Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

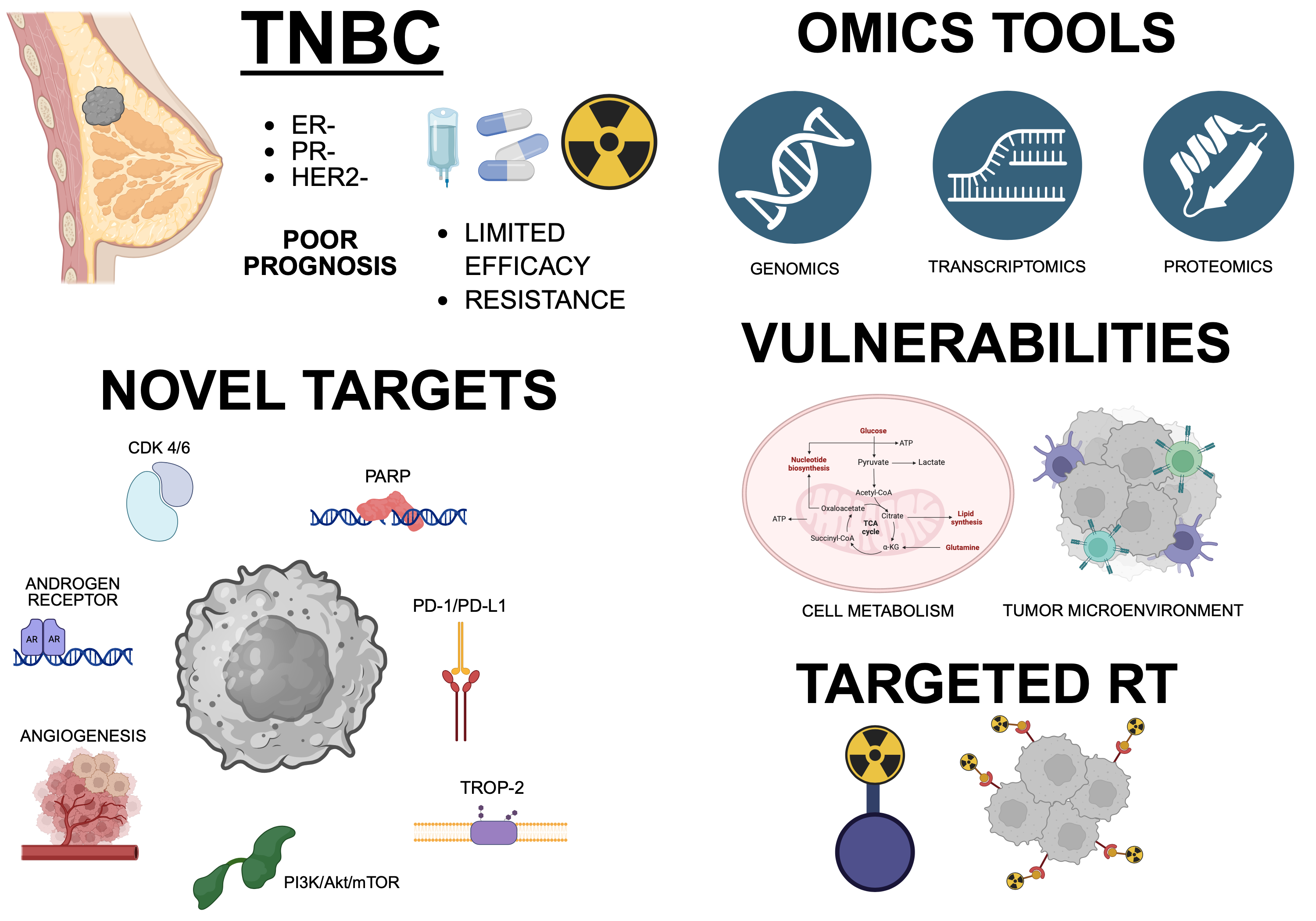

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Prognosis

1.2. Molecular, Histological and Clinical Classification

- Basal-Like Immuno Suppressed (BLIS), characterized by downregulation of B, T and natural killer (NK) cell immune-regulating pathways and cytokine pathways;

- Basal-Like Immune Activated (BLIA), displaying an opposite transcriptional profile with respect to the BLIS subtype, with upregulation of genes involved in immune cells activity;

- Mesenchymal (M or MES), enriched for genes involved in cell motility, Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT), DNA Damage Response (DDR) pathways and growth factors pathways like the Insulin Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) one. This type of cells constitutes metaplastic carcinomas with preferential metastasis to lungs, and shows defects in PhosphoInositide 3-Kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt)/mechanistic Target Of Rapamycin (mTOR) (PI3K/Akt/mTOR) pathway;

- Luminal Androgen Receptor (LAR), characterized by Androgen Receptor (AR) signaling and hormonally regulated pathways, including the one of the ER. This feature is due to a small (~1%) subpopulation of LAR TNBC cells that show low ER activation, but these BCs are still classified as triple-negative because this subpopulation is too small to be detected by immunohistochemistry. This cell type causes a low-grade lobular carcinoma, with increased frequency of lymph node involvement. It represents 11% of all TNBCs [7,8].

- Mesenchymal Stem-Like (MSL), which is enriched for stem cell-associated genes expression and angiogenesis genes expression;

- Immuno Modulatory (IM), whose tumor tissue overexpresses immune cell markers, like Nuclear Factor kappa B (NFKB), Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF), Janus Kinase (JAK) and immune regulators like Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated protein 4 (CTLA4), Programmed Death-1 and Programmed cell Death Ligand-1 (PD-1 and PD-L1), and displays the better prognosis among TNBCs. More than a proper tumoral subclass, this phenotype has been defined as the result of an immune modulation of the tumor generated by lymphocyte infiltration in the cancer microenvironment. Moreover, there is evidence that the presence of TILs might be a positive prognostic factor [2,8,9,10,11].

1.3. Current Therapies and Unmet Therapeutic Needs

2. Current Approaches and Clinical Trials

2.1. Targeted Therapy in TNBC Patients

2.2. Current Treatments and Clinical Trials

PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors

2.3. PARP Inhibitors

2.4. Trop-2-Targeted Antibodies

2.5. Anti-Angiogenic Agents

2.6. PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway Inhibitors

2.7. Androgen Receptor Inhibitors

2.8. CDK 4/6 Inhibitors

3. New Possible Targets Identified by Omics Approaches

3.1. γ-Glutamyl Hydrolase (GGH)

3.2. ThYMidylate Synthase (TYMS)

3.3. Protein-Tyrosine Kinase 6 (PTK6)

3.4. Mitochondrial DNA Topoisomerase I (TOP1MT)

3.5. Smoothened Receptor (SMO)

3.6. Colony-Stimulating Factor 1receptor (CSF1R)

3.7. Ephrin Type B Receptor 3 (EPHB3)

3.8. Tribbles Pseudokinase 1(TRIB1)

3.9. Ladinin-1 (LAD1)

| Protein | Role in Cancer Pathogenesis | Evidence in TNBC / Relevance | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMO (Smoothened) |

Aberrant activation of SMO promotes proliferation, invasion, stem-cell-like traits and therapy resistance in various cancers. | SMO (and GLI1) expression correlates with higher grade, node positivity, poorer prognosis. | [125,150] |

| CSF1R (Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor) |

Promotes tumour-associated macrophage (TAM) support, immune evasion, angiogenesis and metastatic spread. | High CSF1R expression has been associated with inferior survival, and preclinical models show CSF1R inhibition reduces brain metastasis in TNBC. | [151] |

| EPHB3 (Ephrin type-B receptor 3) |

Dysregulation can promote invasion/metastasis in cancers. | In TNBC, integrative genomic analyses have flagged EPHB3 as a hyperactivated gene and a potential target. | [139] |

| TRIB1 (Tribbles pseudokinase 1) |

Over-expression correlates with poor prognosis; promotes resistance to therapy. | In breast cancer, elevated TRIB1 correlates with worse survival. | [152] |

| LAD1 (Ladinin-1) | Over-expression has been associated with more aggressive phenotypes in various cancers (breast, lung). | Higher LAD1 links to increased migration/metastatic potential; genomics in TNBC flag LAD1 as potential target. | [148,153] |

4. Metabolic Vulnerabilities in TNBC

5. Tumor Microenvironment and Immune-Modulating Factors

5.1. Pharmacological Targeting of EMT in TNBC

5.2. Cancer-Associated Adipocytes as Mediators of Immune Evasion and Metabolic Crosstalk

5.3. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts as Drivers of Fibrosis, Hypoxia and Drug Resistance

5.4. Targeting Immune Cells in TME

5.5. Soluble Factors Released in TME as Modulator of TNBC Target Therapy

6. Targeted Radiotherapy in TNBC

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Xiong, X.; Zheng, L.W.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Cai, Y.W.; Wang, L.P.; Huang, L.; Liu, C.C.; Shao, Z.M.; Yu, K. Da Breast Cancer: Pathogenesis and Treatments. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Derakhshan, F.; Reis-Filho, J.S. Pathogenesis of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2021, 17, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansour, N.M. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Brief Review About Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Signaling Pathways, Treatment and Role of Artificial Intelligence. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 836417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breast Cancer Research Foundation | BCRF. Available online: https://www.bcrf.org/ (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Yin, L.; Duan, J.J.; Bian, X.W.; Yu, S.C. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Molecular Subtyping and Treatment Progress. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlak, S.; Pagès, G.; Luciano, F. Enhancing Radiotherapy Techniques for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Treatment. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2025, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, M.D.; Tsimelzon, A.; Poage, G.M.; Covington, K.R.; Contreras, A.; Fuqua, S.A.W.; Savage, M.I.; Osborne, C.K.; Hilsenbeck, S.G.; Chang, J.C.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Analysis Identifies Novel Subtypes and Targets of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 1688–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, B.D.; Jovanović, B.; Chen, X.; Estrada, M. V.; Johnson, K.N.; Shyr, Y.; Moses, H.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Pietenpol, J.A. Refinement of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes: Implications for Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Selection. PLoS One 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yam, C.; Mani, S.A.; Moulder, S.L. Targeting the Molecular Subtypes of Triple Negative Breast Cancer: Understanding the Diversity to Progress the Field. Oncologist 2017, 22, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, L.; Zhou, J.; Guo, S.; Xu, N.; Ma, R. The Molecular Subtyping and Precision Medicine in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer---Based on Fudan TNBC Classification. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagia, E.; Mahalingam, D.; Cristofanilli, M. The Landscape of Targeted Therapies in TNBC. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, B.D.; Jovanović, B.; Chen, X.; Estrada, M. V.; Johnson, K.N.; Shyr, Y.; Moses, H.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Pietenpol, J.A. Refinement of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes: Implications for Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Selection. PLoS One 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, C.K.; Abramson, V.; Tan, T.; Dent, R. The Evolution of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: From Biology to Novel Therapeutics. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. book. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Annu. Meet. 2016, 35, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wu, Y.; Song, B.; Yi, M.; Yan, Y.; Mei, Q.; Wu, K. Recent Advances in Targeted Strategies for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrantia-Borunda, E.; Anchondo-Nuñez, P.; Acuña-Aguilar, L.E.; Gómez-Valles, F.O.; Ramírez-Valdespino, C.A. Subtypes of Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer 2022, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, K.A.; Spruck, C. Triple-negative Breast Cancer Therapy: Current and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 57, 1245–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, P.; Scatena, C.; Ghilli, M.; Bargagna, I.; Lorenzini, G.; Nicolini, A. Molecular Mechanisms, Biomarkers and Emerging Therapies for Chemotherapy Resistant TNBC. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Merkher, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, N.; Leonov, S.; Chen, Y. Recent Advances in Therapeutic Strategies for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.Y.; Rancoule, C.; Rehailia-Blanchard, A.; Espenel, S.; Trone, J.C.; Bernichon, E.; Guillaume, E.; Vallard, A.; Magné, N. Radiotherapy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Current Situation and Upcoming Strategies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2018, 131, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, W.; Verma, V.; Hsiao, K.Y.; Hatch, S.; Arentz, C.; Szeja, S.; Schwartz, M.; Niravath, P.; Bonefas, E.; Miltenburg, D.; et al. Omission of Radiation Therapy Following Breast Conservation in Older (≥70 Years) Women with T1-2N0 Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Breast J. 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulkarim, B.S.; Cuartero, J.; Hanson, J.; Deschênes, J.; Lesniak, D.; Sabri, S. Increased Risk of Locoregional Recurrence for Women with T1-2N0 Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Treated with Modified Radical Mastectomy without Adjuvant Radiation Therapy Compared with Breast-Conserving Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.Y.; Rancoule, C.; Rehailia-Blanchard, A.; Espenel, S.; Trone, J.C.; Bernichon, E.; Guillaume, E.; Vallard, A.; Magné, N. Radiotherapy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Current Situation and Upcoming Strategies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2018, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Ye, Y.; Chen, Y. Advances in the Understanding of the Pathogenesis of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Med. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emara, H.M.; Allam, N.K.; Youness, R.A. A Comprehensive Review on Targeted Therapies for Triple Negative Breast Cancer: An Evidence-Based Treatment Guideline. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, W.-J.; Chen, L.; Shen, Y.; Wang, Z.-H.; Liu, G.-Y.; Yu, K.-D.; Di, G.-H.; Wu, J.; Li, J.-J.; Shao, Z.-M. Rational and Trial Design of FASCINATE-N: A Prospective, Randomized, Precision-Based Umbrella Trial. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2024, 16, 17588359231225032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home | ClinicalTrials. Gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, M.; Nie, H.; Yuan, Y. PD-1 and PD-L1 in Cancer Immunotherapy: Clinical Implications and Future Considerations. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Kang, K.; Chen, P.; Zeng, Z.; Li, G.; Xiong, W.; Yi, M.; Xiang, B. Regulatory Mechanisms of PD-1/PD-L1 in Cancers. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heater, N.K.; Warrior, S.; Lu, J. Current and Future Immunotherapy for Breast Cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naing, A.; Gainor, J.F.; Gelderblom, H.; Forde, P.M.; Butler, M.O.; Lin, C.C.; Sharma, S.; Ochoa De Olza, M.; Varga, A.; Taylor, M.; et al. A First-in-Human Phase 1 Dose Escalation Study of Spartalizumab (PDR001), an Anti-PD-1 Antibody, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, T.; Zhang, S.; Song, H.; Xu, M.; Yao, S.; Jiang, Z. JS001, an Anti-PD-1 MAb for Advanced Triple Negative Breast Cancer Patients after Multi-Line Systemic Therapy in a Phase I Trial. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 435–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, G.; Yau, T.C.C.; Chiu, J.W.; Tse, E.; Kwong, Y.L. Pembrolizumab (Keytruda). Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2016, 12, 2777–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arru, C.; De Miglio, M.R.; Cossu, A.; Muroni, M.R.; Carru, C.; Zinellu, A.; Paliogiannis, P. Durvalumab Plus Tremelimumab in Solid Tumors: A Systematic Review. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 3674–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Oliveira, M.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Cristofanilli, M.; Graff, S.L.; Im, S.-A.; Loi, S.; Saji, S.; Wang, S.; Cescon, D.W.; et al. TROPION-Breast05: A Randomized Phase III Study of Dato-DXd with or without Durvalumab versus Chemotherapy plus Pembrolizumab in Patients with PD-L1-High Locally Recurrent Inoperable or Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2025, 17, 17588359251327992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.M.; Gulley, J.L. Product Review: Avelumab, an Anti-PD-L1 Antibody. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 891–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.K.; Loriot, Y.; Necchi, A.; Singh, P.; Castellano, D.; Pagliaro, L.; Suarez, C.; McGregor, B.A.; Vaishampayan, U.N.; Hauke, R.J.; et al. COSMIC-021 Phase Ib Study of Cabozantinib Plus Atezolizumab: Results from the Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma Cohorts. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 1650–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Loriot, Y.; Burgoyne, A.M.; Cleary, J.M.; Santoro, A.; Lin, D.; Aix, S.P.; Garrido-Laguna, I.; Sudhagoni, R.; Guo, X.; et al. Cabozantinib plus Atezolizumab in Previously Untreated Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Previously Treated Gastric Cancer and Gastroesophageal Junction Adenocarcinoma: Results from Two Expansion Cohorts of a Multicentre, Open-Label, Phase 1b Trial (…. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 67, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.K.; McGregor, B.; Suárez, C.; Tsao, C.K.; Kelly, W.; Vaishampayan, U.; Pagliaro, L.; Maughan, B.L.; Loriot, Y.; Castellano, D.; et al. Cabozantinib in Combination With Atezolizumab for Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: Results From the COSMIC-021 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 3725–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barchiesi, G.; Roberto, M.; Verrico, M.; Vici, P.; Tomao, S.; Tomao, F. Emerging Role of PARP Inhibitors in Metastatic Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Current Scenario and Future Perspectives. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 769280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, K.; Zheng, D.; Luo, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhong, X.; Zheng, H. Efficacy and Safety of PARP Inhibitors in Advanced or Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 742139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litton, J.K.; Rugo, H.S.; Ettl, J.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Gonçalves, A.; Lee, K.-H.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Yerushalmi, R.; Mina, L.A.; Martin, M.; et al. Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kummar, S.; Wade, J.L.; Oza, A.M.; Sullivan, D.; Chen, A.P.; Gandara, D.R.; Ji, J.; Kinders, R.J.; Wang, L.; Allen, D.; et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Cyclophosphamide and the Oral Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase Inhibitor Veliparib in Patients with Recurrent, Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Invest. New Drugs 2016, 34, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kummar, S.; Ji, J.; Morgan, R.; Lenz, H.J.; Puhalla, S.L.; Belani, C.P.; Gandara, D.R.; Allen, D.; Kiesel, B.; Beumer, J.H.; et al. A Phase I Study of Veliparib in Combination with Metronomic Cyclophosphamide in Adults with Refractory Solid Tumors and Lymphomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 1726–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayak, S.; Tolaney, S.M.; Schwartzberg, L.; Mita, M.; McCann, G.; Tan, A.R.; Wahner-Hendrickson, A.E.; Forero, A.; Anders, C.; Wulf, G.M.; et al. Open-Label Clinical Trial of Niraparib Combined with Pembrolizumab for Treatment of Advanced or Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.J.; Sammons, S.; Im, Y.H.; She, L.; Mundy, K.; Bigelow, R.; Traina, T.A.; Anders, C.; Yeong, J.; Renzulli, E.; et al. Phase II DORA Study of Olaparib with or without Durvalumab as a Chemotherapy-Free Maintenance Strategy in Platinum-Pretreated Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelmon, K.A.; Tischkowitz, M.; Mackay, H.; Swenerton, K.; Robidoux, A.; Tonkin, K.; Hirte, H.; Huntsman, D.; Clemons, M.; Gilks, B.; et al. Olaparib in Patients with Recurrent High-Grade Serous or Poorly Differentiated Ovarian Carcinoma or Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Phase 2, Multicentre, Open-Label, Non-Randomised Study. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, J.J.; Afghahi, A.; Timms, K.; DeWees, A.; Gross, W.; Aushev, V.N.; Wu, H.T.; Balcioglu, M.; Sethi, H.; Scott, D.; et al. A Phase II Study of Talazoparib Monotherapy in Patients with Wild-Type BRCA1 and BRCA2 with a Mutation in Other Homologous Recombination Genes. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, M.; Tong, Y.; Jones, D.R.; Walsh, T.; Danso, M.A.; Ma, C.X.; Silverman, P.; King, M.-C.; Badve, S.S.; Perkins, S.M.; et al. Cisplatin +/- Rucaparib after Preoperative Chemotherapy in Patients with Triple-Negative or BRCA Mutated Breast Cancer. NPJ breast cancer 2021, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stradella, A.; Johnson, M.; Goel, S.; Park, H.; Lakhani, N.; Arkenau, H.T.; Galsky, M.D.; Calvo, E.; Baz, V.; Moreno, V.; et al. Phase 1b Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability, and Clinical Activity of Pamiparib in Combination with Temozolomide in Patients with Locally Advanced or Metastatic Solid Tumors. Cancer Med. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquetto, M.V.; Vecchia, L.; Covini, D.; Digilio, R.; Scotti, C. Targeted Drug Delivery Using Immunoconjugates: Principles and Applications. J. Immunother. 2011, 34, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiatowski, T.; Kalinka, E. Antibody-Drug Conjugates in the Treatment of Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Prz. menopauzalny = Menopause Rev. 2025, 24, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadela, A.; Soni, S.; Shah, A.C.; Pandya, A.J.; Megha, K.; Kothari, N.; Cb, A. Unveiling the Antibody-Drug Conjugates Portfolio in Battling Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Therapeutic Trends and Future Horizon. Med. Oncol. 2022, 40, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Jarroudi, O.; El Bairi, K.; Curigliano, G.; Afqir, S. Antibody–Drug Conjugates: A New Therapeutic Approach for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Treat. Res. 2023, 188, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Fan, X.; Liu, H.; Liang, T. Advances in Trop-2 Targeted Antibody-Drug Conjugates for Breast Cancer: Mechanisms, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranic, S.; Gatalica, Z. Trop-2 Protein as a Therapeutic Target: A Focused Review on Trop-2-Based Antibody-Drug Conjugates and Their Predictive Biomarkers. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2022, 22, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskinkilic, M.; Sacks, R. Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 2024, 24, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spring, L.M.; Nakajima, E.; Hutchinson, J.; Viscosi, E.; Blouin, G.; Weekes, C.; Rugo, H.; Moy, B.; Bardia, A. Sacituzumab Govitecan for Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Clinical Overview and Management of Potential Toxicities. Oncologist 2021, 26, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dri, A.; Arpino, G.; Bianchini, G.; Curigliano, G.; Danesi, R.; De Laurentiis, M.; Del Mastro, L.; Fabi, A.; Generali, D.; Gennari, A.; et al. Breaking Barriers in Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) – Unleashing the Power of Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs). Cancer Treat. Rev. 2024, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardia, A.; Messersmith, W.A.; Kio, E.A.; Berlin, J.D.; Vahdat, L.; Masters, G.A.; Moroose, R.; Santin, A.D.; Kalinsky, K.; Picozzi, V.; et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan, a Trop-2-Directed Antibody-Drug Conjugate, for Patients with Epithelial Cancer: Final Safety and Efficacy Results from the Phase I/II IMMU-132-01 Basket Trial. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Shen, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, J.; Ni, C.; Chen, Z. Antiangiogenic Therapy Reverses the Immunosuppressive Breast Cancer Microenvironment. Biomark. Res. 2021, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugano, R.; Ramachandran, M.; Dimberg, A. Tumor Angiogenesis: Causes, Consequences, Challenges and Opportunities. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 1745–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, H.; Kakeya, H. Targeting Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 (HIF-1) Signaling with Natural Products toward Cancer Chemotherapy. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo). 2021, 74, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Wang, P. Lenvatinib in Management of Solid Tumors. Oncologist 2020, 25, e302–e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.C.; Saada-Bouzid, E.; Longo, F.; Yanez, E.; Im, S.A.; Castanon, E.; Desautels, D.N.; Graham, D.M.; Garcia-Corbacho, J.; Lopez, J.; et al. Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab for Patients with Previously Treated, Advanced, Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Results from the Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cohort of the Phase 2 LEAP-005 Study. Cancer 2024, 130, 3278–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Zheng, F.; Ren, D.; Du, F.; Dong, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, F.; Ahmad, R.; Zhao, J. Anlotinib: A Novel Multi-Targeting Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor in Clinical Development. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Ge, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, B.; Yang, C.; Gao, H.; Yang, M.; Zhu, T.; Wang, K. Neoadjuvant Anlotinib/Sintilimab plus Chemotherapy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (NeoSACT): Phase 2 Trial. Cell Reports Med. 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.P.; Jiang, R.Y.; Zhu, J.Y.; Sun, K.N.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, H.H.; Zheng, Y.B.; Wang, X.J. PI3K/AKT/MTOR Signaling Pathway: An Important Driver and Therapeutic Target in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer 2024, 31, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massihnia, D.; Galvano, A.; Fanale, D.; Perez, A.; Castiglia, M.; Incorvaia, L.; Listì, A.; Rizzo, S.; Cicero, G.; Bazan, V.; et al. Triple Negative Breast Cancer: Shedding Light onto the Role of Pi3k/Akt/Mtor Pathway. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 60712–60722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Castro, A.C.; Saura, C.; Barroso-Sousa, R.; Guo, H.; Ciruelos, E.; Bermejo, B.; Gavilá, J.; Serra, V.; Prat, A.; Paré, L.; et al. Phase 2 Study of Buparlisib (BKM120), a Pan-Class I PI3K Inhibitor, in Patients with Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curigliano, G.; Shapiro, G.I.; Kristeleit, R.S.; Abdul Razak, A.R.; Leong, S.; Alsina, M.; Giordano, A.; Gelmon, K.A.; Stringer-Reasor, E.; Vaishampayan, U.N.; et al. A Phase 1B Open-Label Study of Gedatolisib (PF-05212384) in Combination with Other Anti-Tumour Agents for Patients with Advanced Solid Tumours and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schram, A.M.; Takebe, N.; Chen, A.; Zhou, Q.; Iasonos, A.; Silber, J.; Reynolds, M.; Hussain, S.; Gavriliuc, M.; Smyth, L.M.; et al. A Phase I Study of AZD8186 in Combination with Docetaxel in Patients with PTEN-Mutated or PIK3CB-Mutated Advanced Solid Tumors. ESMO Open 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vtorushin, S.; Dulesova, A.; Krakhmal, N. Luminal Androgen Receptor (LAR) Subtype of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Molecular, Morphological, and Clinical Features. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2022, 23, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echavarria, I.; Lopez-Tarruella, S.; Picornell, A.; García-Saenz, J.A.; Jerez, Y.; Hoadley, K.; Gomez, H.L.; Moreno, F.; Del Monte-Millan, M.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; et al. Pathological Response in a Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cohort Treated with Neoadjuvant Carboplatin and Docetaxel According to Lehmann’s Refined Classification. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1845–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yang, Y.; Xu, K.; Li, L.; Huang, J.; Qiu, F. Androgen Receptor in Breast Cancer: From Bench to Bedside. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2020, 11, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholar, E. Bicalutamide. xPharm Compr. Pharmacol. Ref. 2007, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. Darolutamide: A Review in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. Target. Oncol. 2023, 18, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, L.M.; Wander, S.A.; Zangardi, M.; Bardia, A. CDK 4/6 Inhibitors in Breast Cancer: Current Controversies and Future Directions. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, L.; Wilson, C.; Holen, I. CDK4/6 Inhibitors: A Potential Therapeutic Approach for Triple Negative Breast Cancer. MedComm 2021, 2, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, M.; Li, M. Potential Prospect of CDK4/6 Inhibitors in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 5223–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerosa, R.; De Sanctis, R.; Jacobs, F.; Benvenuti, C.; Gaudio, M.; Saltalamacchia, G.; Torrisi, R.; Masci, G.; Miggiano, C.; Agustoni, F.; et al. Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 2 (CDK2) Inhibitors and Others Novel CDK Inhibitors (CDKi) in Breast Cancer: Clinical Trials, Current Impact, and Future Directions. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Dering, J.; Conklin, D.; Kalous, O.; Cohen, D.J.; Desai, A.J.; Ginther, C.; Atefi, M.; Chen, I.; Fowst, C.; et al. PD 0332991, a Selective Cyclin D Kinase 4/6 Inhibitor, Preferentially Inhibits Proliferation of Luminal Estrogen Receptor-Positive Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines in Vitro. Breast Cancer Res. 2009, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, S.; Tan, A.R.; Rugo, H.S.; Aftimos, P.; Andrić, Z.; Beelen, A.; Zhang, J.; Yi, J.S.; Malik, R.; O’Shaughnessy, J. Trilaciclib Prior to Gemcitabine plus Carboplatin for Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Phase III PRESERVE 2. Futur. Oncol. 2022, 18, 3701–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zheng, L.; Sun, Z.; Li, J. CDK4/6 Inhibitor Resistance Mechanisms and Treatment Strategies (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palbociclib for Breast Cancer. Aust. Prescr. 2018, 41, 127–128. [CrossRef]

- Trilaciclib. LiverTox Clin. Res. Inf. Drug-Induced Liver Inj. 2012.

- Abraham, J.E.; O’Connor, L.O.; Grybowicz, L.; Alba, K.P.; Dayimu, A.; Demiris, N.; Harvey, C.; Drewett, L.M.; Lucey, R.; Fulton, A.; et al. Neoadjuvant PARP Inhibitor Scheduling in BRCA1 and BRCA2 Related Breast Cancer: PARTNER, a Randomized Phase II/III Trial. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, J.E.; Pinilla, K.; Dayimu, A.; Grybowicz, L.; Demiris, N.; Harvey, C.; Drewett, L.M.; Lucey, R.; Fulton, A.; Roberts, A.N.; et al. The PARTNER Trial of Neoadjuvant Olaparib with Chemotherapy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Nature 2024, 629, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woitek, R.; McLean, M.A.; Ursprung, S.; Rueda, O.M.; Garcia, R.M.; Locke, M.J.; Beer, L.; Baxter, G.; Rundo, L.; Provenzano, E.; et al. Hyperpolarized Carbon-13 MRI for Early Response Assessment of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer Patients. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 6004–6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.; Zhou, J.; Biyani, N.; Kathad, U.; Banerjee, P.P.; Srivastava, S.; Prucsi, Z.; Solarczyk, K.; Bhatia, K.; Ewesuedo, R.B.; et al. LP-184, a Novel Acylfulvene Molecule, Exhibits Anticancer Activity against Diverse Solid Tumors with Homologous Recombination Deficiency. Cancer Res. Commun. 2024, 4, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Fang, Y.; Labrie, M.; Li, X.; Mills, G.B. Systems Approach to Rational Combination Therapy: PARP Inhibitors. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020, 48, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardia, A.; Rugo, H.S.; Tolaney, S.M.; Loirat, D.; Punie, K.; Oliveira, M.; Brufsky, A.; Kalinsky, K.; Cortes, J.; Shaughnessy, J.O.; et al. Final Results from the Randomized Phase III ASCENT Clinical Trial in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Association of Outcomes by Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 and Trophoblast Cell Surface Antigen 2 Expression. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1738–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Kawaguchi-Sakita, N.; Ishida, T.; Nakayama, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Masuda, N.; Matsumoto, K.; Kogawa, T.; Sudo, K.; et al. Preliminary Results from ASCENT-J02: A Phase 1/2 Study of Sacituzumab Govitecan in Japanese Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 29, 1684–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frentzas, S.; Mislang, A.R.A.; Lemech, C.; Nagrial, A.; Underhill, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z.M.; Li, B.; Xia, Y.; Coward, J.I.G. Phase 1a Dose Escalation Study of Ivonescimab (AK112/SMT112), an Anti-PD-1/VEGF-A Bispecific Antibody, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, G.; Chen, J.; Zhuang, L.; Du, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhuang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, W.; et al. AK112, a Novel PD-1/VEGF Bispecific Antibody, in Combination with Chemotherapy in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): An Open-Label, Multicenter, Phase II Trial. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 62, 102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharenko, O.A.; Patel, R.G.; Calosing, C.; van der Horst, E.H. Combination of ZEN-3694 with CDK4/6 Inhibitors Reverses Acquired Resistance to CDK4/6 Inhibitors in ER-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022, 29, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.R.; Wright, G.S.; Thummala, A.R.; Danso, M.A.; Popovic, L.; Pluard, T.J.; Han, H.S.; Vojnović, Ž.; Vasev, N.; Ma, L.; et al. Trilaciclib plus Chemotherapy versus Chemotherapy Alone in Patients with Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Multicentre, Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1587–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.R.; Wright, G.S.; Thummala, A.R.; Danso, M.A.; Popovic, L.; Pluard, T.J.; Han, H.S.; Vojnović, Ž.; Vasev, N.; Ma, L.; et al. Trilaciclib Prior to Chemotherapy in Patients with Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Final Efficacy and Subgroup Analysis from a Randomized Phase II Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chave, K.J.; Auger, I.E.; Galivan, J.; Ryan, T.J. Molecular Modeling and Site-Directed Mutagenesis Define the Catalytic Motif in Human γ-Glutamyl Hydrolase. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 40365–40370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, R.; Schneider, E.; Ryan, T.J.; Galivan, J. Human Gamma-Glutamyl Hydrolase: Cloning and Characterization of the Enzyme Expressed in Vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996, 93, 10134–10138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Tissue-Based Map of the Human Proteome. Science (80-. ). 2015, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Liu, N.; Lin, J.; Wang, J.; Lai, H.; Liu, Y. HDAC7 Inhibits Cell Proliferation via NudCD1/GGH Axis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2023, 25, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubbar, E.; Helou, K.; Kovács, A.; Nemes, S.; Hajizadeh, S.; Enerbäck, C.; Einbeigi, Z. High Levels of γ-Glutamyl Hydrolase (GGH) Are Associated with Poor Prognosis and Unfavorable Clinical Outcomes in Invasive Breast Cancer. BMC Cancer 2013, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Cole, P.D.; Cho, R.C.; Ly, A.; Ishiguro, L.; Sohn, K.J.; Croxford, R.; Kamen, B.A.; Kim, Y.I. γ-Glutamyl Hydrolase Modulation and Folate Influence Chemosensitivity of Cancer Cells to 5-Fluorouracil and Methotrexate. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 2175–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, J.; Steadman, D.J.; Koli, S.; Ding, W.C.; Minor, W.; Bruce Dunlap, R.; Berger, S.H.; Lebioda, L. Structure of Human Thymidylate Synthase Suggests Advantages of Chemotherapy with Noncompetitive Inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 14170–14177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersona, D.D.; Quintero, C.M.; Stovera, P.J. Identification of a de Novo Thymidylate Biosynthesis Pathway in Mammalian Mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 15163–15168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, H.; Thareja, S.; Kumar, P. Regulation of Thymidylate Synthase: An Approach to Overcome 5-FU Resistance in Colorectal Cancer. Med. Oncol. 2023, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamizo, C.; Zazo, S.; Dómine, M.; Cristóbal, I.; García-Foncillas, J.; Rojo, F.; Madoz-Gúrpide, J. Thymidylate Synthase Expression as a Predictive Biomarker of Pemetrexed Sensitivity in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. BMC Pulm. Med. 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Unveiling the Oncogenic Significance of Thymidylate Synthase in Human Cancers. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2024, 16, 5228–5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, X.; Sun, H.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, H.; Shen, H. Thymidylate Synthase Promotes Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Growth by Relieving Oxidative Stress through Activating Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 Expression. PLoS One 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Schneider, B.P.; Li, L. A Bioinformatics Approach for Precision Medicine Off-Label Drug Selection among Triple Negative Breast Cancer Patients. J. Am. Med. Informatics Assoc. 2016, 23, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Tian, B.; Zhang, M.; Gao, X.; Jie, L.; Liu, P.; Li, J. Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Thymidylate Synthase Expression in Breast Cancer. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2021, 48, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.; Gollavilli, P.N.; Schwab, A.; Vazakidou, M.E.; Ersan, P.G.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Pluim, D.; Coggins, S.A.; Saatci, O.; Annaratone, L.; et al. Thymidylate Synthase Maintains the De-Differentiated State of Triple Negative Breast Cancers. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 2223–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, P.M.; Tyner, A.L. Building a Better Understanding of the Intracellular Tyrosine Kinase PTK6 - BRK by BRK. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Rev. Cancer 2010, 1806, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, A.R.; Kerkvliet, C.P.; Krutilina, R.I.; Playa, H.C.; Parke, D.N.; Thomas, W.A.; Smeester, B.A.; Moriarity, B.S.; Seagroves, T.N.; Lange, C.A. Breast Tumor Kinase (Brk/PTK6) Mediates Advanced Cancer Phenotypes via SH2-Domain Dependent Activation of RhoA and Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) Signaling. Mol. Cancer Res. 2021, 19, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubele, M.; Walch, A.K.; Ludyga, N.; Braselmann, H.; Atkinson, M.J.; Luber, B.; Auer, G.; Tapio, S.; Cooke, T.; Bartlett, J.M.S. Prognostic Value of Protein Tyrosine Kinase 6 (PTK6) for Long-Term Survival of Breast Cancer Patients. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 99, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Levine, K.; Gajiwala, K.S.; Cronin, C.N.; Nagata, A.; Johnson, E.; Kraus, M.; Tatlock, J.; Kania, R.; Foley, T.; et al. Small Molecule Inhibitors Reveal PTK6 Kinase Is Not an Oncogenic Driver in Breast Cancers. PLoS One 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmi, R.S.; Box, G.M.; Wazir, U.; Hussain, H.A.; Davies, J.A.; Court, W.J.; Eccles, S.A.; Jiang, W.G.; Mokbel, K.; Harvey, A.J. Breast Tumour Kinase (Brk/PTK6) Contributes to Breast Tumour Xenograft Growth and Modulates Chemotherapeutic Responses In Vitro. Genes (Basel). 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan Anderson, T.M.; Ma, S.H.; Raj, G. V.; Cidlowski, J.A.; Helle, T.M.; Knutson, T.P.; Krutilina, R.I.; Seagroves, T.N.; Lange, C.A. Breast Tumor Kinase (Brk/PTK6) Is Induced by HIF, Glucocorticoid Receptor, and PELP1-Mediated Stress Signaling in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 1653–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, K.; Park, S.H.; Nayak, A.; Byerly, J.H.; Irie, H.Y. PTK6 Inhibition Suppresses Metastases of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer via SNAIL-Dependent E-Cadherin Regulation. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 4406–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Qu, W.; Tu, J.; Yang, L.; Gui, X. Prognostic Impact of PTK6 Expression in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. BMC Womens. Health 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Barceló, J.M.; Lee, B.; Kohlhagen, G.; Zimonjic, D.B.; Popescu, N.C.; Pommier, Y. Human Mitochondrial Topoisomerase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001, 98, 10608–10613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baechler, S.A.; Factor, V.M.; Dalla Rosa, I.; Ravji, A.; Becker, D.; Khiati, S.; Miller Jenkins, L.M.; Lang, M.; Sourbier, C.; Michaels, S.A.; et al. The Mitochondrial Type IB Topoisomerase Drives Mitochondrial Translation and Carcinogenesis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L.; Lu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Hou, G. A Comprehensive Pan-Cancer Analysis of the Expression Characteristics, Prognostic Value, and Immune Characteristics of TOP1MT. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 920897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, M.; Srinivasan, S.; Raman, P.; Jiang, Y.; Kaufman, B.A.; Taylor, D.; Dong, D.; Chakrabarti, R.; Picard, M.; Carstens, R.P.; et al. Aggressive Triple Negative Breast Cancers Have Unique Molecular Signature on the Basis of Mitochondrial Genetic and Functional Defects. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, J.G.; O’Shaughnessy, J.A. The Hedgehog Pathway in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 2989–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Borrego, M.; Jimenez, B.; Antolín, S.; García-Saenz, J.A.; Corral, J.; Jerez, Y.; Trigo, J.; Urruticoechea, A.; Colom, H.; Gonzalo, N.; et al. A Phase Ib Study of Sonidegib (LDE225), an Oral Small Molecule Inhibitor of Smoothened or Hedgehog Pathway, in Combination with Docetaxel in Triple Negative Advanced Breast Cancer Patients: GEICAM/2012–12 (EDALINE) Study. Invest. New Drugs 2019, 37, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Qu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Yu, Y.; Deng, N.; Wawrowsky, K.; Zhang, X.; Li, N.; Bose, S.; Wang, Q.; et al. FOXC1 Activates Smoothened-Independent Hedgehog Signaling in Basal-like Breast Cancer. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 1046–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, A.Q.; Pegorari, M.S.; Nascimento, J.S.; de Oliveira, P.B.; Tavares, D.M. dos S. Incidence and Predictive Factors of Falls in Community-Dwelling Elderly: A Longitudinal Study. Cienc. e Saude Coletiva 2019, 24, 3507–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Naito, K.; Curry, E.J.; Li, X. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction With Achilles Tendon Allograft in a Patient With Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Orthop. J. Sport. Med. 2018, 6, 2325967118785170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Pang, J.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tan, J.; et al. Adverse Cardiovascular Effects of Phenylephrine Eye Drops Combined With Intravenous Atropine. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 596539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatiban, M.; Tohidi, S.; Shahdoust, M. The Effects of Applying an Assessment Form Based on the Health Functional Patterns on Nursing Student’s Attitude and Skills in Developing the Nursing Process. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 6, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vingiani, A.; Lorenzini, D.; Conca, E.; Volpi, C.C.; Trupia, D.V.; Gloghini, A.; Perrone, F.; Tamborini, E.; Dagrada, G.P.; Agnelli, L.; et al. Pan-TRK Immunohistochemistry as Screening Tool for NTRK Fusions: A Diagnostic Workflow for the Identification of Positive Patients in Clinical Practice. Cancer Biomarkers 2023, 38, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Program (TCGA) - NCI. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Curtis, C.; Shah, S.P.; Chin, S.F.; Turashvili, G.; Rueda, O.M.; Dunning, M.J.; Speed, D.; Lynch, A.G.; Samarajiwa, S.; Yuan, Y.; et al. The Genomic and Transcriptomic Architecture of 2,000 Breast Tumours Reveals Novel Subgroups. Nature 2012, 486, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, B.; Chin, S.F.; Rueda, O.M.; Vollan, H.K.M.; Provenzano, E.; Bardwell, H.A.; Pugh, M.; Jones, L.; Russell, R.; Sammut, S.J.; et al. The Somatic Mutation Profiles of 2,433 Breast Cancers Refines Their Genomic and Transcriptomic Landscapes. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.D.; Li, G.; Feng, Y.X.; Zhao, J.S.; Li, J.J.; Sun, Z.J.; Shi, S.; Deng, Y.Z.; Xu, J.F.; Zhu, Y.Q.; et al. EphB3 Is Overexpressed in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer and Promotes Tumor Metastasis by Enhancing Cell Survival and Migration. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Ji, X.D.; Gao, H.; Zhao, J.S.; Xu, J.F.; Sun, Z.J.; Deng, Y.Z.; Shi, S.; Feng, Y.X.; Zhu, Y.Q.; et al. EphB3 Suppresses Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Metastasis via a PP2A/RACK1/Akt Signalling Complex. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Sun, Z.J.; Yuan, Y.M.; Yin, F.F.; Bian, Y.G.; Long, L.Y.; Zhang, X.L.; Xie, D. EphB3 Stimulates Cell Migration and Metastasis in a Kinase-Dependent Manner through Vav2-Rho GTPase Axis in Papillary Thyroid Cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, S.T.; Chang, K.J.; Ting, C.H.; Shen, H.C.; Li, H.; Hsieh, F.J. Over-Expression of EphB3 Enhances Cell-Cell Contacts and Suppresses Tumor Growth in HT-29 Human Colon Cancer Cells. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jägle, S.; Rönsch, K.; Timme, S.; Andrlová, H.; Bertrand, M.; Jäger, M.; Proske, A.; Schrempp, M.; Yousaf, A.; Michoel, T.; et al. Silencing of the EPHB3 Tumor-Suppressor Gene in Human Colorectal Cancer through Decommissioning of a Transcriptional Enhancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 4886–4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, B.G.; Kim, H.S.; Bae, J.M.; Kim, W.H.; Hyun, C.L.; Kang, G.H. Expression Profile and Prognostic Significance of EPHB3 in Colorectal Cancer. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquale, E.B. Eph Receptors and Ephrins in Cancer Progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2024, 24, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, C.; Schmezer, P.; Plass, C.; Popanda, O. Epigenetics in Radiation-Induced Fibrosis. Oncogene 2015, 34, 2145–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Ito, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Hasegawa, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Taketani, T. Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide Synthase Deficiency Due to FLAD1 Mutation Presenting as Multiple Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenation Deficiency-like Disease: A Case Report. Brain Dev. 2019, 41, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fernández, M.; Ghosh, N.; Ellison, T.; McLeod, J.C.; Pelletier, C.A.; Williams, K. Moving beyond the Limitations of the Visual Analog Scale for Measuring Pain: Novel Use of the General Labeled Magnitude Scale in a Clinical Setting. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 93, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, L.; Srivastava, S.; Lindzen, M.; Sas-Chen, A.; Sheffer, M.; Lauriola, M.; Enuka, Y.; Noronha, A.; Mancini, M.; Lavi, S.; et al. SILAC Identifies LAD1 as a Filamin-Binding Regulator of Actin Dynamics in Response to EGF and a Marker of Aggressive Breast Tumors. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.Y.; Huang, Y.C.; Chiang, H.H.; Wu, Y.Y.; Wu, K.L.; Chang, Y.Y.; Liu, L.X.; Tsai, Y.M.; Hsu, Y.L. Ladinin 1 Shortens Survival via Promoting Proliferation and Enhancing Invasiveness in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, B.; Yang, S.J.; Park, S.M.; Lee, S.H.; Song, K.S.; Jeong, E.J.; Park, M.; Kim, J.S.; Yeom, Y. Il; Kim, J.A. LAD1 Expression Is Associated with the Metastatic Potential of Colorectal Cancer Cells. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abé, T.; Yamazaki, M.; Nozumi, M.; Maruyama, S.; Takamura, K.; Ohashi, R.; Ajioka, Y.; Tanuma, J.I. Ladinin-1 in Actin Arcs of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Is Involved in Cell Migration and Epithelial Phenotype. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, K.S.; Sheen, I.S.; Leu, C.M.; Tseng, P.H.; Chang, C.F. The Role of Smoothened in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riaz, N.; Burugu, S.; Cheng, A.S.; Leung, S.C.Y.; Gao, D.; Nielsen, T.O. Prognostic Significance of Csf-1r Expression in Early Invasive Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Showalter, C.A.; Manring, H.R.; Haque, S.J.; Chakravarti, A. “Oh, Dear We Are in Tribble”: An Overview of the Oncogenic Functions of Tribbles 1. Cancers (Basel). 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Guda, C. Integrative Exploration of Genomic Profiles for Triple Negative Breast Cancer Identifies Potential Drug Targets. Med. (United States) 2016, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O. and W.F. and N.E. The Metabolism of Tumors in the Body. J Gen Physiol 1927, 8, 519--530. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, Y.R.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Semaan, A.; Ahmed, Q.; Albashiti, B.; Jazaerly, T.; Nahleh, Z.; Ali-Fehmi, R. Glut-1 Expression Correlates with Basal-like Breast Cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2011, 4, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; ba-alawi, W.; Deblois, G.; Cruickshank, J.; Duan, S.; Lima-Fernandes, E.; Haight, J.; Tonekaboni, S.A.M.; Fortier, A.M.; Kuasne, H.; et al. GLUT1 Inhibition Blocks Growth of RB1-Positive Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Ming, J.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, L. Inhibition of Glut1 by WZB117 Sensitizes Radioresistant Breast Cancer Cells to Irradiation. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2016, 77, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.A.; Sutphin, P.D.; Nguyen, P.; Turcotte, S.; Lai, E.W.; Banh, A.; Reynolds, G.E.; Chi, J.T.; Wu, J.; Solow-Cordero, D.E.; et al. Targeting GLUT1 and the Warburg Effect in Renal Cell Carcinoma by Chemical Synthetic Lethality. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 94ra70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pliszka, M.; Szablewski, L.; Pliszka, M.; Szablewski, L. Glucose Transporters as a Target for Anticancer Therapy. Cancers 2021, Vol. 13, 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Li, X.; Xie, X.; Ye, F.; Chen, B.; Song, C.; Tang, H.; Xie, X. High Expressions of LDHA and AMPK as Prognostic Biomarkers for Breast Cancer. Breast 2016, 30, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.O.; Li, C.W.; Xia, W.; Lee, H.H.; Chang, S.S.; Shen, J.; Hsu, J.L.; Raftery, D.; Djukovic, D.; Gu, H.; et al. EGFR Signaling Enhances Aerobic Glycolysis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells to Promote Tumor Growth and Immune Escape. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 1284–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Bai, X.; Li, F.; Huang, L.; Hao, Y.; Li, W.; Bu, P.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Xie, J. Long Non-Coding RNA HANR Modulates the Glucose Metabolism of Triple Negative Breast Cancer via Stabilizing Hexokinase 2. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, K.C.; Wang, Q.; Bhaskar, P.T.; Miller, L.; Wang, Z.; Wheaton, W.; Chandel, N.; Laakso, M.; Muller, W.J.; Allen, E.L.; et al. Hexokinase 2 Is Required for Tumor Initiation and Maintenance and Its Systemic Deletion Is Therapeutic in Mouse Models of Cancer. Cancer Cell 2013, 24, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.; Porter, R.K.; McNamee, N.; Martinez, V.G.; O’Driscoll, L. 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose Inhibits Aggressive Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells by Targeting Glycolysis and the Cancer Stem Cell Phenotype. Sci. Reports 2019 91 2019, 9, 3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganapathy-Kanniappan, S.; Vali, M.; Kunjithapatham, R.; Buijs, M.; Syed, L.H.; Rao, P.P.; Ota, S.; Kwak, B.K.; Loffroy, R.; Geschwind, J.F. 3-Bromopyruvate: A New Targeted Antiglycolytic Agent and a Promise for Cancer Therapy. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2010, 999, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy-Kanniappan, S.; Geschwind, J.F.H. Tumor Glycolysis as a Target for Cancer Therapy: Progress and Prospects. Mol. Cancer 2013 121 2013, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutia, Y.D.; Babu, E.; Ganapathy, V. Re-Programming Tumour Cell Metabolism to Treat Cancer: No Lone Target for Lonidamine. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 1503–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Lu, Z.; Lv, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z. Tumor Metabolism Destruction via Metformin-Based Glycolysis Inhibition and Glucose Oxidase-Mediated Glucose Deprivation for Enhanced Cancer Therapy. Acta Biomater. 2022, 145, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-Inducible Factors: Mediators of Cancer Progression and Targets for Cancer Therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 33, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, A.; Decock, J. Lactate Metabolism and Immune Modulation in Breast Cancer: A Focused Review on Triple Negative Breast Tumors. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 598626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Hu, L.; Chen, T.; Li, F.; Yang, L.; Liang, B.; Wang, W.; Zeng, F. Lactate Dehydrogenase-A-Forming LDH5 Promotes Breast Cancer Progression. Breast cancer (Dove Med. Press. 2025, 17, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.J.; Seo, E.B.; Jeong, A.J.; Lee, S.H.; Noh, K.H.; Lee, S.; Cho, C.H.; Lee, C.H.; Shin, H.M.; Kim, H.R.; et al. The Acidic Tumor Microenvironment Enhances PD-L1 Expression via Activation of STAT3 in MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cells. BMC Cancer 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Xie, X.; Wang, H.; Xiao, X.; Yang, L.; Tian, Z.; Guo, X.; Zhang, L.; Tang, H.; Xie, X. PDL1 And LDHA Act as CeRNAs in Triple Negative Breast Cancer by Regulating MiR-34a. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 36, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, A.; Cooper, C.R.; Gouw, A.M.; Dinavahi, R.; Maitra, A.; Deck, L.M.; Royer, R.E.; Vander Jagt, D.L.; Semenza, G.L.; Dang, C. V. Inhibition of Lactate Dehydrogenase A Induces Oxidative Stress and Inhibits Tumor Progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 2037–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzio, E.; Mack, N.; Badisa, R.B.; Soliman, K.F.A. Triple Isozyme Lactic Acid Dehydrogenase Inhibition in Fully Viable MDA-MB-231 Cells Induces Cytostatic Effects That Are Not Reversed by Exogenous Lactic Acid. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Zeng, M.; Shan, W.; et al. Targeted Glucose or Glutamine Metabolic Therapy Combined With PD-1/PD-L1 Checkpoint Blockade Immunotherapy for the Treatment of Tumors - Mechanisms and Strategies. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shende, S.; Rathored, J.; Budhbaware, T. Role of Metabolic Transformation in Cancer Immunotherapy Resistance: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Discov. Oncol. 2025 161 2025, 16, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morotti, M.; Zois, C.E.; El-Ansari, R.; Craze, M.L.; Rakha, E.A.; Fan, S.J.; Valli, A.; Haider, S.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; Green, A.R.; et al. Increased Expression of Glutamine Transporter SNAT2/SLC38A2 Promotes Glutamine Dependence and Oxidative Stress Resistance, and Is Associated with Worse Prognosis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Wang, H.; Hong, J.; Wu, J.; Huang, O.; He, J.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Shen, K.; et al. Targeting Glutamine Metabolic Reprogramming of SLC7A5 Enhances the Efficacy of Anti-PD-1 in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier-Coles, G.; Bröer, A.; McLeod, M.D.; George, A.J.; Hannan, R.D.; Bröer, S. Identification and Characterization of a Novel SNAT2 (SLC38A2) Inhibitor Reveals Synergy with Glucose Transport Inhibition in Cancer Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, Y. Amino Acid Transporter LAT1 (SLC7A5) as a Molecular Target for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapeutics. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröer, S.; Bröer, S. Amino Acid Transporters as Targets for Cancer Therapy: Why, Where, When, and How. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, Vol. 21(2020, 21), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; Peiris-Pagés, M.; Pestell, R.G.; Sotgia, F.; Lisanti, M.P. Cancer Metabolism: A Therapeutic Perspective. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016 141 2016, 14, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidula, N.; Yau, C.; Rugo, H.S. Glutaminase (GLS1) Gene Expression in Primary Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer 2023, 30, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.I.; Demo, S.D.; Dennison, J.B.; Chen, L.; Chernov-Rogan, T.; Goyal, B.; Janes, J.R.; Laidig, G.J.; Lewis, E.R.; Li, J.; et al. Antitumor Activity of the Glutaminase Inhibitor CB-839 in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, J.J.; Telli, M.; Munster, P.; Voss, M.H.; Infante, J.R.; DeMichele, A.; Dunphy, M.; Le, M.H.; Molineaux, C.; Orford, K.; et al. A Phase I Dose-Escalation and Expansion Study of Telaglenastat in Patients with Advanced or Metastatic Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 4994–5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasseur, S.; Guillaumond, F. Lipids in Cancer: A Global View of the Contribution of Lipid Pathways to Metastatic Formation and Treatment Resistance. Oncogenesis 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Mi, S.; Ye, J.; Lou, G. Aberrant Lipid Metabolism in Cancer Cells and Tumor Microenvironment: The Player Rather than Bystander in Cancer Progression and Metastasis. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 7498–7506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, N.; Dhayer, M.; Boileau, M.; Fovez, Q.; Kluza, J.; Marchetti, P.; Germain, N.; Dhayer, M.; Boileau, M.; Fovez, Q.; et al. Lipid Metabolism and Resistance to Anticancer Treatment. Biol. 2020, Vol. 9 2020, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camarda, R.; Zhou, A.Y.; Kohnz, R.A.; Balakrishnan, S.; Mahieu, C.; Anderton, B.; Eyob, H.; Kajimura, S.; Tward, A.; Krings, G.; et al. Inhibition of Fatty Acid Oxidation as a Therapy for MYC-Overexpressing Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.X.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Yang, X.X.; Shen, W.R.; Yuan, L.W.; Ding, X.; Yu, Y.; Cai, W.Y. Unveiling the Impact of Lipid Metabolism on Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Growth and Treatment Options. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1579423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, M.; Pan, S.; Shan, B.; Diao, H.; Jin, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Han, S.; Liu, W.; He, J.; et al. Lipid Metabolic Reprograming: The Unsung Hero in Breast Cancer Progression and Tumor Microenvironment. Mol. Cancer 2025 241 2025, 24, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Qian, Z.; Wang, C.; Wu, D.; Liu, L.; Ning, X.; You, Y.; Mei, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y. Targeting B7-H3 Inhibition-Induced Activation of Fatty Acid Synthesis Boosts Anti-B7-H3 Immunotherapy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, 10924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bahlani, S.; Al-Lawati, H.; Al-Adawi, M.; Al-Abri, N.; Al-Dhahli, B.; Al-Adawi, K. Fatty Acid Synthase Regulates the Chemosensitivity of Breast Cancer Cells to Cisplatin-Induced Apoptosis. Apoptosis 2017, 22, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, H.A.; Bao, L.; Cheng, X.; Qin, Z.; Liu, C.J.; Heth, J.A.; Udager, A.M.; Soellner, M.B.; Merajver, S.D.; Morikawa, A.; et al. Targeting Fatty Acid Synthase in Preclinical Models of TNBC Brain Metastases Synergizes with SN-38 and Impairs Invasion. npj Breast Cancer 2024 101 2024, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giró-Perafita, A.; Palomeras, S.; Lum, D.H.; Blancafort, A.; Viñas, G.; Oliveras, G.; Pérez-Bueno, F.; Sarrats, A.; Welm, A.L.; Puig, T. Preclinical Evaluation of Fatty Acid Synthase and EGFR Inhibition in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4687–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camarda, R.; Zhou, A.Y.; Kohnz, R.A.; Balakrishnan, S.; Mahieu, C.; Anderton, B.; Eyob, H.; Kajimura, S.; Tward, A.; Krings, G.; et al. Inhibition of Fatty Acid Oxidation as a Therapy for MYC-Overexpressing Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Nat. Med. 2016 224 2016, 22, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Zou, Y.; Zhu, M.; Luo, Z.; Wu, T.; Zheng, C.; Xie, A.; Wang, H.; Fang, S.; Liu, S.; et al. Carnitine Palmitoyl Transferase 1A Is a Novel Diagnostic and Predictive Biomarker for Breast Cancer. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gao, T.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Ding, S.; Zhang, M.; Qin, Y.; Xue, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Inhibition of CPT1A Activates the CGAS/STING Pathway to Enhance Neutrophil-Mediated Tumor Abrogation in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Lett. 2025, 633, 217991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmi, R.R.; Kovatich, R.; Farley, A.; Sakthivel, K.M.; Takiar, V.; Sertorio, M. Targeting SREBP2 in Cancer Progression: Molecular Mechanisms, Oncogenic Crosstalk, and Therapeutic Interventions. Cell. Signal. 2025, 135, 112044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.X.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Yang, X.X.; Shen, W.R.; Yuan, L.W.; Ding, X.; Yu, Y.; Cai, W.Y. Unveiling the Impact of Lipid Metabolism on Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Growth and Treatment Options. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Hong, H.; Zhao, S.; Zou, X.; Ma, R.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, H. 3-Bromopyruvate Enhanced Daunorubicin-Induced Cytotoxicity Involved in Monocarboxylate Transporter 1 in Breast Cancer Cells. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015, 5, 2673–2685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Siddharth, S.; Parida, S.; Wu, X.; Sharma, D. Tumor Microenvironment: Key Players in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Immunomodulation. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Sun, X.; Wang, K. From Cold to Hot Tumors: Feasibility of Applying Therapeutic Insights to TNBC. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L.; Jackson, H.W.; Eling, N.; Zhao, S.; Usui, G.; Dakhli, H.; Schraml, P.; Dettwiler, S.; Elfgen, C.; Varga, Z.; et al. A Stratification System for Breast Cancer Based on Basoluminal Tumor Cells and Spatial Tumor Architecture. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 1637–1655.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruosso, T.; Gigoux, M.; Manem, V.S.K.; Bertos, N.; Zuo, D.; Perlitch, I.; Saleh, S.M.I.; Zhao, H.; Souleimanova, M.; Johnson, R.M.; et al. Spatially Distinct Tumor Immune Microenvironments Stratify Triple-Negative Breast Cancers. J. Clin. Invest. 2019, 129, 1785–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. Biology and Management of Patients With Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Oncologist 2016, 21, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terragno, M.; Vetrova, A.; Semenov, O.; Sayan, A.E.; Kriajevska, M.; Tulchinsky, E. Mesenchymal–Epithelial Transition and AXL Inhibitor TP-0903 Sensitise Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells to the Antimalarial Compound, Artesunate. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, M.; Shyanti, R.K.; Mishra, M.K. Targeted Therapy Approaches for Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, O.; Leclere, R.; Nicolas, A.; Meseure, D.; Marchiò, C.; Vincent-Salomon, A.; Roman-Roman, S.; Schoumacher, M.; Dubois, T. AXL Controls Directed Migration of Mesenchymal Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Cells 2020, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Al Raffa, F.; Dai, M.; Moamer, A.; Khadang, B.; Hachim, I.Y.; Bakdounes, K.; Ali, S.; Jean-Claude, B.; Lebrun, J.-J. Dasatinib Sensitises Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells to Chemotherapy by Targeting Breast Cancer Stem Cells. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 1495–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Motta, L.L.; Ledaki, I.; Purshouse, K.; Haider, S.; De Bastiani, M.A.; Baban, D.; Morotti, M.; Steers, G.; Wigfield, S.; Bridges, E.; et al. The BET Inhibitor JQ1 Selectively Impairs Tumour Response to Hypoxia and Downregulates CA9 and Angiogenesis in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Oncogene 2017, 36, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, M.; Kanaya, N.; Wu, S. V.; Mendez, C.; Nguyen, D.; Luu, T.; Chen, S. Targeting Breast Cancer Stem Cells in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Using a Combination of LBH589 and Salinomycin. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 151, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhu, Y.; Guan, G.; Liu, M. Napabucasin Targets Resistant Triple Negative Breast Cancer through Suppressing STAT3 and Mitochondrial Function. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2025, 95, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari-Amorotti, G.; Chiodoni, C.; Shen, F.; Cattelani, S.; Soliera, A.R.; Manzotti, G.; Grisendi, G.; Dominici, M.; Rivasi, F.; Colombo, M.P.; et al. Suppression of Invasion and Metastasis of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Lines by Pharmacological or Genetic Inhibition of Slug Activity. Neoplasia 2014, 16, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, T.; Malik, L.; McCuaig, R.D.; Tu, W.J.; Wu, F.; Lim, P.S.; Tan, A.H.Y.; Dahlstrom, J.E.; Clingan, P.; Moylan, E.; et al. A Phase 1 Proof of Concept Study Evaluating the Addition of an LSD1 Inhibitor to Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced or Metastatic Breast Cancer (EPI-PRIMED). Front. Oncol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez–Nájera, L.E.; Chanona–Pérez, J.J.; Valdivia–Flores, A.; Marrero–Rodríguez, D.; Salcedo–Vargas, M.; García–Ruiz, D.I.; Castro– Reyes, M.A. Morphometric Study of Adipocytes on Breast Cancer by Means of Photonic Microscopy and Image Analysis. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2018, 81, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zeng, H.; Li, J.; Zeng, N.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, K.; Li, J.; Yu, J.; Wu, Y. Dissecting the Emerging Role of Cancer-Associated Adipocyte-Derived Cytokines in Remodeling Breast Cancer Progression. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Wang, Z.; Hong, J.; Wu, J.; Huang, O.; He, J.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Shen, K. Targeting Cancer-Associated Adipocyte-Derived CXCL8 Inhibits Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Progression and Enhances the Efficacy of Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tiruthani, K.; Wang, M.; Zhou, X.; Qiu, N.; Xiong, Y.; Pecot, C. V.; Liu, R.; Huang, L. Tumor-Targeted Gene Therapy with Lipid Nanoparticles Inhibits Tumor-Associated Adipocytes and Remodels the Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Nanoscale Horizons 2021, 6, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.; Camarda, R.; Malkov, S.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Manning, S.; Aran, D.; Beardsley, A.; Van de Mark, D.; Nakagawa, R.; Chen, Y.; et al. Tumor Cell-Adipocyte Gap Junctions Activate Lipolysis and Contribute to Breast Tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, D.; Fang, N.; Zhu, Y.; Bao, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, R.; Huang, J.; Wu, Q.; Ma, F.; et al. Adipocytes-Induced ANGPTL4/KLF4 Axis Drives Glycolysis and Metastasis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.P.; An, K.; Ito, Y.; Kharbikar, B.N.; Sheng, R.; Paredes, B.; Murray, E.; Pham, K.; Bruck, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. Implantation of Engineered Adipocytes Suppresses Tumor Progression in Cancer Models. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, J.; Qian, H.; Zhuang, Q. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: From Basic Science to Anticancer Therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogna, M.R.; Varone, V.; DelSesto, M.; Ferrara, G. The Role of CAFs in Therapeutic Resistance in Triple Negative Breast Cancer: An Emerging Challenge. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, K.; Le, A.; Weaver, V.M.; Werb, Z. Targeting the Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts as a Treatment in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 82889–82901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, K.; Watabe, T.; Kaneda-Nakashima, K.; Shirakami, Y.; Kadonaga, Y.; Naka, S.; Ooe, K.; Toyoshima, A.; Giesel, F.; Usui, T.; et al. Evaluation of Targeted Alpha Therapy Using [211At]FAPI1 in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Xenograft Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, W.; Chen, B.; Li, X.; Zhao, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, N.; Wang, X.; Luo, D.; Liang, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Secrete CSF3 to Promote TNBC Progression via Enhancing PGM2L1-Dependent Glycolysis Reprogramming. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xian, P.; Zou, L.; Zhang, J.; Pan, X.; Song, Y.; Nan, Y.; Pu, Q.; Liu, H.; Green, D.; Ni, S.; et al. Precision Targeted Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Nano-Regulator Enhanced Chemo-Immunotherapy for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Biomaterials 2026, 326, 123679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhang, H.; Yang, B.B.; Qadir, J.; Yuan, H.; Ye, T. Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells State-Implications for Various Breast Cancer Subtypes. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, D.; Wolf, D.M.; van ’t Veer, L.; Esserman, L.; Campbell, M.; Yau, C. Co-Expression Modules Identified from Published Immune Signatures Reveal Five Distinct Immune Subtypes in Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 161, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Li, S.; Xue, J.; Qi, M.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y.; Hu, J.; Dong, H.; Ling, K. PD-L1 Tumor-Intrinsic Signaling and Its Therapeutic Implication in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. JCI Insight 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhuang, C.; Liu, L.; Xiong, L.; Xie, X.; He, P.; Li, J.; Wei, B.; Yan, X.; Tian, T.; et al. Exploratory Phase II Trial of an Anti-PD-1 Antibody Camrelizumab Combined with a VEGFR-2 Inhibitor Apatinib and Chemotherapy as a Neoadjuvant Therapy for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (NeoPanDa03): Efficacy, Safety and Biomarker Analysis. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucchi, S.; Borea, R.; Garcia-Recio, S.; Zingarelli, M.; Rädler, P.D.; Camerini, E.; Marnata Pellegry, C.; O’Connor, S.; Earp, H.S.; Carey, L.A.; et al. B7-H3 and CSPG4 Co-Targeting as Pan-CAR-T Cell Treatment of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Chen, M.; Shi, B.; Di, S.; Sun, R.; Jiang, H.; Li, Z. Radiation Enhances the Efficacy of EGFR-Targeted CAR-T Cells against Triple-Negative Breast Cancer by Activating NF-ΚB/Icam1 Signaling. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 3379–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierini, S.; Gabbasov, R.; Oliveira-Nunes, M.C.; Qureshi, R.; Worth, A.; Huang, S.; Nagar, K.; Griffin, C.; Lian, L.; Yashiro-Ohtani, Y.; et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor Macrophages (CAR-M) Sensitize HER2+ Solid Tumors to PD1 Blockade in Pre-Clinical Models. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Goedegebuure, S.P.; Chen, M.Y.; Mishra, R.; Zhang, F.; Yu, Y.Y.; Singhal, K.; Li, L.; Gao, F.; Myers, N.B.; et al. Neoantigen DNA Vaccines Are Safe, Feasible, and Induce Neoantigen-Specific Immune Responses in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Patients. Genome Med. 2024, 16, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vora, H.H. Identification of Extra Cellular Matrix (ECM) Genes in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Asian Pacific J. Cancer Biol. 2025, 10, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Temaimi, R.; Ahmad, R.; Al-Mulla, F. MMP14 and DDR2 Are Potential Molecular Markers for Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festari, M.F.; Jara, E.; Costa, M.; Iriarte, A.; Freire, T. Truncated O-Glycosylation in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Reveals a Gene Expression Signature Associated with Extracellular Matrix and Proteolysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Paul, S.; Ghosh, A.; Gupta, S.; Mukherjee, T.; Shankar, P.; Sharma, A.; Keshava, S.; Chauhan, S.C.; Kashyap, V.K.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles in Triple–Negative Breast Cancer: Immune Regulation, Biomarkers, and Immunotherapeutic Potential. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15, 4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, B.; Torres, M. Radiotherapy in Triple Negative Breast Cancer – Current Standards and Future Directions. Curr. Breast Cancer Rep. 2025, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Cai, H.; Xu, C.; Zhai, H.; Lux, F.; Xie, Y.; Feng, L.; Du, L.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; et al. AGuIX Nanoparticles Enhance Ionizing Radiation-Induced Ferroptosis on Tumor Cells by Targeting the NRF2-GPX4 Signaling Pathway. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Lin, X.; Wang, X.; Cai, L.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, Z. Enhancing Radiosensitivity in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer through Targeting ELOB. Breast Cancer 2024, 31, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AN, J.; CHU, K.; ZHOU, Q.; MA, H.; HE, Q.; ZHANG, Y.; LV, J.; WEI, H.; LI, M.; WU, Z.; et al. Radiosensitizer-Based Injectable Hydrogel for Enhanced Radio-Chemotherapy of TNBC. Chinese J. Anal. Chem. 2024, 52, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaranarayanan, R.A.; Florea, A.; Allekotte, S.; Vogg, A.T.J.; Maurer, J.; Schäfer, L.; Bolm, C.; Terhorst, S.; Classen, A.; Bauwens, M.; et al. Correction: PARP Targeted Auger Emitter Therapy with [125I]PARPi-01 for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. EJNMMI Res. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| TRIAL | INVESTIGATIONAL DRUG | TARGET | YEAR | PHASE | STATE | RESULTS | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FASCINATE-N (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT05582499) |

New targeted drugs | PARPi,Trop-2, Antibody–drug conjugates, CDK 4/6 inhibitors, PD-L1 mAb, HER2 inhibitor, anti-angiogenic agents | 2022-2028 (estimated) | II | Recruiting | N.A. | [25] |

| TROPION-Breast05 (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT06103864) | Durvalumab (Imfinzi) | Anti PD-L1 | 2023-2029 (estimated) | III | Recruiting | N.A. | [34] |

| NCT03170960 | Atezolizumab (Tecentriq) | Anti PD-L1 | 2017-2027 (estimated) | I | Active, not recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| PAveMenT (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT04360941) | Avelumab (Bavencio) | Anti PD-L1 | 2026-2026 (estimated) | I | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT02936102 | FAZ053 | Anti PD-L1 | 2016-2024 | I | Terminated | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT04916002 | Cemiplimab | Anti PD-1 | 2021-2024 | II | Terminated | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT03549000 |

PDR001 |

Anti PD-1 | 2018-2022 | I | Terminated | N.A. | N.A. |

| PARTNER (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT03150576) | Olaparib | PARP | 2016-2034 (estimated) | II-III | Recruiting | N.A. | [86,87,88] |

| NCT05933265 | LP-184 | PARP | 2023-2025 (estimated) | I-II | Recruiting | N.A. | [89] |

| NCT03875313 | Telaglenastat (CB-839), Talazoparib | PARP | 2019-2022 | I-II | Terminated | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT03801369 | Olaparib | PARP | 2018-2024 | II | Terminated | N.A. | [90] |

| NCT04916002 | Vidutolimod, Cemiplimab | PARP | 2021-2024 | II | Terminated | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT05252390 | NUV-868, Olaparib, Enzalutamide | PARP | 2022-2024 | I | Terminated | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT02419495 | Selinexor (KPT-330) | PARP | 2015-2024 | I | Terminated | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT02627430 | Talazoparib, Hsp90 Inhibitor AT13387 | PARP | 2016-2019 | I | Withdrawn | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT07046455 | Sacituzumab Govitecan (SG) and PET Probes | Trop-2 | 2025-2027 (estimated) | N.A. | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| FUTURE2.0 (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT05749588) | SHR-A1811, TROP2 ADC, BP102 | Trop-2 | 2023-2026 (estimated) | II | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| BALISTA (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT06793332) | IvoneScimab, Trop2 ADC | Trop-2 | 2024-2027 (estimated) | II | Recruiting | N.A. | [91,92,93,94] |

| NCT06851299 | Trop2-ADC monotherapy | Trop-2 | 2025-2028 (estimated) | II | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| MK-2870-011/ TroFuse-011 (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT06841354) |

Sacituzumab Tirumotecan (Sac-TMT, MK-2870) and Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) | Trop-2 |

2025-2030 (estimated) | III | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT06878625 | Trop-2 ADC Combination Therapy | Trop-2 | 2024-2027 (estimated) | II | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT06649331 | Anti Trop-2 antibody-conjugated drugs (ADCs) | Trop-2 | 2024-2027 (estimated) | II | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| TROPION-DM (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT06974604) | Dexamethasone | Trop-2 | 2025-2029 (estimated) | II | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT06103864 |

Dato-DXd | Trop-2 |

2023-2029 (estimated) | III | Recruiting | N.A. | [34] |

| NCT03901469 | ZEN003694, Talazoparib | Trop-2 | 2019-2024 | II | Terminated | N.A. | [95] |

| ASPRIA (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT04434040) | Sacituzumab govitecan, Atezolizumab |

Trop-2 | 2020-2027 (estimated) | II | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| NeoSACT (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT04877821) | Anlotinib (FOCUS V) | Antiangiogenic agent | 2021-2025 | II | Active, not recruiting | pCR: 69% MRD: 86.2% 2y EFS: 92.4% |

[66] |

| NCT06724263 | B1962 | Antiangiogenic agent | 2024-2026 (estimated) | II | Not yet recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT06189209 | Tenalisib | PI3K inhibitor | 2024-2026 (estimated) | II | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT03218826 | AZD8186 | PI3K inhibitor | 2024-2026 (estimated) | I | Active, not recruiting | MTD: NR Anemia: 57% Diarrhea: 43% Fatigue: 43% |

[71] |

| SABINA (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT05810870) | MEN1611 | PI3K inhibitor | 2023-2027 (estimated) | II | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| BCTOP-T-M03 (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05954442) | Everolimus (Afinitor) | PI3K inhibitor | 2023-2026 (estimated) | III | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT01918306 | GDC-0941 | PI3K inhibitor | 2013-2015 | I-II | Terminated | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT02457910 | Taselisib | PI3K inhibitor | 2015-2022 | I-II | Terminated | N.A. | |

| NCT04216472 | Alpelisib | PI3K inhibitor | 2020-2025 | II | Terminated | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT02476955 | ARQ-092 | PI3K inhibitor | 2015-2019 | I | Terminated | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT03090165 | Bicalutamide (Casodex) | AR inhibitor | 2018-2025 (estimated) | I-II | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT07016399 | Darolutamide (Nubeqa) | AR inhibitor | 2025-2033 (estimated) | II | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| CAREGIVER (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05067530) | Palbociclib (Ibrance) | CDK 4/6 inhibitor | 2022-2026 (estimated) | II | Not yet recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| CHARGE (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT04315233) | Ribociclib | CDK 4/6 inhibitor | 2021-2026 (estimated) | I | Recruiting | N.A. | N.A. |

| NCT02978716 | Trilaciclib | CDK 4/6 inhibitor | 2017-2020 | II | Terminated | See publication | [96,97] |

| NCT05113966 | Trilaciclib | CDK 4/6 inhibitor | 2021-2024 | II | Terminated | PFS: 4.1 months ORR: 23.3% CBR: 46.7% DoR: 8.8 months OS: 15.9% |

N.A. |

| NCT03519178 | PF-06873600 | CDK 4/6 inhibitor | 2018-2024 | I-II | Terminated | N.A. | |

| NCT06264921 | NKT3447 | CDK 4/6 Inhibitor | 2024-2025 | I | Terminated | N.A. | N.A. |

| Gene Symbol | Protein Name | UniProt link |

|---|---|---|

| GGH | Gamma-glutamyl hydrolase | Q92820 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q92820/entry) |

| TYMS | Thymidylate synthase | P04818 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/P04818/entry) |

| PTK6 | Protein-tyrosine kinase 6 (BRK) | Q13882 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q13882/entry) |

| TOP1MT | DNA topoisomerase I, mitochondrial | Q969P6 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q969P6/entry) |

| SMO | Smoothened receptor | Q99835 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q99835/entry) |

| CSF1R | Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor | P07333 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/P07333/entry) |

| EPHB3 | Ephrin type-B receptor 3 | P54753 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/P54753/entry) |

| TRIB1 | Tribbles pseudokinase 1 | Q96RU8 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q96RU8/entry) |

| LAD1 | Ladinin-1 | O00515 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/O00515/entry) |

| Altered metabolic pathway | Main molecular targets | Role in TNBC | Targeting strategies | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced glycolysis (Warburg effect) | GLUT-1 | Increased glucose uptake; high proliferative index, high histological grade, drug resistance and basal-like phenotype | STF-31, WZB-117, BAY-876, shRNA | [156,157,158,159] |

| HK2 | Promotes ATP production and apoptosis resistance via interaction with VDAC | 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), 3-bromopyruvate, lonidamine, metformin | [164,167,168,202] | |

| LDH (LDH-A isoform) |

Sustains glycolysis under hypoxia; promotes invasion, immune evasion and acidic tumor microenvironment | FX11, GNE-140 | [174,175] | |

| Hypoxia-driven metabolic regulation | HIF-1α | Transcriptionally upregulates HK2 and LDH, enabling survival under oxygen deprivation | Indirect targeting through glycolytic inhibition | [62,169] |

| Glutamine addiction | Glutamine transporters (SNAT2/SLC38A2, SLC7A5) | Increased glutamine uptake, increased TCA cycle, nucleotide biosynthesis and redox homeostasis | Specific transporter inhibitors | [178,179,182] |

| GLS1 | Fuels TCA cycle, ATP production and antioxidant defenses | Telaglenastat | [184,186] | |

| De novo lipogenesis | FASN | Supports tumor growth, aggressiveness and therapy resistance; overexpression correlates with poor prognosis | TVB-2640, C75 | [195,196] |

| Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) | CPT1A | Promotes adaptation to nutrient and oxygen stress | Etomoxir, perhexiline | [198,199] |

| Lipid metabolism transcriptional control | SREBPs | Master regulators of lipid biosynthesis; frequently upregulated in TNBC | No effective validated inhibitors | [193,200] |