Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

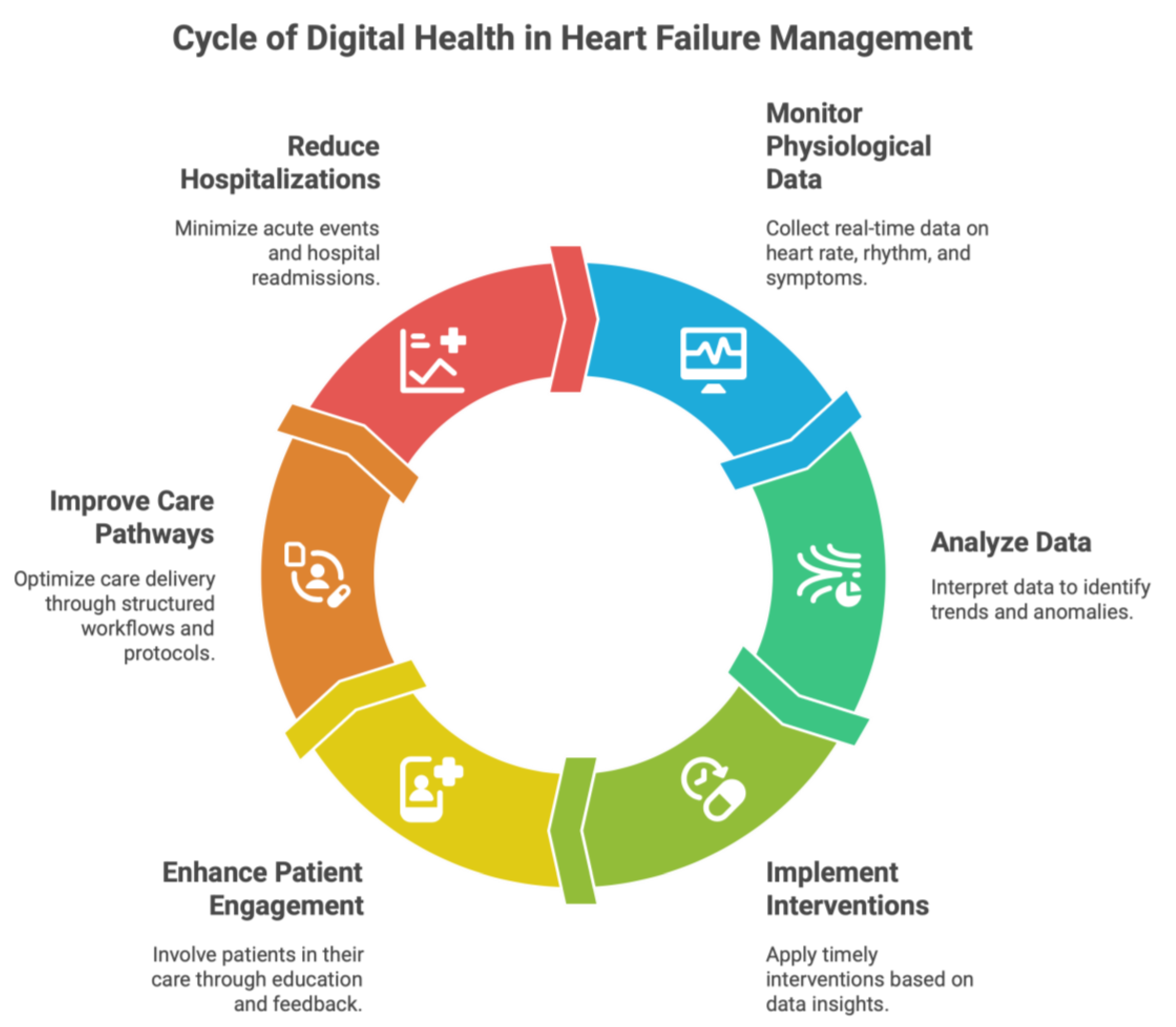

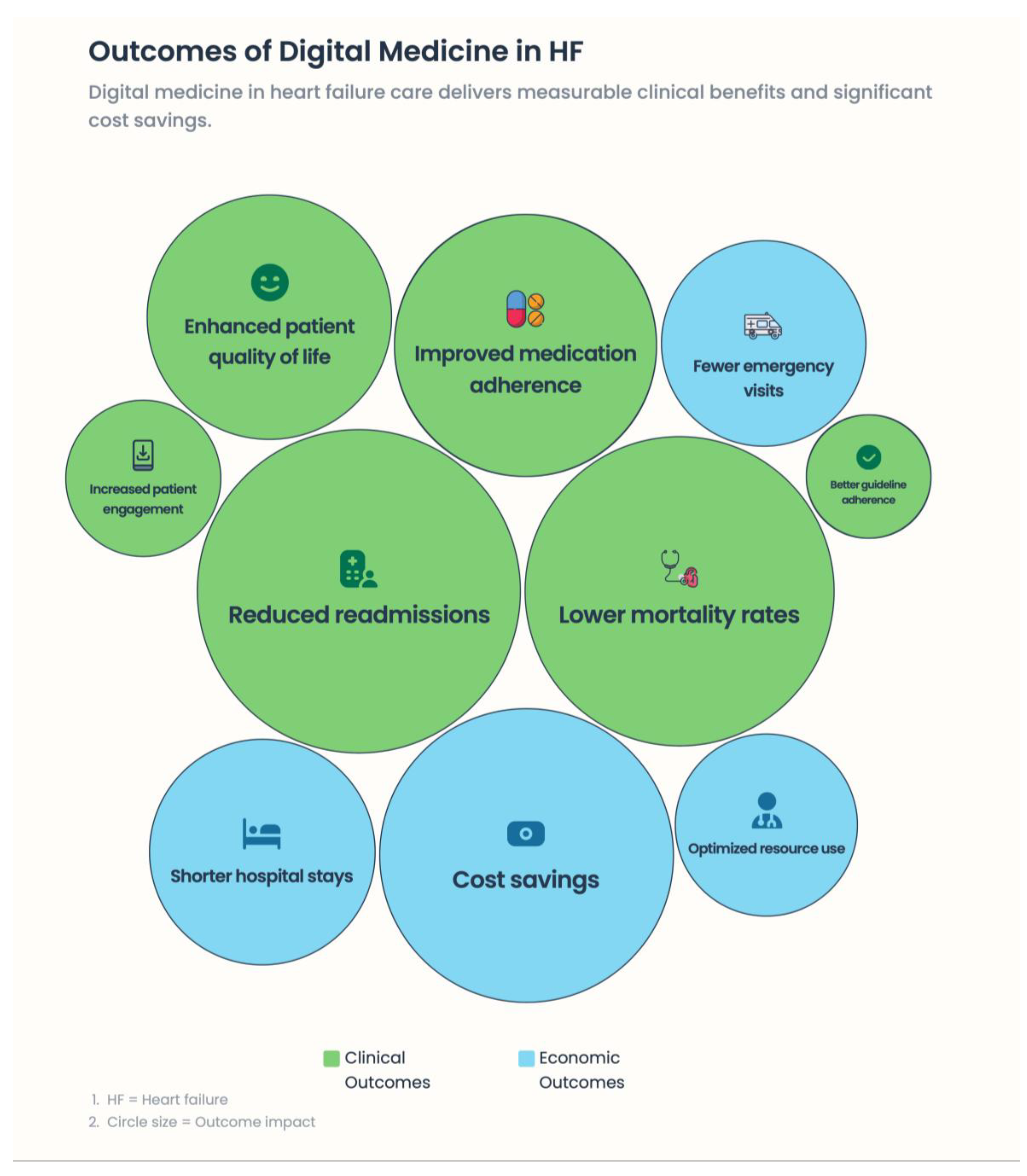

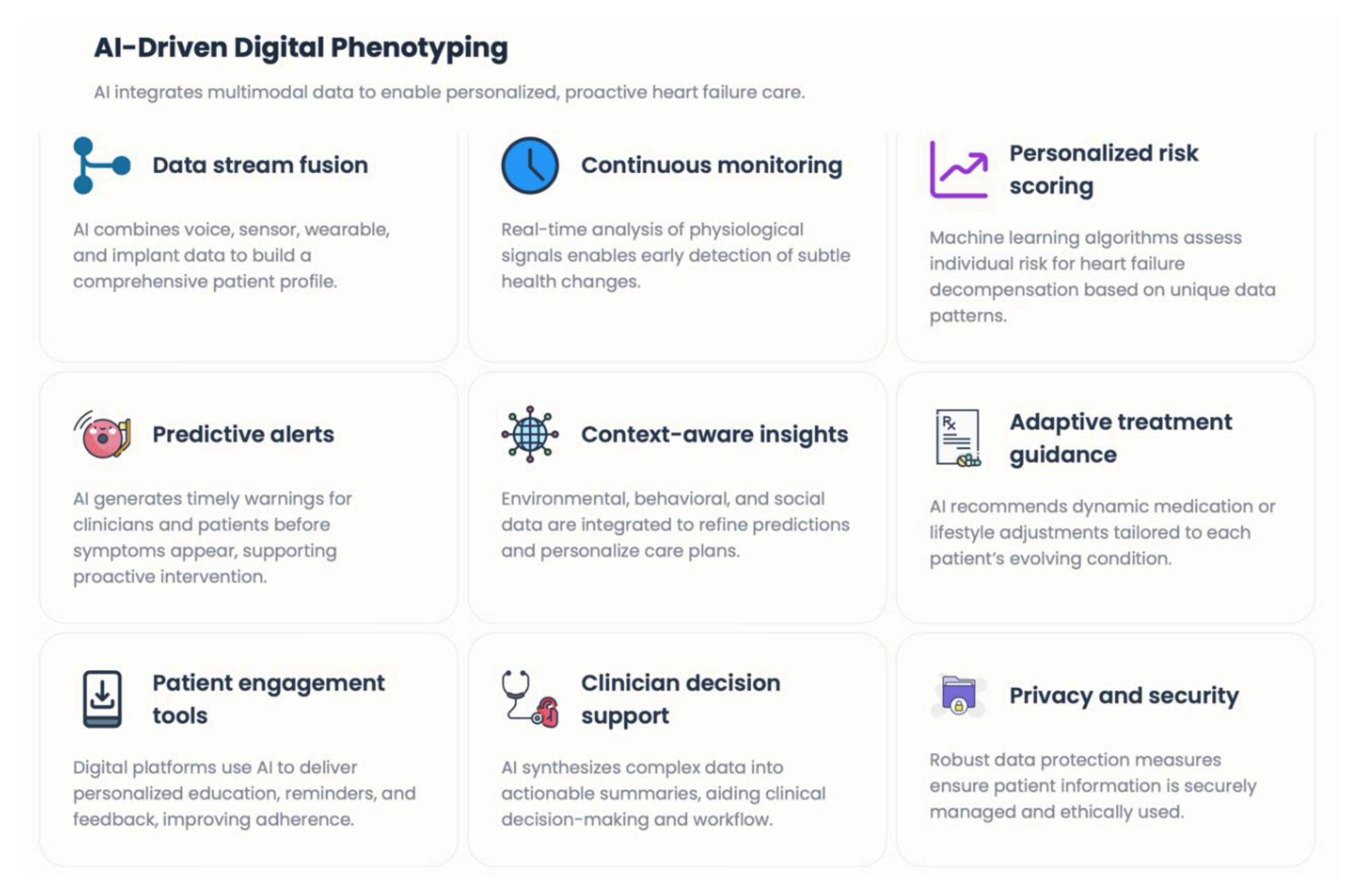

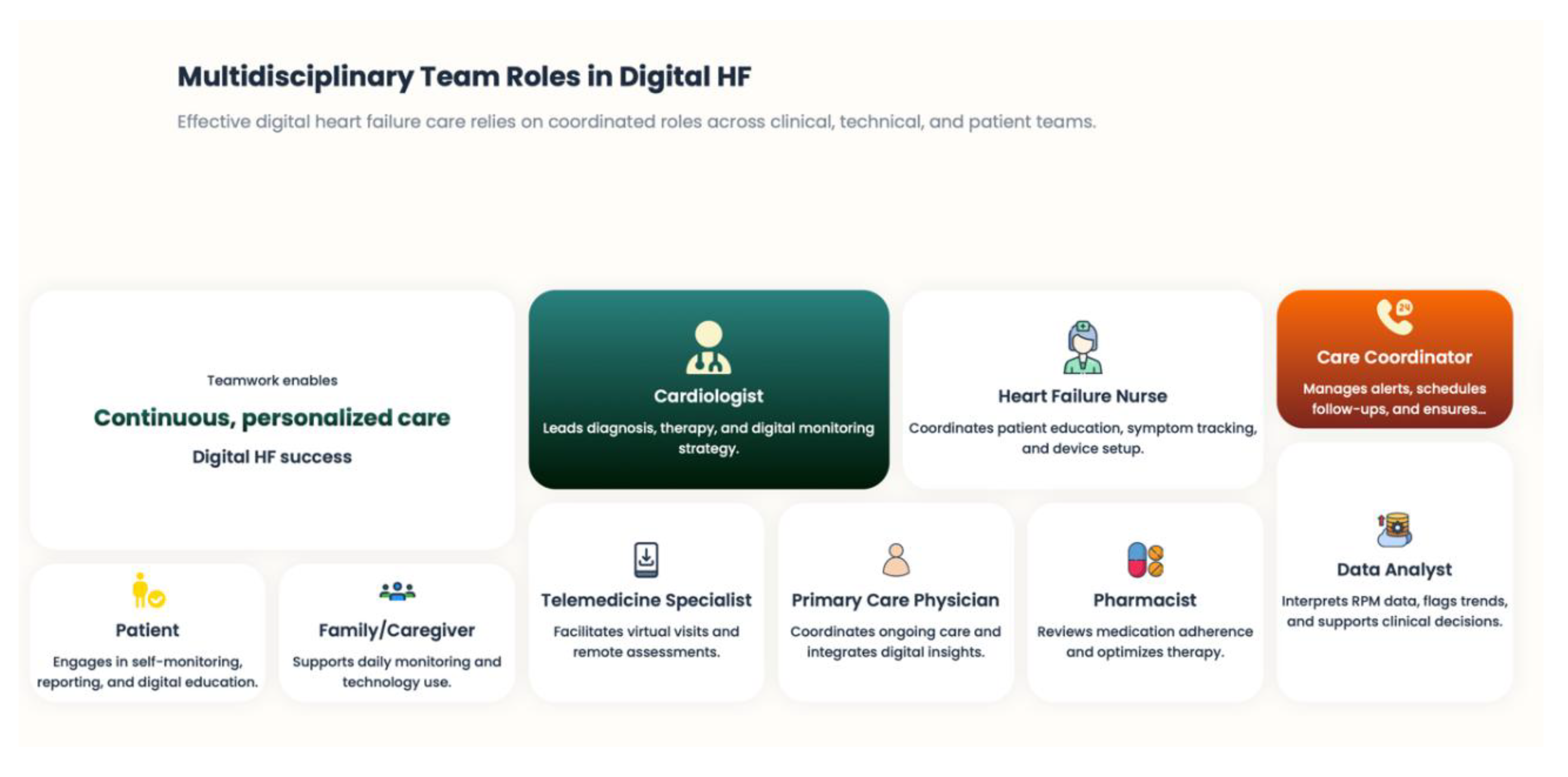

Background: Heart failure (HF) is a progressive, multisystem syndrome characterized by recurrent decompensation, high hospitalization rates, and substantial mortality. Conventional HF management is mainly episodic and often fails to detect worsening conditions in advanced disease. Digital medicine and remote patient monitoring (RPM) hold promise for moving HF care toward earlier detection, proactive action, and personalized care. Methods: We conduct a narrative review to summarize evidence from randomized clinical trials, real-world registries, and emerging digital health technologies regarding the present and future utility of digital medicine in HF care. There is greater emphasis on pathophysiology-based surveillance, personalized care models, and integration into planned health care pathways. Results: Integrated digital interventions, such as implantable hemodynamic monitoring, organized telemedicine programs, or device-based diagnostic technologies, can minimize HF hospitalizations, prolong life, improve quality of life, and optimize resource utilization in health care systems when incorporated into coordinated care. Crucially, trials emphasize that clinical benefit depends not on technology but on a prompt clinical response, multidisciplinary cooperation, and ongoing interaction between the patient and the doctor. New technologies—including voice-based biomarkers, smartphone-derived photoplethysmography, ballistocardiography, and artificial intelligence–driven data integration—may help transition RPM from a hardware-based system to a scalable, “deviceless” approach. Conclusions: Digital medicine is a game-changer for reimagining HF care, involving not only continuous monitoring of physiological changes but also personalized, proactive clinical decision-making. To implement truly patient-centered, predictive HF management in the years to come, technological innovation must be combined with human connection, ethical governance, and health-system readiness.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

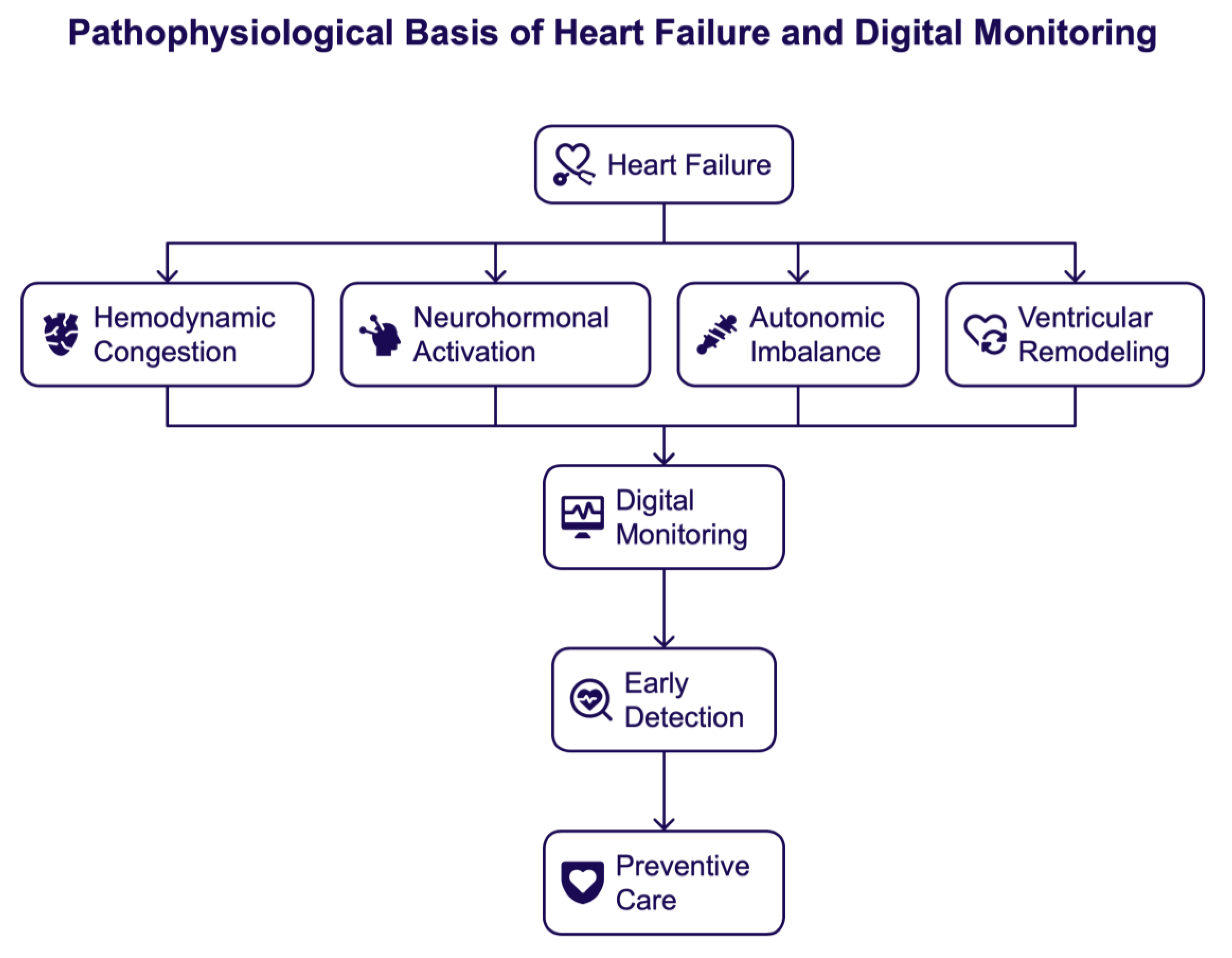

2. The Pathophysiological Basis of Heart Failure Relevant for Digital Monitoring

2.1. Hemodynamic Congestion and Fluid Overload

2.2. Neurohormonal Activation and Disease Progression

2.3. Autonomic Imbalance and Arrhythmogenic Substrate

2.4. Ventricular Remodeling and Progressive Myocardial Dysfunction

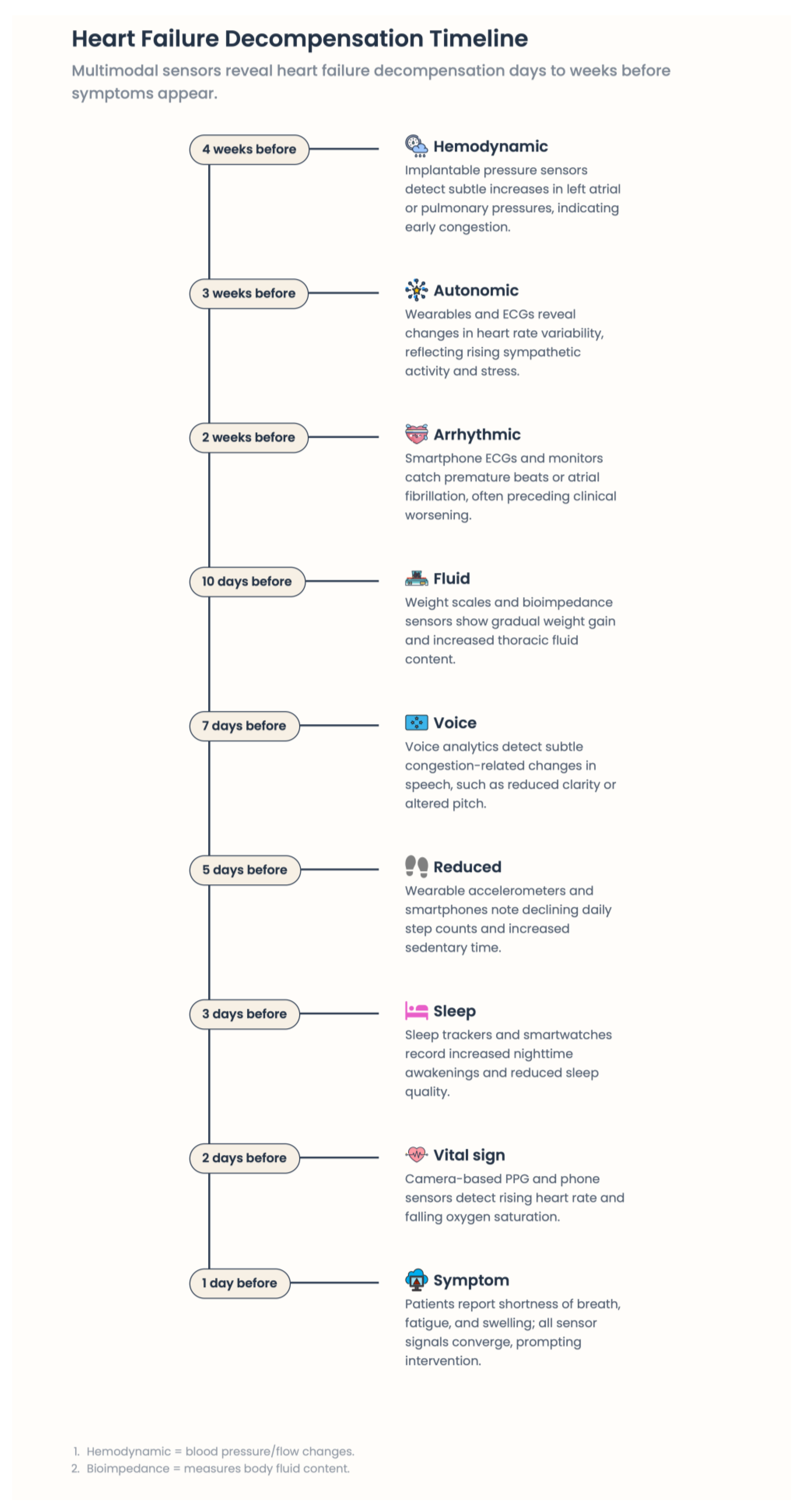

2.5. The Pre-Symptomatic Phase of Decompensation: An Opportunity

2.6. Pathophysiology Underpins Digital Heart Failure Care

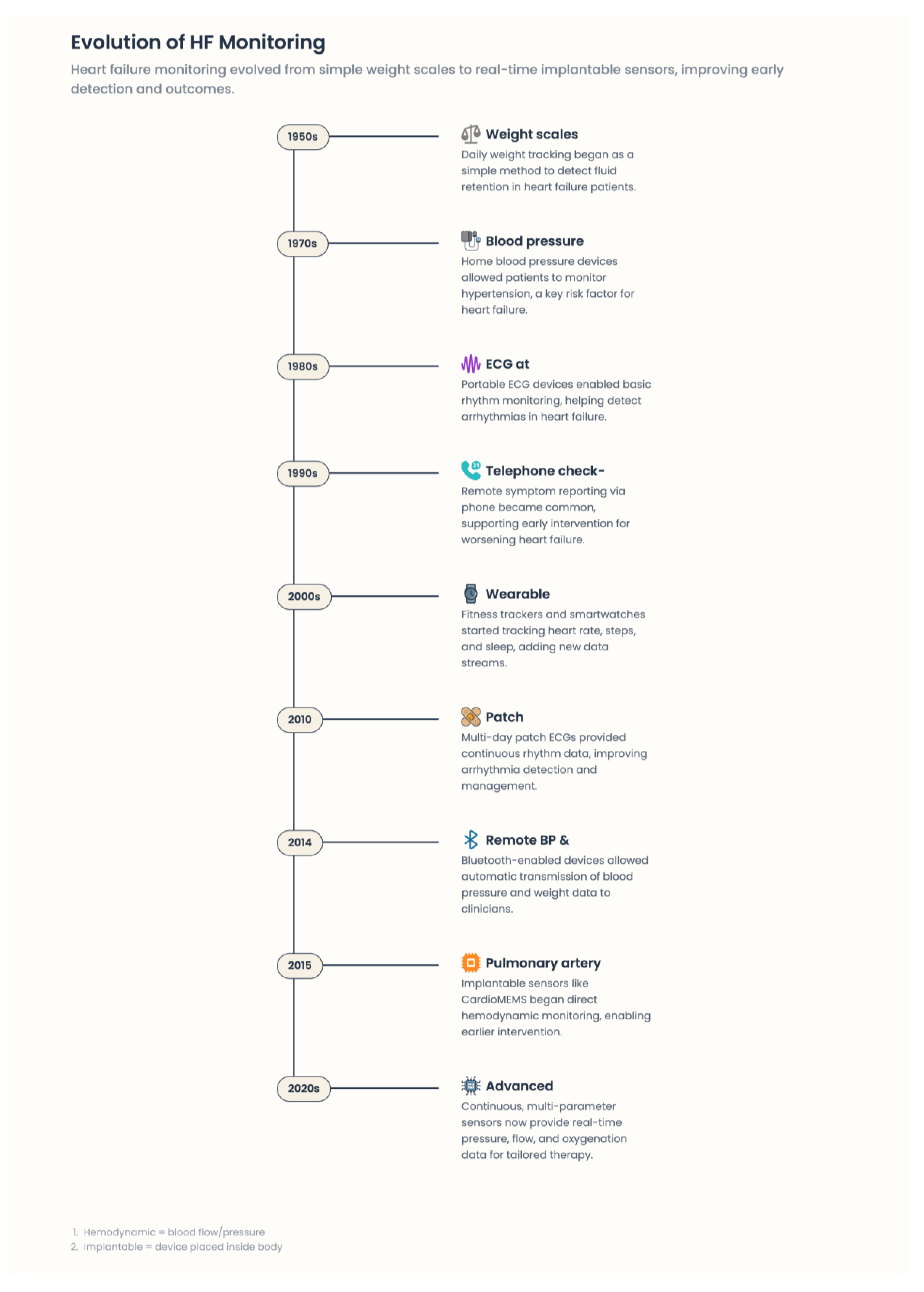

3. Heart Failure: Digital Medicine modalities

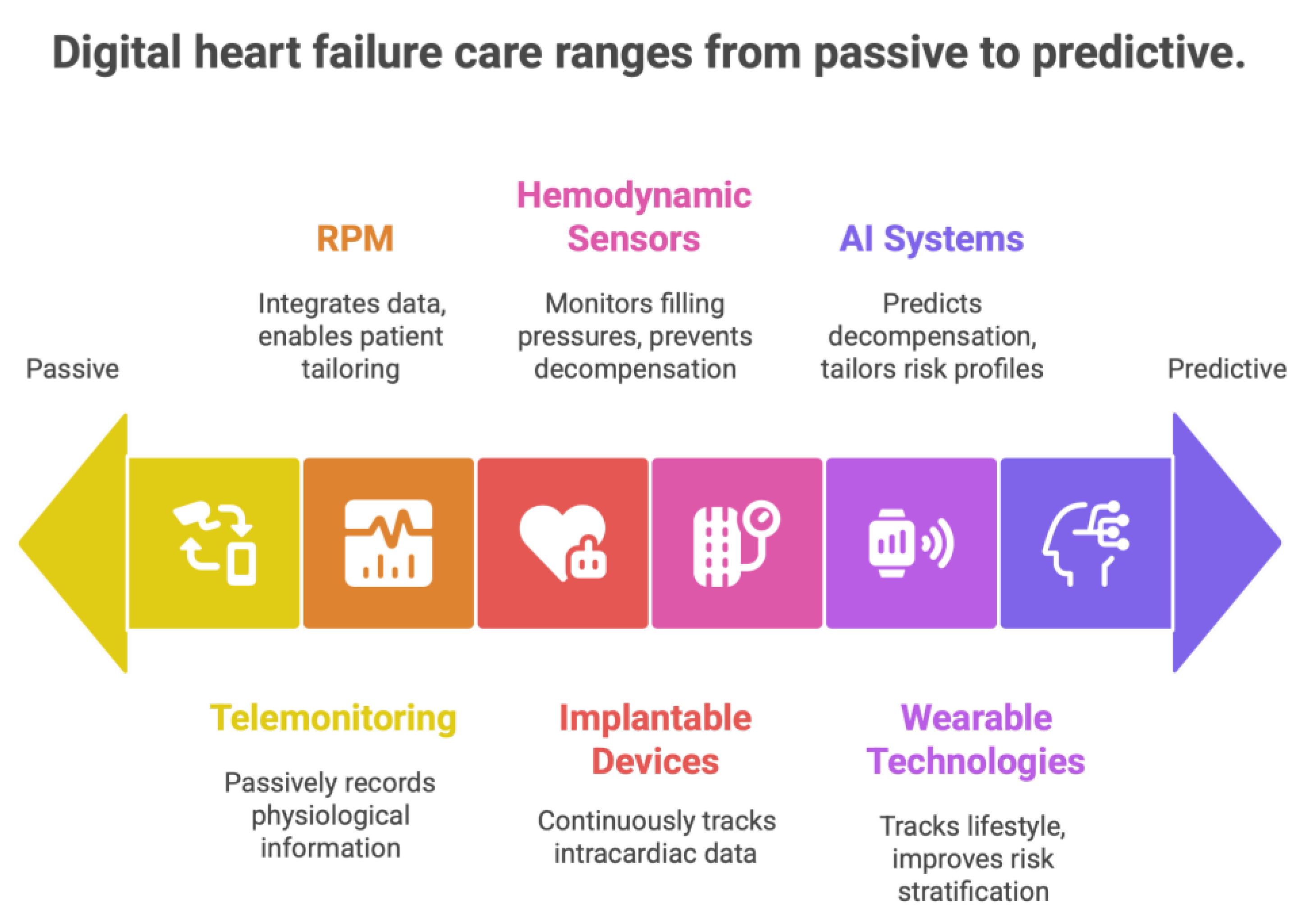

3.1. Remote Patient Monitoring Systems

3.2. Monitoring Based on Implantable Devices

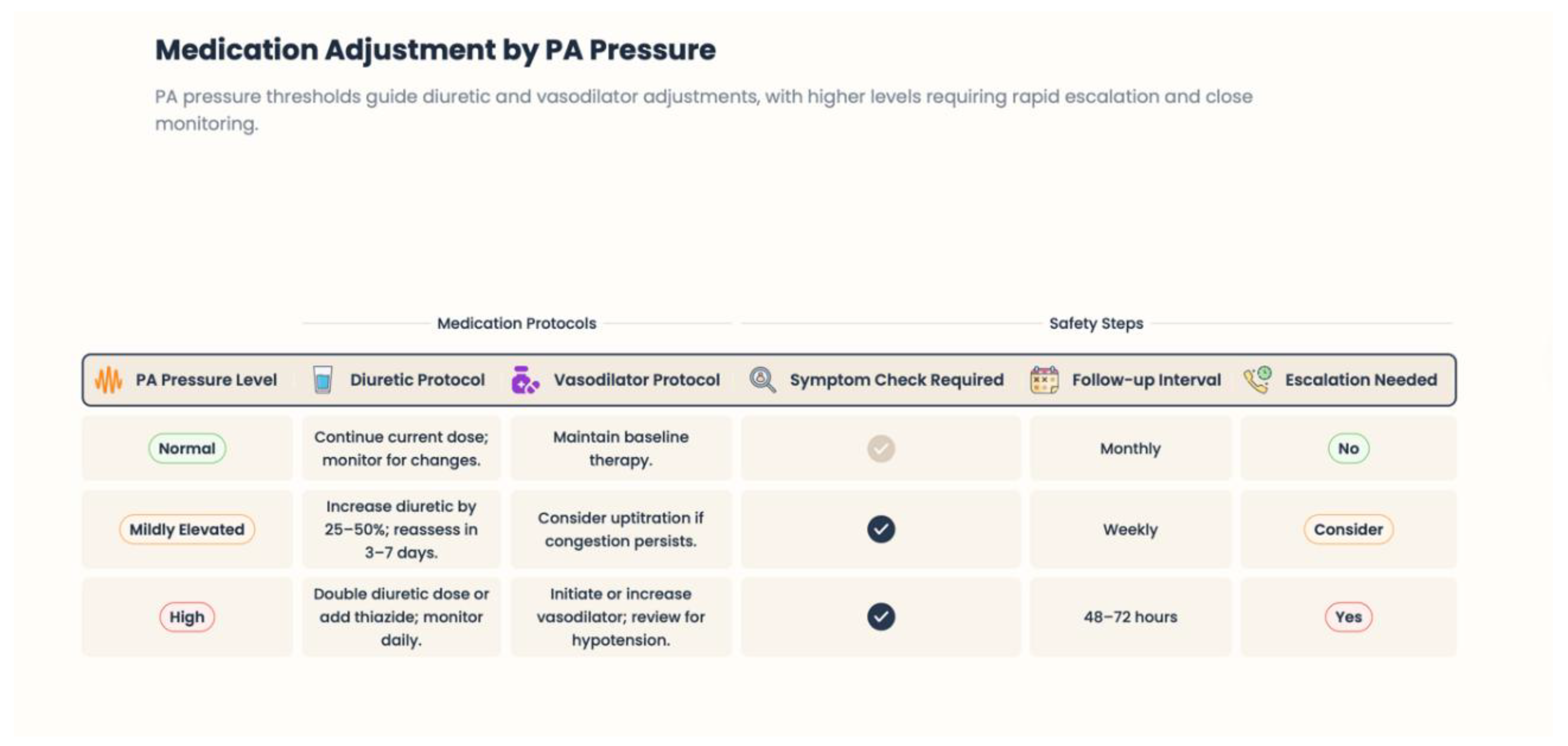

3.3. Hemodynamic Monitoring and Pulmonary Artery Pressure Sensors

3.4. Wearable Technologies and Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the Management of Heart Failure Patients

3.5. Integration of Digital Modalities into Comprehensive Care Models

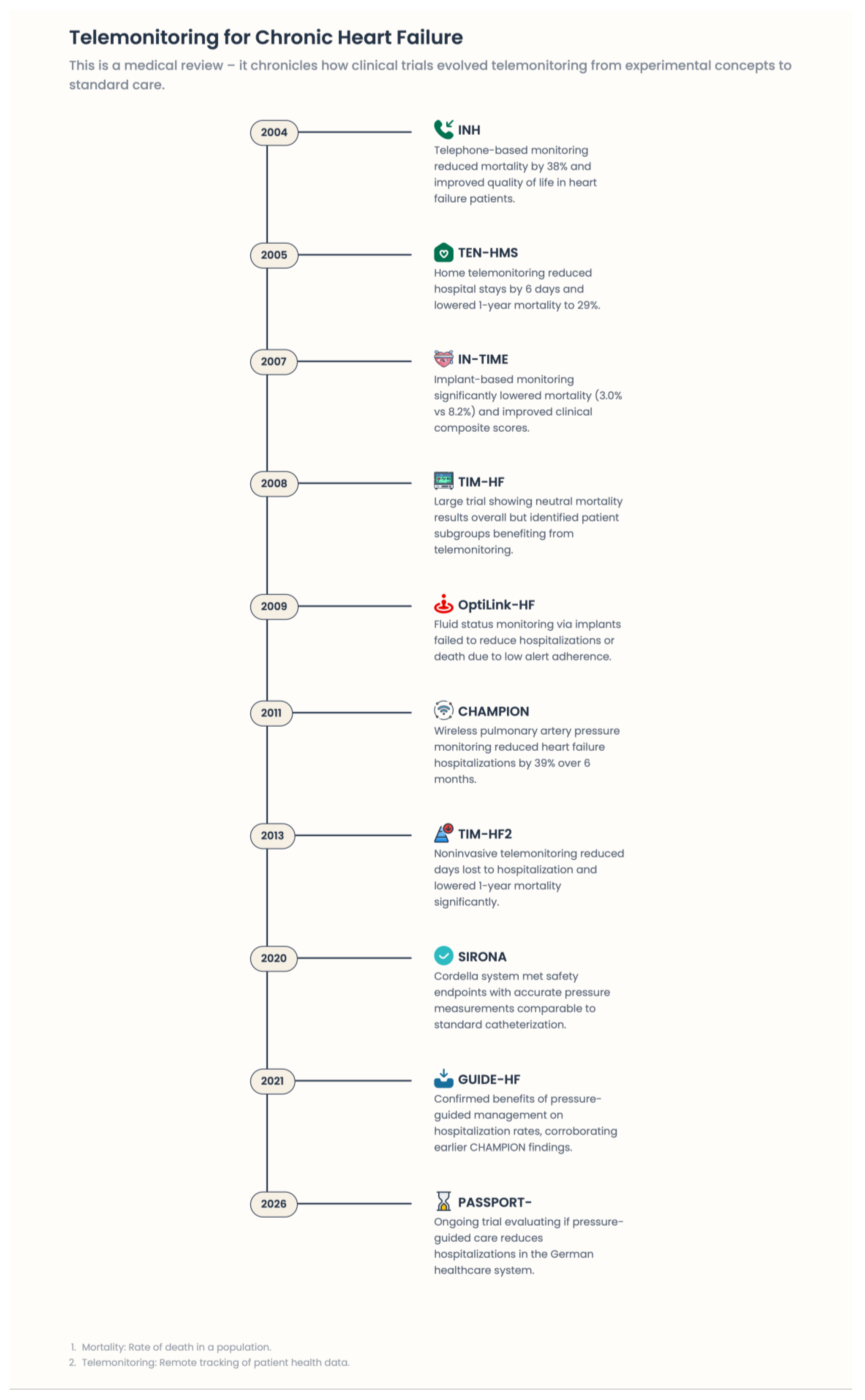

4. Evidence Base: Clinical Trials and Real-World Data—Why Some Digital Strategies Work and Others Fail

4.1. Telemonitoring Trials in Their Early Days: Why Passive Digitalization Had Not Worked

4.2. Implantable Hemodynamic Monitoring: Core Pathophysiology and Areas of Concern

4.3. Structured Telemedical Care: TIM-HF, TIM-HF2

4.4. TELESAT: The Therapeutic Power of the Human Link

4.5. Device-Based Monitoring and Arrhythmia Management

4.6. Practical Evidence: Implications and Health Systems Impact in Practice

4.7. Why Pathophysiology-Informed Digital Care Is the Game Changer

- a)

- Rooted in HF pathophysiology;

- b)

- Embedded in a multidisciplinary care pathway;

- c)

- Supported by well-trained healthcare teams;

- d)

- Based on ongoing patient-provider interaction;

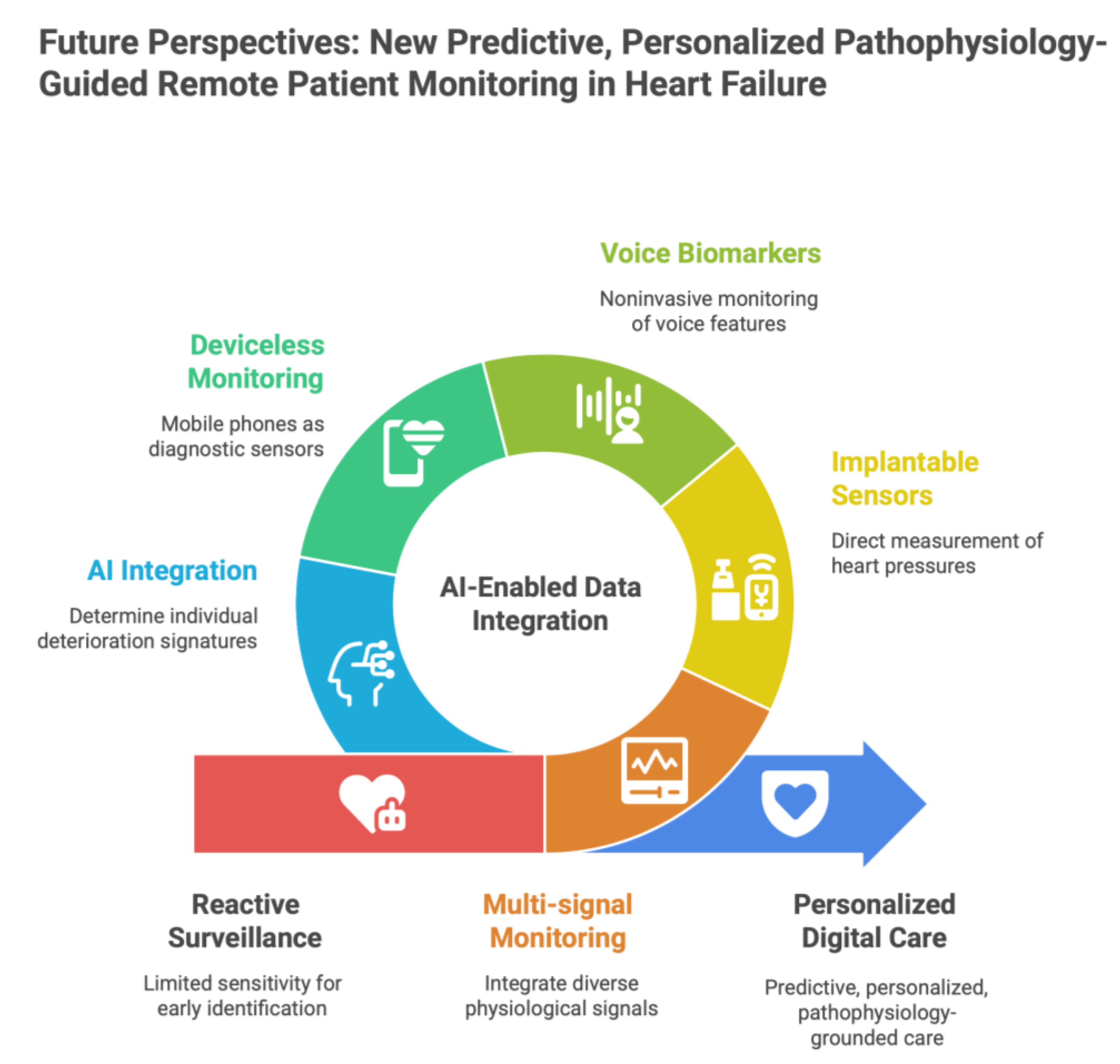

5. Future Perspectives: New Predictive, Personalized Pathophysiology-Guided Remote Patient Monitoring in Heart Failure

5.1. Multi-signal Monitoring to Multimodal Physiological Intelligence

5.2. Implantable and Minimally Invasive Approaches: On Top of The Conventional Sensors

5.3. Voice-Based and Acoustic Digital Biomarkers

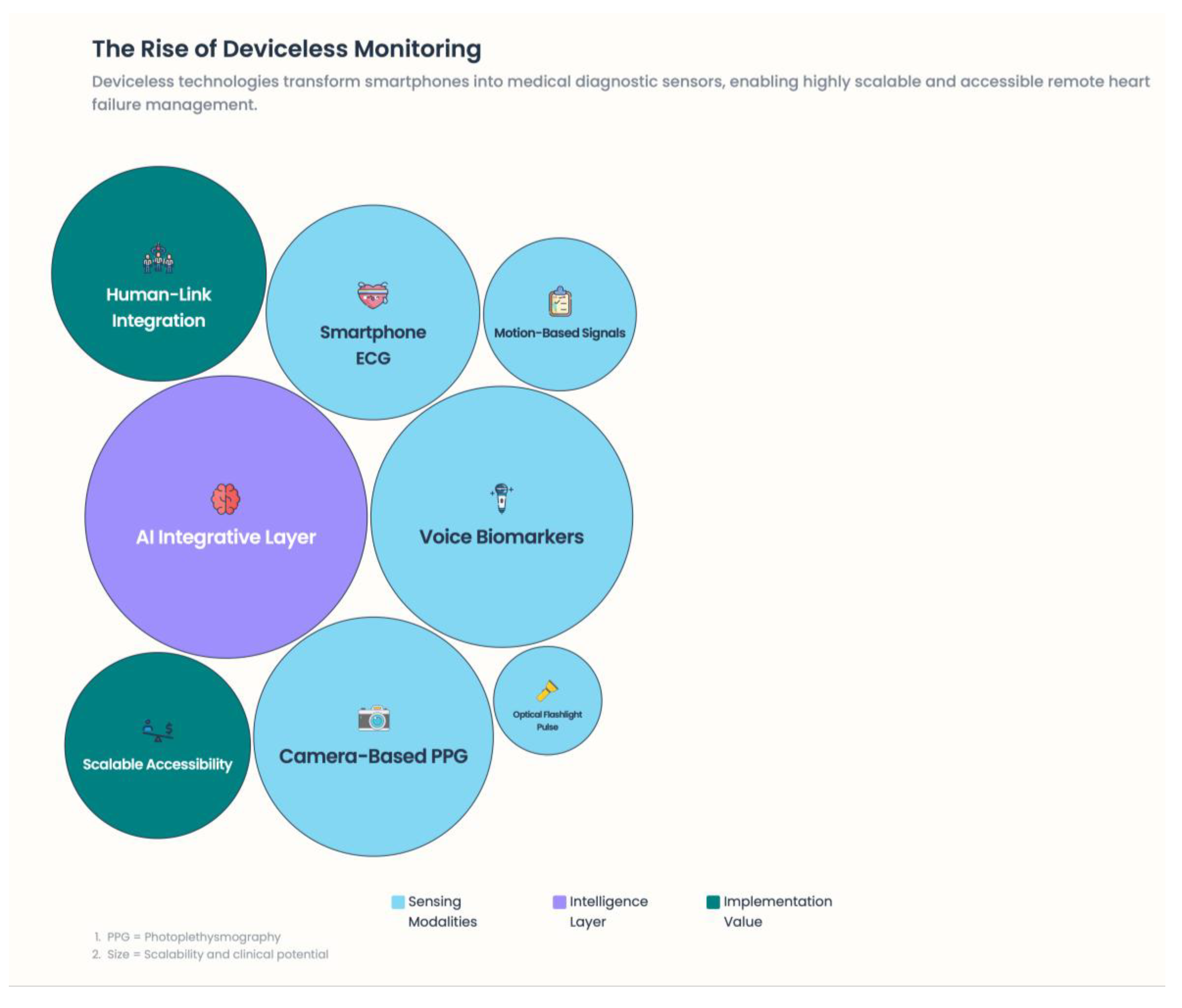

5.4. “Deviceless” Medical Monitoring Using Mobile Phones and Physiological Sensors

5.4.1. Camera-Based Photoplethysmography (PPG)

- Heart rate

- Heart rate variability

- Respiratory rate

- Peripheral perfusion indices

5.4.2. Motion-Based Signals

5.4.3. Measurements Using Optical and Flashlight Devices

5.5. Smartphone-Embedded ECG and Arrhythmia Surveillance

5.6. AI as the Integrative Layer

5.7. Personalized, Relationship-Driven Digital Care

6. Clinical Implications and Implementation in Heart Failure Care Pathways

6.1. An Episodic to Continuous Perspective of Heart Failure Care

6.2. Reconfiguration of the Role of the Multidisciplinary Heart Failure Team

6.3. The Integrated Model Between Levels of Clinical Care

6.4. Patient Engagement and Self-Management as Integral Components of Healthcare

6.5. Contribution to Arrhythmia Surveillance in Heart Failure Pathways

6.6. Health System and Policy Implications

6.7. Key Clinical Takeaways

- Enable earlier intervention throughout the trajectory of HF disease.

- Proactively optimize GDMT.

- Enhance collaboration among care environments.

- Increase patient care and self-management.

- Minimize hospitalizations and healthcare utilization.

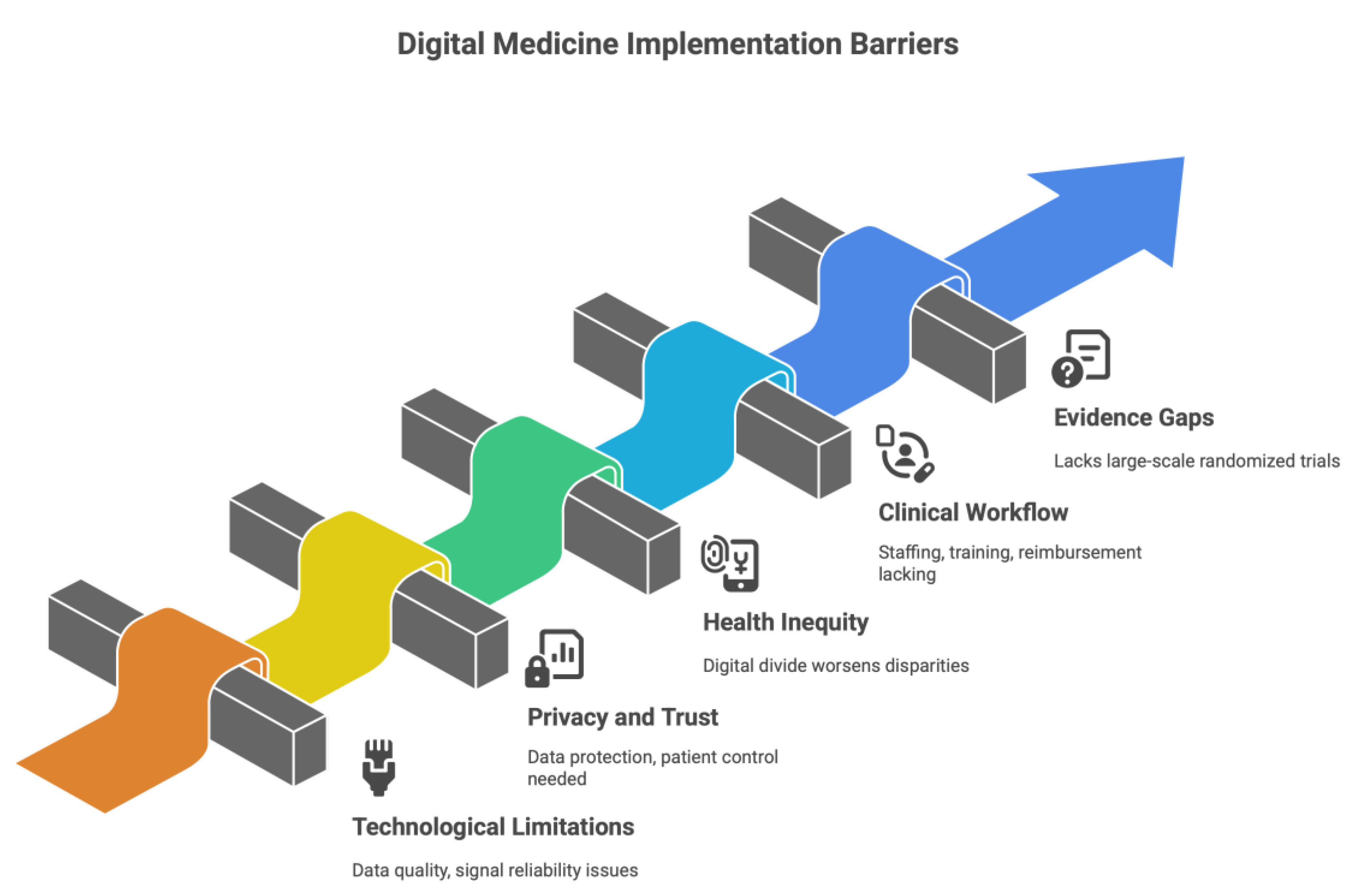

7. Restrictions, Moral Consideration, and Barriers to Implementation

7.1. Limitations Caused by Technological and Information-Oriented

7.2. Issues around Privacy, Autonomy, and Trust

7.3. Health Inequity – The Digital Divide

7.4. Clinical workflow and Staff Challenges

7.5. Evidence Gaps and Regulatory Considerations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDonagh, TA; Metra, M; Adamo, M; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. European Heart Journal. 2021, 42(36), 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarese, G; Lund, LH. Global public health burden of heart failure. Card Fail Rev. 2017, 3(1), 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghiade, M; Vaduganathan, M; Fonarow, GC; Bonow, RO. Rehospitalization for heart failure: problems and perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013, 61(4), 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, AS; Stevenson, LW. Rehospitalization for heart failure: predict or prevent? Circulation. 2012, 126(4), 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunwald, E. Heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2013, 1(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, B; Coats, AJS; Tsutsui, H; Abdelhamid, M; Adamopoulos, S; Albert, N; et al. Universal Definition and Classification of Heart Failure: A Report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society, and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2021, 27(4), 387–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, F; Koehler, K; Deckwart, O; et al. Efficacy of telemedical interventional management in patients with heart failure (TIM-HF2). The Lancet. 2018, 392(10152), 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, AS; Bhimaraj, A; Bharmi, R; et al. Ambulatory hemodynamic monitoring reduces heart failure hospitalizations in “real-world” clinical practice. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017, 69(19), 2357–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, F; Winkler, S; Schieber, M; et al. Impact of remote telemedical management on mortality and hospitalizations in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 2011, 123(17), 1873–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaselli, GF; Mahaffey, KW; Cuker, A. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS scientific statement on precision medicine in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019, 139(24), e843–e876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, WT; Adamson, PB; Bourge, RC; et al. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011, 377(9766), 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindenfeld, J; Zile, MR; Desai, AS; et al. Haemodynamic-guided management of heart failure (GUIDE-HF). Lancet 2021, 398(10304), 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglis, SC; Clark, RA; Dierckx, R; Prieto-Merino, D; Cleland, JGF. Structured telephone support or non-invasive telemonitoring for patients with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, (10), CD007228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, LW; et al. Remote Monitoring for Heart Failure Management at Home. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023, 82(6), 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaah, PA; et al. Non-Invasive Telemonitoring in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Chaudhry, SI; et al. Patterns of weight change preceding hospitalization for heart failure. Circulation 2007, 116(14), 1549–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, AS; et al. Ambulatory hemodynamic monitoring reduces heart failure hospitalizations in “Real-World” Clinical Practice. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2017, 69(19), 2357–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, DL; Bristow, MR. Mechanisms and models in heart failure: the biomechanical model and beyond. Circulation 2005, 111(21), 2837–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, PK; Domitrovich, PP; Huikuri, HV; Kleiger, RE; Cast Investigators. Traditional and nonlinear heart rate variability are each independently associated with mortality after myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005, 16(1), 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaselli, G.F.; Zipes, D.P. What Causes Sudden Death in Heart Failure? Circulation Research 2004, 95, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boriani, G.; Bonini, N.; Vitolo, M.; Mei, D.A.; Imberti, J.F.; Gerra, L.; Romiti, G.F.; Corica, B.; Proietti, M.; Diemberger, I.; Dan, G.-A.; Potpara, T.; Lip, G.Y.H. Asymptomatic vs. Symptomatic Atrial Fibrillation: Clinical Outcomes in Heart Failure Patients. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 119, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severino, P; Maestrini, V; Mariani, MV; et al. Structural and myocardial dysfunction in heart failure beyond ejection fraction. Heart Fail Rev. 2020, 25(1), 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, M.; Ashwath, M.L. Cardiac Imaging in the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E; Randall, EB; Hummel, SL; Cameron, DM; Beard, DA; Carlson, BE. Phenotyping heart failure using model-based analysis and physiology-informed machine learning. J Physiol. 2021, 599(22), 4991–5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njoroge, Joyce N; Teerlink, John R. Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Approaches to Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. Circulation Research 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsabah, M.; Naser, M.A.; Albahri, A.S.; et al. A comprehensive review on key technologies toward smart healthcare systems based on IoT: technical aspects, challenges, and future directions. Artif Intell Rev 2025, 58, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A; Cowie, MR. Digital Health: Implications for Heart Failure Management. Card Fail Rev. Published 2021 May 11. 2021, 7, e08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, LP; Maita, KC; Avila, FR; et al. Benefits and Challenges of Remote Patient Monitoring as Perceived by Health Care Practitioners: A Systematic Review. Perm J 2023, 27(4), 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charkviani, M; Simonetto, DA; Ahrens, DJ; et al. Conceptualization of Remote Patient Monitoring Program for Patients with Complex Medical Illness on Hospital Dismissal. Mayo Clin Proc Digit Health Published 2023 Oct 29. 2023, 1(4), 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, N; Braunschweig, F; Burri, H; et al. Remote monitoring of cardiac implantable electronic devices and disease management. Europace 2023, 25(9), euad233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becher, Jan; et al. Device-based impedance measurement is a useful and accurate tool for direct assessment of intrathoracic fluid accumulation in heart failure. EP Europace 2010, Volume 12(Issue 5), 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masarone, D.; et al. Management of Arrhythmias in Heart Failure. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2017, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseboom, E.; Daniëls, F.; Rienstra, M.; Maass, A.H. Daily Measurements from Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices to Assess Health Status. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaied, AA; Brown, K; Dunlap, S; et al. Implantable Device-Guided Pulmonary Artery Pressure Monitoring Reduces Heart Failure Readmissions. JACC Case Rep. 2025, 30(36), 105713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigore, M; Nicolae, C; Grigore, AM; et al. Contemporary Perspectives on Congestion in Heart Failure: Bridging Classic Signs with Evolving Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategies. Diagnostics (Basel) Published 2025 Apr 24. 2025, 15(9), 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapelios, CJ; Liori, S; Bonios, M; Abraham, WT; Filippatos, G. Effect of pulmonary artery pressure-guided management on outcomes of patients with heart failure outside clinical trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world evidence with the CardioMEMS Heart Failure System. Eur J Heart Fail. 2025, 27(10), 1857–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raval, NY; Valika, A; Adamson, PB; Williams, C; Brett, ME; Costanzo, MR. Pulmonary Artery Pressure-Guided Heart Failure Management Reduces Hospitalizations in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. Circ Heart Fail 2023, 16(5), e009721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B; Huang, Y; Mao, W; Liu, J; Ma, Q. Applications and Prospects of Digital Health Technologies in Cardiovascular Nursing: Smart Devices, Remote Monitoring, and Personalized Care. J Multidiscip Healthc. Published 2025 Oct 2. 2025, 18, 6275–6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, AM; Lindsey, A; Annis, J; et al. Physical Activity, Sleep, and Quality of Life in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Novel Insights From Wearable Devices. Pulm Circ. Published 2025 Apr 16. 2025, 15(2), e70069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Jiménez, D.; López Ruiz, J.L.; Gaitán-Guerrero, J.F.; Espinilla Estévez, M. Understanding Patient Adherence Through Sensor Data: An Integrated Approach to Chronic Disease Management. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, AE; Vrijens, B; Hiligsmann, M. A Digital Innovation for the Personalized Management of Adherence: Analysis of Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. Front Med Technol. Published 2020 Dec 14. 2020, 2, 604183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourse, R; Kayser, L; Maddison, R. Developing Requirements for a Digital Self-Care Intervention for Adults With Heart Failure: Qualitative Workshop Study. J Med Internet Res 2025, 27, e72589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udoy, I.A.; Hassan, O. AI-Driven Technology in Heart Failure Detection and Diagnosis: A Review of the Advancement in Personalized Healthcare. Symmetry 2025, 17, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi-Zoccai, G; D’Ascenzo, F; Giordano, S; et al. Artificial intelligence in cardiology: general perspectives and focus on interventional cardiology. Anatol J Cardiol. 2025, 29(4), 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y; Lehmann, CU; Malin, B. Digital Information Ecosystems in Modern Care Coordination and Patient Care Pathways and the Challenges and Opportunities for AI Solutions. J Med Internet Res. Published 2024 Dec 2. 2024, 26, e60258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baris, R.O.; Tabit, C.E. Heart Failure Readmission Prevention Strategies—A Comparative Review of Medications, Devices, and Other Interventions. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, Sarwat I.; Barton, Barbara; Mattera, Jennifer; Spertus, John; Krumholz, Harlan M. Randomized Trial of Telemonitoring to Improve Heart Failure Outcomes (Tele-HF): Study Design. Journal of Cardiac Failure 2007, Volume 13(Issue 9), Pages 709–714. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1071916407004897. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, MK; Romano, PS; Edgington, S; et al. Effectiveness of Remote Patient Monitoring After Discharge of Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure: The Better Effectiveness After Transition -- Heart Failure (BEAT-HF) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016, 176(3), 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwaah, PA; Olumuyide, E; Farhat, K; et al. Non-Invasive Telemonitoring in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. Medicina (Kaunas) Published 2025 Jul 15. 2025, 61(7), 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, William T.; et al. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2011, Volume 377(Issue 9766), 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugts; Emans, Jasper J.; M E. Remote haemodynamic monitoring of pulmonary artery pressures in patients with chronic heart failure (MONITOR-HF): a randomised clinical trial. The Lancet Volume 401(Issue 10394), 2113–2123. [CrossRef]

- Koehler, F; Winkler, S; Schieber, M; et al. Telemedical Interventional Monitoring in Heart Failure (TIM-HF), a randomized, controlled intervention trial investigating the impact of telemedicine on mortality in ambulatory patients with heart failure: study design. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010, 12(12), 1354–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, F; Koehler, K; Deckwart, O; et al. Telemedical Interventional Management in Heart Failure II (TIM-HF2), a randomised, controlled trial investigating the impact of telemedicine on unplanned cardiovascular hospitalisations and mortality in heart failure patients: study design and description of the intervention. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018, 20(10), 1485–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girerd, N; Barbet, V; Seronde, MF; et al. Association of a remote monitoring programme with all-cause mortality and hospitalizations in patients with heart failure: National-scale, real-world evidence from a 3-year propensity score analysis of the TELESAT-HF study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2025, 27(9), 1658–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindricks, G; Taborsky, M; Glikson, M; et al. Implant-based multiparameter telemonitoring of patients with heart failure (IN-TIME): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014, 384(9943), 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roseboom, E.; Daniëls, F.; Rienstra, M.; Maass, A.H. Daily Measurements from Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices to Assess Health Status. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezimoha, K; Faraj, M; Kanduri Hanumantharayudu, S; et al. The Impact of Remote Patient Monitoring on Clinical Outcomes in Heart Failure Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Cureus Published 2025 Sep 20. 2025, 17(9), e92812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentili, A; Failla, G; Melnyk, A; et al. The cost-effectiveness of digital health interventions: A systematic review of the literature. Front Public Health Published 2022 Aug 11. 2022, 10, 787135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lathauwer, ILJ; Nieuwenhuys, WW; Hafkamp, F; et al. Remote patient monitoring in heart failure: A comprehensive meta-analysis of effective programme components for hospitalization and mortality reduction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2025, 27(9), 1670–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalowitz, EL; Jhund, PS; Psotka, MA; et al. Where’s the Remote? Failure to Report Clinical Workflows in Heart Failure Remote Monitoring Studies. J Card Fail. 2025, 31(9), 1420–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. “Multimodal Integration of Physiological Signals, Clinical Data, and Medical Imaging for ICU Outcome Prediction”. Journal of Computer Technology and Software 2025, 4(8). Available online: https://ashpress.org/index.php/jcts/article/view/206.

- Luque, I.; Gadea, M.; Comas, A.; Becerra-Fajardo, L.; Colás, J.; Ivorra, A. Invasive and Non-Invasive Remote Patient Monitoring Devices for Heart Failure: A Comparative Review of Technical Maturity and Clinical Readiness. Sensors 2025, 25, 6453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, A; Lucka, J; Jajcay, N; et al. A Noninvasive System for Remote Monitoring of Left Ventricular Filling Pressures. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2025, 10(3), 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, N; Escher, A; Ozturk, C; et al. Pre-Clinical Models of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Advancing Knowledge for Device-Based Therapies. Ann Biomed Eng. 2025, 53(11), 2736–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovchinnikov, A.; Potekhina, A.; Filatova, A.; Svirida, O.; Sobolevskaya, M.; Safiullina, A.; Ageev, F. The Prognostic Role of the Left Atrium in Hypertensive Patients with HFpEF: Does Function Matter More than Structure? Life 2025, 15, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauser, M; Kraus, F; Koehler, F; et al. Voice Assessment and Vocal Biomarkers in Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. Circ Heart Fail. 2025, 18(8), e012303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riehle, L; Fouad, M; Hott, M; Heil, E; Lee, C B; Vungarala, S; Johnson, B; Olson, L; Hindricks, G; Hohendanner, F. AI-driven voice analysis for early fluid overload detection in heart failure: preliminary results from the DHZC cohort of the VAMP-HF study. European Heart Journal 2025, Volume 46, Issue Supplement_1, ehaf784.4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binah.ai. Binah.ai Delivers Artificial Intelligence-powered, Non-contact, Video-based Health and Wellness Monitoring Solutions https://www.binah.ai/news/binah-delivers-multiple-solutions/ (access date: 8 January 2026). January.

- FaceHeart. Technologyhttps://faceheart.com/technology.php (access date: 8 January 2026).

- IntelliProve. The face scan that fuels digital health. https://intelliprove.com/product/product-overview.

- Wu, W; Elgendi, M; Fletcher, RR; et al. Detection of heart rate using smartphone gyroscope data: a scoping review. Front Cardiovasc Med. Published. 2023, 10, 1329290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinotti, E.; Centracchio, J.; Parlato, S.; Esposito, D.; Fratini, A.; Bifulco, P.; Andreozzi, E. Accuracy of the Instantaneous Breathing and Heart Rates Estimated by Smartphone Inertial Units. Sensors 2025, 25, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriel, C.; Parker, K. H.; Faisal, A. A. Smartphone as an ultra-low cost medical tricorder for real-time cardiological measurements via ballistocardiography. 2015 IEEE 12th International Conference on Wearable and Implantable Body Sensor Networks (BSN), Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H; Ivanov, K; Wang, Y; Wang, L. Toward a Smartphone Application for Estimation of Pulse Transit Time. Sensors (Basel) Published 2015 Oct 27. 2015, 15(10), 27303–27321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzid, Z; Al-Zaiti, SS; Bond, R; Sejdić, E. Remote and wearable ECG devices with diagnostic abilities in adults: A state-of-the-science scoping review. Heart Rhythm 2022, 19(7), 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetanov, F. Integrating AI Technologies into Remote Monitoring Patient Systems. Eng. Proc. 2024, 70, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potoupni, V; Samaras, A; Papadopoulos, C; et al. Machine-Learning-Driven Phenotyping in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Current Approaches and Future Directions. Medicina (Kaunas) Published 2025 Oct 29. 2025, 61(11), 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, A; Palazzini, M; Trimarchi, G; et al. Heart Failure Management through Telehealth: Expanding Care and Connecting Hearts. J Clin Med. Published. 2024, 13(9), 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnar, DO; Dobies, B; Gudmundsson, EF; et al. Effect of a digital health intervention on outpatients with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. Eur Heart J Digit Health Published 2025 Jun 10. 2025, 6(4), 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laborante, Renzo; et al. Device-based Strategies for Monitoring Congestion and Guideline-directed Therapy in Heart Failure: The Who, When and How of Personalised Care. Cardiac Failure Review 2025, 11, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyne, JJ; Ski, CF; Fitzsimons, D; Amin, H; Hill, L; Thompson, DR. The changing role of patients, and nursing and medical professionals as a result of digitalization of health and heart failure care. J Nurs Manag. 2022, 30(8), 3847–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawesi, S; Rashrash, M; Phalakornkule, K; Carpenter, JS; Jones, JF. The Impact of Information Technology on Patient Engagement and Health Behavior Change: A Systematic Review of the Literature. JMIR Med Inform. Published 2016 Jan 21. 2016, 4(1), e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokri, H; van Baal, P; Rutten-van Mölken, M. The impact of different perspectives on the cost-effectiveness of remote patient monitoring for patients with heart failure in different European countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2025, 26(1), 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Kumar, R.; Panda, B.S.; Kumar, R.; Muften, N.F.; Abass, M.A.; Lozanović, J. Machine Learning-Powered Smart Healthcare Systems in the Era of Big Data: Applications, Diagnostic Insights, Challenges, and Ethical Implications. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, ST. Patient autonomy in the context of digital health. Bioethics 2025, 39(5), 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z; Du, X; Li, J; Hou, R; Sun, J; Marohabutr, T. Factors influencing digital health literacy among older adults: a scoping review. Front Public Health Published 2024 Nov 1. 2024, 12, 1447747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, MA; Pannunzio, V; Kleinsmann, M. The Impact of Perioperative Remote Patient Monitoring on Clinical Staff Workflows: Scoping Review. JMIR Hum Factors 2022, 9(2), e37204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).