1. Introduction

Human activity recognition (HAR) [

1] is a significant area of research in computer vision and pattern recognition that focuses on identifying and classifying human activities from multimedia environments. HAR can be achieved using various technologies, including camera-based [

2], sensor-based [

1], radar-based [

3], and Wi-Fi [

1,

4]. Camera-based HAR relies on video data to analyze and classify actions. While it offers high-resolution and detailed visual information, it raises privacy concerns and is sensitive to lighting conditions and occlusions. Sensor-based HAR utilizes wearable devices like accelerometers and gyroscopes to capture movement data, providing accuracy and robustness but requiring user compliance and can also be intrusive. Radar-based HAR uses radio waves to detect motion, offering privacy advantages and working well in low-light conditions, but it can be affected by interference and requires complex signal processing. In contrast, Wi-Fi-based HAR leverages the analysis of Channel State Information (CSI) to recognize actions by detecting changes in signal propagation caused by human movement. This method is advantageous for its non-intrusiveness, cost-effectiveness, and ability to work through walls and in various lighting conditions. However, Wi-Fi-based HAR may face challenges in environments with high signal noise and requires sophisticated algorithms to interpret the data accurately [

5,

6]. Wi-Fi-based HAR stands out due to its balance of privacy, convenience, and practicality in real-world applications.

In Wi-Fi sensing, two critical metrics are commonly used to represent the characteristics of a Wi-Fi signal: Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI) and Channel State Information (CSI) [

7,

8]. These signals can propagate and synthesize through either line-of-sight (LOS) or non-line-of-sight (NLOS) scenarios (

Figure 1). RSSI is a measure of the power level that a receiver detects from a transmitted signal, often used to estimate the distance between the transmitter and receiver. It provides a coarse measure of signal strength but lacks detailed information about the multipath effects and the fine-grained behavior of the signal [

8]. On the other hand, CSI offers a more comprehensive representation by capturing the amplitude and phase of the signal across multiple subcarriers within a Wi-Fi channel. This allows CSI to provide detailed insights into the propagation environment, including reflections, scattering, and the impact of obstacles [

7]. While RSSI is easier to obtain and requires less computational processing, CSI is preferred in advanced Wi-Fi sensing applications, such as human activity recognition and indoor localization, due to its ability to capture rich spatial and temporal information about the signal’s interactions with the environment.

Channel State Information (CSI) comprises multiple extractable features that reveal characteristics of the wireless environment, such as Time of Flight (ToF), amplitude, phase, Direction of Arrival (DoA), Angle of Arrival (AoA), and phase shift [

7]. Each feature provides unique information; for example, ToF enables precise distance estimation, while DoA and AoA are critical for identifying the signal's spatial direction. In Human Activity Recognition (HAR) applications, amplitude and phase are two particularly important features. Amplitude reflects the magnitude of signal variations, whereas phase provides detailed insights into signal propagation, including phase shifts caused by reflections and scattering. However, Wi-Fi sensing research has largely focused on the amplitude component of CSI, often neglecting phase information in the received signal. Additionally, CSI data is represented as a series of time-varying values across subcarriers. Most recognition models, however, concentrate on the temporal dimension and tend to overlook inter-subcarrier relationships, which could capture variations in body posture or actions, such as standing up and sitting down.

To address these gaps, this study seeks to utilize relevant features in conjunction with attention mechanisms across both temporal and channel dimensions, enhancing the accuracy and robustness of Wi-Fi-based applications for Human Activity Recognition (HAR). In summary, the primary contributions of this paper to Wi-Fi sensing for HAR are as follows:

We propose an attention-based model that optimally leverages both phase and amplitude components to improve HAR performance. Both features are input into temporal and channel attention mechanisms, allowing comprehensive data utilization across temporal and spatial domains.

We introduce a Gated Recurrent Network (GRN) architecture that integrates these attention mechanisms for both phase and amplitude signals, yielding more robust and accurate classification results.

Our model is rigorously tested on three datasets, including two publicly available datasets and our own, demonstrating superior accuracy and performance relative to existing state-of-the-art (SOTA) models.

2. Literature Review

The Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI), a metric used to measure transmission channel power, has been extensively studied and applied across various domains, including Human Activity Recognition (HAR) [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Despite its utility, RSSI's efficiency is constrained. In contrast, Channel State Information (CSI) offers a more comprehensive and detailed representation, providing a four-dimensional matrix that captures the characteristics of transmission and reception channels, subcarriers, and temporal packets. Due to its complexity, numerous studies have explored the application of CSI in HAR using advanced deep learning techniques, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and Transformer models.

As interest in Wi-Fi CSI methods continues to grow, numerous datasets containing CSI data have been developed for diverse applications. These datasets have become foundational for many researchers, serving as the basis for experimental studies documented in a wide range of published literature.

Table 1 provides an overview of commonly used public datasets and their descriptions, facilitating an understanding of their utility and scope.

2.1. Wi-Fi CSI Based on CNN and LSTM Approaches

The intricate features of CSI data, including phase and amplitude, have been effectively utilized in CNN models, yielding significant advancements. Wang et al. [

21] introduced a CSI-based human activity recognition and monitoring system (CARM), a CSI-based method for HAR and monitoring. This model integrates two modules: the CSI-speed module, which captures the relationship between CSI dynamics and human motion, and the CSI-activity module, which correlates movement speed with activity. By leveraging the phase component of CSI, the model was tested on their dataset and achieved 96% accuracy in HAR while demonstrating robustness across different environments. Although the method is accurate, cost-effective, and privacy-preserving when using standard Wi-Fi devices, it is sensitive to noise, impacts Wi-Fi performance, and demands extensive training.

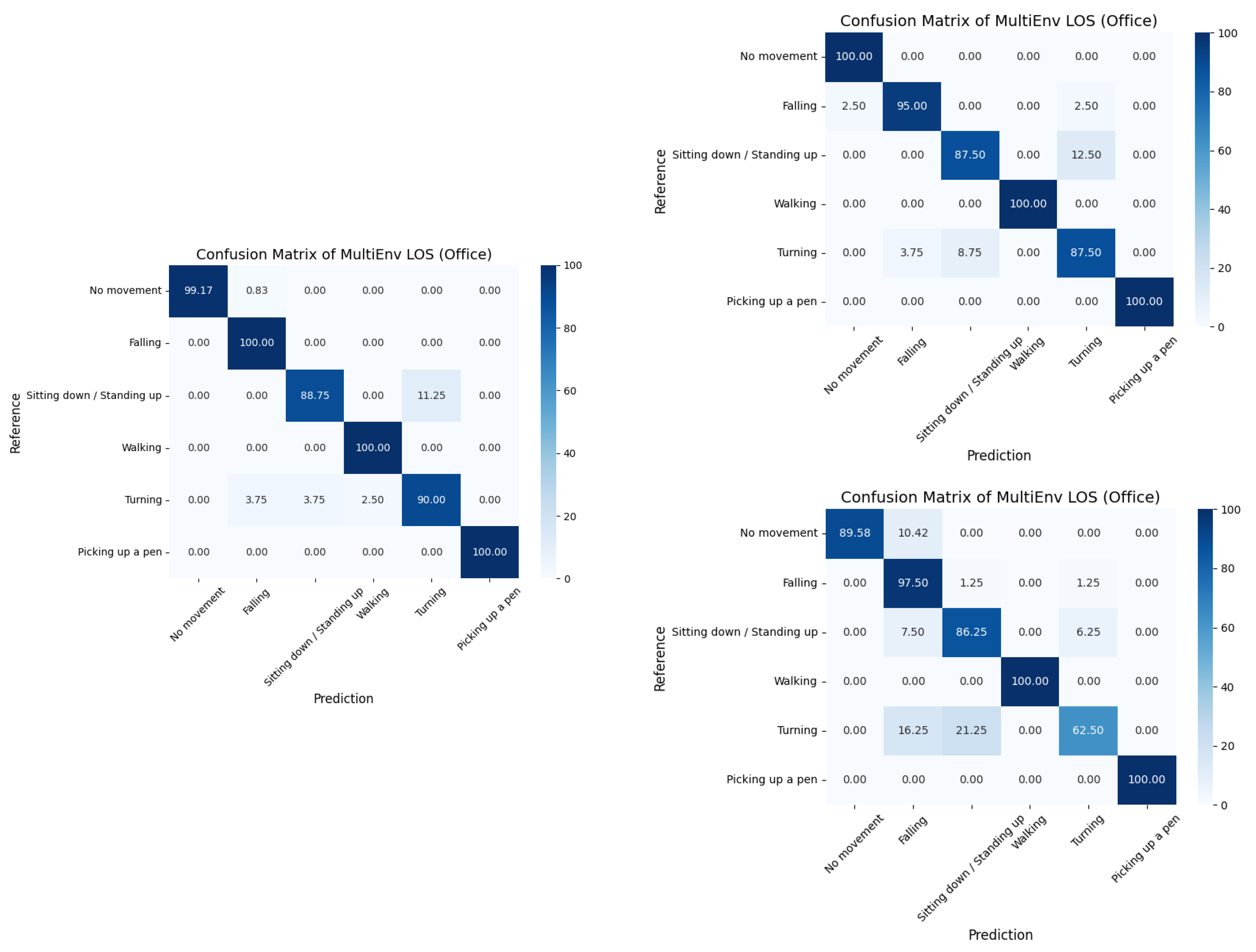

Similarly, Alsaify et al. [

15] proposed the MultiEnv dataset, evaluating system performance in office and hall environments under line-of-sight (LOS) and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) conditions. Their robust five-stage preprocessing and feature extraction pipeline achieved 91.27% accuracy on their dataset [

15,

22]. However, environmental factors such as distance and interference, as well as similar movement patterns (e.g., falling versus sitting), led to higher misclassification rates.

While CNN-based models demonstrate promising results, they lack the ability to exploit the temporal characteristics of CSI data. Consequently, temporal-based approaches utilizing LSTM networks have gained attention. For example, Chen et al. [

23] developed the ABLSTM model (attention-based bidirectional LSTM), designed to extract representative temporal features from sequential CSI data in both directions. The ABLSTM framework achieved state-of-the-art accuracy (≥95%) in Wi-Fi CSI-based HAR, evaluated on the StanWiFi dataset and their own dataset, by integrating bidirectional LSTM and attention mechanisms. However, this model requires significant computational resources, faces challenges in cross-environment scenarios, and does not address multi-user activity recognition.

Yadav et al. [

24] proposed CSITime, an enhanced version of the Inception-Time network, which achieved state-of-the-art accuracies across three public datasets: 98.2% on ARIL, 98.88% on StanWiFi, and 99.09% on SignFi. CSITime incorporates data augmentation and advanced optimizations within a streamlined Inception-Time-based architecture. However, the model faces challenges in high-interference environments and multi-user scenarios while demanding high computational resources.

To address spatial and temporal aspects of CSI data, several studies have combined CNN and LSTM architectures. For instance, Moshiri et al. [

25] employed Raspberry Pi devices to extract amplitude CSI signals for seven activities, converting them into 2D images using pseudo-color plots. Among four evaluated models (1D-CNN, 2D-CNN, LSTM, and bidirectional LSTM), the 2D-CNN achieved 95% accuracy on their collected data. Similarly, Salehinejad and Valaee [

26] introduced LiteHAR, which uses randomly initialized convolution kernels for feature extraction, achieving 93% accuracy on the StanWiFi dataset. Shalaby et al. [

27] compared deep learning models on the StanWiFi dataset, with a CNN-GRU model achieving 99.31% accuracy and its attention-based variant reaching 99.16%. Recently, Islam et al. [

28] proposed the STC-NLSTMNet model (spatio-temporal convolution with nested long short-term memory), integrating spatio-temporal convolution and nested LSTMs, achieving 99.88% and 98.20% accuracy on public datasets (StanWiFi and MultiEnv). This model is a robust and efficient method for HAR, achieving SOTA performance by integrating spatial and temporal features. However, the model has limitations in NLOS environments and multi-user settings.

2.2. Transformer-Based Approaches

Traditional models such as CNNs and LSTMs are limited in capturing interdependencies within the same data dimension. In recent years, Transformer models have gained prominence due to their multi-head attention mechanism [

29]. Researchers have applied these models to Wi-Fi-based HAR systems with notable success.

Ding et al. (2022) introduced a Channel–Time–Subcarrier Attention Mechanism (CTS-AM) to enhance location-independent HAR. This system achieved more than 90% average accuracy on their dataset across various locations with limited training samples [

30]. Yang et al. (2023) proposed WiTransformer, which adapts two Transformer architectures—United Spatiotemporal Transformer (UST) and Separated Spatiotemporal Transformer (SST)—to improve recognition accuracy and robustness in complex environments [

31]. They experimented on the Widar 3.0 dataset and achieved an overall recognition accuracy of 86.16%.

Some studies also explored two-way relationships within CSI data. Li et al. (2021) [

32] developed the THAT model, which uses a dual convolution-augmented HAR layer to capture channel and temporal structures. This model effectively accommodates variations in activity speed and blank intervals using Gaussian encoding. Yang et al. (2023) [

19] applied Vision Transformers (ViT) to Wi-Fi sensing tasks, leveraging spatial and temporal features to handle complex data relationships. However, ViT models require substantial training data for optimal performance.

Most studies process CSI signals by focusing on either phase or amplitude components, which may limit their ability to fully capture human activity complexities. To address this limitation, we propose a novel model that integrates both amplitude and phase information in a two-dimensional framework (spatial and temporal), aiming to enhance the accuracy and robustness of activity recognition.

2. Materials and Methods

3.1. Channel State Information (CSI)

Channel State Information (CSI) refers to the detailed knowledge of the properties of a communication channel in wireless communication systems. CSI encompasses information about the channel’s characteristics, including path loss, fading, delay spread, and interference [

33]. CSI is typically obtained through channel estimation techniques, which involve measuring the channel response to known pilot signals transmitted between the sender and receiver. Mathematically, CSI can be represented by the channel matrix

, which characterizes the effect of the channel on the transmitted signal. If

x is the transmitted signal and

y is the received signal,

N is the total number of subcarriers, and

represents the noise in the system, the relationship between

x and

y for each

i-th subcarrier can be expressed as follows (1):

The matrix

presents the relations from transmitter (

T) and receiver (

R) as (2):

where each

contains complex values represented as shown in (3):

Each

hrt value consists of both the real

and imaginary

parts, which encapsulate the amplitude and phase changes imposed by the channel. The amplitude (

and phase (

are calculated as given in equations (4) and (5):

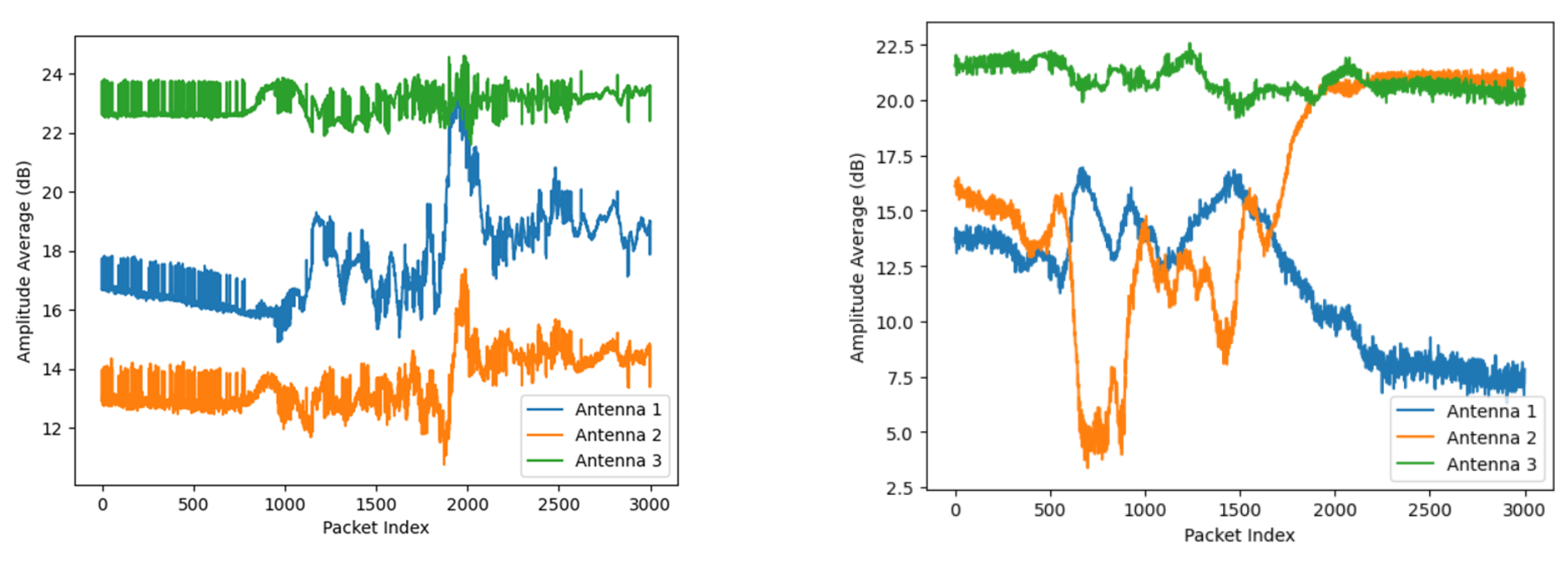

An example visualization of falling and sitting down activities, represented by the averaged amplitude and phase values of Wi-Fi Channel State Information (CSI), is shown in

Figure 2.

3.2. Datasets

In our experiment, we selected and evaluated three datasets: MultiEnv (three environments) [

15], StanWiFi [

16], and a dataset collected by our research team. The rationale for selecting these datasets was their inclusion of both CSI phase and amplitude values, which are critical for the model's ability to effectively utilize these inputs.

3.2.1. StanWiFi

The StanWiFi dataset was collected by Yousefi et al. (2017) [

16] in a line-of-sight (LOS) environment. The setup included a single Wi-Fi router with one antenna as the transmitter and three antennas as the receiver, installed on a laptop equipped with an Intel® 5300 NIC. The transmitter and receiver were three meters apart. Each session, recorded at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz, lasted 20 seconds. This dataset consists of six activities—fall, run, lie down, walk, sit down, and stand up—performed by six participants, each repeating them 20 times. In total, the dataset comprises 577 samples.

3.2.2. Multiple Environment (MultiEnv)

The MultiEnv dataset was collected by Alsaify et al. (2017) [

15] across three indoor environments: an office and a hall for line-of-sight (LOS) scenarios, and a non-line-of-sight (NLOS) scenario with a wooden barrier separating the transmitter and receiver. The distance between the transmitter and receiver was set at 3.7 meters, with an eight-centimeter wall as the barrier. Data was collected using two computers: one serving as a single-antenna transmitter and the other as a three-antenna receiver, both equipped with an Intel® 5300 NIC. As listed in

Table 2, the dataset includes six activity classes, with a total of 3,000 samples (30 subjects × 5 experiments × 20 trials).

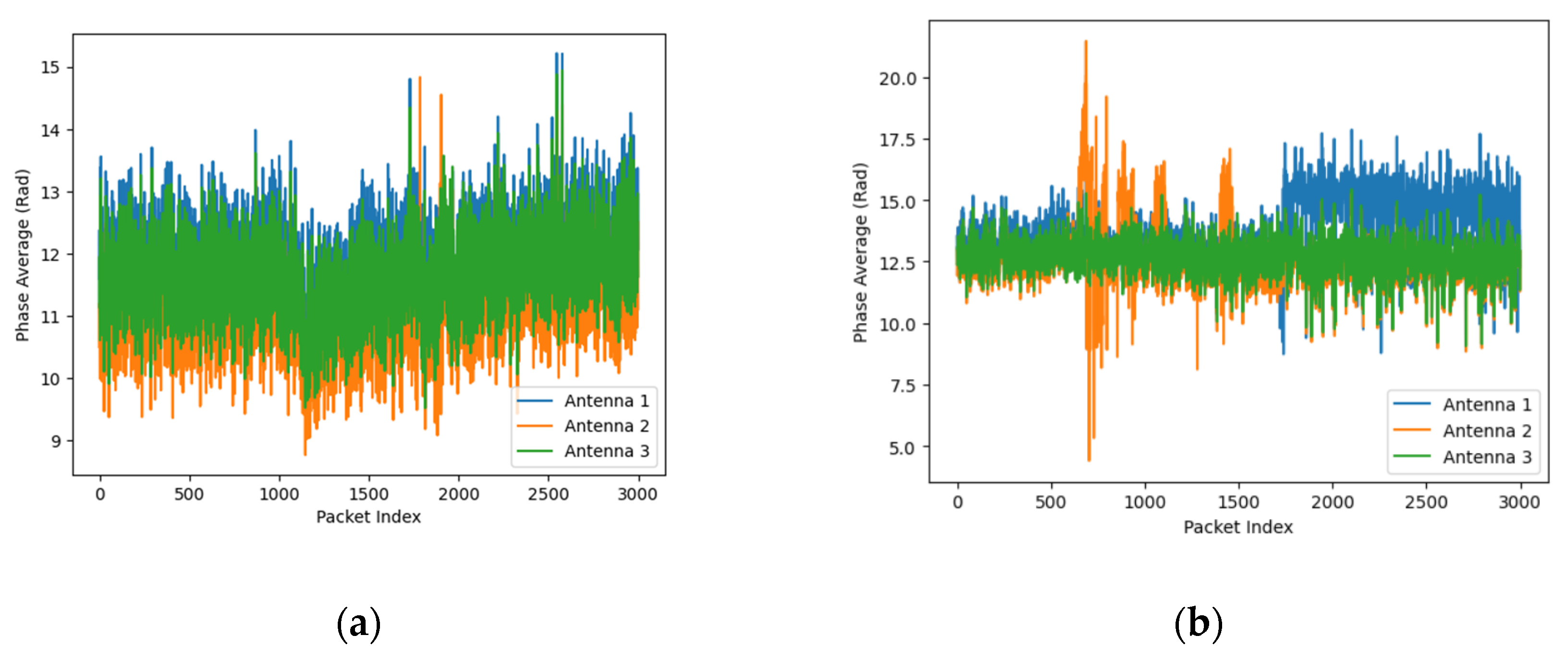

3.2.3. Our Research Team Dataset (MINE Lab Dataset)

This dataset was collected in an office (LOS) within our laboratory (5.5 x 3 m). The setup utilized Intel® 5300 NIC devices, each equipped with three antennas for both the transmitter and receiver, placed 4.0 meters apart (

Figure 3). The experiment involved five participants performing six activities: standing up and squatting, raising and lowering the right hand, opening and closing the arms, kicking the right and the left leg. In total, the dataset comprises 216 collected samples.

3.3. Methods

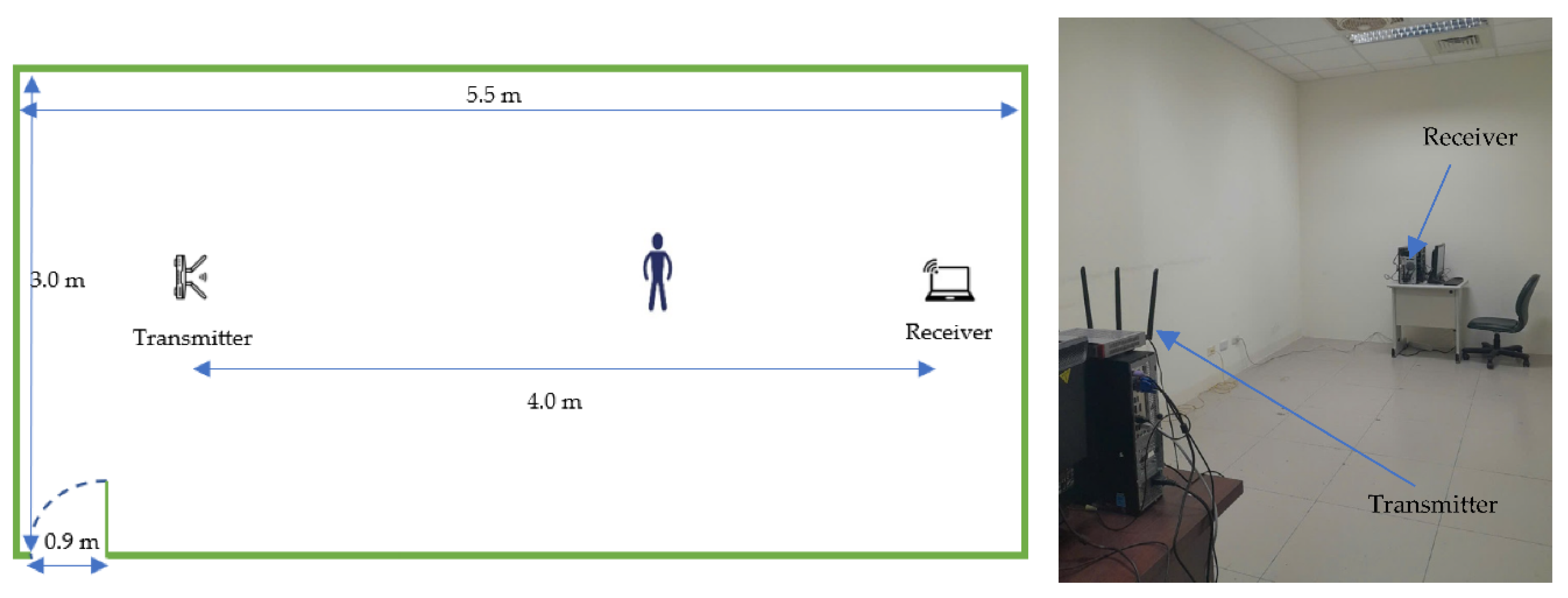

Figure 4 illustrates a pipeline of the proposed HAR system in this paper. It begins with raw CSI data, which undergoes preprocessing steps including Kalman filtering [

34], sliding windows (optional), time alignment, and feature extraction. After preprocessing, the CSI data is extracted into two components: amplitude and phase. The amplitude data is normalized, while the phase data is unwrapped, and both features are passed through four Multi-scale Convolution Augmented Transformer (MCAT) layers [

32]. Each MCAT layer processes data along two streams: the data is kept in its original format for the temporal stream, while it is transposed to feed into the channel stream. Gaussian Range Encoding is applied to preserve temporal order. The outputs of the MCAT layers are combined using a CNN with max-pooling layers. The combined outputs are then subsequently fed into a Gate Residual Network (GRN) [

35,

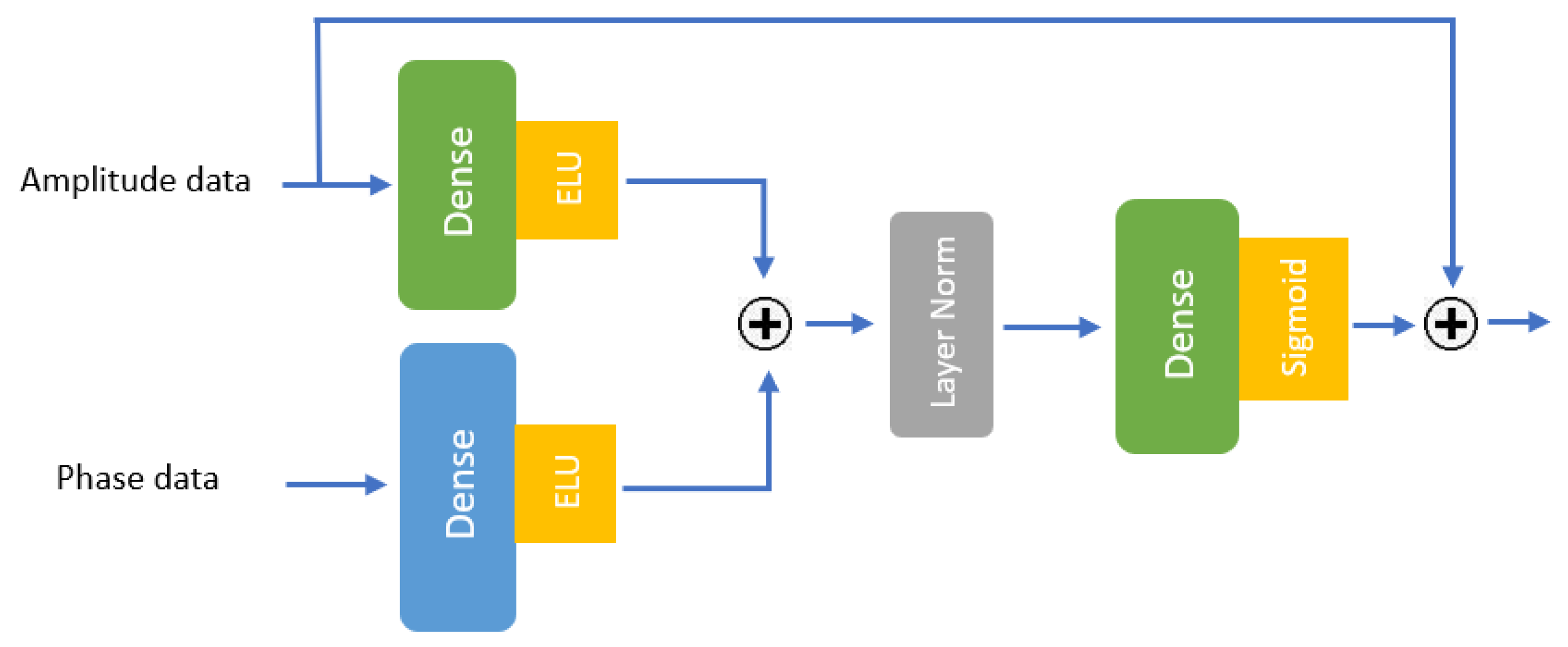

36], which includes dense layers with ELU activations, layer normalization, and a final sigmoid activation. The GRN integrates the processed amplitude and phase features to classify human actions. This system effectively enables the classification of human activities from CSI Wi-Fi signals as they interact with their environment.

3.3.1. Preprocessing: Kalman Filter

The Kalman filter is a recursive algorithm that efficiently estimates the state of a dynamic system from a series of noisy measurements [

34], to minimize

η, as described in Equation (1). It operates in two main phases: prediction and update. During the prediction phase, the filter uses the system’s previous state and a mathematical model to predict the next state, while also estimating the associated uncertainty. In the update phase, it updates the estimate by incorporating new measurements and reducing uncertainty based on the discrepancy between the predicted and observed data. The Kalman filter assumes that the errors in both the system and the measurements are normally distributed, following a Gaussian distribution, making it optimal for linear systems affected by Gaussian noise.

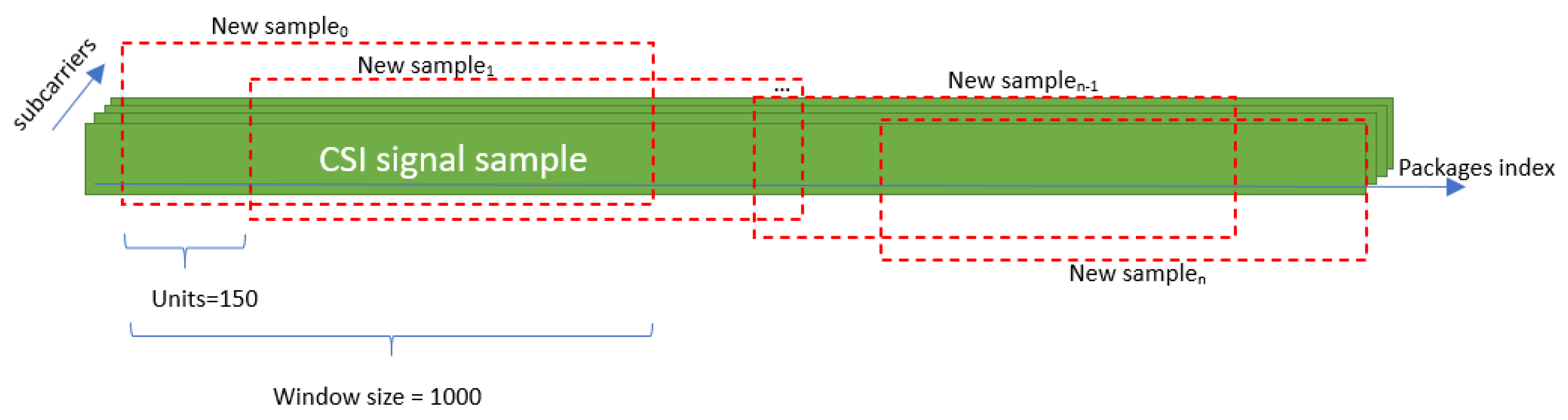

3.3.2. Preprocessing: Sliding Windows

In this phase, appropriate preprocessing techniques are applied to the collected CSI data depending on the characteristics of each dataset. For both the StanWifi dataset and our own dataset, we use a sliding window approach to generate additional samples, which is also essential for real-time action prediction when the exact point at which the action will occur within the signal is unknown (

Figure 5). Specifically, each instance is shifted by 150, and a window size of 1000 is used for each sample. As a result, the data augmentation process leads to an expansion of the StanWifi dataset from 577 records to 3119 records, while our dataset increases from 216 samples to 2111 samples.

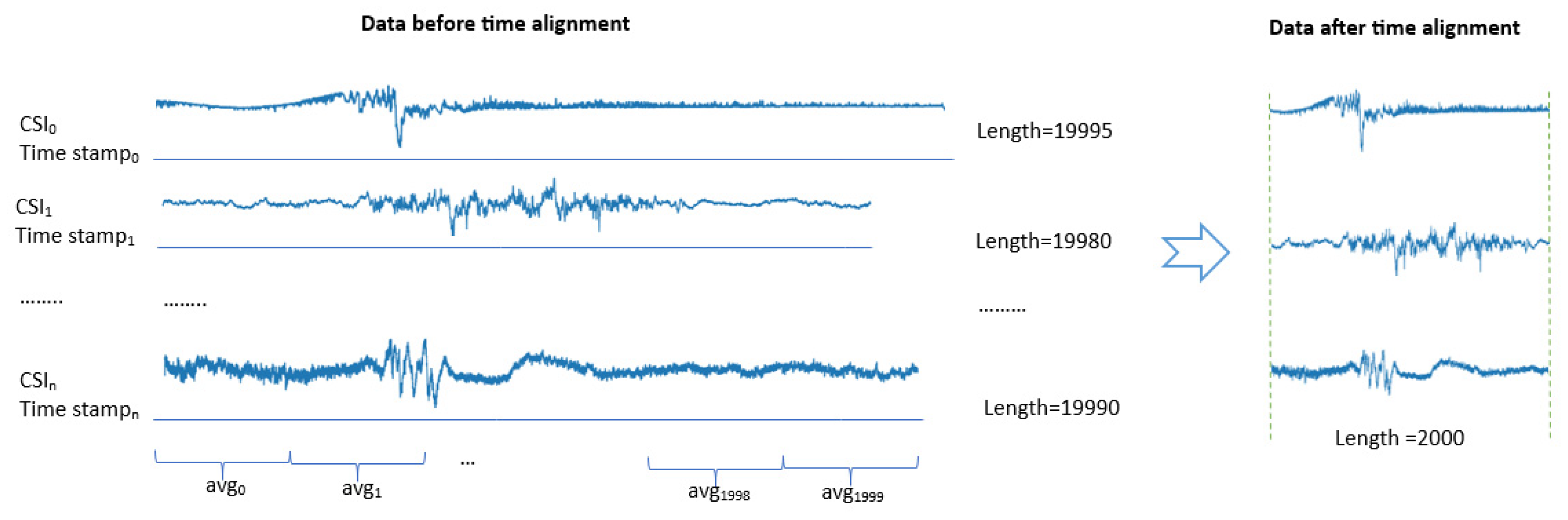

3.3.3. Preprocessing: Time Alignment

In the datasets, CSI signal sample lengths vary, and the signals exhibit high density with similar characteristics. To address this issue, we propose a time alignment algorithm designed to standardize the sample sizes using collection times and average signal values. This algorithm processes CSI data based on timestamps, normalizing them to a specified maximum length. For example, in the StanWifi dataset, sample lengths include 19990, 19993, 18997, and so on. By setting the maximum length to 2000, the algorithm reduces all signal lengths to 2000 (

Figure 6).

3.3.4. Preprocessing: Feature Extraction

After the Wi-Fi signal is extracted using the sliding window method or through the time alignment technique, the Channel State Information (CSI) data is decomposed into amplitude and phase components as described in the Equations (4) and (5).

3.3.5. Normalization

CSI data collected from various environments or devices often exhibit variations in size. Normalization ensures that all data samples are standardized to a uniform size, to ensure compatibility with models requiring fixed input dimensions. In this context, normalization is applied to the amplitude across the datasets using the widely utilized min-max normalization technique for scaling data within a specific range. The formula for min-max normalization is shown in Equation (6).

where

x represents the original data point,

min(x) is the minimum value in the dataset, max(x) is the maximum value in the dataset, and

x′ is the normalized value of

x.

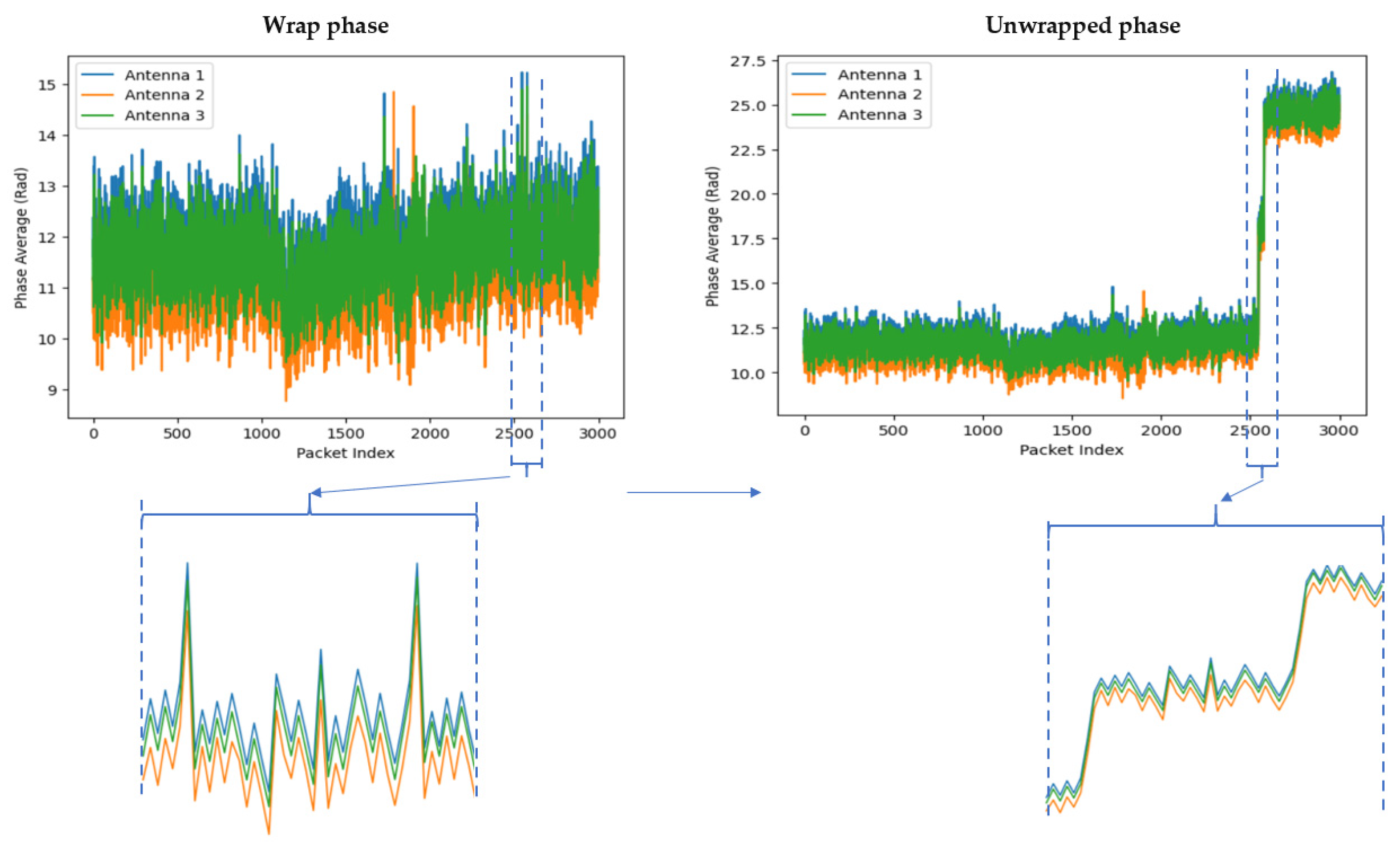

3.3.6. Phase Unwrapping

The phase of CSI provides critical information about wireless signal propagation, including path delays, multipath effects, and Doppler shifts. However, the phase information derived from CSI is often wrapped, meaning it is confined to a specific range, such as [−π,π] or [0, 2π]. This wrapping occurs because phase is typically expressed as an angle, and angles exceeding these bounds are wrapped back into the range.

Phase unwrapping is the process of resolving these phase ambiguities to create a continuous phase representation. This is achieved by identifying and correcting discontinuities introduced by wrapping, ensuring smooth phase progression over time or frequency. The visualization of phase unwrapping for falling action is illustrated in Figure

7, while the formula for phase unwrapping is provided in Equation (7)

.

where

are the unwrapped and raw phases at index

i, respectively;

is the previously unwrapped phase and the floor function ⌊⋅⌋ denotes rounding to the nearest integer.

3.3.7. Gaussian Range Encoding

Gaussian Range Encoding (GRE) is introduced in [

32,

37] as a mechanism to preserve order information from CSI data, which is crucial for recognizing sequential activities such as “sitting down” or “standing up”. Unlike traditional positional encoding methods, which assign unique encodings to individual time steps, GRE focuses on encoding ranges. This approach preserves temporal continuity and improves robustness against subtle variations in activity speeds or blank intervals within the sequence. The final representation of GRE is obtained by multiplying the

K learnable range of vector embeddings with the probability density function (PDF) vector. The PDF is normalized across

K Gaussian distributions.

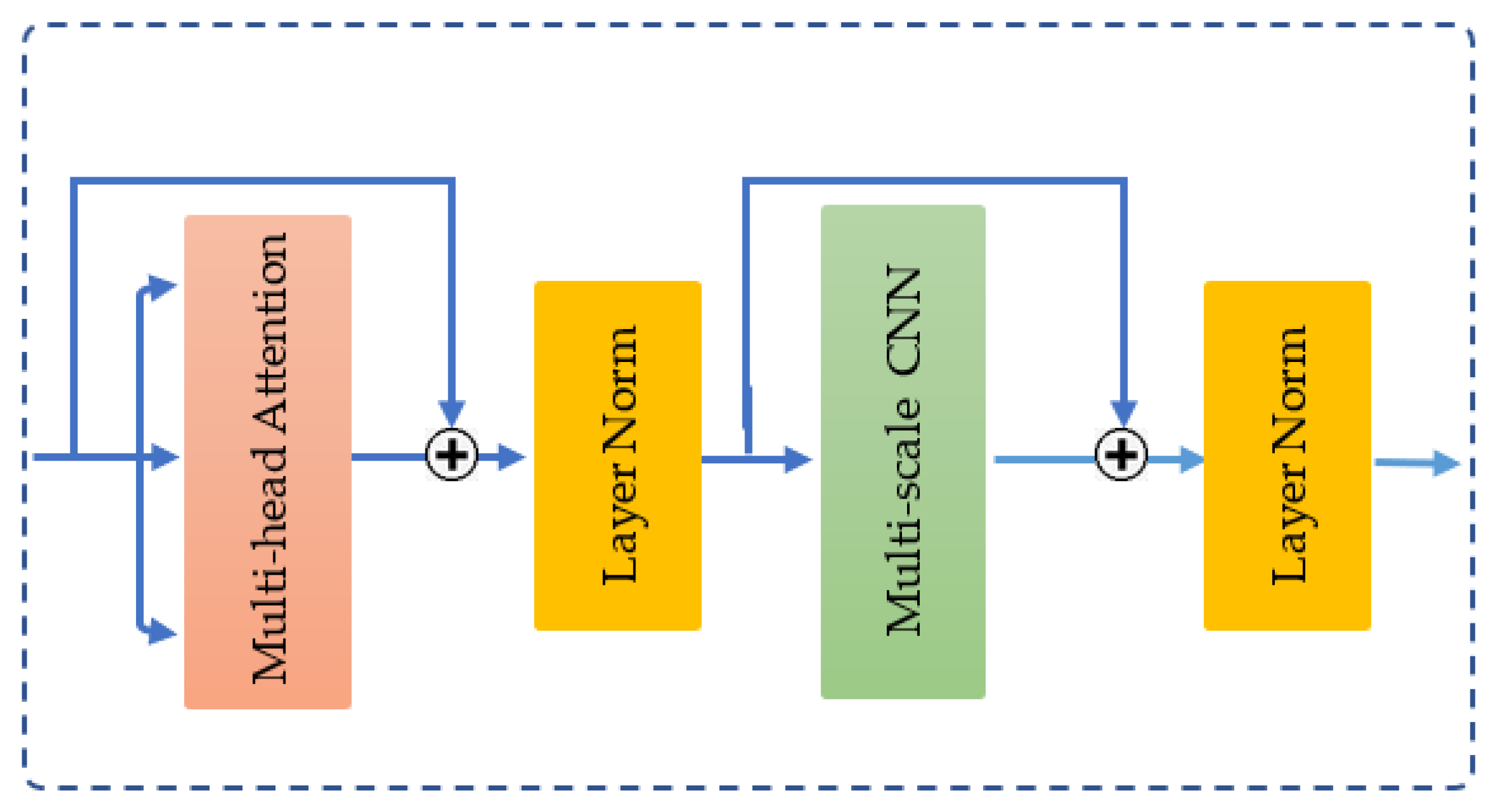

3.3.8. Multi-Scale Convolution Augmented Transformer (MCAT) Layer

The MCAT layer [

32] integrates two key components: a multi-head self-attention mechanism [

29] and a multi-scale convolutional neural network. These components are connected using residual connections and layer normalization [

38], as shown in

Figure 8.

In the multi-head attention stage, the input

, representing amplitude or phase—is transformed into three distinct vectors: query (Q), key (K), and value (V) - via three linear projections. Self-attention computes a weighted sum of the input values, where the weights are determined by the dot product between the query and the corresponding key. The process is defined mathematically as follows:

here,

represents the dimensionality of both the queries and keys,

is the scaling factor used to stabilize gradients and enhance computational efficiency.

To jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces, the vectors Q, K, and V are projected

h times (referred to as

h-heads) using distinct projection parameters. The outputs from these projections are then concatenated and passed through a final projection to generate the output:

where each

and

is the final projection matrix.

Subsequently, the multi-scale CNN stage processes the output features

Y from the multi-head self-attention module by applying learnable weights

. Here,

Wij consists of

do filters, where each filter sized

ji × do. The output of the multi-cale CNN is presented as

P = {P1,P2,…,Pj}, where

is the feature matrix corresponding to the kernel size

ji at index

i.

Pi is computed as follows:

Equation (12) involves a series of operations, including convolution, batch normalization (BN), dropout, and a ReLU activation function.

3.3.9. Gate Residual Networks (GRNs)

Gate Residual Networks (GRNs) [

35] are a type of neural network architecture designed to improve information flow via residual connections while incorporating a gating mechanism to regulate the flow of features. The gating mechanism, typically implemented using a sigmoid function, selectively controls which parts of the input are passed through, allowing the network to prioritize the most relevant features. This combination of residual connections and gating mechanisms enables GRNs to more effectively capture complex patterns and improve model performance, especially in tasks that involve high-dimensional data or deep architectures. GRNs have been widely applied in various domains, including time series forecasting [

36] and sequence modeling [

39], which require learning long-term dependencies.

The structure of GRNs in our model is illustrated in

Figure 9. The figure demonstrates how amplitude and phase data are processed through dense layers with exponential linear unit (ELU) activation functions, after which their outputs are summed using a residual connection (denoted by the summation symbol “+”). The resulting feature matrix undergoes layer normalization before being passed through another dense layer and a sigmoid gating mechanism. The final output is computed by integrating the gated outputs through an additional summation operation. The exponential linear unit (ELU) activation functions, defined as shown in Equation (14).

4. Experimental Evaluation

In this section, we present the experimental results for the three datasets introduced in

Section 3.2 (MultiEnv, StanWifi, and MINE lab dataset). The evaluation metrics employed include accuracy (Acc), precision (Pre), recall, and F1-score. Additionally, we provide a comparative analysis of our results against the baseline and the state-of-the-art model.

4.1. Hyperprameters

In this subsection, we provide a concise summary of the symbols for the variables and hyperparameters utilized in the experiment, and their corresponding values chosen to optimize performance (

Table 3).

The loss function deployed in this experiment is sparse categorical cross-entropy, which is defined in Equation (15):

where

N represents the number of samples,

yi is the true label, and

is the predicted probability for the true class

yi for

ith example.

4.2. Experimental Results on StanWiFi and MINE Lab Datasets

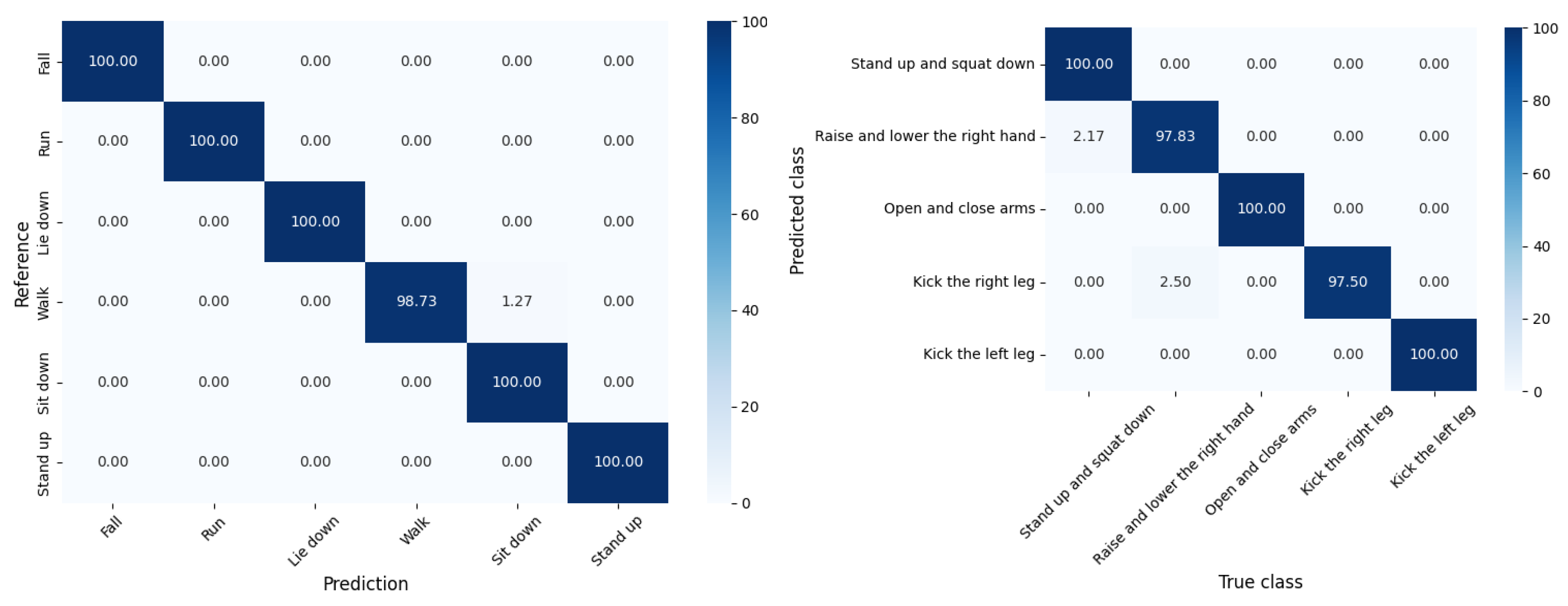

Table 4 compares models on the StanWiFi dataset based on accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. The models are listed chronologically, with the earliest model being THAT (2021) and CSITime (2022), both of which achieved over 98% accuracy but did not report precision, recall, or F1-score. Several other models, such as LiteHAR (2022) and CNN-GRU (2022), report high precision and recall, though not all models provide complete metric details. Notably, our model achieves the highest reported metrics: 99.93% accuracy, 99.86% precision, 99.95% recall, and 99.95% F1-score. This outperforms all other models in the table, demonstrating a significant improvement over previous works in the field.

Table 5 compares the performance of two models, THAT (2021) by Bing et al. and our model on the MINE lab dataset. The THAT (2021) model achieves consistent values across all metrics, scoring 97% for accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Our model significantly outperforms the THAT model, achieving 99.24% across all evaluated metrics. This demonstrates a notable improvement on the MINE lab dataset, highlighting the superior capability of our model in accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. We selected the THAT model for comparison because it is publicly available online.

Figure 10 illustrates the model’s performance on six activities from the StanWifi dataset in the left side: Fall, Run, Lie down, Walk, Sit down, and Stand up. The right side visualizes the model’s performance on additional activities: Stand up and Squat down, Raise and Lower the right hand, Open and close arms, Kick the right leg, and Kick the left leg. The confusion matrices indicate that the model achieved a near-perfect classification for most activities, demonstrating high true positive rates across both datasets.

4.3. Experimental Results on MultiEnv Dataset

Table 6 summarizes the performance of various models on the MultiEnv dataset, divided into three different environments: E1: Office (LOS), E2: Hall (LOS), and E3: Room and hall (NLOS). In the E1 environment, various models such as SVM (2021, 2022), THAT (2021), STC-NLSTMNet (2023), and AAE+RF (2023) are compared. Our model achieves the highest accuracy (99.47%) and outperforms others in all metrics, including precision (99.48%), recall (99.47%), and F1-score (99.47%). In the E2 environment, comparisons include models such as SVM (2021, 2022), THAT (2021), and STC-NLSTMNet (2023). Again, our model achieves the best performance with an accuracy of 98.43%, precision of 98.01%, recall of 97.90%, and F1-score of 97.90%. In the E3 environment, our model once again excels with an accuracy of 98.78%, precision, recall, and F1-score all at 98.78%. This is superior to other models such as THAT (2021), STC-NLSTMNet (2023), and AAE+RF (2023).

5. Conclusions

In this study, we presented a novel approach for Human Activity Recognition (HAR) using Wi-Fi sensing, leveraging both the phase and amplitude components of Channel State Information (CSI). Our proposed model, which combines attention-based mechanisms with a Gated Recurrent Network (GRN) architecture, outperformed state-of-the-art models in HAR. The model’s efficacy was rigorously tested across multiple datasets, including StanWiFi, MultiEnv, and MINE lab dataset, showcasing its adaptability and robustness in both line-of-sight (LOS) and non-line-of-sight (NLOS) environments.

By utilizing both phase and amplitude signals, we addressed the limitations of prior models that predominantly focused on a single feature, leading to improved accuracy in recognizing complex human activities. Our experimental results indicate that the multi-feature approach of combining amplitude and phase information significantly enhances accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score metrics compared to existing methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K.S. and C.Y.L.; methodology, C.Y.L. and T.D.Q.; software, T.D.Q. and C.Y.L.; validation, T.D.Q.; resources, T.K.S.; data curation, T.D.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, T.D.Q.; writing—review and editing, C.Y.L. and T.D.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kaseris, M.; Kostavelis, I.; Malassiotis, S. A Comprehensive Survey on Deep Learning Methods in Human Activity Recognition. Mach Learn Knowl Extr 2024, 6, 842–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, J.K.; Ryoo, M.S. Human Activity Analysis: A Review. ACM Comput Surv 2011, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, Y.; Jing, X. A Survey of Deep Learning-Based Human Activity Recognition in Radar. Remote Sens (Basel) 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravchak, A.; Kapshii, O.; Pournaras, E. Human Activity Recognition Based on Wi-Fi CSI Data -A Deep Neural Network Approach. In Proceedings of the Procedia Computer Science; Elsevier B.V., 2021; Vol. 198; pp. 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Zhou, G.; Lin, Y. Cross-Domain WiFi Sensing with Channel State Information: A Survey. ACM Comput Surv 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chih-Yang Lin; Chia-Yu Lin; Yu-Tso Liu; Yi-Wei Chen; Timothy K. Shih WiFi-TCN: Temporal Convolution for Human Interaction Recognition Based on WiFi Signal. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 126970–126982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Qian, K.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y. Smart Wireless Sensing: From IoT to AIoT; Springer Nature, 2021; ISBN 9789811656583.

- Jannat, M.K.A.; Islam, M.S.; Yang, S.H.; Liu, H. Efficient Wi-Fi-Based Human Activity Recognition Using Adaptive Antenna Elimination. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 105440–105454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan Sigg; Ulf Blanke; Gerhard Troster The Telepathic Phone: Frictionless Activity Recognition from WiFi-RSSI.; IEEE, 2014.

- Gu, Y.; Ren, F.; Li, J. PAWS: Passive Human Activity Recognition Based on WiFi Ambient Signals. IEEE Internet Things J 2016, 3, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu Gu; Lianghu Quan; Fuji Ren WiFi-Assisted Human Activity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Wireless and Mobile, 2014 IEEE Asia Pacific Conference; IEEE, 14; pp. 60–65. 20 August.

- Stephan Sigg; Shuyu Shi; Felix Buesching Leveraging RF-Channel Fluctuation for Activity Recognition: Active and Passive Systems, Continuous and RSSI-Based Signal Features. In Proceedings of the MoMM 2013 : the 11th International Conference on Advances in Mobile Computing and Multimedia; Association for Computing Machinery, 13; p. 599. 20 December.

- Moustafa Youssef; Matthew Mah; Ashok Agrawala Challenges: Device-Free Passive Localization for Wireless Environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 13th annual ACM international conference on Mobile computing and networking; ACM Digital Library, 07; pp. 222–229. 20 September.

- Rathnayake, R.M.M.R.; Maduranga, M.W.P.; Tilwari, V.; Dissanayake, M.B. RSSI and Machine Learning-Based Indoor Localization Systems for Smart Cities. Eng 2023, 4, 1468–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaify, B.A.; Almazari, M.M.; Alazrai, R.; Daoud, M.I. A Dataset for Wi-Fi-Based Human Activity Recognition in Line-of-Sight and Non-Line-of-Sight Indoor Environments. Data Brief 2020, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, S.; Narui, H.; Dayal, S.; Ermon, S.; Valaee, S. A Survey on Behavior Recognition Using WiFi Channel State Information. IEEE Communications Magazine 2017, 55, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Qian, K.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Wu, C.; Yang, Z. Widar3.0: Zero-Effort Cross-Domain Gesture Recognition With Wi-Fi. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2022, 44, 8671–8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Guo, S.; Wang, L.; Lin, C.; Liu, J.; Lu, B.; Fang, J.; Liu, Z.; Shan, Z.; Yang, J. Wiar: A Public Dataset for Wifi-Based Activity Recognition. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 154935–154945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Zou, H.; Lu, C.X.; Wang, D.; Sun, S.; Xie, L. SenseFi: A Library and Benchmark on Deep-Learning-Empowered WiFi Human Sensing. Patterns 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghello, F.; Fabbro, N.D.; Garlisi, D.; Tinnirello, I.; Rossi, M. A CSI Dataset for Wireless Human Sensing on 80 MHz Wi-Fi Channels. IEEE Communications Magazine 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, A.X.; Shahzad, M.; Ling, K.; Lu, S. Device-Free Human Activity Recognition Using Commercial WiFi Devices. In Proceedings of the IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., May 1 2017; Vol. 35; pp. 1118–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaify, B.A.; Almazari, M.; Alazrai, R.; Alouneh, S.; Daoud, M.I. A CSI-Based Multi-Environment Human Activity Recognition Framework. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, C.; Cao, Z.; Cui, W. WiFi CSI Based Passive Human Activity Recognition Using Attention Based BLSTM. IEEE Trans Mob Comput 2019, 18, 2714–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K.; Sai, S.; Gundewar, A.; Rathore, H.; Tiwari, K.; Pandey, H.M.; Mathur, M. CSITime: Privacy-Preserving Human Activity Recognition Using WiFi Channel State Information. Neural Networks 2022, 146, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fard Moshiri, P.; Shahbazian, R.; Nabati, M.; Ghorashi, S.A. A CSI-Based Human Activity Recognition Using Deep Learning. Sensors (Basel) 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehinejad, H.; Valaee, S. LiteHAR: Lightweight Human Activity Recognition from WiFi Signals with Random Convolution Kernels. 2022.

- Shalaby, E.; ElShennawy, N.; Sarhan, A. Utilizing Deep Learning Models in CSI-Based Human Activity Recognition. Neural Comput Appl 2022, 34, 5993–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Jannat, M.K.A.; Hossain, M.N.; Kim, W.S.; Lee, S.W.; Yang, S.H. STC-NLSTMNet: An Improved Human Activity Recognition Method Using Convolutional Neural Network with NLSTM from WiFi CSI. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. 2017.

- Ding, X.; Jiang, T.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, S.; Yang, J.; Zeng, J. Wi-Fi-Based Location-Independent Human Activity Recognition with Attention Mechanism Enhanced Method. Electronics (Switzerland) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, R.; Wu, F.; Yin, L.; Yang, Y. WiTransformer: A Novel Robust Gesture Recognition Sensing Model with WiFi. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Cui, W.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Wu, M. 2021.

- Zeng, Y.; Wu, D.; Gao, R.; Gu, T.; Zhang, D. FullBreathe. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wearable Ubiquitous Technol 2018, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Brauer, J.; Sezgin, A.; Zenger, C. Kalman Filter Based MIMO CSI Phase Recovery for COTS WiFi Devices. In Proceedings of the ICASSP, IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing - Proceedings; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2021; Vol. 2021-June; pp. 4820–4824. [Google Scholar]

- Savarese, P.; Figueiredo, D. A: Gates, 2017.

- Lim, B.; Arik, S.O.; Loeff, N.; Pfister, T. Temporal Fusion Transformers for Interpretable Multi-Horizon Time Series Forecasting. 2019.

- Stragapede, G.; Delgado-Santos, P.; Tolosana, R.; Vera-Rodriguez, R.; Guest, R.; Morales, A. Mobile Keystroke Biometrics Using Transformers. 2022.

- Ba, J.L.; Kiros, J.R.; Hinton, G.E. Layer Normalization. 2016.

- Qin, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhong, Y. Hierarchically Gated Recurrent Neural Network for Sequence Modeling. 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).