1. Introduction

Over the last 25 years, zoonotic transmission of newly emergent coronaviruses to humans has resulted in severe multi-continent epidemics of respiratory diseases, including the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) first detected in 2002 in China caused by SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) detected in 2012 in Saudi Arabia caused by MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and COVID-19 pandemic detected in 2019 in China caused by SARS-CoV-2 [

1,

2,

3] . Of these viruses, only MERS-CoV has a domestic animal reservoir; dromedary camels, which transmit the virus to humans in close contact through aerosol droplets [

4,

5].

There are three genetically distinct clades of MERS-CoV; A, B and C, with clades A and B continuing to spread through the Middle East, Asia, and other countries through primary camel contact and secondary human-human transmission fueled by close contact in intensive care units and travel, and resulting in 2613 confirmed human cases and a case fatality rate of 36% as at the last cases reported case in April, 2024 [

6,

7]. Over 80% of these cases were reported from Saudi Arabia, 55% infected through primary camel contact and the rest through secondary human-to-human transmission[

8]. Most (> 80%) clade A/B clinical cases occur in older persons (median age = 58 years), having at least one underlying medical condition such as chronic renal failure, heart failure, diabetes and or hypertension [

9] Clade A MERS-CoV caused the initial wave of cases but was quickly replaced by clade B as the primary circulating clade in the Middle East beyond the initial outbreak [

10,

11,

12].

Despite being home to >80% of the global dromedary camel population and being the source market for most camels sold in the Middle East, Africa has never reported human MERS-CoV outbreak associated with primary camel exposure[

13]. Most studies indicate that only clade C virus circulates in the continent, associated with documented outbreaks in camels and >70% seroprevalence in most camel populations but limited serologic evidence of human exposure or symptomatic infection has been reported in humans [

14,

15,

16] . The paucity of human cases in Africa may be explained by viral plasticity resulting in inefficient transmission and/or weakened virulence of clade C, as supported by

in vitro and

ex vivo studies[

17] . Alternatively, it may be due to poor disease surveillance and reporting among the marginalized nomadic pastoralist populations that inhabit remote arid lands where camels are reared[

18]. Here, we combined our intensive hospital- and community-based MERS-CoV studies in Northern Kenya with scoping review of studies across Africa to assess levels of camel-to-human virus transmission and morbidity in human.

2. Materials and Methods

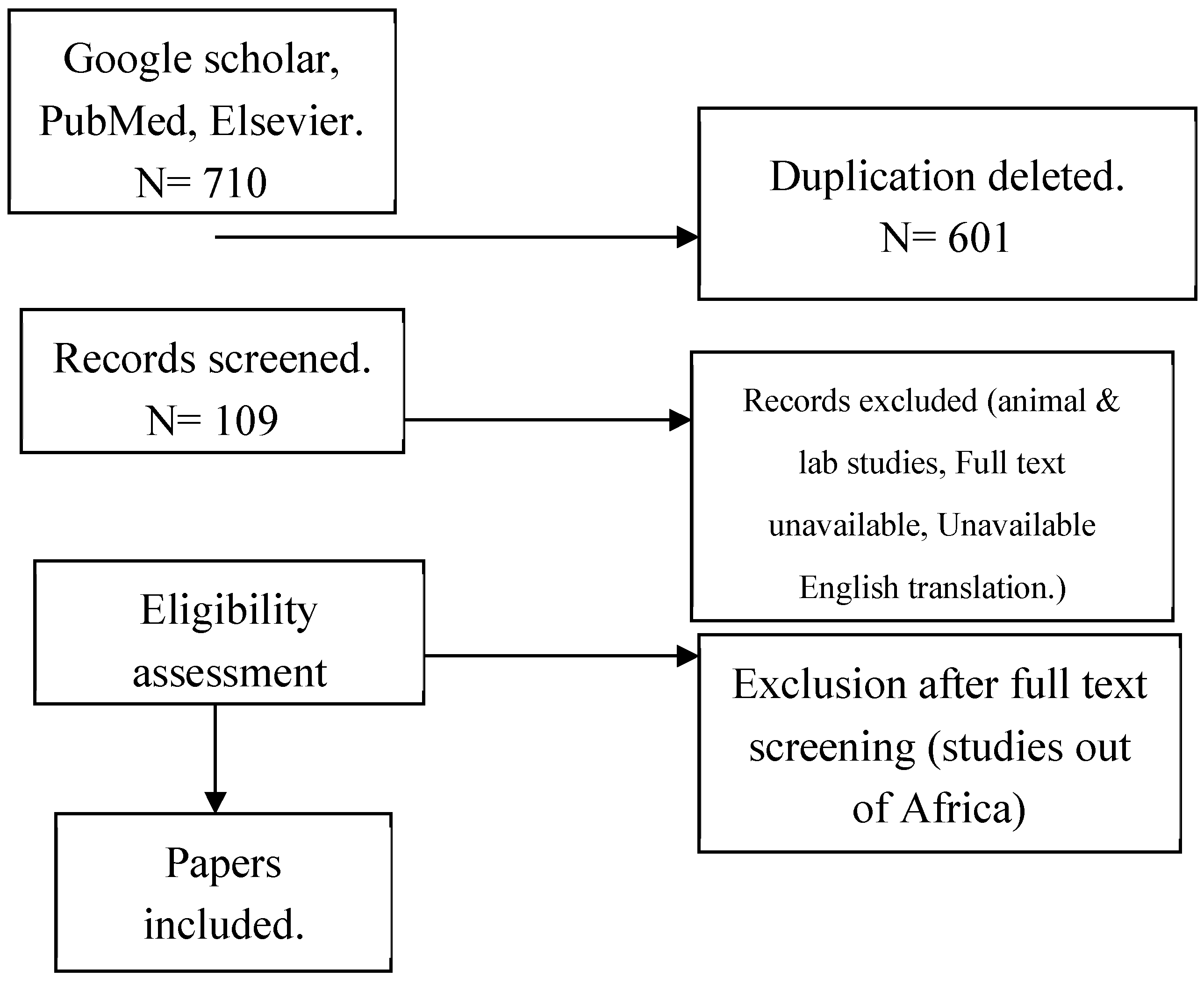

2.1. Scoping review

We conducted a scoping review to identify and evaluate reported human MERS-CoV across Africa using preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidance and register the protocol a

t Open science Framework. A comprehensive literature search at

PubMed,

Research4life,

Elsevier,

Google scholar, Cochrane, EMBASE, and

HINARI databases used to identify peer-reviewed publications on human MERS-CoV infections in Africa between January 2012―September 2024. Search terms were informed by key words using the Population, Intervention, Control group, Outcome (PICOs) guidance to ensure the broadest results (

Supplementary Table S1).

2.2. Selection of articles

Selected articles were independently screened by two researchers for inclusion and exclusion. Studies with human cases/human samples on MERS-CoV from African countries, epidemiological research, molecular epidemiology studies, cohort studies, case controls, cross sectional studies and mixed method studies, reviews (scoping, systematic), clinical research: clinical studies, diagnostic studies, prognostic studies, and case reports/series studies were all included in the scoping review. Basic MERS-CoV research studies, laboratory studies and cellular studies, biochemistry, genetics/genomics, commentaries, editorials, opinions pieces, perspectives, dissertation (unless published in a peer review), non-English translated studies and MERS-CoV studies conducted outside Africa within the same period were excluded. Data from selected articles were manually recorded in Microsoft excel using the following variables: Article identification: Source of article, Year of publication, Full title, Author, Reason for inclusion and Country of origin. Key outcomes of interest were prevalence, morbidity, and mortality. Other variables included type of sample, laboratory test used, occupation, median age, sex, study design, postulated origin/ source of infection, and viral mutation.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

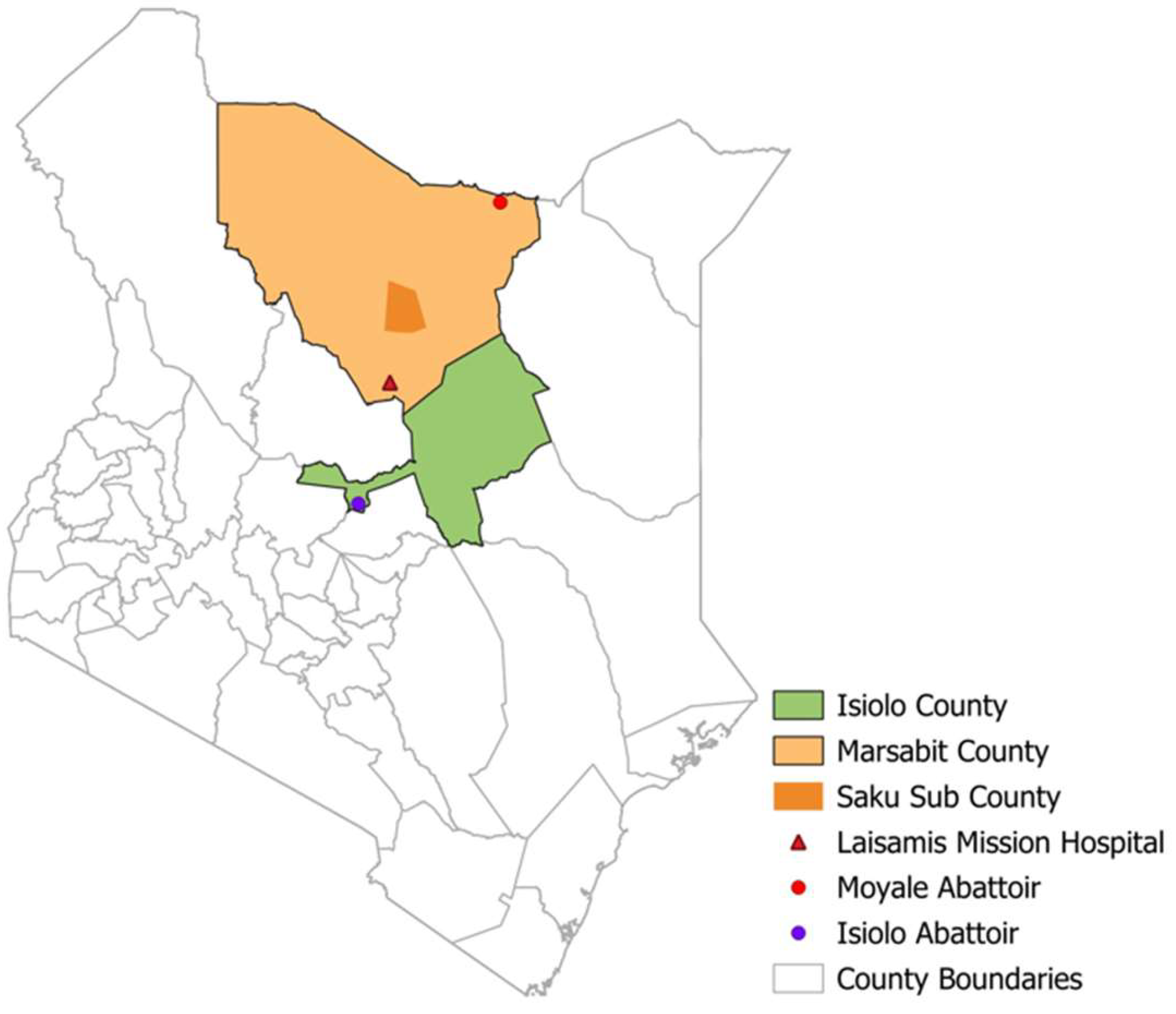

2.3. Empirical studies in Northern Kenya, 2018-2024

We analyzed data from four ongoing studies on human MERS-CoV among camel pastoralist communities in Isiolo and Marsabit counties in northern Kenya between 2018 and 2024 (

Figure 1). These included two community cohort studies enrolling 351 camel herders, a 2-year prospective slaughterhouse workers (n= 124) cohort, and two hospital cross-sectional surveillance studies enrolling patients presenting with flu-like symptoms at Marsabit County Referral Hospital (n=935) and Laisamis Catholic Mission Hospital (n=942). Structured questionnaires we used to collect data on risk factors, clinical symptoms, and comorbidities.

Figure 2.

Map of Kenya showing human MERS-CoV study sites.

Figure 2.

Map of Kenya showing human MERS-CoV study sites.

2.4. Sample collection and laboratory testing.

Upon consenting, participants provided nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal (NP/OP) swabs and serum samples. Serum was assessed for IgG antibodies against MERS-CoV using the Euroimmun anti-MERS-CoV enzyme linked immunosorbent assay test kit (EUROIMMUN Medizinische Labordiagnostika AG, Lubeck, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The kit semi quantitatively detected IgG antibodies against MERS-CoV in serum by binding antibodies to viral antigens in precoated wells, followed by a colorimetric reaction indicating antibody presence. Results were compared to controls, with a positive result suggesting prior exposure/infection. MERS-CoV ELISA positive samples underwent microneutralization assay [

19], where positive sera were diluted and mixed with live MERS-CoV or pseudo virus, then incubated to allow virus specific antibodies in the serum to bind. The mixture was then added to a culture of susceptible cells; if neutralizing antibodies were present, they blocked viral infection, indicating prior exposure to MERS-CoV.

To detect MERS-CoV RNA, NP/OP swabs were tested using RT-PCR as previously described[

14,

15].( Briefly, total nucleic acids were extracted from 200 µL of the sample, followed by a standard RT-PCR test targeting two pre-determined targets. A sample was considered positive if all PCR targets were positive (defined by a Cycle Threshold/CT value < 40).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using R (version 4.2.0) [

20]. Scoping review findings were summarized using frequencies and proportions, with continuous variables shown as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Key data included study location, sex, age groups, occupation, travel history, and camel contact. Categorical variables were summarized with frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables (e.g., age) used medians and IQR. Clinical and lab data were combined with demographic information and presented in tables. Pooled prevalence was used to estimate overall prevalence, weighted by sample size in the scooping review.

3. Results

3.1. Findings from scoping review

Of 109 articles reviewed, 16 articles[

13,

14,

15,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32] covering 7 African countries in east (Kenya, Sudan), north (Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco), and west (Ghana and Nigeria) Africa were included in the analysis (

Table 1). The studies covered the period between January 2012 to September 2024. A total of 87.5% (n=14) of the eligible studies enrolled both human and camel participants. Camel studies were only included in the review if the studies also reported on human testing. The 16 studies included 6,198 human participants (median = 262, IQR: 75, 554), most (62.5%) of whom were male with a median age of 42 (IQR:18, 65). Participant occupations included camel herding (38.0%), abattoir workers (31.0%), and camel farmers (19.0%). The eligible studies also reported the results of 7,194 camels, evaluated alongside the human participants. Study types included cross-section serosurveys (n=9), 5 longitudinal cohorts (n=5), case control (n=1), and case report (n=1). Most of the studies (62.4%) used a combination of ELISA and Microneutralization Assay (MNA) for serologic confirmation, while 24.0% attempted virus detection by using polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

3.2. Human prevalence, morbidity, and mortality

Of 6,198 participants, the median human MERS-CoV pooled prevalence was 2.4% (IQR:0.6, 11.4). Eighty one percent (81.0%) of the studies associated the source of human infections with dromedary camels, whereas 12.4% (n=3) attributed infections to travel from the middle east. A cohort study conducted in Kenya confirmed 3 acute but asymptomatic MERS-CoV cases by PCR cases [

14]. While majority (n=13) of the studies did not document any clinical symptoms on participants, three studies reported clinical symptoms including cough (18.8%), fever (12.5%), sore throat (12.5%), difficulty in breathing (6.3%) and running nose (6.3%). One mortality was reported from a case study in Tunisia of a 66-year-old diabetic male, who had travel back from Qatar and Saudi Arabia prior to onset of symptoms [

23].

3.3. Findings from empirical studies in Kenya, 2018-2024

Between 2018 and 2024, we conducted four different studies on MERS-CoV in the northern Kenya region: household-based camel-human cohort, longitudinal follow-up of camel slaughterhouse workers, and two hospital-based studies as shown in

Table 2. Some findings from one study ([

14,

15]) are included in the scoping review. We enrolled a total of 2,352 human participants, all associated with pastoral livelihood of inhabitants of this arid region, 54.1% of them male, and 34.3% below the age of 10 years. Observed underlying conditions like respiratory illnesses were reported by 78.0% of the participants, and visceral leishmaniasis (Kalazar), which is endemic in the region was reported by 1.7% of the participants (

Table 2).

Over half (50.4%) of the participants reported camel contact as per table 3. Below is a breakdown summary of some of the camel contacts recorded in our studies including consuming raw products, feeding/herding, milking, and cleaning of barns (

Table 3).

3.4. MERS-CoV prevalence, morbidity, and mortality in human participants

Of the 2352 participants followed in the four studies, 27 (pooled prevalence =1.14%) were positive for MERS-CoV by either PCR or serology (ELISA + MNA). In the community cohort study, 351 participants were follow-up and tested bimonthly for 1 year, while in the slaughterhouse study, 124 participants were follow-up and tested bimonthly for 2 years. These test results summarized in

Table 4, showing that of 4,222 samples tested by PCR, 3 (0.07%) were positive for viral RNA while 24 (0.6%) were positive for serology.

In the slaughterhouse study, 28.1 % of 124 participants developed clinical symptoms over the follow-up period, whereas in the community cohort study, 11.7% of 351 participants did. When we evaluated prevalence of respiratory symptoms across the four studies, cough (76.7%), running nose (45.6%) and chest pains (28.1%) were the most common (

Table 5). Cough had the longer duration (median:4 days), while other symptoms like sneezing and nasal discharge had shorter (median:2 - 3 days) durations. No mortality was reported among participants over the duration of the studies.

4. Discussion

This dual methods approach evaluated 8,550 human participants at risk of MERS-CoV infection due to either regular contact with camels or travel to the Middle east, and confirmed low prevalence and morbidity, and so far, no mortality associated with autochthonous MERS-CoV clade C transmission in Africa. The overall disease prevalence in the participants, most of whom had camel contact (50-80%) was 2.1%, all of it serologic evidence except three PCR confirmed cases. Clinical respiratory disease was reported in 28% of our study participants and 18.8% of participants in published studies[

22,

23,

33]. However, no clade C associated mortality was reported with the one fatal case reported in a 66-year-old diabetic male from Tunisia who had traveled to the Middle East, thus likely associated with clades A or B [

23].

Our prospective hospital and community-based studies incorporating 2352 human participants with high-risk occupations ruled out the possibility of weak surveillance system as the reason for paucity of human cases associated with clade C virus. In addition, the arid/semi-arid ecosystem of northern Kenya where we conducted our studies mirror that of the Middle east where clade A and B have caused more severe morbidity and mortality [

34]. Therefore, these findings point to a less transmissible and weakly virulent clade C virus as the likely reason for the low disease prevalence and morbidity. This possibility is supported by studies showing that clades A and B were associated with higher virus replication rate and more severe pathology in

ex-vivo human lung and bronchus tissues, and high replication

in vitro compared to clade C [

10,

35].

To continue interrogating these findings, our team is currently undertaking further functional genomic studies across the three MERS-CoV clades to elucidate possible mechanisms associated with differential virulence among them. In addition, being aware that severe disease associated with clades A and B in recent outbreaks in the Middle east was more frequent and severe among persons with underlying medical conditions [

9,

36], we will continue longitudinal community cohort studies with a broadened enrollment eligibility in Northern Kenya regions where we have identified transmission hotspots, to further investigate this.

There are several concerns arising from the finding that clade C is less transmissible and less virulent. First, it is evident that clade C virus will continue undergoing functional mutations that enhance its transmissibility and even virulence [

37], emphasizing the need for continuous genomic surveillance of the virus in African camels. Second, clade A or B may be introduced into the continent through human travel or camel sporting activities, resulting in one of these highly virulent strains establishing itself to begin causing severe human outbreaks with high morbidity and mortality [

38]. Lastly, the World Health Organization listing of MERS-CoV among viruses likely to cause pandemic and pushing the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) to pursue its vaccine development is commendable [

39,

40], and emphasizes the need for ongoing MERS-CoV genomic surveillance in Africa.

Some of the limitations of this analysis include the possibility that some infections that occurred between follow-up visits in the cohort studies were missed due to the irregular swabbing. Furthermore, not all household members were enrolled in the community studies, underscoring the challenges with virus detection in the longitudinal studies. Also, the empirical studies included in this analysis are from one region, however, this region also represents a critical node in the camel export route with three quarters of the camels exported to the Middle East origination along this path. Lastly, serologic assessment of antibodies and MERS-CoV T-cell responses might have detected mild and asymptomatic MERS-CoV cases as has been shown in other studies that have shown a lower yield with MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 serologic testing[

41,

42], probably because of stringent cut-offs established for infection despite evidence pointing out that clade C infections are mostly subclinical [

43]. Despite this limitation, this analysis represents one of the large analyses that have been undertaken to interrogate clade C MERS-CoV infection in Africa and forms a basis for future considerations for MERS-CoV surveillance in Africa.

5. Conclusions

Our study confirms that currently circulating clade C MERS-CoV strains have limited public health threat, associated with low prevalence and morbidity, and so far, no mortality. However, given the high circulation in dromedary camels, there is need for continued surveillance including genomic surveillance in this region to understand the public health threat of clade C MERS-CoV.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Table S1: PICOS framework used to identify human MERS-CoV studies in Africa.

Author Contributions

A.K., C.O., I.N., M.K.N.; conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing original draft and writing-review and editing; S.S., I.N., M.M., W.J., R.B., M.K.N.; supervision, writing-review, and editing. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge the collaborative support from the Ministries of Health and county governments of Isiolo and Marsabit. Funding for the project was provided by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/National Institutes of Health (NIAID/NIH), grants number U01AI151799 through the Centre for Research in Emerging Infectious Diseases-East and Central Africa (CREID-ECA). We acknowledge Andrew Karani’s training support from the NIH/Fogarty International Center’s D43 training grant # D43TW011519 to Washington State University and University of Nairobi (UON).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The 2018 – 2021 community and hospital studies received approvals from the WSU Institutional Review Board (WSU-IRB/16245-006), KEMRI Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (KEMRI/SERU/CGHR/3472), CDC (#7069), and WSU Institutional Biosafety Committee (#1286-001/002). The 2022 – 2024 slaughterhouse cohort and hospital surveillance studies were approved by Kenya’s NACOSTI[NACOSTI/P/23/27617]. and the Kenyatta National Hospital – University of Nairobi Ethics Committee (P157/02/2022). Local approvals were granted by Isiolo and Marsabit county health departments. All participants provided written consent before enrollment.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the studies.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data used to support the findings of this study can be provided by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Judson SD, Rabinowitz PM. Zoonoses and global epidemics. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2021 Oct;34(5):385–92.

- Alsafi RT. Lessons from SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2 Infections: What We Know So Far. Tharmalingam J, editor. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. 2022 Aug 12;2022:1–13.

- Giovanetti M, Branda F, Cella E, Scarpa F, Bazzani L, Ciccozzi A, et al. Epidemic history and evolution of an emerging threat of international concern, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Journal of Medical Virology. 2023 Aug;95(8):e29012. [CrossRef]

- Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Drivers of MERS-CoV transmission: what do we know? Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 2016 Mar 3;10(3):331–8.

- Rui J, Wang Q, Lv J, Zhao B, Hu Q, Du H, et al. The transmission dynamics of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2022 Jan;45:102243. [CrossRef]

- Kossyvakis A, Tao Y, Lu X, Pogka V, Tsiodras S, Emmanouil M, et al. Laboratory Investigation and Phylogenetic Analysis of an Imported Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Case in Greece. Vasilakis N, editor. PLoS ONE. 2015 Apr 28;10(4):e0125809.

- Zhou Z, Hui KPY, So RTY, Lv H, Perera RAPM, Chu DKW, et al. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of MERS coronaviruses from Africa to understand their zoonotic potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021 Jun 22;118(25):e2103984118. [CrossRef]

- MERS situation update - May 2024.

- Matsuyama R, Nishiura H, Kutsuna S, Hayakawa K, Ohmagari N. Clinical determinants of the severity of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2016 Dec;16(1):1203. [CrossRef]

- Te N, Rodon J, Pérez M, Segalés J, Vergara-Alert J, Bensaid A. Enhanced replication fitness of MERS-CoV clade B over clade A strains in camelids explains the dominance of clade B strains in the Arabian Peninsula. Emerging Microbes & Infections. 2022 Dec 31;11(1):260–74.

- Zhang AR, Shi WQ, Liu K, Li XL, Liu MJ, Zhang WH, et al. Epidemiology and evolution of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, 2012–2020. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021 Dec;10(1):66. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Sun J, Li X, Zhu A, Guan W, Sun DQ, et al. Increased Pathogenicity and Virulence of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Clade B In Vitro and In Vivo. Gallagher T, editor. J Virol. 2020 Jul 16;94(15):e00861-20. [CrossRef]

- Eckstein S, Ehmann R, Gritli A, Ben Yahia H, Diehl M, Wölfel R, et al. Prevalence of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus in Dromedary Camels, Tunisia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Jul;27(7):1964–8. [CrossRef]

- Ngere I, Hunsperger EA, Tong S, Oyugi J, Jaoko W, Harcourt JL, et al. Outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus in Camels and Probable Spillover Infection to Humans in Kenya. Viruses. 2022 Aug 9;14(8):1743. [CrossRef]

- Munyua PM, Ngere I, Hunsperger E, Kochi A, Amoth P, Mwasi L, et al. Low-Level Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus among Camel Handlers, Kenya, 2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(4):1201–5. [CrossRef]

- Kiyong’a A, Cook E, Okba N, Kivali V, Reusken C, Haagmans B, et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Seropositive Camel Handlers in Kenya. Viruses. 2020 Apr 3;12(4):396.

- Sugimoto S, Kakizaki M, Kawase M, Kawachi K, Ujike M, Kamitani W, et al. Single Amino Acid Substitution in the Receptor Binding Domain of Spike Protein Is Sufficient To Convert the Neutralization Profile between Ethiopian and Middle Eastern Isolates of Middle East Respiratory Coronavirus. Wang W, editor. Microbiol Spectr. 2023 Apr 13;11(2):e04590-22. [CrossRef]

- Hassell JM, Zimmerman D, Fèvre EM, Zinsstag J, Bukachi S, Barry M, et al. Africa’s Nomadic Pastoralists and Their Animals Are an Invisible Frontier in Pandemic Surveillance. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2020 Nov 4;103(5):1777–9. [CrossRef]

- Abbad A, Perera RA, Anga L, Faouzi A, Minh NNT, Malik SMMR, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) neutralising antibodies in a high-risk human population, Morocco, November 2017 to January 2018. Eurosurveillance [Internet]. 2019 Nov 28 [cited 2023 Jun 6];24(48). Available from: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.48.1900244. [CrossRef]

- Savita, Verma N. A REVIEW STUDY ON BIG DATA ANALYSIS USING R STUDIO. Int J Eng Tech Mgmt Res. 2020 Mar 27;6(6):129–36. [CrossRef]

- Lattwein E, Corman VM, Widdowson MA, Njenga MK, Murithi R, Osoro E, et al. No Serologic Evidence of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection Among Camel Farmers Exposed to Highly Seropositive Camel Herds: A Household Linked Study, Kenya, 2013. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2017 Jun 7;96(6):1318–24. [CrossRef]

- Sayed AS, Malek SS, Abushahba MF. Seroprevalence of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Corona Virus in dromedaries and their traders in upper Egypt. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2020 Feb 29;14(02):191–8. [CrossRef]

- Abroug F, Slim A, Ouanes-Besbes L, Kacem MAH, Dachraoui F, Ouanes I, et al. Family Cluster of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infections, Tunisia, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014 Sep;20(9):1527–30. [CrossRef]

- Annan A, Owusu M, Marfo KS, Larbi R, Sarpong FN, Adu-Sarkodie Y, et al. High prevalence of common respiratory viruses and no evidence of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus in Hajj pilgrims returning to Ghana, 2013. Trop Med Int Health. 2015 Jun;20(6):807–12. [CrossRef]

- Farag E, Sikkema RS, Mohamedani AA, De Bruin E, Munnink BBO, Chandler F, et al. MERS-CoV in Camels but Not Camel Handlers, Sudan, 2015 and 2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019 Dec;25(12):2333–5.

- Kiyong’a A, Cook E, Okba N, Kivali V, Reusken C, Haagmans B, et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) Seropositive Camel Handlers in Kenya. Viruses. 2020 Apr 3;12(4):396.

- Ommeh S, Zhang W, Zohaib A, Chen J, Zhang H, Hu B, et al. Genetic Evidence of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-Cov) and Widespread Seroprevalence among Camels in Kenya. Virol Sin. 2018 Dec;33(6):484–92.

- Abbad A, Perera RA, Anga L, Faouzi A, Minh NNT, Malik SMMR, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) neutralising antibodies in a high-risk human population, Morocco, November 2017 to January 2018. Eurosurveillance [Internet]. 2019 Nov 28 [cited 2022 Feb 9];24(48). Available from: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.48.1900244. [CrossRef]

- Owusu M, Annan A, Corman VM, Larbi R, Anti P, Drexler JF, et al. Human Coronaviruses Associated with Upper Respiratory Tract Infections in Three Rural Areas of Ghana. Pyrc K, editor. PLoS ONE. 2014 Jul 31;9(7):e99782. [CrossRef]

- So RT, Perera RA, Oladipo JO, Chu DK, Kuranga SA, Chan K ho, et al. Lack of serological evidence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in virus exposed camel abattoir workers in Nigeria, 2016. Eurosurveillance [Internet]. 2018 Aug 9 [cited 2023 Jun 6];23(32). Available from: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.32.1800175. [CrossRef]

- Liljander A, Meyer B, Jores J, Müller MA, Lattwein E, Njeru I, et al. MERS-CoV Antibodies in Humans, Africa, 2013–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Jun;22(6):1086–9.

- Mok CKP, Zhu A, Zhao J, Lau EHY, Wang J, Chen Z, et al. T-cell responses to MERS coronavirus infection in people with occupational exposure to dromedary camels in Nigeria: an observational cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2021 Mar;21(3):385–95. [CrossRef]

- Annan A, Owusu M, Marfo KS, Larbi R, Sarpong FN, Adu-Sarkodie Y, et al. High prevalence of common respiratory viruses and no evidence of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus in Hajj pilgrims returning to Ghana, 2013. Trop Med Int Health. 2015 Jun;20(6):807–12. [CrossRef]

- Francis D, Fonseca R. Recent and projected changes in climate patterns in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Sci Rep. 2024 May 4;14(1):10279. [CrossRef]

- Wong LYR, Zheng J, Sariol A, Lowery S, Meyerholz DK, Gallagher T, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus Spike protein variants exhibit geographic differences in virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021 Jun 15;118(24):e2102983118. [CrossRef]

- Feikin DR, Alraddadi B, Qutub M, Shabouni O, Curns A, Oboho IK, et al. Association of Higher MERS-CoV Virus Load with Severe Disease and Death, Saudi Arabia, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2015 Nov [cited 2024 Nov 14];21(11). Available from: http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/21/11/15-0764_article.htm.

- AlBalwi MA, Khan A, AlDrees M, Gk U, Manie B, Arabi Y, et al. Evolving sequence mutations in the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2020 Oct;13(10):1544–50.

- Watson JT, Hall AJ, Erdman DD, Swerdlow DL, Gerber SI. Unraveling the Mysteries of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014 Jun;20(6):1054–6. [CrossRef]

- Samarasekera U. CEPI prepares for future pandemics and epidemics.

- Tambo E, Oljira T. Averting MERS-Cov Emerging Threat and Epidemics: The Importance of Community Alertness and Preparedness Policies and Programs. J Prev Infect Control [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2024 May 23];1(1). Available from: http://infectioncontrol.imedpub.com/averting-merscov-emerging-threat-and-epidemics-the-importance-of-community-alertness-and-preparedness-policies-and-programs.php?aid=7084.

- Reynolds CJ, Swadling L, Gibbons JM, Pade C, Jensen MP, Diniz MO, et al. Discordant neutralizing antibody and T cell responses in asymptomatic and mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci Immunol. 2020 Dec 18;5(54):eabf3698.

- Yang J, Zhang E, Zhong M, Yang Q, Hong K, Shu T, et al. Longitudinal Characteristics of T Cell Responses in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Virol Sin. 2020 Dec;35(6):838–41.

- Mok CKP, Zhu A, Zhao J, Lau EHY, Wang J, Chen Z, et al. T-cell responses to MERS coronavirus infection in people with occupational exposure to dromedary camels in Nigeria: an observational cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2021 Mar;21(3):385–95. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of publications included in the scoping review.

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of publications included in the scoping review.

| Country/Region of origin |

No. Articles |

East Africa (Kenya & Sudan) |

West Africa (Ghana & Nigeria) |

North Africa (Morocco, Tunisia & Egypt) |

| No. articles |

16 |

7 |

4 |

5 |

| Sample size N (Median, IQR) |

262 (75, 554) |

261 (178,623) |

575 (254,932) |

28 (24,179) |

| Pooled MERS-CoV Prevalence (Median, IQR) |

2.4 (0.6, 11.4) |

1.4 (1.1,2.25) |

12 (6,21) |

8.6 (0,20) |

| Postulated origin of human infection |

|

|

|

|

| Camel |

13 (81.0%) |

1 |

2 |

4 |

| Environment |

1 (6.2%) |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| Travel |

2 (12.4%) |

0 |

1 |

1 |

| Human Morbidity |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

1 (6.2%) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| No |

13 (81.0%) |

7 |

3 |

3 |

| Human Mortality |

1 (6.2%) |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| Laboratory tests |

|

|

|

|

| ELISA & Neutralization |

10 (62.5%) |

5 |

1 |

4 |

| PCR |

5 (31.3%) |

2 |

2 |

1 |

| T cells |

1 (6.2%) |

0 |

1 |

0 |

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic characteristics and past medical history of participants enrolled in the four studies in Northern Kenya, 2018-2024.

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic characteristics and past medical history of participants enrolled in the four studies in Northern Kenya, 2018-2024.

| Study Type |

community cohort study 2018 -2021 |

Hospital study 2019 - 2021 |

Slaughterhouse study 2022 -2024 |

Hospital study 2022 - 2024 |

All studies |

| |

(n = 351) |

(n=935) |

(n= 124) |

(n= 942) |

(n= 2352) |

| Variable |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Female |

139 |

39.6 |

382 |

40.9 |

26 |

21 |

532 |

56.5 |

1079 |

45.9 |

| Male |

212 |

60.4 |

553 |

59.1 |

98 |

79 |

410 |

43.5 |

1273 |

54.1 |

| Age group (years) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| <10 |

85 |

24.2 |

409 |

43.7 |

- |

- |

312 |

33.1 |

806 |

34.3 |

| 11―24 |

125 |

35.6 |

213 |

22.8 |

34 |

27.4 |

225 |

23.9 |

597 |

25.4 |

| 24―49 |

106 |

30.2 |

190 |

20.3 |

74 |

59.7 |

270 |

28.7 |

640 |

27.2 |

| >50 |

35 |

10 |

123 |

13.2 |

16 |

12.9 |

105 |

11.1 |

279 |

11.9 |

| Occupation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Student/child |

144 |

41 |

466 |

49.8 |

- |

- |

4 |

0.4 |

614 |

26.1 |

| Livestock related |

148 |

42.2 |

469 |

50.2 |

124 |

100 |

1 |

0.1 |

742 |

31.5 |

| Non-livestock related |

59 |

16.8 |

3 |

0.3 |

- |

- |

3 |

0.3 |

65 |

2.8 |

| Underlying conditions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Respiratory illness |

25 |

7.1 |

838 |

89.6 |

31 |

25 |

941 |

99.9 |

1835 |

78 |

| Kalazar* |

- |

- |

16 |

1.7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

16 |

0.7 |

| Other comorbidities |

10 |

0 |

33 |

3.5 |

0 |

0 |

63 |

6.7 |

106 |

4.5 |

| Camel contact |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

249 |

70.9 |

297 |

31.8 |

121 |

97.6 |

509 |

54.0 |

1176 |

50.4 |

| Other comorbidities: Hypertension, diabetes, Liver disease, kidney disease. *Kalazar is endemic |

Table 3.

Camel contact among enrolled participants in studies in Northern Kenya, 2020-2024.

Table 3.

Camel contact among enrolled participants in studies in Northern Kenya, 2020-2024.

| Characteristic |

Community cohort study |

Hospital study 2019-2021 |

Slaughterhouse study |

Hospital study 2022―2023 |

All Studies |

| |

(n=351) |

(n=935) |

(n=124) |

(n=942) |

(n=2,352) |

| |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Type of camel contact |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Consuming raw products |

- |

- |

261 |

27.8 |

- |

- |

480 |

51 |

741 |

31.5 |

| Feeding/herding |

245 |

69.8 |

102 |

10.9 |

2 |

1.6 |

128 |

13.6 |

477 |

20.3 |

| Milking |

203 |

57.8 |

94 |

10.1 |

- |

- |

67 |

7.1 |

364 |

15.5 |

| Cleaning barns |

224 |

63.8 |

75 |

8 |

25 |

20.2 |

38 |

4 |

362 |

15.4 |

| Handling meat/hides/skin/offal’s |

- |

- |

130 |

13.9 |

97 |

78.2 |

85 |

9 |

312 |

13.3 |

| Treatment/restraining |

97 |

- |

43 |

4.6 |

20 |

16.1 |

37 |

3.9 |

197 |

8.4 |

| Sports/leisure/grooming |

31 |

8.8 |

70 |

7.5 |

70 |

- |

- |

4.2 |

141 |

6 |

| Slaughter |

32 |

9.1 |

14 |

1.5 |

14 |

11.3 |

18 |

1.9 |

78 |

3.3 |

| Assisting mating /birthing |

- |

- |

16 |

1.7 |

- |

- |

25 |

2.7 |

41 |

1.7 |

| Transport |

- |

- |

- |

- |

8 |

6.5 |

- |

- |

8 |

0.3 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4.

ELISA and PCRresults of human MERS studies in kenya 2018 – 2024.

Table 4.

ELISA and PCRresults of human MERS studies in kenya 2018 – 2024.

| |

Nasal/oral pharyngeal results (RT-PCR) |

Serum results (ELISA+MNA) |

| |

|

Negative= 4,219 |

Positive= 3 |

N= 728 |

Negative= 704 |

Positive= 24 |

| Study type |

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

N |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Community cohort study |

|

1,714 |

99.8 |

3 |

0.2 |

430 |

414 |

96.3 |

16 |

3.7 |

| Hospital study 2019 -2021 |

|

320 |

100.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.0 |

| Slaughterhouse cohort study |

|

1,243 |

100.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.0 |

| Hospital study 2022 - 2024 |

|

942 |

100.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

298 |

290 |

97.3 |

8 |

2.7 |

Table 5.

Clinical presentation between the community cohort and Hospital surveillance studies.

Table 5.

Clinical presentation between the community cohort and Hospital surveillance studies.

| |

Community cohort study |

Hospital study 2019 -2022 |

Slaughterhouse study |

Hospital study 2022―2023 |

All Studies |

|

| Symptoms |

(n=351) |

(n=935) |

(n=124) |

(n=942) |

(n=2352) |

Duration of symptom in days |

|

| |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

Median [Min, Max] |

|

| Cough |

10 |

2.8 |

835 |

89.3 |

22 |

17.7 |

938 |

99.6 |

1805 |

76.7 |

4.00 [0.00, 20.0] |

|

| Fever |

- |

- |

22 |

2.4 |

2 |

1.6 |

687 |

72.9 |

711 |

30.2 |

3.00 [1.00, 14.0] |

|

| Difficulty in breathing |

- |

- |

204 |

21.8 |

- |

- |

189 |

20.1 |

393 |

16.7 |

3.00 [1.00, 14.0] |

|

| Nasal congestion/stuffiness |

8 |

2.3 |

12 |

1.3 |

- |

- |

665 |

70.6 |

685 |

29.1 |

0.00 [0.00, 14.0] |

|

| Runny nose |

20 |

5.7 |

299 |

32.0 |

4 |

3.2 |

749 |

79.5 |

1072 |

45.6 |

3.00 [1.00, 14.0] |

|

| Sore throat |

2 |

0.6 |

20 |

2.1 |

4 |

3.2 |

331 |

35.1 |

357 |

15.2 |

3.00 [1.00, 14.0] |

|

| Chest pain |

1 |

0.3 |

282 |

30.2 |

1 |

0.8 |

378 |

40.1 |

662 |

28.1 |

5.00 [1.00, 20.0] |

|

| Headache |

- |

- |

272 |

29.1 |

2 |

1.6 |

556 |

59.0 |

830 |

35.3 |

3.00 [1.00, 14.0] |

|

| Fatigue |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

426 |

45.2 |

426 |

18.1 |

3.00 [1.00, 14.0] |

|

| Nausea |

- |

- |

12 |

1.3 |

- |

- |

202 |

21.4 |

214 |

9.1 |

2.00 [1.00, 14.0] |

|

| Sneezing |

- |

- |

3 |

0.3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

0.1 |

4.00 [2.00, 4.00] |

|

| Nasal discharge |

- |

- |

- |

106 |

11.3 |

- |

- |

- |

106 |

11.3 |

4.5 [3.00, 4.00] |

|

| Shortness of breath |

- |

- |

104 |

11.4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

104 |

4.4 |

3.00 [1.00, 14.0] |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).