1. Introduction

Soil management practices that enhance aggregation aim to increase plant productivity and organic carbon (C) inputs while reducing disturbance and losses through decomposition and erosion. Well-structured soil improves air–water relationships, nutrient cycling, biological activity and the formation of organo-mineral complexes, ultimately reducing erosion and improving water quality [

1]. Aggregate formation and structural improvement are promoted by management strategies that minimize disturbance, enhance fertility, increase organic inputs, maintain continuous plant cover and limit SOC decomposition [

2].

Tillage practices play a central role in regulating soil structure. No-tillage (NT) systems generally improve aggregate stability, soil aggregation and aggregate-associated SOC due to reduced soil disturbance and the retention of crop residues, compared with conventional tillage (CT) [

3]. However, the magnitude of these effects varies with climate, experimental duration, agronomic practices and inherent soil properties [

4]. Reduced disturbance under NT enhances microbial activity and SOC accumulation, promoting the gradual formation of macroaggregates [

5,

6] and increasing SOC levels that contribute to aggregate stabilization [

7].

Tillage also strongly influences the distribution and stabilization of particulate organic matter (POM). Under CT, repeated mechanical disruption reduces the formation and protection of POM within microaggregates, accelerating decomposition once macroaggregates disintegrate. In contrast, NT slows aggregate turnover and enhances POM stabilization [

8]. Beyond the labile POM pool, mineral-associated organic carbon (MAOC) is also affected; MAOC increases by 7–13 % in the 0–10 cm layer under NT and chisel systems relative to CT [

3]. Some studies attribute SOC gains after transitioning from CT to NT primarily to increases in the labile POC fraction [

9]. Furthermore, NT promotes larger macroaggregates (5–2 mm), increases aggregate stability and enhances SOC, DOC and POC, especially in large macroaggregates [

10].

Several structural indices have been used to quantify tillage effects. The mean weight diameter (MWD) increases significantly under NT in the 0–10 cm layer [

11], while the geometric mean diameter (GMD) shows similar responses [

12]. A meta-analysis confirmed that conservation tillage significantly increases MWD, GMD and water-stable aggregates (WSA), with stronger effects in long-term trials [

13]. The Dm index has been used to compare structural responses to different implements, with minimum tillage showing the lowest Dm values [

14]. Dm is well suited to describe dry aggregate size distribution (DASD) across soil types, while the Rosin–Rammler parameter (Dn) is more appropriate for comparing management practices within a single soil type [

15].

Soil texture also modulates aggregation and SOC stabilization. Organic matter associated with clay minerals enhances aggregate cohesion and resistance to slaking [

16]. Higher clay content promotes macroaggregation and protects intra-aggregate POM [

17], whereas low-clay soils exhibit weaker macroaggregation and faster POM decomposition.

Despite extensive research on conservation tillage effects, critical knowledge gaps remain. First, most studies compare only two time points or systems, making it difficult to distinguish transitional effects from long-term equilibria. Second, while texture is known to influence SOC dynamics, few studies directly compare tillage responses across contrasting soil textures within the same climatic zone and management history. Third, the relative sensitivity of different C fractions to tillage intensity across textures remains poorly quantified, limiting our ability to predict system responses and select appropriate monitoring indicators.

We hypothesized that: (i) conservation tillage would enhance SOC fractions and structural stability in both contrasting soil textures, but with greater magnitude and detectability in lower-clay soils due to reduced baseline protection; (ii) transitional responses (5-year NT) would be evident in labile C pools (POX-C, POC) and aggregate properties, while long-term effects (11-year MT) would manifest in more stable fractions (MAOC); and (iii) structural improvements would correlate with C fraction changes, with relationships varying by texture.

We tested these hypotheses using a dual time-scale design combining 11 years of MT with 5-year NT transitions (from both CT and MT baselines) in contrasting textures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

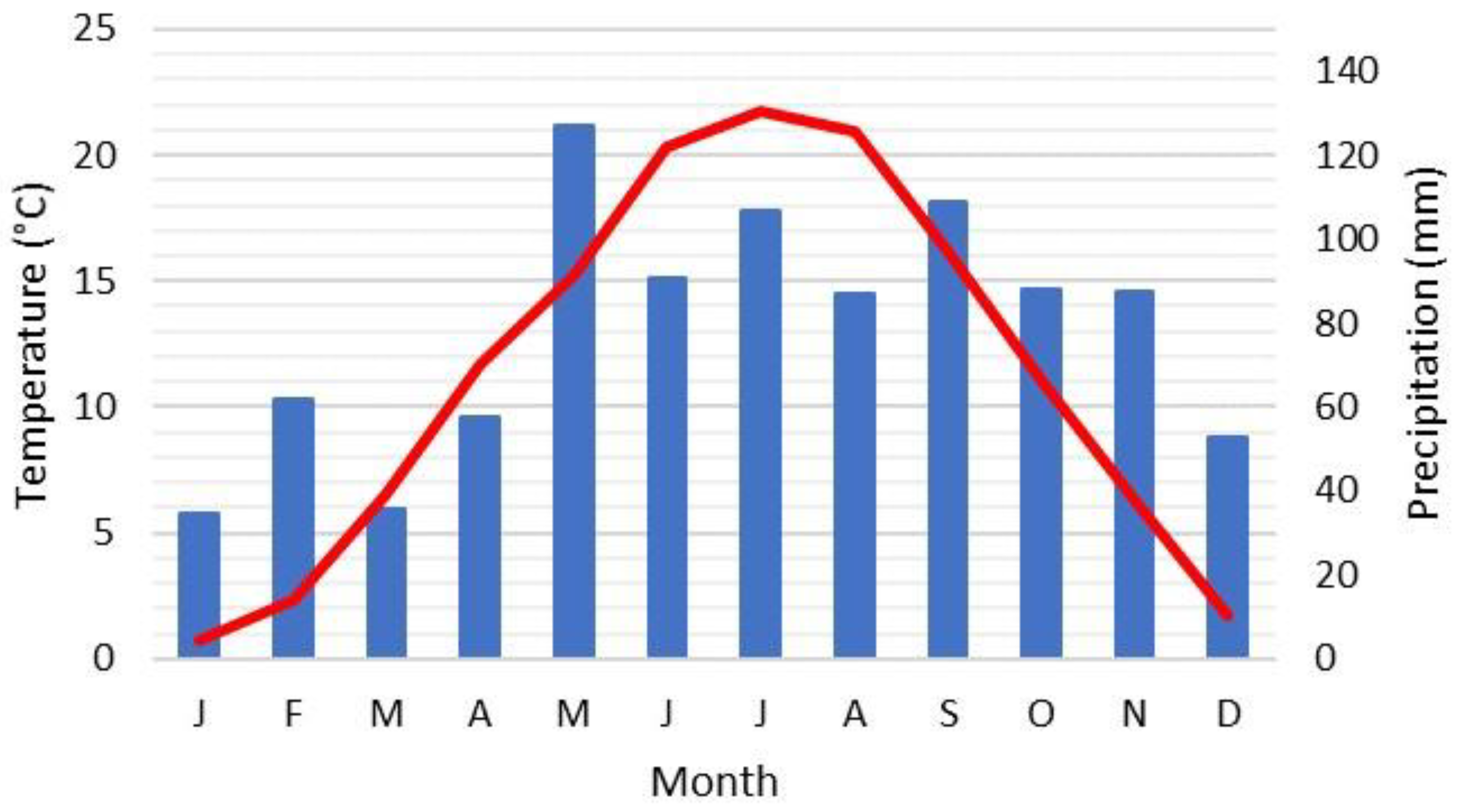

The study was conducted at two sites located approximately 3 km apart in the Podravska region of northeastern Slovenia, near the town of Ptuj. The loamy site (L site) is situated in Moškanjci (46°24’31.2’’N, 16°0’5.1’’E) at an elevation of 212 m, while the silty clay site (SC site) is located in Mezgovci (46°26’04.2’’N, 15°58’28.6’’E) at 215 m. Both sites share similar climatic conditions, belonging to the Alpine South (ALS6) climatic zone [

18]. During the experimental period (2011-2021), the average annual temperature was 11.2°C and the average annual precipitation was 938 mm [

19] (

Figure 1).

The soil at the L site developed on gravel and sand deposits of the Drava River and is classified by World Reference Base (WRB) as Dystric Cambisol (Loamic, Humic). It is shallow to moderately deep, with a clay content of 18-22%. In contrast, the SC site comprises deep alluvial soils of the Pesnica River valley with a silty clay texture (51–55% clay), classified by WRB as Gleyic Cambisol (Clayic, Humic) [

20].

At both sites, two contrasting tillage systems differing in soil disturbance intensity were initially applied: conventional moldboard ploughing (CT) to a depth of 25 cm followed by seedbed preparation (leaving no crop residues on the surface) and minimum tillage (MT), implemented as shallow “composting tillage” using a four-row Vario-Disc (EversAgro) to a depth of 10 cm, maintaining at least 30% soil cover by residues from the previous crop. These treatments were continuously applied from 2011 onward. In 2017, each field was split, and a no-till system (NT; direct seeding) was introduced. This resulted in four current treatments: conventional tillage (CT), minimum tillage (MT), no-till following long-term CT (NTct) and no-till following long-term MT (NTmt).

Typical 5-year crop rotation included soybean – winter wheat with hairy vetch as a cover crop after wheat harvest – maize – winter barley and soybean – maize. Prior to the start of the experiment, meliorative liming was conducted in 2011 using limestone (0–8 mm) with a Total Neutralizing Power of 97% relative to pure CaCO₃ [

21] and with a reactivity of 45.7% [

22]. Application rates were 12.5 t ha⁻¹ at the L site and 15 t ha⁻¹ at the SC site. Mineral fertilisation and plant protection were managed according to local farmer practice for each crop, and no organic fertilisers were applied.

2.2. Soil Sampling

Soil Sampling was conducted at both sites in mid-October in 2021, prior to maize harvest, at depths of 0–10 cm and 10–20 cm. Ploughing (CT) had been performed 10 months earlier (December 2020) and minimum tillage (MT) in early April 2021. Soil samples of each of the four tillage treatments were taken from randomly distributed sampling locations in each treatment, five samples at the L site and three at the SC site. We used a root auger (Eijkelkamp) yielding undisturbed soil cores of 700 cm³. Each core was carefully divided into two halves: one half was air-dried at 40 °C, ground, and sieved through a 2 mm mesh [

23] for physico-chemical analyses, while the other half was used for determining the Dry Aggregate Size Distribution (DASD). Dry sieving was chosen over wet sieving to allow subsequent chemical analyses on dry aggregates. Additional samples for bulk density determination were collected using a core sampler with Kopecky cylinders [

24].

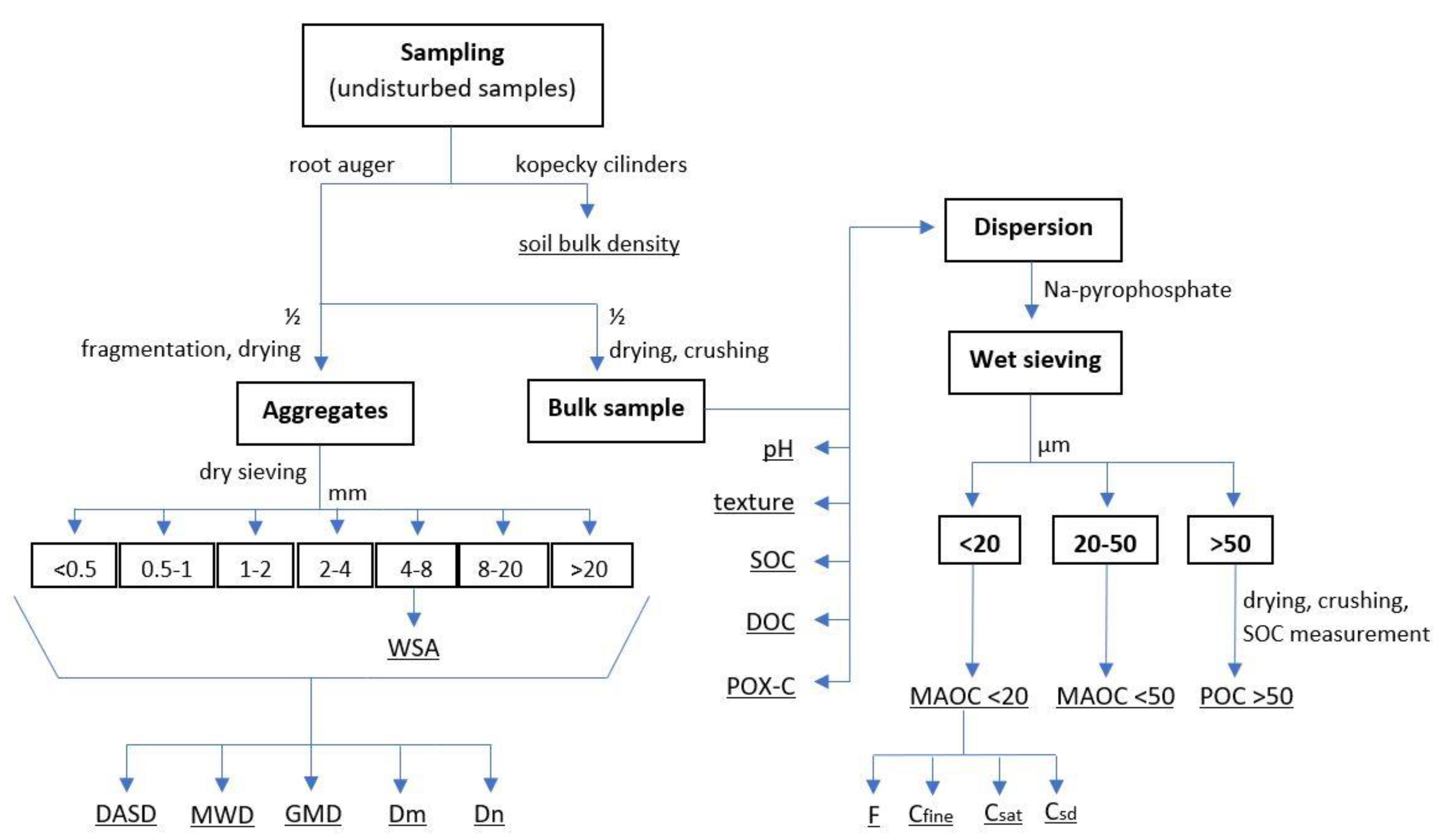

A schematic overview of sample preparation and subsequent analyses is presented in

Figure 2.

2.3. Detailed Methodology of Sample Preparation and Analyses

2.3.1. Physico-Chemical Analyses

Particle size distribution was determined using the sieving and pipette method [

25], while total organic carbon (SOC) was measured by dry combustion [

26]. Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) was extracted with 0.01 M CaCl₂ at a soil-to-solution ratio of 1:10 [

27], and permanganate-oxidizable organic carbon (POX-C) was quantified using sodium permanganate solution [

28]. Particulate organic carbon (POC; >50 µm) and mineral-associated organic carbon (MAOC; <50 µm and <20 µm) were separated from the bulk sample by wet sieving through 50- and 20-µm meshes [

25,

29,

30]. SOC in each fraction was determined by dry combustion [

26], and all organic C contents were converted to t ha⁻¹ considering sampling depth and soil bulk density.

Following SOC determination in the <20 µm fraction (i.e., % MAOC in the fine fraction), the proportion of organic carbon in the fine fraction of the bulk sample (F; <20 µm; equation 3) was calculated, and fine-fraction carbon saturation (Cₛₐₜ) was estimated using the Hassink’s equation [

31]:

where C

sat is the C saturation (t ha

-1), fine fraction (%) is the proportion of <20 µm particles (%) and BD is soil bulk density (t m

-3) in 0–10 cm layer.

The potential deficit for binding organic carbon in fine fraction (C

sd) was calculated using C

sat and measured organic C in soil fraction <20 µm by dry combustion (C

fine, t ha

-1):

Proportion of MAOC (F) of total organic carbon (SOC) was calculated as a ratio between measured MAOC (t ha

-1) and SOC (= MAOC + POC) (t ha

-1):

2.3.2. Aggregation, Structure Stability and Indices

To determine the dry aggregate size distribution (DASD), the remaining half of each undisturbed sample was processed by drying and sieving [

32]. The dried samples were sieved using a Retsch AS 200 Control sieve shaker, separating aggregates into six size classes (20, 8, 4, 2, 1, and 0.5 mm). Each size class was weighed, and the proportion of each class relative to the bulk sample (%) was calculated.

Aggregates in the 4–8 mm size class were capillary-moistened with deionized water on tissue paper for 10 minutes to prevent slaking [

33] and subsequently analysed for water-stable aggregates (WSA) using the wet sieving method with an Eijkelkamp apparatus [

34]. The 4–8 mm fraction was chosen because the stability of aggregates larger than 2 mm is strongly influenced by root and hyphal growth and is therefore sensitive to agricultural management practices [

35].

Water stable aggregates (WSA) were calculated [

34] with sand correction:

where wNaOH is the weight of soil obtained in the dispersing solution and weight of dry soil is the weight of sample weighed into sieve in grams. In equation, the material on sieve after wet sieving (sand in g) and dry weight of dispersing solution (0,15 g in 75 ml) are considered.

For investigating impacts of different tillage intensities on DASD, we calculated mean weight diameter (MWD), geometric mean diameter (GMD), mass fractal dimension (Dm), and Rosin-Rammler regression index (Dn).

Mean weight diameter (MWD) was calculated as [

36]:

where n is the total number of size classes, w

i is the proportion of the total aggregates in the ith size class, and x̄

i is the mean diameter of the ith size class sieve.

Geometric mean diameter (GMD) was calculated as [

37]:

where n is the total number of size classes, w

i is the total weight of the aggregates in the ith size class, and x̄

i is the mean diameter of the aggregates in the ith size class.

The mass fractal dimension (Dm) quantifies the structure and stability of soil aggregates by describing how aggregate mass scales with size. A Dm value of 3 indicates a fully space-filled soil with minimal porosity, whereas Dm < 3 reflects a more porous structure. Lower Dm values correspond to aggregates that are more porous, with mass increasing more slowly as size increases. The mass fractal dimension was calculated following Tyler and Wheatcraft equation [

38]:

where r is the grain size, M(r < R

i) is the cumulative mass of aggregates of < R

i, M

tot is the total mass of soil, R

i is the aggregate size class, and R

max is the maximum aggregate size.

The Rosin–Rammler index (Dn) characterizes soil fragmentation based on the slope of the exponential decay curve of aggregate size distribution. Values of Dn between 1 and 3 indicate a relatively uniform distribution of aggregate sizes, whereas Dn ≤ 1 reflects a more exponential distribution with a wider range of sizes. It was originally developed to describe the particle size distribution of powders and fragmented solids, Dn was calculated following Rosin and Rammler equation [

39]:

where F(x) is cumulative undersize distribution function, x is particle size, c is the particle size corresponding to 63.2 % cumulative distribution undersize, n is a characteristic constant of the material under analysis and gives a measure of steepness (slope) of cumulative curve.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.1) [

40] to evaluate the effects of location, tillage treatment, and soil depth on the measured soil parameters. Homogeneity of variances was assessed using Levene’s test (car package).

For data meeting the assumptions of normality, linear mixed-effects models (LMM) were fitted using the lmer function from the lme4 package. The models included location, treatment, and depth as fixed effects, with Block nested within location as a random effect. Significance of fixed effects was evaluated using Type III ANOVA with the Satterthwaite approximation (lmerTest package). Residuals were checked for normality and homoscedasticity through visual inspection (residual and Q–Q plots) and the Shapiro–Wilk test. When necessary, data were transformed (logarithmic, square-root, or inverse) to meet model assumptions.

If normality could not be achieved after transformation, data were analyzed using a nonparametric aligned rank transform (ART) ANOVA (ARTool package), which allows factorial analysis of nonparametric data. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using estimated marginal means (EMMs) via the emmeans package, with Sidak-adjusted contrasts to test for significant differences among factor levels or interactions.

For within-site analyses, the same approach was applied without the location factor, considering only treatment and depth as fixed effects and block as a random effect. When the treatment × depth interaction was not significant, main effects were interpreted independently. Relationships between structural indices and physical soil parameters were assessed using Spearman correlation analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Properties

Basic soil properties for both sites and depths are presented in

Table 1. The sites differed fundamentally in texture: the L site contained 18-22% clay while the SC site contained 47-55% clay. Correspondingly, the SC site had lower bulk density (1.06-1.20 vs. 1.20-1.43 t m⁻³) and higher SOC (2.4-3.1% vs. 1.4-2.0%) than the L site. These contrasting properties provided an ideal comparison for evaluating texture-dependent tillage responses.

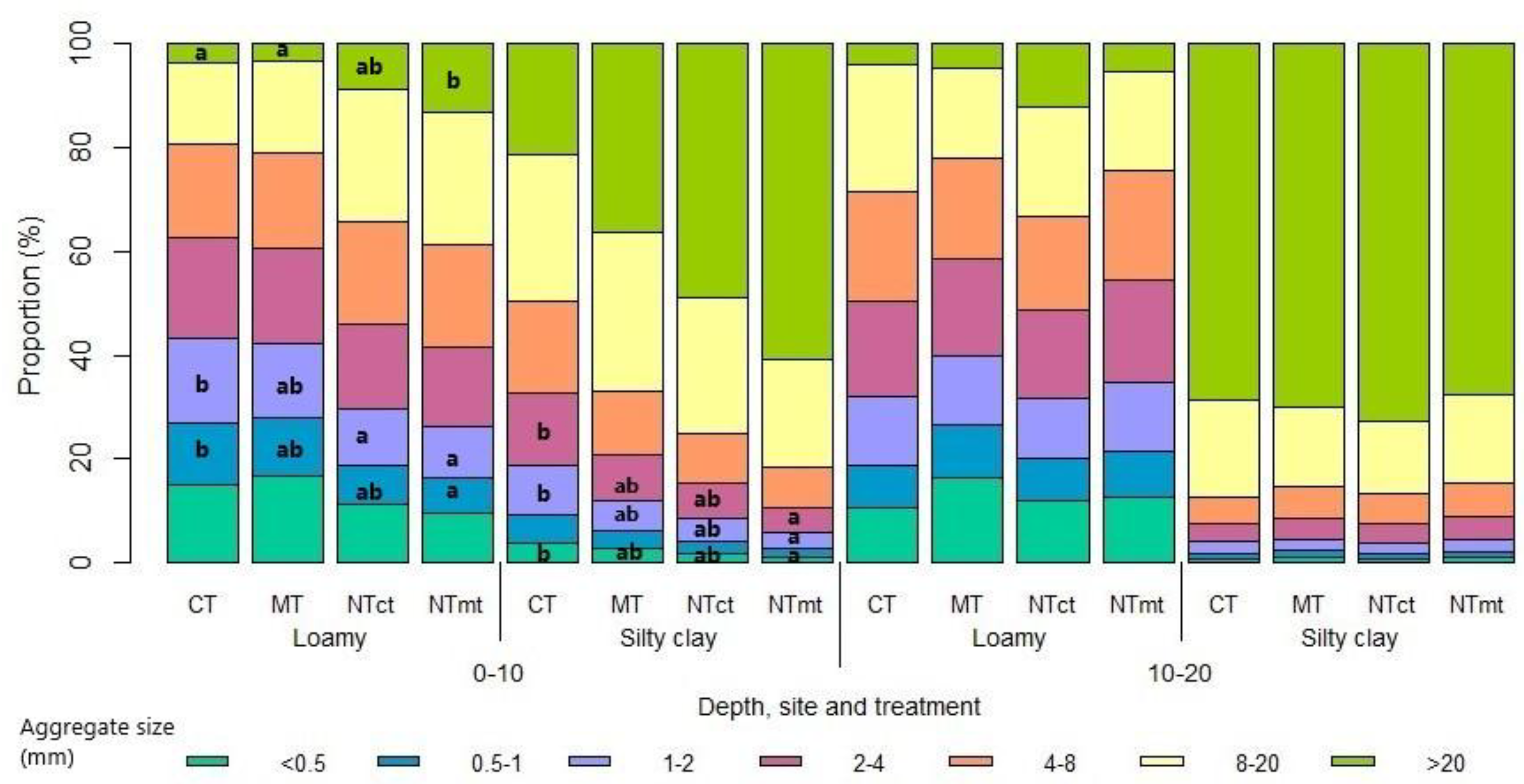

3.2. Dry Aggregate Size Distribution and Aggregate Stability

In the upper 10 cm, tillage intensity influenced aggregate size distribution at both sites (

Figure 3). At the L site, NTmt showed significantly more aggregates >20 mm and fewer smaller aggregates (0.5-1 and 1-2 mm) than CT. At the SC site, significant differences occurred only in smaller aggregates (<0.5, 1-2, and 2-4 mm), with NTmt showing lower proportions than CT. No treatment differences occurred at 10-20 cm.

At the SC site, differences in the topsoil were reflected only in the mean weight diameter (MWD), which was 42% lower under CT compared with NTmt. The mass fractal dimension (Dm) showed a significant difference only between depths in the CT treatment, with Dm being 21% higher in the upper 10 cm compared with 10–20 cm (

Table 2).

Among all structural indices, MWD, GMD, and Dm were the most sensitive to tillage intensity at both sites, which differed in texture and SOC content. MWD and GMD were significantly lower at the L site compared with the SC site, whereas Dm was significantly higher at the L site than at the SC site (

Table 2).

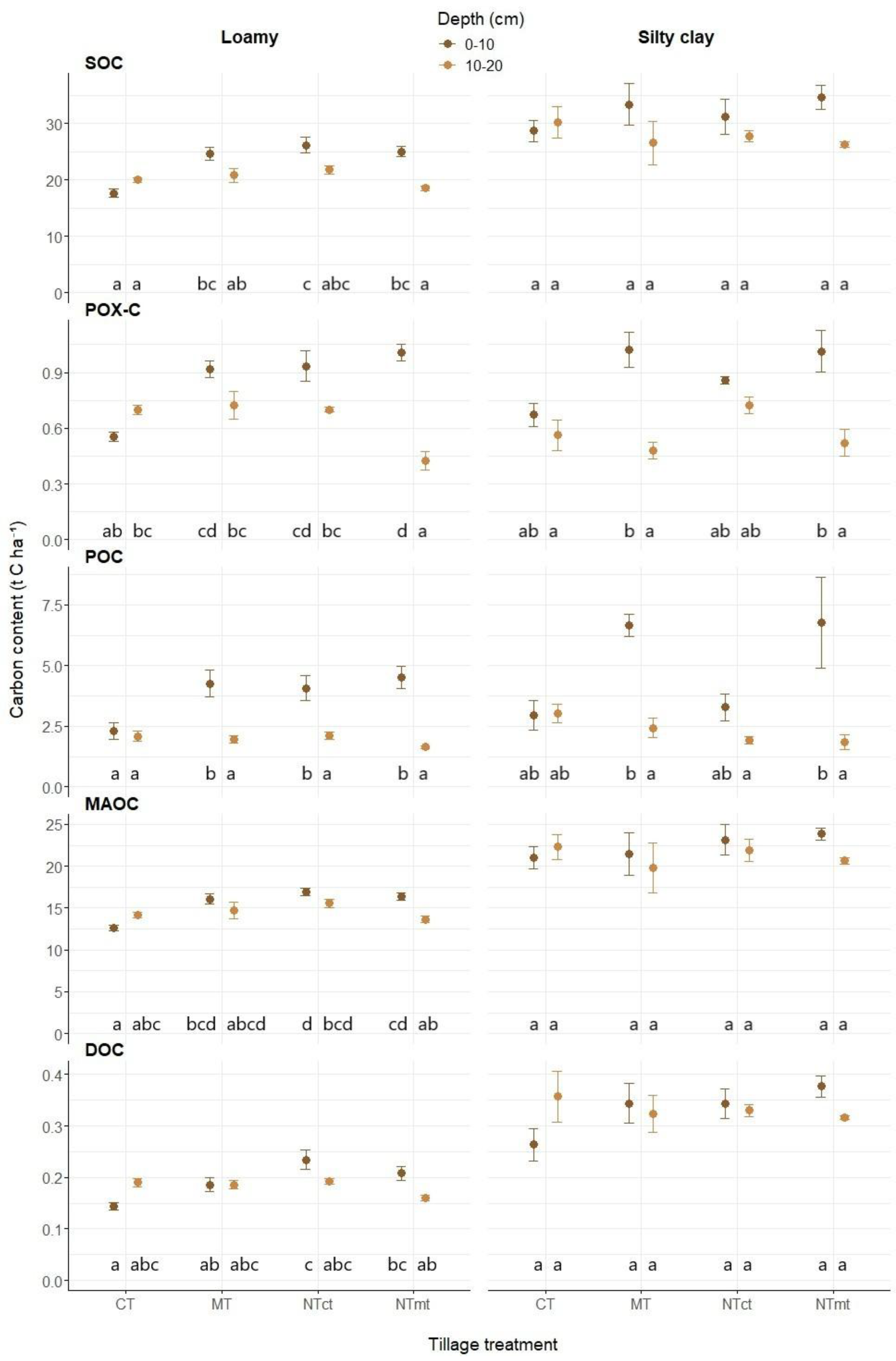

3.3. Soil Organic Carbon Fractions Distribution

Tillage intensity effects on C fractions showed clear texture-dependent patterns. In loamy soil, all C fractions responded significantly to tillage in the upper 10 cm, with conservation tillage increasing C stocks through both labile and stable pools. In silty clay soil, inherent protection from high clay content moderated tillage effects, though vertical stratification patterns remained detectable.

Organic carbon (C) fraction contents were generally higher at the SC site than at the L site, but the effects of tillage intensity were more pronounced at the L site, particularly in the top 10 cm (

Figure 4). At the L site, SOC exhibited significant stratification, with higher SOC under lower-intensity tillage (NTmt). SOC in CT was 28%, 32%, and 30% lower than in MT, NTct, and NTmt, respectively, in the top 10 cm, while no significant differences were observed at the SC site.

At the L site, MAOC also showed stratification under NTmt. In the top 10 cm, MAOC in CT was 22%, 25%, and 23% lower than in MT, NTct, and NTmt, respectively; no differences were detected at 10–20 cm. No significant differences in MAOC were observed at the SC site (

Figure 4).

POC contents were significantly stratified by depth at both sites, except in CT at L and in CT and NTct at SC. Tillage effects on POC were evident in the top 10 cm at L, where CT contained 46%, 43%, and 49% less POC than MT, NTct, and NTmt, respectively (

Figure 4).

POX-C exhibited significant stratification at L under NTmt and at SC under MT and NTmt, with higher contents in the upper layers. Tillage significantly influenced POX-C; at L, CT had 40%, 41%, and 46% lower POX-C than MT, NTct, and NTmt, respectively. At 10–20 cm, POX-C was lower in NTmt compared with other treatments (

Figure 4).

DOC at L was significantly lower under CT in the top 10 cm compared with NTct (−26%) and NTmt (−13%), whereas no significant differences were observed at SC (

Figure 4).

3.4. Carbon Saturation on Fine Soil Fraction (<20 µm)

The saturation of the fine fraction (<20 µm) (Cₛₐₜ) and the potential of the fine fraction to sequester carbon (C

sd, i.e., SOC deficit) were calculated for the top 10 cm (

Table 3). Both sites exhibited positive C

sd, with greater potential at the SC site, although no significant differences were observed among tillage treatments. At the L site, C

sd under CT was 60% higher than under MT, indicating a larger deficit of MAOC.

Tillage influenced the proportion of MAOC relative to total SOC, expressed as MAOC/(MAOC + POC) (F), only at the SC site, where F was 20% lower under MT compared with CT (

Table 3). The MAOC content in the fine fraction (% MAOC <20 µm) was generally similar across sites. At the L site, however, CT in the 0–10 cm layer had 25% and 21% lower MAOC than MT and NTct, respectively, with the lowest value (1.73%) observed under CT, indicating higher mineralization in ploughed, lighter soils. In all other cases, fine-fraction MAOC ranged from 2.08 to 2.45%, regardless of soil texture (

Table 3).

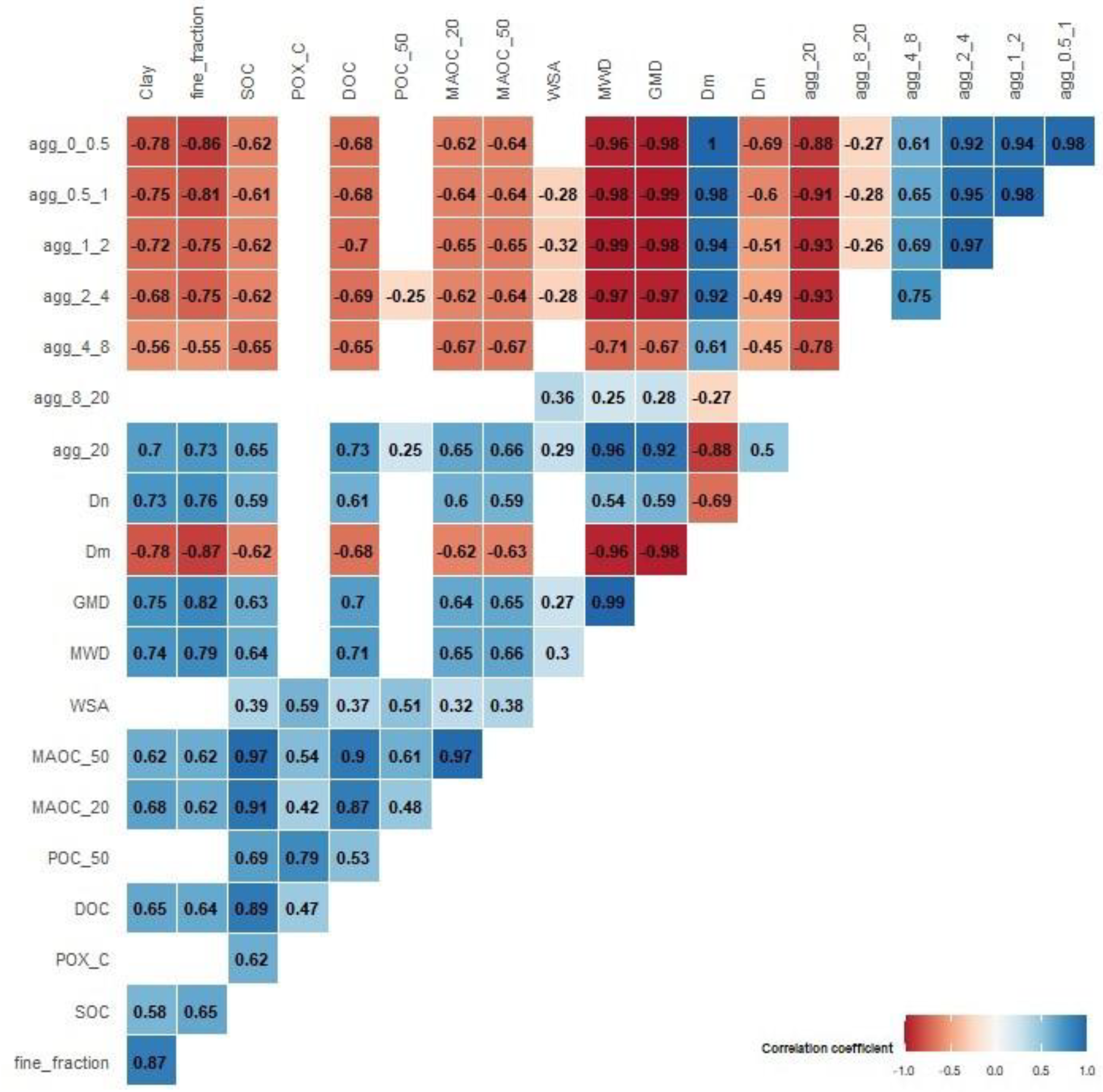

3.5. Correlation Between Aggregate Distribution, Structural Stability Indices and Organic Carbon Fractions

Spearman correlation analysis (p < 0.05) between organic C fractions, aggregate size classes, and structural stability indices is presented in

Figure 5. Smaller aggregates (0–0.5, 0.5–1, 1–2, 2–4, and 4–8 mm) were negatively correlated with clay, fine fraction, and organic C fractions (SOC, DOC, MAOC <20 µm, and MAOC <50 µm), whereas 8–20 mm aggregates showed no significant correlations. The largest aggregates (>20 mm) were positively correlated with clay, fine fraction, and SOC, POC, MAOC <20 µm, and MAOC <50 µm.

Structural stability indices were strongly associated with organic C fractions. Dm was negatively correlated with DOC, MAOC <20 µm, and MAOC <50 µm (rS = −0.68, −0.62, −0.63), while GMD and MWD showed strong positive correlations with the same fractions (GMD: rS = 0.69, 0.64, 0.65; MWD: rS = 0.71, 0.65, 0.66). The Dn index also correlated positively with DOC, MAOC <20 µm, and MAOC <50 µm (rS = 0.61, 0.60, 0.59).

Water-stable aggregates (WSA) correlated moderately with POX-C and POC (r

S = 0.59 and 0.51) and weakly with DOC, MAOC <20 µm, and MAOC <50 µm (r

S = 0.37, 0.32, 0.38). Strong positive correlations were observed among organic C fractions, notably DOC with MAOC <20 µm and MAOC <50 µm (r

S = 0.87, 0.90), and between POX-C and POC (r

S = 0.80) (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

4.1. Dual Time-Scale Responses to Tillage Reduction

Our experimental design uniquely separates transitional (5-year NT) from long-term (11-year MT) tillage effects, revealing differential response rates among C pools and aggregate properties. The rapid response of labile fractions (POX-C, POC) to 5-year NT conversion indicates that some soil health improvements emerge relatively quickly after reducing disturbance. In contrast, MAOC accumulation appeared more gradual, with 11-year MT showing clearer differentiation from CT than 5-year NT transitions. This temporal pattern aligns with the hierarchical aggregate formation model [

5], where microaggregate-protected C accumulates more slowly than free particulate matter. However, the 5-year NT period was sufficient to shift aggregate size distribution toward larger classes, suggesting that physical structure recovery may proceed faster than complete C saturation of newly formed aggregates. Importantly, the NTmt treatment (5 years NT after 11 years MT) consistently showed equal or superior performance to long-term MT alone, suggesting that eliminating even shallow tillage provides additional benefits. This supports a progressive model of soil health improvement where each reduction in disturbance intensity yields measurable gains.

4.2. Organic C Fractions

In light soils, after 11 years of MT and 5 years of NT, SOC in the top 10 cm was significantly higher under MT, NTct, and NTmt compared with CT, consistent with previous studies showing lower SOC under intensive tillage, particularly in the upper soil layers [

41,

42,

43]. MAOC followed a similar pattern, with higher concentrations under reduced tillage. This increase likely reflects enhanced organo-mineral associations and the formation of micro- and macroaggregates that provide physical protection for organic matter [

5]. Under CT, MAOC was uniform with depth, presumably due to plough-induced homogenization, whereas reduced tillage resulted in lower MAOC at 10–20 cm than at 0–10 cm, indicating enrichment of MAOC and POC in the upper soil layer from surface residues, root exudates, and microbial inputs [

44]. Reduced tillage may also slow decomposition by maintaining a higher proportion of macroaggregates [

45].

In heavier soils (SC), SOC was higher than in L soils regardless of tillage, reflecting stronger physical protection from degradation. This is supported by larger aggregates (

Figure 3), higher MWD and GMD, lower Dm (

Table 2), and strong correlations between SOC and structural indices (

Figure 5). Lower clay soils are better aerated, accelerating organic matter decomposition [

46]. In the top 10 cm, MAOC comprised 61–76% of total SOC, highlighting its dominant role in SOC stabilization. Reduced tillage decreased the MAOC relative proportion in the topsoil, retaining more POC, while the opposite trend was observed at 10–20 cm (

Figure 4), and MAOC as a percentage of SOC generally increased with depth [

47].

DOC was higher under reduced tillage, likely due to increased surface residues and microbial activity [

48], and correlated strongly with MAOC <20 µm and <50 µm (r

S = 0.87 and 0.90), suggesting DOC is closely associated with mineral-bound C [

49]. POX-C, a labile and partially stabilized SOC fraction [

50,

51], was higher in the upper layers under reduced tillage, whereas CT showed lower POX-C due to enhanced decomposition. Labile fractions are better protected within aggregates under reduced tillage, allowing SOC accumulation [

52]. The strong correlation between POX-C and POC (r

S = 0.80;

Figure 5) confirms that POX-C responds to soil management and can track SOC dynamics across soils of contrasting texture [

10,

53].

4.3. SOC Saturation in Fine Fraction (<20 µm)

The proportion of MAOC/(MAOC+POC) (F) in the 0–10 cm layer was highest under CT at both sites, likely due to lower surface plant residues (less POC) caused by ploughing and soil mixing. SOC stocks followed the order CT (28.7) < NTct (31.2) < MT (33.4) < NTmt (34.7 t C ha⁻¹), reflecting the accumulation of POC under less intensive tillage (

Figure 4).

The potential for binding organic C to the fine fraction (C

sd) in the top 10 cm has not been reached at either site. Conservation tillage effects on C sequestration were detectable only at the loamy site (L), where C

sd was significantly higher under CT than MT and NT treatments. This is likely because surface residues in reduced tillage (MT, NT) must first decompose before forming MAOC [

54], whereas mechanical mixing in CT enhances degradation. Less intensive tillage promotes aggregate preservation and formation, stabilizing SOC and increasing SOC stocks [

5].

At the heavier SC site, differences in Csd among tillage treatments were not significant, as decomposition is slower even under CT, and aggregates are larger and more stable, with higher MWD and GMD compared to site L.

The proportion of MAOC in the fine fraction (%) was similar at both sites, ranging 2.1–2.5%, except at L in CT (1.7%), where C

sd was higher. This narrow range suggests the fine fraction may approach its effective MAOC capacity; however, this should be interpreted cautiously. Apparent plateaus in MAOC may reflect input-dependent equilibrium rather than true mineral C saturation, as mineral surfaces may not be fully occupied but balanced with current organic matter inputs [

55]. Observed patterns could also result from kinetic limitations in organo-mineral associations [

56] or transient conditions influenced by residue quantity and quality, altering partitioning between particulate and mineral-associated C [

57,

58]. While fine-fraction MAOC similarity suggests strong mineral control, further evidence, such as mineral surface area or mineralogical analyses, is needed to confirm true C saturation [

59].

The contrasting responses between sites highlight a fundamental trade-off in detectability versus baseline protection. Loamy soils showed clearer tillage effects because lower clay content provides less inherent SOC stabilization, making management-induced changes more apparent. Conversely, silty clay soils exhibited smaller relative changes because high clay content already provides substantial protection even under CT. This has important implications for monitoring programs: lighter soils may be better sentinels for detecting early management effects, while heavier soils may require longer observation periods or more sensitive indicators (e.g., labile fractions, aggregate-scale analyses) to detect improvements.

4.4. Aggregation and Structural Indices

The effects of tillage intensity were evident in the distribution of structural aggregates determined by dry sieving (DASD). In the upper 10 cm, no-till systems (NTct, NTmt) contained more large aggregates and fewer small aggregates than CT, indicating that reduced tillage preserves existing aggregates, promotes the formation of new aggregates, and enhances structural stability. Tillage type is thus a key factor in macroaggregate formation [

60,

61].

For smaller aggregates, where stabilization is primarily mediated by polysaccharide-clay interactions, tillage effects were also observed in the top layer at both sites. Intensive tillage increased the proportion of smaller aggregates (<0.5, 0.5–1, 1–2, 2–4 mm) due to crushing and faster turnover of macroaggregates, resulting in fewer macroaggregates and fewer newly formed microaggregates in CT [

45].

Indicators MWD and GMD were higher in heavier soils, with MWD significantly greater in NTmt than in CT at the SC site, reflecting improved aggregation, stability, and larger aggregate size. Clay content explains >50% of aggregate distribution variability, particularly for larger aggregates [

15], which is consistent with our results: correlations with clay ranged from negative for the smallest (<0.5 mm, r

S = -0.78) to positive for the largest (>20 mm, r

S = 0.70) aggregates.

MWD and GMD were strongly positively correlated with DOC and MAOC (<20 µm and <50 µm) (p<0.05;

Figure 5), indicating that organic matter contributes to aggregate size and stability. While clay enhances aggregate stability in heavier soils, CT reduces this effect (

Table 2).

The Dm index differed between sites. Contrary to expectations for clayey soils, Dm was lower at the SC site due to the predominance of larger aggregates and associated larger pores, reflecting lower bulk density and higher SOC. Dm decreased with depth at SC, indicating increased aggregation and stability, whereas the highest Dm occurred in CT (0–10 cm), consistent with lower aggregate stability and the lowest WSA values, indicating greater susceptibility to dispersion.

4.5. Rethinking Carbon Saturation in Agricultural Soils

The remarkably consistent MAOC concentrations in fine fractions (2.0-2.5%) across treatments and textures—except CT in loamy soil (1.73%)—raise important questions about C saturation dynamics. Traditional saturation models [

31,

55] suggest mineral surfaces have finite capacity, but our results indicate that apparent plateaus may reflect input-output equilibria rather than true saturation [

56,

57]. Three mechanisms could explain these patterns: (i) Current organic matter inputs maintain steady-state MAOC levels that are below true mineral capacity; (ii) kinetic limitations slow MAOC formation such that systems remain in transient states for decades; or (iii) decomposition rates at steady state balance new MAOC formation, creating apparent saturation. The deviation in CT loamy soil is particularly informative. Lower MAOC combined with higher C

sd suggests that tillage-accelerated decomposition depleted mineral-associated C below the system's equilibrium level. This demonstrates that management can push soils below their "practical" C saturation threshold, even if absolute mineral capacity remains higher. To distinguish among these scenarios, future research should combine mineralogical analyses (specific surface area, mineral composition) with isotopic approaches to quantify MAOC turnover rates. Understanding whether observed MAOC levels reflect approaching saturation or steady-state equilibrium is critical for predicting long-term C sequestration potential under different management scenarios.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that reducing tillage intensity consistently preserves and rebuilds soil organic matter and structure across contrasting soil textures, but the magnitude, rate, and detectability of responses are texture-dependent. Key findings from our dual time-scale experiment:

1. “Temporal dynamics”: Labile C pools (POX-C, POC) and aggregate recovery respond within 5 years of NT conversion, demonstrating that some soil health improvements emerge relatively quickly. However, complete MAOC recovery likely requires longer time scales, particularly in lighter soils where baseline protection is lower.

2. “Texture-dependent responses”: Loamy soils showed pronounced tillage effects across all C fractions due to lower baseline protection, while silty clay soils exhibited more subdued responses because high clay content buffers against management-induced changes. This highlights a fundamental trade-off between detectability and resilience.

3. “Fine-fraction C consistency”: The remarkably uniform MAOC concentrations (2.0-2.5%) across treatments and textures—except depleted levels under CT in loamy soil—suggest that agricultural soils may operate near input-dependent equilibria rather than absolute mineral saturation. This challenges simple interpretations of C saturation and underscores the need for integrated mineralogical and kinetic studies.

4. “Physical protection mechanism”: Strong correlations between aggregate stability indices (MWD, GMD, Dm) and C fractions confirm that soil structural improvements directly support C stabilization. Conventional tillage systematically disrupted this protection, increasing small aggregate proportions and accelerating C losses.

5. “Progressive improvement”: The superior performance of NTmt (NT after MT) compared to MT alone indicates that each incremental reduction in soil disturbance yields additional benefits, supporting a progressive rather than threshold model of soil health recovery.

From an applied perspective, these findings affirm that conservation tillage is an effective strategy for rebuilding soil health across diverse textures. However, practitioners and policymakers should recognize that: (i) lighter soils will show faster, more pronounced responses, making them ideal for demonstrating early benefits; (ii) heavier soils require longer observation periods or sensitive indicators (labile fractions, aggregate analyses) to detect improvements; and (iii) even small reductions in tillage intensity (e.g., MT to NT) provide measurable advantages.

Future research should prioritize: (i) extending observations beyond 15 years to capture full MAOC equilibration in lighter soils; (ii) integrating mineralogical analyses to distinguish true saturation from kinetic limitations; (iii) quantifying the economic and environmental trade-offs of different tillage intensities across texture classes; and (iv) exploring whether aggregate-protected C fractions can serve as early warning indicators for soil degradation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M.; methodology, R.M. and S.M.; validation, S.M., H.G. and R.M.; formal analysis, S.M.; investigation, S.M., H.G. and R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M. and R.M.; writing—review and editing, S.M. and R.M.; visualization, S.M.; supervision, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS) through a PhD studentship (PhD grant to Sara Mavsar). The APC was funded by ARIS Program Agroecosystems (P4-0085).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge farms Majerič and Korošec for enabling experimentation on their fields, helping conduct experiments and providing practical advice. Companies IGM Zagorje, Agromag and MRebernik who helped by providing limestone, seeds and advice about use of machinery and pharmaceuticals. We would also like to acknowledge the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS) and the Biotechnical Faculty, Uiversity of Ljubljana.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Cfine

|

soil organic carbon in fine fraction (<20 µm) (= MAOC <20 µm) |

| Csat

|

soil organic carbon saturation of the fine fraction (<20 µm) |

| Csd

|

potential deficit for binding organic carbon in fine fraction (<20 µm) |

| CT |

conventional ploughing |

| Dm |

mass fractal dimension |

| Dn |

Rosin-Rammler index |

| DOC |

dissolved organic carbon |

| F |

proportion of mineral-associated organic carbon (<50 µm) (MAOC <50 µm) |

| Fine fraction |

soil mineral fraction of clay and fine silt (<20 µm) |

| GMD (mm) |

geometric mean diameter (mm) |

| L site |

loamy texture site |

| MAOC in fine fraction 20 µm (%) |

percentage of mineral-associated organic carbon per unit of fine fraction (<20 µm) |

| MAOC <20 µm |

mineral associated organic carbon in clay and fine silt (<20 µm) |

| MAOC <50 µm |

mineral-associated organic carbon in clay and silt (<50 µm) |

| MT |

non-inversion shallow tillage |

| MWD (mm) |

mean weight diameter (mm) |

| NT |

no tillage |

| NTct |

no tillage following conventional ploughing |

| NTmt |

no tillage following non-inversion shallow tillage |

| POC |

particulate organic carbon |

| POX-C |

permanganate oxidizable carbon |

| rS

|

coefficient of correlation by Spearman |

| SC site |

silty clay texture site |

| SOC |

soil organic carbon |

| WRB |

World Reference Base |

| WSA (%) |

water stable aggregates (%) |

References

- Bronick, C. J.; Lal, R. Soil structure and management: A review. Geoderma 2005, 124(1–2), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Liang, G.; Zheng, F.; Zhang, M.; Li, S. A global meta-analysis of the impacts of no-tillage on soil aggregation and aggregate-associated organic carbon. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32(18), 5292–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topa, D.; Cara, I. G.; Jităreanu, G. Long term impact of different tillage systems on carbon pools and stocks, soil bulk density, aggregation and nutrients: A field meta-analysis. Catena 2021, 199(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlinger, A.; Garland, G.; Banerjee, S.; Degrune, F.; García-Palacios, P.; Herzog, C.; Pescador, D. S.; Romdhane, S.; Ryo, M.; Saghaï, A.; Hallin, S.; Maestre, F. T.; Philippot, L.; Rillig, M. C.; van der Heijden, M. G. A. The impact of agricultural management on soil aggregation and carbon storage is regulated by climatic thresholds across a 3000 km European gradient. Glob. Change Biol. 2023 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Elliott, E. T.; Paustian, K. Soil macroaggregate turnover and microaggregate formation: A mechanism for C sequestration under no-tillage agriculture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32(14), 2099–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, R.C.; Madari, B.E.; Maddock, J.E.L.; Machado, P.L.O.A.; Torres, E.; Franchini, J.; Costa, A.R. The impact of soil management on aggregation, carbon stabilization and carbon loss as CO2 in the surface layer of a Rhodic Ferralsol in Southern Brazil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2009, 132, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian, K.; Six, J.; Elliott, E.T.; Hunt, H.W. Management options for reducing CO2 emissions from agricultural soils. Biogeochemistry 2000, 48, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Elliott, E. T.; Paustian, K.; Doran, J. W. Aggregation and Soil Organic Matter Accumulation in Cultivated and Native Grassland Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1998, 62(5), 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Lal, R.; Owens, L.; Izaurralde, R. C. Distribution of light and heavy fractions of soil organic carbon as related to land use and tillage practice. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 92(1–2), 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wang, L.; Yang, Q.; Xiu, W.; Li, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, G. Dynamics of soil organic carbon and labile carbon fractions in soil aggregates affected by different tillage managements. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13(3), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, B.; Lu, Y. Micromorphological analysis of soil structure under no tillage management in the black soil zone of Northeast China. J. Mt. Sci. 2009, 6(2), 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Zhu, A. N.; Zhang, J. B.; Yang, W. L.; Xin, X. L.; Zhang, X. F. Changes in soil organic carbon and aggregate stability after conversion to conservation tillage for seven years in the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain of China. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14(6), 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Cui, S.; Jagadamma, S.; Zhang, Q. Residue retention and minimum tillage improve physical environment of the soil in croplands: A global meta-analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 194(June), 104292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagar, A. A.; Adamowski, J.; Memon, M. S.; Do, M. C.; Mashori, A. S.; Soomro, A. S.; Bhayo, W. A. Soil fragmentation and aggregate stability as affected by conventional tillage implements and relations with fractal dimensions. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 2020(197), 104494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfect, E.; Kay, B.D.; Ferguson, J.A.; Da Silva, A.P.; Denholm, K.A. Comparison of functions for characterizing the dry aggregate size distribution of tilled soil. Soil Tillage Res. 1993, 28(2), 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenu, C.; Le Bissonnais, Y.; Arrouays, D. Organic Matter Influence on Clay Wettability and Soil Aggregate Stability. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2000, 64(4), 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kölbl, A.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Content and composition of free and occluded particulate organic matter in a differently textured arable Cambisol as revealed by solid-state 13C NMR spectroscopy. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2004, 167(1), 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, M. J. The Environmental Stratification of Europe; University of Edinburgh, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arso meteo portal. Available online: www.meteo.arso.gov.si (accessed on 24th November 2025).

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Vienna, Austria, 2022; p. 236 p. Available online: https://www.isric.org/explore/wrb.

-

EN 12945+A1; Liming materials - Determination of neutralizing value - Titrimetric methods. 2016.

-

EN 13971; Carbonate and silicate liming materials - Determination of reactivity - Potentiometric titration method with hydrochloric acid. 2020.

-

ISO 11464:2006; Soil quality - Pretreatment of samples for physico-chemical analysis.

-

ISO 11272:2017; Soil quality - Determination of dry bulk density.

-

ISO 11277:2020; Soil quality - Determination of particle size distribution in mineral soil material - Method by sieving and sedimentation.

-

ISO 10694:1995; Soil quality - Determination of organic and total carbon after dry combustion (elementary analysis).

-

ISO 14255:1999; Soil quality - Determination of nitrate nitrogen, ammonium nitrogen and total soluble nitrogen in air-dry soils using calcium chloride solution as extractant.

- Weil, R. R.; Islam, K. R.; Stine, M. A.; Gruver, J. B.; Samson-Liebig, S. E. Estimating active carbon for soil quality assessment: A simplified method for laboratory and field use. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 2003, 18(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadamma, S.; Mayes, M. A.; Zinn, Y. L.; Gísladóttir, G.; Russell, A. E. Sorption of organic carbon compounds to the fine fraction of surface and subsurface soils. Geoderma 2014, 213, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tivet, F.; De Moraes Sá, J. C.; Lal, R.; Borszowskei, P. R.; Briedis, C.; dos Santos, J. B.; Sá, M. F. M.; da Cruz Hartman, D.; Eurich, G.; Farias, A.; Bouzinac, S.; Séguy, L. Soil organic carbon fraction losses upon continuous plow-based tillage and its restoration by diverse biomass-C inputs under no-till in sub-tropical and tropical regions of Brazil. Geoderma 2013, 2013(209–210), 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, J. A Model of the Physical Protection of Organic Matter in Soils The capacity of soils to preserve organic C and N by their association with clay and silt particles. Plant Soil 1997, 191, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Zorita, M.; Grove, J. H.; Perfect, E. Sieving duration and sieve loading impacts on dry soil fragment size distributions. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 94(1), 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, N.; Amin, S. Soil Organic Matter Fractionation and Its Effect on Aggregate Stability; Khulna University: Khulna, Bangladesh, 2007; p. 72 p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, W. D.; Rosenau, R. C. Aggregate stability and size distribution. Methods of Soil Analysis; Part 1 - Physical and Mineralogical Methods. Am. Soc. Agronomy 1986, 9(9), 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdall, J. M.; Oades, J. M. Organic matter and water-stable aggregates in soils. J. Soil Sci. 1982, 33, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bavel, C. H. M. Mean weight-diameter of soil aggregation as a statistical index of aggregation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1949, 14, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurak, A. P. Effect of gaseous phase on water-stable synthetic aggregates. Soil Sci. 1950, 69, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, S. W.; Wheatcraft, S. W. Fractal scaling of soil-particle size distributions: analysis and limitations. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1992, 56, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosin, P.; Rammler, E. The Laws Governing the Fineness of powdered coal. J. Inst. Fuel 1933, 7, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/.

- Hernanz, J. L.; López, R.; Navarrete, L.; Sánchez-Girón, V. Long-term effects of tillage systems and rotations on soil structural stability and organic carbon stratification in semiarid central Spain. Soil Tillage Res. 2002, 66(2), 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N. R.; Hedlund, K.; Jackson, L. E.; Kätterer, T.; Lugato, E.; Thomsen, I. K.; Jørgensen, H. B.; Isberg, P. E. How does tillage intensity affect soil organic carbon? A systematic review. Environ. Evid. 2017, 6(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Chakraborty, D.; Bandyopadhyay, K.; Aggarwal, P.; Rana, D. S. A global analysis of the impact of zero-tillage on soil physical condition, organic carbon content, and plant root response. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31(5), 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Yang, X.; Dou, Y.; Wang, B.; Xue, Z.; Sun, H.; Yang, Y.; An, S. Divergent contribution of particulate and mineral-associated organic matter to soil carbon in grassland. J. Environ. Manage. 2023, 344(June), 118536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Six, J.; Elliott, E. T.; Paustian, K. Aggregate and Soil Organic Matter Dynamics under Conventional and No-Tillage Systems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63(5), 1350–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sissoko, A.; Kpomblekou-a, K. Carbon decomposition in broiler litter-amended soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42(4), 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, X.; Yan, J.; Du, Z.; Lv, Y.; Zhou, H. Divergent Stabilization Characteristics of Soil Organic Carbon between Topsoil and Subsoil Under Different Land Use Types. Catena 2024, 2025(252), 108838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, R.; Ren, T.; Lei, M.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Cong, R. Tillage and straw-returning practices effect on soil dissolved organic matter, aggregate fraction and bacteria community under rice-rapeseed rotation system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 287(1), 106681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbitz, K.; Schwesig, D.; Rethemeyer, J.; Matzner, E. Stabilization of dissolved organic matter by sorption to the mineral soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005, 37, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culman, S. W.; Snapp, S. S.; Freeman, M. A.; Schipanski, M. E.; Beniston, J.; Lal, R.; Drinkwater, L. E.; Franzluebbers, A. J.; Glover, J. D.; Grandy, A. S.; Lee, J.; Six, J.; Maul, J. E.; Mirksy, S. B.; Spargo, J. T.; Wander, M. M. Permanganate Oxidizable Carbon Reflects a Processed Soil Fraction that is Sensitive to Management. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2012, 76(2), 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes Sá, J. C.; Tivet, F.; Lal, R.; Briedis, C.; Hartman, D. C.; dos Santos, J. Z.; dos Santos, J. B. Long-term tillage systems impacts on soil C dynamics, soil resilience and agronomic productivity of a Brazilian Oxisol. Soil Tillage Res. 2014, 136, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastrow, J. D.; Amonette, J. E.; Bailey, V. L. Mechanisms controlling soil carbon turnover and their potential application for enhancing carbon sequestration. Clim. Change 2007, 80(1–2), 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiorno, G.; Bünemann, E. K.; Oguejiofor, C. U.; Meier, J.; Gort, G.; Comans, R.; Mäder, P.; Brussaard, L.; de Goede, R. Sensitivity of labile carbon fractions to tillage and organic matter management and their potential as comprehensive soil quality indicators across pedoclimatic conditions in Europe. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 2019(99), 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Li, Y.; Lou, M.; Cheng, Z.; Ma, R.; Guo, H.; Zhou, J.; Jia, H.; Fan, L.; Wang, T. Microbial transformation mechanisms of particulate organic carbon to mineral-associated organic carbon at the chemical molecular level: Highlighting the effects of ambient temperature and soil moisture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 195(May), 109454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Conant, R. T.; Paul, E. A.; Paustian, K. Stabilization mechanisms of SOM implications for C saturation of soils. Plant Soil 2002, 241(2), 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C. E.; Paustian, K.; Conant, R. T.; Plante, A. F.; Six, J. Soil carbon saturation: Concept, evidence and evaluation. Biogeochemistry 2007, 86(1), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, M. F.; Ranalli, M. G.; Haddix, M. L.; Six, J.; Lugato, E. Soil carbon storage informed by particulate and mineral-associated organic matter. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12(12), 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, M. J.; Mueller, K. E.; Olk, D. C.; Sawyer, J. E.; Six, J. Integrating plant litter quality, soil organic matter stabilization, and the carbon saturation concept. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 3200–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, K. A.; Possinger, A. R.; Badgley, B. D.; Bowman, M. M.; Gallo, A. C.; Hatten, J. A.; Nave, L. E.; SanClements, M. D.; Swanston, C. W.; Weighlein, T. L.; Wieder, W. R.; Strahm, B. D. Moisture-driven divergence in mineral-associated soil carbon persistence. PNAS 2023, 120(7), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Hu, J.; Zhu, A.; Bai, J.; Wang, J.; Lin, X. No tillage enhances arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal population, glomalin-related soil protein content, and organic carbon accumulation in soil macroaggregates. J. Soils Sediments 2015, 15(5), 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruis, S. J.; Blanco-Canqui, H. How does no-till affect soil-profile distribution of roots? Can. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 104(4), 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Climatogram of experimental sites for the period 2011-2021 (data from the nearest meteo station Maribor airport, Arso meteo portal, 2025).

Figure 1.

Climatogram of experimental sites for the period 2011-2021 (data from the nearest meteo station Maribor airport, Arso meteo portal, 2025).

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of sample preparation and analyses.

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of sample preparation and analyses.

Figure 3.

Dry aggregate size distribution by mass (DASD) for different aggregate size classes under different tillage treatments (CT – ploughing, MT – minimum tillage, NTct – no-till after CT, NTmt – no-till after MT) at both sites (L – Loamy and SC – Silty clay) at 0–10 and 10–20 cm. Different letters indicate a significant difference in the mass fraction of aggregates between the treatments at the same site and depth (p<0.05); only significant differences are shown.

Figure 3.

Dry aggregate size distribution by mass (DASD) for different aggregate size classes under different tillage treatments (CT – ploughing, MT – minimum tillage, NTct – no-till after CT, NTmt – no-till after MT) at both sites (L – Loamy and SC – Silty clay) at 0–10 and 10–20 cm. Different letters indicate a significant difference in the mass fraction of aggregates between the treatments at the same site and depth (p<0.05); only significant differences are shown.

Figure 4.

Soil organic carbon (SOC, t ha-1), mineral-associated organic carbon (MAOC <50 µm, t ha-1), particulate organic carbon (POC, t ha-1), permanganate-oxidizable organic carbon (POX-C, t ha-1) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC, t ha-1) for both sites (L – Loamy and SC – Silty clay) in different tillage treatments (CT – ploughing, MT – minimum tillage, NTct – no-till after CT, NTmt – no-till after MT) at depths (0–10 cm and 10–20 cm). Different letters indicate a significant difference (p<0.05) in C fraction between the treatments and depth at the same site. Presented are means and standard errors.

Figure 4.

Soil organic carbon (SOC, t ha-1), mineral-associated organic carbon (MAOC <50 µm, t ha-1), particulate organic carbon (POC, t ha-1), permanganate-oxidizable organic carbon (POX-C, t ha-1) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC, t ha-1) for both sites (L – Loamy and SC – Silty clay) in different tillage treatments (CT – ploughing, MT – minimum tillage, NTct – no-till after CT, NTmt – no-till after MT) at depths (0–10 cm and 10–20 cm). Different letters indicate a significant difference (p<0.05) in C fraction between the treatments and depth at the same site. Presented are means and standard errors.

Figure 5.

Correlation matrix (n = 64) for aggregate stability indices and organic carbon fractions. The numbers indicate the Spearman correlation coefficient (rS), which is highlighted by the colour scale. Blank areas indicate non-significant correlations (p>0.05).

Figure 5.

Correlation matrix (n = 64) for aggregate stability indices and organic carbon fractions. The numbers indicate the Spearman correlation coefficient (rS), which is highlighted by the colour scale. Blank areas indicate non-significant correlations (p>0.05).

Table 1.

Physical properties of the bulk samples from October 2021 (Texture (%), Fine fraction <20 µm (%), dry bulk density (t m-3) and SOC (%) – soil organic carbon) at both sites (L – Loamy and SC – Silty clay) with different tillage treatments (CT – ploughing, MT – minimum tillage, NTct – no-till after CT, NTmt – no-till after MT) and depths (0–10 cm and 10–20 cm). The values are mean values ± SEM. Different lower-case letters within each column indicate a significant difference (p<0.05) between treatments at the same site, upper case letters between treatments and depth at both sites (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Physical properties of the bulk samples from October 2021 (Texture (%), Fine fraction <20 µm (%), dry bulk density (t m-3) and SOC (%) – soil organic carbon) at both sites (L – Loamy and SC – Silty clay) with different tillage treatments (CT – ploughing, MT – minimum tillage, NTct – no-till after CT, NTmt – no-till after MT) and depths (0–10 cm and 10–20 cm). The values are mean values ± SEM. Different lower-case letters within each column indicate a significant difference (p<0.05) between treatments at the same site, upper case letters between treatments and depth at both sites (p<0.05).

| Site, treatment and depth (cm) |

Texture (%) |

Fine fraction

<20 µm (%) |

Dry bulk density

(t m-3) |

SOC

(%) |

| Sand |

Silt |

Clay |

| L |

CT |

0-10 |

36.0 |

± |

1.7Ca |

44.1 |

± |

1.5Aa |

20.0 |

± |

0.3Aab |

47.4 |

± |

3.2Ba |

1.20 |

± |

0.05ABCDa |

1.5 |

± |

0.1ABa |

| 10-20 |

36.5 |

± |

2.0Ca |

43.0 |

± |

1.4Aa |

20.6 |

± |

0.6Aab |

47.5 |

± |

3.4Ba |

1.36 |

± |

0.04CDEab |

1.5 |

± |

0.1ABa |

| MT |

0-10 |

41.0 |

± |

2.7Ca |

40.6 |

± |

2.5Aa |

18.4 |

± |

0.5Aa |

43.7 |

± |

3.8Ba |

1.30 |

± |

0.03ABCDEab |

1.9 |

± |

0.1ABCDbc |

| 10-20 |

41.3 |

± |

3.2Ca |

38.7 |

± |

2.7Aa |

20.1 |

± |

0.6Aab |

43.7 |

± |

4.5Ba |

1.43 |

± |

0.06Eab |

1.4 |

± |

0.1ABa |

| NTct |

0-10 |

36.8 |

± |

1.5Ca |

43.5 |

± |

1.4Aa |

19.6 |

± |

0.7Aab |

46.8 |

± |

2.1Ba |

1.34 |

± |

0.04BCDEab |

2.0 |

± |

0.2BCDc |

| 10-20 |

37.0 |

± |

1.2Ca |

42.0 |

± |

1.0Aa |

21.0 |

± |

0.3Ab |

46.9 |

± |

1.8Ba |

1.38 |

± |

0.06DEab |

1.6 |

± |

0.1ABab |

| NTmt |

0-10 |

37.0 |

± |

2.5Ca |

43.8 |

± |

3.1Aa |

19.3 |

± |

0.6Aab |

46.5 |

± |

3.0Ba |

1.37 |

± |

0.03DEab |

1.8 |

± |

0.2ABCbc |

| 10-20 |

36.2 |

± |

2.2Ca |

42.3 |

± |

2.3Aa |

21.6 |

± |

0.3Ab |

47.7 |

± |

2.9Ba |

1.31 |

± |

0.07ABCDEab |

1.4 |

± |

0.1Aa |

| SC |

CT |

0-10 |

7.9 |

± |

0.6Ab |

44.8 |

± |

0.8Aa |

47.4 |

± |

1.4Ca |

81.4 |

± |

1.5Aa |

1.11 |

± |

0.05ABCa |

2.6 |

± |

0.2DEFa |

| 10-20 |

7.8 |

± |

0.6Ab |

44.3 |

± |

1.6Aa |

47.8 |

± |

1.0Ca |

82.3 |

± |

0.8Aa |

1.20 |

± |

0.09ABCDEa |

2.5 |

± |

0.3CDEFa |

| MT |

0-10 |

11.8 |

± |

2.3ABa |

45.4 |

± |

1.6Aa |

42.8 |

± |

2.0Ba |

76.8 |

± |

3.5Aa |

1.06 |

± |

0.02Aa |

3.1 |

± |

0.6Fa |

| 10-20 |

13.6 |

± |

2.5Ba |

40.7 |

± |

1.1Aa |

45.7 |

± |

1.4BCa |

77.6 |

± |

4.7Aa |

1.10 |

± |

0.03ABa |

2.4 |

± |

0.5CDEa |

| NTct |

0-10 |

9.9 |

± |

1.2ABa |

45.8 |

± |

1.0Aa |

44.3 |

± |

1.1BCa |

80.7 |

± |

0.4Aa |

1.15 |

± |

0.04ABCDa |

2.7 |

± |

0.3EFa |

| 10-20 |

9.4 |

± |

0.5ABa |

45.3 |

± |

1.6Aa |

45.3 |

± |

1.1BCa |

80.3 |

± |

1.0Aa |

1.12 |

± |

0.02ABCa |

2.5 |

± |

0.2CDEa |

| NTmt |

0-10 |

8.4 |

± |

0.2ABa |

45.9 |

± |

2.5Aa |

45.7 |

± |

2.7BCa |

80.5 |

± |

2.2Aa |

1.17 |

± |

0.02ABCDa |

3.0 |

± |

0.2EFa |

| 10-20 |

8.8 |

± |

0.9ABa |

43.6 |

± |

1.2Aa |

47.6 |

± |

2.0Ca |

80.7 |

± |

2.2Aa |

1.11 |

± |

0.02ABCa |

2.4 |

± |

0.0CDEa |

Table 2.

Structural indices (WSA, MWD, GMD, Dm and Dn) at both sites (L – Loamy and SC – Silty clay) with different tillage treatments (CT – ploughing, MT – minimum tillage, NTct – no-till after CT, NTmt – no-till after MT) and depths (0–10 cm and 10–20 cm). The values are mean values ± SEM. Different lower-case letters in each column indicate a significant difference between treatments, at the same site and depth (p<0.05), upper case letters between treatments, site and depth (p<0.05).

Table 2.

Structural indices (WSA, MWD, GMD, Dm and Dn) at both sites (L – Loamy and SC – Silty clay) with different tillage treatments (CT – ploughing, MT – minimum tillage, NTct – no-till after CT, NTmt – no-till after MT) and depths (0–10 cm and 10–20 cm). The values are mean values ± SEM. Different lower-case letters in each column indicate a significant difference between treatments, at the same site and depth (p<0.05), upper case letters between treatments, site and depth (p<0.05).

| Site, treatment and depth (cm) |

WSA |

MWD |

GMD |

Dm |

Dn |

|

| (%) |

(mm) |

(mm) |

|

|

|

| L |

CT |

0-10 |

87.26 |

± |

3.43Aa |

5.12 |

± |

1.06Aa |

2.49 |

± |

0.51Aa |

2.48 |

± |

0.03Da |

0.85 |

± |

0.04Aa |

| 10-20 |

95.31 |

± |

1.68Aa |

6.50 |

± |

1.06ABa |

3.48 |

± |

0.58ABa |

2.39 |

± |

0.02Da |

0.88 |

± |

0.03Aa |

| MT |

0-10 |

94.74 |

± |

1.87Aa |

5.26 |

± |

1.70Aa |

2.62 |

± |

1.01Aa |

2.51 |

± |

0.04Da |

0.79 |

± |

0.04Aa |

| 10-20 |

94.40 |

± |

1.44Aa |

5.61 |

± |

1.90ABa |

2.78 |

± |

1.05Aa |

2.50 |

± |

0.04Da |

0.80 |

± |

0.06Aa |

| NTct |

0-10 |

97.87 |

± |

1.25Aa |

7.68 |

± |

1.43ABa |

3.97 |

± |

0.87ABa |

2.41 |

± |

0.03Da |

0.79 |

± |

0.04Aa |

| 10-20 |

93.56 |

± |

2.10Aa |

7.82 |

± |

1.83ABa |

3.86 |

± |

1.05ABa |

2.42 |

± |

0.02Da |

0.78 |

± |

0.05Aa |

| NTmt |

0-10 |

98.76 |

± |

0.23Aa |

8.72 |

± |

1.57ABa |

4.61 |

± |

1.01ABa |

2.36 |

± |

0.03Da |

0.81 |

± |

0.03Aa |

| 10-20 |

95.49 |

± |

0.85Aa |

6.16 |

± |

1.30ABa |

3.16 |

± |

0.76ABa |

2.43 |

± |

0.03Da |

0.86 |

± |

0.04Aa |

| SC |

CT |

0-10 |

94.15 |

± |

4.25Aa |

10.98 |

± |

3.14BCa |

6.95 |

± |

2.34BCa |

2.11 |

± |

0.06Cb |

1.04 |

± |

0.05Aa |

| 10-20 |

95.25 |

± |

0.22Aa |

20.26 |

± |

1.39DEb |

16.81 |

± |

2.07Ca |

1.74 |

± |

0.05ABa |

0.95 |

± |

0.04Aa |

| MT |

0-10 |

99.35 |

± |

0.19Aa |

14.47 |

± |

3.49CDab |

10.34 |

± |

3.96Ca |

1.98 |

± |

0.13BCab |

0.99 |

± |

0.03Aa |

| 10-20 |

95.79 |

± |

0.76Aa |

20.16 |

± |

1.60DEb |

16.50 |

± |

2.17Ca |

1.77 |

± |

0.06ABab |

1.02 |

± |

0.10Aa |

| NTct |

0-10 |

98.99 |

± |

0.64Aa |

16.76 |

± |

0.43CDEab |

12.17 |

± |

0.32Ca |

1.91 |

± |

0.04ABCab |

0.99 |

± |

0.05Aa |

| 10-20 |

95.81 |

± |

0.14Aa |

20.65 |

± |

1.15Eb |

17.30 |

± |

1.51Ca |

1.70 |

± |

0.04Aa |

1.03 |

± |

0.02Aa |

| NTmt |

0-10 |

99.46 |

± |

0.16Aa |

18.78 |

± |

1.25DEb |

14.82 |

± |

1.58Ca |

1.79 |

± |

0.03ABab |

1.02 |

± |

0.06Aa |

| 10-20 |

95.55 |

± |

0.24Aa |

19.83 |

± |

2.00DEb |

16.34 |

± |

2.74Ca |

1.74 |

± |

0.08ABa |

0.99 |

± |

0.02Aa |

Table 3.

Organic carbon content in fine fraction <20 µm (MAOC, t ha-1), organic C sequestration potential in fine fraction (Csat, t ha-1), organic C sequestration deficit (Csd, t ha-1), MAOC fraction of SOC sequestered in fine fraction (F) and MAOC content in fine fraction (MAOC in fine fraction <20 µm, %) at both sites (L – Loamy and SC – Silty clay) under different tillage treatments (CT – ploughing, MT – minimum tillage, NTct – no-till after CT, NTmt – no-till after MT) and at 0–10 cm depth. The values are mean values ± SEM. Different lower-case letters within each column indicate a significant difference (p<0.05) between treatments at the same site and upper case letters between treatments at both sites.

Table 3.

Organic carbon content in fine fraction <20 µm (MAOC, t ha-1), organic C sequestration potential in fine fraction (Csat, t ha-1), organic C sequestration deficit (Csd, t ha-1), MAOC fraction of SOC sequestered in fine fraction (F) and MAOC content in fine fraction (MAOC in fine fraction <20 µm, %) at both sites (L – Loamy and SC – Silty clay) under different tillage treatments (CT – ploughing, MT – minimum tillage, NTct – no-till after CT, NTmt – no-till after MT) and at 0–10 cm depth. The values are mean values ± SEM. Different lower-case letters within each column indicate a significant difference (p<0.05) between treatments at the same site and upper case letters between treatments at both sites.

| Site and treat. |

MAOC <20 µm (Cfine) |

Csat |

Csd |

F1

|

MAOC in fine fraction <20 µm (%)2 |

| (t ha-1) |

L

|

CT |

10.58 |

± |

0.33Aa |

21.62 |

± |

0.59Aa |

11.04 |

± |

0.56ABb |

0.71 |

± |

0.02ABCa |

1.73 |

± |

0.04Aa |

| MT |

13.35 |

± |

0.56ABb |

20.26 |

± |

0.70Aa |

6.91 |

± |

1.17Aa |

0.66 |

± |

0.02ABCa |

2.33 |

± |

0.13Bb |

| NTct |

13.80 |

± |

0.30ABb |

21.39 |

± |

0.39Aa |

7.59 |

± |

0.50Aab |

0.66 |

± |

0.02ABCa |

2.20 |

± |

0.09ABb |

| NTmt |

13.39 |

± |

0.38ABb |

21.30 |

± |

0.55Aa |

7.90 |

± |

0.93Aab |

0.64 |

± |

0.02ABa |

2.12 |

± |

0.12ABab |

SC

|

CT |

18.22 |

± |

1.09Ca |

34.20 |

± |

0.38Ba |

15.98 |

± |

1.34Ba |

0.76 |

± |

0.02Cb |

2.08 |

± |

0.05ABa |

| MT |

17.23 |

± |

1.78BCa |

32.49 |

± |

0.92Ba |

15.26 |

± |

0.86Ba |

0.61 |

± |

0.00Aa |

2.45 |

± |

0.20Ba |

| NTct |

19.56 |

± |

1.53Ca |

33.96 |

± |

0.10Ba |

14.40 |

± |

1.58Ba |

0.74 |

± |

0.01BCb |

2.20 |

± |

0.11ABa |

| NTmt |

19.38 |

± |

0.25Ca |

33.88 |

± |

0.57Ba |

14.50 |

± |

0.66Ba |

0.64 |

± |

0.05ABCab |

2.28 |

± |

0.10ABa |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).