1. Introduction

Since 2015, remote monitoring (RM) has been recognized as an integral part of adult patient follow-up after cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) implantation, and class I recommendation was granted by international physician societies [

1,

2]. The significant reduction in notification time from the onset of ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias to their evaluation (including silent arrhythmias), early identification of lead or device malfunction, and monitoring battery status were documented [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Initiating RM within 2–4 weeks of a new CIED implant and performing remote, scheduled follow-up every 3 months for adult patients is recommended [

2]. Daily remote checks of predefined alert events allowing early diagnosis of arrhythmic episodes or device-based events are essential to system functionality. Consequently, the organized and well-structured reaction of the dedicated medical team to incoming alerts translates into earlier clinical response, reduction in inappropriate diagnosis, reduction in hospitalization rate, and improvement of patient prognosis and clinical outcome, as emphasized in the latest Consensus [

2]. One of the critical factors in RM is compliance, defined as the overall enrollment of adult patients with CIED in RM, transmission within 2–4 weeks of new CIED implant, and adherence to recommended follow-up interval guidelines. As emphasized, overall compliance and the final success rate of RM are affected by maintaining continuous connectivity between CIED, transmitter, and manufacturer server [

2]. Several studies revealed that RM based on bedside transmitters achieved suboptimal patient compliance, ranging from 53%–79% [

7,

8]. The potential explanations for low adherence to the scheduled follow-up scheme were transmitter type, geographic localization, socioeconomic status, clinic facilities, patient age, and gender [

9,

10]. These challenges might be overcome by implementing smartphone app-based technology, which communicates with CIED via low-energy Bluetooth (BLE) protocol. Consequently, applying the app-based system presented a reduction in traditional bedside transmitters’ limitations, which led to improved patient engagement, compliance, and the final success rate of completed transmissions, ranging from 92% to 94.6% [

11,

12]. However, further evaluation is needed, especially examining the challenges faced by HF patients with implanted cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D) using new technologies and the medical team conducting their supervision.

The goal of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of RM regarding the connectivity of smartphone app-based solutions, adherence to planned automatic follow-ups, and occurrence of alert-based events.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

A prospective analysis was conducted on HF patients who had CRT-D implanted between November 2020 and April 2024 at five hospitals: 1st and 2nd Department of Cardiology at Poznan University of Medical Science; Department of Cardiology and Electrotherapy at Medical University of Gdansk; Department of Cardiology at Provincial Policlinic Hospital in Torun and Department of Cardiology at Provincial Hospital in Leszno. The indications for CRT were according to guidelines at the time of implantation [

13]. Patient consent was collected. Patients were divided into two arms: implanted with BLE-enabled CRT-D eligible for app-based monitoring (Neutrino NxT HF, Abbott, Plymouth, MN, USA) available in academic centers, and a control group without BLE capability in non-academic ones. Patients were randomly selected at the discretion of implanting physician. The goal was to accomplish 2:1 propensity score match. During the study only one manufacturer offered BLE-enabled devices on Polish market. RM was not reimbursed or academic centers signed no reimbursement agreement with National Health Fund yet. Therefore patients enrolled to RM received remote follow up analysis as a part of a research project. Patients were enrolled in the RM program at discharge, home, or during their first scheduled visit to the CIED outpatient clinic. A combined follow-up protocol was proposed for RM patients: automatic, every 61-days remote follow-up with daily alert checks and standard in-clinic visit every 6-12 months.

For control group patients, every 6-12 months, outpatient clinic follow-ups were conducted. During our study, no delegated medical team was organized due to the lack of reimbursement of RM at that time. The study's primary investigator was supported in each hospital by a cardiologist, trained in the CRT-D implantation technique and follow-up, and regularly evaluated the device transmissions using the internet-accessible website (merlin.net, Abbott). If the loss of communication alert was delivered, a telephone call to the patient was made. During the enrollment procedure, a questionnaire was conducted to verify if patients possessed smartphone. Additionally their level of familiarity with smartphone was measured by five questions regarding: apps installation, text messaging, sending pictures, reading emails and checking weather forecast. Zero or 1 positive response was interpreted as low, 2-3 moderate and 4-5 high level of familiarity. Second questionnaire was used to evaluate patients’ experience in using the app and its four functions: manual transmission, device status, history of transmissions and technical support. Patients enrolled in RM received support in CRT-D to app pairing and training on operating the app, including instructions on manual transmission activation. The quality of daily connections performed at night was stressed to ensure the best adherence and compliance with the scheduled or alert transmissions. The following parameters were included in the analysis: patient demographics, clinical data regarding cardiac diagnosis and indications for CRT-D implantation, RM adherence defined as time to enrollment and the first transmission, the number and regularity of scheduled transmissions, total duration of RM, and detection of alert-based and clinical events. The types of alert-based events were classified into groups with respect to device functioning (lead dysfunction, high pacing output, battery status) and arrhythmic events. Also, the time from RM enrollment to the first alert transmission was determined, and the time to notification, identified as availability on the merlin.net platform, excluding weekends and holidays, was also reported. The patient was called for an additional visit if the justified alert-based transmission was triggered. In the control group, similarly, time from implant to first event was measured, whereas time to notification was calculated from event occurrence to patient appearance in the outpatient clinic for a scheduled visit or in the emergency facility if the event was symptomatic. Information regarding the patient's death was collected from hospital records.

All patients were subjected to a detailed assessment of RM efficacy to measure compliance, which was defined as: the overall enrollment of CRT-D patients in RM, initial RM transmission within 2–4 weeks of enrollment, adherence to the recommended scheduled follow-up interval (61 days).

2.2. Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to express data, including mean, standard deviation, or median with interquartile range (Q1, Q3), range, number of events, frequency of occurrence, and percentages. The Shapiro–Wilk test was conducted to verify normal distribution. The Mann-Whitney and Chi-square with Yates correction test were performed to compare unpaired groups. All statistical analyses were performed in Tibco Statistica software version 13 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, US). A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

3. Results

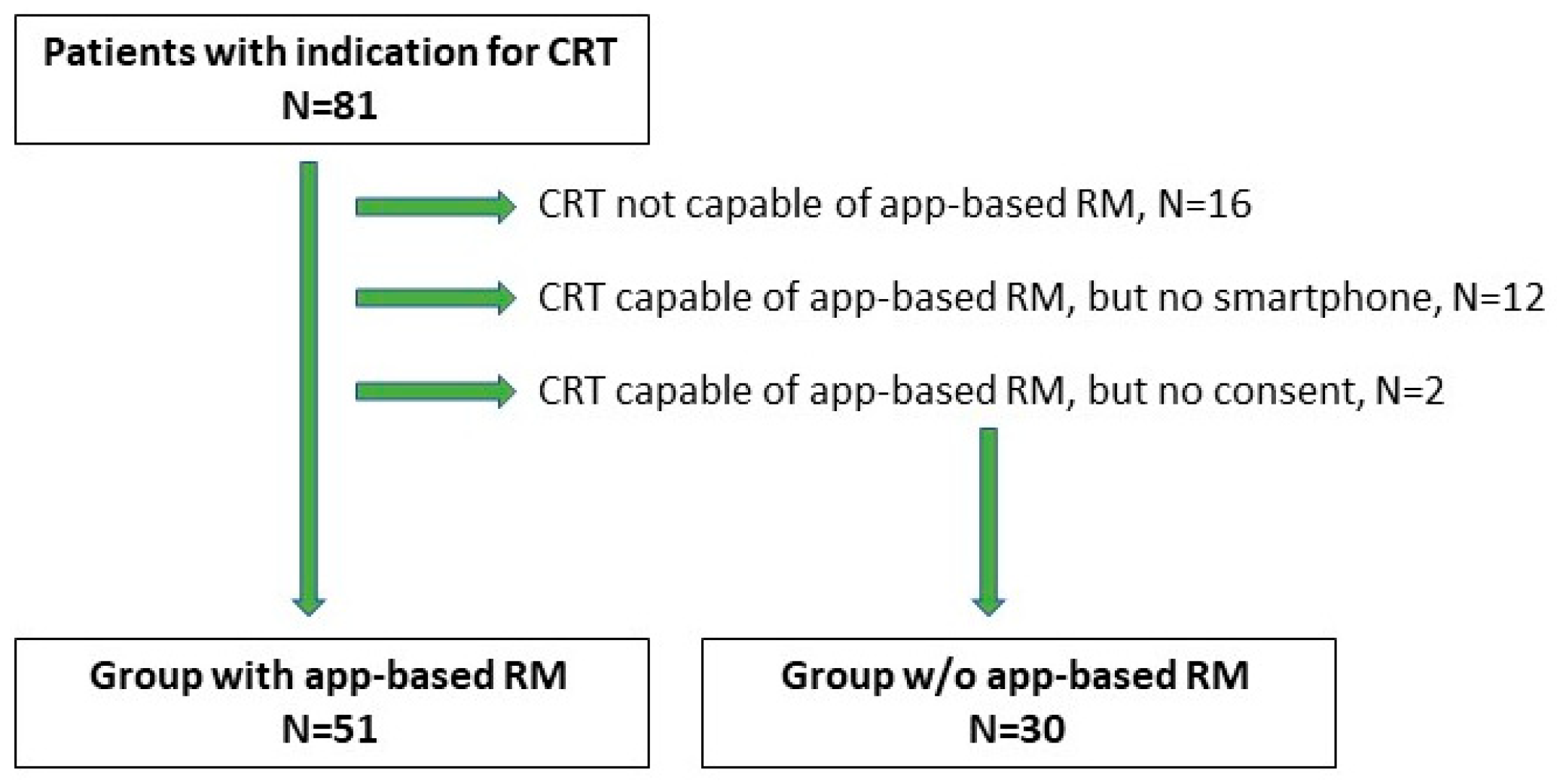

A total of 81 patients were included in our study (74 males and 7 females). The median (Q1, Q3) patient age at implantation was 69.0 (60, 74) years. Baseline patients’ characteristics are available in

Table 1. The group of 65 patients (80.2%) received CRT-D with app-based RM functionality, and 16 patients (19.8%) without. In the first group, 12 patients had no smartphone, and 2 patients did not provide consent, resulting in their transfer to the control group. Thus, the RM arm consisted of 51 patients, while 30 patients were in the control group (

Figure 1). Among 51 patients in RM arm 11 had decided to purchase the smartphone to be eligible for active monitoring.

Patients were followed up remotely over a median period of 12 (5, 24) months. The control group was observed in the outpatient clinic over a median period of 27 (24, 30) months. During the follow-up, no patient deaths were recorded in the RM group and 2 patient deaths in the mechanism of HF progression in the control group. No statistical significance was shown (p=0.260), and no deaths were related to device dysfunction (

Table 2).

3.1. Compliance with App-Based RM

The median (Q1, Q3) time from CRT-D implant to remote monitoring enrollment was 1 day (1, 7). There were 36 patients (70.6%) with successfully paired app and activated monitoring before discharge. The remaining patients (29.4%) were enrolled in RM via a telephone call, with their family assistance while staying at home, except one patient was paired at an outpatient clinic. The main reasons for the delay were: the lack of adequate smartphones followed by intentional purchase, insufficient Internet coverage at the hospital, or deficient rights of the user’s phone.

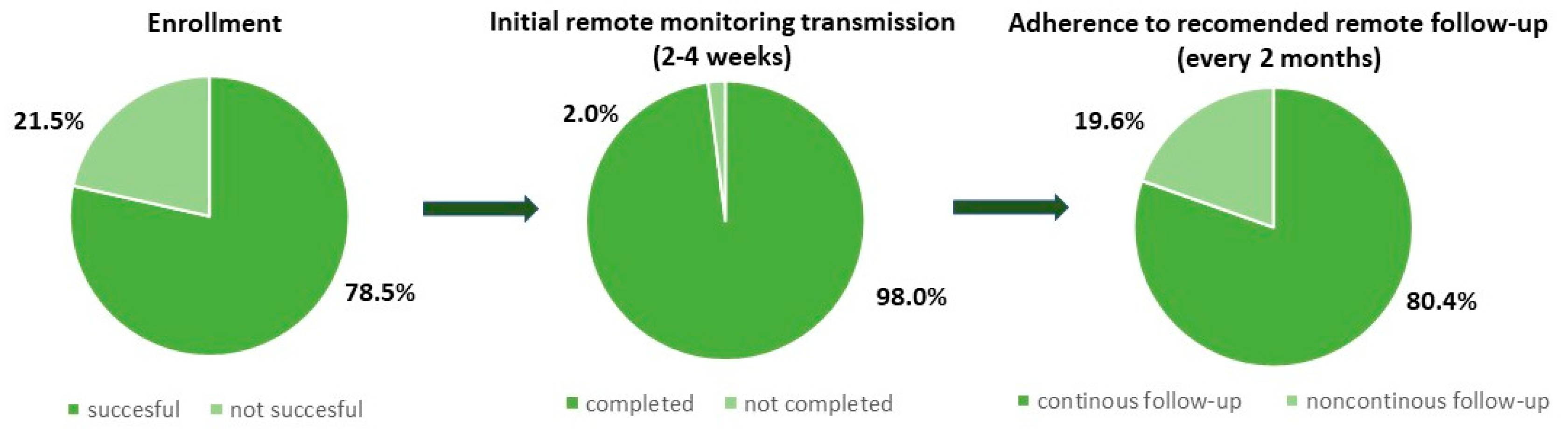

Out of 65 patients who received CRT-D capable of app-based RM, 51 patients (78.5%) were successfully enrolled in the RM system. Twelve patients who had no smartphone nor intention to upgrade and 2 others who did not provide consent were transferred to the control group. The most common causes of RM ineligibility were socioeconomic status and concomitant, age-related diseases such as dementia, stroke, and eye diseases. In the RM arm, 50 patients (98.0%) had their first scheduled follow-up successfully sent. The group of 41 patients (80.4%) were continuously monitored during the observation, and all scheduled transmissions were delivered on time (

Figure 2).

Further analysis of recruitment questionnaire demonstrated that all patients who purchased the smartphone fulfilled the criteria of being continuously monitored. Whereas among group of 19.6% patients with missed scheduled transmissions: 3 patients possessed low, 3 moderate and 4 high level of familiarity with smartphone. In this group 6 out of 10 patients expressed no experience in app installation. Patients with mean age of 81.0 presented low familiarity with required technology. Evaluation of patient’s app experience questionnaire revealed that 84.0% of patients who had activated app and had their first scheduled follow-up successfully sent, used mainly two out of four app functionalities as: transmissions history and device status. Our data did not report excessive use of manual transmission feature. Out of 22 patients who sent intentional transmission: 4 executed it more than 5 times, 1 prompted by medical team and 17 during the first month from enrollment.

Analysis also exposed accidental BLE disconnection or turning off the RM app as the most common cause of decreased connectivity. A group of RM patients contacted us directly and asked for assistance in repairing the app while changing or upgrading their phone, but events were solved ad hoc and not recorded, therefore data is incomplete.

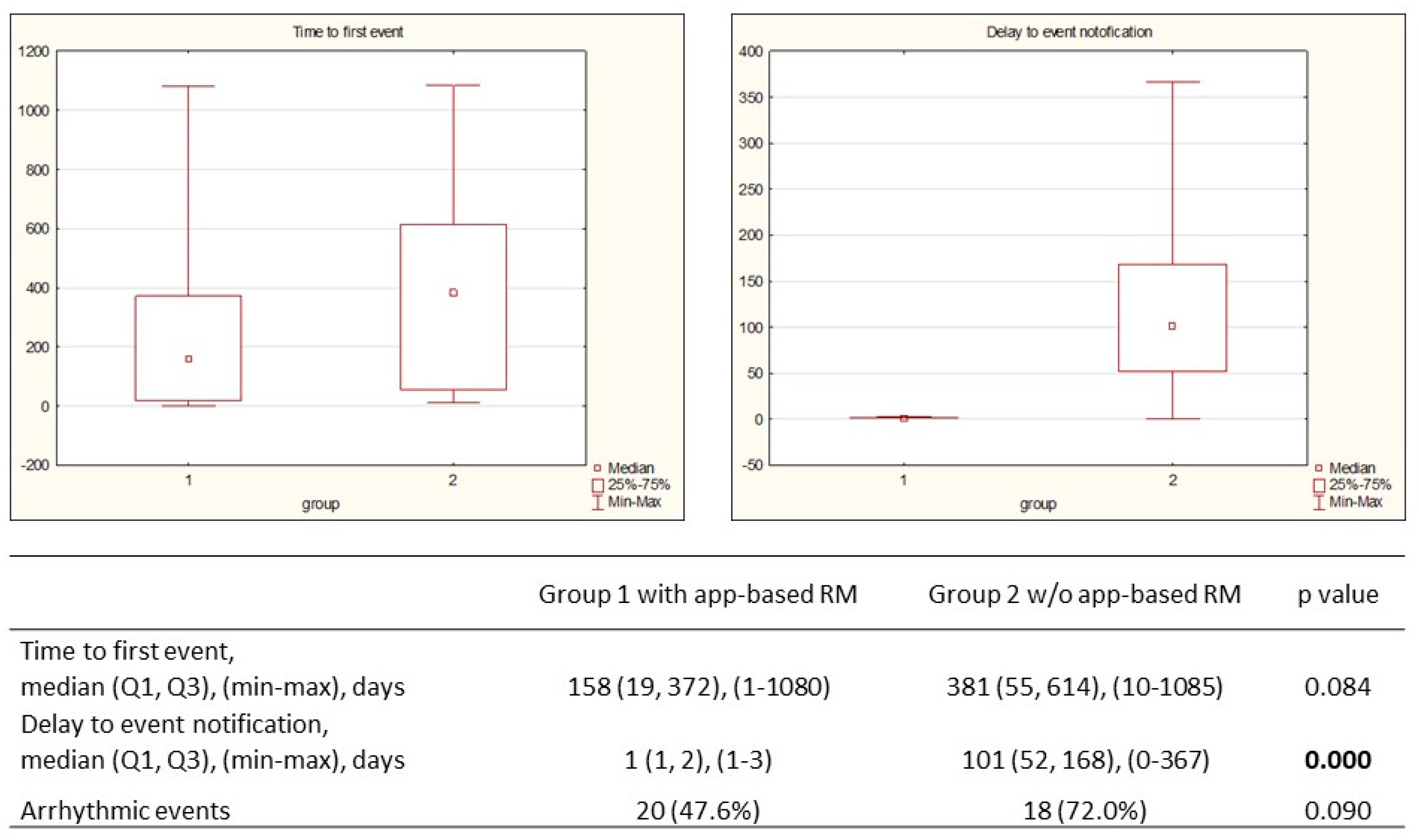

3.2. RM Alert-Based Transmissions vs Control Group

In the app-based RM group, 42 events were observed in 25 patients (49.0%): 88.1% were appropriately diagnosed, followed by justified alert transmission, and 11.9% with false positive notification. The median (Q1, Q3) time to the first transmission was 158 (19, 372) days, and the median time to notification was 1 (1, 2) day. Appropriate alert-based events were classified into two groups: related to arrhythmic events and device functioning, respectively 20 and 22 events (

Table 3).

Similar analyses were conducted for the control group with respect to arrhythmic and device functioning events (

Table 4). The median time to the first event was 381 (55, 614) days, and the median notification delay was 101 (52, 168) days. Although there was a difference in first event occurrence in both groups, no statistical significance was met (p=0.084). A shorter median period to notification in the app-based RM group was noted: 1 day vs 101 days (p=0.0001) (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

In this first Polish real-world, prospective, multicenter study on the efficacy of smartphone app-based RM in HF patients with CRT-Ds, we showed a high level of connectivity as evidenced by good compliance with timely initial transmission (98.0%) and adherence to scheduled remote follow-ups (80.4%). According to the guidelines, the RM should be regarded as a standard of care in HF patients with CIEDs. The registration and initial RM transmission should be performed within 2–4 weeks from implant or device exchange, followed by scheduled remote follow-ups every 3 months and every 12 months for outpatient clinic visits [

2]. Altogether, in our study, we met the requirements of swift time to activate RM, but the patient's enrollment outcome was suboptimal. The 78.5% success rate was mainly influenced by socioeconomic status and concomitant diseases, which resulted in a lack of smartphone to download monitoring app and a lack of understanding of the clinical benefits of RM. Similar conclusions were recently presented from 10 Italian hospitals and 495 patients (67 ± 13 years), where 84% had access to smartphones, 85% were willing to use the HF monitoring app, but only 63% downloaded the app [

14]. It shows that the challenges we encountered during patient enrollment to RM are comparable in European Union region. An important role in the high enrollment ratio is not only the medical team but also family assistance in the patient's app with the CIED pairing process. In our group, 29.4% of patients executed pairing at home with family support. It shows that this process could be performed out of the clinic, possibly with phone support. During the study, we noticed the growing patient awareness of RM advantages, mainly related to reimbursement introduced in mid-2023 and broadly covered by media. This resulted in 11 patients purchasing a smartphone to use beneficial app-based RM. At the same time, technological headway makes smartphones more common among seniors, and current smartphone users will become older; therefore, the challenges with suboptimal eligibility will gradually decline. The pace of technology adoption can be geography- and socioeconomics-related. The recent study presented on a group exceeding 18,000 US patients demonstrated an enrollment level of 94.4% in the app-based group and 85.0% in the bedside transmitters group [

15]. The remaining group of technologically excluded patients should be offered different solutions for RM, such as mobile transmitters or traditional bedside transmitters, as provided by manufacturers. However, the disadvantages of immobile solutions should be taken into consideration. In our previous study with pediatric patients with implanted pacemakers and bedside transmitters, the enrollment success rate was 100.0%, as each patient received a paired transmitter at discharge or in an outpatient clinic. Unfortunately, the adherence was suboptimal, especially during the holiday season, when 34.8% of patients missed scheduled transmissions [

16].

In our study, 98.0% of patients had the first scheduled follow-up successfully sent, and 80.4% of patients followed continuous surveillance without losing scheduled transmissions, which was planned every 61 days. It reveals that smart and mobile technologies solve connectivity challenges in RM, primarily related to bedside systems. These results are in concordance with recently published data presenting adherence in app-based solutions in a range of 92.0% - 94.6% [

11,

12,

15].

Acknowledging the patient experience of using an app is crucial for final compliance. We noticed increased patient engagement in the therapy process via app-built functionality. Patients' experience evaluation revealed that scheduled transmission history and battery status were the most frequently and intentionally used app features. Furthermore no excessive use of manual transmission feature creating work overload for medical team was observed among monitored patients. Patients also contacted research team members for support in maintaining and continuing RM when their smartphone was upgraded, and the re-pairing security code was lost. It demonstrates patients' perception of safety and their understanding of continuous RM for long-term clinical outcomes. Similar insights into the patient experience emerge from recent studies [

12,

15,

17,

18].

Alert-Based Transmissions

Remote monitoring is recommended for early detection of arrhythmic events, especially asymptomatic ones, and device and lead dysfunction [

3]. Our evaluation presented 88.1% appropriately diagnosed events in the app-based RM group with a median time of 158 (19, 372) days. The median time to event in the control group was twice as long (158 vs 381). In our opinion, the presented difference (statistically insignificant) may result from a limited number of the study group and a mismatch in the percentage of ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathies of baseline patients characteristics. However, this ischemic substrate variance does not influence the time from event occurrence to medical team notification, which is directly related to patients’ monitoring method. Our findings revealed a median delay in notification of 1 (1, 2) day in the app-based RM group and 101 (52, 168) days in the control group. The observed proportions are in accordance with the results of previously published The Connect Trial (4.6 vs. 22 days) and the Evolvo Study (1.4 vs. 24.8 days), respectively [

5,

19]. As the time to notification in our study in RM arm is even improved, it implicates that app-based technology may offer superior efficacy to bedside transmitters in rapid detection of alert-based events. Other reports show that app-based technology provides better connectivity than bedside transmitters [

11,

12,

15] mainly due to their lower mobility, which may pose a risk of decreased success rate.

However in respect to time of delay to notification, the meta-analysis conducted by Parthiban et al., presented significant mean difference in days to clinical decision/event detection of 27.1 days [

20]. The difference presented in our research is larger and may result from limited study population or lack of sufficient data regarding medical decisions performed out of implanting center. Nevertheless the main study goal was to evaluate efficacy of app-based RM solution as alternative to traditional bedside system, not to conventional in-office follow up. Superiority of RM has been well analyzed and is reflected in the 2023 HRS/EHRA/APHRS/LAHRS expert consensus [

2].

The improved patient engagement due to available smartphone-based technologies and enhanced communication capabilities between the patient and the medical team were presented recently in case report. Both, swift diagnosis of silent AF and confirmation of terminated VF via manual transmission followed by hospital admission were described [

21].

5. Limitations

The technology examined in our study was commercially introduced in the European Union in November 2020. Throughout the entire period of our research only one manufacturer commercially offered BLE-enabled CRT-Ds in Poland, therefore analysis could not be extended to other devices in respect to RM arm. Furthermore RM was not reimbursed for most of our study period. Therefore BLE-enabled CRT-Ds were implanted only in academic centers and patients enrolled to RM received remote follow up analysis as a part of a research project not from a dedicated hospital unit. Although random patient selection was conducted at the discretion of implanting physician, we cannot completely rule out selection bias. However, as patient selection was carried out in accordance with the standard hospital regime and their characteristics were similar to real-world registries on the HF population with CIED [

22,

23], we believe that selection bias was limited.

6. Conclusions

Our real-world, prospective, multicenter study showed a high level of connectivity manifested by good compliance with timely initial transmission (98.0%) and adherence to scheduled remote follow-ups (80.4%). Patient enrollment eligibility was a major challenge due to the limited accessibility of smartphones in the population, but it will likely improve as technology becomes more widespread. App-based RM demonstrated an ability to provide swift and accurate notification of alert-triggered events and patient-initiated transmissions in emergencies, regardless of location.

Our findings are in concordance with previously published results for CIEDs and provide broader insight for HF patients monitored via smartphone app, indicating key areas to be improved.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K. and B.R. and M.P. and A.B.; methodology, D.K. and B.R. and M.P.; investigation, D.K. and A.K.-S. and M.P. and A.B. and G.S. and E.W. and M.K. and M.P; writing—original draft preparation, D.K. and M.P.; writing—review and editing, B.R. and P.M.; supervision, B.R. and P.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received funding from Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, grant number DWD/4/56/2020

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Poznan University of Medical Sciences (protocol code 805/20 on 4 November 2020)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The research has been conducted as part of PhD thesis at Doctoral School in Poznan University of Medical Science and is portion of large implementing doctoral project supported by grant of Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Conflicts of Interest

D.K.—Abbott employment. Other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Slotwiner, D.; Varma, N.; Akar, J.G.; et al. HRS Expert Consensus Statement on remote interrogation and monitoring for cardiovascular implantable electronic devices. Heart Rhythm. 2015, 12, e69–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrick, A.M.; Raj, S.R.; Deneke, T.; et al. 2023 HRS/EHRA/APHRS/LAHRS Expert Consensus Statement on Practical Management of the Remote Device Clinic. Europace. 2023, 25, euad123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.S.L.; Timmermans, I.; Versteeg, H.; et al. Effect of remote monitoring on clinical outcomes in European heart failure patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: secondary results of the REMOTE-CIED randomized trial. Europace. 2022, 24, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, N.; Love, C.J.; Michalski, J.; et al. TRUST Investigators. Alert-based ICD follow-up: A model of digitally driven remote patient monitoring. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021, 7, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crossley, G.H.; Boyle, A.; Vitense, H.; et al. The CONNECT (Clinical Evaluation of Remote Notification to Reduce Time to Clinical Decision) trial: the value of wireless remote monitoring with automatic clinician alerts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011, 57, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempa, M.; Sławiński, G.; Zieleniewicz, P.; et al. Implementation of remote monitoring in patients implanted with T-ICD and S-ICD involved in a recall campaign: An excellent tool with insufficient availability. Kardiol Pol. 2023, 81, 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld, L.E.; Patel, A.S.; Ajmani, V.B.; et al. Compliance with remote monitoring of ICDS/CRTDS in a real-world population. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014, 37, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, N.; Piccini, J.P.; Snell, J.; et al. The relationship between level of adherence to automatic wireless remote monitoring and survival in pacemaker and defibrillator patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015, 65, 2601–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantini, N.; Borne, R.T.; Varosy, P.D.; et al. Use of cell phone adapters is associated with reduction in disparities in remote monitoring of cardiac implantable electronic devices. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2021, 60, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theuns, D.A.; Radhoe, S.P.; Brugts, J.J. Remote monitoring of heart failure in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: Current status and future needs. Sensors (Basel). 2021, 21, 3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarakji, K.G.; Zaidi, A.M.; Zweibel, S.L.; et al. Performance of first pacemaker to use smart device app for remote monitoring. Heart Rhythm. O2 2021, 2, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilz, R.; Shaik, N.; Piorkowski et, a.l. Real-world Adoption of Smartphone-based Remote Monitoring Using the Confirm Rx™ Insertable Cardiac Monitor. J. Innov. Card. Rhythm. Manag. 2021, 12, 4613–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priori, S.G.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Mazzanti, A.; et al. Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Europace. 2015, 17, 1601–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziacchi, M.; Molon, G.; Giudici, V.; et al. Integration of a Smartphone HF-Dedicated App in the Remote Monitoring of Heart Failure Patients with Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices: Patient Access, Acceptance, and Adherence to Use. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manyam, H.; Burri, H.; Casado-Arroyo, R.; et al. Smartphone-based cardiac implantable electronic device remote monitoring: improved compliance and connectivity. Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2022, 4, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kowal, D.; Baszko, A.; Czyż, K.; et al. Pacemaker remote monitoring challenges in pediatric population: Single center long term experience. Kardiol Pol. 2024, 82, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, V.H.; See Tow, H.X.; Fong, K.Y.; et al. Remote monitoring of cardiac implantable electronic devices using smart device interface versus radiofrequency-based interface: A systematic review. J Arrhythm. 2024, 40, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tajstra, M.; Dyrbuś, M.; Grabowski, M.; et al. The use of remote monitoring of patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices in Poland. Kardiol Pol. 2022, 80, 479–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landolina, M.; Perego, G.B.; Lunati, M.; et al. Remote monitoring reduces healthcare use and improves quality of care in heart failure patients with implantable defibrillators: the evolution of management strategies of heart failure patients with implantable defibrillators (EVOLVO) study. Circulation. 2012, 125, 2985–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parthiban, N.; Esterman, A.; Mahajan, R.; et al. Remote Monitoring of Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015, 65, 2591–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowal, D.; Katarzyńska-Szymańska, A.; Prech, M.; et al. Early smartphone app-based remote diagnosis of silent atrial fibrillation and ventricular fibrillation in a patient with cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonhorst, D.; Guerreiro, S.; Fonseca, C.; et al. Real-life data on heart failure before and after implantation of resynchronization and/or defibrillation devices - the Síncrone study. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2019, 38, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raafs, A.G.; Linssen, G.C.; Brugts, J.J.; et al. Contemporary use of devices in chronic heart failure in the Netherlands. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 1771–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).