Submitted:

11 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Eligibility Criteria

Information Sources

Search Strategy

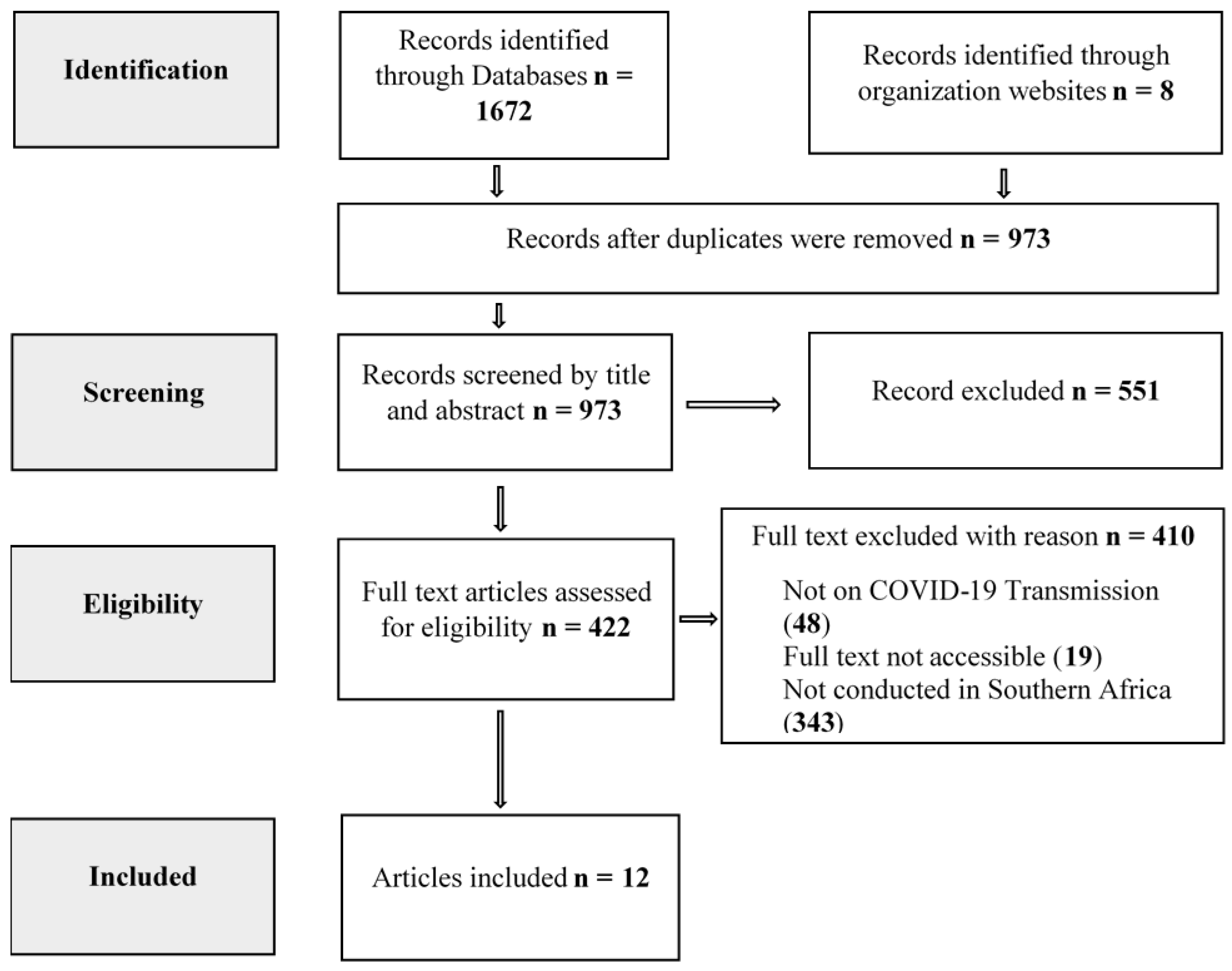

Study Selection

Data Charting and Extraction

Data Synthesis

Ethical Considerations

Results

Discussion

Geographical Distribution of Studied and Common Methods Used

Domestic Animal Species Susceptibility

Interventions and Challenges Across Regions

Conclusion

Authors’ Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Moneim, A.S.; Abdelwhab, E.M. Evidence for SARS-CoV-2 Infection of Animal Hosts. Pathogens 2020, 9, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agusi, E.R.; Allendorf, V.; Eze, E.A.; Asala, O.; Shittu, I.; Dietze, K.; Busch, F.; Globig, A.; Meseko, C.A. SARS-CoV-2 at the Human–Animal Interface: Implication for Global Public Health from an African Perspective. Viruses 2022, 14, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almendros, A. Can companion animals become infected with Covid-19? Vet. Rec. 2020, 186, 388–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: North Adelaide, South Australia, Australia, 2024.

- Bogoch, I.I.; Watts, A.; Thomas-Bachli, A.; Huber, C.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; Khan, K. Pneumonia of unknown aetiology in Wuhan, China: potential for international spread via commercial air travel. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco-Lauth, A.M.; Hartwig, A.E.; Porter, S.M.; Gordy, P.W.; Nehring, M.; Byas, A.D.; VandeWoude, S.; Ragan, I.K.; Maison, R.M.; Bowen, R.A. Experimental infection of domestic dogs and cats with SARS-CoV-2: Pathogenesis, transmission, and response to reexposure in cats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26382–26388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Sun, J.; Zhu, J.; Ding, X.; Lan, T.; Zhu, L.; Xiang, R.; Ding, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; et al. Single-cell screening of SARS-CoV-2 target cells in pets, livestock, poultry and wildlife. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choga, W.T.; Letsholo, S.L.; Marobela-Raborokgwe, C.; Gobe, I.; Mazwiduma, M.; Maruapula, D.; Rukwava, J.; Binta, M.G.; Zuze, B.J.L.; Koopile, L.; et al. Near-complete genome of SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant of concern identified in a symptomatic dog (Canis lupus familiaris) in Botswana. Veter- Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Balboni, A.; Bertolotti, L.; Martino, P.A.; Mazzei, M.; Mira, F.; Pagnini, U. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Dogs and Cats: Facts and Speculations. Front. Veter- Sci. 2021, 8, 619207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvard, Danila. Zoonotic Infections: Understanding Transmission Dynamics and Preventive Measures. Clinical Infectious Diseases: Open Access 7 (1). 2023. Available online: https://www.hilarispublisher.com/open-access/zoonotic-infections-understanding-transmission-dynamics-and-preventive-measures.pdf.

- Fang, R.; Yang, X.; Guo, Y.; Peng, B.; Dong, R.; Li, S.; Xu, S. SARS-CoV-2 infection in animals: Patterns, transmission routes, and drivers. Eco-Environment Heal. 2023, 3, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, M.; Rosolen, B.; Krafft, E.; Becquart, P.; Elguero, E.; Vratskikh, O.; Denolly, S.; Boson, B.; Vanhomwegen, J.; Gouilh, M.A.; et al. High prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in pets from COVID-19+ households. One Health 2020, 11, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhang, C.; Wheelock, Å.M.; Xin, S.; Cai, H.; Xu, L.; Wang, X.-J. Immunomics in one health: understanding the human, animal, and environmental aspects of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1450380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, N.; Rothman-Ostrow, P.; Osman, A.Y.; Arruda, L.B.; Macfarlane-Berry, L.; Elton, L.; Thomason, M.J.; Yeboah-Manu, D.; Ansumana, R.; Kapata, N.; et al. COVID-19—Zoonosis or Emerging Infectious Disease? Front. Public Heal. 2020, 8, 596944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happi, A.N.; Ayinla, A.O.; Ogunsanya, O.A.; Sijuwola, A.E.; Saibu, F.M.; Akano, K.; George, U.E.; Sopeju, A.E.; Rabinowitz, P.M.; Ojo, K.K.; et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Terrestrial Animals in Southern Nigeria: Potential Cases of Reverse Zoonosis. Viruses 2023, 15, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, E.C.; Reid, T.J. Animals and SARS-CoV-2: Species susceptibility and viral transmission in experimental and natural conditions, and the potential implications for community transmission. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 68, 1850–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, W.K.; De Oliveira-Filho, E.F.; Rasche, A.; Greenwood, A.D.; Osterrieder, K.; Drexler, J.F. Potential zoonotic sources of SARS-CoV-2 infections. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 13872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, O.O.; Dahunsi, S.O.; Okoh, A. SARS-CoV-2 infection of domestic animals and their role in evolution and emergence of variants of concern. New Microbes New Infect. 2024, 62, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, J.; Meli, M.L.; Willi, B.; Nadeau, S.; Beisel, C.; Stadler, T.; Team, E.S.-C.S.; Egberink, H.; Zhao, S.; Lutz, H.; et al. Detection and Genome Sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 in a Domestic Cat with Respiratory Signs in Switzerland. Viruses 2021, 13, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeppel, K.N.; Mendes, A.; Strydom, A.; Rotherham, L.; Mulumba, M.; Venter, M. SARS-CoV-2 Reverse Zoonoses to Pumas and Lions, South Africa. Viruses 2022, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maganga, G.D.; Ngoubangoye, B.; Koumba, J.P.; Lekana-Douki, S.; Kinga, I.C.M.; Tsoumbou, T.A.; Beyeme, A.M.M.; Mebaley, T.G.N.; Lekana-Douki, J.-B. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pets, captive non-human primates and farm animals in Central Africa. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2022, 15, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meekins, D.A.; Gaudreault, N.N.; Richt, J.A. Natural and Experimental SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Domestic and Wild Animals. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molini, U.; Coetzee, L.M.; Engelbrecht, T.; de Villiers, L.; de Villiers, M.; Mangone, I.; Curini, V.; Khaiseb, S.; Ancora, M.; Cammà, C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 in Namibian Dogs. Vaccines 2022, 10, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molini, U.; Coetzee, L.M.; Hemberger, M.Y.; Jago, M.; Khaiseb, S.; Shapwa, K.; Lorusso, A.; Cattoli, G.; Dundon, W.G.; Franzo, G. Bovine coronavirus presence in domestic bovine and antelopes sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from Namibia. BMC Veter- Res. 2025, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Smith, D.; Ghai, R.R.; Wallace, R.M.; Torchetti, M.K.; LoIacono, C.; Murrell, L.S.; Carpenter, A.; Moroff, S.; Rooney, J.A.; et al. First Reported Cases of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Companion Animals — New York, March–April 2020. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. (MMWR) 2020, 69, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreshkova, N.; Molenaar, R.J.; Vreman, S.; Harders, F.; Munnink, B.B.O.; Der Honing, R.W.H.-V.; Gerhards, N.; Tolsma, P.; Bouwstra, R.; Sikkema, R.S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in farmed minks, the Netherlands, April and May 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2001005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, S.D.C.; Jimenez, A.J.; Rangel, G.A.; Rengifo-Herrera, C.D.C. One Health serosurveillance of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in domestic animals from the metropolitan area of Panama. Veter- World 2025, 18, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, E.I.; Elia, G.; Grassi, A.; Giordano, A.; Desario, C.; Medardo, M.; Smith, S.L.; Anderson, E.R.; Prince, T.; Patterson, G.T.; et al. Evidence of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in cats and dogs from households in Italy. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, T.; Smith, S.L.; Radford, A.D.; Solomon, T.; Hughes, G.L.; Patterson, E.I. SARS-CoV-2 Infections in Animals: Reservoirs for Reverse Zoonosis and Models for Study. Viruses 2021, 13, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadikaliyeva, S.; Shorayeva, K.; Abay, Z.; Jekebekov, K.; Shayakhmetov, Y.; Kalimolda, E.; Omurtay, A.; Kopeyev, S.; Nakhanov, A.; Yespembetov, B.; et al. Detection of coronavirus among domestic animals. Research for Rural Development 2024: annual 30th international scientific conference; LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 62–66.

- Sailleau, C.; Dumarest, M.; Vanhomwegen, J.; Delaplace, M.; Caro, V.; Kwasiborski, A.; Hourdel, V.; Chevaillier, P.; Barbarino, A.; Comtet, L.; et al. First detection and genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 in an infected cat in France. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 2324–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, T.H.C.; Brackman, C.J.; Ip, S.M.; Tam, K.W.S.; Law, P.Y.T.; To, E.M.W.; Yu, V.Y.T.; Sims, L.D.; Tsang, D.N.C.; Chu, D.K.W.; et al. Infection of dogs with SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 586, 776–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegally, H.; Moir, M.; Everatt, J.; Giovanetti, M.; Scheepers, C.; Wilkinson, E.; Subramoney, K.; Makatini, Z.; Moyo, S.; Amoako, D.G.; et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron lineages BA.4 and BA.5 in South Africa. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1785–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temmam, S.; Barbarino, A.; Maso, D.; Behillil, S.; Enouf, V.; Huon, C.; Jaraud, A.; Chevallier, L.; Backovic, M.; Pérot, P.; et al. Absence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in cats and dogs in close contact with a cluster of COVID-19 patients in a veterinary campus. One Heal. 2020, 10, 100164–100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyanga, V.A.; Onagbesan, O.M.; Onwuka, C.F.I.; Emmanuel, B.; Lin, H. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Poultry Production: Emerging issues in African Countries. World's Poult. Sci. J. 2021, 77, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Disease Outbreak News; COVID-19 - Global situation. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON572.

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Study design | Studies focused on COVID-19 transmission | Studies not focused on COVID-19 transmission |

| Type of Study | Journal articles, grey literature, and situation reports on COVID-19 transmission | Conference proceedings, study protocols, Systematic reviews, editorials, or commentaries, and blogs on COVID-19 |

|

Setting |

Studies with topics reporting on COVID-19 transmission, and interventions conducted in Southern African countries: single- or multi-country studies | Studies with topics reporting on COVID-19 transmission and interventions conducted in non-Southern African countries. |

| Language | Studies written in English | Studies not written in English |

| Period (year) | Studies published from 2019 to 2024 | Studies published below 2019 |

| Author/Year | Methods Used | Country | Sample Size | Animal Studied |

| Molini et al., (2022) | PCR, serology | Namibia | 20 | Dogs |

| Molini et al., (2025) | PCR, sequencing | Namibia | 50+ | Cattle, Antelopes |

| Choga et al. (2023) | Genome sequencing | Botswana | 1 | Dog |

| Decaro et al. (2021) (Southern African cases cited) | Case studies | South Africa | Multiple | Dogs, Cats |

| Koeppel et al. (2022) | Molecular detection | South Africa | 2 | Zoo cats (pumas, lions) |

| Meekins et al. (2021) | Experimental infection | South Africa (collaborative) | Multiple | Cats, ferrets |

| Tegally et al. (2022) | Genomic surveillance | South Africa | Thousands | Human-animal interface |

| Maganga et al. (2022) | Field surveillance | Central Africa (includes Southern sites) | Multiple | Dogs, Cats, Goats |

| Uyanga et al. (2021) | Poultry production review | Southern Africa | Not specified | Chickens |

| Joseph et al. (2024) | Case reports | South Africa | Multiple | Dogs, Cats |

| Agusi et al. (2022) | African surveillance | Southern Africa subset | Multiple | Domestic animals |

| Local veterinary reports (2021–2023) | Case surveillance | South Africa | Dozens | Dogs, Cats |

| Author | Transmission Type | Most Susceptible Animal | Prognosis |

| Molini et al. (2022) | Human → Dog | Dogs | Mild/asymptomatic |

| Choga et al. (2023) | Human → Dog | Dog | Symptomatic, recovered |

| Decaro et al. (2021) | Human → Dogs/Cats | Cats | Mild |

| Koeppel et al. (2022) | Human → Zoo cats | Big cats | Mild/moderate |

| Meekins et al. (2021) | Experimental human → cats/ferrets | Cats | Susceptible, moderate illness |

| Tegally et al. (2022) | Human → Human (variant spillover risk) | Indirect interface | Omicron BA.4/BA.5 |

| Maganga et al. (2022) | Human → Pets/farm animals | Dogs, goats | Mild |

| Joseph et al. (2024) | Human → Domestic animals | Dogs, cats | Variant evolution risk |

| Agusi et al. (2022) | Human-animal interface | Multiple | Re-emergence potential |

| Country/Region | Interventions | Challenges |

| South Africa (Koeppel, Tegally, Decaro, Meekins) | Zoo surveillance, genomic monitoring, veterinary case reports | Resource constraints, variant evolution |

| Namibia (Molini et al., 2022) | Dog testing, serology | Limited infrastructure |

| Botswana (Choga et al., 2023) | Genome sequencing in dogs | Case-based, limited sequencing |

| Regional (Agusi et al., 2022; Joseph et al., 2024) | One Health surveillance, domestic animal monitoring | Underreporting, weak veterinary networks |

| Southern Africa poultry sector (Uyanga et al., 2021) | Monitoring poultry production | Minimal susceptibility, economic stress |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.