Introduction: Waves of Innovation

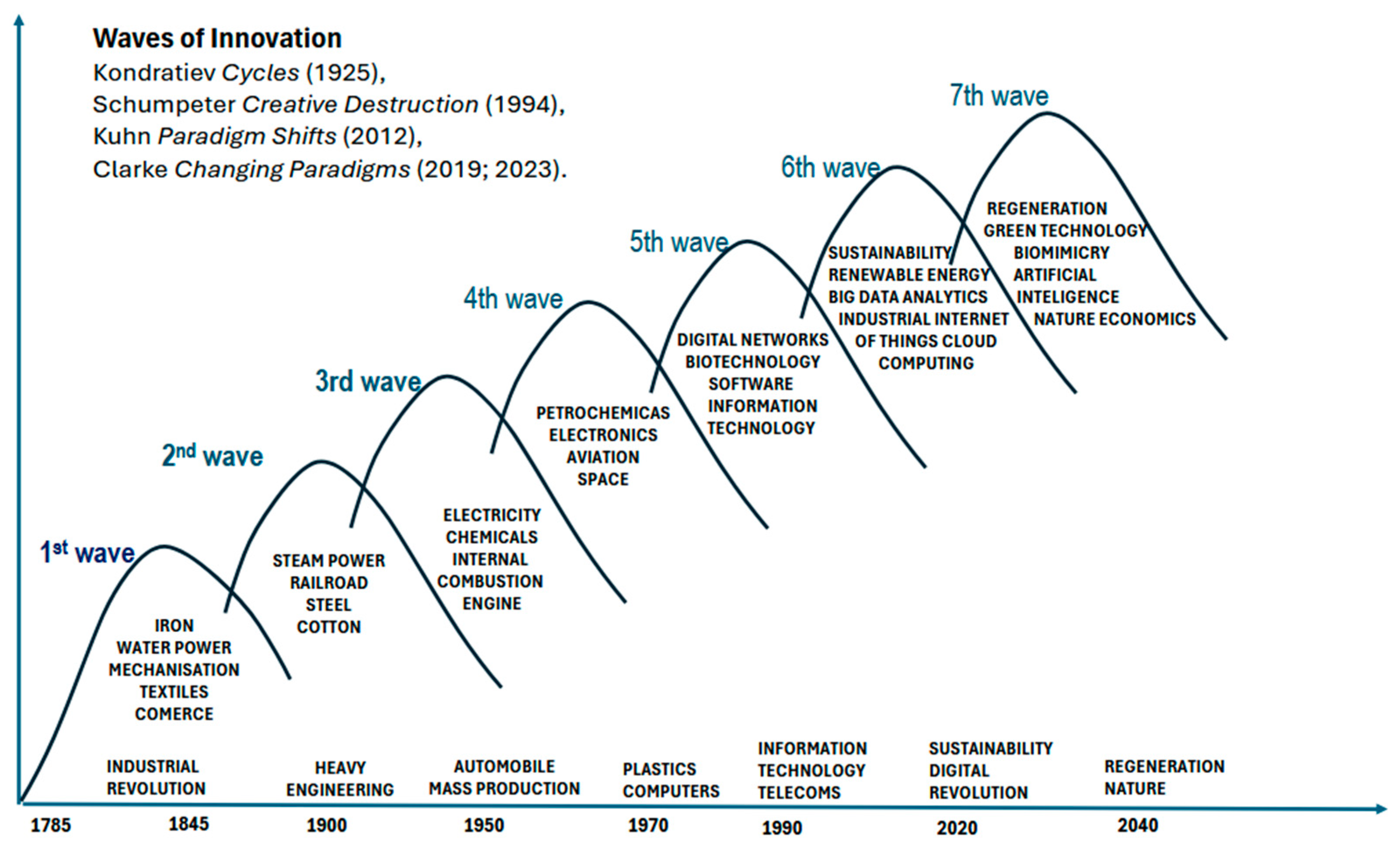

The transformation of the modern world over the last two centuries may be interpreted as a series of waves of innovation, leading from technological exploitation towards sustainability. Whatever the future holds it will be defined by continual adaptation, perpetual innovation and the search for new potential (Arthur et al 1997; Andersen and Tushman 1990). Creative waves of destruction punctuate the stages of innovation with successive dramatic new technologies that build upon and supersede each other. Among the driving technologies of the current waves of innovation are:

efficiency technologies (for example cloud technologies),

connectivity technologies (for example 5G technologies and the Internet of Things),

trust disintermediation technologies (for example blockchain), and

automation technologies (for example big data and artificial intelligence).

As in the past, profound technological change has brought dramatic structural change in the economy and among corporations “change and not stability is the permanent feature defining these very important institutions of capitalism…Turbulence is the future, just as it was in the past of these giant firms…Economies, firms and social actors are part of a sweeping process of change…And this is both the condition and the opportunity for progress.” (Louca and Medonca 2002:840; Chandler 1977; 1990).

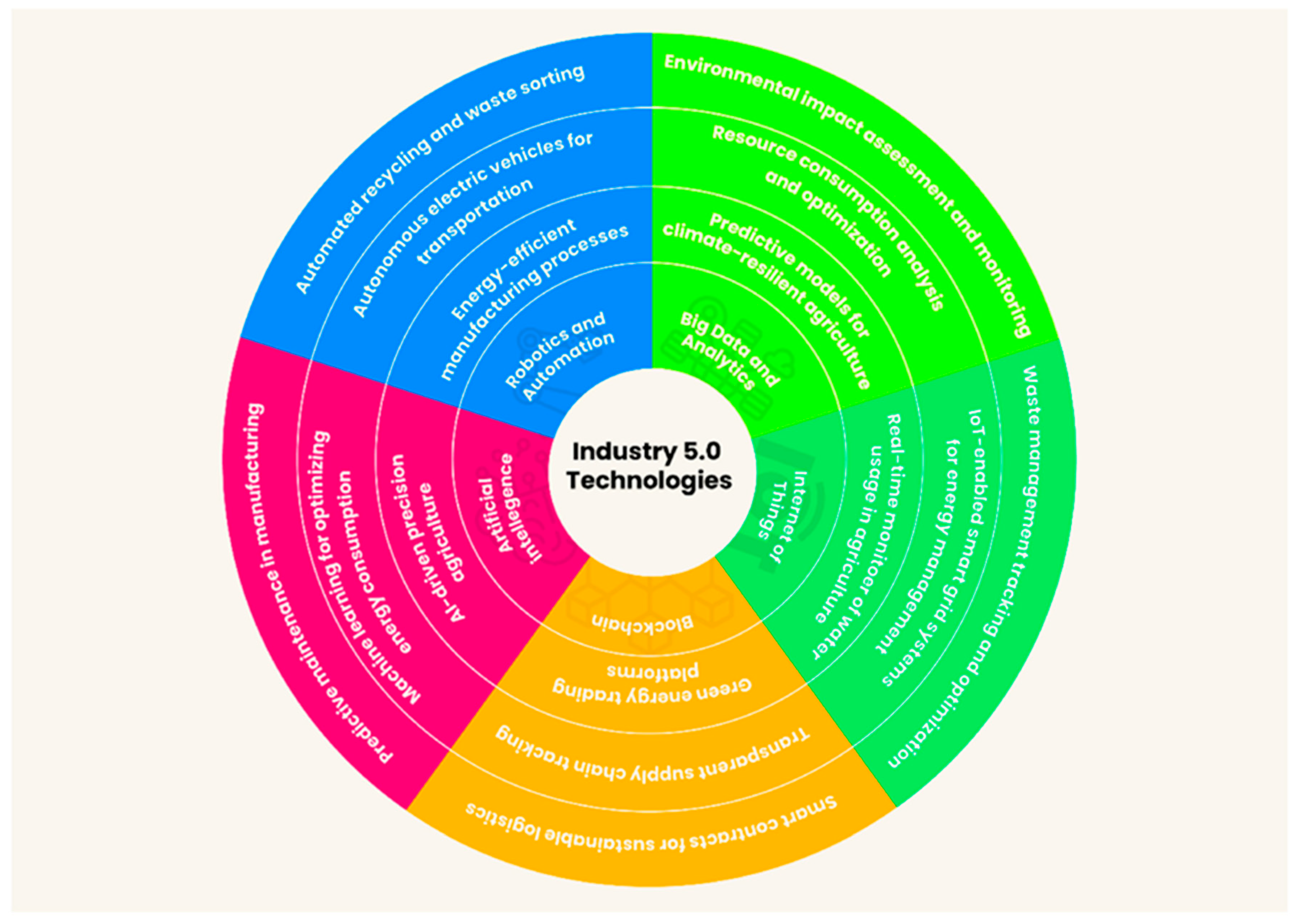

How these technologies will transform industries and economies or serve to create new industries and institutions is presently unfolding (Lanzolla et al 2018; Schwab and Davis 2018). The compounding profound revolutions in digital technologies have proved the defining social and economic achievements of the late 20th century and early 21st century, and with the inflection point of the transformative impact of artificial intelligence, this remaking of the industrial world is rapidly accelerating (Zimmerman et al 2025). The combination of the foundational technologies of Industry 4.0 in AI, Big Data, IOT, Sensors, Robots, and Blockchain, combined with technologies such as Cloud computing, Augmented Reality (AR) Virtual Reality (VR), Additive Manufacturing (#D Printing), Cyber systems, Nanotechnology, Quantum Computing, Natural Language Processing (NLP).

A host of other new technologies presents the prospect of a fully automated world of Industry 5.0 where human work is fully integrated with advanced technologies (Rashid, and Kausik 2024). A new sustainability technological frontier is now emerging as Industry 5.0 promises a symbiotic relationship between advanced technologies and sustainability practices, with additive manufacturing promoting the circular economy, with innovations in renewable energy, waste management and materials science. Balancing enhanced productivity with environmental and social responsibilities (Rame, Purwanto and Sudarno (2024); Ghobakhloo et al (2022). In this new environmentally and ecologically conscious world, instead of Nature being exploited and degraded, Nature will be sustained and regenerated (

Table 1).

This is the further profound and necessary transformation of techno-economic paradigms on the horizon as the high-tech world confronts the natural world: the transformation towards sustainability and on to regeneration of the earth’s natural resources. This transformation will be essential for the future of life on this planet.

Technological Transformation, Creative Destruction, and Sustainability

The technological change that has transformed the world in the last two centuries has been facilitated by new modes of finance and governance, engineering, management and organization. Recurrent waves of innovation have delivered mechanization, steam power, railroads, steel, electricity, the internal combustion engine, petrochemicals, electronics, aviation, digital networks, information technology, biotechnology, big data, the industrial internet of things, and cloud computing. However, the next fundamental waves of innovation will be typified by environmental science, including biotechnology, renewable energy, green technology and regenerative industries, and this will form successive revolutions in sustainability and regeneration (

Figure 1).

Historically the Russian economist Krondratiev (1925) saw a pattern to these technological transformations typifying them as momentous waves of innovation impacting on economies and societies with resulting long cycles of expansion, stagnation, and recession, followed by further creative innovation in a new technological wave. In turn the Austrian/American economist Schumpeter dramatically characterized these waves of innovation as “the perennial gale of creative destruction” (1975: 84). Clusters of innovation create new and discontinuous leading-edge sectors in the world economy, driving surges of economic growth. Over time further innovation restarts the whole cycle with new discontinuous innovation. Radical technological change is an enabling agent for many other social, economic and environmental changes, allowing the pursuit of new opportunities, new social and economic organizations, new products and processes, and modes of consumption. Since the origin of economics technological change has proved the subject of endless fascination to economists, including in the early chapters of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776).

The concept of paradigms relates back to the ancient Greek paradeigma meaning a model or framework. Most technological change is caused by progressive modifications of existing technologies by inventive minds, but radical transformation invariably is an act of genius that brings radical technological transformation and discontinuous change, dramatically altering whole technological systems. Kuhn (2012) referred to these as paradigm shifts – discontinuous change invalidates existing assumptions and transforms the rules of competition. Such systemic changes Freeman (1987) refers to as “changes in techno-economic paradigm.” Systemic changes in technology lead to larger scale revolutionary changes:

“The ‘creative gales of destruction’ that are at the heart of Schumpeter’s long wave theory… represent those new technological systems which have such pervasive effects on the economy as a whole that they change the ‘style’ of production and management throughout the system. The introduction of electric power or steam power or the electronic computer are examples of such deep-going transformations. …Not only does this type of technological change lead to the emergence of a new range of products, services, systems and industries in its own right – it also affects directly or indirectly almost every other branch of the economy… The changes involved go beyond specific product or process technologies and affect the input cost structure and conditions of production and distribution throughout the system” (Freeman 1987:130).

In 2025 the winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences were Jan Mokyr, Philip Aghion, and Peter Howitt who were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in recognition of their work on technological innovation and creative destruction, demonstrating how through innovation, capitalist economies change their industrial structures and identifying “the prerequisites for sustained growth through technological progress..” (Abramitzky, R, and M. Drelichman (2025), Aghion (1990); Aghion et al (2016); Mokyr (1990; 2016).

The concept of changing paradigms goes beyond the technological transformation achieved by advances in digital technology in recent decades, to encompass the dramatic changes that have occurred in terms of globalisation of value chains and cultures, strategic rethinking of business purpose and direction, transformation of organisations and conceptions of stakeholders, and most of all the all-embracing imperatives in a resource constrained world of sustainability and regeneration. These new waves are overwhelming economies and societies, with the objective of sustaining the environment and ecology upon which we all survive (Clarke 2019; Clarke 2023; Clarke, Benn and Edwards 2026; Clarke and Clegg 2000).

The Fifth Digital Wave

Presently we are still experiencing the profound impact of the multiple, rapid waves of innovation created by the rapid, sustained and universal advance of digital networks, software, and information and communication technology systems. It is the digital paradigm that continues to dazzle mankind. Together these technologies have transformed workplaces, homes, cities and whole economies, delivering a globally integrated system. Digital international technological systems are coalescing into intelligent technologies supporting, facilitating and structuring our lives as AI powered smart phones become intimate appendages of our existence, and work increasingly involves the accelerating pace at which we process vast amounts of information:

“Viewed from a Schumpetarian perspective, all manufacturers and suppliers of software and service and business users are engaged in a process of creative destruction on a grand scale to engineer, integrate, and synthesise all of these technologies into a kind of infrastructure to mediate the design, development and production of all products, equipment, and machinery, the trading and exchange of all goods and services, as well as the all-important information processing, communication and decision making activities that are so integral to the way organisations, economic systems, and society operate and are structured” (Estabrooks 1995:x).

Digital technologies fundamentally challenge existing processes, routines, capabilities and structures, and governance and finance by which organisations presently operate, adapt and innovate (George and Lin 2017; Delemarle and Larédo 2014; Sovacool and Hess 2017: Ford 2015). Digital technologies stimulate a higher rate of both technological and business model innovation, with design thinking and multi-disciplinary teams and networks; moving from producer innovation to a more user and open collaborative innovation (Markides and Sosa 2013; Baldwin and Von Hippel 2011; Chesbrough and Bogers 2014; Clarke 2019; Logue 2019). A similar transformation is taking place in governance and finance.

New product technology platforms and open-source software have reduced the technological barriers and risks to product innovation. The evolution of big data combined with powerful data algorithms creates the capacity to discern patterns in complexity integral to the creation of new knowledge. Big data tools are being applied across all scientific disciplines and industries and businesses (Daugherty and Wilson 2018; Lester 2018; Clarke and Lee 2018).

Continuous advances in technology present rich possibilities for new pathologies of globalisation, intensifying automation and the powerfully disruptive impact of the digital revolution (MGI 2016; OECD 2017b; Reuver et al 2017). Though now underway for half a century, digital transformation has entered a new phase built on high speed and mobile connectivity: an era of cloud computing and rise of the platform economy (Kenny and Zysman 2016). Cloud computing releases digital platforms, big data, and computational-intensive automation, which enable the re-conception of firms, institutions and markets (MGI 2017). As the OECD (2017b) comments, “Underpinned by information and communication technology (ICT) investment, business dynamism, entrepreneurship and data-driven innovation (DDI), traditional goods and services are increasingly enhanced by digital technology, new digital products and business models emerge, and more and more services are being traded or delivered over online platforms.”

The World Wide Web and social media are providing resources for transforming identities, roles, organisations, communities and economies. However, as we enter the mature stages of the wave of digital technology and digital disruption with big data, the Industrial Internet of Things and cloud computing, there are new and demanding technological challenges to come, regarding the environmental sustainability of industrial civilisation, and how we can regenerate the ecology upon which all life on earth depends.

As Brundtland conceived in the first international sustainability report: “Technology will continue to change the social, cultural, and economic fabric of nations and the world community. With careful management, new and emerging technologies offer enormous opportunities for raising productivity and living standards, for improving health, and for conserving the natural resource base. Many will also bring new hazards, requiring an improved capacity for risk assessment and risk management.” (Brundtland 1987:182)

Planetary Boundaries and Sustainable Development

The overwhelming ambitions of business and technology have to be tempered by the increasing realization that we are reaching the limits of environmental planetary boundaries, and these must not be transgressed if we wish to ensure the survival of humanity and the stability of the planet. The ecological limits of the planet have now a scientific basis in the planetary boundaries framework (Rockström et al 2009). The concept of a “safe operating space for humanity” is based on the best knowledge of the fundamental dynamics of the earth system: the planetary processes that together maintain climate stability and ecological resilience.

As the Lancet Planetary Health-Earth Commission Report on Earth-system Boundaries, Translations, and Transformations insists:

“The health of the planet and its people are at risk. The deterioration of the global commons—ie, the natural systems that support life on Earth—is exacerbating energy, food, and water insecurity, and increasing the risk of disease, disaster, displacement, and conflict” (2024:e813).

The Commission defines safe and just earth system boundaries (ESBs) and assesses minimum access to natural resources required for human dignity and to enable escape from poverty. “We define safe as ensuring the biophysical stability of the Earth system, and our justice principles include minimizing harm, meeting minimum access needs, and redistributing resources and responsibilities to enhance human health and wellbeing” (2024:e813). The Commission conceives of a “safe and just corridor” to minimize significant harm to humanity and ensure earth-system stability. “We define safe as ensuring the biophysical stability of the Earth system, and our justice principles include minimizing harm, meeting minimum access needs, and redistributing resources and responsibilities to enhance human health and wellbeing” (2024:e813).

The Commission defines earth system boundaries (ESBs) for five domains:

biosphere (functional integrity and natural ecosystem area),

climate,

nutrient cycles (phosphorus and nitrogen),

freshwater (surface and groundwater),

aerosols—to reduce the risk of degrading biophysical life-support systems and avoid tipping points.

All of these earth system boundaries have been transgressed to some degree by current industry and technologies and this presents real dangers. The Commission employs the concept of Earth system justice which “seeks to ensure wellbeing and reduce harm within and across generations, nations, and communities, and between humans and other species, through procedural and distributive justice—to assess safe boundaries. Earth-system justice recognises unequal responsibility for, and unequal exposure and vulnerability to, Earth-system changes, and also recognizes unequal capacities to respond and unequal access to resources” (2024:e813).

The Commission considers what is required to return humanity to safety, ensuring access to essential resources, and adequately addressing Earth-system changes and the vulnerabilities of institutions and societies to systematic transformations including:

reducing and reallocating consumption

changing economic systems, technology and governance (2024:e815).

“Environmental degradation has profoundly impacted both human society and ecosystems. The environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) illuminates the intricate relationship between economic growth and environmental decline. However, the recent surge in trade protectionism has heightened global economic uncertainties, posing a severe threat to global environmental sustainability… As income levels rise, the impact of economic growth on environmental degradation initially intensifies before displaying a diminishing trend. Additionally, trade protection manifests as a detriment to improving global environmental quality… In high-income nations, trade protection appears to contribute to mitigating environmental degradation. Conversely, within other income brackets, the stimulating effect of trade protection on environmental pressure is more conspicuous. In other words, trade protectionism exacerbates environmental degradation, particularly affecting lower-income countries, aligning with the concept of pollution havens (Wang et al (2024).

Changing Paradigms

The realization of planetary boundaries and the absolute necessity for sustainable development for the future leads to the inescapable conclusion that every aspect of business must change: business purpose, objectives, strategies, operations, and performance measures (Clarke 2023; 2024; Clarke, Benn and Edwards 2026). As Kuhn in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions would put it:

“… A new basis for the practice of science…scientific revolutions.. The tradition shattering complements to the tradition-bound activity of normal science…”(1966:7)

The American Bar Association Task Force on Sustainable Development outlines the scale of the challenge:

“Sustainability is a framework for decision-making based on promotion of environmental protection, social justice, and economic/financial responsibility at the same time with the overall objective of promoting human well-being for present and future generations… Sustainability is intended to address two significant and related problems – widespread environmental degradation, including climate disruption and large-scale extreme poverty. The root causes of these problems, in turn, are understood to be unsustainable patterns of production and consumption as well as a very large and still growing population” (ABA 2015:1).

The ABA was expansive in defining sustainability involving “complex relationships among economic, social and environmental priorities. This suggests a cross-functional approach …that integrates.. environmental, labour, property, tax, corporate, finance, international trade and risk management.” (ABA 2015:5)

There are now thousands of climate change and policy initiatives led by institutions across the world impressing upon corporations the urgency of the sustainability problem, and the importance of taking action. The existing initiatives vary in their status from company laws to voluntary guidelines, from the United Nations, to national governments, and through civil society. In their scope policies range from limiting greenhouse gas emissions to tackling broader environment risks; and in their ambition from demanding simple disclosure to full explanations of mitigation and divestment strategies. These institutional initiatives have increased in influence and authority as the science and policy base that supports them becomes more profound. Almost all FTSE 100 and Fortune 500 corporations have participated in these various initiatives for some time, while the performance of the companies is open to some question, and the rigour of the new sustainability reporting standards themselves may be questioned, this is part of a scientific revolution (Carney 2015; Monciardini, Mähönen, and Tsagas 2020; Monciardini and Mähönen 2026; Monciardini, Rocca, and Veneziani 2024).

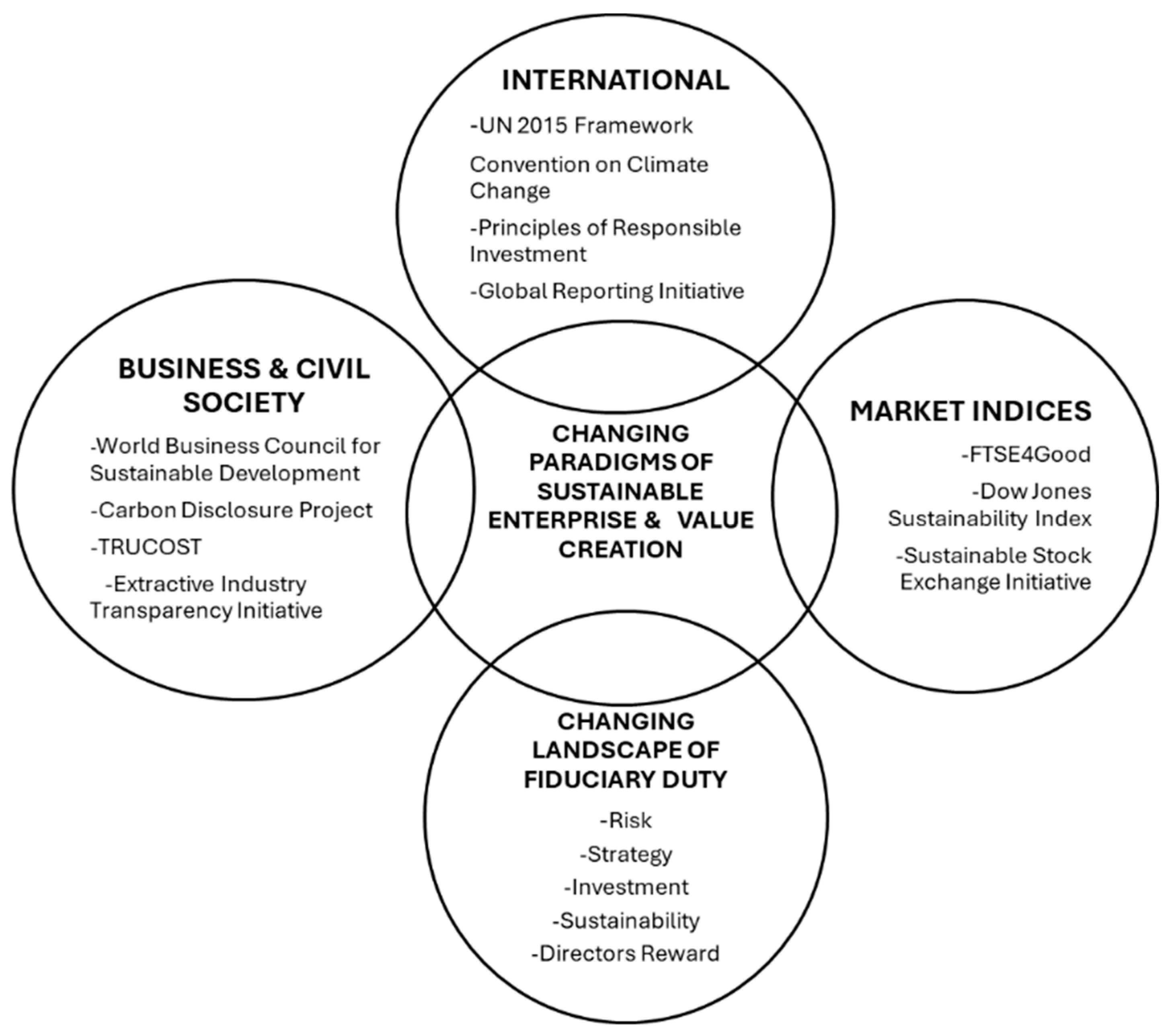

New Business Paradigm

An increasing series of international institutional initiatives are now inspiring, facilitating and guiding the progress of companies towards new conceptualizations of business purpose, strategies and measures of performance. These policy initiatives are increasingly reinforced by market indices which measure the performance of companies according to social and environmental criteria. This effort is endorsed by a wide array of business and society bodies that are researching and disseminating knowledge and practical analytical skills regarding sustainability. This amounts to a changing landscape for the definition and practice of fiduciary duty where risk, strategy and investment are closely calibrated with social and environmental responsibility (

Figure 2).

Net-Zero Commitments of Corporations

The costs of the business transition towards sustainability are considerable, but the costs of inaction would prove infinitely greater and more enduring. Before governments and corporations falter because of the enormous costs involved in emissions reductions necessary to counter climate change, they need to contemplate the catastrophic damage to the environment in doing nothing are much greater still (MGI 2022). It is clear that the pace of change towards a sustainable economy will only continue to accelerate if there is consistent and sustained pressure upon governments and corporations from all stakeholders.

Coalitions of institutions have sponsored initiatives for collaborative business action. Science Based Targets (2021) is gathering companies committed to transitioning towards a zero-carbon economy. Net-Zero Tracker (2025) is compiling comprehensive data on both state and corporate commitments to net-zero emissions. A wide selection of companies internationally have already committed to 100% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (

Table 2). Some are pursuing zero emissions through their value chain, and not passing on the responsibility to others. How net-zero is defined, how the policies are implemented, and how the results are monitored requires careful scrutiny. The challenge is to embed sustainability policies deeply into the governance and operating processes of corporations.

Definitions:

Climate Neutral means eliminating all greenhouse gases (GHG) to zero, while also reducing all other environmental impacts an organisation might cause.

Net Zero means the company balances all greenhouse gases (GHG) released by its operations with an equivalent amount removed from the atmosphere by a range of means.

Climate Positive means the company goes beyond achieving net zero carbon emissions to create a benefit for the environment by removing additional carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

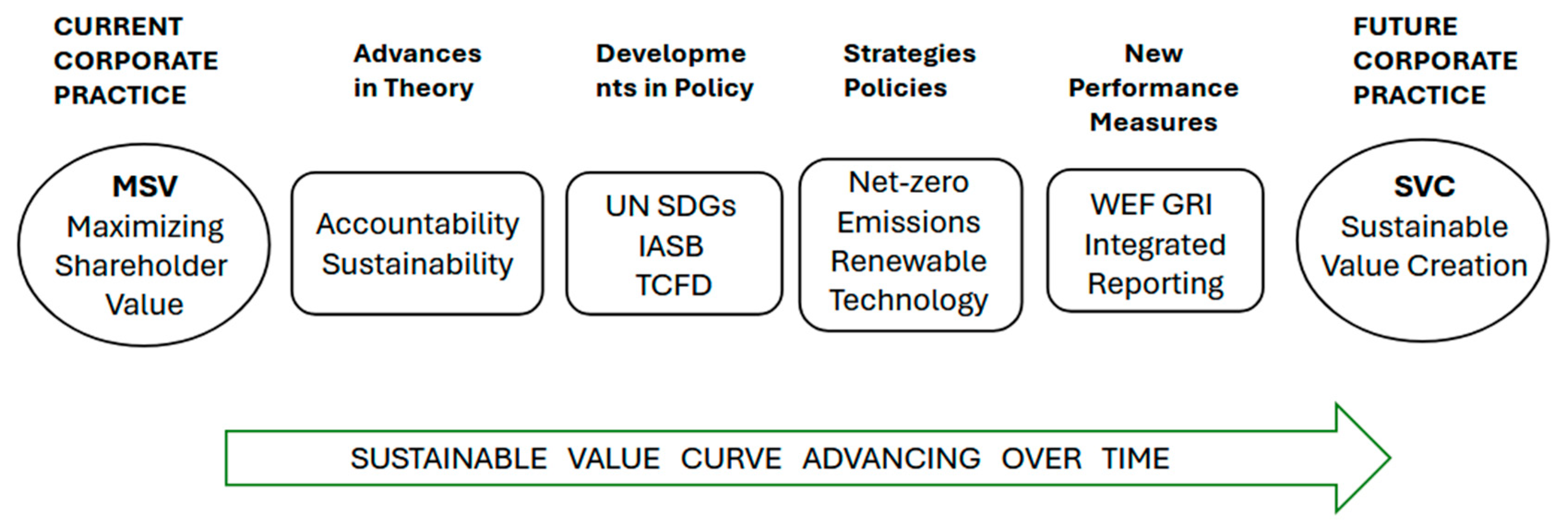

Reconceptualization of Corporate Purpose: The Pivot From Maximising Shareholder Value to Sustainable Value Creation

Committing to responsible and sustainable value creation requires a transformative engagement with new thinking and strategies which connect profit with purpose, embedding accountability and transparency, listening to stakeholders, and fully understanding non-financial risks. The logic of a transformation from maximizing shareholder value (MSV) to sustainable value creation is becoming compelling:

MSV SVC

The commitment towards sustainability represents a significant shift in corporate values and practices regarding the purpose of the company, with the strategic focus shifting from short term profit growth to longer term regeneration, from a single bottom line (profit) to a triple bottom line (people, planet, profit), and from a sole focus on financial measures of value creation to multiple measures of natural, human, social and financial value. This shift in focus is facilitated by advances in the theory of the firm supporting accountability and sustainability development in policy in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and International Accounting Standards Boards, and new integrated measures from the Global Reporting Initiative, World Economic Forum and many other international agencies (

Figure 3). This has produced a transformation towards a detailed conceptual overview of the strategic practices necessary to enable action towards sustainability (Monciardini and Mahonen 2026; Barker, R., and Mayer. C. (2024).

Will Digital Technology Drive Sustainability?

At the centre of this transformation towards sustainability is digital technology. The hegemonic transcendence of new business eco-systems with their distinctive business models is everywhere visible in terms of the digital devices we have now embraced as an intimate part of our everyday existence and the basis of both our work and domestic existence. There is a vast array of potential Industry 5.0 technological solutions which sustainable business may adopt (

Figure 4).

This technological transformation is not simply a US phenomenon but is global in impact. This internationalisation of the digital paradigm does not simply relate to the consumption and constant daily use of these tools (in any Japanese train carriage at any time look at the passengers, and every single one will be examining their smart phone!) The global hegemony of the platform technology companies is demonstrated by the infusion of the technological start-up culture almost everywhere from the great metropolis of the advanced industrial economies, through every Chinese and Indian urban community now thriving on digital technology, to small African villages (where securing a smart phone is almost synonymous with starting a business!)

There is a promising start-up culture in Europe, Asia, South America and other parts of the world, and though challenged by a multiplicity of languages and cultures, there is a growing affinity for digital solutions. For example, the uptake of financial technology for digital transactions in China exceeds the market in the United States by many trillions of dollars (Wildau and Hook 2017). This fast-cycle innovation, technological transformation and growth of corporations in the emerging economies represents a shift in economic power towards the global knowledge economy. (Clarke and Lee 2018).

For example, a renewed commitment to science, technology and innovation in the massive economy of China has led to outstanding achievements in applications of super computing, with significant advances in energy, environmental protection, advanced manufacturing, and biotechnology (Clarke and Lee 2018). China now excels in space related technologies, electric batteries, hypersonics and advanced radio-frequency communications. Popular innovations include high-speed rail, mobile payments and e-commerce. India is now following China’s progress focusing upon the knowledge economy.

Are Digital Technologies the Solution or Part of the Problem for Sustainability?

Digital Technology is widely seen as the key to sustainable industries and economies. New digital technologies inform every aspect of pollution measures and of emissions controls. Big Tech companies are determined to portray themselves as clean and green, and as the solution to global warming not part of the problem (WEF 2022a). The reality is of course that digital technology is one of the largest consumers of energy, one of the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases, and responsible for the vast and growing pollution of electronic waste. The digital industry is aware of the dissonance between its espoused ideals and its actual performance, and almost all of the major digital corporations have plans to achieve zero emissions. The question is will these plans be achieved? Potentially digital technology in the future can contribute to every industry aiming for zero emissions, but firstly the digital industry has to set its own house in order.

The Potential of Digital Technology to Support Sustainability

Digital technology has real potential to support sustainability:

Digital technologies can be used to measure and track sustainability progress, optimize resource use, reduce emissions, and promote a circular economy.

Digital technologies can support poverty reduction, promote sustainable farming and universal literacy.

Digital sustainability may promote the use of technology facilitating energy efficiency, waste reduction, and environmental impact.

The fusion of environmental responsibility, economic viability, and digital innovation supports organizations to work towards inclusivity and sustainability.

“Digital technologies will be key to the net-zero transition. They enable decarbonization with their ability to process more data more effectively, identify problems faster, and test solutions virtually. Energy-intensive systems will increasingly find efficiency gains from digital and Web3 technologies such as cloud and edge computing, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), internet of things (IoT) sensors, and blockchain technology” (MIT 2023).

Digital technologies can help reduce emissions in the energy, materials, and mobility industries. Estimates are that digital technologies may enable up to a 20% reduction by 2050 in the three highest emitting sectors of industry (energy, materials, mobility) WEF (2022b). By quickly adopting digital technologies, these industries can already reduce emissions by 4%-10% (MIT 2023). Examples of the potential impact of digital technologies on emissions include:

Digitization and technology can play a fundamental role in meeting our goal of being net-zero emissions company by 2050. To achieve this we rely on digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, robotic process automation (RPA), cloud solutions, advanced data analytics, and more (MIT 2023).

This is an essential part of the transition to sustainable knowledge economies (Clarke and Lee 2019). The knowledge economy index proposed by Diessner et al (2025:16) suggests six key underlying indicators: patents; technicians and associate professionals; information and communications technology; industrial robots; professionals; and managers.

The Reality Is that Big-Tech Is Itself a Big Source of Pollution

However, the reality is that though Big-Tech is potentially the means by which greenhouse gases and other pollutants will be dramatically reduced in the coming decades across many industries, presently Big Tech itself is simultaneously one of the biggest sources of pollution on the planet, and it is fast becoming much bigger as data centres multiply and vastly increase in size (Meaker 2024). The information technology sector currently accounts for up to 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and there are expectations this could rise to 14% by 2040, if there is not radical technological change in the industry (Gregg and Strengers 2024; Nafus et al 2021; Pasek and Wiessner 2023). The tech industry is caught in the dilemma of being the expert on reducing emissions in all other industries, while being challenged by the increasing emissions of its own sector as it continues to grow:

“Software engineers are also defining the tools used to measure the energy consumption of companies beyond the IT sector, through new product offerings that promise to measure carbon emissions to meet corporate sustainability reporting requirements. In this way, tech companies are promoting themselves as leaders in sustainability by providing the tools to track progress towards Net Zero goals. This is despite the fact that there has been significant research critique of the IT sector's practices and efforts to redirect technology developments and policies towards meaningful and deep sustainability impacts (Gregg and Strengers 2024:1; Lange et al 2023; Bergman and Foxon 2023).

Big Tech is caught in the dilemma of how to construct and run the hundreds of billions of dollars of giant data centers (that consume massive amounts of energy) to support their rapidly developing digital businesses (that are often at the forefront of reducing emissions from other industries), and how to achieve their published emissions reductions targets.

Data centers require continuous and massive amounts of energy to power the chips that run the algorithms for data analysis, and power video games. Secondly, continuous power is needed to cool the servers and prevent them cutting out, in addition to vast amounts of water. The IEA (2024:31) estimates that the demand for power from rapidly expanding data centers will double by 2026. All the Big-Tech companies have engaged in massive contracts with wind and solar farms, while electricity contractors buckle under the strain of providing for the demand for clean energy (Meaker 2024). The massive explosion of Artificial Intelligence in every industry and sector has yet to come, with a vast increase in the demand for energy (de Vries 2023) (meanwhile crypto-currency continues to expand its footprint, and will be utilizing even more hydro-electric power).

Reaching the Limits of Moore’s Law

The whole Big-Tech sector has depended upon the comforting ethos of Moore’s Law - which maintained that the numbers of transistors on a silicon chip would double roughly every two years, lowering costs and improving performance. “A techno-economic model that has enabled the IT industry to double the performance and functionality of digital electronics roughly every 2 years within a fixed cost, power and area. This expectation has led to a relatively stable ecosystem (e.g. electronic design automation tools, compilers, simulators and emulators) built around general-purpose processor technologies” (Shalf 2020:1),

Moore’s Law is the techno-economic model that has enabled the information technology industry to double the performance of digital electronics roughly every two years within a fixed cost and power. Meanwhile the advance of silicon lithography has enabled exponential miniaturization. However, as transistors reach atomic scale and fabrication costs continue to rise, the classical technological driver that has underpinned Moore’s Law for 50 years is failing and is anticipated to flatten by 2025 (Shalf 2020).

This presents significant challenges for the entire information technology industry and impacts upon options available to continue scaling of successors to existing technology, and to continue computing performance improvements in the absence of historical technology drivers. Beyond the myriad of technological challenges that this confronts the information technology industry with, there is that stark potential of needing significantly more energy to achieve any required improvements in computing power.

New Technological Paradigms and New Economies

The engineering paradigm of the information technology sector is not fit for purpose in a climate constrained planet where sustainable lifestyles must be developed. Net zero dashboards have a narrow set of measures and allow unsustainable practices to continue: energy efficiency improvements appear to show progress, but do not address the continuing growth in energy demand. The transition to a post-carbon economy requires new conceptual models involving changing organisations and livelihoods (Gregg and Strengers 2024).

There is a call for a new Digital Green Deal (Santarius et al (2023) that essentially involves:

A broad vision about the role digital technologies are playing in the prospect for people to earn a living within humanity’s safe operating space, recognizing environmental challenges, ensuring coherence between sustainability policy and digital policy.

Sustainability policies should foster the development and application of digital solutions that aim to spur genuine transformations in systems of provision and distribution while simultaneously minimizing usage of digital innovations that are counterproductive from an environmental perspective. Digital opportunities and risks should be addressed in a cross-cutting manner, for instance in legislation on circular economy, governance of value-chains and corporate accountability requirements. Opportunities and risks should also be addressed in sectoral policies, thereby advancing sustainability transformations in energy, mobility, agriculture, building/housing, industry, and consumption of goods and services.

Digital policies should include elements that serve sustainability goals. For example, most platform markets lack ‘production standards’ – there are neither energy standards for video streaming or social media platforms, nor are services on rental or sharing platforms bound to contribute to low-energy housing or reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in transportation. Since comparatively strong platform legislation such as the Digital Services Package of the European Union do not fill this void, future legislation is needed that includes environmental and social standards for service provision in platform markets. Similarly, policies regarding data governance, artificial intelligence, e-commerce, digital finance, crypto-currencies among others should include legislation that advances sustainability goals.

The Hegemony of Big Tech

Yet any proposed reforms of technology to adapt to the needs of sustainability run the risk of becoming owned by Big Tech. The hegemony of Big Tech is nowhere clearer than in the domination of the US stock exchanges by platform-oriented companies with vast market capitalization far beyond anything witnessed before. The universality of Microsoft was achieved decades ago, but the more recent arrival of the platform hegemony of NVIDIA, Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Broadcom, Meta, and Tesla has astonished the world and overwhelmed the US public stock market (

Table 3).

There are profound critiques of the self-interest driving Big Tech, Rikap and Weko (2025) argue:

“The energy transition offers a potentially profitable business for companies that monopolize artificial intelligence (AI) and digital infrastructures. Above all, these companies are Amazon, Microsoft and Google – since they control the whole AI value chain from the required datasets and research networks to the start-ups producing AI applications (Rikap 2024a; 2024b; Van Der Vlist et al. 2024).

The space for these giants to offer digital green solutions grows as governments and businesses invest in research and development (R&D) for addressing the ecological crisis and integrate ecological risks and needed action to their economic calculations. AI is a method of invention increasingly applied to every science and technology domain” (Cockburn et al. 2018).

Promising new technologies may help local communities, but in the background Big Tech is often firmly in control:

“Energy transitions break geographic monopolies on fossil fuel resources and are expected to redistribute economic benefits to new actors, from local communities to developing countries. At the same time, basing energy systems around renewables increases the importance of intangible assets such as data and artificial intelligence (AI). As different IPE approaches have shown, such intangibles can be monopolized by lead firms and especially Big Tech, which increasingly provide crucial digital infrastructures” (Weko 2025:1571).

The critical question must be asked “What role Big Tech firms may play in energy systems, and whether their access to intangibles enables them to expand to the energy sector? The case study of Amazon illustrates that data-driven intellectual monopolies are well-positioned to expand into energy, benefiting from their position as providers of data infrastructures, and capacities in data harvesting and analysis. Amazon is both developing and marketing its own innovations and investing in energy systems businesses. As intangibles gain importance in energy systems, possible implications for the IPE of energy include power and economic value flowing towards Big Tech, rather than countries or communities” (Weko 2025:1571).

It is in this corporate monopolistic context that the most profound and transforming paradigm shifts are to come, concerning the application of digital technologies to the enveloping issues of sustainability and regeneration in an environment and ecology that is reaching the planetary boundaries of its survival. The ecological sustainability of industrial civilisation requires urgent resolution. These environmental challenges will concentrate minds for decades with the application of advanced innovative green technologies intended to create a balance between industry and the ecology.

From the Sustainability to the Regeneration Paradigm

The most critical paradigm change of all is the one towards regeneration. It is the devastation of the natural world in recent decades that has received the least attention and needs critical remedy. The stock of natural capital is being depleted rapidly, and without this to support us, all life on earth is jeopardized:

“We consume more natural resources than the planet can regenerate… As global biodiversity continues to decline steeply, the health and functioning of crucial ecosystems like forests, the ocean, rivers and wetlands will be affected. Coupled with climate change impacts which are evident in warnings from scientists and the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events worldwide; this is going to be disastrous for the ecological balance of the planet and for our survival. Earth Overshoot Day is a stark reminder of the urgent actions individuals, countries and the global community must take to protect forests, oceans, wildlife and freshwater resources and help achieve resilience and sustainable development for all” (WEF 2018).

There is a growing commitment to transform the global economy from a linear economy towards a regenerative circular economy which is restorative rather that depletive of the eco-systems of the world (European Commission 2015a). UNIDO (2024) suggests the key issues in the business and environmental transformation towards sustainability (

Table 4) across both the public and private sectors. This drive towards decarbonizing supply chains, and reconceptualizing product design, and integrating skills and technology design will become universal across all sectors and industries.

According to Konietzko, Das, and Bocken (2023:372) “The starting point for regenerative thinking in organizations is the realization that humans are embedded in, part of and fundamentally dependent on nature. The economics of biodiversity and nature have been well summarized in a recent independent review (Dasgupta, 2021). The review describes the need for effective institutions, both in local communities, civil society as well as within nation states to enable regenerative markets. These institutions are about trust and clear rules, observation, cooperation, verification and enforcement of rules to ensure the sustainability of social-ecological systems (Ostrom, 2009).”

Regenerative Futures

The regeneration paradigm suggests a profound and substantive regeneration of new life: reviving nature, renewing industry and economies, reconceiving design. Such concepts have been widely used in science, medicine, the arts and society. Now these concepts may be applied to regenerative agriculture, a restorative economy, and regenerative design:

“The ecologist and entrepreneur Hawken (1993) used the term restorative economy to describe an economy that combines business activities with environmental (restorative) practices. Hawken (1993:58) argued that “to restore is to make something well again,” which needs to be applied by the economy to ecosystems… Regenerative development and design, advanced by the architect Lyle (1994), reflects his case for a convergence of disciplines including architecture, landscape ecology, land-use planning, permaculture, and regenerative agriculture (see Mang & Reed, 2012). According to Lyle (1994, 10) “in order to be sustainable, the supply systems for energy and materials must be continually self-renewing, or regenerative, in their operation.” Lyle (1994) set the framework, principles, and strategies for reversing environmental damage, conceptualizing regenerative design and circular flows as a replacement for linear systems” (Morseletto 2020a; 2020b).

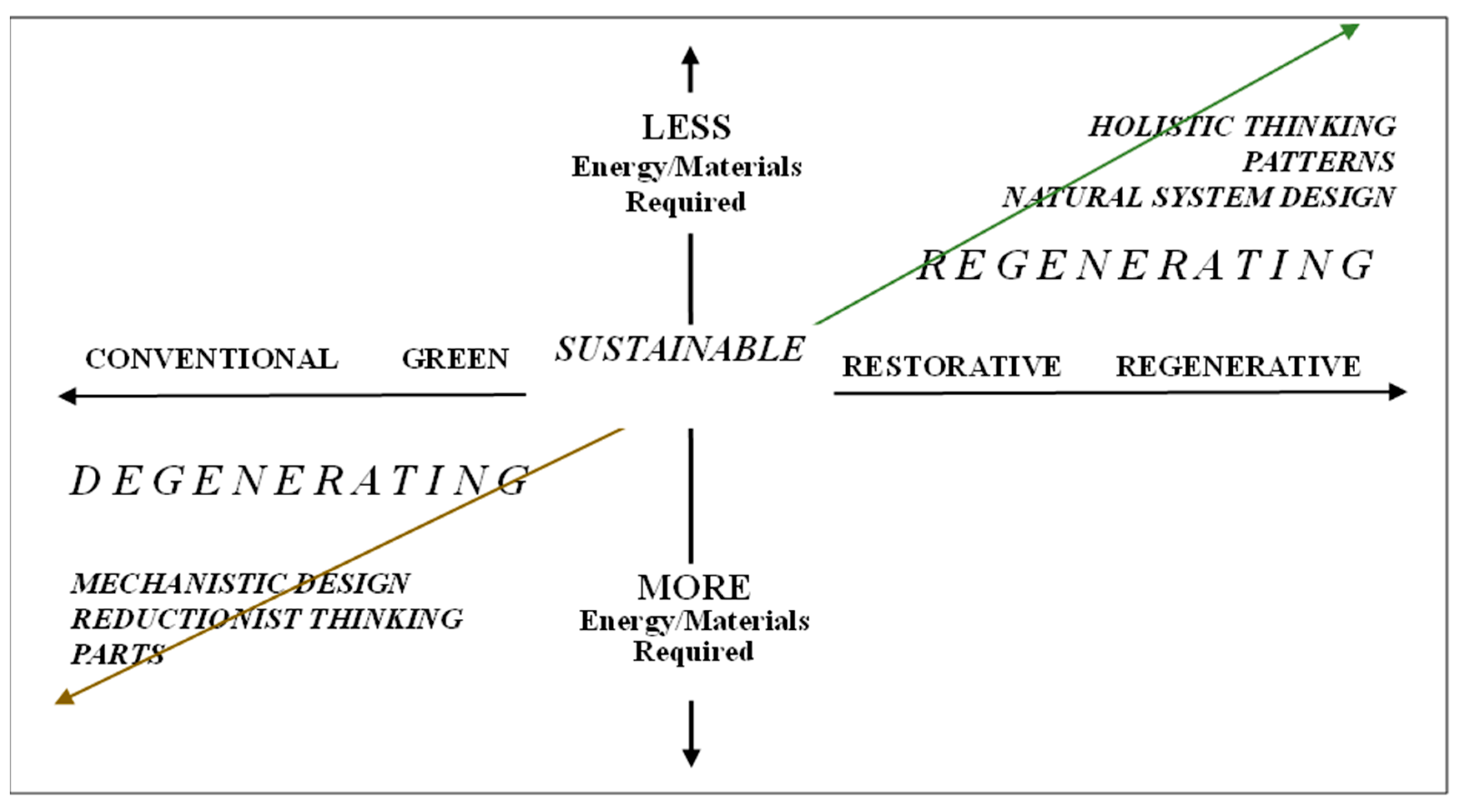

At their most ambitious regenerative business models in creative ways demonstrate how humanity can work with nature ending what UN Secretary General Gutteres has described as the mission to “end the suicidal war on nature” (UNRIC 2022). We are now in a position to move strategically from degenerative to regenerative strategies in many industries and this is already beginning to occur (Blau, Luz and Panagopoulos 2018; Konietzko, Das and Bocken, 2023). Mechanistic design and reductionist thinking is being extensively replaced by more holistic approaches and natural systems thinking, enabling restorative and regenerative approaches building communities and industries, working in harmony with the environment and ecology instead of randomly destroying it (

Figure 5).

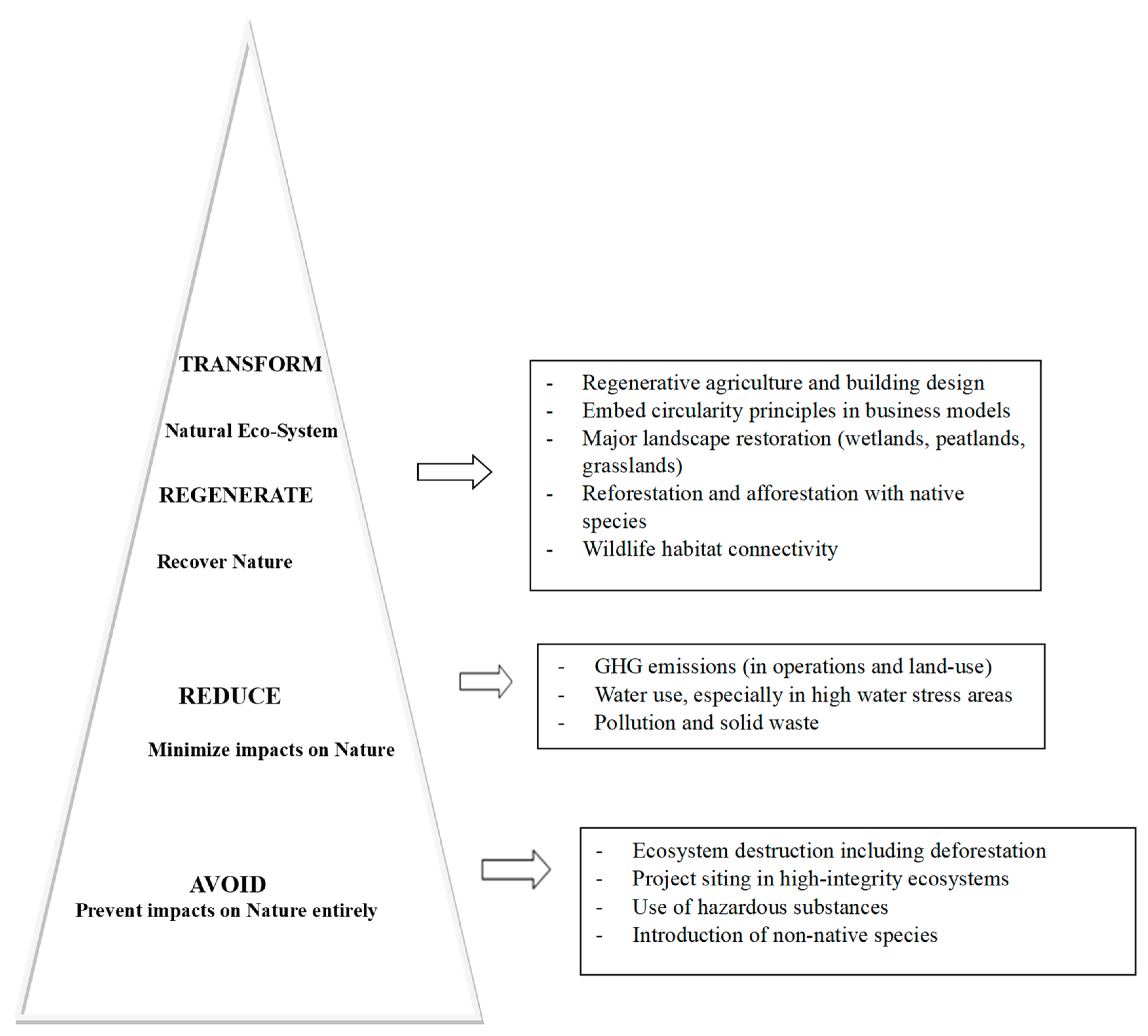

An Action Framework on how to become nature positive is elaborated by Science Based Targets for Nature (SBTN) that includes a hierarchy of actions of what to avoid, what to reduce, and what to regenerate in order to contribute to the transformation towards a natural system-wide change in the business environment (

Figure 6). Beginning with avoiding the injurious impacts upon nature and eco-systems inflicted in the environmentally hazardous industrial practices of the past; building to reducing the overall impact upon nature by reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and water use; and working towards recovering nature with regenerative agriculture and building design, landscape restoration and reforestation.

As with all scientific revolutions there is now a vast amount of work on regeneration being undertaken by an international array of institutions including the Natural Capital Protocol, Science Based Targets for Nature, the Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), European Sustainability Reporting Standards, and the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). These bodies collectively are developing standards to measure the impacts of business upon nature, with new concepts of materiality, to alert and inform stakeholders, and to guide investment institutions in their decision making. If companies omit, obscure or misstate the impacts upon nature that in reality have occurred in their operations, and which these international agencies and reporting standards will reveal, then this will influence investor decisions and could be subject to legal action (

Table 5).

Conclusions

The regeneration paradigm ironically has the task of restoring all the ecological damage created since the beginning of the industrial revolution. The first paradigmatic shift towards mechanization and steam power, besides greatly expanding the material wealth of human economy and society, began an unfortunate and ultimately disastrous destruction of the natural world, and ultimately of the ecology of the planet. All of the paradigm shifts that have occurred in the last two centuries have in some way contributed mightily to this despoilation of nature, and undermining of the ecological balance.

Now it is time to repair the damage before it is too late. Instead of destroying nature we have to work in service of nature, restoring and enhancing ecosystems and diversity. In the process we have to work towards reducing the harshness of inequalities that undermine societies and promote the well-being of communities. The advance of the well-being and health of the people and the planet, providing habitat for native plants and animal species that have been brought to the brink of extinction is a worthy goal. We have to create the means to withstand the dangers of climate change with nature based design, developing new protective eco-systems. If we achieve all this, the regenerative paradigm will be recognized as the greatest human and scientific achievement of all (Konietzko, Das and Bocken 2023).

References

- ABA (2015) Report 1On Sustainable Development, American Bar Association https://climate.law.columbia.edu/sites/climate.law.columbia.edu/files/content/docs/others/final_sdtf_aba_annual_08-2015.authcheckdam.pdf.

- Abramitzky, R. and M. Drelichman (2025) Knowledge, Technology, and Growth: Joel Mokyr, Nobel Laureate, VOXEU, CEPR25, Centre for Economic Policy Research, October 2025 https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/knowledge-technology-and-growth-joel-mokyr-nobel-laureate.

- Acemoglu, D. and S. Johnson (2024) Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity, Basic Books.

- Adams, J. (2013) The Fourth Age of Research, Nature, 497, 557-560 (the best science comes from international collaboration…). [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P. and P. Hewitt (1990) A Model of Economic Growth Through Creative Destruction, National Bureau of Economic Research,.

- Aghion, P., Dechezleprêtre, A., Hemous,D., Martin, R., Van Reenen, J. (2016) Carbon Taxes, Path Dependency, and Directed Technical Change: Evidence from the Auto Industry, Journal of Political Economy, 124, 1, 1-51. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P., and Tushman, M.L. (1990) Technological discontinuities and dominant designs: A cyclical model of technological change, Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 604–633. [CrossRef]

- Arthur, W.B., Durlauf, S., and Lane, D. (1997) The Economy as an Evolving Complex System II, Addison-Wesley.

- Baldwin, C. and E. Von Hippel (2011) Modelling a Paradigm Shift: From Producer Innovation to User and Open Collaborative Innovation, Organization Science, Vol. 22, No. 6 (November-December 2011), pp. 1399-1417. [CrossRef]

- Barker, R., and Mayer. C. (2024). Seeing double corporate reporting through the materiality lenses of both investors and nature, Accounting Forum. [CrossRef]

- Bergman, N., T.J. Foxon (2023) Drivers and effects of digitalization on energy demand in low-carbon scenarios, Climate Policy, 23 (3) (2023) 329–342. [CrossRef]

- Blau, M-L, Luz, F. and Panagopoulos,T. (2018) Urban River Recovery Inspired by Nature-Based Solutions and Biophilic Design in Albufeira, Portugal, Land, 7,4, 141. [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E., D. Li, and L.R. Raymond (2023) Generative AI at Work, NBER Working Paper 31161,.

- Carney, M. (2015) Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon – Climate Change and Financial Stability, Bank of England, 29 September 2015 Breaking the tragedy of the horizon - climate change and financial stability - speech by Mark Carney | Bank of England.

- CBINSIGHTS (2022) The Big Tech in Sustainability Report: How Amazon, Google and Microsoft are Tackling Emissions. https://www.cbinsights.com/research/report/big-tech-sustainability-climate-tech/.

- Chandler, A. D. (1977) The Visible Hand: Managerial Revolution in American Business, Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press.

- Chandler, A. D. (1990) Scale and Scope—The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvjz80xq.

- Chesbrough, H. and Bogers, M. (2014) Explicating Open Innovation, in, Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W. and West, J. (eds), New Frontiers in Open Innovation, 2-28, Oxford University Press.

- Clarke T. and Clegg, S. (2005) Changing Paradigms: The Transformation of Management Knowledge for the 21st Century, London: Profile Books Edition 2005.

- Clarke, T. and Lee, K. (2018) Innovation in the Asia Pacific: From Manufacturing to Knowledge Economies, Singapore: Springer.

- Clarke, T., O’Brien, J. and O’Kelley, C. (2019a) The Oxford Handbook of the Corporation, Oxford University Press.

- Clarke, T. (2019b) The Greening of the Corporation, in, Clarke, T., O’Brien, J. and O’Kelley, C. (2019) The Oxford Handbook of the Corporation, Oxford University Press, 589-640.

- Clarke, T. (2019c) Creative Destruction, Technology Disruption and Growth, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics, and Finance, Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, T. (2023) Corporate Governance: Innovation, Crisis and Reform, London, Sage, pp 275.

- Clarke, T. (2024) International Corporate Governance, Third Edition, London: Routledge.

- Clarke, T., Edwards, M. and Benn, S. (2026) The Routledge Companion to Corporate Sustainability, Routledge.

- Colby, M.E. (1989) The Evolution of Paradigms of Environmental Management in Development, SPR Discussion Paper No 1, Strategic Planning Division, The World Bank.

- da Cunha, I., R. Policarpo, P. Oliveira, E. Abdala, and D. Rebelatto, (2025) A systematic review of ESG indicators and corporate performance: proposal for a conceptual framework, Future Business Journal, 11-106. https://fbj.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s43093-025-00539-1. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, K. (2021) The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence, Yale University Press https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1ghv45t?turn_away=true.

- Crawford, K. (2024) Generative AI’s Environmental Costs Are Soaring – And Mostly Secret, Nature, 20 February 2024 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-00478-x.

- Dasgupta, P., (2021. The Economics of Biodiversity: the Dasgupta Review: Full Report.

- Davis, G.F. (2016) The Vanishing American Corporation: Navigating the Hazards of A New Economy, San Francisco: Berrett-Kohler.

- de Bakker, F. G., Matten, D., Spence, L. J., & Wickert, C. (2020). The elephant in the room: The nascent research agenda on corporations, social responsibility, and capitalism. Business & Society. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0007650319898196.

- Delemarle, A., and Larédo, P. (2014) Governing radical change through the emergence of a governance arrangement, in, S. Borrás & J. Edler (eds.), The Governance of Socio-Technical System: Explaining Change. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 159–186.

- Diessner,S., D. Hope, N. Durazzi, H. Kleider, F. Filetti , S. Tonelli (2025) The Transition to the Knowledge Economy in Advanced Capitalist Democracies: a New Index for Comparative Research, Socio-Economic Review, Vol. 00, No. 0, 1–30 De Vries, A. (2023) The Growing Energy Footprint of Artificial Intelligence, Joule, 7, 10, 2191-2194.

- Estabrooks, M. (1995) Electronic Technology, Corporate Strategy, and World Transformation, Praeger.

- European Commission (2022) Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937, 23.2.2022, COM(2022) 71 final.

- European Commission (2023) Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2772 of 31 July 2023 supplementing Directive 2013/34/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards sustainability reporting standards, C/2023/5303, OJ L, 2023/2772, 22.12.2023, ELI: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2023/2772/oj.

- Freeman, R.E. (1987) The Challenge of New Technologies, Paris: OECD.

- Folk, E. (2020) 10 Ways Technology is Revolutionizing Sustainability, Green Journal, 20 February 2020 https://www.greenjournal.co.uk/2020/02/10-ways-technology-is-revolutionising-sustainability/.

- Ford, M. (2015) The Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of Mass Unemployment, Oneworld, 2015.

- Gayle, D. (2024) Banks Have Given Almost $7 trillion to Fossil Fuel Firms Since the Paris Deal, The Guardian, 13 May 2024 https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/may/13/banks-almost-7tn-fossil-fuel-firms-paris-deal-report?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other.

- George, G. and Lin, Y. (2017) Analytics, innovation, and organizational adaptation. Innovation,19 (1): 16–22. [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M., M. Iranmanesh, M.F. Mubarak, M. Mubarik, A. Rejeb, and M. Nilashi (2022) Identifying Industry 5.0 Contributions to Sustainable Development: A Strategy Roadmap for Delivering Sustainability Values, Sustainable Production and Consumption, 33, 2022, 716-737. [CrossRef]

- Gregg, M. and Y. Strengers (2024) Getting Beyond Net Zero Dashboards in the Information Technology Sector, Energy Research and Social Science, 108, 103397, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Greif, A, J Mokyr and G Tabellini (2025) Two Paths to Prosperity: Culture and Institutions in Europe and China, 1000-2000, Princeton University Press, forthcoming.

- Grierson,D.(2009) The Shift From a Mechanistic to an Ecological Paradigm, International Journal of Environmental, Cultural, Economic and Social Sustainability, 5, 5, 197-206. [CrossRef]

- Groopman, J. and D. Lanyard () Regenerative Technology: Technological Innovation to Service Life, Regenerative Technology Project https://www.regentech.co/regenerative-tech-resources/.

- Hahn, R., Reimsbach, D. and Wickert, C. (2023) ‘Nonfinancial Reporting and Real Sustainable Change: Relationship Status—It's Complicated,’ Organization & Environment, 36, 3–16.

- Hawken, P. (1993). The eEcology of Commerce: A Declaration of Sustainability. New York: Harper Collins Business.

- Hawken, P., A.B.Lovins, L.H. Lovins, (1999) Natural Capitalism, Little Brown and Company.

- Hawken, P., A.B.Lovins, L.H. Lovins, (1999) Natural Capitalism, Little Brown and Company.

- Haywood, A, C. Dayson, R. Garside, A. Foster, R. Lovell, K. Husk, E. Holding, Thompson, J., K. Shearn, H.A. Hunt, J. Dobson, C. Harris, R. Jacques, D. Witherley, P. Northall, M. Baumann, I.Wilson, National Evaluation of the Preventing and Tackling Mental Ill Health through Green Social Prescribing Project: Final Report, January 2024, UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. https://randd.defra.gov.uk/ProjectDetails?ProjectId=20772.

- Horton, H. (2025) No Major Banks Have Yet Committed to Stop Funding New Oil, Gas and Coal, Research Finds, The Guardian, 22 October 2025 https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/oct/22/no-major-banks-have-yet-committed-to-stop-funding-new-oil-gas-and-coal-research-finds?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other.

- International Energy Authority (IEA) (2021) Five Ways Big Tech Could have Big Impacts on Clean Energy Transitions, IEA. https://www.iea.org/commentaries/5-ways-big-tech-could-have-big-impacts-on-clean-energy-transitions.

- International Energy Authority (IEA) (2024) Electricity 2024 Analysis ad Forecast for 2026, International Energy Authority https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/6b2fd954-2017-408e-bf08-952fdd62118a/Electricity2024-Analysisandforecastto2026.pdf.

- Jacobs, M. (2025) Trump vs. Earth, Inside Story, 29 October 2025 Trump vs. Earth Inside Story.

- Jahn, V., A. Brochard, N. Diaz, and A. Hajagos-Toth (2024) TPI Centre Net Zero Banking Assessment Framework: Methodology Note, Transition Pathway Initiative https://www.transitionpathwayinitiative.org/publications/uploads/2024-tpi-centre-banking-assessment-framework-methodology-note.pdf.

- Kalyani, A., N. Bloom, M., C., Tarek, A. Hassan, J. Lerner, A. Tahoun (2024) The Diffusion of New Technologies, NBER Working Paper Series 28999. https://www.nber.org/papers/w28999.

- Kuhn, T. (2012) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, University of Chicago Press.

- Konietzko, J., Das, A. & Bocken, N. (2023). Towards regenerative business models: A necessary shift? Sustainable Production and Consumption, 38, 372–388. [CrossRef]

- Kondratiev, N. (1925) The Major Economic Cycles (1925).

- Konietzko, J., Das, A. & Bocken, N. (2023). Towards regenerative business models: A necessary shift? Sustainable Production and Consumption, 38, 372–388. [CrossRef]

- Lancet Planetary Health-Earth Commission Report (2024) Earth-system Boundaries, Translations, and Transformations https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S2542-5196%2824%2900042-1.

- Lange, S., T. Santarius, L. Dencik, T. Diez, H. Ferreboeuf, S. Hankey, A. Hilbeck, L. M. Hilty, M. H¨ojer, D. Kleine, J. Pohl, A.L. Reisch, M. Ryghaug, T. Schwanen, P. Staab,(2023) Digital Reset: Redirecting Technologies for the Deep Sustainability Transformation, Digitalization for Sustainability; Oekom, Germany, 2023.

- Lanzolla, G., Lorenz, A., Miron-Spektor, E., Schilling, M., Solina, G., Tucci, C. (2018), Digital Transformation: What Is New If Anything? Academy of Management Discoveries 4, 3, 378–387. Online only . [CrossRef]

- Leffer, L. (2023) The AI Boom Could Use a Shocking Amount of Electricity, Scientific American, 13 October 2023 https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-ai-boom-could-use-a-shocking-amount-of-electricity/.

- Lester, M. (2018) The Creation and Disruption of Innovation? Key Developments in Innovation as a Concept, Theory, Research and Practice, in Clarke, T. and Lee, K. (2018) Innovation in the Asia Pacific: From Manufacturing to Knowledge Economies, Singapore: Springer, pp 271-328.

- Logue, D. (2019) Corporations in the Clouds? The Transformation of the Corporation in an Era of Disruptive Innovations, in, Clarke, T., O’Brien, J. and O’Kelley, C. (2019) The Oxford Handbook of the Corporation, Oxford University Press, 515-538.

- Louca, F. and Mendonca, S. (2002) Steady Change: the 200 Largest US Manufacturing Firms Throughout the 20th Century, Industrial and Corporate Change, 11, 4, 817-845. [CrossRef]

- Lyle, J. T. (1994) Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Mang, P., & Reed, B. (2012). Regenerative Development and Design, In R. A. Meyers (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology (pp. 8855–8879). New York: Springer.

- Markides, C., & Sosa, L. (2013) Pioneering and first mover advantages: the importance of business models, Long Range Planning, 46(4): 325–334. [CrossRef]

- Meaker, M. (2024) The Big-Tech Clean Energy Crunch is Here, Wired, 3 June 2024 https://www.wired.com/story/big-tech-datacenter-energy-power-grid/.

- MIT Technology Review (2023) Digital Technology: The Backbone of a Net-Zero Emissions Future. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/03/08/1069473/digital-technology-the-backbone-of-a-net-zero-emissions-future/.

- Mokyr, J (1990), The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress, Oxford University Press.

- Mokyr, J. (2017) A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy, Princeton University Press.

- Morseletto, P. (2020a) Restorative and Regenerative: Exploring the Concepts in the Circular Economy, Journal of Industrial Ecology, 24, 4,763-773 Restorative and regenerative: Exploring the concepts in the circular economy (wiley.com). [CrossRef]

- Monciardini, D., Mähönen, J., & Tsagas, G. (2020). Rethinking Non-Financial Reporting: A Blueprint for Structural Regulatory Changes. Accounting, Economics, and Law: A Convivium, 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Monciardini, D., Mähönen, J., (2026) Redefining Value Creation: Paradigm Changes in Corporate Reporting, in, T. Clarke, S. Benn and M. Edwards, The Routledge Companion to Corporate Sustainability, London: Routledge.

- Monciardini, D., Rocca, L., & Veneziani, M. (2024). Virtuous circles: Transformative impact and challenges of the social and solidarity circular economy. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(2), 642-660. [CrossRef]

- Nafus,D., E.M. Schooler, K.A. Burch, (2021) Carbon-responsive computing: changing the nexus between energy and computing, Energies 14 (21) (2021) 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Nobel Prize (2025) From Stagnation to Sustained Growth, Outreach 13 October 2025 https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2025/popular-information/>.

- Ostrom, E., (2009) A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems, Science 325 (5939), 419–422. [CrossRef]

- Pasek,A., M. Wiessner (2023) Carbon Accounting and Computing, Branch Magazine 5, 2023.

- Rame, R., P. Purwanto, S. Sudarno (2024) Industry 5.0 and Sustainability: An Overview of Emerging Trends and Challenges for a Green Future, Innovation and Green Development, 3, 100173. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.B., M.D. Ashafki, K.Kausik (2024) AI Revolutionizing Industries Worldwide: A Comprehensive Overview of its diverse applications, Hybrid Advances, 7. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M., M. Lengieza, M. P. White, U.S. Tran, M. Voracek, S. Stieger, V. Swami (2025) Macro-level Determinants of Nature Connectedness; An Exploratory Analysis of 61 Countries, Ambio. [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J. et al (2009) A Safe Operating Space for Humanity, Nature, 461, 472-475 https://www.nature.com/articles/461472a. [CrossRef]

- Regenerative Technology Project (2025) Regenerative Tech Resources Regenerative Tech Resources - Regenerative Technology.

- Rewild (2025) We Don’t Need to Reinvent the Planet: We Need to Rewild It, Rewild. https://www.rewild.org/.

- Richardson, M., M. Lengieza, M. P. White, U.S. Tran, M. Voracek, S. Stieger, V. Swami (2025) Macro-level Determinants of Nature Connectedness; An Exploratory Analysis of 61 Countries, Ambio. [CrossRef]

- Rikap, C. and S. Weko (2025) A Green Transition Orchestrated From Big Tech Clouds? Globalizations, (09 Sep 2025. [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J. et al (2009) A Safe Operating Space for Humanity, Nature, 461, 472-475 https://www.nature.com/articles/461472a. [CrossRef]

- Santarius,T., L. Dencik, T. Diez, H. Ferreboeuf, P. Jankowski, S. Hankey, A. Hilbeck,L.M. Hilty, M. Hojer, D. Kleine, S. Lange, J. Pohl, L. Reisch, M. Ryghaug, T. Schwanen, P. Staab (2023) Digitalization and Sustainability: A Call for A Digital Green Deal, Environment Science and Policy, 147, 2023, 11-14. [CrossRef]

- Shalf, J. (2020) The future of computing beyond Moore’s Law, Phil. Trans. R.Soc. A 378: 20190061 Royal Society. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsta.2019.0061.

- Schumacher, E.F. (1973) Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered, Harper Collins – small and appropriate technologies, policies and polities are a superior alternative to the mainstream belief that ‘bigger is better.’.

- Schumpeter, J. (1975) Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, New York: Harper.

- Schwab, K., & Davis, N. (2018) Shaping the Fourth Industrial Revolution, Geneva: World Economic Forum.

- Scheja, E. and K.B. Kim (2024) Rethinking Economic Transformation for Sustainable and Inclusive Development, Edward Elgar, International Labour Office https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollbook-oa/book/9781035348466/9781035348466.xml.

- Schwab, K. and Davis, N. (2018) Shaping the Fourth Revolution, World Economic Forum.

- Science Based Targets Network (2020) Science Based Targets for Nature: Initial Guidance for Business, Science Based Targets Network Global Commons Alliance. https://sciencebasedtargetsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/SBTN-initial-guidance-for-business.pdf.

- Smith A. (1776) The Wealth of Nations .

- Sovacool, B.K., & Hess, D.J. (2017) Ordering theories: Typologies and conceptual frameworks for sociotechnical change, Social Studies of Science, 47, 5, 703–750. [CrossRef]

- Spolare, E. (2019) Commanding Nature by Obeying Her: A Review Essay on Joel Moky’s A Culture of Growth, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 26061. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26061.

- The Lancet Planetary Health Commission (2024) A just world on a safe planet: a Lancet Planetary Health–Earth Commission report on Earth-system boundaries, translations, and transformations, Vol 8, October 2024 http://www.thelancet.com/planetary-health.

- Thompson F, Chau S, Nguyen M (2025). Nature Economics: Analysis of the case for Australian Government investment in nature, Cyan Ventures and 30 by 30.

- UNIDO (2024) The New Era of Industrial Strategies: Tackling Grand Challenges through Public-Private Collaboration, White Paper, United Nations Industrial Development Organization, Cambridge Industrial Innovation Policy, World Economic Forum https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_New_Era_of_Industrial_Strategies_2024.pdf.

- United Nations, The Impact of Digital Technologies, https://www.un.org/en/un75/impact-digital-technologies.

- UNRIC 2022.

- Wang, Q., Wang, X. Li, R. Jiang,X (2024) Reinvestigating the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) of carbon emissions and ecological footprint in 147 countries: a matter of trade protectionism, Humanities and Social Science Communications, 11, 160 . [CrossRef]

- Watts, J. and X. Xipai (2025) Change Course Now: Humanity has Missed 1.5C Target Says UN Head, The Guardian, 28 October 2025.

- WBCSD (2023) Implementation Guidance for the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) Standards, and the European Sustainability Reporting Standards, WBCSD.

- WBCSD (2024) The Roadmap to Nature Positive: Foundations for All Business, 12 September 2024. https://www.wbcsd.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Roadmaps-to-Nature-Positive-Foundations-for-all-business.pdf.

- WBCSD (2024) Corporate Accountability System for Nature. https://www.wbcsd.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Roadmaps-to-Nature-Positive-Foundations-for-all-business.pdf.

- World Economic Forum (WEF) (2018) Technology can help us save the planet. But more than anything, we must learn to value nature, World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/08/here-s-how-technology-can-help-us-save-the-planet/.

- World Economic Forum (WEF) ( 2020) Regenerative business: a roadmap for rapid change, 17 January 2020 Why regenerative business is a roadmap for rapid change | World Economic Forum (weforum.org).

- World Economic Forum (WEF) (2022a) Rewilding: Letting Nature Do Its Own Thing, 22 October 2022 Rewilding can help people and the planet – here’s how | World Economic Forum (weforum.org).

- World Economic Forum (2022b) 3 Ways Digital Technology Can Be A Sustainability Game-Changer, WEF. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/01/digital-technology-sustainability-strategy/.

- World Economic Forum (2022c) Digital Tech Can Reduce Reduce Emissions by up to 20% in High-Emitting Industries, WEF. https://www.weforum.org/press/2022/05/digital-tech-can-reduce-emissions-by-up-to-20-in-high-emitting-industries/.

- Weko, S. (2025) New Sites of Accumulation? Why Intangible Assets Matter for Energy Transitions, Review of Political Economy, 37:4, 1571-1598. [CrossRef]

- Zapp, M. (2022) Revisiting the Global Knowledge Economy: The Worldwide Expansion of Research and Development Personnel, 1980–2015, Minerva, 60:181-208 Revisiting the Global Knowledge Economy: The Worldwide Expansion of Research and Development Personnel, 1980–2015 | Minerva. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, A. et al (2025) Emerging Tech Impact Radar: Generative AI, Gartner, gartner.com.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |