Submitted:

10 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1.

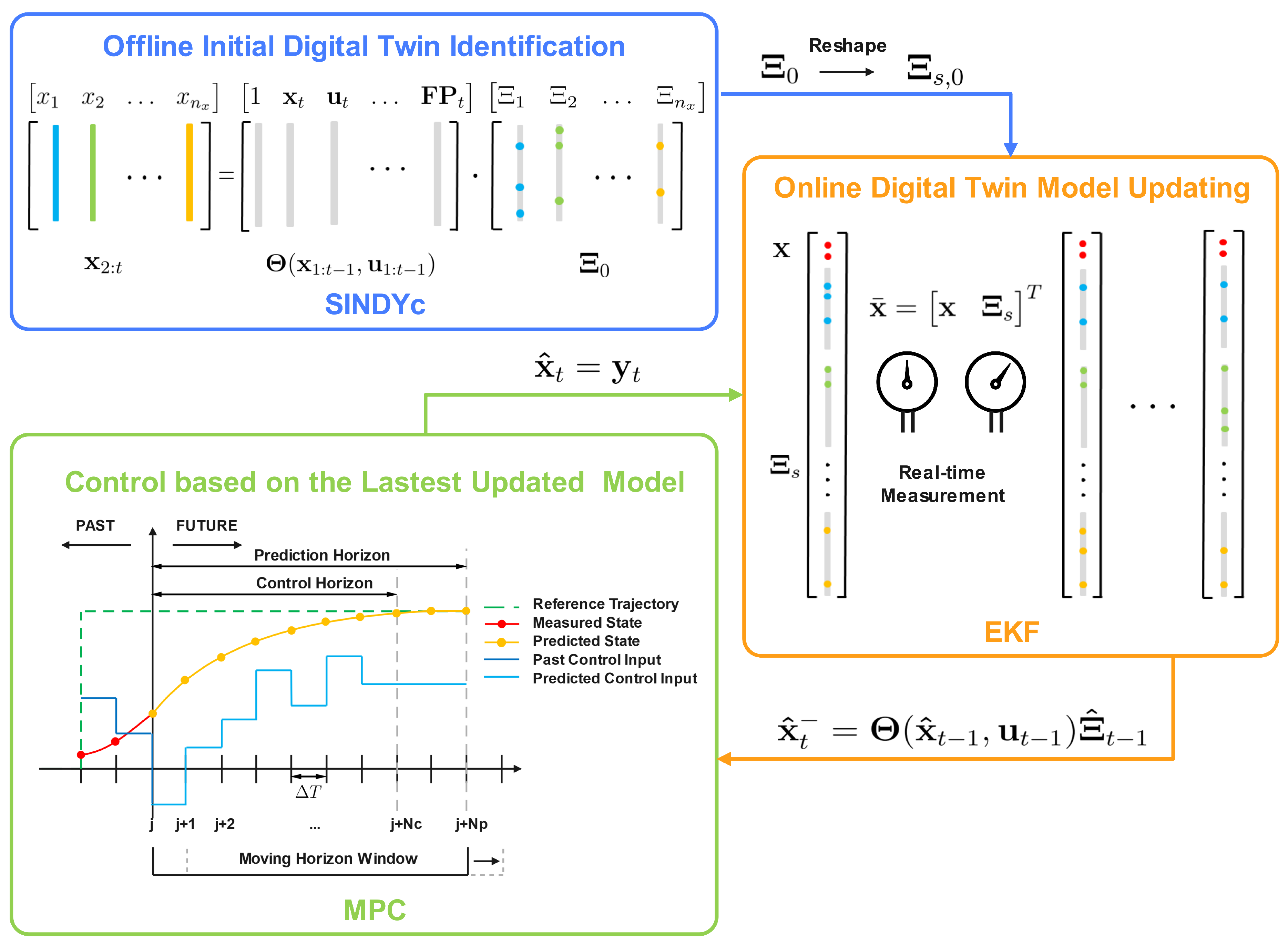

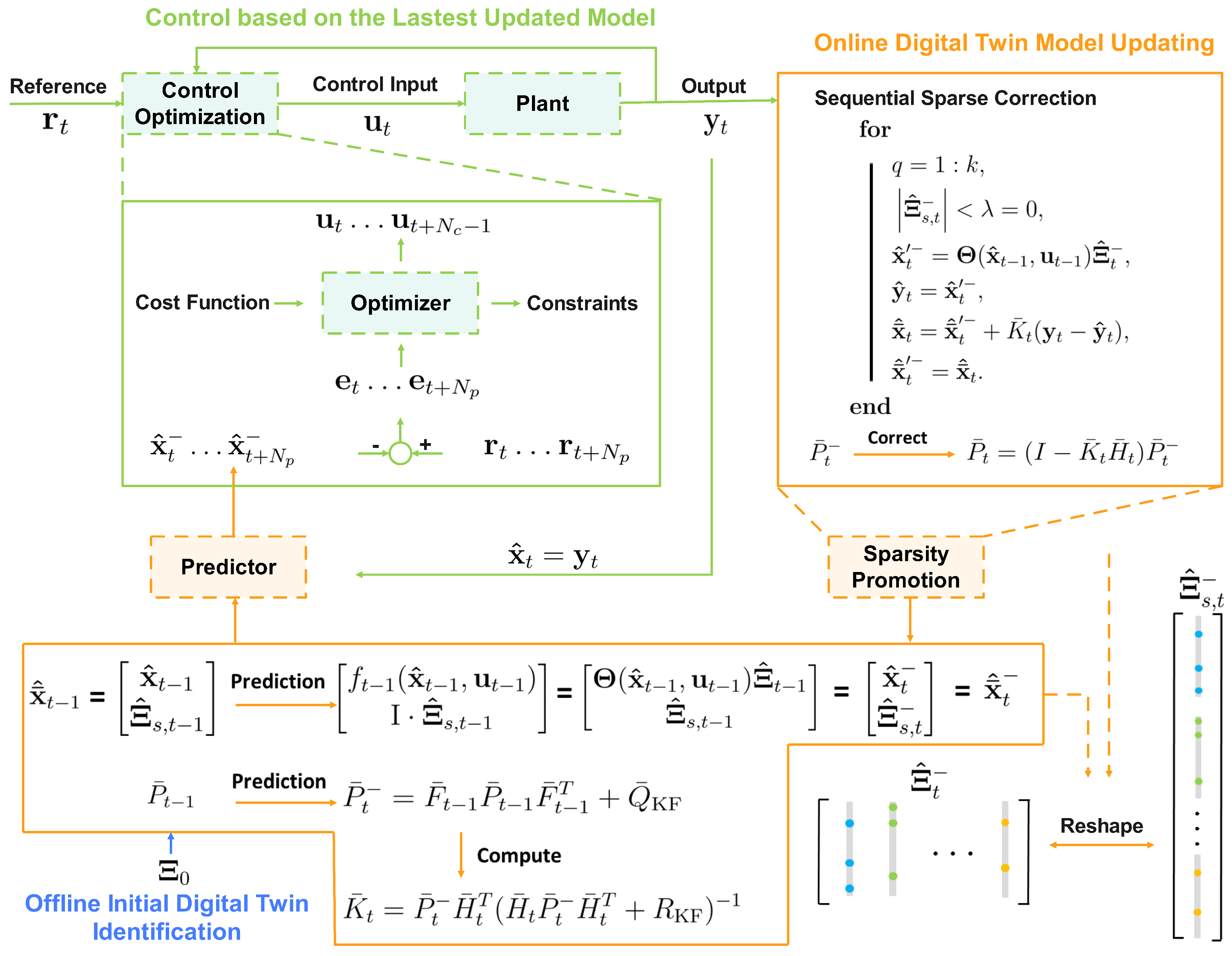

- The SINDYc-based, three-step framework is utilized to identify the initial digital twin models, considering both first-principles knowledge and data-driven techniques. Implementing such a standardized, automatic identification algorithm reduces the digital twin algorithm development time while enhancing model fidelity.

- 2.

- The integration of the EKF with SINDYc’s framework enables online digital twin model updating according to real-time measurements and prevents diminishing synchronization accuracy over time.

- 3.

- The proposed EKF-based, recursive, sparse nonlinear identification is further integrated with the MPC, using the latest updated digital twin model to provide state predictions over the prediction horizon. This integration facilitates control inputs optimization while promoting effective interactions between user instructions and the system’s dynamic behavior.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Extended Kalman Filter

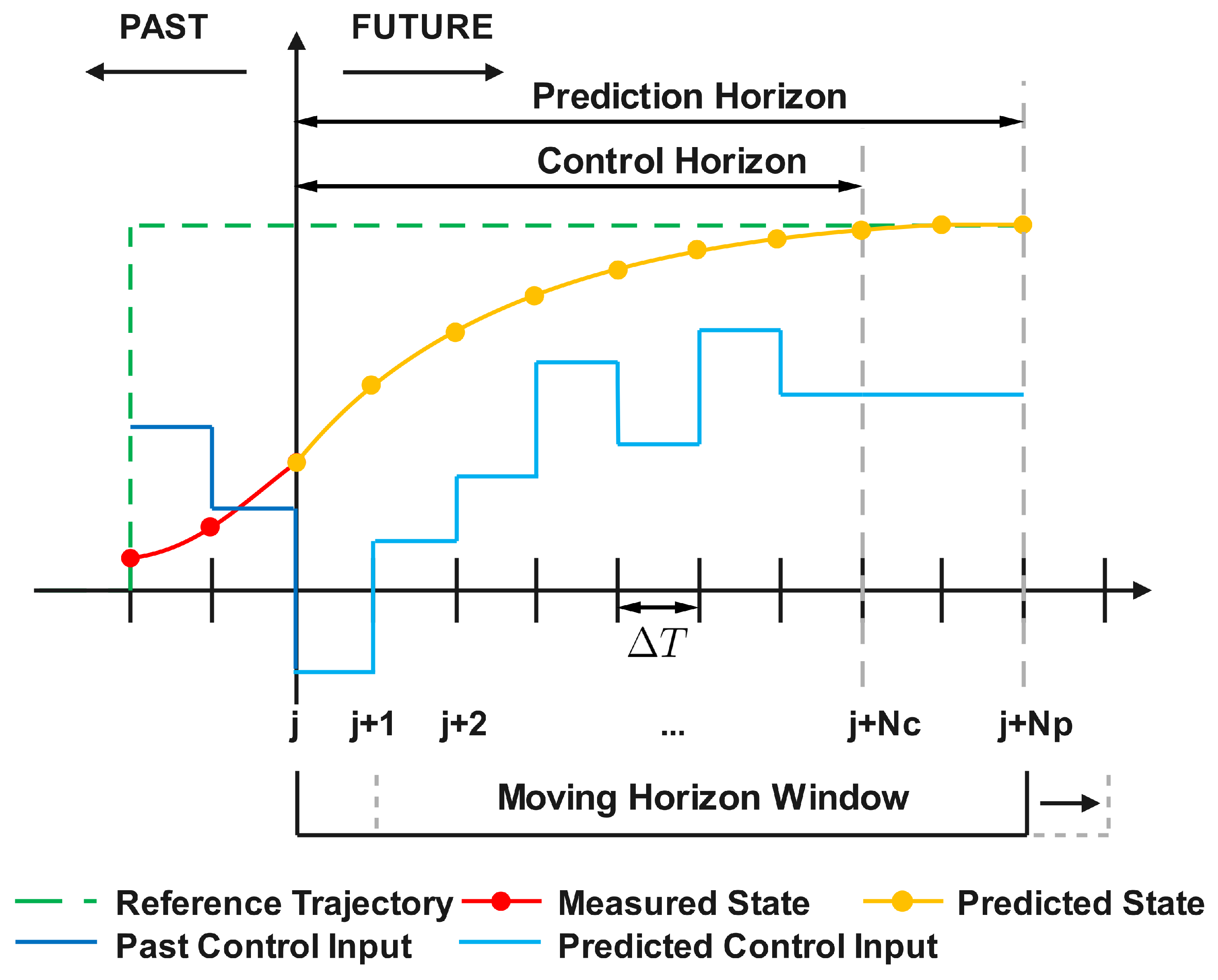

2.2. Model Predictive Control

3. Problem Statement

4. Integration of Extended Kalman Filter-Based Recursive Sparse Nonlinear Digital Twin Identification with Model Predictive Control

4.1. Feature Library Construction and Initial Identification

4.2. Extended Kalman Filter Vectors Augmentation

4.3. Sparsity-Promoting Correction

4.4. Integration with Model Predictive Control

5. Case Study

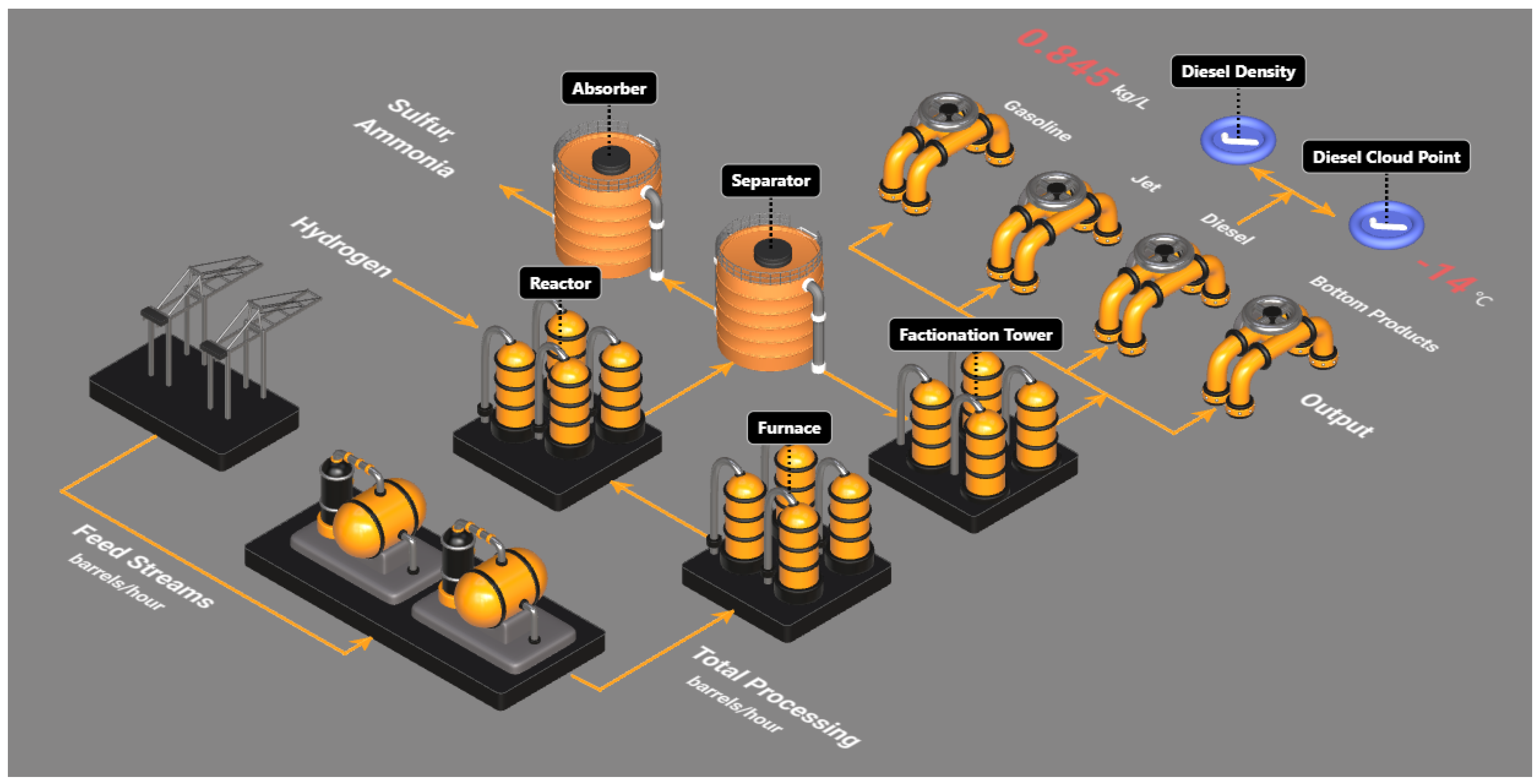

5.1. Diesel Characteristics Prediction Based on the Digital Twin Model

5.2. Simulation Examples

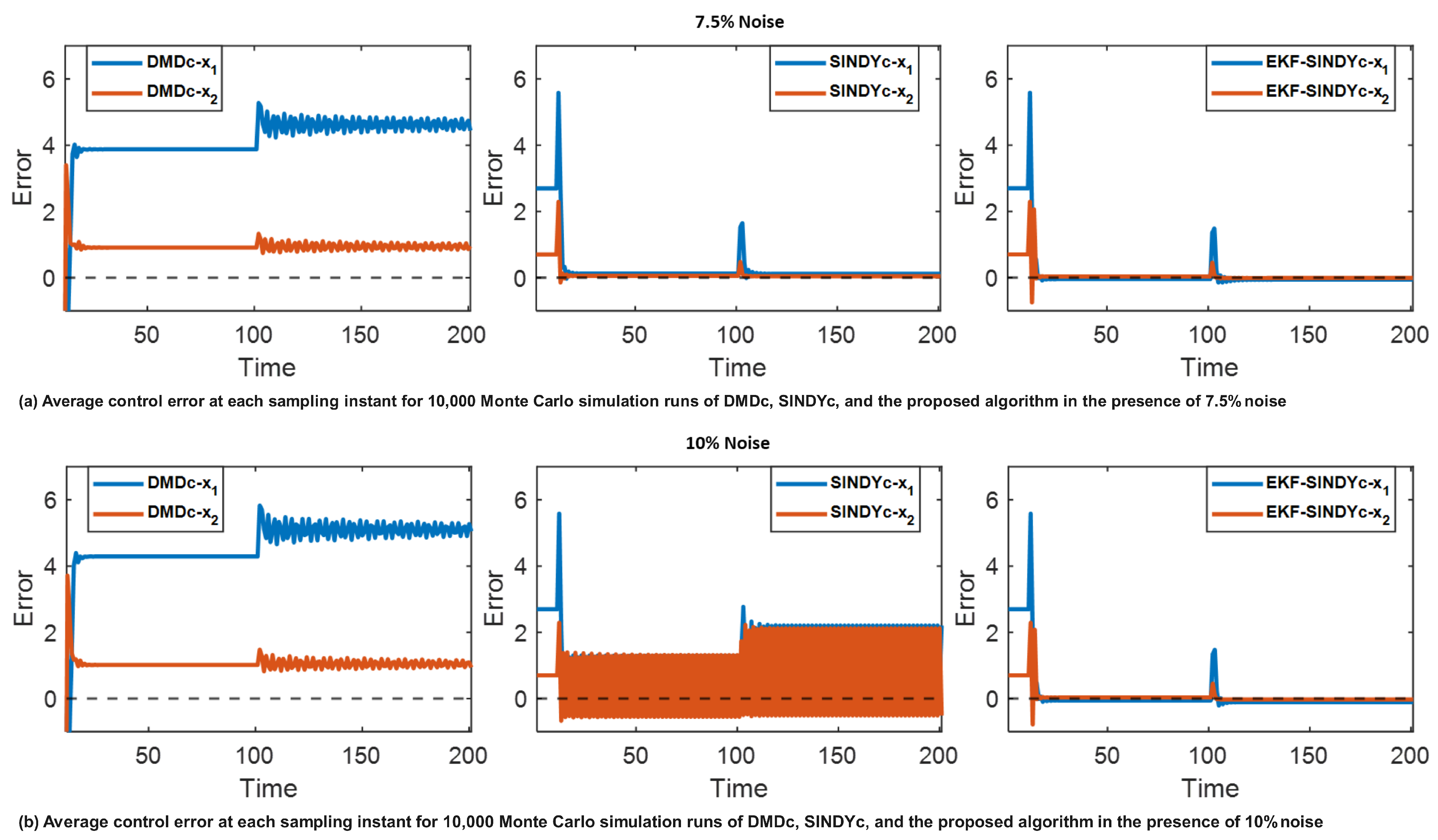

5.2.1. The Lotka-Volterra System

5.2.2. The Discrete-Time System

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Juarez, M.G.; Botti, V.J.; Giret, A.S. Digital Twins: Review and Challenges. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2021, 21, 030802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Karimi, H.R.; Kaynak, O.; Yin, S. Developments of digital twin technologies in industrial, smart city and healthcare sectors: a survey. Complex Eng. Syst. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.P.A. Emergence of Digital Twins. J. Innovation Manage. 2017, 5, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Saddik, A. Digital Twins: The Convergence of Multimedia Technologies. IEEE MultiMedia 2018, 25, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Ma, X.; Xu, Q.; Lu, Z. Research on the Digital Twin System of Welding Robots Driven by Data. Sensors 2025, 25, 3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigo, M.S.; Rivera, D.; Moreno, J.I.; Àlvarez-Campana, M.; López, D.R. Digital Twins for 5G Networks: A Modeling and Deployment Methodology. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 38112–38126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.W. Digital Twins: Past, Present, and Future. In The Digital Twin; Springer International Publishing, 2023; pp. 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Huang, S.; Moghaddam, S.K.; Lu, Y.; Wang, G.; Yan, Y.; Shi, X. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Dynamic Reconfiguration Planning for Digital Twin-Driven Smart Manufacturing Systems With Reconfigurable Machine Tools. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inform. 2024, 20, 13135–13146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancharoen, R.; Chaiprabha, K.; Wuttisittikulkij, L.; Asdornwised, W.; Saadi, M.; Phanomchoeng, G. Digital Twin for a Collaborative Painting Robot. Sensors 2022, 23, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrano-Vargas, F.; Konstantinou, G. Modular Design and Real-Time Simulators Toward Power System Digital Twins Implementation. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inform. 2023, 19, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Xiao, B.; Qi, Q.; Cheng, J.; Ji, P. Digital twin modeling. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2022, 64, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yin, S.; Li, K.; Luo, H.; Kaynak, O. Industrial applications of digital twins. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2021, 379, 20200360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Tsung, F. Sparse and Structured Function-on-Function Quality Predictive Modeling by Hierarchical Variable Selection and Multitask Learning. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inform. 2021, 17, 6720–6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, D.; Wang, H. An Adaptive Sparse Graph Learning Method Based on Digital Twin Dictionary for Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Rolling Element Bearings. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inform. 2024, 20, 10892–10900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, S.L.; Proctor, J.L.; Kutz, J.N. Discovering governing equations from data by sparse identification of nonlinear dynamical systems. PNAS 2016, 113, 3932–3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Moreira, J.; Cao, Y.; Gopaluni, B. Time-Variant Digital Twin Modeling through the Kalman-Generalized Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics. In Proceedings of the 2022 American Control Conf. (ACC), 2022; pp. 5217–5222. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Yin, S.; Li, K.; Luo, H.; Kaynak, O. Industrial applications of digital twins. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2021, 379, 20200360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvok, I.; Soldo, J.; Deur, J.; Ivanovic, V.; Zhang, Y.; Fujii, Y. Model Predictive Control for Automatic Transmission Upshift Inertia Phase. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2023, 31, 2335–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensen, J.L.; Sun, C.; Cembrano, G.; Puig, V. Model Predictive Control of Urban Drainage Systems Considering Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2023, 31, 2968–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, E.; Kutz, J.N.; Brunton, S.L. Sparse identification of nonlinear dynamics for model predictive control in the low-data limit. Proc. R. Soc. A. 2018, 474, 20180335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Vatn, J.; Yin, S. A generic framework for qualifications of digital twins in maintenance. J. Autom. Intell. 2023, 2, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D. Optimal state estimation: Kalman, H Infinity, and Nonlinear Approaches; John Wiley & Sonss, 2006; pp. 400–407. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, W.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Christofides, P.D. Supervisory Predictive Control of Standalone Wind/Solar Energy Generation Systems. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2011, 19, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennemann, J.F.; Marko, L.; Schmidt, J.; Kemmetmuller, W.; Kugi, A. Nonlinear Model Predictive Control of a Variable-Speed Pumped-Storage Power Plant. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2021, 29, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Bai, J.; Zou, H.; Yin, X.; Zhang, R. A two-dimensional model predictive iterative learning control based on the set point learning strategy for batch processes. J. Process Control 2024, 133, 103133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.R.; Pitta, R.N.; Fischer, G.G.; Neto, E.R. Optimizing Diesel Production Using Advanced Process Control and Dynamic Simulation. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2014, 47, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carelli, A.; da Souza, M. GPC Controller Performance Monitoring and Diagnosis Applied to a Diesel Hydrotreating Reactor. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2009, 42, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, R.; Alkilde, O.F.; Menjon, I.; Meyland, L.H.; Sahlertz, I.V. Statistical analysis of variation of economic parameters affecting different configurations of diesel hydrotreating unit. Energy 2019, 183, 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindermeir, A.; Kah, S.; Kavurucu, S.; Mühlner, M. On-board diesel fuel processing for an SOFC–APU—Technical challenges for catalysis and reactor design. Applied Catalysis B: Environment and Energy 2007, 70, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, E.T.; Imtiaz, S.A.; Ahmed, S.; Gopaluni, R.B. Hybrid model for a diesel cloud point soft-sensor. In Modelling of Chemical Process Systems; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 271–314. [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, S. Introduction to Nonequilibrium Phenomena. In Pattern Formations and Oscillatory Phenomena; Elsevier, 2013; pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kulikov, G.Y.; Kulikova, M.V. Accurate Numerical Implementation of the Continuous-Discrete Extended Kalman Filter. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2014, 59, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Prediction | Proposed Algorithm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Approaches | MSE | Prediction Horizon | ||

| Diesel Density | NNc | 0.85 | |||

| DMDc | 0.53 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.36 | |

| SINDYc | 0.43 | ||||

| Cloud Point | NNc | 0.87 | |||

| DMDc | 1.48 | 0.29 | 0.42 | 0.48 | |

| SINDYc | 0.64 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.