Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

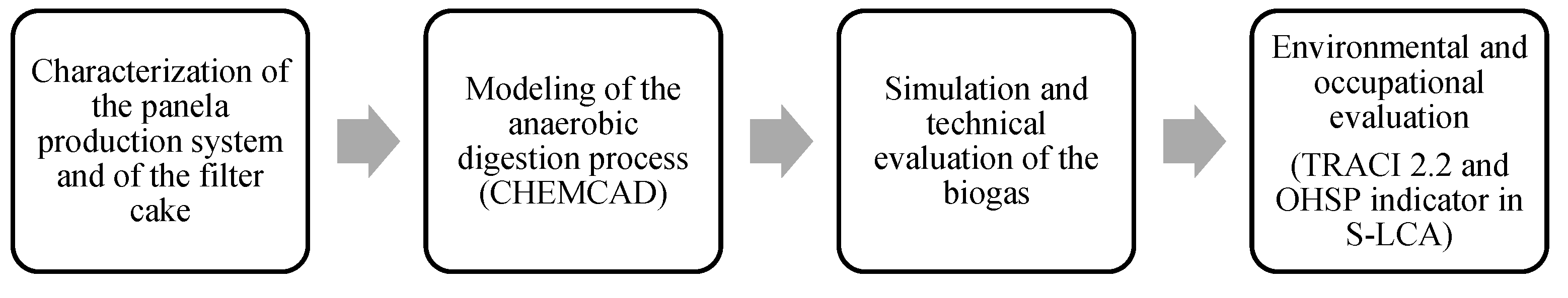

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Characterization of the Filter Cake

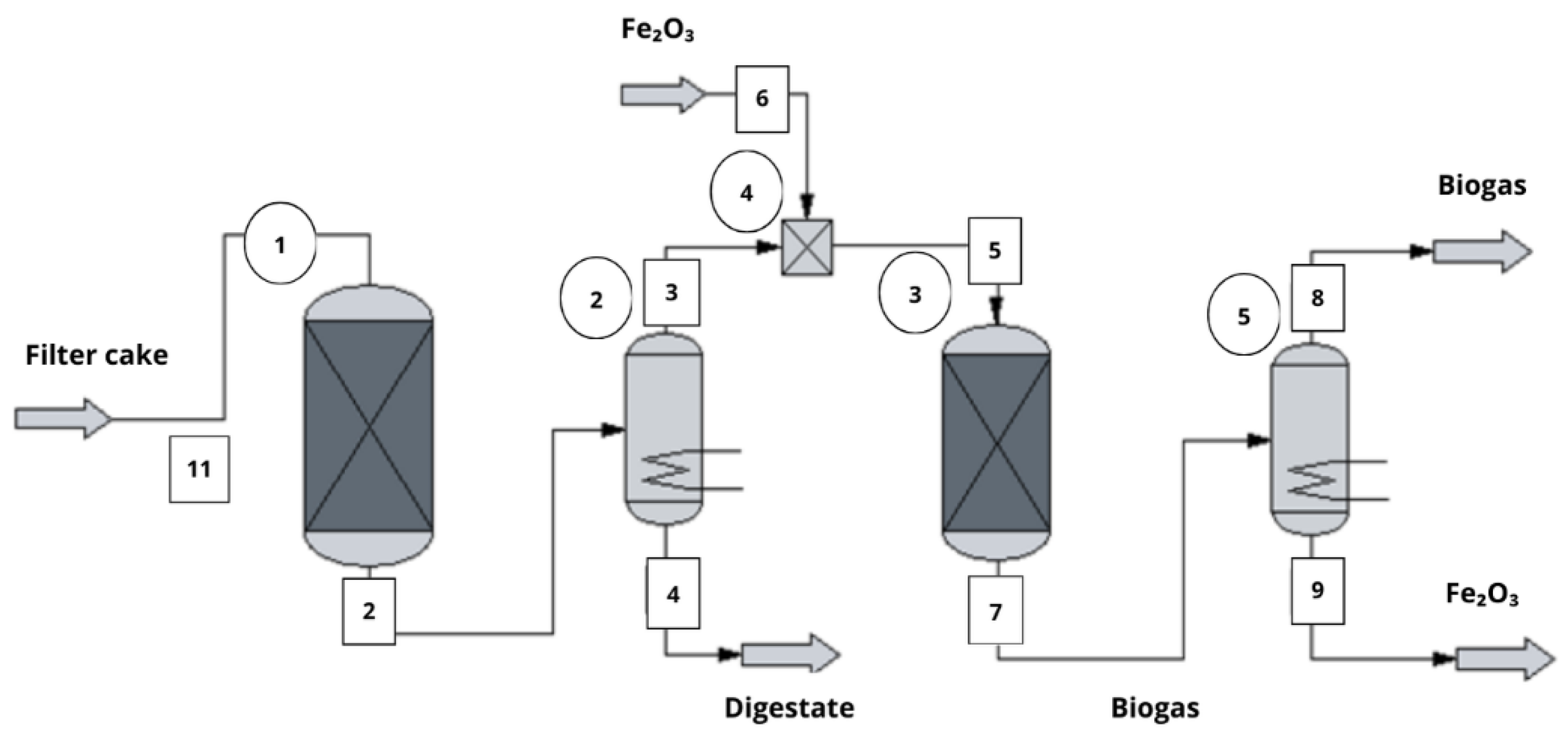

2.3. Modeling of the Process

2.4. Simulation of the Process

2.4.1. Estimation of Filter Cake Production in Pastaza

2.5. Technical Evaluation of Biogas

2.6. Environmental Assessment with TRACI 2.2

2.7. Occupational Health and Safety Potential (OHSP)

3. Results

3.1. Bibliographic Characterization

3.2. Mathematical Modeling

3.3. Modeling of the Process

3.3.1. Simulation of the Anaerobic Digestion Process

3.3.2. Estimation of Bagasse Production in the Sugar Mill

3.4. Process Simulation

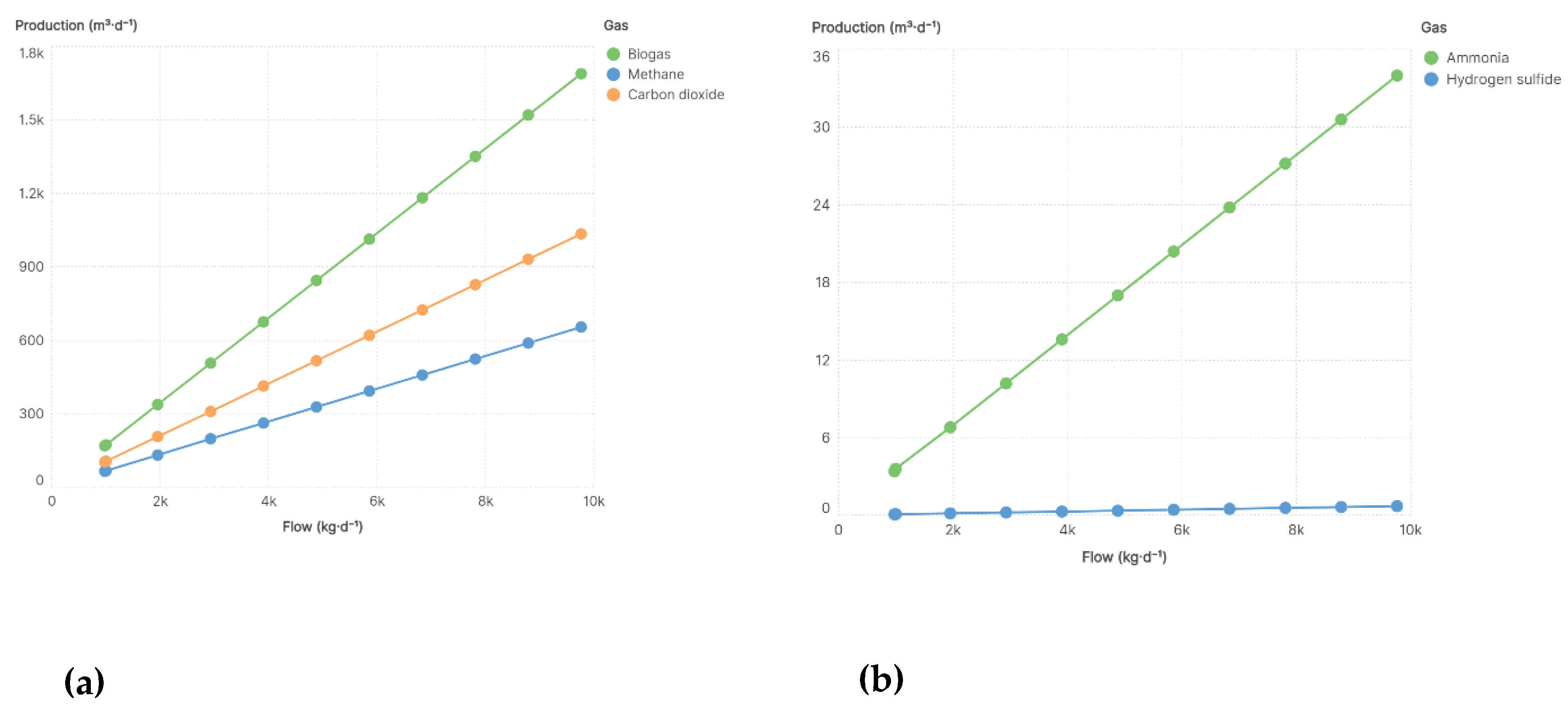

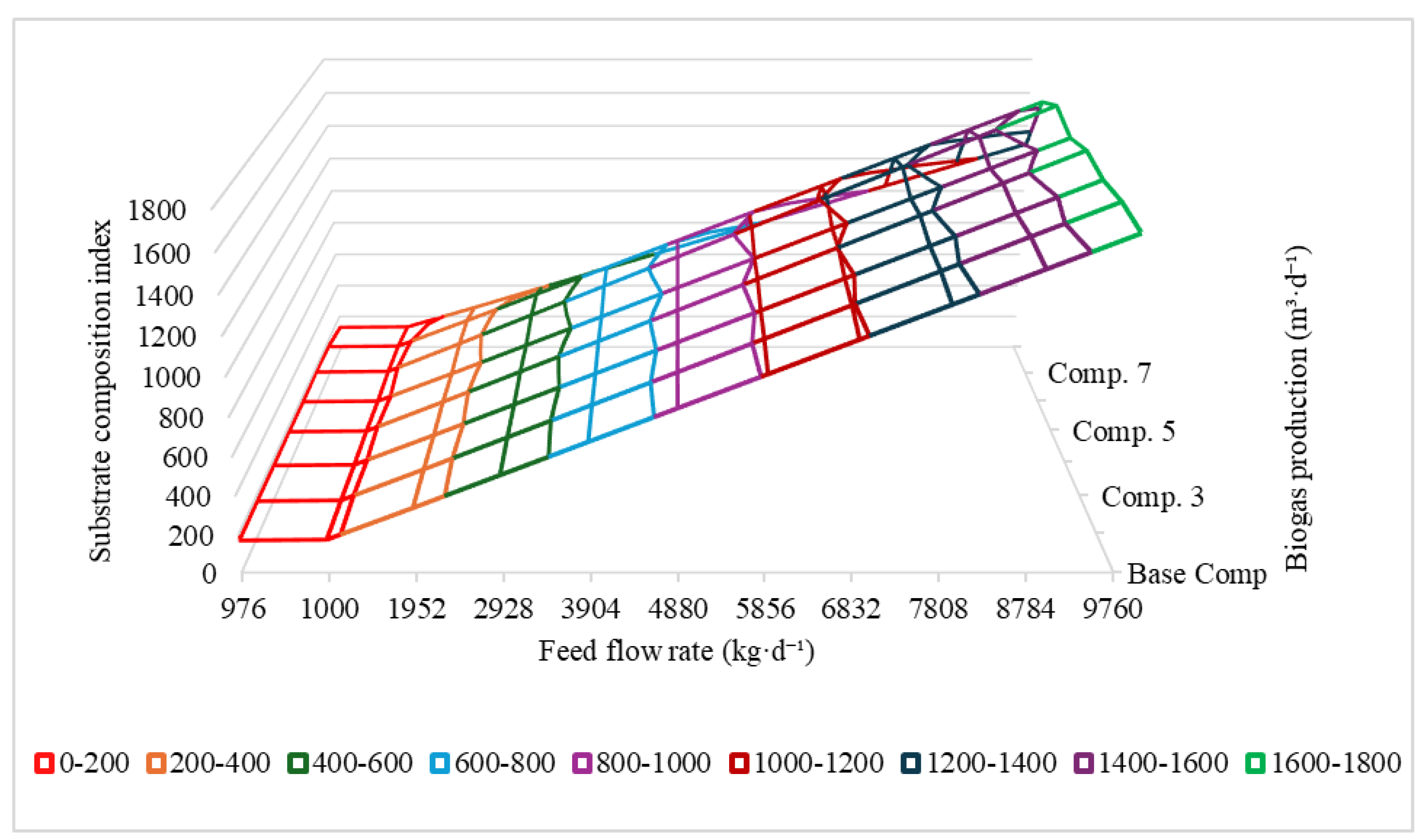

3.4.1. Base Production Case According to the Literature Review

3.4.2. Production Flow Case in Pastaza

3.4.3. Boundary Conditions for the Proposed Model

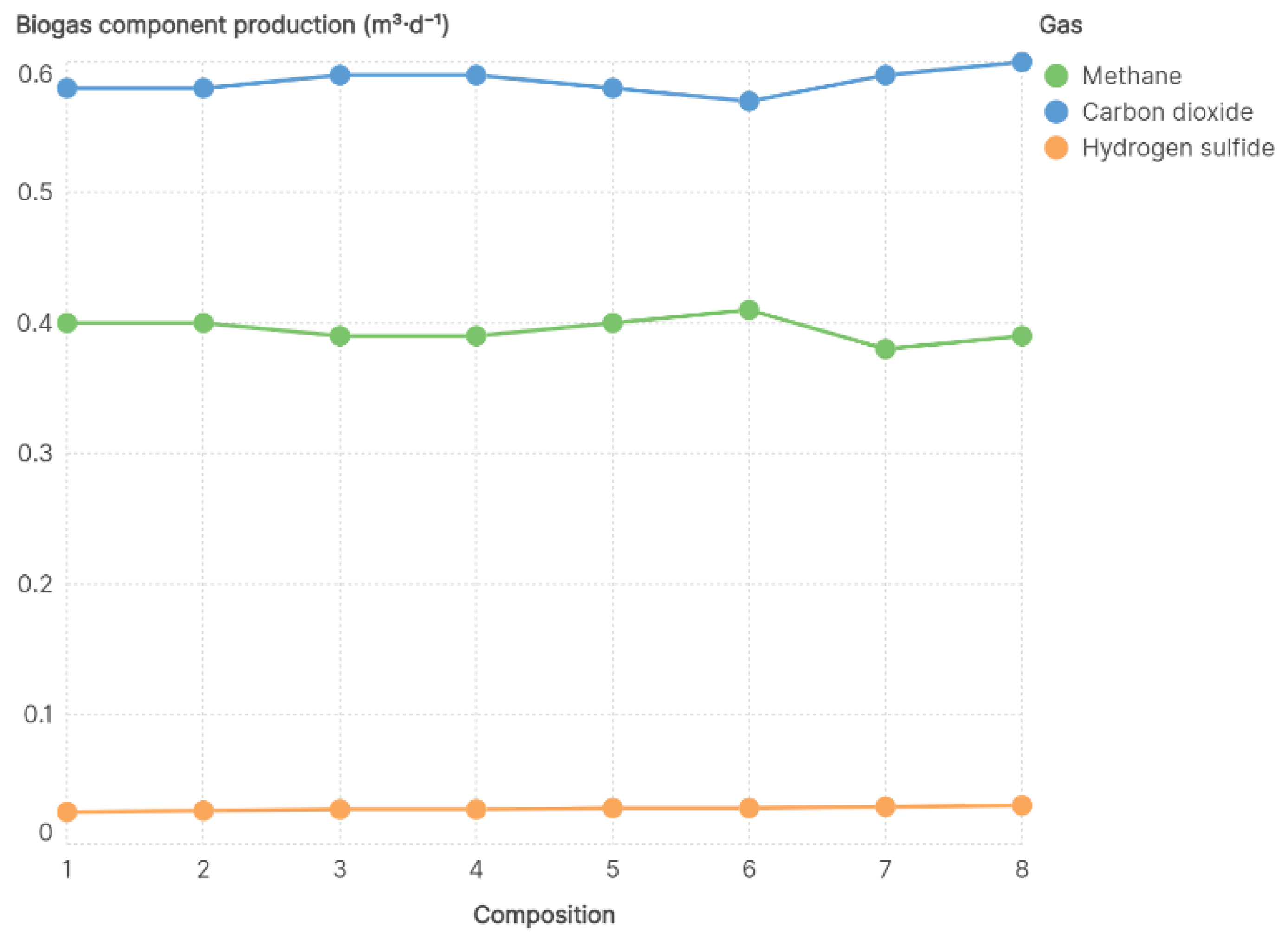

3.5. Technical Evaluation of Biogas

3.6. Comparison of the Environmental Impact of Gaseous Fuels Using TRACI

3.7. Occupational Assessment and Risk Analysis for Biogas Production

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. (2022). OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2022-2031. In (Vol. 1 Edition, pp. 180-193). OECD/FAO. https://www.fao.org/3/CC0308EN/Sugar.pdf.

- Ungureanu, N., Vlăduț, V., & Biriș, S.-Ș. Sustainable Valorization of Waste and By-Products from Sugarcane Processing. Sustainability, vol. 14(17), 11089, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hiranobe, C. T., Gomes, A. S., Paiva, F. F. G., Tolosa, G. R., Paim, L. L., Dognani, G., Cardim, G. P., Cardim, H. P., dos Santos, R. J., & Cabrera, F. C. Sugarcane Bagasse: Challenges and Opportunities for Waste Recycling. Clean Technologies, vol. 6(2), 662-699, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jugwanth, Y., Sewsynker-Sukai, Y., & Gueguim Kana, E. B. Valorization of sugarcane bagasse for bioethanol production through simultaneous saccharification and fermentation: Optimization and kinetic studies. Fuel, vol. 262, 116552, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, P., Cabello, J., Sagastume, A., Hens, L., & Vandecasteele, C. Residue from Sugarcane Juice Filtration (Filter Cake): Energy Use at the Sugar Factory. Waste and Biomass Valorization, vol. 1, 407–413, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Santos, F., Eichler, P., Machado, G., De Mattia, J., & De Souza, G. (2020). Chapter 2 - By-products of the sugarcane industry. In F. Santos, S. C. Rabelo, M. De Matos, and P. Eichler (Eds.), Sugarcane Biorefinery, Technology and Perspectives (pp. 21-48). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Carvajal-Padilla, V. P., Ambuludi-Paredes, R. R., Chele-Yumbo, E. A., Sarduy-Pereira, L. B., & Diéguez-Santana, K. Alternativas de producción más limpias para la destilería “Puro Puyo”, Pastaza, Ecuador. Revista de I+D Tecnológico, vol. Vol. 17 Núm. 1 5-13, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A., Rivera, C., & Murrillo, E. Perspectivas de uso de subproductos agroindustriales para la produccción de bioetanol. Scientia et technica, vol. Vol 17, Num 46, 232-235, 2010. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=84920977043.

- Chaile, A. P., Uboldi, M. E., & Elsa Ferreyra, M. M. Tratamiento químico de vinaza de caña de azúcar con peróxido de hidrógeno. Revista de Ciencias Ambientales, vol. 59(1), 1-19, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ibarra Guevara, R. M., Barrientos Fuentes, J. C., & Gómez Guerrero, W. A. Technical, economic, social, and environmental implications of the organic panela production in Nocaima, Colombia: The ASOPROPANOC case. Agronomía Colombiana, vol. 41(1), 1-13, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tauta Muñoz, J. L., Huertas Carranza, B., Carrillo Cortés, Y. P., & Arias Rodríguez, L. A. Comprehensive characterization of high Andean sugarcane production systems (Saccharum officinarum) for panela production in Colombia. Revista Ceres, vol. 71(e71036), 2024.

- González Rivera, V., Albán Galárraga, M. J., Casco Guerrero, E. C., & Hidalgo Guerrero, I. Critical analysis of the environmental impacts generated by the sugar cane agroindustry in the province of Pastaza - Ecuadorian Amazon. ConcienciaDigital, vol. 7(3), 6-25, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bao, K., Bieber, L.-M., Kürpick, S., Radanielina, M. H., Padsala, R., Thrän, D., & Schröter, B. Bottom-up assessment of local agriculture, forestry and urban waste potentials towards energy autonomy of isolated regions: Example of Réunion. Energy for Sustainable Development, vol. 66, 125-139, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Simeonov, I., Chorukova, E., & Kabaivanova, L. Two-Stage Anaerobic Digestion for Green Energy Production: A Review. Processes, vol. 13(2), 2025. [CrossRef]

- García-Alvarez, E., Monteagudo-Yanes, J. P., & Gómez-Sarduy, J. R. Modelo con algoritmo genético para el diseño óptimo de una planta de producción de biogás a partir de cachaza. ICIDCA. Sobre los Derivados de la Caña de Azúcar, vol. 49(3), 51-54, 2015. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=223144218011.

- Cepero Rodriguez, O., & Meneses Martin, Z. (2021). Construcción de plantas de biogás en comunidades rurales. Construction of biogas plants in rural communities. In (Vol. 1, pp. 76). Editorial Academica Española. https://www.diderich.lu/fr/livres/9786203882322/construccion-de-plantas-de-biogas-en-comunidades-rurales.

- Salazar, M., Zambrano, S., Salabarría, J., & Delgado Villafuerte, C. Evaluación de la producción de metano de vinazas mediante digestor anaerobio tipo batch. Revista Iberoamericana Ambiente & Sustentabilidad, vol. 2, 79-80, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Aghel, B., Behaein, S., & Alobaid, F. CO2 capture from biogas by biomass-based adsorbents: A review. Fuel, vol. 328, 125276, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S., Monteiro, E., Brito, P., & Vilarinho, C. A Holistic Review on Biomass Gasification Modified Equilibrium Models. Energies, vol. 12(1), 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sánchez, A., Sánchez, E. J. P., & Segura Silva, R. M. Simulation of the styrene production process via catalytic dehydrogenation of ethylbenzene using CHEMCAD® process simulator. Tecnura, vol. 21(53), 15-31, 2017.

- Wu, T., Gong, M., & Xiao, J. Preliminary sensitivity study on an life cycle assessment (LCA) tool via assessing a hybrid timber building. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, vol. 5(2), 108-113, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bare, J. TRACI 2.0: the tool for the reduction and assessment of chemical and other environmental impacts 2.0. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, vol. 13(5), 687-696, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Valle, S. B., Yaguache, B. D., Caicedo, W. O., Toscano, J. F., Yucailla, D. M., & Abril, R. V. Caracterización socioeconómica y productiva de los cañicultores de la provincia Pastaza, Ecuador. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science, vol. 55(2), 2021. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2079-34802021000200004&lng=es&tlng=es.

- Gálvez, L., Cabello, A., & Villamil, G. (2002). Manual de los derivados de la caña de azúcar. In I. C. d. I. d. l. D. d. l. C. d. Azucar (Ed.), (Vol. Tercera Edición (inglés, español y portugués), pp. 421). ICIDCA,.

- Aguilar, N., Rodríguez, D., & Castillo, A. Azúcar, coproductos y subproductos en la diversificación de la agroindustria de la caña de azúcar. Revista VIRTUALPRO vol. 106(11), 1-28, 2010. https://www.virtualpro.co/biblioteca/azucar-coproductos-y-subproductos-en-la-diversificacion-de-la-agroindustria-de-la-cana-de-azucar#comocitar.

- Martínez, R., Castro, I., & Oliveros, M. Characterization of Products from Sugar Cane Mud. Revista de la Sociedad Química de México, vol. 46(1), 64-66, 2002. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0583-76932002000100011&lng=es.

- Singh, B., Szamosi, Z., & Siménfalvi, Z. Impact of mixing intensity and duration on biogas production in an anaerobic digester: a review. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, vol. 40(4), 508-521, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Valle, S. B., Yaguache, B. D., Caicedo, W. O., Toscano, J. F., Yucailla, D. M., & Abril, R. V. Socio-economic and productive characterization of sugarcane farmers in Pastaza province, Ecuador. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science, vol. 55, 1-7, 2021. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/6537/653769345004/.

- Cerda-Mejia, V., Yordi, E., Cerda Mejía, G., Vinocunga-Pillajo, R. D., Perez, A., & González, E. Procedure for the determination of operation and design parameters considering the quality of non-centrifugal cane sugar. Entre Ciencia e Ingeniería, vol. 16 (31), 43-50, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Szwaja, S., Tutak, W., Grab-Rogaliński, K., Jamrozik, A., & Kociszewski, A. Selected combustion parameters of biogas at elevated pressure-temperature conditions. Silniki Spalinowe, vol. 51(1), 40-47, 2012. http://www.combustion-engines.eu/numbers/5/228.

- Telmo, C., & Lousada, J. Heating values of wood pellets from different species. Biomass and Bioenergy, vol. 35(7), 2634-2639, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R., Kumar, M., & Amit, R. K. An Experimental Study to Evaluate the Calorific Values of Bagasse after Solar Cabinet Drying. International Journal on Recent Innovation Trends in Computing Communication, vol. Vol. 4, No. 6, 239-241, 2016.

- Ometto, J. P., Gorgens, E. B., de Souza Pereira, F. R., Sato, L., de Assis, M. L. R., Cantinho, R., Longo, M., Jacon, A. D., & Keller, M. A biomass map of the Brazilian Amazon from multisource remote sensing. Scientific Data, vol. 10(1), 668, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bernal, R., López, L., Ríos Obregón, J., Jiménez, J., García, Y., & Arteaga, Y. Thermoalkaline pretreatment influence on anaerobic biodegradability of filter cake for methane production. MOL2NET, vol. 3, 1-7, 2017.

- Janke, L., Leite, A., Nikolausz, M., Schmidt, T., Liebetrau, J., Nelles, M., & Stinner, W. Biogas production from sugarcane waste: assessment on kinetic challenges for process designing. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 16(9), 20685-20703, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Acurex Environmental Corporation. Emission Factor Documentation for AP-42 Section 1.5: Liquified Petroleum Gas Combustion. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2020-09/documents/emission_factor_documentation_for_ap42_section_1.5_liquified_petroleum_gas.pdf (29 october 2025).

- Environmental Protection Agency. AP-42 Section 1.4: Natural Gas Combustion. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2020-09/documents/1.4_natural_gas_combustion.pdf (29 october 2025).

- The Climate Registry. 2023 Default Emission Factors. The Climate Registry. https://theclimateregistry.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/2023-Default-Emission-Factors-Final.pdf (29 october 2025).

- Tsalidis, G. A. Introducing the Occupational Health and Safety Potential Midpoint Impact Indicator in Social Life Cycle Assessment. Sustainability, vol. 16(9), 2024. [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Indicators and data tools. https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/ (29 october 2025).

- Instituto Cubano de Investigaciones de los Derivados de la Caña de Azúcar. (2000). Manual de los Derivados de la Caña de Azúcar. Instituto Cubano de Investigaciones de los Derivados de la Caña de Azúcar. https://www.academia.edu/10912163/MANUAL_DE_LOS_DERIVADOS_DE_LA_CA%C3%91A?auto=download.

- Barahmand, Z., & Samarakoon, G. Sensitivity Analysis and Anaerobic Digestion Modeling: A Scoping Review. Fermentation, vol. 8(11), 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wongarmat, W., Sittijunda, S., Imai, T., & Reungsang, A. Co-digestion of filter cake, biogas effluent, and anaerobic sludge for hydrogen and methane production: Optimizing energy recovery through two-stage anaerobic digestion. Carbon Resources Conversion, vol. 8(2), 100248, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Costa, C., Cornacchia, M., Pagliero, M., Fabiano, B., Vocciante, M., & Reverberi, A. P. Hydrogen Sulfide Adsorption by Iron Oxides and Their Polymer Composites: A Case-Study Application to Biogas Purification. Materials, vol. 13(21), 4725, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ciahotný, K., & Kyselová, V. Hydrogen Sulfide Removal from Biogas Using Carbon Impregnated with Oxidants. Energy & Fuels, vol. 33(6), 5316-5321, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Lara-Haro, D. M., Argothy-Almeida, L. A., Martínez-Mesias, J. P., & Mejía-Chávez, M. A. El impacto de las crisis en el desempeño del sector agropecuario del Ecuador. Revista Finanzas y Política Económica, vol. 14(1), 167-186, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cepero, L., Savran, V., Blanco, D., Díaz, M., Suárez, J., & Palacios, A. Producción de biogás y bioabonos a partir de efluentes de biodigestores. Pastos y Forrajes, vol. 35(2), 219-226, 2012. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=269125071009.

- Talha, Z., Hamid, A., Ding, W., & Osman, B. H. Biogas Production from Filter Mud in (CSTR) Reactor, Co-digested with Various Substrates (Wastes). Agricultural Environmental Sciences Journal, vol. 1(1), 15-24, 2017.

- Werkneh, A. A. Biogas impurities: environmental and health implications, removal technologies and future perspectives. Heliyon, vol. 8(10), e10929, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Dauknys, R., & Mažeikienė, A. Process Improvement of Biogas Production from Sewage Sludge Applying Iron Oxides-Based Additives. Energies, vol. 16(7), 3285, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Xu, J., Sheng, L., Liu, X., Zong, M., & Yao, D. J. E. Anaerobic Digestion Technology for Methane Production Using Deer Manure Under Different Experimental Conditions. Energies, vol. 12(9), 1819, 2019.

- Weckerle, T., Ewald, H., Guth, P., Knorr, K. H., Philipp, B., & Holert, J. Biogas digestate as a sustainable phytosterol source for biotechnological cascade valorization. Microb Biotechnol, vol. 16(2), 337-349, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Vu, H. P., Nguyen, L. N., Wang, Q., Ngo, H. H., Liu, Q., Zhang, X., & Nghiem, L. D. Hydrogen sulphide management in anaerobic digestion: A critical review on input control, process regulation, and post-treatment. Bioresource Technology, vol. 346, 126634, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kefalew, T., Tilinti, B., & Betemariyam, M. The potential of biogas technology in fuelwood saving and carbon emission reduction in Central Rift Valley, Ethiopia. Heliyon, vol. 7(9), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gross, T., Zahnd, A., Adhikari, S., Kaphre, A., Sharma, S., Baral, B., Kumar, S., & Hugi, C. Potential of biogas production to reduce firewood consumption in remote high-elevation Himalayan communities in Nepal [10.1051/rees/2017021]. Renew. Energy Environ. Sustain., vol. 2, 6, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Pillarisetti, A., Ye, W., & Chowdhury, S. Indoor Air Pollution and Health: Bridging Perspectives from Developing and Developed Countries. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, vol. 47(Volume 47, 2022), 197-229, 2022. [CrossRef]

- da Silva Aires, F. I., Freitas, I. S., dos Santos, K. M., da Silva Vieira, R., Nascimento Dari, D., Junior, P. G. d. S., Serafim, L. F., Menezes Ferreira, A. Á., Galvão da Silva, C., da Silva, É. D. L., Andrea Sindeaux de Oliveira, L., Maria Santiago de Castro, L., Araújo Oliveira, L., Barroso dos Santos, M. T., Hebert da Silva Felix, J., da Silva Sousa, P., Simão Neto, F., & Sousa dos Santos, J. C. Sugarcane Bagasse as a Renewable Energy Resource: A Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research Trends. ACS Sustainable Resource Management, vol. 2(8), 1551-1561, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hassa, W., Fiala, K., Apiraksakorn, J., & Leesing, R. Sugarcane bagasse valorization through integrated process for single cell oil, sulfonated carbon-based catalyst and biodiesel co-production. Carbon Resources Conversion, vol. 8(2), 100245, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bakkaloglu, S., & Hawkes, A. A comparative study of biogas and biomethane with natural gas and hydrogen alternatives [10.1039/D3EE02516K]. Energy & Environmental Science, vol. 17(4), 1482-1496, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kolb, S., Plankenbühler, T., Hofmann, K., Bergerson, J., & Karl, J. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of renewable gas technologies: A comparative review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 146, 111147, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Travis, K. R., Nault, B. A., Crawford, J. H., Bates, K. H., Blake, D. R., Cohen, R. C., Fried, A., Hall, S. R., Huey, L. G., Lee, Y. R., Meinardi, S., Min, K. E., Simpson, I. J., & Ullman, K. Impact of improved representation of volatile organic compound emissions and production of NOx reservoirs on modeled urban ozone production. Atmos. Chem. Phys., vol. 24(16), 9555-9572, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tian, G., Yeung, M., & Xi, J. H2S Emission and Microbial Community of Chicken Manure and Vegetable Waste in Anaerobic Digestion: A Comparative Study. Fermentation, vol. 9(2), 169, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jayawickrama, K., Ruparathna, R., Seth, R., Biswas, N., Hafez, H., & Tam, E. Challenges and Issues of Life Cycle Assessment of Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Waste. Environments, vol. 11(10), 217, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Abanades, S., Abbaspour, H., Ahmadi, A., Das, B., Ehyaei, M. A., Esmaeilion, F., El Haj Assad, M., Hajilounezhad, T., Jamali, D. H., Hmida, A., Ozgoli, H. A., Safari, S., AlShabi, M., & Bani-Hani, E. H. A critical review of biogas production and usage with legislations framework across the globe. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, vol. 19(4), 3377-3400, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, H., Saady, N. M. C., & Zendehboudi, S. Safety in biogas plants: An analysis based on international standards and best practices. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, vol. 200, 107390, 2025. [CrossRef]

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Base comp. |

Comp. 2 | Comp. 3 | Comp. 4 | Comp. 5 | Comp. 6 | Comp. 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 70.72 | 70.72 | 70.72 | 70.72 | 70.72 | 70.72 | 70.72 | ||

| Protein | 3.81 | 4.68 | AVG Protein | Lower limit Protein | Upper limit Protein | AVG Protein | AVG Protein | AVG Protein | AVG Protein |

| Lipids | 3.22 | 4.1 | AVG Lipids | Upper limit Lipids | Lower limit Lipids | AVG Lipids | AVG Lipids | AVG Lipids | AVG Lipids |

| Ash | 2.34 | 3.51 | AVG Ash | AVG Ash | AVG Ash | Lower limit Ash | Upper limit Ash | AVG Ash | AVG Ash |

| Sucrose | 2.93 | 4.1 | AVG Sucrose | AVG Sucrose | AVG Sucrose | Upper limit Sucrose | Lower limit Sucrose | AVG Sucrose | AVG Sucrose |

| Fiber | 4.98 | 7.32 | AVG Fiber | AVG Fiber | AVG Fiber | AVG Fiber | AVG Fiber | Lower limit Fiber | Upper limit Fiber |

| Others | 7.61 | 9.96 | AVG Others | AVG Others | AVG Others | AVG Others | AVG Others | Upper limit Others | Lower limit Others |

| Flow for Pastaza | |

|---|---|

| F (100%) | THV |

| F (90%) | THV-(90%*THV) |

| F (80%) | THV-(80%*THV) |

| F (70%) | THV-(70%*THV) |

| F (60%) | THV-(60%*THV) |

| F (50%) | THV-(50%*THV) |

| F (40%) | THV-(40%*THV) |

| F (30%) | THV-(30%*THV) |

| F (20%) | THV-(20%*THV) |

| F (10%) | THV-(10%*THV) |

| Amino acids / (%) | Value | Author | Fatty acids / (%) | Value | Author | Minerals and others / (%) | Value | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude protein | 4.39 | [24] | Total lipids | 3.51 | [26] | Ash | 2.93 | [41] |

| Aspartic acid | 0.56 | Myristic acid | 0.013 | Silicon (Si) | 0.189 | [25] | ||

| Threonine | 0.33 | Palmitic acid | 0.385 | Zinc (Zn) | 0.357 | |||

| Glutamic acid | 0.47 | Stearic acid | 0.082 | Iron (Fe) | 1.401 | |||

| Methionine | 0.06 | Oleic acid | 0.084 | Magnesium (Mg) | 0.49 | |||

| Isoleucine | 0.27 | Linoleic acid | 0.025 | Copper (Cu) | 0.028 | |||

| Alanine | 0.74 | Linolenic acid | 0.04 | Manganese (Mn) | 0.112 | |||

| Valine | 0.45 | Arachidonic acid | 0.004 | Aluminum (Al) | 0.35 | |||

| Leucine | 0.46 | n-tetracosanoic acid | 0.013 | Sucrose | 3.52 | [41] | ||

| Tyrosine | 0.08 | n-hexacosanoic acid | 0.006 | Fiber | 6.15 | |||

| Phenylalanine | 0.17 | n-octacosanoic acid | 0.488 | Cellulose | 4.378 | [5] | ||

| Tryptophan | 0.15 | n-nonacosanoic acid | 0.023 | Hemicellulose | 1.181 | |||

| Histidine | 0.28 | n-triacontanoic acid | 0.286 | Lignin | 0.59 | |||

| Lysine | 0.27 | n-dotriacontanoic acid | 0.158 | Others | 8.78 | [41] | ||

| Arginine | 0.12 | n-tetratriacontanoic acid | 0.212 | n-tetracosanol | 0.712 | [26] | ||

| Stigmasterol | 0.524 | n-hexacosanol | 0.558 | |||||

| Campesterol | 0.572 | n-heptacosanol | 0.294 | |||||

| β-sitosterol | 0.602 | n-octacosanol | 6.086 | |||||

| n-nonacosanol | 0.294 | |||||||

| n-triacontanol | 0.872 | |||||||

| n-dotriacontanol | 0.172 | |||||||

| n-tetratricontanol | 0.335 |

| Component | Chemical Reaction |

|---|---|

| Oligosaccharide | |

| Sucrose | |

| Polysaccharides | |

| Hemicellulose | |

| Cellulose | |

| Cross-linked phenolic polymers | |

| Lignin | |

| Amino acids | |

| Aspartic acid | |

| Fatty acids | |

| Linoleic acid | |

| Higher primary aliphatic alcohols | |

| N-tetracosanol | |

| Phytosterols or sterols of plant origin | |

| Stigmasterol |

| Percentage of total flow fed | Flow for Pastaza (kg·d⁻¹) |

|---|---|

| 10% | 976 |

| 20% | 1,952 |

| 30% | 2,928 |

| 40% | 3,904 |

| 50% | 4,880 |

| 60% | 5,856 |

| 70% | 6,832 |

| 80% | 7,808 |

| 90% | 8,784 |

| 100% | 9,760 |

| Feed flow (kg·d⁻¹) | Biogas production (m³·d⁻¹) | Bagasse saved (kg·d⁻¹) | Wood saved (kg·d⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1.909 | 0.996 |

| 400 | 71.16 | 135.91 | 70.86 |

| 9,760 | 1,736.4 | 3,316.43 | 1,728.99 |

| Annual ecological equivalent | 631.08 t·year⁻¹ (≈ 3.63 ha ≈ 902 trees) |

| Fuel | Climate change (kg CO₂ eq) | Acidification (kg SO₂ eq) | Smog (kg O₃ eq) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biogas | 17.40 | 0.00516 | 0.05894 |

| Methane (natural gas) | 2.875 | 0.00140 | 0.04965 |

| LPG | 3.07 | 0.00280 | 0.09919 |

| Propane | 3.05 | 0.00210 | 0.07440 |

| Process stage | Main risks | Hours worked/year | Accidents/year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Receiving and grinding the filter cake |

Noise, dust, and heat | 1,800 | 2 |

| Loading the biodigester | Contact with waste and gases | 1,600 | 1 |

| Operating the biodigester | Internal pressure and methane gas | 2,000 | 1 |

| Cleaning and discharging the digestate |

Biological and thermal risk | 1500 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.