1. Introduction

1.1. Context of Short-Term Load Prediction

The accuracy and efficiency of short-term electrical load prediction (STLP) is crucial for optimal power systems operation and economic efficiency in energy dispatch planning. In fact, with the growing levels of grid integration of variable renewable energy from non-programmable sources, smart meters, and electric mobility systems, the need for accurate SLTP becomes quite pertinent. Inaccurate electrical load prediction in short-term demand horizon can have profound impact on the availability of power generating units, unit commitment, economic dispatch of committed units, spinning reserve scheduling, system losses and stability margins [

1].

A load in an electrical grid can be measured as apparent power (KVA) or current (Amps). The total amount of power that can be drawn from a network transformer, measured in amperes, is referred to as Amp load. Therefore, the profile of Amp load follows the pattern of power consumption of a network. Typically, power is transmitted from the generating units to substations at high-voltage, then distributed from substations to transformer stations at medium voltage. According to IEC 60038 standard, medium voltage (MV) is defined as voltages from over 1 KV to 35 KV.

A systematic literature survey spanning over eight years (2015–2022) reveals that 54% of electricity load prediction was based on weather, time and economic parameters while the remaining 46% on household lifestyle and historical energy consumption [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Time effects comprise calendar parameters like day of the week and time of the day, and seasonal parameters like calendar holidays. The time-dependent electric load variance is periodic and reflects people’s lives, such as work schedules, social time, and sleeping patterns. The time effect was strongly evident during the early Covid-19 period, whereby most industrial and commercial units closed or operated on suppressed capacities thereby impacting the demand load, with a shift in domestic demand load due to ‘working from home’ policy. Weather is often considered a pivotal point that can lead to power system unreliability by lowering power supply efficiency [

8]. For countries around the Equator, weather factors that are widely used for STLP include temperature, humidity and wind speed. The accuracy of STLP can be improved through application of hybridized prediction models with a combination of weather variables, historical demand load and time factors. Despite being a widely researched area of study, there remains some open questions that need further research such as optimality of input data and hybridization approach.

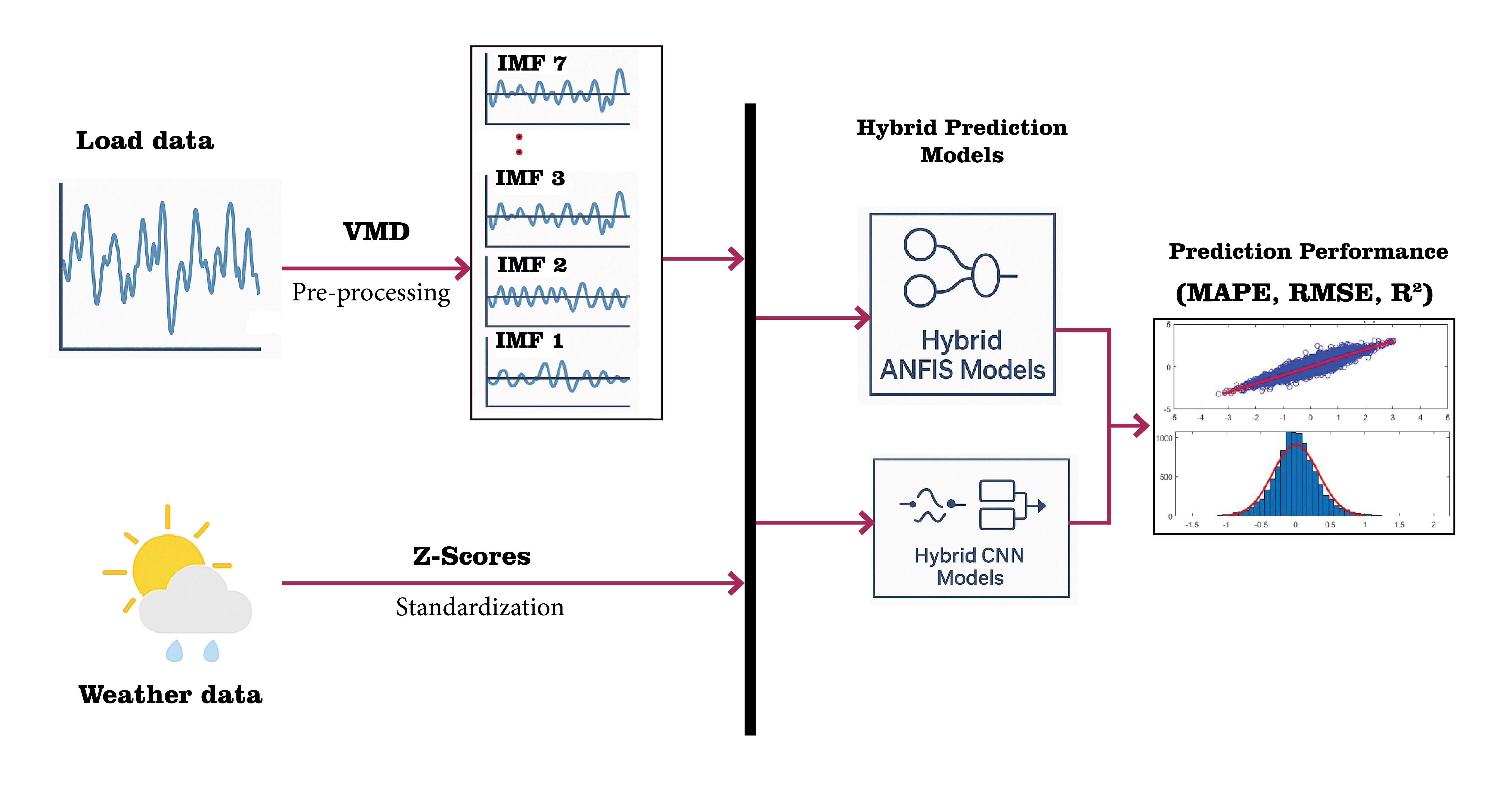

In this paper, the STLP performance of hybridized machine-learning (ML) models based on Artificial Neural Networks, Decision Tree Ensembles and Fuzzy Inference System approach with different learning algorithms and data decomposition, are evaluated and compared. The results would provide decision makers with valuable insights towards improving the choice of ML optimization algorithms and hybridization approach for the STLP applications. Therefore, the primary contributions and novelty of this study are summarized as follows:

Hybridized ML models based on Convolutional Neural Networks, Decision Tree Ensemble and Fuzzy Inference System frameworks are developed, trained and tested with different learning algorithms, for the prediction of Amp load in MV electricity networks. This innovative approach demonstrates the potential for improving short-term Amp load prediction, addressing uncertainties associated with economic dispatch in MV networks.

Dual-stage evaluation of the performance of these hybridized ML models on both training and testing datasets provides enhanced understanding of the model performance characteristics and valuable insights for practical applications

Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) approach is applied to extract intrinsic features in the historical (hour-before) load data in the form of frequency domains, followed by k-means clustering to classify and combine strongly corrected features to avoid multi-collinearity effect and improve the optimality of the training data.

1.2. Short-Term Load Prediction Techniques

There is extensive research work on short-term electricity demand prediction techniques in literature and the techniques are generally classified into two categories: Statistical (time series) and Machine Learning (artificial intelligence) methods. Statistical based (Time series) analysis fits a model based on seasonality and trend using historical data as an input. The inherent deficiency in statistical methods is the failure to accommodate the complex and non-linear relation of future electricity loads with previous demand load and meteorological factors, often yielding less accurate predictions [

1]. To address the challenges of statistical methods, the machine learning (ML) methods have been prevalently utilized for short term electricity demand predictions. ML approach utilizes a variety of optimization processes for non-linear modeling and adaptation without any prior assumptions about the load-weather relationship. The ML algorithms are trained based on available data to generate an outcome by supervised or unsupervised learning.

Some of the recent studies in literature focused on STLP using individual machine learning techniques include [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. The researchers used weather data, time factors and past load data as predictors. However, it is noteworthy that each individual ML method has some inherent deficiencies and their performance varies under different conditions, which poses limitations in practical applications. Thus, in order to reduce the risks of individual ML methods and improve the efficiency and accuracy of the predictions, hybridization of ML techniques is recommendable. Other researchers [

2,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] hybridized different ML-based models to predict electrical load and observed that the hybrid models improve the prediction accuracy by almost 3.5% above the closest-performing individual model. From this finding, it is apparent that hybridization of ML-based techniques is the best approach to improve the prediction accuracies. In this paper, the predictive performance of four hybrid ML models is comparatively assessed. The models comprise Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) integrated with Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm (PSO), ANFIS integrated with Genetic Algorithms (GA), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) fused with Long Short-Term Memory algorithm (LSTM), and CNN with extreme gradient boosting (XGB).

1.3. Machine Learning Methods for STLP

The basics and structure of the algorithm for each of the proposed ML models are presented and discussed here. However, the detailed mathematical theory of these models is widely available in literature and will not be presented in this paper.

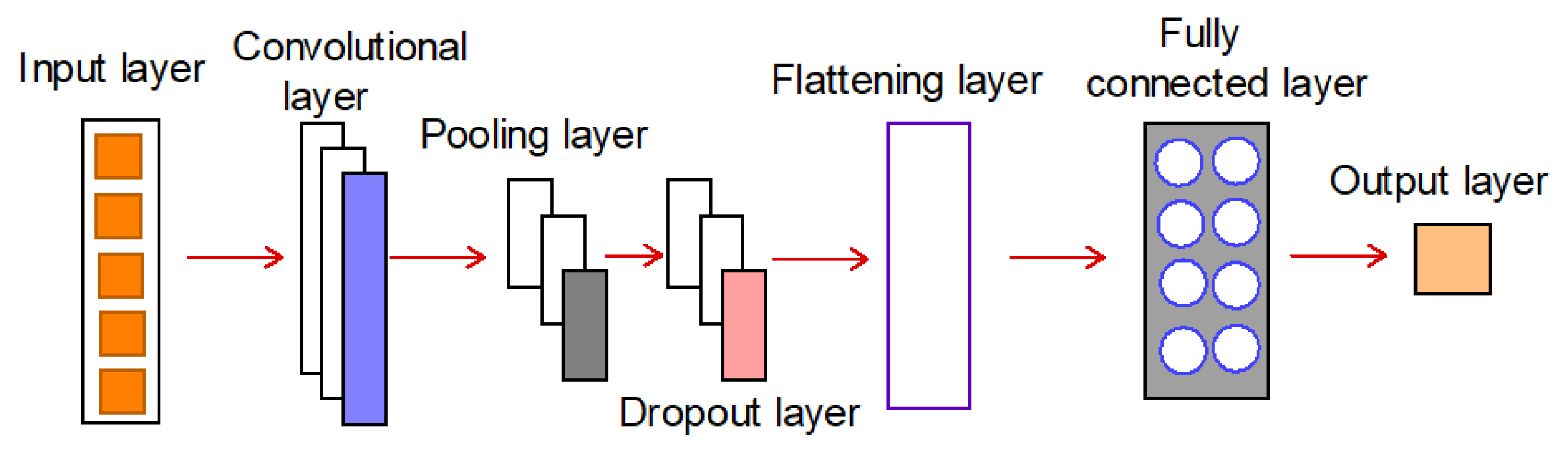

1.2.1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)

CNN is a deep neural network technique with capability to extract local trends from contiguous data [

21].

Figure 1 adapted from Tudose et al 2021 [

21] is a schematic representation of the structure of CNN model.

The input layer accepts the input data and passes it to the subsequent layers. The convolution layer applies a set of filters/kernels to the input data to extract features from the data. Considering a one-dimensional input, the convolution operation can be described by the following equation:

where * represents the convolution operator, while I and K are the 1-dimensional input and the kernel, respectively. The output of the convolution operation is the feature map.

A non-linear activation function is applied to the output of the convolutional layer to introduce non-linearity into the network. The pooling layer reduces the spatial size of the feature maps generated by the convolutional layer by down-sampling them i.e. extracts the maximum or average value of adjacent elements from a feature map. The dropout layer randomly drops out some of the neurons in the network by randomly setting a fraction of the activations to zero during training to prevent overfitting. The flatten layer converts the multi-dimensional feature maps generated by the previous layers into a one-dimensional vector that can be passed to a fully connected layer. The fully connected layer connects every neuron in the previous layer to every neuron in the current layer, while the output layer produces the final output of the network. However, it is noteworthy that the number of layers and their configuration in the CNN model depends on the characteristics of the input data.

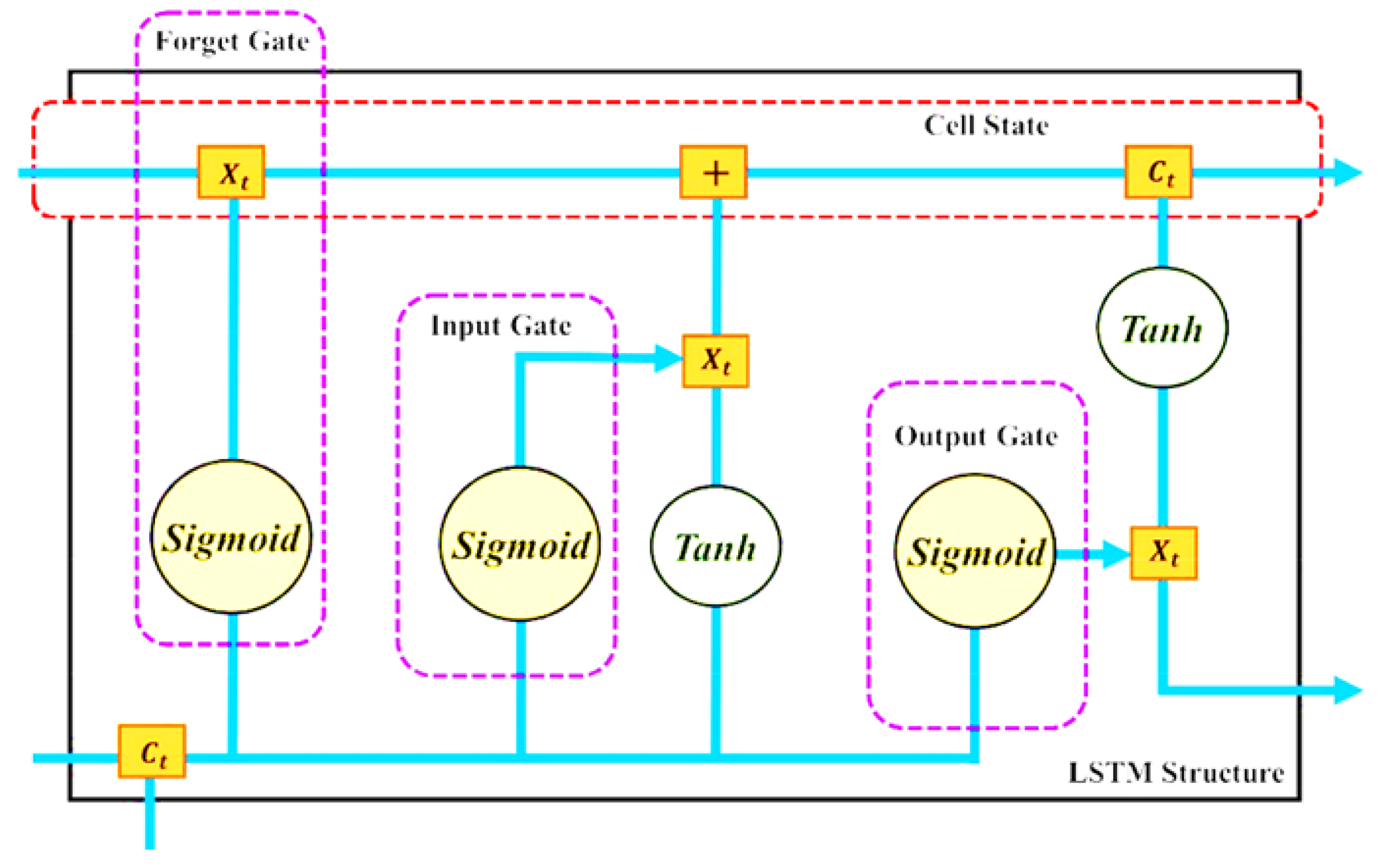

1.2.2. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

LSTM model is an extension of the recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to handle sequential data. LSTM was developed to overcome the vanishing and exploding gradients problem, which occurred with conventional RNNs when processing information that require long-term or short-term dependencies. It has memory cells and gates that allow it to selectively remember or forget information from previous time steps. The fundamental structure of LSTM module consists of three logistic sigmoid gates and one tanh layer as displayed in

Figure 2 [

19]. Each one of these gateways takes on a state variable at a particular time phase.

The input gate uses sigmoid function to control information that is passed from the current input and the previous hidden state into the memory cell while the forget gate decides how much information from the previous memory cell enters current memory cell. The memory cell is the internal state of the LSTM. The output gate uses the sigmoid function and tanh function to control the flow of information from the memory cell to the current hidden state and output [

16]. The study by Muzaffar and Afshari [

22] revealed that LSTM model has the potential to predict electric demand load on short-time horizons. The main drawback of LSTM is the tendency to overfit and the difficulty to apply regularization technique to curb this issue. Combining LSTM with other deep neural networks like CNN can mitigate the shortfall and improve the quality of predictions as demonstrated in the work by Guo et al [

23].

1.2.3. Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS)

ANFIS is a hybrid system of neural networks and fuzzy systems, with the ability to make fuzzy logic decisions with neural network computational capability. The fuzzy system component defines the membership functions while the neural network component is used to automatically extract fuzzy IF-THEN rules from numerical data and adaptively tunes the parameters of the membership function through a hybrid learning process [

24]. A membership function maps crisp input values to a fuzzy degree (between 0 and 1), indicating how much the input belongs to a fuzzy set as described by equation 2, where µA(x) is the membership value, x is the input value and A is a fuzzy set. This approach leverages the trainability of neural networks and the high decision-making power of fuzzy systems in conditions of uncertainty and certainty.

Considering a first-order Sugeno fuzzy model with two inputs x and y and one output f, a rule set with two fuzzy if-then rules can be expressed as shown in equations 2 and 3, in which p

1, q

1, r1 and p

2, q

2, r

2 denote consequent parameters learned during training, and A

1, A

2, B

1, B

2 are fuzzy membership functions [

25,

26]:

The equivalent ANFIS network structure can be be described by

Figure 3, which comprises five layers. Layer 1 is the input or fuzzification layer that converts numerical inputs into fuzzy values using membership functions. Layer 2 is the rule layer that applies fuzzy inference rules to model relationships in the data. Layer 3 is where normalization is performed using the weights of all neurons in the layer ensuring rule strengths sum to 1. Defuzzification occurs in layer 4 converting fuzzy output into a crisp predicted value while the final output is produced in Layer 5.

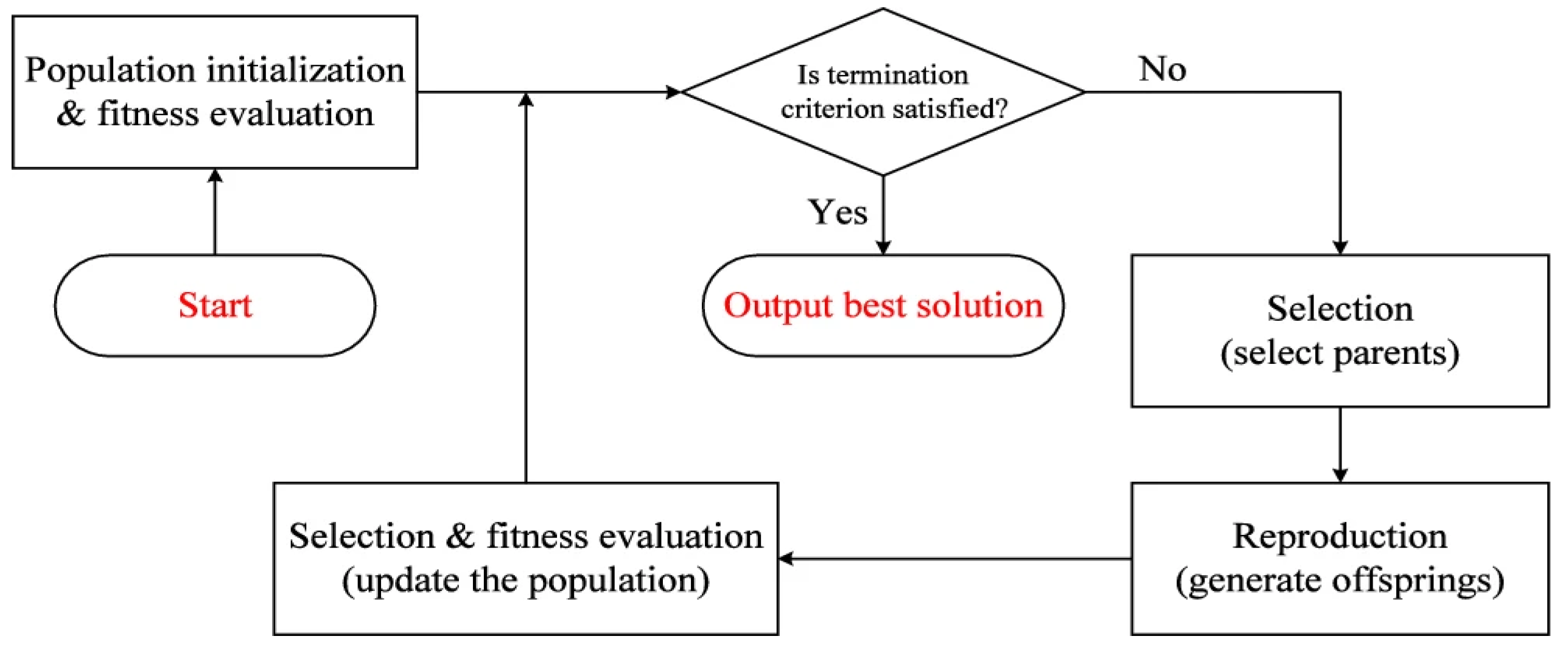

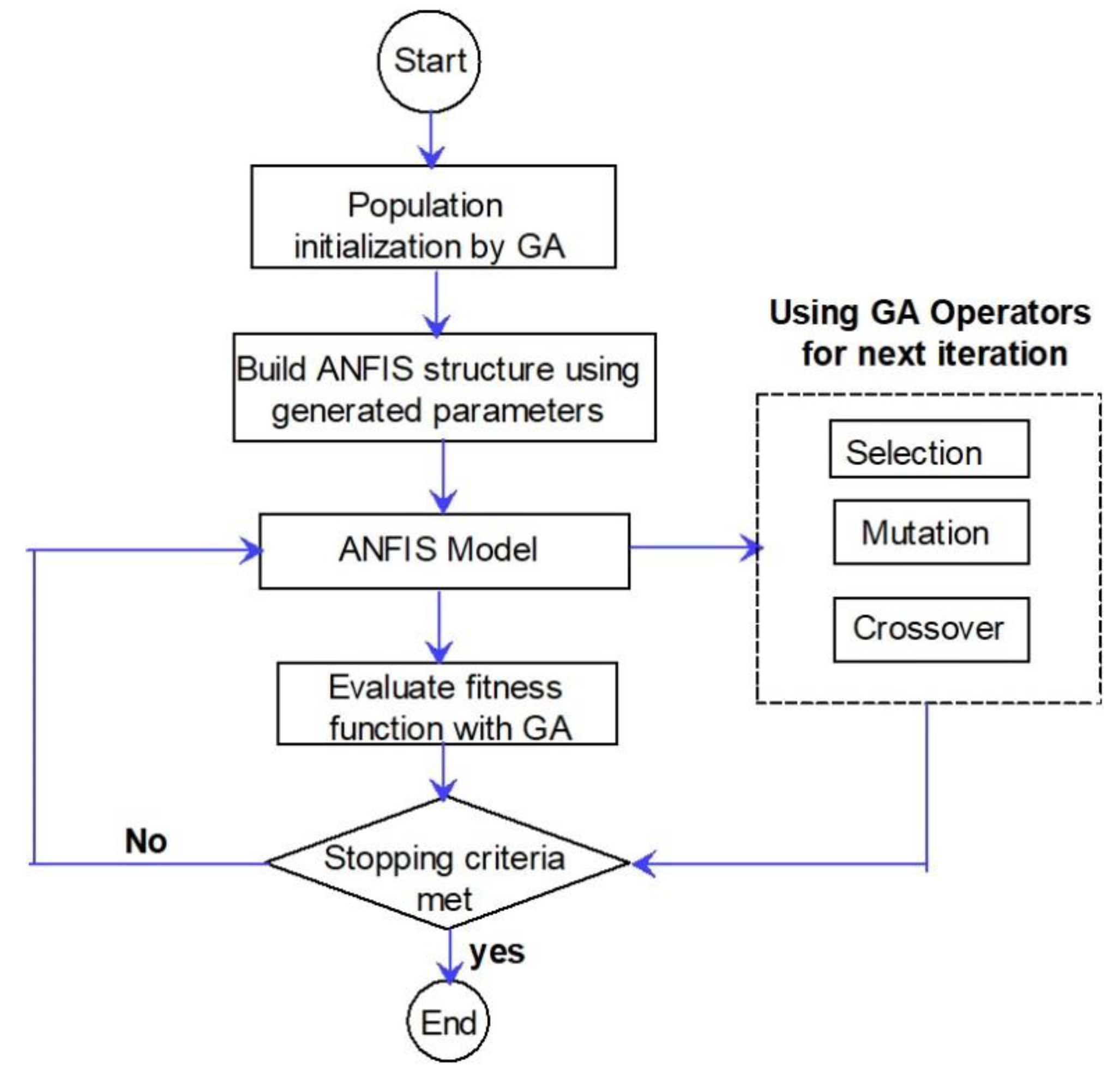

1.2.4. Genetic Algorithms (GA)

Genetic algorithm (GA) is a search-based algorithm for solving constrained and unconstrained optimization problems based on principles inspired by natural genetics to evolve solutions to problems. The basic idea is to maintain population of chromosomes that represents candidate solutions to a problem, and the candidate will evolve over a period of time through competition and controlled variation. Details of the GA framework can be reviewed in the work by Katoch et al [

27] and other studies available in literature.

Figure 4 is a flowchart of a GA solution search process. The algorithm terminates when either a maximum number of generations has been produced, or a satisfactory fitness level has been reached for the population.

Ray et al [

28] successfully applied GA to obtain the optimal parameters for LSTM model, which was then applied to predict the hourly electricity load using hourly weather data obtained from the Australia Bureau of Meteorology and hourly electricity load data obtained from the Australian Energy Market Operator. Also, Santra and Lin [

29] who used a hybrid model of LSTM and GA to predicts hourly to daily electricity load one hour to one week ahead, with good accuracy.

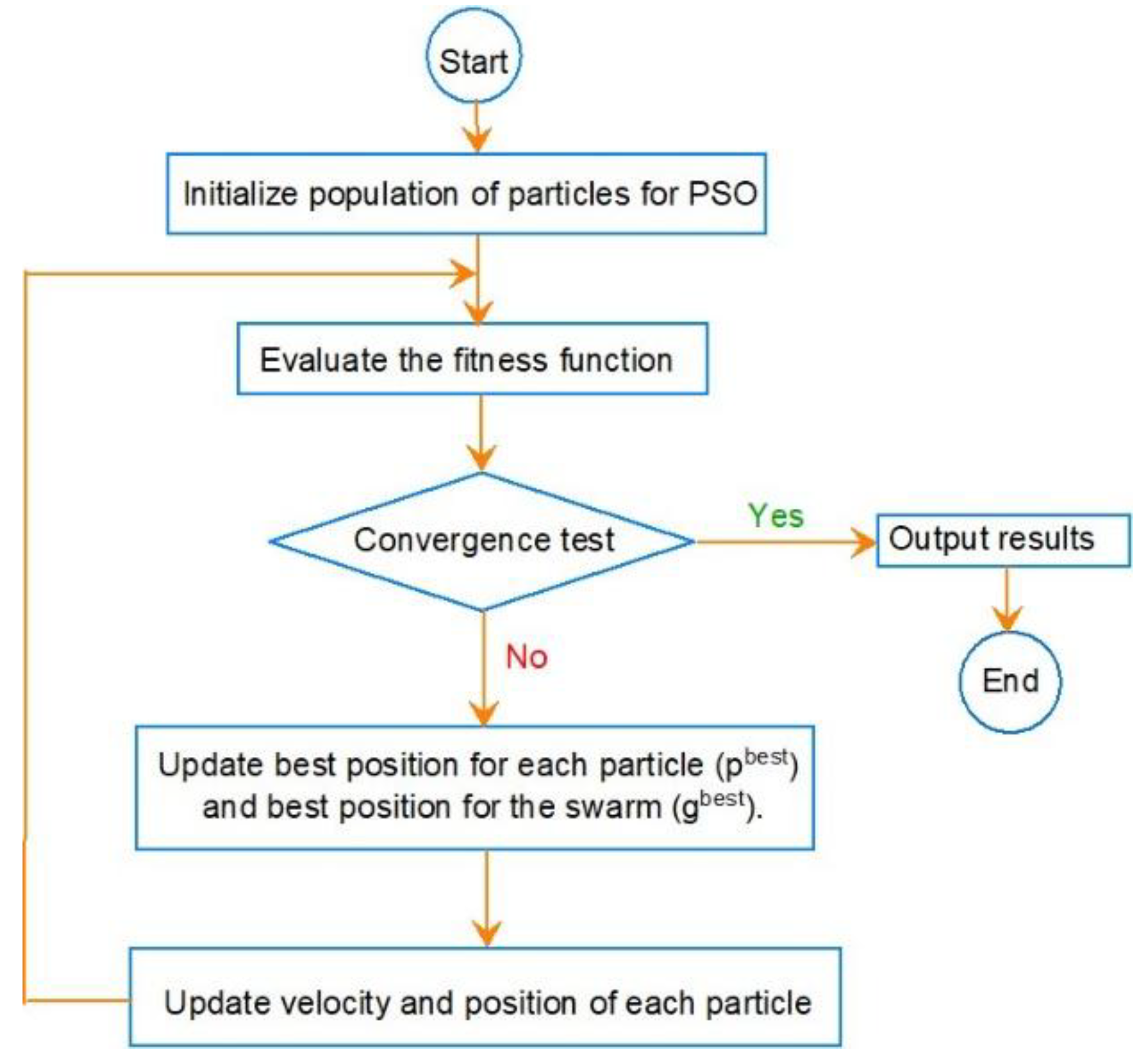

1.2.5. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

PSO is a collective intelligence algorithm based on the concept of swarm intelligence, with ability to perform a global search and optimization [

24]. A population of random solutions is used to initialize PSO algorithm and the search for optimal solution is done by updating the positions of the particles at each successive iteration. PSO scatters a population (swarm) of candidate solutions (particles in a swarm), and the movement of each particle is affected by its best position and the best position of the swarm. The basic structure of PSO algorithm in shown in

Figure 5. Details of the governing equations for PSO algorithm are widely available in literature and will not be repeated here. PSO has been used by different researchers to improve the performance of artificial neural network models in various predicting applications. Ozerdem et al [

30] used PSO for short term electric load forecasting. The results obtained showed that the PSO optimized feedforward networks are suitable regressors for modeling energy demand. In another study, Chafi and Afrakhte [

31] applied deep neural network and PSO in Short-term load forecasting, achieving fast convergence and relatively low mean absolute error. This was collaborated by Hong and Chan [

32] who combined PSO and CNN to study Hourly load data in Taiwan Power Company. The simulation results indicated better predictive performance in comparison to Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average model, which underscores the merits of PSO.

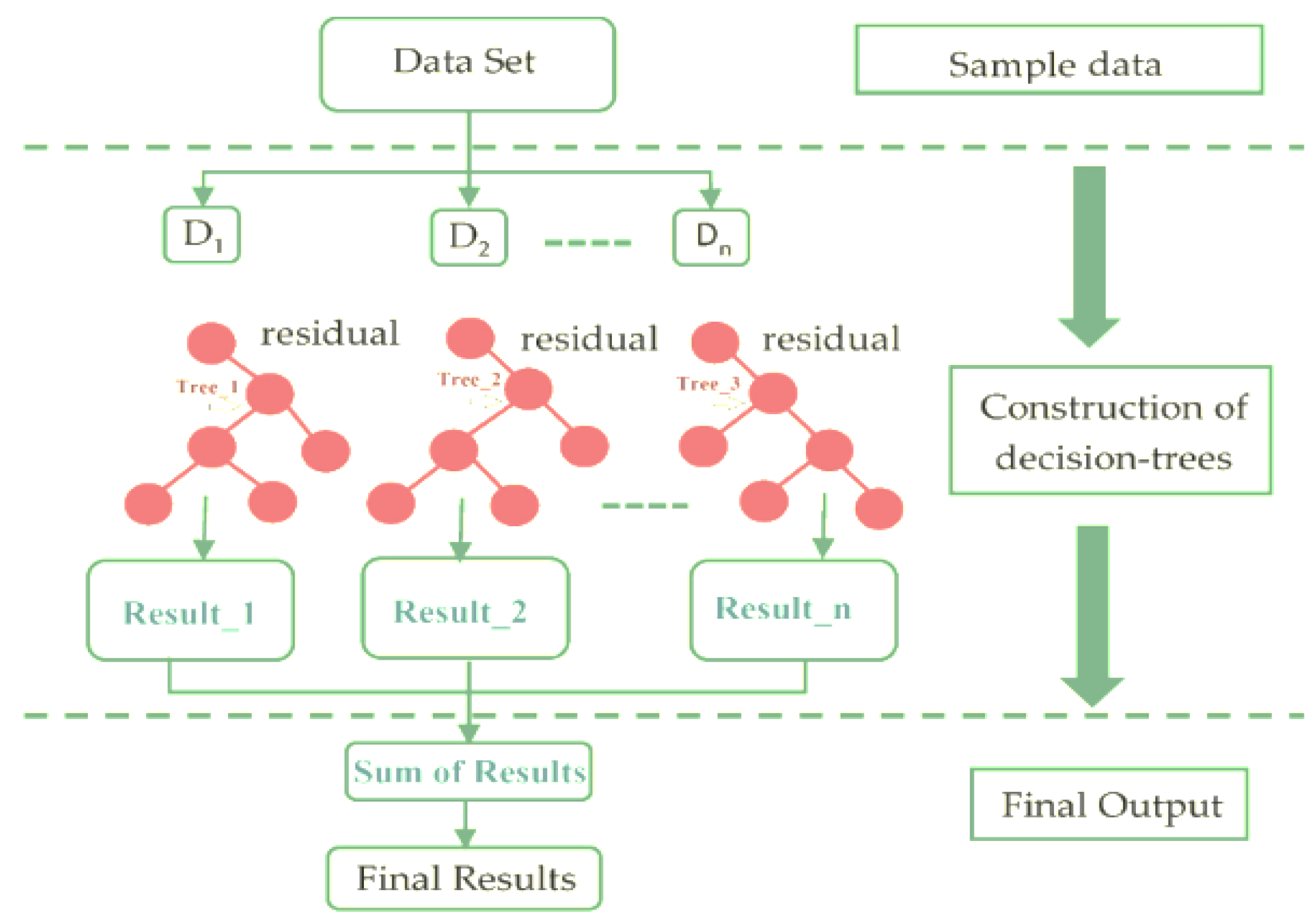

1.2.6. Extreme Gradient Boosting Tree Ensemble (XGB)

A decision tree ensemble model is a machine learning method that combines multiple decision trees to make better and generalized predictions. Each decision tree in the ensemble takes input data and splits it into smaller groups based on different features. Each split creates branches, and at the end of these branches are the predictions. The ensemble combines all these individual predictions to make a final, more accurate prediction [

33,

34].

Figure 6 represents the structure of the XGBTE search algorithm.

Gradient boosting builds an ensemble of decision trees sequentially such that the set target outcomes are dependent on the gradient of the error versus the prediction. Each new tree model added to the ensemble tries to correct the errors made by previous ones. At the m-th iteration, a simple tree model hm(x) is added to the previously built overall model, and it is fitted to predict the residuals of the model Hm-1(x) available from the previous (m-1)-th iteration giving a new prediction model, Hm(x). The parameter η is the learning rate (scaling factor).

The final prediction is the weighted sum of predictions from all the trees. A loss function is optimized using gradient descent method, reducing errors iteratively. One drawback of this technique is the possibility of becoming too complex and overfit the data, leading to poor generalization. To optimize performance, it is essential to tune the hyperparameters (number of trees, learning rate, tree depth, minimum samples per leaf and shrinkage)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hybridization of the Models

This study explores the hybridization of Machine Learning (ML) models and application of different learning and optimization algorithms in short-term electric load prediction to overcome the limitations inherent in individual ML algorithms. Four different hybrid ML models are evaluated, namely CNN-LSTM, CNN-XGB, ANFIS-PSO, and ANFIS-GA. The basics and structure of the algorithm for each of these models are presented and discussed in the sections that follow.

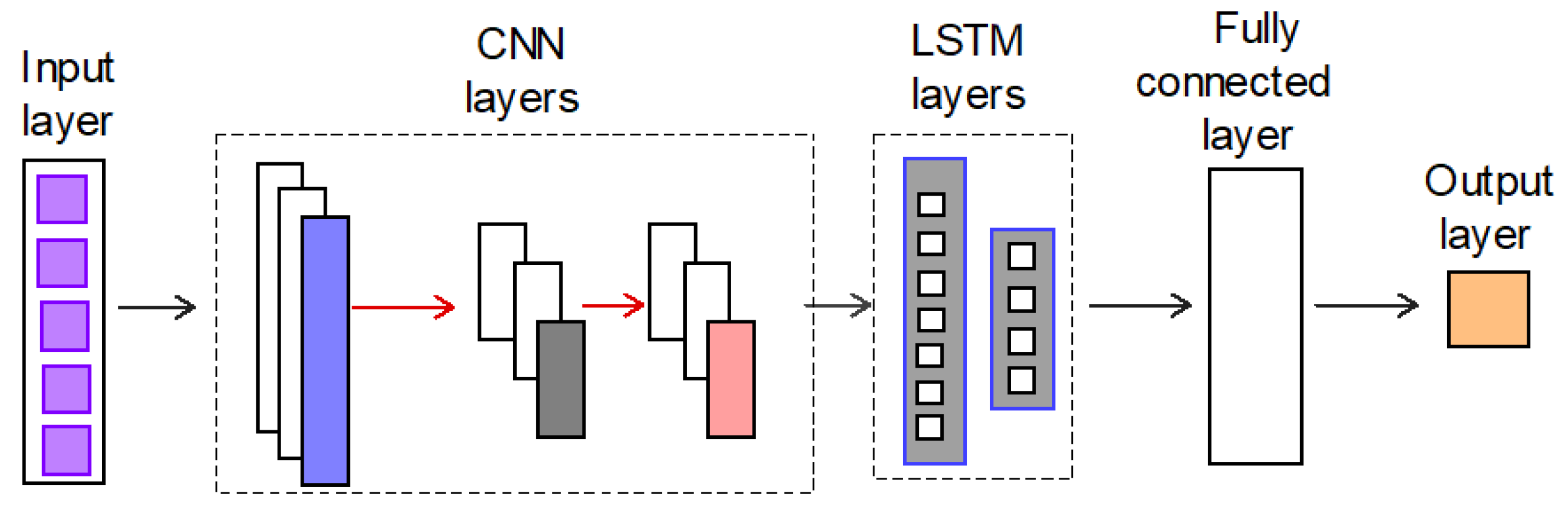

2.1.1. CNN-LSTM

The structure of the CNN-LSTM model assessed here involves Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) layers for feature extraction (spatial and local temporal patterns) on input data combined with LSTMs to support learning and Amp load prediction. The LSTM uses cells and gates to regulate information flow through the network, and can memorize information over longer sequences thereby overcoming the vanishing gradient problem.

Figure 7 illustrates the algorithm for the CNN-LSTM model implementation. A rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function has been used for each convolutional and fully connected layer

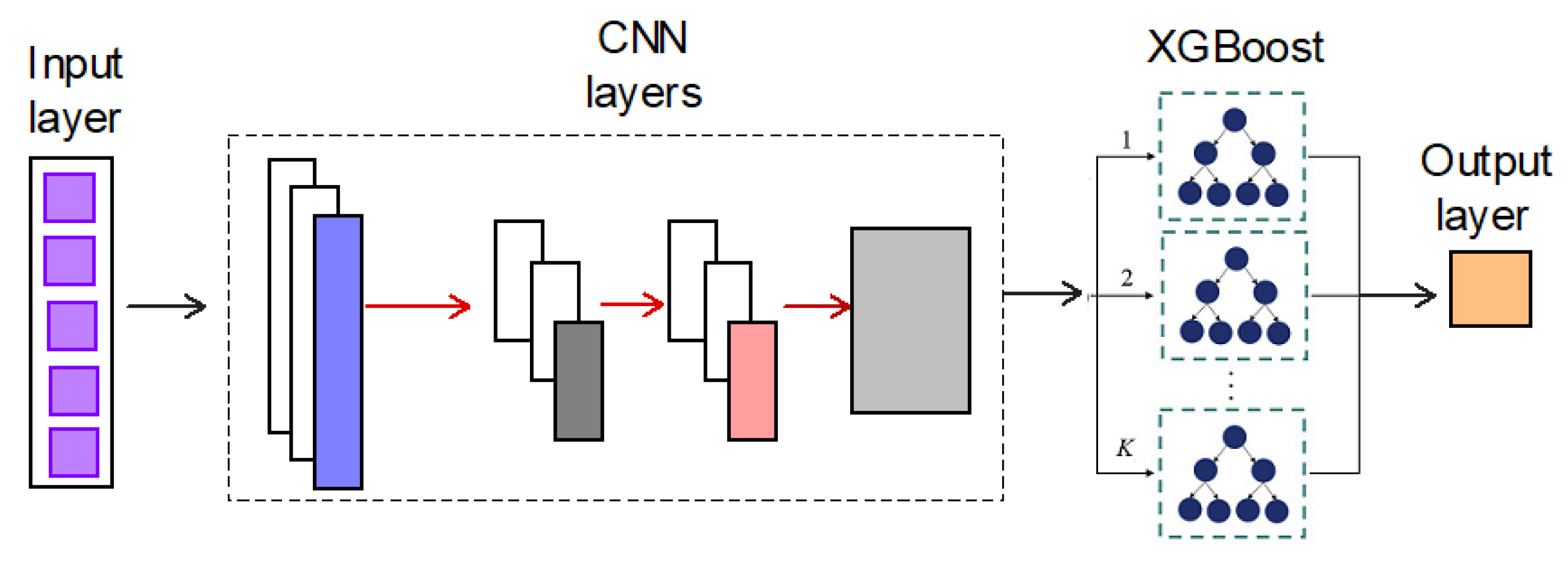

2.1.2. CNN-XGB

The hybrid model of CNN combined with XGB leverages both deep learning and ensemble learning for robust Short-term load prediction. The CNN component extracts features (captures spatial dependencies) from historical load data and other input variables using convolutional layers. The extracted feature maps are flattened into feature vectors. The feature vectors are passed into XGB, which builds multiple decision trees and optimally weights them using gradient boosting. The trained model predicts the short-term electricity load using the optimized tree ensemble where each decision tree casts a vote and the ensemble predicts the majority vote of all of its trees.

Figure 8 is a schematic representation of the training and prediction algorithm.

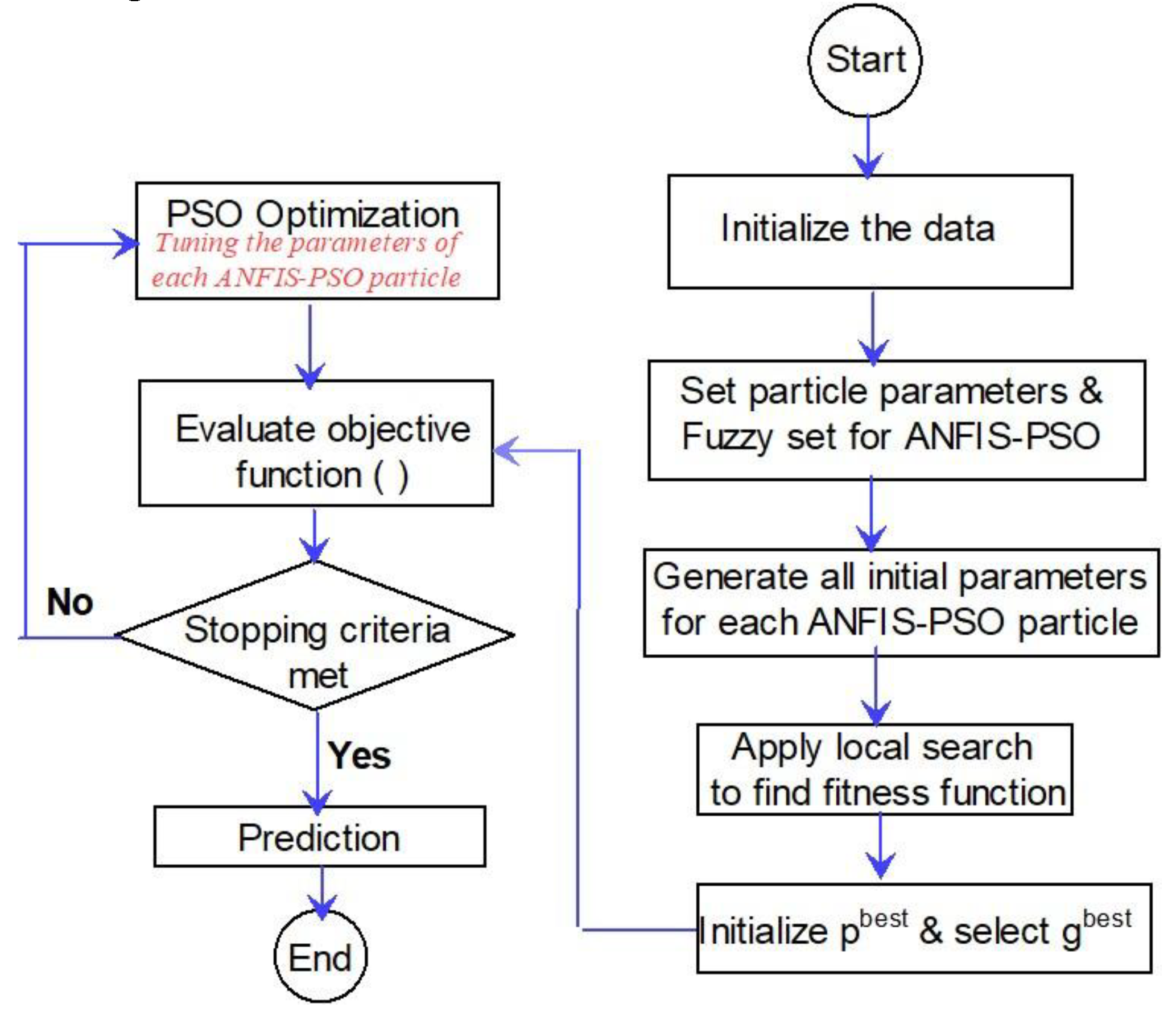

2.1.3. ANFIS-PSO

ANFIS-PSO combines metaheuristic optimization and fuzzy logic-based modeling for accurate short-term load prediction. In this study, the ANFIS was initialized with fuzzy membership functions and inference rules to predict the Amp-load through adaptive learning. The Gaussian membership function was used because it is smooth and differentiable and provides better adaptability for machine learning models. The optimized ANFIS model learns from historical data and updates the parameters accordingly. The trained ANFIS-PSO system was then applied to predict short-term Amp load. Each particle in PSO represents a candidate set of ANFIS parameters.

Figure 9 illustrates the ANFIS-PSO optimization algorithm.

The Particle Velocities and Positions are updated based on their own best solution (pbest) and global best solution (gbest) using velocity and position update formulas:

where, w is inertia weight, c1, c2 are learning factors, r1, r2 are random values, vi is particle velocity and xi is particle position.

2.1.4. ANFIS-GA

The hybrid ANFIS-GA model integrates the learning capabilities of ANFIS with the global optimization power of GA. The GA optimizes the structure and parameters of ANFIS by simulating evolutionary selection and mutation. The ANFIS parameters (shape, centre and spread of membership function, weights in the neural network structure, fuzzy rules) are encoded into a genetic representation as genes in a chromosome. The fitness of each chromosome is evaluated using ANFIS prediction accuracy, which is RMSE for this study. The GA selects the best performing solutions and evolves them over iterations (crossover and mutation). The best set of parameters is used for ANFIS training and the best-trained ANFIS model is used for prediction.

Figure 10 illustrates the ANFIS-GA algorithm.

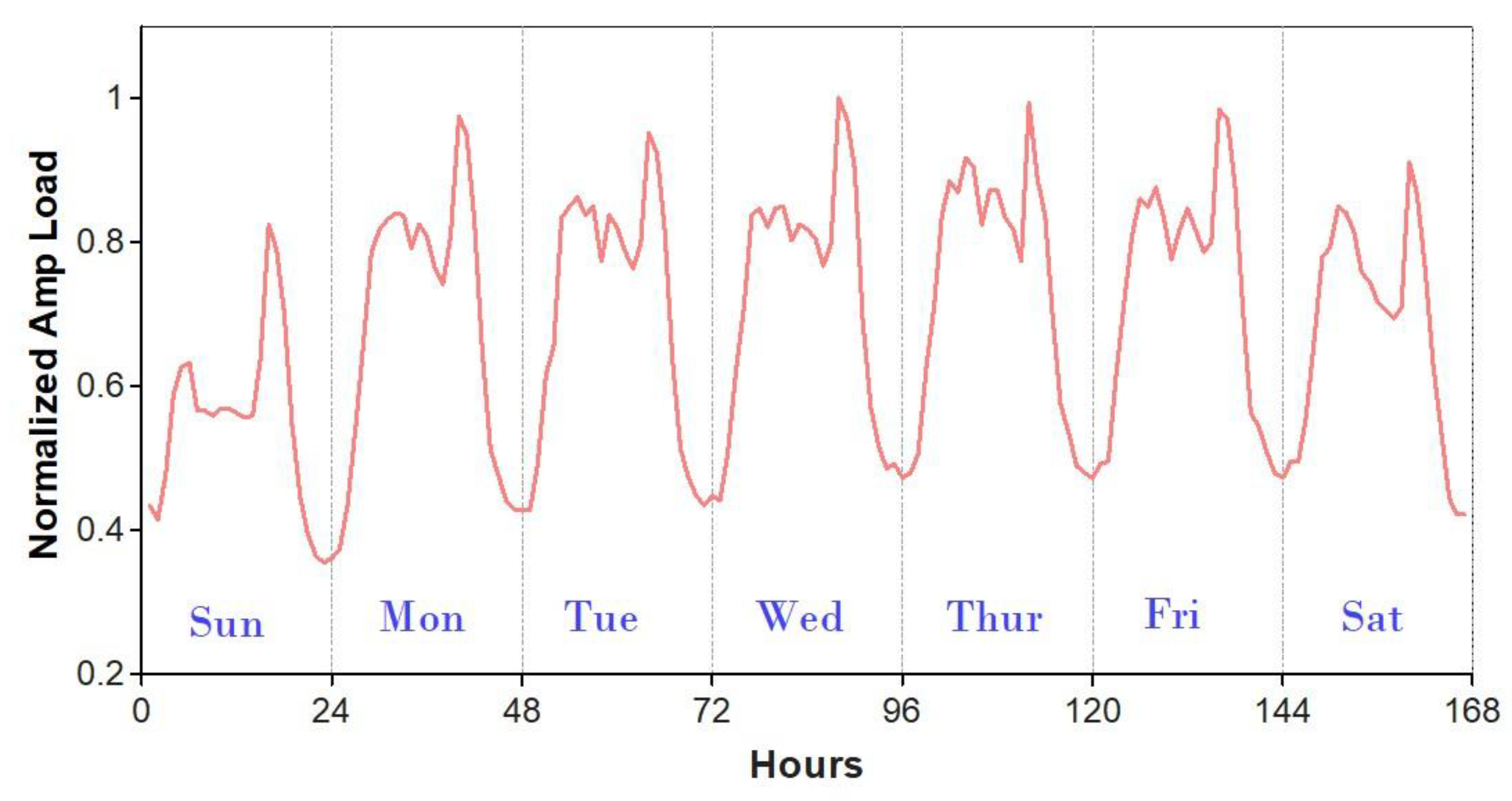

3.1. Dataset

The actual historical load data covering the period of January 2023 to June 2024, comprising hourly electrical Amp load was obtained from Rivatex substation in Kenya. The data was recorded from a 45MVA Transformer operating at distribution voltage of 33KV/11KV. The Amp load was measured at the circuit breakers (CBs) connecting the transformer to different load feeders. The CBs were rated at 80% of total load. The weather data, consisting of Temperature, Wind speed, and Humidity were obtained from a Moi University weather station, within the neighbourhood of the Rivatex sub-station.

Figure 11 depicts the normalized hourly Amp load profile spanning one week (168 hourly loads) as recorded at Rivatex power utility sub-station. To capture the complex features of the load profile, the Amp load values from the previous week hourly loads were used alongside weather data as input to the model.

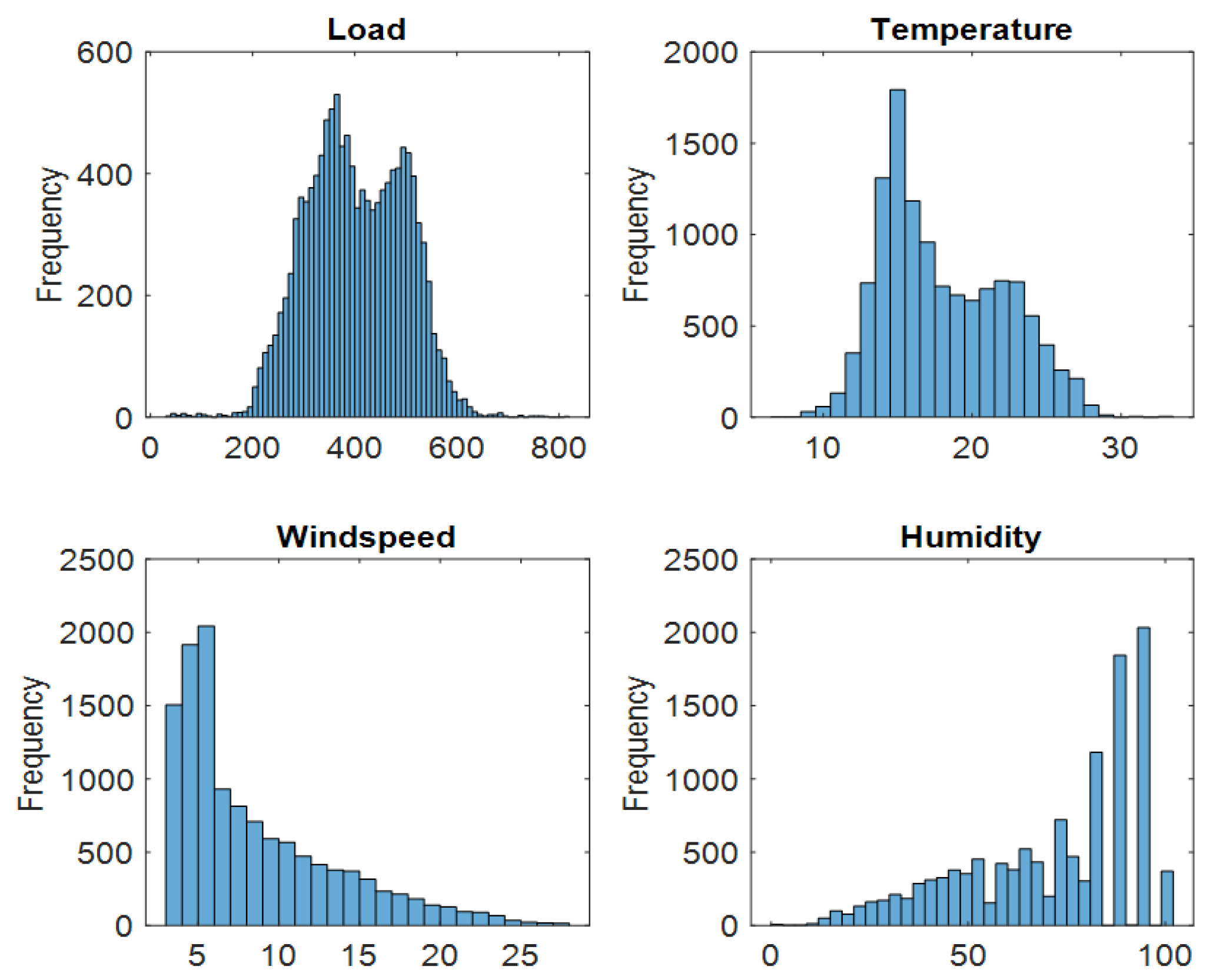

3.2. Data Processing

Data pre-processing was performed on the raw dataset to remove distorted data and unwanted variabilities that are not related to the feature variables, such as sudden drop of load resulting from a change of large industrial or commercial load in the grid. The initial step was to clean the data by correcting erroneous data, removing duplicate entries and addressing missing values. The missing values were handled through imputation while outliers were removed using z-score method in MATLAB. The noise in the historical data was reduced using moving average smoothing. The data was then normalized by mean centering and variance scaling in order to ensure consistent predictions and avoid the disproportionate influence of various features. The pre-processed dataset contained 12000 datapoints that was divided into the training part (75%), and testing and validation part (25%).

Figure 12 shows the statistical distribution of the data while

Figure 13 shows the correlation analysis results between Amp load and weather variables. The dependent variable is the Amp load, and the independent variables are the weather parameters. The color bars in the right of each figure represent the range of the correlation coefficient, and the numbers in the figure represent the correlation coefficient. Among the weather variables, air temperature has the most significant impact on the amp load with a correlation of 0.43.

3. Results

This study explored different hybridizations of Machine Learning models and evaluated their comparative prediction performances. The models were hybridized to assess the effectiveness of combining different machine learning algorithms to improve accuracy and reliability in predicting Amp load behaviour over short time horizons. The results of the study are presented in this section. The Amp load data was recorded at one-hour resolution.

3.1. Model Training and Testing

A fitness function (objective function) was employed for the training and testing of the proposed hybrid models. Three frequently used metrics described by equations 7-9, namely Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Coefficient of Determination (R2) were utilized to evaluate the performance of the models.

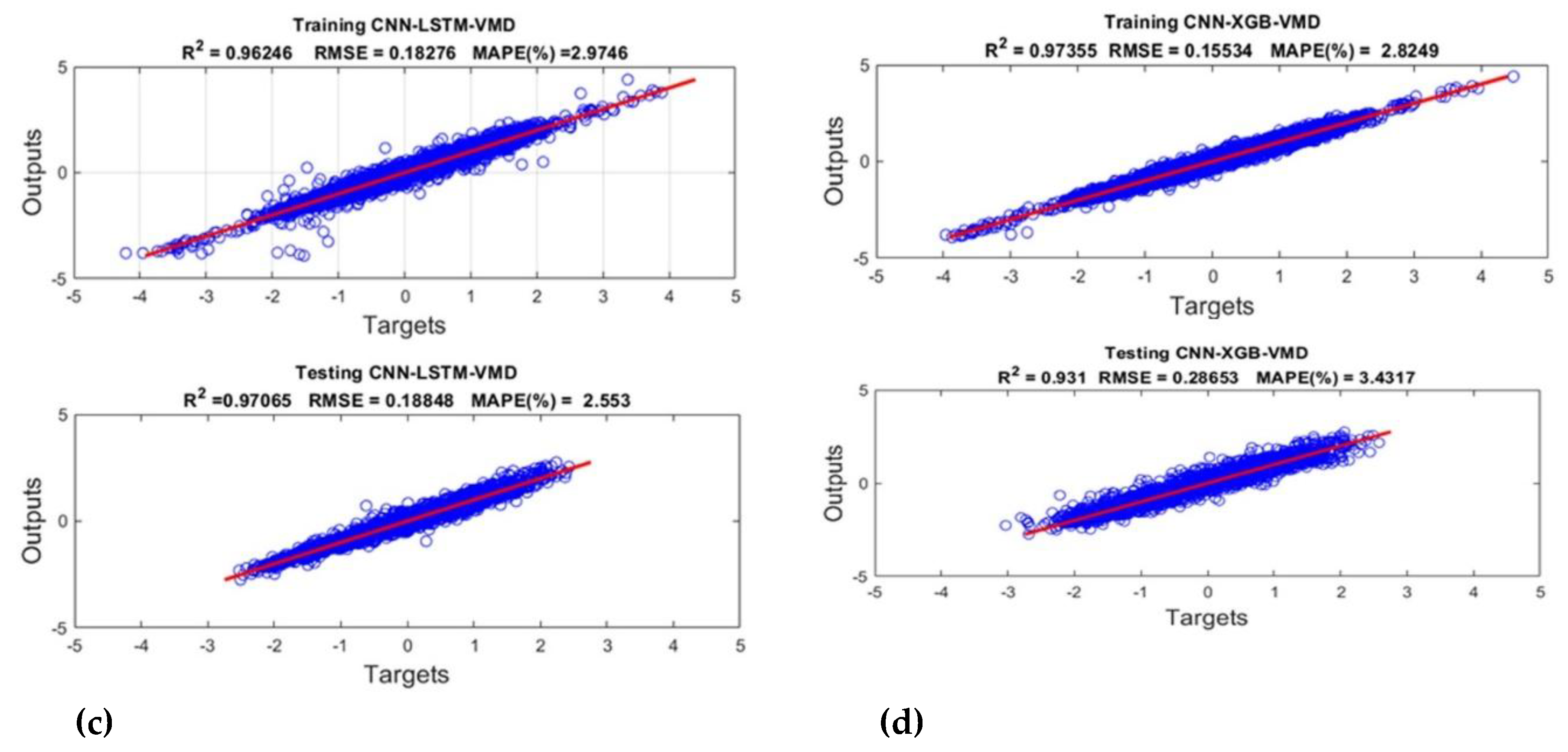

Presented in

Figure 14 (a-d) are the outcomes of model training and testing for the four hybrid models considered i.e. ANFIS-PSO, ANFIS-GA, CNN-LSTM, CNN-XGB).

3.2. Model Training and Testing with Load Data Decomposition

To improve the accuracy of prediction, the Amp load data was pre-processed using Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) technique. The raw Amp load signal was broken down into sub-signals called Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMF) with distinct spectral characteristics to extract intrinsic features related to Amp load pattern. This enables better analysis of the load data by reducing the uncertainty and irregularity in the load data. Details of VMD can be reviewed in the work by Ahajjam et al [

35]. The influential parameters, mode number and the penalty factor need to be determined in advance. The default value of the penalty factor, α = 2000, is used in this paper. The data was decomposed into 7 IMFs as shown in

Figure 15. The optimal number of modes, was determined by k-means clustering of the data. In determining the number of modes, it is noteworthy that high number of modes may result in mode mixing or purely noisy modes, whereas low number of modes may lead to duplicate modes [

36].

Presented in

Figure 16 (a-d) are the results of model training and testing with Variable Mode Decomposition of load data for the four hybrid models considered i.e. ANFIS-PSO, ANFIS-GA, CNN-LSTM, CNN-XGB)

4. Discussion

The predictive performance of the four hybrid models was analysed using three key metrics, namely MAPE, RMSE and R

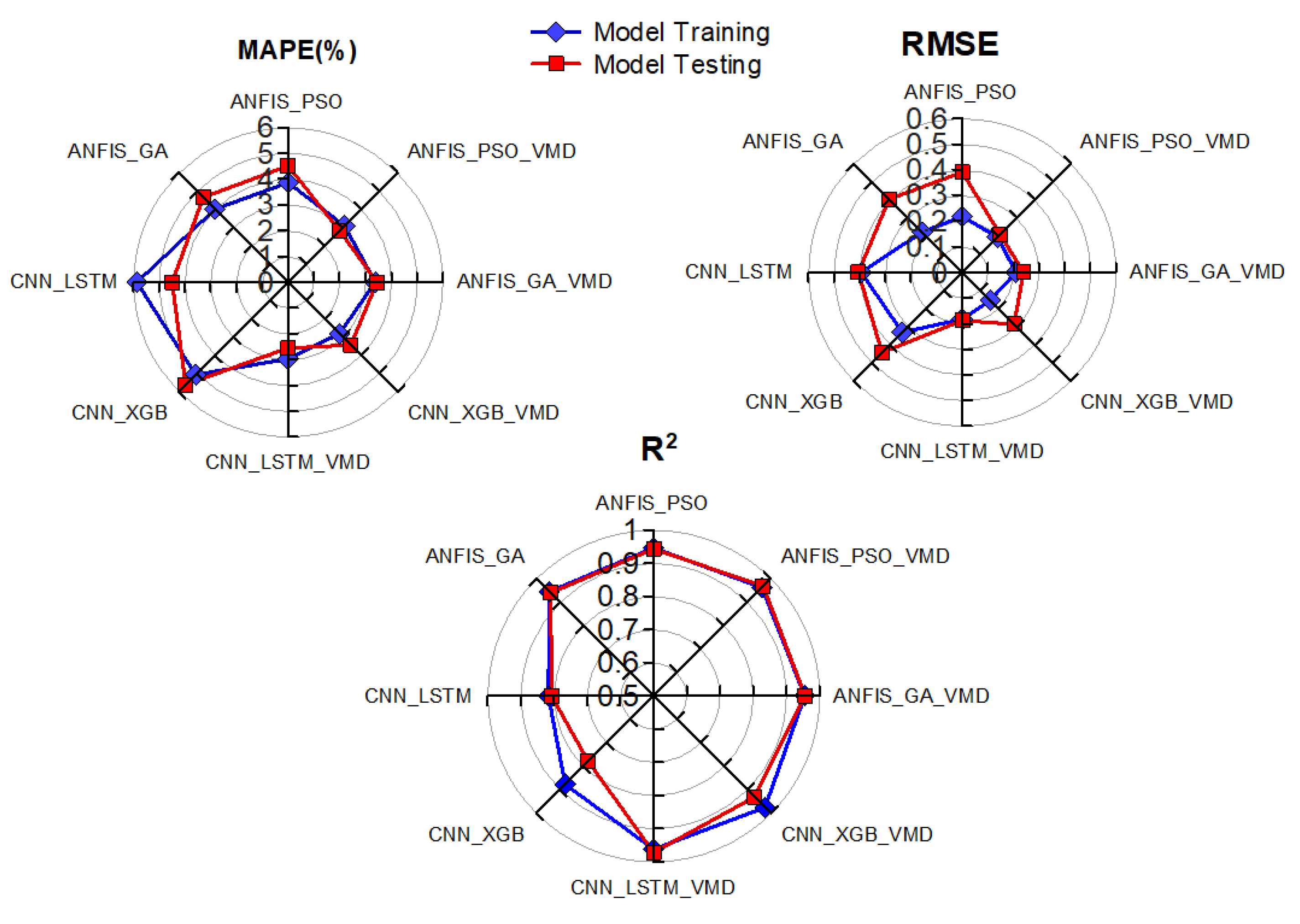

2. The results are compared using radar plots as shown by

Figure 17. The models with lower MAPE and RMSE and higher R

2 on testing data perform better. From

Figure 17, it is noticeable that hybrid models with Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) are highly effective for STLP, achieving relatively low MAPE and RMSE with high R2 scores. Overall, two hybrid models, CNN-LSTM-VMD and ANFIS-PSO-VMD outperformed other models in all metrics.

For the models tested without data decomposition, ANFIS-GA and ANFIS-PSO achieve slightly lower MAPE and RMSE, and higher R2 suggesting better predictive accuracy than CNN-LSTM and CNN-XGB models. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that models based on evolutional optimization (PSO, GA) show competitive results when properly tuned [

24,

28]. The ANFIS can capture fuzzy rules and learn them adaptively enabling accurate approximation of non-linear relationships, and when optimized with GA or PSO, it can fine-tune rule sets and membership functions efficiently [

25].

For the deep-learning models, CNN-LSTM outperformed the CNN-XGB in terms of MAPE and RMSE indicating marginally lower error magnitude on average and better handling of peak loads. The relatively inferior performance by CNN-XGB is attributed to the design of CNN that is optimized for spatial data, and not efficient for capturing temporal patterns observed in electric load behaviour.

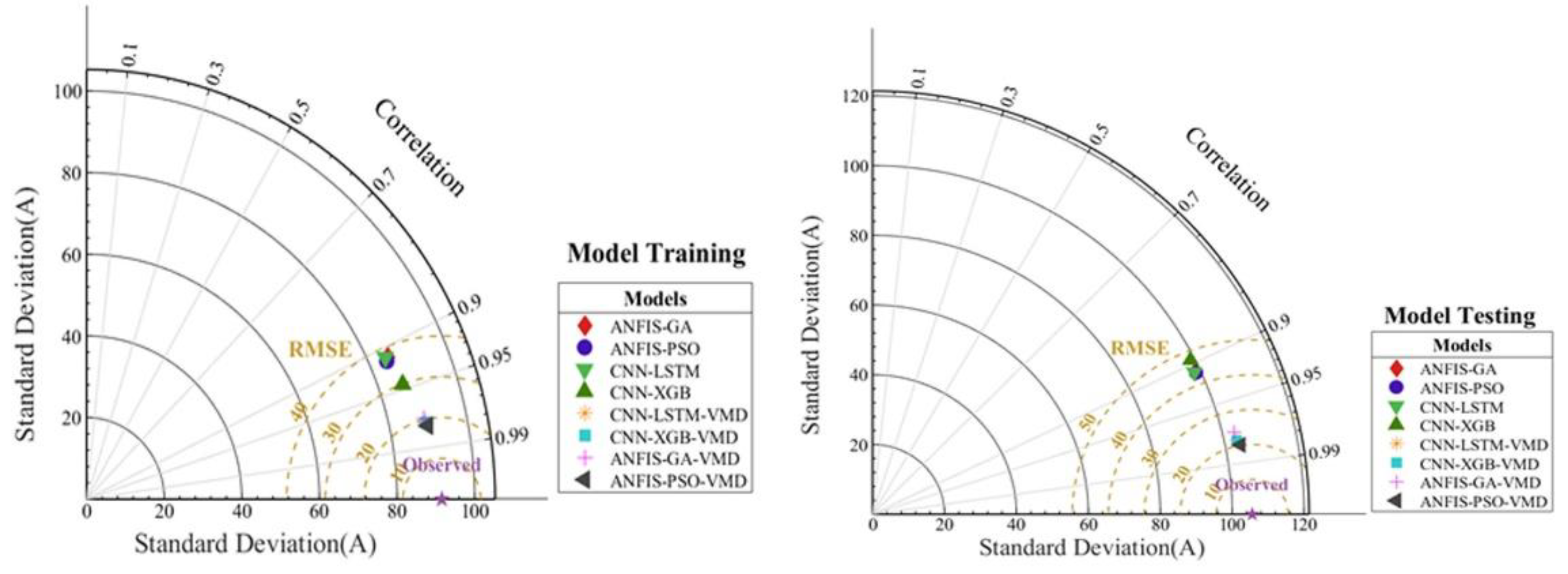

The quality of the predictions by the hybrid models presented here was further compared using the Taylor plots as shown in

Figure 18. The balance between standard deviation (radial distance), correlation and RMSE determines overall model quality [

37]. The observed data represents the reference point with standard deviation equal to that of the observations. If the model point lies farther from the origin than the reference point, it has a larger standard deviation than the observations and if it lies closer, it has lesser variability than the observations. The angle from the x-axis represents the correlation coefficient. The smaller the angle (model point is closer to the x-axis), the higher the correlation with observations. Hence, a point that lies directly on x-axis has a correlation coefficient of 1. The centred room mean square error (RMSE) represents the distance of the model point from the reference point. A smaller distance corresponds to a smaller RMSE.

The results displayed by

Figure 18 corroborates our initial findings whereby hybrid models with evolutionary optimization (PSO and GA) have demonstrated better performance that convolutional deep learning hybrid models in Short-Term Load Prediction. But Variational Mode Decomposition of load data improved the prediction accuracy across all models.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents a comparative assessment of the prediction performance of hybridized machine-learning (ML) models comprising convolutional neural networks with long short-term memory network and gradient boosting ensembles, and Fuzzy Inference System with evolutionary optimization, for short-term Amp-load prediction in medium-voltage electric networks. Based on three statistical indicators namely, MAPE (for accuracy), RMSE (for error minimization) and R2 (for predictive power), the adaptive neuro-fuzzy hybrid models with evolutionary optimization (ANFIS-PSO, ANFIS-GA) achieved better performance. The performance metrics were further evaluated using Taylor plots, which corroborated these findings. The relatively inferior performance by convolutional neural network hybrid models (CNN-LSTM, CNN-XGB) is attributed to the design of CNN that is optimized for spatial data, and not efficient for capturing temporal patterns observed in electric load behaviour. The results indicate that if tuned well, hybrid models based on adaptive neuro-fuzzy approach and optimized with evolutionary algorithms are more suitable for short-term load prediction in medium voltage electric networks given the temporal pattern of the Amp load behaviour. Lastly, the pre-processing of load data by variational mode decomposition (VMD) improved the prediction accuracy of all the models owing to enhanced feature extraction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Project administration, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing original draft (A.B. M); Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation, Software (A. A); Formal analysis, Writing – review and editing, Visualization (S.S).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The support by Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU), Norway for data analysis under the Norwegian Partnership Programme for Global Academic Cooperation (NORPART).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VMD |

Variational Mode Decomposition |

| STLP |

Short-Term Load Prediction |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Networks |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| XGB |

Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| PSO |

Particle Swarm Optimization |

| GA |

Genetic Algorithms |

| ANFIS |

Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System |

| MV |

Medium Voltage |

| MAPE |

Mean Absolute Percent Error |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Square Error |

| IMF |

Intrinsic Mode Functions |

| RNN |

Recurrent Neural Networks |

References

- Kuster, B.; Rezgui, Y.; Mourshed, M. Electrical load forecasting models: A critical systematic review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 35, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohan, M.J.A.; Faruque, M.O.; Foo, S.Y. Forecasting of electric load using a hybrid LSTM–Neural Prophet model. Energies 2022, 15, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, A.A.; Alghassab, M.; Ullah, K.; Khan, Z.A.; Lu, Y.; Imran, M. A review of electricity demand forecasting in low- and middle-income countries: The demand determinants and horizons. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbuks, J. Assessing the accuracy of electricity production forecasts in developing countries. Int. J. Forecast. 2019, 35, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrawati, A.; Girsang, A.S. Electricity demand forecasting using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system and particle swarm optimization. Int. Rev. Autom. Control 2016, 9, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Pandya, M.; Aware, M. Short term load forecasting of Indian system using linear regression and artificial neural network. In Proceedings of the 5th Nirma University International Conference on Engineering, Ahmedabad, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, T.E. Short-Term Electrical Load Forecasting for an Institutional/Industrial Power System Using an Artificial Neural Network. Master’s Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Phuangpornpitak, N.; Prommee, W. A study of load demand forecasting models in electric power system operation and planning. GMSARN Int. J. 2016, 10, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yazici, I.; Beyca, O.F.; Delen, D. Deep-learning-based short-term electricity load forecasting: A real case application. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 109, 104645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, F.; Martín, F.; Fontán, L.; Galarza, A. Very short-term load forecaster based on a neural network technique for smart grid control. Energies 2020, 13, 5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houimli, R.; Zmami, M.; Ben-Salha, O. Short-term electric load forecasting in Tunisia using artificial neural networks. Energy Syst. 2020, 11, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R.; Razzaq, S.; Alquthami, T.; Moghal, M.R.; Amin, A.; Mahmood, A. Day-ahead load forecasting for IESCO using artificial neural network and bagged regression tree. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Power, Energy and Smart Grid (ICPESG), Mirpur Azad Kashmir, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.Q.; Chang, L. A combination model with variable weight optimization for short-term electrical load forecasting. Energy 2018, 164, 575–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J. Load forecasting for regional integrated energy systems based on complementary ensemble empirical mode decomposition and multi-model fusion. Appl. Energy 2024, 353, 122146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaoudi, M.; Refaat, S.S.; Chihi, I.; Trabelsi, M.; Oueslati, F.S.; Abu-Rub, H. A novel stacked generalization ensemble-based hybrid LGBM–XGB–MLP model for short-term load forecasting. Energy 2021, 214, 118874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina, J.; Newaz, A.; Faruque, M.O. Forecasting of PV plant output using a hybrid wavelet-based LSTM–DNN model. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2019, 13, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, M.R.; Ni, Z. A new hybrid model for short-term electricity load forecasting. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 125413–125423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wei, Y.M.; Li, D.; Tan, Z.; Zhou, J. Short-term electricity load forecasting using a hybrid model. Energy 2018, 158, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, C.; Xie, X.; Zhang, G. Long short-term memory network-based hybrid model for short-term electrical load forecasting. Information 2018, 9, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagoke, M.D.; Ayeni, A.; Hambali, M.A. Short-term electric load forecasting using neural network and genetic algorithm. Int. J. Appl. Inf. Syst. 2016, 10, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudose, A.M.; Picioroaga, I.I.; Sidea, D.O.; Bulac, C.; Boicea, V.A. Short-term load forecasting using convolutional neural networks in COVID-19 context: The Romanian case study. Energies 2021, 14, 4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaffar, S.; Afshari, A. Short-term load forecasts using LSTM networks. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 2922–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, S.; Shan, D.; Gong, W. A short-term load forecasting model of LSTM neural network considering demand response. Complexity 2021, 598267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robati, F.N.; Iranmanesh, S. Inflation rate modeling: Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system and particle swarm optimization approach. MethodsX 2020, 7, 101062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Li, L. Modelling a combined method based on ANFIS and neural network improved by differential evolution algorithm for short-term electricity demand forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 2016, 49, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagias, V.D.; Zacharia, P.; Tempeloudis, A.; Stergiou, C. Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system-based predictive modeling of mechanical properties in additive manufacturing. Machines 2024, 12, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, S.; Chauhan, S.S.; Kumar, V. A review on genetic algorithm: Past, present, and future. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 8091–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.; Panda, S.K.; Mishra, D.P. Short-term load forecasting using genetic algorithm. In Computational Intelligence in Data Mining; Behera, H., Nayak, J., Naik, B., Abraham, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santra, A.S.; Lin, J. Integrating long short-term memory and genetic algorithm for short-term load forecasting. Energies 2019, 12, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozerdem, O.C.; Ebenezer, O.; Olaniyi, E.O.; Oyedotun, O.K. Short-term load forecasting using particle swarm optimization neural network. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 120, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafi, Z.S.; Afrakhte, H. Short-term load forecasting using neural network and particle swarm optimization algorithm. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 598267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.-Y.; Chan, Y.-H. Short-term electric load forecasting using particle swarm optimization-based convolutional neural network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126, 106773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, Z.M.; Shareef, H. Comparison of decision tree-based ensemble methods for prediction of photovoltaic maximum current. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2022, 16, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Raza, B.; Hussain, L.; Aldweesh, A.; Omare, A.; Khan, M.S.; Elding, E.T.; Nadim, M.A. Deep learning ResNet101 and ensemble XGBoost algorithm with hyperparameter optimization for lung cancer prediction. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 37, 2166222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahajjam, M.A.; Licea, D.B.; Ghogho, M.; Kobbane, A. Experimental investigation of variational mode decomposition and deep learning for short-term multi-horizon residential electric load forecasting. Appl. Energy 2022, 326, 119963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomiretskiy, K.; Zosso, D. Variational mode decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2014, 62, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.E. Summarizing multiple aspects of model performance in a single diagram. J. Geophys. Res. 2001, 106, 7183–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematics of typical CNN model structure.

Figure 1.

Schematics of typical CNN model structure.

Figure 2.

Fundamental structure of LSTM model.

Figure 2.

Fundamental structure of LSTM model.

Figure 3.

The structure of the ANFIS network.

Figure 3.

The structure of the ANFIS network.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the general framework of GA solution search.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the general framework of GA solution search.

Figure 5.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm.

Figure 5.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm.

Figure 6.

Structure of the XGBTE search and prediction algorithm.

Figure 6.

Structure of the XGBTE search and prediction algorithm.

Figure 7.

Flowchart of the algorithm for the integrated CNN-LSTM Model.

Figure 7.

Flowchart of the algorithm for the integrated CNN-LSTM Model.

Figure 8.

Flowchart of the algorithm for the integrated CNN-XGB Model.

Figure 8.

Flowchart of the algorithm for the integrated CNN-XGB Model.

Figure 9.

Flow chart of ANFIS-PSO algorithm.

Figure 9.

Flow chart of ANFIS-PSO algorithm.

Figure 10.

Flowchart of ANFIS-GA algorithm.

Figure 10.

Flowchart of ANFIS-GA algorithm.

Figure 11.

Normalized hourly aggregated demand profile for one week (December 2023).

Figure 11.

Normalized hourly aggregated demand profile for one week (December 2023).

Figure 12.

Statistical distribution of the data.

Figure 12.

Statistical distribution of the data.

Figure 13.

Correlation heat map of the variables.

Figure 13.

Correlation heat map of the variables.

Figure 14.

Results of the model training and testing (a) Training and testing of the ANFIS-PSO Model; (b) Training and testing of the ANFIS- GA Model; (c) Training and testing of the CNN-LSTM Model; (d) Training and testing of the CNN- XGB Model.

Figure 14.

Results of the model training and testing (a) Training and testing of the ANFIS-PSO Model; (b) Training and testing of the ANFIS- GA Model; (c) Training and testing of the CNN-LSTM Model; (d) Training and testing of the CNN- XGB Model.

Figure 15.

Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) of load signal.

Figure 15.

Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) of load signal.

Figure 16.

Results of the model training and testing with load data decomposition (a) Training and testing of the ANFIS-PSO-VMD Model; (b) Training and testing of the ANFIS- GA -VMD Model; (c) Training and testing of the CNN-LSTM-VMD Model; (d) Training and testing of the CNN- XGB-VMD Model.

Figure 16.

Results of the model training and testing with load data decomposition (a) Training and testing of the ANFIS-PSO-VMD Model; (b) Training and testing of the ANFIS- GA -VMD Model; (c) Training and testing of the CNN-LSTM-VMD Model; (d) Training and testing of the CNN- XGB-VMD Model.

Figure 17.

Radar plots of the performance metrics for the hybrid models assessed.

Figure 17.

Radar plots of the performance metrics for the hybrid models assessed.

Figure 18.

Taylor plots of the training and testing data.

Figure 18.

Taylor plots of the training and testing data.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |