Submitted:

11 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System description and study objects

2.2. Experimental design and control configuration

2.3. Measurement methods and quality control

2.4. Data processing and model formulation

2.5. Optimization procedure and validation

3. Results and Discussion

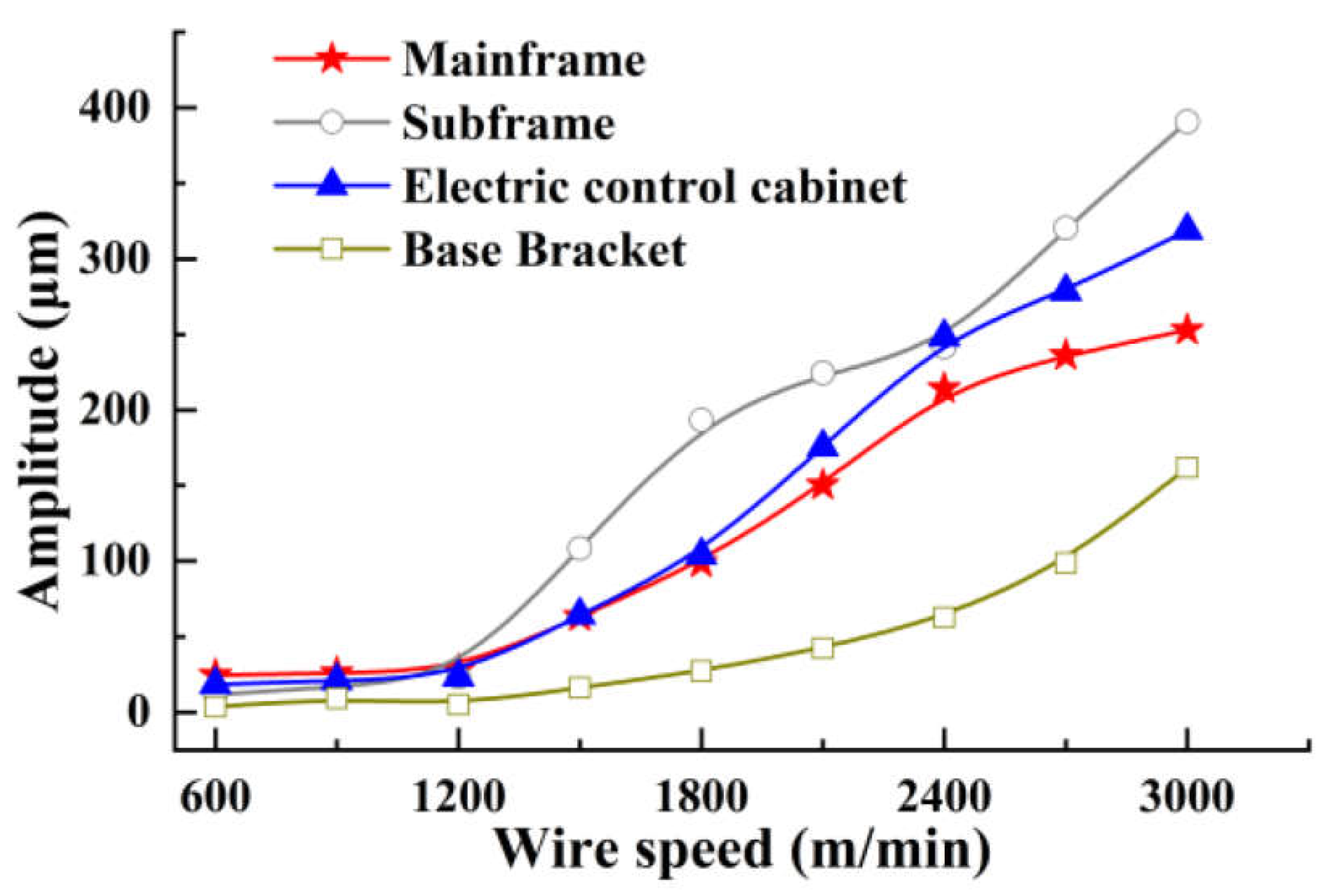

3.1. Vibration response of the baseline structure

3.2. Sensitivity results and dominant design parameters

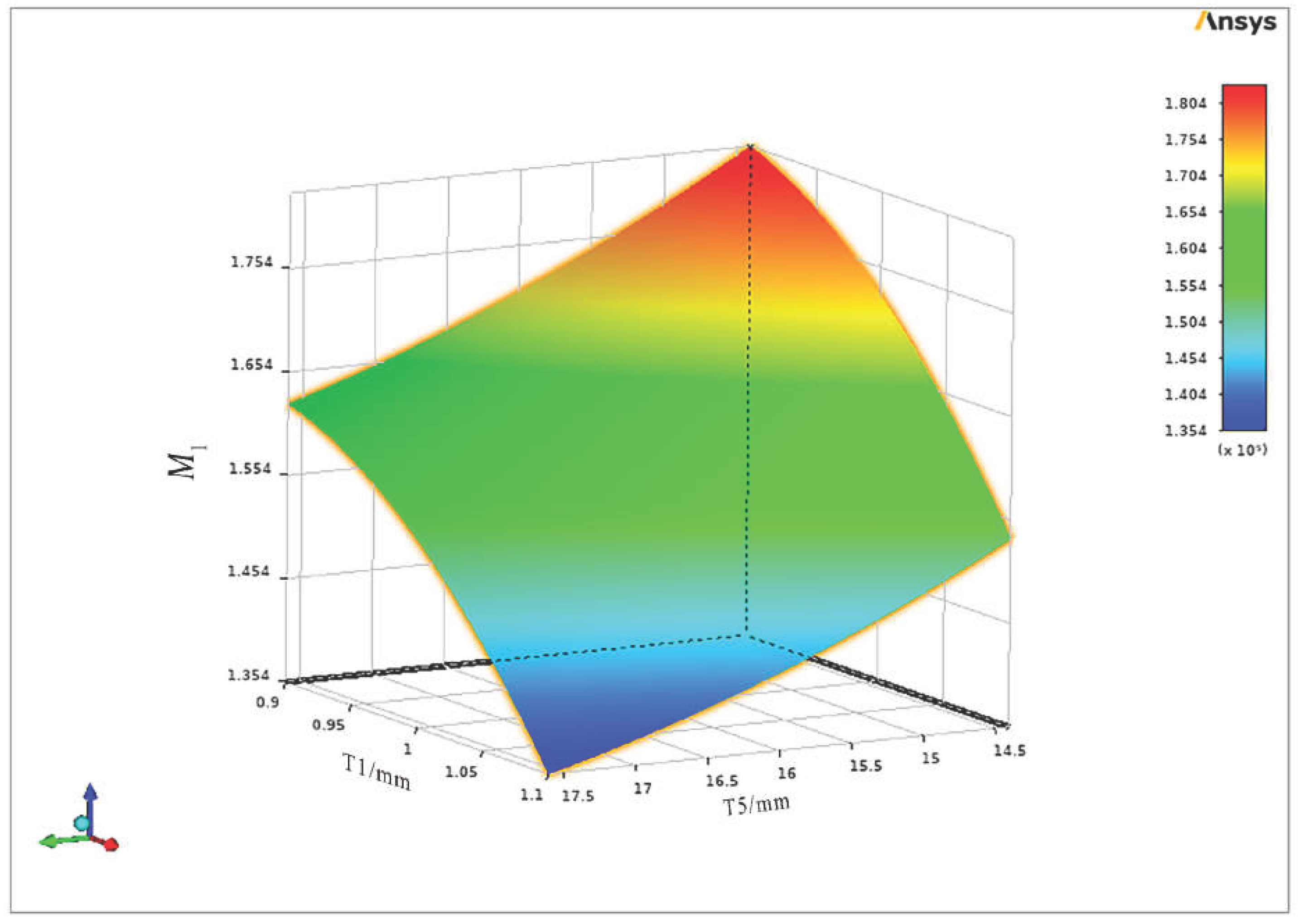

3.3. Response surface behavior and parameter interaction

3.4. Optimization outcome and comparison with published studies

4. Conclusion

References

- Luan, X.; Yu, H.; Ding, C.; Zhang, Y.; He, M.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y. A Review of Research on Precision Rotary Motion Systems and Driving Methods. Applied Sciences 2025, 15(12), 6745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liang, H.; Yue, L.; Xu, P.; Li, S. Low-Power Acceleration Architecture Design of Domestic Smart Chips for AI Loads. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bhosle, S. M.; Bhosale, S. S.; Mahadik, S. C.; Pondkule, S. M. Exploring research trends in use of finite element analysis for optimization of stress concentration factor in bars with fillets. Discover Mechanical Engineering 2025, 4(1), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Wang, B.; Su, S.; Qin, W. Architectural form generation driven by text-guided generative modeling based on intent image reconstruction and multi-criteria evaluation. Authorea Preprints. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi, S. M.; Parvizi, S.; Baghbanijavid, H.; Tan, A. T.; Nematollahi, M.; Ramazani, A.; Elahinia, M. Computational modelling of process–structure–property–performance relationships in metal additive manufacturing: A review. International Materials Reviews 2022, 67(1), 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, H.; Wang, B.; Lu, Y.; Fu, Y. Computational Modeling-Based Estimation of Residual Stress and Fatigue Life of Medical Welded Structures. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M. A.; Haque, E. A. Advances And Limitations Of Fracture Mechanics–Based Fatigue Life Prediction Approaches For Structural Integrity Assessment: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 2022, 3(03), 68–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J. B.; Gao, X. Q. Alliance or no alliance—Bargaining power in competing reverse supply chains. European Journal of Operational Research 2014, 233(2), 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S. H. S.; Hajzargarbashi, S.; Liu, Z. Enhancing robotic manipulator performance through analyzing vibration, identifying deep-learning-based modal parameters, and estimating frequency response functions. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Cao, J.; Su, X.; Tian, Q. Zero-Shot Knowledge Extraction with Hierarchical Attention and an Entity-Relationship Transformer. 2025 5th International Conference on Sensors and Information Technology, 2025, March; IEEE; pp. 356–360. [Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu, D. B.; Todoh, M.; Huang, S. J. Hybrid Biomechanical design of dental implants: integrating solid and gyroid triply periodic minimal surface lattice architectures for optimized stress distribution. Journal of Functional Biomaterials 2025, 16(2), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zar, A.; Hussain, Z.; Akbar, M.; Rabczuk, T.; Lin, Z.; Li, S.; Ahmed, B. Towards vibration-based damage detection of civil engineering structures: overview, challenges, and future prospects. International Journal of Mechanics and Materials in Design 2024, 20(3), 591–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narumi, K.; Qin, F.; Liu, S.; Cheng, H. Y.; Gu, J.; Kawahara, Y.; Yao, L. Self-healing UI: Mechanically and electrically self-healing materials for sensing and actuation interfaces. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, 2019, October; pp. 293–306. [Google Scholar]

- Remache, A.; Pérez-Sánchez, M.; Hidalgo, V. H.; Ramos, H. M. Hybrid Optimization Approaches for Impeller Design in Turbomachinery: Methods, Metrics, and Design Strategies. Water 2025, 17(13). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H. High-Efficiency Dual-Band 8-Port MIMO Antenna Array for Enhanced 5G Smartphone Communications. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Information 2024, 1, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. C.; Cheong, S. K.; Noguchi, H. Residual stress relaxation and low-and high-cycle fatigue behavior of shot-peened medium-carbon steel. International Journal of Fatigue 2013, 56, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, H.; Zhu, J.; Yao, Y. Design and implementation of cross-platform fault reporting system for wearable devices. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- El-Khoury, O.; Adeli, H. Recent advances on vibration control of structures under dynamic loading. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2013, 20(4), 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Vasudev, H. A review on smart welding systems: AI integration and sensor-based process optimization. Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Systems 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liang, H.; Li, S.; Yue, L.; Xu, P. Design of Domestic Chip Scheduling Architecture for Smart Grid Based on Edge Collaboration. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Research on intelligent prediction of vibration performance and multi-objective optimization using CGWOA-RBF enhanced neural network and MOCGWOA-based optimization algorithm. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, 2025; ISSN 09544062251395655. [Google Scholar]

- Bourouina, H.; Derguini, N.; Yahiaoui, R. Coupling spring-induced resonance shift in PDNB system with PSH network. Microsystem Technologies 2023, 29(1), 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).