1. Introduction

Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterised by loss of dopaminergic neurons and α-synuclein accumulation in the substantia nigra pars compacta [

1]. PD affects approximately 11–12 million people globally, and its prevalence is projected to more than double to ~25.2 million by 2050, driven primarily by population ageing [

2]. This growing prevalence is associated with a substantial economic burden. In Australia, the mean annual health care cost per person with PD is estimated to be AUD

$32,556, with an additional societal cost of approximately AUD

$45,000 per person per year [

3]. Clinically, PD presents with motor symptoms such as bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor, and postural instability, alongside non-motor symptoms including cognitive impairment, autonomic dysfunction, and psychiatric disturbances, all of which can reduce functional capacity and quality of life (QoL) [

4,

5].

Current treatments primarily target symptomatic relief through dopaminergic replacement but do not slow disease progression and can have adverse effects [

5]. Non-pharmacological interventions, including photobiomodulation (PBM) and aerobic exercise (AE), have shown promise in improving clinical signs and promoting neuroprotection [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. PBM, using red to near-infrared wavelengths of light (630–850 nm), may enhance mitochondrial function via cytochrome c oxidase activation [

11], while AE promotes neuroplasticity, neuroprotection and mitochondrial function with improved cardiovascular fitness and cerebral blood flow [

8,

10,

12].

PD is increasingly recognised as a multisystem disorder affecting vision [

13]. Patients may experience decreased vision, contrast sensitivity, and visuospatial difficulties due to retinal dopamine deficiency, α-synuclein accumulation, and structural changes in the retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) and ganglion cell layer of the eye [

13,

14,

15]. Microvascular alterations, including reduced choroidal thickness and vascular perfusion, have also been observed using optical coherence tomography (OCT) and optical coherence tomography angiography (OCT-A) [

16]. While PBM and AE show clinical benefits in PD, their impacts on ocular function remain underexplored.

The brief report presents a subset of findings from a larger multidisciplinary randomised pilot trial comparing the impacts of PBM, AE, their combination, and a sham intervention on the clinical signs and symptoms of PD. The present analysis focuses on the impacts of PBM and AE on visual function and ocular health, and their impact on patient-reported QoL outcomes, using pre- and post-intervention measures to evaluate potential ocular and functional benefits. Here, the term ‘intervention’ refers to PBM, AE, or a combination of both.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Twenty participants (male = 12, female = 8) aged between 47 and 82 years (mean age, 76.1 ± 8.8 years) diagnosed with mild-to-moderate idiopathic PD (Stage I–III on the Modified Hoehn and Yahr Scale) [

17], were recruited from the Hospital Research Foundation Parkinson’s, South Australia, a community organisation providing support services to individuals living with PD. Participants were recruited for a 48-week long prospective, randomised controlled crossover pilot trial. Participants were randomised into four intervention sequences (n = 5 per sequence): A–B–C–D, B–D–A–C, C–A–D–B, and D–C–B–A, where A = PBM, B = AE, C = PBM + AE, and D = sham. Each intervention lasted 8 weeks, was center-based and supervised, and was followed by a 4-week washout. All participants provided written informed consent prior to their participation.

2.2. PBM and SHAM Protocol

The PBM intervention targeted the head, abdomen, and neck using the PDNeuro light-emitting diode (LED) helmet and a hand-held PDCare Laser device (SYMBYX Biome, NSW, Australia). Head PBM was delivered twice weekly during weeks 1–4 and three times weekly during weeks 5–8, scheduled consistently during their “on” medication phase (~1–1.5 h post-dose), at 40 Hz for 12 minutes at 670 nm (red) followed by 12 minutes at 810 nm (near-infrared). Simultaneously, the PDCare Laser was applied to nine abdominal sites (2 minute each, 18 minutes total) and the posterior neck at C1–C2 (1 minute each, 2 minutes total), providing 64.8 J (abdomen) and 7.2 J (neck). The sham intervention used identical procedures with inactive devices, and no AE was performed.

2.3. Aerobic Exercise

AE sessions were supervised by Accredited Exercise Scientists/Accredited Exercise Physiologists and followed a modified Pedalling for Parkinson’s forced-rate cycling protocol on a stationary bike [

18]. Each session included a 10-minute warm-up, 40 minutes of forced-rate cycling at 80–90 rpm at a target intensity of 60–80% of maximum heart rate or a Borg rate of perceived exertion rating of 4–7 (“somewhat hard” to “very hard”), and a 10-minute cooldown [

19]. Sessions occurred twice weekly in weeks 1–4 and three times weekly in weeks 5–8, during participants’ “ON” medication phase (~1–1.5 h post-dose).

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Participants were 47–85 years old with a confirmed diagnosis of idiopathic PD by a neurologist (Modified Hoehn and Yahr Stage I–III) and sufficient mobility to safely participate in AE programme. Exclusion criteria targeted factors that could compromise safety, affect motor function or intervention response, or limit outcome interpretation. These included: (1) cognitive impairment defined as <24 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [

20]; (2) history of other neurological disease (i.e. stroke, seizures in the past year, or migraine with aura); (3) uncontrolled or unstable cardiovascular disease including heart arrhythmia, uncontrolled blood pressure, postural orthodontic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), orthostatic dysautonomia or orthostatic intolerance; (4) history of significant psychiatric condition (i.e. schizophrenia, bi-polar disorder, psychotic episodes or suicide ideations in the past 12 months); (5) other uncontrolled or unstable medical illness (i.e. renal, gastrointestinal, terminal cancer); (6) currently participating in other research studies; (7) taking photosensitive medications (imipramine, hypericum, phenothiazine, lithium, chloroquine, hydrochlorothizide, tetracycline); (8) taking corticosteroids or consistent use of anti-inflammatory medication (>2 times/day); (9) history of significant musculoskeletal disorders (arthritis or orthopaedic injury); (10) currently using any form of light therapy or deep brain stimulation; (11) significant vision impairment (visual acuity ≤ 6/120); (12) presence of age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, optic neuropathy, or other retinal pathologies; (13) multiple sclerosis, or other demyelinating central nervous system disease affecting retinal nerve fibres; and (14) significant cataract, refractive error, or any other eye condition preventing reliable ocular imaging.

2.5. Procedure for Ocular Measurements

The present analysis focused specifically on ocular and functional measures collected at baseline prior to the first intervention (pre- intervention) and after completion of all four intervention sequences (post- intervention). All pre- and post- intervention assessments were conducted at the Flinders University Health2Go Clinic in Adelaide, South Australia, with ocular data collected by an experienced optometrist.

2.6. Outcome Measures

2.6.1. Visual Function

Distance logMAR visual acuity (VA) was measured monocularly using a standard computerised high-contrast logMAR chart at 6 meters (Zeiss Visuscreen version 2.9, Carl Zeiss Vision GmbH, Aalen, Germany), with the fellow eye occluded. Contrast sensitivity was then assessed monocularly using a Hi-Lo LogMAR chart at 3 meters. All testing was performed under standard room illumination of about 500 lux with participants wearing their habitual correction.

2.6.2. Intraocular Pressure

Intraocular pressure (IOP) was measured in both eyes using rebound tonometry Icare ic200 (Icare Finland Oy), with the mean of six readings per eye recorded. The device was calibrated and used according to manufacturer guidelines [

21]. Goldmann applanation tonometry was performed only if iCare readings exceeded 21 mmHg, as it was not tolerated by all participants.

2.6.3. Retinal Nerve Fibre Layer and Choroidal Thickness

The Cirrus high definition (HD) spectral domain OCT was used for choroidal thickness and RNFL measurements (Cirrus HD- OCT 5000, Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc, Dublin, CA). For OCT imaging, pupils were dilated using 0.5% tropicamide, and ocular imaging was performed 30 minutes after confirmation of full pupillary dilation [

22]. Peripapillary (i.e., around the optic nerve) RNFL thickness at the optic nerve head was measured using a single Optic Disc Cube 200×200 scan protocol, while choroidal thickness was assessed using a single fovea-centred HD raster scan with enhanced depth imaging [

23]. Choroidal thickness was measured at the macula, defined as the distance from the retinal pigment epithelium to the inner choroid–scleral boundary, using the proprietary Zeiss Forum platform by a trained examiner masked to intervention status. Scans with signal strength <6/10 or motion artefacts were excluded and repeated, as needed.

2.6.4. Retinal Microvasculature

Vascular perfusion at the macula was measured using the Angioplex OCT-A module on the Cirrus HD-OCT 5000 device. A single 3 × 3 mm scan centred at the fovea was acquired for each eye. Perfusion in the superficial retinal capillary plexus was measured at the central macular zone and across the four quadrants (superior, inferior, nasal, temporal) based on the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) grid sectors (

Figure S1) [

23,

24]. Images were inspected for segmentation accuracy and the presence of motion artefacts due to eye movements were repeated if necessary.

2.6.5. Subjective Questionnaires on QoL, functional Capacity, and Falls Risk

Participants completed three validated self-report questionnaires to assess the impact of non-pharmacological interventions on QoL, functional capacity, and falls risk: the 12-item Short Form Survey (SF-12), the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39), and the Falls Efficacy Scale–International (FES-I). From the SF-12 questionnaire, the mental component summary score (MCS-12) and the physical component summary score (PCS-12) were derived using an online score calculator (Cronbach’s α = 0.82-0.87) [

25,

26], as described previously [

27]. The PDQ-39 evaluates QoL across multiple domains in PD (Cronbach’s α = 0.66–0.95) [

28], and the FES-I assesses fear of falling (Cronbach’s α = 0.96–0.98) [

29]. Questionnaires were completed electronically on the same day as ocular assessments, pre- and post- intervention.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 26.0,

ibm.com/au-en), with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± SEM unless stated otherwise. Right and left eye measurements were averaged for ocular parameters. Changes in visual function, choroidal thickness, RNFL thickness, and IOP pre- and post-intervention were analysed using paired t-tests, or Wilcoxon signed rank test where the data failed normality. For the OCT-A analysis, vascular perfusion values from the inner and outer zones were averaged within each quadrant (

Figure S1). Changes in retinal vascular perfusion was analysed using two-way repeated measures ANOVA and Holm–Sidak post-hoc tests for statistical significance, with ‘zone’ and ‘pre- and post-intervention’ as within-subjects factors. Paired t-tests were also used to assess pre- to post- intervention differences in QoL measures, including PDQ-39 (eight domains and summary index score), SF-12 (PCS-12 and MCS-12), and FES-I.

3. Results

3.1. Visual Function, IOP and OCT

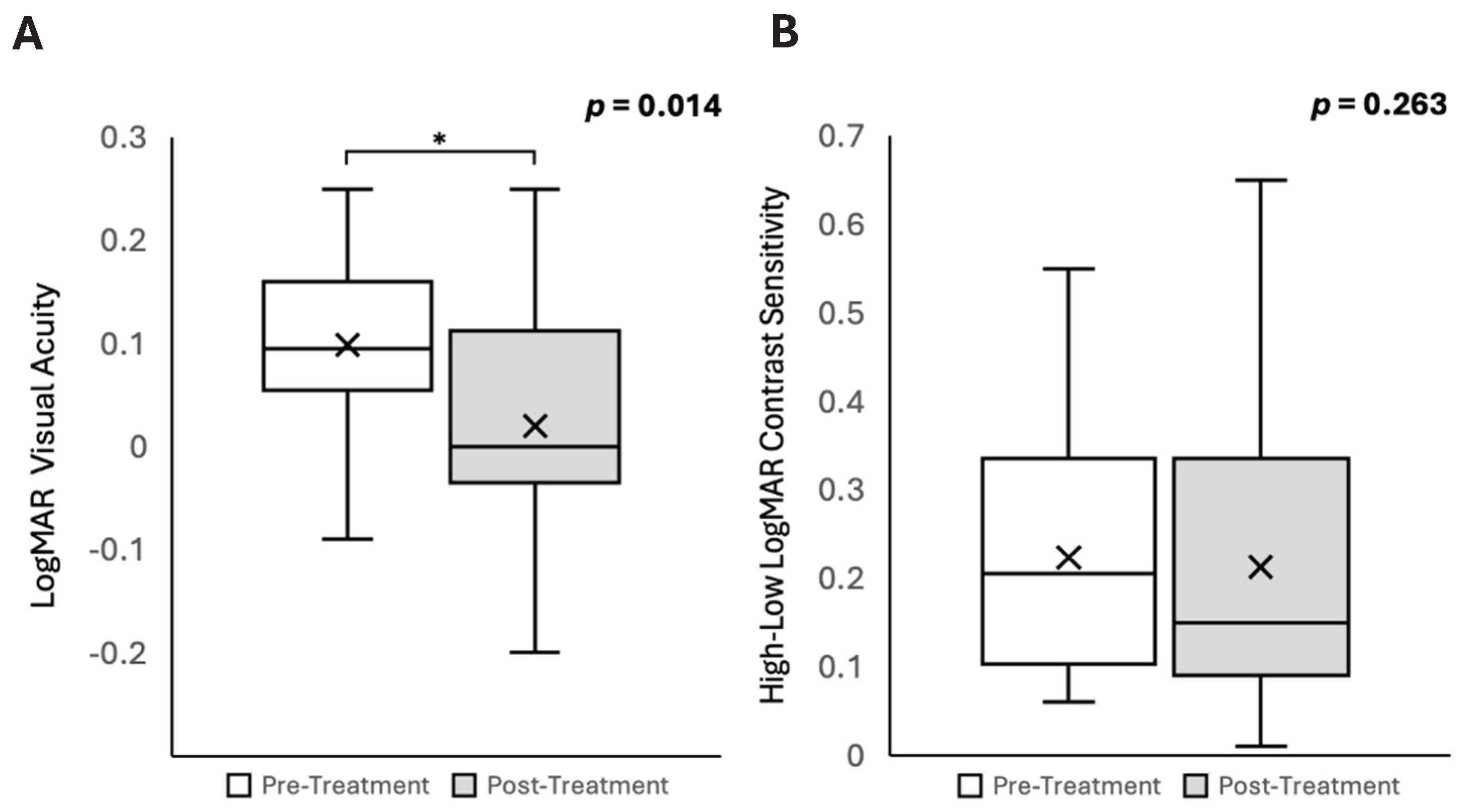

Data from three participants could not be collected: one due to significant bilateral cataracts, one due to bilateral age-related macular degeneration, and one who was unable to undergo ocular imaging due to pronounced resting tremors. Seventeen participants who completed all measurements were included in the final analysis. Non-pharmacological interventions resulted in a significant improvement in VA in patients with PD (mean logMAR VA, pre- intervention, 0.10 ± 0.02; post- intervention, 0.02 ± 0.03, t[df 17] = 2.74, p = 0.014;

Table 1 and

Figure 1A). There were no significant changes in contrast sensitivity (pre- intervention, 0.22 ± 0.04; post- intervention, 0.19 ± 0.04; p = 0.263;

Figure 1B) or IOP (pre- intervention, 16 ± 1 mmHg; post- intervention, 15 ± 1 mmHg; p = 0.090;

Table 1) associated with the intervention.

Similarly, no significant changes were observed in choroidal thickness (pre- intervention, 206.17 ± 7.85 μm; post- intervention, 222.00 ± 7.84 μm; p = 0.08) or RNFL (pre- intervention, 88.80 ± 3.49 μm; post- intervention, 88.40 ± 3.58 μm; p = 0.724;

Table 1).

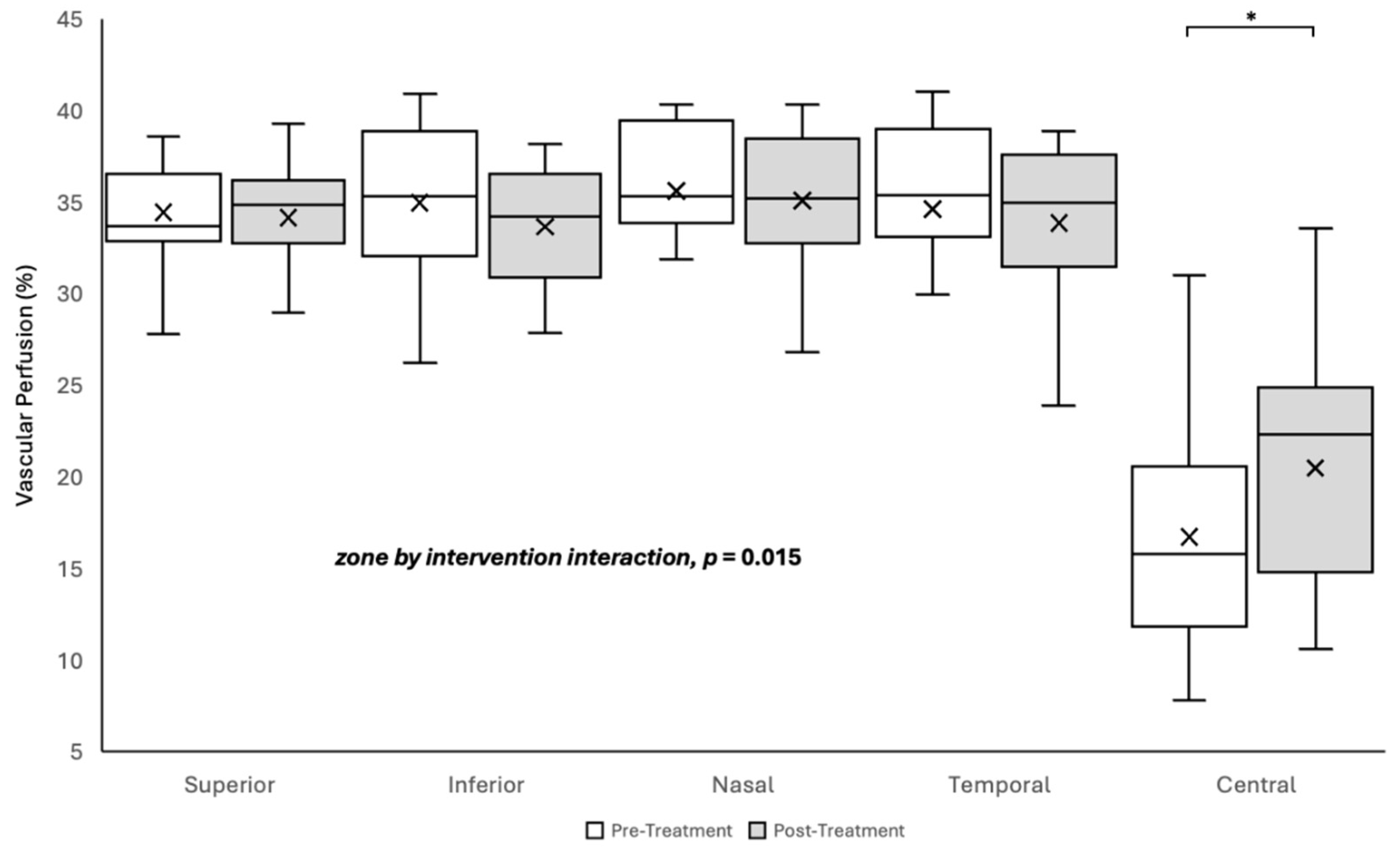

3.2. Vascular Perfusion

The change in vascular perfusion or blood flow following the intervention varied significantly by retinal zone (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, zone by intervention interaction F [4, 159] = 3.385; p = 0.015). The Holm-Sidak post-hoc test revealed a 22% increase in retinal perfusion in the central zone only (pre- intervention 16.75 ± 1.38%; post- intervention 20.49 ± 1.63%; p = 0.002), with no significant changes observed in the superior, inferior, nasal, or temporal quadrants (all p > 0.05;

Figure 2).

3.3. PDQ-39, SF-12 and FES-I

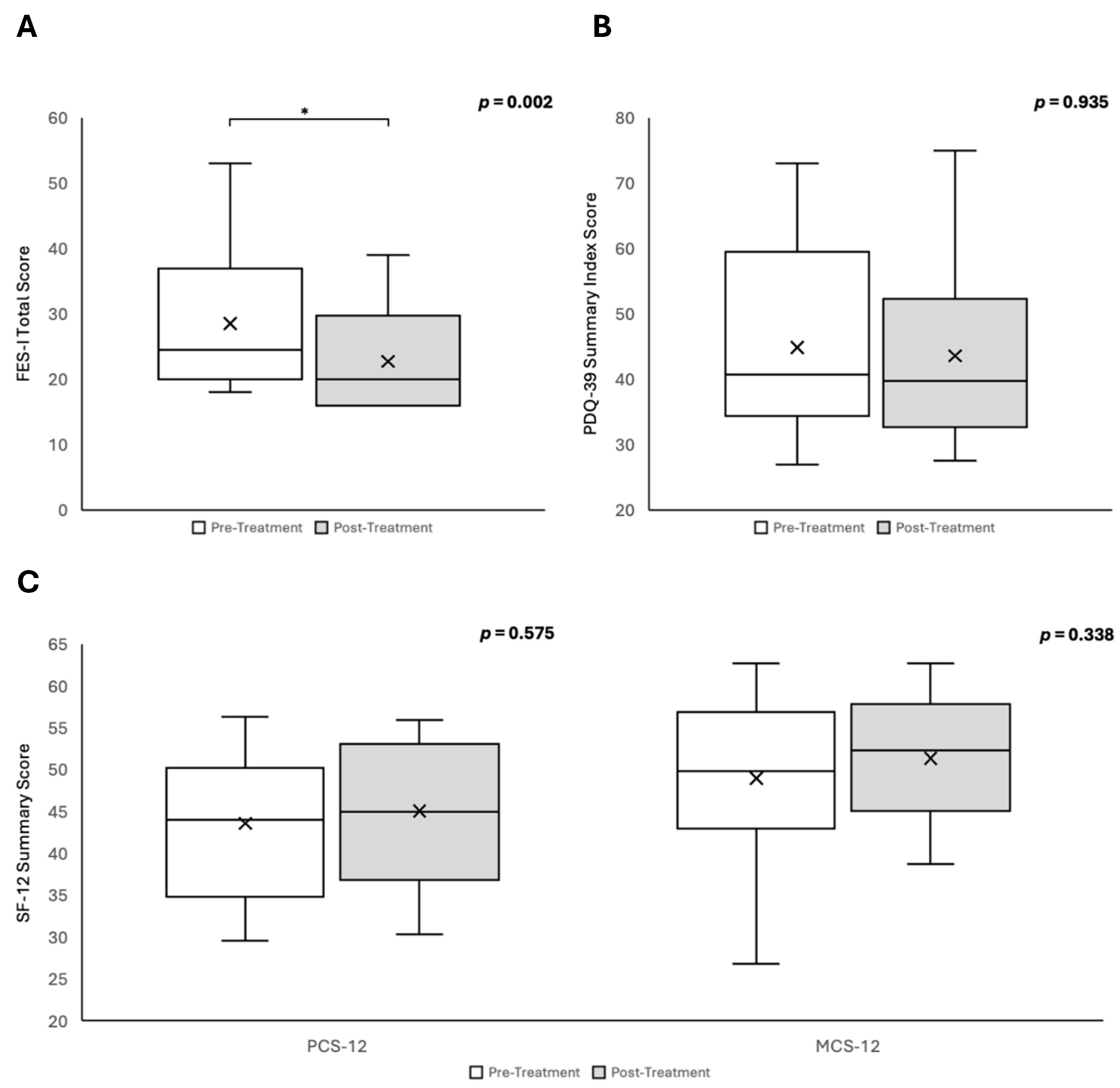

The impacts on QoL, as assessed by the PDQ-39, SF-12, and FES-I, are summarised in

Figure 3. There was a significant reduction in fear of falling following the intervention, as evidenced by a decrease in the FES-I score (pre-intervention: 28.50; post-intervention: 22.72; Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 0.002;

Figure 3A). There were no statistically significant changes observed across any of the eight PDQ-39 domains or in the PDQ-39 summary index score (all p > 0.05;

Figure 3B). Similarly, no significant changes were detected in either the physical or mental component summary scores of the SF-12 questionnaire (both p > 0.05;

Figure 3C).

4. Discussion

PD is characterised by progressive motor and sensory impairments, including visual deficits such as reduced VA, impaired contrast sensitivity, and visuospatial difficulties leading to a reduced QoL [

4,

5,

13,

14,

15]. These visual deficits likely result from Parkinson’s-related dysfunction of retinal pathways, including dopaminergic depletion, α-synuclein–induced neurodegeneration, increased retinal neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, and impaired microvascular regulation affecting retinal perfusion [

13,

14,

15,

16,

30]. In this crossover study, PBM and AE, administered alone or in combination, were associated with improvements in VA, increased retinal vascular perfusion, and reduced fear of falling, suggesting potential independent and/or synergistic effects of PBM and AE on visual and functional outcomes. This analysis was exploratory and derived from a larger multidisciplinary randomised pilot trial; therefore, it was not designed or intended to disentangle the independent effects of each intervention.

We found an approximate one-line improvement in logMAR VA, reflecting a statistically and clinically significant improvement in visual function post- intervention. While the underlying mechanism remains unclear, both PBM and AE are known to slow disease progression and preserve visual function in age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and retinitis pigmentosa, likely via reduction of retinal oxidative stress and neuroinflammation [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

Another important finding was a significant increase in vascular perfusion within the central macular zone following the intervention, indicating that non-pharmacological approaches may enhance retinal blood flow in people with PD, potentially counteracting microvascular dysfunction and supporting overall retinal vascular health [

16,

41]. The preferential sensitivity of the central retina to PBM or AE remains unclear; however, the observed increase in retinal perfusion occurred in the absence of changes in choroidal thickness or IOP, suggesting an early microvascular adaptation independent of IOP-related influences [

16,

42]. Evidence from neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease and traumatic brain injury, demonstrates that PBM can enhance blood flow by reducing oxidative stress and promoting nitric oxide (NO) mediated vasodilation through light-induced NO photorelease from haemoglobin [

43,

44,

45]. Given the retina’s embryological and functional continuity with the central nervous system, similar NO-dependent mechanisms may underlie the observed increase in retinal vascular perfusion [

46]. Similarly, AE improves vascular perfusion by enhancing endothelial function and NO bioavailability, supporting microvascular autoregulation and vasodilation [

9,

10,

47,

48]. Together, these findings suggest that PBM and AE may increase retinal vascular perfusion through overlapping mechanisms involving NO signalling, mitochondrial function, and vascular autoregulation, although further work is required to delineate their individual and combined contributions [

49,

50].

Fear of falling is a common and disabling concern among individuals with PD [

51]. In the present study, fear of falling decreased significantly following the intervention, suggesting meaningful functional gains and improved confidence, likely driven by enhanced balance and gait associated with improvements in visual function and ocular health [

52,

53].

Notably, the PDQ-39 summary index and SF-12 scores showed no significant change in QoL, although small trends toward improvement were observed in the PDQ-39 cognition and bodily discomfort domains (data not shown). Several factors may account for this dissociation. First, these patient-reported outcome measures are known to be more responsive to QoL changes in later stages of PD, which may have limited their sensitivity to detect subtle benefits in the mild-to-moderate PD cohort for this study [

54]. Second, modest QoL effects associated with the non-pharmacological interventions may not have been detected due to the pre–post study design, which limits sensitivity to small, intervention-specific changes. Third, the eight-week duration of PBM, AE, and PBM + AE interventions may have been insufficient to elicit measurable improvements in QoL, which often evolve over longer intervention periods. In this study, head PBM was administered 2-3 times per week for eight weeks; however, previous studies have reported significant improvements in clinical outcomes of PD following at least 12 weeks of PBM [

55], with sustained use being associated with greater benefits to QoL [

56]. Similarly, AE interventions comparable to those employed here generally demonstrate greater QoL benefits when sustained for 12 weeks or longer in individuals with mild-to-moderate PD [

57,

58], although not all AE interventions show large changes in QoL measured by PDQ-39 [

10]. Future studies with larger sample sizes, longer intervention durations, and stratification by disease severity are warranted to more comprehensively evaluate the impact of non-pharmacological interventions on QoL in PD.

Although our study yielded some significant findings, it had several limitations. The main limitation of this preliminary exploratory analysis was that all ocular and questionnaire data were collected only at baseline (pre- intervention) and at the end of the 48-week study period (post- intervention). As all participants underwent each of the four intervention conditions (PBM, AE, PBM + AE, and sham), the pre–post study design precluded attribution of observed effects to any specific intervention or to their combined effects. The relatively small sample size (n = 20) limits the generalisability of the findings to the broader PD population. Furthermore, some participants (n = 3) were unable to complete all ocular assessments, which further reduced the statistical power for the associated outcome measures. Future studies should adopt a more systematic design incorporating repeated measurements before and after each intervention phase, along with larger sample sizes, to better elucidate the effects of PBM and AE on ocular and functional outcomes in PD.

In conclusion, PBM, either alone or in combination with AE, was associated with significant improvements in vision and central retinal vascular perfusion, alongside a reduction in fear of falling in individuals with PD. However, as the study design did not allow attribution of these effects to PBM, AE, or their combined application, larger-scale, controlled trials are required to delineate the independent and synergistic contributions of each intervention.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Example of a 3 x 3 mm optical coherence tomography-angiograpy (OCT-A) scan.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.R. and R.C.; methodology, R.C. and J.F.; validation, J.F., J.C., D.H., L.T. and C.L.; formal analysis, R.C., J.F. and J.C.; investigation, J.F., J.C., D.H., L.T. and C.L.; resources, J.S.R. and O.N.; data curation, R.C. and J.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F., J.C., and R.C.; writing—review and editing, J.F., J.S.R., J.C., D.H., L.T., C.L., J.D., O.N., A.B., L.D., M.K., R.C.; visualization, J.F.; supervision, J.S.R. and R.C.; project administration, O.N., J.S.R., R.C. and J.D.; funding acquisition, J.S.R. and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC were funded by The Hospital Research Foundation, grant number 2022-S-EOI-001-83100.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Flinders University Human Research Ethics Committee (Flinders HREC, ID: 5709, date of approval 16/11/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s). The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the administrative staff of the Flinders University Health2GO clinic for their help with patient management and scheduling of appointments during the study. .

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PD |

Parkinson’s disease |

| PBM |

Photobiomodulation therapy |

| AE |

Aerobic exercise |

| QoL |

Quality of life |

| VA |

Visual acuity |

| IOP |

Intra ocular pressure |

| RNFL |

Retinal nerve fibre layer |

| SF-12 |

12-item Short Form Survey |

| FES-I |

Falls Efficacy Scale-International |

| PDQ-39 |

39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire |

| MCS-12 |

Mental Component Summary Score |

| PCS-12 |

Physical Component Summary Score |

| ETDRS |

Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study |

| OCT |

Optical Coherence Tomography |

| OCT-A |

Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography |

| HD |

High definition |

| LED |

Light-emitting diode |

| POTS |

Postural orthodontic tachycardia syndrome |

| MoCA |

Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| NO |

Nitric oxide |

References

- Poewe, W.; Seppi, K.; Tanner, C.M.; Halliday, G.M.; Brundin, P.; Volkmann, J.; Schrag, A.E.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3, 17013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Cui, Y.; He, C.; Yin, P.; Bai, R.; Zhu, J.; Lam, J.S.T.; Zhang, J.; Yan, R.; Zheng, X.; et al. Projections for prevalence of Parkinson's disease and its driving factors in 195 countries and territories to 2050: modelling study of Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Bmj 2025, 388, e080952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohingamu Mudiyanselage, S.; Watts, J.J.; Abimanyi-Ochom, J.; Lane, L.; Murphy, A.T.; Morris, M.E.; Iansek, R. Cost of Living with Parkinson's Disease over 12 Months in Australia: A Prospective Cohort Study. Parkinsons Dis 2017, 2017, 5932675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, M.J.; Okun, M.S. Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson Disease: A Review. Jama 2020, 323, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, J.; Tan, E.K. Parkinson's disease: etiopathogenesis and treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2020, 91, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamblin, M.R. Photobiomodulation or low-level laser therapy. J Biophotonics 2016, 9, 1122–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felician, M.; Belotto, R.; Tardivo, J.; Baptista, M.; Martins, W. Photobiomodulation: Cellular, molecular, and clinical aspects. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology 2023, 17, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicknell, B.; Liebert, A.; Herkes, G. Parkinson's Disease and Photobiomodulation: Potential for Treatment. J Pers Med 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schootemeijer, S.; van der Kolk, N.M.; Bloem, B.R.; de Vries, N.M. Current Perspectives on Aerobic Exercise in People with Parkinson's Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17, 1418–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, K.; Zhang, S.; Tao, X.; Li, G.; Lv, Y.; Yu, L. A systematic review and meta-analysis on effects of aerobic exercise in people with Parkinson's disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2022, 8, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, L.F.; Hamblin, M.R. Proposed Mechanisms of Photobiomodulation or Low-Level Light Therapy. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron 2016, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eluamai, A.; Brooks, K. Effect of aerobic exercise on mitochondrial DNA and aging. Journal of Exercise Science & Fitness 2013, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, R.S.; Schrag, A.E.; Warren, J.D.; Crutch, S.J.; Lees, A.J.; Morris, H.R. Visual dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Brain 2016, 139, 2827–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, Y.; Grover, R. Ocular disorders in Parkinson’s disease: A review. Journal of Clinical Ophthalmology and Research 2024, 12, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.A. Visual symptoms in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsons Dis 2011, 2011, 908306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilgin, Ş.; Uysal, H.A.; Bilgin, S.; Yaka, E.C.; Küsbeci Ö, Y.; Şener, U. Assessment of Changes in Vascular Density in the Layers of the Eye in Patients With Parkinson's Disease. Ann Neurosci 2024, 09727531241259841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehn, M.M.; Yahr, M.D. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 1967, 17, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, K.E.; Johnson, R.K.; Chan, J.; Wills, A.M. Implementation of high-cadence cycling for Parkinson's disease in the community setting: A pragmatic feasibility study. Brain Behav 2021, 11, e02053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G.A. Perceived exertion: a note on "history" and methods. Med Sci Sports 1973, 5, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iCare IC200 Instruction Manual. Available online: https://materialbank.icare-world.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/iCare_IC200_instruction_manual_TA031-046-EN-5.0.pdf?mtime=1687243513;2023 (accessed on 03/10/2025).

- Smith, M.; Frost, A.; Graham, C.M.; Shaw, S. Effect of pupillary dilatation on glaucoma assessments using optical coherence tomography. Br J Ophthalmol 2007, 91, 1686–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, A.; Ma, J.P.; Robbins, C.B.; Pant, P.; Gunasan, V.; Agrawal, R.; Stinnett, S.; Scott, B.L.; Moore, K.P.L.; Fekrat, S.; et al. Longitudinal Analysis of Retinal Microvascular and Choroidal Imaging Parameters in Parkinson's Disease Compared with Controls. Ophthalmol Sci 2023, 3, 100393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, O.; Hajdu, D.; Jeney, A.; Czifra, B.; Nagy, B.V.; Balazs, T.; Nemoda, D.J.; Somfai, G.M.; Nagy, Z.Z.; Peto, T.; et al. Qualitative and quantitative comparison of two semi-manual retinal vascular density analyzing methods on optical coherence tomography angiography images of healthy individuals. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 16981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SF-12 - OrthoToolKit. Available online: https://orthotoolkit.com/ (accessed on 03/10/2025).

- Montazeri, A.; Vahdaninia, M.; Mousavi, S.J.; Asadi-Lari, M.; Omidvari, S.; Tavousi, M. The 12-item medical outcomes study short form health survey version 2.0 (SF-12v2): a population-based validation study from Tehran, Iran. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanatos, L.; Sandean, D.P.; Burgula, M.; Lee, B.; Pandey, R.; Singh, H.P. Use of patient reported experience measure and patient reported outcome measures to evaluate differences in surgical or non-surgical management of humeral shaft fractures. Shoulder Elbow 2023, 15, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peto, V.; Jenkinson, C.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Greenhall, R. The development and validation of a short measure of functioning and well being for individuals with Parkinson's disease. Qual Life Res 1995, 4, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadeh, M.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Habibi, S.A.; Fereshtehnejad, S.M.; Abasi, A.; Niazi Khatoon, J.; Saneii, S.H.; Taghizadeh, G. Reliability and Validity of Fall Efficacy Scale-International in People with Parkinson's Disease during On- and Off-Drug Phases. Parkinsons Dis 2019, 2019, 6505232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, M.D.; Aishwarya Janaki, P.; Abishek Kumar, B.; Gopalarethinam, J.; Nair, A.P.; Mahalaxmi, I.; Vellingiri, B. Retinal Changes in Parkinson's Disease: A Non-invasive Biomarker for Early Diagnosis. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2023, 43, 3983–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munk, M.R.; Rückert, R. Photobiomodulation (PBM) therapy: emerging data and potential for the treatment of non neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Expert Review of Ophthalmology 2024, 19, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaymak, H.; Munk, M.R.; Tedford, S.E.; Croissant, C.L.; Tedford, C.E.; Ruckert, R.; Schwahn, H. Non-Invasive Treatment of Early Diabetic Macular Edema by Multiwavelength Photobiomodulation with the Valeda Light Delivery System. Clin Ophthalmol 2023, 17, 3549–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, R.C. Photobiomodulation Using Light-Emitting Diode (LED) for Treatment of Retinal Diseases. Clin Ophthalmol 2024, 18, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo, M.; Smith, O.; Trubnik, V.; Reiss, G. Interventional glaucoma and the patient perspective. Expert Review of Ophthalmology 2024, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, G.F.; Munk, M.R.; Dotson, R.S.; Walker, M.G.; Devenyi, R.G. Photobiomodulation reduces drusen volume and improves visual acuity and contrast sensitivity in dry age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol 2017, 95, e270–e277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valter, K.; Tedford, S.E.; Eells, J.T.; Tedford, C.E. Photobiomodulation use in ophthalmology - an overview of translational research from bench to bedside. Front Ophthalmol (Lausanne) 2024, 4, 1388602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.C.; Pountney, D.L.; Khoo, T.K. Therapeutic Mechanisms of Exercise in Parkinson's Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.H.; Lee, Y. Association of Exercise Intensity with the Prevalence of Glaucoma and Intraocular Pressure in Men: A Study Based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleimani, A.; Soltani, P.; Karimi, H.; Mirzaei, M.; Esfahanian, F.; Yavari, M.; Esfahani, M.P. The effect of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise on non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy in type II diabetes mellitus patients: A clinical trial. Microvasc Res 2023, 149, 104556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.T. Prospective study of incident age-related macular degeneration in relation to vigorous physical activity during a 7-year follow-up. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009, 50, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, X.; Guo, J.; Xu, H.; Tang, B.; Jiao, B.; Shen, L. Retinal Microvascular Density Was Associated With the Clinical Progression of Parkinson's Disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 818597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, H.; Mercieca, K.; Prinz, J.; Feng, Y.; Prokosch, V. The Association between Vascular Abnormalities and Glaucoma-What Comes First? Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blivet, G.; Touchon, B.; Cavadore, H.; Guillemin, S.; Pain, F.; Weiner, M.; Sabbagh, M.; Moro, C.; Touchon, J. Brain photobiomodulation: a potential treatment in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2025, 12, 100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapchak, P.A. Transcranial near-infrared laser therapy applied to promote clinical recovery in acute and chronic neurodegenerative diseases. Expert Rev Med Devices 2012, 9, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viggiano, P.; Boscia, G.; Clemente, A.; Laterza, M.; Termite, A.C.; Pignataro, M.G.; Salvelli, A.; Borrelli, E.; Reibaldi, M.; Giannaccare, G.; et al. Photobiomodulation-induced choriocapillaris perfusion enhancement and outer retinal remodelling in intermediate age-related macular degeneration: a promising therapeutic approach with short-term results. Eye (Lond) 2025, 39, 2057–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London, A.; Benhar, I.; Schwartz, M. The retina as a window to the brain-from eye research to CNS disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 2013, 9, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, L.Y.; Bechara, L.R.; dos Santos, A.M.; Jordão, C.P.; de Sousa, L.G.; Bartholomeu, T.; Ventura, L.I.; Laurindo, F.R.; Ramires, P.R. Exercise improves endothelial function: a local analysis of production of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. Nitric Oxide 2015, 45, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, D.M.; Copp, S.W.; Ferguson, S.K.; Holdsworth, C.T.; McCullough, D.J.; Behnke, B.J.; Musch, T.I.; Poole, D.C. Exercise training and muscle microvascular oxygenation: functional role of nitric oxide. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2012, 113, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ezzdine, L.; Dhahbi, W.; Dergaa, I.; Ceylan, H.; Guelmami, N.; Ben Saad, H.; Chamari, K.; Stefanica, V.; El Omri, A. Physical activity and neuroplasticity in neurodegenerative disorders: a comprehensive review of exercise interventions, cognitive training, and AI applications. Front Neurosci 2025, 19, 1502417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keszler, A.; Lindemer, B.; Broeckel, G.; Weihrauch, D.; Gao, Y.; Lohr, N.L. In Vivo Characterization of a Red Light-Activated Vasodilation: A Photobiomodulation Study. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 880158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonasson, S.; Nilsson, M.; Lexell, J.; Carlsson, G. Experiences of fear of falling in persons with Parkinson's disease - A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, U.E.; Black, A.A.; Wood, J.M.; Delbaere, K. Fear of falling in vision impairment. Optom Vis Sci 2015, 92, 730–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud Ali Ibrahim, A.; Abou El-soued Hussein Ahmed, H. Relationship between Visual Functioning, Balance, and Fear of Falling among Community-dwelling seniors with Cataract. Egyptian Journal of Health Care 2023, 14, 807–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagell, P.; Nygren, C. The 39 item Parkinson's disease questionnaire (PDQ-39) revisited: implications for evidence based medicine. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007, 78, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebert, A.; Bicknell, B.; Laakso, E.L.; Heller, G.; Jalilitabaei, P.; Tilley, S.; Mitrofanis, J.; Kiat, H. Improvements in clinical signs of Parkinson's disease using photobiomodulation: a prospective proof-of-concept study. BMC Neurol 2021, 21, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebert, A.; Bicknell, B.; Laakso, E.L.; Tilley, S.; Heller, G.; Kiat, H.; Herkes, G. Improvements in clinical signs and symptoms of Parkinson's disease using photobiomodulation: a five-year follow-up. BMC Neurol 2024, 24, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Tan, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y. Effect of Exercise on Quality of Life in Parkinson's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Parkinsons Dis 2020, 2020, 3257623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uc, E.Y.; Doerschug, K.C.; Magnotta, V.; Dawson, J.D.; Thomsen, T.R.; Kline, J.N.; Rizzo, M.; Newman, S.R.; Mehta, S.; Grabowski, T.J.; et al. Phase I/II randomized trial of aerobic exercise in Parkinson disease in a community setting. Neurology 2014, 83, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).