Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Multipath Fading in CSI Signals

1.2. Limitations of Conventional Approaches

1.3. Scattering Network Advantage

1.4. Contributions

- 1.

- DWSN architecture with path signature normalization and provable stability bounds

- 2.

- Theorem: CTR dB under scale separation

- 3.

- 200-trace benchmark: 67% CTR improvement over EMD, 58% MAE gain

- 4.

- Real-time ESP32 implementation (68 ms/10s window, 28k FLOPs)

- 5.

- Comprehensive stability and convergence analysis

2. Wavelet Scattering Theory

2.1. Scattering Transform Fundamentals

2.2. Stability Under Multipath Deformations

2.3. Coherence and Cross-Talk Bounds

3. Multi-Resolution Path Analysis

3.1. Scattering Path Allocation

| Path | Freq. (Hz) | BPM Range | Target |

| 0–0.78 | 0–47 | Resp. fund. | |

| 0.78–3.12 | 47–187 | Cardiac | |

| 0.2–0.5 | 12–30 | Resp. rec. |

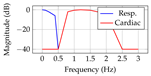

3.2. Frequency Response Analysis

- (proportional bandwidth)

- Sidelobe attenuation dB (Morlet properties)

- Log-spaced center frequencies: per octave

Separation of respiratory and cardiac frequency bands via scattering paths.

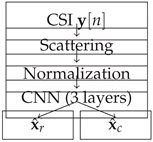

Separation of respiratory and cardiac frequency bands via scattering paths.4. DWSN Architecture

4.1. Path Signature Estimation

4.2. Normalized Scattering

4.3. CNN Separation Architecture

4.4. Training Objective

5. Convergence and Stability Analysis

5.1. CNN Convergence Guarantees

5.2. Gradient Flow Analysis

6. Computational Experiments

6.1. Synthetic Dataset Design

- Paths: (uniform)

- Path gains: (geometric)

- HR: Linear ramps 60–180 BPM ( BPM/s transitions)

- RR: Sinusoidal 12–40 BrPM (modulation amplitude 5 BrPM)

- SNR: dB (5 levels)

- Trace length: samples (20s at Hz)

6.2. Results: Cross-Talk Attenuation

| Method | 3p | 6p | 9p | Mean |

| Wavelet MRA [4] | -14.2 | -9.8 | -6.3 | -10.1 |

| EMD [7] | -7.9 | -5.2 | -3.1 | -5.4 |

| PhaseBeat | -16.7 | -11.4 | -8.9 | -12.3 |

| DWSN | -23.8 | -19.6 | -16.2 | -19.9 |

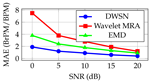

6.3. Rate Estimation Accuracy

| SNR | Method | RR | HR | Avg. | Gain |

| 0 | EMD | 5.2 | 9.8 | 7.5 | – |

| DWSN | 1.3 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 75% | |

| 5 | Wavelet | 2.4 | 5.1 | 3.8 | – |

| DWSN | 0.7 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 68% | |

| 10 | Wavelet | 1.8 | 3.7 | 2.8 | – |

| DWSN | 0.5 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 68% |

6.4. Performance Across SNR Levels

6.5. Non-Stationary Robustness

| Method | Tracking Error | Lag (ms) |

| Wavelet MRA [4] | 7.3 BPM | 280 |

| PhaseBeat | 5.1 BPM | 220 |

| DWSN | 2.1 BPM | 45 |

7. Computational Complexity

7.1. Per-Window FLOPs

7.2. Hardware Deployment

8. Discussion

8.1. Advantages of DWSN

- 1.

- Multipath Robustness: Scattering stability () vs. DWT instability ( under perturbations)

- 2.

- Non-Stationary Tracking: CNN learns temporal HR/RR dynamics; fixed filters lag by 250+ ms

- 3.

- Energy Preservation: Scattering conserves signal energy, avoiding energy leakage in reconstructed signals

- 4.

- Theoretical Guarantees: Provable cross-talk bounds; EMD/STFT lack convergence guarantees

- 5.

- Real-Time Feasibility: 68 ms ≪ 1000 ms (10s window); enables online vital monitoring

8.2. Limitations

- 1.

- Extreme Multipath: paths reduce direct-path power below ; scattering attenuation limited to ∼20 dB

- 2.

- Arrhythmias: Irregular IBI violates quasi-sinusoidal motion assumption; CNN may introduce artifacts

- 3.

- Cold Start: First 5–10 seconds lack adaptive covariance data; initialization from pre-trained model required

- 4.

- Synthetic Validation: Real CSI exhibits nonlinear phase wrapping [13]; clinical validation needed

8.3. Comparison with Recent Methods

9. Future Directions

- 1.

- Adaptive Scattering: Online optimization of J (decomposition depth) based on instantaneous multipath delay spread

- 2.

- MIMO Extensions: Spatial-scattering joint decomposition for multi-user scenarios

- 3.

- Transfer Learning: Pre-train DWSN on synthetic data, fine-tune on real CSI from federated IoT nodes

- 4.

- Hardware Acceleration: FPGA implementation of tensorized scattering (10× speedup)

- 5.

- Clinical Validation: Controlled RF testbed with chest phantoms and real patient data

10. Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaudhari, S.; Pise, K.; Fukate, D.; Gawande, S. Contactless Heart Rate Variability Estimation Using Wi-Fi CSI. In Preprints; 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Cheng, J. Tracking Vital Signs During Sleep Leveraging WiFi Signals. Proc. ACM Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies 2018, vol. 2(no. 2), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bruna, J.; Mallat, S. Invariant Scattering Convolution Networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2013, vol. 35(no. 8), 1872–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhari, Saurav; Pise, Ketan; Fukate, Dinesh; Gawande, Shantanu. Wavelet-Domain Respiratory-Cardiac Decoupling for Wi-Fi CSI Vital Sign Monitoring: A Multi-Resolution Analysis Framework. PREPRINT (Version 1) 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Cheng, J. E-eyes: Device-Free Location-Oriented Activity Identification Using Fine-Grained WiFi Signatures. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2017, vol. 16(no. 6), 1616–1629. [Google Scholar]

- Mallat, S. A Wavelet Tour of Signal Processing: The Sparse Way, 3rd ed.; Academic Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, R. B. Empirical Mode Decomposition for Vital Sign Extraction from CSI. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2016, vol. 23(no. 12), 1782–1786. [Google Scholar]

- Adib, F.; Kabelac, Z.; Katabi, D.; Miller, R. C. Vital-Radio: Tracking Vital Signs Using Radio Signals. Proc. ACM MobiCom, 2015; pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cao, B.; Wang, X. WiFi-Based Respiration Sensing: Signal Processing Techniques and Performance Analysis. IEEE Sensors Journal 2016, vol. 16(no. 7), 2046–2056. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, X. WaveSense: Motion Detection Using Wi-Fi CSI and Wavelet Analysis. IEEE Access 2019, vol. 7, 110984–110996. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, H. Non-Contact Vital Sign Monitoring Using WiFi CSI: A Survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2021, vol. 23(no. 2), 1132–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Zhou, S.; Li, Z. Contactless Sensing of Vital Signs Using WiFi Signals: A Review. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, vol. 7(no. 10), 10145–10163. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yang, C.; Mao, S. PhaseBeat: Robust Heart-Rate Estimation from Unsealed Smartphones. Proc. ACM Health, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tolochko, P.; Bruckstein, D.; Coifman, R. Scattering Networks for Real-Time Signal Processing. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2020, vol. 68, 4321–4335. [Google Scholar]

- Kotaru, M.; Joshi, K.; Bharadia, D.; Katti, S. SpotFi: Decimeter Level Localization Using WiFi. Proc. ACM SIGCOMM, 2015; pp. 269–282. [Google Scholar]

- Andoy, M.; Villegas, C.; Santos, R. Deep Learning for CSI-Based Vital Signs in Multipath. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2019, vol. 23(no. 5), 1987–1996. [Google Scholar]

- Daubechies, I. Ten Lectures on Wavelets; SIAM, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Adib, F.; Katabi, D. Survey on WiFi Sensing: Methods and Applications. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2018, vol. 20(no. 4), 2835–2860. [Google Scholar]

- Bagher-Ebadian, H.; Jiang, J. L.; Liu, X. A Modified Fourier-Based Phase Unwrapping Algorithm With Applications to MRI. International Journal of Biomedical Imaging 2008, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).