1. Introduction

Nanotechnological approach developed by Richard P. Feynman in 1950s, helped to improve the drug significance in both research and medical care aspects [

1]. In addition to the already approved nano-formulations, many more are either waiting for pre-approval and clinical trials, or are ready to hit the global market. Researchers across the globe are developing nano-formulations including liposomes, niosomes, dendrimers, polymeric nanoparticles, nanocrystals, nanoemulsions, nanosuspensions, etc. for targeted drug delivery. These targeted nano-systems will contribute to better patient compliance by enhancing drug efficacy along with reduced dosage and dosing frequency, as well as systemic side effects [

2,

3,

4].

Nano-formulations have been found to enhance in-vivo drug performance compared to conventional formulations that usually exhibits poor bioavailability. Therefore, the current research is focused toward nanosizing of drugs into different formats including nanoparticles, nanocrystals, or nano-suspensions by simple means to speed up their dissolution rate, and improve bioavailability without the need for complex methods. According to the Noyes Whitney equation, the rate of dissolution is inversely related to the particle size. Usually, 10-100 nm nanoparticles exhibit improved delivery, however macrophages opsonise particles larger than this range more frequently. Moreover, small size of nanocarriers allows targeted delivery to improve drug accumulation and efficacy through enhanced solubility and dissolution, achieving desired release profile (controlled or prolonged), reduced stomach breakdown, along with improved arterial absorption and circulation time [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

15,

16].

Furthermore, solid nanoparticles offer significant benefits in drug development due to their biophysical stability and ability to modify drug release (controlled and continual), offering significant opportunities for product life cycle management [

17]. Several studies have demonstrated that nano-formulations can enhance the rate of drug dissolution (

Table 1) [

18].

Dissolution is a fundamental property of solids governed by their affinity towards dissolution media. Further, the time taken by the dosage form to release its content and subsequently dissolve will regulate the time at which significant drug levels may appear to readily cross intestinal mucosa. Therefore, the ability of a drug to dissolve has a substantial impact on its absorption, bioavailability, and efficacy [

19].

Dissolution testing is widely used for stability and quality control purposes for both oral and non-oral dosage forms. In-vitro dissolution study act as a surrogate test for evaluating in-vivo performance of the drug. Furthermore, the dissolution procedure should be designed using a suitable validated approach based on the type of dosage. In many respects, dissolution testing is crucial to regulatory decision-making [

20]. Dissolution testing is frequently used to evaluate the efficacy and quality of drug products in development and production, including routine quality monitoring for batch release and stability studies. Dissolution testing may be used for several purposes, such as biowaiver requests and predicting in-vivo drug performance. The data from dissolution testing can be used to guide the development of new formulations and product development procedures to optimize products and maintain product quality and manufacturing process efficiency [

21,

22].

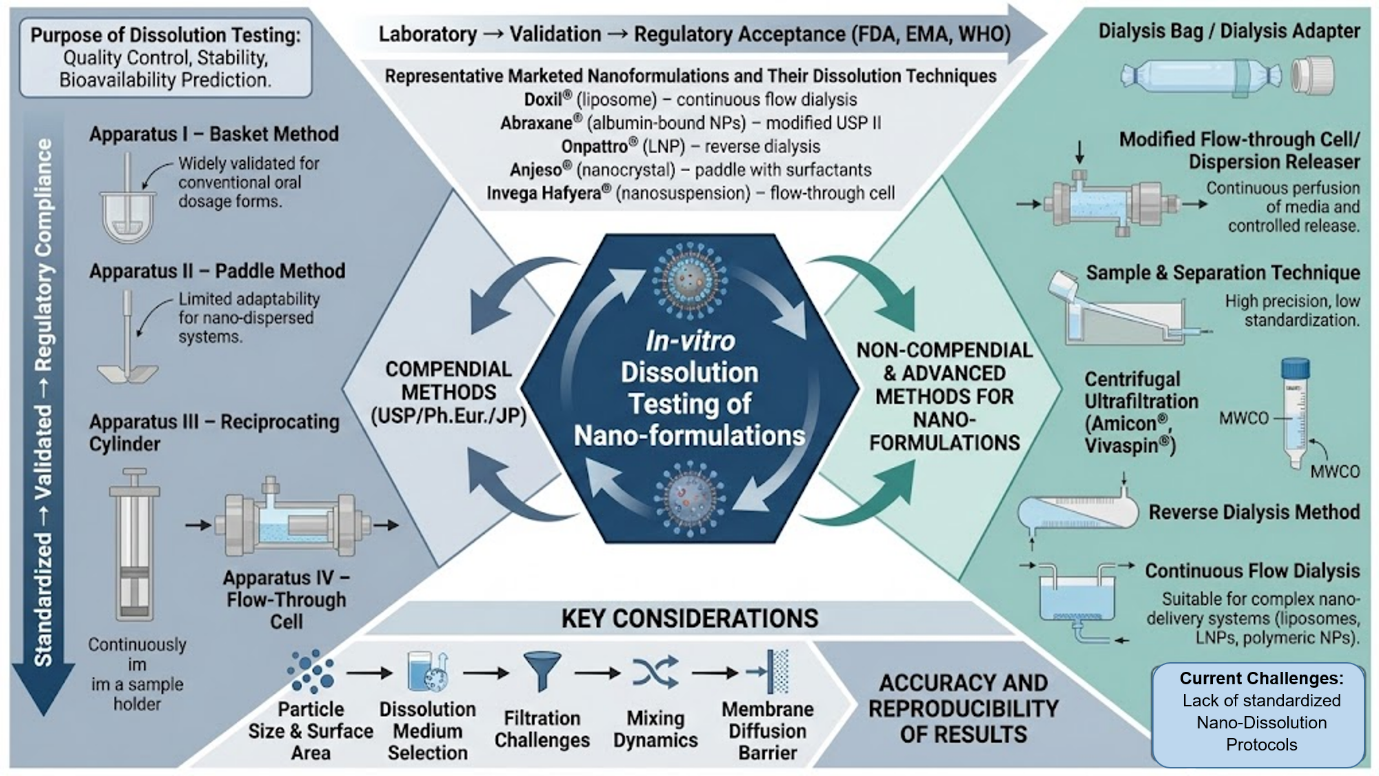

Recent developments in pharmaceutical formulation suggest the need for standard protocols or specifications for in-vitro drug release studies from nano-formulations. In-vitro dissolution testing is crucial for understanding drug release pattern in biological systems. Moreover, at the time of registration, regulatory agencies require in-vitro dissolution test protocol to be conducted in accordance with standard experimental procedures to verify the drug release property from nano-formulation. Currently, no standard specification exists for dissolution testing of nano-formulations, potentially leading to unpredictable or inconsistent therapeutic outcome during clinical trials [

23,

24,

25]. The primary focus of the present article is on various types of in-vitro profiling studies available for nano-formulations, as well as different compendial methods that can be used to conduct the same.

1.1. Recent Advances in Marketed Nano Formulations to Improve the Therapeutic Efficacy of Drugs

The pharmaceutical industry has made significant progress in nano-formulation development to address the limitations of traditional drug delivery. Many nano-formulations have advanced from research to market approval over the last five years, demonstrating improved therapeutic efficacy. Lipid nanoparticles have sparked a lot of interest, particularly since the approval of Onpattro® for hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis and Leqvio® for hypercholesterolemia [

26,

27,

28]. Similarly, the use of nanocrystals in formulations such as Anjeso® has increased the solubility of BCS Class II drugs by employing specialized dissolution techniques with apparatus 2 containing a phosphate buffer and surfactants [

38]. Long-acting injectable nanosuspensions, such as Invega Hafyera®, use flow-through cell dissolution methods and optimized media to improve in vivo prediction [

45,

46]. Similarly, for complex nano-delivery systems like Abraxane®, continuous flow dialysis in human plasma is critical for accurate dissolution characterization [

48]. A comprehensive review of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), with a focus on their roles in genetic disorder treatment (Onpattro®), cholesterol management (Leqvio®), and vaccine delivery (Spikevax®), as well as specific dissolution testing methods for each application [

35]. A thorough examination of liposomal nanoformulations, contrasting the dissolution methods of Onivyde® (reverse dialysis) and Doxil® (continuous flow dialysis), and emphasizing their relevance to physiological conditions [

27,

39]. The discussion focuses on various nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems, comparing dissolution methods for nanocrystals such as Anjeso® and Invega Hafyera®, and emphasizing apparatus and media tailored to drug characteristics. It provides an in-depth analysis of polymeric nanoparticles, focusing on dissolution testing for Emend® and Aristada® based on their release mechanisms [

29,

37]. Nanoemulsions, such as Neoral®, Diprivan®, and Rybelsus®, are investigated with a focus on biorelevant media and pH changes. Complex nano-delivery systems, such as albumin-bound nanoparticles, iron-carbohydrate nanocomplexes, and solid lipid nanoparticles, are also discussed, along with dissolution testing strategies. These advancements highlight the importance of integrating nano-formulation design with appropriate dissolution testing methods that take into account the unique physicochemical properties and release mechanisms of nanoscale drug delivery systems.

1.2. Important Considerations for Dissolution Testing of Nanoparticles

1.2.1. Particle Size and Surface Area

Nanoparticles are being increasingly used in drug delivery to overcome challenges of low solubility and poor permeability associated with conventional formulations. According to Nernst–Brunner equation, the rate of dissolution of particle is directly linked to its surface area and concentration at solid-liquid interface. Therefore, disintegrating tablets and powders, which have high surface area are frequently used in immediate-release dosage forms. The surface area can be increased further with nanoparticles, allowing faster dissolution. Abraxane (nab-paclitaxel) is an albumin-bound nanoparticle formulation of paclitaxel (130 nm) that improves tumor penetration. It allows for higher dosing and has a 50% better response rate in metastatic breast cancer than Taxol [

48].

Small size of nanoparticles allows them to easily cross cellular membranes to reach the target site of action. However, in-vitro dissolution testing of nanoparticles is challenging due to their small size, which tend to aggregate due to high surface area, high surface free energy for Vander-Walls interaction, and cohesiveness. This could demonstrate the dissolution profile similar to larger aggregated particles. Moreover, size reduction may lead to further decrease in wettability of hydrophobic drugs, which is a major problem associated with nano-formulations, highlighting the need for more effective solutions. Emend, a nanocrystal formulation of a prepitant, can increase the drug's dissolution rate and bioavailability by nearly fourfold. This leads to more stable plasma levels and greater antiemetic efficacy which approved for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting [

29].

1.2.2. Selection of Dissolution Medium

The selection of media volume and composition will majorly depend on the solubility and stability of the drug, route of administration, and intended site of action along with stability of the whole system over the testing time span. Applicability of the method is ultimately determined by its accuracy and precision in identifying the variations and similarities in release kinetics. In previous studies, artificial human blood plasma, artificial synovial fluid and simulated cerebrospinal fluid have been used as release medium [

49,

50]. For robust testing, the composition of complex natured medium needs to be simplified while keeping the physiological parameters constant (pH and osmotic pressure) [

51]. Moreover, in-vitro dissolution testing of nanoparticles may be performed under non-sink conditions besides mostly preferred sink conditions [

52]. The release kinetics can be influenced by presence of solubilizers as well as varying stirring rates [

53,

54,

55]. For marketed nanoformulations, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.1% (w/v) sodium lauryl sulfate was used as a dissolution medium for Doxil® (doxorubicin liposomal formulation), allowing for appropriate differentiation between different liposomal formulations [

56]. Similarly, simulated gastric fluid (SGF, pH 1.2) supplemented with 0.5% Tween 80 was used to test the dissolution of Abraxane® (albumin-bound paclitaxel nanoparticles), which demonstrated faster dissolution rates than conventional paclitaxel formulations [

57].

1.2.3. Filtration of Aliquots

The dissolution study involves different steps: running the dissolution test in vessel or cell, withdrawing, filtering, and analysing the aliquots. Filtration is crucial component in dissolution test as it removes undissolved drug particles from the sample. As drug particles get smaller, they tend to aggregate more readily and hence filtration of aliquots becomes more challenging.

Most commonly used conventional filters in dissolution study includes cannula tip filters and syringe filters. These filters present several challenges when used with nanoparticles. Size of cannula tip filters is too large (ranging from 1 to 70 microns) for filtering of nanoparticles. Although, syringe filters can screen particles as small as 0.2 microns, but they can still be excessively larger or encounter additional issues like back pressure (due to particle aggregation and damage the filter) or artificial dissolution during filtration of nanoparticles. Additionally, conventional filters of smaller size have also been explored, but they have not been successful due to their proneness to blockage, leading to inefficient filtration and undesirable outcomes. Despite these challenges, conventional filters remain a viable option for filtration applications. Besides conventional filters, dialysis membrane is also widely used filtering aid for nanoparticles.

Furthermore, even after collecting the aliquot into the test tube or HPLC vial, the undissolved particles may continue to dissolve. Consequently, drug concentrations may rise and fluctuate, which distort the dissolution results. These problems associated with both conventional and dialysis filtration methods may lead to inaccurate data as well as dissolution rates that don't align with in-vivo test results. The USFDA has approved eleven microsphere and fourteen liposome formulations. Further, in-vitro testing methods must be developed to ensure their efficacy and safety, and support the product development process [

58]. The US and European regulatory agencies recommended various types of apparatus including paddle, basket, flow-through cell for in –vitro dissolution study of formulations, but not for nanoparticles. Some other non-official methods used for dissolution study include dialysis membrane, and sample and separation method [

59].

The nanoparticles can alternatively be held in a Float-A-Lyzer or comparable dialysis membrane for dissolution testing, wherein the membrane also acts as an efficient filter. However, the key drawback of this technique is improper mixing of nanoparticles within the bag which artificially delays drug release. The data from literature demonstrated that the rate-limiting step for drug dissolution in such instances is diffusion across the membrane, rather than the dissolution process itself. This diffusion barrier makes it challenging to correlate the in-vitro and in-vivo test results which is necessary for the dissolution data to be useful [

60,

61]. The dialysis membrane is the most commonly used technique for analysing the in-vitro release pattern of nanoparticles. Slide-A-Lyzer™ dialysis cassettes (MWCO 10 kDa) exhibited delayed liposomal drug release compared to in-vivo results. Furthermore, studies using cellulose dialysis tubing (MWCO 12-14 kDa) for chitosan nanoparticle drug release found that membrane diffusion frequently hinders the process, reducing the reliability of such methods for predictive analysis [

62].

The semipermeable membrane separates and helps to analyse the released or free drug from the nanoparticles. The sample and separation technique involve physical separation of drug from nanoparticles using centrifugal ultra-filtration, pressure ultra-filtration, etc. techniques. However, the timely release profile cannot be estimated using dialysis or sample separation techniques due to the associated variations observed.

Due to the lack of compendial regulatory standards, scientists used a combined approach such as the sample separation method for dissolution testing and also worked to validate the same. It combines the use of USP dissolution apparatus II with ultracentrifugation technique validated to effectively separate the free drug from samples withdrawn at different time intervals. The approach was found to be more accurate and repeatable compared to the dialysis membrane method and sample separation using the syringe filter method [

63]. Several conventional filtration methods have been tested for nanoparticle dissolution studies, with each posing unique challenges. Whatman™ glass microfiber filters (1-2.7 µm) are widely used for dissolution testing, but their large pore size makes them less effective for nanoparticles [

64]. Millipore Millex-HV PVDF syringe filters (0.45 µm) encounter back pressure issues when filtering aggregated nanoparticles [

65]. Even PALL Acrodisc® PSF GxF/GHP membrane filters (0.2 µm) tend to clog during PLGA nanoparticle filtration, emphasizing the ongoing difficulties associated with traditional filtration techniques [

66].

To address these limitations, a variety of combined or alternative techniques have been developed. For instance, Amicon® Ultra centrifugal filters (10 kDa) with USP apparatus II have been shown to be effective for mesoporous silica nanoparticle dissolution testing [

67]. Similarly, Sartorius Vivaspin® ultracentrifugation devices (3 kDa) combined with a paddle apparatus resulted in efficient drug separation from PLGA nanoparticles [

68]. Notably, centrifugal ultrafiltration with Nanosep® devices (3500 rpm for 15 minutes) has demonstrated greater repeatability and reliability in lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticle dissolution studies than traditional dialysis, paving the way for standardized testing methodologies [

69].

2. Non-Compendial Dissolution Methods

2.1. Dialysis Membrane Method

This method is used to determine in-vitro drug release kinetics as well as establish the IVIVC for nanocarriers. The release of drug from donor to acceptor compartment is limited by a barrier, i.e. diffusion-limited process. Calibration experiments can be performed to confirm the diffusion barrier properties of the membrane by placing the formulation in various membranes with different pore sizes. The accumulation of free drug in donor compartment indicates rate of drug release is greater than its penetration rate across the membrane, which may be overcome with selection of a membrane with suitable pore size.

The dialysis membrane is soaked in desired media (Type I water, Aqueous polysorbate 80) for 24 hours before its use. The donor compartment is comprised of a drug solution placed inside the membrane, releasing the drug in same compartment, which further permeates across the membrane into the acceptor compartment. However, the membrane may cause inaccurate interpretation of drug release, highlighting differences in drug release profiling compared to ultracentrifugation method.

The external forces in ultracentrifugation method may also impact drug release, resulting in an inaccurate comparison. Several mathematical models were developed to determine the precise drug release profile based on the type of nanocarriers. A dialysis membrane with the USP type IV apparatus was also used for in-vitro dissolution testing. Further, after dissolution study, the dialysis membrane and donor compartment both were analysed for estimation of free drug as well as nanocarrier entrapped drug. This helps to quantify the amount of drug released but bound to donor compartment. The mean size of dispersed nanoparticles was also measured at the end of each run [

70,

71,

72,

73].

The dialysis membrane technique is widely applied in nanocarrier systems. For example, a cellulose dialysis membrane was used to study doxorubicin release from polymeric nanoparticles in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), which revealed different release patterns than direct sampling [

74]. Similarly, regenerated cellulose dialysis tubing was used to assess paclitaxel release from lipid nanoparticles, which demonstrated a biphasic release pattern with an initial burst followed by sustained release [

75]. The membrane's diffusion barrier properties were confirmed by parallel experiments with free drug solutions. Researchers used the dialysis bag technique with Float-A-Lyzer® G2 to study insulin release from PLGA nanoparticles, emphasizing the role of membrane pore size in drug accumulation [

76]. Another study compared dialysis with ultracentrifugation for itraconazole-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles, and found that dialysis resulted in slower apparent release rates [

77].

The integration of dialysis membranes and flow-through systems has produced promising results. One study modified a USP type IV apparatus with a dialysis adapter to allow for continuous flow dissolution testing of liposomal formulations while preserving sink conditions and nanostructure integrity [

78]. Another approach investigated PLGA-PEG nanoparticles using dialysis cassettes and a mathematical model to account for drug-membrane interactions. This method used post-dissolution analysis of both the membrane and donor compartments to quantify bound drug fractions, resulting in a more accurate representation of release kinetics [

79].

2.2. Sample and Separation Method

In this method, USP type I and II apparatus are frequently used, however vials can also be used in case of small volume of media. The drug loaded nanoparticles were placed in a suitable dissolution media maintained at constant temperature eunder continuous stirring to promote wetting and avoid aggregation of particles. The selection of dissolution media is based on the solubility and stability of the drug. The drug release from nanoparticles is estimated by physically separating and analysing the samples at predefined time intervals [

13,

80]. Advantages and limitations of various non-compendial dissolution test methods are summarized in

Table 2.

3. Compendial Dissolution Methods and Its Modifications

The compendial method and its modification have been used to test the drug release from nanocarriers. Moreover, compendial methods such as USP type I and II may use limited volume of media for dissolution testing. However, USP type IV (flow-through cell) uses an infinite volume of dissolution medium both for open loop and closed loop setups. All the compendial USP apparatus were featured in

Figure 3. [

84].

3.1. USP Type-I (Basket) Apparatus

The construction and specifications of USP basket (type 1) apparatus is provided in USP chapter ‘<711> Dissolution’ [

85]. This apparatus is commonly used for in-vitro drug release testing from conventional dosage forms such as tablets and capsules.

However, use of a basket design for drug release study from nanoparticles is challenging due to its structural features. Previous study reported no discriminatory results between different formulations of griseofulvin or cefuroxime axetil for in-vitro drug release tested using basket design. This was attributed to the tendency of nanoparticles to aggregate into different sizes and shapes within the basket, affecting their water holding and wetting capacity [

86,

87]. Moreover, in-vitro drug release from polymeric films of griseofulvin nanoparticles using basket apparatus demonstrated a direct correlation between dissolution rate and the agitation speed [

87]. However, low shear force within basket was found to be responsible for aggregation of nanoparticles or adherence of film to the basket wall. The basket method was deemed unsuitable for comparing dissolution profiles based on particle size, as both microparticles and nanoparticles exhibited similar dissolution profiles at high agitation speed [

87].

In another study, similar problems were reported with use of basket method to evaluate the release from unprocessed crystalline, and processed amorphous nanoparticles of cefuroxime axetil. The nanoparticles immersed in dissolution medium using the basket appeared to float on the surface. Initial rapid followed by slow rate of drug dissolution from particles was observed attributed to their aggregation [

86].

3.1.1. Modified Cylinder in USP Type-I Apparatus

A modified USP type 1 apparatus with membrane diffusion cylinder (a flat-bottom cell with the opening covered by a dialysis membrane) was used to test the drug release from rifampicin and moxifloxacin hydrochloride loaded gelatin and polybutyl cyanoacrylate nanoparticles. This modified assembly was only able to detect the faster rate of in-vitro drug release from gelatin nanoparticles under forced degradation (enzymatic) than non-forced (normal) conditions. Moreover, the distinct release mechanisms for both drugs from gelatin nanoparticles were discernible using the modified cylinder method [

54,

84].

Modified cylinder method used for testing in-vitro drug release may offer several advantages [

88]:

It can be used to perform test under sink conditions

It can resemble in-vitro dissolution profiles with in-vivo drug release mechanisms up to the maximum extent.

It can distinguish between release profiles from formulations with variable composition.

It can distinguish and help understand the in-vitro drug release mechanism from nanoparticles in various media with low standard deviation in dissolution data compared to dialysis bag method.

This was attributed to the constant surface area and constant hydrodynamic conditions at the membrane’s surface offered by modified cylinder. However, a slight variation in hydrodynamic conditions was reported at the dialysis bag’s surface while stirring.

Use of modified cylinder in standard dissolution test apparatus is advantageous than dialysis bag [

89].

3.2. USP Type-II (Paddle) Apparatus

The construction and specifications of USP paddle (type 2) apparatus is same as for basket (Type 1) apparatus except the basket is replaced with paddle assembly [

85].

The dosage form to be tested is allowed to sink at the bottom of the vessel before starting the dissolution test. A suitable sinker device (wire helix) made up of nonreactive material may be used for dosage forms which tend to float during test [

85].

3.2.1. Modified Dispersion Releaser in USP Type-II Apparatus

Estimation of accurate rate of in-vitro drug release from nanoparticles using USP type 2 (paddle) apparatus is challenging as like USP type 1 method. This was due to the common issues such as aggregation, agglomeration, and inadequate water absorption by nanoparticles along with maintaining non-sink condition.

Moreover, use of sink conditions may create problems in differentiating dissolution profiles of nano-formulations with varying compositions or properties. Liu et al. [

56] employed wet milling approach for preparation of indomethacin nanosuspensions with three different particle sizes. The study examined the impact of agitation speed and medium pH on dissolution rate of different sized particles. The sample amount to saturation solubility ratio was varied to produce dissolution profiles under sink and non-sink conditions. The study reported that increasing the sample amount to the saturation solubility of drug resulted in the slowest dissolution rate and best differentiating dissolution profiles. However, use of excessive sample or sink conditions can accelerate dissolution rate and reduce the ability to distinguish between different dissolution profiles. The study found that non-sink conditions were preferable to sink ones for comparing dissolution profiles of different particle sizes of Indomethacin nanosuspensions. Moreover, while the agitation speed seemed to have little impact on the dissolution profiles, but the low solubility achieved by selecting a suitable pH of the media found to assist in distinguishing dissolution profiles.

Yang et al. [

57] employed a modified tri-axial electrospinning technique to prepare heterogeneous nanoscale drug depots in form of core-shell fibres using ferulic acid as a model drug and cellulose acetate as a filament-forming polymeric matrix. The in-vitro dissolution test was performed using a paddle method (Chinese Pharmacopoeia) with 900 mL of 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline pH 7.0 maintained at 37 ± 1 °C under sink conditions and continuous stirring (50 rpm). The fibres demonstrated nearly zero-order release over 36 hours with no initial burst release and low tailing off compared to monolithic fibres, which showed burst release with considerable tailing-off.

Attariet al. [

18] developed nanosuspensions of Ibuprofen (BCS class II drug), and Aprepitant (BCS class IV drug) separately using a combinative approach and evaluated for several parameters including in –vitro drug release using the USP type II apparatus. The release of both drugs was found to be improved for nano-formulations compared to their pure form.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating modifications of the dispersion releaser in the USP Type-II (paddle) dissolution apparatus for enhanced evaluation of nanoformulations. These adaptations address limitations of conventional wire helix sinkers by promoting uniform agitation and reproducible release profiles in biorelevant media.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating modifications of the dispersion releaser in the USP Type-II (paddle) dissolution apparatus for enhanced evaluation of nanoformulations. These adaptations address limitations of conventional wire helix sinkers by promoting uniform agitation and reproducible release profiles in biorelevant media.

While establishing quality standards for nanomedicines, it is recommended to harmonize the use of equipment or technology for dissolution testing between various countries or regions. Wacker and colleagues [

90] developed the dispersion releaser technology to address the problem of drug release testing of nanomedicines. Dispersion releaser consist of a dialysis cell (donor compartment) attached to a shaft stirrer and a dissolution vessel (acceptor compartment) in the USP type-II apparatus (

Figure 1) [

85,

90]. O-rings, or rubber rings, are used to secure the dialysis membrane to the hollow cylinder structure (sample holder). The dispersion releaser exhibited better hydrodynamics than conventional dialysis setups attributed to the use of two separate stirrers i.e. one inside (in donor cell) and another outside (in acceptor vessel) [

53,

88,

91]. A continuous stirring of the liquid in the donor compartment contributes to build the membrane pressure that guide the flow of media to the membrane. To further ensure that the medium composition does not impede the separation process, a number of biorelevant media were used during drug release studies [

88].

This technology was explored for drug release testing from polymer nanoparticles [

84], natural polymeric microparticles [

92] and liposomes [

93]. Previous reports show dispersion releaser can be used for testing of nano-formulations as well as for distinguishing formulation variations [

84,

89,

91]. The dissolution test must be based on the harmonised compendial equipment suggested by various pharmacopoeias. Moreover, this technology should enable testing of nano-formulations for various objectives, including quality control and biorelevant release studies during formulation development [

88].

Heng et al. [

59] studied the suitability of different types of dissolution apparatus (the paddle, rotating basket, a dialysis method, and flow-through cell) for discriminating the rate of dissolution of cefuroxime axetil nanoparticles based on their size. In the dialysis method, even the use of high molecular weight cut-off membrane created an additional barrier to the drug dissolution, thereby reducing rate of dissolution. However, the paddle approach initially showed similar dissolution rates, but eventually slowed down for nanosized drugs due to tendency of nanoparticles to agglomerate, which reduced their surface area as well as rate of dissolution. In case of basket apparatus, nanoparticles initially showed higher dissolution but eventually slowed down than the unprocessed form. This was indicative of an initial forced wetting by submerging the sample into medium. Further, adhesion of the aggregates to the basket walls was another issue with this technique. Additionally, both the paddle and basket methods demonstrated common issue of floating of nanoparticles over the surface of dissolution medium which was responsible for poor wetting and associated significant heterogeneity in the dissolution profiles of nanoparticles. The study recommended the flow-through cell as the most robust dissolution method for the nanoparticulate system [

59].

3.3. USP Type-IV (Flow-Through Cell) Apparatus

It includes a water bath to keep the dissolution media at 37 ± 0.5°C, a flow-through cell, and a reservoir and pump for medium. The cell size (volume) to be used is provided in the individual monograph [

89].

The dissolution medium is forced upward through the flow-through cell by the pump. Standard flow rates for the pump are 4, 8, and 16 mL/min, with a delivery range of 240 to 960 mL/h. It must provide a steady flow (±5% of the nominal flow rate); the sinusoidal flow profile pulses at a rate of 120 ± 10 pulses per minute. Alternate option of a pump without pulsation is also available. Procedures for dissolution tests using a flow-through cell should be described in terms of rate and any pulsation [

85].

A flow-through cell is composed of the transparent and inert material, and vertically positioned that features a filter system to hold undissolved particles from escaping from the top of the cell. The cell has standard diameters of 12 and 22.6 mm. The bottom cone is filled with small glass beads (about 1 mm in diameter), with one bead of approx. 5 mm kept at the apex to protect the fluid entry tube. Additionally, a tablet holder is provided to hold special dosage forms, such as inlay tablets. The cell is submerged in a water bath to maintain constant temperature (37 ± 0.5 °C) [

85].

3.3.1. Modified Dialysis Adaptor in USP Type-IV Apparatus

The flow-through cell is appropriate for studies requiring small amounts of medium since it can be utilised as a closed loop system when the medium is continually recirculated through the cell [

40,

89]. This configuration can differentiate nanoparticulate formulations based on their dissolution profiles for varying sizes [

80]. However, open loop system requires large (infinite) volume of fresh medium, continually streaming through the cell, potentially limiting or preventing analytical measurement of small quantities of drug [

84,

88,

94].

Sievens-Figueroa et al. [

95] compared USP I and IV apparatus for discriminating the dissolution rates of griseofulvin nanoparticles and microparticles-loaded strip-films using sodium dodecyl sulfate as a dissolution medium. USP IV comprises a flow through cell with an internal diameter of 22.6 mm in a close loop design, requiring less volume of medium (without compromising sink conditions) compared to the basket method. It has been reported that USP I apparatus was unable to distinguish between the varying dissolution rates of griseofulvin particles based on their size. Conversely, USPIV found to efficiently discriminate between griseofulv in nanoparticles and microparticles integrated into strip-films based on their rate and extent of dissolution. Moreover, best discrimination can be achieved by placing the strip-film between glass beads as well as by using a flow rate of 16 ml/min. The ability of USP IV to offer better control over the strip-film positioning may have further impact on dissolution rate. Therefore, comprehensive research is needed to completely understand these impacts. These findings showed the excellent discriminatory power of the USP IV apparatus based on particle size, indicative of its suitability as a testing tool in the development of poorly soluble drug nanoparticles-loaded strip-films [

90].

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of a dialysis adaptor-based USP Type-IV (flow-through cell) apparatus configured in a closed-loop system for precise in vitro release assessment of nanoformulations. This setup overcomes sink condition limitations and filter clogging issues associated with nanoparticulate systems like liposomes or nanocrystals, enabling accurate, reproducible release profiling in biorelevant media under hydrodynamically standardized conditions compliant with USP.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of a dialysis adaptor-based USP Type-IV (flow-through cell) apparatus configured in a closed-loop system for precise in vitro release assessment of nanoformulations. This setup overcomes sink condition limitations and filter clogging issues associated with nanoparticulate systems like liposomes or nanocrystals, enabling accurate, reproducible release profiling in biorelevant media under hydrodynamically standardized conditions compliant with USP.

The compendial USPIV dissolution apparatus can be modified with a unique dialysis adaptor placed inside the flow-through cell in upright position (

Figure 2) [

96]. The adapter design comprised of a cylindrical structure, the ends of which are sealed by fixing the dialysis membrane using O-rings,as like the dispersion releaser cell. This dialysis adapter-based USP IV apparatus combines the benefits of the dialysis sac method and a compendial standardized apparatus. Moreover, this approach found to prevent issues that are prevalent in traditional dialysis procedures, such as lack of agitation, violations of sink conditions, and filter clogging in USPIV. The modified USP 4 setup demonstrated greater discriminatory ability and robustness for in-vitro release testing of colloidal dosage forms (emulsions, nanosuspensions, and liposomes) compared to conventional stirred beaker dialysis setups (dialysis sac and reverse dialysis methods) [

84,

97]. Applications of various compendial and modified compendial in-vitro dissolution test methods are summarized in

Table 3.

Figure 3.

Comprehensive schematic illustration of modern compendial dissolution apparatuses as per USP, highlighting Apparatus 1 (basket), Apparatus 2 (paddle), Apparatus 3 (reciprocating cylinder), Apparatus 4 (flow-through cell), Apparatus 5 (paddle over disk), Apparatus 6 (rotating cylinder), and Apparatus 7 (reciprocating holder) for standardized in vitro testing of oral solid dosage forms including nanoformulations. Each apparatus maintains precise hydrodynamic conditions at 37°C ± 0.5°C, with typical volumes of 500 - 4000 mL for Apparatus 1/2, agitation rates of 25 - 150 rpm, and flow rates of 4 - 16 mL/min for Apparatus 4, enabling discrimination of release profiles under sink or non-sink conditions while simulating gastrointestinal transit. These designs address specific challenges like floating dosage forms, filter clogging with nanoparticles, and controlled-release kinetics, ensuring reproducibility and regulatory compliance in biopharmaceutics classification and quality control.

Figure 3.

Comprehensive schematic illustration of modern compendial dissolution apparatuses as per USP, highlighting Apparatus 1 (basket), Apparatus 2 (paddle), Apparatus 3 (reciprocating cylinder), Apparatus 4 (flow-through cell), Apparatus 5 (paddle over disk), Apparatus 6 (rotating cylinder), and Apparatus 7 (reciprocating holder) for standardized in vitro testing of oral solid dosage forms including nanoformulations. Each apparatus maintains precise hydrodynamic conditions at 37°C ± 0.5°C, with typical volumes of 500 - 4000 mL for Apparatus 1/2, agitation rates of 25 - 150 rpm, and flow rates of 4 - 16 mL/min for Apparatus 4, enabling discrimination of release profiles under sink or non-sink conditions while simulating gastrointestinal transit. These designs address specific challenges like floating dosage forms, filter clogging with nanoparticles, and controlled-release kinetics, ensuring reproducibility and regulatory compliance in biopharmaceutics classification and quality control.

4. Factors Affecting Dissolution Rate of Nanoformulations

Several formulation and physicochemical variables govern the dissolution rate of nanoformulations, including the primary particle size (smaller particles provide larger surface area and thinner diffusion boundary layer. Thus accelerating dissolution, solid-state properties such as crystallinity and polymorphic form (amorphous or high-energy polymorphs usually dissolve faster than stable crystalline forms). Moreover, stabilizers control surface characteristics where the choice and concentration of surfactants/polymers influence wetting, steric/electrostatic stabilization, and risk of aggregation, which can either enhance or reduce dissolution. In addition, the tendency of nanoparticles to aggregate during processing or storage, the presence of wetting agents and disintegrants in solidified dosage forms, and the composition of the dissolution medium (pH, ionic strength, and biorelevant surfactants such as bile salts) further modulate the effective surface area and concentration gradient driving diffusion, thereby significantly affecting dissolution behavior of nanoformulations. Several factors that can affect the rate of dissolution of nano-formulations were described below.

4.1. Composition of Dissolution Medium: pH, Ions, and Concentration

Chemical composition of the dissolution media is the key factor that affects the dissolution of nanoparticles. The selection of medium for dissolution testing depends on the intended route of administration as well as site of action. The media selected should be adjusted with a pH and temperature similar to the physiological or in-vivo site of release. Moreover, the formulation should be prepared in such a way that it exhibits the maximum rate of release in the microenvironment of action site [

98,

99].

Jainet al. [

100] reported the pH of normal cells in neutral range, while that of malignant cells in acidic range (pH 5–5.5). The higher rate of doxorubicin release from PEGylated NPs in acidic pH 5 showed greater drug availability at tumour site compared to normal cells (pH 7.4) [

101]. Enteric coated particles protect the release of drug in acidic pH 1.2 (less than 5–10% drug release) followed by more than 80% drug release in the intestinal pH range (pH 5.5-6.8). This rise in release rate was attributed to the use of a pH-sensitive polymer that protects drug in acidic pH as well as reduction in particle size that helps the drug to dissolve more readily after releasing in intestinal pH [

101].

Moreover, the composition of simulated biological fluid can affect saturation concentration of nanoparticles and dissolution kinetics [

102]. The ability of ionic or organic molecules present in the dissolution medium, to form more or less soluble complexes with released ions will either enhance or supress the dissolution of nanoparticles [

103]. For instance, in contrast to the chloride-free control, the presence of a small amount of chloride can considerably supress the release rate of soluble Ag species [

104].

4.2. Solubility of Drug in Dissolution Medium

The solubility of a drug in the dissolution medium significantly impacts the dissolution rate of nanoparticles. The solubility and hence dissolution of drug in release medium was found to be affected by several factors including its size and shape, surface area, wettability, and state (amorphous or crystalline) [

94,

105,

106]. If the drug entrapped in nano-formulation has poor wettability, then its release will be compromised. The loaded drug must have good solubility in the intended release media [

107]. Moreover, the surface properties of nanoparticles, such as surface charge and hydrophobicity, can influence their interaction with the dissolution medium and hence drug dissolution. Additionally, the type of polymer used in polymeric nanoparticles can control the release of the drug, influencing the dissolution rate [

108].

4.3. Surface Area-to-Volume Ratio

Nano-sized particles have superior dissolving capabilities due to their larger surface-area-to-volume ratio compared to microparticles. Furthermore, nanoparticles have a higher percentage of atoms around their corners and edges rather than on their flat terraces compared to larger particles. This helps ions and small clusters present at the surface to separate from nanoparticles more easily due to high content of free energy [

98,

109,

110].

Nakaraniet al. prepared nanosuspension for oral delivery of itraconazole. The in-vitro dissolution studies of nanosuspension showed more than 90% drug dissolution in 10 minutes compared to the 10% and 17% drug release from the pure drug and the marketed formulation (Canditral®, capsule), respectively [

111]. Sun etal. [

112] stated that a small particle size, a larger surface area, a thinner diffusion layer, and higher saturation solubility, all significantly boost the rate of dissolution by increasing the particle surface area and wetting by media, and thereby enhancing bioavailability.

4.4. Kinetic Size Effects

It is a process where a high concentration of the dissolved species initially appears, and then the concentration decreases until saturation is attained. The kinetic size effect usually occurs for nanoparticles, and the effect found to be increased with decrease in particle size [

113]. Kinetic size effects describe a transient, size dependent dissolution process in which very small nanoparticles dissolve so rapidly that a high, often supersaturated, concentration of dissolved drug is generated initially, followed by a gradual decline toward the equilibrium saturation solubility as precipitation and recrystallization proceed. In nanoformulations, the large specific surface area, higher surface energy, and thinner diffusion layer around smaller particles markedly increase the dissolution velocity, so the magnitude of this kinetic solubility peak becomes more pronounced as particle size decreases. This phenomenon is therefore characteristic of nanoscale systems rather than bulk material, and is an important contributor to the enhanced apparent solubility and accelerated dissolution rate observed for drug nanocrystals and related nanoformulations [

98,

113,

114].

4.5. Presence of Strong Oxidants

The presence of strong oxidising agents such as oxygen, H2O2, HO2-, OCl-, as well as sunlight were reported to alter the dissolution rate of nano-formulations. For instance, the dissolution from silver nanoparticles was found to be improved in presence of oxygen and H2O2. The presence of strong oxidizing agents such as dissolved oxygen, hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), hydroperoxide ions (HO₂⁻), hypochlorite (OCl⁻), and sunlight exposure has been reported to significantly alter the dissolution rate of nanoformulations by promoting oxidative surface reactions that enhance material breakdown and ion release. For instance, silver nanoparticles exhibit accelerated dissolution in the presence of oxygen and H₂O₂, where these oxidants facilitate the conversion of metallic Ag⁰ to more soluble Ag⁺ ions through redox processes, leading to faster overall solubilization compared to inert conditions. This effect arises from the high surface reactivity of nanoparticles, making them particularly susceptible to environmentally relevant oxidants during in vitro testing or in vivo exposure.

Beyond silver nanoparticles, similar oxidative enhancement occurs with other metallic or metal oxide nanoformulations, such as those containing zinc oxide or iron oxides, where strong oxidants disrupt lattice structures and increase the effective surface area available for dissolution. Sunlight, acting via photochemical reactions, further amplifies this by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) that catalyze surface etching, a phenomenon observed in environmental and physiological contexts with dissolved O₂ or H₂O₂. These factors highlight the importance of controlling redox conditions in dissolution media to accurately predict nanoformulation performance and ensure stability in biorelevant environments. [

98,

115]

4.6. Aggregation of Particles

Aggregation is a crucial factor in dissolution of nanoparticles, where secondary particles are formed by bonding of primary particles, attributed to the reduced electrostatic repulsion between particles [

116,

117,

118]. This reduces the external surface area available, affecting the rate and extent of dissolution [

98,

116]. Further, agitation speed also found to affect the aggregation of nanoparticles. Therefore, aggregation state of particles limits the sites available for oxidation and exhibits inverse relationship with rate of dissolution [

119,

120]. Aggregation of nanorods found to almost or entirely inhibit its dissolution [121].

Aggregation of nanoparticles can overcome by chemically attaching the ligands of stabilizing substance to the particles surface. This makes nanoparticles more stable and resilient to changes in solution pH and concentration (stay in a dispersed state). Moreover, the type of ligand and nature of chemical bonding with the particle surface found to decide the rate of dissolution [122,123]. Previous research findings reported an increase in dissolution rate of polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilised nanoparticles compared to citrate-stabilized nanoparticles [124].

5. Advanced Dissolutiontechniques

Several issues associated with the current methods are resolved by in-situ drug release estimation. In-situ approach is based on principles like turbidimetry, light scattering, and voltammetry. The instrument developed is Sirius®,Diss Profiler. The in-situ probes monitor the timely concentration by measuring the UV absorbance of free drug released from the nanoparticle without separating from the carrier system. The nanocarriers cause scattering of light. The instrument compensates for the amount of UV light lost by using the concepts of Tyndall-Rayleigh scattering theory, collecting data for every second release.More error is associated with highly turbid samples, which is not possible with ionic and some other types of drugs. These kinds of techniques are being optimized to lessen any potential limitations, and could prove very useful, if successfully emerge by overcoming all of the limitations, in nano-formulations release studies [125,126].

Figure 4.

Conceptual evolution from traditional separation-based methods (dialysis bags, sample-and-separate ultrafiltration/centrifugation) to advanced in-situ nano-dissolution testing paradigms for real-time, separation-free assessment of nanoparticulate drug release. Conventional approaches (left) suffer from membrane diffusion limitations, filter clogging, and artificial kinetics, while in-situ techniques (right) employ fiber-optic UV-VIS spectroscopy, potentiometric sensors, dynamic light scattering (DLS), fluorescence, or voltammetry directly in the dissolution vessel at 37°C, enabling continuous monitoring without sampling disturbances under USP-compliant hydrodynamics. This shift enhances biorelevance, resolves supersaturation/precipitation dynamics, and supports IVIVC for nanoformulations like liposomes and nanocrystals.

Figure 4.

Conceptual evolution from traditional separation-based methods (dialysis bags, sample-and-separate ultrafiltration/centrifugation) to advanced in-situ nano-dissolution testing paradigms for real-time, separation-free assessment of nanoparticulate drug release. Conventional approaches (left) suffer from membrane diffusion limitations, filter clogging, and artificial kinetics, while in-situ techniques (right) employ fiber-optic UV-VIS spectroscopy, potentiometric sensors, dynamic light scattering (DLS), fluorescence, or voltammetry directly in the dissolution vessel at 37°C, enabling continuous monitoring without sampling disturbances under USP-compliant hydrodynamics. This shift enhances biorelevance, resolves supersaturation/precipitation dynamics, and supports IVIVC for nanoformulations like liposomes and nanocrystals.

6. Conclusions

In-vitro dissolutionis a crucial regulatory requirement for drug formulation, as it is an indicator of product quality, and correlates with in-vivo release that helps in developing effective formulation.The method to be used for in-vitro drug release study should mimic the in-vivo condition as well as should allow for IVIVC. However, there are no compendial methods or standard procedures reported for conducting release study of nano-formulations. The present article focuses on compilation of non-compendial and modified compendial techniques developed for in-vitro releasetesting of nano-formulations. The modified USP IV method was found to be most efficient for in-vitro dissolution testing of nano-formulations. Future research should focus on developing more efficient and advanced in-vitro dissolution techniques including in-situ methodologies to discriminate nano-formulations based on variations in composition and/or properties of nano-formulations.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Minor Research Project Grants of Jain University (Deemed-to-be) and Creative Pioneering Research Grant from SNU R & D Foundation of Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

References

- MG, K.; V, K.; F, H. History and Possible Uses of Nanomedicine Based on Nanoparticles and Nanotechnological Progress. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 2015, 6(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, K.; Raghuvanshi, S. Oral Bioavailability: Issues and Solutions via Nanoformulations. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2015, 54(4), 325–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, S. K.; Dilnawaz, F.; Krishnakumar, S. Nanotechnology in Ocular Drug Delivery. Drug Discov. Today 2008, 13(3–4), 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, R.H.; Gohla, S.; Keck, C. M. State of the Art of Nanocrystals – Special Features, Production, Nanotoxicology Aspects and Intracellular Delivery. Eur.J.Pharm.Biopharm. 2011, 78(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P.; Rab, S.; Suman, R. Applications of Nanotechnology in Medical Field: A Brief Review. Glob. Health J. 2023, 7(2), 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S. A. A.; Saleh, A. M. Applications of Nanoparticle Systems in Drug Delivery Technology. Saudi Pharm.J. 2018, 26(1), 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shen, H.; He, Q.; Wu, Z.; Liao, W.; Yuan, M. Application of the Nano-Drug Delivery System in Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevanandam, J.; Chan, Y.S.; Danquah, M. K. Nano-Formulations of Drugs: Recent Developments, Impact and Challenges. Biochimie 2016, 128–129, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padma, D. V.; et al. Targeted Drug Delivery: Concepts and Design. In Advances in Delivery Science and Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnaiah, Y. S. R. Pharmaceutical Technologies for Enhancing Oral Bioavailability of Poorly Soluble Drugs. J.Bioequiv. Bioavailab. 2010, 2(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesisoglou, F.; Panmai, S.; Wu, Y. Nanosizing — Oral Formulation Development and Biopharmaceutical Evaluation. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007, 59(7), 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidon, G.L.; Lennernäs, H.; Shah, V.P.; Crison, J.R. A Theoretical Basis for a Biopharmaceutic Drug Classification: The Correlation of in-vitro Drug Product Dissolution and in-vivo Bioavailability. Pharm.Res 1995, 12(3), 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Souza, S. A Review of In-vitro Drug Release Test Methods for Nano-Sized Dosage Forms. Adv.Pharm 2014, 2014, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, M.M.; Aramwit, P.; Kwon, G.S. (Eds.) Nanotechnology in Drug Delivery; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, B.G.; Mishra, V.; Raj, S. Nanoparticle Technology for Drug Delivery, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahr, A.; Liu, X. Drug Delivery Strategies for Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2007, 4(4), 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, T.; Ratre, Y. K.; Chauhan, S.; Bhaskar, L. V. K. S.; Nair, M. P.; Verma, H. K. Nanotechnology Based Drug Delivery System: Current Strategies and Emerging Therapeutic Potential for Medical Science. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 63, 102487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attari, Z.; Kalvakuntla, S.; Reddy, M. S.; Deshpande, M.; Rao, C. M.; Koteshwara, K. B. Formulation and Characterisation of Nanosuspensions of BCS Class II and IV Drugs by Combinative Method. J. Exp.Nanosci. 2015, 11(4), 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambhekar, S.S.; Breen, P. J. Drug Dissolution: Significance of Physicochemical Properties and Physiological Conditions. Drug Discov. Today 2013, 18(23–24), 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, O.; Yu, L. X.; Conner, D. P.; Davit, B. M. Dissolution Testing for Generic Drugs: An FDA Perspective. AAPSJ. 2011, 13(3), 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, C.; Xiao, Y.; Tian, B.; Gao, D.; Fan, W.; Li, G.; He, S.; Zhai, G. An Overview of In-vitro Dissolution Testing for Film Dosage Forms. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 71, 103297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsagade, P.; Khetade, R.; Nirwan, K.; Agrawal, T.; Gotafode, S.; Lade, U. Review Article of Dissolution Test Method Development and Validation of Dosage Form by Using RP-HPLC. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2021, 70(1), 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetten, L.; Mackevica, A.; Tepe, N.; Hofmann, T.; von der Kammer, F. Towards Standardization for Determining Dissolution Kinetics of Nanomaterials in Natural Aquatic Environments: Continuous Flow Dissolution of Ag Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2022, 12(3), 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, D.; Ogawa, K.; Cutler, D. J.; Chan, H.-K.; Raper, J.A.; Ye, L.; Yun, J. Pure Drug Nanoparticles in Tablets: What Are the Dissolution Limitations? J. Nanopart. Res. 2010, 12(5), 1743–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardot, J.-M.; Beyssac, E.; Alric, M. In-vitro–In-vivo Correlation: Importance of Dissolution in IVIVC. Dissolution Technol. 2007, 14(1), 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinc, A; Maier, MA; Manoharan, M; Fitzgerald, K; Jayaraman, M; Barros, S; Ansell, S; Du, X; Hope, MJ; Madden, TD; Mui, BL. The Onpattro story and the clinical translation of nanomedicines containing nucleic acid-based drugs. Nature nanotechnology 2019, 14(12), 1084–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, DC; Noble, CO; Guo, Z; Hong, K; Park, JW; Kirpotin, DB. Development of a highly active nanoliposomal irinotecan using a novel intraliposomal stabilization strategy. Cancer research 2006, 66(6), 3271–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, MB; Blair, HA. Liposomal Irinotecan: A Review as First-Line Therapy in Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Drugs 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanberg, A; Birgegård, G. Addition of aprepitant (Emend®) to standard antiemetic regimen continued for 7 days after chemotherapy for stem cell transplantation provides significant reduction of vomiting. Oncology 2015, 89(1), 31–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J; Rodriguez, A; Wang, K; Olsen, K; Wang, Y; Schwendeman, A. In vitro and in vivo characterization of Invega Sustenna®(paliperidone palmitate long-acting injectable suspension). European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2025, 207, 114613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Neoral Renal Transplantation Study Group. Cyclosporine microemulsion (Neoral®) absorption profiling and sparse-sample predictors during the first 3 months after renal transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation 2002, 2(2), 148–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italia, JL; Bhatt, DK; Bhardwaj, V; Tikoo, K; Kumar, MR. PLGA nanoparticles for oral delivery of cyclosporine: Nephrotoxicity and pharmacokinetic studies in comparison to SandimmuneNeoral®. Journal of Controlled Release 2007, 119(2), 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, NR; Bicanic, T; Salim, R; Hope, W. Liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome®): A review of the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, clinical experience and future directions. Drugs 2016, 76, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamed, K; Said, N. Polymeric albumin-free paclitaxel intraperitoneal therapy demonstrates superior efficacy over nab-paclitaxel intravenous therapy in a mouse model of metastatic ovarian cancer. Cancer Research 2015, 75 (15_Supplement), 5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosilla, J; Alonso-García, A; Salmerón-García, A; Cabeza-Barrera, J; Medina-Castillo, AL; Pérez-Robles, R; Navas, N. Analysing the in-use Stability of mRNA-LNP COVID-19 vaccines Comirnaty™(Pfizer) and Spikevax™(Moderna): A comparative study of the particulate. Vaccines 2023, 11(11), 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayode, OR; Babatunde, OA. Cabenuva®: Differentiated service delivery and the community Pharmacists’ roles in achieving UNAIDS 2030 target in Nigeria. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2021, 29(8), 815–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehret, MJ; Davis, E; Luttrell, SE; Clark, C. Aripiprazole lauroxilnanoCrystal® dispersion technology (Aristada Initio®). Clinical schizophrenia & related psychoses 2018, 12(2), 92–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J; Huang, J; Zou, C; Wu, Q; Xie, J; Zhang, X; Yang, X; Yang, S; Wu, Z; Jiang, Y; Yu, S. A phase I study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of novel intravenous formulation of meloxicam (QP001) in healthy Chinese subjects. Drug Design, Development and Therapy 2023, 2303–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabizon, AA; Gabizon-Peretz, S; Modaresahmadi, S; La-Beck, NM. Thirty years from FDA approval of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil/Caelyx): An updated analysis and future perspective. BMJ oncology 2025, 4(1), e000573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, GM. Ferric carboxymaltose: A review of its use in iron deficiency. Drugs 2015, 75, 101–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, PH; Lucchinetti, E; Zhang, L; Affolter, A; Gandhi, M; Zhakupova, A; Hersberger, M; Hornemann, T; Clanachan, AS; Zaugg, M. Propofol (Diprivan®) and Intralipid® exacerbate insulin resistance in type-2 diabetic hearts by impairing GLUT4 trafficking. Anesthesia& Analgesia 2015, 120(2), 329–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayesha, A; Wallace, RT; Mai, AP; Simpson, RG; Chaya, CJ. Iris atrophy after administration of Dexycu: Additional evidence and possible mechanism for a rare complication. American Journal of Ophthalmology Case Reports 2023, 30, 101806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorati, JM; Jin, J; Zhong, XB. siRNA drug Leqvio (inclisiran) to lower cholesterol. Trends in pharmacological sciences 2022, 43(5), 455–6. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016561472200027X. [CrossRef]

- James, J; Tang, K; Wei, T. Tesetaxel, a novel, oral taxane, crosses intact blood-brain barrier (BBB) at therapeutically relevant concentrations. Cancer Research 2019, 79 (13_Supplement), 3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L; Dyer, M; Schroeder, E; D’Souza, MS. Invega Hafyera (paliperidone palmitate): Extended-release injectable suspension for patients with schizophrenia. Journal of Pharmacy Technology 2023, 39(2), 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, HA. Paliperidone palmitate intramuscular 6-monthly formulation in schizophrenia: A profile of its use. Drugs & Therapy Perspectives 2022, 38(8), 335–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, AL; McEntee, N; Holland, J; Patel, A. Development and approval of rybelsus (oral semaglutide): Ushering in a new era in peptide delivery. Drug delivery and translational research 2022, 12(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, N. Nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (Abraxane®). In InAlbumin in medicine: Pathological and clinical applications 2016 Nov 2; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2016; pp. 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M. R. C.; Loebenberg, R.; Almukainzi, M. Simulated Biologic Fluids with Possible Application in Dissolution Testing. Dissolution Technol. 2011, No. August 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Choonara, Y.E.; du Toit, L.C.; Singh, N.; Pillay, V. In-vitro and in Silico Analyses of Nicotine Release from a Gelisphere-Loaded Compressed Polymeric Matrix for Potential Parkinson’sDisease Interventions. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10(4), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delplace, C.; Kreye, F.; Klose, D.; Danède, F.; Descamps, M.; Siepmann, J.; Siepmann, F. Impact of the Experimental Conditions on Drug Release from Parenteral Depot Systems:From Negligible to Significant. Int.J.Pharm. 2012, 432(1–2), 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; De Wulf, O.; Laru, J.; Heikkilä, T.; van Veen, B.; Kiesvaara, J.; Hirvonen, J.; Peltonen, L.; Laaksonen, T. Dissolution Studiesof Poorly Soluble Drug Nanosuspensions in Non-Sink Conditions. AAPSPharmSciTech 2013, 14(2), 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fecioru, E.; Klein, M.; Krämer, J.; Wacker, M.G. In-vitro Performance Testing of Nanoparticulate Drug Products for Parenteral Administration. Dissolution Technol. 2019, 26(3), 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zuo, J.; Bou-Chacra, N.; Pinto, T. de J. A.; Clas, S.D.; Walker, R. B.; Löbenberg, R. In-vitro Release Kinetics of Antituberculosis Drugs from Nanoparticles Assessed Using a Modified Dissolution Apparatus. Biomed Res.Int 2013, 2013, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievens-Figueroa, L.; Pandya, NatashaBhakay; Bhakay, A.; Keyvan, G.; Michniak-Kohn, B.; Bilgili, E.; Davé, R. N. Using USPI and USP IV for Discriminating Dissolution Rates of NanoandMicroparticle-Loaded Pharmaceutical Strip-Films. AAPSPharmSciTech 2012, 13(4), 1473–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; De Wulf, O.; Laru, J.; et al. Dissolution Studies of Poorly Soluble Drug Nanosuspensions in Non-sink Conditions. AAPS PharmSciTech 2013, 14, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Guang-Zhi; Li, Jiao-Jiao; Yu, Deng-Guang; He, Mei-Feng; Yang, Jun-He; Williams, Gareth R. Nanosized sustained-release drug depots fabricated using modified tri-axial electrospinning. ActaBiomaterialia 2017, Volume 53, Pages 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fecioru, E.; Klein, M.; Krämer, J.; Wacker, M.G. In-vitro Performance Testing of Nanoparticulate Drug Products for Parenteral Administration. Dissolution Technol. 2019, 26(3), 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, D.; Cutler, D. J.; Chan, H.-K.; Yun, J.; Raper, J.A. What Is a Suitable Dissolution Method for Drug Nanoparticles? Pharm.Res 2008, 25(7), 1696–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boda, K. The Next Challenge in Dissolution–Nanoparticles. Pharm.Technol 2023, 47(5). [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, C. L. P.; Chan, H.-K. Nanotechnology Versus Other Techniques in Improving Drug Dissolution. Curr. Pharm.Des 2014, 20(3), 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, DA; Colgan, ST; Langer, CS; Bandi, NT; Likar, MD; Van Alstine, L. Dissolution similarity requirements: How similar or dissimilar are the global regulatory expectations? The AAPS Journal 2016, 18(1), 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, J.; Tong, H. H. Y.; Chow, S.F. In-vitro Release Study of the Polymeric Drug Nanoparticles: Development and Validation of a Novel Method. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12(8), 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R; Chen, Y; Xie, H. In vitro dissolution considerations associated with nano drug delivery systems. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2021, 13(6), e1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, SK; Singh, C; Dora, CP; Suresh, S. Development of tamoxifen-phospholipid complex: Novel approach for improving solubility and bioavailability. International journal of pharmaceutics 2014, 473(1-2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre-Iglesias, PM; García-Rodriguez, JJ; Torrado, G; Torrado, S; Torrado-Santiago, S; Bolás-Fernández, F. Enhanced bioavailability and anthelmintic efficacy of mebendazole in redispersible microparticles with low-substituted hydroxypropylcellulose. Drug Design, Development and Therapy 2014, 1467–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, E; Brandtzaeg, OK; Vehus, T; Roberg-Larsen, H; Bogoeva, V; Ademi, O; Hildahl, J; Lundanes, E; Wilson, SR. A critical evaluation of Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters for separating proteins, drugs and nanoparticles in biosamples. Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis 2016, 120, 106–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, HV; Campbell, K; Painter, GF; Young, SL; Walker, GF. Data on the uptake of CpG-loaded amino-dextran nanoparticles by antigen-presenting cells. Data in brief 2021, 35, 106883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reguera, G; Leschine, S. Fast and efficient elution of proteins from polyacrylamide gels using nanosep® centrifugal devices. Department of Microbiology, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, Amherst. 2009.

- Modi, S.; Anderson, B. D. Determination of Drug Release Kinetics from Nanoparticles: Overcoming Pitfalls of the Dynamic Dialysis Method. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2013, 10(8), 3076–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Yuan, W.; Li, D.; Schwendeman, A.; Schwendeman, S.P. Predicting Drug Release Kinetics from Nanocarriers inside Dialysis Bags. J. Controlled Release 2019, 315, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambito, Y.; Pedreschi, E.; Di Colo, G. Is Dialysis a Reliable Method for Studying Drug Release from Nanoparticulate Systems?—A Case Study. Int.J.Pharm. 2012, 434(1–2), 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, B. J. Characterisation of Drug Release from Cubosomes Using the Pressure Ultrafiltration Method. Int.J.Pharm. 2003, 260(2), 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, KH; Lee, HJ; Kim, K; Kwon, IC; Jeong, SY; Lee, SC. The tumor accumulation and therapeutic efficacy of doxorubicin carried in calcium phosphate-reinforced polymer nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2012, 33(23), 5788–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L; Wang, X; Shen, L; Alrobaian, M; Panda, SK; Almasmoum, HA; Ghaith, MM; Almaimani, RA; Ibrahim, IA; Singh, T; Baothman, AA. Paclitaxel and naringenin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles surface modified with cyclic peptides with improved tumor targeting ability in glioblastoma multiforme. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138(111461), 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonte, P; Andrade, F; Araújo, F; Andrade, C; Neves, J; Sarmento, B. Chitosan-coated solid lipid nanoparticles for insulin delivery. Methods in Enzymology 2012, 508, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N; Goindi, S. Development and optimization of itraconazole-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for topical administration using high shear homogenization process by design of experiments: In vitro, ex vivo and in vivo evaluation. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, U; Burgess, DJ. A novel USP apparatus 4 based release testing method for dispersed systems. International journal of pharmaceutics 2010, 388(1-2), 287–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Bautista, G; Tam, KC. Evaluation of dialysis membrane process for quantifying the in vitro drug-release from colloidal drug carriers. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2011, 389(1-3), 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, M.; Atila, A.; Kadioglu, Y. Formulation and In-vitro Characterization of Eudragit® L100 and Eudragit® L100-PLGA Nanoparticles Containing Diclofenac Sodium. AAPS PharmSciTech 2010, 11(3), 1250–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothnagel, L.; Wacker, M.G. How to Measure Release from Nanosized Carriers? Eur.J.Pharm.Sci. 2018, 120, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2020/07/guidance-document-for-the-testing-of-dissolution-and-dispersion-stability-of-nanomaterials-and-the-use-of-the-data-for-further-environmental-testing-and-assessment_988b598b/f0539ec5-en.pdf.

- Budhian, A.; Siegel, S.J.; Winey, K.I. Controlling the in-vitro Release Profiles for a System of Haloperidol-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles. Int.J.Pharm. 2008, 346(1–2), 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Pharmacopeia 38, National Formulary 33; United States Pharmacopeial Convention: Rockville, MD, 2015; Vol. 1, pp 487–490.

- Heng, D.; Cutler, D. J.; Chan, H.K.; Yun, J.; Raper, J.A. What Isa Suitable Dissolution Method for Drug Nanoparticles? Pharm.Res 2008, 25(7), 1696–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wacker, M. G. Challenges in the Drug Release Testing of Next-Generation Nanomedicines – What Do We Know? Mater. Today: Proc. 2017, 4 Supplement 2, S214–S217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zuo, J.; Bou-Chacra, N.; Pinto, T. D. J. A.; Clas, S.-D.; Walker, R. B.; Löbenberg, R. In-vitro Release Kinetics of Antituberculosis Drugs from Nanoparticles Assessed Using a Modified Dissolution Apparatus. BioMed Res.Int 2013, 2013, 136590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievens-Figueroa, L.; Pandya, N.; Bhakay, A.; Keyvan, G.; Michniak-Kohn, B.; Bilgili, E.; Davé, R. N. Using USP I and USP IV for Discriminating Dissolution Rates of Nano- and Microparticle-Loaded Pharmaceutical Strip-Films. AAPS PharmSciTech 2012, 13(4), 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, F; Nothnagel, L; Gao, F; Thurn, M; Vogel, V; Wacker, MG. A comparison of two biorelevant in-vitro drug release methods for nanotherapeutics based on advanced physiologically-based pharmacokinetic modelling. EurJPharmBiopharm 2018, 127, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. Janas, M. P. Mast, L. Kirsamer, C. Angioni, F. Gao, W. Mantele, J. Dressman,M. G. Wacker, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. [Epub ahead ofprint] (2017).

- L. Jablonka, M. Thurn, M. G. Wacker, GPEN Conference (Kansas, USA) (2016).

- JonasHedberg; BlombergInger, Eva; OdnevallWallinder. In the Search for Nanospecific Effects of Dissolution of Met al.et al.lic Nanoparticles at Freshwater-Like Conditions: A Critical Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53(8), 4030–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, D.; Cutler, D. J.; Chan, H.-K.; Yun, J.; Raper, J.A. What Is a Suitable Dissolution Method for Drug Nanoparticles? Pharm.Res 2008, 25(7), 1696–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, M.S.; Nawaz, A.; Asmari, M.; Uddin, J.; Ullah, H.; Ahmad, S. Formulation Development and In-vitro/In-vivo Characterization of Methotrexate-Loaded Nanoemulsion Gel Formulations for Enhanced Topical Delivery. Gels 2023, 9(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, U.; Burgess, D. J. A Novel USP Apparatus 4 Based Release Testing Method for Dispersed Systems. Int.J.Pharm. 2010, 388(1–2), 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utembe, W.; Potgieter, K.; Stefaniak, A.B.; Gulumian, M. Dissolution and Biodurability: Important Parameters Needed for Risk Assessment of Nanomaterials. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2015, 12(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzmüller, L.; Nitschke, F.; Rudolph, B.; Berson, J.; Schimmel, T.; Koh, T. Dissolution Control and Stability Improvement of Silica Nanoparticles in Aqueous Media. J. Nanopart. Res. 2023, 25(1), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, S.; Prajapati, A.B.; Bhadra, D. Development of pH-Sensitive Polymeric Nanoparticles of Erythromycin Stearate. J.Pharm.BioalliedSci. 2016, 8(2), 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Bharti, S.; Bhullar, G.K.; Tripathi, S.K. pH-Dependent Drug Release from Drug Conjugated PEGylated CdSe/ZnS Nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 240, 122162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.K.; Dybowska, A.; Berhanu, D.; Luoma, S.N.; Valsami-Jones, E. The Complexity of Nanoparticle Dissolution and Its Importance in Nanotoxicological Studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 438, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borm, P.; Klaessig, F. C.; Landry, T. D.; Moudgil, B.; Pauluhn, J.; Thomas, K.; Trottier, R.; Wood, S. Research Strategies for Safety Evaluation of Nanomaterials, Part V: Role of Dissolution in Biological Fate and Effects of Nanoscale Particles. Toxicol. Sci. 2006, 90(1), 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levard, C.; Mitra, S.; Yang, T.; Jew, A. D.; Badireddy, A. R.; Lowry, G. V.; Brown, G. E. Effect of Chloride on the Dissolution Rate of Silver Nanoparticles and Toxicity to E. coli. Environ. Sci.Technol 2013, 47(11), 5738–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MalekiDizaj, S; ZhVazifehasl; Salatin, S; KhAdibkia; Javadzadeh, Y. Nanosizing of drugs: Effect on dissolution rate. Res PharmSci 2015, 10(2), 95–108. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4584458/.

- JernejŠtukelj, SamiSvanbäck, MikaelAgopov, KorbinianLöbmann, ClareJ.Strachan, ThomasRades, JoukoYliruusi. Direct Measurement of Amorphous Solubility.Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 11, 7411–7417. [CrossRef]

- https://manufacturingchemist.com/dissolution-of-an-immediate-release-nanoparticle-formulation-using#:~:text=One%20of%20the%20major%20challenges,with%20an%20expected%20higher%20bioavailability.

- Bian, S.-W.; Mudunkotuwa, I. A.; Rupasinghe, T.; Grassian, V. H. Aggregation and Dissolution of 4 nm ZnO Nanoparticles in Aqueous Environments: Influence of pH, Ionic Strength, Size, and Adsorption of Humic Acid. Langmuir 2011, 27(10), 6059–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, Maria; Dutta, SarodiJonak; Kuntze, Mia; Bading, Jeannette; Rüßbült, Johanna S.; Fabig, Cornelius; Langfeldt, Malte; Schulz, Florian; Horcajada, Patricia; Parak, Wolfgang J. Visualization of the High Surface-to-Volume Ratio of Nanomaterials and Its Consequences. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101(8), 3146–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakarani, M.; Misra, A.; Patel, J.; Vaghani, S. Itraconazole Nanosuspension for Oral Delivery: Formulation, Characterization and in-vitro Comparison with Marketed Formulation. DARUJ.Pharm.Sci. 2010, 18(2), 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Wang, F.; Sui, Y.; She, Z.; Zhai, W.; Wang, C.; Deng, Y. Effect of Particle Size on Solubility, Dissolution Rate, and Oral Bioavailability: Evaluation Using Coenzyme Q10 as Naked Nanocrystals. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 5733–5744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelsberger, W.; Schmidt, J.; Roelofs, F. Dissolution Kinetics of Oxidic Nanoparticles: The Observation of an Unusual Behaviour. Colloids Surf., A 2008, 324(1), 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelsberger, W.; Schmidt, J. Studies of the Solubility of BaSO4 Nanoparticles in Water: Kinetic Size Effect, Solubility Product, and Influence of Microporosity. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 115(5), 1388–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sonshine, D. A.; Shervani, S.; Hurt, R.H. Controlled Release of Biologically Active Silver from Nanosilver Surfaces. ACSNano 2010, 4(11), 6903–6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, P. M.; Barnikol, S.; Baumann, T.; Kuehn, M.; Ivleva, N. P.; Schaumann, G. E. Sorption of Silver Nanoparticles to Environmental and Model Surfaces. Environ. Sci.Technol 2013, 47(10), 5083–5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Marambio-Jones, C.; Peng, F.; Huang, X.; Damoiseaux, R.; Hoek, E. M. V. High-Throughput Screening of Silver Nanoparticle Stability and Bacterial Inactivation in Aquatic Media: Influence of Specific Ions. Environ. Sci.Technol 2010, 44(19), 7321–7328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hurt, R. H. Ion Release Kinetics and Particle Persistence in Aqueous Nano-Silver Colloids. Environ. Sci.Technol 2010, 44(6), 2169–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]