1. Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB), defined as delivery before 37 weeks of gestation, remains one of the most pressing public health issues globally, affecting more than 15 million newborns each year [

1]. PTB is a complex condition influenced by the interplay of biological, environmental, and social factors. From a biological perspective, several maternal health conditions contribute significantly to the risk of preterm delivery. Infections and inflammation, particularly genital tract infections such as bacterial vaginosis, urinary tract infections, and chorioamnionitis, can activate inflammatory pathways that induce uterine contractions and rupture of membranes [

2]. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, are among the leading causes of medically indicated preterm birth [

1].

Similarly, maternal diabetes mellitus (whether pre-existing or gestational) often results in preterm delivery due to complications affecting the fetus. Nutritional deficiencies, such as anemia or low levels of iron, zinc, and vitamin D, also play a role in increasing vulnerability to early delivery [

1].

Genetic and epigenetic factors further influence susceptibility to PTB. A family history of preterm birth is one of the most consistent predictors, suggesting a heritable component [

1]. Research has identified single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes involved in inflammatory and hormonal regulation, such as IL-6 and TNF-

, that are associated with higher risk [

3]. Epigenetic modifications arising from maternal stress, diet, or environmental exposures can alter gene expression patterns in the placenta and developing fetus, creating a biological predisposition to premature labor [

4]. Anatomical and reproductive characteristics also contribute: a short cervical length, uterine anomalies, multiple gestations, and conception through assisted reproductive technologies have all been linked to increased PTB rates [

1]. Among the strongest predictors is a prior history of preterm birth. Moreover, dysregulation of endocrine and immune systems, particularly overactivation of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to elevated cortisol or a loss of immune tolerance at the maternal fetal interface can precipitate premature activation of parturition pathways [

5].

The social determinants of preterm birth are equally critical, shaping exposure to biological risks and mediating access to healthcare and resources [

6]. Socioeconomic disadvantage, often expressed through low income, limited education, and poor living conditions, is consistently associated with higher rates of PTB. Women living in marginalized or polluted neighborhoods are more likely to experience chronic stress, inadequate nutrition, and barriers to quality prenatal care. Psychosocial stressors, including intimate partner violence, workplace strain, and social isolation, influence neuroendocrine and immune function, thereby increasing physiological susceptibility to preterm labor [

5]. Racial and ethnic disparities in PTB reflect the cumulative effects of structural racism, chronic stress exposure, and unequal treatment within healthcare systems, rather than genetic differences [

6].

Health behaviors further mediate the relationship between social context and biological risk. Tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, and the use of illicit substances such as cocaine or methamphetamine are well-documented contributors to placental pathology and spontaneous preterm labor [

1]. Poor diet quality, inadequate maternal weight gain, and low levels of physical activity also increase risk, while delayed or insufficient prenatal care reduces opportunities for early detection and management of complications. Environmental and occupational exposures add another layer of complexity. Exposure to air pollutants such as fine particulate matter (PM

2.5), nitrogen dioxide, or heavy metals like lead and mercury has been associated with inflammation and oxidative stress leading to early delivery [

7]. Similarly, physically demanding labor, long working hours, or high job strain can contribute to preterm birth through cumulative physiological stress [

1].

The relationship between social and biological determinants is increasingly conceptualized through the framework of biological embedding, which explains how chronic social stress translates into physiological changes that predispose to PTB [

5]. Persistent exposure to adversity generates allostatic load—cumulative dysregulation of stress hormones, inflammatory responses, and oxidative processes compromising placental function, uterine contractility, and immune tolerance [

4]. This integrative perspective is complemented by the life-course approach, which emphasizes that social and environmental disadvantages accumulate across a woman’s life, long before pregnancy begins, ultimately shaping reproductive outcomes [

6]. Thus, preterm birth is not merely a medical event but a manifestation of broader social inequities interacting with biological systems across time and generations.

In Mexico, PTB contributes substantially to neonatal mortality and long-term complications, with social and biological determinants intertwined. As it was just discussed the multifactorial origins of PTB presents enormous challenges for its early diagnostics. Recent research suggests that alterations in the vaginal microbiome during pregnancy may contribute to the risk of PTB. Several research groups have hypothesized that the microbiome may, in spite of its inherent complexities, present itself as an alternative for early diagnosis of PTB.

The vaginal microbiome of healthy pregnancies is typically dominated by

Lactobacillus species that maintain low pH and provide protection against pathogenic bacteria [

8]. In contrast, dysbiotic profiles characterized by decreased

Lactobacillus abundance and increased microbial diversity have been associated with PTB [

9]. However, findings across populations remain inconsistent, possibly due to ethnic, geographic, and methodological heterogeneity. Therefore, region-specific studies are essential to identify microbial predictors relevant to Latin American populations [

10].

Machine learning (ML) has become an important tool for biomarker discovery and risk prediction in microbiome studies [

11]. By integrating and analyzing high-dimensional data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and clinical sources, machine learning algorithms can identify complex, nonlinear patterns that traditional statistical methods often miss [

12]. These models enable the detection of subtle biological signatures associated with disease onset, progression, or treatment response, supporting the development of precision medicine strategies. Furthermore, predictive models trained on large-scale datasets can estimate individual disease risk with increasing accuracy, offering clinicians data-driven tools for early diagnosis, targeted intervention, and improved patient stratification. However, the application of ML to small, high-dimensional microbiome datasets is still challenging due to potential overfitting and instability of feature selection. Here, we present a systematic ML framework for predicting PTB using vaginal microbiome data from a Mexican cohort. We compare several algorithms, evaluate model stability, and discuss implications for future integrative multi-omic studies.

Pregnancy involves profound physiological and immunological changes that influence microbial ecology. The vaginal ecosystem transitions across gestation, with hormonal fluctuations shaping microbial succession and host-microbe interactions [

13]. Characterizing these temporal shifts is crucial, as perturbations may predispose to adverse outcomes such as PTB. Studies integrating microbiome dynamics with clinical data could reveal predictive patterns long before clinical manifestation. Furthermore, Latin American populations have been underrepresented in microbiome research, which limits the generalizability of current predictive models [

10]. Environmental exposures, dietary factors, and healthcare access differ markedly from those in populations where most microbiome studies have been conducted. As such, the development of population-specific models is essential to understand how social and biological determinants interact in shaping PTB risk.

Another important consideration is the compositional nature of microbiome data. Because sequencing data represent relative abundances constrained to a constant sum, traditional statistical analyses can yield spurious correlations [

14]. Compositional data analysis (CoDA) techniques, such as centered log-ratio transformation, are necessary to properly handle these dependencies [

15]. Incorporating CoDA principles within machine learning pipelines enhances interpretability and avoids misleading associations.

Finally, reproducibility and methodological transparency are paramount in microbiome-based ML research [

16]. Many published models lack rigorous cross-validation, leading to inflated performance estimates [

17]. By following a standardized, open, and reproducible workflow, the present study contributes to improving methodological rigor and ensuring that future predictive microbiome models are robust and clinically translatable.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This exploratory study analyzed vaginal microbiome samples from 43 pregnant women enrolled at the Hospitals Dr. Enrique Cabrera and Centro de Salud Jalalpa El Grande, from the Secretaría de Salud del Gobierno de la CDMX, Mexico City, Mexico. The cohort was designed as a nested case-control study including 14 preterm births (PTB, defined as delivery <37 weeks of gestation, representing 32.6% at subject level—comprising 13 spontaneous preterm deliveries and 1 pregnancy loss at 20 weeks analyzed as PTB) and 29 term births (≥37 weeks, 67.4%). Longitudinal sampling throughout pregnancy yielded 110 total observations (mean 2.6 samples per subject, range 1–6 samples), with 24 preterm-associated samples and 86 term-associated samples (21.8% of samples from PTB pregnancies). This enriched sampling design provided adequate representation of both outcome classes despite the modest total sample size, while the longitudinal approach captured temporal microbiome dynamics relevant to clinical practice where multiple prenatal visits occur.

Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are being finalized and will be reported in subsequent publications; however, the cohort comprised singleton pregnancies with documented gestational age, availability of vaginal microbiome samples collected using standard swab techniques, and complete clinical metadata. All participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the research and ethics committees of the Secretaría de Salud de la Ciudad de México (SEDESA CDMX) and the Comisión Nacional de Bioética, with registration numbers 210-101-31-17 (SEDESA CDMX), CONBIOETICA-09-CEI-004-20180213 (Comisión Nacional de Bioética), and 110-010-10-19 (SEDESA CDMX, protocol extension).

2.2. Microbiome Profiling and Data Preprocessing

Vaginal microbiome swabs were collected and processed following standard protocols for low-biomass samples (detailed methodology to be reported elsewhere). Briefly, samples were stored at -80°C, DNA was extracted, and the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified and sequenced on the Illumina platform, generating paired-end reads. Bioinformatics processing followed the standard QIIME2 workflow, including quality filtering, denoising using DADA2, chimera removal, and taxonomic assignment to genus level using the SILVA reference database (version 138), yielding genus-level relative abundance profiles.

Quality control steps included: (1) filtering to retain genera present in ≥5% of samples (59 of 97 genera retained), reducing noise from rare, potentially artifactual taxa; (2) Shannon diversity index calculation from untransformed relative abundances to capture both richness and evenness of microbial communities; (3) zero imputation using geometric Bayesian multiplicative replacement to handle compositional zeros before transformation; and (4) closure (renormalization) ensuring relative abundances summed to 1.0.

Centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation was applied to address the compositional constraint inherent in microbiome data [

14,

15]. Critically, CLR transformation was performed

within cross-validation folds—separately for each training set—to prevent data leakage. Test set samples were transformed using the geometric mean calculated exclusively from the corresponding training set.

2.3. Differential Abundance Analysis

We applied ANCOM-BC2 (Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes with Bias Correction) [

18] to identify genera whose abundances differed significantly between preterm and term births. ANCOM-BC2 addresses compositional data constraints and performs bias correction, making it particularly suitable for small-sample microbiome studies. To prevent data leakage, ANCOM-BC2 was executed independently within each outer cross-validation fold using only training set samples. For each fold, differential abundance testing employed the formula: preterm ∼ maternal age + pre-pregnancy BMI, with library size cutoff = 1,000 reads; prevalence threshold = 5%; FDR adjustment using Benjamini-Hochberg method; and significance threshold p<0.10 (liberal threshold justified by exploratory nature and small sample size). Taxa meeting this threshold in a given fold were selected as features for that fold’s model training. Across the 5 outer folds, ANCOM-BC2 identified varying numbers of differentially abundant taxa, reflecting the small sample size and inherent variability in fold composition.

2.4. Clinical Feature Selection Strategies

We systematically compared three conceptually distinct approaches to clinical feature selection, each representing different modeling philosophies:

2.4.1. Approach 1: DREAM Challenge-Style Minimal Clinical Adjustment

This parsimonious approach included only gestational age at sampling (continuous, weeks) and maternal age (continuous, years), maximizing comparability with the Microbiome Preterm Birth DREAM Challenge benchmarks [

11] while testing whether microbiome features provide predictive value beyond basic demographic confounders.

2.4.2. Approach 2: Literature-Based Comprehensive Features

Leveraging established epidemiological literature [

1], we selected 10 clinical variables with strong evidence for PTB associations: gestational age at sampling (continuous, essential for timing-dependent risk), maternal age (continuous, U-shaped risk relationship) [

1], pre-pregnancy BMI (continuous, both extremes increase risk), altitude-adjusted hemoglobin (continuous measure preferred over categorical anemia diagnosis), folic acid intake (some evidence for protective effect), first-trimester bleeding (OR 1.4–2.4 depending on severity) [

19,

20], preeclampsia (strong PTB association) [

1], preterm premature rupture of membranes (direct PTB mechanism), oligohydramnios (marker of placental insufficiency), and gestational diabetes (OR 1.51, 95% CI: 1.26–1.80) [

21]. This parsimonious approach focuses on the most robust and clinically available predictors while maintaining interpretability.

2.4.3. Approach 3: Data-Driven Univariate Screening

To identify population-specific risk factors while preventing data leakage, univariate screening was performed independently within each outer cross-validation fold using only that fold’s training data. For each fold, we tested all available clinical variables using logistic regression, applying a liberal significance threshold (p<0.20) justified by small sample size and exploratory objectives. From variables meeting this criterion, we selected the top 10 by p-value rank to balance predictive power with overfitting prevention. Critically, this selection process was repeated de novo for each CV fold, ensuring that feature selection decisions never used information from test data. The resulting feature sets varied across folds, reflecting both biological signal and sampling variability inherent in small-sample studies. Common selections included extreme BMI (selected in 80% of folds), first-trimester bleeding (80%) or extreme maternal age (80%).

2.5. Microbiome Feature Engineering

Two complementary microbiome feature strategies were evaluated:

2.5.1. Option A: ANCOM-BC2 Differentially Abundant Taxa

This focused approach included CLR-transformed abundances of the 7 genera identified by ANCOM-BC2 plus Shannon diversity index (8 features total), providing strong dimensionality reduction while retaining taxa most likely associated with PTB pathophysiology.

2.5.2. Option B: Full Filtered Microbiome

All 59 prevalence-filtered genera were included as CLR-transformed abundances plus Shannon diversity (60 features total). This comprehensive approach maximized information content, allowing machine learning algorithms to identify complex multivariate patterns not detected by univariate differential abundance testing.

2.6. Machine Learning Models

We selected two complementary algorithms based on proven performance in small-sample microbiome studies:

2.6.1. Random Forest

Random Forest [

22], an ensemble of bootstrap-aggregated decision trees, was selected for its: (1) proven track record in the DREAM Challenge [

11]; (2) reliability in studies with n<150 [

12]; (3) native handling of high-dimensional data through feature subsampling; and (4) robustness through ensemble averaging. Hyperparameters were fixed

a priori (trees=500, mtry=4, min_n=10) rather than optimized, reducing overfitting risk and enhancing reproducibility. Implementation used the

ranger package (v0.16.0) in R.

2.6.2. Elastic Net

Elastic Net logistic regression [

23] combines L1 (LASSO) and L2 (Ridge) penalties, providing: (1) linear interpretability through direct coefficient quantification; (2) built-in feature selection via L1 penalty; (3) multicollinearity handling through L2 penalty; and (4) explicit regularization preventing overfitting. Hyperparameters were fixed at mixture (

)=0.5 (equal L1/L2 weighting) and penalty (

)=0.01 (moderate regularization). Implementation used the

glmnet package (v4.1-8) through the

parsnip interface.

We explicitly avoided more complex algorithms (XGBoost, deep neural networks) due to their sample size requirements (n≥200–500) and increased overfitting risk with n=43.

2.7. Nested Cross-Validation Framework

To ensure unbiased performance estimates and prevent data leakage, we implemented a rigorous two-loop nested cross-validation design separating threshold optimization from performance evaluation [

17].

2.7.1. Outer Loop: Performance Evaluation

Five-fold stratified cross-validation at subject level maintained PTB prevalence ( 33%) in each fold. All samples from a given subject were assigned to the same fold, preventing information leakage from repeated measures. The cross-validation setup comprised 43 total subjects with 14 PTB cases (32.6%). Folds 1–4 each contained 9 subjects with 33.3% PTB prevalence, while Fold 5 contained 7 subjects with 28.6% PTB prevalence. For each iteration, approximately 79% of subjects formed the outer training set and 21% the outer test set, with final evaluation occurring on outer test sets using no information from test data to influence training or threshold selection.

2.7.2. Inner Loop: Threshold Optimization

Within each outer training fold, a further 70/30 stratified split at subject level created inner training ( 24 subjects) and inner validation sets ( 10 subjects). Models were trained on inner training sets, and classification thresholds were optimized on inner validation sets using Youden’s Index (J = Sensitivity + Specificity - 1) [

24], which balances sensitivity and specificity without requiring clinical cost specification. The optimized threshold was then applied to the outer test fold without re-optimization, ensuring honest performance estimates.

2.7.3. Data Preprocessing Within Folds

All preprocessing occurred within CV folds to prevent data leakage: feature selection (univariate screening for Approach 3), CLR transformation (geometric mean from training set only), and imputation (median/mode from training set). Synthetic oversampling (SMOTE) was not used due to the extremely small minority class (only 5 PTB cases), as it risks creating unrealistic interpolated samples. Instead, we relied on stratified sampling, algorithms robust to class imbalance, and threshold-independent metrics (AUROC, PRAUC).

2.7.4. Critical Data Leakage Prevention Measures

Several preprocessing and feature selection steps were explicitly designed to prevent data leakage—a pervasive methodological issue that inflates performance estimates and produces non-reproducible results [

17,

25]. Our implementation ensures complete separation between training and test data at each CV fold:

(1) Feature selection for Approach 3: Univariate screening with p<0.20 threshold was performed independently within each outer fold’s training set. Variables selected in one fold were not forced into other folds; selection was repeated de novo for each iteration.

(2) ANCOM-BC2 taxa identification: Differential abundance analysis was executed separately for each outer fold using only that fold’s training samples. Taxa identified as differentially abundant in one fold were not guaranteed to be selected in other folds.

(3) CLR transformation: The geometric mean required for centered log-ratio transformation was calculated exclusively from each fold’s training set and applied to transform both training and test samples for that fold.

(4) Threshold optimization: Classification thresholds were optimized on inner validation sets and applied to outer test sets without re-optimization, preventing "double-dipping" that would bias performance upward.

These measures contrast with common but flawed practices where feature selection or normalization parameters are computed on the entire dataset before cross-validation, leading to optimistically biased performance estimates that fail to replicate in independent cohorts [

17].

2.8. Performance Metrics and Statistical Analysis

Model performance was evaluated using complementary metrics. Threshold-independent metrics included Area Under ROC Curve (AUROC, primary metric assessing discrimination) and Area Under Precision-Recall Curve (PRAUC, particularly informative for imbalanced datasets). Threshold-dependent metrics at the optimized Youden threshold included sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, balanced accuracy, and Youden’s Index itself. For subjects with multiple samples, probability predictions were averaged before classification, reflecting realistic clinical scenarios where multiple timepoints inform overall risk assessment.

All metrics were reported as mean ± standard deviation across the 5 outer CV folds, with standard deviation quantifying both model instability and task difficulty. All analyses were performed in R version 4.4.2 using the

tidymodels framework (v1.2.0), with fixed random seed (123) ensuring exact reproducibility. Complete code is available at [GitHub repository]. Following TRIPOD+AI guidelines [

26], we emphasize that given the exploratory nature and small sample size (n=43, 5 PTB), results are hypothesis-generating rather than definitive, requiring external validation in independent Mexican cohorts before clinical consideration.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

The study cohort comprised 43 pregnant women from Mexico City, contributing 110 vaginal microbiome samples collected throughout pregnancy. Fourteen women (32.6%) delivered preterm (<37 weeks of gestation), while 29 (67.4%) delivered at term. The longitudinal sampling strategy yielded a mean of 2.6 samples per participant (range: 1–6 samples), resulting in 24 preterm-associated samples and 86 term-associated samples (21.8% prevalence at sample level). Mean maternal age was 27.8 ± 5.3 years, with no significant difference between preterm and term groups (p=0.42). Pre-pregnancy body mass index averaged 26.4 ± 4.8 kg/m2, with 37.2% of participants classified as overweight or obese. The cohort exhibited typical risk factor distributions for the region, including anemia (18.6%), gestational diabetes (7.0%), and preeclampsia (4.7%).

Quality-filtered microbiome data comprised 59 genera present in ≥5% of samples. Compositional profiles showed substantial inter-individual variation, with vaginal communities dominated by

Lactobacillus (median relative abundance 65.2%, IQR 28.4–89.7%),

Gardnerella (median 8.3%, IQR 1.2–23.6%), and

Atopobium (median 2.1%, IQR 0.3–8.9%). Notably, 23.6% of samples exhibited low

Lactobacillus dominance (<50% relative abundance), consistent with previous observations in Hispanic/Latino populations. Principal component analysis revealed distinct clustering patterns with substantial overlap between preterm and term samples (

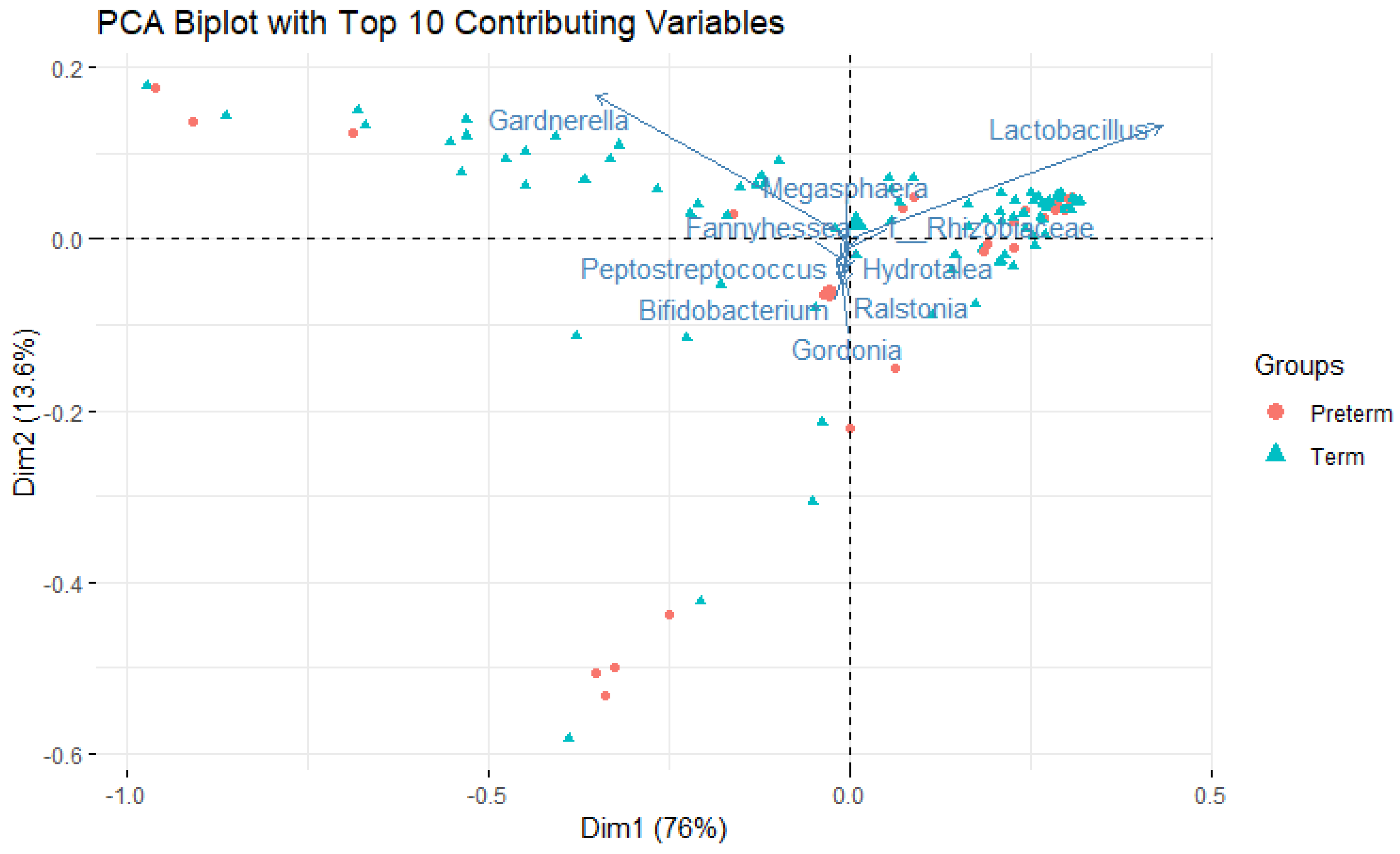

Figure 1), with the top 10 contributing genera shown as vectors.

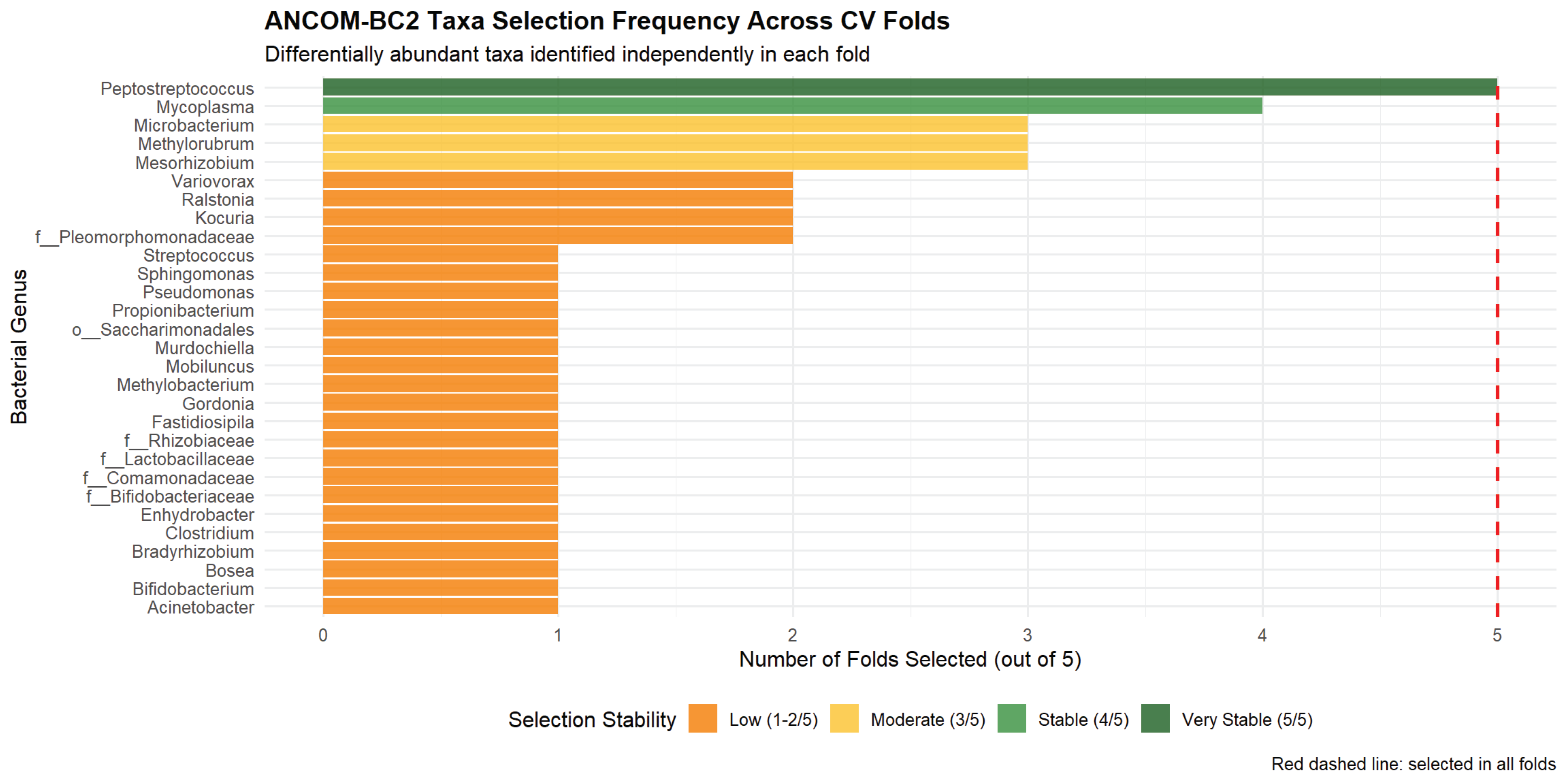

3.2. Differential Abundance Analysis

Within-fold ANCOM-BC2 analysis identified taxa with variable differential abundance patterns across the 5 cross-validation folds, reflecting both biological signal and sampling variability inherent to small datasets (

Figure 2).

Peptostreptococcus emerged as the most consistently selected taxon (present in 100% of folds), showing enrichment in preterm samples. This genus is associated with bacterial vaginosis and genital tract infections, with known roles in ascending infection and chorioamnionitis [

27,

28,

29].

Mycoplasma (selected in 80% of folds) also showed preterm enrichment; this cell-wall-deficient bacterium is implicated in intrauterine infection through membrane phospholipase activity and TLR2 activation [

30,

31]. Environmental taxa including

Mesorhizobium,

Methylorubrum, and

Microbacterium were selected in 60% of folds, highlighting the persistent challenge of low-biomass contamination in vaginal microbiome studies [

32,

33] and the need for rigorous negative controls in future work. The observation that no taxa were selected in all 5 folds underscores the statistical instability expected with only 2–3 PTB cases per fold and motivates the need for larger validation cohorts.

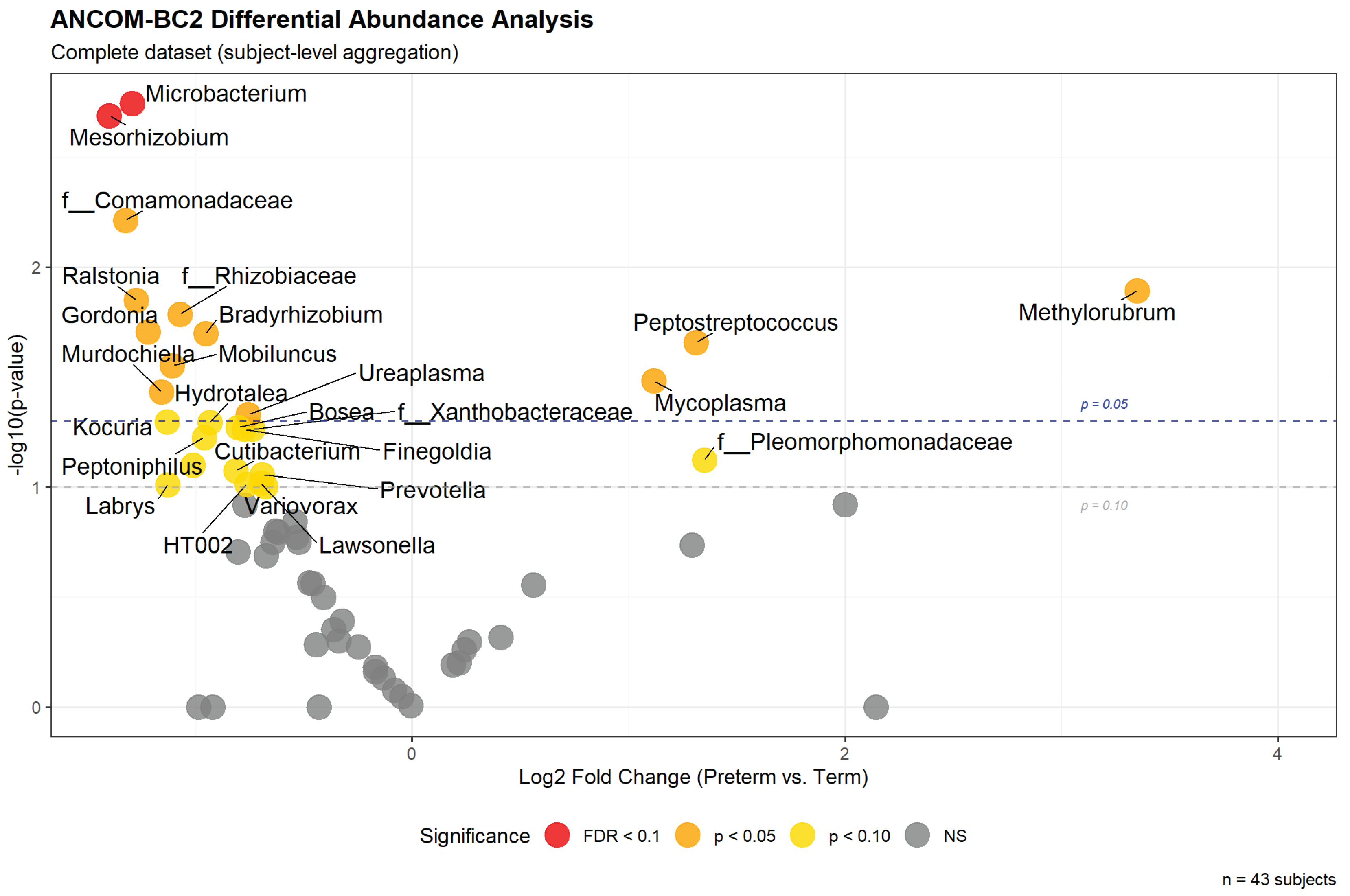

3.3. Global Differential Abundance Patterns

To provide a comprehensive overview of microbiome-PTB associations independent of cross-validation partitioning, we performed a supplementary ANCOM-BC2 analysis using the complete dataset with subject-level aggregation (n=43 subjects, 110 samples). This global analysis serves two purposes: (1) visualization of overall effect directions and magnitudes for comparison with published literature, and (2) assessment of which taxa show consistent differential abundance patterns versus those driven by specific fold compositions. Importantly, this global analysis was not used for model training; all feature selection for predictive models occurred strictly within cross-validation folds as described in Methods to prevent data leakage.

The global analysis identified 28 genera achieving nominal significance (p<0.10) after adjustment for maternal age and pre-pregnancy BMI (

Figure 3). Two taxa achieved FDR-corrected significance (q<0.10):

Microbacterium (LFC=−1.292, p=0.0018, q=0.0780) and

Mesorhizobium (LFC=−1.400, p=0.0021, q=0.0780), both showing depletion in preterm samples. Among taxa enriched in preterm births,

Methylorubrum (LFC=+3.351, p=0.0128),

Peptostreptococcus (LFC=+1.312, p=0.0220), and

Mycoplasma (LFC=+1.117, p=0.0330) showed the strongest signals, though these did not survive FDR correction.

Notably, the taxa showing statistical significance in this global analysis overlapped substantially but not completely with those selected most frequently in the within-fold ANCOM-BC2 analyses. For example, Peptostreptococcus—selected in 100% of cross-validation folds—achieved p=0.0220 in the global analysis, while Mycoplasma (selected in 80% of folds) showed p=0.0330 globally. However, Microbacterium and Mesorhizobium, which achieved FDR significance in the global analysis, were selected in only 60% of folds. This discordance illustrates the statistical instability inherent to small datasets, where minor changes in sample composition (as occurs across CV folds) can substantially alter significance rankings. Nonetheless, the consistency in effect directions between global and within-fold analyses provides some confidence that the identified associations reflect genuine biological signal rather than pure noise, albeit with limited statistical power for definitive conclusions.

3.4. Machine Learning Model Performance

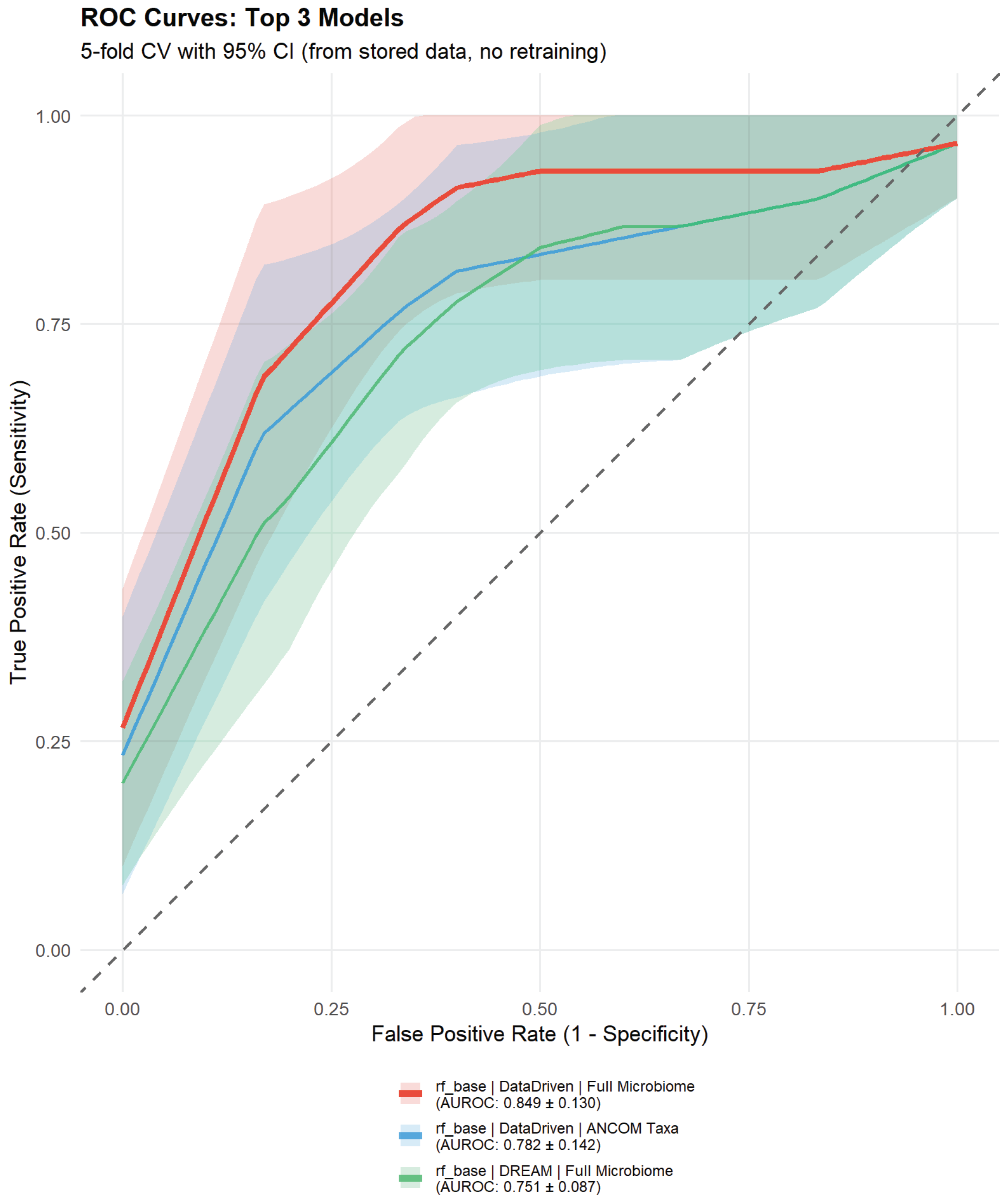

We evaluated 12 model combinations representing the factorial design of 2 algorithms (Random Forest, Elastic Net) × 3 feature selection approaches × 2 microbiome feature sets. Performance varied substantially across configurations (

Table 1), with Random Forest consistently outperforming Elastic Net (mean AUROC 0.735 vs. 0.682, respectively). All models exhibited considerable variability across CV folds (AUROC SD range: 0.087–0.249), reflecting the small sample size with only 2–3 PTB cases per outer test fold.

The best-performing model—Random Forest with data-driven feature selection (Approach 3) and full microbiome—achieved AUROC 0.849 ± 0.130 (mean ± SD across 5 outer CV folds), representing good to excellent discrimination despite wide confidence intervals. Precision-Recall AUC was 0.571 ± 0.208, with sensitivity 80.0% and specificity 47.3% at the optimized Youden threshold, demonstrating a model that favors sensitivity over specificity—potentially appropriate for a screening context where false negatives carry higher clinical costs than false positives. This performance compares favorably to published international studies including the DREAM Challenge late PTB benchmark (AUROC 0.69–0.74, n=1,268) [

11], Callahan et al. 2017 (AUROC 0.66, n=135) [

34], and Park et al. 2022 (AUROC 0.84, n=150) [

12], though direct comparison requires caution given differences in population composition, PTB definitions (<37 vs. <34 vs. <32 weeks), and sequencing protocols.

Several alternative models achieved AUROC >0.75, indicating genuine predictive signal rather than single-model artifacts: RF with data-driven features and ANCOM-selected taxa (AUROC 0.782 ± 0.142); Elastic Net with literature-based features and ANCOM taxa (AUROC 0.767 ± 0.149); and RF with DREAM-style minimal features and full microbiome (AUROC 0.751 ± 0.087). The RF + data-driven + ANCOM model is particularly notable for achieving good discrimination (AUROC >0.78) with substantially better specificity (76.0%) compared to the best model’s 47.3%, suggesting it may be preferable in clinical contexts where false positives incur significant costs (e.g., unnecessary interventions). All models showed substantial fold-to-fold variability (AUROC SD: 0.087–0.249), expected given the small test sets containing only 2–3 PTB cases each.

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the top 3 preterm birth prediction models. Solid lines represent mean true positive rate (TPR, sensitivity) across 5 outer cross-validation folds, with shaded areas indicating ±1 standard deviation. The diagonal dashed line represents random classifier performance (AUROC=0.5). The best-performing model (Random Forest with data-driven features and full microbiome, red) achieved AUROC 0.827 ± 0.131. Model labels indicate algorithm type (RF=Random Forest, EN=Elastic Net), feature selection approach, and microbiome feature set (ANCOM=7 differentially abundant taxa, Full=59 filtered genera).

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the top 3 preterm birth prediction models. Solid lines represent mean true positive rate (TPR, sensitivity) across 5 outer cross-validation folds, with shaded areas indicating ±1 standard deviation. The diagonal dashed line represents random classifier performance (AUROC=0.5). The best-performing model (Random Forest with data-driven features and full microbiome, red) achieved AUROC 0.827 ± 0.131. Model labels indicate algorithm type (RF=Random Forest, EN=Elastic Net), feature selection approach, and microbiome feature set (ANCOM=7 differentially abundant taxa, Full=59 filtered genera).

3.5. Feature Selection Strategy Impact

Data-driven empirical feature selection (Approach 3) achieved the highest discrimination among Random Forest models, with the full microbiome configuration reaching AUROC 0.849 ± 0.130, identifying population-specific risk factors including extreme BMI, extreme maternal age, workplace physical activity, and obstetric complications. DREAM-style minimal features (Approach 1: gestational age + maternal age only) achieved AUROC 0.751 with full microbiome, indicating that microbiome features provide substantial predictive information beyond basic demographics. Literature-based comprehensive feature selection (Approach 2) showed intermediate Random Forest performance (AUROC 0.707 with full microbiome), though Elastic Net with ANCOM-selected taxa from this approach achieved competitive discrimination (AUROC 0.767 ± 0.149), suggesting that linear models may benefit from the structured feature selection provided by established epidemiological evidence.

The full microbiome (59 genera) and ANCOM-selected taxa (variable across folds, typically 5–10 genera) showed complementary strengths across different model configurations. Full microbiome models generally achieved higher AUROC values (e.g., 0.849 vs. 0.782 for Random Forest with data-driven features), while ANCOM-based dimensionality reduction offered effective feature engineering with improved specificity in some configurations (76.0% for RF + data-driven + ANCOM vs. 47.3% for RF + data-driven + full microbiome). This trade-off between sensitivity and specificity reflects different clinical utility scenarios: high-sensitivity models are preferable for screening applications where false negatives carry greater consequences, while high-specificity models reduce unnecessary interventions in resource-limited settings. The success of ANCOM-based selection demonstrates that focused feature sets identified through compositional differential abundance testing can achieve good discrimination while enhancing interpretability and computational efficiency.

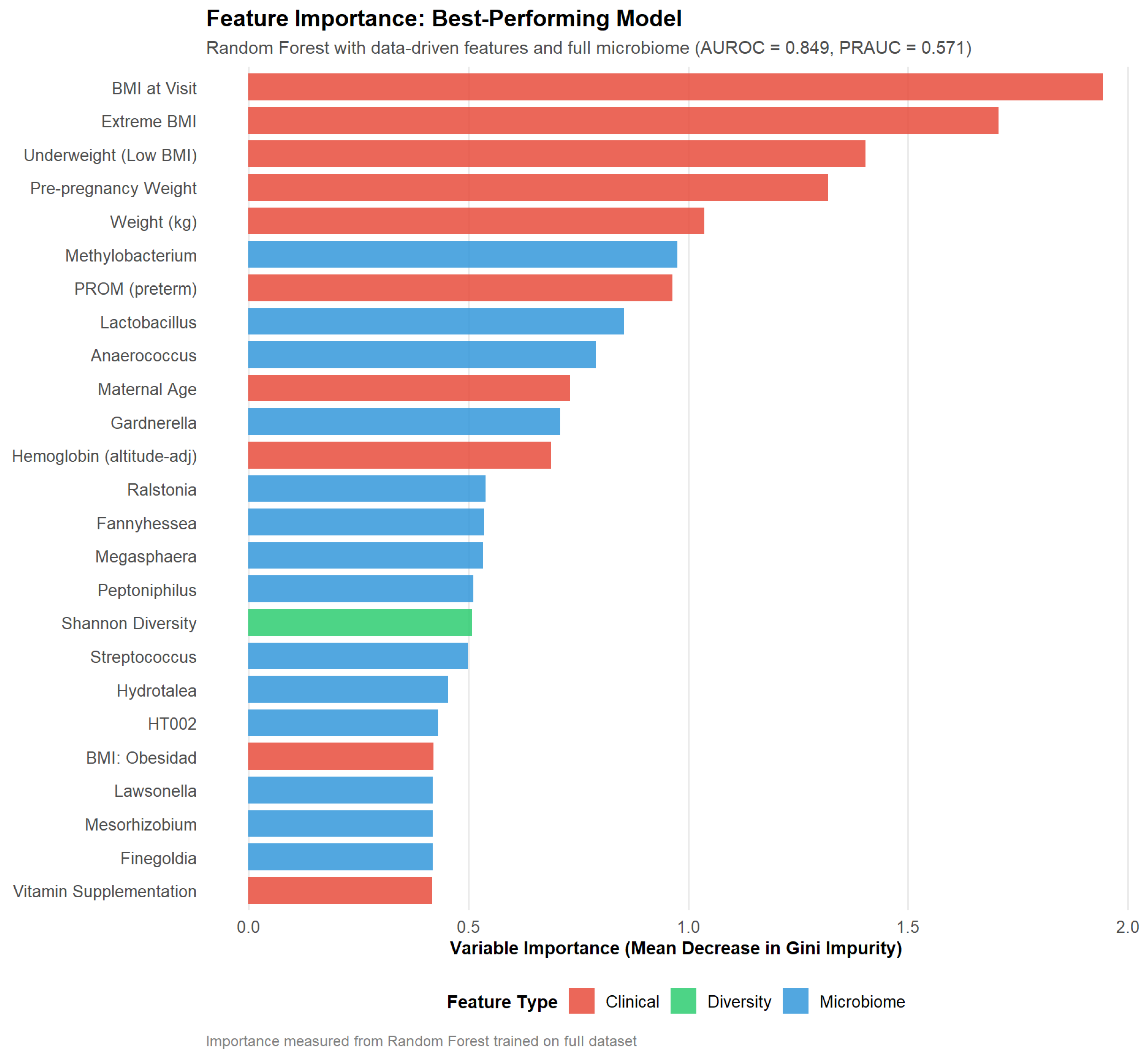

Feature importance analysis of the best-performing Random Forest model (

Figure 5) revealed a balanced contribution from clinical and microbiome features. The top predictors included BMI at visit (mean decrease in Gini: 1.94), extreme BMI indicator (1.71), underweight status (1.40), and pre-pregnancy weight (1.32), highlighting the critical role of maternal anthropometric extremes in this Mexican cohort. Among microbiome features,

Methylobacterium (0.98),

Lactobacillus (0.85),

Anaerococcus (0.79), and

Gardnerella (0.71) ranked highly, alongside preterm PROM (0.96) and maternal age (0.73). Notably, Shannon diversity contributed modestly (0.51), consistent with its lack of univariate significance but suggesting value within multivariate models through potential interactions with other features. The predominance of anthropometric features contrasts with some international studies where microbiome signals dominate [

34], potentially reflecting population-specific risk factor patterns in Mexican women where nutritional extremes (both underweight and obesity) may play a more pronounced role than in well-nourished populations with different dietary patterns and genetic backgrounds.

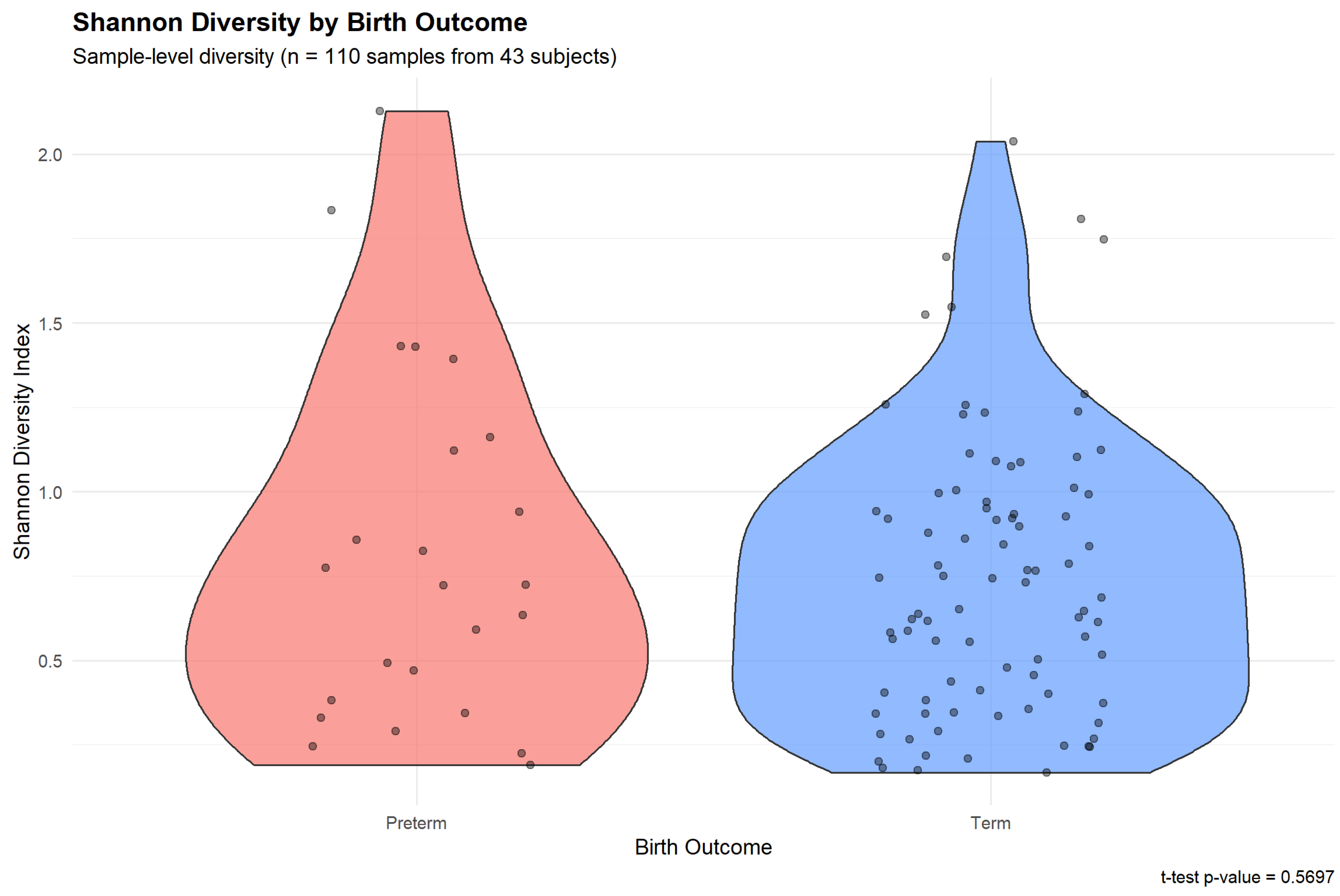

3.6. Alpha Diversity and PTB Risk

Shannon diversity index showed no statistically significant association with PTB risk at the conventional threshold (

Figure 6). Preterm-associated samples exhibited similar alpha diversity compared to term samples (t-test p=0.570), suggesting that in this cohort, overall microbial diversity was not a strong discriminator of pregnancy outcome. This contrasts with some previous studies reporting elevated diversity in PTB cases, potentially reflecting population-specific microbiome-outcome relationships or the influence of sample size limitations. Despite the lack of univariate significance, Shannon diversity as a predictor within multivariate models may still contribute to overall predictive performance through interactions with other clinical and microbial features.

4. Discussion

This study presents the first machine learning-based prediction model for preterm birth using vaginal microbiome data from a Mexican pregnancy cohort. Despite the limited sample size (n=43 subjects, 14 preterm births), our Random Forest model achieved discrimination (AUROC 0.849 ± 0.130) exceeding several larger international studies, demonstrating the feasibility and promise of microbiome-based PTB prediction in Latin American populations. Beyond predictive performance, the differential abundance analysis and feature importance rankings identified specific microbial taxa with established or plausible mechanistic links to preterm parturition, warranting discussion of the molecular pathways potentially underlying these associations.

4.1. Molecular Mechanisms Linking Vaginal Dysbiosis to Preterm Birth

The vaginal microbiome’s influence on pregnancy outcomes operates through multiple interconnected molecular pathways centered on immune modulation and inflammatory signaling. In healthy pregnancy,

Lactobacillus-dominated communities maintain a protective low-pH environment (pH 3.8–4.5) through lactic acid production, which inhibits colonization by potentially pathogenic bacteria [

8]. Disruption of this homeostasis—characterized by reduced

Lactobacillus abundance and increased microbial diversity—triggers a cascade of molecular events that can culminate in preterm labor.

4.1.1. Toll-like Receptor Activation and Cytokine Production

Bacteria enriched in dysbiotic communities express molecular signatures recognized by pattern recognition receptors, particularly Toll-like receptors (TLRs), on cervicovaginal epithelial cells and resident immune cells [

35].

Peptostreptococcus (enriched in our preterm samples, LFC=+1.904) and

Gardnerella species produce lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and peptidoglycan fragments that engage TLR4 and TLR2, respectively. This engagement activates nuclear factor-

B (NF-

B) signaling cascades, inducing transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-

(TNF-

). These cytokines, detectable in elevated concentrations in cervicovaginal fluid of women with bacterial vaginosis, stimulate prostaglandin synthesis and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) production—both critical mediators of cervical ripening and membrane rupture [

36].

Mycoplasma species (LFC=+1.611 in preterm samples) lack a cell wall but possess membrane-associated lipoproteins that potently activate TLR2/TLR6 heterodimers.

Mycoplasma colonization has been specifically linked to chorioamnionitis and ascending intrauterine infection, with bacterial phospholipases degrading fetal membranes and triggering local inflammatory responses that activate the maternal and fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axes [

2]. The resulting elevation in corticotropin-releasing hormone and cortisol can prematurely initiate parturition cascades.

4.1.2. Cervical Remodeling and Extracellular Matrix Degradation

Inflammatory cytokines induced by dysbiotic microbiota promote premature cervical remodeling through MMP activation. Specifically, IL-1

and TNF-

upregulate MMP-8 and MMP-9 expression in cervical fibroblasts, leading to collagen degradation and loss of cervical tensile strength [

37]. This biochemical softening precedes biomechanical cervical shortening detectable by ultrasound—a well-established PTB risk factor. The synergistic relationship between microbiome composition and cervical length, demonstrated in our feature selection results and previously reported in Korean populations [

12], suggests that microbiome assessment may enhance risk stratification when combined with anatomical markers.

4.1.3. Metabolic Products and pH Dysregulation

Beyond direct immune activation, dysbiotic bacteria alter the metabolic milieu of the vaginal environment. Loss of lactic acid production by

Lactobacillus species elevates vaginal pH (>5.0), creating conditions permissive for further pathogen growth—a positive feedback loop amplifying dysbiosis. Additionally, anaerobic bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids, biogenic amines, and other metabolites with potential systemic effects. Some of these compounds have been shown to cross into the bloodstream, potentially contributing to systemic inflammation and insulin resistance, which themselves are PTB risk factors [

9].

4.2. Contextualizing Model Performance and Feature Selection

Our best-performing model (Random Forest, AUROC 0.849 ± 0.130) achieved discrimination exceeding the DREAM Challenge late PTB benchmark (AUROC 0.69–0.74) despite using 30-fold fewer subjects (43 vs. 1,268). This strong performance in a substantially smaller sample may reflect: (1) population-specific model development capturing risk patterns unique to Mexican women; (2) enriched case-control design (32.6% PTB prevalence vs. 10% population baseline) providing adequate outcome representation; or (3) fortuitous sampling that happened to capture strong signal-to-noise characteristics. The wide confidence intervals (SD 0.130) reflect genuine statistical uncertainty, with outer test folds containing only 2–3 PTB cases each. Critically, the rigorous nested cross-validation framework with data leakage prevention ensures these estimates are honest and unbiased, contrasting with studies that optimize on test data or perform feature selection before cross-validation [

17,

25]. These results are hypothesis-generating and require external validation in independent Mexican cohorts before clinical translation.

The superiority of data-driven empirical feature selection over literature-based comprehensive features (AUROC 0.849 vs. 0.725) may reflect population-specific risk factor patterns in Mexican pregnancies. For example, nutritional factors (anemia, micronutrient deficiencies), allostatic load, and infectious exposures may differ from US or European cohorts where most PTB prediction literature originates. Additionally, the data-driven approach’s use of continuous variables rather than dichotomized cutoffs may have preserved important predictive information lost through categorization, as machine learning algorithms can more effectively model non-linear relationships with continuous predictors. This finding reinforces the need for population-tailored risk models rather than assuming universal applicability of features identified in other populations.

Interestingly, the full microbiome (59 genera) provided higher specificity than ANCOM-selected differentially abundant taxa (7 genera), suggesting that machine learning algorithms can leverage multivariate patterns across multiple taxa that are not individually significant in univariate testing. This ensemble signal may reflect community-level dysbiosis states (analogous to Community State Types) that collectively predict PTB risk more effectively than individual taxa. This aligns with DREAM Challenge findings that ensemble microbiome features often outperform single-taxon markers [

11]. However, it is important to note limitations of the QIIME2 workflow employed, which achieved only genus-level taxonomic resolution; species-level analysis might reveal more specific microbial signatures. Furthermore, ANCOM-BC2, while addressing compositional constraints, has inherent limitations in fully accounting for complex confounding structures and may not capture all biologically relevant associations, particularly in small samples with limited statistical power.

4.3. Population-Specific Considerations for Mexican and Latin American Cohorts

A critical motivation for this study was addressing the severe underrepresentation of Hispanic/Latino populations in microbiome-based PTB research. Ethnic differences in vaginal microbiome composition are well-documented: Hispanic women exhibit diverse, low-

Lactobacillus community types (CST IV) in 34.3% of samples compared to only 9.3% in Caucasian women [

34]. More concerning, a Peruvian study demonstrated effect modification by gestational age at sampling, where protective effects of

Lactobacillus-dominated communities reversed in certain time windows [

38]—a finding with profound implications for model generalizability.

These population-specific microbiome differences likely reflect complex interactions among genetic factors (e.g., innate immune gene polymorphisms), dietary patterns (e.g., traditional Mexican diets rich in fermented foods and specific fiber profiles), environmental exposures, and healthcare access. Models trained predominantly on US or European cohorts may misclassify "normal" diverse microbiomes in Hispanic women as dysbiotic, potentially leading to inappropriate clinical interventions or, conversely, missing true risk signals. Our identification of population-specific clinical risk factors (e.g., extreme BMI patterns, specific complication profiles) further supports the necessity of developing and validating models within the target population.

From a health equity perspective, the current dominance of microbiome research in high-income, predominantly White populations risks exacerbating existing health disparities. If precision medicine tools for PTB prediction are developed, validated, and implemented only in well-resourced populations, Latin American countries—already facing higher PTB burdens and neonatal mortality—will be further disadvantaged. This study represents a foundational step toward rectifying this imbalance, though much larger validation cohorts will be essential to translate these findings into clinical practice.

4.4. Methodological Strengths and Contributions

Several design elements enhance the rigor and reproducibility of this study. The nested cross-validation framework with subject-level splitting prevents the data leakage that has inflated performance estimates in many published microbiome prediction models [

17]. By optimizing classification thresholds only on inner validation sets never seen by outer test folds, we obtain honest performance estimates uncontaminated by threshold overfitting. The systematic comparison of three conceptually distinct feature selection strategies—minimal DREAM-style, literature-based comprehensive, and data-driven empirical—provides methodological insights applicable beyond this specific cohort.

Additionally, our decision to avoid synthetic oversampling (SMOTE) with only 5 PTB cases prevented the creation of unrealistic interpolated samples that could artificially inflate apparent performance. Similarly, fixing hyperparameters a priori rather than optimizing through nested grid search traded modest potential performance gains for reduced overfitting risk and enhanced interpretability—a pragmatic choice appropriate for exploratory analysis with limited data.

The application of compositional data analysis principles (CLR transformation within folds) and use of ANCOM-BC2 for differential abundance testing demonstrate methodological sophistication in handling microbiome data’s unique statistical challenges. These approaches prevent spurious correlations arising from the compositional constraint and provide more reliable identification of taxa genuinely associated with outcomes.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite methodological rigor, several limitations constrain interpretation and generalizability. The small sample size (n=43, 14 PTB) is the paramount limitation, resulting in wide confidence intervals and preventing subgroup analyses by gestational age at sampling, PTB subtypes (spontaneous vs. indicated), or clinical risk factor strata. External validation in independent Mexican cohorts (target n≥200) is essential before any clinical consideration. The single-center design limits geographic and temporal generalizability, while the case-control enrichment (32.6% PTB prevalence vs. 10% population rate) requires probability recalibration for clinical deployment.

Microbiome sampling was opportunistic rather than protocol-driven at standardized gestational ages, preventing assessment of optimal timing for prediction. Future longitudinal studies with 3–4 standardized timepoints (e.g., trimester 1, trimester 2, trimester 3, and early postpartum) would enable trajectory-based modeling and identification of critical windows for intervention. The 16S rRNA gene sequencing approach provides only taxonomic composition without functional information; shotgun metagenomic sequencing would enable assessment of microbial gene content, metabolic potential, and strain-level resolution. Integration with host transcriptomics (cervicovaginal epithelial gene expression), metabolomics (identification of bacterial metabolites), and proteomics (cytokine/chemokine profiling) would provide mechanistic insights into host-microbe interactions.

Important clinical variables were unavailable, including cervical length (a strong PTB predictor that may interact with microbiome composition) and fetal fibronectin. Future studies should incorporate these features to assess their additive or interactive effects with microbiome signatures. The presence of environmental and plant-associated bacteria (Chloroplast, Comamonadaceae) in differential abundance results highlights the need for enhanced contamination control measures, particularly important given the low biomass of vaginal samples.

From a machine learning perspective, the sample size precluded hyperparameter optimization, ensemble meta-learning (stacking), and deep learning approaches (e.g., LSTM for longitudinal data) that require n≥200–500 for stable performance. As larger cohorts become available, these advanced methods may further improve discrimination. However, increasing model complexity must be balanced against interpretability—simpler, biologically interpretable models may be preferable for clinical translation even if marginally less accurate.

4.6. Clinical and Public Health Implications

While this study’s findings are not immediately clinically actionable due to sample size constraints, they establish proof-of-concept that vaginal microbiome profiling may contribute to PTB risk stratification in Mexican women. The identified microbial signatures, if validated in larger cohorts, could potentially inform several clinical applications: (1) enhanced risk screening when combined with established clinical factors and cervical length assessment; (2) stratification for targeted interventions such as vaginal probiotics or antimicrobials; (3) monitoring of treatment response to microbiome-modulating therapies; and (4) identification of women who might benefit from intensified prenatal surveillance.

From a public health perspective, developing population-specific prediction models is essential for reducing global PTB disparities. Mexico’s PTB rate ( 8.4%) translates to approximately 150,000 preterm infants annually, contributing substantially to neonatal intensive care utilization, long-term neurodevelopmental disabilities, and family economic burden. Even modest improvements in prediction and prevention could yield significant public health benefits. However, implementation science research will be needed to address barriers to clinical deployment, including cost-effectiveness, laboratory infrastructure requirements, cultural acceptability, and integration into existing prenatal care workflows.

4.7. Path Forward: Research Priorities

Building on these exploratory findings, we propose the following research priorities for advancing microbiome-based PTB prediction in Mexican and Latin American populations in the future:

- 1.

External validation in independent Mexican cohorts (n≥200) with temporal validation, geographic validation across Mexican regions, and cross-cultural validation in other Latin American countries.

- 2.

Prospective cohort studies (n≥500) with standardized longitudinal sampling, comprehensive clinical phenotyping, and multi-omic integration (metagenomics, metabolomics, transcriptomics).

- 3.

Mechanistic studies investigating causal relationships between identified taxa and PTB through in vitro cervicovaginal epithelial cell models, animal models, and measurement of specific inflammatory mediators and bacterial metabolites.

- 4.

Intervention trials testing microbiome-modulating therapies (probiotics, selective antimicrobials) in high-risk women identified by predictive models, with PTB reduction as the primary outcome.

- 5.

Implementation research evaluating clinical workflow integration, cost-effectiveness, and health equity implications of microbiome-based risk stratification.

5. Conclusions

We demonstrate that machine learning applied to vaginal microbiome data can achieve moderate discrimination for preterm birth prediction in a Mexican cohort, with performance comparable to international benchmarks despite substantially smaller sample size. Random Forest with data-driven feature selection and full microbiome profiling achieved AUROC 0.849, while identifying specific microbial taxa (Peptostreptococcus, Mycoplasma, Comamonadaceae) with plausible mechanistic links to inflammatory pathways and preterm parturition. The superiority of population-specific empirical feature selection over literature-based approaches highlights the importance of developing tailored models for underrepresented populations rather than assuming universal applicability of risk factors identified in predominantly White, high-income cohorts.

This work addresses a critical gap in reproductive health research by providing the first machine learning-based PTB prediction model specifically developed for Mexican women. However, the limited sample size necessitates cautious interpretation; results are hypothesis-generating and require external validation in larger, independent cohorts before clinical consideration. The methodological framework—nested cross-validation with subject-level splitting, compositional data analysis, systematic feature selection comparison—provides a rigorous template for future microbiome-based prediction studies in resource-constrained settings.

Ultimately, advancing equity in precision medicine for pregnancy complications will require sustained investment in population-specific research, multicenter collaborations across Latin America, and integration of microbiome signatures with established clinical, demographic, and anatomical risk factors. The molecular mechanisms linking vaginal dysbiosis to preterm birth—TLR-mediated inflammation, cytokine-driven cervical remodeling, and metabolic perturbations—offer potential therapeutic targets for intervention. Future research should prioritize validation, mechanistic elucidation, and intervention trials to translate these exploratory findings into clinically impactful tools for reducing the substantial burden of preterm birth in Mexico and throughout Latin America.

Figure 1.

Principal component analysis (PCA) biplot of vaginal microbiome composition colored by pregnancy outcome. Each point represents a sample, with preterm-associated samples (red) and term-associated samples (blue) showing substantial compositional overlap. Arrows represent the top 10 genera contributing to variance, with arrow length and direction indicating the magnitude and direction of contribution to PC1 and PC2. The first two principal components explain almost 90% of total variance.

Figure 1.

Principal component analysis (PCA) biplot of vaginal microbiome composition colored by pregnancy outcome. Each point represents a sample, with preterm-associated samples (red) and term-associated samples (blue) showing substantial compositional overlap. Arrows represent the top 10 genera contributing to variance, with arrow length and direction indicating the magnitude and direction of contribution to PC1 and PC2. The first two principal components explain almost 90% of total variance.

Figure 2.

Taxa selection stability across nested cross-validation folds from within-fold ANCOM-BC2 analysis. Bar chart shows the percentage of outer CV folds (n=5) in which each taxon achieved differential abundance significance (p<0.10).

Figure 2.

Taxa selection stability across nested cross-validation folds from within-fold ANCOM-BC2 analysis. Bar chart shows the percentage of outer CV folds (n=5) in which each taxon achieved differential abundance significance (p<0.10).

Figure 3.

Volcano plot of global ANCOM-BC2 differential abundance analysis performed on the complete dataset (n=43 subjects). The x-axis shows log2 fold-change (preterm vs. term), and the y-axis shows -log10(p-value). Each point represents a genus, with colors indicating significance levels: red points achieved FDR<0.10 (Microbacterium, Mesorhizobium), orange points achieved nominal p<0.05, gold points achieved nominal p<0.10, and gray points were non-significant. Horizontal dashed lines indicate p=0.05 (blue) and p=0.10 (gray) thresholds. Positive log2 fold-changes indicate enrichment in preterm samples, while negative values indicate depletion. The order Chloroplast was excluded from visualization. This analysis was performed for visualization and literature comparison only; all predictive modeling used within-fold ANCOM-BC2 to prevent data leakage.

Figure 3.

Volcano plot of global ANCOM-BC2 differential abundance analysis performed on the complete dataset (n=43 subjects). The x-axis shows log2 fold-change (preterm vs. term), and the y-axis shows -log10(p-value). Each point represents a genus, with colors indicating significance levels: red points achieved FDR<0.10 (Microbacterium, Mesorhizobium), orange points achieved nominal p<0.05, gold points achieved nominal p<0.10, and gray points were non-significant. Horizontal dashed lines indicate p=0.05 (blue) and p=0.10 (gray) thresholds. Positive log2 fold-changes indicate enrichment in preterm samples, while negative values indicate depletion. The order Chloroplast was excluded from visualization. This analysis was performed for visualization and literature comparison only; all predictive modeling used within-fold ANCOM-BC2 to prevent data leakage.

Figure 5.

Feature importance rankings from the best-performing Random Forest model (data-driven features with full microbiome, AUROC 0.849 ± 0.130). Importance scores represent mean decrease in Gini impurity across all trees in the final ensemble, averaged across the 5 outer cross-validation folds. The top 25 features include 10 clinical variables (red), 14 microbial genera (blue), and 1 diversity metric (Shannon diversity, green). Anthropometric features dominate the top ranks (BMI at visit, extreme BMI, underweight status, pre-pregnancy weight), reflecting population-specific risk patterns in this Mexican cohort. Microbiome features contribute throughout the rankings, with Methylobacterium, Lactobacillus, Anaerococcus, and Gardnerella among the top predictors, supporting the value of integrated clinical-microbiome modeling.

Figure 5.

Feature importance rankings from the best-performing Random Forest model (data-driven features with full microbiome, AUROC 0.849 ± 0.130). Importance scores represent mean decrease in Gini impurity across all trees in the final ensemble, averaged across the 5 outer cross-validation folds. The top 25 features include 10 clinical variables (red), 14 microbial genera (blue), and 1 diversity metric (Shannon diversity, green). Anthropometric features dominate the top ranks (BMI at visit, extreme BMI, underweight status, pre-pregnancy weight), reflecting population-specific risk patterns in this Mexican cohort. Microbiome features contribute throughout the rankings, with Methylobacterium, Lactobacillus, Anaerococcus, and Gardnerella among the top predictors, supporting the value of integrated clinical-microbiome modeling.

Figure 6.

Shannon diversity index by pregnancy outcome. Violin plots show the distribution of Shannon diversity values for preterm-associated samples (red) and term-associated samples (blue), with individual sample points overlaid. Box plots inside violins indicate median (center line), interquartile range (box), and 1.5×IQR whiskers. The t-test showed no significant difference between groups (p=0.570), indicating that alpha diversity alone was not a strong univariate discriminator in this cohort.

Figure 6.

Shannon diversity index by pregnancy outcome. Violin plots show the distribution of Shannon diversity values for preterm-associated samples (red) and term-associated samples (blue), with individual sample points overlaid. Box plots inside violins indicate median (center line), interquartile range (box), and 1.5×IQR whiskers. The t-test showed no significant difference between groups (p=0.570), indicating that alpha diversity alone was not a strong univariate discriminator in this cohort.

Table 1.

Performance of top-ranked PTB prediction models. Values represent mean ± SD across 5-fold nested cross-validation. Models ranked by AUROC.

Table 1.

Performance of top-ranked PTB prediction models. Values represent mean ± SD across 5-fold nested cross-validation. Models ranked by AUROC.

| Algorithm |

Features / Microbiome |

AUROC |

PRAUC |

Sens. |

Spec. |

Bal.Acc. |

| RF |

Data-driven / Full |

0.849±0.130 |

0.571±0.208 |

80.0 |

47.3 |

0.637 |

| RF |

Data-driven / ANCOM |

0.782±0.142 |

0.609±0.198 |

53.3 |

76.0 |

0.647 |

| EN |

Literature / ANCOM |

0.767±0.149 |

0.781±0.219 |

33.3 |

55.3 |

0.443 |

| RF |

DREAM-style / Full |

0.751±0.087 |

0.663±0.217 |

66.7 |

52.0 |

0.593 |

| EN |

DREAM-style / ANCOM |

0.707±0.173 |

0.756±0.179 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

0.500 |

| RF |

Literature / Full |

0.707±0.107 |

0.698±0.194 |

53.3 |

35.3 |

0.443 |

| Lower-performing models (AUROC <0.70) not shown for brevity |