Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

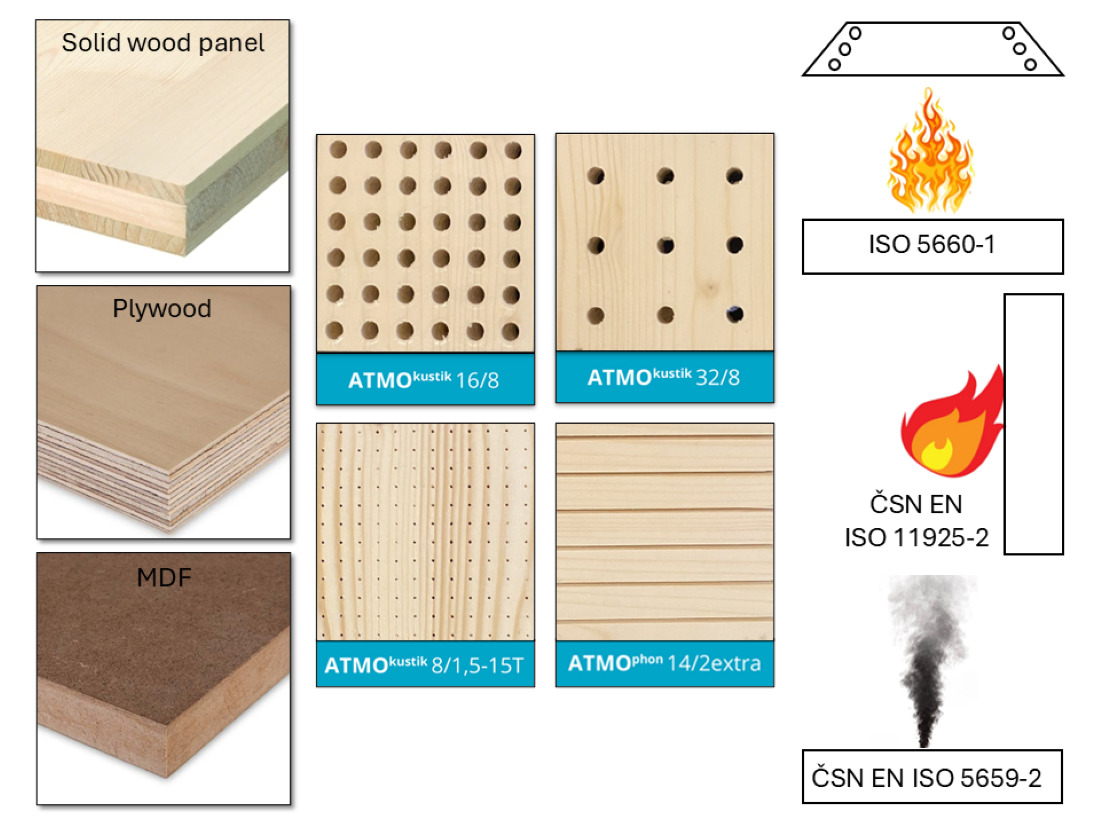

2. Materials and Methods

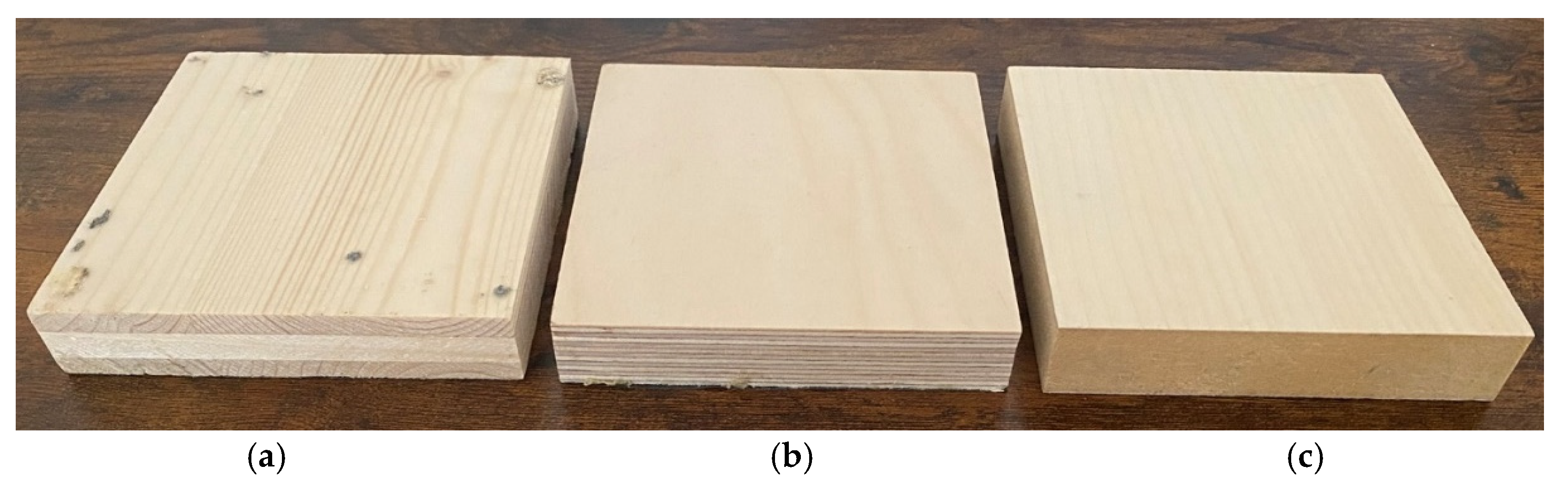

- a three-layer B/C spruce solid wood panel with a thickness of 19.4 mm,

- a 13-layer birch plywood with a thickness of 18.1 mm, and

- an MDF board with a thickness of 19.2 mm, which was veneered on the face surface with ash veneer.

Methods

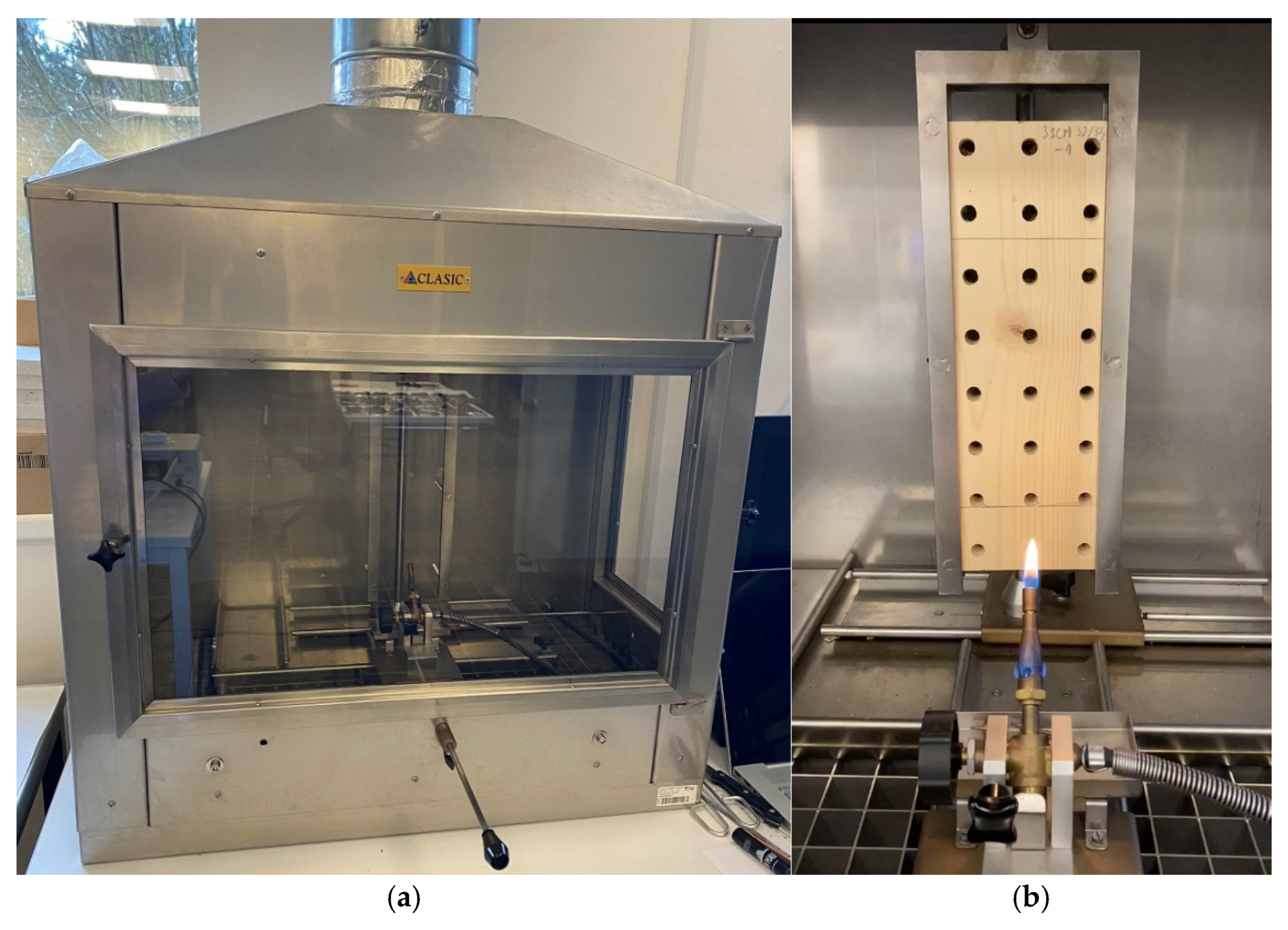

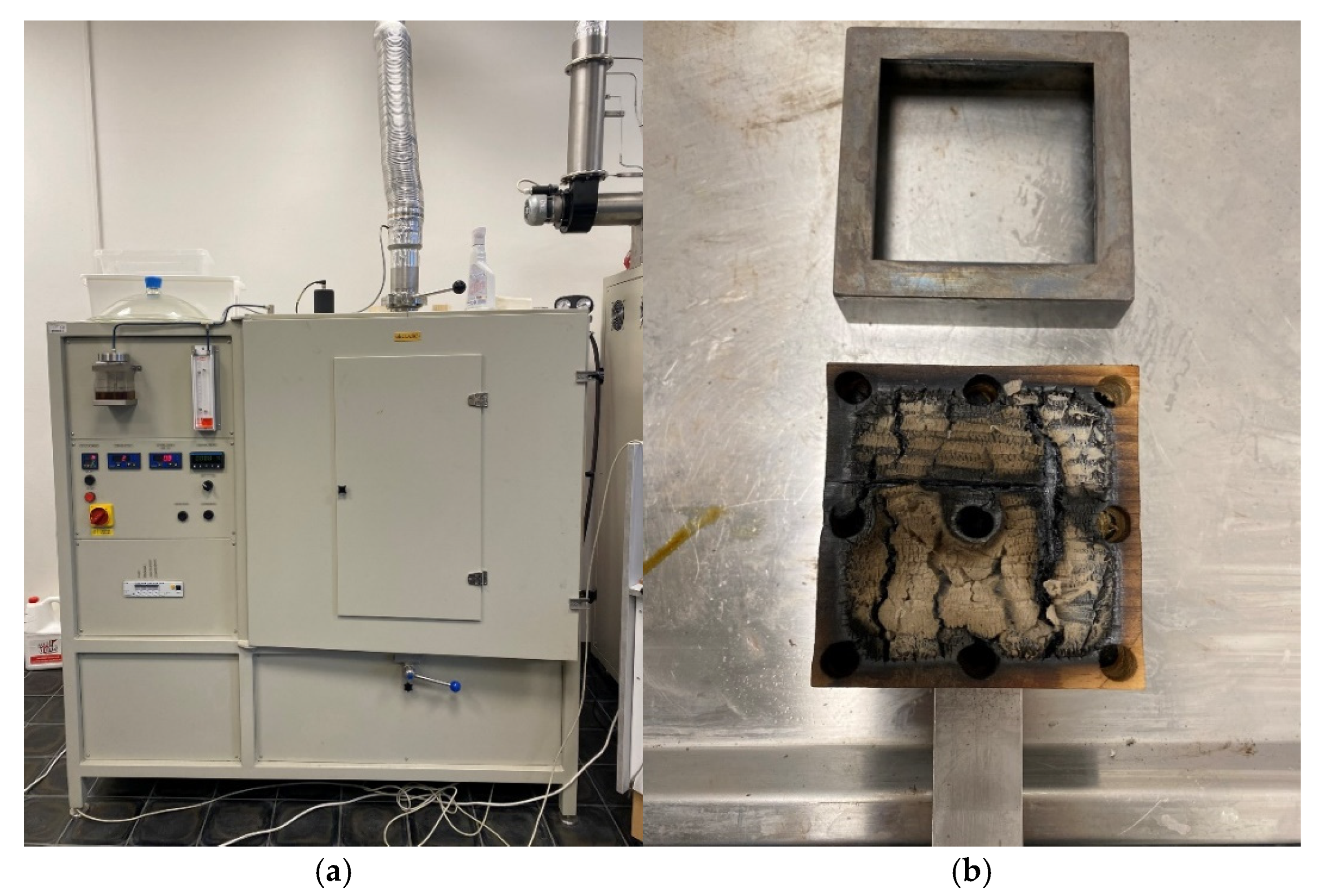

Cone Calorimeter Method

Single-Flame Source Test

Smoke Generation - Determination of Optical Density

Statistical Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

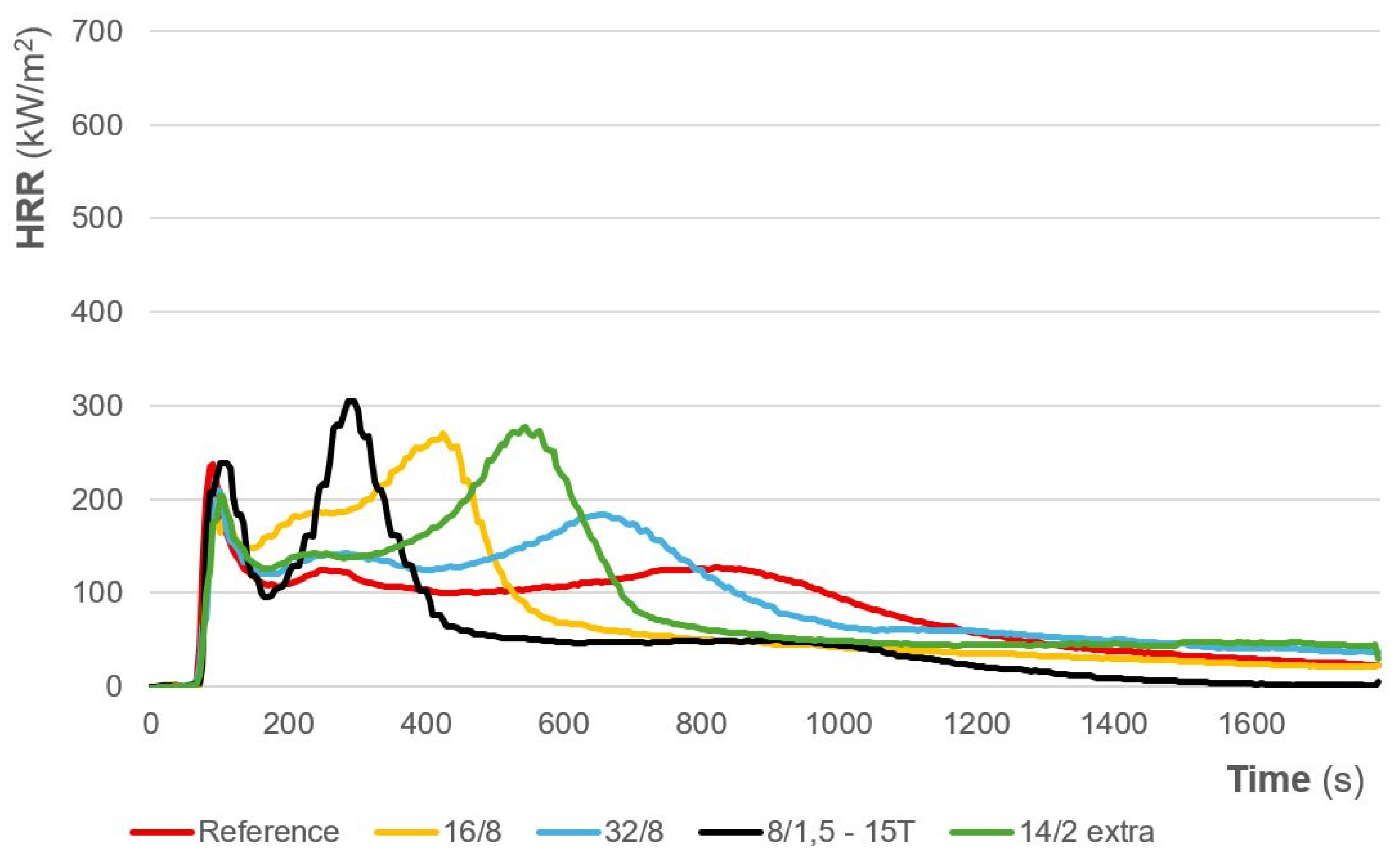

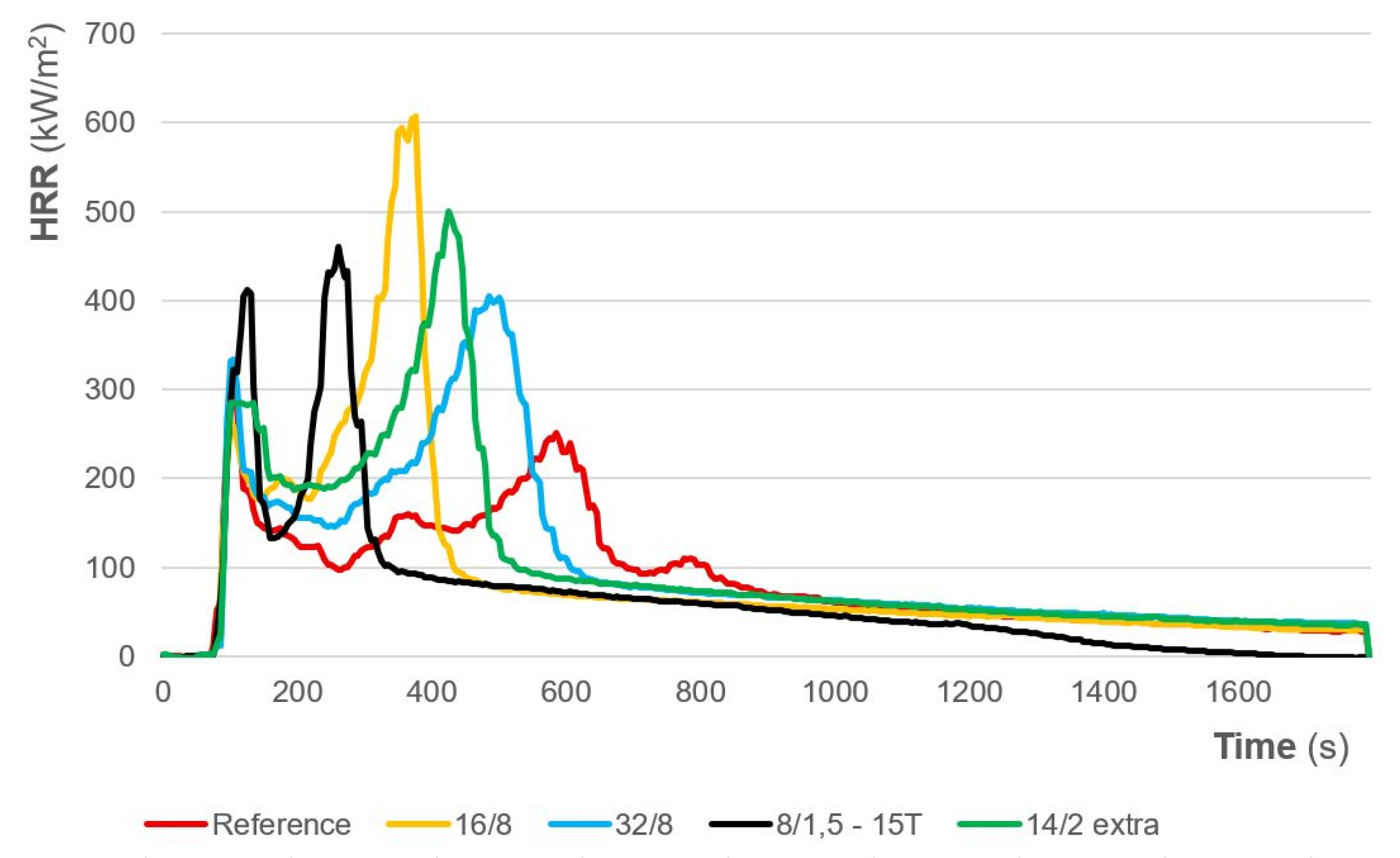

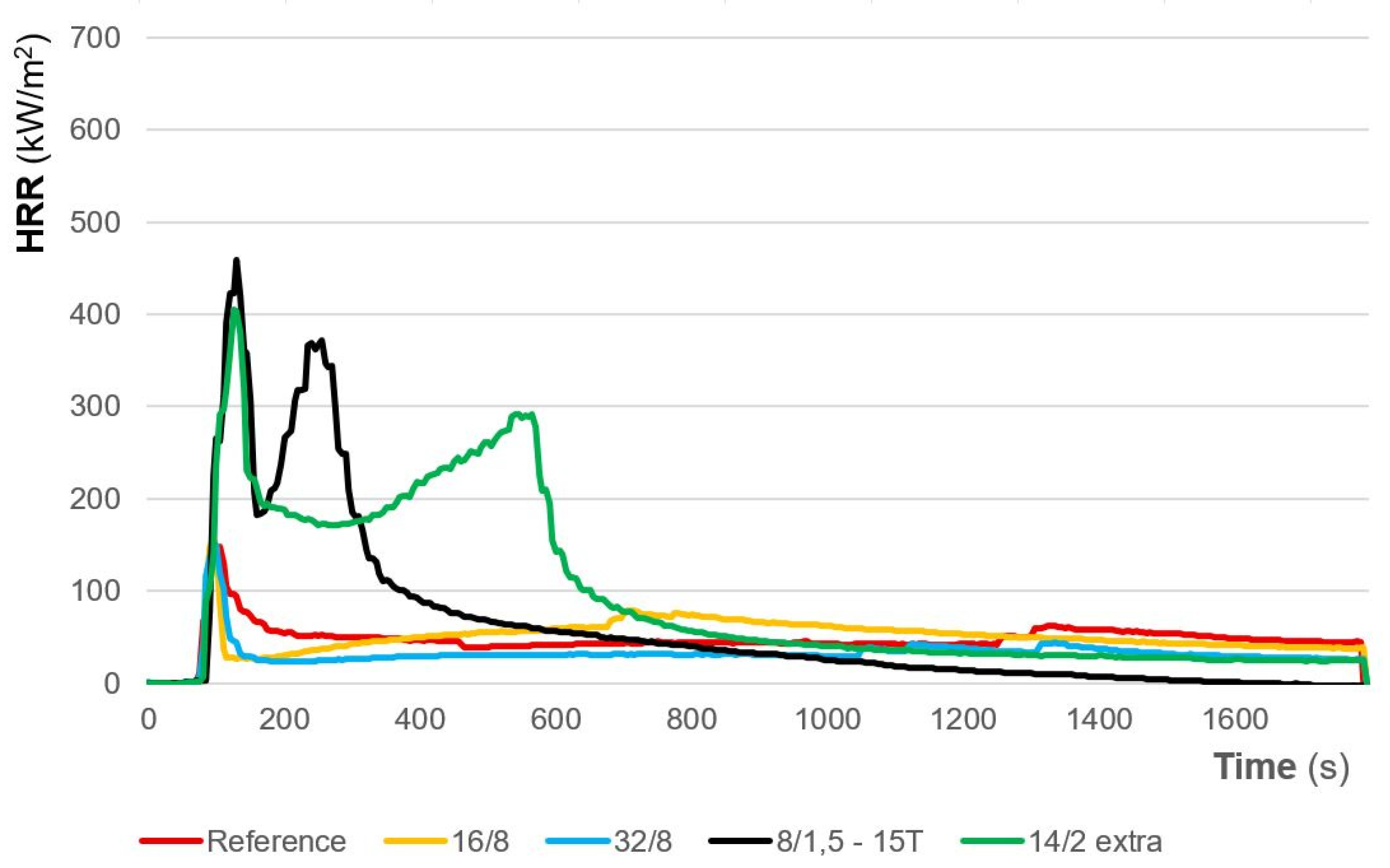

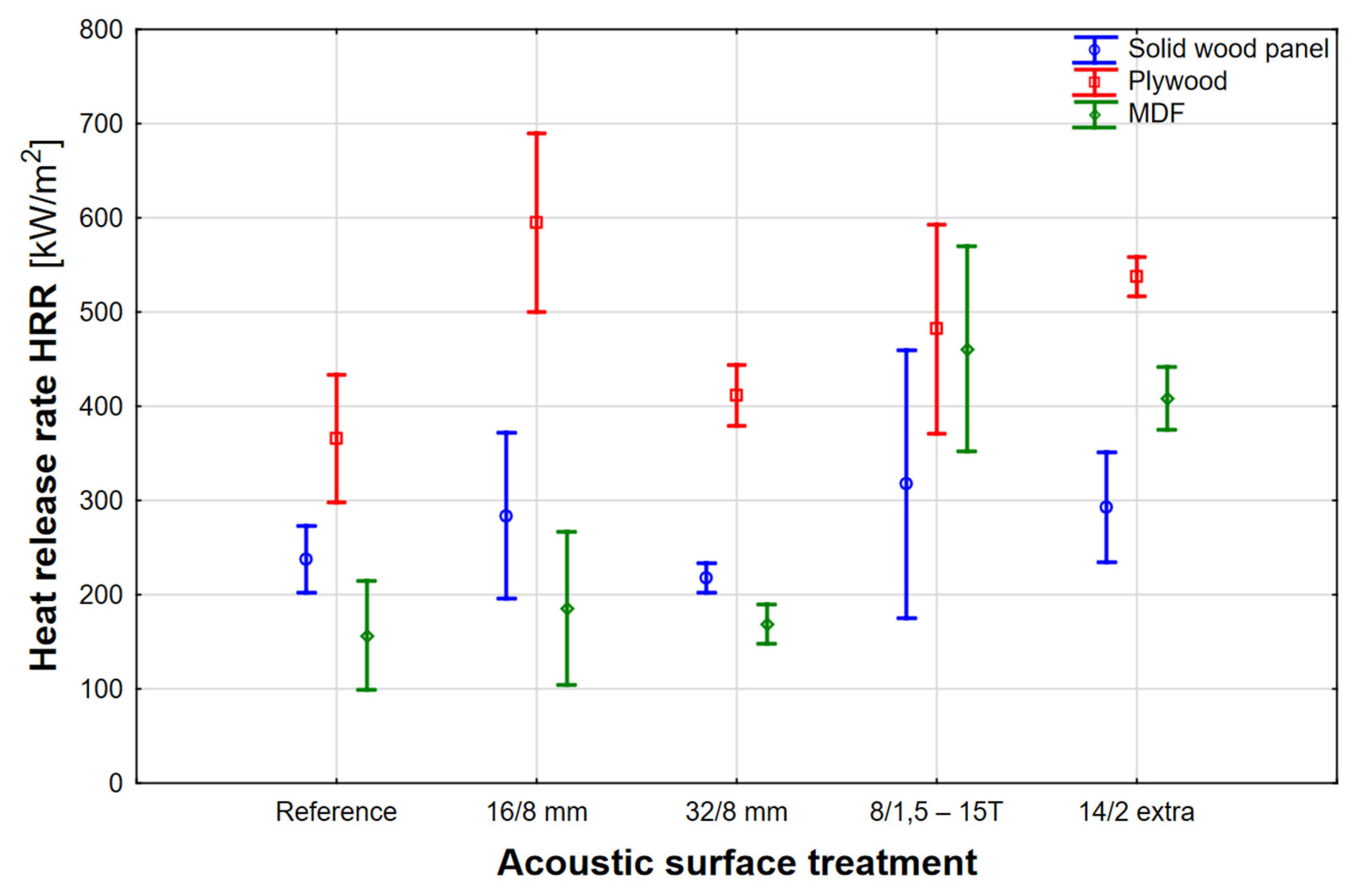

3.1. Cone Calorimeter

| Primary material |

Acoustic surface treatment |

Mean starting weight [g] | Mean weight after burning [g] |

Unburned fraction of starting weight [%] | Mass loss [g/m2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid wood panel | Reference | 85.7 | 8.12 | 9.47 | 7852 |

| 16/8 mm | 64.2 | 3.4 | 5.30 | 6015 | |

| 32/8 mm | 81.8 | 8.29 | 10.13 | 7416 | |

| 8/1,5 – 15T | 43.2 | 2.5 | 5.79 | 4322 | |

| 14/2 extra | 80.2 | 7.17 | 8.94 | 7339 | |

| Plywood | Reference | 118.2 | 16.75 | 14.17 | 10255 |

| 16/8 mm | 95.1 | 14.59 | 15.34 | 8201 | |

| 32/8 mm | 113.1 | 17.64 | 15.60 | 9709 | |

| 8/1,5 – 15T | 58.9 | 3.66 | 6.21 | 5656 | |

| 14/2 extra | 130.1 | 17.31 | 13.31 | 8732 | |

| MDF | Reference | 133.8 | 45.8 | 34.23 | 8984 |

| 16/8 mm | 105.7 | 31.28 | 29.59 | 7610 | |

| 32/8 mm | 128.4 | 40.56 | 31.59 | 8983 | |

| 8/1,5 – 15T | 56.2 | 2.51 | 4.47 | 5452 | |

| 14/2 extra | 100.7 | 14.37 | 14.27 | 8764 |

| Primary material of acoustic panel |

Acoustic surface treatment | HRR (kW/m2) |

MLR (g/m2s) |

MARHE (kW/m2) |

EHC (MJ/kg) |

TTI (s) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid wood panel | Reference | Mean | 237.87 | 4.57 | 109.17 | 18.80 | 75.33 |

| SD | 14.35 | 0.15 | 11.16 | 1.88 | 2.52 | ||

| 16/8 mm | Mean | 283.67 | 3.50 | 168,57 | 34.39 | 76.00 | |

| SD | 35.40 | 0.20 | 9.65 | 3.91 | 2.65 | ||

| 32/8 mm | Mean | 218.13 | 4.30 | 133,70 | 35.05 | 77.67 | |

| SD | 6.30 | 0.10 | 9.40 | 1.49 | 2.31 | ||

| 8/1,5 – 15 T | Mean | 317.50 | 2.50 | 153,20 | 44.86 | 81.00 | |

| SD | 57.30 | 0.10 | 11.53 | 4.96 | 3.00 | ||

| 14/2 extra | Mean | 292.47 | 4.23 | 157.83 | 36.35 | 81.33 | |

| SD | 23.55 | 0.21 | 5.78 | 3.72 | 4.16 | ||

| Plywood | Reference | Mean | 365.63 | 5.93 | 161.03 | 29.15 | 79.33 |

| SD | 27.20 | 0.15 | 13.23 | 3.43 | 2.08 | ||

| 16/8 mm | Mean | 595.03 | 4.73 | 235.17 | 37.45 | 81.33 | |

| SD | 38.22 | 0.29 | 18.13 | 3.16 | 1.15 | ||

| 32/8 mm | Mean | 411.70 | 5.63 | 202.50 | 42.25 | 83.67 | |

| SD | 13.06 | 0.06 | 5.20 | 7.04 | 2.08 | ||

| 8/1,5 – 15T | Mean | 481.80 | 3.30 | 197.37 | 35.25 | 81.33 | |

| SD | 44.48 | 0.30 | 2.85 | 3.42 | 1.53 | ||

| 14/2 extra | Mean | 537.63 | 5.23 | 225.43 | 43.54 | 81.67 | |

| SD | 8.32 | 0.12 | 4.48 | 3.41 | 1.15 | ||

| MDF | Reference | Mean | 156.57 | 5.20 | 56.77 | 16.38 | 78.67 |

| SD | 23.38 | 0.10 | 3.99 | 1.56 | 0.58 | ||

| 16/8 mm | Mean | 185.63 | 4.40 | 53.50 | 25.89 | 80.33 | |

| SD | 32.87 | 0.26 | 5.75 | 4.95 | 2.08 | ||

| 32/8 mm | Mean | 169.13 | 5.30 | 43.67 | 16.44 | 77.67 | |

| SD | 8.45 | 0.26 | 3.00 | 3.07 | 1.53 | ||

| 8/1,5 – 15T | Mean | 460.73 | 3.20 | 210.80 | 16.69 | 88.00 | |

| SD | 43.89 | 0.10 | 4.77 | 3,68 | 1.73 | ||

| 14/2 extra | Mean | 408.75 | 5,00 | 193,00 | 29.53 | 83.50 | |

| SD | 13.45 | 0.10 | 2.30 | 2.09 | 0.50 |

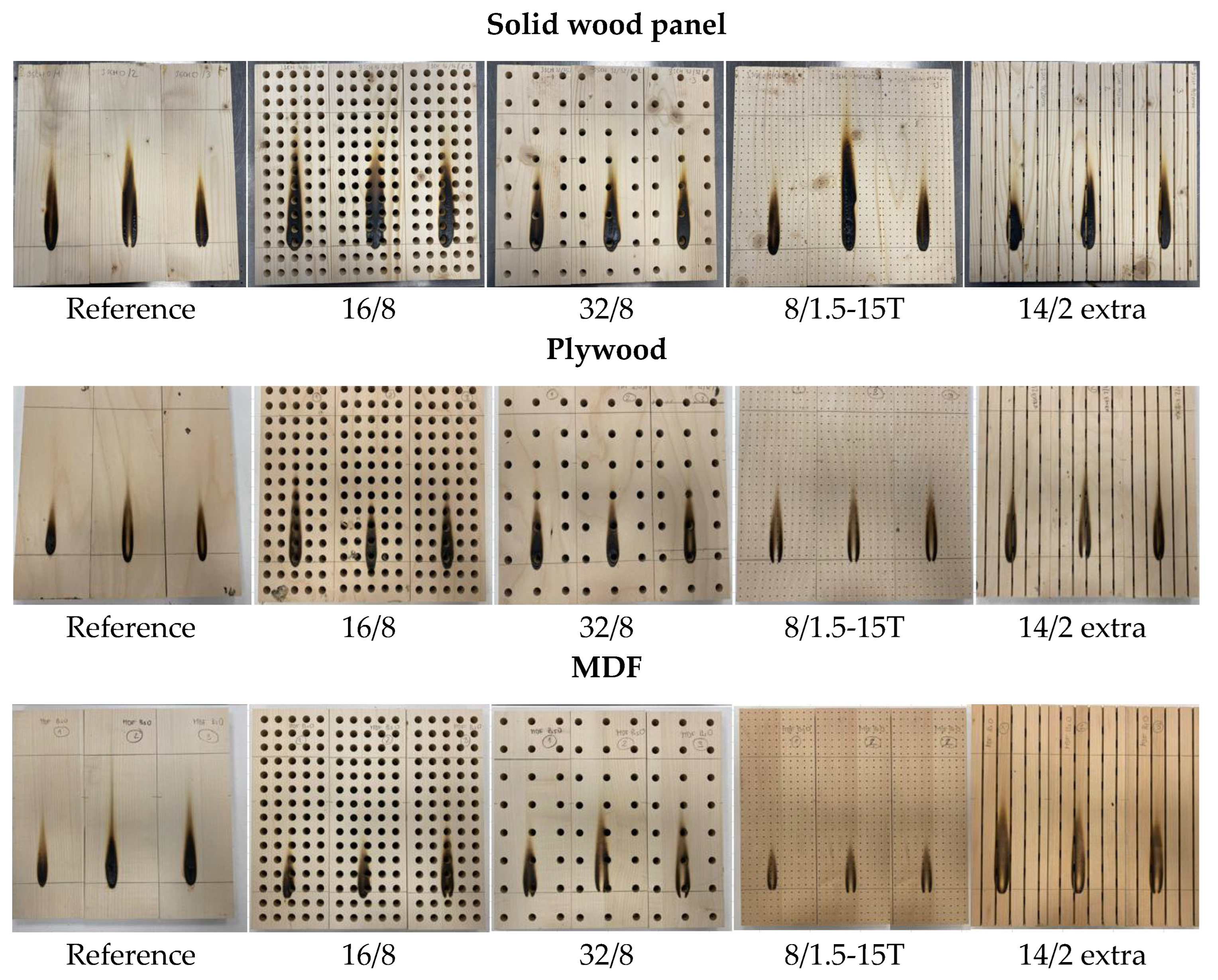

3.2. Single-Flame Source

| Average height of the charred area [mm] | Reaching the upper limit of 150 mm | Flaming combustion | Flaming droplets/ particles |

Filter paper ignition | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid wood panel | reference | 76.47 | No | No | No | No |

| 16/8 | 100.53 | No | Yes. 19s | No | No | |

| 32/8 | 80.90 | No | Yes. 18s | No | No | |

| 8/1.5 – 15T | 87.80 | No | No | No | No | |

| 14/2 extra | 71.17 | No | Yes. 16s | No | No | |

| Plywood | reference | 33.40 | No | No | No | No |

| 16/8 | 48.23 | No | No | No | No | |

| 32/8 | 41.60 | No | Yes. 24s | No | No | |

| 8/1.5 – 15T | 37.47 | No | No | No | No | |

| 14/2 extra | 67.13 | No | No | No | No | |

| MDF | reference | 54.40 | No | Yes. 23s | No | No |

| 16/8 | 47.43 | No | No | No | No | |

| 32/8 | 45.57 | No | No | No | No | |

| 8/1.5 – 15T | 28.05 | No | No | No | No | |

| 14/2 extra | 76.63 | No | No | No | No | |

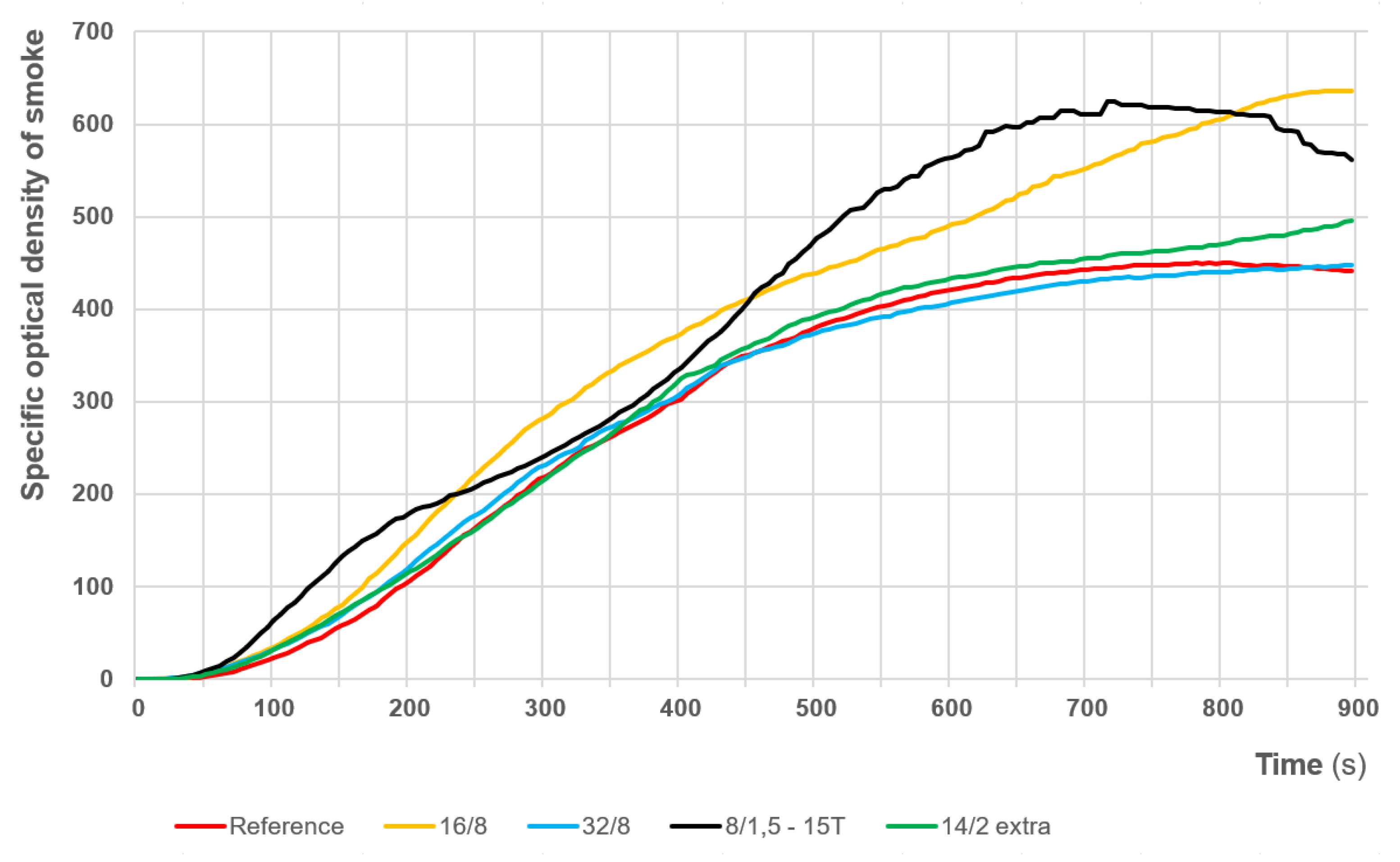

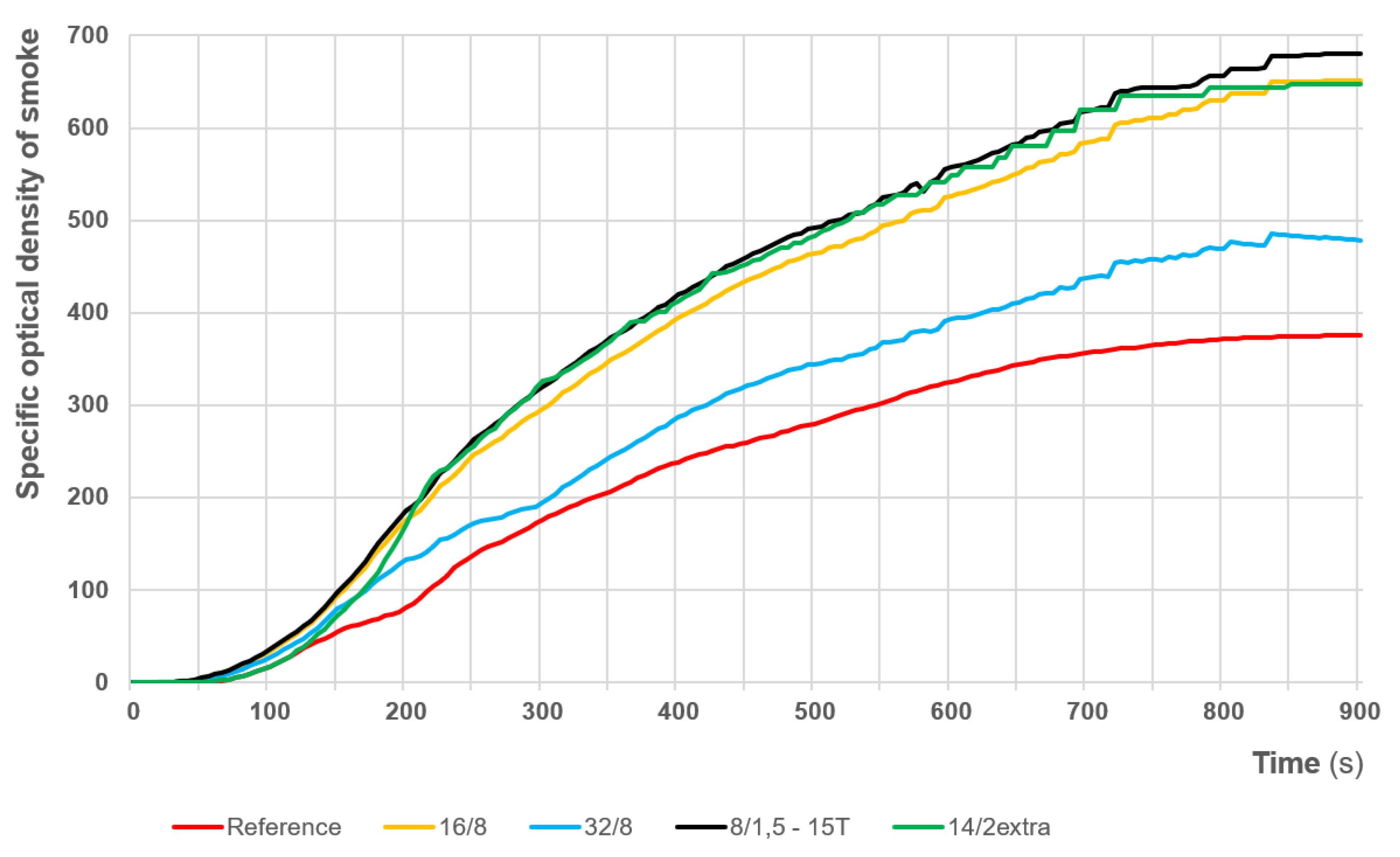

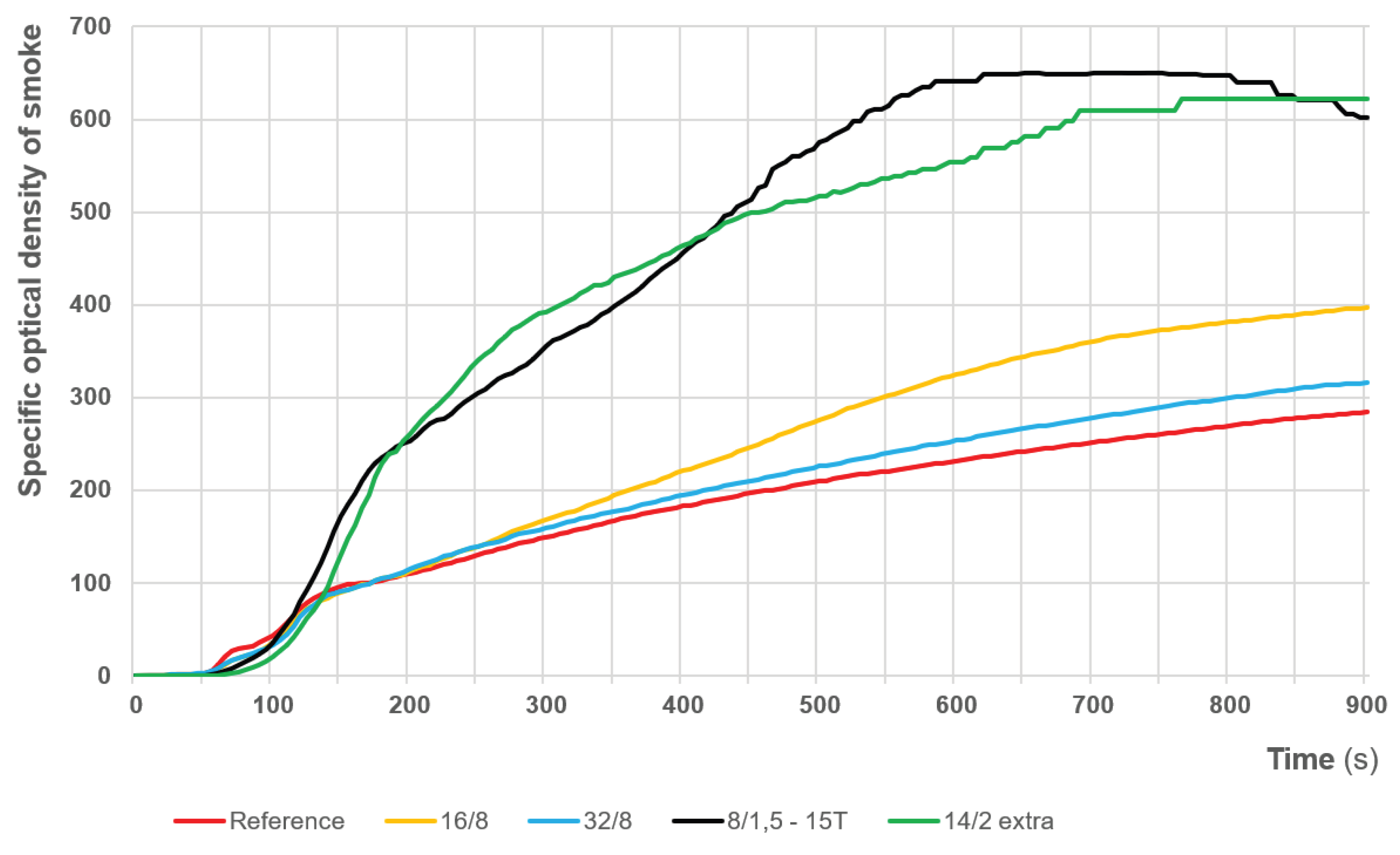

3.3. Smoke Generation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alao, P.F.; Dembovski, K.H.; Rohumaa, A.; Ruponen, J.; Kers, J. The Effect of Birch (Betula Pendula Roth) Face Veneer Thickness on the Reaction to Fire Properties of Fire-Retardant Treated Plywood. Construction and Building Materials 2024, 426, 136242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, S.N.; Green, F. Decay and Termite Resistance of Medium Density Fiberboard (MDF) Made from Different Wood Species. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2003, 51, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Pau, D.; Wang, J.; Ji, J. Modelling Pyrolysis of Charring Materials: Determining Flame Heat Flux Using Bench-Scale Experiments of Medium Density Fibreboard (MDF). Chemical Engineering Science 2015, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysik, A.M.; Muehl, J.H.; Youngquist, J.A.; Franca, F.S. Medium Density Fiberboard Made from Eucalyptus Saligna. Forest products journal 2001, Vol. 51(no. 10), 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ab Latib, H.; Choon Liat, L.; Ratnasingam, J.; Law, E.L.; Abdul Azim, A.A.; Mariapan, M.; Natkuncaran, J. Suitability of Paulownia Wood from Malaysia for Furniture Application. BioRes 2020, 15, 4727–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, M.C.; Radauer, H.; Petutschnigg, A.; Tudor, E.M.; Kathriner, M. Lightweight Solid Wood Panels Made of Paulownia Plantation Wood. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 11234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sudhakara, P.; Singh, J.; Singh, S.; Singh, G. Emerging Progressive Developments in the Fibrous Composites for Acoustic Applications. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2023, 102, 443–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashgari, M.; Taban, E.; SheikhMozafari, M.J.; Soltani, P.; Attenborough, K.; Khavanin, A. Wood Chip Sound Absorbers: Measurements and Models. Applied Acoustics 2024, 220, 109963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titze, M.; Misol, M.; Monner, H.P. Examination of the Vibroacoustic Behavior of a Grid-Stiffened Panel with Applied Passive Constrained Layer Damping. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2019, 453, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucharero, J.; Hänninen, T.; Lokki, T. Influence of Sound-Absorbing Material Placement on Room Acoustical Parameters. Acoustics 2019, 1, 644–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Saini, M.; Kumar Bagha, A.; Kumar, S. Experimental Study to Measure the Transmission Loss of Double Panel Natural Fibers. Materials Today: Proceedings 2020, 26, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.-Y.; Park, C.-S.; Song, K. Lightweight Soundproofing Membrane Acoustic Metamaterial for Broadband Sound Insulation. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2022, 178, 109270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-H.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, B.; Deng, Y.; Feng, Q.; Luo, J. Evaluating the Flammability of Wood-Based Panels and Gypsum Particleboard Using a Cone Calorimeter. Construction and Building Materials 2011, 25, 3044–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, S. Estimating the Fire Behavior of Wood Flooring Using a Cone Calorimeter. J Therm Anal Calorim 2012, 110, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Li, C.; Chi, Y.; Yan, J. TG-FTIR Study on Urea-Formaldehyde Resin Residue during Pyrolysis and Combustion. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2010, 173, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fateh, T.; Rogaume, T.; Luche, J.; Richard, F.; Jabouille, F. Characterization of the Thermal Decomposition of Two Kinds of Plywood with a Cone Calorimeter – FTIR Apparatus. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2014, 107, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Chen, L.; Harries, K.A.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Q.; Feng, J. Combustion and Charring Properties of Five Common Constructional Wood Species from Cone Calorimeter Tests. Construction and Building Materials 2015, 96, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouritz, A.P.; Mathys, Z.; Gibson, A.G. Heat Release of Polymer Composites in Fire. In Applied Science and Manufacturing; Composites Part A, 2006; Volume 37, pp. 1040–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.H.; Dietenberger, M.A. Fire Safety of Wood Construction. Wood handbook : wood as an engineering material: chapter 18. Centennial ed. General technical report FPL ; GTR-190; U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory: Madison, WI, 2010; Volume 190, p. p. 18.1-18.22. 18.1-18.22. [Google Scholar]

- Babrauskas, V. Heat Release Rates. In SFPE Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering; Hurley, M.J., Gottuk, D., Hall, J.R., Harada, K., Kuligowski, E., Puchovsky, M., Torero, J., Watts, J.M., Wieczorek, C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2016; pp. 799–904. ISBN 978-1-4939-2565-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bekhta, P.; Bryn, O.; Sedliačik, J.; Novák, I. Effect of Different Fire Retardants on Birch Plywood Properties. Acta Facultatis Xylologiae Zvolen 2016, 59−66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grexa, O.; Horváthová, E.; Bešinová, O.; Lehocký, P. Flame Retardant Treated Plywood. Polymer Degradation and Stability 1999, 64, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 13061-1; Physical and Mechanical Properties of Wood — Test Methods for Small Clear Wood Specimens — Part 1: Determination of Moisture Content for Physical and Mechanical Tests. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 5660-1; Reaction-to-Fire Tests - Heat Release, Smoke Production and Mass Loss Rate - Part 1: Heat Release Rate (Cone Calorimeter Method) and Smoke Production Rate (Dynamic Measurement). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ČSN EN ISO 11925-2; Reaction to Fire Tests – Ignitability of Products Subjected to Direct Impingement of Flame – Part 2: Single-Flame Source Test. Czech Standardization Agency: Prague, Czech Republic, 2020.

- ČSN EN ISO 5659-2; Plastics – Smoke Generation – Part 2: Determination of Optical Density by a Single-Chamber Test. Czech Standardization Agency: Prague, Czech Republic, 2017.

- Li, K.-Y.; Huang, X.; Fleischmann, C.; Rein, G.; Ji, J. Pyrolysis of Medium-Density Fiberboard: Optimized Search for Kinetics Scheme and Parameters via a Genetic Algorithm Driven by Kissinger’s Method. Energy &Amp; Fuels 2014, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowden, L.A.; Hull, T.R. Flammability Behaviour of Wood and a Review of the Methods for Its Reduction. Fire Sci Rev 2013, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-K.; Park, S.-H. Effects of Thermal Thickness and Charring Properties of Solid Combustibles on Heat Release and CO Emission Characteristics. Int J Fire Sci Eng 2022, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šejna, J.; Průšová, K.; Cábová, K.; Rušarová, S.; Wald, F. Cracks in the Charred Layer of Timber Panels: Fire Experiments and Probabilistic Solution. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2025, 74, 106788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anca-Couce, A.; Dieguez-Alonso, A.; Zobel, N.; Berger, A.; Kienzl, N.; Behrendt, F. Influence of Heterogeneous Secondary Reactions during Slow Pyrolysis on Char Oxidation Reactivity of Woody Biomass. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 2335–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Fan, Q.; Wu, W.; Hu, Y. Structure and Reactivity of Rice Husk Chars under Different Bulk Densities. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostikka, S.; Matala, A. Pyrolysis Model for Predicting the Heat Release Rate of Birch Wood. Combustion Science and Technology 2017, 189, 1373–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, G.F. Volatile Chemical Component Differences between Fully and Partially Dried Merbau (Intsia Sp.) Wood Using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) in Malaysia. Jurnal Sains Kesihatan Malaysia (Malaysian Journal of Health Sciences) 2019, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Morrisset, D.; Hadden, R.M.; Bartlett, A.I.; Law, A.; Emberley, R. Time Dependent Contribution of Char Oxidation and Flame Heat Feedback on the Mass Loss Rate of Timber. Fire Safety Journal 2021, 120, 103058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-C.; Nam, D.-G. Fire Characteristics of Flaming and Smoldering Combustion of Wood Combustibles Considering Thickness. Fire Science and Engineering 2015, 29, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanned, E.; Mensah, R.A.; Försth, M.; Das, O. The Curious Case of the Second/End Peak in the Heat Release Rate of Wood: A Cone Calorimeter Investigation. Fire and Materials 2023, 47, 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drysdale, D. An Introduction to Fire Dynamics, 3rd. ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2011; ISBN 978-1-119-97610-3. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Xin, Z.; Ke, D.; Lei, Z.; Ye, Q. Study of the Effect of Hole Defects on Wood Heat Transfer Based on Infrared Thermography. International Journal of Thermal Sciences 2023, 191, 108295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, A.; Kumar, R.; Dhiman, A.K.; Pandey, R.S.; Sharma, P.K. Study on the Influence of Vent Area on Porosity-Controlled Wood Crib Compartment Fires Prior to Flashover. Journal of Structural Fire Engineering 2023, 15, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangi, A.; Fontana, M.; Schleifer, V. Fire Behaviour of Timber Surfaces with Perforations. Fire and Materials 2005, 29, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, D.L.P.; Fonseca, E.M.M.; Piloto, P.A.G.; Meireles, J.M.; Barreira, L.M.S.; Ferreira, D.R.S.M. Perforated Cellular Wooden Slabs under Fire: Numerical and Experimental Approaches. Journal of Building Engineering 2016, 8, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, E.; Meireles, J.; Piloto, P.; Ferreira, D. Fire Resistance of Wooden Cellular Slabs with Rectangular Perforations 2015.

- Zhang, Z.; Ding, P.; Wang, S.; Huang, X. Smouldering-to-Flaming Transition on Wood Induced by Glowing Char Cracks and Cross Wind. Fuel 2023, 352, 129091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friquin, K.L. Material Properties and External Factors Influencing the Charring Rate of Solid Wood and Glue-Laminated Timber. Fire and Materials 2011, 35, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, D.; Fonseca, E.M.M.; Lamri, B. Thermal Model for Charring Rate Calculation in Wooden Cellular Slabs under Fire. In Proceedings of the ICOSADOS; Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro (UTAD), Vila Real, Portugal, May 10 2016; Vol. 7th, p. 8 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-F.; Zhang, C.; Karlsson, O.; Martinka, J.; Mantanis, G.I.; Rantuch, P.; Jones, D.; Sandberg, D. Phytic Acid-Silica System for Imparting Fire Retardancy in Wood Composites. Forests 2023, 14, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchoubeh, M.L.; Knight, H.; Horn, G.P. A Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Study of Volatile Compounds Produced by Wood-Based Materials. Fire and Materials 2024, 48, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, E.M.M.; Couto, D.; Piloto, P.A.G. Fire Safety in Perforated Wooden Slabs: A Numerical Approach 2013, 577–584.

- Martinka, J.; Mantanis, G.I.; Lykidis, C.; Antov, P.; Rantuch, P. The Effect of Partial Substitution of Polyphosphates by Aluminium Hydroxide and Borates on the Technological and Fire Properties of Medium Density Fibreboard. Wood Material Science & Engineering 2022, 17, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, M. Calorimetry. In SFPE Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering; Hurley, M.J., Gottuk, D., Hall, J.R., Harada, K., Kuligowski, E., Puchovsky, M., Torero, J., Watts, J.M., Wieczorek, C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2016; pp. 905–951. ISBN 978-1-4939-2565-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ira, J.; Hasalová, L.; Šálek, V.; Jahoda, M.; Vystrčil, V. Thermal Analysis and Cone Calorimeter Study of Engineered Wood with an Emphasis on Fire Modelling. Fire Technol 2020, 56, 1099–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Z. Fire Performance Comparison of Bamboo-Wood Composite and Spruce-Pine-Fir Cross-Laminated Timber Panels. Cellulose 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.; Chung, Y.-J. Combustive Properties of Medium Density Fibreboard (MDF) Specimens Treated with Alkylenediaminoalkyl-Bis-Phosphonic Acid Derivatives. Fire Science and Engineering 2014, 28, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, S.-M.; Kang, E.-C.; Son, D.-W. Combustibility and Characteristics of Wood-Fiber Insulation Boards Prepared with Four Different Adhesives. BioResources 2019, 14, 6316–6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałaj, J.; Gruszczyński, P. Analysis of Ignitability and Combustion Rate of Selected Interior Furnishing Materials. Zeszyty Naukowe SGSP / Szkoła Główna Służby Pożarniczej 2024, 91(tom 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, T.; Volkmer, T. Thermal Behaviour and Reaction to Fire of Three Various Hardwood Species Mineralized with Calcium Oxalate. In Proceedings of the The 10th European Conference on Wood Modification, 2022; p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Gašpercová, S.; Osvaldová, L.M. Influence of Surface Treatment of Wood to the Flame Length and Weight Loss under Load Single-Flame Source. Key Engineering Materials 2017, 755, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, A.; Kim, N.K.; Wijaya, W.; Bhattacharyya, D. Fire Reaction of Sandwich Panels with Corrugated and Honeycomb Cores Made from Natural Materials. Journal of Sandwich Structures & Materials 2021, 23, 109963622198923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmet’ová, E.; Zachar, M.; Kačíková, D. The Progressive Test Method for Assessing the Thermal Resistance of Spruce Wood. Acta Facultatis Xylologiae Zvolen res Publica Slovaca 2022, 64, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, A. Effect of Fire Retardant Painting Product on Smoke Optical Density of Burning Natural Wood Samples. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tissot, J.; Talbaut, M.; Yon, J.; Coppalle, A.; Bescond, A. Spectral Study of the Smoke Optical Density in Non-Flaming Condition. Procedia Engineering 2013, 62, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskolowski, W.; Łukaszek-Chmielewska, A.; Ogrodnik, P.; Sobczak, T. Evaluation of Maximum Specific Optical Density for Selected Wood Based Materials Using PN-EN ISO 5659:2017 Method. Annals of Warsaw University of Life Sciences - SGGW 2017, 100, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.-J.; Jian, H.; Wen, M.; Jo, S.-U. Toxic Gas and Smoke Generation and Flammability of Flame-Retardant Plywood. Polymers 2024, 16, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varada Rajulu, Ch.K.; Nandanwar, A.; Chandroji Rao, K. Evaluation of Smoke Density on Combustion of Wood Based Panel Products. International Journal of Materials and Chemistry 2013, 2, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Półka, M.; Białek, J. The Smoke Emission Properties of Selected Elements of Furnishing Apartments in the Building 2019.

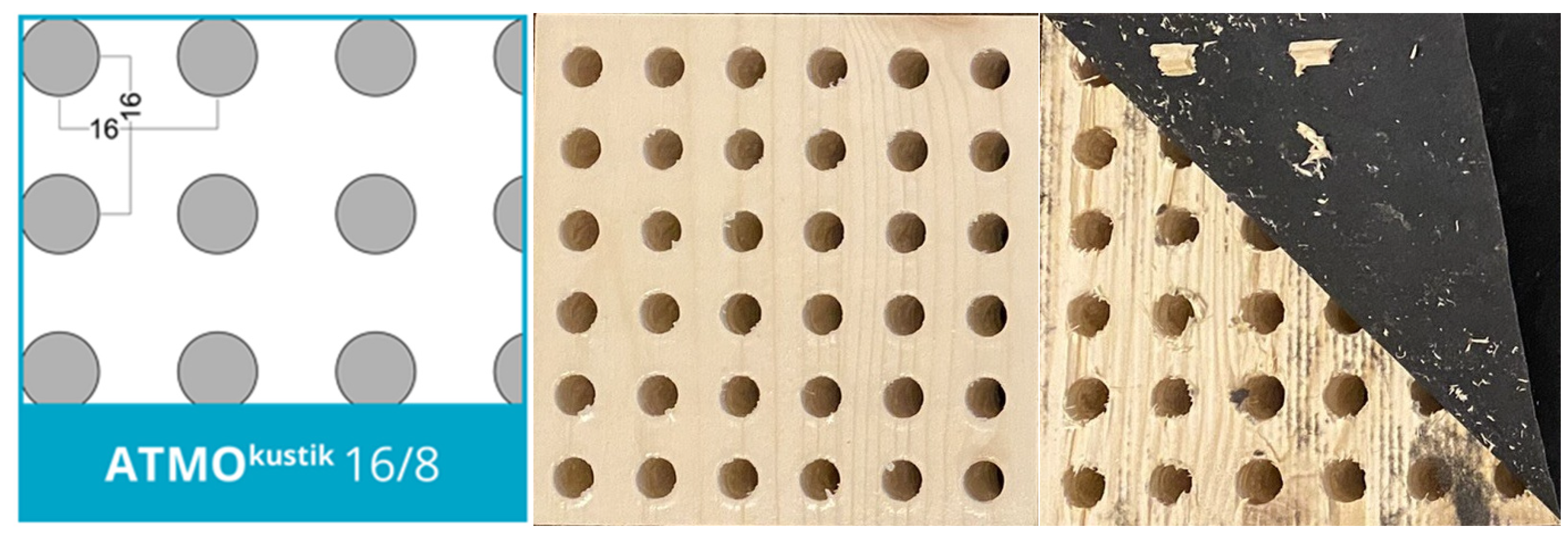

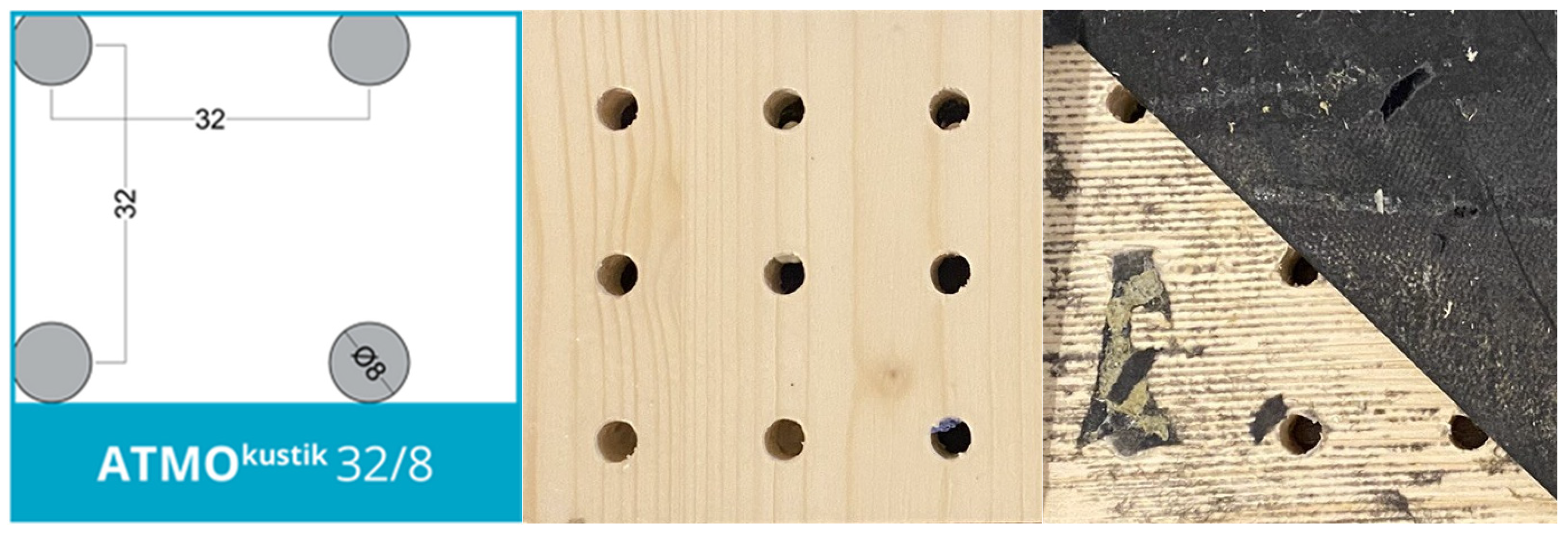

| Acoustic surface treatment |

No. of holes/ grooves per sample |

Sample surface [cm2] | Flat surface [cm2] |

Hollow surface [cm2] |

Difference [%] |

Flat surface after 5 mm burning [cm2] |

Hollow surface after 5 mm burning [cm2] |

Difference after 5 mm burning [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | 0 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 16/8 mm | 36 | 100.00 | 81.91 | 18.09 | 22.08 | 81.91 | 18.09 | 22.08 |

| 32/8 mm | 9 | 100.00 | 95.48 | 4.52 | 4.74 | 95.48 | 4.52 | 4.74 |

| 8/1.5 – 15T | 144 | 100.00 | 89.83 | 10.17 | 11.33 | 36.42 | 63.58 | 174.61 |

| 14/2 extra | 18/6 | 100.00 | 88.00 | 12.00 | 13.64 | 88.55 | 11.45 | 12.92 |

| Solid wood panels | |||||

| Time | reference | 16/8 | 32/8 | 8/1.5 – 15T | 14/2 extra |

| 4 min | 148.6 | 201.6 | 163.9 | 200.1 | 150.2 |

| 10 min | 420.5 | 488.3 | 405.3 | 563.0 | 431.2 |

| Max | 450.3 | 636.2 | 447.7 | 624.5 | 496.1 |

| Plywood | |||||

| reference | 16/8 | 32/8 | 8/1.5 – 15T | 14/2 extra | |

| 4 min | 128.8 | 232.3 | 164.6 | 247.9 | 216.7 |

| 10 min | 325.7 | 526.5 | 392.9 | 557.4 | 537.3 |

| Max | 375.9 | 651.8 | 485.6 | 680.8 | 641.3 |

| MDF | |||||

| reference | 16/8 | 32/8 | 8/1.5 – 15T | 14/2 extra | |

| 4 min | 162.1 | 135.2 | 135.4 | 295.0 | 322.6 |

| 10 min | 231.9 | 325.7 | 253.9 | 641.4 | 554.3 |

| Max | 284.5 | 396.8 | 316.1 | 650.2 | 621.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).