I. Introduction

Multi-agent systems are increasingly deployed in scenarios where a single robot or controller is not enough: warehouse fleets, aerial swarms, cooperative manipulation, and distributed sensing. What makes these settings challenging is not just scale, but non-stationarity—the world changes, tasks change, and even the team changes. Multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) has become a practical tool for learning cooperative policies in such settings, yet field deployment is still blocked by three recurring issues: (i) coordination under partial information and unreliable communication, (ii) structured missions that unfold as ordered subtasks rather than one homogeneous objective, and (iii) safety constraints that must hold at every instant, independent of how learning evolves.

Recent surveys summarize why MARL remains difficult in real control systems: agents face non-stationary training targets, credit assignment ambiguity, and exploding joint action spaces, especially under continuous control and partial observability [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In practice, teams are often asked to do missions that are naturally

sequential: “reach an assembly site, form up, then encircle a moving target, then transport an object.” A single reward for the whole episode tends to produce brittle behaviors, since it obscures which subgoal is currently active and how earlier decisions constrain later feasibility. Task decomposition has therefore re-emerged as a central theme—breaking global objectives into smaller pieces can reduce variance, improve exploration, and provide clearer learning signals [

2,

5,

6,

7]. However, many task-decomposition approaches assume centralized training and smooth stationary conditions. They also rarely encode the explicit

precedence constraints that engineers routinely specify in mission planners.

A second bottleneck is communication. Cooperative control frequently relies on neighbor information, but real networks are bandwidth-limited and intermittent. Event-triggered communication is a natural fit: send messages only when something important changes. In MARL contexts, event-triggered communication can be learned or designed, and it often reduces communication load without collapsing performance [

3]. Nonetheless, simply reducing communication is not enough; the controller still needs a principled way to remain stable and safe when messages are delayed or absent.

Safety is the third and most rigid constraint. Collision avoidance, formation constraints, and actuator saturation cannot be “mostly satisfied.” This pushes us toward

safety filters or certificates that can wrap learning-based policies. Predictive safety filters provide one path: a nominal input proposed by learning is modified to satisfy constraints, using model predictive formulations and uncertainty margins [

4]. Another increasingly common approach uses certificates such as control barrier functions (CBFs) that enforce forward invariance of safe sets. A large body of recent work studies how to combine learning with barrier certificates in a way that scales to many agents and remains decentralized [

5]. In MARL, decentralized barrier shields have been proposed to preserve local execution even when centralized shielding is infeasible [

6]. Yet a gap remains between these safety mechanisms and

structured sequential missions: safety must hold while the team transitions across subtasks, sometimes under abrupt environmental changes.

Sequential missions introduce another subtle issue: coordination policies often need to respect ordering and timing. Logic- and automata-based views of tasks offer formal structure: temporal logic specifications can encode ordered requirements and constraints, and learning can be guided to satisfy them even in unknown environments [

7]. But logic-guided MARL can become heavy if it requires global automata products or centralized belief. In many robotics deployments, engineers prefer something lighter: a

task graph with precedence and time windows, and a learning/control stack that can adapt online.

Meanwhile, robustness to disturbances and model mismatch is not optional. Wind gusts affect UAV swarms; friction and payload changes affect ground robots; sensing may degrade. Robust control ideas are therefore essential, but pure robust control usually demands accurate bounds and conservative tuning. Recent work in robust safe multi-agent reinforcement learning integrates robust neural CBFs with learning to handle uncertainties in a decentralized way [

13]. However, such methods typically focus on a single task type (e.g., collision avoidance) rather than ordered missions with changing coordination modes.

This paper targets the intersection of these needs: sequential mission structure, distributed online adaptation, and safety-aware coordination under uncertainty. The key idea is to connect a global objective to an ordered set of subtasks through a directed task graph, and then allow each agent to adapt online while a coordination controller guarantees constraints. We are motivated by formation tracking, encirclement, and cooperative transport, where the mission naturally unfolds in stages and where safety cannot be compromised.

A related practical constraint is that fully centralized controllers are often fragile. They can become computational bottlenecks and single points of failure. Centralized training with decentralized execution is a common compromise, but online deployment still benefits from learning rules that are truly distributed, updating from local data. Distributed actor–critic designs that use neighbor messages provide an appealing template, especially when paired with event-triggered communication to avoid constant chatter. In this work, we also explicitly include robust compensation terms in the controller to counter time-varying disturbances.

We evaluate our approach on three representative scenarios. First,

multi-robot formation tracking under time-varying disturbances tests steady coordination and constraint satisfaction. Second,

dynamic target encirclement tests rapid switching and non-stationary objectives. Third,

cooperative payload transportation tests coupled dynamics and communication efficiency, a setting that has recently motivated event-triggered deep RL designs [

9,

10]. Across these scenarios, we compare with centralized controllers and fixed-gain coordination baselines, as well as safe-MARL variants that do not exploit sequential task structure.

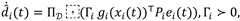

Sequential cooperation via task graphs: We introduce a lightweight sequential cooperation model that encodes precedence relations, activation logic, and time-window constraints for heterogeneous agents, bridging mission planning and online learning.

Distributed online actor–critic learning: We develop an online learning scheme that updates policies using local observations and neighbor messages, compatible with partial information and non-stationary disturbances.

Safety-aware adaptive coordination: We design an adaptive coordination controller with event-triggered communication, robust compensation, and explicit constraints for formation keeping, collision avoidance, and input saturation using a minimally invasive safety-filter formulation.

Stability and performance evidence: We provide Lyapunov-based boundedness analysis and simulation evidence showing improved success rates and robustness compared with centralized and static cooperation strategies.

III. Experiment

This section evaluates the proposed sequential cooperative online learning + safety-aware coordination framework on three representative multi-robot missions: (i) formation tracking, (ii) dynamic target encirclement, and (iii) cooperative payload transportation. All experiments are conducted in simulation with bounded disturbances, partial observations, and switching regimes to emulate non-stationary field conditions.

A. Simulation Environment and Agent Models

We simulate agents moving in a planar workspace with static obstacles and a time-varying disturbance field. Each agent follows uncertain control-affine dynamics (Section II) with additive disturbances that switch between regimes every 15–25 s (randomized per run). Regimes differ in magnitude and direction bias to model wind-like or traction-like effects. Agents sense local states (position/velocity) within a limited radius and do not have access to global state.

Communication follows a proximity graph: an edge exists if . Messages contain compact neighbor features (position/velocity or learned embeddings). For the proposed method, messages are sent only when the event-trigger condition in (17) is satisfied; baselines use periodic communication.

B. Tasks and Sequential Stages

We define each mission as an ordered set of subtasks encoded by a task graph . Stage activation follows the precedence rule in (10), and the reward is stage-focused per (11).

Formation Tracking (FT).

Stages: assemble → track. Agents first rendezvous around a reference centroid, then maintain a desired formation while following a moving reference trajectory. Completion of “assemble” is defined by a formation residual threshold . “Track” is evaluated by formation error and smooth control.

Dynamic Target Encirclement (DTE).

Stages: approach → encircle → maintain. A target moves with random acceleration changes. Agents must reach an annulus around the target and distribute uniformly in angle. Stage completion uses radius error and angular spacing residuals.

Cooperative Payload Transportation (CPT).

Stages: approach → attach → transport. Agents coordinate to move a payload through a corridor with obstacles. Disturbances include payload mass variation and intermittent friction changes. Completion requires reaching the goal region without violating separation or saturation constraints.

C. Baselines and Implementation Details

We compare against four baselines:

B1: Fixed-gain coordination + heuristic avoidance. Classical formation controller with a repulsive collision term and hand-tuned gains.

B2: Centralized MPC/DMPC. Full-state planner/controller with periodic updates and shared information (serves as a strong model-based reference).

B3: Centralized actor–critic (CTDE). Centralized critic and periodic communication, with decentralized execution.

B4: Safe MARL (single-stage). Same actor–critic backbone and QP safety filter, but no task-graph sequencing (single global reward).

Ours uses: task-graph sequencing + distributed online actor–critic + event-triggered communication + QP safety filter (CBF/CLF constraints) + robust/adaptive compensation.

All learning methods run for the same interaction budget and are evaluated under identical disturbance schedules. Each reported metric averages over 200 independent runs (different random seeds, obstacle placements, disturbance schedules, and initial conditions).

D. Metrics

We report:

Success Rate (%): fraction of runs completing all subtasks within the horizon.

Convergence Time (s): time to satisfy the final stage residual below threshold.

Safety Violations: collision count and hard constraint breaches (should be 0 for safe methods).

Communication Load: messages per agent per second.

Control Effort: , used as a secondary efficiency indicator.

Table 1 summarizes the core parameters used across tasks.

E. Main Results

Table 2 reports the aggregate results across the three missions (averaged over tasks and agent counts, 200 runs). The proposed method achieves the highest completion rates, the shortest completion times, and maintains strict safety.

Two patterns are consistent across tasks. First, sequencing matters most in DTE and CPT. The single-stage safe MARL baseline often learns actions that are good for “getting close” but not good for stable completion. The task graph reduces this ambiguity by switching objectives at the right moment. Second, the QP safety filter prevents catastrophic exploration. Even when the learned policy is still adapting, collisions remain at zero.

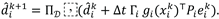

F. Robustness Under Regime Switching

To isolate robustness, we vary the normalized disturbance magnitude and keep the regime-switch schedule.

Figure 2 shows success rate trends as disturbances intensify. The proposed method degrades gradually, while fixed-gain and single-stage baselines drop sharply once disturbances exceed their effective tuning envelope.

A. Gblation Study

We evaluate which components contribute most by removing one element at a time from the proposed method, shown in

Table 3.

H. Discussion of Practical Takeaways

The experiments suggest three practical takeaways. First, explicit sequential structure improves reliability for missions that require stable stage transitions (encircle, then maintain; attach, then transport). Second, event-triggering offers a clean bandwidth–performance trade: it cuts communication by roughly a factor of three without hurting completion. Third, coupling online learning with a safety filter yields stable behavior early, before the policy fully converges, which is essential when the environment changes mid-run.