1. Introduction

Monitoring vital signs such as Heart Rate (HR) and Respiratory Rate (RR) is crucial in both clinical and home settings. Despite advancements in monitoring technologies, diagnostic inaccuracies and inadequate follow-ups still contribute to medical errors and adverse outcomes . As highlighted, timely and continuous monitoring can be essential in identifying deteriorations, particularly during nighttime, allowing early intervention for potential cardiac or respiratory events.

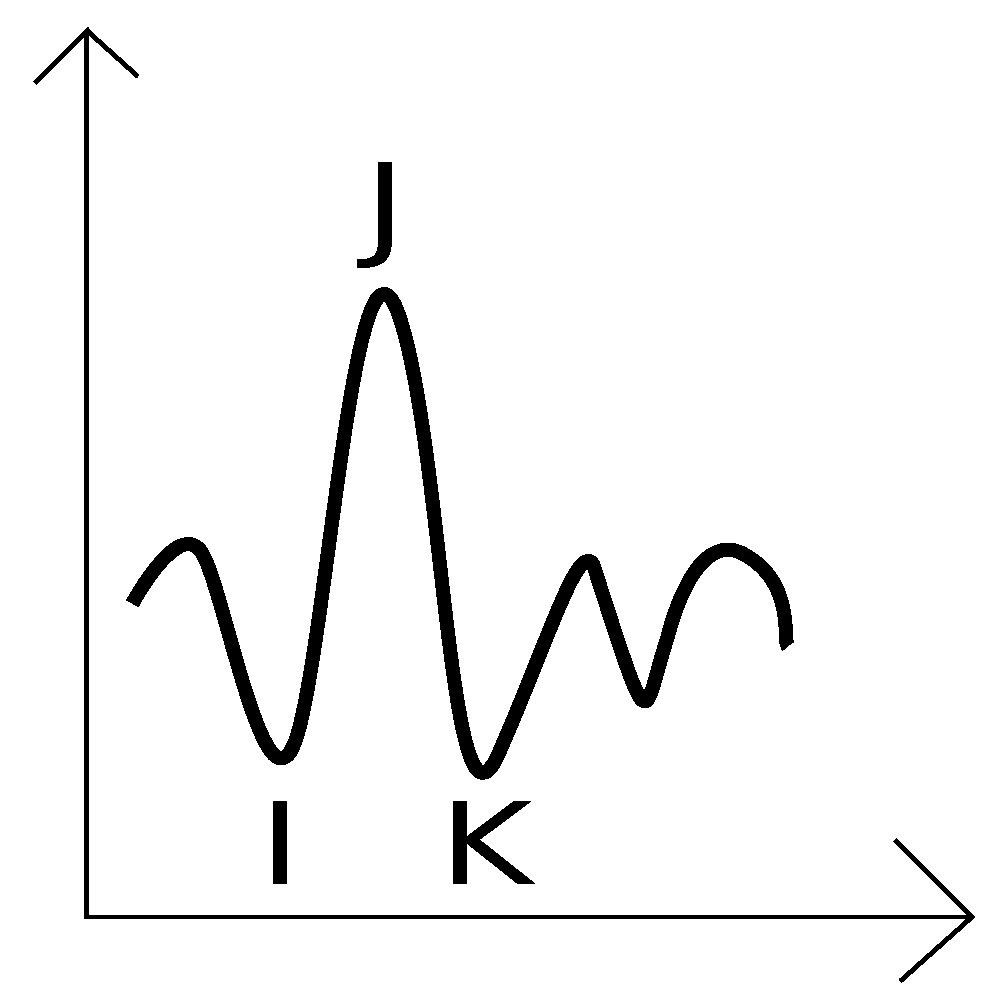

One promising non-invasive method for HR monitoring is the Ballistocardiogram (BCG), which records the body’s mechanical response to cardiac ejection forces. Although introduced in the 19th century [

1], its clinical relevance has only recently gained traction. The BCG signal, similar to the Electrocardiogram (ECG), contains identifiable patterns such as the IJK complex, which enables HR estimation through intervals like the JJ segment. However, motion artifacts present a significant challenge in accurate signal analysis.

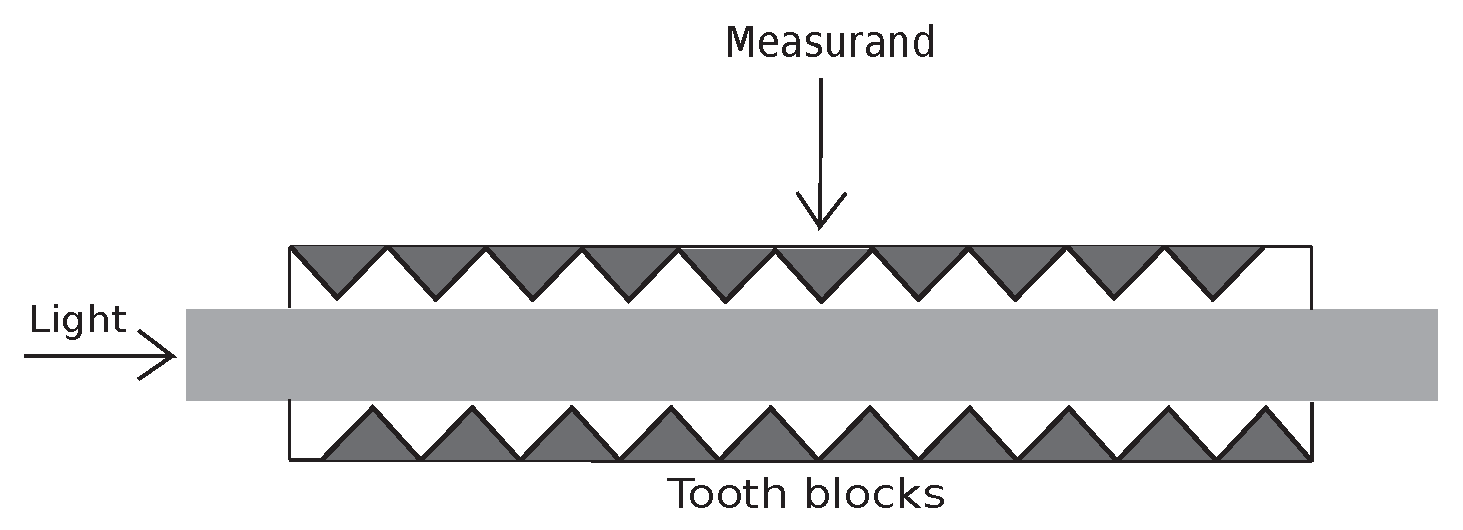

BCG and RR signals are typically acquired using pressure-sensitive systems, such as smart mattresses. These sensors detect micro-movements associated with physiological activity. Among emerging technologies, microbend fiber optic sensors (FOS) have shown promise due to their high sensitivity and cost efficiency. These sensors detect mechanical activity by monitoring light attenuation caused by external pressure variations [

2], as illustrated in

Figure 1.

Extracting meaningful data from raw FOS signals requires robust signal processing techniques to suppress various noise sources, including motion artifacts, power line interference, and 1/f noise. Identifying BCG signals amidst this noise calls for sophisticated denoising and feature extraction methods.

As discussed in

Section 2, signal processing approaches in literature are often grouped into four main categories. This work explores four representative methods [

3,

4,

5,

6] that have demonstrated effectiveness in HR and/or RR extraction using FOS mats.

Key techniques include the Wavelet Transform (WT), which provides multi-resolution analysis by decomposing the signal into different frequency bands using filter banks. The Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD), a core part of the Hilbert-Huang Transform [

7], breaks down signals into intrinsic mode functions to extract time-varying frequency content. Additionally, the cepstrum, derived from the inverse Fourier transform of the log spectrum [

8], is valuable for identifying periodic components like HR and RR.

This paper implements and compares the four aforementioned methods using FOS-based data, evaluating their performance in accurately extracting vital sign information.

Figure 2.

Shape of a BCG signal and the IJK complex.

Figure 2.

Shape of a BCG signal and the IJK complex.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sensors

Significant research has focused on using fiber optic sensors (FOS) for ballistocardiograms (BCG) and other biomedical signals. Lau et al. [

9] developed a microbend fiber optic sensor (MFOS) capable of measuring the force exerted on a sensor mat. This highly sensitive mat was used in an MRI environment for real-time measurement and recording of the breathing rate. The raw signal underwent bandpass filtering and a peak detection algorithm to retrieve the breathing rate. Their novel sensor showed promising results in enabling respiratory-gated MRI acquisition, reducing physiological noise caused by breathing.

Chen et al. [

10] also utilized a micro-bend fiber optic sensor (MFS) embedded in a light-weight cushion to record high-quality BCG signals from subjects seated on a chair. They connected the sensor output to a National Instruments DAQ card with LabVIEW software to perform analog and digital band-pass filtering, with analog filtering implemented within the prototype itself to reduce system cost :contentReference[oaicite:0]index=0.

Sadek et al. [

3] employed a Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensor to capture BCG signals from ten subjects lying under a thin bedsheet. Similarly, Dziuda et al. [

11] extracted both breathing and heart rates from a healthy subject using an FBG placed between the subject’s back and a chair. Their system incorporated filtering, averaging, and ECG referencing.

Beyond FOS, other sensor types have also been explored. For example, Pino et al. [

12] retrieved heart rhythm using an electromechanical film (EMFi) piezoelectric sensor.

2.2. Digital Signal Processing

2.2.1. Wavelet Transform

To achieve unobtrusive vital sign monitoring, Postolache et al. [

13] employed an 8-level Daubechies 4 (db4) wavelet transform followed by moving average filtering. Their approach was validated against ECG and spirometer signals from 10 young participants. However, the study’s limitation lies in its exclusive use of healthy subjects.

Jin et al. [

14] combined Donoho and Johnstone’s [

15] wavelet shrinkage technique with a Symlet 8 wavelet base and used a peak search algorithm to extract heart rate.

Delière et al. [

16] used a Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) with a Morlet wavelet base to analyze amplitude modulation in BCG induced by respiration (BAMR) under a controlled breathing protocol. They expressed BAMR via local energy maxima in each cardiac cycle and examined heart rate variability (HRV) from BCG, rather than relying on respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) from ECG.

Sadek et al. [

4] implemented the Maximal Overlap Discrete Wavelet Transform (MODWT) using an 8-vanishing moment Symlet wavelet. This approach, when applied to MFOS data, outperformed their earlier CEEMDAN-based method on FBG sensor data in terms of speed, with minimal compromise in accuracy.

Pino et al. [

12] compared Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) and wavelet transforms for BCG extraction. While modes 2 and 3 from EMD held the heart rate signal, wavelet analysis using a Daubechies 6 (db6) base yielded superior results.

2.2.2. Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD)

Pinheiro et al. [

17] applied EMD to decompose BCG recordings into intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) and retrieved heartbeat information from motionless subjects. However, performance degraded significantly in the presence of motion artifacts.

Song et al. [

18] adopted Ensemble EMD (EEMD) to extract features from BCG for cardiovascular classification. They used time-domain, frequency-domain, and nonlinear metrics, followed by classification using a Naive Bayes classifier.

Sadek et al. [

3] extended EEMD to Complementary Ensemble EMD with Adaptive Noise (CEEMDAN) for enhanced BCG extraction from FBG sensors. They achieved accurate heart rate detection at the 9th decomposition level. Their approach, augmented by sensor fusion, was more resilient to motion artifacts and faster than conventional EEMD.

Table 1.

Summary of related works. MFOS: Microbend Fiber Optic Sensor; FBG: Fiber Bragg Grating; FS: Force Sensor; PFS: Piezoelectric Force Sensor; PS: Pressure Sensor; LCS: Load Cell Sensor; FCP: Force Coupling Pad; HR: Heart Rate; BR: Breathing Rate; BPF: Band Pass Filter; WT: Wavelet Transform; EMD: Empirical Mode Decomposition; ML: Machine Learning; CS: Cepstrum

Table 1.

Summary of related works. MFOS: Microbend Fiber Optic Sensor; FBG: Fiber Bragg Grating; FS: Force Sensor; PFS: Piezoelectric Force Sensor; PS: Pressure Sensor; LCS: Load Cell Sensor; FCP: Force Coupling Pad; HR: Heart Rate; BR: Breathing Rate; BPF: Band Pass Filter; WT: Wavelet Transform; EMD: Empirical Mode Decomposition; ML: Machine Learning; CS: Cepstrum

| Publication |

Sensor Type |

Target Signal |

Processing Tool |

| [9] |

MFOS |

BR |

BPF |

| [10] |

MFOS |

HR |

BPF |

| [3] |

FBG |

HR |

EMD |

| [11] |

FBG |

BR/HR |

BPF |

| [12] |

EMFi |

HR |

WT/EMD |

| [13] |

EMFi |

BR/HR |

WT |

| [14] |

- |

HR |

WT |

| [16] |

- |

HR |

WT |

| [4] |

MFOS |

HR |

WT |

| [17] |

EMFi |

HR |

EMD |

| [18] |

FS |

HR |

EMD |

| [5] |

FS |

HR |

ML |

| [19] |

Piezo FS |

HR |

ML |

| [20] |

LCS |

HR |

WT/ML |

| [21] |

PFS |

HR |

ML |

| [22] |

PVDF |

HR |

CS |

| [6] |

FBG |

HR |

CS |

| [23] |

FBG |

BR |

CS |

| [24] |

PS |

HR |

CS |

| [25] |

LCS |

BR/HR |

BPF |

| [26] |

FCP |

BR/HR |

BPF |

| [27] |

PS |

HR |

BPF |

2.2.3. Machine Learning

With the rise of machine learning (ML), several researchers have applied it to non-intrusive heart rate detection. Bruser et al. [

5] used clustering algorithms to generate a prototype heartbeat. Cross-correlation and Euclidean distance were employed to identify recurring beats and heart valve signals.

Paalasmaa and Ranta [

19] developed a system using a synthesized ideal heartbeat template, matched against signal segments using correlation.

Noh et al. [

20] proposed a portable heart rate monitoring system using a sensor mat. They preprocessed signals using a Daubechies 4 wavelet and applied template matching derived from intra-signal correlations. Their wavelet-only approach achieved 94% heartbeat detection accuracy across 10 subjects, which improved to 98% with the ML-enhanced layer.

2.2.4. Cepstrum Analysis

Cepstrum-based techniques have also shown promise for heart rate estimation, especially in complex, non-stationary signals. For instance, Bruser et al. [

22] and Zhu et al. [

6,

23] applied cepstral methods to estimate HR and BR from BCG signals with robust performance even in noisy environments.

3. Methodology

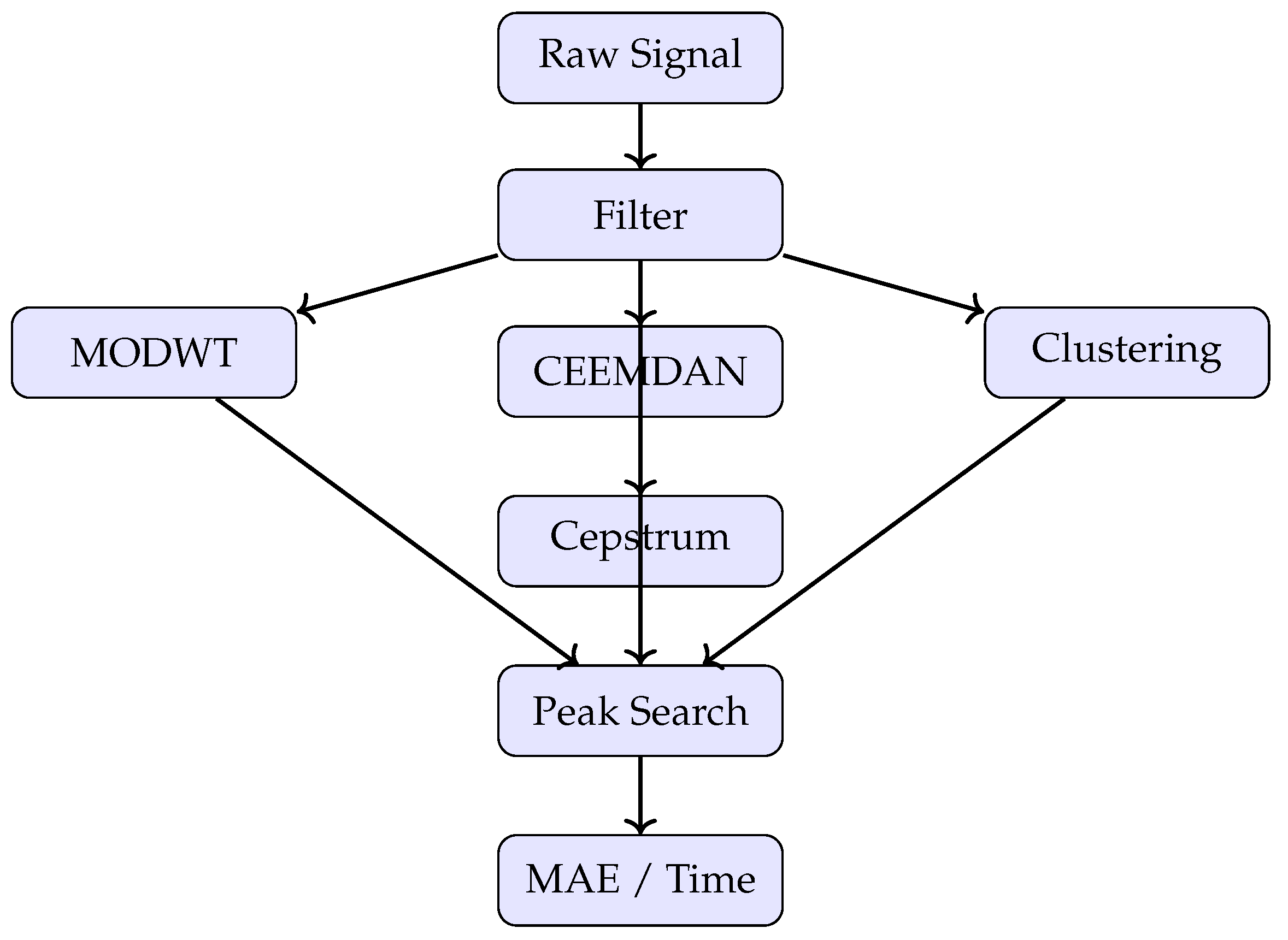

This section details the experimental platform, data-collection protocol, signal-processing algorithms, and evaluation metrics adopted in the study. An overview of the end-to-end workflow.

3.1. Hardware Description

A flexible fibre-optic sensor (FOS) mat was affixed to the backrest of a standard office chair. The mat consists of twelve equally spaced Bragg gratings (spatial resolution: 40 mm) embedded in a 0.8-mm-thick polyurethane sheet; strain-induced wavelength shifts are converted to voltage via a custom optical interrogator (bandwidth: 0–25 Hz).

Acquisition module

Analogue outputs are sampled at 50 Hz with a 16-bit A/D converter (Texas Instruments ADS1115) housed on a low-power microcontroller (ESP32-S3, 240-MHz dual-core Tensilica LX7, 512-kB SRAM). A real-time clock (±2 ppm) tags each sample before serial transfer to the host PC via USB 2.0. The host runs MATLAB R2023a on Ubuntu 22.04 LTS; CPU: Intel Core i7-11800H (8 cores, 2.3–4.6 GHz); RAM: 32 GB DDR4.

Reference garment

For ground truth, participants wore a Hexoskin “Smart Shirt’’ (firmware 4.4) that records single-lead ECG (256 Hz, 12-bit) and thoracic respiratory inductive plethysmography (128 Hz). R-peak times from the ECG provide the reference heart-rate (HR) series, while respiration peaks supply reference breathing-rate (RR) data. Juxtaposes a segment of the Ballistocardiogram (BCG) derived from the FOS with its synchronised ECG trace.

3.2. Experimental Setup

Six healthy adults (3 male, 3 female, age 20-35 years) volunteered via an internal call at the research centre. After written informed consent, the institutional review board classified the protocol as minimal risk.

Each session comprises:

Baseline rest (30 s) to settle into the chair.

Cough event 1 — one voluntary cough used as a synchronisation marker.

Quiet sitting (5 min).

Breath-hold (30 s) at functional residual capacity.

Post-breath rest (2 min).

Cough block 2 — ten coughs, 5-s spacing.

Cough block 3 — ten coughs, 2-s spacing.

All timings are announced verbally; a video camera logs the session to cross-check event times during annotation. Coughs serve a double purpose: (i) they introduce large artefacts for algorithm stress-testing; and (ii) they enable millisecond-level alignment between FOS and Hexoskin timelines.

3.3. Signal-Processing Algorithms

Four heartbeat-extraction pipelines are benchmarked: MODWT, CEEMDAN, an unsupervised clustering approach, and a cepstrum-based technique. For fairness, each pipeline terminates in the same Adaptive Peak Search routine, except where noted.

3.3.1. Adaptive Peak Search

A 10-s sliding window (90 % overlap) inspects the pre-processed BCG. Within each window:

Initialise a peak-detector threshold to 30 % of the window’s RMS amplitude.

While the number of detected peaks exceeds the physiological upper bound (180 beats/min), increment the threshold by 5 % and re-detect.

While the count falls below the lower bound (40 beats/min), decrement the threshold by 5 % and re-detect.

HR is estimated as , where is the mean inter-peak interval (J–J distance).

Window start times advance by 1 s to produce a 1-Hz HR estimate sequence.

3.3.2. Maximal Overlap Discrete Wavelet Transform (MODWT)

Using the

wtt toolbox, a level-4 Daubechies-4 MODWT isolates the 0.8–3.0-Hz band containing the BCG’s principal cardiac component[

4]. The smooth (approximation) coefficients are fed to the adaptive peak search.

3.3.3. Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (CEEMDAN)

CEEMDAN mitigates end effects and mode mixing inherent in classical EMD. Configuration follows [

3]: Gaussian white-noise standard deviation 0.2, 100 realisations, 30 sifting iterations. Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) with centre frequency between 0.8 and 3.0 Hz are summed and passed to the peak search.

3.3.4. Unsupervised Machine Learning

Following Brüser

et al. [

5], the clustering-based pipeline proceeds as follows:

A 30-second calibration segment is first segmented into individual heartbeat candidates using a simple energy-based peak detector.

For each detected beat, a 20-dimensional feature vector is computed. This vector includes temporal characteristics (e.g., beat duration, rise time, inter-peak intervals) and frequency-domain attributes (e.g., spectral centroid, bandwidth, dominant frequency).

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is applied to reduce dimensionality while preserving variance. The top two principal components are retained, capturing approximately 95% of the total variance.

The PCA-transformed data is clustered using k-means with . This value was chosen empirically to balance model expressiveness and computational complexity. The cluster centroid with the highest average energy is selected as the prototype heartbeat.

The full signal is then scanned using correlation and Euclidean distance metrics against the prototype. Two resulting peak trains are averaged pointwise to form a robust heartbeat estimate, which is passed to the adaptive peak search stage.

3.3.5. Cepstrum Analysis

The raw BCG is band-pass filtered (1–10 Hz, 4th-order Butterworth, dB). A 10-s Hamming window slides along the signal; each segment’s real cepstrum is computed. A Savitzky–Golay filter (2nd-order, frame length 11) smooths the cepstrum, after which the dominant peak in the 0.33–1.5-s quefrency range (40–180 BPM) is converted to HR. Because peaks are located in quefrency rather than time, the adaptive search is not applied.

3.4. Validation Metrics

Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

For a sequence of

n HR estimates

and reference values

,

MAE is reported in beats per minute (BPM).

Computational Load

Execution time is captured with tic/toc in MATLAB, excluding file I/O, and normalised per minute of signal. All trials run single-threaded; the coefficient of variation across five repeats is below 3 %.

Figure 3.

Compact pipeline: signal input, filtering, four methods, peak detection, and evaluation.

Figure 3.

Compact pipeline: signal input, filtering, four methods, peak detection, and evaluation.

3.5. Reproducibility and Resources

To support reproducibility. Interested readers may contact the authors for access to implementation details or datasets used in this study.

4. Results and Discussion

In this work, each methods were applied as described earlier in

Section 3.3.

Table 2.

Performance of the MODWT algorithm on all subjects

Table 2.

Performance of the MODWT algorithm on all subjects

| Subject |

MAE (Average) |

MAE (Std) |

CS |

| 1 |

12.97 |

8.67 |

|

| 2 |

11.10 |

5.11 |

|

| 3 |

25.08 |

9.23 |

|

| 4 |

17.14 |

5.86 |

|

| 5 |

15.18 |

10.71 |

|

| 6 |

7.15 |

4.75 |

|

| Mean |

14.83 |

7.39 |

|

Table 3.

Performance of the CEPSTRUM algorithm on all subjects

Table 3.

Performance of the CEPSTRUM algorithm on all subjects

| Subject |

MAE (Average) |

MAE (Std) |

CS |

| 1 |

4.76 |

2.13 |

|

| 2 |

12.66 |

2.76 |

|

| 3 |

6.09 |

2.32 |

|

| 4 |

7.15 |

4.37 |

|

| 5 |

5.20 |

6.02 |

|

| 6 |

4.71 |

3.21 |

|

| Mean |

6.76 |

3.47 |

|

Table 4.

Performance of the CEEMDAN algorithm on all subjects

Table 4.

Performance of the CEEMDAN algorithm on all subjects

| Subject |

MAE (Average) |

MAE (Std) |

CS |

| 1 |

9.48 |

2.77 |

|

| 2 |

2.82 |

1.96 |

|

| 3 |

4.28 |

2.13 |

|

| 4 |

1.83 |

1.96 |

|

| 5 |

7.82 |

7.34 |

|

| 6 |

9.09 |

3.76 |

|

| Mean |

5.88 |

3.32 |

|

Table 5.

Performance of the CLUSTERING algorithm on all subjects

Table 5.

Performance of the CLUSTERING algorithm on all subjects

| Subject |

MAE (Average) |

MAE (Std) |

CS |

| 1 |

4.44 |

2.85 |

|

| 2 |

18.85 |

7.70 |

|

| 3 |

12.57 |

3.19 |

|

| 4 |

9.11 |

3.20 |

|

| 5 |

7.83 |

4.48 |

|

| 6 |

3.25 |

2.60 |

|

| Mean |

9.34 |

4.00 |

|

5. Conclusion

This study presents a comparative analysis of four distinct signal processing methodologies for extracting heart rate (HR) from data captured by a fibre-optic sensor (FOS) embedded within a smart mattress. The selected techniques—Maximal Overlap Discrete Wavelet Transform (MODWT), Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (CEEMDAN), cepstral analysis via sliding windows, and an unsupervised machine learning-based clustering algorithm—each represent a broader category of physiological signal analysis approaches.

Each method was evaluated based on two primary performance indicators: accuracy, as quantified by the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) relative to a ground-truth reference ECG obtained from a Hexoskin smart garment, and computational efficiency, assessed by measuring algorithm runtime on a standard computing platform.

The proposed system is entirely non-invasive and designed to operate using unobtrusive, continuous sensing via the mattress interface. Results indicate that all four algorithms are capable of extracting periodic components corresponding to cardiac activity from the ballistocardiogram (BCG), though their effectiveness varies significantly depending on the metric being prioritized.

Among the tested algorithms, the method identified as X yielded the lowest MAE, indicating a high degree of precision in estimating heart rate. However, this accuracy came at the cost of substantial computational time, making it less suitable for real-time applications. In contrast, the method denoted as Y, while slightly less accurate, demonstrated significantly faster execution (with an average runtime of Z seconds per minute of signal), rendering it more appropriate for real-time or embedded deployments where processing constraints are critical.

A notable observation throughout this work is the degradation in performance relative to similar algorithms reported in the literature. This decline is attributed to the realistic and movement-rich experimental protocol adopted in this study. Unlike prior studies that rely heavily on artifact-free or highly controlled datasets, our protocol introduced deliberate disturbances—including voluntary coughing and breath holds—mimicking more naturalistic conditions encountered in clinical or home settings. These conditions induced substantial motion artifacts in the BCG signal, complicating the accurate extraction of heartbeat patterns. In fact, only about five minutes of each subject’s recording could be reliably labelled as free of significant movement contamination. The remaining data, while too noisy for heart rate estimation, holds potential for future research into artifact-resilient signal processing.

The findings highlight motion artifacts as a primary barrier to robust HR monitoring using textile-based sensor systems. Mitigating these distortions remains a pressing challenge for future development, especially if such systems are to be deployed in ambulatory care, sleep studies, or long-term patient monitoring scenarios.

Nevertheless, this work demonstrates the feasibility of extracting cardiovascular parameters using a passive, textile-based sensing system and lays the groundwork for future research into respiratory signal extraction and disease classification. With further refinement, including the integration of motion-resilient algorithms or hybrid sensor fusion, this platform could evolve into a powerful tool for continuous, contactless health monitoring, particularly valuable in the context of early detection and ongoing management of respiratory and cardiovascular pathologies.

References

- Gordon, J.W. Certain molar movements of the human body produced by the circulation of the blood. Journal of Anatomy and Physiology 1877, 11, 533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Udd, E. An overview of fiber-optic sensors. review of scientific instruments 1995, 66, 4015–4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, I.; Biswas, J.; Fook, V.F.S.; Mokhtari, M. Automatic heart rate detection from FBG sensors using sensor fusion and enhanced empirical mode decomposition. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Signal Processing and Information Technology (ISSPIT); 2015; pp. 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadek, I.; Biswas, J.; Abdulrazak, B.; Haihong, Z.; Mokhtari, M. Continuous and unconstrained vital signs monitoring with ballistocardiogram sensors in headrest position. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Health Informatics (BHI); 2017; pp. 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruser, C.; Stadlthanner, K.; Waele, S.d.; Leonhardt, S. Adaptive Beat-to-Beat Heart Rate Estimation in Ballistocardiograms. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine 2011, 15, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Fook, V.F.S.; Jianzhong, E.H.; Maniyeri, J.; Guan, C.; Zhang, H.; Jiliang, E.P.; Biswas, J. Heart rate estimation from FBG sensors using cepstrum analysis and sensor fusion. In Proceedings of the 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; 2014; pp. 5365–5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.E.; Shen, Z.; Long, S.R.; Wu, M.C.; Shih, H.H.; Zheng, Q.; Yen, N.C.; Tung, C.C.; Liu, H.H. The empirical mode decomposition and the Hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 1998, 454, 903–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, A.V.; Schafer, R.W. From frequency to quefrency: A history of the cepstrum. IEEE signal processing Magazine 2004, 21, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, D.; Chen, Z.; Teo, J.T.; Ng, S.H.; Rumpel, H.; Lian, Y.; Yang, H.; Kei, P.L. Intensity-Modulated Microbend Fiber Optic Sensor for Respiratory Monitoring and Gating During MRI. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2013, 60, 2655–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Teo, J.T.; Ng, S.H.; Yang, X. Portable fiber optic ballistocardiogram sensor for home use. 2012, p. 82180X. [CrossRef]

- Dziuda, L.; Skibniewski, F.W.; Krej, M.; Lewandowski, J. Monitoring Respiration and Cardiac Activity Using Fiber Bragg Grating-Based Sensor. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2012, 59, 1934–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino, E.J.; Chávez, J.A.P.; Aqueveque, P. Noninvasive ambulatory measurement system of cardiac activity. In Proceedings of the 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2015; pp. 7622–7625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postolache, O.; Girao, P.S.; Postolache, G.; Pereira, M. Vital Signs Monitoring System Based on EMFi Sensors and Wavelet Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Instrumentation Measurement Technology Conference IMTC 2007, 2007, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Wu, Y. A Novel Heart Rate Detection Algorithm in Ballistocardiogram Based on Wavelet Transform. In Proceedings of the 2009 Second International Workshop on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2009; pp. 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoho, D.L.; Johnstone, I.M. Adapting to Unknown Smoothness via Wavelet Shrinkage. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1995, 90, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delière, Q.; Tank, J.; Funtova, I.; Luchitskaya, E.; Gall, D.; Borne, P.V.d.; Migeotte, P.F. Ballistocardiogram amplitude modulation induced by respiration: a wavelet approach. In Proceedings of the 2015 Computing in Cardiology Conference (CinC); 2015; pp. 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, E.C.; Postolache, O.A.; Girão, P.S. Online heart rate estimation in unstable ballistocardiographic records. In Proceedings of the 2010 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology; 2010; pp. 939–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ni, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, W.; Wang, T. Extracting Features for Cardiovascular Disease Classification Based on Ballistocardiography. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 12th Intl Conf on Ubiquitous Intelligence and Computing and 2015 IEEE 12th Intl Conf on Autonomic and Trusted Computing and 2015 IEEE 15th Intl Conf on Scalable Computing and Communications and Its Associated Workshops (UIC-ATC-ScalCom); 2015; pp. 1230–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paalasmaa, J.; Ranta, M. Detecting heartbeats in the ballistocardiogram with clustering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ICML/UAI/COLT 2008 Workshop on Machine Learning for Health-Care Applications, Helsinki, Finland, 2008, Vol.

- Noh, Y.H.; Ye, S.Y.; Jeong, D.U. Development of the BCG feature extraction methods for unconstrained heart monitoring. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Computer Sciences and Convergence Information Technology; 2010; pp. 923–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Y.; Karasik, R.; Shinar, Z. Contact-free piezo electric sensor used for real-time analysis of inter beat interval series. In Proceedings of the 2016 Computing in Cardiology Conference (CinC); 2016; pp. 769–772. [Google Scholar]

- Brüser, C.; Kortelainen, J.M.; Winter, S.; Tenhunen, M.; Pärkkä, J.; Leonhardt, S. Improvement of Force-Sensor-Based Heart Rate Estimation Using Multichannel Data Fusion. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2015, 19, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Maniyeri, J.; Fook, V.F.S.; Zhang, H. Estimating respiratory rate from FBG optical sensors by using signal quality measurement. In Proceedings of the 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2015; pp. 853–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortelainen, J.M.; Gils, M.v.; Pärkkä, J. Multichannel bed pressure sensor for sleep monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2012 Computing in Cardiology; 2012; pp. 313–316. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.K.; Yoon, H.; Jung, D.W.; Hwang, S.H.; Park, K.S. Ballistocardiogram of baby during sleep. In Proceedings of the 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2015; pp. 7167–7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, D.C.; Patrie, J.T.; Suratt, P.M.; Felder, R.A.; Alwan, M. Development and Preliminary Validation of Heart Rate and Breathing Rate Detection Using a Passive, Ballistocardiography-Based Sleep Monitoring System. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine 2009, 13, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lydon, K.; Su, B.Y.; Rosales, L.; Enayati, M.; Ho, K.C.; Rantz, M.; Skubic, M. Robust heartbeat detection from in-home ballistocardiogram signals of older adults using a bed sensor. In Proceedings of the 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2015; pp. 7175–7179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).