions approach a critical point beyond which the virial balance can no longer be satisfied. This critical mass therefore represents the maximum mass for which a self-gravitating bosonic configuration can remain in equilibrium within the validity of the nonrelativistic approximation.

Within the framework of the present study, the concept of critical mass emerges naturally from the numerical solutions of the GPP system. As shown in the previous sections, equilibrium configurations are parametrized by the central amplitude of the wave function, or equivalently by the reduced particle number . As is increased, the system follows a sequence of stationary solutions until a critical point is reached beyond which no equilibrium configuration satisfying the virial relation can be found. This behavior provides a clear operational definition of the critical mass within the nonrelativistic GPP approach.

In the nonrelativistic regime, the gravitational mass of the configuration is given by the total rest mass of the particles corrected by the binding energy arising from the GPP equations. Accordingly, the gravitational mass of a boson star in the ground state can be written as

For ground-state configurations, the present calculations show that the binding energy per particle, characterized by the chemical potential

, varies linearly with the reduced number of particles

(see Equation (

14)), namely

where the physical constants were restored.

Defining the characteristic mass scale

, and making use of the previously introduced dimensionless variables, Equation (

19) can be recast in the form

In this expression, the scattering length has been replaced by the coupling constant

according to Equation (

5). The maximum value of

is obtained from the condition

, which yields

This result was already used in the previous section to estimate the coupling constant

, since the present numerical analysis gives

. Substituting Equation (

22) into Equation (

21), one obtains the maximum mass

The numerical coefficient appearing in this expression is approximately 2.8 times larger than that obtained in Ref. [

7] from a fully relativistic analysis. For axion-like bosons with masses of order

, the resulting maximum mass is of the order of 30 Earth masses, a quite small value despite the fact that the corresponding central densities exceed nuclear densities by several orders of magnitude.

Ground-state solutions are nodeless and formally extend to infinity, which makes the definition of a sharp stellar radius ambiguous. In practice, the size of the boson star is characterized by the radius

, defined as the radius enclosing 99% of the total particle number.

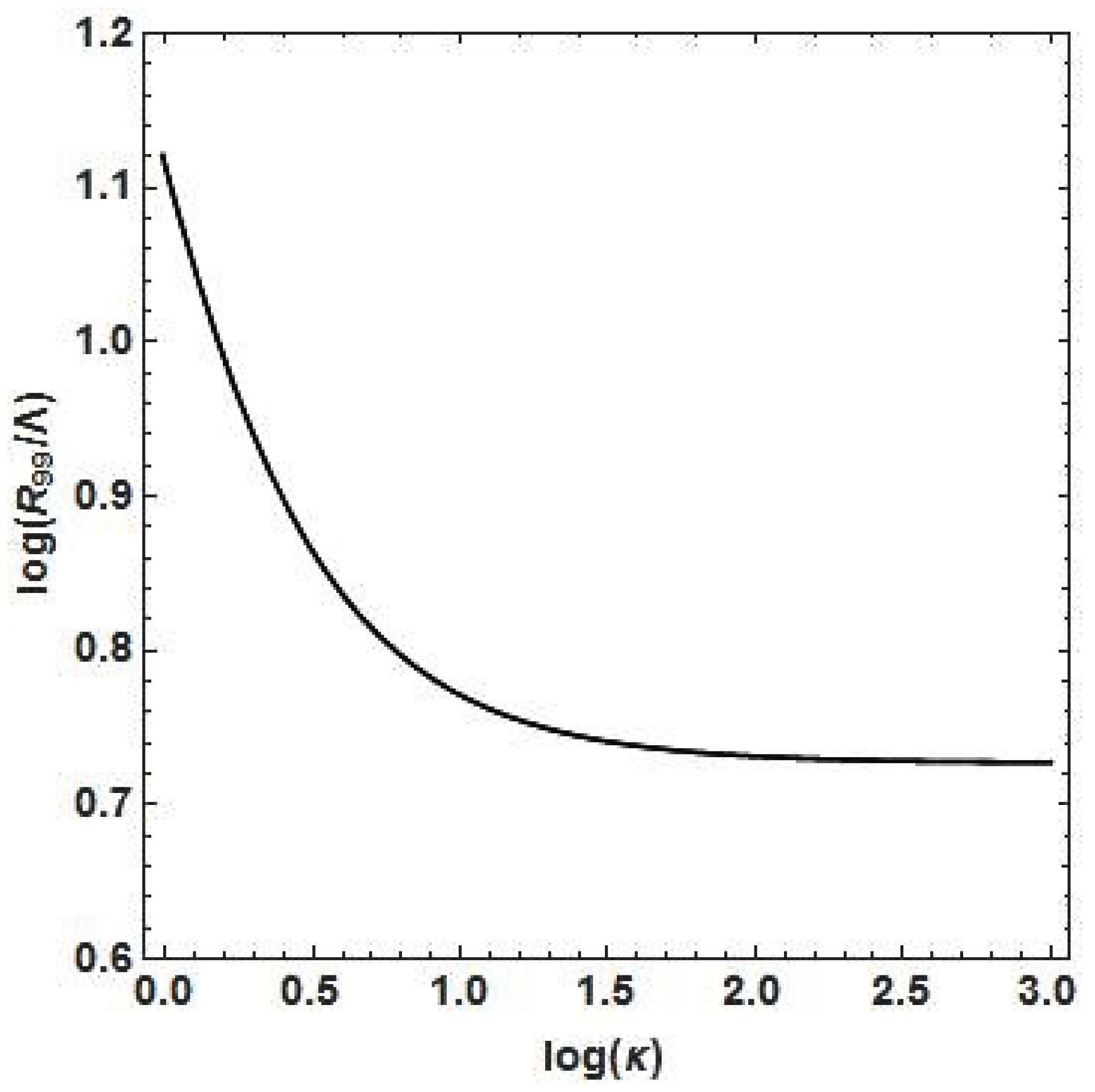

Figure 3 shows the dependence of the dimensionless radius

on the reduced number of particles

. For

, the effective radius scales approximately as

, whereas for large particle numbers the radius approaches a nearly constant value,

. Notice that the characteristic length scale

can be expressed uniquely in terms of the Compton wavelength of the boson,

Using this relation and inserting numerical values, one finds that for large particle numbers the typical size of boson stars is for a boson mass of . This extreme compactness naturally explains the very high central densities obtained in the present models. However, since , and , lighter bosons will lead to more massive configurations having smaller central densities and larger sizes.

4. Conclusions

In the present work, we have reported new numerical solutions of the nonlinear Gross-Pitaevskii-Poisson system of equations with the aim of investigating the equilibrium and stability properties of boson stars in the nonrelativistic regime. By adopting an appropriate coordinate transformation together with a specific gauge choice for the gravitational potential, the resulting system of equations becomes independent of the physical parameters characterizing the model. Within this formulation, equilibrium solutions are fully specified by the usual boundary conditions and by the central value of the dimensionless wave function, which uniquely determines the central density of the configuration once physical units are restored.

Numerical solutions were obtained by incrementing the central amplitude of the wave function using a fine grid. Although only stationary configurations were computed, the analysis revealed the presence of bifurcation points at which transitions between ground-state and excited-state solutions occur. The results further suggest the existence of a limiting value of the central amplitude beyond which the solutions become increasingly irregular, possibly involving mixtures of different states, signaling the breakdown of simple equilibrium configurations.

The virial relation was evaluated for a wide class of models corresponding to both ground and excited states. Previous investigations have shown that virialized ground-state configurations are dynamically stable against small perturbations [

23]. In the present study, we find that the virial relation is satisfied only for configurations whose central amplitude lies below a critical value. This implies that stable equilibrium configurations cannot possess central densities exceeding a well-defined critical limit, in agreement with earlier analyses based on the evolution of radial oscillations [

15]. Remarkably, this critical density exceeds typical nuclear densities by several orders of magnitude if axion-like bosons with masses of order

are considered.

As shown in

Figure 2, some excited-state configurations also satisfy the virial relation, which might suggest dynamical stability. However, since these configurations contain a larger number of particles than the corresponding ground-state solutions predicted by the Thomas-Fermi approximation, they should be regarded as metastable. Such states are therefore expected to decay toward the ground state through particle emission, most likely via the gravitational cooling mechanism (see, for instance, Ref. [

23]).

For central densities exceeding the critical value, the virial becomes positive, indicating a loss of equilibrium and the onset of instability. In this regime, the gravitational attraction is no longer sufficient to counterbalance the repulsive self-interactions. The ultimate fate of such unstable configurations remains an open question and depends on relativistic effects not captured by the GPP system. Fully relativistic numerical simulations have shown that unstable boson stars with negative binding energy tend to collapse and form black holes, whereas configurations with positive binding energy disperse to infinity [

25,

26]. Other studies have identified multiple possible end states, including collapse, dispersal, or relaxation toward a less compact stable configuration, highlighting the rich dynamical behavior of unstable bosonic systems [

27,

28].

An estimate of the boson-star size was obtained by defining the radius enclosing 99% of the total number of particles. For the same boson mass, namely , we find , indicating an extremely compact object, which naturally explains the very high central densities found in the present models. Finally, the ratio between the Schwarzschild radius and the effective stellar radius is found to be , indicating that the configurations considered here lie close to the limit of validity of the Newtonian approximation.