Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source of Virus Genomes and Sequence Treatment

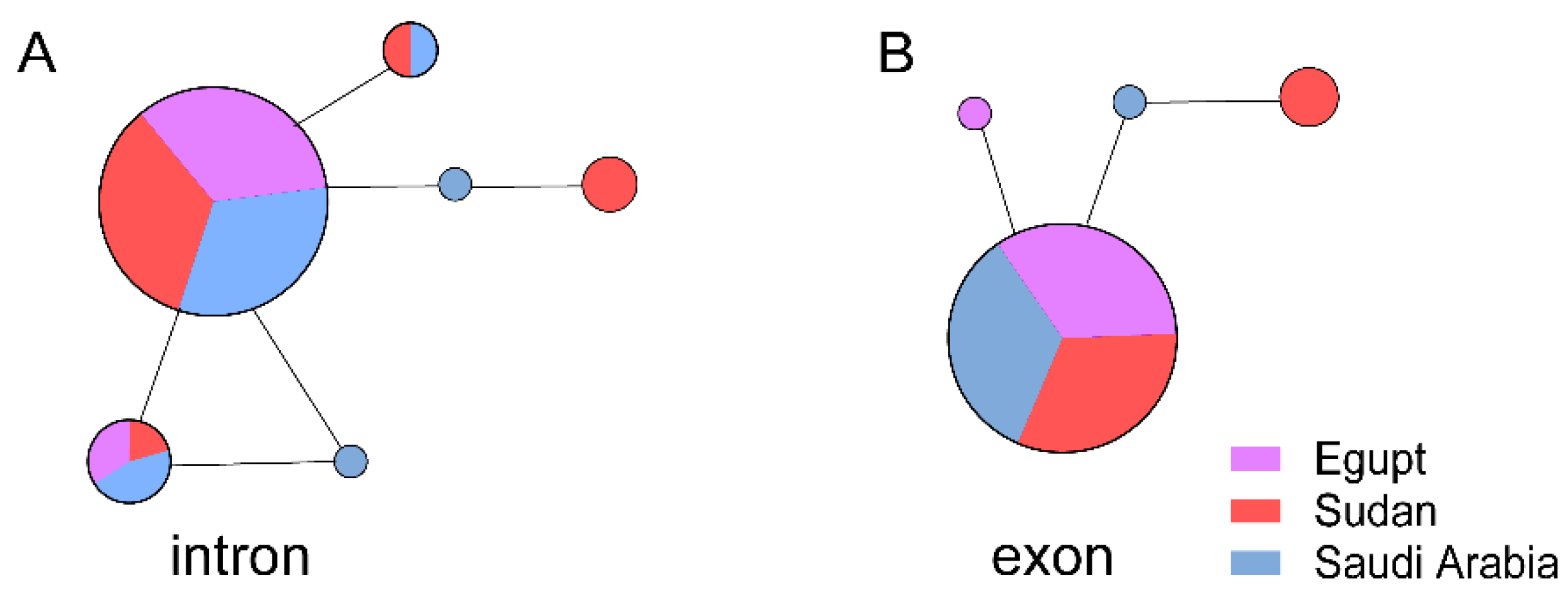

2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR, and Sequencing DPP4 Gene

3. Results

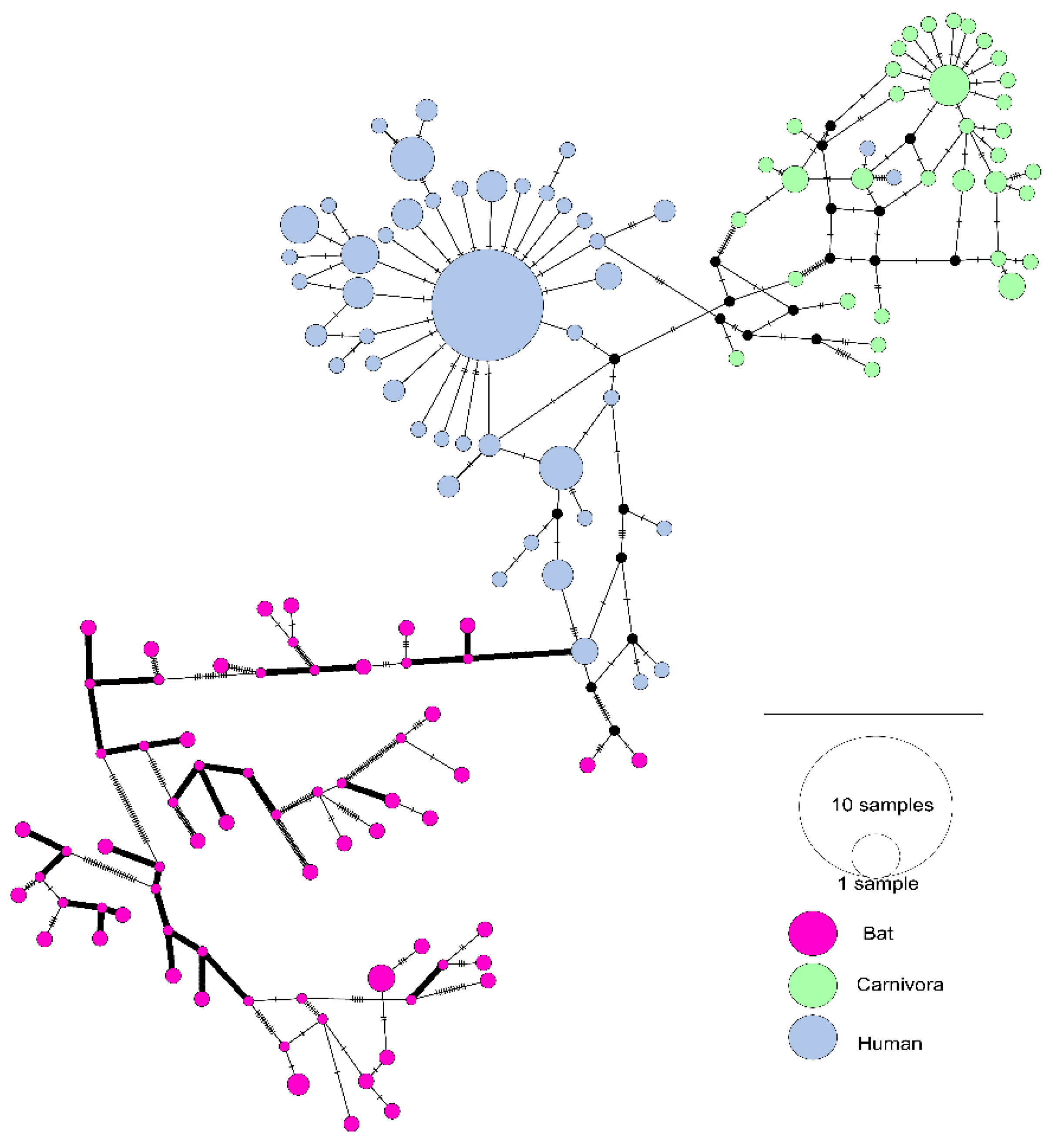

3.1. The Evolutionary Characteristics of SARS-CoVs

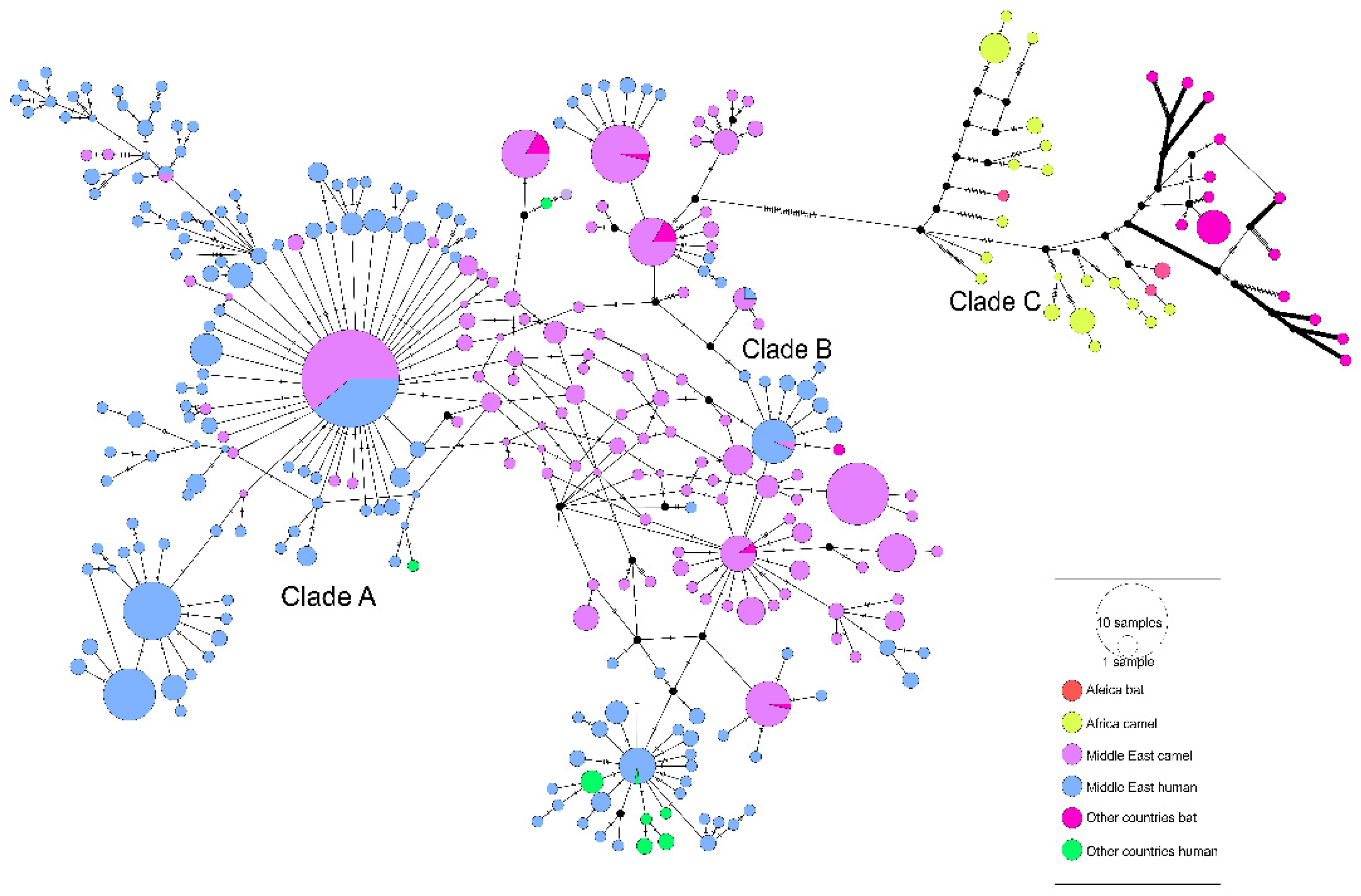

3.2. The Evolutionary Characteristics of MERS-CoV

3.3. The Evolutionary Characteristics of MERS-CoV

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cui, J.; Li, F.; Shi, Z.-L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Xu, Y.; Bao, L.; Zhang, L.; Yu, P.; Qu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, W.; Han, Y.; Qin, C. From SARS to MERS, Thrusting Coronaviruses into the Spotlight. Viruses 2019, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, A.R.; Perlman, S. Coronaviruses: An overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1282, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Drosten, C.; Günther, S.; Preiser, W.; Van Der Werf, S.; Brodt, H.-R.; Becker, S.; Rabenau, H.; Panning, M.; Kolesnikova, L.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; et al. Identification of a Novel Coronavirus in Patients with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, A.M.; Van Boheemen, S.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Isolation of a Novel Coronavirus from a Man with Pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Fan, H.; Lan, T.; Yáng, X.-L.; Shi, W.-F.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Xie, Q.-M.; Mani, S.; et al. Fatal swine acute diarrhoea syndrome caused by an HKU2-related coronavirus of bat origin. Nature 2018, 556, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, L. , et al., A new bat-HKU2-like coronavirus in swine, China, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis, 2017. 23(9).

- Wang, C.; Horby, P.W.; Hayden, F.G.; Gao, G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020, 395, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shi, Z.; Yu, M.; Ren, W.; Smith, C.; Epstein, J.H.; Wang, H.; Crameri, G.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Bats Are Natural Reservoirs of SARS-Like Coronaviruses. Science 2005, 310, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.J.; Zheng, B.J.; He, Y.Q.; Liu, X.L.; Zhuang, Z.X.; Cheung, C.L.; Luo, S.W.; Li, P.H.; Zhang, L.J.; Butt, K.M.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Viruses Related to the SARS Coronavirus from Animals in Southern China. Science 2003, 302, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.-D.; Tu, C.-C.; Zhang, G.-W.; Wang, S.-Y.; Zheng, K.; Lei, L.-C.; Chen, Q.-X.; Gao, Y.-W.; Zhou, H.-Q.; Xiang, H.; et al. Cross-host evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in palm civet and human. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 2430–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, E. , et al., SARS and MERS: recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat Rev Micro, 2016. 14(8): p. 523-34.

- Sabir, J.S.M.; Lam, T.T.-Y.; Ahmed, M.M.M.; Li, L.; Shen, Y.; Abo-Aba, S.E.M.; Qureshi, M.I.; Abu-Zeid, M.; Zhang, Y.; Khiyami, M.A.; et al. Co-circulation of three camel coronavirus species and recombination of MERS-CoVs in Saudi Arabia. Science 2015, 351, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, S.J.; Gilardi, K.; Menachery, V.D.; Goldstein, T.; Ssebide, B.; Mbabazi, R.; Navarrete-Macias, I.; Liang, E.; Wells, H.; Hicks, A.; et al. Further Evidence for Bats as the Evolutionary Source of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. mBio 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehr, A.R.; Channappanavar, R.; Perlman, S. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome: Emergence of a Pathogenic Human Coronavirus. Annu. Rev. Med. 2017, 68, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millet, J.K.; A Jaimes, J.; Whittaker, G.R. Molecular diversity of coronavirus host cell entry receptors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolentino, J.E.; Lytras, S.; Ito, J.; Holmes, E.C.; Sato, K. Recombination as an evolutionary driver of MERS-related coronavirus emergence. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e546–e546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shen, L.; Gu, X. Evolutionary Dynamics of MERS-CoV: Potential Recombination, Positive Selection and Transmission. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25049–25049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolentino, J.E.; Lytras, S.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Recombination analysis on the receptor switching event of MERS-CoV and its close relatives: implications for the emergence of MERS-CoV. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.-B.; Liu, C.; Park, Y.-J.; Tang, J.; Chen, J.; Xiong, Q.; Lee, J.; Stewart, C.; Asarnow, D.; Brown, J.; et al. Multiple independent acquisitions of ACE2 usage in MERS-related coronaviruses. Cell 2025, 188, 1693–1710.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wu, F. Global surveillance and countermeasures for ACE2-using MERS-related coronaviruses with spillover risk. Cell 2025, 188, 1465–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeri, N.C. , et al., The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: what lessons have we learned? Int J Epidemiol, 2020. 49(3): p. 717-726.

- Rabaan, A.A. , et al., MERS-CoV: epidemiology, molecular dynamics, therapeutics, and future challenges. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob, 2021. 20(1): p. 8.

- Raj, V.S.; Mou, H.; Smits, S.L.; Dekkers, D.H.; Müller, M.A.; Dijkman, R.; Muth, D.; Demmers, J.A.; Zaki, A.; Fouchier, R.A.; et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature 2013, 495, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Toh, H. Parallelization of the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 1899–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Peterson, D.; Peterson, N.; Stecher, G.; Nei, M.; Kumar, S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance, and Maximum Parsimony Methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 28, 2731–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, D.P.; Murrell, B.; Golden, M.; Khoosal, A.; Muhire, B. RDP4: Detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 2015, 1, vev003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. PAML 4: Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007, 24, 1586–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wong, W.S.; Nielsen, R. Bayes Empirical Bayes Inference of Amino Acid Sites Under Positive Selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005, 22, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosakovsky Pond, S.L.; Frost, S.D.W. Not So Different After All: A Comparison of Methods for Detecting Amino Acid Sites Under Selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005, 22, 1208–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrell, B.; Moola, S.; Mabona, A.; Weighill, T.; Sheward, D.; Pond, S.L.K.; Scheffler, K. FUBAR: A Fast, Unconstrained Bayesian AppRoximation for Inferring Selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrell, B.; Wertheim, J.O.; Moola, S.; Weighill, T.; Scheffler, K.; Pond, S.L.K.; Malik, H.S. Detecting Individual Sites Subject to Episodic Diversifying Selection. PLOS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D. Popart: Full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.C.P.; Li, X.; Lau, S.K.P.; Woo, P.C.Y. Global Epidemiology of Bat Coronaviruses. Viruses 2019, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-F.; Anderson, D.E. Viruses in bats and potential spillover to animals and humans. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2019, 34, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.-Y.; Li, J.-L.; Yang, X.-L.; Chmura, A.A.; Zhu, G.; Epstein, J.H.; Mazet, J.K.; Hu, B.; Zhang, W.; Peng, C.; et al. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2013, 503, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhao, K.; Shi, Z.-L.; Zhou, P. Bat Coronaviruses in China. Viruses 2019, 11, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagaili, A.N. , et al., Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in dromedary camels in Saudi Arabia. MBio, 2014. 5(2): p. e00884-14.

- Corman, V.M. , et al., Antibodies against MERS coronavirus in dromedary camels, Kenya, 1992-2013. Emerg Infect Dis, 2014. 20(8): p. 1319-22.

- Azhar, E.I.; El-Kafrawy, S.A.; Farraj, S.A.; Hassan, A.M.; Al-Saeed, M.S.; Hashem, A.M.; Madani, T.A. Evidence for Camel-to-Human Transmission of MERS Coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 2499–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudas, G.; Carvalho, L.M.; Rambaut, A.; Bedford, T. MERS-CoV spillover at the camel-human interface. eLife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandeil, A.; Gomaa, M.; Nageh, A.; Shehata, M.M.; Kayed, A.E.; Sabir, J.S.M.; Abiadh, A.; Jrijer, J.; Amr, Z.; Said, M.A.; et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Dromedary Camels in Africa and Middle East. Viruses 2019, 11, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reusken, C.B.; Raj, V.S.; Koopmans, M.P.; Haagmans, B.L. Cross host transmission in the emergence of MERS coronavirus. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016, 16, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Sabir, J.S.M.; Irwin, D.M.; Shen, Y. Vaccine against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1053–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reusken, C.B.; Haagmans, B.L.; A Müller, M.; Gutierrez, C.; Godeke, G.-J.; Meyer, B.; Muth, D.; Raj, V.S.; Vries, L.S.-D.; Corman, V.M.; et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, B.; Müller, M.A.; Corman, V.M.; Reusken, C.B.; Ritz, D.; Godeke, G.-J.; Lattwein, E.; Kallies, S.; Siemens, A.; van Beek, J.; et al. Antibodies against MERS Coronavirus in Dromedary Camels, United Arab Emirates, 2003 and 2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Moore, M.J.; Vasilieva, N.; Sui, J.; Wong, S.K.; Berne, M.A.; Somasundaran, M.; Sullivan, J.L.; Luzuriaga, K.; Greenough, T.C.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 2003, 426, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Cao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, J.; Qi, J.; Wang, Q.; Lu, G.; Wu, Y.; Yan, J.; Shi, Y.; et al. Cryo-EM structures of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV spike glycoproteins reveal the dynamic receptor binding domains. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, J.K.; E Goldstein, M.; Labitt, R.N.; Hsu, H.-L.; Daniel, S.; Whittaker, G.R. A camel-derived MERS-CoV with a variant spike protein cleavage site and distinct fusion activation properties. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2016, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulswit, R.J.G.; De Haan, C.A.M.; Bosch, B.J. Coronavirus Spike Protein and Tropism Changes. Adv. Virus Res. 2016, 96, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, C.S.M.E. , Molecular evolution of the SARS coronavirus during the course of the SARS epidemic in China. Science, 2004. 303(5664): p. 1666-9.

- Chu, D.K.; Poon, L.L.; Gomaa, M.M.; Shehata, M.M.; Perera, R.A.; Abu Zeid, D.; El Rifay, A.S.; Siu, L.Y.; Guan, Y.; Webby, R.J.; et al. MERS Coronaviruses in Dromedary Camels, Egypt. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.K.; O Oladipo, J.; Perera, R.A.; A Kuranga, S.; Chan, S.M.; Poon, L.L.; Peiris, M. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in dromedary camels in Nigeria, 2015. Eurosurveillance 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, E.; Chevalier, V.; Ayelet, G.; Ben Bencheikh, M.N.; Boussini, H.; Chu, D.K.; El Berbri, I.; Fassi-Fihri, O.; Faye, B.; Fekadu, G.; et al. Risk factors for MERS coronavirus infection in dromedary camels in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, and Morocco, 2015. Eurosurveillance 2017, 22, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.K.W.; Hui, K.P.Y.; Perera, R.A.P.M.; Miguel, E.; Niemeyer, D.; Zhao, J.; Channappanavar, R.; Dudas, G.; Oladipo, J.O.; Traoré, A.; et al. MERS coronaviruses from camels in Africa exhibit region-dependent genetic diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 3144–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiambi, S.; Corman, V.M.; Sitawa, R.; Githinji, J.; Ngoci, J.; Ozomata, A.S.; Gardner, E.; von Dobschuetz, S.; Morzaria, S.; Kimutai, J.; et al. Detection of distinct MERS-Coronavirus strains in dromedary camels from Kenya, 2017. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommeh, S.; Zhang, W.; Zohaib, A.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Hu, B.; Ge, X.-Y.; Yang, X.-L.; Masika, M.; Obanda, V.; et al. Genetic Evidence of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-Cov) and Widespread Seroprevalence among Camels in Kenya. Virol. Sin. 2018, 33, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karani, A.; Ombok, C.; Situma, S.; Breiman, R.; Mureithi, M.; Jaoko, W.; Njenga, M.K.; Ngere, I. Low-Level Zoonotic Transmission of Clade C MERS-CoV in Africa: Insights from Scoping Review and Cohort Studies in Hospital and Community Settings. Viruses 2025, 17, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, I.M.; Arden, K.E. MERS coronavirus: diagnostics, epidemiology and transmission. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlan, A.; Zhao, J.; Sarkar, M.K.; Li, K.; McCray, P.B.; Perlman, S.; Gallagher, T.; Dermody, T.S. Receptor Variation and Susceptibility to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4953–4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, A.C.; Schäfer, A.; Okuda, K.; Leist, S.R.; Kocher, J.F.; Cockrell, A.S.; Hawkins, P.E.; Furusho, M.; Jensen, K.L.; Kyle, J.E.; et al. Dysregulation of lung epithelial cell homeostasis and immunity contributes to Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease severity. mSphere 2025, 10, e0095124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, C.; Bhattacharya, M.; Das, A.; Saha, A. Regulation of miRNA in Cytokine Storm (CS) of COVID-19 and Other Viral Infection: An Exhaustive Review. Rev. Med Virol. 2025, 35, e70026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrijević, Z.; Gligorijević, N.; Šunderić, M.; Penezić, A.; Miljuš, G.; Tomić, S.; Nedić, O. The association of human leucocyte antigen (HLA) alleles with COVID-19 severity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Med Virol. 2022, 33, e2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K. , et al., HLA-DQA1*01:03 and DQB1*06:01 are risk factors for severe COVID-19 pneumonia. HLA, 2024. 104(1): p. e15609.

- Hajeer, A.H.; Balkhy, H.; Johani, S.; Yousef, M.Z.; Arabi, Y. Association of human leukocyte antigen class II alleles with severe Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus infection. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2016, 11, 211–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

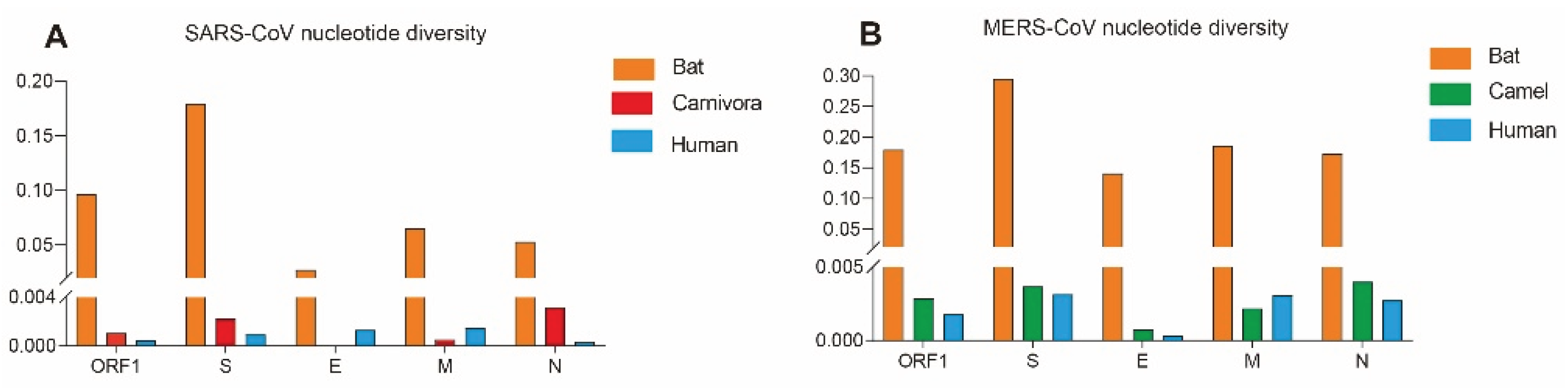

| Gene |

Host |

Nucleotide diversity (π) |

Neutrality analyses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fu and Li's D* | Fu and Li's D* | ||||

| SARS-CoV | ORF1 | Human | 0.00048 | -2.63679** | -5.05802** |

| Bat | 0.09634 | -0.72289 | -0.85435 | ||

| Carnivora | 0.00107 | -1.45552 | -1.05296 | ||

| Human | 0.00094 | -2.29683** | -4.31580** | ||

| S | Bat | 0.17954 | 0.35301 | -0.36182 | |

| Carnivora | 0.00225 | -0.10083 | -1.05012 | ||

| Human | 0.00132 | -1.63734* | -0.82508 | ||

| E | Bat | 0.02742 | -1.05697 | -1.11301 | |

| Carnivora | / | / | / | ||

| Human | 0.00151 | -1.99699* | -3.68341** | ||

| M | Bat | 0.06514 | -1.22163 | -1.01881 | |

| Carnivora | 0.00054 | -1.03789 | -0.50381 | ||

| Human | 0.00037 | -2.23097 ** | -4.79424** | ||

| N | Bat | 0.053134 | -1.43029 | -1.77074** | |

| Carnivora | 0.00320 | -0.63115 | 0.04240 | ||

| Human | 0.00048 | -2.63679** | -5.05802** | ||

| MERS-CoV | ORF1 | Human | 0.00180 | -2.32084** | -8.53056** |

| Camel | 0.00286 | -2.03977* | -6.02846** | ||

| Bat | 0.17953 | -0.04466 | 0.68164 | ||

| Human | 0.00316 | -2.23642 ** | -7.86620** | ||

| S | Camel | 0.00369 | -2.12122** | -5.43913** | |

| Bat | 0.29554 | -0.13075 | 0.44654 | ||

| Human | 0.00033 | -2.06853* | -5.60248** | ||

| E | Camel | 0.00078 | -1.89892* | -3.04304* | |

| Bat | 0.14117 | 0.35028 | 0.68165 | ||

| Human | 0.00307 | -1.65090 | -5.28654** | ||

| M | Camel | 0.00219 | -2.08234* | -3.89494** | |

| Bat | 0.18639 | 0.06353 | 0.68401 | ||

| Human | 0.00276 | -2.15013** | -4.22054** | ||

| N | Camel | 0.00401 | -2.10318* | -4.26757** | |

| Bat | 0.17372 | -0.07776 | 0.54725 | ||

| Gene | Positive selection pressure sites identified by different methods | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M8 vs. M8a | FEL | SLAC | FUBAR | MEME | PSC* | |

| Bat S | 5,8,20,132,133,135,136,138,154,182,195,411,412,422,439,481,503,589,689 | 166,540,596,633 | None | 451,540,648 | 7,20,24,43,81,82,83,89,91,101,130,156,157,160,166,174,178,185,190,207,210,231,242,252,314,410,411,451,454,464,465,477,501,502,509,516,540,562,596,633,648,689,693,753,876,935,1117,1250,1253 | 540 |

| Bat E | None | None | None | None | None | - |

| Bat M | 14 | 97 | None | None | 97 | - |

| Bat N | 8,22,268,410 | 8,22,25,34,81,121,268,410 | None | 8,25,81,410 | 8,22,25,34,81,121,196,268,297,408, 410 |

8,22,25,81,268,410 |

| Carnivora S | 77,108,113,139,147,194,227,239,243,244,261,294,336,344,360,461,470,477,478,556,575,578,605,607,611,630,642,645,648,663,699,701,741,752,763,776,819,837,842,892,898,1050,1078,1161,1217, | 77,147,227,479, 609,743,894,1080 |

None | 147,227,244,344,360,440,462,479,480,609,613,743,1052,1080,1219 | 147,227,479,609, |

147,227,462, 479,609 |

| Carnivoral E | None | None | None | None | None | - |

| Carnivora M | None | None | None | None | None | - |

| Carnivora N | 384 | None | None | 384 | None | - |

| Human S | 2,5,12,49,75,77,78,138,139,144,147,238,243,310,343,349,352,359,383,424,435,441,462,471,479,486,500,576,599,604,607,608,612,622,651,664,665,742,764,777,793,855,859,860,862,1000,1131,1147,1162,1168,1182,1207,1222,1246 | None | None | 12,138,311,608,609,1148,1163,1208 | 138 | 138 |

| Human E | 5,6,23,29 | None | None | None | None | - |

| Human M | 5,11,27,38,68,73,81,86,91,99,113, 119,154,210 |

None | None | 11 | None | - |

| Human N | None | None | None | None | None | - |

| Gene | Positive selection pressure sites identified by different methods | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M8 vs. M8a | FEL | SLAC | FUBAR | MEME | PSCa | |

| Bat S | None | 3,7,25,225,328,625,731,777 | None | 219 | 3,7,25,145,199,222,225,232,235,239,591,687,713,731,772,777,794,795,908,966,1277,1293 |

- |

| Bat E | None | None | None | None | None | - |

| Bat M | None | None | None | None | 96 | - |

| Bat N | None | 200,328,378,389,394,402, 403,424,435 | None | 200,328,389,398,424 | 111,200,210,328,367,378,389,402,403,406, 424,431 | 200,328,389,424 |

| Camel S | 26,459,465,612,723,1193,1224 | 26,28,424,459,723,1224 | 26 | 26,28,158,390,424,710,723,1193,1224 | 26,28,424,459,723,1224 | 26,28,424,459,723,1224 |

| Camel E | None | None | None | None | None | - |

| Camel M | None | 69,111,155 | None | 8,69,82 | 69 | 69 |

| Camel N | None | 3,198 | None | 3,198 | 3,198 | 3,198 |

| Human S | None | 424 | None | 26,91,95,301,424,507,509,534,914,1158 | 1020 | - |

| Human E | None | None | None | None | None | - |

| Human M | None | None | None | 15,20,69 | None | - |

| Human N | None | None | None | 8,126,300 | None | - |

| * Note: Positively Selected Codons: only the codons identified by at least three of the five methods were considered to be positively selected codons.“-” indicates that no positive selection site was detected in this gene. | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).